Abstract

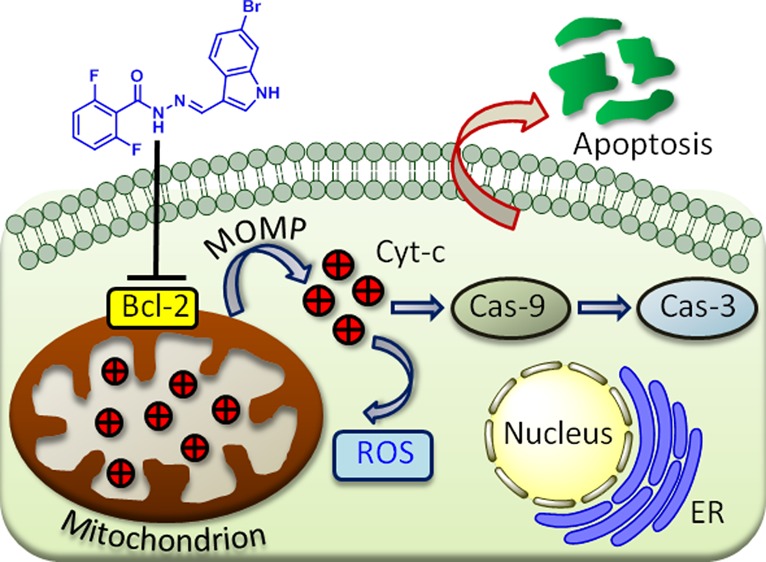

Mitochondrion has emerged as one of the unconventional targets in next-generation cancer therapy. Hence, small molecules targeting mitochondria in cancer cells have immense potential in the next-generation anticancer therapeutics. In this report, we have synthesized a library of hydrazide–hydrazone-based small molecules and identified a novel compound that induces mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization by inhibiting antiapoptotic B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family proteins followed by sequestration of proapoptotic cytochrome c. The new small molecule triggered programmed cell death (early and late apoptosis) through cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and caspase-9/3 cleavage in HCT-116 colon cancer cells, confirmed by an array of fluorescence confocal microscopy, cell sorting, and immunoblotting analysis. Furthermore, cell viability studies have verified that the small molecule rendered toxicity to a panel of colon cancer cells (HCT-116, DLD-1, and SW-620), keeping healthy L929 fibroblast cells unharmed. The novel small molecule has the potential to form a new understudied class of mitochondria targeting anticancer agent.

1. Introduction

Colon cancer is the third most devastating disease claiming nearly 0.7 million deaths per year globally.1,2 Numerous Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved small-molecule drugs (5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan) are already in clinics for the treatment of colon cancer patients under chemotherapy regimen.3−5 However, small-molecule anticancer drugs kill healthy cells along with targeted cancer cells as a collateral damage to induce severe toxic side effects to the patients. Moreover, most of the cancer cells develop resistance mechanisms (intrinsic or extrinsic) to overcome the effect of the drugs.6−9 Hence, there is an urgent need to develop novel small molecules to perturb unconventional subcellular targets as the next-generation cancer therapeutics. In recent years, the understanding of biological function beyond ATP (energy currency) generation prompted mitochondrion as an alternative target for anticancer therapy.

Mitochondrion, the powerhouse of the cells, is one of the most important subcellular organelles that contains genomic materials and plays a central role in innumerable cellular processes including bioenergetics, metabolism, biosynthesis, signal transduction, and apoptosis.10−15 Subsequently, mitochondrial functions have been altered in different types of cancers16−19 making mitochondrion as one of the unorthodox targets for cancer chemotherapy.20−23 As a result, several conventional anticancer drugs were routed into mitochondria for improving efficacy, evading drug resistance, and reducing off-target toxicity.24−28 Recently, mitochondrion was found to play a crucial role in colon cancer development and progression.29,30 Although natural products and synthetic small molecules have evolved as powerful tools to perturb and understand biological phenomena,31−34 development of novel small molecules to impair mitochondrial functions selectively in cancer cells, especially in colon cancer, remains a daunting task,35−37 hence mostly underexplored.

In recent years, hydrazine, hydrazone, and hydrazide-based compounds having nitrogen–nitrogen (N–N) bond have emerged as interesting natural and non-natural products.38,39 Similarly, hydrazide–hydrazone (−CO–NH–N=CH−) derivatives (a fusion of hydrazide and hydrazone moieties) demonstrated significant diverse biological effects including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antimalarial, and anticancer activities (Scheme 1a).40−46 Although hydrazide–hydrazone derivatives have shown immense potential as future anticancer drug candidates, their effect on mitochondrion (intrinsic program cell death mediator) in cancer cells is completely unexplored.

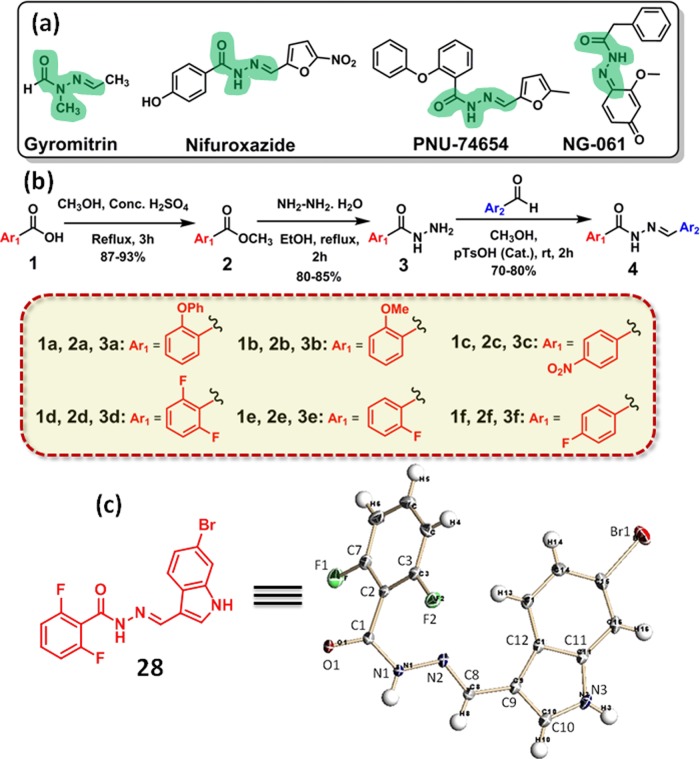

Scheme 1. (a) Chemical Structures, (b) Synthetic Scheme, and (c) Chemical Structure and the ORTEP Diagram.

(a) Chemical structures of hydrazide–hydrazone containing biologically active natural products. (b) A synthetic scheme of hydrazide–hydrazone-based small-molecule library. (c) Chemical structure and the ORTEP diagram of compound 28 with 50% thermal ellipsoids.

To address this, herein, we illustrate a short and easy synthesis of hydrazide–hydrazone-based library. Screening of the library members in colon cancer cell lines (HCT-116, DLD-1, and SW-620) yielded a novel small molecule that can damage the mitochondria through Bcl-2 inhibition-mediated outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP). This mitochondrial impairment released cytochrome c, generated reactive oxygen species (ROS), and finally induced apoptosis through cell cycle arrest and caspase-9/3 cleavage.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of Hydrazide–Hydrazone Library and Characterization

The synthesis of hydrazide–hydrazone library is described in Scheme 1b. First, benzoic acid derivatives (1a–f) are reacted with methanol in the presence of concentrated sulfuric acid in refluxing condition to obtain the methyl esters (2a–f) in 87–93% yield. The methyl-benzoate derivatives (2a–f) are further reacted with hydrazine monohydrate in ethanol in the refluxing condition to afford benzoic acid-based hydrazides (3a–f) in 80–85% yield (Figure S1). Finally, aromatic hydrazides (3a–f) are reacted with aromatic aldehydes in the presence of catalytic p-TsOH to generate hydrazide–hydrazone derivatives (4) in 70–80% isolated yield. A library of 30 hydrazide–hydrazone compounds (5–34, Figure S2) is synthesized by this strategy. Chemical structures of all of the library members are confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR and high-resolution mass spectroscopy (HR-MS) (Figures S3–S92).

2.2. Screening of Hydrazide–Hydrazones in Colon Cancer Cells

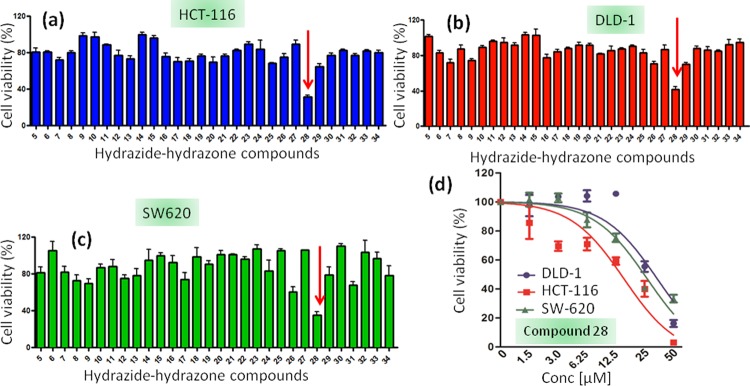

First, the hydrazide–hydrazones are screened to check their ability to induce cell death in colon cancer cells. As there is no previous study of hydrazide–hydrazone derivatives in colon cancer cells, we intend to generate a single-point data using one concentration for each compound in a high-throughput screening method.47,48 We choose a high initial concentration (30 μM) to avoid false-negative and false-positive hits at lower concentration. Moreover, the nontoxic molecules in high concentration should be easily eliminated for further studies. Hence, HCT-116, DLD-1, and SW-620 colon cancer cells are treated with hydrazide–hydrazone derivatives at 30 μM concentration and the cell viability is assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay at 24 h after incubation. Interestingly, it was found that only compound 28 (Scheme 1c, Figure S2) induces 31.7 ± 1.7, 41.7 ± 3, and 35.4 ± 3.4% cell viability in HCT-116, DLD-1, and SW-620 cells, respectively, at 30 μM concentrations (Figure 1a–c). The rest of the library members show negligible cell death even at 30 μM after 24 h.

Figure 1.

MTT assay of hydrazide–hydrazone derivatives in (a) HCT-116, (b) DLD-1, and (c) SW-620 cells at 30 μM concentration after 24 h of incubation. (d) Dose-dependent cell viability assay of compound 28 in HCT-116, DLD-1, and SW-620 cells at 24 h after incubation.

The dose-dependent cytotoxicity of compound 28 is estimated further in HCT-116, DLD-1, and SW-620 cells by MTT assay 24 h after incubation. Compound 28 demonstrates IC50 = 20.0 ± 2.7, 27.7 ± 1.8, and 20.5 ± 0.5 μM (with cell viability = 3.15 ± 0.9, 16.2 ± 2.4, and 33.3 ± 2.6% at 50 μM) in HCT-116, DLD-1, and SW-620 cells, respectively (Figure 1d). To compare the potential of compound 28 to induce cell death in colon cancer cells with other traditional chemotherapeutic drugs used in clinics, we treat HCT-116 cells with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), camptothecin, and cisplatin in a dose-dependent manner for 24 h and evaluate the cell viability by the MTT assay. Interestingly, it is observed that 5-FU, camptothecin, and cisplatin show a much higher IC50 = 57.3 ± 3.6 μM (cell viability = 57.3 ± 3.6% at 50 μM), 44.5 ± 2.9 μM (cell viability = 44.5 ± 2.9% at 50 μM), and 24.6 ± 0.5 μM (cell viability = 33.9 ± 1.8% at 50 μM), respectively (Figure S93). Furthermore, we want to check if the dissociation components of compound 28 in the acidic medium can induce cellular toxicity. Hence, HCT-116 cells are treated with 2,6-difluorobenzohydrazide (3d in Figure S1) and 6-bromo-1H-indole-3-carbaldehyde in a dose-dependent manner for 24 h, and the cell viability is measured by the MTT assay. It is observed that both compounds show negligible toxicity (Figure S94) toward HCT-116 cells.

One of the major challenges in the current cancer therapy is to target cancer cells selectively while keeping normal healthy cells unperturbed. To evaluate the effect in healthy cells, we treat L929 fibroblast cells with compound 28 in a dose-dependent manner at 24 h after incubation. The cell viability is measured by the MTT assay. Interestingly, compound 28 shows almost no toxicity (cell viability = 96.67 ± 6.3%, n = 3, mean ± SEM) to L929 cells even at a higher concentration of 100 μM (Figure S95). On the other hand, cisplatin, camptothecin, and 5-FU shows dose-dependent toxicity in L929 with 78.3, 63.5, and 72.0% cell viability, respectively, at 100 μM concentration at 24 h after incubation (Figure S96). These MTT assays provide a convincing evidence that compound 28 can kill colon cancer cells much efficiently compared to clinically approved traditional cytotoxic drugs while keeping healthy cells unharmed.

We further characterize the structure of the lead compound 28 by X-ray crystallography (Scheme 1c). The purity of compound 28 is also evaluated to be 98.6% by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Figure S97). The hydrazone and hydrazide functionalities are known to be labile in an acidic medium.49 Hence, to be successful in targeting subcellular organelles in colon cancer, compound 28 should be stable in an acidic tumor environment. The stability of compound 28 in an acidic medium is further evaluated. Compound 28 is incubated in pH = 5.5 buffer for short (24 h) and longer (72 h) time, and its integrity is confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF). From the MALDI-TOF spectroscopy (Figures S98 and S99), the fact that compound 28 remains stable in an acidic milieu even after 72 h indicates its potential for therapeutic application in cancer.

2.3. Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Permeabilization (MOMP)

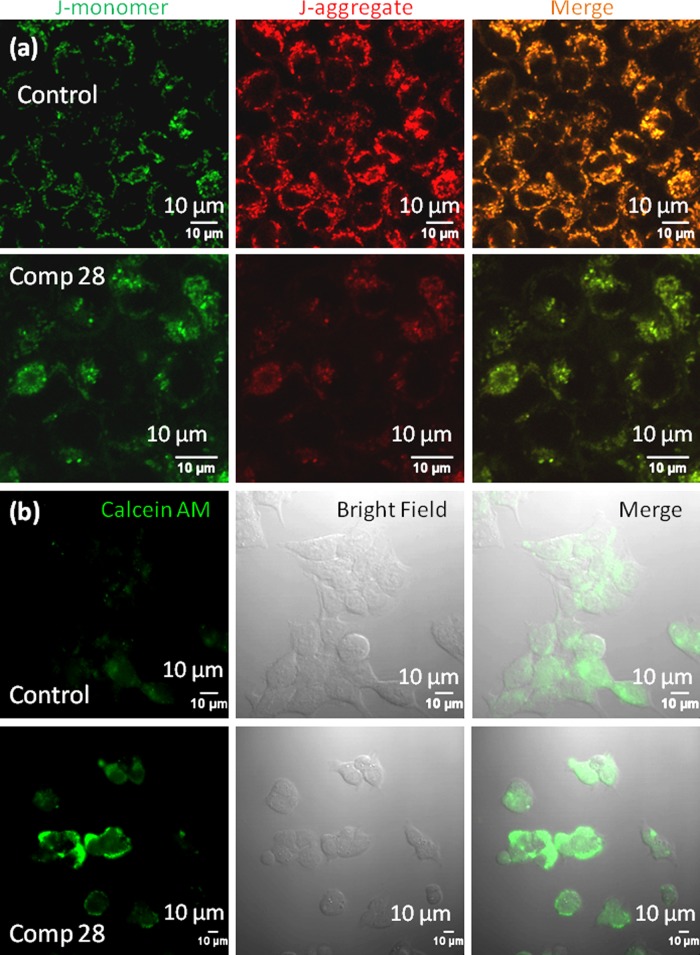

One of the hallmarks of cancer cells is to resist cellular death.50,51 Mitochondria play a crucial role in controlling cancer cell death by inducing mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP).15,52−54 To evaluate the effect of compound 28 on mitochondria in colon cancer cells, the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) is investigated by JC1 assay. 5,5′,6,6′-Tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolocarbocyanine iodide (JC1), a cationic carbocyanine dye, shows membrane potential-dependent homing into mitochondria with a switch from green (∼525 nm) to red (∼590 nm) in fluorescence emission by forming J-aggregates (red fluorescence) in a higher concentration. We estimate the mitochondrial membrane permeabilization by the increase in green/red fluorescent intensity ratio.55 HCT-116 cells are treated with compound 28 at 15 μM (sub-IC50 concentration to avoid cell death, stress response, and morphology change) for 24 h and the cells stained with the JC1 dye. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) is performed to visualize the live stained cells. Figure 2a shows that cells treated with compound 28 induce a significant increase in the green/red ratio (green/red = 1.06 ± 0.2) compared to control nontreated cells (green/red = 0.51 ± 0.2) (Figure S100). This confocal microscopy of JC1 assay confirms that compound 28 induces mitochondrial membrane permeabilization.

Figure 2.

Confocal microscopy images of HCT-116 cells treated with compound 28 followed by (a) JC1 staining to observe mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and (b) calcein acetoxymethyl ester (AM) staining to observe mitochondrial transition pore opening (MTPs). Scale bar = 10 μm.

2.4. Mitochondrial Transition Pore (MTP) Formation

Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization leads to the opening of mitochondrial transition pores (MTPs). Further opening of the MTPs is assessed by calcein acetoxymethyl ester (calcein AM) assay, where calcein AM penetrates into the cells and homes into cytosol and mitochondria.56 Subcellular esterases cleave acetoxymethyl esters into acid functionality to release green fluorescent calcein, which is quenched with the externally added CoCl2 while keeping the mitochondrial calcein AM unperturbed. However, upon opening MTPs, the mitochondrial calcein AM will be sequestered into cytosol, leading to the production of green fluorescent calcein. To evaluate MTP formation, HCT-116 cells are treated with compound 28 for 24 h and stained with calcein AM and CoCl2. As the control, HCT-116 cells are treated with only calcein AM and CoCl2 without compound 28. Live cells are further imaged with CLSM. Figure 2b confirms that compound 28 significantly increases the sequestration of green fluorescent calcein in cytosol compared to the control cells. This calcein AM assay evidently validates that compound 28 damages mitochondria and opens up MTPs in HCT-116 colon cancer cells.

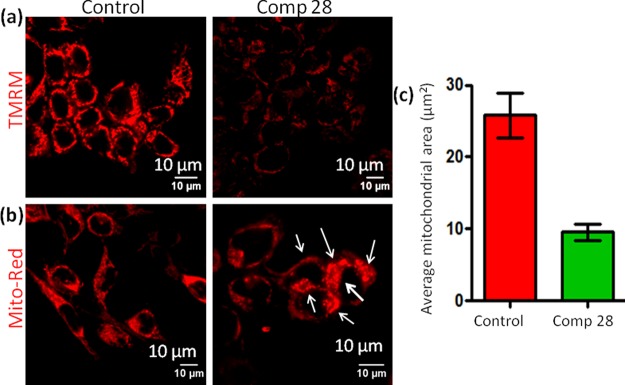

2.5. Induction of Mitochondrial Damage

Mitochondrial outer membrane polarization and transition pore formation diminish mitochondrial hyperpolarization. To evaluate whether compound 28 can reinstate the hyperpolarization of HCT-116 cells, we perform tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) assay.57 Ideally, cancer cells acquire significantly higher hyperpolarized Δψm, leading to the accumulation of red fluorescent TMRM in control cells. However, compound 28 (15 μM) treatment for 24 h reverses the mitochondrial hyperpolarization, leading to an efflux of TMRM from HCT-116 cells. As a result, a significant reduction in red fluorescent intensity is observed by CLSM (Figure 3a). The transition pore opening and reduction of Δψm mediated by mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) leads to mitochondrial structural damage.

Figure 3.

Confocal microscopy images of HCT-116 cells treated with compound 28 followed by (a) staining with red fluorescent TMRM to evaluate mitochondrial depolarization after treatment with compound 28 and (b) MitoTracker Red CMXRos to observe damaged mitochondrial morphology. Scale bar = 10 μm. (c) Quantification of mitochondrial area after treatment with compound 28 determined from CLSM using Mito-Morphology macro and ImageJ analysis software.

We further estimate the damage to the mitochondrial morphology induced by compound 28. HCT-116 cells are treated with compound 28 (15 μM) for 24 h and mitochondria are stained with MitoTracker Red CMXRos. Confocal microscopy images in Figure 3b exhibit that elongated healthy mitochondrial morphology is visibly disrupted into punctated structure (shown by white arrows), leading to mitochondrial damage by compound 28 treatments. Further quantification of the average mitochondrial area is performed by Mito-Morphology macro, which measures mitochondrial elongation and morphology from confocal images through an ImageJ analysis software.58 Mitochondrial average area for HCT-116 cells treated with compound 28 is found to be significantly less (9.54 ± 0.6 μm2, n = 3, mean ± SEM) compared to the average mitochondrial area in control cells (25.8 ± 1.8 μm2, n = 3, mean ± SEM) (Figure 3c). These confocal microscopy images clearly demonstrate that compound 28 damages mitochondria by inducing MOMP.

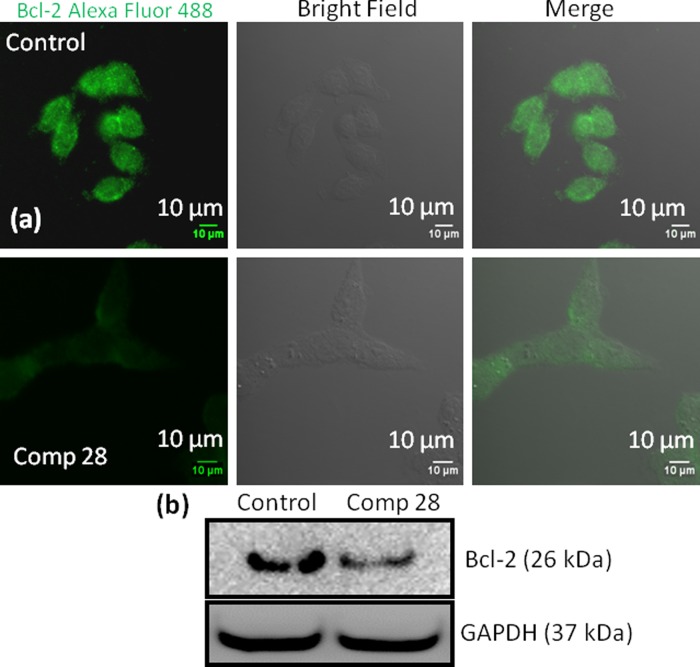

2.6. Bcl-2 Inhibition

MOMP is tightly controlled by the Bcl-2 (B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2) family proteins.53 As a result, small molecules inhibiting Bcl-2 proteins have emerged as potent anticancer drugs.59 To evaluate the effect on Bcl-2, we treat HCT-116 cells with compound 28 for 24 h, and Bcl-2 protein is stained with a green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 labeled antibody. The CLSM images in Figures 4a and S101 confirm that compound 28 inhibits the expression of Bcl-2 proteins compared to nontreated control cells. Furthermore, we estimate the expression of Bcl-2 by western blot analysis. HCT-116 cells are treated with compound 28, and the expression of Bcl-2 protein is visualized by gel electrophoresis. Figure 4b shows that compound 28 reduces the expression of Bcl-2 protein significantly compared to nontreated control cells. We also quantify the expression of Bcl-2 from gel electrophoresis by normalizing the respective GAPDH expression. It is observed that compound 28 reduces the expression of Bcl-2 1.2-fold compared to control cells (Figure S102). These confocal microscopy and protein expression from western blotting experiments confirm that compound 28 induces mitochondrial damage by inhibiting Bcl-2 proteins on the mitochondrial outer membrane.

Figure 4.

(a) Confocal microscopy images of HCT-116 cells treated with compound 28 followed by staining with green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 labeled Bcl-2 antibody. Scale bar = 10 μm. (b) Western blot analysis to evaluate cytochrome c expression in HCT-116 cells after treatment with compound 28 for 24 h.

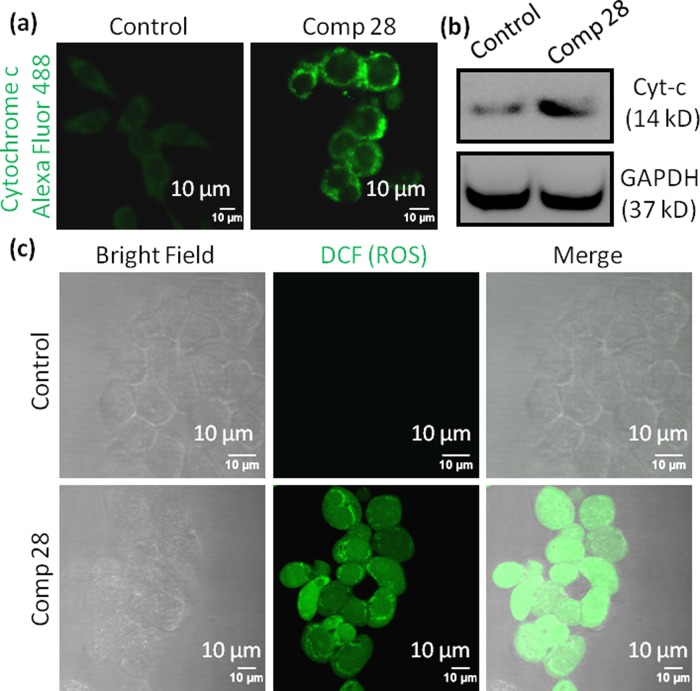

2.7. Cytochrome c Release

Mitochondrial damage directs the translocation of proapoptotic cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol to trigger a programmed cell death.15,60 To visualize the expression of cytochrome c, HCT-116 cells are treated with compound 28 (15 μM) for 24 h and cytochrome c is stained with antibody tagged with green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488. The confocal images (Figure 5a) evidently confirm that compound 28 induces a significantly increased cytochrome c in cytosol compared to nontreated control cells. Further, expression of cytochrome c is determined by western blot analysis after treatment of HCT-116 cells with compound 28 (15 μM) for 24 h. Gel electrophoresis images (Figure 5b) demonstrate a significant increase in the expression of cytochrome c in cells treated with compound 28 compared to control cells. We also quantify the expression of cytochrome c from the western blot. It is found that compound 28 treatment increases cytochrome c expression by 2.2-fold compared to the control cells (Figure S103). These confocal images and gel electrophoresis assays demonstrate that compound 28 induces the release of proapoptotic cytochrome c after mitochondrial damage.

Figure 5.

(a) Confocal images of HCT-116 cells treated with compound 28 for 24 h. Cells were stained with green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 labeled cytochrome c antibody. (b) Western blot analysis to evaluate cytochrome c expression in HCT-116 cells after treatment with compound 28 for 24 h. (c) Confocal images of HCT-116 cells stained with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) to observe reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by compound 28 at 24 h after incubation. Scale bar = 10 μm.

2.8. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation

One of the hallmarks of mitochondrial damage through MOMP is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).15 We evaluate the MOMP-mediated ROS generation by cell-permeable 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) assay.61 H2DCFDA is a nonfluorescent probe, which upon cellular internalization, gets hydrolyzed by esterases followed by oxidation by reactive oxygen species (ROS) to generate green fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF). To evaluate the ROS generation, HCT-116 cells are incubated with compound 28 (15 μM) for 24 h followed by staining the cells with H2DCFDA. The live cells are visualized by confocal microscopy. Figure 5c unmistakably demonstrates that cells treated with compound 28 generates a significantly increased ROS, leading to the production of a much improved green fluorescent DCF compared to control cells. These CLSM images indicate that compound 28 generates ROS through mitochondrial damage.

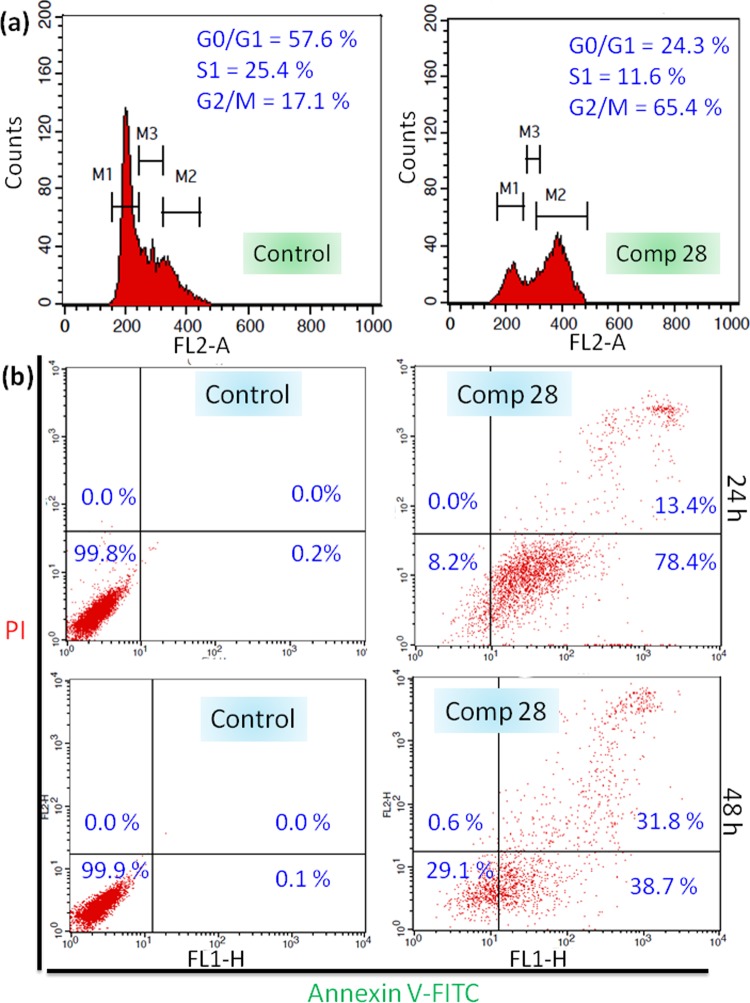

2.9. Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis Induction

Mitochondrial damage, followed by the production of proapoptotic cytochrome c and ROS, instigates cell cycle arrest before apoptosis.62 We measure the cell cycle arrest induced by compound 28 by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) analysis. HCT-116 cells are incubated with compound 28 (15 μM) for 24 h and cell cycle arrest is analyzed by propidium iodide (PI)-labeled DNA. Flow cytometric analysis reveals that compound 28 treatment leads to 24.3, 11.6, and 65.4% cells into G0/G1, S1, and G2/M phase, respectively (Figure 6a). In contrast, 57.6, 25.4, and only 17.1% cells are found in G0/G1, S1, and G2/M phase, respectively, in nontreated control cells. These FACS analyses show evidently that compound 28 arrests HCT-116 cells into the G2/M phase.

Figure 6.

(a) Cell cycle analysis by staining the DNA in HCT-116 cells with PI at 24 h after incubation with compound 28. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of HCT-116 cells after treatment with compound 28 for 24 and 48 h to observe apoptosis (lower left, lower right, upper left, and upper right quadrants represent healthy, early apoptotic, necrotic, and late apoptotic cells, respectively).

Subsequently, cell cycle arrest pushes the cells into programmed cell death or apoptosis.62 We further evaluate the induction of apoptosis by FACS analysis. HCT-116 cells are treated with compound 28 (15 μM) for 24 and 48 h followed by staining apoptotic and necrotic cells by green fluorescent fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled annexin V (staining the flipped phosphatidylserine at the outer surface of apoptotic cells) and red fluorescent PI (staining the DNA of the late apoptotic and necrotic cells), respectively. After 24 h, with compound 28 treatment 78.4 and 13.4% cells are found in early and late apoptosis stages respectively (Figure 6b, upper panel). In comparison, only 0.2 and 0% cells are found in early and late apoptotic stages, respectively, in control cells. Similarly, at 48 h after incubation, 38.7 and 31.8% cells are observed in early and late apoptotic stages in compound 28 treatments, respectively (Figure 6b, lower panel). We anticipate that prolonged exposure of colon cancer cells to mitochondria-damaging compound 28 shifts the programmed cell death from early to late stages of apoptosis. These FACS analyses demonstrate that compound 28 induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells through mitochondrial damage.

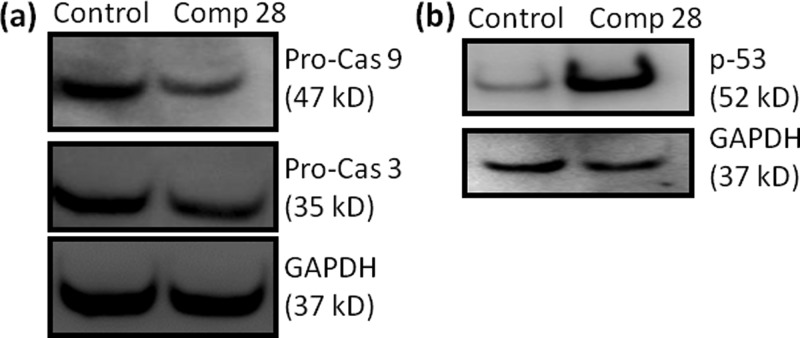

2.10. Caspase-9/3 and p53 Expression

Induction of apoptosis in cancer cells activates the initiator caspase-9, which further activates the activator caspase-3 after cleavage.63,64 We estimate the expression of caspase-9 and caspase-3 by western blot analysis in HCT-116 cells at 24 h after incubation with compound 28 (15 μM). Gel electrophoresis reveals that compound 28 triggered the cleavage of caspase-9 and caspase-3 compared to control cells (Figure 7a). Further quantification from western blot shows that compound 28 reduces the expression of caspase-3 and caspase-9 by 1.6- and 2.5-folds, respectively (Figure S104a). These gel electrophoresis studies undoubtedly exhibit that compound 28 induced apoptosis in HCT-116 cells through the cleavage of caspase-9 and caspase-3.

Figure 7.

(a) Western blot analysis to observe the expression of (a) procaspase-9, procaspase-3, and (b) p-53 in HCT-116 cells after treatment with compound 28 for 24 h.

Mitochondria-mediated apoptosis is highly dependent on p53 protein, which is one of the most important tumor suppressors.65 Moreover, Bcl-2 inhibition on mitochondria in colon cancer triggers the cells into p53-driven apoptosis.66 Hence, we further evaluate the expression of p53 in mitochondrial damage mediated by compound 28, followed by apoptosis. We treat HCT-116 cells with compound 28 (15 μM) for 24 h and assess the expression of p53 by western blot analysis. The gel electrophoresis image in Figure 7b confirms that compound 28 remarkably increases the expression of p53 compared to control cells. Further quantification from gel electrophoresis shows that compound 28 increases the expression of p53 in HCT-116 cells 14.7-folds compared to control cells (Figure S104b).

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, this report describes a straightforward and concise synthesis of natural product-guided hydrazide–hydrazone-based small-molecule library. One of the library members was discovered to impair mitochondria by disrupting outer membrane through the inhibition of Bcl-2 protein followed by production of reactive oxygen species. This small molecule blocked the cell cycle in G2/M phase, cleaved caspase-9/3, and increased p53 to stimulate programmed cell death in colon cancer cells. This hydrazide–hydrazone-based small molecule showed remarkable efficacy in a panel of colon cancer cell lines, without collateral toxicity in healthy cells. We anticipated this novel small molecule had the potential to become a tool to illuminate mitochondrial biology and further optimization studies need to be performed for translating it successfully into clinics as an anticancer agent.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Commercially available chemicals and solvents were used without further purification and distillation. Chemical reactions were carried out without any inert gas condition. Precoated silica gel aluminum sheets 60F254 for analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) were obtained from EMD Millipore Laboratories. Cell culture media (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from HiMedia. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), Hanks’ balanced salts, N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-ethanesulfonic acid sodium salt, propidium iodide, calcein AM, Annexin V-FITC Staining Kit and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. MitoTracker Red CMXRos and tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate (TMRM) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. All of the primary and secondary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Biolegend, and Abcam. Confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed by a Zeiss LSM 710 machine. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using a BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer. Each sample was done in triplicate.

4.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Benzoic Acid Methyl Esters (2a–f)

Substituted benzoic acids (0.5 g) were dissolved in absolute methanol (8 mL), followed by the addition of concentrated sulfuric acid (0.3 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed, and the progress of the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). After completion of the reaction, methanol was evaporated under reduced pressure. To the residue aqueous 10% sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) (15 mL) was added, extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 20 mL), and washed with saturated NaCl solution (2 × 10 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and the organic solvent was evaporated to get methyl esters of substituted benzoic acid in 87–93% yield as a light yellow viscous liquid.

4.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Benzoic Acid Hydrazides (3a–f)

Substituted benzoic acid methyl esters (2a–f) (0.4 g, 1 equiv) were dissolved in absolute ethanol (3 mL) and hydrazine monohydrate (1.183 mL, 10 equiv) was added into it. The reaction was refluxed and monitored by TLC. After the completion of the reaction, ethanol was evaporated. To the residue, ice-cold water (10 mL) was added and the organic layer was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 20 mL). The organic layer was further washed with saturated NaCl solution (2 × 10 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and the solvent was evaporated. Finally, the crude product was recrystallized (ethanol–water) to obtain the desired hydrazides in 80–85% yield.

4.4. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Hydrazide–Hydrazone Derivatives (5–34)

To the solution of substituted benzoic acid hydrazides (3) (0.1 g, 1 equiv) in absolute methanol (1.5 mL), different aromatic aldehydes (1 equiv) were added, followed by the addition of catalytic amount of p-toluenesulfonic acid (pTsOH). After stirring for 2 h at room temperature, methanol was evaporated under reduced pressure. To the residue, aqueous 10% NaHCO3 (10 mL) was added and the organic layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL) followed by washing with saturated NaCl solution (2 × 10 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and the solvent was evaporated. Final compounds were purified by using column chromatography on the basic aluminum oxide (Al2O3) (ethyl acetate/hexane = 20%) to give hydrazide–hydrazone derivatives in 70–80% yield.

4.5. HPLC Analysis

The purity of compound 28 was determined by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using a 4.6 × 250 mm 5 μm C18 column using acetonitrile/water with gradient for 10 min. The sample (20 μL) was injected (concentration = 1 mg/mL) into the column with 1 mL/min flow rate.

4.6. Cell Viability Assay

Five thousand colorectal cancer cells (DLD-1, HCT-116, and SW-620) were seeded per well in a 96-well plate for attachment. To screen all of the compounds, 3 mM stock solutions of all of the compounds were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The cells were then treated with all of the compounds (30 μM) for 24 h. For calculation of IC50, the cells were treated with compound 28 in different concentrations (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, 6.4, 12.5, 25, and 50 μM). Cell viability was determined by adopting the previously described procedure.67

For fibroblast cells, 10 000 L929 (murine lung fibroblast) cells were plated in each well of a 96-well plate and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C overnight. Drug dilutions were made in complete 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-containing DMEM media. Hundred microliter of each drug solutions (diluted in DMSO) was added in each well of the 96-well plate (in triplicates). Untreated cells (without any drug) were considered as control. After adding drugs, the cells were incubated for 24 h. After 24 h, media were aspirated and 100 μL MTT reagent (10 μL of 5 mg/mL solution and 90 μL sterile media) was added in each well. It was incubated for 3 h. Finally, all of the media were aspirated. Formazan crystals were dissolved in100 μL DMSO and read in a plate reader having 550 nm cutoff filter. Percent cell death calculation data were normalized with untreated cells. Each data represent an average of 3 data points. Error calculated as standard error following (STDEV/(SQRT(3))) using Microsoft excel.

4.7. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

1.5 × 104 HCT-116 cells were seeded in each well in 8-well Lab-Tek chamber slides for attachment. Compound 28 (15 μM) was incubated with the cells for 24 h. Control cells were not treated with any compound.

4.7.1. JC1 Assay

Cells were washed thoroughly with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by the addition of JC1 dye to incubate for 20 min. The green and red fluorescently labeled cells were seen and quantified by confocal microscopy.68

4.7.2. Calcein AM Assay

After 24 h, calcein AM (1 μM) and 1 mM CoCl2 were added into the cells, followed by imaging through confocal microscopy.68

4.7.3. Mitochondrial Morphology Assay

After 24 h of incubation with compound 28, the cells were washed thoroughly with PBS and stained with MitoTracker Red CMXRos for 20 min. The cells were then treated with paraformaldehyde (4%) for 10 min and visualized and quantified by CLSM.67

4.7.4. ROS Generation by DCFH-DA Assay

After treatment with compound 28, the cells were then washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and treated with DCFH-DA for 15 min. Finally, the cells were washed thrice with PBS (pH 7.4) and visualized by CLSM.

4.7.5. TMRM Assay

The cells were washed with cold PBS 3 times and treated with TMRM (10 μM/mL) for 30 min. The cells were then washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and imaged by CLSM to visualize mitochondrial damage.

4.7.6. Immunostaining To Visualize Cytochrome c

5 × 104 HCT-116 cells were attached on the coverslip in a 6-well plate followed by incubation with compound 28 for 24 h. The cells were thoroughly rinsed with PBS and fixed with paraformaldehyde (4%) for 10 min. The cells were then further washed and permeabilized by blocking buffer. The cells were then treated with cytochrome c primary antibody solution (1:100 dilution) for 3 h. After further washing with blocking buffer, the cells were treated with a Alexa Fluor 488 labeled secondary antibody solution (1:500 dilution) for 30 min in dark. Fluorescently labeled cells were visualized further by CLSM.67

4.7.7. Immunostaining To Visualize Bcl-2

After treatment with compound 28, the cells were washed once with PBS and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde at 37 °C for 15 min. The cells were further washed twice with PBS (pH = 7.4) and permeabilized by incubating in blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.3% Tween and 5% FBS) at room temperature. The cells were then incubated in Bcl-2 primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) in 1:100 dilution at 37 °C for 3 h. The cells were washed thrice with blocking buffer followed by incubation in Alexa Fluor 488 antimouse IgG secondary antibody solution (1:500 dilutions) at 37 °C for 40 min in the dark. The cells were washed thrice with PBS and mounted on a glass slide using SlowFade Gold antifade reagent. The slides were subjected to fluorescence imaging using CLSM.

4.8. General Procedure for Western Blot Analysis

1 × 105 HCT-116 cells were treated with compound 28 for 24 h followed by cell lysis. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was used to separate respective proteins and transferred them onto the membrane by electroblotting. The protein-containing membranes were blocked and incubated with primary antibodies for 24 h at 4 °C. Further, the membrane was washed and incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at 25 °C. Proteins were then detected and quantified by an ImageQuant LAS 4000 and an ImageJ software.67,68

4.9. Fluorescence-Activated Cell-Sorting (FACS) Assay

HCT-116 cells (2 × 106 cell per well) were attached in 6-well plates and then treated with compound 28 for 24 h at 15 μM.

4.9.1. Apoptosis Detection

The cells were detached by using trypsin and washed with PBS. The suspended cells were then incubated with Annexin V-FITC Staining Kit using the manufacturer’s protocol. The apoptotic and necrotic cells were quantified by using a BD Accuri c6 flow cytometer.67

4.9.2. Cell Cycle Analysis

After treatment with compound 28, the cells were then harvested and washed with 1 mL PBS (pH = 7.4) and centrifuged at 850 rpm for 4 min. After discarding the supernatant, the cells was fixed with cold 70% EtOH for 0.5 h. The cells were washed thoroughly with PBS, followed by the addition of 500 μL staining solution. A BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer was used for cell cycle analysis.67

Acknowledgments

S.B. sincerely acknowledges the financial support from the Department of Biotechnology (Ramalingaswami Fellowship: BT/RLF/Re-entry/13/2011, BT/PR9918/NNT/28/692/2013, and BT/PR14724/NNT/28/831/2015). S. Patil and S. Palvai are thankful to the CSIR-UGC for doctoral fellowship. P.S. is thankful to the DST Women Scientist Scheme-A (SR/WOS-A/CS94/2012) for funding, fellowship, and Academy of Scientific & Innovative Research (AcSIR) for Ph.D. registration. We thank Mr. Amol Gade from CSIR-NCL for helping in HPLC experiment. We also acknowledge Dr. Nirmalya Ballav, IISER, Pune, for stimulating scientific discussion.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01512.

Characterization data for all of the library members (compounds 5–34), NMR (1H and 13C) and HR-MS spectra of all of the library members (compounds 5–34), cell viability data, RP-HPLC data, MALDI-TOF spectra, JC1 assay quantification, confocal laser scanning microscopy images, and protein quantification from gel electrophoresis (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2011–2013; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J.; Soerjomataram I.; Ervik M.; Dikshit R.; Eser S.; Mathers C.; Rebelo M.; Parkin D. M.; Forman D.; Bray F.. GLOBOCAN 2012, v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11, 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rubbia-Brandt L.; Audard V.; Sartoretti P.; Roth A. D.; Brezault C.; Le Charpentier M.; Dousset B.; Morel P.; Soubrane O.; Chaussade S.; Mentha G.; Terris B. Severe hepatic sinusoidal obstruction associated with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 460–466. 10.1093/annonc/mdh095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André T.; Boni C.; Mounedji-Boudiaf L.; Navarro M.; Tabernero J.; Hickish T.; Topham C.; Zaninelli M.; Clingan P.; Bridgewater J.; Tabah-Fisch I.; de Gramont A. Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin as Adjuvant Treatment for Colon Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2343–2351. 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz H. P.; Weder W.; Largiadèr F. Local and systemic toxicity of intra-hepatic-arterial 5-FU and high-dose or low-dose leucovorin for liver metastases of colorectal cancer. Surg. Oncol. 1994, 3, 11–16. 10.1016/0960-7404(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight Z. A.; Lin H.; Shokat K. M. Targeting the cancer kinome through polypharmacology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 130–137. 10.1038/nrc2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. R.; Fridlyand J.; Yan Y.; Penuel E.; Burton L.; Chan E.; Peng J.; Lin E.; Wang Y.; Sosman J.; Ribas A.; Li J.; Moffat J.; Sutherlin D. P.; Koeppen H.; Merchant M.; Neve R.; Settleman J. Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors. Nature 2012, 487, 505–509. 10.1038/nature11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman M. M.; Fojo T.; Bates S. E. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 48–58. 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holohan C.; Van Schaeybroeck S.; Longley D. B.; Johnston P. G. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 714–726. 10.1038/nrc3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifunovic A.; Wredenberg A.; Falkenberg M.; Spelbrink J. N.; Rovio A. T.; Bruder C. E.; Bohlooly M.; Gidlöf S.; Oldfors A.; Wibom R.; Törnell J.; Jacobs H. T.; Larsson N. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 2004, 429, 417–423. 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. A. J.; Hartley R. C.; Cochemé H. M.; Murphy M. P. Mitochondrial pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 341–352. 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward P. S.; Thompson C. B. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 297–308. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel N. S. Mitochondria as signaling organelles. BMC Biol. 2014, 12, 34–40. 10.1186/1741-7007-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L.; Oliver K.; Guido K. Mitochondria: master regulators of danger signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 780–788. 10.1038/nrm3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait S. W. G.; Green D. R. Mitochondria and cell death: outer membrane permeabilization and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 621–632. 10.1038/nrm2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo S. E.; Mootha V. K. The mitochondrial proteome and human disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2010, 11, 25–44. 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnari J.; Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell 2012, 148, 1145–1159. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogvadze V.; Orrenius S.; Zhivotovsky B. Mitochondria in cancer cells: what is so special about them?. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 165–173. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroughs L. K.; DeBerardinis R. J. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 351–359. 10.1038/ncb3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S.; Galluzzi L.; Kroemer G. Targeting mitochondria for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 447–464. 10.1038/nrd3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg S. E.; Chandel N. S. Targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 9–15. 10.1038/nchembio.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D. C. Mitochondria and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 685–698. 10.1038/nrc3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S.; Zaganjor E.; Haigis M. C. Mitochondria and Cancer. Cell 2016, 166, 555–566. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrache S.; Pathaka R. K.; Dhar S. Detouring of cisplatin to access mitochondrial genome for overcoming resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 10444–10449. 10.1073/pnas.1405244111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrache S.; Dhar S. Engineering of blended nanoparticle platform for delivery of mitochondria-acting therapeutics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 16288–16293. 10.1073/pnas.1210096109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean S. R.; Ahmed M.; Lei E. K.; Wisnovsky S. P.; Kelley S. O. Peptide-Mediated Delivery of Chemical Probes and Therapeutics to Mitochondria. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1893–1902. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisnovsky S.; Lei E. K.; Jean S. R.; Kelley S. O. Mitochondrial Chemical Biology: New Probes Elucidate the Secrets of the Powerhouse of the Cell. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 917–927. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean S. R.; Tulumello D. V.; Wisnovsky S. P.; Lei E. K.; Pereira M. P.; Kelley S. O. Molecular vehicles for mitochondrial chemical biology and drug delivery. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 323–333. 10.1021/cb400821p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A.; Mambo E.; Sidransky D. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4663–4674. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Aragó M.; Chamorro M.; Cuezva J. M. Selection of cancer cells with repressed mitochondria triggers colon cancer progression. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 567–576. 10.1093/carcin/bgq012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübel K.; Leßmann T.; Waldmann H. Chemical biology--identification of small molecule modulators of cellular activity by natural product inspired synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1361–1374. 10.1039/b704729k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S. L. Target-oriented and diversity-oriented organic synthesis in drug discovery. Science 2000, 287, 1964–1969. 10.1126/science.287.5460.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita V. T. Jr.; Chu E. A History of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8643–8653. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler S.; Pries V.; Hedberg C.; Waldmann H. Target identification for small bioactive molecules: finding the needle in the haystack. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2744–2792. 10.1002/anie.201208749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Škrtić M.; Sriskanthadevan S.; Jhas B.; Gebbia M.; Wang X.; Wang Z.; Hurren R.; Jitkova Y.; Gronda M.; Maclean N.; Lai C. K.; Eberhard Y.; Bartoszko J.; Spagnuolo P.; Rutledge A. C.; Datti A.; Ketela T.; Moffat J.; Robinson B. H.; Cameron J. H.; Wrana J.; Eaves C. J.; Minden M. D.; Wang J. C.; Dick J. E.; Humphries K.; Nislow C.; Giaever G.; Schimmer A. D. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation as a therapeutic strategy for human acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 674–688. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Wang J.; Bonamy G. M. C.; Meeusen S.; Brusch R. G.; Turk C.; Yang P.; Schultz P. G. A small molecule promotes mitochondrial fusion in mammalian cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9302–9305. 10.1002/anie.201204589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leanza L.; Romio M.; Becker K. A.; Azzolini M.; Trentin L.; Managò A.; Venturini E.; Zaccagnino A.; Mattarei A.; Carraretto L.; Urbani A.; Kadow S.; Biasutto L.; Martini V.; Severin F.; Peruzzo R.; Trimarco V.; Egberts J. H.; Hauser C.; Visentin A.; Semenzato G.; Kalthoff H.; Zoratti M.; Gulbins E.; Paradisi C.; Szabo I. Direct pharmacological targeting of a mitochondrial ion channel selectively kills tumor cells in vivo. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 516–531. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff G. L.; Ouazzani J. Natural hydrazine-containing compounds: biosynthesis, isolation, biological activities and synthesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 6529–6544. 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair L. M.; Sperry J. Natural products containing a nitrogen-nitrogen bond. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 794–812. 10.1021/np400124n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosset J. Y.; Dalvit C.; Knapp S.; Fasolini M.; Veronesi M.; Mantegani S.; Gianellini L. M.; Catana C.; Sundström M.; Stouten P. F.; Moll J. K. Inhibition of protein-protein interactions: the discovery of druglike beta-catenin inhibitors by combining virtual and biophysical screening. Proteins 2006, 64, 60–67. 10.1002/prot.20955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Mukherjee D.; Kumar N. M.; Tantak M. P.; Das A.; Ganguli A.; Datta S.; Kumar D.; Chakrabarti G. Development of novel bis(indolyl)-hydrazide-hydrazone derivatives as potent microtubule-targeting cytotoxic agents against A549 lung cancer cells. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 3020–3035. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr T.; Bondock S.; Youns M. Anticancer activity of new coumarin substituted hydrazide-hydrazone derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 76, 539–548. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S.; Kaufmann D.; Pojarová M.; Müller C.; Pfaller T.; Kühne S.; Bednarski P. J.; von Angerer E. Aroyl hydrazones of 2-phenylindole-3-carbaldehydes as novel antimitotic agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 6436–6447. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T.; Sun C.; Xing X.; Jing L.; Tan R.; Luo Y.; Huang W.; Song H.; Li Z.; Zhao Y. Synthesis and evaluation of 2-[2-(phenylthiomethyl)-1H-benzo[d] imidazol-1-yl)acetohydrazide derivatives as antitumor agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 3122–3125. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z.; Li Y.; Ling Y.; Huang J.; Cui J.; Wang R.; Yang X. New class of potent antitumor acylhydrazone derivatives containing furan. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 5576–5584. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popiołek Ł. Hydrazide-hydrazones as potential antimicrobial agents: overview of the literature since 2010. Med. Chem. Res. 2017, 26, 287–301. 10.1007/s00044-016-1756-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. P.; Rees S.; Kalindjian S. B.; Philpott K. L. Principles of early drug discovery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 162, 1239–1249. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens K.; Lin W.; Cui J.; Farmer D.; Low J.; Pronier E.; Zeng F. Y.; Shelat A. A.; Guy K.; Taylor M. R.; Chen T.; Roussel M. F. Identification of small molecule activators of BMP signalling. PLoS One 2013, 8, e59045 10.1371/journal.pone.0059045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia J.; Raines R. T. Hydrolytic stability of hydrazones and oximes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 7523–7526. 10.1002/anie.200802651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. R.; Kroeme G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science 2004, 305, 626–629. 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk J. E.; Green D. R. How do BCL-2 proteins induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization?. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 157–164. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk J. E.; Bouchier-Hayes L.; Green D. R. Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization during apoptosis: the innocent bystander scenario. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 1396–1402. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossarizza A.; Baccaranicontri M.; Kalashnikova G.; Franceschi C. A new method for the cytofluorimetric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using the J-aggregate forming lipophilic cation 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 197, 40–45. 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronilli V.; Miotto G.; Canton M.; Brini M.; Colonna R.; Bernardi P.; Lisa F. D. Transient and long-lasting openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore can be monitored directly in intact cells by changes in mitochondrial calcein fluorescence. Biophys. J. 1999, 76, 725–734. 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floryk D.; Houštěk J. Tetramethyl rhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) is suitable for cytofluorometric measurements of mitochondrial membrane potential in cells treated with digitonin. Biosci. Rep. 1999, 19, 27–34. 10.1023/A:1020193906974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda R. K.; Cherra S. J.; Kulich S. M.; Tandon A.; Park D.; Chu C. T. Loss of PINK1 function promotes mitophagy through effects on oxidative stress and mitochondrial fission. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 13843–13855. 10.1074/jbc.M808515200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A.; Fairbrother W. J.; Leverson J. D.; Souers A. J. From basic apoptosis discoveries to advanced selective BCL-2 family inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2017, 16, 273–284. 10.1038/nrd.2016.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X.; Wang X. Cytochrome C-mediated apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004, 73, 87–106. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Yotnda P. Production and detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cancers. J. Visualized Exp. 2011, e3357 10.3791/3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczor C. A.; Shokolenko I. N.; Boyd A. K.; Balk S. P.; Wilson G. L.; LeDoux S. P. Mitochondrial DNA damage initiates a cell cycle arrest by a Chk2-associated mechanism in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 36191–36201. 10.1074/jbc.M109.036020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariño G.; Niso-Santano M.; Baehrecke E. H.; Kroemer G. Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 81–94. 10.1038/nrm3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; Nijhawan D.; Budihardjo I.; Srinivasula S. M.; Ahmad M.; Alnemri E. S. X.; Wang X. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 1997, 91, 479–489. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaseva A. V.; Moll U. M. The mitochondrial p53 pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 414–420. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M.; Milner J. Bcl-2 constitutively suppresses p53-dependent apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 832–837. 10.1101/gad.252603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick A.; More P.; Ghosh S.; Chippalkatti R.; Chopade B. A.; Lahiri M.; Basu S. Dual drug conjugated nanoparticle for simultaneous targeting of mitochondria and nucleus in cancer cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 7584–7598. 10.1021/am5090226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick A.; More P.; Syed M. M.; Basu S. Nanoparticle-mediated mitochondrial damage induces apoptosis in cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 13218–13231. 10.1021/acsami.6b00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.