Abstract

Introduction:

Mental health issues, especially depression, are common in chronic pain patients. Depression affects these patients negatively and could lead to poor control of their pain. Some risk factors for both chronic pain and depression are known and need to be targeted as part of the management in a multidisciplinary approach. This study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of depression among chronic pain patients attending a pain clinic and to explore the association between depression in chronic pain patients and other factors such as sociodemographic features, number of pain sites, severity of pain, and types of pain.

Methods:

This is a cross-sectional study that carried out in a chronic pain clinic in a tertiary care hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre). All chronic pain patients including cancer-related pain, apart from acute pain patients and children, were eligible to participate in the study. Association between depression and sociodemographic factors was assessed with univariate and multivariate methods. Main outcome measures were the prevalence of depression in chronic pain patients using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the association with sociodemographic factors.

Results:

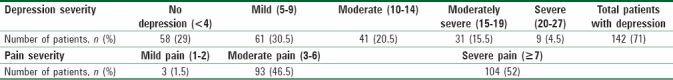

A total of 200 chronic pain patients (128 females [64%]) participated in the study. The prevalence of depression was 71% (95% confidence interval: 64.7–77.3) based on the PHQ-9 diagnostic criteria using a cutoff point of >5. Among those patients who were depressed, 9 (4.5%) had severe depression as compared to 31 (15.5%), 41 (20.5%), and 61 (30.5%) who had moderately severe, moderate, and mild depression, respectively. Depression (scored at the cutoff point of 5) in chronic pain patients was significantly associated with age, financial status, medical history of depression, and pain severity.

Conclusion:

Depression is common among chronic pain patients with several risk factors aggravating its presentation. Due to their increased risk of depression, psychiatric counseling that offers mental health assistance should be prioritized and made available as a multidisciplinary approach for the treatment of chronic pain patients.

Keywords: Chronic pain, depression, mental health disorders, perceived health questionnaire, sociodemographic factors

Introduction

Chronic pain (also persistent pain) is defined as pain lasting for >3 months. Prevalence estimates for chronic pain range from 9% to 33%.[1,2,3] Mental health disorders commonly occur in patients with chronic pain. The reported 12-month prevalence rates in population-based samples range anywhere from 7% to 28% for depression, 4% to 17% for anxiety, and 0.8% to 5% for substance abuse disorders.[2,3,4] Other studies have shown that the prevalence of depression in patients with pain varies from 14% to 66% dependant on samples in retirement homes, primary care settings, pain clinic, and community samples.[2,5,6,7,8] One study mentioned that chronic pain increases the risk of depression by 2- to-5-fold.[9]

However, the studies assessing chronic pain are inconsistent in terms of duration of pain considered as chronic. Few studies have mentioned pain duration while others have considered pain lasting for longer than 1 month as chronic. Regardless of these limitations, some studies have assessed the risk factors in patients with co-occurring pain and depression. It was found that pain occurred more commonly in females, unemployed, and those with lower education levels.[10,11,12] Common risk factors for depression included gender, income, and education.[10,11,12] Patients with two or more pain complaints were far more likely to be depressed than those with a single pain complaint. The greater the number of pain conditions reported, the more likely that major depression was present rather than pain severity or pain persistence.[13] There is a lack of data pertaining to pain, particularly in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia where no previous studies have explored the relation of chronic pain to depression.

Within the above-mentioned background, more research should be dedicated to explore the magnitude and the associated factors, contributing to emotional disorders such as depression among chronic pain patients. This study aimed to explore the prevalence of depression among chronic pain patients attending the pain clinic. The study also examined the association between depression in chronic pain patients and other factors such as sociodemographic features, number of pain sites, severity, and types of pain.

Methods

Study design

The cross-sectional study was conducted over a period of 6 months from November 2015 to April 2016 at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSH and RC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The study included a convenient sample of patients having chronic pain attending the chronic pain clinic at KFSH and RC. The study excluded patients with pain of <6 months, admitted patients, and children.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee at the Research Centre in KFSH and RC in October 2015 (Project number 2151179). Verbal consent was attained from all study participants in lieu of respect and appreciation for their time in completing the questionnaire. The participants were provided with a written information sheet attached to the questionnaire that explained the importance and aims of the study.

Data collection

The chronic pain questionnaire that was used included duration, severity, types, and sites of pain. Other sociodemographic factors in the questionnaire were included to screen for risk factors. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used as a screening tool for depression. All the questionnaires were available in both English and Arabic language. The questionnaires were distributed to the study participants attending their regular clinic appointment at the pain clinic. Those participants facing difficulty in completing the questionnaires due to illiteracy were aided by a single investigator who assisted them by reading the questionnaire clearly, ensuring their comprehension, and recording their respective answers. The instructions were given clearly to ensure that study participants understood the contents of the questionnaires. All questionnaires were given a study number to ensure anonymity of the recruited participants; thus, all measures were taken to keep the information confidential.

Instruments

Chronic pain questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed based on the study by Mossey and Gallagher on chronic pain and depression in retirement communities as well as the study by Howe et al.[6,9] To ensure that a participant had chronic pain for this study, he or she was asked two questions: “Do you currently have pain?” and “How long have you had the pain?” If the patient answered, “yes” to the first question and “6 months or longer “to the following question, then the patient was considered eligible in participating in the study. A duration of 6 months or longer was used as the cutoff for chronic pain based on the recommendation of the key articles which mentioned similar criteria.[6,9] The type of pain, location, as well as severity of the pain were all included in the questionnaire. The latter was determined via use of the universal pain assessment tool (mild [1–2], moderate [3–6], and severe [≥7]), which was attached with the questionnaire.

Sociodemographic data

From previous studies, a concoction of structured sociodemographic factors mostly associated with depression were included in our study.[10,11,12,13] These included age, gender, marital status, level of education, work status, financial status, family relations, past and family history of depression, and history of chronic disease.

Patient health questionnaire-9

The PHQ-9 is a multipurpose instrument that has been validated and found reliable to be used for screening, diagnosing, monitoring, and measuring the severity of depression. It incorporates the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision depression diagnostic criteria with other leading major depressive symptoms into a brief self-report tool. The frequency of symptoms is rated which factors into the scoring severity index. PHQ-9 is brief and useful in clinical practice.[14] A PHQ-9 score ≥10 has a sensitivity and specificity of 88% for major depression.[15,16,17] The calculated Cronbach's alpha was 0.76, which showed an acceptable reliability level of the used questionnaire. In our study, we also used the Arabic Version of the PHQ-9, which has been validated and found reliable to be used in an Arabic-speaking population.[18]

Depression scores were categorized based on PHQ-9 into five categories: no depression (0–4), mild depression (5–9), moderate depression (10–14), moderate–severe depression (15–19), and severe depression (20–27).[19]

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics for the continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. All the categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to define which demographic and clinical characteristics were most likely to be associated with depression. All the statistical analysis of this cross-sectional study was done using the software package SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Prevalence of depression in chronic pain

A total of 200 chronic pain patients participated in the study. There were 72 males (36%) and 128 females (64%). The prevalence of depression was 71% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 64.7–77.3) based on the PHQ-9 diagnostic criteria using a cutoff point of >5. [Table 1]. Most of chronic pain patents participating in the study were middle-aged (40–59 years, n = 88; 44%) followed by elderly (≥60 years, n = 65; 32.5%). Majority were married 114 (75.5%) and almost half 81 (57%) had low education level (high school or less). A total of 104 (52%) of chronic pain patients reported severe pain (≥7 in universal pain assessment tool), 93 (46.5%) had moderate pain (3–6), and 3 (1.5%) had mild pain (1–2) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of chronic pain patients according to depression severity and pain severity

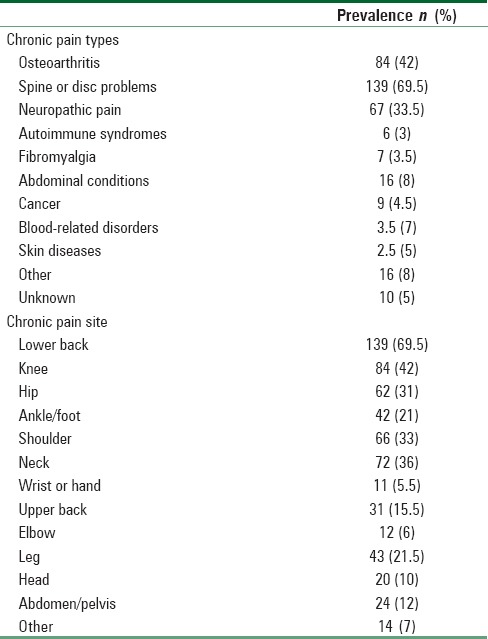

Prevalence, types, and sites of chronic pain

Spine problems (n = 139; 69.5%) accounted for the most common followed by osteoarthritis (n = 84; 42%) and neuropathic pain (n = 67; 33.5%) [Table 2]. The most common site was the lower back (n = 139; 69.5%) followed by the knee (n = 84; 42) [Table 2]. However, when lower and upper back pain reports were combined creating a back-pain category, 85% of the study participants (n = 170) had chronic pain reported as back pain.

Table 2.

Prevalence of chronic pain types and by chronic pain site

Risk factors for depression in chronic pain

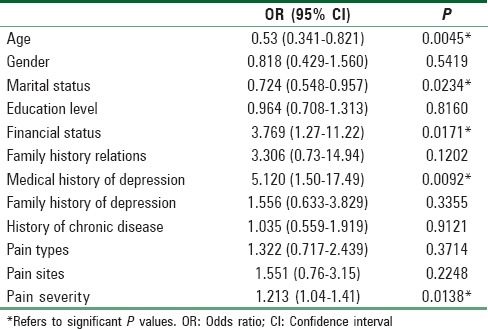

Univariate logistic analysis showed a significant association between depression and risk factors including age (P = 0.0045), marital status (P = 0.0234), financial status (P = 0.0171), medical history of depression (P = 0.0092), and pain severity (P = 0.0138) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Univariate logistic regression analysis sociodemographic factor

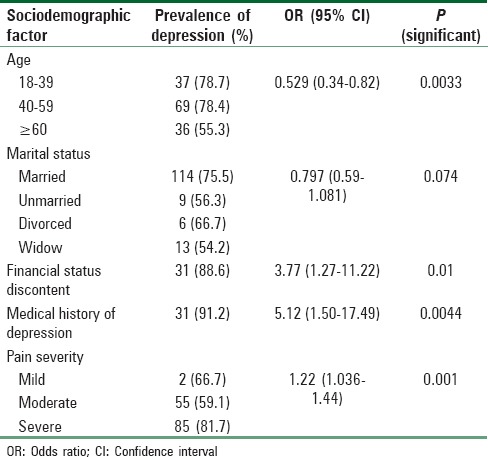

However, multivariate logistic analysis showed [Table 4] that marital status was not significantly associated with depression (P = 0.074). Hence, other factors including age, financial status, medical history of depression, and pain severity were significantly associated with depression.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression and cross tabling analysis of sociodemographic risk factors in chronic pain patients and its association with depression

Age had a statistically significant effect on depression, where middle-aged participants (n = 69, 78.4%) were more likely to have depression than their younger or older age group counterparts (odds ratio [OR]: 0.529, 95% CI: 0.341–0.821; P = 0.0033). A significant number of patients 31 (88.6%) who were unsatisfied with their financial status, reported depressive symptoms compared to 111 (67.2%) of those who were satisfied (OR: 3.77, 95% CI: 1.27–11.22; P = 0.01). Hence, financially discontented participants were more than three times as likely to elicit signs of depression as compared to their financially content chronic pain-matched participants. Prevalence of depression in participants with a positive medical history of depression reached to almost 31 (91.2%) which concurred to being five times more likely to have depression than those who did not report a medical history of depression 111 (66.8%) (OR: 5.12, 95% CI: 1.50–17.49; P = 0.0044). Regarding severity of pain and its association with depression, results showed that patients who had severe pain were more likely to be depressed 85 (81.7%) than those who had mild to moderate pain (2 [66.7%] and 55 [59.1%], respectively) (OR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.036–1.44; P = 0.001).

Discussion

The prevalence of depression observed in our study was consistent with a previous study[20] but not comparable to the majority of studies.[2,5,6] This may be explained by the use of different screening tools, environmental factors, population sample, as well as the lower cutoff limit of 5 used in our study versus a higher cutoff limit of 10 and more used in different populations to diagnose depression.[21,22,23] Choi et al. have championed the use of PHQ-9 as a screening tool for depression with cutoffs of 5 and have validated, studied, and compared with other screening tools in pain patients with fair enough sensitivity and specificity.[19] To reiterate, this variation in prevalence of depression can be explained due to differences in culture, health-care system, and population, in addition to the tools used in the study. Other reasons to consider are the heterogeneous sample of chronic pain patients used in our study versus other studies published in the literature that target a specific pain problem such as back pain.[24,25] Chronic pain may have an effect on mood as it is a chronic stressor that frustrates its target. It has been reported that approximately 90% of patients with chronic pain develop depressive symptoms at the same time or after the chronic pain diagnosis.[26] In the study by Magni et al. on the general population in the United States, they found that around 18% of those diagnosed with chronic pain ultimately developed depressive symptoms as compared to a mere 8% of the population not having chronic pain.[10] However, the temporal relationship and causality between chronic pain and depression were not investigated in the current study, and this relation cannot be made by the cross-sectional study.

Most of the chronic pain conditions mentioned here were musculoskeletal, predominantly including the lower back, knee, hip, and ankle/foot in consistence with the published literature.[7] These pain sites that have been reported by the participants were typically associated with less mobility, which in turn affects their physiologic well-being and their supply of endorphins.

A number of sociodemographic risk factors in chronic pain patients were investigated as correlates of comorbid chronic pain and depression. Surprisingly in this study, gender didn’t have any effect on the risk of depression. This is in contrast to a study conducted in Pakistan where those having chronic low back pain were at a higher risk of depression and more so in females.[27]

Univariate analysis showed a positive association between marital status (P = 0.0234) and risk of depression. This is of interest since it is well known that there is congruence between male patients and their spouses as opposed to female patients and their spouses, where there is incongruence. That is, the wife of a male patient is more sympathetic to her husband's needs and perceptive of even his nonverbal behavior. Sadly, this is not true in the case of husbands of female patients. This may indeed be the reason for the significant association found in this study between chronic pain and depression with marital status as a risk factor. Keeping in mind that the majority of the participants were females,[5] however, this was not so on the multivariate analysis.

In this study, only four risk factors were significantly associated with depression which were middle-aged group in terms of age, discontented financial status, medical history of depression, and those reporting severe pain

Middle-aged participants in our study were more likely to experience comorbid chronic pain and depression than other age groups. This contradicts Kessler et al. “depression tends to decrease with age.”[26] Similarly, a study of chronic back pain showed that patients with comorbid pain and depression were younger than patients with pain and no depression.[24] The reason could be that these middle agers had an age range of 40–59 years of age and are still engrossed with family, at the peak of their work career, and amid plenty of other life stressors which might make them more vulnerable to depression when experiencing unremitting pain that becomes chronic. Both the studies by Currie and Wang[24] and Kessler et al.[26] were published nearly a decade ago and their age group of child-bearing years’ participants were younger than todays. Nowadays, people are investing more in their education and starting their families at an older age.

In addition, low socioeconomic status is well known to be associated with depression,[28] possibly because of the financial strain and burden. A person experiencing pain and depression could find it more challenging to keep their job due to their volatile temperament, making one's socioeconomic status, depression, and pain a vicious cycle. Another risk factors for depression, emphasized in the current study, was the medical history of depression. The risk of depression recurrence was studied recently in chronic noncancer pain patients who were on opioids and compared with those who were not on opioids, which found a higher risk of depression recurrence, especially in those who were on opioids.[29] This elaborates the importance of obtaining a good history of perceived depression in any medical consultation for chronic pain patients as opioids are more likely to be prescribed in those with pain, especially at the pain clinic when all other avenues have been explored.

In this study, depression in chronic pain patients was not found to be related with any specific type of pain. The type of pain or the site was not related to depression. This is unusual as it would make sense that activity-restricting pain would increase the risk of depression.[30] It could be that chronic pain generally affects social activities, which might lead to solitude and a state of “unhappiness.” Pain severity was another associated risk factor for depression found in our study but was not related to depression in one other study.[7]

There are some limitations to this research. Although PHQ-9 has been proven as a reliable screening tool, it should be used in conjunction with a clinical assessment to provide a better management of the patients’ condition.[31]

There is a need to have a multidisciplinary approach for detecting and managing depression in chronic pain patients in hospitals. In addition, the results suggest the need for mental health promotion activities targeting chronic pain patients.

Another limitation of our study was that a number of participants completed the questionnaire themselves while others who were illiterate had to have the investigator read the questions to them, ascertain their comprehension, and record their respective answers. That may bias the understanding of the questionnaire, and eventually, it may affect the results. Furthermore, this study did not compare the depression status of the participants before and following the incidence of chronic pain which may accentuate the aggravating role of each or both on the subjects’ current condition.

To conclude, the small sample size is an obvious limitation. Furthermore, some risk factors were assessed subjectively rather than objectively such as family relation and financial content. Last but not least, the exact onset of chronic pain and depression as well as treatment types was not assessed. Future qualitative research should assess such information so that the temporal relationships between these variables can be better understood.

Conclusion

We found the prevalence of depression among chronic patients to be high, around 71%. This prevalence is consistent and higher than that reported in other studies. Hence, this is emphasizing the need and importance of screening all chronic pain patients for depression. The study findings highlight the need for psychiatric counseling and close support services made available to chronic pain patients. These services should target the high-risk group of chronic pain patients, especially those that are middle age, financially discontent, having a medical history of depression, and those with severe pain.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to those patients who took the time to participate in this study and to Mr. Abdelmoneim Eldali, the Technical Specialist in Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Scientific Computing Department, Riyadh, BESC, who helped us in the data analysis.

References

- 1.Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl. 1986;3:S1–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, Lee J, Constantino MJ, Fireman B, et al. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:262–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ, et al. Chronic pain in Australia: A prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127–34. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munce SE, Stewart DE. Gender differences in depression and chronic pain conditions in a national epidemiologic survey. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:394–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cano A, Johansen AB, Geisser M. Spousal congruence on disability, pain, and spouse responses to pain. Pain. 2004;109:258–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mossey JM, Gallagher RM. The longitudinal occurrence and impact of comorbid chronic pain and chronic depression over two years in continuing care retirement community residents. Pain Med. 2004;5:335–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2004.04041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller LR, Cano A. Comorbid chronic pain and depression: Who is at risk? J Pain. 2009;10:619–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rayner L, Hotopf M, Petkova H, Matcham F, Simpson A, McCracken LM, et al. Depression in patients with chronic pain attending a specialised pain treatment centre: Prevalence and impact on health care costs. Pain. 2016;157:1472–9. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howe CQ, Robinson JP, Sullivan MD. Psychiatric and psychological perspectives on chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2015;26:283–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magni G, Caldieron C, Rigatti-Luchini S, Merskey H. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and depressive symptoms in the general population. An analysis of the 1st National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Pain. 1990;43:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90027-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magni G, Marchetti M, Moreschi C, Merskey H, Luchini SR. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and depressive symptoms in the National Health and Nutrition Examination. I. Epidemiologic follow-up study. Pain. 1993;53:163–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magni G, Moreschi C, Rigatti-Luchini S, Merskey H. Prospective study on the relationship between depressive symptoms and chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 1994;56:289–97. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkin SF, Von Korff M, LeResche L. Multiple pains and psychiatric disturbance. An epidemiologic investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:239–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810150039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maurer DM. Screening for depression. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto-Meza A, Serrano-Blanco A, Peñarrubia MT, Blanco E, Haro JM. Assessing depression in primary care with the PHQ-9: Can it be carried out over the telephone? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:738–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker S, Al Zaid K, Al Faris E. Screening for somatization and depression in Saudi Arabia: A validation study of the PHQ in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32:271–83. doi: 10.2190/XTDD-8L18-P9E0-JYRV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi Y, Mayer TG, Williams MJ, Gatchel RJ. What is the best screening test for depression in chronic spinal pain patients? Spine J. 2014;14:1175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romano JM, Turner JA. Chronic pain and depression: Does the evidence support a relationship? Psychol Bull. 1985;97:18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Busaidi Z, Bhargava K, Al-Ismaily A, Al-Lawati H, Al-Kindi R, Al-Shafaee M, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among university students in Oman. Oman Med J. 2011;26:235–9. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Ghafri G, Al-Sinawi H, Al-Muniri A, Dorvlo AS, Al-Farsi YM, Armstrong K, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms as elicited by Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) among medical trainees in Oman. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;8:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596–602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Currie SR, Wang J. Chronic back pain and major depression in the general Canadian population. Pain. 2004;107:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elbinoune I, Amine B, Shyen S, Gueddari S, Abouqal R, Hajjaj-Hassouni N, et al. Chronic neck pain and anxiety-depression: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:89. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.89.8831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sagheer MA, Khan MF, Sharif S. Association between chronic low back pain, anxiety and depression in patients at a tertiary care centre. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:688–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmerman FJ, Katon W. Socioeconomic status, depression disparities, and financial strain: What lies behind the income-depression relationship? Health Econ. 2005;14:1197–215. doi: 10.1002/hec.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scherrer JF, Salas J, Copeland LA, Stock EM, Schneider FD, Sullivan M, et al. Increased risk of depression recurrence after initiation of prescription opioids in noncancer pain patients. J Pain. 2016;17:473–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson GM, Schulz R. Pain, activity restriction, and symptoms of depression among community-residing elderly adults. J Gerontol. 1992;47:P367–72. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.p367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, Burchell CM, Orleans CT, Mulrow CD, et al. Screening for depression in adults: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:765–76. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]