Abstract

We report a case of a 32-year-old male patient who developed unilateral lower-limb compartment syndrome following a long surgical procedure during which intermittent pneumatic compression was used as deep-venous thrombosis prophylaxis. This complication of surgery is associated with significant morbidity. Previously published reports have suggested the possible risk factors and a way to reach a diagnosis at an early stage. The possible risk factors we present are the long operative time and the use of intermittent pneumatic compression as deep-vein thrombosis prophylaxis. These findings could be used to raise awareness in early diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Leg compartment syndrome, maxillofacial surgery, postoperative complication, supine position

Introduction

Compartment syndrome is a well-known complication of leg trauma. However, it is rare to develop compartment syndrome of the lower extremities after surgeries that do not involve the limb.[1] When a compartment syndrome develops without a history of trauma, well-leg compartment syndrome (WLCS) is diagnosed. Factors that increase the patient's risk of developing WLCS include procedure duration (>4 h), lithotomy or Trendelenburg positions, ankle dorsiflexion, muscular lower limbs, leg holder type, intermittent pneumatic compression devices (IPCDs), circumferential wrappings, intraoperative hypotension, hypovolemia, vasoconstrictive drugs, and peripheral vascular disease.[2]

Case Report

A 32-year-old male patient presented to the maxillofacial surgery, outpatient clinic in December 2014 where he was diagnosed with a retrognathic maxilla. The patient had a history of cleft palate surgery during his childhood with an uneventful recovery.

The patient underwent maxillary advancement and mandibular to follow counterclockwise rotation with alveolar bone grafting. The operative procedure took approximately 8 h during which the patient was in supine position.

IPCD was applied during the operation to prevent deep-vein thrombosis (DVT). The legs remained in an appropriate position throughout the surgery. The patient required no blood transfusion; his total blood loss was around 400 mL with adequate urine output through a Foley's catheter (100 ml/h).

On the first postoperative day, the patient began to experience pain in his right leg which gradually worsened. On the second postoperative day, he became unable to dorsiflex his left toes nor to dorsiflex or evert the ankle. He also developed tenders over the anterior compartment of the left leg, compromised sensation over the dorsum of the left foot and the left first web space. He had palpable dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses. The patient was diagnosed with the left leg compartment syndrome and was taken to the operating room for four compartment fasciotomies with the application of vacuum-assisted closure dressing.

The condition of the patient stabilized after the fasciotomy, and the swelling in the leg decreased over the following week. The patient was then taken back to the operating room for wound debridement and closure of the skin.

Three weeks after discharge, the patient was seen in the clinic for follow-up. The fasciotomy wounds were well healed. He showed improvement in the function of the common peroneal nerve distribution and could dorsiflex his left toes. The patient continues to follow-up with the physical therapy and orthopedic surgery teams.

Discussion

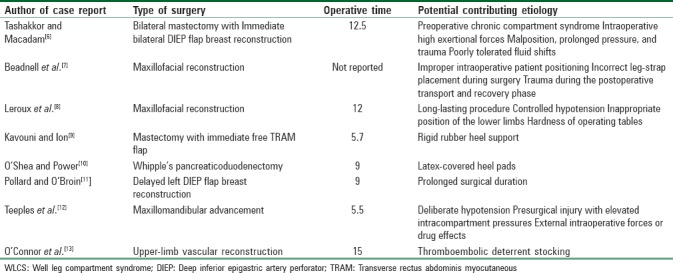

WLCS is defined by Tan et al. as the elevated compartment pressure in the leg after it is placed in hemilithotomy or lithotomy position.[3] The overwhelming majority of WLCS report is associated with urological, gynecological, and orthopedic surgeries.[4,5] In fact, WLCS usually occurs after the patient is placed in lithotomy position for prolonged operating hours. Interestingly, our patient was in supine position during the surgery time, a very rare complication. A search of the literature concluded only eight reports with a similar outcome [Table 1].[6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]

Table 1.

Reports of WLCS in patients in supine position

In addition, evidence shows that IPCD could lead to WLCS. Although developed as an alternative to prevent DVT through anticoagulation, such devices were reported to cause peroneal nerve palsy and pressure necrosis of the thigh.[14,15] Even though the risk of these complications do not outweigh the intended prevention that the use of these devices have, they should still be considered as possible risk factors. This mechanical prophylaxis consisting of timed compressions to the lower leg could cause a direct injury to the Common peroneal nerve which can cause the palsy by consequence.[16] It can also be seen as a cause for WLCS if the mechanical compression of these devices malfunctions or is administered wrongly.[17] The physical presence of IPCDs could decrease the compartment volume in the leg and by that increases its pressure, which, in turn, could cause muscle necrosis and loss of membrane integrity of capillaries. This occurrence would then make the patient prone to edema, which, in turn, increases the compartment pressure which leads to nerve injury.[18]

Moreover, failure to diagnose and treat this condition early could be associated with high morbidity and mortality.[19] Early signs include severe pain, particularly on passive stretching of the involved muscles, and diminished sensory discrimination. Pulselessness and local paralysis are late signs associated with a relatively poor prognosis. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is necessary to prompt its diagnosis as well as the physician's knowledge of the patient's risk factors. When the diagnosis is in doubt, compartmental pressures can be measured for confirmation.[1]

A hypothesis partaking to the underlying mechanism of WLCS is the hypoperfusion of compartmental muscles, vascular insufficiency or external compressing forces that raise the intracompartmental pressure. External compressing forces (in the form of IPCD), in addition to long operating time, could act as a factor leading to acute muscles ischemia in the compartment. We found the external compressing forces to be the only factors can explain the WLCS in our case. However, these hypotheses need further studies to be confirmed. Raza et al., suggested that IPCDs should be avoided in operations lasting for more than 4 hours and that legs should be removed from support for a short period every 2 hours.[2] This is due to the dramatic restriction of the volume of the compartments and the intraoperative increase of the intracompartmental pressure when external forces are placed on the legs.[20] The latter includes evidence that IPC devices could lead to WLCS. Our case presented no risk factors usually associated with WLCS. Therefore, we suggest adding the use of IPC devices to the risk factors of such complication. IPC devices need to be used with caution, with the period and method of application taken into careful consideration.

Well leg compartment syndrome is associated with significant morbidity requiring early recognition and management. We present our case to raise awareness that the use of intermittent pneumatic compression as DVT prophylaxis could be associated with the development of WLCS.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chin KY, Hemington-Gorse SJ, Darcy CM. Bilateral well leg compartment syndrome associated with lithotomy (Lloyd Davies) position during gastrointestinal surgery: A case report and review of literature. Eplasty. 2009;9:e48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raza A, Byrne D, Townell N. Lower limb (well leg) compartment syndrome after urological pelvic surgery. J Urol. 2004;171:5–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000098654.13746.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan V, Pepe MD, Glaser DL, Seldes RM, Heppenstall RB, Esterhai JL, Jr, et al. Well-leg compartment pressures during hemilithotomy position for fracture fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:157–61. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung JH, Ahn KR, Park JH, Kim CS, Kang KS, Yoo SH, et al. Lower leg compartment syndrome following prolonged orthopedic surgery in the lithotomy position – A case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59(Suppl):S49–52. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2010.59.S.S49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulrich D, Bader AA, Zotter M, Koch H, Pristauz G, Tamussino K. Well-leg compartment syndrome after surgery for gynecologic cancer. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 2010;26:261–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tashakkor AY, Macadam SA. Lower extremity anterior compartment syndrome complicating bilateral mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction: A case report and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:103–6. doi: 10.1177/229255031202000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beadnell SW, Saunderson JR, Sorrenson DC. Compartment syndrome following oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46:232–4. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leroux C, Béliard C, Theolat M, Testa S, Péan D, Moreau D, et al. Syndrome postopératoire des loges tibiales antéro-externes: Coresponsabilité de la table opératoire. Ann Fr Anesth Réanim. 1999;18:1061–4. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(00)87440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kavouni A, Ion L. Bilateral well-leg compartment syndrome after supine position surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44:462–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Shea E, Power K. Well leg compartment syndrome following prolonged surgery in the supine position. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55:794–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03016360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollard RL, O’Broin E. Compartment syndrome following prolonged surgery for breast reconstruction with epidural analgesia. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:e648–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teeples TJ, Rallis DJ, Rieck KL, Viozzi CF. Lower extremity compartment syndrome associated with hypotensive general anesthesia for orthognathic surgery: A case report and review of the disease. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:1166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor D, Breslin D, Barry M. Well-leg compartment syndrome following supine position surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38:595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pittman GR. Peroneal nerve palsy following sequential pneumatic compression. JAMA. 1989;261:2201–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03420150051030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parra RO, Farber R, Feigl A. Pressure necrosis from intermittent-pneumatic-compression stockings. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912073212316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lachmann EA, Rook JL, Tunkel R, Nagler W. Complications associated with intermittent pneumatic compression. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:482–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsen FA., 3rd Compartmental syndrome. An unified concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;113:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mubarak S, Owen CA. Compartmental syndrome and its relation to the crush syndrome: A spectrum of disease. A review of 11 cases of prolonged limb compression. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;113:81–9. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197511000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hargens AR, Schmidt DA, Evans KL, Gonsalves MR, Cologne JB, Garfin SR, et al. Quantitation of skeletal-muscle necrosis in a model compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:631–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chisholm CD, Clark DE. Effect of the pneumatic antishock garment on intramuscular pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:581–3. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]