Abstract

Oncogenic lesions up-regulate bioenergetically demanding cellular processes, such as protein synthesis, to drive cancer cell growth and continued proliferation. However, the hijacking of these key processes by oncogenic pathways imposes onerous cell stress that must be mitigated by adaptive responses for cell survival. The mechanism by which these adaptive responses are established, their functional consequences for tumor development, and their implications for therapeutic interventions remain largely unknown. Using murine and humanized models of prostate cancer (PCa), we show that one of the three branches of the unfolded protein response is selectively activated in advanced PCa. This adaptive response activates the phosphorylation of the eukaryotic initiation factor 2–α (P-eIF2α) to reset global protein synthesis to a level that fosters aggressive tumor development and is a marker of poor patient survival upon the acquisition of multiple oncogenic lesions. Using patient-derived xenograft models and an inhibitor of P-eIF2α activity, ISRIB, our data show that targeting this adaptive brake for protein synthesis selectively triggers cytotoxicity against aggressive metastatic PCa, a disease for which presently there is no cure.

INTRODUCTION

Adaptation to cellular stress, driven by oncogenic lesions, is one of the most fundamental and poorly understood features of cancer cells (1, 2). Multiple oncogenes sustain uncontrolled cancer cell growth and division by stimulating the production of molecular “building blocks,” such as proteins and outputs of anabolic metabolism. However, this poses an onerous expenditure of cellular resources, and it remains poorly understood how cancer cells adapt to this increased metabolic load. One example is an increase in total proteins being synthesized, because cancer cells need to sustain augmented growth and division. For instance, more than 65% of the energy in the cell is devoted to the bioenergetically expensive process of protein synthesis that is greatly increased in most cancers (3). Left unchecked, infinite increases in the cancer cell’s biosynthetic demand would tilt the balance from continuous growth and division to cell death. Therefore, increases of biosynthetic processes place a high demand on cancer cells and are a source of constant stress that must be carefully regulated by the activation of appropriate checkpoints, which remain poorly understood. How then do cancer cells accommodate overwhelming stress such as an increased protein burden? Are cytoprotective responses activated in aggressive disease, and do they represent a point of vulnerability that can be exploited for cancer therapy?

Increased protein synthesis and the flux in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) create a state of proteotoxic stress associated with the accumulation of misfolded proteins (4–6). This ER stress activates the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR is composed of three signaling arms: ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6) with transcriptional activity to promote ER homeostasis, IRE1 (inositol-requiring enzyme 1) to control splicing of the transcription factor XBP1 enhancing ER gene expression, and PERK [PKR (RNA-activated protein kinase)–like ER-associated protein kinase], which promotes downstream phosphorylation of eIF2α (eukaryotic initiation factor 2–α) (P-eIF2α) on serine 51 (4). Unlike the other arms of the UPR, PERK P-eIF2α creates a direct “brake” for general protein synthesis because of the conversion of eIF2 from a substrate of the ternary complex, which is necessary to promote the initiation step of mRNA translation, to an inhibitor of this complex (7, 8). Although UPR activation has been associated with cancer, it remains poorly understood which oncogenes and/or combinations of oncogenes control distinct arms of this pathway in vivo during the initiation or progression of tumor development. It is also unclear whether and when the UPR is activated during the course of cancer evolution, its specific requirements in distinct phases of tumorigenesis, and the potential druggability of this stress adaptation pathway in human cancers.

Here, we set out to address these outstanding questions by investigating cancer development within a specialized secretory epithelial tissue. The prostate is a walnut-sized conglomerate of tubular or saclike glands, dedicated to the production of proteinaceous secretory fluid. One of the early consequences of human primary prostate cancer (PCa) is a major remodeling of the cancer cell proteome associated with increases in protein biosynthesis (9–11). For example, loss of the PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) tumor suppressor and hyperactivation of the oncogene MYC, accounting for nearly 50% of the lethal metastatic form of human PCa (12, 13), have major effects on protein synthesis (14–17). Thus, we reasoned that the prostate would provide a good model to understand the mechanisms by which oncogenic cells buffer the burden of increased protein synthesis to prevent proteotoxic stress during cancer formation.

RESULTS

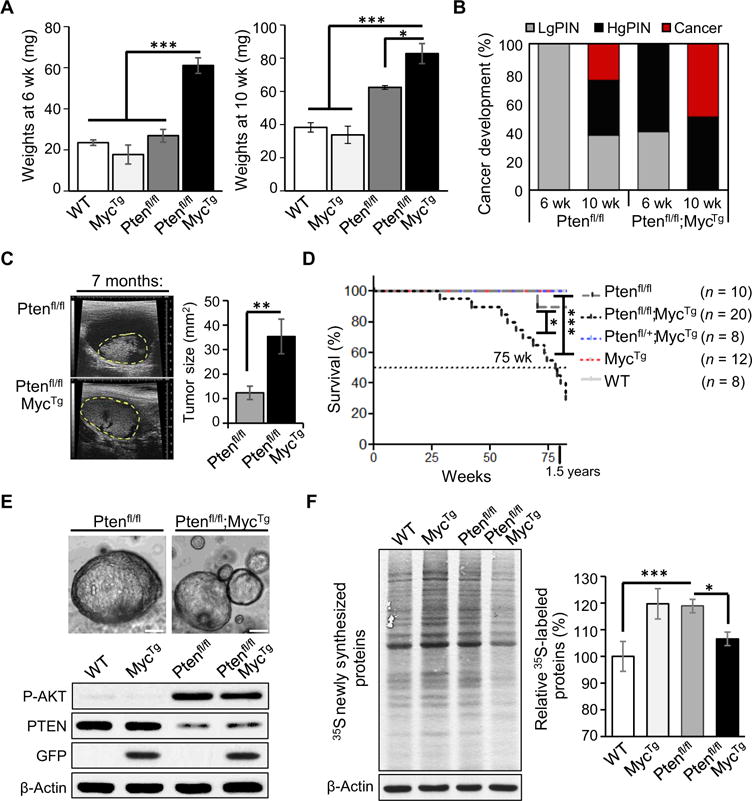

MYC amplification with PTEN loss diminish oncogenic increases of global protein synthesis in lethal murine PCa

We modeled distinct stages of human PCa in the mouse, using a newly generated conditional transgenic MYC mouse, where the overexpression of C-MYC is driven in a Cre-specific manner (MycTg), in combination with the conditional loss of PTEN in the prostate epithelium (Pb-cre4;Ptenfl/fl, herein referred to as Ptenfl/fl) (fig. S1) (18). The advantage of this mouse is that cells overexpressing MycTg can be traced through expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) present in the targeting locus, allowing for visualization of the earliest events in tumorigenesis (fig. S1, A and B). In agreement with the notion that MYC hyperactivation may be a secondary event for human PCa development (19), we find that MYC overexpression alone in prostate epithelium (Pb-cre4;MycTg, herein referred to as MycTg) increased proliferation but did not result in adenocarcinoma by 1 year of age (fig. S1, C to E). This is consistent with previous reports, which showed MYC expression under the control of similar promoters to those used here (20, 21). MycTg mice with concomitant loss of PTEN in prostate tissue (Ptenfl/fl;MycTg) showed significant enlargement of prostate growth by 6 weeks of age (P < 0.0003) and accelerated development of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HgPIN) compared to mice with loss of PTEN alone (Fig. 1, A and B). PTEN loss and MYC amplification cooperated to develop adenocarcinoma by 10 weeks (Fig. 1B), resulting in marked increases in Ptenfl/fl;MycTg tumor size visualized by ultrasound (Fig. 1C). This aggressive oncogenic progression significantly decreased overall survival (P < 0.05), with a mean life span of 75 weeks (Fig. 1D). Collectively, this genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) recapitulates aggressive human PCa and results in decreased survival.

Fig. 1. MycTG and loss of PTEN cooperate for aggressive PCa development, resulting in decreased survival.

(A) Total dehydrated prostate weights from 6- and 10-week-old mice were averaged for each genotype (n = 3 to 6 mice per arm, mean ± SEM). wild-type, WT. (B) Phenotypical penetrance percentages for low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (LgPIN), HgPIN, and cancer in anterior prostate tissues from 6- and 10-week-old mice evaluated by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. (C) Left: Representative ultrasound images of prostate tumors at 7 months outlined in yellow from indicated genotypes; scale bars, 9 mm. Right: Quantification of prostate tumor size in mice with an average age of 8 months (n = 5 mice per arm, mean ± SEM). (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for mice with the indicated genotypes. Dotted line highlights the median life span of 75 weeks for Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice. (E) Top: Representative bright-field images of three-dimensional organoid structures 6 days after seeding; scale bars, 50 μm. Bottom: Western blot analyzing the organoids, showing P-AKT, PTEN, GFP for MycTg, and β-actin. (F) Newly synthesized proteins measured by 35S methionine/cysteine incorporation in organoids (left panel), with quantification relative to WT littermates (right panel) (n = 5, mean ± SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t test.

To evaluate the effects of these key oncogenes on global protein synthesis, we assessed newly synthesized proteins by incorporation of 35S-labeled methionine in organoid cultures. We established primary mouse three-dimensional organoid cultures to recapitulate the cellular environment of the murine prostate gland ex vivo (Fig. 1E) (22). Organoids were derived from dissociated mouse prostate tissue containing a mixed population of luminal and basal cell types to mimic the histology observed in vivo (23). Western blot analysis confirmed that MycTg expression and PTEN loss were evident and associated with increased GFP expression and AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 1E). Consistent with the known ability of these major oncogenic pathways to increase protein synthesis (24, 25), either loss of PTEN or MYC hyperactivation significantly increased global protein synthesis by about 20% (P < 0.0003 for both). On the contrary, we observed an unanticipated but significant dampening in global protein synthesis in Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice (P = 0.01), despite the fact that these mice developed more aggressive PCa (Fig. 1F). This observation revealed an interesting paradox. It suggested that despite the presence of two oncogenic lesions that individually up-regulate protein synthesis, a yet unknown adaptive response may take place when protein synthesis is up-regulated beyond a specific threshold in aggressive PCa.

Aggressive PCa activates a key cellular stress response during tumor development

Proteins that are synthesized in the secretory pathway amount to about 30% of the total proteome in most eukaryotic cells (4, 6). Although UPR activation can be studied with pharmacological inducers of ER stress, under physiological processes, the activation of the UPR may reduce the unfolded protein load through several prosurvival mechanisms, including the expansion of the ER membrane and the selective synthesis of key components of the protein folding and quality control machinery (26). To address how cancer cells respond and adapt to a protein synthesis burden in vivo and downstream of specific oncogenic lesions, we tested whether a specific molecular signature of the UPR may be activated in Ptenfl/fl-versus Ptenfl/fl;MycTg-derived PCa.

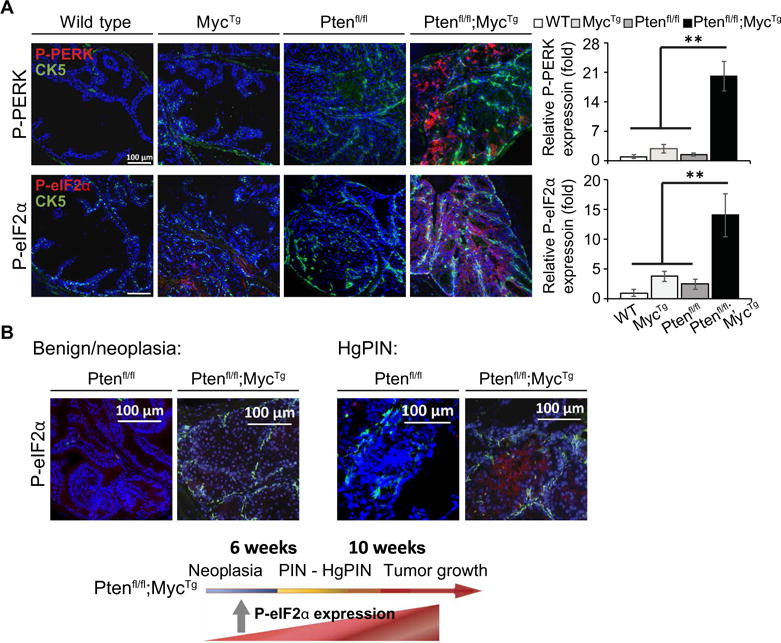

We performed quantitative immunofluorescence (IF) staining for cleaved ATF6, P-IRE1, and P-PERK during tumor development to test whether the UPR was activated during PCa progression. Visualizing UPR expression within prostatic tissue at 10 weeks of age allowed us to directly gauge the activity of each arm during neoplasia. Whereas the ATF6 and IRE1 branches of the UPR were relatively equally activated in Ptenfl/fl and Ptenfl/fl;MycTg tissue (fig. S2A), PERK phosphorylation was selectively increased by over 15-fold within Ptenfl/fl;MycTg tissue compared to its near absence in Ptenfl/fl cells (Fig. 2A). Thus, PERK activation is a distinct response that may promote tumorigenesis in aggressive PCa driven by the cooperation of two oncogenic lesions. To confirm the selective activation of PERK signaling in Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice, we evaluated the downstream signaling to eIF2α. P-eIF2α was also markedly increased in Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice and strongest within areas of PIN but remained absent within Ptenfl/fl tissues (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S2B). The expression of the ER-specific molecular chaperone BiP was not changed and was also high in normal prostatic tissues in agreement with the secretory role of these glands (fig. S2C). Collectively, this analysis reveals two independent, yet linked mechanisms: (i) activation of each UPR pathway in PCa in vivo and (ii) activation of a P-eIF2α–dependent response selectively in Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice, which display more aggressive PCa progression and reduced survival.

Fig. 2. The cooperation of MYC and loss of PTEN selectively activates the adaptive PERK–P-eIF2α arm of the UPR.

(A) Left: Representative IF images of P-PERK/cytokeratin 5 (CK5) or P-eIF2α/CK5 co-staining with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) used to visualize the nuclei within anterior prostate tissue from 10-week-old mice; scale bars, 100 μm. P-PERK or P-eIF2α expression quantified relative to DAPI (n = 3 mice per arm, with four images averaged per mouse, mean ± SEM). (B) Representative IF images of P-eIF2α/CK5 co-staining with DAPI in anterior prostate tissue from 6-week-old mice (scale bars, 100 μm) (left panel) and directly within areas of PIN (right panel). Lower panel depicts a model showing the timeline of PCa development within Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice, highlighting when P-eIF2α is expressed. **P < 0.01, t test.

Rebalancing protein synthesis through P-eIF2α is required for aggressive PCa progression

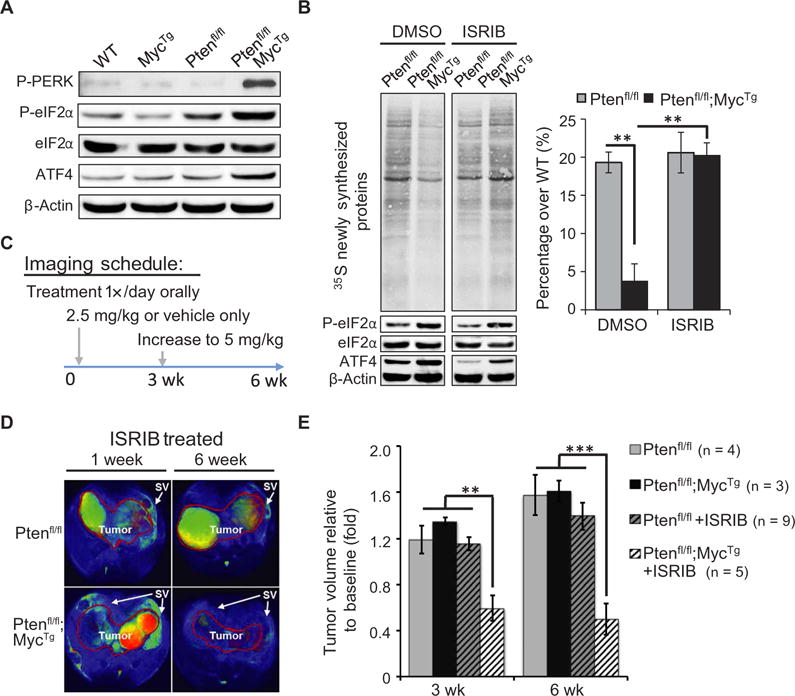

A general UPR response may promote adaptation to proteotoxic and ER stress, whereas the activation of P-eIF2α could place a direct brake on the overwhelming burden of protein synthesis that occurs during more aggressive tumorigenesis. To test this hypothesis, we used our organoid cultures, which recapitulate the in vivo phenotype. The Ptenfl/fl;MycTg cultures show increased activation of P-PERK, P-eIF2α, and expression of ATF4, which is a known target of the PERK–P-eIF2α axis (Fig. 3A). To determine whether the activation of this adaptive response was altering global protein synthesis, we used a small-molecule inhibitor of P-eIF2α activity, ISRIB, a compound that selectively reverses the effects of eIF2α phosphorylation (fig. S3A) (27, 28). Specifically, P-eIF2α binds its dedicated guanine nucleotide exchanging factor (GEF), eIF2B, with enhanced affinity relative to eIF2α. Thus, P-eIF2α sequesters eIF2B from interacting with eIF2α to exchange guanosine diphosphate with guanosine triphosphate, which is an essential step to form the translation preinitiation complex. ISRIB increases eIF2B GEF activity by stabilizing it into a decamer holoenzyme to enhance the binding of the eIF2 factor, thereby restoring protein synthesis regardless of eIF2α phosphorylation (29). In Ptenfl/fl organoid cultures, protein synthesis was not altered by ISRIB treatment, despite the drug inhibiting P-eIF2α activity, as confirmed by a decrease in ATF4 expression (Fig. 3B). Conversely, we observed a marked increase of newly synthesized proteins in Ptenfl/fl;MycTg cells, which show increased P-eIF2α signaling (Fig. 3B). Together, these experiments indicate that P-eIF2α creates an adaptive response to relieve the burden of increased protein synthesis within Ptenfl/fl;MycTg oncogenic cells.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of P-eIF2a activity rebalances protein synthesis and prevents PCa progression.

(A) Representative Western blot highlighting PERK signaling in organoid cultures. (B) Left: Total newly synthesized proteins measured by 35S methionine/cysteine incorporation and Western blot showing P-eIF2α and ATF4 in organoids treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or ISRIB (500 nM) for 6 hours. Right: Quantification of radioactive pulse relative to loading, depicted as percent over WT (n = 3, mean ± SEM). (C) Schematic of preclinical trial for escalating dosage and MRI schedule over 6 weeks. (D) Representative scans of two ISRIB-treated mice after 1 and 6 weeks of treatment for comparison. Tumor is outlined in red, and arrows highlight the seminal vesicles (SV) surrounding the tumor. (E) Quantification of tumor size as fold change relative to baseline volume at 3- and 6-week time points (mean ± SEM). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t test.

In addition to PERK, other kinases can phosphorylate the eIF2α subunit upon distinct stress signals: GCN2 (amino acid deprivation), PKR (viral infection), and HRI (heme deprivation) (30). To assess whether the selective adaptive response observed during aggressive PCa development of Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice was specific to the PERK–P-eIF2α axis, we undertook a genetic approach, using Perkfl/fl mice to evaluate the loss of PERK in the prostate gland (fig. S3B) (31). Ptenfl/fl;MycTg;Perkfl/fl mice showed markedly reduced prostate growth compared to Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice, with weights similar to Ptenfl/fl and Ptenfl/fl; Perkfl/fl mice at 10 weeks of age (fig. S3C). The reduction in prostate size corresponded to a decrease in cancer progression and in cell proliferation (fig. S3, D and E). To determine the consequence of PERK loss for P-eIF2α signaling in PCa development, we monitored P-eIF2α expression by IF stain ing. The activation of P-eIF2α was reduced by 70% in Ptenfl/fl; MycTg;Perkfl/fl tissue compared to Ptenfl/fl;MycTg (fig. S3F). These data strongly suggest that the P-eIF2α– dependent adaptive stress response is driven to a large extent by PERK signaling.

Our studies demonstrated that P-eIF2α is directly activated in the early stage of Ptenfl/fl;MycTg tumorigenesis, being visible in benign tissue and increasing in HgPIN, which may reflect a distinct point of vulnerability for aggressive PCa (Fig. 2). To evaluate the necessity of P-eIF2α for promoting tumor growth or maintenance in vivo, we conducted a preclinical trial. Mice with developed tumors were imaged by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to confirm a measurable baseline of prostate volume per mouse and then grouped into cohorts for either vehicle or ISRIB treatment daily over the course of 6 weeks (Fig. 3C). Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice showed tumor regression within 3 weeks of ISRIB treatment, with no signs of toxicity, whereas all Ptenfl/fl mice showed continued tumor growth (Fig. 3, D and E, fig. S4A, and table S1). By 6 weeks, Ptenfl/fl mice showed an approximate 40% increase in growth over individual baseline measurements, whereas ISRIB-treated Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice demonstrated no progression in tumor size. In addition, we evaluated the immune cell infiltration, marked by the pan-leukocyte antibody CD45 after 3 weeks of ISRIB treatment and observed no significant changes regardless of prostate tumor genotype and treatment (fig. S4B). Further analysis of immune cell populations did not demonstrate substantial differences in total T cell or myeloid populations, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils (fig. S4, C and D). Of the intertumoral immune cells examined, less than 5% were either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, as expected for the Ptenfl/fl murine prostate model (32). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that ISRIB may be remodeling tumor immunity during initial treatment, this was not evident after 3 weeks of treatment. Together, these studies reveal that P-eIF2α signaling is functionally relevant in aggressive PCa and that this adaptive response is therapeutically targetable in vivo using the small-molecule inhibitor ISRIB.

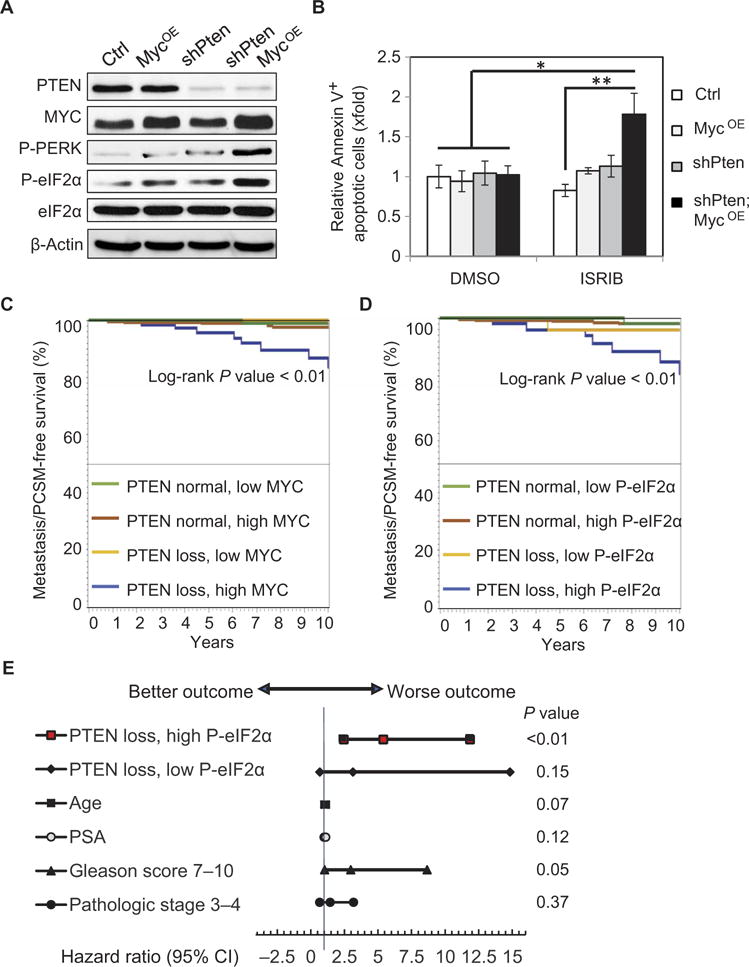

To extend our observations directly to human disease, we created human cell lines to mimic our genetic mouse models. Human RWPE-1 epithelial cells were created to stably knock down PTEN (shPTEN) with or without MYC overexpression (MYCOE, Fig. 4A). The combination of PTEN loss with increased MYC expression activated PERK signaling and P-eIF2α, showing that the adaptive response that we had observed in mice is also triggered in human prostate cells. To understand the requirement for this stress response checkpoint in human cells, we treated each cell line with ISRIB and observed a marked increase in apoptosis, independent of alterations in proliferation, specifically in shPTEN;MYCOE cells relative to control samples (Fig. 4B and fig. S5A).

Fig. 4. High P-eIF2α expression in human prostate tumors with loss of PTEN function is associated with increased risk of metastasis or death after surgery.

(A) Representative Western blot showing PTEN, MYC, P-PERK, P-eIF2α, and total eIF2α expression with β-actin loading control (Ctrl) in human prostatic RWPE-1 cell lines. (B) Quantification of annexin V–positive cells analyzed by flow cytometry relative to control cells after treatment with DMSO or 500 nM ISRIB for 9 hours (n = 3, mean ± SEM) *P < 0.05, t test. (C) Kaplan-Meier analysis of clinical progression–free survival [progression defined as visceral or bone metastasis or PCSM] for patients with normal PTEN expression versus PTEN loss and relative MYC expression identified by IF from the TMA. (D) Kaplan-Meier analysis of MET/PCSM for patients with normal PTEN expression versus PTEN loss grouped by eIF2α phosphorylation. (E) Cox proportional hazards regression results are shown in a Forest plot of hazard ratios and 95% CI for factors associated with risk of clinical progression after surgery. Independent factors are tumor with PTEN loss/low P-eIF2α or PTEN loss/high P-eIF2α versus a reference group with normal PTEN expression; age in years; PSA in nanograms per milliliter; Gleason score > 7 versus 6; and pathological stage T3-T4 versus T2 at the time of prostatectomy.

High P-eIF2α expression with loss of PTEN is associated with an increased risk of metastasis after surgery

To further examine the clinical relevance of high P-eIF2α downstream of PTEN loss, we built a human tissue microarray (TMA) consisting of 424 tumors and analyzed the expression of PTEN, c-MYC, and P-eIF2α. On the basis of our GEMMs, we predicted that the combination of PTEN loss and P-eIF2α would associate with advanced PCa. We selected an array of patients with PCa ranging from low to high risk, who received surgery as a curative treatment with a median of 10 years of follow-up to accurately evaluate the incidence of clinical progression, a composite outcome representing visceral or bone metastasis or PCa-specific mortality (MET/PCSM) (Table 1). We used quantitative IF of P-eIF2α, c-MYC, and PTEN normalized to adjacent benign tissue (fig. S6, A and B) and then evaluated associated risk for MET/PCSM. After controlling for age, prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason score, and pathological staging, the analysis showed that patients with PTEN loss/high MYC expression were more likely to experience metastatic progression than patients with PTEN loss or high MYC alone (Fig. 4C).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients included in the TMA.

Baseline characteristics of the TMA cohort consisting of 424 tumor samples, where 58 years is the average age at diagnosis. More than 50% of the cohort had pathological Gleason grade 7 or higher, and 75% had organ-confined disease (pathological stage T2). Median follow-up was 10 years.

| Patient characteristics of TMA | Value | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | Native American | 1 | 0 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 13 | 3 | |

| African-American | 14 | 3 | |

| Caucasian | 359 | 85 | |

| Mixed | 25 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 12 | 3 | |

| Biopsy Gleason grade | 3 + 3 | 263 | 64 |

| 3 + 4 | 95 | 23 | |

| 4 + 3 | 25 | 6 | |

| 8 − 10 | 29 | 7 | |

| Missing | 12 | — | |

| Clinical T stage | T2 | 296 | 98 |

| T3 | 5 | 2 | |

| T4 | 2 | 1 | |

| Missing | 121 | — | |

| Pathologic Gleason grade | 3 + 3 | 184 | 43 |

| 3 + 4 | 173 | 41 | |

| 4 + 3 | 45 | 11 | |

| 8 − 10 | 22 | 5 | |

| Pathologic T stage | T2 | 313 | 75 |

| T3 | 102 | 24 | |

| T4 | 5 | 1 | |

| Missing | 4 | — | |

| Pathologic N stage | NX | 200 | 48 |

| N0 | 208 | 50 | |

| N1 | 7 | 2 | |

| Missing | 9 | — | |

| Surgical margins | No | 354 | 83 |

| Yes | 70 | 17 | |

| Adverse path (Gleason Grade ≥ 4 + 3 or pT3a/pN1) | No | 291 | 69 |

| Yes | 133 | 31 |

Our data from the GEMMs and human prostatic cell lines suggested that P-eIF2α is a targetable adaptive response downstream of PTEN loss and MYC hyperactivation. Hence, we next examined the associated risk of progression in patients with PTEN loss and high P-eIF2α at the time of surgery. The rate of MET/PCSM-free survival was significantly lower in patients with high P-eIF2α and PTEN loss compared to PTEN loss alone (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4D). Only 4% of patients with PTEN loss and low P-eIF2α succumbed to metastasis or death, whereas 19% of patients with PTEN loss and high P-eIF2α showed MET/PCSM by 10 years after surgical intervention with the intention to cure the disease. Furthermore, patients with high P-eIF2α and PTEN loss had a higher risk of MET/PCSM compared to patients with no PTEN loss, with a hazard ratio of 5.40 [95% confidence interval (CI), 2.46 to 11.86; P < 0.01], whereas other variables that may affect the risk were not significantly different (Fig. 4E). MYC overexpression with either low or high P-eIF2α did not associate with increased risk of MET/PCSM (fig. S6C), supporting our findings that MYC alone does not drive PCa. Notably, high P-eIF2α expression played a role equivalent to the MYC oncogene in combination with loss of PTEN at predicting metastatic progression (Fig. 4, C and D), yet unlike MYC, P-eIF2α may be a druggable target. Together, the combination of P-eIF2α and PTEN loss may serve as a predictor for cancer progression after curative treatment, which is independent of the traditional risk assessment system using PSA, cancer grade, and cancer stage.

We next evaluated the discriminatory properties of high P-eIF2α and PTEN loss as a prognostic marker independent from the most commonly used risk assessment score in the clinic, CAPRA-S (Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment after Surgery) (33). We used the c-index (concordance index) to evaluate the ability of the protein signature of high P-eIF2α with loss of PTEN to discriminate between individual patients who did or did not succumb to metastasis or death after surgery. Currently, clinicians depend on genomic risk to individualize treatment decisions using three available gene expression tests: Prolaris, Decipher, and OncotypeDx (34). The Prolaris test relies on the average expression of 31 cell cycle progression (CCP) genes and was validated using the same cohort of patients used in the TMA (35). Within the same patients, the Prolaris-CCP panel has a combined c-index of 0.77 (CAPRA-S + CCP) (35), whereas high P-eIF2α and PTEN loss has a c-index of 0.80 (fig. S6D). These findings show that concurrent high P-eIF2α and PTEN loss serves as an independent predictor with improved prognostic accuracy over standard clinicopathologic testing for discriminating which individuals may experience metastatic progression.

P-eIF2α is a targetable adaptive response in aggressive human PCa

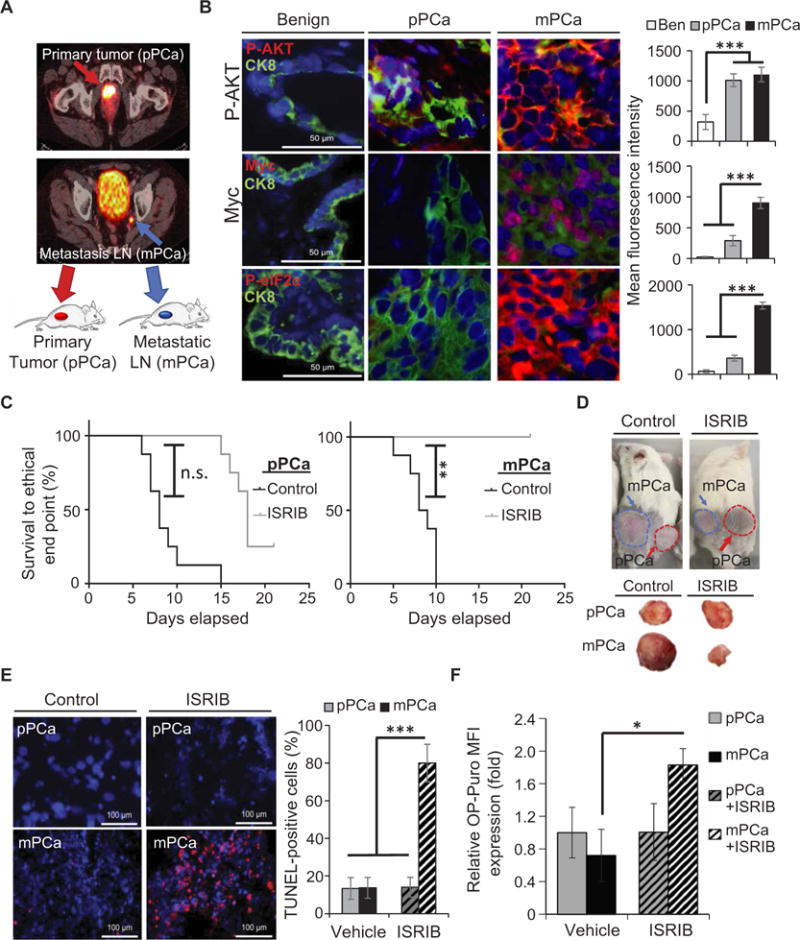

We next sought to functionally evaluate whether we could target the UPR pathway, specifically through P-eIF2α, in advanced human PCa. Although it is historically difficult to generate human prostate patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models (36), we were successful in generating models with similar characteristics to the Ptenfl/fl;MycTg mice to assess the effects of ISRIB on cancer growth and mortality. In particular, we generated two PDX models: one derived from a primary tumor, herein referred to as pPCa, and one derived from a lymph node metastasis in the left internal iliac chain from the same patient, herein referred to as mPCa (Fig. 5A). The pPCa-PDX tumor had significantly lower MYC expression than the mPCa-PDX tumor (P < 0.01), but both showed loss of PTEN with increased P-AKT expression (Fig. 5B and fig. S7A). We also observed a significant increase in P-eIF2α only in the mPCa (P < 0.01; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Inhibition of P-eIF2α axis results in tumor regression and prolongs survival in a humanized model of metastatic PCa.

(A) Schematic highlighting origin of PDX tumors from primary (pPCa) or lymph node metastasis (mPCa). Tumors from selected patients with high-risk features, based on Gleason score and clinical stage or with lymph node metastases determined by 68Ga–PSMA-11 positron emission tomography (PET) scans, were used to generate PDXs. Primary and metastatic tumors were confirmed from tissue collected at the time of surgery and immediately implanted into immunodeficient NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice. (B) Representative IF images of MYC/CK8 (epithelial cell marker), P-AKT/CK8, or P-eIF2α/CK8, co-staining with DAPI from benign (Ben) tissue adjacent to pPCa or mPCa tumors; scale bars, 50 μm. Right: Quantification of protein expression as relative mean IF intensity normalized to adjacent stromal tissue. (C) Kaplan-Meier tumor survival curves for mice bearing pPCa or mPCa tumors treated with ISRIB (10 mg/kg) or vehicle (n = 8, per cohort; **P = 0.01, log-rank test). The survival curves represent mice euthanized when tumors reached an end point of 2 cm or when the mice showed clear signs of morbidity. (D) Representative tumor sizes after 10 days of treatment. (E) Representative TUNEL staining and quantification of PDX tumors treated with vehicle or ISRIB (10 mg/kg); scale bars, 100 μm (n = 3, ***P < 0.001, t test). (F) Quantification of newly synthesized proteins in vivo, assessed by incorporation of OP-Puro within PDX treated with ISRIB (10 mg/kg) or vehicle (n = 3 to 4 per arm, mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, t test). n.s., not significant. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

To test the therapeutic efficacy of ISRIB in human PCa, we performed a preclinical trial on the stably passaged PDX model. Targeting P-eIF2α pharmacologically significantly prolonged survival in mice bearing the metastatic tumor with high P-eIF2α (P < 0.01; Fig. 5C), whereas the effectiveness of ISRIB treatment was short-lived in pPCa tumor. Consistent with our GEM model, the mPCa-PDX model, with high expression of P-eIF2α, displayed significant tumor regression and cell death (P < 0.01), as demonstrated by increased terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining and cleaved caspase 3 expression after only 9 days of ISRIB treatment (Fig. 5, D and E, and fig. S7B). Conversely, the pPCa-PDX model, with low P-eIF2α, did not show regression but stabilized with eventual tumor regrowth and no significant cell death (Fig. 5, D and E, and fig. S7B). These findings demonstrate that attenuating P-eIF2α activity with ISRIB elicits a potent antitumor effect in a humanized model of advanced PCa.

We next determined whether a metastatic PCa tumor, harboring high MYC and loss of PTEN activity in a complex genetic background of human PCa, relies on eIF2α phosphorylation as an adaptive response to restrain global protein synthesis. Therefore, we assessed newly synthesized proteins in vivo by measuring the incorporation of O-propargyl–puromycin (OP-Puro) within the primary and metastatic tumor–derived PDXs, which have low or high P-eIF2α, respectively. Upon ISRIB treatment, we observed a marked increase in global protein synthesis specifically in the mPCa PDX, but no change in pPCa tumors where P-eIF2α expression was not up-regulated (Fig. 5F). To further assess the functional relevance of P-eIF2α signaling, we decreased ATF4 expression in vivo using intratumor knockdown by small interfering RNA (siRNA). Within the area of intratumor ATF4 loss, we observed apoptosis and decreased proliferation assessed by TUNEL and Ki67 staining of mPCa PDX (fig. S7C). This demonstrated that inhibition of the PERK-eIF2α axis by a genetic or pharmacological approach effectively results in cell death of aggressive PCa in vivo.

Targeting P-eIF2α activity reduced metastasis and prolonged survival in a PDX model of metastatic castration-resistant PCa

In hormone-sensitive metastatic PCa, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) remains the mainstay treatment; however, these tumors inevitably develop resistance to ADT and progress into the lethal form of metastatic castration-resistant PCa (mCRPC) (37). Characterization of the hormone-sensitive metastatic disease has not been predictive of outcomes in the clinical setting of lethal mCRPC (38, 39). To directly study the contribution of P-eIF2α to metastasis, we generated an additional PDX (herein mCRPC PDX) derived from a patient with mCRPC despite prolonged treatment with complete androgen blockage using leuprolide (ADT) and antiandrogen therapy (enzalutamide) (37). Three weeks after implantation of the mCRPC tumor under the mouse renal capsule, we observed tumor dissemination to the liver, distant kidney, lymph nodes, and spleen (fig. S8, A and B). The mCRPC PDX line continued to exhibit metastatic dissemination in the mouse host after multiple passages and retained histological and molecular characteristics of the original tumor. The distant metastatic lesions exhibited loss of PTEN, high MYC, and high P-eIF2α expression (Fig. 6A and fig. S8C).

Fig. 6. ISRIB treatment decreases metastatic progression in an advanced castration-resistant PCa PDX model.

(A) Representative H&E staining and IF of P-eIF2α, PTEN, and MYC expression at the primary site of implantation (mCRPC tumor), left kidney, and distant metastatic lesions in the liver; scale bars, 200 μm (top left); 100 μm (bottom left); and 50 μm for IF images. (B) Schematic of preclinical trial for mCRPC tumor growth and PET/CT schedule. Representative 68Ga–PSMA-11 PET/CT scans on day 0 (time of treatment) and on day 7 are shown for the control versus ISRIB-treated cohorts. Uptake of the PSMA-targeted radiotracer agent is observed in the liver, lymph node, and at the site of primary tumor implantation in the left kidney capsule. Physiologic uptake of the PSMA-targeted radiotracer is also seen in the contralateral kidney and bladder because it is excreted in the urinary tract. Histologic confirmation of liver metastasis is shown by H&E staining at the time of euthanasia with dashed outlines around metastatic lesions. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for mice bearing mCRPC tumors treated once per day with ISRIB (10 mg/kg) or vehicle (n = 3, per cohort); *P = 0.02, log-rank test. The survival curves represent mice euthanized when PSMA 68Ga PET/CT showed progression from one distant metastatic lesion to two or more sites or when the mice showed signs of becoming moribund. (D) Quantification of visible metastatic lesions on the left medial lobe of the liver at the time of euthanasia in the cohorts (n = 3 per cohort); ***P = 0.001.

To examine the role of P-eIF2α from the early stages of metastatic growth to late stages of dissemination, we used a prostate-specific membrane antigen [68Ga–PSMA-11 PET/computed tomography (CT)] scan to trace the progression of very small metastases from early to late stages of dissemination, which were not visible by conventional imaging modalities such as 18F-DG PET/CT (fig. S8D) (40). Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is highly expressed on the surface of PCa cells and allows sensitive staging to evaluate therapy response in the clinical setting (40). We subjected mice bearing liver or distal metastasis (confirmed by PSMA PET) to either vehicle or ISRIB treatment (Fig. 6, B and C). Inhibition of P-eIF2α with ISRIB significantly prolonged survival in mCRPC PDX mice bearing distal metastatic lesions (P = 0.01; Fig. 6C). In contrast, mice with metastasis died within 10 days on vehicle treatment. By direct imaging with PSMA PET/CT, we observed substantial metastatic regression at distal sites in mice treated with ISRIB (Fig. 6B). In addition, we confirmed a difference in metastatic progression in the liver by pathohistological analysis at time of euthanasia (Fig. 6D). Therefore, two independent PDX models of metastatic disease, one derived from a patient with early nodal metastasis (hormone-sensitive) and the second from a patient with castration-resistant PCa, demonstrated that blocking the activation of the adaptive brake on global protein synthesis via the P-eIF2α axis resulted in profound tumor regression and inhibition of metastatic dissemination.

DISCUSSION

The biological processes that allow cancer cells to balance working at capacity for tumor progression while dealing with stress phenotypes induced by the overload of cellular processes underlying rapid cell growth and division (bioenergetic processes including DNA and protein synthesis) are still poorly understood. Our data reveal a cell-autonomous mechanism wherein the activity of two major oncogenic lesions, loss of PTEN and MYC overexpression, which independently enhance protein synthesis, paradoxically, decrease global protein production when these oncogenic events coexist. This high lights the requirement for an adaptive protein homeostasis response to sustain aggressive tumor development.

Proteostasis is essential for normal cell health and viability, and as such is ensured by the coordinated control of protein synthesis, folding, and degradation (41). Although the UPR enables proteostasis to be restored during unfavorable conditions, we found that PCa cells have usurped a specific branch of this pathway for tumor growth and maintenance. The UPR consists of three main branches, yet only the PERK–P-eIF2α axis is selectively triggered in this pathophysiological state to ensure continued survival of cancer cells. The mechanisms triggering the selective activation of the PERK–P-eIF2α axis in PCa may be through increased protein misfolding itself, as a consequence of augmented protein synthesis at the ER, or through additional cues acting independently from the UPR (42). Nonetheless, the adaptive response involving P-eIF2α signaling provides a barrier to uncontrolled increases in protein synthesis and creates a permissive environment for continued tumor growth. It is also possible that P-eIF2α may affect the translation of select transcripts that are essential for aggressive oncogenesis (43–45).

It is tempting to speculate that cancer cells may have usurped mechanisms normally operating in certain cell types, whereby activation of specific branches of the UPR enables cellular differentiation or maintenance of stem cell features (46). For example, B lymphocytes normally induce the UPR during their differentiation into plasma cells to preemptively prepare for increased antibody production and secretion (47). Moreover, skeletal muscle stem cells maintain enhanced P-eIF2α to promote a quiescent state required for their self-renewal capacity, which requires diminished protein synthesis (48). Such control of the UPR seen in specialized cell types may have been hijacked by specific oncogenic lesions to promote cancer survival and metastatic behavior. Our data show the functional relevance of targeting this adaptive brake with ISRIB treatment to trigger cytotoxicity during aggressive lethal stages of advanced and castration-resistant PCa, for which at present there is no cure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study was designed to evaluate how two oncogenic lesions, which augment protein synthesis, cooperate in aggressive PCa and prevent proteotoxic stress to support tumor growth and survival. This objective was addressed by (i) creating mouse models, cell lines, and PDX models that depict the loss of PTEN with or without the overexpression of MYC, (ii) evaluating PCa development downstream of these oncogenes, (iii) observing global changes in newly synthesized proteins, followed by (iv) identifying the adaptive response responsible for our observations. Using a genetic and pharmacological approach in both GEM and PDX models, we inhibited the identified adaptive response to observe the effects on tumor development and growth. TMA analysis was also conducted to investigate the clinical relevance of our findings in association with advanced PCa.

For all experiments, our sample sizes were determined on the basis of experience and published literature, which historically show that these in vivo models are penetrant and consistent for tumor development. We used the maximum number of mice available for a given experiment based on the following criteria: the number of GEMMs available in the age range of tumor development and tumor size availability for implantation in PDXs. All mice were randomly assigned to each treatment group for all preclinical trials. Blinded observers visually inspected mice for obvious signs of tumor growth or morbidity including weight loss, hunched posture, or lethargy. MRI tumor recognition, IF imaging, and data collection by flow cytometry were done by researchers blinded to the sample identification after analysis. The number of experimental replicates is specified within each figure legend and elaborated for specific experiments within Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, GraphPad Prism, or SAS (Statistical Analysis System) 9.4 for Windows, with additional description in Supplementary Materials and Methods. Raw values were depicted when possible or normalized to internal controls from at least three independent experiments, shown as quantitative values expressed as means ± SD or SEM, as indicated. Data were analyzed applying unpaired Student’s t test to compare quantitative data between two independent samples, unless otherwise specified. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for survival analysis. P < 0.05 were considered significant and denoted by *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. MycTg and PTEN loss cooperate for aggressive PCa development in mice.

Fig. S2. The UPR is activated in murine PCa.

Fig. S3. PERK loss blocks PCa progression and decreases P-eIF2α expression.

Fig. S4. Loss of P-eIF2α activity by ISRIB shows no toxicity and does not substantially alter infiltrating immune cells.

Fig. S5. Inhibition of P-eIF2α activity by ISRIB does not affect human prostatic cell lines’ growth.

Fig. S6. PCa tissue from TMA shows specificity of protein expression in benign and tumor cells.

Fig. S7. Treatment with ISRIB or ATF4 siRNA results in increased apoptosis within metastatic tumor.

Fig. S8. A PDX was generated to recapitulate mCRPC.

Table S1. MRI tumor volumes during treatment in GEMMs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Mouse Pathology, Preclinical Therapeutics, and Biomedical Imaging Core facilities at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) for their assistance in our study. We are grateful to J. Simko at UCSF for building the TMA, for providing them for our use, and for assistance in selecting human tumor tissue used in construction of the pPCa and mPCa PDX models. In addition, we thank M. Barna at Stanford University for the helpful comments provided.

Funding: H.G.N. is supported by the U.S. Department of Defense (W81XWH-15-1-0460), AUA-SUO-Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award (16YOUN14), and AUA Urology Care Foundation Rising Star in Research Award (A130596). C.S.C. is funded by the American Cancer Society (PF-14-212-01-RMC) and the AACR-Bayer Prostate Cancer Research Fellowship (17-40-44-CONN). C.M.F. is funded by the Campini Foundation, The Leukemia and Lymphoma Foundation Career Development Grant, and UCSF Department of Pediatrics K12 (5K12HDO72222-05). A.C.H. was supported by NIH (1K08CA175154-01) and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists. M.J.E. and D.R. are supported by the American Cancer Society (130635-RSG-17-005-01-CCE). C.K. and D.R. are supported by NIH (P01-CA1659970). P.W. is supported by Calico Life Sciences LLC, the Weill Foundation, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. D.R. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar, and this research was funded by NIH grants (R01-CA140456 and R01-CA154916). C.K. and D.R. are supported by NIH (P01-CA165997), and C.K. by NIH (2R01-CA094214). F.T. was supported by NIH (F31CA183569).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/10/439/eaar2036/DC1 Materials and Methods

Author contributions: H.G.N., C.S.C., and D.R. provided oversight of the project. H.G.N., P.R.C., and L.X. primarily collected and analyzed data from PDX models and TMA. C.S.C. and Y.K. primarily collected and analyzed data from GEMMs and cell lines used. C.M.F. collected flow data for GEMMs and PDX models. J.E.C. discussed and performed statistical analysis for the TMA supplied under the supervision of P.R.C. The MycTg mouse model was created by J.T.C., and initial GEMM colonies were started by A.C.H. C.T. and M.J.E. assisted for in vivo imaging experiments. C.P.E. and J.C.Y. created and initially characterized the mCRPC PDX model. B.H. aided in preclinical studies for mouse models. F.T. and C.K. provided materials and discussion for studying PERK signaling. P.W. provided materials and discussion for studying P-eIF2α with ISRIB. C.S.C. and D.R. prepared the manuscript with edits from H.G.N. and Y.K. Additional authors provided edits for their specific contributions.

Competing interests: P.W. is an inventor on patent 9708247 held by the Regents of the University of California that describes ISRIB and its analogs. Rights to the invention have been licensed by UCSF to Calico. D.R., H.G.N., P.R.C., C.S.C., and L.X. are inventors on patent application pending: Case no, SF2018-128 held the Regents of the University of California that covers development of a novel two protein biomarker analysis for PCa and a clinical version of ISRIB that can be used to target tumor and metastatic progression in patients. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: Requests for materials should be addressed to C.S.C. or D.R. and will be provided with the potential of a material transfer agreement. The mCRPC PDXs are available from C.P.E. under a material agreement with UC Davis.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo J, Solimini NL, Elledge SJ. Principles of cancer therapy: Oncogene and non-oncogene addiction. Cell. 2009;136:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruggero D. Revisiting the nucleolus: From marker to dynamic integrator of cancer signaling. Sci Signal. 2012;5:e38. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the endoplasmic reticulum protein-folding environment on cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:581–597. doi: 10.1038/nrc3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hetz C, Chevet E, Oakes SA. Proteostasis control by the unfolded protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:829–838. doi: 10.1038/ncb3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koumenis C, Naczki C, Koritzinsky M, Rastani S, Diehl A, Nahum S, Koromilas A, Wouters BG. Regulation of protein synthesis by hypoxia via activation of the endoplasmic reticulum kinase PERK and phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7405–7416. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7405-7416.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fels DR, Koumenis C. The PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 module of the UPR in hypoxia resistance and tumor growth. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:723–728. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh AC, Liu Y, Edlind MP, Ingolia NT, Janes MR, Sher A, Shi EY, Stumpf CR, Christensen C, Bonham MJ, Wang S, Ren P, Martin M, Jessen K, Feldman ME, Weissman JS, Shokat KM, Rommel C, Ruggero D. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature. 2012;485:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsieh AC, Nguyen HG, Wen L, Edlind MP, Carroll PR, Kim W, Ruggero D. Cell type–specific abundance of 4EBP1 primes prostate cancer sensitivity or resistance to PI3K pathway inhibitors. Sci Signal. 2015;8:ra116. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aad5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh CM, Gurel B, Sutcliffe S, Aryee MJ, Schultz D, Iwata T, Uemura M, Zeller KI, Anele U, Zheng Q, Hicks JL, Nelson WG, Dang CV, Yegnasubramanian S, De Marzo AM. Alterations in nucleolar structure and gene expression programs in prostatic neoplasia are driven by the MYC oncogene. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1824–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar A, Coleman I, Morrissey C, Zhang X, True LD, Gulati R, Etzioni R, Bolouri H, Montgomery B, White T, Lucas JM, Brown LG, Dumpit RF, DeSarkar N, Higano C, Yu EY, Coleman R, Schultz N, Fang M, Lange PH, Shendure J, Vessella RL, Nelson PS. Substantial interindividual and limited intraindividual genomic diversity among tumors from men with metastatic prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:369–378. doi: 10.1038/nm.4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltran H, Prandi D, Mosquera JM, Benelli M, Puca L, Cyrta J, Marotz C, Giannopoulou E, Chakravarthi BVSK, Varambally S, Tomlins SA, Nanus DM, Tagawa ST, Van Allen EM, Elemento O, Sboner A, Garraway LA, Rubin MA, Demichelis F. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:298–305. doi: 10.1038/nm.4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunningham JT, Moreno MV, Lodi A, Ronen SM, Ruggero D. Protein and nucleotide biosynthesis are coupled by a single rate-limiting enzyme, PRPS2, to drive cancer. Cell. 2014;157:1088–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barna M, Pusic A, Zollo O, Costa M, Kondrashov N, Rego E, Rao PH, Ruggero D. Suppression of Myc oncogenic activity by ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency. Nature. 2008;456:971–975. doi: 10.1038/nature07449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pourdehnad M, Truitt ML, Siddiqi IN, Ducker GS, Shokat KM, Ruggero D. Myc and mTOR converge on a common node in protein synthesis control that confers synthetic lethality in Myc-driven cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:11988–11993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310230110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruggero D. The role of Myc-induced protein synthesis in cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8839–8843. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesche R, Groszer M, Gao J, Wang Y, Messing A, Sun H, Liu X, Wu H. Cre/loxP-mediated inactivation of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene. Genesis. 2002;32:148–149. doi: 10.1002/gene.10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;163:1011–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Eltoum IEA, Roh M, Wang J, Abdulkadir SA. Interactions between cells with distinct mutations in c-MYC and Pten in prostate cancer. PLOS Genet. 2009;5:e1000542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellwood-Yen K, Graeber TG, Wongvipat J, Iruela-Arispe ML, Zhang J, Matusik R, Thomas GV, Sawyers CL. Myc-driven murine prostate cancer shares molecular features with human prostate tumors. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:223–238. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drost J, Karthaus WR, Gao D, Driehuis E, Sawyers CL, Chen Y, Clevers H. Organoid culture systems for prostate epithelial and cancer tissue. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:347–358. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karthaus WR, Iaquinta PJ, Drost J, Gracanin A, van Boxtel R, Wongvipat J, Dowling CM, Gao D, Begthel H, Sachs N, Vries RGJ, Cuppen E, Chen Y, Sawyers CL, Clevers HC. Identification of multipotent luminal progenitor cells in human prostate organoid cultures. Cell. 2014;159:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Felsher DW. MYC as a regulator of ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:301–309. doi: 10.1038/nrc2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Truitt ML, Ruggero D. New frontiers in translational control of the cancer genome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:288–304. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: Controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidrauski C, Tsai JC, Kampmann M, Hearn BR, Vedantham P, Jaishankar P, Sokabe M, Mendez AS, Newton BW, Tang EL, Verschueren E, Johnson JR, Krogan NJ, Fraser CS, Weissman JS, Renslo AR, Walter P. Pharmacological dimerization and activation of the exchange factor eIF2B antagonizes the integrated stress response. eLife. 2015;4:e07314. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sidrauski C, McGeachy AM, Ingolia NT, Walter P. The small molecule ISRIB reverses the effects of eIF2α phosphorylation on translation and stress granule assembly. eLife. 2015;4:e05033. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai JC, Miller-Vedam LE, Anand AA, Jaishankar P, Nguyen HC, Renslo AR, Frost A, Walter P. Structure of the nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B reveals mechanism of memory-enhancing molecule. Science. 2018;359:eaaq0939. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pakos-Zebrucka K, Koryga I, Mnich K, Ljujic M, Samali A, Gorman AM. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1374–1395. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang P, McGrath B, Li S, Frank A, Zambito F, Reinert J, Gannon M, Ma K, McNaughton K, Cavener DR. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3864-3874.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia AJ, Ruscettia M, Arenzanac TL, Trana LM, Bianci-Friasd D, Syberta E, Pricemana SJ, Wu L, Nelsond PS, Smalec ST, Wu H. Pten null prostate epithelium promotes localized myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and immune suppression during tumor initiation and progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:2017–2028. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00090-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooperberg MR, Pasta DJ, Elkin EP, Litwin MS, Latini DM, DuChane J, Carroll PR. The University of California, San Francisco Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score: A straightforward and reliable preoperative predictor of disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173:1938–1942. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158155.33890.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen HG, Welty CJ, Cooperberg MR. Diagnostic associations of gene expression signatures in prostate cancer tissue. Curr Opin Urol. 2015;25:65–70. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooperberg MR, Simko JP, Cowan JE, Reid JE, Djalilvand A, Bhatnagar S, Gutin A, Lanchbury JS, Swanson GP, Stone S, Carroll PR. Validation of a cell-cycle progression gene panel to improve risk stratification in a contemporary prostatectomy cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1428–1434. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin D, Wyatt AW, Xue H, Wang Y, Dong X, Haegert A, Wu R, Brahmbhatt S, Mo F, Jong L, Bell RH, Anderson S, Hurtado-Coll A, Fazli L, Sharma M, Beltran H, Rubin M, Cox M, Gout PW, Morris J, Goldenberg L, Volik SV, Gleave ME, Collins CC, Wang Y. High fidelity patient-derived xenografts for accelerating prostate cancer discovery and drug development. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1272–1283. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2921-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cookson MS, Lowrance WT, Murad MH, Kibel AS. American Urological Association, Castration-resistant prostate cancer: AUA guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015;193:491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gundem G, Van Loo P, Kremeyer B, Alexandrov LB, Tubio JMC, Papaemmanuil E, Brewer DS, Kallio HML, Högnäs G, Annala M, Kivinummi K, Goody V, Latimer C, O’Meara S, Dawson KJ, Isaacs W, Emmert-Buck MR, Nykter M, Foster C, Kote-Jarai Z, Easton D, Whitaker HC, ICGC Prostate UK Group. Neal DE, Cooper CS, Eeles RA, Visakorpi T, Campbell PJ, McDermott U, Wedge DC, Bova GS. The evolutionary history of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature. 2015;520:353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature14347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, Montgomery B, Taplin ME, Pritchard CC, Attard G, Beltran H, Abida WM, Bradley RK, Vinson J, Cao X, Vats P, Kunju LP, Hussain M, Feng FY, Tomlins SA, Cooney KA, Smith DC, Brennan C, Siddiqui J, Mehra R, Chen Y, Rathkopf DE, Morris MJ, Solomon SB, Durack JC, Reuter VE, Gopalan A, Gao J, Loda M, Lis RT, Bowden M, Balk SP, Gaviola G, Sougnez C, Gupta M, Yu EY, Mostaghel EA, Cheng HH, Mulcahy H, True LD, Plymate SR, Dvinge H, Ferraldeschi R, Flohr P, Miranda S, Zafeiriou Z, Tunariu N, Mateo J, Perez-Lopez R, Demichelis F, Robinson BD, Schiffman MA, Nanus DM, Tagawa ST, Sigaras A, Eng KW, Elemento O, Sboner A, Heath EI, Scher HI, Pienta KJ, Kantoff P, de Bono JS, Rubin MA, Nelson PS, Garraway LA, Sawyers CL, Chinnaiyan AM. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouchelouche K, Choyke PL. Advances in prostate-specific membrane antigen PET of prostate cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30:189–196. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karali E, Bellou S, Stellas D, Klinakis A, Murphy C, Fotsis T. VEGF Signals through ATF6 and PERK to promote endothelial cell survival and angiogenesis in the absence of ER stress. Mol Cell. 2014;54:559–572. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holcik M, Sonenberg N. Translational control in stress and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:318–327. doi: 10.1038/nrm1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robichaud N, Sonenberg N. Translational control and the cancer cell response to stress. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;45:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bi M, Naczki C, Koritzinsky M, Fels D, Blais J, Hu N, Harding H, Novoa I, Varia M, Raleigh J, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Bell J, Ron D, Wouters BG, Koumenis C. ER stress-regulated translation increases tolerance to extreme hypoxia and promotes tumor growth. EMBO J. 2005;24:3470–3481. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Todd DJ, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Kowal C, Lee AH, Volpe BT, Diamond B, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Glimcher LH. XBP1 governs late events in plasma cell differentiation and is not required for antigen-specific memory B cell development. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2151–2159. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sendoel A, Dunn JG, Rodriguez EH, Naik S, Gomez NC, Hurwitz B, Levorse J, Dill BD, Schramek D, Molina H, Weissman JS, Fuchs E. Translation from unconventional 5′ start sites drives tumour initiation. Nature. 2017;541:494–499. doi: 10.1038/nature21036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuda T, Cepko CL. Electroporation and RNA interference in the rodent retina in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235688100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyazaki J-i, Takaki S, Araki K, Tashiro F, Tominaga A, Takatsu K, Yamamura K-i. Expression vector system based on the chicken β-actin promoter directs efficient production of interleukin-5. Gene. 1989;79:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Montoya R, Jacks T, Tuveson DA. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic. K-ras Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rees S, Coote J, Stables J, Goodson S, Harris S, Lee MG. Bicistronic vector for the creation of stable mammalian cell lines that predisposes all antibiotic-resistant cells to express recombinant protein. Biotechniques. 1996;20:102–110. doi: 10.2144/96201st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okada A, Lansford R, Weimann JM, Fraser SE, McConnell SK. Imaging cells in the developing nervous system with retrovirus expressing modified green fluorescent protein. Exp Neurol. 1999;156:394–406. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): Explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med. 2012;9:e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. MycTg and PTEN loss cooperate for aggressive PCa development in mice.

Fig. S2. The UPR is activated in murine PCa.

Fig. S3. PERK loss blocks PCa progression and decreases P-eIF2α expression.

Fig. S4. Loss of P-eIF2α activity by ISRIB shows no toxicity and does not substantially alter infiltrating immune cells.

Fig. S5. Inhibition of P-eIF2α activity by ISRIB does not affect human prostatic cell lines’ growth.

Fig. S6. PCa tissue from TMA shows specificity of protein expression in benign and tumor cells.

Fig. S7. Treatment with ISRIB or ATF4 siRNA results in increased apoptosis within metastatic tumor.

Fig. S8. A PDX was generated to recapitulate mCRPC.

Table S1. MRI tumor volumes during treatment in GEMMs.