Abstract

Fluoride/proton antiporters of the CLCF family combat F− toxicity in bacteria by exporting this halide from the cytoplasm. These transporters belong to the widespread CLC superfamily but display transport properties different from those of the well-studied Cl−/H+ antiporters. Here we report a structural and functional investigation of these F−-transport proteins. Crystal structures of a CLCF homologue are captured in two conformations, with simultaneous accessibility of F− and H+ ions via separate pathways on opposite sides of the membrane. Manipulation of a key glutamate residue critical for H+ and F− transport reverses anion selectivity of transport; replacement of the glutamate with glutamine or alanine completely inhibits F− and H+ transport while allowing rapid uncoupled flux of Cl−. The structural and functional results lead to a ‘windmill’ model of CLC antiport wherein F− and H+ simultaneously move through separate ion-specific pathways that switch sidedness during the transport cycle.

Many species of bacteria resist the toxicity of environmental fluoride by expelling this xenobiotic halide from the cytoplasm via proton-coupled F− antiporters1,2. These exclusively bacterial “CLCF ” transporters appear in a distinct clade of the ubiquitous CLC superfamily of anion transport proteins, and they display two striking features not seen in the long-studied Cl−-transporting CLCs. First, CLCFs uniquely lack the conserved Cl−-coordinating serine residue that governs selectivity among anions3,4. Instead, a methionine residue in the equivalent region, strictly conserved within a CLCF subclade, contributes to F− specificity by an unknown mechanism5. Second, the CLCFs are more strongly proton-driven than conventional CLCs, with 1:1 anion/proton stoichiometry2 rather than the 2:1 value observed in all Cl−-transporting homologues examined6. This report supplements the currently sparse landscape of CLCF antiporters by probing a homologue with functionally revealing mutations and solving crystal structures of the transporter and two mutants. The new structures, globally similar to conventional CLCs, differ from them in showing two previously unseen conformations: inward-open to F−//outward-open to H+, and inward-open to H+//outward-occluded to F−. They also capture two rotamers of the H+-coupling ‘gating glutamate,’ where point-mutations unexpectedly invert the transporter’s normal F− over Cl− selectivity. The results taken together suggest a novel rotary mechanism of F−/H+ antiport.

RESULTS

The CLCF homologue “Eca” from Enterococcus casseliflavis provides a biochemically tractable exemplar of these F−-handling antiporters5. Eca differs from conventional Cl−-transporting CLCs in its 1:1 anion-to-proton stoichiometry and its strong selectivity for F− over Cl−2,5. These features raise basic questions. Does the critical “gating glutamate” (E118 in Eca), an essential, extracellularly positioned H+-transfer residue in Cl−/H+ antiporters6–9, also serve this purpose in the CLCFs? How is proton coupling achieved in CLCFs, which uniformly lack the intracellular-facing glutamate also required for H+ transfer in many Cl−/H+ antiporters10,11? Does the conserved methionine residue (M79 in Eca) contribute to F− selectivity by replacing the critical serine that along with a conserved tyrosine coordinates Cl− at an ‘internal gate’ of previously examined CLCs? Indeed, does this phylogenetically remote clade even use a F−-coordinating tyrosine, which cannot be identified in the poor sequence alignments in this region? In other words, are the functional and sequence oddities of the F− transporters manifested in the structures of these proteins in a coherently readable way?

The gating glutamate in CLCF crystal structures

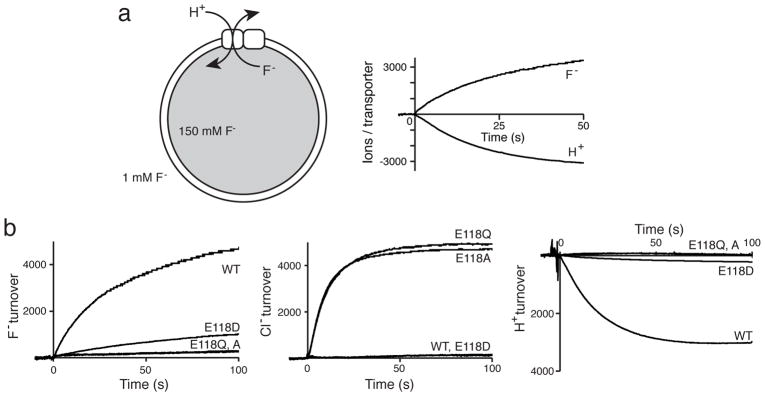

We first examine the role of the gating glutamate (Glug) in proton coupling by asking, as with conventional CLCs12,13, how point substitutions at this position affect F−: H+ transport-stoichiometry. Ion fluxes are quantified in Eca-reconstituted liposomes pre-loaded with high F− and suspended in low F− (Fig 1a). Equimolar F− efflux and H+ influx in wildtype (WT) Eca confirms its 1:1 stoichiometry, and similar experiments with Glug mutant E118D (Fig 1b) establish a 10-fold lower transport rate and weaker coupling, with ~2:1 stoichiometry. However, non-dissociable mutants E118A,Q produce a completely unexpected, even alarming, result: inversion of ion selectivity. Neither mutant transports F−, and instead both pass Cl− at over twice the WT rate for F−, without concomitant H+ movement (all rates reported in Table 1). Since this result has no analogous precedent among Cl− CLCs, it raises suspicions that previous CLC crystal structures may be inadequate templates for interpreting functional behaviors of the phylogenetically distant CLCF proteins.

Figure 1. Ion transport for Eca and ion-coupling mutants.

a. Cartoon depicting liposomal F−/H+ antiport assay (left), and a recording illustrating WT ion fluxes (right). b. F−, Cl−, and H+ fluxes for Glug mutants. H+ flux was measured under F− conditions for WT and E118D and Cl− conditions for E118Q/A. Upward/downward signals indicate appearance/disappearance of indicated ions from proteoliposome suspension. Turnover is reported as ions/Eca subunit.

Table 1.

Unitary ion turnover rates in Eca and indicated mutants

| Construct | F− efflux | Cl− efflux | H+ influx |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 150 ± 10 | 0 ± 1 | 125 ± 10 |

| E118D | 16 ± 2 | −2 ± 3 | 8 ± 1 |

| E118Q | 0 ± 1 | 350 ± 30 | <4 |

| E118A | 2 ± 2 | 370 ± 30 | <4 |

| E318Q | 8 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 |

| E318A | 23 ± 4 | 2 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 |

| T320A | 13 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 |

| Y396A | 35 ± 6 | 1 ± 1 | 39 ± 4 |

| V319G | 50 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 23 ± 2 |

Initial rates of ion transport, determined by ion-specific electrodes in proteoliposome suspension, are tabulated as ions/sec/Eca subunit. Proton flux assays were performed under F− conditions except for E118Q/A, which were done under Cl− conditions, as described in Methods.

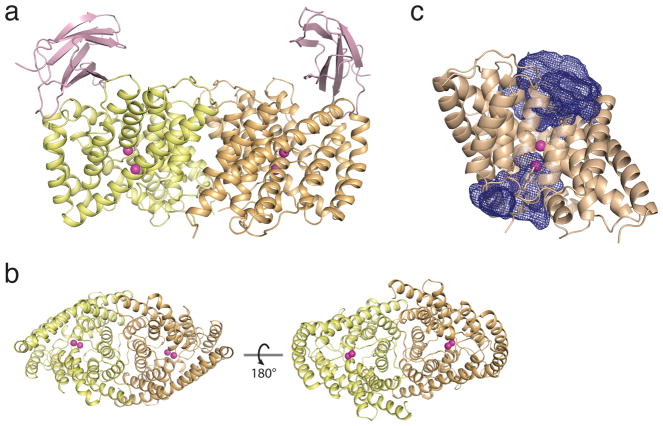

Accordingly, a crystal structure at 3.0 Å resolution of homodimeric Eca was solved in complex with a “monobody” crystallization chaperone14 that does not affect transport activity (Fig 2a, b, Supplementary Fig 1, Table 2). As expected from known CLC structures, each Eca subunit shows extracellular and intracellular aqueous vestibules impinging upon a polar but largely anhydrous ion-coupling region in the center of the protein 6–8 Å in length (Fig 2c). The protein’s fold mirrors other CLCs (Supplementary Fig 2a), but several of its 16 helices are shorter than their counterparts, and some are imprecisely aligned to them. The αA and αR helices of the Cl− CLCs are absent in Eca (we retain conventional CLC helix labels, starting with helix αB), and the equivalent residues of the C-terminal αR-helix trace a well-ordered but meandering extended backbone trajectory.

Figure 2. Structure of CLCF-Eca.

a. Asymmetric unit, showing a single Eca homodimer (yellow, wheat) with two monobody chaperones (pink) bound to extracellular surface and bound F− ions (magenta). The Eca model is complete except for 7 N-terminal and 3–4 C-terminal disordered residues. b. Extracellular (left) and intracellular views of Eca, with monobodies removed. c. A single Eca subunit, with aqueous vestibules shown in blue mesh.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| WT (PDB 6D0J) | E118Q (6D0K) | V319G (6D0N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 116.98, 126.42, 133.94 | 118.4, 126.0, 134.2 | 118.1, 124.8, 135.5 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 49.35-3.00 (3.12-3.00)* | 49.73-3.35 (3.55-3.35) | 49.67-3.12 (3.26-3.12)* |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.073 (3.52) | 0.042 (1.91) | 0.082 (2.81) |

| I/σI | 19.4 (1.3) | 14.5 (1.4) | 12.2 (1.3) |

| CC1/2(%) | 1.000 (0.825) | 1.000 (0.649) | 1.000 (0.699) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.8 (99.2) | 99.9 (99.6) |

| Redundancy | 34.5 (32.8) | 8.4 (8.5) | 17.6 (17.3) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 49.35-3.00 | 49.73-3.35 | 49.67-3.12 |

| No. reflections | 39989 | 29271 | 35889 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.240/0.260 | 0.244/0.266 | 0.248/0.270 |

| No. atoms | |||

| Protein | 7387 | 7387 | 7398 |

| F− | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Detergent/other | 204 | 204 | 204 |

| Water | 16 | 9 | 11 |

| B-factors | |||

| Protein | 152 | 193 | 170 |

| F− | 153 | 172 | 138 |

| Detergent/other | 186 | 227 | 204 |

| Water | 140 | 163 | 143 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.465 | 0.462 | 0.452 |

| Ramachandran favored/outliers (%) | 96.2/0.2 | 96.4/0.2 | 96.6/0.2 |

WT data was merged from measurements of three different positions on the same crystal. V319G dataset was merged from measurements of two different positions on the same crystal.

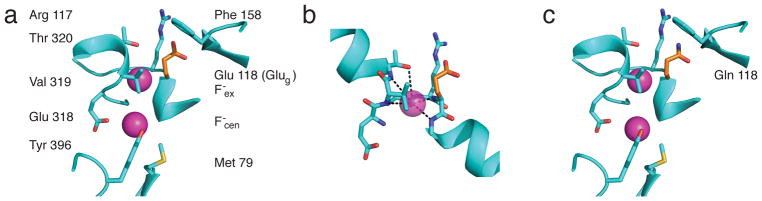

Two F− ions, F−ex and F−cen, appear in each Eca subunit located at the “external” and “central” sites in the canonical anion-binding region observed in all CLCs, roughly halfway across the membrane. These densities may be confidently assigned as F− ions rather than isoelectronic waters from their congruence with Cl−ex and Cl−cen in structural alignments (Supplementary Fig 2b), and since many of their coordinating residues match those known in the Cl− CLCs (Fig 3). For instance, both F−ex and Cl−ex are mainly embraced by backbone amides in equivalent stretches of sequence (G116-G119 in Eca, G146-G149 in CLC-ec1), as well as by the positive dipoles of the N-termini of helices αF and αN in both. Moreover, the tyrosine hydroxyls coordinating the central anions in the F− and Cl− transporters coincide precisely (Y396 in Eca, Y445 in CLC-ec1). Although the resolution here is too low to quantify F− occupancy values, precedent from other CLC structures7 and the clear difference densities of these light ions suggest simultaneous occupancy of both.

Figure 3. Ion-coupling region of Eca.

a. WT, showing F− ions (magenta spheres) and Glug (orange stick). b. Detail of WT F−ex coordination. c. Same region for E118Q.

In Cl−-transporting CLCs, the Glug sidechain has been variously observed in three rotameric positions proposed as intermediates in the transport cycle6,9,15: ‘Down’, wherein the deprotonated carboxylate group displaces Cl− from the central anion site, ‘Middle’, where also deprotonated it occupies the external site, and ‘Up’, extended such that the carboxyl group reaches for the extracellular solution, with Cl−ex and Cl−cen simultaneously occupying both sites. The Up-configuration has been seen only with the protonated surrogate glutamine substituted at this position, never with glutamate, whose carboxyl group, when deprotonated, seeks the electropositive anion-binding sites. But in WT Eca, Glug adopts the Up-rotamer (Fig 3a), allowing both F− ions to occupy the transport sites; its protonation state is unknown under these pH 6 crystallization conditions.

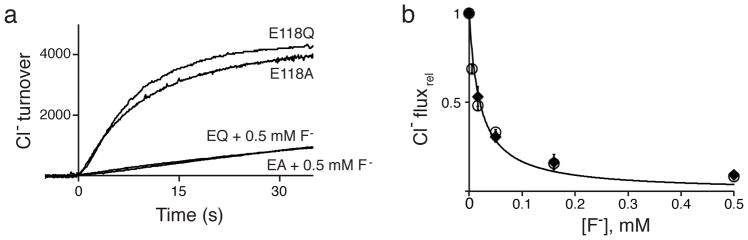

The profound reversal of ion selectivity in E118Q would seem to anticipate a corresponding structural alteration. However, a crystal structure of this mutant (Fig 3c, Supplementary Fig 1, Table 2) fails to show any significant differences with WT. The appearance of F− ions at the same sites as in WT motivated flux experiments (Fig 4) showing that Cl− transport in this mutant is strongly blocked by F− (Ki = 20 μM in the presence of 140 mM Cl−). This effect provides a proxy for F− binding, at least 10-fold stronger than in WT, as observed previously by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)5 and confirmed here (Supplementary Fig 3). While these blocking experiments demonstrate tight F− binding to the mutant’s transport machinery, they provide no information about where the ion binds - to the external site, the central site, or both. Unfortunately, we could not obtain ITC heat signals with E118Q or diffraction-quality crystals formed in F−-free Cl− solutions.

Figure 4. F− block of Cl− flux in Glug mutants.

a. Raw traces of Cl− flux in Glug mutants at indicated F− concentration added to both sides of the liposomes. Turnover defined as in Fig 1a. b. F− inhibition of Cl− efflux initial rate through E118A (filled points) or E118Q (open points), normalized to the rate at zero F−. Curve represents hyperbolic fit to both datasets, with Ki = 20 μM.

In conventional CLCs, the Up position of Glug - previously observed only with substituted Gln - is widely considered to represent an outward-open state of the transport cycle. In this view, binding sites for Cl−cen, Cl−ex, and H+ enjoy access to extracellular solvent, either unfettered or accompanied by subtle pH-dependent backbone movements7,16,17, while intracellular access is prevented by a “gate” formed by Cl−-coordinating sidechains of conserved Ser and Tyr at the central site15,18,19. This picture is completely inverted in the CLCF structure. Now for the first time Glug appears in the Up-configuration, its carboxyl in direct exchange with extracellular protons; remarkably, the anion-binding sites are accessible only to intracellular solvent, via a wide aqueous vestibule leading to F−cen bound at its apex and F−ex ~6 Å behind it (Fig 2c). Extracellular access to both ions is blocked off primarily by a stretch of extended sequence in conserved residues immediately preceding Glug (S114-R117), unlike the more open pathway in conventional CLCs. The Up-configuration of Glug positions it far away from the intracellular side of the protein. This antiporter conformation is simultaneously accessible to extracellular H+ (but not F−) and to intracellular F− (but not H+).

Coordination of F− ions

Since numerous F−-coordinating moieties in Eca match those in the Cl− CLCs, the new structures provide no immediate explanation for the unusual F− specificity of the CLCFs. The coordination of F−ex, mostly by backbone amides, is similar to the surround of Cl−ex in other CLCs, except for the sidechain of T320, whose hydroxyl group hovers ~4 Å away from F−ex (Fig 3). It is F−cen that is differently clothed. The strictly conserved Cl−cen-coordinating central serine residue in the conventional CLCs is missing in the CLCFs, and in a roughly equivalent position lies a conserved Met residue (Met79), suggested from sequence-gazing and confirmed by mutagenesis as a F− selectivity determinant2,5. It is particularly notable that its terminal methyl and γ-methylene groups, rendered weakly electropositive by proximity to the δ-sulfur, are positioned near F−cen, since this arrangement quite precisely reprises F− coordination in a functional Met mutant of a F−-specific ion channel20. In addition, the coordination of F−cen by the hydroxyl of Y396 establishes this residue as equivalent to the inner-gate tyrosine that coordinates Cl−cen in Cl− CLCs (Y445 in CLC-ec1). This same Tyr does double-duty by also orienting its aromatic ring to approach this same F− edge-on, an electropositive quadrupolar interaction previously observed in the only other known F− transport protein family, the Fluc ion channels21,22. An additional oddity of the F−cen coordination sphere is a close contact (3.3 Å) with the carboxyl group of E318, which has no counterpart in conventional CLCs. Beyond its involvement in F− coordination, it is conspicuous from its location at the top of the intracellular cavity, close to where the carboxylate of Glug would be in its Down position, suggestive of a critical H+-handoff function. We suppose that in this configuration E318 is a protonated H-bond donor to F−cen. The position of F−cen at the top of the intracellular vestibule implies that it is also partly hydrated by crystallographically invisible bulk waters.

Functional tests of structure-based suggestions

The CLCF structure thus identifies three previously unsuspected residues contributing to F− coordination: Y396, E318, and T320, the latter two without equivalents in the Cl− CLCs. Mutants at these positions were constructed to gauge their effects on F− transport rate, proton coupling, and anion specificity using liposome flux experiments. The mutants (Y396A, E318Q/A, T320A) express similarly to WT and show dimeric, homogeneous size-exclusion profiles. All give qualitatively similar results: 4–20-fold inhibition of F− transport rates, specificity for F− with no Cl− permeation, and retention of proton coupling with respectable stoichiometry between 1:1 and 2:1 (Table 1). The full preservation of proton coupling in Y396A is particularly surprising, since the equivalent mutant in a Cl−-transporting CLC is severely uncoupled18. These facts rule out a few obvious mechanistic suggestions irresistibly arising from the structure: that E318 might be a required way-station for H+ transit, that Y396 might determine F− selectivity and H+ coupling, and that H-bond donation to F− by T320 might be necessary for proper antiport behavior.

Having failed to eliminate F−/H+ coupling by the sidechain substitutions above, we wondered if a Hail-Mary maneuver - glycine substitutions of residues coordinating F−ex through backbone amides - might enhance conformational flexibility in this region and thereby place a thermodynamic penalty on F− binding. All such mutants severely impair function except for one, V319G, which only modestly inhibits transport rate (3-fold), weakens H+ coupling 2-fold, and preserves F− specificity (Table 1). In addition, ITC experiments show 5-fold decreased F− binding affinity of the mutant (KD = 1 mM) compared to WT (Supplementary Fig 3). This mutant apparently allows an ‘extra’ F− ion to sneak through the transport cycle unaccompanied by proton counter-transport, perhaps due to its weakened binding; however, we cannot distinguish such ‘slippage’ from a fundamental change in mechanism to a tight 2:1 F−/H+ coupling.

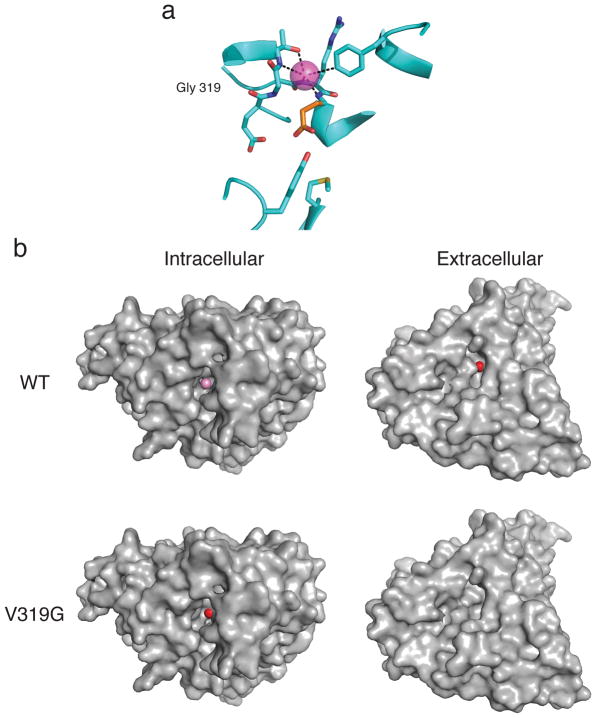

Structure of an occluded, ion-swapped configuration

The altered F− affinity of V319G combined with its overall maintenance of F−-specific antiport motivated us to crystallize this mutant. The resulting structure reveals an unexpected conformation (Fig 5a, Supplementary Fig 4, Table 2). Here, Glug adopts the Down position, replacing F−cen in the central anion-binding site and thereby blocking off the intracellular access to F−ex seen in WT, a configuration similar to that observed in a eukaryotic CLC antiporter15. The Down rotamer has not been previously observed in any bacterial CLC structures but has been proposed as an essential, universal intermediate in the CLC antiport cycle9. In this configuration, backbone atoms around the mutated residue remain unmoved from WT positions. F−ex, the sole F− ion in the structure, having moved ~1.5 Å toward the extracellular side, is now occluded. This small outward displacement changes the ion’s coordination; it loses the mutated residue’s backbone amide and gains a short (2.6-Å) H-bond from T320, as well as an edge-on aromatic quadrupole from F158, which moves in to fill the space vacated by Glug’s 7.5- Å excursion from its Up position (Fig 5a). Although the F− ion appears shallowly buried, Glug is not; its carboxyl group now directly faces the intracellular vestibule, where it is free to exchange solvent protons, a proton accessibility that is flipped compared to the WT structure (Fig 5b).

Figure 5. Ion accessibility of WT Eca and V319G mutant.

a. Ion-coupling region of V319G. F− (magenta) is observed in only one of the two Eca subunits at this resolution. Glug (orange stick) adopts the Down rotamer, its carboxylate occupying the central anion-binding site. b. Intracellular and extracellular surface representations of WT and V319G single subunits, viewed from indicated sides, showing solvent accessibility of bound F− (magenta) or Glug carboxyl oxygens (red).

DISCUSSION

These experiments have uncovered several unexpected characteristics of a F−/H+ antiporter, characteristics we surmise on the basis of a functional survey5 to be general within this clade of bacterial CLCs. First, removal of the Glug carboxyl group brings about a profound reversal of transport specificity, allowing uncoupled Cl− passage and abolishing F− transport. The F−-binding experiments argue that F− fails to permeate these mutants because it binds too strongly, so as to retard ion dissociation at an unknown step in the transport cycle. This inhibitory anion-binding effect recalls analogous observations in Cl− CLCs23,24. Enhanced binding affinity is likely due to the ion-coupling region’s inherently electropositive character, which is strengthened by the uncharged Glug substitutions. The reason why Cl− does not permeate WT Eca remains unexplained, although it is possible that its weak binding affinity5 prevents it from displacing the deprotonated Glug carboxylate from an anion-binding site, thus locking the cycle at some step. We note, however, that if sufficiently high voltage is applied to WT Eca, Cl− can be driven through the protein5; to avoid that complication, all flux experiments here were performed at zero voltage, where Cl− is negligibly permeant.

A second conclusion solves a longstanding puzzle: how can CLCFs, as well as some conventional CLCs15,25, dispense with the special internal glutamate (E203 in CLC-ec1) necessary in many Cl−/H+ antiporters for transferring intracellular protons to the ion-coupling region via transient water-wires10,11,26,27? The V319G structure provides the answer, at least for Eca. A wide intracellular aqueous vestibule leading to Glug’s carboxylate in the Down position allows proton exchange directly with solvent.

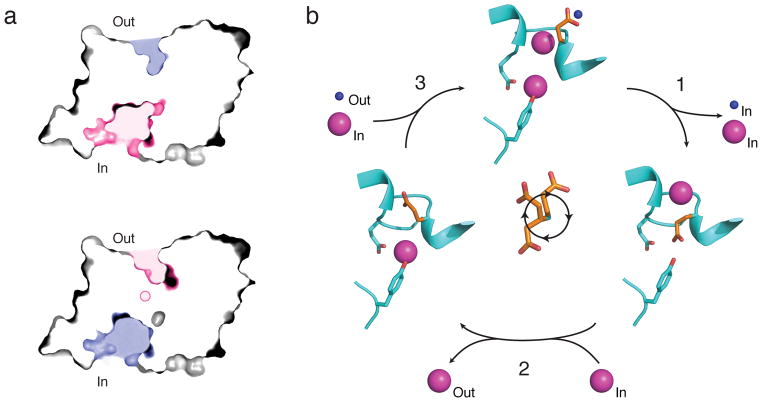

A third conclusion, both surprising and revealing, arises from comparisons of WT and V319G structures (Fig 5b). We view these as representing two novel conformations, mechanistically intriguing for an antiporter, in which F− and H+ are simultaneously accessible to their transport sites via separate pathways from opposite sides of the membrane. In WT, the Glug sidechain is captured in the Up-position, its carboxylate exposed to the extracellular aqueous vestibule, where it can readily exchange protons; this same conformation blocks bound F− ions from extracellular access while exposing them to intracellular solvent. The V319G structure inverts this accessibility, with Glug Down and H+ in easy intracellular exchange, while the F−ex ion is occluded in a more external location; its occlusion, however, appears fragile, such that the anion might gain access to extracellular solution through sidechain dynamics or the small backbone movements previously inferred for Cl− CLCs16,17. We therefore designate the mutant’s configuration “extracellular-occluded”. Because the Down-configuration of Glug in the functionally competent V319G mutant is identical to that observed in a eukaryotic Cl− CLC15, and since its existence in a prokaryotic Cl− CLC is supported by flux experiments9, we consider it to represent a relevant, on-pathway configuration rather than a mutagenic perversion.

These conclusions lead immediately to a picture of the antiporter switching between two conformations of opposite sidedness, each with separate pathways for the functionally entwined ions (Fig 6a). Each conformation presents pathways connecting the ions from the center of the protein to solvent on opposite sides of the membrane. The structures suggest that F− (but not H+) can enter the protein from the inside only when H+ (but not F−) can enter from the outside, and after the conformational switch, F− can leave to the outside only when H+ can leave to the inside. This picture fundamentally differs from the conventional ping-pong antiport mechanism (frequently misnamed “alternating access”) by which many transporters operate, wherein the coupled substrates bind in a mutually exclusive fashion. Here in contrast, the coupled ions occupy their transport sites simultaneously at certain steps in the cycle, as in other proposed CLC mechanisms.

Figure 6. F−/H+ antiport model.

a. Cross-sectional view of WT (upper) or V319G (lower) structure, with aqueous vestibules colored pink or blue to indicate F− or H+ accessibility, respectively. Occluded F− position in V319G is shown as pink circle. b. Proposed transport cycle depicting WT (top) and V319G (right) structures along with a hypothetical conformation (left) based upon CLC-ec1 transporter with Glug in Middle position. F− ions are magenta, H+ are blue, and Glug is orange. Cycle is shown for net F− export; clockwise trajectory of Glug sidechain, with rotamers in Up, Middle, and Down positions is shown in center of the diagram.

The CLCF structures, assuming them on-pathway, taken along with the functional results, are difficult to reconcile with the piston-like movements acting in the numerous variations of Cl− CLC mechanisms previously proposed9,15–17,28–30. In such models, the deprotonated Glug sidechain in its Up-position pushes both Cl− ions inward as it displaces them from their sites, and then, after protonation from intracellular solution, withdraws via the same pathway.

We propose instead a “windmill” model, in which alternate conformations with ion pathways swapping sidedness lead naturally to coupled antiport (Fig 6b). In accordance with all known CLC crystal structures, the model requires both transport sites to be always occupied by anions - either F− or deprotonated Glug. The transport cycle is depicted with ion gradients favoring net F− export, its physiological task. The cycle starts with a fully loaded protein, with both F− sites filled and Glug protonated (top image). The carboxyl-bearing sidechain, performing rotameric gymnastics (Supplementary Fig 5), rotates clockwise from its Up position around the F−ex ion without displacing it to occupy the central site in the Down position (Step 1). This movement delivers both F−cen and a proton to the intracellular solution. The cycle continues (Step 2) as the sidechain, now deprotonated, withdraws to the Middle position, chasing F−ex off its site to the extracellular side, while intracellular F− returns to refill the central site. We assume that this step opens the extracellular pathway enough to allow F−ex to be expelled outward by Glug. Although our Eca structures do not include this sidechain-anion configuration, we nevertheless consider it a plausible intermediate since it appears in nearly all known Cl− CLC structures. Finally (Step 3), deprotonated Glug returns to the Up position, continuing through the anion-friendly pathway that it had previously circumvented in its protonated state, while F−cen moves upward to the external site and an intracellular F− ion follows into the vacated central site. Net movement in the cycle is thus one proton inward and one F− outward, with the protonated sidechain’s ‘downward’ path distinct from its deprotonated ‘upward’ movement via the anion-binding sites: a clockwise rotary trajectory. Of course, all steps are reversible, so if electrochemical gradients would instead favor net inward movement of F−, Glug would rotate counterclockwise. This mechanism rationalizes the low transport rate of E118D, whose shorter sidechain impairs these rotameric contortions. It also explains inhibition of F− transport in the electrostatically neutered Glug mutants, as efficient ejection of tightly bound F−ex requires an anionic Glug; this latter point leads us to conjecture that Cl− may permeate these mutants simply as a result of its weaker binding and absence of competition from the Glug carboxylate.

The mechanism proposed here leaves many questions unanswered. What are the affinities of the two F−-binding sites in the conformations observed? Why does Cl− easily permeate the Glug mutants but not WT? At which step does high voltage act on WT to force Cl− through the transporter5? How does Met79 influence F− selectivity? Finally, we emphasize that in light of the unique 1:1 stoichiometry of the CLCFs, the windmill mechanism is proposed only for this antiporter clade. We remain agnostic as to whether it applies to the CLC superfamily in general; about that question, the experiments here are silent.

Methods

Reagents

All chemcals were purchased at the highest grade from Sigma-Aldrich or Thermo Fisher. n-decylmaltoside (DM), n-decylphosphocholine (fos-choline-10), and 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammo-nio]-1-propane sulfonate] (CHAPS) were obtained from Anatrace (Maumee, OH), and E. coli polar phospholipids (EPL) were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). K-isethionate solutions were prepared by titrating isethionic acid (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) with KOH.

Protein expression, purification, and functional reconstitution

The Eca CLCF construct used here from Enterococcus casseliflavus (GenBank EEV30821.1) contains three N-terminal alanines arising from the cloning site, but residues are numbered according to the WT sequence, ignoring this insertion. The “WT” background construct, on which all mutants were made, contains a M4I mutation to remove a possible alternative start codon. All Eca proteins carry an uncleaved C-terminal hexahistidine tag preceded by a GSGG linker. Eca was expressed from vector pASK90 with a tetracycline promoter31, and all mutations were made via standard PCR techniques.

Eca was expressed in BL21(DE3) cells. In brief, transformed cells were grown at 37 °C to ~0.8 OD in terrific broth and induced with 0.2 μg/mL anhydrotetracycline for 3 hr. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the pellets were resuspended in 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM tris pH 7.5 with DNAse and lysozyme. Cells were sonicated, and Eca was extracted with 4% DM for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were then centrifuged to pellet insoluble material and loaded on Talon cobalt resin (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) equilibrated with 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DM, 20 mM tris pH 7.5. Protein was washed and eluted sequentially with 40 mM and 400 mM imidazole in the above buffer. The protein was concentrated and purified over a Superdex 200 Increase size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with either 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DM, pH 7 (functional assays), or 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaF, 5 mM DM, pH 7 (crystallography). Eca for isothermal titration calorimetry was prepared as above, except that the Talon equilibration buffer was 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM Na/K tartrate, 2 mM NaCl, 5 mM DM, pH 7.5, and the Superdex-ITC buffer was 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM Na/K tartrate, 5 mM DM, pH 7.0.

Proteoliposomes were formed by mixing purified Eca with 10–20 mg/mL stocks of EPL solubilized with 30–40 mM CHAPS. Protein/lipid mixtures were extensively dialyzed using 10 kDa MWCO Slide-A-Lyzer cassettes (Thermo Fisher) against 150 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) pH 7.5 with either 150 mM KF or 150 mM KCl. Proteoliposomes were freeze-thawed 3x prior to use. For F− blocking experiments (Fig. 4) F− at the reported concentration was added to KCl-dialyzed proteoliposomes prior to the freeze-thaw cycles. Final protein/lipid ratios were 3–15 μg protein/mg lipid.

The monobody crystallization chaperone “X1” (Supplementary Fig 6) was selected from a phage display library as described14, and mutated slightly to improve crystal contacts. It was expressed from a pHFT2 vector in BL21(DE3) cells. Transformed cells were grown to OD 0.8 in terrific broth at 37 °C and induced 3 hr at 30°C with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were harvested and sonicated as above. Sonicated cells were clarified by centrifugation and loaded on Talon cobalt resin by batch binding for 3 h. The N-terminal hexahistidine tag was removed by on-column cleavage by overnight incubation with TEV protease (0.2 mg/L of cell culture). Cleaved monobody was rinsed off the column with equilibration buffer, concentrated, and purified over a Superdex 75 Increase column equilibrated with 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaF, pH 7.

Ion flux measurements

Liposomes loaded with either 150 mM KF or KCl were extruded through 0.4 μm membranes (Whatman) and 100 μL were centrifuged over a 1.5 mL Sephadex G-50 column equilibrated with flux-assay buffer (1 mM MOPS pH 7.5, 150 mM K-isethionate, 123 mM Na-isethionate). Liposomes were diluted into a stirred beaker containing flux buffer supplemented with either 1 mM KF or 1 mM KCl for F− or Cl− conditions5. For F− blocking experiments, KF at the reported concentration was present on both sides of the liposome membrane. Flux was initiated by the addition of 0.9 μM valinomycin. Appearance of ions in the liposome suspension was followed continuously with F−, Cl−, or H+-specific electrodes in a stirred cell. Reported initial flux rates were calculated 2–10 sec after adding valinomycin, and are corrected for the background leakage through protein-free liposomes.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed as previously described5, with both protein and F− in the above Superdex-ITC buffer. Measurements were made in a TA Instruments (New Castle, DE) Nano-ITC. Protein (170 μL) at ~30–250 μM was titrated with 2 μL injections of 5–30 mM KF at 25 °C, and data were fit to single-site isotherms.

Crystallography

Purified Eca and monobody X1 were concentrated and mixed to a final protein stock of 10 mg/mL Eca and 2.8 mg/mL monobody, supplemented with 11 mM fos-choline-10. Crystals were formed via the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method, with drop mixtures containing between 1 and 3 μL of protein and well solution mixed in equal volume. Well solutions consisted of 100 mM K-formate, 100 mM 2-[(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)-(carboxymethyl)amino]acetic acid (ADA) pH 6.0 or 6.2, and 20–24% PEG600. Crystals were incubated for ~5 weeks at 22 °C. Serial additions of cryoprotectant were required, consisting of 27%, 29%, and 34% PEG600 in solutions matching the final crystal solution. The initial drop volume of 27% PEG600 was first slowly added, followed by 2x the initial volume of 29% PEG600, and 4x the initial volume of 34% PEG600. Crystals were then picked with cryo loops and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Datasets were collected at the Advanced Light Source beamlines 5.0.1 and 5.0.2. Frames were integrated, scaled, and merged using Xia2/DIALS/Aimless32–34. Molecular replacement of WT Eca was done in PHASER35, using as search model CLC Cl−/H+ antiporter from Synechocystis sp. (PDB# 3Q17 chain B) trimmed with Chainsaw36 based upon a sequence alignment from AlignMe37. The two monobodies were then placed using chain E from PDB# 5FXB, manually trimmed to remove regions of differing sequence. Molecular replacement for the mutant structures was done using the refined WT structure. Structure were refined using phenix.refine38 and Refmac539, with final refinement done in Phenix. TLS and torsion-angle NCS restraints were used for all structures. V319G and E118Q refinement used reference model restraints against the final WT monobody chains, but not the Eca chains. Real-space refinement was done in COOT40. Extent of F− accessible vestibules was calculated in HOLLOW41.

Statistics and reproducibility

In plots and Table 1, rates report mean ± s.e.m. of 3–6 repeats and of at least two independent protein preps. ITC experiments (illustrated in Fig SI 3) were repeated three times.

Data availability

Crystallographic data are deposited in the Protein Data Bank: WT Eca (PDB 6D0J), E118Q (PDB 6D0K), V319G (PDB 6D0N). Source data for Figs 3d, 4b and 4c and Supplementary Fig 3 are available on request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Miller-lab members for advice and criticisms, and we acknowledge with ambiguous gratitude frequent and interminable discussions with Dr. Alessio Accardi. We are unambiguously grateful to the beamline scientists for their expert help with resources at the Advanced Light Source, a DOE User Facility, contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. This project was in part supported by NIH grants R01-GM107023 (To CM), U54-GM087519 (to SK), and grant S10OD021832 (for ALS beamline 5.0.1).

References

- 1.Baker JL, et al. Widespread genetic switches and toxicity resistance proteins for fluoride. Science. 2012;335:233–235. doi: 10.1126/science.1215063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stockbridge RB, et al. Fluoride resistance and transport by riboswitch-controlled CLC antiporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15289–15294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210896109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeAngeli A, et al. AtCLCa, a proton/nitrate antiporter, mediates nitrate accumulation in plant vacuoles. Nature. 2006;442:939–942. doi: 10.1038/nature05013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Picollo A, Malvezzi M, Houtman JC, Accardi A. Basis of substrate binding and conservation of selectivity in the CLC family of channels and transporters. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brammer AE, Stockbridge RB, Miller CF. −/Cl− selectivity in CLCF-type F−/H+ antiporters. J Gen Physiol. 2014;144:129–136. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201411225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accardi A. Structure and gating of CLC channels and exchangers. J Physiol. 2015;593:4129–4138. doi: 10.1113/JP270575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutzler R, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Gating the selectivity filter in ClC chloride channels. Science. 2003;300:108–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1082708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller C. ClC chloride channels viewed through a transporter lens. Nature. 2006;440:484–489. doi: 10.1038/nature04713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vien M, Basilio D, Leisle L, Accardi A. Probing the conformation of a conserved glutamic acid within the Cl− pathway of a CLC H+/Cl− exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 2017;149:523–529. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201611682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Accardi A, et al. Separate ion pathways in a Cl−/H+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:563–570. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim HH, Miller C. Intracellular proton-transfer mutants in a CLC Cl−/H+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:131–138. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accardi A, Miller C. Secondary active transport mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of ClC Cl− channels. Nature. 2004;427:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature02314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picollo A, Pusch M. Chloride/proton antiporter activity of mammalian CLC proteins ClC-4 and ClC-5. Nature. 2005;436:420–423. doi: 10.1038/nature03720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koide A, Wojcik J, Gilbreth RN, Hoey RJ, Koide S. Teaching an old scaffold new tricks: monobodies constructed using alternative surfaces of the FN3 scaffold. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng L, Campbell EB, Hsiung Y, MacKinnon R. Structure of a eukaryotic CLC transporter defines an intermediate state in the transport cycle. Science. 2010;330:635–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1195230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basilio D, Noack K, Picollo A, Accardi A. Conformational changes required for H+/Cl− exchange mediated by a CLC transporter. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:456–463. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khantwal CM, et al. Revealing an outward-facing open conformational state in a CLC Cl−/H+ exchange transporter. eLife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.11189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walden M, et al. Uncoupling and turnover in a Cl−/H+ exchange transporter. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:317–329. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayaram H, Accardi A, Wu F, Williams C, Miller C. Ion permeation through a Cl−-selective channel designed from a CLC Cl−/H+ exchanger. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11194–11199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804503105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Last NB, Sun S, Pham MC, Miller C. Molecular determinants of permeation in a fluoride-specific ion channel. eLife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.31259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stockbridge RB, Robertson JL, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Miller C. A family of fluoride-specific ion channels with dual-topology architecture. eLife. 2013;2:e01084. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Last NB, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Shane T, Miller C. Mechanistic signs of double-barreled structure in a fluoride ion channel. eLife. 2016;5:e18767. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picollo A, Xu Y, Johner N, Berneche S, Accardi A. Synergistic substrate binding determines the stoichiometry of transport of a prokaryotic H+:Cl− exchanger. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:525–531. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim HH, Stockbridge RB, Miller C. Fluoride-dependent interruption of the transport cycle of a CLC Cl−/H+ antiporter. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:721–725. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips S, et al. Surprises from an unusual CLC homolog. Biophys J. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Voth GA. The coupled proton transport in the ClC-ec1 Cl−/H+ antiporter. Biophys J. 2011;101:L47–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang T, Han W, Maduke M, Tajkhorshid E. Molecular basis for differential anion binding and proton coupling in the Cl−/H+ exchanger ClC-ec1. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:3066–3075. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller C, Nguitragool W. A provisional transport mechanism for a CLC-type Cl−/H+ exchanger. Phil Trans Roy Soc B. 2008;364:175–180. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Accardi A, Picollo A. CLC channels and transporters: proteins with borderline personalities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:1457–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S, Swanson JM, Voth GA. Multiscale simulations reveal key aspects of the proton transport mechanism in the ClC-ec1 antiporter. Biophys J. 2016;110:1334–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skerra A. Use of the tetracycline promoter for the tightly regulated production of a murine antibody fragment in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1994;151:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winter G. xia2: an expert system for macromolecular crystallography data reduction. J Appl Cryst. 2010;43:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans PR. An introduction to data reduction: space-group determination, scaling and intensity statistics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2011;67:282–292. doi: 10.1107/S090744491003982X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein N. CHAINSAW: a program for mutating pdb files used as templates in molecular replacement. J Appl Cryst. 2008;41:641–643. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stamm M, Staritzbichler R, Khafizov K, Forrest LR. AlignMe--a membrane protein sequence alignment web server. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:W246–251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winn MD, Murshudov GN, Papiz MZ. Macromolecular TLS refinement in REFMAC at moderate resolutions. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:300–321. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho BK, Gruswitz F. HOLLOW: generating accurate representations of channel and interior surfaces in molecular structures. BMC Struc Biol. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Crystallographic data are deposited in the Protein Data Bank: WT Eca (PDB 6D0J), E118Q (PDB 6D0K), V319G (PDB 6D0N). Source data for Figs 3d, 4b and 4c and Supplementary Fig 3 are available on request.