Abstract

Purpose of the Study

Elder mistreatment is an epidemic with significant consequences to victims. Little is known, however, about another affected group: nonabusing family members, friends, and neighbors in the lives of the older victim or “concerned persons.” This study aimed to identify (a) the prevalence of adults aged 18 and older who have encountered an elder mistreatment situation, (b) the proportion of these who helped the elder victim, and (c) the subjective levels of distress experienced by respondents who helped the victim versus those who did not.

Design and Methods

Data were collected from a nationally representative telephone survey of 1,000 adults (18+). Multiple linear regression was used to test the relationship between “helping status” and personal distress attributed to an elder mistreatment, defined as someone aged 60 and older experiencing violence, psychological abuse, financial exploitation, or neglect by a caregiver.

Results

Nearly 30% of adults knew a relative, friend, or neighbor who experienced elder mistreatment. Of these, 67% reported personal distress resulting from the mistreatment at a level of 8 or more out of 10. Assuming a helping role was associated with significantly higher levels of personal distress. Greater distress was also associated with being a woman, increasing age, and lower household income.

Implications

Knowing about an elder mistreatment situation is highly distressing for millions of adults in the United States, particularly for those assuming a helping role. We suggest intervention approaches and future research to better understand the role and needs of concerned persons.

Keywords: Elder mistreatment, Concerned persons, Families, Secondary victims

Each year, an estimated 10% of older adults in the United States experience elder abuse, neglect, or financial exploitation (Pillemer, Burnes, Riffin, & Lachs, 2016), also known as elder mistreatment. The abusers are frequently family members and acquaintances of the victim (Acierno, Hernandez-Tejada, Muzzy, & Steve, 2008). Although research indicates that only 1 in 24 victims of elder mistreatment are known to any service system (Lifespan of Greater Rochester Inc., Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City Department for the Aging, 2011), often family, friends, and neighbors intervene on behalf of the older person or consider doing so. In this article, we refer to these individuals as “concerned persons.”

Although not all concerned persons aware of elder mistreatment report it, those who do comprise 25% of all formal reports to Adult Protective Services (Teaster, Dugar, Mendiondo, Abner, & Cecil, 2006). Once a report is made, concerned persons may be asked by professionals to gather financial documents, petition for guardianship, offer housing to the victims, assist financially and more. These are significant interventions requiring financial and privacy sacrifices and are fraught with safety risks (NYC Elder Abuse Center [NYCEAC], 2014).

Concerned persons can experience a wide range of emotional and practical problems by knowing about and becoming involved in elder mistreatment situations (Breckman & Adelman, 1988). The focus of these concerned persons is, understandably, on the needs of the victim. However, as in other forms of caregiving, they can disregard their own needs not realizing that their health is at risk. For example, they might jeopardize familial relationships or jobs; suffer significant, ongoing distress or depression; have difficulty sleeping or eating; and experience health decline (NYCEAC, 2014).

There is scant research on concerned persons in the elder mistreatment literature. A recent study (Burnes, Rizzo, Gorroochurn, Pollack, & Lachs, 2016) demonstrated that when family members (i.e., one category of concerned person) played a role in referring an older victim for services, the victim had a higher level of service utilization than when the referral came from a third party (e.g., a community service source). These findings suggest the uniquely important role of concerned persons in resolving abuse.

Theory and research from related fields also yield insights. Early studies from the sexual assault literature indicate that persons in a sexual assault victim’s informal support network experience emotional distress, such as rage from knowing about the victimization (Davis, Taylor, & Bench, 1995) and guilt/self-blame for not protecting the victim (Cwik, 1996). Domestic violence research indicates that, by buffering the effects of the abuse by providing help, informal support in the lives of domestic violence victims can reduce the deleterious impacts of the abuse on victims (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014). Such findings from domestic violence contexts highlight the importance of exploring this under-recognized population in the elder mistreatment field.

The Bystander Intervention Model provides a framework for understanding the process concerned persons utilize to decide to intervene or not (Gilhooly et al., 2016). But the ability of victims’ friends to be supportive may be impeded by their own debilitating emotions (Ahrens & Campbell, 2000). The Caregiver Stress Process Model (Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990) may provide a useful framework to understand why some concerned persons assisting elder mistreatment victims experience higher levels of distress than others.

To begin to understand more about concerned persons, we conducted a survey to investigate: (a) the prevalence of adults (age 18+) who have a family member, friend, or neighbor who experienced elder mistreatment; (b) the proportion of these individuals who helped the elder victim; and (c) the subjective levels of distress experienced by respondents who helped the victim versus those who did not. We hypothesized that people assuming a helping role in the life of an elder mistreatment victim would experience higher levels of personal distress compared to those who did not help.

Methods

Study Design

We included four items on the issue of concerned persons in the lives of elder mistreatment victims in the Cornell National Social Survey (CNSS), a nationally representative, omnibus survey conducted in 2015 by the Survey Research Institute (SRI) at Cornell University. The CNSS telephone sample consists of randomly selected households generated by random digit dial sampling of all telephone exchanges within the continental United States and includes listed/unlisted households and cell phones. Individual respondents are selected in two steps: first, a household is randomly selected and then a household member who is at least 18 years old is randomly selected based on the “most recent birthday” selection method. (Further details on the sampling methodology, sample description, and response rates are available on-line (SRI, 2015). Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Total Sample and Among Individuals Knowing a Victim of Elder Mistreatment

| Characteristics | Total sample (n = 1,000) | Known a family/friend/neighbor victim of elder mistreatment (n = 294) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Provided help to victim | ||

| No | — | 117 (39.8) |

| Yes | — | 176 (59.9) |

| Relationship to victim | ||

| Nonfamily | — | 104 (35.4) |

| Family | — | 190 (64.6) |

| Age mean (±SD) | 48.9 (18.0) | 46.2 (16.6) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 501 (50.1) | 138 (46.9) |

| Female | 499 (49.9) | 156 (53.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 108 (10.8) | 34 (11.6) |

| Caucasian | 821 (82.1) | 239 (81.3) |

| African-American | 130 (13.0) | 41 (13.9) |

| Asian | 49 (4.9) | 17 (5.8) |

| Native American | 52 (5.2) | 26 (8.8) |

| Other | 21 (2.1) | 5 (1.7) |

| Household income | ||

| <30K | 131 (13.1) | 42 (14.3) |

| ≥30K | 850 (85.0) | 248 (84.4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 544 (54.4) | 150 (51.0) |

| Divorced or separated | 121 (12.1) | 41 (13.9) |

| Widowed | 61 (6.1) | 13 (4.4) |

| Single | 273 (27.3) | 90 (30.6) |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 473 (47.3) | 139 (47.3) |

| Part-time | 168 (16.8) | 49 (16.7) |

| Not working | 359 (35.9) | 106 (36.1) |

| Education status | ||

| Less than college | 540 (54.0) | 153 (52.0) |

| College of more | 459 (45.9) | 141 (48.0) |

| Personal distress mean (±SD) | — | 8.0 (2.4) |

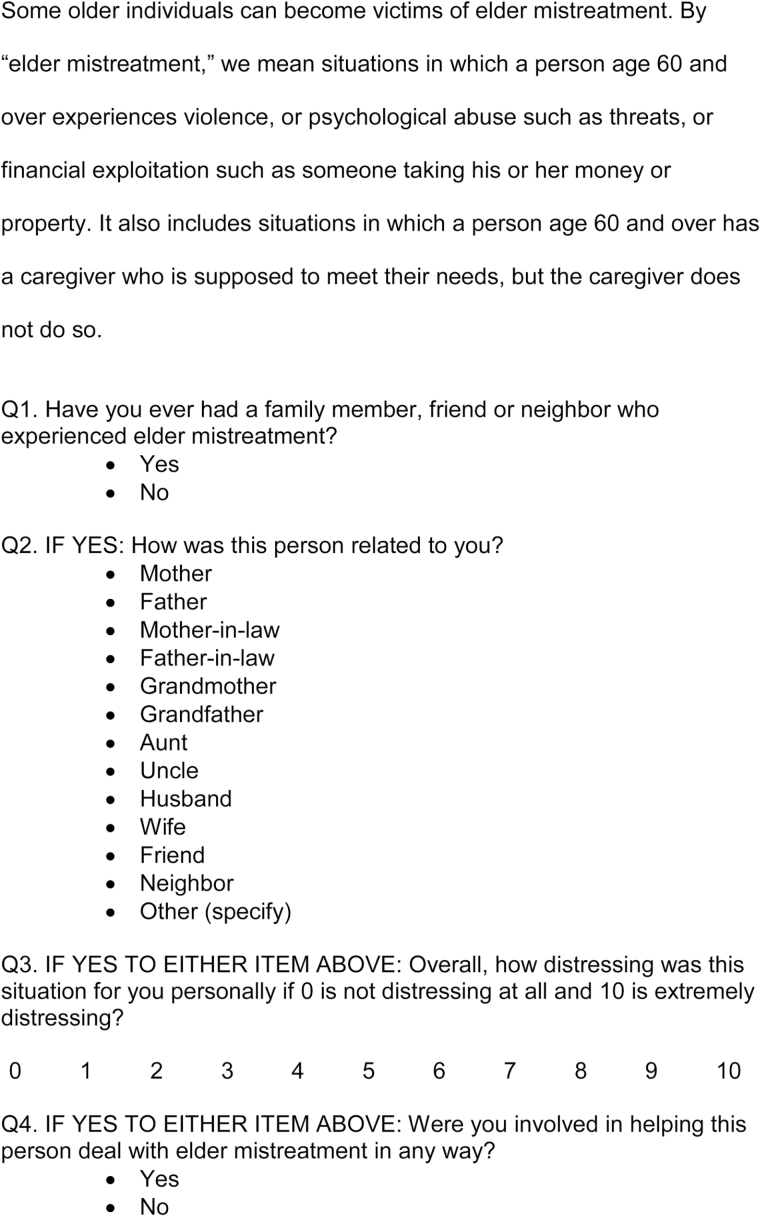

Measures

The respondents were provided with a definition of elder mistreatment, presented in Figure 1. We chose a precise age cutoff that both conforms to culturally defined norms of “older person” while also acknowledging that health disparities requires the young-old in many minority groups to need caregivers. We used broad terms commonly utilized in the elder justice field to describe the types of abuse and neglect. We did not include “self-neglect” as that phenomenon is conceptually different from one in which another person harms or endangers an older adult. We did not limit our definition to “relationship of trust” so as not to exclude those concerned persons whose helping role may not have been based on a trust relationship. We did not limit the definition to a particular setting, that is, community, nursing home, as the information we were seeking about concerned persons did not pertain to setting.

Figure 1.

Elder mistreatment definition and survey questions utilized.

The respondents were then asked four questions, presented in Figure 1.

Dependent Variable

Level of personal distress attributed to an elder mistreatment situation was measured using a self-report scale from 0 (not at all distressing) to 10 (extremely distressing) (see Figure 1 for item wording). We selected this broad measure of distress because of the limited number of items that could be included in an omnibus survey. Our goal was to allow respondents to create a subjective rating of perceived distress in response to the situation.

Independent Variables

Helping status was measured as a dichotomous (yes/no) variable. Type of relationship between concerned person and elder mistreatment victim was measured dichotomously as family (mother, father, mother-in-law, father-in-law, grandmother, grandfather, aunt, uncle, husband, wife, other family) or nonfamily (friend, neighbor, acquaintance, coworker, other). Sociodemographic control variables included age (continuous), gender (male/female), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Caucasian, African-American, Asian, Native American, Other), household income (≥ and <$30,000), marital status (married, divorced/separated, widowed, single), employment status (full-time, part-time, unemployed), and education status (college/less than college).

Analytic Plan

Prevalence rates were calculated (using the entire sample) as sample proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In the second analysis, only those individuals who reported knowing a family/friend/neighbor victim of elder mistreatment were included. Of the 294 individuals in this category, 8 cases were excluded from analysis due to missing data, leading to an analytic sample for this analysis of 286. Multiple linear regression was used to test the relationship between helping status and personal distress attributed to elder mistreatment, while controlling for helper–victim relationship type and sociodemographic variables.

Results

Prevalence

As shown in Table 1, using the entire sample for analysis, the proportion of adults who had known a victim of elder mistreatment was 29.4% (95% CI: 26.6%–32.2%; n = 294). The level of personal distress associated with knowing about an elder mistreatment situation was generally very high (mean score = 8.0), with two-thirds (67.0%) of respondents reporting a score of 8 or more. Among those who knew someone experiencing elder mistreatment, the proportion that became involved as a helper was 59.9% (95% CI: 54.3%–65.5%) (n = 176).

Predictors of Distress

Table 2 provides results of the multiple linear regression model examining the relationship between helping status and personal distress. In this analysis, only the 286 cases in which a respondent reported knowing a family/friend/neighbor victim of elder mistreatment were used. Overall model fit was significant, F (17, 268) = 4.56 (p < .001), and explained 24% of variation in the personal distress outcome (adjusted R2 = 0.24). Helping status was positively associated with level of personal distress; helpers experienced significantly higher levels of distress (β = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.16–2.35) than non-helpers. Among control variables, women who had knowledge of an elder mistreatment situation experienced significantly more distress than men (β = 0.53, 95% CI: −0.01 to 1.07). Increasing age was significantly associated with higher levels of distress (β = 0.04, 95% CI: 0.02–0.06). Finally, adults with household income greater or equal to $30,000 experienced significantly less personal distress (β = −0.83, 95% CI: −1.48 to −0.17) than those with income less than $30,000.

Table 2.

Multiple Linear Regression Model Predicting Level of Personal Distress Among Individuals Knowing a Victim of Elder Mistreatment

| Characteristic | β | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provided help to victim | 1.76*** | 0.30 | 1.16 to 2.35 |

| Family relation to victim | 0.23 | 0.26 | −0.30 to 0.75 |

| Age | 0.04*** | 0.01 | 0.02 to 0.06 |

| Female | 0.53* | 0.27 | −0.01 to 1.07 |

| Hispanic | −0.09 | 0.40 | −0.87 to 0.70 |

| Caucasian | 0.83 | 0.68 | −0.52 to 2.17 |

| African-American | 0.49 | 0.72 | −0.92 to 1.90 |

| Asian | 0.79 | 0.70 | −0.59 to 2.17 |

| Native American | −0.14 | 0.51 | −1.14 to 0.86 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 1.06 | 0.82 | −0.56 to 2.67 |

| Household income ≥30K | −0.83* | 0.33 | −1.48 to −0.17 |

| Marital status (ref. married) | |||

| Divorced/separated | −0.04 | 0.44 | −0.92 to 0.84 |

| Widowed | −0.41 | 0.47 | −1.35 to 0.52 |

| Single | 0.26 | 0.35 | −0.44 to 0.96 |

| Employment (ref. full-time) | |||

| Part-time | 0.02 | 0.41 | −0.78 to 0.82 |

| Not working | 0.29 | 0.31 | −0.33 to 0.90 |

| College degree or more | −0.25 | 0.28 | −0.80 to 0.30 |

Note: N = 294 – 8 = 286. β = coefficient; CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error (heteroscedasticity consistent).

*p ≤ .05. ***p < .001.

Discussion

Extended to the general population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016), these findings suggest that approximately 73 million adult Americans have had personal knowledge of a victim of elder mistreatment and approximately 44 million adult Americans have become involved in helping a victim deal with their mistreatment situation. Simply knowing about an elder mistreatment situation is generally highly stressful for over 32 million adult Americans, and providing help to the victim in dealing with their mistreatment exacerbates levels of personal distress.

There are several limitations to the research design. First, this survey provides information on lifetime and not annual prevalence. In addition, the omnibus survey imposed item restrictions to four questions about concerned persons, forcing a choice between focusing on prevalence versus understanding other important issues. A more extensive study could expand the number of critical questions asked, for example, exploring the differential impact by type of mistreatment and the relationship of the abuser to the concerned person.

Future studies could also explore the types of emotional and practical assistance provided by concerned persons, examine the types of distress experienced by them, and investigate the consequences of distress. For example, do family members who are distressed disengage from older adults, in turn leading to worse outcomes for older victims? It would also be useful to uncover what types of elder mistreatment interventions concerned persons try, what specific services they utilize, and how they perceive service gaps. Future research should also focus on whether or not the presence of a concerned person mediates formal service involvement and better outcomes for victims of elder mistreatment. In addition, this preliminary study informed the need for further research on the topic of concerned persons that employs rigorous design specifications, including validated outcome measures (e.g., personal distress). Conceptual development is required to understand what elements other than personal distress and helping status define a “concerned person.” In turn, assessment tools can be developed to identify concerned persons with greater accuracy.

Despite the need for further research, the survey findings suggest implications for practice and policy. Although many professionals encounter concerned persons when providing elder mistreatment services, they typically do not provide assistance tailored specifically to the needs of these individuals. Support services are essential if we are to address the needs of concerned persons in cases of elder mistreatment. Such services could include education about elder mistreatment and how to be effectively involved without harming oneself or the victim; emotional support for personal distress; and referral sources for themselves as well as the elder mistreatment victim. Such services could reduce both the levels of distress and the likelihood that concerned persons will disengage from assisting elder mistreatment victims, which would further isolate and imperil them. Thus, professional efforts to assist concerned persons could, in turn, help prevent further elder mistreatment.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (K24AG022399 to M. S. Lachs) and a National Institute on Aging Roybal Center grant (P30AG22845-01 to K. Pillemer).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Cornell Survey Research Institute for the data collection and we thank Kasey Brown for editorial assistance.

References

- Acierno R. Hernandez-Tejada M. Muzzy W., & Steve K (2008). National elder mistreatment study. Retrieved July 28, 2016, from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/226456.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens C. E., & Campbell R (2000). Assisting rape victims as they recover from rape: The impact on friends. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 959–986. doi:10.1177/088626000015009004 [Google Scholar]

- Breckman R., & Adelman R (1988). Strategies for helping victims of elder mistreatment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Burnes D. Rizzo V. M. Gorroochurn P. Pollack M. H., & Lachs M. S (2016). Understanding service utilization in cases of elder abuse to inform best practices. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35, 1036–1057. doi:10.1177/0733464814563609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwik M. S. (1996). The many effects of rape: The victim, her family, and suggestions for family therapy. Family Therapy, 23, 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Davis R. Taylor B., & Bench S (1995). Impact of sexual and nonsexual assault on secondary victims. Violence and Victims, 10, 73–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhooly M. M. Dalley G. Gilhooly K. J. Sullivan M. P. Harries P. Levi M., … Davies M. S (2016). Financial elder abuse through the lens of the bystander intervention model. Public Policy & Aging Report, 26, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lifespan of Greater Rochester Inc., Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City Department for the Aging (2011). Under the radar: New York State elder abuse prevalence study. Rochester, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- NYC Elder Abuse Center (NYCEAC) (2014, June). I’ll stand by you: Recognizing concerned family, friends and neighbors in the lives of elder abuse victims. NYCEAC eNewsletter. Retrieved July 28, 2016, from http://nyceac.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Ill_Stand_by_-You.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I. Mullan J. T. Semple S. J., & Skaff M. M (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30, 583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K. Burnes D. Riffin C., & Lachs M. S (2016). Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. The Gerontologist, 56(Suppl. 2), S194–S205. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Survey Research Institute (SRI) (2015). Cornell National Social Survey. Retrieved August 2, 2016, from https://www.sri.cornell.edu/sri/files/cnss/2015/Report 1 2015-Intro_Method.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sylaska K. M., & Edwards K. M (2014). Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 15, 3–21. doi:10.1177/1524838013496335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaster P. B. Dugar T. A. Mendiondo M. S. Abner E. L., & Cecil K. A (2006). Understanding elder abuse: The 2004 survey of state Adult Protective Services: Abuse of adults 60 years of age and older. Washington, DC: The National Center on Elder Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2016). Annual estimates of the resident population for selected age groups by sex for the United States, states, counties and Puerto Rico Commonwealth and municipios. Retrieved July 28, 2016, from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=PEP_2015_PEPAGESEX&prodType=table [Google Scholar]