Abstract

Is medicare a reflection of Canadian values? Or did those values develop as we experienced the common ground of a universal system? Nothing in public opinion in Canada and the US in the 1960s, or in their respective healthcare systems, would have suggested that they would evolve in such divergent ways. Instead, decisions taken by political elites set the two systems on very different courses. In Canada, that course profoundly shaped the way we understand ourselves as citizens, and also established a powerful place for clinicians at the political core. In so doing, it insulated the system from change, for both good and ill.

Abstract

L'assurance maladie est-elle le reflet des valeurs canadiennes? Ou plutôt, ces valeurs se sont-elles développées alors que nous nous dotions d'un système universel? Rien dans l'opinion publique des années 1960 au Canada et aux États-Unis, ou dans leurs systèmes de santé respectifs, ne laissait croire qu'ils évolueraient de façon si divergentes. Pourtant, les décisions prises par les élites politiques ont aiguillés les deux systèmes vers des chemins très différents. Au Canada, cela a profondément modifié l'identité citoyenne et a placé les cliniciens en position de force sur la scène politique. Ce faisant, le système est devenu plus imperméable au changement, pour le meilleur et pour le pire.

As Canadian as Medicare

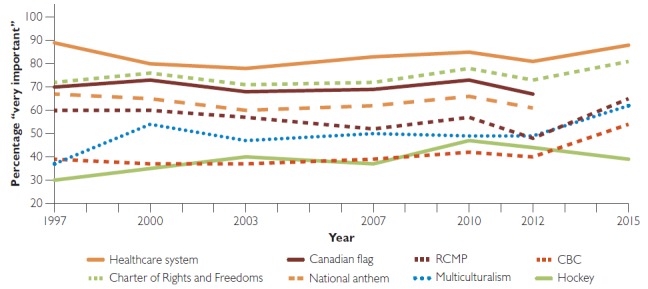

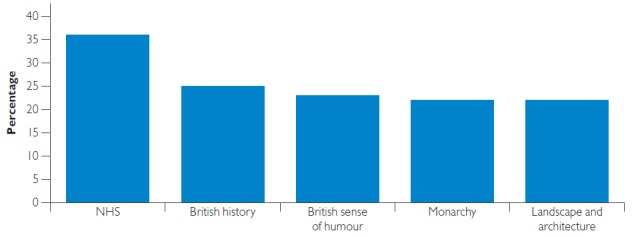

It is a truism to observe that medicare is a Canadian icon. It is consistently cited as a leading, possibly the leading, symbol of Canadian identity (Figure 1). Indeed, it plays a role in the Canadian psyche at least as important as that played by the National Health Service (NHS) in Britain (Figure 2) (although Canada has not gone so far as to feature medicare in its Olympic opening ceremonies, as the British did with the NHS in 2012).1

Figure 1.

Important symbols of Canadian identity (1997–2015)

CBC = Canadian Broadcasting Corporation; RCMP = Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Source: Data compiled from Environics Institute 2011, 2013, 2016, and Soroka and Robertson 2010.

Figure 2.

What makes you most proud to be British?*

NHS = National Health Service.

Source: Crouch 2016.

Medicare is an important expression of Canadian values indeed. But which came first? Did Canadian values shape medicare or is it the other way around?

My argument here is that medicare came first: it profoundly shaped Canadians' understanding of themselves as a sharing community. The available data do not allow us to make a systematic pre- and post-comparison of Canadian attitudes. But a careful look back at the history of Canadian medicare in comparative context can serve to make the argument.

First, let me be clear about how I am using the concept of “medicare” in this context: I mean the federal framework that establishes principles of healthcare coverage that are common across the country. It is this common framework that has become central to the definition of a pan-Canadian “sharing community” (Banting and Broadway 2004). In practical terms, however, this “single-payer” framework of comprehensive universal coverage applies only to physician and hospital services. (One of the puzzles of Canadian health policy is why the popularity of the single-payer model has not created the political conditions for its expansion to other aspects of healthcare. I return to this point later in these remarks.)

The Landscape of Opinion

The design of Canadian medicare was an elite project – it was the product of contest and reconciliation among federal and provincial governments, and between the medical profession and the state. Public attitudes toward governmental health insurance prior to the establishment of universal hospital and physician insurance were vague and malleable. Indeed, the same can be said for the NHS and, for that matter, for US Medicare and Medicaid as well. These were all elite projects, and while the framers in each case were influenced by the broad zeitgeist of their times, they were not responding to public clamour for any particular option. If we look at such polling data as exist from the periods in which the NHS, Canadian medicare and American Medicare and Medicaid were established, we see that in all three countries attitudes toward various program designs for health insurance could shift according to the political context and the wording of the questions posed by pollsters.

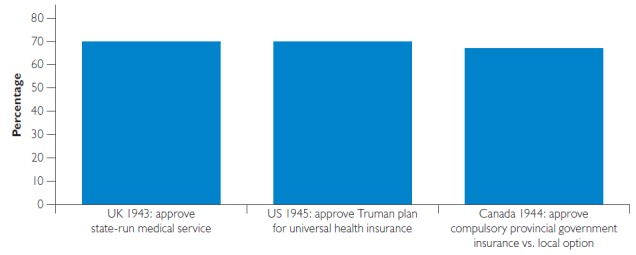

Poll data from the 1940s indicate that roughly two-thirds of Canadian respondents who offered an opinion favoured a universal government plan – about the same proportion as in the UK and the US at the time (Figure 3).2

Figure 3.

Support for universal health insurance, UK, US and Canada (1943–1945)*

Sources: CMA 1944: 33; Gallup/AIPO 1945; Jacobs 1993: 115.

But these responses were vulnerable to change depending on the wording of the question. For example, a higher proportion of Canadians (80% in the 1944 poll cited in Figure 3) responded positively when asked whether they themselves would contribute “a small part of their income” for government insurance coverage without referring to universality (CMA 1944: 33). UK and US surveys registered higher support for universal health insurance in the US and UK when it was presented as a yes/no option without offering an alternative choice.3 Attitudes were also highly vulnerable to changes in the political context – for example, support for the Truman plan in the US dropped sharply over the 1945–1949 period as the plan was hotly contested in Congress and among interest groups (Blendon and Benson 2001).

By the 1960s, the landscape of opinion had shifted in both Canada and the US. In the US, the debate about options had narrowed to focus on governmental health insurance for the elderly, which enjoyed majority support in public opinion on the order of 62–65% in 1964 and 1965 (Blendon and Benson 2001). (Again, however, this support dropped to 46% approval when governmental insurance was pitted against a private option, which attracted 36% [Harris and Associates 1965].) In Canada, as much of the population had become accustomed to coverage under private plans, support for tax-supported universal health insurance had dropped below 60% by 1960 (Naylor 1986: 191). As the political debate continued to rage in the wake of the hotly contested introduction of universal physician services insurance in Saskatchewan in 1962, Canadians actually favoured a voluntary plan over a government plan in a 55/41 split in a 1965 poll (Naylor 1986: 236; Taylor 1979: 367).

It was therefore not public opinion that drove Canada along its distinctive course of healthcare coverage. And it is indeed distinctive: Canada's single-payer system lies at the end of a spectrum in its almost exclusively public first-dollar coverage for physician and hospital services. The term “single payer” was in fact coined to describe the Canadian model, albeit by American advocates who wanted the US to adopt a similar approach (Tuohy 2009: 454 n. 1). The term was meant to draw attention to the fact that Canada was able to achieve universal coverage while keeping its system of private medical practice and voluntary hospitals, by restricting the role of government to that of a “single payer” – in contrast to the multiple payers of the American system and to the multiple social insurers of continental Europe. In this context, a payer is not an owner of facilities, not an employer of healthcare professionals. Although the term is now often used to refer to any system financed out of general tax revenue, it originated in this apt characterization of a uniquely Canadian compromise between – as David Naylor classically put it – private practice and public payment (Naylor 1986).

That unique compromise was a product of its time, just as other national systems bear the marks of the eras of their birth. The British NHS was founded as a national institution as part of a grand national project of post-war reconstruction. The Beveridge report of 1942 provided the touchstone for the NHS and indeed for all of the social policy agenda that the Labour party implemented after its landslide victory in the 1945 election. Beveridge very explicitly looked forward to the rebuilding of the social as well as the physical infrastructure of the nation after the war. And in that project, he urged his compatriots to think big:

Now, when the war is abolishing landmarks of every kind, is the opportunity for using experience in a clear field. A revolutionary moment in the world's history is a time for revolutions, not for patching (Beveridge 1942: 6).

With regard to healthcare in particular, Beveridge recommended that comprehensive services would be provided for all citizens by a national health service “where needed without contribution conditions in any individual case.” It would be funded by a tax, in the form of a means-tested contribution to national insurance, but making such a contribution would not be a condition of receiving care.

For a government-commissioned product, the Beveridge report was received with an incongruous level of public enthusiasm. As Noel Whiteside reports, there were queues to buy it at the government bookshop. It eventually sold half a million copies, and a short version was distributed to British troops to boost morale. In Whiteside's words, “The report's reception turned its author into a public hero virtually overnight: it influenced post-war debates on social reform all over Western Europe and across the English-speaking world” (Whiteside 2014: 1) – including, I would add, Canada. With some adaptations, Beveridge's vision became the National Health Service that the post-war Labour government enacted into being in 1946 and implemented in 1948.

The Canada–US Divergence

The post-war climate was different in Canada and the US. Neither had experienced the ravages of war in their homeland. And while the wartime experience had demonstrated the capacity of the national government in Britain, a similar aggrandizement in Canada and the US instead fed a suspicion of federal power on the part of sub-national governments (and, in the US, the representatives of the states in the federal Congress). Attempts to adopt national health insurance failed in both countries.

Instead, the founding moments of the modern Canadian and American healthcare states came in the very different circumstances of the 1960s. Two characteristics of that era were especially important: the greater buoyancy of the economy and the growth of what we have come to call a “rights consciousness” in both nations. In Canada, a third element was also definitive: the approaching date of Canada's centenary was igniting an optimism and enthusiasm about a nation coming of age that would culminate in a grand exposition, Expo 67.

The human rights agenda began immediately after the war, with the adoption of the UN Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The declaration of a right to health actually anticipated that declaration by two years: it was enshrined in the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted in 1946 (WHO 1946). And in fact, President Truman framed his doomed proposal for national health insurance in those terms, casting healthcare as one of the fundamentals of an “Economic Bill of Rights.” Truman's bill failed in the face of implacable opposition of southern senators, and the result was a narrowing of the agenda of healthcare reform to focus on the elderly.

In the decades following the post-war failures of federal national health insurance initiatives, the evolution of “rights consciousness” took very different forms in Canada and the US. In the US, the dominant debate was about civil rights. For reasons that go beyond the scope of this paper, the civil rights agenda actually cut against the possibility of introducing universal health insurance. Even after the 1964 election gave the Democratic party a historic landslide election victory and unified control of the White House and Congress, the best that could be accomplished was a carefully crafted “three-layer cake” compromise, establishing a two-part Medicare program for the elderly: compulsory social insurance for hospital coverage and voluntary coverage for physician services, plus (as a little remarked-upon afterthought) tax-financed coverage for certain low-income groups (Medicaid).

In Canada, however, the universal human rights agenda played a prominent role in the framing of the debate about healthcare by Justice Emmett Hall. The centrality of the 1964 report of the Royal Commission on Health Services to the history of Canadian medicare needs no elaboration for this audience. It was the adoption of universal physician services insurance in accordance with that report that constituted the founding moment of Canadian medicare.4

Although Justice Hall was a pragmatic man who saw a universal government plan as preferable to means-testing on efficiency grounds, he was also a man of principle. He cited the WHO constitution in his report and framed his recommendations as a Health Charter for Canadians. That charter recognized not only an individual right to healthcare from a physician of one's choice but also the rights of “free and self-governing professions” of healthcare providers. (Anticipating some later debates, Hall also recognized a right of providers not to treat a given patient in other than emergency circumstances.) This was a quintessential Canadian approach, embedding principles in some tension with each other into constitutional and institutional arrangements and trusting that the tensions would be worked out by pragmatic compromises over time (think of the notwithstanding clause of the Canadian constitution or the federal spending power) (Tuohy 1992). The principles in Hall's charter became the conditions set out in the elegantly simple Medical Care Act of 1966 for federal cost-sharing of coverage under provincial plans. To symbolize the linkage of the adoption of medicare to Canada's centenary, the Pearson Liberal government initially planned to have the legislation come into force on July 1, 1967. Only pressure from fiscal conservatives within the Liberal Cabinet pushed that date to July 1, 1968.

Even after the publication of Hall's report, and after the demonstration effect of the adoption of universal physician services insurance in Saskatchewan in 1962, Canadian public opinion still tilted toward a voluntary program. The adoption and implementation of Canadian medicare was driven by political elites in a process of contest and compromise. Although an alliance between the Liberal and New Democratic parties ensured passage of the Medical Care Act in a minority parliament in 1966, and the Conservatives bowed to that inevitability to make passage almost unanimous, several provincial governments agreed to participate only under protest. The adoption of the single-payer model at the provincial level was book-ended by physician strikes: initially in Saskatchewan in the context of that province's pioneering adoption of the first provincial program of universal physician services insurance, and lastly in Quebec, the last province to comply with the federal framework.

Iconic Institution

What accounts, then, for the ascension of Canadian medicare to iconic status in the public imagination? And what has kept the fundamental design of the system so stable as other nations entered into major political contests over the redesign of their respective systems? Despite the various organizational changes that have roiled provincial systems as they have regionalized, re-regionalized and de-regionalized, the core of the system hasn't changed. What has stayed stable are the fundamental parameters of the system: the balance of power among the three pillars of the healthcare arena – the state, the medical profession and private finance – and the balance of command, negotiation and peer control by which power is exercised. These are the fundamental factors that determine whose interests are weighed and enforced in decisions about who gets what, when and how in healthcare.

Understanding the durability of the Canadian single-payer system means appreciating it as an institution. Political scientists understand an institution as the product of a settlement among interests at a point in time. The institutionalization of that settlement crystallizes a founding bargain that creates a set of “collectively enforced expectations” (Streeck and Thelen 2005). It establishes a balance of interest, certain rules of governance, certain organizing principles, either implicitly or explicitly, that over time come to take on a value in themselves. The ultimate enforcement mechanism for a policy framework such as Canadian medicare is the coercive authority of the state. But as the various parties to the bargain become invested in it, and as the founding myth takes hold, that enforcement becomes a mutual process.

The Canadian single-payer system can be understood as an institution, whose central defining feature is the bilateral monopoly it creates between the medical profession and the state for “medically necessary” services. Ninety-eight per cent or more of physician remuneration comes from public sources, as does more than 90% of hospital revenue. This binds the profession and the state into an accommodation that forms the central political axis of the system. (Given the centrality of the medical profession to the delivery of in-patient services, this accommodation has effectively incorporated hospitals as well.) This is an arrangement with inherent trade-offs. Excluding interests other than doctors and governments from setting the terms of access to necessary services means that coverage is based on what the profession deems to be necessary and the public fisc can sustain, not on what individuals and private insurers are willing to pay. It is this trade-off between individual choice and social equity that was litigated in the Chaoulli case in Quebec in 2005 (Flood et al. 2005) and is currently being litigated again in the Cambie case in British Columbia (Palmer n.d.) and will very likely continue to be contested at the margins of the single-payer system.

The core profession–state axis of the Canadian system has other implications. In the early years of medicare, the fact that universal coverage existed for the core of the healthcare system, amounting to about 60% of total expenditure, blunted the urgency of moving on to cover other healthcare goods and services. Later technological changes would shrink the scope of physician and hospital services (and therefore the scope of the single-payer system) to about 45% of total expenditure. Meanwhile, the rate of escalation of healthcare costs had raised the fiscal stakes of expanding public coverage, while the entrenchment of employer-based coverage outside the physician–hospital core established political barriers to change. Expansions beyond the physician–hospital core took place on a province-by-province basis as different provinces made different trade-offs in addressing these fiscal and political challenges. The province-specific expansion therefore occurred largely on terms quite different than those of the single-payer model, typically involving targeting of certain population groups versus universality and co-pays versus first-dollar coverage.

The power of the gyroscope of the profession–state accommodation, however, can be seen in the fact that the single-payer system itself did not vary much across provinces. Notwithstanding partisan shifts in the control of governments, and the vagaries of politics within medical associations, the basic interests of governments and the profession were similar across provinces and they yielded roughly similar bargains. The scope of covered services varies only at the margins, and the terms of medical remuneration and practice organization have changed slowly, albeit at somewhat different rates across provinces.

But the strength of the profession–state accommodation doesn't fully explain the stability of the Canadian system. After all, the founding bargain of the British NHS also bound the state and the profession together – not in a bilateral monopoly but in a quasi-corporatist regionalized hierarchy in which physicians (and nurses, it must be said) were incorporated into decision-making at all levels. Nonetheless, that hierarchy was dramatically restructured into separate purchaser and provider wings in the 1990s. Subsequent adaptations of that model have moved the system closer to a single-payer model in which providers are formally independent and the state exercises its authority through the power of the purse, albeit within a regulatory framework enforced from the centre (Tuohy 2018). But those changes occurred because of conditions that arose in the broad political arena: in the first instance, a third majority mandate for the Thatcher government that emboldened them to finally take on major policy change in healthcare, and to do so through an exclusionary process that kept the profession completely outside (and offside).

In Canada, no such broad political conditions for change occurred in the three decades after the passage of the Medical Care Act. The growing popularity of the single-payer model, as well as the entrenched accommodation with the profession raised the political stakes for any provincial government to act alone. Any significant change in the federal framework would have required federal–provincial negotiations, but that table was dominated by constitutional wrangling over jurisdiction. The only significant action at the federal level was to reinforce the single-payer model by consolidating the founding legislation and firming its principles in the Canada Health Act of 1984. The provinces for their part concerned themselves largely with reorganizations within the hospital and community care sectors and with incremental expansions and contractions of coverage outside the physician–hospital ambit.

At the turn of the 21st century, however, a window of opportunity did open. Constitutional conflict had subsided, and healthcare rose to the pinnacle of the federal, provincial and territorial agenda as both the public and provincial governments clamoured for federal reinvestment after the constraint of the previous decade. Commissions in all provinces and at the federal level canvassed a broad range of options for change, while effectively recommending various ways to reinforce the existing model. The federal Liberal government under Paul Martin was willing to make that investment. Even so, however, it appeared that any major change would occur largely outside the single-payer system. Remarkably, in the summer of 2004, all provincial premiers agreed to a proposal that the federal government should assume “full responsibility” for the financing and delivery of all pharmacare programs across the country through the establishment of a “national pharmacare program” of comprehensive coverage (Council of the Federation 2004: 1–2). But just as political conditions can create windows of opportunity, they can also abruptly shift and close those windows. The Martin government had been tipped into minority status in June of that year. With a government that could fall at any time, Martin determined that the credibility of his government hinged on reaching a deal with the premiers and judged that he did not have the luxury of time that it would take to negotiate federal pharmacare. Instead, pharmacare became a hostage to fortune through the establishment of a process to develop a National Pharmaceutical Strategy, and then fortune turned against the Martin government when it was defeated in 2006.

Report Card

We are left with essentially the model with which we started in the mid-20th century, enhanced by a variety of provincial programs outside the single-payer world. There are downsides and upsides to this situation. Let me start with the downsides so that I can conclude on the upside.

Most of us are familiar with Canada's infamous ranking in the Commonwealth Fund's International Health Policy Survey, in which we have consistently ranked second-worst, prevented from scraping the bottom only by the even worse performance of the US (Davis et al. 2014). But care needs to be taken in interpreting these results, which give a heavy weight to exactly those areas in which Canada performs least well: wait times, care coordination and integrated electronic information systems. Each of these failings can be laid at the door of a system that has privileged independent private practices and institutions as part of the founding profession–state bargain. Primary care reform, which would go a long way toward improving our Commonwealth Fund ranking, has been hostage to negotiations at the central negotiating table. Those negotiations have protected fee-for-service practice and have insulated medical practices from integration with other sectors. Those negotiations can go significantly off the rails, stalling even the progress that has been made.

There's another downside: cost access problems for services outside the physician–hospital realm. By not embracing those services from the outset, the Canadian medicare model inadvertently established the conditions that would militate against its own expansion in the future. There is an analogy in this regard with the US. There, the adoption of coverage in the 1960s for those groups deemed most vulnerable – the elderly and the poor – dissipated the momentum toward broader coverage and allowed the further development of private employer-based insurance, making a universal program much more politically difficult to achieve. In Canada, as noted earlier, the coverage of a core of services that in the 1960s accounted for a majority of healthcare expenditure reduced the pressure for further expansion and allowed an employer-based model of coverage for other services to take root (Boothe 2015).

But let's now return to the upsides of the Canadian system, which are substantial. First, financial barriers to access to physician and hospital services continue to be low. Comparisons of access, utilization and health outcomes for various conditions in Canada and the US continue to demonstrate the key importance of this fundamental achievement of the Canadian system. Second, a system that places clinical judgment at the heart of decision-making, respects what healthcare is all about. Canada does not always realize the full advantage of this model, but there is huge potential to do so through initiatives such as Choosing Wisely (Choosing Wisely Canada n.d.), and by building out from the current medical core of clinicians to incorporate clinicians and caregivers of other disciplines. Third, there is an enormous reservoir of public support for the system – the point with which I started. There may be an analogy here with the NHS, which has shown remarkable resilience in the face of continual reorganizations and dramatic fiscal swings over the past two-and-a-half decades, largely as a result of the dedication of its staff and the support of the public. I would not wish a similar organizational churn or fiscal whiplash for the Canadian system, although there is much to learn from some of the particular changes the British have made. But the principal lesson from the NHS and from Canada is that a system that ranks high in public priority and that places clinicians and caregivers at the heart of decision-making can withstand shifting political sands.

Let me leave you with a final observation. The Canadian healthcare model is worth defending and, yes, adapting not only for what it does for healthcare but also for what it does for Canada. Medicare has contributed to Canadian understanding of what it means to be a sharing community as much if not more than the other way around. For a time, we can count on those values to sustain Medicare in turn. It is sometimes suggested that the growth of a private sector would erode support for the public system. For the short term at least, such evidence as exists from other nations suggests the opposite: a growth in the private share of health expenditure tends to be followed by increased support for public spending (Tuohy et al. 2004: 388). But over the longer term, that relationship may not hold. Medicare has shaped our understanding of ourselves as Canadians. It could well be that an erosion of Medicare could feed back into that self-understanding in a less happy way. That is one hypothesis that we would be better not to test.

Figures 1 and 2 are based on differently worded questions. Figure 1 reports results when respondents are asked to rate the importance of various features of Canada as symbols of Canadian identity, indicating the proportion ranking each feature as “very” important. Figure 2 reports the five most popular features cited when respondents are asked to choose up to three options from a list of features of Britain that make them “most proud to be British.”

Given the lack of cross-national polling at the time, we must rely on differently worded questions for this comparison. The British and American questions are straightforwardly described in Figure 3. The Canadian question asked respondents whether they would support a government plan that was compulsory for their whole province or whether such a plan should be left to “local option.” (An “individual option” alternative was not offered.) In order to make the Canadian results as comparable as possible to those of the US poll also reported in Figure 3, I have shown those supporting a province-wide option as a proportion of those who expressed an opinion.

For example, a US Gallup poll in July 1945 found that 61% of decided respondents favoured a government-run compulsory plan over a voluntary plan set up by the medical profession. Support for a universal government plan rose to 70% in a November 1945 poll in which no other option was suggested. In April 1946, when given options regarding the aegis for a universal plan of physician and hospital services insurance, 37% chose government, 26% the medical profession and 23% private insurance companies (AIPO/Gallup polls July 1945, November 1945, April 1946. Available through Roper Center for Public Opinion Research iPOLL Databank). As for the UK, although 70% of respondents in a 1943 poll believed that a “state-run medical service” would be “beneficial for the nation,” respondents in a 1944 poll offering two options chose a publicly run system over “leaving things as they are” by only 55% to 32% (Jacobs 1993: 115).

A federal–provincial framework of universal hospital insurance had been put in place in the late 1950s. But in the 1950s and 1960s, hospitals in Canada, as in the US, functioned essentially as “physicians' workshops” or “physicians' cooperatives” under the de facto control of their medical staffs (Pauly and Redisch 1973). Governmental hospital insurance essentially underwrote the costs of these “workshops” while still leaving patients at risk for the costs of the medical services provided therein. It was therefore the adoption of physicians' services insurance in 1966 that transformed the profession–state relationship and instituted the modern Canadian healthcare state.

Footnotes

Three choices possible.

US and Canada refer to decided respondents only; undecided not reported for UK.

References

- Banting K., Boadway R. 2004. “Defining the Sharing Community: The Federal Role in Health Care.” In Lazar H., St-Hilaire F. (Eds.), Money, Politics and Health Care: Reconstructing the Federal-Provincial Partnership. Montreal, QC: Institute for Research on Public Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge W. 1942. Social Insurance and Allied Services. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Blendon R.J., Benson J.M. 2001. “Americans' Views on Health Policy: A Fifty-Year Historical Perspective.” Health Affairs 20(2): 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothe K. 2015. Ideas and the Pace of Change: National Pharmaceutical Insurance in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Medical Association (CMA). 1944. “Report of the Committee on Economics.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 33 51(Suppl.): 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Choosing Wisely Canada. n.d. Retrieved April 26, 2018. <https://choosingwiselycanada.org/>.

- Council of the Federation. 2004. (July 30). Premiers' Action Plan for Better Health Care: Resolving Issues in the Spirit of True Federalism. Retrieved April 25, 2018. <http://www.scics.ca/en/product-produit/news-release-premiers%E2%80%99-action-plan-for-better-health-care-resolving-issues-in-the-spirit-of-true-federalism/>.

- Crouch J. 2016. “NHS Tops the Pride of Britain List.” Retrieved April 26, 2018. <http://opinium.co.uk/nhs-tops-the-pride-of-britain-list/>.

- Davis K., Stremikis K., Squires D., Schoen C. 2014. “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally.” New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; Retrieved April 25, 2018. <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/fund-report/2014/jun/1755_davis_mirror_mirror_2014.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Environics Institute. 2011. Focus Canada 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2018. <https://www.environicsinstitute.org/projects/project-details/focus-canada-2010>.

- Environics Institute. 2013. Focus Canada 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2018. <https://www.environicsinstitute.org/projects/project-details/focus-canada-2012>.

- Environics Institute. 2016. “Focus Canada 2015 – Spring 2015. Survey on Immigration and Multiculturalism.” Retrieved May 10, 2018. <https://www.environicsinstitute.org/projects/project-details/focus-canada-2015-survey-on-immigration-and-multiculturalism>.

- Flood C., Roach K., Sossin L. 2005. Access to Care, Access to Justice: The Legal Debate Over Private Health Insurance in Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup/AIPO. 1945. Poll. November 23–28. Data provided by The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research iPOLL database. Retrieved May 18, 2017. <https://ropercenter.cornell.edu/ipoll-database/>.

- Harris L. and Associates. 1965. Survey. February. Data provided by The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research iPOLL database. Retrieved May 18, 2017. <https://ropercenter.cornell.edu/ipoll-database/>.

- Jacobs L.R. 1993. The Health of Nations: Public Opinion and the Making of American and British Health Policy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor David C. 1986. Private Practice, Public Payment: Canadian Medicine and the Politics of Health Insurance, 1911–1966. Kingston, ON, and Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer K. n.d. “A Primer on the Legal Challenge between Cambie Surgeries Corporation (led by Dr. Brian Day) and British Columbia — and How It May Affect our Healthcare System.” Retrieved April 26, 2018. <http://evidencenetwork.ca/a-primer-on-the-legal-challenge-between-dr-brian-day-and-british-columbia-and-how-it-may-affect-our-healthcare-system/>.

- Pauly M., Redisch M. 1973. “The Not-For-Profit Hospital as a Physicians' Cooperative.” American Economic Review 63(1): 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission on Health Services. 1964. Final Report. Ottawa, ON: Queen's Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Soroka S., Robertson S. 2010. “A Literature Review of Public Opinion Research on Canadian Attitudes towards Multiculturalism and Immigration, 2006–2009.” Retrieved June 4, 2018. <http://www.snsoroka.com/files/2012Soroka&Roberton.pdf>.

- Streeck W., Thelen K. 2005. “Introduction: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies.” In Streeck W., Thelen K. (Eds.) Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M.G. 1979. Health Insurance and Canadian Public Policy: The Seven Decisions that Created the Canadian Health Insurance System. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuohy C.H., Flood C.M., Stabile M. 2004. “How Does Private Finance Affect Public Health Care Systems? Marshaling the Evidence from OECD Nations.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 29(3): 359–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuohy C.H. 2009. “Single Payers, Multiple Systems: The Scope and Limits of Subnational Variation under a Federal Health Policy Framework.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 34(4): 453–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuohy C.H. 2018. Remaking Policy: Scale, Pace and Political Strategy in Health Care Reform. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuohy C.J. 1992. Policy and Politics in Canada: Institutionalized Ambivalence. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside N. 2014. “The Beveridge Report and Its Implementation: A Revolutionary Project?” Histoire@Politique 3(24): 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 1946. “Constitution of the World Health Organization.” Retrieved May 23, 2018. <https://archive.org/details/WHO-constitution>.