Abstract

Objective

Despite wide adoption of Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) across the United States, predictors of in-hospital mortality for patients receiving RRT calls are poorly characterized. Identification of patients at high risk of death during hospitalization could improve triage to intensive care units and prompt timely reevaluations of goals of care. We sought to identify predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients who are subjects of RRT calls and to develop and validate a predictive model for death after RRT call.

Design

Analysis of data from the national Get with the Guidelines (GTWG)- Medical Emergency Team (MET) event registry.

Setting

274 hospitals participating in GWTG-MET from June 2005 to February 2015.

Patients

282,710 hospitalized adults on surgical or medical wards who were subjects of an RRT call.

Interventions

None

Measurements and Main Results

The primary outcome was death during hospitalization; candidate predictors included patient demographic- and event- level characteristics. Patients who died after RRT were older (median age 72 vs. 66 years), more likely to be admitted for non-cardiac medical illness (70% vs. 58%), and had greater median length of stay prior to RRT (81 vs. 47 hours) (p<0.001 for all comparisons). The prediction model had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.78 (95% CI 0.78-0.79), with systolic blood pressure, time since admission, and respiratory rate being the most important variables.

Conclusions

Patients who die following RRT calls differ significantly from surviving peers. Recognition of these factors could improve post-RRT triage decisions and prompt timely goals of care discussions.

Keywords: Hospital Rapid Response Team, Hospital Medical Emergency Team, Machine Learning, Risk Assessment

Introduction

The prevalence of Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) has increased dramatically since the concept's introduction in the 1990s, with near ubiquitous adoption across the United States and other parts of the world.[1, 2] These systems include an afferent component, which seeks to prospectively identify deteriorating hospitalized patients, and an efferent component, which aims to direct clinical resources and appropriately triage at-risk patients to higher levels of care. The overall purpose of this system is to reduce preventable in-hospital morbidity and mortality; however, whether RRTs achieve this goal is still unclear.[3-7]

To date, a significant amount of RRT research has focused on the afferent function of RRTs, with many studies examining predictors of cardiac arrest and clinical deterioration for general wards patients as criteria for RRT activation.[8-10] However, data to guide the efferent functions of RRTs, such as triaging patients to intensive care units (ICUs) or initiating timely goals of care discussions, is limited. Despite the pervasiveness of RRTs, very little is known about outcomes and predictors of death for patients who are subjects of an RRT call. Given that severity of illness is likely to differ significantly between all floor patients and those requiring RRT, existing score systems for identifying high risk floor patients, such as the National Early Warning System (NEWS), may not sufficiently differentiate high from low risk RRT patients. Accurate risk stratification at the time of the RRT call could enable improved resource allocation, spur goals of care discussions, and allow for timely initiation of transfer to higher level of care for those at highest risk, with the potential to improve overall efficacy of rapid response systems.

The aims of this study are 1) to use a large, national registry of RRT events to describe predictors of in-hospital mortality for patients receiving RRT calls, 2) to develop and validate a model to predict in-hospital death after RRT calls, and 3) to compare the performance of this model to the commonly employed NEWS score for predicting in-hospital mortality in patients who received RRT calls.

Methods

Data source

The Get With the Guidelines (GWTG)- Medical Emergency Team (MET) registry, a prospective, multicenter registry of patients with RRT activation, was used to perform this study. This registry is a component of the larger American Heart Association-sponsored GWTG research databases, for which the registry design has been previously described in detail by studies utilizing the separate cardiac arrest GWTG-Resuscitation registry.[11] Briefly, all patients with RRT activations were identified and enrolled by trained quality improvement personnel and patient and event characteristics were recorded using standardized collection tool. Data accuracy within the database was ensured by certification of data entry staff, use of case-study methods for newly enrolled hospitals before submission of data, and use of standardized software with built-in checks for missing or outlying values. A re-abstraction process has demonstrated a mean error rate of less than 5% for all data in the GWTG-Resuscitation.[11] All participating GWTG institutions were required to comply with local regulatory and privacy guidelines and, if required, to secure institutional review board approval. Because data were used primarily at the local site for quality improvement, sites were granted a waiver of informed consent under the common rule.

Study Population

The study population was derived from data submitted on RRT events at all acute care hospitals participating in the GWTG MET registry between June 2005 and February 2015 and included all adult patients who were subjects of a RRT call while hospitalized on an inpatient ward, including those who were later transferred to the ICU. Data from hospitals with fewer than 50 RRT events recorded over the study period were excluded. Events with missing or pending patient survival data were excluded, as this was the primary study outcome. Events involving patients under 18 years of age, those called on non-hospitalized persons (e.g. staff members or visitors), those occurring outside of an in-patient telemetry or non-telemetry ward (e.g. ICU, emergency department, procedural suite, or operating room), and events missing illness category or location data were also excluded (see Appendix Figure 1). Finally, RRT call date and times and patient ID numbers were used to temporally order RRT events for those individuals with more than one qualifying RRT call during a hospitalization. When call date or time was missing for an event, it was imputed from the recorded RRT arrival time or RRT departure time. Only the first event on the general or telemetry wards was included in the study.

Study Outcome and Variables

The primary study outcome was in-hospital mortality. The patient and event characteristics examined as candidate predictors of the primary outcome included demographics (age, sex, and race/ethnicity [white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, other, missing]), time in hours from admission to RRT event, illness category (medical cardiac, medical non-cardiac, surgical cardiac, surgical non-cardiac, obstetric, trauma), event location (general inpatient, telemetry/step-down), previous ICU stay during hospitalization, post-anesthesia care unit stay within 24 hours of event, admission from emergency department within 24 hours of event, sedation within 24 hours of event, trigger for RRT (respiratory [respiratory depression, tachypnea, difficulty breathing, hypoxia], cardiovascular [bradycardia, tachycardia, hypotension, chest pain], neurologic [mental status change, agitation or delirium, loss of consciousness, seizure, suspected stroke], decreased urine output, bleeding, staff worry, other trigger), total number of triggers, and vital signs at time of RRT activation (heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation).

Statistical Analysis

Differences between patients who survived to discharge and those who did not were evaluated using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate, for continuous variables. For model development, two-thirds of the study population was randomly selected for the derivation cohort and one-third for the validation cohort. All model tuning was performed in the derivation dataset. If vital signs values at the time of the RRT call were missing, then the value closest to the time of the call was imputed. For the remaining missing vital signs, median values were imputed. Because previous studies have shown that modern machine learning methods can develop more accurate models than traditional regression, a gradient boosted machine (GBM) algorithm was used in this study.[12] We have previously shown that this method has both excellent discrimination and calibration when used to predict outcomes using physiologic data in ward patients.[12] This method involves creating sequential decision trees, with each additional tree predicting the outcome of interest with the cases missed by the prior trees weighted more heavily. It automatically investigates interactions between variables and allows for non-linear relationships between the variables and the outcome of interest. The tuning parameters for the algorithm (learning rate, tree depth, and number of trees) were optimized in the derivation dataset using 10-fold cross-validation to maximize the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). A second model was developed using multivariable logistic regression with continuous variables entered as linear terms to determine if this simpler model would have accuracy similar to that of the more complex GBM model. To ensure parsimony and inclusion of only those variables that provide significant value, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (Lasso) method was employed for variable selection. Finally, a modified version of the NEWS was calculated in the validation dataset for comparison purposes, with the neurologic triggers denoted as abnormal mental status and with the omission of the “on room air” variable, as it was not available in the dataset. Model discrimination was assessed and compared between algorithms using the AUC in the validation dataset. Data analysis was performed using Stata (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) and R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria). Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 402,023 RRT events at 360 acute care hospitals included in the database over the study time period, 18,698 were excluded for missing or pending survival; 10,010 were excluded for being called on subjects who were not adults, not hospital patients, or located outside of a general or telemetry ward; and 1,058 were excluded for coming from an institution with fewer than 50 RRTs recorded over the study period (Appendix Figure 1).

The final study cohort included 282,710 index RRT calls occurring on the wards at 274 institutions. Of these, 42,581 (15%) died during the hospital admission. Thirty-three percent (n=91,796) of patients were transferred to the ICU at the conclusion of their index RRT, of which 21,645 (24%) died. Patient and RRT event characteristics in patients who survived versus died are shown in Table 1. Patients who died were older (median age 72 years vs. 66 years), were more likely to be male (52% vs. 47%), were more likely to be admitted for a medical non-cardiac illness (70% vs. 58%), and had longer time between admission and index RRT (median 81 hours vs. 47 hours) (p<0.001 for all comparisons). Vital signs were more likely to be abnormal in patients who died, with higher rates of tachypnea (respiratory rate ≥25 breaths/minute; 40% vs. 24%), hypotension (systolic blood pressure ≤90 mmHg; 25% vs 14%), and hypoxia (oxygen saturation ≤91%; 33% vs. 18%) amongst those who died compared to those who survived their hospital stay (p<0.001 for all comparisons, see Table 2).

Table 1. Comparison of demographic and event characteristics of Rapid Response Team (RRT) calls between those who survived versus died during the hospitalization.

| Variable | Survived n=239,129 |

Died n=43,581 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 66 (53-78) | 72 (60-82) | <0.001 |

| Age category, years, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| <55 | 64,288 (26) | 6,872 (16) | |

| 55-69 | 72,256 (30) | 12,581 (29) | |

| 70-79 | 50,106 (21) | 10,542 (24) | |

| ≥80 | 52,479 (22) | 13,586 (31) | |

| Male sex, n (%) | 111,420 (47) | 22,547 (52) | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 164,624 (69) | 30,980 (71) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 45,054 (19) | 7,867 (18) | |

| Hispanic | 12,092 (5) | 1,873 (4) | |

| Other (includes Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, Biracial) | 4,355 (2) | 830 (2) | |

| Unknown or missing | 13,004 (5) | 2,031 (5) | |

| Illness category, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Medical, cardiac | 49,274 (21) | 8,033 (18) | |

| Medical, non-cardiac | 139,372 (58) | 30,610 (70) | |

| Surgical, cardiac | 6,054 (3) | 680 (2) | |

| Surgical, non-cardiac | 41,053 (17) | 3,985 (9) | |

| Obstetric | 1,026 (<1) | 16 (<1) | |

| Trauma | 2,350 (1) | 257 (1) | |

| Hours since admission, median (IQR) | 47 (17-115) | 81 (27-198) | <0.001 |

| Hours since admission category, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| <18 h | 61,210 (26) | 7,997 (18) | |

| 18-47 hours | 57,063 (24) | 7,528 (17) | |

| 48-119 | 60,277 (25) | 10,436 (24) | |

| ≥120 | 60,406 (25) | 17,580 (40) | |

| Location, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| General inpatient | 142,946 (60) | 24,977 (57) | |

| Telemetry or step down | 96,183 (40) | 18,604 (43) | |

| ICU prior to RRT, n (%) | 28,937 (12) | 6,794 (16) | <0.001 |

| PACU within 24 hours, n (%) | 18,179 (8) | 1,051 (2) | <0.001 |

| ED within 24 hours, n (%) | 52,209 (22) | 7,258 (17) | <0.001 |

| Sedation within 24 hours, n (%) | 22,822 (1) | 1,841 (4) | <0.001 |

| Transferred to ICU post-RRT, n (%) | 70,151 (29) | 21,645 (50) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: IQR=interquartile range; ICU=intensive care unit; PACU=post-anesthesia care unit; ED=emergency department

Table 2. Vital signs and NEWS score at time of Rapid Response Team activation.

| Variable | Survived n=239,129 |

Died n= 43,581 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory rate (breaths/minute), mean (SD) | 21.9 (7.4) | 24.9 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate ≥25, n (%) | 56,141 (24) | 17,247 (40) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate ≤8, n (%) | 2,692 (1) | 808 (2) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/minute), mean (SD) | 98.3 (30.8) | 102.9 (30.2) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate ≥130, n (%) | 36,686 (15) | 7,948 (18) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate ≤40, n (%) | 2,936 (1) | 721 (2) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 130 (36) | 117 (35.9) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure ≥220, n (%) | 3,064 (1) | 269 (1) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure ≤90, n (%) | 34,425 (14) | 11,076 (25) | <0.001 |

| Temperature (°C), mean (SD) | 36.7 (0.7) | 36.6 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Temperature ≤35, n (%) | 1,634 (1) | 742 (2) | <0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation (%), median (IQR) | 96 (93-98) | 95 (89-97) | <0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation ≤91, n (%) | 43,962 (18) | 14,389 (33) | <0.001 |

| NEWS score, mean (SD) | 4.6 (2.8) | 6.4 (2.9) | <0.001 |

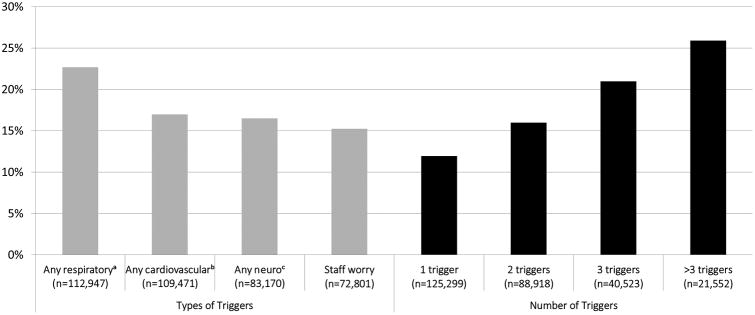

Triggers for RRT activation also differed significantly between patients who died during the hospitalization compared to those who survived, with patients who died more likely to have a respiratory trigger (59% vs. 37%), particularly tachypnea (21% vs. 12%) or hypoxia (37% vs. 21%), or to have RRT called for hypotension (24% vs. 15%) (p<0.001 for all comparisons). In-hospital mortality was found to increase with number of simultaneous RRT triggers documented per RRT call, from 12% for calls with one trigger to 26% for calls with >3 triggers (Figure 1; p<0.001).

Figure 1.

In-hospital mortality by trigger type and number of triggers for Rapid Response Team calls.

aIncludes respiratory depression, tachypnea, difficulty breathing, and hypoxia.

bIncludes bradycardia, tachycardia, hypotension, and chest pain.

cIncludes mental status change, agitation or delirium, loss of consciousness, seizure, and suspected stroke

Patients with an RRT call who died after not being transferred to the ICU at the end of the RRT call were older (median age 74 vs. 70 years), more likely to be hospitalized for a medical, non-cardiac illness (71 vs. 69%), and more likely to be on a non-telemetry general ward than those who died and were transferred to an ICU at the end of the RRT call (see Appendix Table).

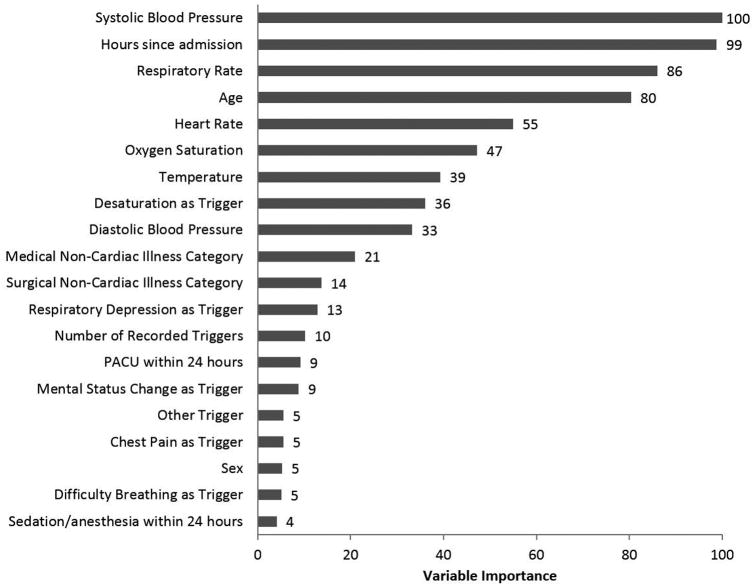

The final, optimized GBM algorithm had an AUC in the validation dataset of 0.78 (95% CI 0.78-0.79). Systolic blood pressure, time from hospital admission to the RRT call, and respiratory rate were the three most important variables in the model (Figure 2). The multivariable logistic regression model AUC was significantly lower (0.73 (95% CI 0.73-0.73) than the GBM model (p<0.01 for AUC comparison). Both logistic regression and GBM models were more accurate than the NEWS, which had an AUC of 0.66 (95% CI 0.66-0.67) (p<0.01 for both comparisons).

Figure 2.

Importance of the predictor variables in the gradient boosted machine model, scaled to a maximum of 100

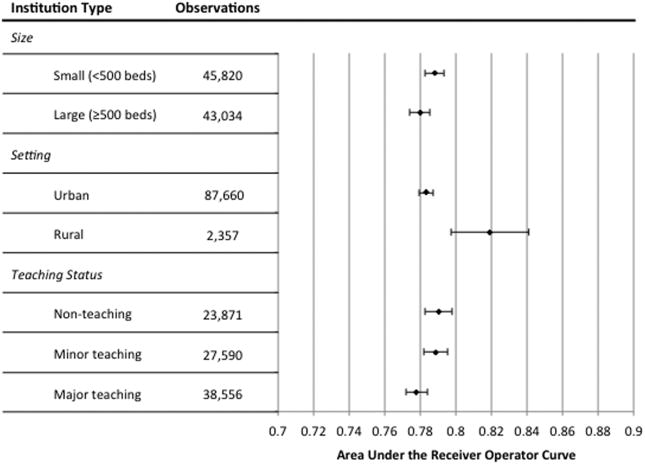

To assess generalizability of the developed GBM model, AUCs were computed for observations at various institution types, including rural, urban, minor teaching, major teaching, non-teaching, large (greater than or equal to 500 beds), and small (less than 500 beds) hospitals, with all AUC results falling between 0.78-0.82 (see Figure 3). The final model was well calibrated in the validation cohort, as shown in the observed versus predicted in-hospital mortality calibration plot (Appendix Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Area under the receiver operator characteristic curves (AUCs) of the gradient boosted machine algorithm by institution type and in all hospitals (solid vertical line) in the validation cohorts.

Discussion

In this study, we utilized a large, nationwide database to identify significant, clinically relevant variables for predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with RRTs calls, as well as to create and validate an accurate prediction model for death during hospitalization in patients following their first RRT on the wards. To our knowledge, it is the first statistically derived tool developed to predict in-hospital mortality after RRT calls. RRT patients who die in the hospital differ significantly from their surviving peers in many ways— most notably they tend to be older, admitted for medical non-cardiac disease, have longer periods between admission and RRT, and have more deranged vital signs—and these differences can be leveraged to improve care at the patient, hospital, and systems levels.

Critical care physicians are often the guardians of limited ICU resources, and our model enables RRT physicians and staff to make evidence-based triage decisions during an RRT call. By identifying the highest risk patients for prompt escalation of care, the model may improve outcomes for patients on the general wards. Further, the model's ability to accurately differentiate lower risk patients may allow triage leaders to more confidently allow low risk patients to remain on the floor, improving efficiency and safely decreasing costs

Our results provide evidence to help guide physicians and RRT staff in the efferent functions of the RRT. Most of the variables found to predict death in patients with RRT calls are quickly and easily assessed at bedside or from superficial assessment of patients' charts. While some of the characteristics predictive of death are not surprising and have been previously described, such as age and vital sign derangements,[13] others are less intuitive, such as the importance of when the RRT call occurs during a patient's admission and the high mortality for calls triggered by respiratory concerns. Interestingly, systolic blood pressure was the most important predictor of mortality included in our GBM model, which differs from prior work showing respiratory rate to be the most predictive vital sign for detecting clinical deterioration in general wards patients.[12] Hours since admission was the second most important predictor of mortality in our model, with RRT calls occurring later in the hospitalization being associated with decreased survival. This may be related to the fact that patients with later RRTs are more likely to have failed initial medical therapy or developed a complication. These results also could be due to the fact that delays in calling the RRT may result in worse outcomes. Recognition of these risk factors in a patient receiving an RRT call could prompt earlier ICU transfers for patients with more high-risk factors and potentially provide objective data to facilitate discussion of need for transfer between RRT and ICU staff, especially for patients who otherwise may lack a clear ICU indication.

There has also been significant interest in leveraging rapid response systems to help improve end-of-life care and avoid futile interventions at the end of life,[13-16] with some evidence to support that RRT deployment is associated with improved end-of-life pain management and psychosocial care.[17] Awareness of risk factors for death in this population may prompt RRT or primary team providers to more frequently address patient comfort and initiate frank discussions of prognosis and treatment limitations with patients and families. In particular, our developed model could be used to calculate a predicted probability of death during admission, which could then complement other information such as patient co-morbidities and preferences for aggressive care. While it is essential that scores from the model indicating high risk of death not be applied in such a way as to impose inflexible limitations of care upon patients, we believe that a high score could serve as a valuable prompt for initiating goals of care discussions of palliative care services in a personalized, patient-specific way when appropriate. This would enable more efficient and effective use of scarce resources and would strengthen the RRTs ability to become active participants in goals of care discussions.

Our finding of the poor accuracy of the NEWS for predicting in-hospital mortality among patients receiving RRT calls also has important implications. The NEWS has been previously shown to have good to excellent discrimination for predicting in-hospital mortality among all hospitalized patients on the wards. However, our findings demonstrate that NEWS performs considerably worse when predicting outcomes of patients already receiving an RRT call. The improvement in AUC translates into significantly improved identification of high risk patients without increased workload. For example, compared to a NEWS score of >4, which has a sensitivity of 72.9% for predicting death, at the same specificity (49.8%) our GBM model has a sensitivity of 88.2%, detecting an additional 15.3% of patients who go on to die. At a NEWS threshold >6, our model picks up an additional 19.3% of deaths, increasing the sensitivity from 47.9% to 67.2% at the same specificity of 74.2%. This is likely because patients receiving a call are already showing signs of clinical deterioration and therefore new tools are necessary to accurately predict outcomes in this patient population. This should not come as a surprise given that our model was created and validated in precisely this patient population, but the superior accuracy of our developed GBM model provides a more appropriate resource for post-RRT decision-making. Although the model is complex, we have made a freely available online tool that can be used to calculate the score in order to allow it to be used by interested clinicians (http://shiny.cac.queensu.ca/CritCareMed/RRT_mortality/).

In addition to benefits at the bedside, our results have potential applications for quality improvement initiatives at the institutional and healthcare system level. While rapid response systems are ubiquitous in the U.S., system design and the severity of illness of hospitalized patients vary widely across institutions, making generalizable assessments of RRT performance challenging. Our developed model can be used to estimate expected mortality rates based upon patient and event characteristics for a given population of patients at the time of their first ward RRT call, which may then be compared to observed mortality rates. At the institutional level, this could allow rapid response systems to track their own performance over time in a way that accounts for changes in physiologic severity of illness in the population it serves, as well as to compare performance to a historical national average. For healthcare systems comprised of multiple sites with heterogeneous populations, the model could allow comparisons between locations and targeted site improvements.

One potential criticism of our study is that the prediction model is complex and will require infrastructure for real world use. While it is true that a score cannot be computed with pen and paper at bedside, with the rise of electronic medical records, utilizing even complex models is becoming increasingly feasible. Further, we have created an online calculator to allow for score calculation. Another potential limitation is that our results reflect only those patients at hospitals who participate in the GWTG MET database. However given the large number of included institutions, their breadth and depth, and the excellent performance of our model across institution types, generalizability of our score is likely to be good. An additional limitation is that we did not have whether the patient was on room air for NEWS score calculation, which may result in an underestimation of its accuracy. However, most of the over 100 early warning scores in use in hospitals today do not include this variable. Additionally, information about whether patients had Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) orders or other stated limitations of care placed were not available for the vast majority of patients included in the database. It is likely that at least some portion of patients who were not transferred to the ICU after their RRT and subsequently died on the floor had DNAR orders, and thus did so appropriately. Lastly, our model does not include information on patient frailty or comorbidities. Such information would help define the study population and likely improve the performance of our model. However this information was not available in the database we utilized.

Conclusion

We used a large multicenter database to identify predictors of death after RRT and to develop and validate a risk-stratification tool for hospitalized patients who are subjects of an RRT call on the wards. Our model outperforms the widely used NEWS score for predicting death in this population. Physicians and RRT staff can use our results and the online risk-stratification tool to help inform clinical decision-making and facilitate discussions with patients and families. This model may also serve as a generalizable tool for objective assessment and improvement of rapid response systems at the institutional or national level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nicole Twu, MS and Amy Praestgaard, MS for administrative support during the project.

Financial Disclosures: Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. Dr. Churpek is supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080). In addition, Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA) and from Early Sense (Tel Aviv, Israel). She has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients.

Copyright form disclosure: Dr. Edelson's institution received funding from Philips Healthcare and EarlySense, and she disclosed she has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. Drs. Edelson and Churpek have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. Dr. Churpek's institution received funding from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080), and he received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators: Besides the authors Dana P. Edelson, MD, MS and Matthew M. Churpek, MD, MPH, PhD, members of the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Adult Research Task Force include:

Saket Girotra, MBBS, SM, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine; Benjamin Abella MD Mphil, University of Pennsylvania; Monique L. Anderson, MD, Duke University School of Medicine; Romergryko Geocadin, MD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Zachary D Goldberger MD MS, University of Washington School of Medicine; Patricia K Howard PhD, RN, University of Kentucky Healthcare; Michael C Kurz MD, University of Alabama School of Medicine; Vincent N. Mosesso, Jr., MD, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; Boulos Nassar MD MPH, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics; Joseph P. Ornato, MD and Mary Ann Peberdy, MD, Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center; Sarah M. Perman, MD, MSCE, University of Colorado School of Medicine

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Edelson DP, Yuen TC, Mancini ME, et al. Hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation practice in the United States: a nationally representative survey. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(6):353–357. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steel AC, Reynolds SF. The growth of rapid response systems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(8):489–495. 433. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priestley G, Watson W, Rashidian A, et al. Introducing Critical Care Outreach: a ward-randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(7):1398–1404. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9477):2091–2097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66733-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maharaj R, Raffaele I, Wendon J. Rapid response systems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2015;19:254. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0973-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon RS, Corwin GS, Barclay DC, et al. Effectiveness of rapid response teams on rates of in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):438–445. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan PS, Khalid A, Longmore LS, et al. Hospital-wide code rates and mortality before and after implementation of a rapid response team. JAMA. 2008;300(21):2506–2513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schein RM, Hazday N, Pena M, et al. Clinical antecedents to in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Chest. 1990;98(6):1388–1392. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.6.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D, et al. A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom--the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation. 2004;62(3):275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buist M, Bernard S, Nguyen TV, et al. Association between clinically abnormal observations and subsequent in-hospital mortality: a prospective study. Resuscitation. 2004;62(2):137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58(3):297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Winslow C, et al. Multicenter Comparison of Machine Learning Methods and Conventional Regression for Predicting Clinical Deterioration on the Wards. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(2):368–374. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardona-Morrell M, Chapman A, Turner RM, et al. Pre-existing risk factors for in-hospital death among older patients could be used to initiate end-of-life discussions rather than Rapid Response System calls: A case-control study. Resuscitation. 2016;109:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coombs MA, Nelson K, Psirides AJ, et al. Characteristics and dying trajectories of adult hospital patients from acute care wards who die following review by the rapid response team. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2016;44(2):262–269. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1604400213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downar J, Barua R, Rodin D, et al. Changes in end of life care 5 years after the introduction of a rapid response team: a multicentre retrospective study. Resuscitation. 2013;84(10):1339–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones D, Moran J, Winters B, et al. The rapid response system and end-of-life care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19(6):616–623. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283636be2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vazquez R, Gheorghe C, Grigoriyan A, et al. Enhanced end-of-life care associated with deploying a rapid response team: a pilot study. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):449–452. doi: 10.1002/jhm.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.