Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have a mutual cause-and-effect relationship, and they share some common risk factors. Although numerous Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs have been developed for CVD treatment, no drugs are clinically available for AD treatment. Given the common disease-causing factors and links between the two diseases and the well-demonstrated drugs for CVD, we propose to re-examine the new potential of the existing CVD drugs as amyloid-β (Aβ) inhibitors. 3-Morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (SIN-1) is an FDA-approved drug for inhibiting platelet aggregation in CVD. Herein, we examine the inhibition activity of SIN-1 on the aggregation and toxicity of Aβ1–42 using combined experimental and computational approaches. Collective experimental data from ThT, circular dichroism, and atomic force microscopy demonstrate that SIN-1 can effectively inhibit amyloid formation at every stage of Aβ aggregation by prolonging lag phase, slowing down aggregation rate, and reducing final fibril formation. The cell viability assay also shows that SIN-1 enables the protection of SH-SY5Y cells from Aβ-induced cell toxicity. Such an inhibition effect is attributed to interference with the structural transition of Aβ toward a β-sheet structure by SIN-1. Furthermore, molecular dynamic simulations confirm that SIN-1 preferentially binds to the C-terminal β-sheet grooves of an Aβ oligomer and consequently disrupts the β-sheet structure of Aβ and Aβ–Aβ association, explaining experimental observations. This work discovers a new function of SIN-1, making it a promising compound with dual protective roles in inhibiting both platelet and Aβ aggregations against CVD and AD.

Introduction

Growing evidence indicates that cardiovascular disease (CVD) and its risk factors are often associated with the increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and its cognitive decline.1−3 Both clinical and subclinical data have shown that patients with AD have pathological amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques being found in both brain parenchymal tissues and cerebral blood vessels with adhesive or aggregated platelets.4 In the blood vessels, Aβ aggregates cause vascular dysfunction and cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which contribute to AD progression. Meanwhile, vascular damages in the brain may also contribute to the production/aggregation/deposition of Aβ, which is one of pathological hallmarks of AD.3,5−7 Parallel lines of evidence further showed that several cerebrovascular factors8 such as microvascular ischaemic lesions, periventricular white matter lesions, carotid artery wall thickness, and ankle/arm index were all closely related to Alzheimer lesions.9−11

The aggregation and accumulation of Aβ peptides in the human brain contribute to neuron cell death in AD. Development of effective drugs to prevent or delay Aβ aggregation and the associated AD progression remains a significant challenge. Currently, the conventional drug-development strategy is a very time-consuming, expensive, and laborious and tedious process. Although the exact connection between CVD and AD still remains unclear, the two diseases share some common risk factors including high blood pressure, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and even diabetes. Given these common disease-causing factors and links between two different diseases, it is possible that pharmacological intervention of one disease will also hold promise for reducing the risk of the other. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved numerous drugs for CVD treatment.12−16 These CVD drugs have demonstrated safety, biocompatibility, and blood–brain barrier (BBB) crossing and targeting abilities. To avoid reinventing the wheel, we propose to re-examine the new potential of the existing CVD drugs as Aβ inhibitors. The misfolding and aggregation of Aβ are considered to be the key pathogenic event in the onset of AD.17−19 During the early aggregation stage, Aβ forms soluble oligomers, which are the primary toxic species responsible for neuronal injury and cell death in AD. The oligomer-induced toxicity mechanisms are far more complex and still under debate, and they could link to ion-channel formation,20,21 oxidative stress,22,23 metal binding,24 and membrane receptor dysfunction.25−27 Regardless of the exact amyloid toxicity mechanisms, prevention of oligomer formation and further aggregation appears to be the first and important step toward therapeutic strategies for AD treatment. Previous research has proposed many inhibitors of different categories against Aβ aggregation, such as small organic molecules (epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG),28 curcumin,29 gallic acid,30 and polyphenols31), nanoparticles (NiPAM/BAM,32 AuNPs,33 CdTe NPs,34 and SA-GNPs35), and peptide-based inhibitors (Aβ fragments 31–42, 39–42, 16–20, and 17–2136−40 and β-sheet breaker peptides41). Most of these inhibitors have not passed large-scale clinical trials,42 and only EGCG is currently undergoing phase III clinical trials against early stages of AD.43 Different hypotheses have been proposed to explain the clinical failures of these inhibitors, including the loss of specific binding between drugs and Aβ in vivo and less efficiency at phospholipid interfaces than in bulk solution.44 The major failure possibility for these inhibitors is the low permeability to the BBB.45,46

Herein, we proposed a design strategy of Aβ aggregation inhibitors by searching potential candidates among FDA-approved CVD drugs simply because these CVD drugs have already been extensively tested for their excellent low toxicity and BBB permeability. We have simple selection criteria for potential Aβ inhibitors: the inhibitor candidates should be commercially available, demonstrate their safety through an FDA approval, have a structure similar to the existing Aβ inhibitors (e.g., EGCG) with a balance between aromatic rings and hydrophilic groups, and possess biological functions that are potentially linked to some aspects of Aβ aggregation. Among these CVD drugs, 3-morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (namely, linsidomine or SIN-1) is a widely used vasodilator for inhibiting platelet aggregation.47 Platelet activation was also found to contribute to Aβ overproduction48 and aggregation.49 Therefore, it is expected that targeting blood platelets may provide a new avenue for anti-AD therapy. As compared with other small organic molecules as Aβ inhibitors, we envision that the planar portion of SIN-1 and its aromatic ring should be able to interfere with the formation of the β-sheet structures of Aβ1–42 through intercalation and π–π interactions, thus inhibiting Aβ aggregation. To test this hypothesis, we conducted thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence, atomic force microscopy (AFM), circular dichroism (CD), cell viability assays, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to examine SIN-1-induced Aβ aggregation kinetics, fibril morphologies, secondary-structure transition, cell toxicity, and SIN-1/Aβ interactions. Our collective data showed that SIN-1 can effectively inhibit the Aβ fibrillation process by changing the fibrillogenesis pathways to form many innocuous amorphous aggregates, which in turn reduce Aβ-induced cell toxicity. MD simulations further confirmed that SIN-1 can strongly bind to C-terminal residues of Aβ, and such a binding tended to peel off the edge peptide from Aβ oligomers and thus greatly disrupted the ordered β-sheet structures of Aβ. Both computational and experimental findings not only support the inhibitory effect of SIN-1 on Aβ aggregation but also imply that SIN-1 possesses dual functions for inhibiting both platelet and Aβ aggregation in CVD and AD.

Results and Discussion

SIN-1 Inhibits Aβ42 Fibrillization and Modulates Its Structural Transition

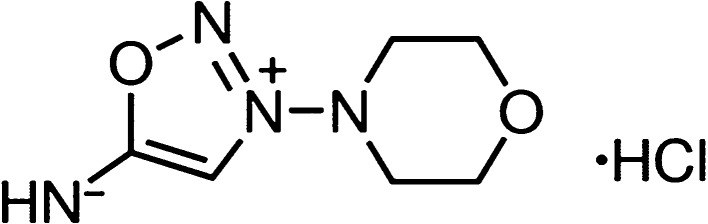

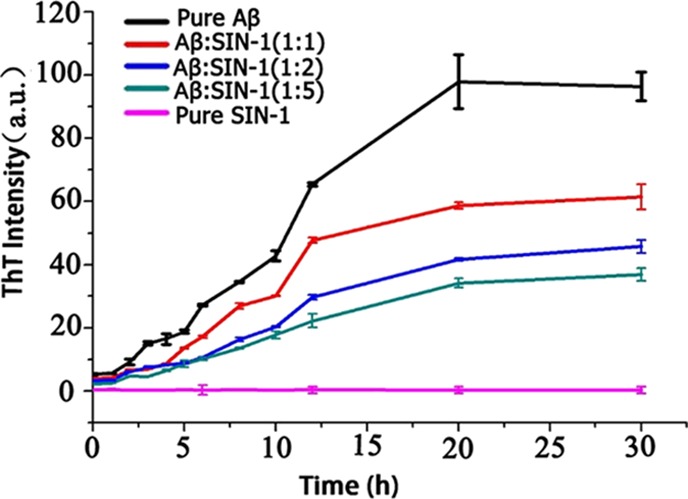

3-Morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (Scheme 1), also termed as linsidomine or SIN-1, is a vasodilator that can release NO, superoxide, and peroxynitrite under physiological conditions. It is a mesoionic heterocyclic aromatic chemical compound, with a sydonon imine group and a morpholine group connected by the nitrogen–nitrogen bond. First, ThT fluorescence assays were used to examine the ability of SIN-1 to modulate Aβ aggregation kinetics. Figure 1 shows the Aβ42 (25 μm) aggregation profiles in the absence (control) and presence of SIN-1 at different molar ratios of Aβ/SIN-1 (1:1, 1:2, and 1:5). First, pure SIN-1 did not produce any ThT signal, eliminating the possibility of aberrant interactions between SIN-1 and ThT. Second, pure Aβ aggregation showed a typical nucleation–polymerization aggregation profile, starting with a very short lag phase of ∼1 h, followed by a rapid growth from 2 to 20 h, and ending at a stable plateau after 20 h, where a final ThT fluorescence plateau reached ∼98, consistent with our previous work.50,51 When incubating the freshly prepared Aβ with SIN-1 at these three concentrations, all cases demonstrated the inhibitory effect of SIN-1 on Aβ aggregation in a dose-dependent manner. In all cases, SIN-1 imposed its inhibition on every stage of Aβ aggregation, as evidenced by the increase in lag time (∼5 h) and the decrease in aggregation rate and final fluorescence intensity (i.e., final Aβ fibril formation). SIN-1 reduced the amount of Aβ fibrils by ∼70, 65, and 40% at the molar ratios of Aβ/SIN-1 of 1:5, 1:2, and 1:1, respectively. Thus, the Aβ inhibition effect generally increased as the SIN-1 concentration increased, but when SIN-1 concentrations reached or crossed 125 μM, the Aβ inhibition effect was similar, indicating that saturation of the inhibitory effect was achieved.

Scheme 1. Structure of SIN-1.

Figure 1.

Time-dependent ThT fluorescence profiles for Aβ aggregation of 25 μM in the absence (control) and presence of SIN-1 at different molar ratios of Aβ/SIN-1 (1:1, 1:2, and 1:5). Error bars represent the average of three replicate experiments.

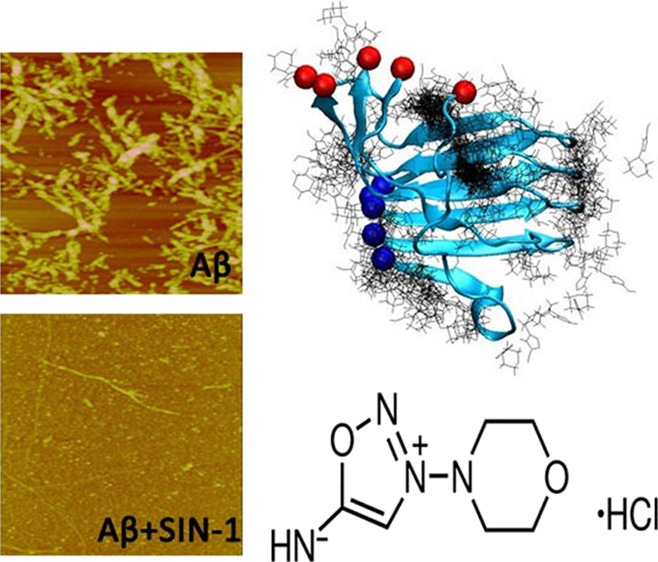

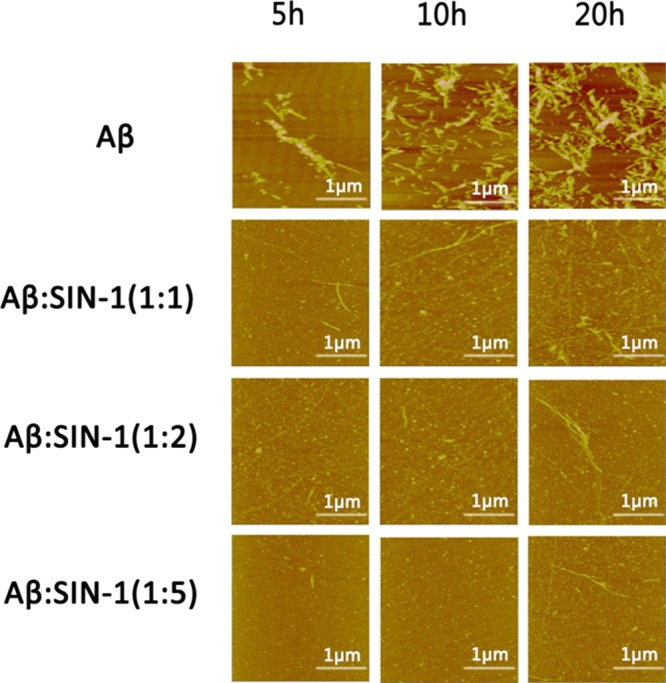

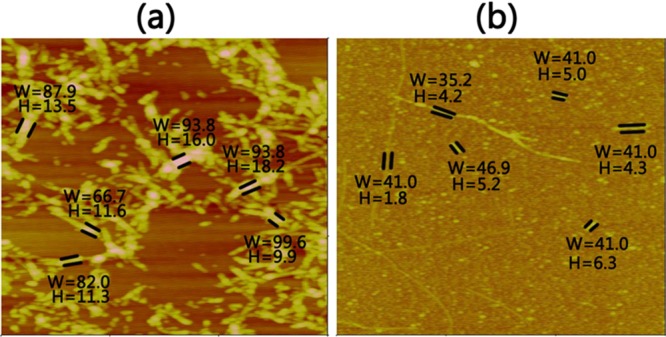

AFM and far-UV CD spectroscopy were performed in conjunction with ThT fluorescence measurements to confirm the SIN-1-induced structural transition and fibrillar inhibition of Aβ42. Figure 2 shows the AFM images during the time course of Aβ (25 μM) aggregation in the absence and presence of SIN-1 at the Aβ/SIN-1 molar ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5, respectively. As the control, pure Aβ quickly formed large, globular aggregates and short, thick protofibrils after 5 h incubation, consistent with the lag phase as shown in Figure 1. After 5 h, denser and thicker protofibrils were produced, and after 24 h, mature Aβ fibrils dominated. However, upon the addition of SIN-1 to Aβ solution, the morphologies of Aβ42 aggregates (Figure 2, second to fourth row) were dramatically different from those of pure Aβ42 (Figure 2, first row). In all cases of Aβ/SIN-1 mixtures, within 10 h, spherical aggregates with sizes of 3–5 nm were predominant, and after 20 h, only a few thin fibrils were detected. Consistent with ThT data, higher SIN-1 concentrations significantly slowed down Aβ fibrillization at the three different aggregation stages and eventually produced much less fibrils. Further AFM characterization of Aβ fibrils in the absence and presence of SIN-1 showed that the SIN-1-mediated Aβ fibrils showed the average width of 41.0 ± 1.65 nm and height of 4.5 ± 0.66 nm, which were much thinner than pure Aβ fibrils with the average width of 87.3 ± 5.25 nm and height of 13.4 ± 1.41 nm (Figure 3). This observation suggests that SIN-1 molecules incorporate Aβ oligomers to prevent them from further growing into mature fibrils.

Figure 2.

AFM images for pure Aβ peptides (25 μM) and mixed Aβ–SIN-1 at different molar ratios of Aβ/SIN-1 (1:1, 1:2, and 1:5) at 5, 10, and 20 h.

Figure 3.

Sizes of Aβ fibrils in the (a) absence and (b) presence of SIN-1 with Aβ/SIN-1 ratio of 1:5 at 20 h. W and H (nm) denote the width and height of the fibers, respectively.

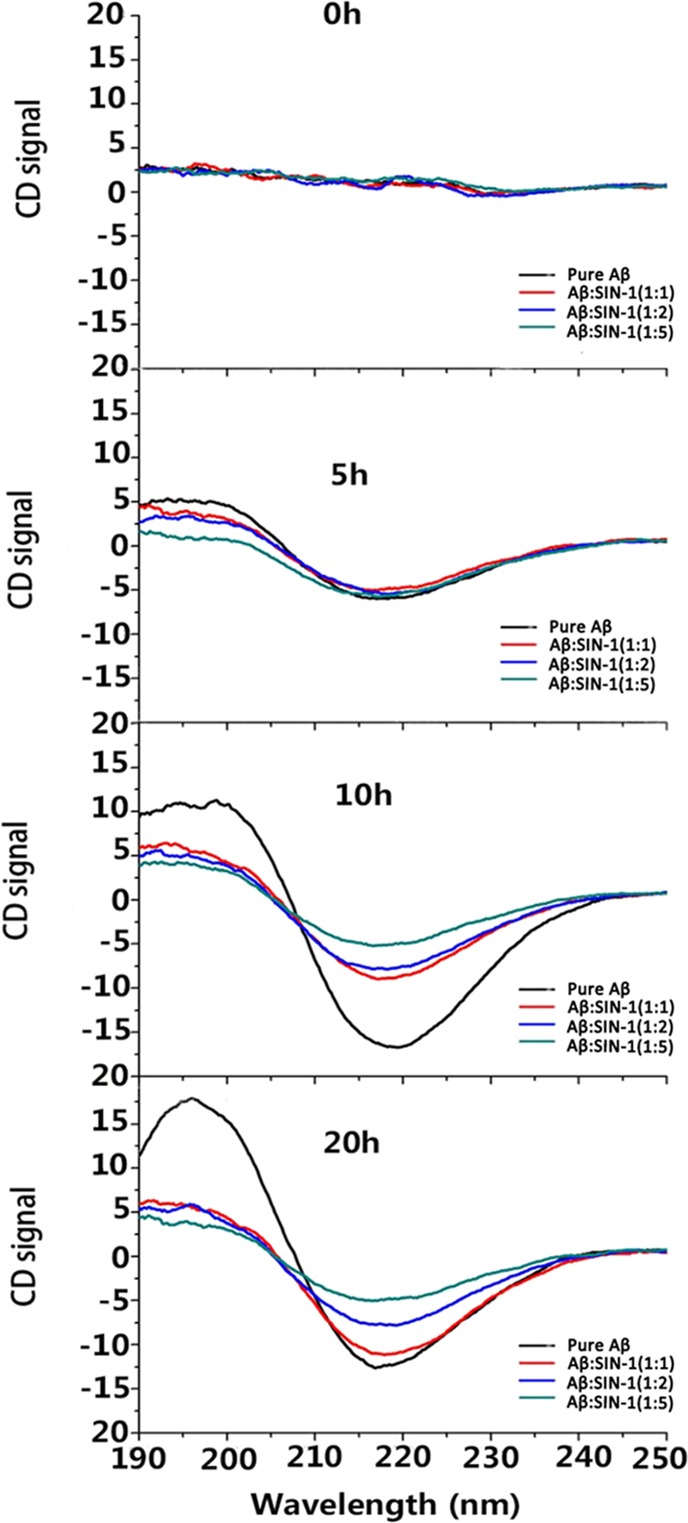

Next, we used CD spectroscopy to monitor conformational changes in Aβ solution during 20 h of incubation without and with SIN-1 at different concentrations. In Figure 4, all CD data were recorded at 0, 5, 10, and 20 h, the same time points used in ThT and AFM measurements, and such a timescale should be able to cover the lag, growth, and equilibrium phases of the entire Aβ aggregation process. In all tested samples, CD profiles did not show any characteristic peak at the beginning of incubation (i.e., 0 h), suggesting that (i) Aβ42 did not adopt any structured conformation and (ii) SIN-1 did not affect the initial conformation of Aβ42. As a control, pure Aβ peptides started to misfold into certain secondary structures at 5 h, as signified by the appearance of the two peaks at 195 and 215 nm, both of which corresponds to the β-sheet structure. As incubation increased to 10 and 20 h, these two peaks continued to increase in height, indicating that β-sheet-rich oligomers and fibrils were produced. The final secondary structure content of pure Aβ at 20 h was 55% of β-sheet, 25% of α-helix, and 20% of random coils, respectively, indicating that pure Aβ experiences a typical structural transition from the initial random coil to the β-sheet structure.50 In contrast to pure Aβ aggregation, addition of SIN-1 molecules into Aβ greatly interfered with the structural transition of Aβ to the β-sheet-rich structure. During 20 h of incubation, all sample mixtures presented only a single peak at 215 nm, without observing any peak at 195 nm. Moreover, the peak heights at 215 nm were greatly reduced by ∼39 and 60% at Aβ/SIN-1 = 1:2 and 1:5, respectively. So, the final β-sheet contents for Aβ with SIN-1 at the molar ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5 were reduced to 33, 30, and 28%, respectively. CD data are again consistent with ThT and AFM results, confirming that SIN-1 is effective in inhibiting Aβ fibrillation by preventing its structural transition toward the β-sheet structures.

Figure 4.

Time-dependent far-UV CD spectra for pure Aβ at 25 μM and mixed Aβ–SIN-1 at different molar ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5 during 20 h of aggregation.

SIN-1 Reduced Aβ42-Induced Cytotoxicity

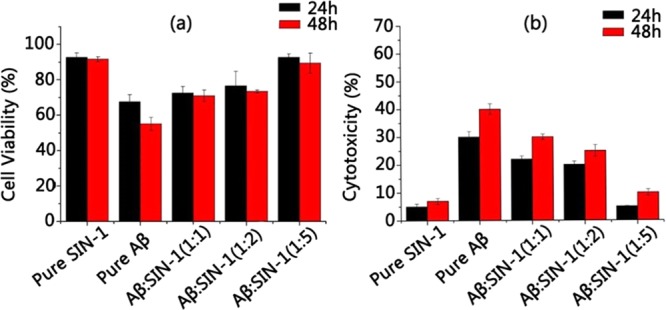

We further investigated whether SIN-1 can also protect neuronal cells from Aβ-induced toxicity using both 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Figure 5a) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay (Figure 5b) with SH-SY5Y cell lines. To set up a baseline, absorbance of the cell media containing SH-SY5Y cells was measured, and the value was regarded as 100% of cells being viable. Then, two control experiments were conducted: pure SIN-1 (125 μm) presented very low cytotoxicity to cells, as evidenced by ∼92% cell viability during 48 h of cell culture using MTT assay and ∼7% cell apoptosis using LDH assay. SIN-1 is a precursor of vincristine whose side effects have been noted in cancer chemotherapy. As a control, pure Aβ42 (25 μM) presented high toxicity to the cells. MTT assay showed that Aβ-induced cell viability was greatly reduced to 69% at 24 h and 57% at 48 h (Figure 5a). Consistently, LDH assay showed that the Aβ-induced apoptosis rate was increased to 30% at 24 h and 43% at 48 h (Figure 5b). However, when Aβ (25 μM) was coincubated with SIN-1 in the cultured cell media for 24 h, the cell viability was 72, 75, and 93% at Aβ/SIN-1 ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5, all of which were higher than 69% of cell viability induced by Aβ alone. Consistent with MTT results, cell apoptosis was 22, 20, and 5% at Aβ/SIN-1 ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5, respectively, all of which were much lower than 30% of cell apoptosis induced by Aβ alone. Further increase in incubation time to 48 h led to minor decreases in cell viability (70, 72, and 90% at 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5 Aβ/SIN-1 ratios, respectively) and minor increases in cell apoptosis (30, 25, and 10% at 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5 Aβ/SIN-1 ratios, respectively), suggesting that SIN-1 can retain its long-term neuroprotection against Aβ-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. In line with the data from aggregation kinetics (ThT, Figure 1) and structural characterizations (AFM and CD, Figures 2–34), Aβ/SIN-1 mixtures at 1:5 molar ratio provide the best cell protection effects from Aβ-induced toxicity.

Figure 5.

(a) MTT assay for cell viability and (b) LDH assay for cell apoptosis in the presence of pure Aβ peptide and Aβ–SIN-1 mixtures at Aβ/SIN-1 molar ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:5 after 24 and 48 h incubation.

Binding Modes of SIN-1 to Aβ Oligomers

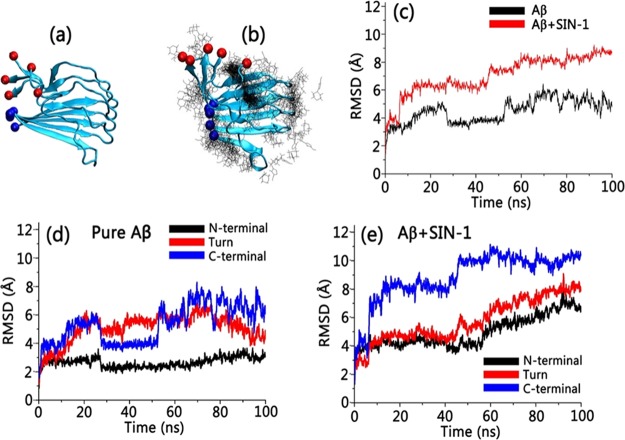

To better understand the underlying Aβ inhibition mechanism by SIN-1, we performed all-atom MD simulations to study the interactions between SIN-1 molecules and an Aβ42 pentamer. The Aβ42 pentamer was selected as a binding target simply because Aβ42 pentamers are one of the most abundant soluble oligomers and their toxicity is one of the highest.52−54 Two independent 100 ns MD simulations were conducted to study the interaction of Aβ42 pentamers with and without SIN-1 molecules in explicit solvent environments. For the Aβ/SIN-1 system, 10 SIN-1 molecules were randomly placed around the Aβ pentamer at the beginning of MD simulations, with a separation distance to ensure no initial interactions between SIN-1 and Aβ. The initial Aβ pentamer adopts a U-bend conformation with both N- and C-terminal β-strands being well-packed together in a register way. Figure 6a,b shows the final snapshot for pure Aβ42 pentamer alone and Aβ42 pentamer in the presence of SIN-1 molecules. A visual inspection clearly showed that upon SIN-1 binding to Aβ pentamers, the Aβ pentamer essentially lost its initial structural integrity, particularly its β-sheet structure. The comparison of root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) profiles of Aβ pentamers in the absence and presence of SIN-1 also confirmed the SIN-1-induced structural instability of Aβ pentamers. Without SIN-1, Aβ pentamers exhibited very high structural stability, with the RMSD values fluctuating around ∼4.6 Å (Figure 6c). The parallel in-register β-strands and the U-shaped peptide topology in Aβ pentamers were well-maintained, with a typical twist between adjacent β-strands. However, when SIN-1 bound to the Aβ pentamer, the parallel, in-registered β-sheets of Aβ pentamers were disrupted greatly, as evidenced by the large and continuously increased RMSD values (∼8.8 Å). We also calculated RMSD values for three different domains of C-terminal β-sheet, U-turn, and N-terminal β-sheet for both pure Aβ pentamer and Aβ/SIN-1 systems. It can be clearly seen that for pure Aβ pentamer, N-terminal β-sheet region had smaller RMSD values than C-terminal β-sheet region and U-turn regions, indicating that the N-terminal β-sheet region is more stable than the other two regions (Figure 6d). However, when SIN-1 molecules were introduced to an Aβ pentamer, strong SIN-1/Aβ interactions disrupted the structural integrity of Aβ, leading to larger RMSD values in all three regions. Particularly, C-terminal β-sheet region suffered from the larger SIN-1-induced structural deviation (Figure 6e).

Figure 6.

MD snapshots of (a) pure Aβ pentamer and (b) Aβ pentamer with preferential binding distribution of SIN-1. Red and blue balls indicate the C-terminus and N-terminus of Aβ in (a) and (b), respectively. (c) Time-dependent RMSD profiles for pure Aβ pentamer (black line) and Aβ pentamer with SIN-1 (red line). Time-dependent RMSD profiles for C-terminal β-sheet, U-turn, and N-terminal β-sheet of Aβ (d) without SIN-1 and (e) with SIN-1.

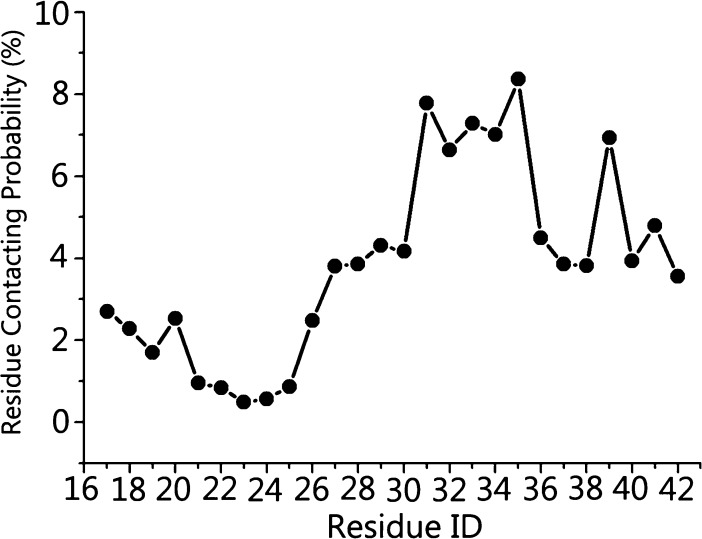

In Figure 6b, SIN-1 shows some preferential binding positions around Aβ pentamers. To better identify the possible binding sites of Aβ pentamers by SIN-1, we calculated the averaged contact probabilities between each Aβ residue and SIN-1 (Figure 7), where a residue contact is defined as a residue within 6.5 Å of SIN-1 molecules. Heterogeneous contact probability between SIN-1 and Aβ residues clearly indicates that SIN-1 has more favorable interactions with C-terminal residues (Ile31–Ala42) than with N-terminal residues (Leu17-Val24). Using 5% of contact probability as a threshold value, SIN-1 exhibited strong preferential interactions with isoleucine31 (7.7%), isoleucine32 (6.6%), glycine33 (7.2%), leucine34 (7.0%), methionine35 (8.3%), and valine39 (6.9%), and most of these residues were hydrophobic residues initially located in the C-terminal β-strand region. Such a strong binding not only peels off the C-terminal strand of chain A from the Aβ pentamer but also folds the extended β-strand conformation into the disordered one. Ile31–Met35 residues in the middle of C-terminal β-sheet form a wide hydrophobic groove, which acts as a basic motif for amyloid growth via either monomer attachment for elongation or lateral stacking. Thus, disruption of this β-sheet region via strong SIN-1 binding enables the prevention of the lateral association of Aβ aggregates and thus inhibition of the fibril growth. Simulation results confirm the inhibitory capacity of SIN-1 on Aβ aggregation through experiments.

Figure 7.

Residue contacting probability of SIN-1 molecules toward Aβ peptides.

Conclusions

Growing evidence supports a likely causal link between CVD and AD. Although there are no clinically approved inhibitors of Aβ amyloidosis, we proposed a design strategy of Aβ aggregation inhibitors by searching potential candidates among FDA-approved drugs for CVD simply because these CVD drugs have already been extensively tested for their excellent low toxicity and BBB permeability. We selected and tested the inhibition effects of SIN-1 on Aβ aggregations and Aβ-induced cytotoxicity by combining experimental and computational approaches. Collective experimental data confirmed that SIN-1 can effectively inhibit Aβ misfolding and aggregation at different stages of aggregation and reduce Aβ-induced cell toxicity in a dose-dependent manner. The SIN-1-induced Aβ inhibition effect increased as the SIN-1 concentration increased. At Aβ/SIN-1 molar ratio of 1:5, SIN-1 reduced Aβ fibril formation by 70% and Aβ-induced cell toxicity by 35%. Computationally, MD simulations support our biophysical measurements and provide insights into SIN-1/Aβ interaction at the molecular level. SIN-1 shows a strong tendency to bind and disrupt the C-terminal β-sheet of Aβ, specifically hydrophobic residues of I31–M35. Therefore, disruption of this β-sheet region via a strong SIN-1 binding enables the prevention of the lateral association of Aβ aggregates and thus inhibition of the fibril growth, explaining the experimentally observed inhibition effect of SIN-1. This work not only demonstrates a new function of SIN-1 as an Aβ inhibitor but also hint that pharmacological interventions of CVD may also hold promise for reducing the risk of AD.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Aβ peptides (Aβ1–42) with more than 95% purity were purchased from Bachem AG (Bubendorf Switzerland). 3-Moropholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (SIN-1) with purity 98%, 10 mM phosphate-bufferedsaline (PBS) buffer (pH = 7.4), 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) with purity ≥ 99.9%, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with purity ≥ 99.9%, and ThT with more than 98% purity were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). A human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line and Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). All chemicals used in this work were of analytical grade.

Peptide Preparation

Aβ1–42 peptide was stored at −20 °C immediately after arrival, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The Aβ1–42 peptide monomer was prepared by dissolving 1.0 mg of the prepackaged peptide into 1 mL of HFIP (1 mg/mL) followed by 30 min of ultrasonic treatment and 30 min of centrifugation at 14 000 rpm and 4 °C to remove the pre-existing aggregates and seeds. Eighty percentage of the supernatant was extracted, subpackaged, frozen in the refrigerator at −80 °C, and then lyophilized using freeze dryer. DMSO (30 μL) was used to dissolve 0.2 mg of the subpackaged Aβ peptide. The aggregation of the Aβ (25 μM) peptide was induced by mixing 30 μL of DMSO–Aβ solution with 2 mL of PBS buffer of 10 mM.

ThT Fluorescence Assay

ThT powder (0.033 g) was first dissolved into 50 mL of DI water to a concentration of 2 mM and then stored in dark place at room temperature. The stock solution was then diluted in Tris-buffer to the concentration of 10 μM. The ThT assay was performed by mixing 60 μL of Aβ1–42/SIN-1/Aβ1–42-3MH solutions with 3 mL of 10 μM ThT–Tris solution. An LS-55 fluorescence spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Waltham, MA) was used to obtain the fluorescence spectra. An excitation wavelength of 450 nm was applied, and the emission wavelengths were recorded between 470 and 500 nm. All of the ThT fluorescence experiments were repeated at least three times.

CD Spectroscopy

CD spectroscopy with a J-1500 spectropolarimeter (Jasco Inc, Japan) using a continuous scanning mode at room temperature was applied to measure the conformation changes associated with fibril formation. Solutions (150 μL each) of Aβ1–42/SIN-1/Aβ1–42–SIN-1 that were incubated for 0, 5, 10, and 20 h were individually extracted and placed in a 1 mm quartz cuvette for measurements. The spectra were scanned between 190 and 250 nm at a 0.5 nm resolution and 50 nm/min scan rate. The obtained spectra were corrected by subtracting only the buffer and/or the absorbance from SIN-1 without Aβ1–42. The secondary structure contents were calculated from the CD spectra using the self-consistent method (CDSSTR program) in the CDPro analysis software.

Tapping-Mode AFM

The morphology changes in Aβ1–42 peptides mediated by SIN-1 molecules at different incubation periods over 20 h were evaluated using a Nanoscope III multimode scanning probe microscope (Veeco Corp., Santa Barbara, CA). Aliquots (20 μL) from each incubated sample at different time points was deposited on a piece of freshly cleaved mica for 1 min, rinsed three times with 50 mL of DI water to remove salts and loosely bound peptides, dried using compressed air for 5 min, and imaged using AFM. All images were recorded at the 512 × 512 pixel resolution at a typical scan rate of 1.0–2.0 Hz and the vertical tip oscillation frequency of 250–350 kHz. At least six different locations on the mica surface were scanned and recorded. The representative images were selected for comparisons.

Cell Culture

SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were cultured in the medium prepared by mixing the sterile-filtered EMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cells were cultured in a T75 flask until they covered the available surface area. Before carrying out the MTT experiment, the cells were harvested using 3 mL of trypsin and then resuspended in 7 mL of PBS. The cells were then plated in a 96-well cell culture plate with a density of 104 cells per well.

MTT Assay

Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. SH-SY5Y cells were incubated in a 96-well plate at 37 °C with a density of 104 cells per well. After removing the medium, the cells were washed using PBS two times. Then, Aβ1–42, SIN-1, and Aβ1–42–SIN-1 solutions were individually added into the wells, which were then incubated for another 24 and 48 h. In the procedure of MTT assay, the culture medium was removed followed by adding 100 μL of a fresh medium and 20 μL of the MTT solution (5 mg/mL) and incubated for 4 h. After that, the culture medium was removed, and the formazan crystals were dissolved in 150 μL of DMSO. The absorbance intensity was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad 680, USA) at the wavelength of 570 nm. All experiments were performed in sextuplicate, and the relative cell viability was normalized by the control (cells cultured alone).

LDH Assay

Neuronal apoptosis induced by Aβ and mediated by SIN-1 was quantitatively assessed using the LDH release assay. SH-SY5Y cells were incubated in a 96-well plate at 37 °C for 24 h with a density of 104 cells per well. After replacing the culture medium with an FBS-free medium, 10 μL of Aβ, SIN-1, and Aβ/SIN-1 solutions were added into different wells. For the spontaneous LDH activity control group, 10 μL of sterile and ultrapure water was added into the wells. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 and 48 h. Before the assay, 10 μL of lysis buffer (10×) was added to the maximum LDH activity control group for an additional incubation of 45 min. Extracellular LDH leakage was evaluated using the assay kit (Thermo, USA). The absorbance intensity was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad 680, USA) at the wavelength of 490 and 680 nm. All experiments were performed in sextuplicate.

MD Simulation

The initial structure of Aβ pentamers was obtained from the protein data bank (PDBID: 2BEG). The coordinate of SIN-1 molecules was generated using the GaussView program, whose force fields were developed in a CHARMM-CGenFF compatible manner.55 Each system was solvated in the explicit solvent box with a minimal margin of 15 Å from any edge of water box to any solute atom. The simulated systems were neutralized and mimicked ∼150 mM ion strength using Na+ and Cl– ions. The simulations were conducted with the NAMD program using the CHARMM27 force field. Langevin method was used to maintain the temperature of 300 K and pressure of 1 atm in the NPT simulation systems. Long- and short-range nonbond interactions were described using the force-shifted method with 14 Å cutoff and the switch method with 12 and 14 Å cutoffs. The trajectories were saved every 2 ps for the analysis. All analyses were performed using the CHARMM scripts, VMD, and in-house Tcl codes.

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the NSF (CBET-1510099), the Alzheimer Association New Investigator Research Grant (2015-NIRG-341372), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC-21528601) and partially by the NSF (DMR-1607475).

Author Contributions

B.R., M.Z., R.H., H.C., G.L., and J.Z. carried out experiments and simulations. All authors designed experiments and simulations, interpreted the results, and prepared the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- de la Torre J. C.; Royall D. R. Alzheimer disease as a vascular disorder: Nosological evidence—Response. Stroke 2002, 33, 2147–2148. 10.1161/01.str.0000028987.97497.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick P. B. Risk factors for vascular dementia and Alzheimer disease. Stroke 2004, 35, 2620–2622. 10.1161/01.str.0000143318.70292.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaria R. N.; Akinyemi R.; Ihara M. Does vascular pathology contribute to Alzheimer changes?. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 322, 141–147. 10.1016/j.jns.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner L.; Fälker K.; Gremer L.; Klinker S.; Pagani G.; Ljungberg L. U.; Lothmann K.; Rizzi F.; Schaller M.; Gohlke H.; Willbold D.; Grenegard M.; Elvers M. Platelets contribute to amyloid-β aggregation in cerebral vessels through integrin αIIbβ3-induced outside-in signaling and clusterin release. Sci. Signaling 2016, 9, ra52. 10.1126/scisignal.aaf6240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. Toward a comprehensive theory for Alzheimer’s disease. Hypothesis: Alzheimer’s disease is caused by the cerebral accumulation and cytotoxicity of amyloid β-protein. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 924, 17–25. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawuenyega K. G.; Sigurdson W.; Ovod V.; Munsell L.; Kasten T.; Morris J. C.; Yarasheski K. E.; Bateman R. J. Decreased clearance of CNS β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science 2010, 330, 1774. 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre J. C. Critically attained threshold of cerebral hypoperfusion: The CATCH hypothesis of Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 331–342. 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaria R. N.; Ballard C. Overlap between pathology of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 1999, 13, S115–S123. 10.1097/00002093-199912003-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiso J.; Tomidokoro Y.; Revesz T.; Frangione B.; Rostagno A. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. Hirosaki igaku 2010, 61, S111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W. R.; Moody D. M.; Thore C. R.; Challa V. R. Cerebrovascular pathology in Alzheimer’s disease and leukoaraiosis. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 903, 39–45. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst E.; Ribeiro H. M.; Molyneux A.; Budge M.; Smith A. D. Plasma homocysteine levels, cerebrovascular risk factors, and cerebral white matter changes (leukoaraiosis) in patients with Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2002, 59, 787–793. 10.1001/archneur.59.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating G. M. Cangrelor: A review in percutaneous coronary intervention. Drugs 2015, 75, 1425–1434. 10.1007/s40265-015-0445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankyo D.US FDA Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee makes recommendation on Daiichi Sankyo’s once-daily Savaysa (edoxaban) for the reduction in risk of stroke and systemic embolic events in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, Oct 2014. (press release). [Google Scholar]

- Blair H. A.; Dhillon S. Omega-3 carboxylic acids (Epanova): A review of its use in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2014, 14, 393–400. 10.1007/s40256-014-0090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl P.; Bode C.; Duerschmied D. Clinical potential of vorapaxar in cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with atherosclerosis. Ther. Clin. Risk Manage. 2015, 11, 1133. 10.2147/tcrm.s55469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari S. H.; Reynolds M. R.; Kadkhodayan Y.; Cross D. T.; Moran C. J. Hemorrhagic complications after prasugrel (Effient) therapy for vascular neurointerventional procedures. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2012, 5, 337–343. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea J.-E.; Urbanc B. Insights into Aβ aggregation: A molecular dynamics perspective. Curr. Trends Med. Chem. 2013, 12, 2596–2610. 10.2174/1568026611212220012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Qian Z.; Wei G. The inhibitory mechanism of a fullerene derivative against amyloid-β peptide aggregation: An atomistic simulation study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 12582–12591. 10.1039/C6CP01014H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Yu X.; Li L.; Zheng J. Inhibition of amyloid-β aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 1223–1243. 10.2174/13816128113199990068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmrich V.; Grimm C.; Draguhn A.; Barghorn S.; Lehmann A.; Schoemaker H.; Hillen H.; Gross G.; Ebert U.; Bruehl C. Amyloid β oligomers (Aβ1–42 globulomer) suppress spontaneous synaptic activity by inhibition of P/Q-type calcium currents. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 788–797. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4771-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara M.; Kuroda Y. Molecular mechanism of neurodegeneration induced by Alzheimer’s β-amyloid protein: Channel formation and disruption of calcium homeostasis. Brain Res. Bull. 2000, 53, 389–397. 10.1016/S0361-9230(00)00370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice F. G.; Velasco P. T.; Lambert M. P.; Viola K.; Fernandez S. J.; Ferreira S. T.; Klein W. L. Aβ Oligomers Induce Neuronal Oxidative Stress through an N-Methyl-d-aspartate Receptor-Dependent Mechanism that is Blocked by the Alzheimer Drug Memantine. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11590–11601. 10.1074/jbc.m607483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G. M.; Bloodgood B. L.; Townsend M.; Walsh D. M.; Selkoe D. J.; Sabatini B. L. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-β protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2866–2875. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drago D.; Bolognin S.; Zatta P. Role of metal ions in the Aβ oligomerization in Alzheimer’s disease and in other neurological disorders. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2008, 5, 500–507. 10.2174/156720508786898479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science 2002, 298, 789–791. 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerelius C.; Johansson J.; Sandegren A. Amyloid β-peptide aggregation. What does it result in and how can it be prevented?. Front. Biosci., Landmark Ed. 2009, 14, 1716–1729. 10.2741/3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N.; Matsubara E.; Maeda S.; Minagawa H.; Takashima A.; Maruyama W.; Michikawa M.; Yanagisawa K. A Ganglioside-induced Toxic Soluble Aβ Assembly: Its Enhanced Formation from Aβbearing the Arctic Mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 2646–2655. 10.1074/jbc.M606202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyung S.-J.; DeToma A. S.; Brender J. R.; Lee S.; Vivekanandan S.; Kochi A.; Choi J.-S.; Ramamoorthy A.; Ruotolo B. T.; Lim M. H. Insights into antiamyloidogenic properties of the green tea extract (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate toward metal-associated amyloid-β species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 3743–3748. 10.1073/pnas.1220326110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Browne A.; Child D.; Tanzi R. E. Curcumin decreases amyloid-β peptide levels by attenuating the maturation of amyloid-β precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 28472–28480. 10.1074/jbc.M110.133520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Pukala T. L.; Musgrave I. F.; Williams D. M.; Dehle F. C.; Carver J. A. Gallic acid is the major component of grape seed extract that inhibits amyloid fibril formation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 6336–6340. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porat Y.; Abramowitz A.; Gazit E. Inhibition of amyloid fibril formation by polyphenols: Structural similarity and aromatic interactions as a common inhibition mechanism. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2006, 67, 27–37. 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabaleiro-Lago C.; Quinlan-Pluck F.; Lynch I.; Lindman S.; Minogue A. M.; Thulin E.; Walsh D. M.; Dawson K. A.; Linse S. Inhibition of amyloid β protein fibrillation by polymeric nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 15437–15443. 10.1021/ja8041806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan M. J.; Bastus N. G.; Amigo R.; Grillo-Bosch D.; Araya E.; Turiel A.; Labarta A.; Giralt E.; Puntes V. F. Nanoparticle-mediated local and remote manipulation of protein aggregation. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 110–115. 10.1021/nl0516862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S. I.; Yang M.; Brender J. R.; Subramanian V.; Sun K.; Joo N. E.; Jeong S.-H.; Ramamoorthy A.; Kotov N. A. Inhibition of amyloid peptide fibrillation by inorganic nanoparticles: Functional similarities with proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 5110–5115. 10.1002/anie.201007824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Liu D.; Wang Z. Resonance light scattering as a powerful tool for sensitive detection of β-amyloid peptide by gold nanoparticle probes. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 9339–9341. 10.1039/c1cc12939b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradinger E. A.; Monien B. H.; Urbanc B.; Lomakin A.; Tan M.; Li H.; Spring S. M.; Condron M. M.; Cruz L.; Xie C.-W.; Benedek G. B.; Bitan G. C-terminal peptides coassemble into Aβ42 oligomers and protect neurons against Aβ42-induced neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 14175–14180. 10.1073/pnas.0807163105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciarretta K. L.; Gordon D. J.; Meredith S. C. Peptide-based inhibitors of amyloid assembly. Methods Enzymol. 2006, 413, 273–312. 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairo C. W.; Strzelec A.; Murphy R. M.; Kiessling L. L. Affinity-based inhibition of β-amyloid toxicity. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 8620–8629. 10.1021/bi0156254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjernberg L. O.; Näslund J.; Lindqvist F.; Johansson J.; Karlström A. R.; Thyberg J.; Terenius L.; Nordstedt C. Arrest of β-amyloid fibril formation by a pentapeptide ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 8545–8548. 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C.; Sigurdsson E. M.; Morelli L.; Kumar R. A.; Castaño E. M.; Frangione B. β-sheet breaker peptides inhibit fibrillogenesis in a rat brain model of amyloidosis: Implications for Alzheimer’s therapy. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 822–826. 10.1038/nm0798-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Liang G.; Zhang M.; Zhao J.; Patel K.; Yu X.; Zhao C.; Ding B.; Zhang G.; Zhou F.; Zheng J. De novo design of self-assembled hexapeptides as β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide inhibitors. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 972–981. 10.1021/cn500165s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangialasche F.; Solomon A.; Winblad B.; Mecocci P.; Kivipelto M. Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical trials and drug development. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 702–716. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mähler A.; Mandel S.; Lorenz M.; Ruegg U.; Wanker E. E.; Boschmann M.; Paul F. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate: A useful, effective and safe clinical approach for targeted prevention and individualised treatment of neurological diseases?. EPMA J. 2013, 4, 5. 10.1186/1878-5085-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel M. F. M.; vandenAkker C. C.; Schleeger M.; Velikov K. P.; Koenderink G. H.; Bonn M. The polyphenol EGCG inhibits amyloid formation less efficiently at phospholipid interfaces than in bulk solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14781–14788. 10.1021/ja3031664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-J.; Zhou H.-D.; Zhou X.-F. Clearance of amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease: Progress, problems and perspectives. Drug Discovery Today 2006, 11, 931–938. 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen J.-T.; Yamani A.; Kiso Y. Views on amyloid hypothesis and secretase inhibitors for treating Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 4295–4312. 10.2174/138161206778792976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiecker M.; Darius H.; Meyer J. Synergistic platelet antiaggregatory effects of the adenylate cyclase activator iloprost and the guanylate cyclase activating agent SIN-1 in vivo. Thromb. Res. 1993, 70, 405–415. 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90082-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Huang W.; Jing F. Contribution of blood platelets to vascular pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Blood Med. 2013, 4, 141. 10.2147/JBM.S45071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini L.; Becherini L.; Benvenuti S.; Brandi M. Bioeffects of a nitric oxide donor in a human preosteoclastic cell line. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Res. 1996, 17, 93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B.; Jiang B.; Hu R.; Zhang M.; Chen H.; Ma J.; Sun Y.; Jia L.; Zheng J. HP-β-cyclodextrin as an inhibitor of amyloid-β aggregation and toxicity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 20476–20485. 10.1039/C6CP03582E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R.; Zhang M.; Chen H.; Jiang B.; Zheng J. Cross-seeding interaction between β-amyloid and human islet amyloid polypeptide. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 1759–1768. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M.; Davis J.; Aucoin D.; Sato T.; Ahuja S.; Aimoto S.; Elliott J. I.; Van Nostrand W. E.; Smith S. O. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-β1–42 oligomers to fibrils. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 561–567. 10.1038/nsmb.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K.; Condron M. M.; Teplow D. B. Structure-neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid β-protein oligomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 14745–14750. 10.1073/pnas.0905127106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc B.; Cruz L.; Yun S.; Buldyrev S. V.; Bitan G.; Teplow D. B.; Stanley H. E. In silico study of amyloid β-protein folding and oligomerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 17345–17350. 10.1073/pnas.0408153101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanommeslaeghe K.; Hatcher E.; Acharya C.; Kundu S.; Zhong S.; Shim J.; Darian E.; Guvench O.; Lopes P.; Vorobyov I.; Mackerell A. D. Jr. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 671–690. 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]