Abstract

A thiourea-based tripodal receptor L substituted with 3-nitrophenyl groups has been synthesized, and the binding affinity for a variety of anions has been studied by 1H NMR titrations and nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy experiments in dimethyl sulfoxide-d6. As investigated by 1H NMR titrations, the receptor binds an anion in a 1:1 binding mode, showing the highest binding and strong selectivity for sulfate anion. A competitive colorimetric assay in the presence of fluoride suggests that the sulfate is capable of displacing the bound fluoride, showing a sharp visible color change. The strong affinity of L for sulfate was further supported by UV–vis titrations and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Time-dependent DFT calculations indicate that the fluoride complex possesses a different optical absorption spectrum (due to charge transfer between the fluoride and the surrounding ligand) than the sulfate complex, reflecting the observed colorimetric change in these two complexes. The receptor was further tested for its biocompatibility on primary human foreskin fibroblasts and HeLa cells, exhibiting an excellent cell viability up to 100 μM concentration.

Introduction

Anions play an important role in many environmental and biological systems,1 and the mechanistic understanding of selective anion recognition by synthetic receptors is critical in the field of supramolecular chemistry.2,3 Although polyamine-based receptors are known to bind anions strongly, their binding occurs only at a certain pH, hampering their practical application under neutral conditions.4 On the other hand, neutral receptors such as amides,5−7 ureas,8,9 thioureas,10−12 pyrroles,13,14 and indoles15,16 are suitable for binding anions with their H-bond donor groups regardless of the solution pH. Recently, tren-based receptors bearing urea or thiourea functional groups have been an area of focus for anion recognition due to the directional conformation and enhanced chelation effect of the NH groups.17−23 In particular, the electron-withdrawing nature of sulfur on thiourea functionalities increases the acidity of NH for H-bonding interactions with an anionic guest.23 For example, a chlorosubstituted tris(thiourea) receptor reported by Das et al. was shown to encapsulate a thiosulfate anion with a dimeric capsular assembly.20 A tris(4-nitrophenyl)thiourea receptor was reported to exhibit selective complexation of fluoride and phosphate.21 A naphthyl-substituted tripodal thiourea synthesized by Wu et al. was shown to bind H2PO4– and HSO4– anions in dimethylformamide (DMF).19 Furthermore, attaching chromophore groups to receptors often leads to a spectroscopic or color change, allowing them to serve as sensors for target analytes.10,11 In our previous study, we have shown that a dipodal thiourea-based receptor containing 4-nitrophenyl groups as chromophores displays a visible color change upon the addition of fluoride or dihydrogen phosphate in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).11 Herein, we report a thiourea-based tripodal receptor L substituted with 3-nitrophenyl groups, which shows a strong selectivity for sulfate. The selectivity was further supported by competitive colorimetric studies, displaying a sharp visible color change upon the addition of sulfate to the fluoride complex of L. First-principles calculations, including both density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT), are carried out to support and provide a mechanistic insight into our experimental results.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

In an effort to design suitable chromogenic thiourea receptors for anion binding, we synthesized a 3-nitrophenyl-based tripodal tris-thiourea (L) by reacting tris(2-aminoethyl)amine and 3-nitrophenylisothiocyanate in CH2Cl2 (Scheme 1). A 3-nitrophenyl substituent was attached to the thiourea moiety due to its electron-withdrawing nature, which can provide enhanced H-bonding and chromogenic properties of the receptor,22 making it suitable for the naked-eye detection of anions.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of L.

(i) CH2Cl2 and (ii) refluxing, 75 °C, 6 h.

X-ray Analysis

Single crystals of [L(DMF)2] were obtained from the slow evaporation of a DMF solution of L with an excess amount of HI in a vial at room temperature. The needle-shaped yellow crystals were isolated by a simple decantation technique. Although the initial goal was to obtain an iodide complex, crystallographic analysis showed that, instead of iodide anions, two solvent molecules are bonded to L through hydrogen-bonding interactions (Figure 1). The formation of [L(DMF)2] crystals in the presence of HI can be described by a low association constant of the receptor for iodide, as confirmed by solution-binding studies. X-ray structural analysis of the crystal reveals that the complex crystallizes in the triclinic space group P-1 to give a molecular formula, [L(DMF)2], in which two solvent molecules bonded to thiourea NH groups are attached to two different arms of the tripodal host. Attempts to grow X-ray-quality crystals of L with anions were unsuccessful.

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal structure of [L(DMF)2].

NMR Titration Studies

1H NMR titrations of L were performed to evaluate its binding affinity for a variety of anions (F–, Cl–, Br–, I–, ClO4–, NO3–, H2PO4–, HSO4–, and SO42–) using their tetrabutyl ammonium salts in DMSO-d6. Figure 2 shows the stacking of 1H NMR spectra as obtained from the titration of L with SO42– (0–10 equiv). In the 1H NMR spectrum of L, one NH proton is observed at 10.01 (H1) ppm and the other one at 7.95 (H2) ppm. The addition of SO42– to L resulted in a significant downfield shift of both NH signals (Δδ = 1.49 ppm for H1 and Δδ = 1.81 ppm for H2) with a sharp saturation at a 1:1 ratio (Figure 3), demonstrating strong interactions of the receptor and sulfate. Similar downfield shifts in the NH signals, but to a lesser extent, were also observed for HSO4– (Δδ = 0.72 ppm for H1 and Δδ = 0.71 ppm for H2), Cl– (Δδ = 0.61 ppm for H1 and Δδ = 0.38 ppm for H2), and Br– (Δδ = 0.09 ppm for H1 and Δδ = 0.06 ppm for H2) at the end of titrations. The NH signals of L were shown to be broadened and eventually disappeared upon the addition of H2PO4–. In this case, CH signals were used to calculate the binding constant. However, for I–, NO3–, and ClO4–, a negligible change in the NMR signals was observed. The binding constants of L for these anions were determined from a nonlinear regression analysis of the progressive changes in NH or CH signals with a 1:1 binding model.24 The binding data are listed in Table 1, showing that the receptor binds strongly to SO42–, with an association constant larger than 104 M–1 (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Partial 1H NMR spectra of L (2 mM) showing changes in the NH chemical shifts with an increasing amount of SO42– (20 mM) in DMSO-d6. (H1 = CSNHAr and H2 = CH2NHCS).

Figure 3.

1H NMR titration plot of L showing changes in the NH chemical shifts of the receptor with an increasing amount of SO42– in DMSO-d6. (H1 = CSNHAr and H2 = CH2NHCS).

Table 1. Binding Constants (log K) and Binding Energies (E) of the Anions Complexes of L.

| anion | log Ka | log Kb | E (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F– | >4.0c | 5.1 | 182 |

| Cl– | 3.1 | 3.2 | 107 |

| Br– | 1.9 | 1.7 | 116 |

| I– | <1d | <1e | f |

| SO42– | >4.0 | 6.4 | 217 |

| HSO4– | 2.9 | 2.8 | 97 |

| H2PO4– | 3.0 | 3.1 | 112 |

| NO3– | <1d | <1e | 107 |

| ClO4– | <1d | <1e | 87 |

Determined by 1H NMR titrations in DMSO-d6.

Determined by UV titrations in DMSO.

Slow proton exchange.

No appreciable change was observed in 1H NMR spectra.

No appreciable change was observed in UV spectra.

The 6-31+G(d,p) basis set is not available for iodide.

In contrast, upon the addition of fluoride to L, a new set of NMR signals appeared downfield as a result of a slow proton exchange between the free receptor and the complex (Figure S6). The signals of the free receptor disappeared completely upon the addition of 1 equiv of fluoride (Figure 4). There is some evidence that highly basic anions can abstract acidic protons from NH of urea/thiourea-based compounds.25,26 A detailed study on the deprotonation and hydrogen-bonding aspects between anions and urea/thiourea-based receptors reported by Pérez-Casas and Yatsimirsky suggested that the deprotonation is accompanied by the disappearance of NMR signals of the abstracted protons, whereas the binding event results in the downfield shift of NMR signals of NH groups in a receptor.26 The distinct downfield shift of NH signals in our receptor is consistent with the formation of a hydrogen-bonded complex (instead of deprotonation). This assumption is further supported by two-dimensional (2D) nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY), exhibiting cross-peaks for both NH1 and NH2 after the addition of 1 equiv of fluoride to L (Figure S16). For further clarification, a control experiment was carried out using OH–, showing the complete disappearance of NH signals due to the deprotonation of NH by highly basic hydroxide ions (E, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Partial 1H NMR spectra of L showing changes in the chemical shifts after the addition of 1 equiv of different anions in DMSO-d6.

The binding constant for fluoride was calculated from the relative changes in the integrated intensity of NH signals for the free receptor and the complex,22 yielding a binding constant larger than 104 M–1. To determine the selectivity of the receptor, competition experiments were performed in which sulfate was added to the receptor containing 1 equiv of fluoride (C, Figure 4) or hydroxide (E, Figure 4) in DMSO-d6. As shown in Figure 4, the 1H NMR spectrum of L containing an equivalent amount of fluoride and sulfate (D), or hydroxide and sulfate (F), resembles the spectrum of L containing 1 equiv of sulfate (B), thus demonstrating the selectivity of the receptor for sulfate. The receptor also exhibits good interactions for Cl–, HSO4–, and H2PO4–, with association constants of 3.1, 2.9, and 3.0 (in log K), respectively. However, it does not show any appreciable affinity for I–, NO3–, or ClO4–.

NOESY NMR Studies

Two-dimensional NOESY NMR experiments were performed to illustrate the structures and conformational changes of the anion complexes in the solution, following the methods reported earlier.23,27 To this aim, the 2D NOESY spectra were recorded for free L (2 mM) and its mixture containing 1 equiv of the respective anions in DMSO-d6 (Figures 5 and S15–S23). Figure 5a shows the NOESY NMR of free L, exhibiting a strong H1···H2 NOESY contact. After the addition of 1 equiv of sulfate, the NOESY contacts completely disappeared (Figure 5b), indicating an interaction of NHs with the added anion and a possible anion-induced conformational change of the receptor.23 Indeed, the receptor shows significant affinity for SO42–, as observed from the 1H NMR titrations (Table 1). We also observed a similar loss of NOESY contacts for L in the presence of HSO4– (Figure 5c) and F– (Figure S16). In particular, we observed both cross-peaks for NH1 and NH2 for L after the addition of fluoride, indicating that these protons are present on the receptor and involved in the binding process. The addition of chloride to the receptor results in the weakening of the H1···H2 contact, suggesting a weak interaction, which is in agreement with the results obtained from the NMR titrations. In contrast, the corresponding signals were almost unchanged after the addition of 1 equiv of Br–, I–, NO3–, or ClO4– (Figure 5d and the Supporting Information), suggesting the lack of interactions between the receptor and the added anion.

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional NOESY NMR of (a) free L, (b) L + SO42–, (c) L + HSO4–, and (d) L + ClO4– in DMSO-d6 (H1 = CSNHAr and H2 = CH2NHCS). In each case, a stock solution of an anion (20 mM) was added to L (2 mM) to maintain a 1:1 molar ratio of receptor to anion.

Colorimetric Studies

The receptor was further investigated by naked-eye colorimetric studies for anions in DMSO. As shown in Figure 6, a visible color change from pale yellow to orange was observed after the addition of 1 equiv of fluoride to L (2 mM), indicating a different optical absorption spectrum of the [LF]− complex, as also confirmed by TD-DFT calculations (discussed later). However, the color remained almost unchanged for other anions. A similar color change was reported previously due to the addition of fluoride to related receptors.11 To examine the visual selectivity, 1 equiv of different anions was added separately to an orange solution of fluoride complex in DMSO. Interestingly, the color of [LF]− was sharply changed to a pale yellow color (original color of the receptor) after the addition of sulfate (Figure 7). This observation suggests that sulfate can compete with fluoride for hydrogen bonding with NH groups and displace the bound fluoride from the complex [LF]− into the solution (Figure 8), which is in agreement with the NMR competition experiments (Figure 4). However, other anions are not strong enough to displace the bound fluoride, supporting the results of NMR and UV–vis titrations. Thus, the fluoride–receptor complex serves as a colorimetric probe for visual identification of sulfate through fluoride displacement assay, a principle that is known as an indicator displacement assay widely used for the optical sensing of analytes.28−30

Figure 6.

Colorimetric studies of the receptor L (2 mM) with 1 equiv of different anions in DMSO.

Figure 7.

Colorimetric studies of [LF]− after the addition of 1 equiv of different anions in DMSO, showing a visual color change for sulfate.

Figure 8.

Mechanism of fluoride displacement assay of [LF]− with SO42– from the receptor’s cavity, showing a visible color change in DMSO.

UV–Vis Titration Studies

UV–vis titrations were also performed to investigate the interactions of the receptor with anions in DMSO. As shown in Figure 9, the addition of sulfate to a solution of L results in a systematic decrease in the absorbance with a red shift of the peak at 335 nm, suggesting the formation of a [L(SO4)]2– complex.22 The relative absorbance I/I0 of L (where I0 and I represent the absorbance of L before and after the addition of an anion, respectively) upon the gradual addition of SO42– gave the best fit to a 1:1 binding mode (Figure 9, inset),24 yielding a binding constant of 6.40 (in log K). The host showed a similar spectral change when it was titrated with dihydrogen phosphate (Figure S30). The addition of fluoride anion to L also showed a decrease in the absorption at 335 nm, but no appreciable shift was observed as compared to that for sulfate or phosphate. However, the naked-eye colorimetric study shows an orange color after the addition of just 1 equiv of fluoride to the receptor in which the concentration of L was different (2 mM) than that used in UV titrations (0.15 mM).

Figure 9.

UV–vis titration spectra showing the changes in absorption spectra of L (1.5 × 10–4 M) with an increasing amount of SO42– (1.5 × 10–2 M) in DMSO (inset showing the titration plot).

To confirm if the color originated from the binding with fluoride (instead of deprotonation), the receptor was deprotonated by adding 1 equiv of hydroxide. The resulting intense red color of the deprotonated receptor is distinctly different than that developed for the fluoride complex (Figure S34), suggesting that the observed orange color (for the receptor containing fluoride) originated from the binding event. Further justification of this assumption is provided by control experiments from UV studies of the receptor containing 1 equiv of hydroxide or fluoride in DMSO (Figure S33). In the UV spectrum, a new absorption band appeared at about 485 nm for the solution of L containing hydroxide anion, indicating an anion-induced deprotonation of L due to the removal of NH protons by a highly basic OH–.26 However, such a band is absent for the solution of L containing fluoride (Figure S33). The addition of 1 equiv sulfate to L mixed with fluoride (or hydroxide) shows a nearly similar spectrum to that obtained from the sulfate complex. This further supports the displacement of the bound fluoride by sulfate, which is in accordance with the NMR results discussed previously. On the other hand, the addition of other anions to L solution does not induce an appreciable change in the absorption spectrum (Supporting Information). This observation is fully consistent with colorimetric observations, showing no visible color change for Cl–, Br–, I–, ClO4–, NO3–, and HSO4–.

Computational Studies

To quantitatively understand the interactions of the various anions with the receptor, theoretical calculations using both ground-state density functional theory (DFT) and excited-state time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) were carried out. For the ground-state binding energies, an all-electron, polarized 6-31G(d,p) basis set was used in conjunction with the M06-2X functional. Extensive previous work by us has shown that the M06-2X functional accurately predicts the binding energy trends for noncovalent interactions between anions and organic receptors.31,32 Fully unconstrained geometry optimizations were carried out on both the isolated receptor as well as the various molecular-bound complexes. With the optimized geometry, the binding energy was calculated with the expression Ebinding = EX + Ereceptor – Ecomplex, where X represents an anion (described further below). The calculated binding energies of the complexes are listed in Table 1. Notably, we find that the magnitudes of the binding energies are proportional to the charge and electronegativity of anions, with fluorine and sulfate having the largest binding energy, in agreement with the experimental binding constants (Table 1).

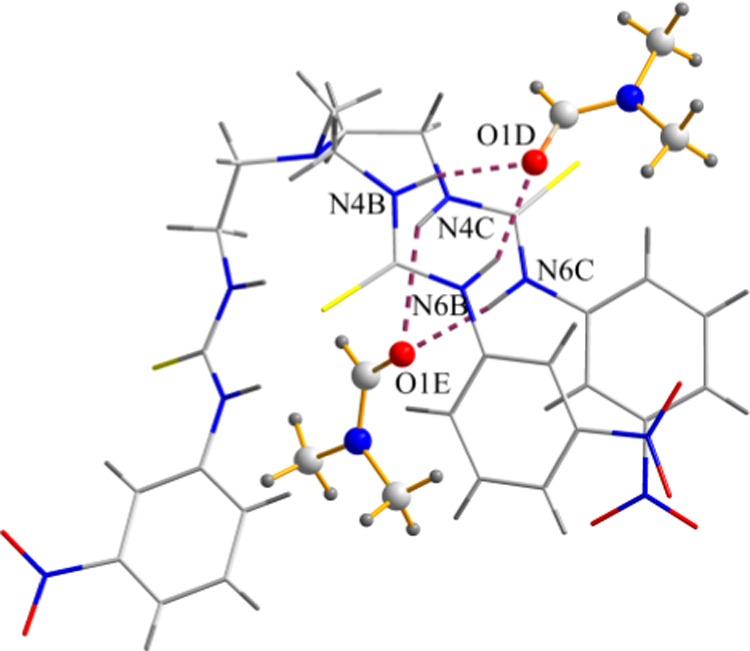

The optimized structures of L complexes with F– and SO42– are shown in Figures 10 and 11, respectively. In the fluoride complex of L, one fluoride is encapsulated within the cavity via a total six NH···F bonds, exhibiting a 1:1 binding mode. Such a binding mode is consistent with that observed in solution binding studies in DMSO-d6. In the optimized structure of the sulfate complex, three oxygen atoms of the anion are H-bonded with two NHs from two different arms of the receptor, forming a total of six hydrogen bonds. However, the other oxygen atom is uncoordinated. The corresponding hydrogen bonding distances are listed in Table 2.

Figure 10.

Optimized structures of [LF]− showing perspective view (left) and space filling model (right). All of the hydrogens on the carbon atoms are omitted for clarity.

Figure 11.

Optimized structures of [L(SO4)]2– showing perspective view (left) and space filling model (right). All of the hydrogens on the carbon atoms are omitted for clarity.

Table 2. Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions (Å) for the Complexes of L with Fluoride and Sulfate Calculated with DFT at the M06-2X/6-31G(d,p) Level of Theory.

| [LF]− |

[L(SO4)]2– |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| D–H···A | D···A (Å) | D–H···A | D···A (Å) |

| N20–H···F | 2.831 | N22–H···O78 | 2.906 |

| N31–H···F | 2.710 | N31–H···O78 | 2.729 |

| N22–H···F | 2.817 | N20–H···O79 | 2.899 |

| N33–H···F | 2.720 | N29–H···O79 | 2.729 |

| N24–H···F | 2.852 | N24–H···O80 | 2.903 |

| N29–H···F | 2.692 | N33–H···O80 | 2.728 |

To give further support to the observed colorimetric solution experiments, we also carried out high-level time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations. To account for charge-transfer effects in these complexes, we used a customized LC-ωPBE range-separated functional, which incorporates 20% Hartree–Fock exchange over the entire range with a full 100% exchange at asymptotic distances. In our previous work on range-separated functionals, we have shown that maintaining a full 100% contribution of asymptotic Hartree–Fock exchange is essential for accurately describing valence excitations in even relatively simple molecular systems.33−35Figure 12 depicts the calculated TD-DFT absorption spectra for the F– and SO42– complexes obtained by solving for the lowest 20 excited states in the presence of a dimethyl sulfoxide polarizable continuum solvent. Our TD-DFT calculations indicate that the fluoride complex has a different optical absorption spectrum whereas all of the other anions are fairly similar, in agreement with experiment. In particular, Figure 12 indicates that the spectrum for the F– complex is more blue-shifted than the SO42– complex. To understand this further, we also carried out a charge-density difference analysis for the first electronic excited state of the fluoride, and sulfate complexes (Figure 13). The charge-density differences show that the first allowed excited state in each complex is due to charge being transferred between the benzene ring and the NO2 functional group. Moreover, due to the higher charge of the sulfate complex, a larger surrounding positive charge (light blue) can be seen in Figure 13b compared to the positive charge in the fluoride complex (Figure 13a).

Figure 12.

Absorption spectra obtained from TD-DFT calculations for the lowest 20 excited states for the fluoride and sulfate complexes in a DMSO polarizable continuum solvent.

Figure 13.

Charge-density difference for the first excited state of the (a) fluoride and (b) sulfate complexes.

Cytotoxicity Assessment

The biocompatibility of L as a receptor was tested by analyzing the viability of two types of living cells, including primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HF) and HeLa cells. Each type of cell was treated with L at concentrations ranging from 10 to 500 μM for 24 h, and the cell viability was quantified using trypan blue exclusion assay. As a control, cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO. The results from the exclusion assay revealed that the cell viability of HF or HeLa cells was almost unaffected up to 100 μM concentration of the receptor (Figure 14). However, the cell cytotoxicity was observed at a higher concentration (500 μM). Live cell imaging was also performed on both types of cells at 24 h after treatment, showing no cytotoxic effects up to 100 μM (Figures S35 and S36). These results are in accord with the cell viability data, further demonstrating an excellent biocompatibility of the receptor on living cells.

Figure 14.

Effect of L on cell viability. Confluent HF (A) and HeLa (B) cells were either mock treated (0.1% DMSO-treated control) or treated with L (10–500 μM) for 24 h. Triplicate samples were used, and error bars represent the standard error of mean.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have synthesized and structurally characterized a thiourea-based tripodal receptor L, showing strong binding and selectivity for sulfate over other anions in DMSO. The selectivity of L for sulfate was further confirmed by the competitive colorimetric studies, displaying a sharp color change of [LF]−, whereas other anions showed no change in color. This observation suggests that the added sulfate is capable of displacing the bound fluoride in [LF]−, and this compound can be used as a colorimetric probe to detect sulfate in the solution via a fluoride displacement assay. The strong selectivity of L for sulfate was further supported by UV–vis titrations in DMSO. First-principles calculations including both DFT and TD-DFT indicate that the fluoride complex has a different optical absorption spectrum, whereas all of the other anions are almost similar, in agreement with the experiment. The receptor also shows an excellent biocompatibility in the human foreskin fibroblasts or HeLa cells. The strong selectivity for sulfate and excellent biocompatibility toward living cells demonstrates that this receptor can be used as a potential sensing probe for the detection of sulfate anions for various biological and chemical applications.

Experimental Section

General

All of the reagents and solvents were purchased as reagent grade and used without further purification. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Varian Unity INOVA 500 FT-NMR. Chemical shifts for the samples were measured in DMSO-d6 and calibrated against the sodium salt of 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid (TSP) as an external reference in a sealed capillary tube. NMR data were processed and analyzed with MestReNova version 6.1.1-6384. The IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer-Spectrum One Fourier transform infrared spectrometer with KBr disks in the range of 4000–400 cm–1. The melting point was determined on a Mel-Temp (Electrothermal 120 VAC 50/60 Hz) melting point apparatus and was uncorrected. Mass spectral data were obtained at electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) positive mode on a TSQ Quantum GC (Thermo Scientific). Elemental analysis was carried out using an ECS 4010 Analytical Platform (Costech Instrument) at Jackson State University.

Synthesis

L

Tris(2-aminoethyl) amine (520 μL, 3.34 mmol) was added to 3-nitrophenylisothiocyanate (1.843 g, 10.03 mmol) in dichloromethane (400 mL) at room temperature under constant stirring. The mixture was refluxed for 6 h. A pale yellow precipitate was formed, and the precipitate collected by filtration was washed by dichloromethane and dried under vacuum overnight to give the neutral tripodal host (L). Yield: 2.25 g, 98%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, TSP): δ 10.01 (s, 3H, Ar-NH), 8.55 (s, 3H, ArH), 7.95 (s, 3H, CH2NH), 7.88 (d, J = 7.90 Hz, 3H, ArH), 7.81 (d, J = 7.80 Hz, 3H, ArH), 7.54 (t, J = 8.15 Hz, 3H, ArH), 3.64 (br, 6H, NHCH2), 2.80 (t, J = 6.10 Hz, 6H, NCH2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 180.31 (C=S), 147.5 (Ar-C), 140.9 (ArC-NO2), 129.7 (Ar-CH), 128.2 (Ar-CH), 117.8 (Ar-CH), 116.1 (Ar-CH), 51.7 (NHCH2), 41.7 (NCH2). Mp 135 °C. Anal. Calcd for C27H30N10O6S3: C, 47.22; H, 4.40; N, 20.39. Found: C, 47.68; H, 4.42; N, 20.45. ESI-MS (+ve): m/z 686.7. IR (KBr): ν(N–H) 3342, 3268 cm–1; ν(C=S) 740 cm–1; ν(NO2) 1518, 1342 cm–1.

L(DMF)2

In an attempt to get the iodide complex, 25 mg (0.05 mmol) of L was mixed with a few drops of HI in 15 mL DMF at room temperature, and the mixture was kept in an open vial. X-ray-quality crystals of L(DMF)2 were grown after 7 days and collected by filtration.

NMR Studies

Binding constants were obtained by 1H NMR titrations of L with the oxoanions (NO3–, ClO4–, H2PO4–, HSO4–, and SO42–) and halides (F–, Cl–, Br–, and I–) using their tetrabutyl ammonium salts in DMSO-d6. Initial concentrations were [L]0 = 2 mM and [anion]0 = 20 mM. Each titration was performed by 13 measurements at room temperature. The association constant K was calculated by fitting several independent NMR signals with a 1:1 association model using Sigma Plot software, from the following equations

where L is the receptor and A is the anion. The error limit in K was less than 10%.

Two-dimensional NOESY NMR experiments were performed for free L and L containing 1 equiv of respective anions in DMSO-d6, using the initial concentration of the receptor as 2 mM. A stock solution of an anion (20 mM) was added to the solution of L to keep a 1:1 molar ratio of receptor to anion.

UV–Vis Binding Studies

UV–vis titration studies were performed by titrating L with anions in DMSO at 25 °C. In this case, initial concentrations of L and the anions were 1.5 × 10–4 and 1.5 × 10–2 M, respectively. Each titration was performed by 15 measurements ([A–]0/[L]0 = 0–35 equiv), and the binding constant K was calculated by fitting the relative UV–vis absorbance (I/I0) with a 1:1 association model using the following equation

where L is the ligand and A is the anion. The error limit in K was less than 15%.

DFT Calculations

Binding energies and structural optimization of fluoride and sulfate complexes were evaluated with density functional theory (DFT) calculations,36 and optical properties were calculated using time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations. All of the calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 09 package of programs.37

Cytotoxicity Assay

Primary human foreskin-derived fibroblasts (HF) and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Cellgro, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (SAFC, Lenexa, KS), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Cellgro) at 37 °C with 5% CO2.38 Cells were seeded in 12-well plates and grown until they became confluent (approximately 24 h). The media was removed, and fresh complete medium was added. A stock solution of L was made in 100% DMSO at 500 mM concentration. Cells were treated with L at a final concentration of 10–500 μM in different wells for 24 h for cytotoxic assessment. In this experiment, 0.1% was the highest concentration of DMSO that the cells received. As a mock control, cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO without L. At the end point, cells were observed under an inverted Evos-FL microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and bright-field images of living cells were captured. After imaging, the viability of cells was determined using trypan blue exclusion assay,39 as previously described.40

Acknowledgments

The National Science Foundation is acknowledged for a CAREER award (CHE-1056927) to M.A.H. NMR core facility at Jackson State University was supported by the National Institutes of Health (G12RR013459). B.M.W. acknowledges the National Science Foundation for the use of supercomputing resources through the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), Project No. TG-ENG160024. M.H.H. and R.T. are supported by American Heart Association (Award No. 14SDG20390009). The diffractometer was paid for in part by the National Science Foundation (grant CHE-0130835).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01485.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Anion Coordination Chemistry; Bowman-James K., Bianchi A., Garcia-España E., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gale P. A.; Howe E. N. W.; Wu X. Anion receptor chemistry. Chem 2016, 1, 351–422. 10.1016/j.chempr.2016.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel M.; Hiscock J. R.; Gale P. A. Anion receptor chemistry: Highlights from 2010. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 480–520. 10.1039/C1CS15257B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. A. Inclusion complexes of halide anions with macrocyclic receptors. Curr. Org. Chem. 2008, 12, 1231–1256. 10.2174/138527208785740265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy C. R.; Loeb S. J. Amide based receptors for anions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 240, 77–99. 10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00304-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. A.; Llinares J. M.; Powell D.; Bowman-James K. Multiple hydrogen bond stabilization of a sandwich complex of sulfate between two macrocyclic tetraamides. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 2936–2937. 10.1021/ic015508x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. A.; Kang S. O.; Powell D.; Bowman-James K. Anion receptors: a new class of amide/quaternized amine macrocycles and the chelate effect. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 1397–1399. 10.1021/ic0263140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola V.; Fabbrizzi L.; Mosca L. Anion recognition by hydrogen bonding: urea-based receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3889–3915. 10.1039/b822552b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. A.; Begum R. A.; Day V. W.; Bowman-James K.. Amide and Urea-Based Receptors. In Supramolecular Chemistry: From Molecules to Nanomaterials; Gale P. A., Steed J. W., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gale P. A.; Howe E. N. W.; Wu X. Anion receptor chemistry. Chem 2016, 1, 351–422. 10.1016/j.chempr.2016.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khansari M. E.; Wallace K. D.; Hossain M. A. Synthesis and anion recognition studies of a dipodal thiourea-based sensor for anions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 438–440. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.11.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bose P.; Dutta R.; Santra S.; Chowdhury B.; Ghosh P. Combined solution-phase, solid-phase and phase-interface anion binding and extraction studies by a simple tripodal thiourea receptor. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 5791–5801. 10.1002/ejic.201200776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Custelcean R.; Delmau L. H.; Moyer B. A.; Sessler J. L.; Cho W.-S.; Gross D.; Bates G. W.; Brooks S. J.; Light M. E.; Gale P. A. Calix[4]pyrrole: An old yet new ion-pair receptor. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2537–2542. 10.1002/anie.200462945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessler J. L.; Gross D. E.; Cho W.-S.; Lynch V. M.; Schmidtchen F. P.; Bates G. W.; Light M. E.; Gale P. A. Calix[4]pyrrole as a chloride anion receptor: solvent and countercation effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 12281–12288. 10.1021/ja064012h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates G. W.; Light M. E.; Albrecht M.; Gale P. A. 2,7-Functionalized indoles as receptors for anions. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 8921–8927. 10.1021/jo701702p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K.-J.; Moon D.; Lah M. S.; Jeong K.-S. Indole-based macrocycles as a class of receptors for anions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7926–7929. 10.1002/anie.200503121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custelcean R.; Moyer B. A.; Hay B. P. A coordinatively saturated sulfate encapsulated in a metal-organic framework functionalized with urea hydrogen-bonding groups. Chem. Commun. 2005, 5971–5973. 10.1039/b511809c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar I.; Lakshminarayanan P. S.; Arunachalam M.; Suresh E.; Ghosh P. Anion complexation of a pentafluorophenyl-substituted tripodal urea receptor in solution and the solid state: selectivity toward phosphate. Dalton Trans. 2009, 4160–4168. 10.1039/b820322a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H.; Yi S.; Wu S. Study on host-guest complexation of anions based on tripodal naphthylthiourea derivatives. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1999, 12, 2751–2754. 10.1039/a904942h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A.; Das G. Encapsulation of divalent tetrahedral oxyanions of sulfur within the rigidified dimeric capsular assembly of a tripodal receptor: first crystallographic evidence of thiosulfate encapsulation within neutral receptor capsule. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 10792–10802. 10.1039/c2dt30999h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey S. K.; Das G. Encapsulation of trivalent phosphate anion within a rigidified π-stacked dimeric capsular assembly of tripodal receptor. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 12048–12051. 10.1039/c1dt11195g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portis B.; Mirchi A.; Emami Khansari M.; Pramanik A.; Johnson C. R.; Powell D. R.; Leszczynski J.; Hossain M. A. An ideal C3-symmetric sulfate complex: molecular recognition of oxoanions by m-nitrophenyl- and pentafluorophenyl-functionalized hexaurea receptors. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 5840–5849. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khansari M. E.; Mirchi A.; Pramanik A.; Johnson C. R.; Leszczynski J.; Hossain M. A. Remarkable hexafunctional anion receptor with operational urea-based inner cleft and thiourea-based outer cleft: Novel design with high-efficiency for sulfate binding. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6032 10.1038/s41598-017-05831-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H. J.; Kramer R.; Simova S.; Schneider U. Solvent and salt effects on binding constants of organic substrates in macrocyclic host compounds. A general equation measuring hydrophobic binding contributions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 6442–6448. 10.1021/ja00227a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boiocchi M.; Del Boca L.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Fabbrizzi L.; Licchelli M.; Monzani E. Anion-induced urea deprotonation. Chem. - Eur. J. 2005, 11, 3097–3104. 10.1002/chem.200401049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Casas C.; Yatsimirsky A. K. Detailing hydrogen bonding and deprotonation equilibria between anions and urea/thiourea derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 2275–2284. 10.1021/jo702458f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A.-F.; Wang J.-H.; Wang F.; Jiang Y.-B. Anion complexation and sensing using modified urea and thiourea-based receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3729–3745. 10.1039/b926160p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B. T.; Anslyn E. V. Indicator-displacement assays. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 3118–3127. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhaman M. M.; Alamgir A.; Wong B. M.; Powell D. R.; Hossain M. A. A highly efficient dinuclear Cu(II) chemosensor for colorimetric and fluorescent detection of cyanide in water. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 54263–54267. 10.1039/C4RA10813B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhaman M. M.; Fronczek F. R.; Powell D.; Hossain M. A. Colourimetric and fluorescent detection of oxalate in water by a new macrocycle-based dinuclear nickel complex: A remarkable red shift of fluorescence band. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 4618–4621. 10.1039/c3dt53467g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basaran I.; Khansari M. E.; Pramanik A.; Wong B. M.; Hossain M. A. An exclusive fluoride receptor: Fluoride-induced proton transfer to a quinoline-based thiourea. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 1467–1470. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik A.; Powell D. R.; Wong B. M.; Hossain M. A. Spectroscopic, structural, and theoretical studies of halide complexes with a urea-based tripodal receptor. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 4274–4284. 10.1021/ic202747q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong B. M.; Cordaro J. G. Coumarin dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells: A long-range-corrected density functional study. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 214703–214708. 10.1063/1.3025924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong B. M.; Hsieh T. H. Optoelectronic and excitonic properties of oligoacenes: substantial improvements from range-separated time-dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 3704–3712. 10.1021/ct100529s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeber A. E.; Wong B. M. The importance of short- and long-range exchange on various excited state properties of DNA monomers, stacked complexes, and Watson–Crick pairs. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 2199–2209. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. A new local density functional for main-group thermochemistry, transition metal bonding, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 194101–194118. 10.1063/1.2370993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J., et al. Gaussian 09; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Culture of Animal Cells; Freshney R. I., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Strober W.Trypan Blue Exclusion Test of Cell Viability. In Current Protocols in Immunology; Wiley, 2001; pp A3–B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer M. A.; Brechtel T. M.; Davis L. E.; Parmar R. C.; Hasan M. H.; Tandon R. Inhibition of endocytic pathways impacts cytomegalovirus maturation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46069 10.1038/srep46069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.