Abstract

Purpose of the Study

This study examined how women who combine long-term care employment with unpaid, informal caregiving roles for children (double-duty-child caregivers), older adults (double-duty-elder caregivers), and both children and older adults (triple-duty caregivers) differed from their workplace-only caregiving counterparts on workplace factors related to job retention (i.e., job satisfaction and turnover intentions) and performance (i.e., perceived obligation to work while sick and emotional exhaustion). The moderating effects of perceived spouse support were also examined.

Design and Methods

Regression analyses were conducted on survey data from 546 married, heterosexual women employed in U.S.-based nursing homes.

Results

Compared to workplace-only caregivers, double-duty-elder and triple-duty caregivers reported more emotional exhaustion. Double-duty-child caregivers reported lower turnover intentions and both double-and-triple-duty caregivers felt less obligated to work while sick when perceiving greater support from husbands.

Implications

Results indicate that double-and-triple-duty caregiving women’s job retention and obligation to work while sick may depend on perceived spouse support, highlighting the important role husbands play in their wives’ professional lives. Findings also lend support to the emerging literature on marriage-to-work positive spillover, and suggest that long-term care organizations should target marital relationships in family-friendly initiatives to retain and engage double-and-triple-duty caregiving employees.

Keywords: Long-term care, Family care, Job retention, Job performance, Spouse support

In 2014, 90% of registered nurses and 89% of nursing assistants and licensed practical nurses were women (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). In that same year, women represented 60% of U.S. adults informally caring for children or adults (National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC), 2015). Women’s dominance in paid and unpaid care has contributed to the growing number of health care employees who simultaneously serve as family caregivers, or double-and-triple-duty caregivers (DePasquale et al., 2016a). Health care employees tend to become family caregivers because they usually are the only “health professional in the family,” and family members rely heavily on their expertise (Ward-Griffin, Brown, Vandervoort, McNair, & Dashnay, 2005, p. 384). Relatedly, women health care employees often face gendered expectations (e.g., caregiving is “women’s work”) that strongly influence their involvement in family care (Rutman, 1996, p. 90; Ward-Griffin et al., 2015). Although double-and-triple-duty caregiving experiences will become more common as the demand for paid and unpaid care increases, women who combine paid and unpaid caregiving roles remain an understudied workforce segment (DePasquale et al., 2016a). To enhance understanding of their work–family interface, we examine job retention and performance factors among married women working in U.S.-based nursing homes, most of whom have informal child and/or elder care obligations.

Double-and-Triple-Duty Caregivers’ Work Experiences

In 2015, 89% of families with residential children less than 18 years had at least one employed parent (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). Further, an estimated 60% of adults who informally cared for relatives or friends aged 18 or older also balanced a work role in 2014 (NAC, 2015). Research suggests that combining work and caregiving roles may have several occupational impacts like reducing hours; experiencing poorer performance and attendance as well as greater emotional exhaustion and workday interruptions; and quitting or retiring early (Boštjančič, Kocjan, & Stare, 2015; NAC, 2015). Further, working caregivers experience physical, emotional, and financial strain (Duxbury, Higgins, & Smart, 2011), and are more likely to report high caregiver burden than nonworking counterparts (Hsu et al., 2014). The majority of research on the work implications of different unpaid caregiving roles, however, has been on a general population of employees. Studies that account for the specific type of industry in which caregivers work are needed to better understand how unpaid caregiving roles affect employment experiences within industries as well as inform approaches to addressing such experiences.

Researchers focused on unpaid caregiving roles within the context of health care employment typically use double-and-triple-duty caregiving terminology to distinguish family caregiving health care employees from their nonfamily caregiving counterparts, or workplace-only caregivers (DePasquale et al., 2016a; Rutman, 1996; Ward-Griffin et al., 2005). Double-and-triple-duty caregivers are health care employees who informally care for individuals beyond those in the health care setting, including children (double-duty-child caregivers) older adults (double-duty-elder caregivers), or both children and older adults (triple-duty caregivers). Because formal and family caregiving have traditionally been studied separately, double-and-triple-duty caregiving literature is limited (Ward-Griffin et al., 2015). The research presented here expands on the emerging literature concerning double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ work experiences.

Specifically, we examine workplace factors linked to job retention (i.e., job satisfaction and turnover intentions) and performance (i.e., perceived obligation to work while sick and emotional exhaustion) given that each can have serious implications for employees, care recipients, and long-term care organizations. For example, job satisfaction and turnover intentions are related to actual turnover; turnover has wide-ranging consequences, including extreme workload burdens, higher stress levels, and lower job satisfaction within the existing workforce; compromised quality of care; and numerous system costs (e.g., overtime pay), all of which beget additional turnover in long-term care organizations (Castle, Engberg, Anderson, & Men, 2007; Hayes et al., 2011; Rosen, Stiehl, Mittal, & Leana, 2011; Stone, 2012). Further, perceived obligation to work while sick (hereafter obligation to work while sick) may be indicative of presenteeism, or attending work while ill (Johns, 2010). Presenteeism is linked to individual job performance deficits; collective job performance deficits; high organizational costs from lost job productivity; and infectious disease transmission that jeopardizes employees’ and care recipients’ health (Letvak & Ruhm, 2010; Widera, Chang, & Chen, 2010). Moreover, long-term care employees’ emotional exhaustion is positively correlated with risk of absenteeism, sick-leave duration, and care recipient abuse, neglect, and criticism, as well as negatively related to quality of care and preparedness to manage care recipients’ emotional needs (Goergen, 2001; Sanchez, Mahmoudi, Moronne, Camonin, & Novella, 2015; Tanaka et al., 2015; Westermann, Kozak, Harling, & Nienhaus, 2014).

To date, researchers have not compared U.S.-based, married workplace-only and double-and-triple-duty caregiving women on job retention and performance factors. Instead, such comparisons have been made between workplace-only caregivers and U.S.-based double-and-triple-duty caregiving men (DePasquale et al., 2016c), U.S.-based double-and-triple-duty caregiving certified nursing assistants (CNAs; DePasquale et al., in press), Netherlands-based double-duty caregivers (Boumans & Dorant, 2014; Dorant & Boumans, 2016), and Canadian-based double-duty caregiving registered nurses (Stewart et al., 2011). Evidence yielded from this small body of research suggests that double-and-triple-duty caregivers generally report similar job satisfaction and more emotional exhaustion compared to workplace-only caregivers, although there are exceptions to these trends. Similarly, some studies have detected lower turnover intentions among double-duty caregivers whereas others have not. Thus far, the felt obligation driving presenteeism has been overlooked but presenteeism itself has been examined among double-duty caregivers; they exhibit more presenteeism than workplace-only caregivers.

To elucidate double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ work experiences, researchers have applied the role scarcity and expansion hypotheses, two competing perspectives within role theory. The role scarcity hypothesis suggests that individuals have limited time, energy, and other personal resources to invest in roles (Goode, 1960). Because demands accompany every role, role multiplicity creates competition for these zero-sum resources. Consequently, individuals with larger role sets risk total role demands exceeding total resource availability; such a demands-rewards differential leads individuals to experience variants of role strain, or felt difficulty addressing role demands, like overload (i.e., time constraints) and/or conflict (i.e., competing role obligations or discrepant role expectations). Applying this logic to the present study, double-and-triple-duty caregivers will fare worse on job retention and performance factors relative to workplace-only caregivers because of their additional caregiving roles.

Conversely, role expansion theorists argue that role multiplicity is more beneficial than stressful (Marks, 1977; Sieber, 1974). Role resources are considered abundant or flexible, meaning that they can be sustained or generated when occupying multiple roles. Resources from one role can compensate for resource deficits in others, negative experiences in one role can buffer positive experiences in another role, and positive aspects of one role can have additive effects by enhancing other role experiences. These positive aspects of role multiplicity facilitate multiple role management and integration, subsequently producing fewer negative and more positive outcomes. Compared to workplace-only caregivers, then, double-and-triple-duty caregivers will fare better or similarly on job retention and performance factors because of their additional caregiving roles.

The aforementioned research on double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ work experiences has produced mixed results and thus precludes strong conclusions, particularly about married women employed in nursing homes. Accordingly, our first objective was to examine whether the role scarcity or expansion hypothesis is generally more applicable when comparing workplace-only and double-and-triple-duty caregivers on job retention and performance factors.

Marriage-to-Work Positive Spillover

Although their conclusions differ, both the role scarcity and expansion hypotheses explain how perceived resource possession may affect multiple role occupants’ work experiences. Yet, perceived resource possession is not explicitly conceptualized as a moderator in either hypothesis. Our focus on married women affords us the opportunity to test such a conceptualization by examining the moderating effects of husbands’ support, a contextual resource from the family domain (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), on double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ work domain.

Prior qualitative studies have highlighted the benefits of perceived spouse support (hereafter referred to as spouse support) for double-and-triple-duty caregiving women’s family domain. For instance, double-duty-elder caregivers credit their husbands with helping them “put things into perspective” and staying “grounded” while providing family care (Ward-Griffin et al., 2005, p.386). In other interviews, double-and-triple-duty caregivers with “very supportive, understanding, and helpful” husbands reported high satisfaction and low stress levels at home; they also acknowledged that support from and clear, consistent communication with their husbands created a positive family environment (Ross, Rideout, & Carson, 1996, p. 51). Conversely, those with problematic marital relationships often reported low satisfaction and high stress levels at home. Whether these benefits of spouse support extend to double-and-triple-duty caregiving women’s work experiences, though, remains unexplored.

Broadly, the process whereby individuals’ experiences in either the work or family domain influence their experiences in the other domain is termed spillover (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Wethington, 1989). Spillover creates between-domain similarities through the intraindividual transmission of affect or mood, values, skills, and behaviors (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Hanson, Hammer, & Colton, 2006). These similarities can be positive (e.g., satisfaction at home increases satisfaction at work) or negative (e.g., contentious coworker interactions adversely affect family interactions; Edwards & Rothbard, 2000). Marriage-to-work positive spillover, a specific form of family-to-work positive spillover, occurs when the marital relationship has beneficial work role effects (Crouter, 1984). In this study, we view marriage-to-work positive spillover as a possible mechanism through which husbands’ support transcends the family domain to positively impact job retention and performance factors among their double-and-triple-duty caregiving wives.

Prior research on marriage-to-work positive spillover suggests that greater marital satisfaction is linked to higher job satisfaction (Braybrook, Coleman, Houlston, Martin, & Green, 2015; Nasir & Sakdiah, 2010; Rogers & May, 2003; Sandberg, Yorgason, Miller, & Hill, 2012). These findings are likely generalizable to spouse support, as marital satisfaction is indicative of supportive marital relations (Nasir & Sakdiah, 2010). Indeed, a meta-analysis on work–family domain relations found that family domain support, a composite measure including spouse support, was positively correlated with job satisfaction (Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007). Other research has also shown that individuals with emotionally supportive spouses assess their job more positively (McAllister, Thornock, Hammond, Holmes, & Hill, 2012). Nonetheless, this literature is still developing (Sandberg et al., 2013). Family-to-work spillover was labeled “the neglected side of the work-family interface” over 30 years ago (Crouter, 1984, p. 425) and continues to be understudied in favor of work-to-family spillover (Braybrook et al., 2015). Relatedly, considerably more attention has been given to negative family-to-work spillover (Sandberg et al., 2012). Researchers have thus called for investigations that examine family-to-work positive spillover (e.g., Braybrook et al., 2015) within a range of workplace settings (Sandberg et al., 2012). Therefore, our second objective was to assess whether the family domain resource of husbands’ support also functions as a work domain resource for wives with double-and-triple-duty caregiving roles.

Methods

Data come from the Work, Family and Health Study (WFHS), a research initiative by the Work, Family and Health Network (WFHN) to examine long-term care employees’ work, family life, and health outcomes. Detailed information about the WFHS protocol has been described elsewhere (Bray et al., 2013). Briefly, the WFHN partnered with a long-term health and specialized care company in New England that managed 56 nursing homes, 30 of which were selected for research participation. Facilities were excluded if they were recently acquired or had fewer than 30 direct-care employees; none declined participation. Within each facility, employees were eligible for participation if they provided direct care, worked at least 22.5 hours per week, and did not exclusively do night work. Of 1,783 eligible employees, 1,524 (85%) enrolled, 590 of whom were married women. We limited this sample to heterosexual women (n = 583) without missing data on study variables (n= 573). We then excluded women married to men who were unemployed because of medical-related reasons, imprisonment, or unspecified reasons to keep the focus on relatively healthy husbands living at home, resulting in a final sample of n = 546. Sample characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Double-and-Triple-Duty Caregiving Role Occupancy

| Characteristics, n (%) | Overall, n = 546 | Workplace-only caregiver, n = 186 (34%) | Double-duty-child caregiver, n = 208 (38%) | Double-duty-elder caregiver, n = 66 (12%) | Triple-duty caregiver, n = 86 (16%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.54 (11.32) | 48.12 (12.24) | 37.12 (7.53)*** | 49.68 (11.33) | 38.10 (7.71)*** |

| White | 71% | 77% | 66%† | 79% | 64% |

| Postsecondary education | 66% | 74% | 63% | 61% | 62% |

| Annual household income | 11.14 (2.56) | 11.26 (2.65) | 10.96 (2.60) | 11.26 (2.54) | 11.22 (2.32) |

| Child disability | 10% | 0% | 17%*** | 0% | 23%*** |

| Nonresidential children <18 years | 8% | 18% | 0%*** | 20% | 0%*** |

| Company tenure | 7.89 (7.48) | 9.69 (8.97) | 5.88 (5.37)*** | 10.71 (8.87) | 6.72 (5.38)** |

| Hours worked | 36.69 (7.02) | 37.49 (7.18) | 36.06 (7.15) | 36.79 (5.23) | 36.37 (7.48) |

| Certified nursing assistant | 55% | 51% | 56% | 60% | 59% |

| Marital duration | 15.66 (12.24) | 20.80 (14.02) | 11.01 (7.85)*** | 21.91 (14.00) | 11.02 (8.32)*** |

| Employed spouse | 82% | 78% | 85% | 80% | 88% |

| Hours spouse works | 44.24 (12.30) | 43.04 (11.83) | 44.55 (12.07) | 44.87 (13.11) | 45.33 (13.16) |

| Spouse support | 18.07 (2.60) | 18.37 (2.54) | 17.95 (2.53) | 18.27 (2.01) | 17.55 (3.21)† |

Note: Means (and standard deviations) or percentages are shown. Workplace-only caregivers constitute the reference group. Annual household income was equivalent to $50,000–54,999 per year (11) for all groups. Spouse support scores ranged from 5 to 20, with higher scores indicating more support.

† p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Procedures

Trained field interviewers conducted computer-assisted personal interviews at the workplace. Employees answered questions about work experiences, well-being, and family relationships, for which they received $20. Interviews averaged 60 minutes.

Measures

Predictors

Consistent with prior research (e.g., DePasquale et al., 2016a; Scott et al., 2006), we categorized women into mutually exclusive workplace-only and double-and-triple-duty caregiving groups. Double-duty-child caregivers lived with children aged 18 or younger for at least four days per week. Double-duty-elder caregivers provided care (i.e., help with shopping, medical care, or financial/budget planning) for at least 3 hours per week in the past 6 months to an adult relative, regardless of residential proximity. Triple-duty caregivers satisfied each double-duty caregiving criterion whereas workplace-only caregivers did not fulfill either criterion.

Overall, 34% (n = 186) of women were workplace-only; 38% (n = 208), double-duty-child; 12% (n = 66), double-duty-elder; and 16% (n = 86), triple-duty caregivers. On average, double-duty-child and triple-duty caregivers resided with dependent children aged 7.32 (SD = 5.16) and 8.67 (SD = 5.09), respectively. Although women’s relation to adult care recipients was unspecified, qualitative data from WFHS participants suggests that they often cared for parents with declining health (DePasquale et al., 2016a).

Moderator

Spouse support (see Table 2) was measured with a 5-item scale from Schuster, Kessler, and Aseltine (1990). Response options ranged from not at all (1) to a lot (4) in the past month. Higher scores reflect more spouse support.

Table 2.

Characteristics and Psychometric Properties of Moderator and Outcome Variables

| Construct | Measure or source | Items | Mean score (SD) | Cronbach’s alpha | Convergent validity | Divergent validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [range] | ||||||

| Spouse support | Schuster, Kessler, & Aseltine (1990) | 1. Does your spouse really care about you? | 18.07 (2.60) | .84 | .43–.64 | .00 to −1.8 |

| [5–20] | ||||||

| 2. Does he understand the way you feel about things? | ||||||

| 3. Does he appreciate you? | ||||||

| 4. Can you open up to him if you need to talk about your worries? | ||||||

| 5. Can you relax or be yourself around him? | ||||||

| Job satisfaction | Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire | 1. In general, you like working at your job. | 4.29 (0.60) | .83 | .58–.72 | .01 to −.49 |

| [2–5] | ||||||

| 2. In general, you are satisfied with your job. | ||||||

| 3. You are generally satisfied with the kind of work you do in this job. | ||||||

| Turnover intentions | Boroff & Lewin (1997) | 1. You are seriously considering quitting your company for another employer. | 1.95 (0.97) | .85 | .74 | −.02 to −.49 |

| [1–5] | ||||||

| 2. During the next 12 months, you will probably look for a new job outside of this company. | ||||||

| Obligation to work while sick | Moen, Kelly, Tranby, & Huang (2011) | 1. When you are sick, you still feel obligated to come into work. | 3.81 (1.14) | – | – | – |

| [1–5] | ||||||

| Emotional exhaustion | The Maslach Burnout Inventory | 1. You feel emotionally drained from your work. How often do you feel this way? | 4.29 (1.65) | .87 | .67–.73 | .00 to .37 |

| [1–7] | ||||||

| 2. You feel burned out by your work. How often do you feel this way? | ||||||

| 3. You feel used up at the end of the work day. How often do you feel this way? |

Note: Numbers for convergent and divergent validity represent lowest-highest Pearson correlation coefficients. Both the lowest and highest correlation coefficients were significant at p < .001 for all convergent correlations. The lowest correlation coefficient for divergent validity was nonsignificant across cross-construct correlations; the highest correlation coefficient for divergent validity was significant at p < .001 for all cross-construct correlations. All correlations for convergent and divergent validity account for item overlap.

-Not computable.

Outcomes

Unless noted otherwise, outcome response options ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). For all outcomes, higher scores translate to a higher degree of the construct being examined (see Table 2). Job satisfaction was examined with a 3-item subscale from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire reflecting global, affective job satisfaction (Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, & Klesh, 1983). Turnover intentions were evaluated with a 2-item scale reflecting intentions to quit the work role (Boroff & Lewin, 1997). Obligation to work while sick was examined with one item regarding felt obligation to attend work when ill (Moen, Kelly, Tranby, & Huang, 2011). Emotional exhaustion was measured with a 3-item subscale from The Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach & Jackson, 1986), which assessed feelings of being emotionally overextended by one’s work. Responses ranged from never (1) to every day (7).

Covariates

We considered several covariates based on their potential to affect study constructs. We selected age (in years), race (1 = White, 0 = non-White), and the presence of disabled dependent children at home (1 = yes, 0 = no) given their links to double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ stress and work-family conflict (DePasquale et al., 2016a). Additionally, company tenure (in years) and hours worked per week have differed between workplace-only and double-and-triple-duty caregivers in past studies (Boumans & Dorant, 2014; DePasquale et al., in press, 2016b); we examined these variables to minimize potential confounding effects. Further, we considered women’s occupation (1 = CNA, 0 = other), educational attainment (1 = postsecondary education, 0 = no postsecondary education), and annual household income (1 = less than $4,999, 13 = more than $60,000) because of their relation to marital intimacy and work–family interface challenges (McAllister et al., 2012). As well, we included an indicator for nonresidential children (1 = yes, 0 = no) to account for care or support to children aged 18 and older (e.g., financial support, Wiemers & Bianchi, 2015). Marital duration (in years), husbands’ employment status (1 = employed, 0 = not employed), and husbands’ work hours were also assessed for their potential association with marital quality (Rogers & May, 2003).

Statistical Analyses

We initially estimated univariate regressions to examine whether each potential covariate predicted job retention and performance factors. These analyses revealed that age and marital duration predicted all job and retention factors. Additionally, postsecondary education was linked to job satisfaction; race, hours worked per week, company tenure, and nonresidential children were related to turnover intentions; race and child disability predicted obligation to work while sick; and occupation was related to emotional exhaustion. Because covariates that are not associated with dependent variables may generate spurious associations between variables (Rovine, von Eye, & Wood, 1988), only the aforementioned variables were included in our analytic models. Given the strong correlation between age and marital duration (r = .75, p < .001), however, both variables could not be included in models simultaneously. We therefore conducted our analytic models twice, once with age and once with marital duration; we retained whichever covariate was significant in our final models. In the event that both covariates were significant predictors, we retained the variable with the better model fit.

Next, because women were nested within different nursing homes, we calculated intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) to determine whether analytic models should account for between-facility variance. These ICCs indicated that nearly all variance in the outcome measures was attributable to between-person differences. Under the reasonable assumption of statistical independence between facilities, we then estimated two multiple linear regression models per outcome. Model 1 included dichotomous indicators for double-and-triple-duty caregiving roles (with workplace-only caregivers as the reference group), spouse support, and covariates. Model 2 entailed a moderation analysis in which each double-and-triple-duty caregiving role interacted with spouse support. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 presents sample characteristics by double-and-triple-duty caregiving roles. Compared to the workplace-only caregiving group, the double-duty-child and triple-duty caregiving groups were younger, had shorter company tenure and marital durations, and, by definition, some lived with disabled children but none had nonresidential children older than 18 years.

Substantive Analyses

Direct Associations

In Model 1, longer marital duration was associated with more job satisfaction (B = .01, SE = .002, p < .05). Women who were White (B = −.20, SE = .09, p < .05), worked more hours (B = −.01, SE = .01, p < .05), and had longer company tenure (B = −.03, SE = .01, p < .001) reported lower turnover intentions. Those who were older (B = −.02, SE = .01, p < .01) felt less obligated to work while sick whereas women who were White (B = .52, SE = .11, p < .001) or lived with disabled children (B = .41, SE = .16, p < .05) felt more obligated to work while sick. Further, a 1-year increase in age (B = −.03, SE = .01, p < .001) and the CNA position (B = −.44, SE = .14, p < .01) were both linked to less emotional exhaustion. Turning to the central focus of this study (Table 3), double-duty-elder and triple-duty caregivers reported more emotional exhaustion than workplace-only caregivers.

Table 3.

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Results

| Job retention factors | Job performance factors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | Turnover intentions | Obligation to work while sick | Emotional exhaustion | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Intercept | 4.37 (.06)*** | 4.36 (.06)*** | 2.11 (.10)*** | 2.09 (.10)*** | 3.41 (.12)*** | 3.39 (.12)*** | 4.35 (.15)*** | 4.34 (.15)*** |

| DDCC | −.004 (.07) | −.001 (.07) | .002 (.11) | .01 (.11) | −.05 (.13) | −.02 (.13) | .10 (.18) | .11 (.18) |

| DDEC | .09 (.09) | .09 (.09) | .02 (.14) | .04 (.14) | .13 (.16) | .16 (.16) | .58 (.23)* | .61 (.23)** |

| Triple-duty care | −.09 (.08) | −.11 (.08) | −.03 (.13) | .01 (.13) | −.09 (.16) | −.07 (.16) | .47 (.22)* | .53 (.22)* |

| Spouse support | .004 (.01) | .003 (.02) | −.03 (.02)† | .01 (.03) | −.05 (.02)** | .02 (.03) | −.08 (.03)** | −.06 (.05) |

| DDCC * spouse support | .03 (.02) | −.09 (.04)* | −.11 (.04)* | −.07 (.06) | ||||

| DDEC * spouse support | .02 (.04) | −.05 (.06) | −.15 (.07)** | −.16 (.11) | ||||

| Triple-duty care * spouse support | −.04 (.03) | .02 (.04) | −.09 (.05)* | .06 (.07) | ||||

| R 2 | .02 | .03 | .06 | .07 | .07 | .08 | .07 | .08 |

| ΔR2a | .006 | .012† | .005 | .016* | .015† | .015* | .036*** | .010 |

Note: DDCC = double-duty-child caregiver, DDEC = double-duty-elder caregiver. Unstandardized regression coefficients (and standard errors) are displayed for all models. All continuous variables are mean-centered. Workplace-only caregivers constituted the reference group for double-and-triple-duty caregiving role occupancy predictors. Marital duration and postsecondary education are controlled for in the job satisfaction models. Race, hours worked per week, company tenure, and nonresidential children are controlled for in the turnover intentions models. Age, race, and child disability are controlled for in the obligation to work while sick models. Age and occupation are controlled for in the emotional exhaustion models.

aThe change in R-squared for Model 1 represents the change from a covariates-only model to a model with both covariates and substantive predictors (i.e., double-and-triple-duty caregiving role occupancies and spouse support).

† p < .10, *p ≤ .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Moderation Analyses

In Model 2 (Table 3), the addition of interaction terms led to a significant increase in the proportion of variance explained for turnover intentions and obligation to work while sick. In these models, spouse support interacted with double-duty-child caregiving to predict turnover intentions and also conditioned associations between double-duty-child, double-duty-elder, and triple-duty caregiving and obligation to work while sick. Follow-up simple slopes tests revealed that, for every 1-unit increase in spouse support, double-duty-child caregivers reported lower turnover intentions (B = −.09, SE = .03, p < .01). Greater spouse support was also associated with less obligation to work while sick for double-duty-child (B = −.09, SE = .03, p < .01), double-duty-elder (B = −.13, SE = .07, p ≤ .05), and triple-duty (B = −.07, SE = .04, p ≤ .05) caregivers.

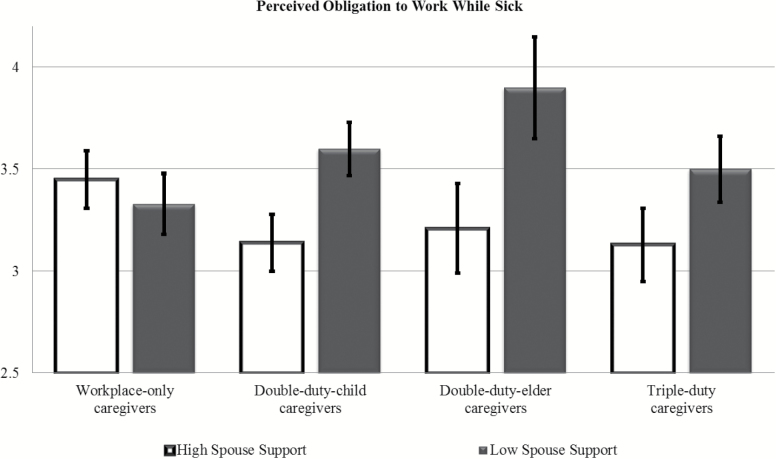

We further probed interaction effects by computing model-estimated means for each factor at high (one standard deviation above the mean) and low (one standard deviation below the mean) values of spouse support. In the context of high spouse support, double-duty-child caregivers had lower turnover intentions scores (M = 1.68, SE = .11) relative to such scores in the presence of low spouse support (M = 2.12, SE = .12). Double-duty-child, double-duty-elder, and triple-duty caregivers also had lower and higher obligation to work while sick scores in the context of high and low spouse support, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Model-estimated means for the conditional effects of double-and-triple-duty caregiving role occupancy on perceived obligation to work while sick at one standard deviation above (high spouse support) and below (low spouse support) the mean of spouse support. Higher scores reflect greater perceived obligation to work while sick. Double-duty-child (M = 3.14, SE = .14), double-duty-elder (M = 3.21, SE = .22), and triple-duty (M = 3.13, SE = .18) caregivers had lower perceived obligation to work while sick scores in the context of high spouse support relative to scores in the presence of low spouse support (double-duty-child caregivers: M = 3.60, SE = .13; double-duty-elder caregivers: M = 3.90, SE = .25; triple-duty caregivers: M = 3.50, SE = .16).

Discussion

This study had two objectives. First, we compared workplace-only and double-and-triple-duty caregivers on job retention and performance factors. Drawing on a sample of 546 married women working in U.S.-based nursing homes, we found that the role expansion hypothesis (Marks, 1977; Sieber, 1974) was generally more applicable to these direct associations. Compared to workplace-only caregivers, double-and-triple-duty caregivers did not differ in job satisfaction, turnover intentions, or obligation to work while sick. Workplace-only and double-duty-child caregivers also reported similar emotional exhaustion levels. These similarities complement those from past studies (Boumans & Dorant, 2014; DePasquale et al., 2016c; Dorant & Boumans, 2016) and suggest that different family caregiving roles can be integrated into married, women long-term care employees’ role repertoires with minimal implications for job retention as well as obligation to work while sick.

Based on the role expansion hypothesis (Marks, 1977; Sieber, 1974), there are several possible explanations for the previously described null findings. For example, double-and-triple-duty caregivers credit their family caregiving roles with helping them understand and address formal care recipients’ and their family members’ needs, concerns, and stress (Wohlgemuth et al., 2015). Such effects on the work role may lead to more gratifying interactions with formal care recipients and their family members that, in turn, leave double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ job satisfaction as high as that of workplace-only caregivers. Relatedly, double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ work role enables them to use their health care connections and professional status to benefit their unpaid care work (e.g., securing consultations with busy specialists, Ward-Griffin et al., 2005, 2015); these advantageous work role features may negate its disadvantageous features, ultimately reducing turnover intentions. As for obligation to work while sick, the majority of this sample was in dual-earner partnerships. Thus, overall, shared responsibility for maintaining financial stability for family care may mitigate double-and-triple-duty caregiving women’s perceived pressure to prioritize the work role over their own health.

Consistent with prior research (Boumans & Dorant, 2014; DePasquale et al., in press, 2016c; Dorant & Boumans, 2016), two direct associations upheld the role scarcity hypothesis (Goode, 1960)—double-duty-elder and triple-duty caregivers reported more emotional exhaustion. One potential explanation for these findings involves the emotional experiences associated with different family caregiving roles. Prior research indicates that adult caregivers rate caregiving activities as less meaningful, sadder, and more painful than child caregivers (Hammersmith & Lin, 2016). Further, health care employees consider emotion regulation to be particularly difficult when providing family care (e.g., displaying stoicism; Wohlgemuth et al., 2015). Accordingly, double-duty-child caregivers’ resources for emotion regulation may predominately be expended at work, leaving them better equipped to manage workplace emotional exhaustion. Conversely, quicker resource depletion from care-related emotion regulation across domains may exacerbate double-and-triple-duty caregivers' emotional exhaustion (DePasquale et al., 2016c).

Second, guided by the conceptual framework of family-to-work positive spillover (Crouter, 1984), we examined whether spouse support functioned as a work resource for double-and-triple-duty caregiving wives. With greater spouse support, double-duty-child caregivers reported lower turnover intentions. One plausible reason for these findings is that greater spouse support reflects less marital distress, which may be indicative of fewer spousal conflicts, a fairer division of household labor, or a more fun relationship (Sandberg et al., 2012); such relationship characteristics may function as “a renewable source of energy” that lets women feel rejuvenated in and better able to manage work role demands (McAllister et al., 2012, p.331). Relatedly, more spouse support may facilitate resource acquisition that neutralizes negative work experiences because resources are not being expended on marital problems (Braybrook et al., 2015; Rogers & May, 2003; Sandberg et al., 2013). Another possibility is that positive experienced well-being linked to child care activities (Hammersmith & Lin, 2016), coupled with greater spouse support, produces synergistic effects that decrease turnover intentions.

Greater spouse support was also inversely associated with obligation to work while sick for all double-and-triple-duty caregivers. Supportive husbands may attenuate double-and-triple-duty caregiving wives’ obligation to work while sick by conveying concern for their health or encouraging self-care, alleviating guilt about missing work, or managing family care responsibilities temporarily. Although such support buffered obligation to work while sick across unpaid caregiving roles, it had the most impact on double-duty-elder caregivers. One probable explanation for this finding is that double-and-triple-duty caregiving women are slightly more inclined to attend work while ill because of job security or income-related concerns related to dependent children living at home. This inclination may not be as strong among double-duty-elder caregivers because their care recipients could live elsewhere and be financially stable.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several aspects of this study could be expanded upon in future research. First, analyses were cross-sectional. A longitudinal approach would enable researchers to assess the dynamic qualities of multiple caregiving roles and work experiences. Second, nonprobability sampling may limit the generalizability of study findings. Nationally representative samples would be ideal. Similarly, this study was restricted to married, heterosexual women. Future studies should include more diverse samples of partnered women when possible. Third, we conducted a secondary analysis of existing data, meaning that scales and scoring conventions were largely predetermined. Some measures employed here have been adapted or modified and therefore do not precisely align with standard practices, which may hinder comparisons across studies. On a related note, we relied on a relatively broad measure of spouse support. To examine more nuanced forms of spouse support, researchers should treat affective- and instrumental-based sub-dimensions of spouse support as distinct constructs (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Hanson et al., 2006). Fourth, our study is based on wives’ perceptions of husbands’ support. Later investigations could use couple-level data and methodologies that capture interaction processes in the marital dyad and enhance understanding of the marital context.

Finally, the WFHS was not specifically designed to study family caregivers. Consequently, we lacked ideal information regarding family caregiving experiences and used available measures to construct family caregiving role occupancy indicators in accordance with prior studies (e.g., DePasquale et al., 2016b; Scott et al., 2006). These available measures led us to operationalize child and elder care differently such that double-duty-child caregiving classifications are based on a child's age and living arrangements, whereas double-duty-elder caregiving classifications are based on actual care provision. Further, despite our application of double-duty-elder care terminology, the adult care measure used here could encompass care for adult relatives other than aging parents, such as siblings. These measures are advantageous relative to double-and-triple-duty caregiving measures in past research (Boumans & Dorant, 2014; Dorant & Boumans, 2016; Stewart et al., 2011; Wohlgemuth et al., 2015), though, in that they differentiate double-duty caregivers; enable consideration of triple-duty caregivers; and include a criterion for weekly hours of adult care. Still, researchers should use more detailed measures as they may yield new insights into the double-and-triple-duty caregiving experience. Relatedly, the overall variance explained by our regression models was relatively low across job performance and retention factors. Unmeasured family caregiving constructs, such as time spent engaging in specific care activities; caregiving duration; subjective and objective caregiver burden; informal and formal supports; and adult care recipients’ age, health status, behavior problems, and relation to double-and-triple-duty caregivers may explain more variance than models that only include family caregiving role occupancy predictors and therefore warrant consideration in future research.

In light of these limitations, replication is critical if we are to advance understanding of why husbands’ support did not buffer double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ emotional exhaustion. It is currently unclear if husbands’ support is insufficient for overcoming emotional exhaustion experienced in the long-term care environment or more nuanced support measures would produce different results. Likewise, husbands’ support was not a resource for all double-and-triple-duty caregiving roles across any job retention factors and only one performance factor. Additional evidence is needed to determine if husbands’ support is more pertinent for certain factors and double-and-triple-duty caregiving roles. Nonetheless, our study lays groundwork for future work and has several strengths, such as expanding literature on double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ job retention and performance factors to married women working in U.S.-based nursing homes; providing a more precise test of role theory by comparing health care employees with the same work context, gender, and marital status; building on qualitative research of a family domain resource with a quantitative examination; and extending research on family-to-work positive spillover to the long-term care setting as well as the double-and-triple-duty caregiving experience.

Practical Implications

The present study lends support to the notion that “what is good for the couple is good for work” (McAllister et al., 2012, p. 331). Our findings suggest that family-friendly initiatives targeting marriage-to-work positive spillover may represent opportunities for long-term care organizations to attract, retain, and engage double-and-triple-duty caregiving employees. One such initiative is an employee assistance program that provides counseling for employees and their spouses (McAllister et al., 2012). Because spouse support has been linked to both marital and job satisfaction in prior research, counseling services should target constructive, supportive, and respectful communication patterns as well as emphasize the nature of each spouse’s work role, responsibilities, and demands to encourage mutual respect and understanding within the marital relationship (Nasir et al., 2010). Long-term care organizations could also shift existing career counseling services toward a more holistic paradigm that acknowledges the work–family interface by providing family and marriage counseling (Nasir et al., 2010). Merely implementing these initiatives, however, is not necessarily sufficient to guarantee employee utilization; supervisors and managers should receive relevant training in and encourage their use (Braybrook et al., 2015).

Although long-term care organizations may be hesitant to invest in programs or policies that target family domain influences, findings from this study complement growing evidence that such investments make business sense (Ford et al., 2007; McAllister et al., 2012). For example, if our moderation findings pertaining to turnover intentions and obligation to work while sick are indicative of actual turnover and presenteeism, then such investments could yield a positive return-on-investment via reductions in turnover-related and productivity-related costs, more stability and continuity in the workforce, and better health outcomes among employees and care recipients (Hayes et al., 2011; Letvak & Ruhm, 2010; Widera, Chang, & Chen, 2010). Relatedly, long-term care organizations may further benefit if their initial investment in marriage-to-work positive spillover effects evolve into marriage-to-work positive crossover effects (i.e., individual benefits from couples-based workplace initiatives create positive experiences for other employees and care recipients).

Conclusion

This study compared married workplace-only and double-and-triple-duty caregiving women on workplace factors related to job retention and performance as well as examined whether double-and-triple-duty caregiving women’s perceptions of their husbands’ support benefited their professional lives. Overall, the role expansion hypothesis was more applicable to direct associations than the role scarcity hypothesis. More specifically, double-and-triple-duty caregivers generally did not differ from their workplace-only caregiving counterparts on job retention and performance factors. These null findings suggest that different family caregiving roles can be integrated into married, women long-term care employees’ role repertoires with minimal implications for job retention as well as obligation to work while sick. Results also indicated that, with greater spouse support, double-duty-child caregivers’ turnover intentions were attenuated and double-and-triple-duty caregivers’ obligation to work while sick was mitigated. These findings lend support to the notion of marriage-to-work positive spillover, and suggest that long-term care organizations should consider initiatives that strengthen employees’ marital relationships.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the Work, Family and Health Network (www.WorkFamilyHealthNetwork.org), which is funded by a cooperative agreement through the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant # U01HD051217, U01HD051218, U01HD051256, U01HD051276), National Institute on Aging (Grant # U01AG027669), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Grant # U01OH008788, U01HD059773). Grants from the William T. Grant Foundation, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and the Administration for Children and Families have provided additional funding. Nicole DePasquale was supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant F31AG050385. Courtney A. Polenick was supported by training grant T32 MH073553-11 (Stephen J. Bartels, Principal Investigator) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of these institutes and offices.

Acknowledgments

Special acknowledgement goes to Extramural Staff Science Collaborator, Rosalind Berkowitz King, PhD, and Lynne Casper, PhD, for design of the original Workplace, Family, Health and Well-Being Network Initiative. We also wish to express our gratitude to the worksites, employers, and employees who participated in this research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bolger N. DeLongis A. Kessler R.C., & Wethington E (1989). The contagion of stress across multiple roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51, 175–183. doi:10.2307/352378 [Google Scholar]

- Boroff K.E., & Lewin D (1997). Loyalty, voice, and intent to exit a union firm: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 51, 50–63. doi:10.1177/001979399705100104 [Google Scholar]

- Boštjančič E. Kocjan G., & Stare J (2015). Role of socio-demographic characteristics and working conditions in experiencing burnout. Suvremena Psihologija, 18(1), 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Boumans N. P., & Dorant E (2014). Double-duty caregivers: healthcare professionals juggling employment and informal caregiving. A survey on personal health and work experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(7), 1604–1615. doi:10.1111/jan.12320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray J.W. Kelly E.L. Hammer L.B. Almeida D.M. Dearing J.W. King R.B., & Buxton O.M (2013). An integrative, multilevel, and transdisciplinary research approach to challenges of work, family, and health. RTI Press publication No. MR-0024-1303. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press. doi:10.3768/rtipress.2013.mr.0024.1303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braybrook D. Coleman L. Houlston C. Martin A., & Green H (2015). Improving work outcomes: The value of couple and family relationships. Literature Review. Retreived from http://www.oneplusone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Improving-work-outcomes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). Employment characteristics of families—2015. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/famee.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015). Women in the labor force: A databook. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-databook/archive/women-in-the-labor-force-a-databook-2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cammann C. Fichman M. Jenkins G.D., & Klesh J (1983). “Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire.” In S.E. Seashore E.E. Lawler P.H. Mirvis, & C. Cammann (Eds.), Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices (pp. 71–138). New York: Wiley-Interscience. [Google Scholar]

- Castle N.G. Engberg J. Anderson R., & Men A (2007). Job satisfaction of nurse aides in nursing homes: Intent to leave and turnover. The Gerontologist, 47, 193–204. doi:10.1093/geront/47.2.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter A.C. (1984). Spillover from family to work: The neglected side of the work-family interface. Human Relations, 37, 425–442. doi:10.1177/001872678403700601 [Google Scholar]

- DePasquale N. Davis K. D. Zarit S. H. Moen P. Hammer L. B., & Almeida D. M (2016a). Combining formal and informal caregiving roles: The psychosocial implications of double- and triple-duty care. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 71(2), 201–211. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePasquale N. Bangerter L. R. Williams J., & Almeida D. M (2016b). Certified nursing assistants balancing family caregiving roles: Health care utilization among double- and triple-duty caregivers. The Gerontologist, 56(6), 1114–1123. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePasquale N. Zarit S.H. Mogle J. Moen P. Hammer L.B., & Almeida D.M (2016c). Double-and triple-duty caregiving men: An examination of subjective stress and perceived schedule control. JAG. doi:10.1177/0733464816641391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePasquale N. Mogle J. Zarit S.H. Okechukwu C.A. Kossek E.E., & Almeida D.M (in press). The family time squeeze: Perceived family time adequacy buffers work strain in certified nursing assistants with multiple caregiving roles. The Gerontologist. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorant E., & Boumans N.P (2016). Positive and negative consequences of balancing paid work and informal family care: A survey in two different sectors. International Journal of Health and Psychology Research, 4(1), 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury L. Higgins C., & Smart R (2011). Elder care and the impact of caregiver strain on the health of employed caregivers. Work (Reading, Mass.), 40(1), 29–40. doi:10.3233/WOR-2011-1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J.R., & Rothbard N.P (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management Review, 25, 178–199. doi:10.5465/AMR.2000.2791609 [Google Scholar]

- Ford M. T. Heinen B. A., & Langkamer K. L (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 57–80. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goergen T. (2001). Stress, conflict, elder abuse and neglect in German nursing homes: A pilot study among professional caregivers. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 13, 1–26. doi:10.1300/j084v13n01_01 [Google Scholar]

- Goode W.J. (1960). A theory of role strain. ASR, 25, 483–496. doi:10.2307/2092933 [Google Scholar]

- Hanson G. C. Hammer L. B., & Colton C. L (2006). Development and validation of a multidimensional scale of perceived work-family positive spillover. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(3), 249–265. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.11.3.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammersmith A.M., & Lin I.F (2016). Evaluative and experienced well-being of caregivers of parents and caregivers of children. JG:SS. Advance online publication. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes L. J. O’Brien-Pallas L. Duffield C. Shamian J. Buchan J. Hughes F., … North N (2012). Nurse turnover: A literature review—an update. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(7), 887–905. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T. Loscalzo M. Ramani R. Forman S. Popplewell L. Clark K., … Hurria A (2014). Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer, 120(18), 2927–2935. doi:10.1002/cncr.28765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns G. (2010). Presenteeism in the workplace: A review and research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(4), 519–542. doi:10.1002/job.630 [Google Scholar]

- Letvak S., & Ruhm C. J (2010). The impact of worker health on long term care: Implications for nursing managers. Geriatric nursing (New York, N.Y.), 31(3), 165–169. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks S.R. (1977). Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes on human energy, time and commitment. American Sociological Review, 42, 921–36. doi:10.2307/2094577 [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., & Jackson S (1986). Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual (2nd ed) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister S. Thornock C.M. Hammond J.R. Holmes E.K., & Hill E.J (2012). The influence of couple emotional intimacy on job perceptions and work–family conflict. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 40, 330–347. doi:10.1111/j.1552-3934.2012.02115.x [Google Scholar]

- Moen P. Kelly E. L. Tranby E., & Huang Q (2011). Changing work, changing health: can real work-time flexibility promote health behaviors and well-being?Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(4), 404–429. doi:10.1177/0022146511418979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasir R., & Sakdiah A (2010). Job satisfaction, job performance and marital satisfaction among dual-worker Malay couples. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences: Annual Review, 5, 299–305. doi:10.18848/1833-1882/cgp/v05i03/51637 [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S.J., & May D.C (2003). Spillover between marital quality and job satisfaction: Long‐term patterns and gender differences. JMF, 65, 482–495. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00482.x [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J. Stiehl E. M. Mittal V., & Leana C. R (2011). Stayers, leavers, and switchers among certified nursing assistants in nursing homes: A longitudinal investigation of turnover intent, staff retention, and turnover. The Gerontologist, 51(5), 597–609. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. M. Rideout E., & Carson M (1994). Nurses’ work: Balancing personal and professional caregiving careers. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 26(4), 43–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovine M.J. von Eye A., & Wood P (1988). The effect of low covariate criterion correlations on the analysis-of-covariance. In E. Wegmen (Ed.), Computer science and statistics: Proceedings of the 20th symposium of the interface (pp. 500–504). Alexandria, VA: American Statistical. [Google Scholar]

- Rutman D. (1996). Caregiving as women’s work: Women’s experiences of powerfulness and powerlessness as caregivers. Qualitative Health Research, 6, 90–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez S. Mahmoudi R. Moronne I. Camonin D., & Novella J.L (2015). Burnout in the field of geriatric medicine: Review of the literature. European Geriatric Medicine, 6(2), 175–183. doi:10.1016/j.eurger.2014.04.014 [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg J.G. Yorgason J.B. Miller R.B., & Hill E.J (2012). Family‐to‐work spillover in Singapore: Marital distress, physical and mental health, and work satisfaction. Family Relations, 61, 1–15. doi:10.111/j.1741-3729.2011.00682.x [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg J.G. Harper J.M. Hill J. Miller R.B. Yorgason J.B., & Day R.D (2013). “What happens at home does not necessarily stay at home”: The relationship of observed negative couple interaction with physical health, mental health, and work satisfaction. JMF, 75, 808–821. doi:10.1111/jomf.12039 [Google Scholar]

- Schuster T. L. Kessler R. C., & Aseltine R. H. Jr (1990). Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(3), 423–438. doi:10.1007/bf00938116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L. D. Hwang W. T., & Rogers A. E (2006). The impact of multiple care giving roles on fatigue, stress, and work performance among hospital staff nurses. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 36(2), 86–95. doi:10.1097/00005110-200602000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber S.D. (1974). Toward a theory of role accumulation. American Sociological Review, 39, 556–78. doi:10.2307/2094422. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart N. J. D’Arcy C. Kosteniuk J. Andrews M. E. Morgan D. Forbes D., … Pitblado J. R (2011). Moving on? Predictors of intent to leave among rural and remote RNs in Canada. The Journal of Rural Health, 27(1), 103–113. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R. (2012). The long-term care workforce: From accidental to valued profession. In D. Wolf and N. Folbre (Eds.), Universal coverage of long-term care in the United States: Can we get there from here? United States: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Tanaka K. Iso N. Sagari A. Tokunaga A. Iwanaga R. Honda S., … & Tanaka G (2015). Burnout of long-term care facility employees: Relationship with employees’ expressed emotion toward patients. International Journal of Gerontology, 9(3), 161–165. doi:10.1016/j.ijge.2015.04.001 [Google Scholar]

- ten Brummelhuis L. L., & Bakker A. B (2012). A resource perspective on the work-home interface: The work-home resources model. The American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556. doi:10.1037/a0027974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Griffin C. Brown J. B. St-Amant O. Sutherland N. Martin-Matthews A. Keefe J., & Kerr M (2015). Nurses negotiating professional-familial care boundaries: Striving for balance within double duty caregiving. Journal of Family Nursing, 21(1), 57–85. doi:10.1177/1074840714562645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Griffin C. Brown J. B. Vandervoort A. McNair S., & Dashnay I (2005). Double-duty caregiving: Women in the health professions. Canadian Journal on Aging, 24, 379–394. doi:10.1353/cja.2006.0015 [Google Scholar]

- Westermann C. Kozak A. Harling M., & Nienhaus A (2014). Burnout intervention studies for inpatient elderly care nursing staff: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(1), 63–71. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera E. Chang A., & Chen H. L (2010). Presenteeism: a public health hazard. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(11), 1244–1247. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1422-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemers E. E., & Bianchi S. M (2015). Competing demands from aging parents and adult children in two cohorts of American women. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 127–146. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00029.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth C. M. Auerbach H. P., & Parker V. A (2015). Advantages and challenges: The experience of geriatrics gealth care providers as family caregivers. The Gerontologist, 55(4), 595–604. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]