Abstract

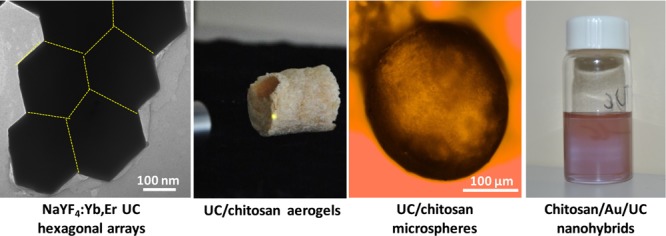

Simultaneous integration of photon emission and biocompatibility into nanoparticles is an interesting strategy to develop applications of advanced optical materials. In this work, we present the synthesis of biocompatible optical nanocomposites from the combination of near-infrared luminescent lanthanide nanoparticles and water-soluble chitosan. NaYF4:Yb,Er upconverting nanocrystal guests and water-soluble chitosan hosts are prepared and integrated together into biofunctional optical composites. The control of aqueous dissolution, gelation, assembly, and drying of NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocolloids and chitosan liquids allowed us to design novel optical structures of spongelike aerogels and beadlike microspheres. Well-defined shape and near-infrared response lead upconverting nanocrystals to serve as photon converters to couple with plasmonic gold (Au) nanoparticles. Biocompatible chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites are prepared to show their potential use in biomedicine as we find them exhibiting a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 0.58 mg mL–1 for chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanorods versus 0.24 mg mL–1 for chitosan-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er after 24 h. As a result of their low cytotoxicity and upconverting response, these novel materials hold promise to be interesting for biomedicine, analytical sensing, and other applications.

1. Introduction

Biocompatible optical nanomaterials are of interest as smart tools for applications in many fields of science and healthcare technologies.1,2 There has been an increasing demand for fabricating functional devices from these materials. In this framework, light-sensitive nanocomponents and biopolymers are considered as novel substances to combine together into promising nanocomposites.3 The optical and biocompatible responses endow these composites with a wide range of desirable properties for their prospective use in medicine, bioimaging, sensing, adsorption, and photocatalysis.4 A great potential of these composites is useful for biomedical imaging because of low cytotoxicity of biopolymers and sensitive response of optical nanoelements.5 It is of key importance to manipulate the surface, morphological, and structural features of the integrated materials to obtain a homogeneous incorporation of the functional components for improving their reaction performance.6 With multiple-purpose applications, attempts of fabricating biocompatible optical nanocomposites with different structural forms, such as spongelike aerogels, beadlike spheres, hybrids, or water-dispersible colloids, are of great significance to the scientific community.

Upconverting (UC) materials can absorb photons and emit visible light after excitation by near-infrared (NIR) light.7 The NIR-emitting luminescence is known to be a photophysical process of photon UC emission. NaYF4:Yb,Er is a well-known UC material composed of an insulating NaYF4 host and Yb3+ and Er3+ dopants incorporated into the matrix lattice.8 Remarkably, NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanocrystals can convert near-infrared light to visible light through lanthanide (Yb3+ and Er3+) doping, attributed to energy transfer pathways by dopant–host interactions.7 Thanks to structure-dependent photon efficiency, the control of the size, shape, and crystallinity of the NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanomaterials would enable the development of optical bioprobes with improved performance.9,10 Accordingly, the low-energy light absorption, high sensitivity, low toxicity, and structural stability make NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanoparticles useful as novel photon upconverters to fabricating advanced optical materials for applications in biomedical imaging, security labeling, and energy conversion.11−14

Chitosan is the deacetylated derivative of chitin as a major biopolymer component present in the shells of crustaceans15 and in the cell walls of some fungal species.16 The alkaline deacetylation of natural chitin generates polycationic networks of chitosan nanofibrils with exposed primary amine groups, which are capable of enhancing the chemical reactivity for surface functionalization. As an abundant biopolymer on the earth, many attempted syntheses have used chitosan-based materials as an aqueous stabilizer for nanoparticles,17 a fibril precursor for bioplastics and gels,18−20 and a polymer template for hierarchical porous materials.21 The aqueous solubility, low cytotoxicity, and polycation of chitosan are crucial factors in determining the efficiency of their derivatives in biomedicine. Regarding the potential for drug delivery and cellular imaging, cationic chitosan-based components have been proven to present stronger electrostatic interactions with anionic cell membranes, which facilitates cellular uptake.22 This behavior, combined with its low cytotoxic response, often results in materials with potential biomedical applications. Another interesting aspect is the homogeneous solubility of native chitosan nanofibrils in water as they typically dissolve in acidic media by surface protonation. It is thus desirable to obtain neutral aqueous liquids of native chitosan and use them as either a particle stabilizer or gelling agent for biocompatible optical nanocomposites to enhance their applications in the field of biomedicine.23−25 One notable example of this subject has been reported by Duan et al.26 on the use of the freezing–thawing process of chitosan/alkali/urea solutions to prepare biocompatible chitosan hydrogels for controlled drug release applications.

To achieve the potential of optical materials for bioimaging and analytical sensing, it is of interest to combine luminescent NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanoparticles with water-soluble chitosan into chitosan-coated UC nanocomposites. It is also interesting to control the host–guest interactions of these functional components by dispersibility, self-assembly, and solidification to design biocompatible optical nanocomposites with different structures and compositions for extending their potential uses.27 To date, several efforts have been made to prepare chitosan-functionalized NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles for near-infrared photodynamic therapy.28,29 However, there are limited descriptions on the preparation of aerogels and microspheres of NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles supported by water-soluble chitosan.

Herein, we report the synthesis of well-defined NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanocrystals and the subsequent coating with water-soluble chitosan to generate biocompatible optical nanocomposites. This combination is based on aqueous stabilization, gelation, solidification, and assembled confinement to fabricate NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aerogels, microspheres, and hybrid materials. The cytotoxic responses of chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites in comparison to those of chitosan-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles were tested to show their potential use in biomedical applications.

2. Results and Discussion

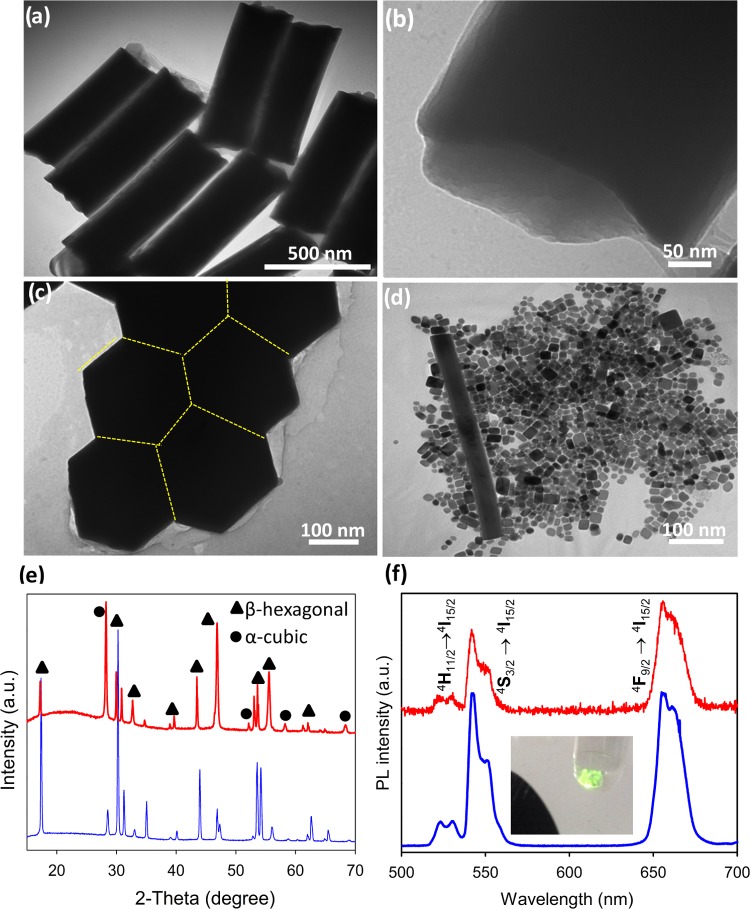

Hydrothermal treatment of a basic solution of lanthanide nitrates, sodium fluoride, and oleic acid (OA) in a water/ethanol mixture at 190 °C yielded OA-capped NaYF4 UC nanocrystals codoped with 20 wt % Yb3+ and 2 wt % Er3+ (Figure S1a). We found that the precursor concentration and reaction time have a major influence on the morphological distribution of the as-prepared UC nanocrystals. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images in Figure 1a–c show that the UC nanocrystals are uniform single-crystalline hexagonal nanorods with concave ends having 150 nm sized six facets and ∼800 nm length. The synthetic product is a particle mixture of 20 nm sized cubes and ∼100 × 1500 nm2 sized rods when the precursor concentration used is 2 times greater than that of the UC hexagonal nanorods (Figure 1d). This shape variation is related to the evolution gradient of monomers in the bulk solution.30 Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analyses (Figure S1b) confirm the presence of Na, F, Y, Yb, and Er with a similar atomic ratio in these UC nanoparticles prepared using the low and high precursor concentrations. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analyses (Figure 1e) show a binary mixture of a major hexagonal β-phase and a minor cubic α-phase in highly crystalline NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods.31 Conversely, the cube-/rod-shaped NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles contain the cubic α-phase predominantly rather than the hexagonal β-phase. The relative intensity of the (100) diffraction peak of the NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods is much larger than that of the NaYF4:Yb,Er cubes/nanorods, suggesting that the elongation axis of the hexagonal nanorods is along the [100] direction. Note that in the NaYF4:Yb,Er structure the β-hexagonal phase is thermodynamically stable, whereas the α-cube phase is metastable. There is thus a crystal transition of an α-cube phase to a β-hexagonal phase in the NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanoparticles prepared upon extended heating.

Figure 1.

Shape-controlled synthesis of OA-capped NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanocrystals. (a) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of UC hexagonal nanorod arrays, (b) TEM image of an individual UC hexagonal nanorod viewed along its tip, (c) TEM image viewed along a tip of assembled UC hexagonal nanorods showing concave surfaces, (d) TEM image of cube-/rod-shaped UC nanocrystals, (e) PXRD patterns, and (f) UC photoluminescence (PL) spectra of NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods (red) and NaYF4:Yb,Er cube-/rod-shaped nanocrystals (blue). The inset shows a photo of UC hexagonal nanorod powders emitting brilliant green color under 980 nm laser excitation.

The OA-capped NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanocrystals emit brilliant green light when excited under near-infrared laser light (980 nm), where the hexagonal nanorods exhibit stronger emission than the cubes/nanorods (inset of Figure 1f). Photoluminescence spectra (Figure 1f) of the OA-capped NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods under 980 nm laser excitation show three main emission peaks at 522.5, 541.5, and 655.5 nm as a result of the 4H11/2–4I15/2 (green), 4S3/2–4I15/2 (green), and 4F9/2–4I15/2 (red) UC transitions, respectively, of Er3+ dopants.32 The OA-capped UC nanocube/rods also exhibit three main peaks at the same wavelengths as in the OA-capped UC hexagonal nanorods but display a lower emission intensity. The appearance of the enhanced photoluminescence in the NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods is due to the β-hexagonal phase being predominant than the α-cubic one.

The well-defined NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods with sensitive NIR photoresponse can be used as novel converters for the design of functional optical materials. Much progress has been made toward achieving structural diversity of the NaYF4:Yb,Er-based nanomaterials for a variety of applications.33 Notable examples are metal–organic framework/NaYF4:Ln core–shells for NIR-enhanced photocatalysis,34 NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles for latent fingerprints,35 NaYF4:Yb,Er UC/magnetite/dye nanocomposites for oxygen sensing,36 lipid-coated NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles for bioimaging and gene delivery,37 and CdSe/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanohybrids for photovoltaics.38 Owing to the inherent characteristics of low-energy light absorption with minimal cell damage, the NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles are extensively used in biomedicine. The goal of this strategy is limited to the cytotoxicity of the lanthanide-doped UC nanoparticles with biopolymers to achieve the biocompatibility. Consequently, we combined the NaYF4:Yb,Er-based hexagonal nanorods with water-soluble chitosan to design different structural types of biocompatible optical composites.

We found that water-soluble chitosan macromolecules could be prepared by acetylation of native chitosan nanofibrils with acetic anhydride and sequential dissolution of acetylated chitosan in water to form an optically clear aqueous solution. This solubility is different from that of conventional chitosan prepared by alkaline deacetylation of chitin as it often does not dissolve in water because of the high crystallinity of the fibrils.39 It is noteworthy that our acetylation procedure can yield the homogeneous aqueous solution of chitosan polymorphs rather than crystalline fibrils as confirmed by PXRD (Figure S2). The acetylation-induced aqueous dissolution of chitosan is assumed to present disrupted hydrogen bonding within the fibrils, leading to the decreased crystallinity. As a result, the acetylated chitosan fibrils swell dramatically in water and then fully dissolve to form a viscous polymeric liquid.

The hydrophobic surface of the OA-capped NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles renders them dispersible in nonpolar solvents, but they could not be in the form of the aqueous dispersion. The surface modification of the as-prepared NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles with hydrophilic and biocompatible properties is thus an important step to extend their potential to biomedicine. We prepared the aqueous dispersion of chitosan-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles by sequential coating of the OA-capped UC colloids with ethylene glycol and water-soluble chitosan. Remarkably, the resulting NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles became dispersible in water as the aqueous colloidal solution can be stable for several months (Figure S11). Infrared spectra (Figure S3) of the functionalized UC nanoparticles show distinct stretching bands of amides and hydroxyls, verifying that the OA-capped nanoparticles adsorbed with chitosan. Notably, the surface coating of the OA-capped NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocolloids with water-soluble chitosan mostly retains the morphological, dispersible, and optical features (Figures 2c and S4).

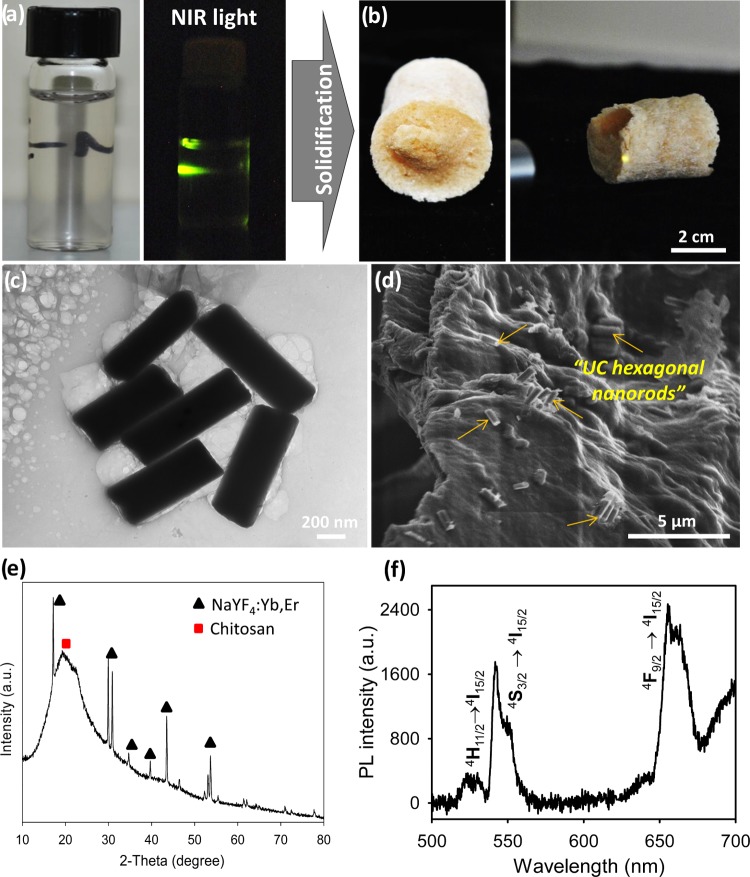

Figure 2.

Formation of aerogel composites from water-soluble chitosan and NaYF4:Yb,Er UC hexagonal nanorods. (a) Photos of UC/chitosan aqueous dispersion under visible light (left) and under NIR light (right), (b) photos of UC/chitosan aerogel composites under visible light (left) and NIR light (right), (c) TEM image of the UC/chitosan aqueous dispersion, (d) SEM image of UC/chitosan aerogel composites, (e) PXRD pattern, and (f) UC photoluminescence spectrum of UC/chitosan aerogel composites.

Owing to their low density, large porosity, and high surface area, optical biopolymer aerogels are an exciting class of soft materials for applications in sensing, absorption, insulation, and tissue engineering.40−42 We found that the prepared water-soluble chitosan is a good polymeric matrix to support the chitosan-functionalized NaYF4:Yb,Er colloids, encouraging us to fabricate NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aerogels. The chitosan-coated NaYF4:Yb,Er colloids and glyoxal cross-linkers were mixed with water-soluble chitosan to form a homogeneous and optically transparent dispersion. These mixtures were thermally gelated at 80 °C to form NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan hydrogels (Figure S5). The removal of water in the hydrogels by freeze-drying yielded intact NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aerogel composites (Figure 2b, right). Under lyophilization, the frozen NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan hydrogels released water by sublimation to leave large interconnected interspaces in solidified networks, forming NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aerogels. The aerogel structure appears to be a homogeneous porous network of highly interconnected chitosan nanofibrils, where no phase separation of the NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles is observed, indicating a good distribution of the UC guests into the biopolymer host.

The aerogel composite is a heterogeneous mixture of α,β-NaYF4:Yb,Er crystals and chitosan polymorphs (PXRD, Figure 2e). The aerogel composites are thermally stable up to ∼300 °C, above which chitosan is decomposed to leave ∼10 wt % of oxidized NaYF4:Yb,Er component (thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), Figure S6). SEM images (Figure 2d) of the aerogel composites show the random distribution of the NaYF4:Yb,Er nanorods in the aerogel networks of the solidified chitosan assemblies. These results reveal that the glyoxal-crosslinked gelation of NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aqueous dispersions occurs upon curing to form gel composites. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of the NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan composites show a mesoporous structure, indicative of forming macro–mesoporous networks in the aerogels (Figure S6a). Laser excitation of the composites at 980 nm emits visible green light through the aerogels, reflecting a good guest/host combination (Figure 2b, left). Photoluminescence spectra (Figure 2f) of the aerogels show UC emission peaks, with the wavelengths and intensities mostly resembling those of the pristine NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocrystals, suggesting that the sequential gelation and solidification of water-soluble chitosan retain the optical properties of the UC nanoparticles. Although many nanostructures of luminescent chitosan composite gels based on nanocarbons43−45 and nanosemiconductors,46,47 for example, have been reported, this is the first preparation of the upconverting NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aerogels. Apart from their promising biomedical applications, the enlarged porous networks may facilitate the diffusion of volatile reactants to make the UC/chitosan aerogels useful as gas optical sensors.48

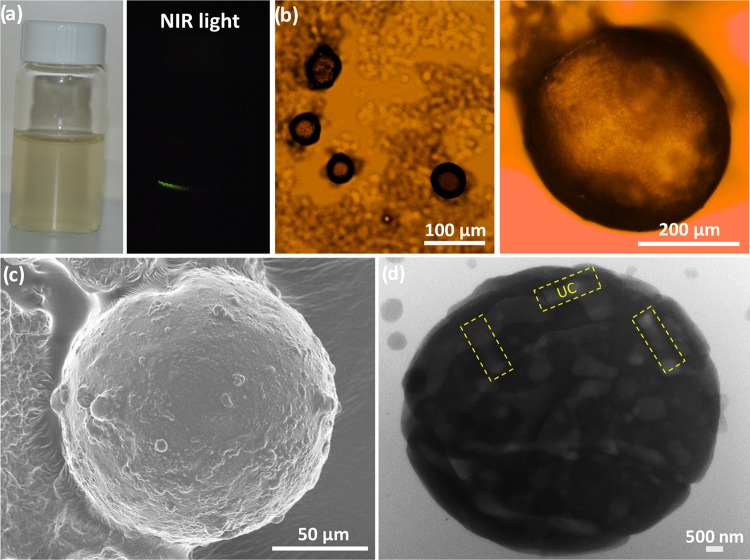

Optical biopolymer microsphere colloids have aroused attention for applications in drug delivery.49,50 Keeping this demand in mind, we further explored the fabrication of NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan microspheres. In general, the NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aqueous dispersions can self-organize into microspheres via microemulsion-assisted assembly, where the optical guests are embedded within the chitosan host. The synthesis involves a precursor aqueous phase confined in an oil/surfactant phase. The precursor aqueous phase was prepared by mixing the chitosan-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er aqueous dispersion and glyoxal with water-soluble chitosan to form a homogeneous mixture. The solvent (oil) phase was prepared by dissolving Span 80 surfactant in paraffin. An emulsion system was prepared by mixing these phases together under sequential stirring and sonication. The emulsion mixture was transferred into a round-bottomed flask, sealed, and then heated to 80 °C under moderate stirring to crosslink chitosan by glyoxal, producing solidified NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan microspheres. We first examined the synthesized materials using optical microscopy. It is apparent from the optical images that both the solidified products before and after purification are dispersible microspheres (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Self-assembly of NaYF4:Yb,Er UC hexagonal nanorods with water-soluble chitosan into microspheres. (a) Photos of UC/chitosan microsphere aqueous dispersion under visible light (left) and NIR light (right), (b) optical microscopy images of UC/chitosan microspheres in the microemulsion dispersion (left) and aqueous media (right), and (c) SEM image and (d) TEM image of UC/chitosan microspheres.

The solidified microspheres were collected and dispersed in water to form a microsphere aqueous solution (Figure 3a, left). On shining the 980 nm laser light through the samples, the solidified products and their aqueous solutions both emit green light (Figure 3a, right). Structural and elemental analyses reveal that the solidified product is a heterogeneous mixture of α,β-NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocrystals and chitosan polymorphs (PXRD, Figure S7a). Thermal analyses (Figure S7b) confirm ∼5 wt % NaYF4:Yb,Er in the chitosan-based composites. Photoluminescence spectrum (Figure S8) of the microsphere composites shows the retention of the spectral features of the pristine NaYF4:Yb,Er nanorods. SEM images (Figures 3c and S9) of the solidified products show a broad size distribution of microspheres in the diameter range of 150–200 μm. The NaYF4:Yb,Er nanorods embedded within the chitosan microspheres seem to be distinguished by TEM, as presented in Figures 3d and S10. These analyses confirm the formation of the photoluminescent NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan microspheres in the microemulsion system with the assistance of the Span 80 nonionic surfactant. In the oil/water phases, the hydrophobic alkyl tails of the surfactant move forward to the oil phase (paraffin), whereas its hydrophilic oleate heads (functional groups) move forward oppositely to the aqueous phase (water). This chemical behavior leads to the formation of stable sphere-shaped micelles containing NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aqueous hydrogels confined within the paraffin oil phase. Under glyoxal crosslinking and curing, the NaYF4:Yb,Er-supported chitosan networks can be crosslinked to form rigid hydrogel microspheres. Although several examples have recently been reported for chitosan spheres, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first combination of NaYF4:Yb,Er UC nanoparticles and water-soluble chitosan into the biocompatible optical microsphere colloids.

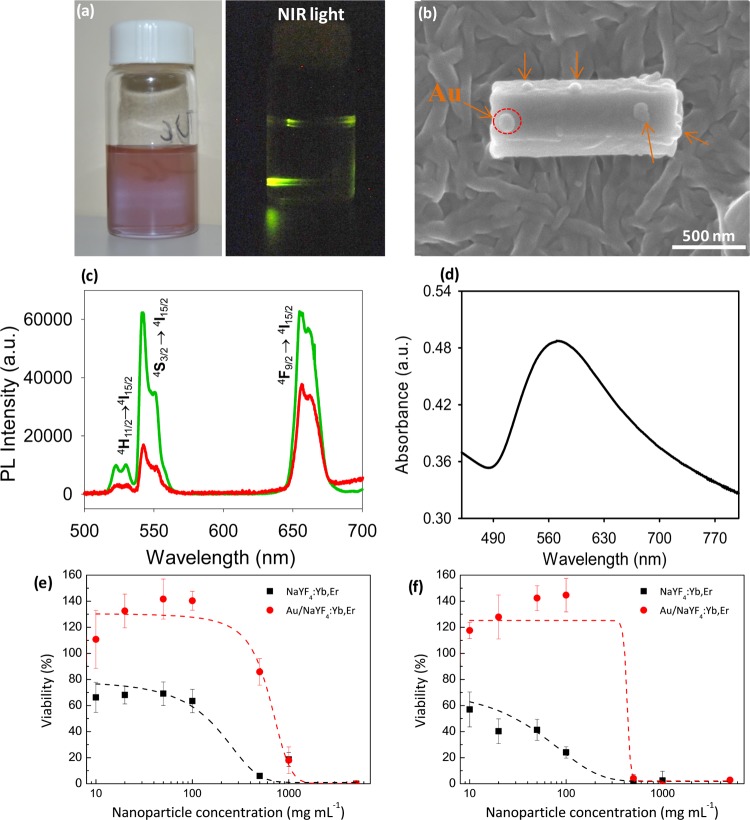

The structural design of the nanomaterials with multioptical properties is also a goal to enhance their desirable functionalities.27,51 We realized that the well-defined anisotropic shape and good dispersity can lead the NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods to serve as an efficient UC support for plasmonic additives. In a typical preparation, a HAuCl4 ethylene glycol solution was mixed with an OA-capped NaYF4:Yb,Er ethanol dispersion under stirring to form a homogeneous mixture. These mixed dispersions were hydrothermally treated at 80 °C to prepare Au/NaYF4:Er,Yb nanocomposites. The reaction mixtures slowly turned from yellow to purple upon heating, indicating the formation of Au nanoparticles (Figure 4a). PXRD analyses reveal the structural retention of α,β-NaYF4 crystals in the nanocomposites, and the Au component could not be detected, possibly due to its low loading concentration (Figure S12). However, electron microscope images (Figure 4b) show the surface deposition of some uniform Au nanodots with ∼50 nm particle size on the single NaYF4:Er,Yb nanorods. These structural analyses confirm the selective decoration of the Au nanoparticles on the NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods to generate plasmonic upconverting nanohybrids.

Figure 4.

Water-soluble chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites and their dose-dependent cytotoxicity. (a) Photos of chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposite aqueous dispersion under visible light (left) and NIR light (right), (b) SEM image of Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites, (c) UC photoluminescence spectra of Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites (green) in comparison to those of NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods (red), (d) UV–vis absorption spectrum of Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites and WST-1 viability assay of chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites in comparison to those of chitosan-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods after 24 h (e) and 72 h (f).

Ethylene glycol can act as a weak reductant to perform the polyol-assisted reduction of some metal ions under hydrothermal conditions. At elevated temperature, ethylene glycol is able to slowly reduce Au3+ into small Au nanoparticles, which are then attached on the NaYF4:Er,Yb nanorods. The weak reduction allows one to control the growth and size distribution of the Au nanodots in the nanocomposites. This hydrothermal polyol reduction provides an advantage over conventional methods, which often use strong reductants such as NaBH4 or ascorbic acid to obtain deposited Au nanoparticles with larger irregular sizes, as additionally evidenced in Figure S14. The UC emission peaks of the Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites have the same wavelengths as those of the pristine NaYF4:Yb,Er nanorods (three maxima at 522.5, 541.5, and 655.5 nm); however, their spectral emission has a significantly higher intensity (Figure 4c). UV–vis spectra (Figure 4d) of the Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites show a maximum plasmon absorbance at ∼540 nm for the Au nanoparticles. The plasmon-enhanced upconverting photoluminescence in the Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites may be caused by the plasmon–photon coupling effect, as recently reported elsewhere.52,53

To explore the biomedical compatibility, we further prepared chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites by dispersing the ethylene glycol-capped Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites in water-soluble chitosan. A stable colloidal solution of the Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanohybrids can be obtained after sonication (Figure 4a). Again, the aqueous stability of these nanocomposite colloids is due to the surface adsorption of water-soluble chitosan. The chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites maintain the morphological integrity of the pristine samples (Figure S15).

We investigated the cytotoxic response of the chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites (Figure 4a) in comparison to that of the chitosan-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles (Figure S11) to assess their suitability for biomedical diagnosis. In this sense, the lack of the functional moieties on the UC nanoparticle surfaces is often an obstacle that needs to be addressed for biomedical applications. To date, the UC nanoparticles have been coated with silica, sodium gluconate, poly(ethylene glycol), poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(acrylic acid), cationic conjugated polyelectrolytes, phosphatidylcholine, and hyaluronate to improve their biocompatibility.54−58 Our present work has used native chitosan polycation as a water-soluble biopolymer to coat the NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles and Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanohybrids for generating the novel biocompatible optical composites.22

Figure 4e,f shows the cytotoxic response of these materials. The experimental results were performed by incubating different concentrations of nanoparticles from 10 to 5000 μg mL–1 with living cells in culture for 24 and 72 h. The dose response for the chitosan-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles presents half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) of 240 and 96 μg mL–1 after 24 and 72 h, respectively. After Au deposition, the respective EC50 value is notably increased to 580 and 410 μg mL–1, respectively. The high cell viability of the chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites is remarkable, which is found to be more than 80% when incubated for 24 h at the concentration of 500 μg mL–1. Overall, these UC nanocomposites present enhanced biocompatibility in comparison to that reported in previous works.59 This enhancement may arise from the chitosan coating to avoid the possible release of toxic lanthanide ions to the surrounding cellular environment.60 Indeed, Tian et al.61 proved that ligand-free lanthanide-doped nanoparticles are cytotoxic because of the cellular adenosine triphosphate deprivation of cells. These UC nanoparticles induced cell death through autophagy and apoptosis because of the interactions between the particles and phosphate groups. They concluded that the best practice is to limit the concentration of the UC nanoparticles below 100 μg mL–1, which is high enough to ensure proper cell imaging and still far below the EC50 here obtained after 24 h.

The NIR response, aqueous dispersity, biocompatibility, and low cytotoxicity reported here indicate that the chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanohybrids may be useful as a promising bioprobe for the imaging of tissues with minimal cell damage.62 Additionally, recent studies have shown that the plasmonic upconverting coupling at the nanoscale may induce photothermal effects by direct laser irradiation through luminescence resonance emission transfer from NaYF4:Yb,Er to Au.63 This photon transfer behavior also makes these hybrid nanoparticles interesting for exploiting hyperthermia therapy.

3. Conclusions

In summary, we have shown the fabrication of biocompatible chitosan-functionalized optical nanocomposites based on near-infrared-sensitive upconverting nanoparticles. Hydrophobic NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods synthesized by hydrothermolysis were used as a photon upconverter. Water-soluble chitosan was prepared by acetylation of native chitosan nanofibrils and used to functionalize the NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocrystals into biocompatible optical nanomaterials. The novelty of the aqueous solubility and polymorphs led water-soluble chitosan to serve as a stabilizer, gel matrix, and spherical support for the upconverting nanomaterials. This homogeneous combination allowed us to design the upconverting nanocomposites with different structures of aqueous colloid, aerogel, microsphere, and hybrid. The simultaneous integration of NIR response and biocompatibility endows the optical materials with biofunctionality, as we have demonstrated the low cytotoxic response of the chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites. These novel materials are useful for extended studies in biomedicine, bioimaging, drug delivery, and analytical sensing.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Preparation of NaYF4:Yb,Er Upconverting Nanocrystals

An aqueous basic mixture of ionic coprecursors (lanthanide and fluoride with the desired concentration) and 0.23 g of NaOH, 4.73 g of oleic acid, 6.6 mL of ethanol, and 1.0 mL of water was prepared under vigorous stirring until a translucent solution was obtained. The reaction mixture was transferred into a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated to 190 °C. After the hydrothermal treatment for 24 h, the white product that precipitated out of the mixture was collected at the bottom of the autoclave. The product was washed with ethanol and harvested by centrifugation to obtain OA-capped NaYF4:Yb,Er upconverting nanocrystals. Hexagonal rod-shaped nanocrystals were formed using lanthanide nitrates (150 mg of Y(NO3)3, 108 mg of Yb(NO3)3, and 11 mg of Er(NO3)3) and 116 mg of NaF, whereas the 2-fold increased precursor concentration formed cube-/rod-shaped nanocrystals.

4.2. Preparation of Water-Soluble Chitosan

Chitin was chemically purified from crab shells by deproteinization and decalcification. The purified chitin (∼25 g) was treated at least twice with a concentrated NaOH aqueous solution (50 wt %, 500 mL) at 90 °C for 8 h to obtain chitosan flakes. The prepared chitosan was immersed in ethanol to remove adsorbed water. The dried chitosan (∼5 g) was added to 40 mL pure acetic anhydride to perform acetylation at room temperature within 4 h. The acetylated chitosan was collected from the reaction solution by filtration, dabbed with tissue paper, and washed quickly with distilled water to remove adsorbed acetic anhydride. The resulting samples were immersed in water to make them swell and then dissolved into a homogeneous chitosan aqueous solution.

4.3. Preparation of NaYF4:Yb,Er/Chitosan Aerogel Composites

OA-capped NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods (∼60 mg) were dispersed in 20 mL of water-soluble chitosan (∼3 wt %) in the presence of 0.5 mL of glyoxal to form a homogenous mixture after stirring for 1 h. The reaction mixture was hydrothermally treated at 80 °C for 6 h to crosslink chitosan by glyoxal. Upon thermal crosslinking, gelation of the reaction mixture occurred, forming hydrogel composites. The resulting hydrogels were freeze-dried to recover NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan aerogel composites.

4.4. Preparation of NaYF4:Yb,Er/Chitosan Microsphere Composites

An aqueous-in-oil microemulsion system was designed to prepare NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan microsphere composites. The aqueous phase is ∼2 mg of NaYF4:Yb,Er nanorods/1.25 mL of water-soluble chitosan (∼3 wt %)/0.1 mL of glyoxal, whereas the oil phase is 1.25 g of Span 80/30 mL paraffin. These phases were mixed together in a flask reactor, forming a cloudy emulsion system after stirring and sonication. The flask reactor was sealed and heated at 80 °C to crosslink chitosan by glyoxal within 48 h. The solidified microspheres were collected by adding 40 mL hexane into the microemulsion, followed by centrifugation. The white solidified product of NaYF4:Yb,Er/chitosan microsphere composites was washed with ethanol and dispersed in water.

4.5. Preparation of Chitosan-Stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er Nanocomposites

OA-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er hexagonal nanorods (∼5 mg) were added to 20 mL of ethylene glycol containing 0.01 mg of HAuCl4. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h and then hydrothermally treated at 80 °C under stirring for 20 h to form a purple solution. These nanocomposites were collected and purified with Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites with ethanol and then added to water-soluble chitosan (20 mL, ∼1 wt %) under stirring and sonication to form a chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er aqueous dispersion.

4.6. Cytotoxicity Assay

Dose-dependent cytotoxicity of chitosan-stabilized NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoparticles and chitosan-stabilized Au/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocomposites after 24 and 72 h was evaluated according to the WST-1 viability assay. First, the nanoparticles were sterilized by irradiation for 10 min. Then, they were washed by spinning them down at 1000 rpm for 5 min, and the resulting solution was replaced with fresh growth media (MEM-α with glutamax, 1% P/S, 10% fetal bovine serum). DU145 human prostate cancer cells were then seeded in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 1000 cells/well. After 24 h, media in wells were replaced with the nanoparticle media solution at various concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 1 mg mL–1. Positive control wells (100% viability) were established by adding fresh media to a row of cells, whereas negative control wells (0% viability) were established by adding an excessive amount of nanoparticle solution (5 mg mL–1). The EC50 of the cells was determined by plotting relative cell viability (relative to positive and negative controls in %) in OriginPro. Each experiment was repeated six times.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Foundation for Science and Technology Development of Vietnam under grant number 104.06-2014.87 for funding. H.V.D. thanks financial support from the Hue University Foundation Programme (DHH 2016-02-83). M.S.S. acknowledges support from EPSRC (EP/P001114/1).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01355.

Chemicals, structural characterization, IR, EDX, TGA, PXRD, SEM, TEM, PL spectra, nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms, and photos (PDF)

Author Present Address

◆ L.V.N.: Department of Electronics and Telecommunications, Saigon University, 273 An Duong Vuong Street, Ho Chi Minh 700000, Vietnam

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhou J.; Yang Y.; Zhang C. Y. Toward biocompatible semiconductor quantum dots: from biosynthesis and bioconjugation to biomedical application. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11669–11717. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J.; Yang M.; Duan Y. Chemistry, biology, and medicine of fluorescent nanomaterials and related systems: new insights into biosensing, bioimaging, genomics, diagnostics, and therapy. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6130–6178. 10.1021/cr200359p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algar W. R.; Prsuhn D. E.; Stewart M. H.; Jennings T. L.; Canosa J. B. B.; Dawson P. E.; Medintz I. L. The controlled display of biomolecules on nanoparticles: a challenge suited to bioorthogonal chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22, 825–858. 10.1021/bc200065z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang D.; Wang X.; Jia C.; Lee T.; Guo X. Molecular-scale electronics: from concept to function. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 4318–4440. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenen S. J.; Parak W. J.; Rejman J.; Manshian B. (Intra)cellular stability of inorganic nanoparticles: effects on cytotoxicity, particle functionality, and biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2109–2135. 10.1021/cr400714j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihan S. A.; Emmerling S. G. J.; Butt H. J.; Berger R.; Gutmann J. S. Soft nanocomposites - from interface control to interphase formation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 12380–12386. 10.1021/am507572q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X.; Liu X.; Huang W.; Bettinelli M.; Liu X. Lanthanide-activated phosphors based on 4f–5d optical transitions: theoretical and experimental aspects. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 4488–4527. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepuk A.; Casola G.; Schumacher C. M.; Kramer K. W.; Stark W. J. Purification of NaYF4-based upconversion phosphors. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2015–2020. 10.1021/cm403459v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boles M. A.; Engel M.; Talapin D. V. Self-assembly of colloidal nanocrystals: from intricate structures to functional materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11220–11289. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B.; Shi B.; Jin D.; Liu X. Controlling upconversion nanocrystals for emerging applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 924–936. 10.1038/nnano.2015.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Chen G.; Shen J.; Li Z.; Zhang Y.; Han G. Upconversion nanoparticles: a versatile solution to multiscale biological imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 166–175. 10.1021/bc5003967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Liu Q.; Feng W.; Sun Y.; Li F. Upconversion luminescent materials: advances and applications. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 395–465. 10.1021/cr400478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates E. L.; Chinnapongse S. L.; Kim J. H.; Kim J. H. Engineering light: advances in wavelength conversion materials for energy and environmental technologies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 12316–12328. 10.1021/es303612p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.; Du S. R.; Zheng X. Y.; Lyu G. M.; Sun L. D.; Li L. D.; Zhang P. Z.; Zhang C.; Yan C. H. Lanthanide nanoparticles: from design toward bioimaging and therapy. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 10725–10815. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrés E.; Jove D. A.; Biarnes X.; Moerschbacher B. M.; Guernin M. E.; Planas A. Structural basis of chitin oligosaccharide deacetylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6882–6887. 10.1002/anie.201400220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Xu C.; Zhang Q.; Wang S.; Fang W. Evolution of the chitin synthase gene family correlates with fungal morphogenesis and adaption to ecological niches. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44527 10.1038/srep44527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konwar A.; Kalita S.; Kotoky J.; Chowdhury D. Chitosan-iron oxide coated graphene oxide nanocomposite hydrogel: a robust and soft antimicrobial biofilm. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 20625–20634. 10.1021/acsami.6b07510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez J. G.; Ingber D. E. Manufacturing of large-scale functional objects using biodegradable chitosan bioplastic. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2014, 299, 932–938. 10.1002/mame.201300426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araki J.; Yamanaka Y.; Ohkawa K. Chitin-chitosan nanocomposite gels: reinforcement of chitosan hydrogels with rod-like chitin nanowhiskers. Polym. J. 2012, 44, 713–717. 10.1038/pj.2012.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi A. R.; Khodadadi A. Mechanically robust 3d nanostructure chitosan-based hydrogels with autonomic self-healing properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 27254–27263. 10.1021/acsami.6b10375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo E.; Li W.; Bhangu S. K.; Ashokkumar M. Chitosan microspheres as a template for TiO2 and ZnO microparticles: studies on mechanism, functionalization and applications in photocatalysis and H2S removal. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 19373–19383. 10.1039/C7RA01227F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Wang X.; Chen F.; Zhang Q.; Dong B.; Yang H.; Liu G.; Zhu Y. Functionalization of upconverted luminescent NaYF4:Yb/Er nanocrystals by folic acid-chitosan conjugates for targeted lung cancer cell imaging. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 7661–7667. 10.1039/c0jm04468g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota N.; Eguchi Y. Facile preparation of water-solution N-acetylated chitosan and molecular weight dependence of its water-solubility. Polym. J. 1997, 29, 123–127. 10.1295/polymj.29.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Qiu F.; Wu H.; Li X.; Zhang T.; Niu X.; Yang D.; Pan J.; Xu J. Novel water-soluble chitosan linked fluorescent carbon dots and isophorone diisocyanate fluorescent material toward detection of chromium(VI). Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 8554–8565. 10.1039/C6AY02822E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Xia W.; Liu P.; Cheng Q.; Tahi T.; Gu W.; Li B. Chitosan modification and pharmaceutical/biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1962–1987. 10.3390/md8071962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J.; Liang X.; Cao Y.; Wang S.; Zhang L. High strength chitosan hydrogels with biocompatibility via new avenue based on constructing nanofibrous architecture. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 2706–2714. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D. M.; Etxarri A. G.; Salleo A.; Dionne J. A. Plasmon-enhanced upconversion. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 4020–4031. 10.1021/jz5019042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui S.; Chen H.; Zhu H.; Tian J.; Chi X.; Qian Z.; Achilefu S.; Gu Y. Amphiphilic chitosan modified upconversion nanoparticles for in vivo photodynamic therapy induced by near-infrared light. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 4861–4873. 10.1039/c2jm16112e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou A.; Wei Y.; Wu B.; Chen Q.; Xing D. Pyropheophorbide A and c(RGDyK) comodified chitosan-wrapped upconversion nanoparticle for targeted near-infrared photodynamic therapy. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 9, 1580–1589. 10.1021/mp200590y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.; Li C.; Shi Z. Current advances in lanthanide-doped upconversion nanostructures for detection and bioapplication. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1600029 10.1002/advs.201600029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirch J.; Schneider A.; Abou B.; Hopf A.; Schaefer U. F.; Schneider M.; Schall C.; Wagner C.; Lehr C. M. Optical tweezers reveal relationship between microstructure and nanoparticle penetration of pulmonary mucus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 18355–18360. 10.1073/pnas.1214066109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin K.; Jung T.; Lee E.; Lee G.; Goh Y.; Heo J.; Jung M.; Jo E. J.; Lee H.; Kim M. G.; Lee K. T. Distinct mechanisms for the upconversion of NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ nanoparticles revealed by stimulated emission depletion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 9739–9744. 10.1039/C7CP00918F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S. Perspectives for upconverting nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2017, 10644–10653. 10.1021/acsnano.7b07120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Zhen Z.; Zheng Y.; Cui C.; Li C.; Li Z. Controlled growth of metal-organic framework on upconversion nanocrystals for NIR-enhanced photocatalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 2899–2905. 10.1021/acsami.6b15792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Zhu Y.; Mao C. Synthesis of NIR-responsive NaYF4:Yb,Er upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles using an optimized solvothermal method and their applications in enhanced development of latent fingerprints on various smooth substrates. Langmuir 2015, 31, 7084–7090. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b01151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheucher E.; Wilhelm S.; Wolhelm S.; Hirsch T.; Mayr T. Composite particles with magnetic properties, near-infrared excitation, and far-red emission for luminescence-based oxygen sensing. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2015, 1, 15026 10.1038/micronano.2015.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song C.; Zhang S.; Zhou Q.; Shi L.; Du L.; Zhi D.; Zhao Y.; Zhen Y.; Zhao D. Bifunctional cationic solid lipid nanoparticles of β-NaYF4:Yb,Er upconversion nanoparticles coated with a lipid for bioimaging and gene delivery. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 26633–26639. 10.1039/C7RA02683H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C.; Dadvand A.; Rosei F.; Perepichka D. F. Near-IR photoresponse in new up-converting CdSe/NaYF4:Yb,Er nanoheterostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8868–8869. 10.1021/ja103743t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh E. R.; Schauer C. L.; Qadri S. B.; Price R. P. Chitosan cross-linking with a water-soluble, blocked diisocyanate. 1. Solid state. Biomacromolecules 2002, 3, 1370–1374. 10.1021/bm025625z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley M. A.; Pauzauskie P. J.; Olson T. Y.; Biener J.; Satcher J. H. Jr.; Baumann T. F. Synthesis of graphene aerogel with high electrical conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 14067–14069. 10.1021/ja1072299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen J. T.; Kettunen M.; Ras R. H. A.; Ikkala O. Hydrophobic nanocellulose aerogels as floating, sustainable, reusable, and recyclable oil absorbents. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 1813–1816. 10.1021/am200475b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Li S.; Chen C.; Yan L. Self-assembly and embedding of nanoparticles by in situ reduced graphene for preparation of a 3D graphene/nanoparticle aerogel. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 5679–5683. 10.1002/adma.201102838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omidi M.; Yadegari A.; Tayebi L. Wound dressing application of pH-sensitive carbon dots/chitosan hydrogel. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 10638–10649. 10.1039/C6RA25340G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Mukherjee S.; Yi J.; Banerjee P.; Chen Q.; Zhou S. Biocompatible chitosan-carbon dot hybrid nanogels for NIR-imaging-guided synergistic photothermal-chemo therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 18639–18649. 10.1021/acsami.7b06062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogoi N.; Barooah M.; Majumdar G.; Chowdhury D. Carbon dots rooted agarose hydrogel hybrid platform for optical detection and separation of heavy metal ions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 3058–3067. 10.1021/am506558d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Zhang L.; Yao W.; Qian H.; Ding D.; Wu W.; Jiang X. Water-soluble chitosan-quantum dot hybrid nanospheres toward bioimaging and biolabeling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 995–1002. 10.1021/am100982p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansur A. A. P.; Mansur H. S.; Araujo A. S.; Lobato Z. I. P. Fluorescent nanohybrids based on quantum dot-chitosan-antibody as potential cancer biomarkers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 11403–11412. 10.1021/am5019989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green K. K.; Wirth J.; Lim S. F. Nanoplasmonic upconverting nanoparticles as orientation sensors for single particle microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 762 10.1038/s41598-017-00869-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan R.; Li X.; Deng J.; Gao X.; Zhou L.; Zheng Y.; Tong A.; Zhang X.; You C.; Guo G. Dual drug loaded biodegradable nanofibrous microsphere for improving anti-colon cancer activity. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28373 10.1038/srep28373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Zaloga J.; Ding Y.; Liu Y.; Janko C.; Pischetsrieder M.; Alexiou C.; Boccaccini A. R. Facile preparation of multifunctional superparamagnetic PHBV microspheres containing spions for biomedical applications. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23140 10.1038/srep23140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.; Qiu H.; Prasad P. N.; Chen X. Upconversion nanoparticles: design, nanochemistry, and applications in theranostics. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5161–5214. 10.1021/cr400425h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. L.; Estakhri N. M.; Johnson A.; Li H. Y.; Xu L. X.; Zhang Z.; Alu A.; Wang Q. Q.; Shih C. K. Tailoring plasmonic enhanced upconversion in single NaYF4:Yb3+/Er3+ nanocrystals. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10196 10.1038/srep10196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K.; Jung K.; Kwon S. J.; Jang H. S.; Byun D.; Han I. K.; Ko H. Plasmonic nanowire-enhanced upconversion luminescence for anticounterfeit devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 7836–7846. 10.1002/adfm.201603428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D.; Meng L.; Chen Y.; Hu M.; Chen Y.; Huang C.; Shang J.; Wang R.; Gou Y.; Yang J. NaGdF4:Yb3+/Er3+@NaGdF4:Nd3+@sodium-gluconate: multifunctional and biocompatible ultrasmall core-shell nanohybrids for UCL/MR/CT multimodal imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 16257–16265. 10.1021/acsami.5b05194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H. Q.; Peng H. Y.; Liu K.; Bian M. H.; Xu Y. J.; Dong L.; Yan X.; Xu W. P.; Tao W.; Shen J. L.; Lu Y.; Qian H. S. Sequential growth of NaYF4:Yb/Er@NaGdF4 nanodumbbells for dual-modality fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 9226–9232. 10.1021/acsami.6b16842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W.; Lu X.; Jiang R.; Fan Q.; Zhao H.; Deng W.; Zhang L.; Huang L.; Huang W. Water-soluble conjugated polyelectrolyte brush encapsulated rare-earth ion doped nanoparticles with dual-upconversion properties for multicolor cell imaging. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 9012–9014. 10.1039/c3cc45400b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X.; Xu M.; Yuan W.; Wang Q.; Shi Y.; Feng W.; Li F. A water-dispersible dye-sensitized upconversion nanocomposite modified with phosphatidylcholine for lymphatic imaging. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 13389–13392. 10.1039/C6CC07180E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.; Lv K.; Wang B.; Li L.; Wang B.; Liu M.; Guo H.; Wang A.; Lu Y. Design, synthesis and antitubercular evaluation of benzothiazinones containing an oximido or amino nitrogen heterocycle moiety. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 1480–1483. 10.1039/C6RA25712G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becerro A. I.; Mancebo D. G.; Cantelar E.; Cusso F.; Stepien G.; Fuente J. M.; Ocana M. Ligand-free synthesis of tunable size Ln:BaGdF5 (Ln = Eu3+ and Nd3+) nanoparticles: luminescence, magnetic properties, and biocompatibility. Langmuir 2016, 32, 411–420. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Zhan S.; Yang Q.; Yan M. Synthesis of biocompatible uniform NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ nanocrystals and their characteristic photoluminescence. J. Lumin. 2012, 132, 3042–3047. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2012.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J.; Zeng X.; Xie X.; Han S.; Liew Q. W.; Chen Y. T.; Wang L.; Liu X. Intracellular adenosine triphosphate deprivation through lanthanide-doped nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6550–6558. 10.1021/jacs.5b00981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König K. Laser tweezers and multiphoton microscopes in life sciences. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2000, 114, 79–92. 10.1007/s004180000179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. W.; Lee P. H.; Chan Y. C.; Hsiao M.; Chen C. H.; Wu P. C.; Wu P. R.; Tsai D. P.; Tu D.; Chen X.; Liu R. S. Plasmon-induced hyperthermia: hybrid upconversion NaYF4:Yb/Er and gold nanomaterials for oral cancer photothermal therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 8293–8302. 10.1039/C5TB01393C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.