Abstract

Transfection with in vitro transcribed mRNAs is a safe and effective tool to convert somatic cells to any cell type of interest. One caveat of mRNA transfection is that mRNAs are recognized by multiple RNA-sensing toll like receptors (TLRs). These TLRs can both promote and inhibit cellular reprogramming. We demonstrated that mRNA transfection stimulated TLR3 and TLR7 and induced cytotoxicity and IFN-β expression in human and mouse fibroblasts. Furthermore, mRNA transfection induced paracrine inhibition of repeated mRNA transfection through type I IFNs. Modified mRNAs (mmRNAs) containing pseudouridine and 5-methycytosine reduced TLR stimulation, cytotoxicity and IFN-β expression in fibroblasts. Repeated liposomal transfection with MyoD mmRNAs significantly enhanced myogenic conversion of human and mouse fibroblasts compared with repeated transfection with MyoD mRNAs. Interestingly, electroporation of mRNAs and mmRNAs completely abrogated cytotoxicity and IFN-β expression and also abolished myogenic conversion of fibroblasts. At a low concentration, TLR7/8 agonist R848 enhanced MyoD mmRNA-driven conversion of human fibroblasts into skeletal muscle cells, whereas high concentrations of R848 inhibited myogenic conversion of fibroblasts. Our study suggests that deliberate control of TLR signaling is a key factor in the success of mRNA-driven cellular reprogramming.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor, reprogramming, transdifferentiation, mRNA, transfection, Interferon

1. Introduction

Repeated transfection with in vitro-transcribed (IVT) mRNAs encoding defined factors induced direct reprogramming of human somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) as efficiently as viral transduction [1]. Furthermore, repeated transfection with mRNAs encoding cell fate-determining factors could directly convert mouse and human fibroblasts into many different types of cells, including mouse myoblast-like cells [1], mouse neuronal stem cells [2], mouse cardiomyocytes [3] and human hepatocyte-like cells [4].

Viral RNAs and synthetic analogs can stimulate endosomal toll-like receptors (TLRs), e.g., TLR3, TLR7 and TLR8, and cytoplasmic RNA-sensing pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and induce expression of type I interferon (IFN) (e.g., IFN-α and IFN-β) and cell death in various human and mouse cells [5–7]. The type I IFNs are anti-infectious cytokines that regulate the growth of infected cells by the inhibition of mRNA translation and cell proliferation [8].

Transfection with IVT mRNAs also stimulates RNA-sensing TLRs and PRRs, resulting in the induction of inflammatory response, cytotoxicity and type I IFN expression [9, 10]. RNA-driven cytotoxicity and inflammatory response are one of the major obstacles to mRNA-driven reprogramming of cells [1, 9, 11]. To overcome this problem, modified nucleosides such as pseudouridine (ψU) and 5-methylcytosine (5mC) were incorporated into IVT mRNAs and these modified IVT mRNAs (called mmRNAs) ablated activation of RNA-sensing TLRs and PRRs [1, 12, 13]. On the other hand, TLR-mediated inflammatory responses are required for the successful reprogramming of cells [14, 15]. Supplementation with TLR3 agonist polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (polyI:C) enhanced mmRNA-driven reprogramming of human fibroblasts into iPSCs [1]. Thus, TLR and PRR are simultaneously necessary and inhibitory for mRNA-driven reprogramming of cells. Therefore, it is critical to develop an optimal method to deliberately control activation of TLRs and PRRs and improve mmRNA-driven reprogramming of cells.

In the current study, we compared mRNA- and mmRNA-induced cytotoxicity and IFN-β expression between human and mouse fibroblasts and determined improved methods to deliver mRNA, modulate inflammatory responses and cytotoxicity and enhance mRNA-driven cellular reprogramming.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Generation of MyoD, GFP and actin mRNAs and mmRNAs

Mouse and human MyoD1, mouse actin and green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNAs were cloned into the transcription vector pSP73-Sph/A64. Generation of IVT mRNAs was conducted as described previously [16]. Briefly, plasmids were linearized with SpeI and in vitro transcribed using the MEGAscript® kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). The transcription reaction mixture contained 6 mM 3´−0-Me-m7G(5’)ppp(5’)G ARCA Cap analog (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), 7.5 mM ATP, 7.5 mM CTP, 7.5 mM UTP, 1.5 mM GTP, T7 polymerase, reaction buffer (all supplied by the kit) and 48 μg/ml linear DNAs. To generate mmRNAs, 5mC triphosphate and ψU triphosphate (TriLink Biotechnologies, San Diego, CA) replaced CTP and UTP in the reaction mixture. Reactions were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C. IVT mRNAs were treated with DNase I for digestion of the template DNAs, followed by polyadenylation of RNA using a Poly(A) tailing kit (Ambion). To avoid the activation of innate immune responses by RIG-I and PKR, the IVT mRNAs were treated with Antarctic Phosphatase (New England Biolabs) to remove residual 5′-triphosphates, and then the mRNAs were purified using the NucleoSpin® RNA Clean-up kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL, Bethlehem, PA).

2.2. Cell culture

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and human lung fibroblasts (hLF) (Lonza, Allendale, NJ) were grown in DMEM with 15% heat-inactivated FBS. Human neonatal dermal fibroblasts (hDF) (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) were grown in Medium 106 with Low Serum Growth Supplement (Invitrogen). The cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

2.3. mRNA transfection and myogenic conversion

Human and mouse cells (1.25 × 104 cells/cm2) were incubated overnight in a multi-well flat bottom plate (Corning, Tewksbury, MA). The cells were transfected with the IVT mRNAs using DharmaFECT® Duo Transfection Reagent (Thermo Scientific) or Electro Square Porator ECM 830 (BTX, San Diego, CA) as described previously [17]. Briefly, DharmaFECT were mixed in OPTI-MEM I (Invitrogen) at a RNA:DharmaFECT:OPTI-MEMα ratio of 100 ng:0.4 μl:10 μl. This mixture was incubated for 15 min at room temperature. 250 ng of the IVT RNA per 1 × 104 cells were directly added to each well of a multi-well plate. After a 5-hour incubation, culture supernatant was aspirated and fresh cell culture media was added. For electroporation, 1×105 cells suspended in 100 μl Opti-MEM I were mixed with either 2.5 μg of IVT RNAs in 2-mm cuvettes and were electroporated at 340 V for 500 μs. Cells were mixed with 2.15 ml of pre-warmed complete medium immediately after electroporation and seeded into various multi-well plates depending on the experiments. To differentiate into skeletal muscle cells, MyoD mRNA- and MyoD mmRNA-transfected cells were incubated for 7 days with muscle differentiation medium composed of DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum and insulin/selenium/transferrin (Invitrogen). PolyI:C, R848 (both from Invivogen, San Diego, CA) and B18R (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) were used to modify innate immune activation during myogenic conversion.

2.4. Cytotoxicity assay

Fibroblasts (4 × 103 cells/well) in 90 μl of culture medium were incubated overnight in a 96-well plate. These cells were transfected as described above and incubated for 72 hours at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cytotoxicity was determined using Celltiter 96® MTS Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The percent cytotoxicity was calculated by using the following equation: % cytotoxicity = ([O.D.]untreated – [O.D.]treated)/[O.D.]untreated × 100.

2.5. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The production of IFN-β and IL-8 was determined using human and mouse IFN-β ELISA kit (PBL Biomedical Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ) and BD OptEIA™ IL-8 ELISA sets (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), respectively, by following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.6. Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). cDNA synthesis was performed in a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using Superscript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was carried out using the Taqman Gene Expression Assay (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). The PCR reactions for all assays were performed at 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 20 seconds, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 3 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds. The gene expression level was normalized to GAPDH as an internal reference.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The paired two-tailed Student’s t test was applied for determination of statistical significance. A probability of less than 0.05 (P < 0.05) was used for statistical significance.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Mouse and human fibroblasts are sensitive to mRNA-induced cytotoxicity

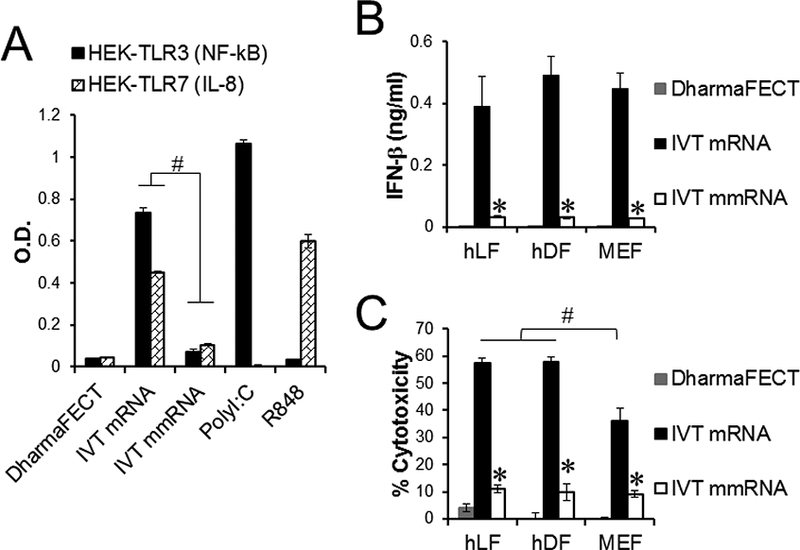

Consistent with a previous study [12], transfection with unmodified IVT mRNAs stimulated RNA-recognizing TLR3 and TLR7, whereas transfection with modified IVT mmRNAs significantly reduced stimulation of these TLRs (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, human and mouse fibroblasts transfected with IVT mRNAs produced IFN-β and underwent cell death, whereas fibroblasts transfected with IVT mmRNAs significantly decreased IFN-β production and cell death compared with fibroblasts transfected with IVT mRNAs (Fig. 1B and C). Although both human and mouse fibroblasts transfected with IVT mRNAs produced similar amounts of IFN-β human fibroblasts were more sensitive to IVT mRNA-induced cytotoxicity than mouse fibroblasts (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

TLR3 and 7 activation and cytotoxicity in IVT mRNA-transfected mouse and human fibroblasts. Mouse fibroblasts (MEF), human fibroblasts (hLF and hDF) and TLR3 and 7 reporter cells were transfected once with unmodified IVT actin mRNA (IVT mRNA) or modified IVT actin RNA (IVT mmRNA) using DharmaFECT. Cells transfected with DharmaFECT alone were used as a negative control. (A) Stimulation of TLR3 and 7 reporter cells were determined by analyzing NF-kB activity and IL-8 production, respectively. (B) IFN-β expression and (C) cytotoxicity in mRNA-transfected fibroblasts were determined using ELISA and MTS assay. #, P < 0.05 comparing indicated groups. ∗, P < 0.05 compared with cells transfected with DhamarFECT alone.

3.2. IFN-β secreted from mRNA-transfected cells inhibits repeated mRNA transfections

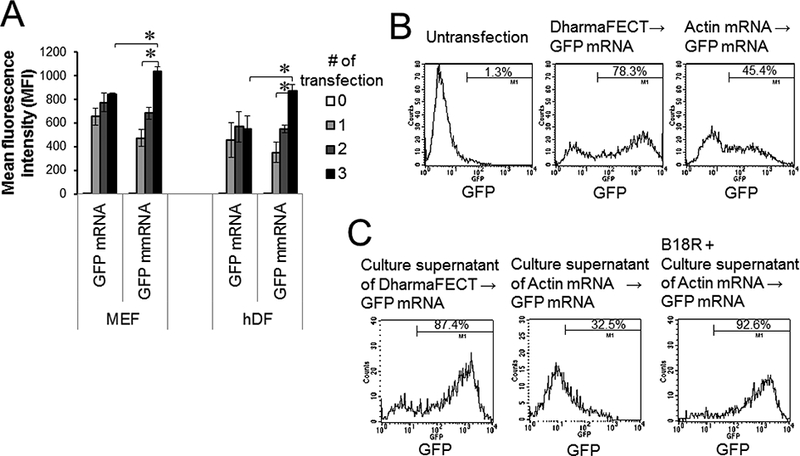

Repeated transfections with mRNAs are often required for mRNA-driven reprogramming of cells. Innate immune and inflammatory responses induced by mRNA transfection are known to inhibit repeated mRNA transfections [11]. The inhibitory mechanisms, however, are not fully understood. Human and mouse fibroblasts were transfected 1 to 3 times with either GFP mRNAs or GFP mmRNAs. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of GFP in the GFP mmRNA-transfected fibroblasts increased proportionally to number of transfections, but the MFI of GFP in the GFP mRNA-transfected fibroblasts was not significantly different between single transfection and multiple transfections (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, fibroblasts pre-transfected with actin mRNAs markedly decreased GFP expression after subsequent GFP mRNA transfection compared with fibroblasts pre-transfected with DharmaFECT alone (Fig. 2B). Next, we asked whether this inhibitory effect was transferable to non-transfected cells or occurred only in mRNA-pre-transfected cells. Interestingly, human fibroblasts pre-incubated with culture supernatants of actin mRNA-transfected fibroblasts abrogated the expression of GFP after transfection with GFP mRNAs, whereas fibroblasts pre-incubated with culture supernatants of mock-transfected fibroblasts highly expressed GFP after GFP mRNA transfection (Fig. 2C). The inhibitory effect of culture supernatants of actin mRNA-transfected fibroblasts was abolished by supplementation of culture supernatants with type I IFN blocking agent B18R (Fig. 2C). These data suggested that type I IFNs that are secreted from mRNA-transfected cells induced paracrine inhibition of repeated mRNA transfections.

Fig. 2.

Paracrine inhibition of mRNA transfection. (A) MEFs and hDFs were transfected with GFP mRNAs or GFP mmRNAs every day for 1–3 days. At 24 h after transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed for GFP expression. (B, C) hDFs were transfected with either DharmaFECT alone or actin mRNAs. At 48 h after transfection, cells and culture supernatants were harvested. (B) These cells were re-transfected with GFP mRNAs. (C) The culture supernatants were incubated for 24 h with fresh hDFs in the presence and absence of B18R, and the hDFs were transfected with GFP mRNAs. GFP expression was analyzed 24 h after GFP mRNA transfection. Data represents two individual experiments. ∗, P < 0.05 comparing indicated groups.

3.3. Myogenic conversion of mouse and human fibroblasts by repeated transfections with MyoD mRNAs and MyoD mmRNAs

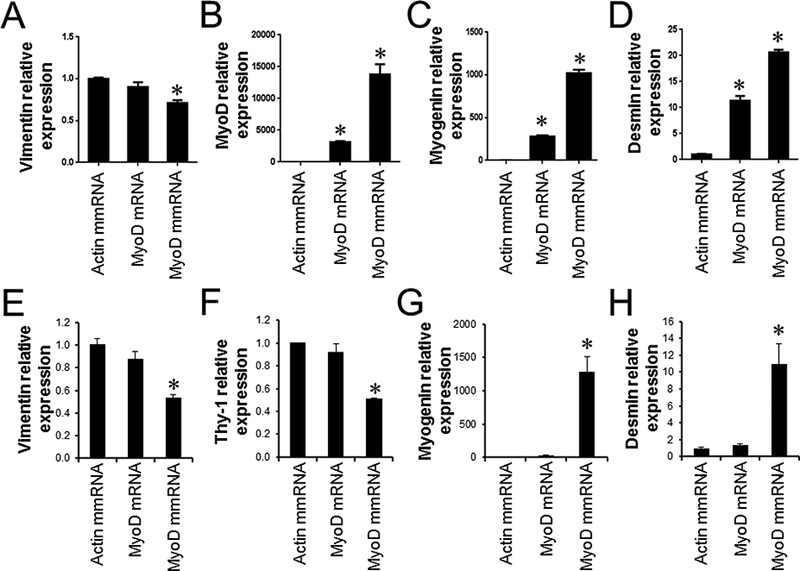

Next, we asked how differential induction of cytotoxicity and IFN-β expression in human and mouse fibroblasts by mRNA and mmRNA transfection influenced cellular reprogramming. Forced expression of muscle-determining factor MyoD has been shown to convert fibroblasts to skeletal muscle cells ex vivo [18]. MEFs repeatedly transfected with MyoD mmRNAs could be successfully converted into skeletal muscle-like cells (Fig. 3A-D and Fig. S1A). The myogenic conversion was assessed by the upregulation of skeletal muscle cell-associated molecules, e.g., MyoD (Fig. 3B), myogenin (Fig. 3C), desmin (Fig. 3D) and myosin heavy chain (MyHC) (Fig. S1A) and the downregulation of the fibroblast-associated molecule vimentin (Fig. 3A). MEFs repeatedly transfected with unmodified MyoD mRNAs appeared to convert into skeletal muscle-like cells although the myogenic conversion efficiency of MEFs transfected with MyoD mRNAs was 2–3 fold lower than cells transfected with modified MyoD mmRNAs (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B-D). In human fibroblasts, multiple transfections with modified MyoD mmRNAs followed by a 7-day culture in muscle differentiation medium changed human fibroblasts into skeletal muscle-like cells. These cells downregulated the expression of vimentin (Fig. 3E) and Thy-1 (Fig. 3F) and upregulated the expression of myogenin (Fig. 3G), desmin (Fig. 3H) and MyHC (Fig. S1B). The myogenic conversion efficiency of MyoD mmRNA-transfected human fibroblasts was comparable to that of MyoD mmRNA-transfected mouse fibroblasts. However, unlike mouse fibroblasts, human fibroblasts were not converted into skeletal muscle-like cells by repeated transfections with unmodified MyoD mRNAs (Fig. 3E-H and Fig. S1B).

Fig. 3.

Myogenic conversion of mouse and human fibroblasts by MyoD mRNA and mmRNA transfections. (A-D) MEFs and (E-H) hLFs were transfected every day for 5 days with either MyoD mRNAs or MyoD mmRNAs, followed by muscle differentiation as described in the Methods and Materials section. After a 7-day incubation in muscle differentiation medium, the cells were harvested and analyzed for the expression of skeletal muscle- and fibroblast-associated molecules. Fold changes are relative to actin mmRNA-transfected cells. Error bars indicate S.D.. ∗, P < 0.05.

3.4. mRNA electroporation or blocking of IFN signaling circumvents transfection-induced cytotoxicity

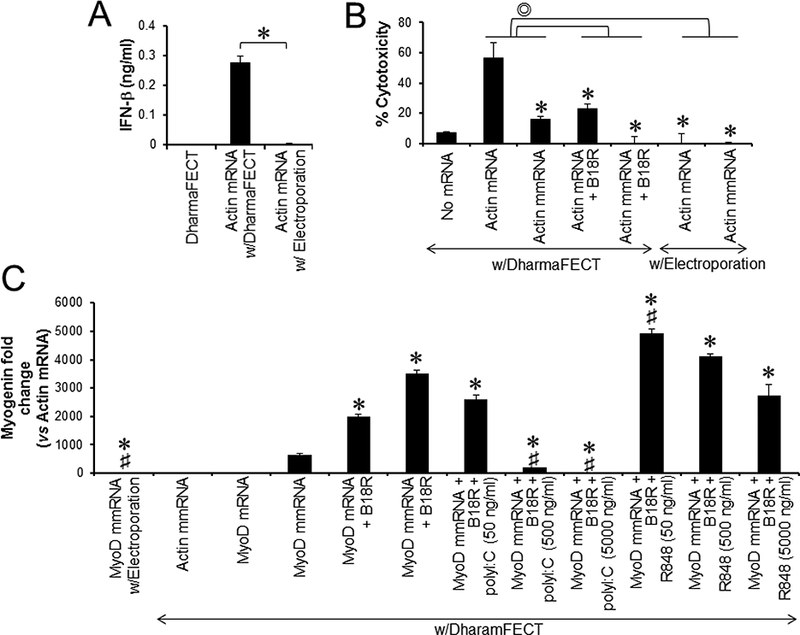

Although transfection with modified IVT mmRNAs significantly attenuated IFN-β expression and cytotoxicity in human and mouse fibroblasts compared with transfection with unmodified IVT mRNAs the IVT mmRNAs could not completely abolish induction of IFN-β expression and cytotoxicity in these cells (Fig. 1). Since innate immune activation and cytotoxicity is a formidable roadblock to mRNA-driven cellular reprogramming, we speculated that further reduction in mmRNA-induced IFN-β expression and cytotoxicity would enhance MyoD mmRNA-driven reprogramming of human fibroblasts into skeletal muscle cells. To test this hypothesis, we transfected human fibroblasts with MyoD mmRNAs while also inhibiting IFN signaling with B18R and evading the interaction between mmRNAs and RNA-sensing TLRs. It has been shown that direct delivery of RNA ligands into the cytoplasm by electroporation circumvented stimulation of RNA-sensing endosomal TLRs [19, 20]. Liposomal transfection with IVT mRNAs induced IFN-β expression and cytotoxicity in human fibroblasts, whereas electroporation of IVT mRNAs completely abrogated the ability of mRNAs to induce cytotoxicity and IFN-β expression in human fibroblasts (Fig. 4A-B). Furthermore, treatment with type I IFN inhibitor B18R completely abolished mmRNA-induced cytotoxicity in human fibroblasts (Fig. 4B). To exclude the possibility that electroporation may indirectly decrease mRNA-induced IFN-β expression and cytotoxicity by reducing mRNA transfection efficiency, we compared GFP mRNA transfection efficiency between electroporation and liposomal transfection. Electroporation required approximately 4-fold greater amount of GFP mRNAs than liposomal transfection to achieve a comparable MFI (Fig. S2). However, electroporation of GFP mRNAs did not induce IFN-β expression and cytotoxicity in human fibroblasts (Fig. 4A-B).

Fig. 4.

Differential effects of TLR stimulation on MyoD mRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts. (A) hLFs were transfected with actin mRNAs using either DharmaFECT or electroporation. Culture supernatants were harvested 48 h after transfection and analyzed for IFN-β production. (B) hLFs were transfected with actin mRNAs or actin mmRNAs using DharmaFECT or electroporation. The cells were cultured for 3 days in the presence or absence of B18R and analyzed for cytotoxicity. (C) hLFs were transfected every day for 5 days with MyoD mRNAs, MyoD mmRNAs or actin mmRNAs using either DharmaFECT or electroporation. The cells were cultured in the presence or absence of B18R, polyI:C and/or R848. After a 7-day incubation in muscle differentiation medium, the cells were harvested and analyzed for the expression of Myogenin expression by qPCR. Error bars indicate S.D.. Symbols indicating the statistically significant difference (P < 0.05): ∗ compared to cells with MyoD mRNA transfection; # compared to cells with MyoD mmRNA transfection in the presence of B18R.

3.5. Complete avoidance of RNA-sensing TLR activation inhibits MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts

Next, we asked whether complete avoidance of innate immune activation and cytotoxicity by the evasion of RNA-sensing TLR activation and IFN signaling would improve MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts. Blocking type I IFN responses significantly increased myogenin expression in human fibroblasts transfected with either modified MyoD mRNAs or unmodified MyoD mmRNAs, whereas electroporation impeded MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts (Fig. 4C). This data suggested that RNA-sensing TLR signaling might have biphasic activity in the mRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts. IVT mRNA transfection can stimulate RNA-sensing TLRs to lead to the induction of gene expression associated with innate and inflammatory responses, which negatively influences the mRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts. Thus, unmodified MyoD mRNAs that are strong innate immune stimulators converted fibroblasts into skeletal muscle cells significantly less efficiently than modified MyoD mmRNAs. On the other hand, TLR signaling might be essential for mRNA-driven myogenic conversion of fibroblasts. Thus, electroporation of MyoD mmRNAs completely evaded the stimulation of RNA-sensing TLRs and abrogated MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts. Lee et al. demonstrated that innate immune activation was required for the success of direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts, and transfection with defined factors or mRNAs encoding these factors failed to directly reprogram human fibroblasts into iPSCs in the absence of TLR stimulation [14]. One potential mechanism is that TLR stimulation leads to diverse epigenetic events including DNA methylation, histone modification and chromatin remodeling [21, 22]. These epigenetic modifications are indispensable for direct reprogramming and cell fate switching [23, 24]. Therefore, finely tuned TLR signaling is pivotal to the success or failure of myogenic conversion of fibroblasts by MyoD mRNA transfection.

3.6. TLR7/8 agonist improves MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts

Upon stimulation, TLRs recruit toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adapters, including TRIF and MyD88, which bind to the cytoplasmic TIR domain of TLRs [25]. These adapter molecules mediate a downstream cascade of TLR-associated signaling including IRF, IRAK, MAPK and NF-κB and the expression of genes associated with innate immune and inflammatory responses [26]. TRIF is recruited to TLR3 and TLR4, whereas MyD88 is associated with all TLRs except TLR3. It has been shown that TRIF- but not MyD88-deficient fibroblasts transduced with retroviral vectors encoding defined iPSC factors significantly reduced their capability to reprogram into iPSCs, and the TLR3 agonist, polyI:C could enhance iPSC generation from human fibroblasts by the transfection of mmRNAs encoding the iPSC factors [14]. We next asked whether TLR agonists would enhance MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts. Unlike iPSC generation, MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts was not enhanced by polyI:C but tended to be inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, TLR7/8 agonist R848 at low concentration (50 ng/ml) significantly enhanced MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts, and the efficacy of myogenic conversion was inversely correlated with the concentration of R848 (Fig. 4C). The relationship between the activation of TLR signaling pathway and reprogramming of fibroblasts into skeletal muscle cells has not been elucidated. Our data suggested that balancing the signal strength of TLR signaling would be a key determinant of mRNA-driven myogenic conversion. TLR signaling, regardless of which TLR is activated, culminates in the activation of MAPK and NF-κB. The MAPK and NF-kB signaling pathways play contradictory roles in skeletal myogenesis. The MAPK signaling pathway is known to promote skeletal myogenesis and maintain skeletal muscle function [27–29]. Co-transfection with MyoD and MAPK kinase 6 vectors yielded a 2-fold increase in myogenic conversion of MEFs compared to transfection of MyoD vector alone [30]. On the contrary, NF-κB signaling appears to negatively regulate skeletal myogenesis [31]. Deficiency of the p65 subunit of NF-kB significantly enhanced MyoD-driven myogenic conversion of MEFs and the differentiation of primary myoblasts [32]. It has not been elucidated whether the strength and types of TLR activation differentially modulated MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Further studies are needed to elucidate the precise mechanism to enhance or regulate mRNA-driven reprogramming of human and mouse fibroblasts by TLRs and PRRs.

Transfection with IVT mmRNAs that reduce TLR stimulation and cytotoxicity is an effective strategy to generate iPSCs and manipulate cell fate and lineage on demand without the risk of insertional mutagenesis of DNA vectors. However, reprogramming efficiency of modified mmRNA transfection still needs to be improved. In the current study, we found that modulation of endosomal TLR activation and type I IFN signaling could significantly improve MyoD mmRNA-driven myogenic conversion of human and mouse fibroblasts. These mmRNA-driven muscle cells would be a potential cell source for cell therapy to replace damaged or aberrant muscle cells. Deliberate control of TLR signaling will make mRNA transfection a promising tool for direct reprogramming and transdifferentiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by The Robertson Foundation (BAS), NIH grant (DP2OD008586), and NSF grant CBET-1151035 (CAG). TMG was supported by NIH grant T32GM008555.

References

- [1].Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, Ebina W, Mandal PK, Smith ZD, Meissner A, Daley GQ, Brack AS, Collins JJ, Cowan C, Schlaeger TM, Rossi DJ, Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA, Cell Stem Cell, 7 618–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thier M, Worsdorfer P, Lakes YB, Gorris R, Herms S, Opitz T, Seiferling D, Quandel T, Hoffmann P, Nothen MM, Brustle O, Edenhofer F, Direct conversion of fibroblasts into stably expandable neural stem cells, Cell Stem Cell, 10 (2012) 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lee K, Yu P, Lingampalli N, Kim HJ, Tang R, Murthy N, Peptide-enhanced mRNA transfection in cultured mouse cardiac fibroblasts and direct reprogramming towards cardiomyocyte-like cells, International journal of nanomedicine, 10 (2015) 1841–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Simeonov KP, Uppal H, Direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by synthetic modified mRNAs, PLoS One, 9 (2014) e100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dogusan Z, Garcia M, Flamez D, Alexopoulou L, Goldman M, Gysemans C, Mathieu C, Libert C, Eizirik DL, Rasschaert J, Double-stranded RNA induces pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis by activation of the toll-like receptor 3 and interferon regulatory factor 3 pathways, Diabetes, 57 (2008) 1236–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].He S, Liang Y, Shao F, Wang X, Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108 (2011) 20054–20059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ishibashi O, Ali MM, Luo SS, Ohba T, Katabuchi H, Takeshita T, Takizawa T, Short RNA duplexes elicit RIG-I-mediated apoptosis in a cell type- and length-dependent manner, Science signaling, 4 (2011) ra74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Trinchieri G, Type I interferon: friend or foe?, The Journal of experimental medicine, 207 (2010) 2053–2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Drews K, Tavernier G, Demeester J, Lehrach H, De Smedt SC, Rejman J, Adjaye J, The cytotoxic and immunogenic hurdles associated with non-viral mRNA-mediated reprogramming of human fibroblasts, Biomaterials, 33 (2012) 4059–4068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Andries O, De Filette M, De Smedt SC, Demeester J, Van Poucke M, Peelman L, Sanders NN, Innate immune response and programmed cell death following carrier-mediated delivery of unmodified mRNA to respiratory cells, Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society, 167 (2013) 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Angel M, Yanik MF, Innate immune suppression enables frequent transfection with RNA encoding reprogramming proteins, PLoS One, 5 e11756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D, Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA, Immunity, 23 (2005) 165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kariko K, Muramatsu H, Welsh FA, Ludwig J, Kato H, Akira S, Weissman D, Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability, Mol Ther, 16 (2008) 1833–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee J, Sayed N, Hunter A, Au KF, Wong WH, Mocarski ES, Pera RR, Yakubov E, Cooke JP, Activation of innate immunity is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming, Cell, 151 (2012) 547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sayed N, Wong WT, Ospino F, Meng S, Lee J, Jha A, Dexheimer P, Aronow BJ, Cooke JP, Transdifferentiation of human fibroblasts to endothelial cells: role of innate immunity, Circulation, 131 (2015) 300–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee J, Dollins CM, Boczkowski D, Sullenger BA, Nair S, Activated B cells modified by electroporation of multiple mRNAs encoding immune stimulatory molecules are comparable to mature dendritic cells in inducing in vitro antigen-specific T-cell responses, Immunology, 125 (2008) 229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lee Y, Urban JH, Xu L, Sullenger BA, Lee J, 2’Fluoro Modification Differentially Modulates the Ability of RNAs to Activate Pattern Recognition Receptors, Nucleic Acid Ther, 26 (2016) 173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Davis RL, Weintraub H, Lassar AB, Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts, Cell, 51 (1987) 987–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sioud M, Induction of inflammatory cytokines and interferon responses by double-stranded and single-stranded siRNAs is sequence-dependent and requires endosomal localization, J Mol Biol, 348 (2005) 1079–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhou R, Norton JE, Zhang N, Dean DA, Electroporation-mediated transfer of plasmids to the lung results in reduced TLR9 signaling and inflammation, Gene therapy, 14 (2007) 775–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Qian C, Cao X, Regulation of Toll-like receptor signaling pathways in innate immune responses, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1283 (2013) 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gou Z, Liu R, Zhao G, Zheng M, Li P, Wang H, Zhu Y, Chen J, Wen J, Epigenetic modification of TLRs in leukocytes is associated with increased susceptibility to Salmonella enteritidis in chickens, PloS one, 7 (2012) e33627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cantone I, Fisher AG, Epigenetic programming and reprogramming during development, Nature structural & molecular biology, 20 (2013) 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhao R, Daley GQ, From fibroblasts to iPS cells: induced pluripotency by defined factors, Journal of cellular biochemistry, 105 (2008) 949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kawai T, Akira S, TLR signaling, Seminars in immunology, 19 (2007) 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].O’Neill LA, Bowie AG, The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling, Nature reviews. Immunology, 7 (2007) 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lluis F, Ballestar E, Suelves M, Esteller M, Munoz-Canoves P, E47 phosphorylation by p38 MAPK promotes MyoD/E47 association and muscle-specific gene transcription, The EMBO journal, 24 (2005) 974–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Simone C, Forcales SV, Hill DA, Imbalzano AN, Latella L, Puri PL, p38 pathway targets SWI-SNF chromatin-remodeling complex to muscle-specific loci, Nature genetics, 36 (2004) 738–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Perdiguero E, Ruiz-Bonilla V, Gresh L, Hui L, Ballestar E, Sousa-Victor P, Baeza-Raja B, Jardi M, Bosch-Comas A, Esteller M, Caelles C, Serrano AL, Wagner EF, Munoz-Canoves P, Genetic analysis of p38 MAP kinases in myogenesis: fundamental role of p38alpha in abrogating myoblast proliferation, The EMBO journal, 26 (2007) 1245–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zetser A, Gredinger E, Bengal E, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. Participation of the Mef2c transcription factor, The Journal of biological chemistry, 274 (1999) 5193–5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bakkar N, Guttridge DC, NF-kappaB signaling: a tale of two pathways in skeletal myogenesis, Physiological reviews, 90 (2010) 495–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bakkar N, Wang J, Ladner KJ, Wang H, Dahlman JM, Carathers M, Acharyya S, Rudnicki MA, Hollenbach AD, Guttridge DC, IKK/NF-kappaB regulates skeletal myogenesis via a signaling switch to inhibit differentiation and promote mitochondrial biogenesis, The Journal of cell biology, 180 (2008) 787–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.