Abstract

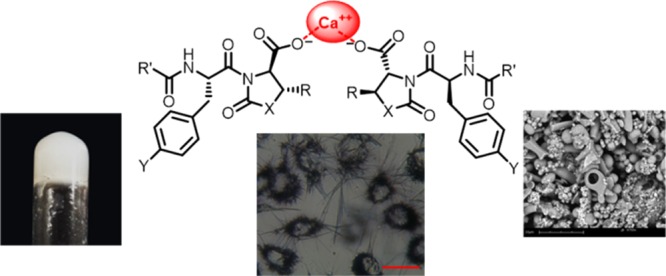

Pseudopeptides containing the d-Oxd or the d-pGlu [Oxd = (4R,5S)-4-methyl-5-carboxyl-oxazolidin-2-one, pGlu = pyroglutamic acid] moiety and selected amino acids were used as low-molecular-weight gelators to prepare strong and thixotropic hydrogels at physiological pH. The addition of calcium chloride to the gelator solutions induces the formation of insoluble salts that get organized in fibers at a pH close to the physiological one. Physical characterization of hydrogels was carried out by morphologic evaluation and rheological measurements and demonstrated that the analyzed hydrogels are thixotropic, as they have the capability to recover their gel-like behavior. As these hydrogels are easily injectable and may be used for regenerative medicine, they were biologically assessed by cell seeding and viability tests. Human gingival fibroblasts were embedded in 2% hydrogels; all of the hydrogels allow the growth of encapsulated cells with a very good viability. The gelator toxicity may be correlated with their tendency to self-assemble and is totally absent when the hydrogel is formed.

Introduction

Regenerative medicine is a field of increasing interest as it promotes tissue healing after injuries and diseases.1 Tissue engineering involves the use of biomaterial scaffolds to create in vitro three-dimensional (3-D) tissuelike structures that simulate the extracellular matrix (ECM) where cells can grow,2−4 as often typical bidimensional cell cultures lack the ability to effectively simulate the physiological environment. As hydrogels are constituted mainly of water (>95%), they have been extensively studied as materials for cell culture and cell encapsulation5−12 and may be injected to act locally in the specific region to be treated,13−15 avoiding surgical procedures.

For these applications, the most studied hydrogels are based on natural biopolymers, such as collagen, fibrin, hyaluronic acid, gelatin, chitosan, cellulose, alginate, and agarose.6,16 These biomaterials do not meet simultaneously all of the design parameters of an ideal injectable hydrogel (cell adhesion, lifetime, body compatibility, and mechanical strength); moreover, their gelation and mechanical properties cannot be tuned, as they should be used without any chemical modification to maintain their biocompatibility.

In contrast, short peptide chains, that act as low-molecular-weight gelators (LMWGs) as they contain several aromatic rings that favor the formation of hydrogels by means of π–π interactions,9,17−22 are biocompatible and may form hydrogels under several conditions; thus, they enable us to finely tune all of the properties to reach the optimal condition for 3-D cell cultures and good mechanical strength.

Several techniques may promote the gelation process of these molecules, salt addition,19,23,24 pH variation,25,26 enzymatic cleavage,27,28 dissolution in solvent mixtures,4 ultrasound sonication,29,30 although some of these methods may cause cell death.

As LMWGs self-assemble by physical interactions, the hydrogels may show a thixotropic behavior, which means that the gel becomes liquid if a shear stress is applied and then it quickly recovers the solid form on resting.31−34 This property allows us to easily inject by syringe the molten hydrogel, which self-adapts in the space inside the injection site and quickly recovers the solid form.35 Currently, there is no way to predict whether a peptide will be a good hydrogelator; nevertheless, a variety of systematic studies show that amphiphilic peptides and N-protected peptides with aromatic groups are able to form gels in water.36−38

We recently reported several pseudopeptides that freeze water in low concentration and form hydrogels that possess high mechanical strength and transparency.39−41 All of these peptides showed a good propensity to self-assemble in water because of the presence of the d-Oxd or d-pGlu moiety [Oxd = (4R,5S)-4-methyl-5-carboxyl-oxazolidin-2-one, pGlu = pyroglutamic acid] in their skeleton.42,43 The constraint imposed by the trans conformation of the two carbonyls of the Oxd and pGlu moieties, together with the presence of aromatic rings, allows the formation of intramolecular interactions that lead to the creation of fibers,44,45 which self-assemble to yield a gel.

The pH variation method25 used to trigger the gelation process of these compounds allows the formation of gels with low pH values that are not suitable for cell proliferation.

In the present study, we discuss the preparation, characterization, and biological assessment of hydrogels prepared using pseudopepetide gelators, containing the d-Oxd or d-pGlu moiety and selected amino acids. Calcium chloride is used as a trigger to form strong and thixotropic hydrogels at physiological pH, emulating what is usually done to form alginate hydrogels.7,46,47

Results and Discussion

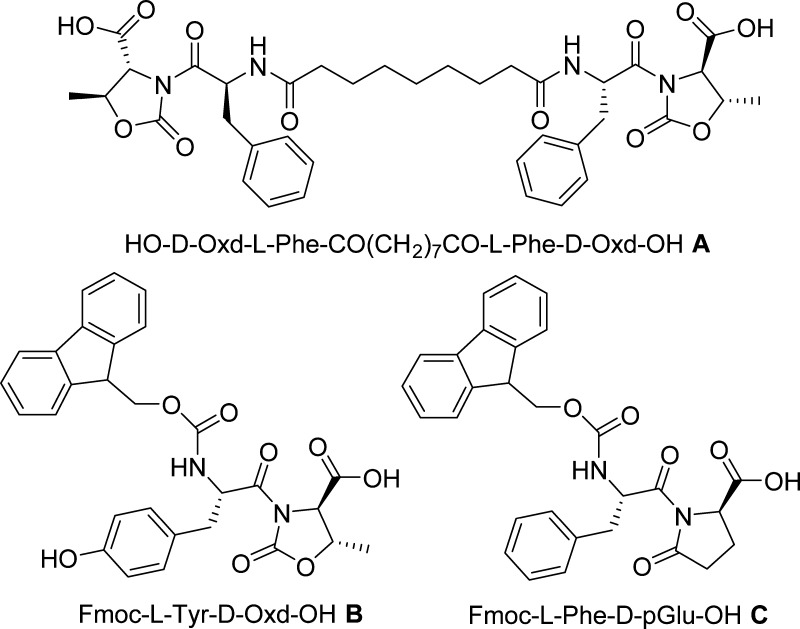

Gelators A–C (Figure 1) were prepared in multigram scale, starting from commercially available d-Thr, d-Glu, Fmoc-l-Tyr(t-Bu)-OH, Fmoc-l-Phe-OH, and azelaic acid, by standard coupling and protection/deprotection procedures, as previously reported.21,30,39,42

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of gelators A–C studied in this work.

The hydrogels have been prepared using gelators A–C in either 1 or 2% w/w concentration and a stoichiometric amount of aqueous 1 M NaOH. The procedure adopted to form the hydrogel is crucial to obtain good and reproducible results: if CaCl2 is added to a standing gelator solution, a gel rapidly forms, but after a few hours, it collapses, forming a precipitate. In contrast, CaCl2 addition to stirred solutions ends up with the formation of hydrogels that are stable for days. This phenomenon is probably related to the nonuniformity of the hydrogels formed when stirring is missing.

As calcium is a covalent cation and behaves as a supramolecular cross-linker between the carboxylic moieties of the gelators molecules,47,48 we added a stoichiometric amount of CaCl2 to the solutions to test its effect on the hydrogel formation. The overall results are not satisfactory, as only the solutions containing gelator B form hydrogels, whereas gelators A and C form very weak hydrogels, even at 2% w/w concentration (Table S1 and Figure S1).

Recently, Adams and co-workers studied the addition of divalent cations to a solution of naphthalenediphenylalanine that forms a rigid, self-supporting hydrogel.49 They found out that the hydrogel strength (measured as G′) reached a maximum at a ratio of calcium to carboxylic acid of approximately 2:1 but that good results may also be obtained with different ratios. Thus, we tested the ability of gelators A–C to form hydrogels with different calcium/carboxylic acid ratios: excellent results were obtained with substoichiometric amounts of calcium chloride (Table 1), with the formation of self-supporting and strong hydrogels, even with 1% w/w gelator concentration, which is the minimum gelator concentration (Figure 2).

Table 1. Physical Properties of Hydrogels Obtained with Gelators A–C and a Substoichiometric Amount of CaCl2.

| gelator (% w/w) | hydrogel | NaOH (equiv) | CaCl2 (equiv) | Tgel (°C) | final pH | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (1) | 7 | 2 | 0.6 | 85a | 7.5 | thixotropic gel |

| A (2) | 8 | 2 | 0.6 | 100a | 7.5 | thixotropic gel |

| B (1) | 9 | 1 | 0.3 | 75a | 7.5 | |

| B (2) | 10 | 1 | 0.3 | 75a | 7.5 | |

| C (1) | 11 | 1 | 0.3 | 50a | 7.5 | thixotropic gel |

| C (2) | 12 | 1 | 0.3 | 60a | 7.5 | thixotropic gel |

Syneresis occurs on heating.

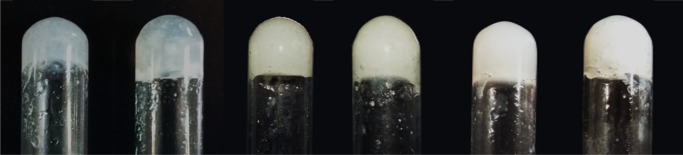

Figure 2.

Photographs of the samples of hydrogels 7–12 prepared with gelators A–C and of hydrogels obtained with gelators A–C and a substoichiometric amount of CaCl2.

Hydrogels 7, 8, 11, and 12 show also a thixotropic behavior, as they become liquid if a shear stress is applied and then they quickly recover the solid form on resting, with no variation of the Tgel.

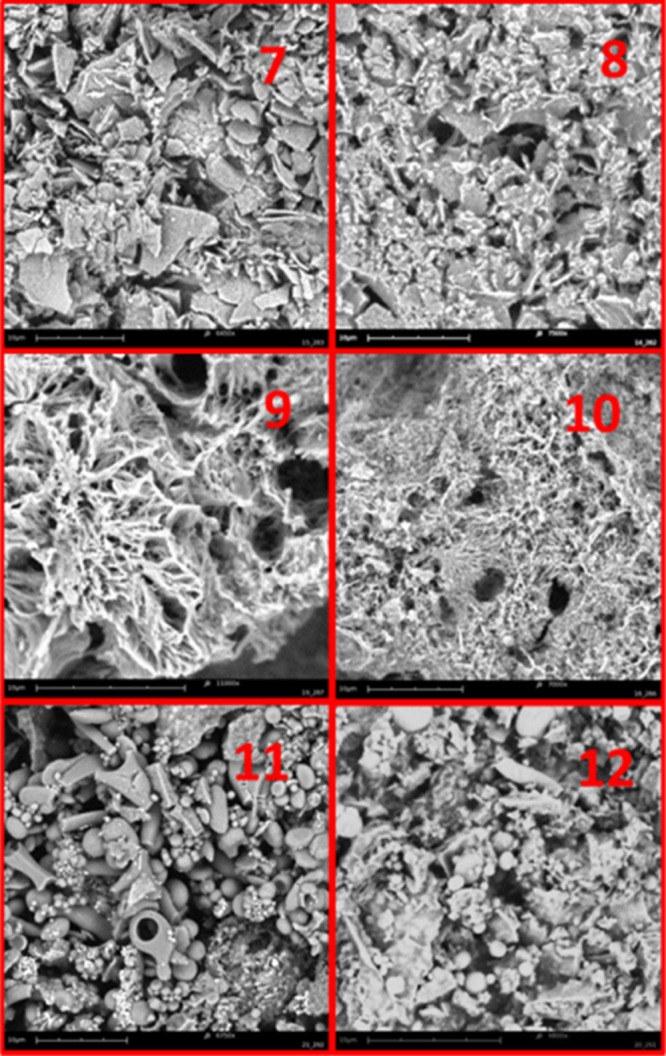

More information on the nature of hydrogels 7–12 was obtained by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of aerogels prepared by freeze-drying these samples (Figure 3). Thixotropic gels 7, 8, 11, and 12 furnish aerogels characterized by complex patterns with a rough orientation, whereas hydrogels 9 and 10 furnish aerogels characterized by dense fibrous networks. These observations suggest that when the hydrogel results from the formation of dense fibrous networks, the application of a shear stress destroys these networks, which hardly get quickly reorganized; thus, it inhibits the hydrogel reformation.

Figure 3.

SEM images of the samples of xerogel obtained by freeze-drying the samples of hydrogels 7–12.

To analyze the viscoelastic behavior of the most promising hydrogels, 8, 10, and 12, rheological analyses have been performed to evaluate them in terms of storage and loss moduli (G′ and G″, respectively) (Table 2 and Figure S2). All of the analyzed hydrogels are characterized by a “solidlike” behavior, that is, the storage modulus is approximately an order of magnitude higher than that of the loss component. Furthermore, the values of G′ and G″ obtained through strain sweep experiments well-correlate with the previously performed Tgel analysis, confirming that the stiffer gel among the obtained ones is hydrogel 8, followed by hydrogels 10 and 12.

Table 2. Storage (G′) and Loss (G″) Moduli of the Hydrogels Obtained Starting from Gelators 8, 10, and 12.

| hydrogel | G′ (Pa) | G″ (Pa) | Tgel (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 44 000 | 4000 | 100 |

| 10 | 17 000 | 2500 | 75 |

| 12 | 10 500 | 1000 | 60 |

Frequency sweep analysis (Figure S2) pointed out that for all of the obtained hydrogels both G′ and G″ were almost independent from the frequency in the range from 0.1 to 100 rad/s (always with G′ > G″), confirming the previously discussed solidlike rheological behavior for the analyzed hydrogels.

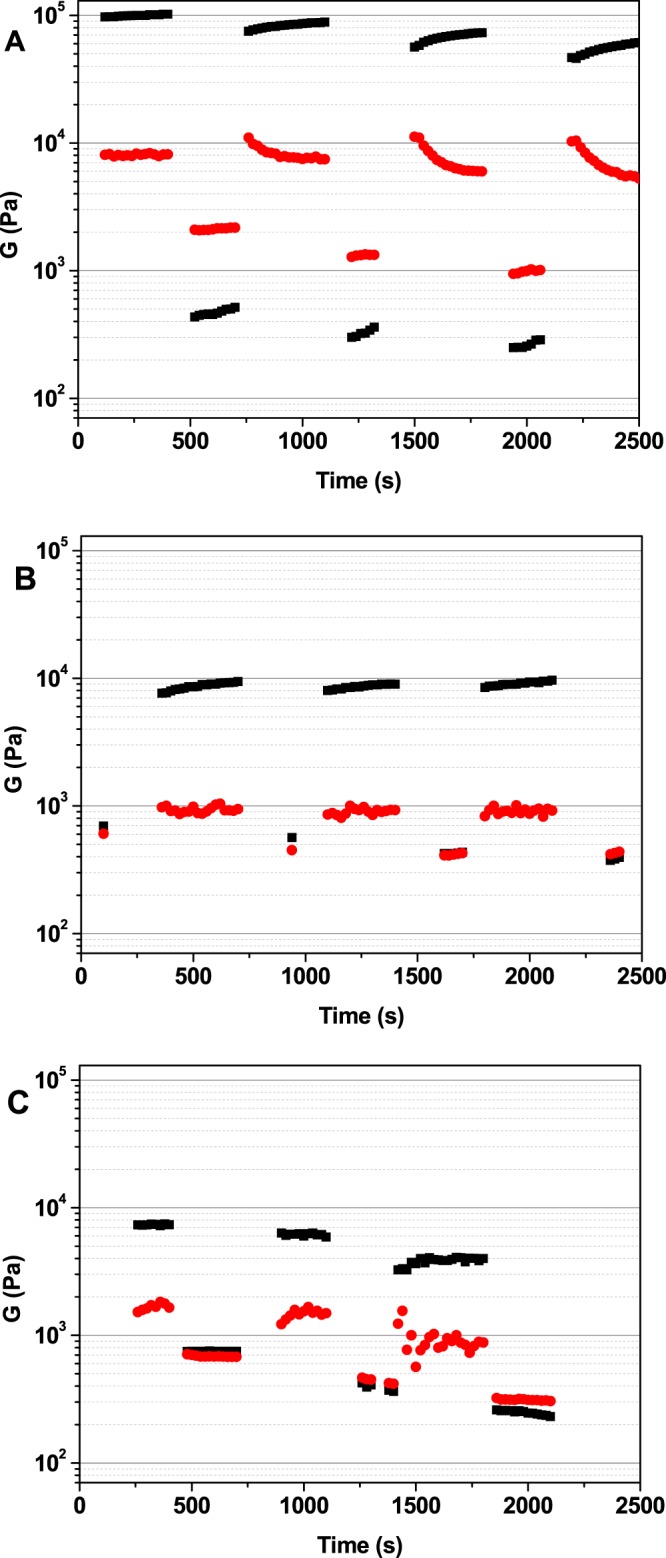

Step strain experiments were performed to check the thixotropic behavior of 8, 10, and 12 at the molecular level. The strain values within and above the linear viscoelastic (LVE) region were consecutively applied to the hydrogels, which lose their solidlike behavior (G′ < G″) when the strain is applied above their LVE region and quickly go back to a solidlike state (G′ > G″) when the strain is applied to the LVE region of the hydrogels (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Values of storage moduli G′ (■) and loss moduli G″ (red ●) recorded during a step strain experiment performed on hydrogels (A) 8, (B) 10, and (C) 12.

The results observed for hydrogels 8 and 12 show that they are characterized by a great capability to recover the gel-like behavior and confirm their thixotropic properties at the molecular level. In addition, hydrogel 10 is a thixotropic hydrogel from a molecular point of view, although it does not fully recover the solidlike behavior, when the strain level goes back within the LVE region.

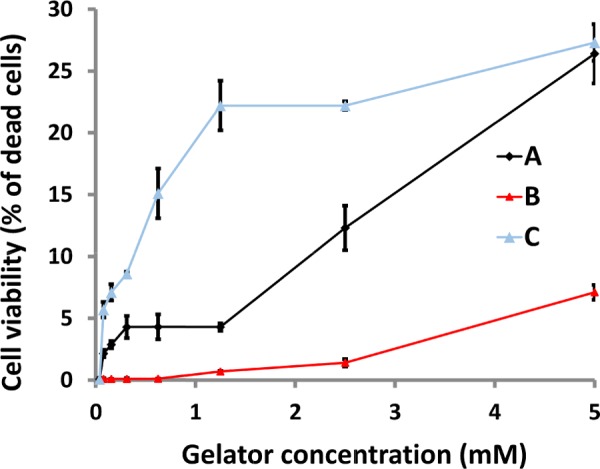

Cytotoxicity and cytocompatibility studies were carried out on diluted solutions of gelators A–C. Human fibroblasts were grown for 24 h in the presence of gelators A–C at increasing concentrations up to 5 mM (about 0.3 w/w concentration), which is always much lower than the concentration needed to form hydrogels.

The toxicity of gelators A–C was evaluated by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay.50,51 The results show a low toxicity of B solutions up to a concentration of 5 mM with a cell viability of 95% with respect to the control. In contrast, the cell viability decreases upon using C and A solutions (72.2 and 72.7% of living cells at a concentration of 5 mM, respectively) after 24 h of incubation (Figure 5). We previously noticed that gelator B tends to form dense fibrous networks, so the very low toxicity could be correlated with the tendency of the gelator to self-assemble. This effect has been recently observed for amyloid precursor proteins (APPs) that exist as soluble oligomers and are extremely neurotoxic.52 Moreover, several studies have shown that the soluble pool of Aβ is better correlated to cognitive decline than the insoluble pool.53,54

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity of gelators A–C measured by the LDH assay on human gingival fibroblast (HGF) cells after 24 h of incubation with increasing gelator concentrations (from 5 μM to 5 mM). Data are expressed as relative percentage compared to control HGFs.

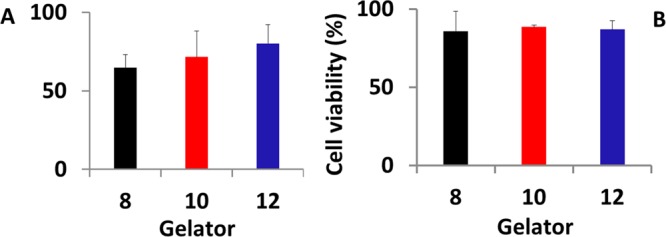

Bearing this preliminary result in mind, we evaluated the behavior of living cells trapped in the hydrogels. The fibroblasts were embedded in 2% hydrogels prepared in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (50 UI/mL), and streptomycin (0.05 mg/mL) under the same conditions as those for 8, 10, and 12. Gelators A–C efficiently promoted the formation of hydrogels from this medium, although it is not pure water, thus showing their versatility in hydrogel formation. This operation was simplified by the hydrogels’ thixotropic behavior: the gels were prepared and shaked to recover the sol state; thereafter, the cells were rapidly embedded and the resulting solution was allowed to stand for 6 h to reform the hydrogels. The overall results show a reduced toxicity of all of the hydrogels, which well-correlate with the 3-D network formation. Thus, the viability did not statistically differ in hydrogels 8 and 10 (compared to that in the previous experiments) after 24 h of culture, whereas the toxicity of 12 drastically decreased. After 7 days of incubation, when the 3-D networks are completely formed and the hydrogels still maintain their shape, the number of living cells increases for the three samples (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Viability of embedded HGFs in hydrogels 8, 10, and 12 after (A) 24 h and (B) 7 days of culture. Data are expressed as relative percentage ± standard deviation compared to control HGFs.

These results are in agreement with our previous observations on gelator solutions and indicate that the toxicity of gelators is completely eliminated when the molecules are self-assembled, showing no substantial differences with the behavior of the most commonly used gelators for pharmaceutical and medical applications (such as gelatin,55−57 alginate,5,7 chitosan,58,59 agarose,14,60,61 and hyaluronate62,63).

Finally, the suitability of the hydrogels for long-term cell culture and therapeutic approaches has been confirmed by the evaluation of the NAD(P)H-dependent cellular oxidoreductase mitochondrial enzymes’ activity using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) as a substrate: the presence of formazan crystals in the cells indicates a good cell viability after 7 days of culture (Figure 7), thus confirming that these hydrogels may be used for 3-D cell culture useful in regenerative medicine.

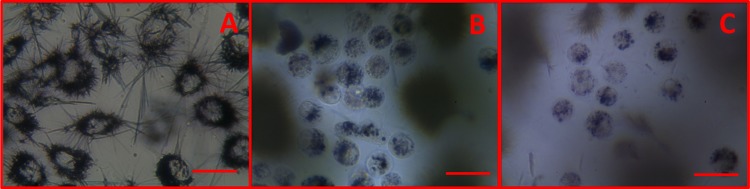

Figure 7.

Microscopic images of HGFs embedded within (A) hydrogel 8, (B) hydrogel 10, and (C) control HGFs after 7 days of culture treated by MTT. Blue formazan crystals are well-visible inside the cell. Cells trapped in hydrogel 12 are not shown as the gel turbidity did not allow us to capture clear images. The bars correspond to 50 μm.

Conclusions

The preparation, characterization, and biological assessment of hydrogels prepared using pseudopepetide gelators, containing the d-Oxd or the d-pGlu moiety and selected amino acids, have been studied and reported. A substoichiometric amount of calcium chloride was used as a trigger, as it allows the formation of strong and thixotropic hydrogels at physiological pH. This behavior was observed at the macroscopic level and confirmed at a molecular level by rheological analyses, which were used to assess the viscoelastic behavior of the most promising hydrogels in terms of storage and loss moduli.

Then, cytotoxicity and cytocompatibility studies were carried out on diluted solutions (up to 5 mM) of gelators A–C, followed by the biocompatibility evaluation of hydrogels 8, 10, and 12. The results show low toxicity of both the gelator solutions and the hydrogels. In addition, after 7 days, when all of the 3-D networks are completely formed, the number of living cells increases in all of the samples and the gelator toxicity is totally eliminated. This result is in agreement with what has been recently observed for the APPs, as the soluble pool of Aβ better correlates with the cognitive decline than the insoluble pool.

Experimental Section

Materials

All chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, VWR, or Iris Biotech and were used as received. Acetonitrile was distilled under inert atmosphere before use. MilliQ water (Millipore, resistivity = 18.2 mΩ cm) was used throughout. DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin (50 UI/mL), and streptomycin (0.05 mg/mL) was purchased by Life Technologies. The LDH kit was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Synthesis of HO-d-Oxd-l-Phe-CO(CH2)7CO-l-Phe-d-Oxd-OH A

Compound A was synthesized from d-Thr, azelaic acid, and Boc-l-Phe-OH following a multistep procedure in solution, reported in ref (26).

Synthesis of Fmoc-l-Tyr-d-Oxd-OH B

Compound B was synthesized from d-Thr and Fmoc-l-Tyr(t-Bu)-OH following a multistep procedure in solution, reported in ref (34).

Synthesis of Fmoc-l-Phe-d-pGlu-OH C

Compound C was synthesized from d-pGlu and Fmoc-l-Phe-OH following a multistep procedure in solution, reported in ref (17).

Conditions for Gel Formation with Gelator A

A portion of gelator A (5–10 mg, depending on the final concentration, ranging from 1 to 2% w/w) was placed in a test tube (diameter: 8 mm), and then, MilliQ water (0.5 mL) and 2 equiv of 1 M aqueous NaOH were added. The mixture was stirred until complete compound dissolution. Different amounts of CaCl2 were added to the solution under rapid stirring (see Tables 1 and S1 for details), and then, the tubes were allowed to stand quiescently until gel formation, which occurred after about 10 min.

Conditions for Gel Formation with Gelator B or C

A portion of gelator B or C (5–10 mg, depending on the final concentration, ranging from 1 to 2% w/w) was placed in a test tube (diameter: 8 mm), then MilliQ water (0.5 mL) and 1 M aqueous NaOH (1 equiv) were added, and the mixture was stirred until sample dissolution. Different amounts of CaCl2 were added to the solution under rapid stirring (see Tables 1 and S1 for details), and then, the tubes were allowed to stand quiescently until gel formation, which occurred after about 10 min.

Conditions for Tgel Determination

Tgel was determined by heating the test tube (diameter: 8 mm) containing the hydrogel sample and a glass ball (diameter: 5 mm, weight: 165 mg) on the top of it. When the hydrogel is formed, the ball is suspended atop. The Tgel is the temperature at which the ball starts to penetrate inside the gel. Some hydrogel samples melt, producing a clear solution, whereas in other cases, the gelator shrinks and water is ejected, as syneresis occurs.

Aerogel Preparation

Some samples of hydrogels 7–12 were freeze-dried using a Benchtop Freeze Dry System LABCONCO 7740030 with the following procedure: the hydrogel (0.5 mL) was prepared in an Eppendorf test tube at room temperature. After 16 h, the samples were immersed in liquid nitrogen for 10 min and then freeze-dried for 24 h in vacuo (0.2 mBar) at −50 °C.

Morphological Analysis

Scanning electron micrographs of the samples were recorded using a Hitachi 6400 field emission gun scanning electron microscope.

Rheology

Rheology experiments were carried out on an Anton Paar rheometer MCR 102 using a parallel plate configuration (25 mm diameter). Experiments were performed at a constant temperature of 23 °C controlled by the integrated Peltier system and a Julabo AWC100 cooling system. To keep the sample hydrated, a solvent trap was used (H-PTD200). The amplitude and frequency sweep analyses were performed with a fixed gap value of 0.5 mm on hydrogel samples prepared directly on the upper plate of the rheometer once the gelation reaction was completed. The samples were prepared the day before the analysis and left overnight at a controlled temperature of 20 °C to complete the gelation process. Oscillatory amplitude sweep experiments (γ: 0.01–100%) were carried out to determine the LVE range at a fixed frequency of 1 rad/s. Once the LVE range of each hydrogel was established, frequency sweep tests were performed (ω: 0.1–100 rad/s) at constant strain within the LVE region of each sample. Thixotropic experiments were conducted on hydrogels 8, 10, and 12 by applying consecutive deformation and recovery steps. The deformation step was performed by applying to the gels a constant strain above the LVE region of each sample for a period of 7 min. The recovery step was performed by keeping the sample at a constant strain within the LVE region for 7 min. The cycles were performed multiple times at a fixed frequency of 1 rad/s.

Isolation and Culture of HGFs

HGFs were obtained from healthy patients subjected to gingivectomy of the molar region. Informed consent was obtained from each patient. Immediately after the removal, the tissues were washed in phosphate buffer, cut in small pieces, and placed in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin (50 UI/mL), and streptomycin (0.05 mg/mL), at 37 °C in a 5% humidified CO2 atmosphere. After the first passage, the HGFs were routinely cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and were not used beyond the fifth passage.

Evaluation of Gelator Cytocompatibility

Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 20 000 cells/cm2. The gelators were solubilized at concentrations from 5 μM to 5 mM in culture media, and cytotoxicity of the compounds was evaluated by measuring the cytosolic LDH activity in the culture supernatants.

The LDH assay was performed after 24 h of incubation using a commercial LDH kit following the manufacturer’s recommendations. LDH is a cytosolic enzyme present in many different cell types. The plasma membrane damage releases LDH into the cell culture media. Extracellular LDH in the media can be quantified by a coupled enzymatic reaction in which LDH catalyzes the conversion of lactate to pyruvate via NAD+ reduction to NADH. Diaphorase then uses NADH to reduce a tetrazolium salt to a red formazan product that can be measured at 490 nm. The level of formazan formation is directly proportional to the amount of LDH released into the medium, which is indicative of the cytotoxicity. To determine total LDH activity, cells from the positive control group were treated with 1% Triton X-100. The optical density in each well was measured using a spectrophotometer microplate reader (model 680; Bio-Rad Lab. Inc., CA) at a wavelength of 490 nm. Each experiment was performed three times, and four replicate cell cultures were analyzed in each experiment.

Cell Seeding and Cytotoxicity Test

Gelators A, B, or C (10 mg) were solubilized in 0.5 mL of DMEM supplemented with 1% FCS, penicillin (50 UI/mL), and streptomycin (0.05 mg/mL) under sonication at room temperature during 15 min. Once liquid solutions were obtained, 1 M NaOH (2 equiv for A and 1 equiv for B or C) followed by 0.2 M CaCl2 (0.6 equiv for A and 0.3 equiv for B or C) were added to the solutions, with the immediate formation of hydrogels that rested at room temperature without agitation for 30 min. To allow cell seeding, the gel was heated at 37 °C and thoroughly mixed with 100 μL of cell suspension at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/mL of gel and the gel/cell systems were transferred into different wells of a 12-well plate and maintained under controlled atmosphere (5% CO2, 37 °C) for 24 h and 7 days. After each experimental point, the gel/cell constructs were transferred into 1.5 mL vials, centrifuged at 160g for 10 min, and the supernatants were used to check the cytotoxicity by the LDH assay described above. Light microscopy observation of living cells was performed using the MTT assay. After each experimental point, 100 μL of a MTT stock solution was added into each well to reach a final concentration of 1 mM. After that, the samples were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in a controlled atmosphere and the resulting blue formazan crystals were observed in living cells.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (PRIN 2015 project 20157WW5EH) and Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00322.

Physical properties of the hydrogels obtained with gelators A–C and a stoichiometric amount of CaCl2; photographs of the samples of hydrogels prepared with gelators A–C and CaCl2 in different concentrations; strain dependence and frequency dependence of the storage modulus and loss modulus for hydrogels 8, 10, and 12 (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ N.Z. and S.F. contributed equally.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Toh W. S.; Loh X. J. Advances in hydrogel delivery systems for tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2015, 45, 690–697. 10.1016/j.msec.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zustiak S. P.; Wei Y.; Leach J. B. Protein-hydrogel interactions in tissue engineering: mechanisms and applications. Tissue Eng., Part B 2013, 19, 160–171. 10.1089/ten.teb.2012.0458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Battig M. R.; Chen N.; Gaddes E. R.; Duncan K. L.; Wang Y. Chimeric aptamer-gelatin hydrogels as an extracellular matrix mimic for loading cells and growth factors. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 778–787. 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b01511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage W.; Vats K.; Rajbhandary A.; Benoit D. S. W.; Nilsson B. L. Multicomponent dipeptide hydrogels as extracellular matrix-mimetic scaffolds for cell culture applications. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 11260–11263. 10.1039/C5CC03162A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty S.; Wu Y.; Chakraborty N.; Mohanty P.; Ghosh G. Impact of alginate concentration on the viability, cryostorage, and angiogenic activity of encapsulated fibroblasts. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2016, 65, 269–277. 10.1016/j.msec.2016.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasperini L.; Mano J. F.; Reis R. L. Natural polymers for the microencapsulation of cells. J. R. Soc., Interface 2014, 11, 20140817 10.1098/rsif.2014.0817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focaroli S.; Teti G.; Salvatore V.; Orienti I.; Falconi M. Calcium/cobalt alginateb as functional scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 2030478 10.1155/2016/2030478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X.; Zhou J.; Shi J.; Xu B. Supramolecular hydrogelators and hydrogels: from soft matter to molecular biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 13165–13307. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawarna V.; Ali M.; Jowitt T. A.; Miller A. F.; Saiani A.; Gough J. E.; Ulijn R. V. Nanostructured hydrogels for three-dimensional cell culture through self-assembly of fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-dipeptides. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 611–614. 10.1002/adma.200501522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G.; Yang Z.; Zhang R.; Li L.; Fan Y.; Kuang Y.; Gao Y.; Wang T.; Lu W. W.; Xu B. Supramolecular hydrogel of a D-amino acid dipeptide for controlled drug release in vivo. Langmuir 2009, 25, 8419–8422. 10.1021/la804271d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y. F.; Devgun J. M.; Collier J. H. Fibrillized peptide microgels for cell encapsulation and 3D cell culture. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 6005–6011. 10.1039/c1sm05504f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. P.; Nagaraj A. K.; Fox E. K.; Rudra J. S.; Devgun J. M.; Collier J. H. Co-assembling peptides as defined matrices for endothelial cells. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2400–2410. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H. T.; Shek P. N. Novel wound sealants: biomaterials and applications. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2010, 7, 639–659. 10.1586/erd.10.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya M. V.; Kumar R. A.; Sivashanmugam A.; Nair S. V.; Jayakumar R. Injectable amorphous chitin-agarose composite hydrogels for biomedical applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2015, 6, 849–862. 10.3390/jfb6030849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H.; Jo S.; Mikos A. G. Biomimetic materials for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4353–4364. 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vlierberghe S.; Dubruel P.; Schacht E. Biopolymer-based hydrogels as scaffolds for tissue engineering applications: a review. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1387–1408. 10.1021/bm200083n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D. J. Dipeptide and tripeptide conjugates as low-molecular-weight hydrogelators. Macromol. Biosci. 2011, 11, 160–173. 10.1002/mabi.201000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsedo Y. Low-molecular-weight gelators as base materials for ointments. Gels 2016, 2, 13. 10.3390/gels2020013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci N.; Falini G.; Angelici G.; Tomasini C. Formation of gels in the presence of metal ions. Amino Acids 2011, 41, 609–620. 10.1007/s00726-011-0908-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skilling K. J.; Citossi F.; Bradshaw T. D.; Ashford M.; Kellam B.; Marlow M. Insights into low molecular mass organic gelators: a focus on drug delivery and tissue engineering applications. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 237–256. 10.1039/C3SM52244J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milli L.; Castellucci N.; Tomasini C. Turning around the L-Phe-D-Oxd moiety for a versatile low-molecular-weight gelator. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 5954–5961. 10.1002/ejoc.201402787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini C.; Castellucci N. Peptides and peptidomimetics that behave as low molecular weight gelators. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 156–172. 10.1039/C2CS35284B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka T.; Maeda T.; Hotta A. Effects of salt concentrations of the aqueous peptide-amphiphile solutions on the sol-gel transitions, the gelation speed, and the gel characteristics. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 11537–11545. 10.1021/jp5031569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; McDonald T. O.; Adams D. J. Salt-induced hydrogels from functionalised-dipeptides. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 8714–8720. 10.1039/c3ra40938d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D. J.; Butler M. F.; Frith W. J.; Kirkland M.; Mullen L.; Sanderson P. A New method for maintaining homogeneity during liquid–hydrogel transitions using low molecular weight hydrogelators. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 1856–1862. 10.1039/b901556f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D. J.; Mullen L. M.; Berta M.; Chen L.; Frith W. J. Relationship between molecular structure, gelation behaviour and gel properties of Fmoc-dipeptides. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 1971–1980. 10.1039/b921863g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fichman G.; Guterman T.; Adler-abramovich L.; Gazit E. Synergetic functional properties of two-component single amino acid-based hydrogels. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 8105–8112. 10.1039/C5CE01051A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Liang G.; Xu B. Enzymatic hydrogelation of small molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 315–326. 10.1021/ar7001914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik A.; Paikar A.; Haldar D. Sonication-induced instant fibrillation and fluorescent labeling of tripeptide fibers. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 53886–53892. 10.1039/C5RA07864D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci N.; Angelici G.; Falini G.; Monari M.; Tomasini C. L-Phe-D-Oxd: A privileged scaffold for the formation of supramolecular materials. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 3082–3088. 10.1002/ejoc.201001643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z.; Yang Y.; Ren Q.; Chen X.; Shao Z. Injectable thixotropic hydrogel comprising regenerated silk fibroin and hydroxypropylcellulose. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 2875–2883. 10.1039/c2sm06984a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Ling S.; Wang S.; Chen X.; Shao Z. Thixotropic silk nanofibril-based hydrogel with extracellular matrix-like structure. Biomater. Sci. 2014, 2, 1338–1342. 10.1039/C4BM00214H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pek Y. S.; Wan A. C. A.; Ying J. Y. The effect of matrix stiffness on mesenchymal stem cell differentiation in a 3D thixotropic gel. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 385–391. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Zhou F.; Wen Y.; Liu K.; Chen L.; Mao Y.; Yang S.; Yi T. (-)-Menthol based thixotropic hydrogel and its application as a universal antibacterial carrier. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 3077–3085. 10.1039/c3sm52999a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshizawa H.; Minemura Y.; Yoshikawa K.; Suzuki M.; Hanabusa K. Thixotropic hydrogelators based on a cyclo(dipeptide) derivative. Langmuir 2013, 29, 14666–14673. 10.1021/la402333h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R. G. The Past, Present, and future of molecular gels. What is the status of the field, and where is it going?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7519–7530. 10.1021/ja503363v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Greenfield Ma; Mata A.; Palmer L. C.; Bitton R.; Mantei J. R.; Aparicio C.; de la Cruz M. O.; Stupp S. I. A Self-assembly pathway to aligned monodomain gels. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 594–601. 10.1038/nmat2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield M. A.; Hoffman J. R.; De La Cruz M. O.; Stupp S. I. Tunable mechanics of peptide nanofiber gels. Langmuir 2010, 26, 3641–3647. 10.1021/la9030969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanna N.; Merlettini A.; Tatulli G.; Milli L.; Focarete M. L.; Tomasini C. Hydrogelation induced by Fmoc-protected peptidomimetics. Langmuir 2015, 31, 12240–12250. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b02780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milli L.; Zanna N.; Merlettini A.; Di Giosia M.; Calvaresi M.; Focarete M. L.; Tomasini C. Pseudopeptide-based hydrogels trapping Methylene Blue and Eosin Y. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 12106–12112. 10.1002/chem.201601861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanna N.; Merlettini A.; Tomasini C. Self-healing hydrogels triggered by amino acids. Org. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 1699–1704. 10.1039/C6QO00476H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini C.; Villa M. Pyroglutamic acid as a pseudoproline moiety: a facile method for its introduction into polypeptide chains. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 5211–5214. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)00981-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucarini S.; Tomasini C. Synthesis of oligomers of trans-(4S,5R)-4-carboxybenzyl 5-methyl oxazolidin-2-one: an approach to new foldamers. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 727–732. 10.1021/jo005583+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelici G.; Falini G.; Hofmann H. -J; Huster D.; Monari M.; Tomasini C. A fiberlike peptide material stabilized by single intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8075–8078. 10.1002/anie.200802587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelici G.; Falini G.; Hofmann H. J.; Huster D.; Monari M.; Tomasini C. Nanofibers from oxazolidi-2-one containing hybrid foldamers: what is the right molecular size?. Chem. - Eur. J. 2009, 15, 8037–8048. 10.1002/chem.200900185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon Y. S.; Lei J.; Kim J. H. Dye adsorption characteristics of alginate/polyaspartate hydrogels. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2008, 14, 726–731. 10.1016/j.jiec.2008.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Çelik E.; Bayram C.; Akçapınar R.; Türk M.; Denkbaş E. B. The effect of calcium chloride concentration on alginate/Fmoc-diphenylalanine hydrogel networks. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2016, 66, 221–229. 10.1016/j.msec.2016.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C.; Tang M. C.; Wu C. S.; Simon T.; Ko F. H. New synthesis route of hydrogel through a bioinspired supramolecular approach: gelation, binding interaction, and in vitro dressing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 19306–19315. 10.1021/acsami.5b05360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Pont G.; Morris K.; Lotze G.; Squires A.; Serpell L. C.; Adams D. J. Salt-induced hydrogelation of functionalised-dipeptides at high pH. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 12071–12073. 10.1039/c1cc15474e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker T.; Lohmann-Matthes M.-L. A Quick and simple method for the quantitation of lactate dehydrogenase release in measurements of cellular cytotoxicity and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) activity. J. Immunol. Methods 1988, 115, 61–69. 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand C.; Bour J. M.; Jacob C.; Capiaumont J.; Martial A.; Marc A.; Wudtke M.; Kretzmer G.; Demangel C.; Duval D.; Hache J. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity of the number of dead cells in the medium of cultured eukaryotic cells as marker. J. Biotechnol. 1992, 25, 231–243. 10.1016/0168-1656(92)90158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum W. I. Why Alzheimer trials fail: removing soluble oligomeric β amyloid is essential, inconsistent, and difficult. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 969–974. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean C. A.; Cherny R. A.; Fraser F. W.; Fuller S. J.; Smith M. J.; Beyreuther K.; Bush A. I.; Masters C. L. Soluble pool of Aβ amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 46, 860–866. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. W.; Pasternak J. F.; Kuo H.; Ristic H.; Lambert M. P.; Chromy B.; Viola K. L.; Klein W. L.; Stine W. B.; Krafft G. A.; Trommer B. L. Soluble oligomers of β amyloid (1–42) inhibit long-term potentiation but not long-term depression in rat dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 2002, 924, 133–140. 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)03058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focaroli S.; Teti G.; Salvatore V.; Durante S.; Belmonte M. M.; Giardino R.; Mazzotti A.; Bigi A.; Falconi M. Chondrogenic differentiation of human adipose mesenchimal stem cells: influence of a biomimetic gelatin genipin crosslinked porous scaffold. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2014, 77, 928–934. 10.1002/jemt.22417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey G.; Mittapelly N.; Pant A.; Sharma S.; Singh P.; Banala V. T.; Trivedi R.; Shukla P. K.; Mishra P. R. Dual functioning microspheres embedded crosslinked gelatin cryogels for therapeutic intervention in osteomyelitis and associated bone loss. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 91, 105–113. 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H. J.; Shin S. R.; Cha J. M.; Lee S.-H; Kim J.-H; Do J. T.; Song H.; Bae H. Cold water fish gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel for tissue engineering application. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0163902 10.1371/journal.pone.0163902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair M. B.; Baranwal G.; Vijayan P.; Keyan K. S.; Jayakumar R. Composite hydrogel of chitosan-poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-valerate) with chondroitin sulfate nanoparticles for nucleus pulposus tissue engineering. Colloids Surf., B 2015, 136, 84–92. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda D. G.; Malmonge S. M.; Campos D. M.; Attik N. G.; Grosgogeat B.; Gritsch K. A Chitosan-hyaluronic acid hydrogel scaffold for periodontal tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part B 2016, 1691. 10.1002/jbm.b.33516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puetzer J.; Williams J.; Gillies A.; Bernacki S.; Loboa E. G. The effects of cyclic hydrostatic pressure on chondrogenesis and viability of human adipose- and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in three-dimensional agarose constructs. Tissue Eng., Part A 2013, 19, 299–306. 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz C.; Leicht U.; Drosse I.; Ulrich V.; Luibl V.; Schieker M.; Röcken M. Characterization of adipose-derived equine and canine mesenchymal stem cells after incubation in agarose-hydrogel. Vet. Res. Commun. 2011, 35, 487–499. 10.1007/s11259-011-9492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heris H. K.; Daoud J.; Sheibani S.; Vali H.; Tabrizian M.; Mongeau L. Investigation of the viability, adhesion, and migration of human fibroblasts in a hyaluronic acid/gelatin microgel-reinforced composite hydrogel for vocal fold tissue regeneration. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2016, 5, 255–265. 10.1002/adhm.201500370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindborg B. A.; Brekke J. H.; Scott C. M.; Chai Y. W.; Ulrich C.; Sandquist L.; Kokkoli E.; O’Brien T. D. A chitosan-hyaluronan-based hydrogel-hydrocolloid supports in vitro culture and differentiation of human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. Tissue Eng., Part A 2015, 21, 1952–1962. 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.