Abstract

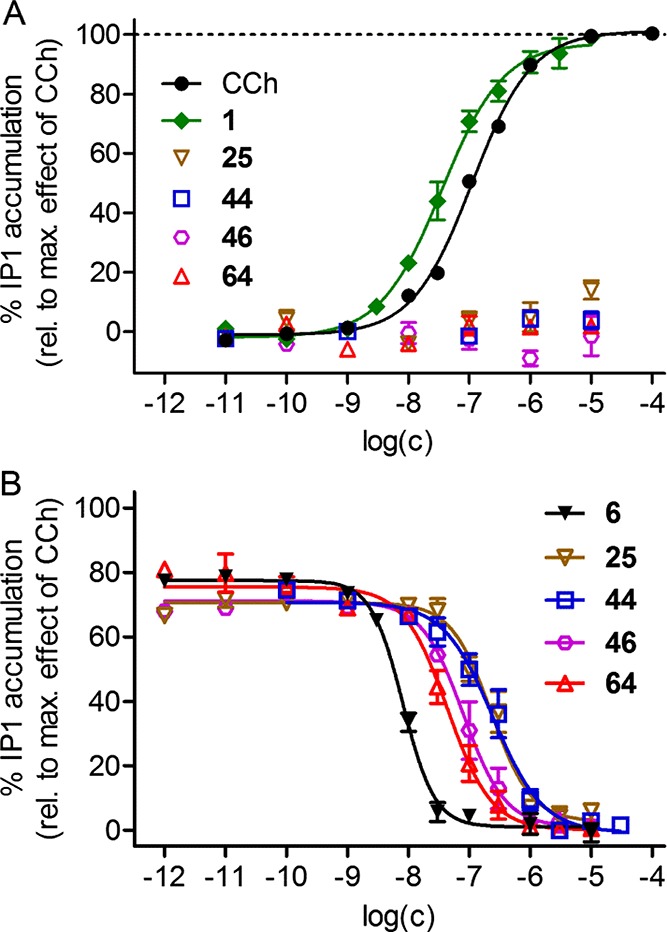

In search for selective ligands for the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (MR) subtype M2, the dimeric ligand approach, that is combining two pharmacophores in one and the same molecule, was pursued. Different types (agonists, antagonists, orthosteric, and allosteric) of monomeric MR ligands were combined by various linkers with a dibenzodiazepinone-type MR antagonist, affording five types of heterodimeric compounds (“DIBA-xanomeline,” “DIBA-TBPB,” “DIBA-77-LH-28-1,” “DIBA-propantheline,” and “DIBA-4-DAMP”), which showed high M2R affinities (pKi > 8.3). The heterodimeric ligand UR-SK75 (46) exhibited the highest M2R affinity and selectivity [pKi (M1R–M5R): 8.84, 10.14, 7.88, 8.59, and 7.47]. Two tritium-labeled dimeric derivatives (“DIBA-xanomeline”-type: [3H]UR-SK71 ([3H]44) and “DIBA-TBPB”-type: [3H]UR-SK59 ([3H]64)) were prepared to investigate their binding modes at hM2R. Saturation-binding experiments showed that these compounds address the orthosteric binding site of the M2R. The investigation of the effect of various allosteric MR modulators [gallamine (13), W84 (14), and LY2119620 (15)] on the equilibrium (13–15) or saturation (14) binding of [3H]64 suggested a competitive mechanism between [3H]64 and the investigated allosteric ligands, and consequently a dualsteric binding mode of 64 at the M2R.

1. Introduction

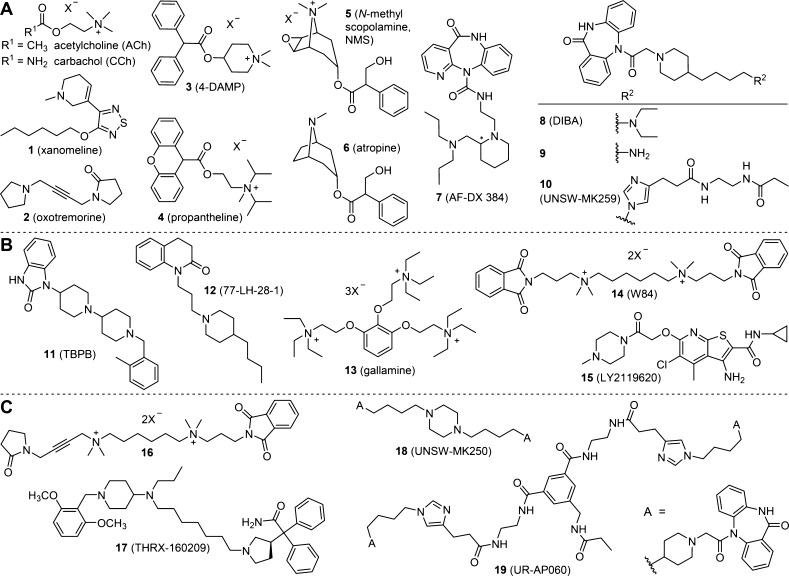

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (MRs) belong to the class A G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily and comprise five receptor subtypes in humans (designated M1R–M5R).1−4 Whereas the M1R, M3R, and M5R receptors were reported to couple with Gq proteins, the M2R and M4R receptors bind to Gi/o proteins.5 MRs represent interesting drug targets, for instance, for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia.6,7 Because of the high conservation of the orthosteric (acetylcholine) binding site,8−10 there is lack of highly subtype selective (orthosteric) ligands, hampering therapeutic approaches such as the treatment of cognitive decline by centrally acting selective M1R agonists or M2R antagonists.11 However, in addition to the orthosteric binding pocket, MRs were reported to exhibit distinct allosteric binding sites, which are less conserved and can potentially be exploited to develop subtype selective ligands.12−17 The M2R was the first GPCR described to be subjected to allosteric modulation,18−20 and several dualsteric M2R ligands (e.g., 7(21) and 10,22,23Figure 1A) and allosteric M2R modulators (e.g., 13,2014,18 and 15,24,25Figure 1B) were identified.

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of the described MR agonists (ACh, CCh, 1, and 2) and antagonists (3–10). The M2R binding poses of compounds 7 and 10 were reported to overlap in part with the binding pose of allosteric M2R modulator 14.21,23 (B) Structures of the selected allosteric MR ligands (compounds 11–15). (C) Structures of heterodimeric ligands 16 and 17 as well as homodimeric MR ligands 18 and 19, the latter suggested to exhibit a dualsteric binding mode at the M2R.23

Dimerization of GPCR ligands can result in an increased receptor affinity and improved selectivity.26,27 Bivalent (dimeric) ligands were described for various GPCRs, such as opioid,28 histamine,29,30 dopamine,31−33 adenosine,33−35 and neuropeptide Y36−38 receptors, not least to investigate receptor dimerization. Likewise, the design of dualsteric (bitopic) ligands, that is, hybrid derivatives that simultaneously address the orthosteric and allosteric sites of one and the same receptor protomer, represents an approach toward improved subtype selectivity.19,39−42 For example, rationally designed hybrid MR ligands derived from the orthosteric agonist oxotremorine (2) and hexamethonium-like allosteric modulators (e.g., compound 16, Figure 1C) showed increased subtype selectivity compared to 2.43 Similarily, the MR ligand THRX-160209 (compound 17, Figure 1C) was reported to exhibit a higher M2R affinity and selectivity than the corresponding monovalent ligands and was suggested to bind to the M2 receptor in a multivalent manner.44

Pyridobenzodiazepinone derivative 7 and the structurally closely related dibenzodiazepinone derivative 8 (Figure 1A) represent tricyclic M2R-preferring MR antagonists.45,46 Tränkle et al. suggested a dualsteric binding mode of 7 at the M2 receptor,21 and a hybrid ligand formed of 7 and allosteric modulator 14 was reported to show a pronounced positive cooperativity with 5, pointing at a new way for the development of allosteric enhancers.47,48

This study was aimed at the design, synthesis, and pharmacological evaluation of heterodimeric MR ligands derived from 8, comprising five combinations of 8 with reported orthosteric or allosteric MR ligands: “8–xanomeline (1),” “8–TBPB (11),” “8–77-LH-28-1 (12),” “8–4-DAMP (3),” and “8–propantheline (4).” Xanomeline (1) (cf. Figure 1A) is a M1 and M4 receptor preferring MR agonist.49 Compound 11 (cf. Figure 1B) was reported to selectively activate M1 receptors through an allosteric mechanism, as shown by mutagenesis and molecular pharmacology studies;50−52 in other reports, 11 was described as a bitopic M1R ligand.53 Likewise, compound 12 (cf. Figure 1B) was suggested to be a bitopic M1R ligand.54 MR antagonists 3 and 4 (cf. Figure 1A) are nonselective orthosteric MR antagonists with high affinities [Ki (3, M1R–M5R): 0.52–3.80 nM and Ki (4, M1R–M4R): 0.057–0.33 nM].45,55 In addition to the heterodimeric ligands, one monomeric and four homodimeric ligands derived from xanomeline, one monomeric and two homodimeric ligands derived from 8, and a monomeric ligand derived from 11 were prepared as reference compounds. Furthermore, two radiolabeled heterodimeric ligands (types “8–11” and “8–1”) were prepared and characterized by saturation binding [including experiments in the presence of allosteric modulators (Schild-like analysis)], kinetic investigations, and competition-binding studies.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

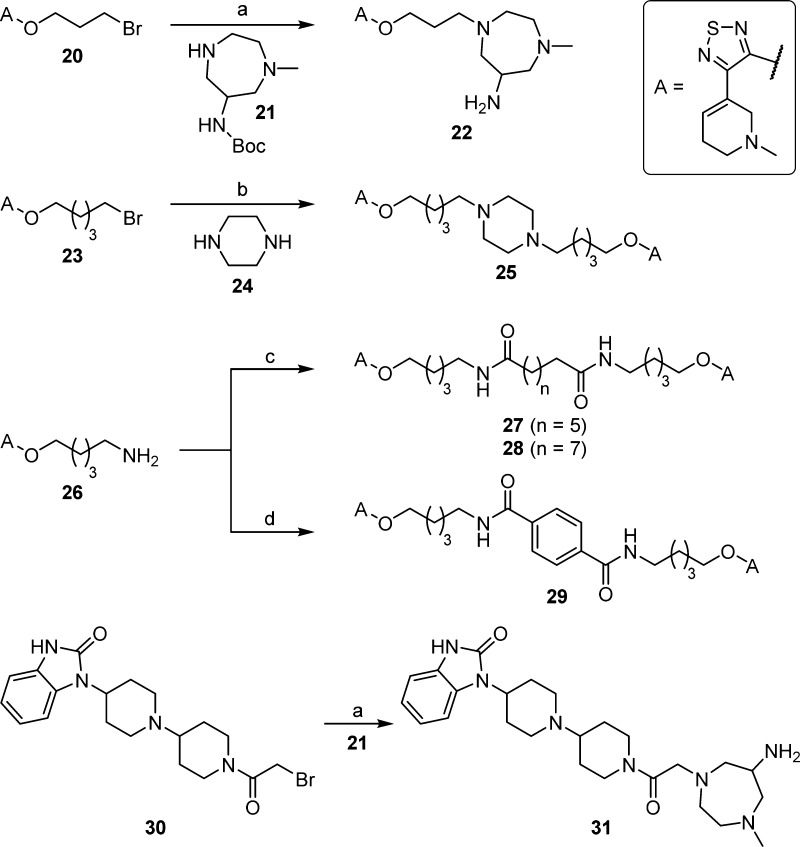

Monomeric reference compound 22 and homodimeric xanomeline-derived ligand 25 were prepared by N-alkylation of homopiperazine derivative 21 using bromide 20 [followed by removal of the tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) group] and by alkylation of piperazine (24) using bromide 23, respectively (Scheme 1). Treatment of amine 26 with octanedioyl dichloride or decanedioyl dichloride in the presence of triethylamine yielded homodimeric xanomeline-type compounds 27 and 28, respectively. Likewise, amidation of terephthalic acid with amine 26, using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC)/1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt) as coupling reagent, afforded homodimeric ligand 29 containing a rigid central linker moiety. N-alkylation of 21 using bromide 30, followed by removal of the Boc group, afforded TBPB derivative 31 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Xanomeline Derivatives 22, 25, and 27–29 as well as TBPB Derivative 31.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (1) K2CO3, MeCN, microwave 110 °C, 30 min; (2) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/CH2Cl2 1:4 v/v, room temperature (rt), 8 h, 66% (22), 20% (31); (b) K2CO3, MeCN, microwave 110 °C, 30 min, 22%; (c) octanedioyl dichloride or decanedioyl dichloride, triethylamine, tetrahydrofuran (THF), 0 °C/rt, overnight, 39% (27), 65% (28); (d) terephthalic acid, EDC, HOBt, dimethylformamide (DMF), rt, overnight, 26%.

The “8–11” type heterodimeric ligand 34 was prepared by N-alkylation of compound 32 using bromide 33; N-alkylation of 21 using 33, followed by removal of the Boc group yielded monomeric reference compound 35 (Scheme 2). Likewise, N-alkylation of piperazine derivatives 36 and 37, using bromide 33, gave the “8–4” type heterodimeric ligands 38 and 39. The “8–1” type heterodimeric ligand 43 was prepared through N-alkylation of compound 40 by applying a mixture of bromides 20 and 33, followed by Boc-deprotection (Scheme 2). Homodimeric ligand 41,23 obtained as a “byproduct” (after Boc-deprotection), was isolated as well. Compound 41 was recently used as an amine precursor for the preparation of a tritium-labeled homodimeric MR ligand.23 Amine 43 was propionylated to give congener 44. The “8–1” type ligand 46 was obtained by N-alkylation of 45 by bromide 33 (Scheme 2). The “8–3” type heterodimeric ligand 48 and the “8–12” type ligand 50 were synthesized by alkylation of compound 47 using bromide 33 and by alkylation of amine 9(22) (cf. Figure 1A) using bromide 49, respectively (Scheme 2). Treatment of 40 with a mixture of bromides 30 and 33, followed by Boc-deprotection, gave the “8–11” type heterodimeric ligand 51, which contains a rigid homopiperazine moiety in between the pharmacophores. As in the case of the synthesis of 43, homodimeric “byproduct” 41 was isolated. Propionylation of 51 gave congener 52 (Scheme 2). Homodimeric ligand 54 was obtained by treating an excess of compound 47 with bromide 53 (Scheme 2). Regarding the syntheses of 43 and 51, it should be mentioned that the respective non-DIBA type homodimeric ligands, resulting from a double alkylation of 40 with bromides 20 or 30, were formed as well, but were not isolated because of interference with other impurities [preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)].

Scheme 2. Synthesis of DIBA (8)-Derived Heterodimeric Ligands 34, 38, 39, 43, 44, 46, 48, and 50–52, Monomeric Dibenzodiazepinone Derivative 35, and 4-DAMP (3)-Derived Homodimeric Ligand 54.

Reagents and conditions: (a) K2CO3, MeCN, reflux, 3–6 h, 57% (34), 51% (38), 38% (39), 41% (46), 27% (48); (b) (1) K2CO3, MeCN, reflux (3 h or overnight) or microwave 110 °C (30 min); (2) TFA/CH2Cl2/H2O 10:10:1 v/v/v, rt, 2 h, 12% (35), 17% (43), 12% (51); (c) diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), DMF, rt, 2 h, 95% (44), 96% (52); (d) NaI, K2CO3, MeCN, reflux, 3 h, 52%; (e) K2CO3, MeCN, microwave 110 °C, 45 min, 23%.

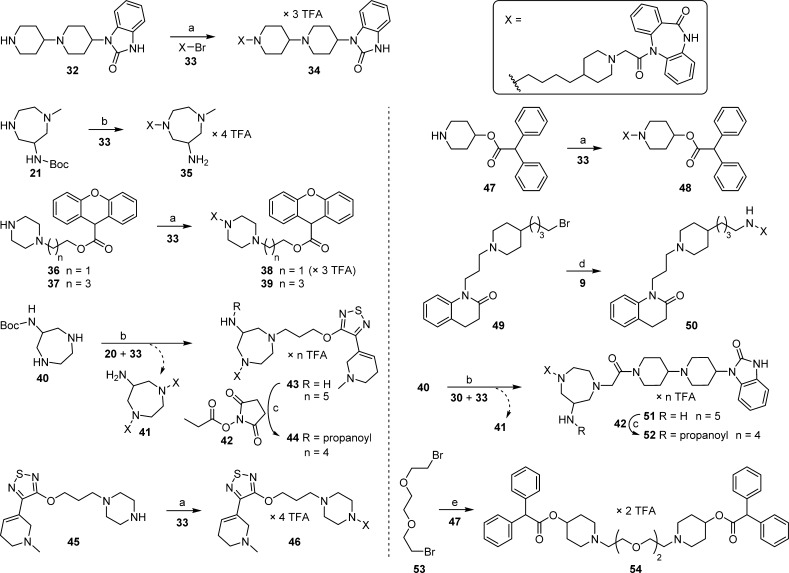

Amidation of isophthalic acid derivative 57 by applying a mixture of amines 55 and 56, followed by Boc-deprotection, afforded heterodimeric ligand 60 and homodimeric ligand 58 (Scheme 3). Propionylation of 58 and 60 gave congeners 59 and 61, respectively. By analogy, heterodimeric ligands 63, 66, 69, and 72 were obtained by amidation of 57 using the amine mixtures 55/62, 55/65, 55/68, and 55/71, respectively, and subsequent Boc-deprotection (Scheme 3). Propionylation of 63, 66, and 69 at the central linker moiety afforded propionamide congeners 64, 67, and 70. It should be noted that the respective non-DIBA type homodimeric ligands, generated by double amidation of 57 with amines 56, 62, 65, 68, or 71, were formed but were not isolated (cf. Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Dibenzodiazepinone-Type Homo- or Heterodimeric Ligands 58–61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, and 72.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (1) 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium, HOBt, DIPEA, DMF, 60 °C, 3 h; (2) TFA/CH2Cl2/H2O 10:10:1 v/v/v, rt, 2 h, 8% (58), 16% (60), 10% (63), 28% (66), 15% (69), 4% (72); (b) DIPEA, DMF, rt, 2 h, 79% (59), 89% (61), 88% (64), 83% (67), 86% (70).

2.2. Competition Binding at the Human MR Subtypes M1–5 with [3H]N-Methylscopolamine ([3H]5) as the Radioligand

2.2.1. M2R Affinity

M2R receptor-binding affinities of monomeric reference ligands 22, 31, and 35, homodimeric ligands 54 (type “3–3”), 58, 59 (type “8–8”), and 25, 27–29 (type “1–1”), as well as heterodimeric ligands 43, 44, 46, 60, and 61 (type “8–1”), 34, 51, 52, 63, and 64 (type “8–11”), 50 and 72 (type “8–12”), 38, 39, 69, and 70 (type “8–4”), and 48, 66, and 67 (type “8–3”) were determined at live CHO-hM2R cells in equilibrium-binding experiments using the MR antagonist [3H]5 as the orthosterically binding radioligand. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. MR Affinities (pKi Values) of Monomeric Reference Compounds 22, 31, and 35, Homodimeric Ligands 25, 27–29, 54, 58, and 59, as well as Heterodimeric Ligands 34, 38, 39, 43, 44, 46, 48, 50–52, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, and 72 Obtained from Equilibrium Competition-Binding Studies with [3H]5 at Live CHO-hMxR Cells (x = 1–5).

| M1R |

M2R |

M3R |

M4R |

M5R |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd. | pKi | slopea | pKi | slopea | pKi | slopea | pKi | slopea | pKi | slopea |

| 22 | n.d. | n.d. | 4.90 ± 0.16 | –1.01 ± 0.10 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d |

| 25 | 7.36 ± 0.10 | –1.04 ± 0.07 | 7.75 ± 0.18 | –0.92 ± 0.18 | 7.30 ± 0.02 | –0.95 ± 0.04 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 27 | 8.30 ± 0.08 | –0.89 ± 0.10 | 8.46 ± 0.17 | –0.94 ± 0.08 | 8.14 ± 0.04 | –1.14 ± 0.03 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 28 | 8.41 ± 0.05 | –1.30 ± 0.05 | 8.67 ± 0.11 | –0.84 ± 0.07 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 29 | 7.72 ± 0.13 | –1.15 ± 0.18 | 8.38 ± 0.13 | –0.83 ± 0.06 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 31 | n.d. | n.d. | 5.88 ± 0.29 | –0.87 ± 0.05 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 34 | 8.57 ± 0.05 | –1.13 ± 0.05 | 9.12 ± 0.05 | –1.43 ± 0.20 | 7.01 ± 0.11 | –1.12 ± 0.07 | 7.95 ± 0.50 | –1.18 ± 0.06 | 7.09 ± 0.07 | –1.09 ± 0.20 |

| 35 | 7.26 ± 0.10 | 0.92 ± 0.08 | 8.67 ± 0.03 | –0.87 ± 0.09 | 6.25 ± 0.06 | –0.93 ± 0.20 | 8.00 ± 0.01 | –0.77 ± 0.02b | 6.86 ± 0.17 | –1.09 ± 0.15 |

| 38 | 8.47 ± 0.08 | –1.03 ± 0.12 | 8.82 ± 0.14 | –1.08 ± 0.22 | 8.12 ± 0.05 | –1.36 ± 0.09 | 7.99 ± 0.28 | –0.98 ± 0.12 | 8.47 ± 0.06 | –1.17 ± 0.10 |

| 39 | 7.62 ± 0.19 | –1.40 ± 0.30 | 8.37 ± 0.28 | –1.51 ± 0.26 | 7.01 ± 0.10 | –0.85 ± 0.04 | 7.52 ± 0.35 | –1.25 ± 0.10 | 7.03 ± 0.03 | –1.09 ± 0.18 |

| 43 | 8.35 ± 0.07 | –1.47 ± 0.17 | 9.30 ± 0.05 | –2.19 ± 0.06b | 7.21 ± 0.04 | –1.34 ± 0.16 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 44 | 8.39 ± 0.03 | –1.05 ± 0.05 | 9.34 ± 0.03 | –1.14 ± 0.07 | 6.84 ± 0.03 | –0.93 ± 0.04 | 8.24 ± 0.08 | –0.94 ± 0.06 | 7.00 ± 0.09 | –1.21 ± 0.19 |

| 46 | 8.84 ± 0.11 | –1.45 ± 0.02b | 10.14 ± 0.11 | –0.96 ± 0.05 | 7.88 ± 0.06 | –1.17 ± 0.08 | 8.59 ± 0.05 | –1.17 ± 0.04 | 7.47 ± 0.03 | –1.07 ± 0.22 |

| 48 | 7.68 ± 0.12 | –1.03 ± 0.22 | 8.66 ± 0.03 | –1.24 ± 0.22 | 7.46 ± 0.12 | –1.35 ± 0.06b | 8.07 ± 0.19 | –1.17 ± 0.11 | 7.27 ± 0.05 | –1.11 ± 0.10 |

| 50 | 8.40 ± 0.08 | –1.00 ± 0.05 | 9.24 ± 0.11 | –1.38 ± 0.22 | 6.86 ± 0.04 | –1.05 ± 0.09 | 8.48 ± 0.03 | –1.4 ± 0.06 | 7.03 ± 0.07 | –1.01 ± 0.25 |

| 51 | 8.37 ± 0.03 | –1.47 ± 0.05b | 9.16 ± 0.07 | –1.86 ± 0.05b | 7.23 ± 0.06 | –1.05 ± 0.10 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 52 | 7.78 ± 0.08 | –1.82 ± 0.19b | 9.11 ± 0.10 | –1.12 ± 0.15 | 6.23 ± 0.10 | –1.01 ± 0.03 | 8.10 ± 0.11 | –0.85 ± 0.07 | 6.88 ± 0.10 | –1.31 ± 0.10 |

| 54 | 6.59 ± 0.07 | –1.14 ± 0.12 | 6.05 ± 0.06 | –1.33 ± 0.18 | 5.64 ± 0.09 | –1.05 ± 0.34 | 5.63 ± 0.04 | –1.00 ± 0.06 | 5.87 ± 0.25 | –1.35 ± 0.20 |

| 58 | 8.69 ± 0.09 | –2.06 ± 0.19b | 9.83 ± 0.07 | –1.53 ± 0.15 | 7.78 ± 0.05 | –1.27 ± 0.10 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 59 | 8.53 ± 0.08 | –1.75 ± 0.34 | 9.24 ± 0.06 | –1.31 ± 0.09 | 7.89 ± 0.07 | –1.22 ± 0.09 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 60 | 8.80 ± 0.10 | –1.32 ± 0.31 | 9.65 ± 0.15 | –1.79 ± 0.09b | 7.76 ± 0.14 | –1.28 ± 0.04b | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 61 | 8.88 ± 0.08 | –1.61 ± 0.03b | 9.47 ± 0.07 | –2.37 ± 0.15b | 7.87 ± 0.02 | –0.99 ± 0.04 | 8.87 ± 0.08 | –1.14 ± 0.11 | 8.37 ± 0.24 | –1.02 ± 0.11 |

| 63 | 8.79 ± 0.09 | –1.19 ± 0.07 | 9.71 ± 0.08 | –1.37 ± 0.14 | 7.77 ± 0.03 | –1.22 ± 0.05 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 64 | 8.56 ± 0.11 | –1.59 ± 0.15 | 9.44 ± 0.06 | –1.84 ± 0.17b | 7.55 ± 0.04 | –1.40 ± 0.10 | 8.57 ± 0.02 | –1.01 ± 0.04 | 6.96 ± 0.04 | –1.26 ± 0.14 |

| 66 | 8.28 ± 0.05 | –1.32 ± 0.19 | 9.16 ± 0.20 | –1.64 ± 0.23 | 7.20 ± 0.19 | –1.33 ± 0.08 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 67 | 8.38 ± 0.06 | –1.54 ± 0.14 | 8.94 ± 0.07 | –2.14 ± 0.16b | 7.52 ± 0.04 | –1.25 ± 0.09 | 8.50 ± 0.08 | –1.52 ± 0.26 | 7.62 ± 0.06 | –1.51 ± 0.12 |

| 69 | 8.42 ± 0.19 | –1.74 ± 0.19 | 9.17 ± 0.18 | –1.52 ± 0.31 | 7.26 ± 0.22 | –1.23 ± 0.12 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 70 | 8.51 ± 0.13 | –1.10 ± 0.07 | 8.96 ± 0.08 | –2.14 ± 0.18b | 7.72 ± 0.06 | –1.21 ± 0.13 | 8.29 ± 0.02 | –1.41 ± 0.05b | 7.37 ± 0.08 | –1.01 ± 0.12 |

| 72 | 8.52 ± 0.09 | –1.66 ± 0.20 | 9.63 ± 0.03 | –1.31 ± 0.13 | 7.88 ± 0.03 | –1.42 ± 0.09b | 8.39 ± 0.09 | –1.50 ± 0.17 | 7.69 ± 0.33 | –0.85 ± 0.07 |

Curve slope of the four-parameter logistic fit. Presented are mean values ± SEM from three to five independent experiments (each performed in triplicate). Kd values reported previously22/applied concentrations of [3H]5: M1: 0.12/0.2 nM; M2: 0.090/0.2 nM; M3: 0.0895/0.2 nM; M4: 0.040/0.1 nM; and M5: 0.24/0.3 nM.

Slope different from unity (P < 0.05).

All compounds containing a dibenzodiazepinone moiety showed high M2R affinity (pKi > 8.3). Whereas homodimeric derivatives (25, 27–29) of MR agonist 1 exhibited an increased M2R affinity (pKi > 7.7) compared to the parent compound (pKi of 1: 6.55, see Table 3); the opposite was found in the case of MR antagonist 3 [pKi = 7.09 ± 0.04, mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from two independent experiments] and a homodimeric derivative of 3 (compound 54, pKi = 6.05, Table 1). The “8–1” type heterodimeric ligand 46 displayed the highest M2R affinity (pKi = 10.14, Table 1). Steep curve slopes (≤−1.79) were observed for 43, 51, 60, 61, 64, 67, and 70, indicating a complex mechanism of binding (e.g., the involvement of more than one binding site).

Table 3. M2R Binding Data (pKi or pIC50 Values) of Various Orthosteric (1 and 6), Allosteric (13–15), Dualsteric (7 and 10) MR Ligands, and 64 Determined with [3H]44, [3H]64, or [3H]5.

| ligand | [3H]44 pKia | [3H]64 pKia | [3H]5 pKi* or pIC50**b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.78 ± 0.05 | 6.55 ± 0.05* | |

| 6 | 8.52 ± 0.26 | 8.52 ± 0.14 | 9.04 ± 0.08* |

| 7 | 7.71 ± 0.14 | 8.71 ± 0.05* | |

| 10 | 9.61 ± 0.11 | 8.35 ± 0.09 | 9.11 ± 0.05* |

| 13 | 5.60 ± 0.07 | 6.11 ± 0.09**c | |

| 14 | 5.90 ± 0.22 | 6.08 ± 0.28 | 6.32 ± 0.18**c |

| 15 | 5.43 ± 0.02 | <4.5**c | |

| 64 | 9.44 ± 0.01 | 9.44 ± 0.06* |

Determined by equilibrium competition binding with [3H]44 (2 nM) or [3H]64 (0.3 nM) at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates; mean values ± SEM from at least three independent experiments (performed in triplicate).

Determined by equilibrium competition binding with [3H]5 (0.2 nM) at live CHO-hM2R cells; mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments (performed in triplicate).

Reported by Pegoli et al.23

2.2.2. MR Receptor Subtype Selectivity

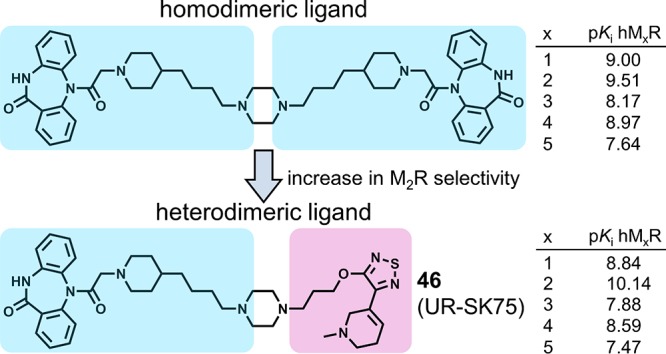

Selected dibenzodiazepinone-type heterodimeric ligands (34, 38, 39, 44, 46, 48, 50, 52, 61, 64, 67, 70, and 72) and monomeric dibenzodiazepinone derivative 35, containing an amino-functionalized homopiperazine moiety, were also investigated by equilibrium competition binding at the MR subtypes M1, M3, M4, and M5 with [3H]5 as the radioligand (Table 1). For all compounds, there was a preference for the M2R. Except for 38, the M1R and M4R affinities were higher than the M3R and M5R affinities, that is, the selectivity profile was M2 > M1 ≈ M4 > M3/M5 (34, 39, 44, 46, 48, 50, 52, 61, 64, 67, 70, and 72) and M2 > M1 ≈ M5 > M3 > M4 in the case of 38 (Table 1). Compound 46, showing the highest M2R affinity among the studied MR ligands, exhibited a more pronounced M2R selectivity than the pyridobenzodiazepinone-type ligand 7 (cf. Figure 1A),45 the MR antagonist tripitramine56 containing three pyridobenzodiazepinone moieties, as well as the recently reported dibenzodiazepinone derivatives 10 and 19 (cf. Figure 1C).23 Displacement of [3H]5 by 46 as well as by heterodimeric ligands 44 and 64, which were prepared as tritiated ligands (see below), from MxRs (determined at CHO-hMxR cells, x = 1–5) is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Displacement of [3H]5 [c = 0.2 nM (M1, M2, M3), 0.1 nM (M4), or 0.3 nM (M5)] by heterodimeric ligands 44 (A), 46 (B), and 64 (C) from MxRs determined at intact CHO-hMxR cells (x = 1–5). Data represent mean values ± SEM from at least three independent experiments (performed in triplicate).

2.3. Effect on IP1 Accumulation

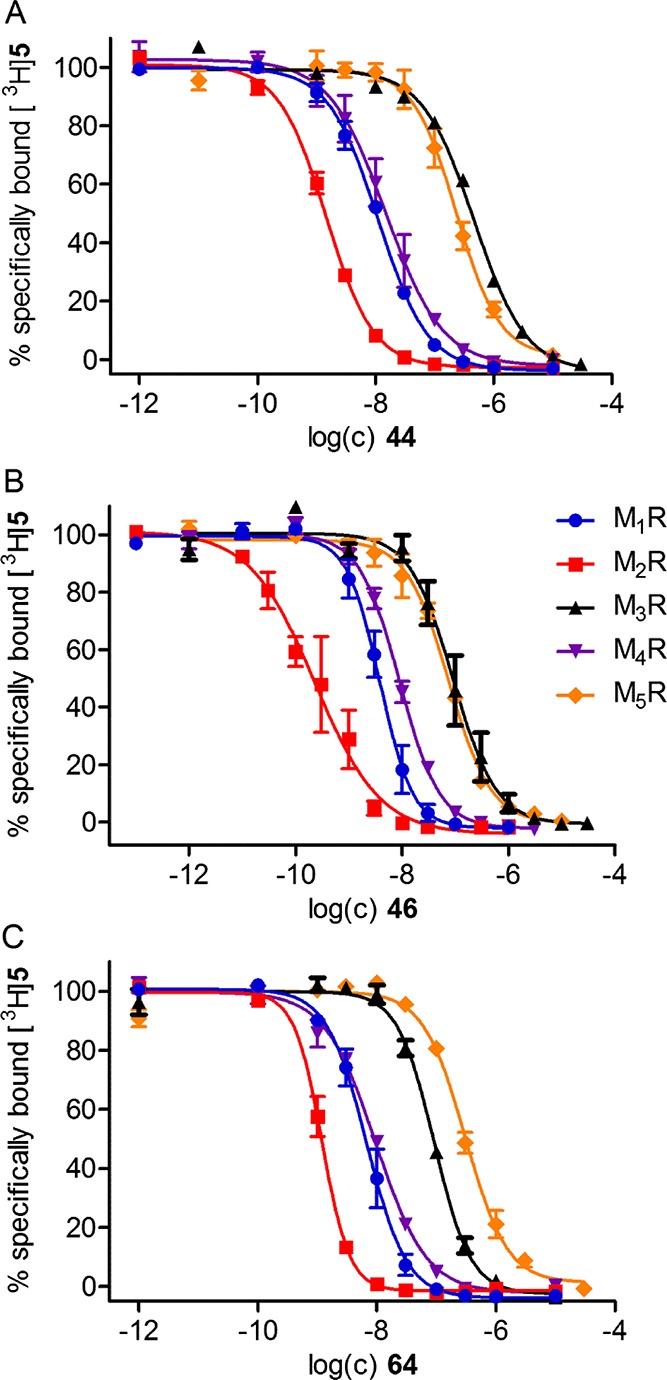

As previously reported for homodimeric dibenzodiazepinone derivative 19,23 the homodimeric xanomeline-type ligand 25 and the heterodimeric dibenzodiazepinone-type ligands 44, 46, and 64 were investigated with respect to M2R agonism and antagonism in an IP accumulation assay (Figure 3). Like 19, compounds 44, 46, and 64 did not induce an IP1 accumulation when investigated in the agonist mode (Figure 3A), but completely suppressed the effect of CCh when studied in the antagonist mode (Figure 3B), revealing that the combination of the agonist xanomeline (1) with a dibenzodiazepinone-type antagonist in one molecule (e.g., 44) resulted in a loss of agonistic activity. Interestingly, homodimeric ligand 25, which is derived from MR agonist 1, proved to be a M2R antagonist in contrast to parent compound 1 (Figure 3). The pKb values of 44, 46, and 64 (cf. Figure 3B) were lower compared to the respective pKi values (cf. Table 1), as previously observed for homodimeric ligand 19.23 Possible reasons for this discrepancy are discussed elsewhere.23

Figure 3.

M2R agonism and antagonism of 25, 44, 46, and 64 investigated in an IP1 accumulation assay using HEK-hM2-Gαqi5-HA cells. (A) Concentration-dependent effect of CCh, 1, 25, 44, 46, and 64 on the accumulation of IP1. 25, 44, 46, and 64 elicited no response. pEC50 of CCh and 1:6.96 and 7.45, respectively. Data represent mean values ± SEM from at least seven (CCh and 1) or at least two (25, 44, 46, and 64) independent experiments (each performed in triplicate). (B) Concentration-dependent inhibition of the IP1 accumulation induced by CCh (0.3 μM) by 6, 25, 44, 46, and 64. Corresponding pKb values: 6: 8.63,2325: 7.21, 44: 7.18, 46: 7.67, and 64: 7.93. Data represent mean values ± SEM from at least five independent experiments (each performed in duplicate).

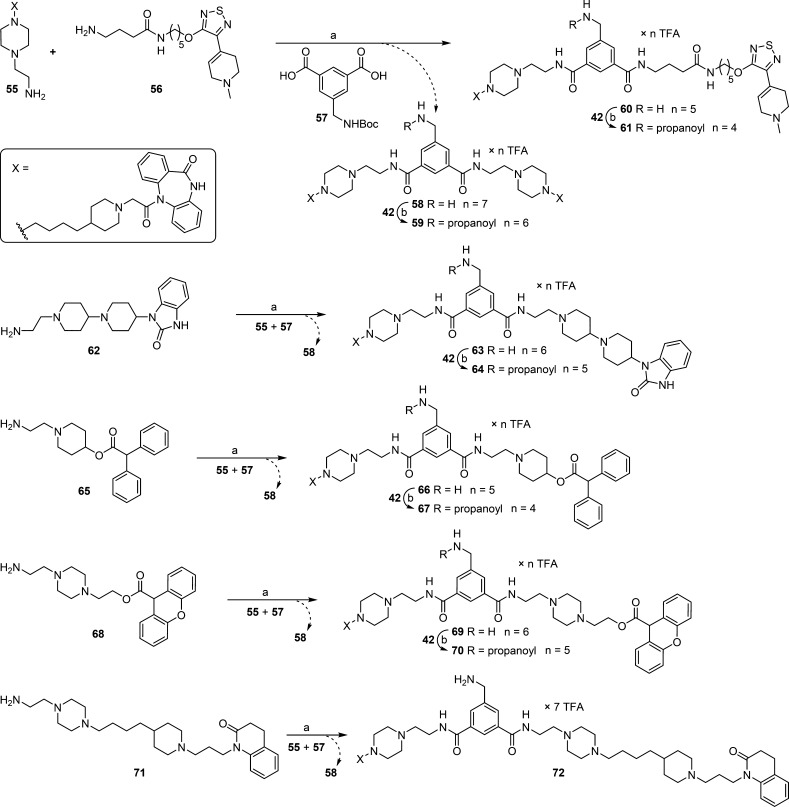

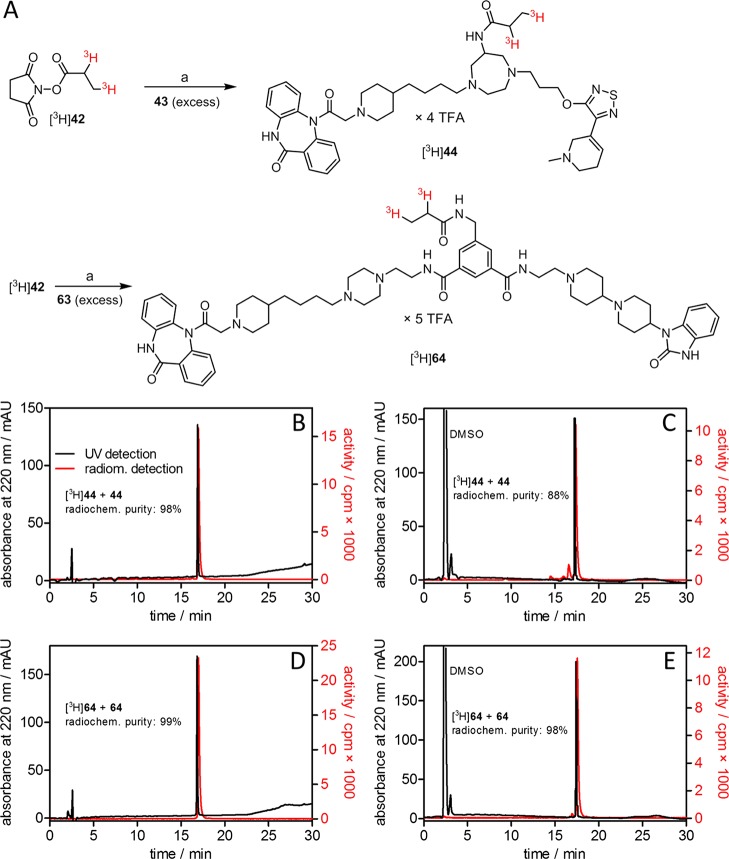

2.4. Synthesis of the Radiolabeled Ligands [3H]44 and [3H]64

Aiming at a radiolabeled derivative of heterodimeric ligand 46, which exhibited the highest M2R affinity and selectivity (cf. Table 1), compound 44, containing a propionamido-substituted homopiperazine moiety instead of the piperazine ring in 46 (cf. Scheme 2), was prepared as a tritiated derivative from amine precursor 43 and commercially available [3H]42 (Figure 4A). Additionally, the tritiated derivative of heterodimeric ligand 64 was prepared from 63 and [3H]42 (Figure 4A). The chemical stabilities of the “cold” analogues 44 and 64 were investigated under assaylike conditions [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4] for over 48 h. 44 and 64 proved to be stable under these conditions (cf. SI Figure 1, Supporting Information). [3H]44 and [3H]64 were obtained in high radiochemical purities (98% and 99%, respectively; Figure 4B,D) and showed a high ([3H]44) and excellent ([3H]64) stability when stored in ethanol at −20 °C (cf. Figure 4C,E).

Figure 4.

Preparation, purity, and identity control of the radiolabeled dibenzodiazepinone derivatives [3H]44 and [3H]64. (A) Synthesis of [3H]44 and [3H]64 by [3H]propionylation of amine precursors 43 and 63, respectively, using succinimidyl [3H]propionate ([3H]42). Reagents and conditions: (a) DIPEA, DMF, rt, 1.5 h, radiochemical yields: 36% ([3H]44) and 35% ([3H]64). (B,C) HPLC analysis of [3H]44 (0.18 μM) spiked with “cold” 44 (3 μM), analyzed 3 days after synthesis (B) and after 10 months of storage at −20 °C in EtOH/H2O (1:1) (C). (D,E) HPLC analysis of [3H]64 (0.23 μM) spiked with “cold” 64 (3 μM), analyzed 3 days after synthesis (D) and after 10 months of storage at −20 °C in EtOH/H2O (1:1) (E). HPLC conditions are provided in the Supporting Information.

2.5. Characterization of [3H]44 and [3H]64

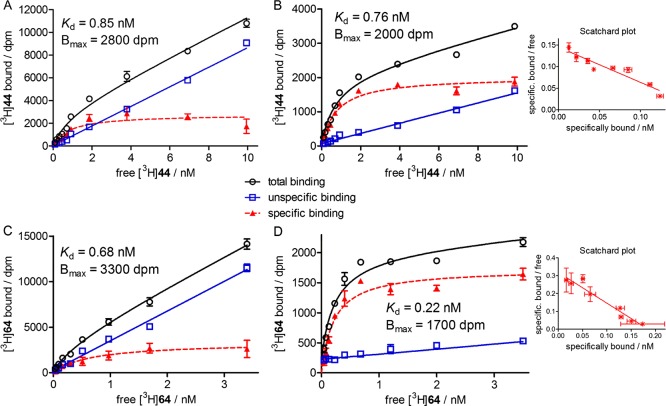

Saturation-binding experiments with [3H]44 and [3H]64 at intact CHO-hM2R cells or CHO-hM2R cell homogenates yielded monophasic saturation isotherms (Figure 5). As previously reported for [3H]19,23 the extent of unspecific binding strongly depended on the assay conditions: in the case of experiments performed at intact adherent cells (white/transparent 96-well plates), unspecific binding was considerably higher compared to experiments performed at cell homogenates, which preclude the unspecific binding of the radioligand to the microplate (Figure 5).23 The apparent Kd values amounted to 1.0 and 0.081 nM (cell homogenates, Table 2). As orthosteric antagonist 6 (used to determine unspecific binding) completely prevented hyperbolic (monophasic) binding of the radioligands to the M2R, these experiments proved that [3H]44 and [3H]64 bind to the orthosteric binding site of the M2R, as previously reported for [3H]19.23

Figure 5.

Representative hyperbolic (monophasic) isotherms of specific M2R binding (red dashed line) of [3H]44 (A,B) and [3H]64 (C,D) obtained from saturation-binding experiments either performed with live adherent CHO-hM2R cells (A,C) or CHO-hM2R cell homogenates (B,D). Unspecific binding (blue solid line) was determined in the presence of MR antagonist 6 (500-fold excess). Experiments were performed in triplicate. The error bars of specific binding and error bars in the Scatchard plots represent propagated errors calculated according to the Gaussian law of errors. The error bars of total and unspecific binding represent the SEM.

Table 2. M2R Binding Characteristics of [3H]44 and [3H]64.

| saturation-binding | binding kinetics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| radioligand | Kd [nM]a | Kd(kin) [nM]b | kon [min–1 nM–1]c | koff [min–1]d, t1/2 [min]d |

| [3H]44 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.078 ± 0.015 | 0.015 ± 0.001, 47 ± 3 |

| [3H]64 | 0.081 ± 0.022 | 0.072 ± 0.002 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.022 ± 0.002, 35 ± 1 |

Dissociation constant determined by saturation binding at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates; mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments (performed in triplicate).

Kinetically derived dissociation constant ± propagated error [Kd(kin) = koff/kon].

Association rate constant ± propagated error, calculated from kobs (nonlinear regression), koff (nonlinear regression), and the applied radioligand concentration (cf. Radioligand Binding).

Dissociation rate constant (nonlinear regression, two ([3H]44)- or three ([3H]64)-parameter equation describing a monophasic decline) and half-life; mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (performed in triplicate).

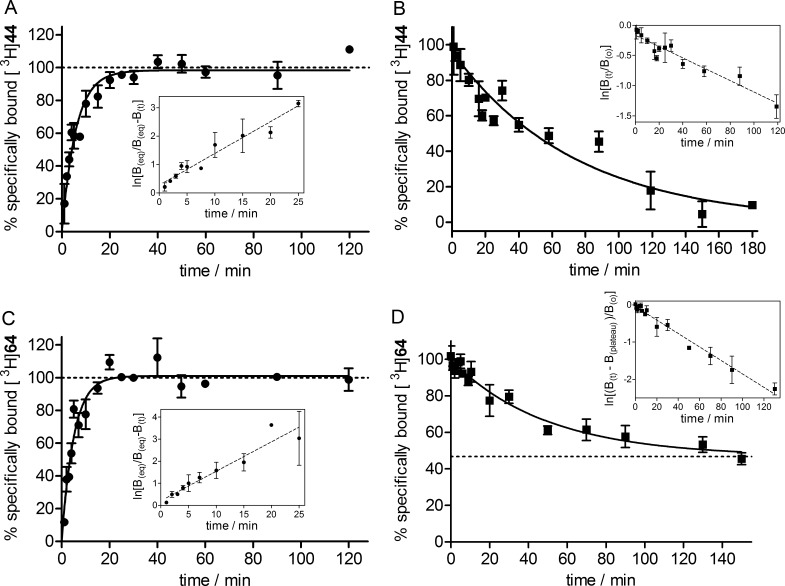

The association of [3H]44 and [3H]64 with the human M2R was monophasic and yielded similar kon values (Figure 6A,C, Table 2). Whereas the “8–1” type heterodimeric ligand [3H]44 dissociated completely from the M2R (t1/2 = 47 min, cf. Figure 6B, Table 2), the dissociation of the “8–11” type dimeric ligand [3H]64 was incomplete, reaching a plateau at approximately 47% of initially M2R-bound [3H]64 (t1/2 = 35 min, cf. Figure 6D, Table 2). An incomplete ligand dissociation, which might be attributed to conformational adjustments of the receptor upon ligand binding57 or an enhanced rebinding capability of the dimeric ligand,58 was also reported for the homodimeric dibenzodiazepinone-type ligand [3H]19.23 The kinetically derived dissociation constants of both [3H]44 and [3H]64 [Kd(kin): 0.33 and 0.057 nM, respectively] were in good accordance with the Kd values obtained from the saturation-binding experiments (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Association and dissociation kinetics of [3H]44 (A,B) and [3H]64 (C,D) determined at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates at 23 °C. (A) Association of [3H]44 (c = 2 nM) with the M2R. Inset: ln[B(eq)/(B(eq) – B(t))] vs time. (B) Dissociation of [3H]44 (preincubation: 4 nM, 1 h) from the M2R determined in the presence of 6 (1000-fold excess), showing complete monophasic exponential decline. Inset: ln[B(t)/B(0)] vs time. (C) Association of [3H]64 (c = 0.6 nM) with the M2R. Inset: ln[B(eq)/(B(eq) – B(t))] vs time. (D) Dissociation of [3H]64 (preincubation: 0.6 nM, 1 h) from the M2R determined in the presence of 6 (1000-fold excess), showing incomplete monophasic exponential decline. Inset: ln[(B(t) – B(plateau)/B(0)] versus time. For kon and koff values, see Table 2. Data represent mean ± SEM from three (A,B,D) or two (C) independent experiments (each performed in triplicate).

2.6. Competition Binding at the M2R Using [3H]44 and [3H]64 as Radioligands

Heterodimeric radioligands [3H]44 and [3H]64 were applied to equilibrium competition-binding experiments at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates involving various reported orthosteric, dualsteric, and allosteric MR ligands. Orthosteric MR antagonist 6, dualsteric ligand 10, and allosteric modulator 14 (cf. Figure 1) were capable of totally displacing [3H]44 from the M2R (SI Figure 2A, Supporting Information), indicating either a competitive mechanism or a strongly negative cooperativity between dimeric ligand [3H]44 and 6, 10, or 14. Likewise, orthosteric ligands 1 and 6, dualsteric ligands 7 and 10, as well as allosteric modulators 13–15 (cf. Figure 1) completely displaced [3H]64 from the M2R-specific binding sites. (SI Figure 2B, Supporting Information). For most of the investigated MR ligands, the respective pKi values were in good agreement with the binding data obtained from competition binding with [3H]5 (Table 3). However, the pKi values of compounds 1, 6, 7, and 10, determined in the presence of [3H]64, were consistently lower (up to 1 log unit in the case of 7) than pKi values from the competition-binding experiments with [3H]5. This is in agreement with the (in part) irreversible M2R binding of [3H]64 (cf. Figure 6D), which compromises its use as a molecular tool for the determination of binding constants of nonlabeled ligands, as was also reported for homodimeric MR ligand [3H]19.23

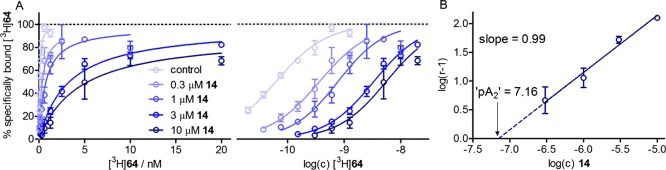

2.7. Schild-like Analysis with [3H]64 and Allosteric M2R Modulator 14

To further explore the binding mode of heterodimeric ligand 64 at the M2R, saturation-binding experiments were performed with [3H]64 in the presence of increasing concentrations of allosteric M2R ligand 14 (Figure 7), as recently reported for homodimeric radioligand [3H]19.23 As in the case of [3H]19,23 this Schild-like analysis resulted in rightward-shifted saturation isotherms of [3H]64 (Figure 7A) and a linear Schild plot with a slope not different from unity (Figure 7B), which is consistent with a competitive mechanism between [3H]64 and allosteric M2R ligand 14. With regard to the fact that [3H]64 binds to the orthosteric binding site of the M2R (see above), these results strongly support a dualsteric binding mode of 64 at the human M2R. The “pA2” value of 7.16, obtained for 14 from the Schild regression (Figure 7B), was in accordance with the reported M2R binding data of 14 (pKX 7.5059).

Figure 7.

Effect of allosteric M2R modulator 14 on the saturation binding of [3H]64 determined at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates at 22 °C. (A) Isotherms of specific radioligand binding plotted in the linear and semilogarithmic scale. The presence of compound 14 led to a rightward shift of the saturation isotherms of [3H]64. (B) “Schild” regression resulting from the rightward shifts (ΔpKd) of the saturation isotherms [log(r – 1) plotted vs log(concentration 14), where r = 10ΔpKd]. The slope of the linear Schild regression was not different from unity [P > 0.5, based on the slope mean value ± SEM (0.99 ± 0.15) from three sets of independent saturation-binding experiments (performed in triplicate)], suggesting a competitive interaction between [3H]64 and 14. Data represent mean values ± SEM from three independent experiments (each performed in triplicate).

3. Conclusions

Linking orthosteric (1, 3, and 4) and allosteric (11 and 12) MR ligands with a M2R preferring dibenzodiazepinone-type MR antagonist (8) yielded a series of heterodimeric ligands (34, 38, 39, 43, 44, 46, 48, 50–52, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, and 72). The “8–1” type dimeric ligand 46 (UR-SK75), containing a piperazine moiety in the linker, exhibited a higher M2R affinity (pKi 10.14) and selectivity [expressed as the ratio of Ki values (M1/M2/M3/M4/M5): 23:1:180:29:430] compared to monomeric (such as 8(46) and 10(22,23)) and homodimeric (e.g., 18(22) and 19(23)) dibenzodiazepinone-type ligands. High M2R affinity of all dibenzodiazepinone-type heterodimeric ligands (pKi > 8.3, Table 1), as also reported for monomeric dibenzodiazepinone-type ligands,22 suggested a minor influence of the second pharmacophore on M2R binding, indicating that the high M2R affinity of these compounds is mediated by the “dibenzodiazepinone” pharmacophore, which binds most likely to the orthosteric binding site of the M2R. This is supported by the proposed binding mode of 10 and 19 at the M2R,23 by saturation-binding studies using the radioligands [3H]44 ([3H]UR-SK71) and [3H]64 ([3H]UR-SK59), and by the fact that compounds containing M1R/M4R selective agonist 1(49) as a second pharmacophore (43, 44, 46, 60, and 61) proved to be M2R-preferring ligands. Moreover, the prototypical heterodimeric ligands 44 and 46 were shown to be M2R antagonists (cf. Figure 3). Concerning the “8–1” type heterodimeric ligands, one can speculate about the contribution of the pharmacophore of 1 to M2R binding because the homodimeric derivatives of 1 (compounds 25, 27–29) exhibited considerably higher M2R affinities compared to 1. This work confirms that dibenzodiazepinone-type MR ligands represent a promising class of compounds for the development of highly selective M2R ligands with a high receptor affinity based on the dualsteric ligand approach.

4. Methods

4.1. General Experimental Conditions

Reagents and chemicals for synthesis were purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), Iris Biotech (Marktredwitz, Germany), Alfa Aesar (Karlsruhe, Germany), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Sigma (Munich, Germany), or TCI Europe (Zwijndrecht, Belgium). Technical grade solvents (acetone, ethyl acetate, light petroleum (40–60 °C), and CH2Cl2) were distilled before use. Deuterated solvents for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy were from Deutero (Kastellaun, Germany). Acetonitrile for HPLC (gradient grade) was obtained from Merck or Sigma. Anhydrous DMF was purchased from Sigma. CCh (Sigma) and compounds 6 (Sigma), 7 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), 13 (Sigma), 14 (Sigma), and 15 (Absource Diagnostic, Munich, Germany) were purchased from commercial suppliers. The radiolabeled MR antagonist [3H]5 (specific activity = 80 Ci/mmol) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc. (St. Louis, MO) via Hartmann Analytic (Braunschweig, Germany). The syntheses of compounds 40,2342,60 and 57(23) are described elsewhere. Compounds 1,61120,23 and 123(62) were prepared according to described procedures.

Millipore water was used throughout for the preparation of buffers and HPLC eluents. If moisture-free conditions were required, reactions were performed in dried glassware under an inert atmosphere (argon). Anhydrous THF was obtained by distillation over sodium, and anhydrous CH2Cl2 was prepared by distillation over P2O5 after predrying over CaCl2. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography using aluminum plates coated with silica gel (Merck silica gel 60 F254, thickness 0.2 mm). Spots were detected by ultraviolet (UV) light (254 or 366 nm) or by staining using 0.3% solution of ninhydrin in n-butanol (amines) or iodine. Column chromatography was performed in glass columns on silica gel (Merck silica gel 60, 63–200 μm). Flash chromatography was performed on an Intelli Flash-310 Flash-Chromatography Workstation (Varian, Darmstadt, Germany). Polypropylene reaction vessels (1.5 or 2 mL) with a screw cap (Süd-Laborbedarf, Gauting, Germany) were used for the synthesis of radioligands ([3H]44 and [3H]64) for small-scale reactions, for the investigation of chemical stabilities (44 and 64), and for the preparation and storage of stock solutions. Melting points were measured with a Büchi 530 (Büchi, Essen, Germany) apparatus and are uncorrected. Microwave-assisted reactions were performed with an Initiator 2.0 synthesizer (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 300 (7.05 T), Bruker AVANCE III HD 400 (9.40 T), or a Bruker AVANCE III HD 600 spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe (14.1 T) (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). Abbreviations for the multiplicities of the signals are s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), dd (doublet-of-doublet), q (quartet), m (multiplet), and brs (broad-singlet). Infrared (IR) spectra were measured with a Nicolet 380 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Thermo Electron Corporation). Low-resolution mass spectrometry was performed on a Finnigan SSQ 710A instrument [chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CI-MS, Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis was performed on an Agilent 6540 UHD Accurate-Mass Q-TOF LC/MS system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) using an electrospray ionization source. Preparative HPLC was performed on a system from Knauer (Berlin, Germany) consisting of two K-1800 pumps and a K-2001 detector. Except for compound 54, a Kinetex-XB C18 column, 5 μm, 250 × 21 mm (Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany) served as the stationary phase at a flow rate of 15 mL/min. For the purification of 54, a Nucleodur 100-5 C18 column, 5 μm, 250 × 21 mm (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) was used as the stationary phase at a flow rate of 15 mL/min. Mixtures of acetonitrile and 0.1% aq TFA were used as the mobile phase, and a detection wavelength of 220 nm was used throughout. Lyophilization of the collected fractions was performed with an Alpha 2-4 LD apparatus (Martin Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany). Except for compound 54, analytical HPLC analysis (purity control) was performed on a system from Merck-Hitachi (Hitachi, Düsseldorf, Germany) composed of a L-6200-A pump, an AS-2000A autosampler, a L-4000A UV detector, and a D-6000 interface. A Kinetex-XB C18 column, 5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm (Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany) was used as the stationary phase at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. Mixtures of acetonitrile (A) and 0.1% aq TFA (B) were used as the mobile phase (degassed by helium purging). The following linear gradient was applied: 0–30 min: A/B 5:95–85:15, 30–32 min: 85:15–95:5, and 32–40 min: 95:5. Detection was performed at 220 nm throughout. The oven temperature was 30 °C. Analytical HPLC analysis of 54 was performed on a system from Thermo Separation Products composed of a SN400 controller, a P4000 pump, a degasser (Degassex DG-4400, Phenomenex), an AS3000 autosampler, and a Spectra Focus ultraviolet–visible detector. A Eurospher-100 C18 column, 5 μm, 250 × 4 mm (Knauer, Berlin, Germany) served as reversed-phase (RP) column at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. Mixtures of acetonitrile (A) and 0.05% aq TFA (B) were used as the mobile phase (degassed by helium purging). The oven temperature was set to 30 °C, and detection was performed at 220 nm. The following linear gradient was applied: 0–30 min: A/B 20:80–95:5 and 30–40 min: 95:5.

Annotation concerning the NMR spectra (1H, 13C) of the dibenzodiazepinone derivatives (34, 35, 38, 39, 43, 44, 46, 48, 50, 52, 58–61, 63, 64, 66, 69, and 72): due to a slow rotation about the exocyclic amide group on the NMR time scale, two isomers (ratios provided in the experimental protocols) were evident in the 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra.

4.2. Compound Characterization

Nondescribed intermediate compounds were characterized by 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopy, HRMS, and melting point (if applicable). Target compounds were characterized by 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopy, HRMS, and RP-HPLC analysis. In addition, compounds 44 and 64 were analyzed by IR spectroscopy. Purities determined by analytical RP-HPLC amounted to >95%.

4.3. Investigation of the Chemical Stability

The chemical stability of 44 and 64 was investigated in PBS (pH 7.4) at 22 ± 1 °C. The incubation was started by addition of 10 mM solution of the compounds in dimethylsulfoxide (1 μL) to PBS (99 μL) to give a final concentration of 100 μM. After 0, 12, and 48 h, an aliquot (20 μL) of the solution was taken and added to acetonitrile/0.04% aq TFA (1:9 v/v) (20 μL). An aliquot (20 μL) of the resulting solution was analyzed by RP-HPLC using a system from Agilent Technologies (composed of a 1290 Infinity binary pump equipped with a degasser, a 1290 Infinity autosampler, a 1290 Infinity thermostated column compartment, a 1260 Infinity diode array detector, and a 1260 Infinity fluorescence detector). A Kinetex-XB C18 column, 2.6 μm, 100 × 3 mm (Phenomenex) served as the stationary phase at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The following linear gradient was applied: 0–20 min: acetonitrile/0.04% aq TFA 10:90–68:32, 20–22 min: 68:32–95:5, and 22–28 min: 95:5. The detection wavelength was set to 220 nm.

4.4. Cell Culture and Preparation of Cell Homogenates

The culture conditions of CHO-K9 cells, stably transfected with the human muscarinic receptors M1–M5 (obtained from Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center; Rolla, MO), and the preparation of CHO-hM2R cell homogenates are described elsewhere.23

4.5. IP1 Accumulation Assay

The IP1 accumulation assay was performed as described elsewhere.23

4.6. Radioligand Binding

Equilibrium competition-binding experiments with [3H]5 were performed at intact CHO-hMxR cells (x = 1–5) as described previously,22 but the total volume per well was 200 μL, that is, in the case of total binding, the wells were filled with 180 μL of L15 medium followed by addition of L15 medium (20 μL) containing [3H]5 (10-fold concentrated). To determine the unspecific binding and the effect of a compound of interest on the equilibrium binding [3H]5, the wells were filled with 160 μL of L15 medium followed by addition of L15 medium (20 μL) containing 6 or the compound of interest (10-fold concentrated) and L15 medium (20 μL) containing [3H]5 (10-fold concentrated).

Saturation binding with [3H]44 and [3H]64 at intact CHO-hM2R cells was performed in the same manner as saturation-binding experiments with [3H]522 with minor modifications: unspecific binding was determined in the presence of 6 (500-fold excess to [3H]44 or [3H]64), and the incubation period was 2 h.

Saturation and equilibrium competition-binding experiments with [3H]44 and [3H]64 at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates were performed according to the procedure described for saturation and competition-binding experiments with [3H]19 at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates,23 using a total volume per well of 200 instead of 100 μL. The total amount of soluble protein per well was between 19 and 43 μg. In the case of competition-binding experiments, the radioligand concentration was 2.0 and 0.3 nM, respectively. To keep the total volume per well at 200 μL in the case of saturation-binding experiments performed with [3H]64 in the presence of 14, the addition of L15 medium (20 μL) containing 14 (10-fold concentrated) was compensated by an equivalent reduction in the volume of L15 medium added to the wells.

M2R association experiments with [3H]44 and [3H]64 were performed at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates essentially using the procedure described for saturation-binding experiments with [3H]19 at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates.23 The radioligand concentration was 2 and 0.6 nM, respectively. The incubation was started in reversed order after different periods of time (120–1 min). After last addition of the radioligand, homogenates were collected on filter mats using the Harvester. Unspecific binding was determined in the presence of 6 (500-fold excess to the radioligand). For M2R dissociation experiments with [3H]44 and [3H]64, performed at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates, the procedure was essentially the same as for saturation-binding experiments with [3H]19 at CHO-hM2R cell homogenates.23 The preincubation (60 min) of the cell homogenates with the radioligand ([3H]44: 4 nM, [3H]64: 0.6 nM) was started in reversed order after different periods of time ([3H]44: between 180 and 1 min and [3H]64: between 150 and 1 min) by addition of L15 medium (10 μL) containing the radioligand (10-fold concentrated) to the wells preloaded with L15 medium (80 μL) and cell homogenates (10 μL). The dissociation was started by addition of 10 μL of L15 medium containing 6 (40 and 6 μM, respectively) and was stopped by collection and washing of the homogenates using the harvester. To determine unspecific binding, 6 (1000-fold excess to the radioligand) was added during the preincubation step.

4.7. Data Processing

Retention (capacity) factors were calculated from retention times (tR) according to k = (tR – t0)/t0 (t0 = dead time). Data from the IP1 accumulation assay and radioligand-binding assays [saturation binding (including Schild-like analysis), association and dissociation kinetics, and equilibrium competition binding] were processed as described previously.23 Statistical significance (curve slopes) was assessed by a t-test (one-sample, two-tailed). Propagated errors were calculated according to the Gaussian law of errors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brigitte Wenzl, Maria Beer-Krön, Dita Fritsch, and Susanne Bollwein for excellent technical assistance. The authors also thank Armin Buschauer for providing laboratory equipment and for helpful suggestions. This work was funded by the Graduate Training Program (Graduiertenkolleg) GRK1910 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and by the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- Boc

tert-butoxycarbonyl

- Bmax

maximum number of binding sites

- brs

broad singlet

- CH2Cl2

dichloromethane

- MeCN

acetonitrile

- CHO-cells

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- DCC

N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- DIPEA

diisopropylethylamine

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- dpm

disintegrations per minute

- EtOAc

ethylacetate

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate

- IP1

inositol monophosphate

- k

retention (or capacity) factor (HPLC)

- Kd

dissociation constant obtained from a saturation binding experiment

- Ki

dissociation constant obtained from a competition binding experiment

- kobs

observed rate constant

- koff

dissociation rate constant

- kon

association rate constant

- MR

muscarinic receptor

- MxR

muscarinic Mx (x = 1–5) receptor

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- pKb

negative logarithm of the Kb (dissociation constant obtained from a functional assay (inhibition of the effect elicited by an agonist)) in M

- pKi

negative logarithm of the Ki in M

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TBTU

2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- tR

retention time

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01085.

Description of the synthesis of intermediates 20, 21, 23, 26, 30, 32, 33, 36, 37, 40, 42, 45, 47, 49, 53, 55–57, 62, 65, 68, and 71; experimental protocols for the synthesis and analytical data of compounds 20–23, 25, 26–39, 43–57, 58–72, 75–77, 79–81, 83, 84, 86, 87, 89, 90, 92, 93, 95–97, 100–104, 108–110, 114–116, 119, 121, 122, and 124; experimental protocol for the synthesis of the radioligands [3H]44 and [3H]64; 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra of compounds 22, 25, 27–29, 31, 34, 35, 38, 39, 43, 44, 46, 48, 50–52, 55, 58–61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, and 72; RP-HPLC chromatograms of compounds 22, 25, 27–29, 31, 34, 35, 38, 39, 43, 44, 46, 48, 50–52, 55, 58–61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, and 72 (PDF)

Author Present Address

§ HitGen, F7-10, Building B3, Tianfu Life Science Park 88 South Keyuan Road, Chengdu, 610041, China (X.S.).

Author Present Address

∥ Institute of Organic Chemistry, Faculty of Chemistry and Pharmacy, University of Regensburg, Universitätsstr. 31, D-93053 Regensburg, Germany (J.M.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hammer R.; Berrie C. P.; Birdsall N. J. M.; Burgen A. S. V.; Hulme E. C. Pirenzepine distinguishes between different subclasses of muscarinic receptors. Nature 1980, 283, 90–92. 10.1038/283090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner T.; Buckley N.; Young A.; Brann M. Identification of a family of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor genes. Science 1987, 237, 527–532. 10.1126/science.3037705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield M. P. Muscarinic receptors—characterization, coupling and function. Pharmacol. Ther. 1993, 58, 319–379. 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90027-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield M. P.; Birdsall N. J. International Union of Pharmacology. XVII. Classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998, 50, 279–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzafame A. A.; Christopoulos A.; Mitchelson F. Cellular Signaling Mechanisms for Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Recept. Channels 2003, 9, 241–260. 10.3109/10606820308263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B.; Bymaster F.; Scarr E. Muscarinic receptors in schizophrenia. Curr. Mol. Med. 2003, 3, 419–426. 10.2174/1566524033479654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clader J.; Wang Y. Muscarinic receptor agonists and antagonists in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005, 11, 3353–3361. 10.2174/138161205774370762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K.; Kruse A. C.; Asada H.; Yurugi-Kobayashi T.; Shiroishi M.; Zhang C.; Weis W. I.; Okada T.; Kobilka B. K.; Haga T.; Kobayashi T. Structure of the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor bound to an antagonist. Nature 2012, 482, 547–551. 10.1038/nature10753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse A. C.; Hu J.; Pan A. C.; Arlow D. H.; Rosenbaum D. M.; Rosemond E.; Green H. F.; Liu T.; Chae P. S.; Dror R. O.; Shaw D. E.; Weis W. I.; Wess J.; Kobilka B. K. Structure and dynamics of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature 2012, 482, 552–556. 10.1038/nature10867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal D. M.; Sun B.; Feng D.; Nawaratne V.; Leach K.; Felder C. C.; Bures M. G.; Evans D. A.; Weis W. I.; Bachhawat P.; Kobilka T. S.; Sexton P. M.; Kobilka B. K.; Christopoulos A. Crystal structures of the M1 and M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Nature 2016, 531, 335–340. 10.1038/nature17188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglen R. M.; Choppin A.; Watson N. Therapeutic opportunities from muscarinic receptor research. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001, 22, 409–414. 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01737-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr K.; Tränkle C.; Holzgrabe U. Structure/activity relationships of M2 muscarinic allosteric modulators. Recept. Channels 2003, 9, 229–240. 10.1080/10606820308264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigtländer U.; Jöhren K.; Mohr M.; Raasch A.; Tränkle C.; Buller S.; Ellis J.; Höltje H.-D.; Mohr K. Allosteric site on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: identification of two amino acids in the muscarinic M2 receptor that account entirely for the M2/M5 subtype selectivities of some structurally diverse allosteric ligands in N-methylscopolamine-occupied receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 64, 21–31. 10.1124/mol.64.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J. Allosteric binding sites on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 68, 1506–1509. 10.1124/mol.105.019141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presland J. Identifying novel modulators of G protein-coupled receptors via interaction at allosteric sites. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 2005, 8, 567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn P. J.; Christopoulos A.; Lindsley C. W. Allosteric modulators of GPCRs: a novel approach for the treatment of CNS disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 41–54. 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse A. C.; Ring A. M.; Manglik A.; Hu J.; Hu K.; Eitel K.; Hübner H.; Pardon E.; Valant C.; Sexton P. M. Activation and allosteric modulation of a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature 2013, 504, 101–106. 10.1038/nature12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüllmann H.; Ohnesorge F. K.; Schauwecker G.-C.; Wassermann O. Inhibition of the actions of carbachol and DFP on guinea pig isolated atria by alkane-bis-ammonium compounds. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1969, 6, 241–247. 10.1016/0014-2999(69)90181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr K.; Tränkle C.; Kostenis E.; Barocelli E.; De Amici M.; Holzgrabe U. Rational design of dualsteric GPCR ligands: quests and promise. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 159, 997–1008. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. L.; Mitchelson F. The inhibitory effect of gallamine on muscarinic receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1976, 58, 323–331. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1976.tb07708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tränkle C.; Andresen I.; Lambrecht G.; Mohr K. M2 receptor binding of the selective antagonist AF-DX 384: possible involvement of the common allosteric site. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998, 53, 304–312. 10.1124/mol.53.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Tränkle C.; She X.; Pegoli A.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A.; Read R. W. M2 Subtype preferring dibenzodiazepinone-type muscarinic receptor ligands: Effect of chemical homo-dimerization on orthosteric (and allosteric?) binding. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 3970–3990. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegoli A.; She X.; Wifling D.; Hübner H.; Bernhardt G.; Gmeiner P.; Keller M. Radiolabeled Dibenzodiazepinone-Type Antagonists Give Evidence of Dualsteric Binding at the M2 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3314–3334. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy C. H.; Schober D. A.; Xiao H.; Quets A.; Christopoulos A.; Felder C. C. Characterization of the novel positive allosteric modulator, LY2119620, at the muscarinic M2 and M4 receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014, 86, 106–115. 10.1124/mol.114.091751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober D. A.; Croy C. H.; Xiao H.; Christopoulos A.; Felder C. C. Development of a Radioligand, [3H]LY2119620, to Probe the Human M2 and M4 Muscarinic Receptor Allosteric Binding Sites. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014, 86, 116–123. 10.1124/mol.114.091785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonberg J.; Scammells P. J.; Capuano B. Design strategies for bivalent ligands targeting GPCRs. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 963–974. 10.1002/cmdc.201100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berque-Bestel I.; Lezoualc’h F.; Jockers R. Bivalent ligands as specific pharmacological tools for G protein-coupled receptor dimers. Curr. Drug Discovery Technol. 2008, 5, 312–318. 10.2174/157016308786733591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan R. G.; Sharma S. K.; Xie Z.; Daniels D. J.; Portoghese P. S. A bivalent ligand (KDN-21) reveals spinal δ and κ opioid receptors are organized as heterodimers that give rise to δ1 and κ2 phenotypes. Selective targeting of δ−κ heterodimers. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 2969–2972. 10.1021/jm0342358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnkammer T.; Spickenreither A.; Brunskole I.; Lopuch M.; Kagermeier N.; Bernhardt G.; Dove S.; Seifert R.; Elz S.; Buschauer A. The bivalent ligand approach leads to highly potent and selective acylguanidine-type histamine H2 receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1147–1160. 10.1021/jm201128q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagermeier N.; Werner K.; Keller M.; Baumeister P.; Bernhardt G.; Seifert R.; Buschauer A. Dimeric carbamoylguanidine-type histamine H2 receptor ligands: A new class of potent and selective agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 3957–3969. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D.; Hübner H.; Gmeiner P. 1,1′-Disubstituted ferrocenes as molecular hinges in mono- and bivalent dopamine receptor ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6860–6870. 10.1021/jm901120h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühhorn J.; Hübner H.; Gmeiner P. Bivalent dopamine D2 receptor ligands: synthesis and binding properties. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 4896–4903. 10.1021/jm2004859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano A.; Ventura R.; Molero A.; Hoen R.; Casadó V.; Cortés A.; Fanelli F.; Albericio F.; Lluís C.; Franco R.; Royo M. Adenosine A2A receptor-antagonist/dopamine D2 receptor-agonist bivalent ligands as pharmacological tools to detect A2A-D2 receptor heteromers. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 5590–5602. 10.1021/jm900298c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson K. A.; Xie R.; Young L.; Chang L.; Liang B. T. A novel pharmacological approach to treating cardiac ischemia binary conjugates of A1 and A3 adenosine receptor agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 30272–30279. 10.1074/jbc.m001520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausler N. E.; Devine S. M.; McRobb F. M.; Warfe L.; Pouton C. W.; Haynes J. M.; Bottle S. E.; White P. J.; Scammells P. J. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of dual acting antioxidant A2A adenosine receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3521–3534. 10.1021/jm300206u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S.; Keller M.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A.; König B. Modular synthesis of non-peptidic bivalent NPY Y1 receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 9858–9866. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Teng S.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Bivalent Argininamide-Type Neuropeptide Y Y1 Antagonists Do Not Support the Hypothesis of Receptor Dimerisation. ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 1733–1745. 10.1002/cmdc.200900213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Kaske M.; Holzammer T.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Dimeric argininamide-type neuropeptide Y receptor antagonists: chiral discrimination between Y1 and Y4 receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 6303–6322. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie B. J.; Christopoulos A.; Scammells P. J. Development of M1 mAChR allosteric and bitopic ligands: prospective therapeutics for the treatment of cognitive deficits. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 1026–1048. 10.1021/cn400086m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valant C.; Lane J. R.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A. The best of both worlds? Bitopic orthosteric/allosteric ligands of g protein–coupled receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012, 52, 153–178. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony J.; Kellershohn K.; Mohr-Andra M.; Kebig A.; Prilla S.; Muth M.; Heller E.; Disingrini T.; Dallanoce C.; Bertoni S.; Schrobang J.; Tränkle C.; Kostenis E.; Christopoulos A.; Holtje H.-D.; Barocelli E.; De Amici M.; Holzgrabe U.; Mohr K. Dualsteric GPCR targeting: a novel route to binding and signaling pathway selectivity. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 442–450. 10.1096/fj.08-114751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane J. R.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A. Bridging the gap: bitopic ligands of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 59–66. 10.1016/j.tips.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disingrini T.; Muth M.; Dallanoce C.; Barocelli E.; Bertoni S.; Kellershohn K.; Mohr K.; De Amici M.; Holzgrabe U. Design, synthesis, and action of oxotremorine-related hybrid-type allosteric modulators of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 366–372. 10.1021/jm050769s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld T.; Mammen M.; Smith J. A. M.; Wilson R. D.; Jasper J. R. A novel multivalent ligand that bridges the allosteric and orthosteric binding sites of the M2 muscarinic receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007, 72, 291–302. 10.1124/mol.106.033746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörje F.; Wess J.; Lambrecht G.; Tacke R.; Mutschler E.; Brann M. R. Antagonist binding profiles of five cloned human muscarinic receptor subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991, 256, 727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler M. S.; Reba R. C.; Cohen V. I.; Rzeszotarski W. J.; Baumgold J. A novel m2-selective muscarinic antagonist: binding characteristics and autoradiographic distribution in rat brain. Brain Res. 1992, 582, 253–260. 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90141-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr M.; Heller E.; Ataie A.; Mohr K.; Holzgrabe U. Development of a new type of allosteric modulator of muscarinic receptors: hybrids of the antagonist AF-DX 384 and the hexamethonio derivative W84. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 3324–3327. 10.1021/jm031095t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzgrabe U.; De Amici M.; Mohr K. Allosteric modulators and selective agonists of muscarinic receptors. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2006, 30, 165–167. 10.1385/jmn:30:1:165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar A.; Potter W. Z.; Lightfoot J.; Lienemann J.; Dubé S.; Mallinckrodt C.; Bymaster F. P.; McKinzie D. L.; Felder C. C. Selective muscarinic receptor agonist xanomeline as a novel treatment approach for schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 1033–1039. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.06091591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges T. M.; Brady A. E.; Kennedy J. P.; Daniels R. N.; Miller N. R.; Kim K.; Breininger M. L.; Gentry P. R.; Brogan J. T.; Jones C. K.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. Synthesis and SAR of analogues of the M1 allosteric agonist TBPB. Part I: Exploration of alternative benzyl and privileged structure moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 5439–5442. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N. R.; Daniels R. N.; Bridges T. M.; Brady A. E.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W. Synthesis and SAR of analogs of the M1 allosteric agonist TBPB. Part II: Amides, sulfonamides and ureas—The effect of capping the distal basic piperidine nitrogen. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 5443–5447. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. K.; Brady A. E.; Davis A. A.; Xiang Z.; Bubser M.; Tantawy M. N.; Kane A. S.; Bridges T. M.; Kennedy J. P.; Bradley S. R. Novel selective allosteric activator of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor regulates amyloid processing and produces antipsychotic-like activity in rats. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 10422–10433. 10.1523/jneurosci.1850-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keov P.; Valant C.; Devine S. M.; Lane J. R.; Scammells P. J.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A. Reverse engineering of the selective agonist TBPB unveils both orthosteric and allosteric modes of action at the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 84, 425–437. 10.1124/mol.113.087320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avlani V. A.; Langmead C. J.; Guida E.; Wood M. D.; Tehan B. G.; Herdon H. J.; Watson J. M.; Sexton P. M.; Christopoulos A. Orthosteric and allosteric modes of interaction of novel selective agonists of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 78, 94–104. 10.1124/mol.110.064345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F.; Buchwald P.; Browne C. E.; Farag H. H.; Wu W.-M.; Ji F.; Hochhaus G.; Bodor N. Receptor binding studies of soft anticholinergic agents. AAPS PharmSci 2001, 3, 44–56. 10.1208/ps030430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio R.; Barbier P.; Bolognesi M. L.; Minarini A.; Tedeschi D.; Melchiorre C. Binding profile of the selective muscarinic receptor antagonist tripitramine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 268, 459–462. 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland R. A. Conformational adaptation in drug–target interactions and residence time. Future Med. Chem. 2011, 3, 1491–1501. 10.4155/fmc.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauquelin G. Simplified models for heterobivalent ligand binding: when are they applicable and which are the factors that affect their target residence time. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2013, 386, 949–962. 10.1007/s00210-013-0881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tränkle C.; Weyand O.; Voigtländer U.; Mynett A.; Lazareno S.; Birdsall N. J. M.; Mohr K. Interactions of orthosteric and allosteric ligands with [3H]dimethyl-W84 at the common allosteric site of muscarinic M2 receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 64, 180–190. 10.1124/mol.64.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M.; Pop N.; Hutzler C.; Beck-Sickinger A. G.; Bernhardt G.; Buschauer A. Guanidine–acylguanidine bioisosteric approach in the design of radioligands: synthesis of a tritium-labeled NG-propionylargininamide ([3H]-UR-MK114) as a highly potent and selective neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor antagonist. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 8168–8172. 10.1021/jm801018u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane B. E.; Grant M. K. O.; El-Fakahany E. E.; Ferguson D. M. Synthesis and evaluation of xanomeline analogs—Probing the wash-resistant phenomenon at the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 1376–1392. 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen V. I.; Baumgold J.; Jin B.; De la Cruz R.; Rzeszotarski W. J.; Reba R. C. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of some 5-[[[(dialkylamino)alkyl]-1-piperidinyl]acetyl]-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,e][1,4]diazepin-11-ones as M2-selective antimuscarinics. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 162–165. 10.1021/jm00053a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.