Abstract

Objectives

To assess agreement between interpretation of magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) for disease extent and disease activity in large-vessel vasculitis (LVV) and determine associations between imaging and clinical assessments.

Methods

Patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA), Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK), and comparators were recruited into a prospective, observational cohort. Imaging and clinical assessments were performed concurrently, blinded to each other. Agreement was assessed by percent agreement, Cohen’s kappa, and McNemar’s test. Multivariable logistic regression identified MRA features associated with PET scan activity.

Results

84 patients (GCA=35; TAK=30; Comparator=19) contributed 133 paired studies. Agreement for disease extent between MRA and PET was 580 out of 966 (60%) arterial territories with Cohen’s kappa=0.22. Of 386 territories with disagreement, MRA demonstrated disease in more territories than PET (304 vs 82, p<0.01). Agreement for disease activity between MRA and PET was 90 studies (68%) with Cohen’s kappa=0.30. In studies with disagreement, MRA demonstrated activity in 23 studies and PET in 20 studies (p=0.76). Edema and wall thickness on MRA were independently associated with PET scan activity. Clinical status was associated with disease activity by PET (p<0.01) but not MRA (p=0.70), yet 35/69 (51%) patients with LVV in clinical remission had active disease by both MRA and PET.

Conclusions

In assessment of LVV, MRA and PET contribute unique and complementary information. MRA better captures disease extent, and PET scan is better suited to assess vascular activity. Clinical and imaging-based assessments often do not correlate over the disease course in LVV.

Keywords: vasculitis, giant cell arteritis, Takayasu’s arteritis, magnetic resonance angiography, positron emission tomography

INTRODUCTION

Vascular imaging is essential to evaluate patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK), the two main forms of large-vessel vasculitis (LVV).1 Temporal artery biopsy is the gold standard to detect cranial forms of GCA, but imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis for the large-vessel variant of this type of vasculitis and for TAK.2 Current imaging modalities available for the assessment of LVV include ultrasonography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), catheter-based angiography, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and 18F-flurodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET). 3–5

There remains uncertainty about which imaging technique to choose to evaluate a patient with suspected or established LVV. The extent to which different imaging modalities provide unique versus redundant information about vascular disease is unclear. MRA and CTA are commonly used to detect and monitor arterial anatomical abnormalities such as stenosis and aneurysm; however, MRA is generally preferred over CTA for serial follow-up imaging to avoid radiation and use of iodinated contrast agents. Furthermore, specific imaging sequences on MRA identify arterial wall abnormalities thought to be reflective of ongoing vascular inflammation, including edema, wall thickness, and contrast enhancement. FDG-PET detects abnormal metabolic activity in the wall of inflamed arteries and may, therefore, be more useful than MR to detect and monitor ongoing vascular inflammation in patients with LVV.3,6

Most studies that have evaluated the utility of MRA or FDG-PET have focused exclusively on imaging at the time of diagnosis, and there is uncertainty about the utility of these imaging modalities to monitor vascular inflammation in patients with established vasculitis. 3,7–9 Prior reports have demonstrated ongoing vascular inflammation on imaging in periods of apparent clinical remission, highlighting a potential discordance between clinical and imaging based assessment in LVV.10,11 To what extent vascular inflammation assessed by MRA compared to PET correlates with clinical assessment over the course of disease in LVV is unknown.

The objectives of this study were to assess agreement between interpretation of MRA and PET for disease extent and disease activity, identify features of MRA associated with PET activity, and determine the correlation between interpretations of MRA and PET and clinical disease assessments in a prospective, longitudinal cohort of patients with LVV who underwent periodic imaging at different points in the disease course.

METHODS

Study population

Patients with large-vessel vasculitis (LVV) were recruited into a prospective, observational cohort at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD, USA. Patients fulfilled the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Classification Criteria for TAK12 or modified 1990 ACR Criteria for GCA13. Patients could be enrolled at the time of diagnosis or later during the disease course.

A comparator group was also studied, consisting mainly of patients with non-inflammatory large-vessel vasculopathies (e.g. fibromuscular dysplasia, traumatic stenosis) and other types of vasculitis (e.g. polyarteritis nodosa). Details of these patients have been reported elsewhere.11 The comparator group was included to determine if there was a difference in the performance characteristics of MRA versus PET in assessing patients with diseases that mimic LVV.

Clinical Assessment

All patients underwent baseline clinical evaluation, MRA, and PET imaging at the NIH Clinical Center. Patients with LVV had follow-up clinical assessments and imaging performed at 6-month intervals, and outside rheumatology records were reviewed between visits. Clinical assessments were performed and recorded by the investigative study team within 24 hours prior to imaging assessment. To enable unbiased comparisons, acute phase reactants and imaging study findings were not incorporated into the definitions of clinical disease activity and remission, an approach that is consistent with clinical definitions of disease activity used in recent randomized controlled trials in LVV13. Active disease was defined as presence at the time of assessment of any clinical disease feature directly attributed to vasculitis (e.g. carotidynia, headache). Fatigue or elevated acute phase reactants alone, were not considered sufficient evidence of active disease. Remission was defined as the absence of any clinical symptoms directly attributable to vasculitis, regardless of acute phase reactants. Clinical disease was recorded as active or remission, prior to conducting imaging studies.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography Protocol and Assessment

All patients underwent MRA of the aorta and primary branches at each study visit (see online Supplementary Methods for sequence details). Two vascular radiologists (AM, JM) interpreted all MRAs included in this study, blinded to clinical data, PET scan assessment, and each other’s assessment. Disease activity on MRA was defined by global interpretation of each study by the readers based upon clinical review of all available sequences. To evaluate disease extent, vascular involvement of 4 segments of the aorta (ascending, arch, descending thoracic, and abdominal) and 11 branch arteries (innominate, carotids, subclavians, axillaries, iliacs, and femorals) was evaluated in a random subset of 72 paired scans, including TAK, GCA, and comparators. Vascular involvement within each territory for the disease extent analyses was defined as the presence of ≥1 of following features: wall thickness, edema, stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm. Territories that were not adequately visualized or were sites of prior surgical correction were excluded from analysis.

FDG-PET Imaging Protocol and Assessment

Whole-body PET studies were performed on the same morning as MRA imaging (see online Supplementary Methods for details). Two nuclear medicine physicians (MA, CC) interpreted all PET scans included in this study. Readers were blinded to clinical data, angiogram assessment, and each other’s assessment. Consensus between the readers was used to determine whether each scan was consistent with active or inactive vasculitis based upon visual inspection of arterial FDG uptake. As previously reported, there was excellent inter-rater agreement (kappa=0.84) between the readers.11 To evaluate disease extent, FDG uptake was assessed by a single reader in 4 segments of the aorta (ascending, arch, descending thoracic, and abdominal) and in 11 branch arteries (innominate, carotids, subclavians, axillaries, iliacs, and femorals). The degree of arterial FDG uptake within each territory was visually assessed relative to liver. Vascular involvement within each territory was defined as FDG uptake greater than the liver by visual assessment.

Statistical Analysis

Agreement between PET scan assessment and MRA assessment was evaluated by percent overall agreement, Cohen’s kappa, and McNemar’s test. In cases of disagreement, McNemar’s test is useful to determine whether there is equal disagreement in both directions. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate which features on MRA (edema, wall thickness, stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm) were associated with reader impression of active vasculitis on PET scan and MRA.

Ethics and Informed Consent

All patients provided written informed consent. An institutional review board and radiation safety committee at the NIH approved the research.

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 84 patients were recruited into the study. There were 35 patients with GCA, 30 patients with TAK, and 19 disease comparators. Luminal abnormalities (stenosis, occlusion, aneurysm) were observed in 30/30 patients with TAK and 19/35 patients with GCA. A total of 133 MRA/PET paired studies were included, as some patients underwent multiple paired studies, performed at 6-month intervals. Baseline demographics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study Population Baseline Demographics

| GCA | TAK | Comparator Group | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Patients (n) | 35 | 30 | 19 | 84 |

|

| ||||

| MRA/PET Study | ||||

| Total (n) | 67 | 47 | 19 | 133 |

| 1 Study | 20 | 18 | 19 | 57 |

| 2 Studies | 5 | 7 | 0 | 12 |

| ≥3 Studies | 10 | 5 | 0 | 15 |

|

| ||||

| Age (Years ± SD) | 68. ± 8.3 | 32.5 ± 12.7 | 46.0 ± 21.6 | 48.9 ± 14.2 |

|

| ||||

| Sex (Female, %) | 28 (80%) | 20 (67%) | 14 (74%) | 62 (74%) |

|

| ||||

| Body Mass Index (± SD) | 27.7 ± 4.3 | 26.4 ± 6.9 | 26.5 ± 6.4 | 26.9 ± 5.9 |

|

| ||||

| Disease duration (Years ± SD) | 2.64 ± 2.42 | 10.60 ± 10.4 | N/A | 6.62 ± 6.4 |

MRA=magnetic resonance angiography, PET= 18F-flurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, SD=standard deviation, GCA=Giant cell arteritis, TAK=Takayasu’s arteritis

Assessment of Disease Extent on Imaging

A total of 966 vascular territories were assessed from 72 MRA/PET paired scans, as outlined in Table 2. Agreement for disease extent between MRA and PET was seen in 580 territories, where 206 territories were involved on both MRA and PET and 374 territories were not involved on either modality. This corresponded to a percent overall agreement of 60%, with Cohen’s kappa=0.22, consistent with fair strength of agreement. Of the 386 territories where there was disagreement between MRA and PET, territories were more likely to be involved on MRA than PET (304 vs 82, McNemar’s p<0.01).

Table 2.

Assessment of Extent of Disease on MRA and PET

| PET territory involved | PET territory not involved | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRA territory involved | 206 | 304 | 510 |

| MRA territory not involved | 82 | 374 | 456 |

| Total | 288 | 678 | 966 |

MRA=magnetic resonance angiography, PET= 18F-flurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

Assessment of Disease Activity on Imaging

There was moderate agreement on interpretation of MRA disease activity between the two readers (kappa=0.58). To evaluate disease activity, 133 paired MRA and PET studies were assessed, as displayed in Table 3. There was agreement between MRA and PET interpretation of disease activity in 90 studies (62 studies MRA+/PET+ and 28 studies MRA−/PET−). Percent overall agreement was 68% with Cohen’s kappa=0.30, indicating fair agreement. In the 43 studies where there was disagreement, MRA demonstrated disease activity in 23 studies and PET in 20 studies (McNemar’s test p=0.76), indicating in cases of disagreement MRA and PET were equally likely to be interpreted as active disease.

Table 3.

Assessment of Disease Activity on MRA and PET

| A. Total Paired Studies | B. Takayasu’s Arteritis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| PET | PET− | Total | PET+ | PET− | Total | ||

| MRA+ | 62 | 23 | 85 | MRA+ | 20 | 9 | 29 |

| MRA− | 20 | 28 | 48 | MRA− | 8 | 10 | 18 |

| Total | 82 | 51 | 133 | Total | 28 | 19 | 47 |

|

| |||||||

| C. Giant Cell Arteritis | D. Control | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| PET+ | PET− | Total | PET+ | PET− | Total | ||

| MRA+ | 40 | 7 | 47 | MRA+ | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| MRA− | 12 | 8 | 20 | MRA− | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Total | 52 | 15 | 67 | Total | 2 | 17 | 19 |

MRA=magnetic resonance angiography, PET= 18F-flurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

Disease activity was also assessed by subgroup, as shown in Table 3. Percent overall agreement was similar among the three groups (TAK 64%, Cohen’s kappa=0.24; GCA 72%, Cohen’s kappa=0.27; comparator group 63%, Cohen’s kappa=0.23). However, for cases of disagreement there was a difference in pattern among the three groups. For the TAK and GCA subgroups, McNemar’s test was p=1.0 and p=0.36, respectively, indicating in cases of disagreement MRA and PET were equally likely to be interpreted as active disease. For the comparator group, which included non-inflammatory vasculopathies, MRA was more likely to be interpreted as active vasculitis than PET (McNemar’s test p=0.02).

Features of MRA Associated with Imaging Interpretation

Multivariable logistic regression was performed to evaluate which features of MRA were directly associated with reader interpretation of disease activity on MRA. An increasing number of vascular territories on MRA showing edema (odds ratio (OR)=2.29, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.45–3.60, p<0.01) was associated with MRA interpretation of disease activity, whereas an increasing number of territories with increased wall thickness (OR=1.1, 95%CI=0.93–1.33, p=0.24) and stenosis (OR=0.90, 95%CI=0.75–1.07), p=0.24) was not significantly associated with interpretation of disease activity on MRA.

The association of features on MRA with reader interpretation of activity on a paired PET scan was also assessed. An increasing number of vascular territories on MRA showing edema (OR=1.36, 95% CI=1.10–1.70, p<0.01) and wall thickness (OR=1.17, 95%CI=1.01–1.37, p=0.04) were each independently associated with PET scan interpretation of disease activity. Stenosis was not associated with PET scan interpretation of disease activity (OR=0.93, 95%CI=0.81–1.07), p=0.33). Of the territories with edema, wall thickness, and stenosis on MRA, 64%, 48%, and 35%, respectively, had associated PET scan activity in the corresponding vascular territory. Patterns of agreement between MRA and PET were consistent across the 15 arterial territories under investigation.

Patients in whom both MRA and PET were interpreted as active disease had the highest number of territories with edema (MRA+/PET+ median 5 territories, MRA+/PET− median of 1 territory, MRA−/PET+ median of 0 territories, and MRA−/PET− median of 0 territories), as shown in Figure 1A. Patients who were active on both MRA and PET also had the greatest number of territories with increased wall thickness (MRA+/PET+ median 9 territories, MRA+/PET− median 5 territories, MRA−/PET+ median of 4 territories, and MRA−/PET− median of 2 territories), as shown in Figure 1B. There were few significant differences between PET scan activity and median number of territories with stenosis, as shown in Figure 1C. Representative images showing the association between edema and wall thickness on MRA, and corresponding vascular FDG uptake on PET, are shown in online Supplementary Figure.

Figure 1. Associations between Features of MRA and Imaging Activity Assessed by MRA and PET.

Patients were divided based on imaging assessment of disease activity (active versus inactive) by MRA and PET into 4 subgroups (MRA+/PET+, MRA+/PET−, MRA−/PET+, MRA−/PET). Associations of the 4 subgroups with the MRA features of edema, wall thickness, and stenosis are displayed. Patients with active disease on both MRA and PET (MRA+/PET+) had the greatest median number of territories with edema (A) and wall thickness (B), while there were fewer significant associations between number of territories with stenosis and imaging activity (C).

Association of Imaging and Clinical Features

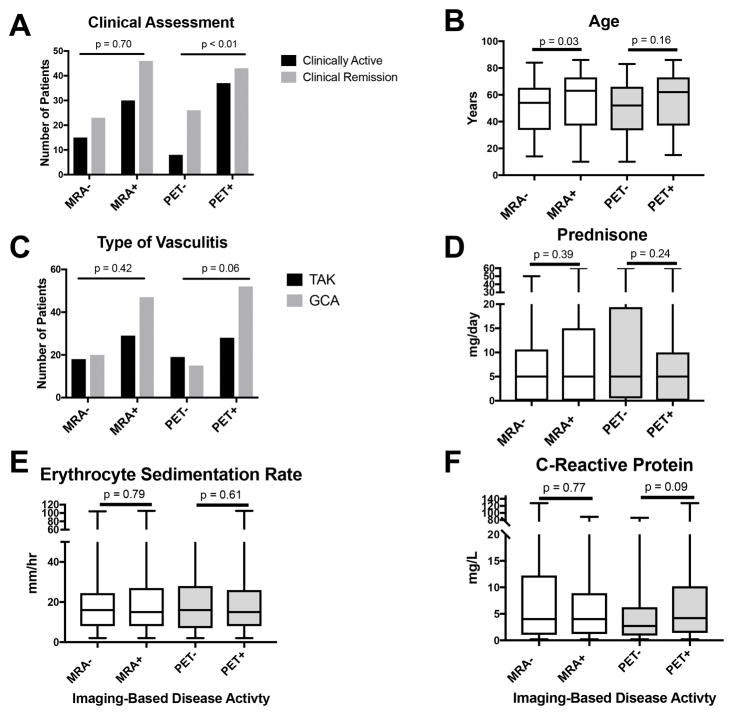

When assessing activity on imaging across the entire cohort, clinical disease activity assessment was significantly associated with PET scan interpretation of disease activity (55% concordance vs 45% discordance, p<0.01) but not with MRA interpretation (46% concordance vs 54% discordance, p=0.70) (Figure 2A). Increased mean age was significantly associated with disease activity by MRA (63 vs 54 years, p=0.03) but not by PET (62 vs 52 years, p=0.16) (Figure 2B). Type of vasculitis, prednisone dose, ESR, and CRP values did not significantly differ between patients with active versus normal MRA or PET studies. (Figures 2C–2F).

Figure 2. Association of Imaging-Based Interpretation of Vasculitis Disease Activity and Clinical Features of Disease in Large-Vessel Vasculitis.

There were few significant clinical differences between patients whose imaging studies [magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or positron emission tomography (PET)] were interpreted as active vasculitis versus normal. Clinically active disease compared to clinical remission was associated with increased PET interpretation of active vasculitis (A), and older age was significantly associated with increased MRA interpretation of active vasculitis (B). Type of vasculitis (giant cell arteritis (GCA) vs Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK)), daily prednisone dose, and acute phase reactant levels were not significantly associated with image interpretation by MRA or PET (C–F).

Additional details about the associations between clinical, serologic, and imaging features of disease in patients with LVV are shown in online Supplementary Tables 1–3. Notably, 94% patients with clinically active disease and 78% of patients in clinical remission had imaging activity on either PET, MRA, or both. Among 69 paired studies performed during clinical remission, PET scan activity was detected in 43 (62%) studies, MRA activity was detected in 46 (67%) studies, and activity was concurrently detected by PET and MRA in 35 (51%) studies. Acute phase reactants were not associated with imaging-based disease activity during active disease or clinical remission. Marked disease activity by PET and MRA was observed in patients with LVV during clinical remission with normal acute phase reactants (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Representative Abnormal FDG-PET and MRA Studies in a Patient with Giant Cell Arteritis in Clinical Remission.

A 72 year-old woman with giant cell arteritis underwent imaging studies 5 years after diagnosis. At the time of imaging, the patient was in clinical remission and had been tapered off all vasculitis-related medications. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within normal limits at 25mm/hr and c-reactive protein was 4.6 mg/L (normal <5mg/L). On FDG-PET, she had severe FDG uptake throughout the aorta and branch arteries (blue arrows), including the ascending and descending aorta (blue arrows on axial PET). On corresponding whole body MRA obtained on the same day as the PET scan, there were severe, bilateral stenoses in the subclavian/axillary arteries (yellow arrows) and increased wall thickness and edema throughout the aorta on axial STIR images (red arrow). These images highlight that patients with LVV can have marked disease activity on imaging studies while in clinical remission with normal acute phase reactants.

DISCUSSION

Complex associations between MRA, PET, and clinical assessment were identified in a prospective cohort of patients with LVV assessed at different time points in the disease course. When assessing disease extent, there was fair agreement between MRA and PET, but MRA identified a greater extent of vascular involvement than PET due to detection of both arterial wall abnormalities (wall thickness, edema) and luminal abnormalities (occlusion, aneurysm, and stenosis). When assessing disease activity, inter-rater agreement was greater for PET scan reads compared to MRA reads (kappa=0.84 vs 0.58), indicating that assessment of disease activity by PET is more reliable than MRA. Agreement in disease activity assessment between MRA and PET was observed in two-thirds of paired imaging studies; however, only disease activity assessment by PET, and not MRA, was associated with clinical assessment. Despite the significant association between PET and clinical assessment of disease activity, 51% of patients with LVV in clinical remission had evidence of ongoing disease activity by both PET and MRA. Thus, these findings support the concepts that MRA and PET capture complementary but different aspects of vascular biology and that imaging-based assessment of disease activity often differs from clinical assessment.

Specific features on MRA were associated with interpretation of vascular disease activity by MRA and PET. Edema, in increasing number of arterial territories, was the strongest risk factor for the increased likelihood that an MRA would be interpreted as active. Compared to wall thickness and stenosis, edema also most strongly correlated with PET scan activity within specific arterial territories. Wall thickness and edema on MRA were independently associated with global PET scan interpretation of disease activity. PET scan findings are therefore associated with abnormalities of the arterial wall and are not associated with features of damage to the arterial lumen. Vascular edema and increased wall thickness could be used as a proxy for PET scan activity when access to FDG-PET is not available.

Prior studies report conflicting results about the associations between clinical, serological, and imaging-based assessments of disease activity in LVV6,8,9,14–33. Interpretation of these studies are frequently limited due to small sample sizes, retrospective study design, lack of standardized imaging protocols applied to all study participants, and delay between imaging and clinical assessment with potential intervening treatment changes. Additionally, most of these studies focus on the time of initial diagnosis with relatively little imaging data available at later points in the disease course. The present study addresses these limitations in study design and shows that imaging findings, clinical assessment, and acute phase reactants do not necessarily correlate over the course of disease.

Although some disease activity assessment indices in LVV incorporate acute phase reactants into clinical definitions of disease activity10,34, this study defined clinical disease activity by symptoms alone without considering acute phase reactants. Using these definitions, ESR and CRP were not associated with imaging-based disease activity in patients with LVV during periods of clinically active disease or remission. Acute phase reactants, particularly at later time points in disease, are not useful to identify subsets of patients with LVV with active disease by PET or MRA.

Previous studies have demonstrated ongoing vascular disease activity by MRA6,18,35 and by PET7,11,26 in patients with LVV otherwise in apparent clinical remission. This study is the first to show that approximately half of patients with LVV have what appears to be ongoing disease activity on MRA and PET studies obtained concurrently during clinical remission. In absence of corresponding histology, a limitation inherent to most imaging studies in LVV, it is unclear whether the imaging abnormalities observed during clinical remission represent active vascular inflammation or non-specific changes related to vascular damage. However, these findings align with autopsy data36,37 and temporal artery biopsies performed during periods of apparent clinical remission11 which demonstrate subclinical vascular inflammation in LVV. Both disease specific factors (e.g. type of vasculitis, treatment status) and non-specific factors (e.g. age) were associated with imaging activity during clinical remission. These results suggest that vascular imaging abnormalities observed during clinical remission are likely driven by multiple factors including subclinical vasculitis, vascular repair, and secondary processes such as atherosclerosis in aging populations.

This study has some potential limitations. This was a single-center study, meaning reproducibility of these findings across other cohorts remains unknown. The study population was not an inception cohort, and most patients were enrolled later into the disease course. While this limits the ability to extrapolate the findings to patients with newly diagnosed LVV and likely influences the strength of associations between clinical, serologic, and imaging assessments, it is more similar to everyday clinical practice, where patients may be seen for the first time at any point in their disease course. Similarly, many patients were taking various immunosuppressive medications at the time of assessment which could impact imaging activity, particularly in the studies performed during clinical remission. Differentiating angiographic and PET findings in LVV versus atherosclerosis can sometimes be challenging. The methods used to define disease activity by clinical and imaging-based approaches were consistent with general approaches employed in prior studies8,11,15,19,38,39. Development of validated clinical definitions of disease activity and standardized definitions for imaging-based measurements of vascular activity are major unmet needs in LVV.

The primary objective of this study was to define the strength of agreement between MRA, PET, and clinical assessment to detect disease activity in LVV. This study does not address whether MRA and PET have clinical utility to guide medical decision-making in the ongoing management of patients with LVV. Previous studies have suggested PET predicts relapse and angiographic progression of disease11,40, whereas other studies have refuted this idea7,8. Prospective, longitudinal studies that examine the prognostic value of imaging findings in relationship to long-term clinical and angiographic outcomes are needed. Studies that examine the clinical utility of vascular imaging as a biomarker in LVV weighed against the potential costs and safety concerns of serial imaging should be conducted prior to the incorporation of specific forms of advanced imaging into clinical practice.

While there is much complexity in evaluating disease activity in LVV, findings from this study suggest that MRA and PET provide unique and complementary information in the assessment of LVV. PET scans are better suited to assess disease activity than MRA, and MRA studies are better than PET to identify disease extent including vascular damage. In clinical situations where PET imaging is not available or when radiation exposure is a concern, an increasing number of arterial territories with edema on MRA, and to a lesser extent wall thickness, could be used as a surrogate for PET scan activity. Approximately half of patients with LVV in clinical remission have evidence of vascular disease activity on concomitant PET and MRA studies, indicating a potential disconnect between clinical and imaging assessment of disease activity. Ultimately, prospective longitudinal studies are needed, ideally performed within randomized clinical trials, to determine the utility of incorporating these imaging modalities into clinical practice as a serial marker of disease activity in LVV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. KQ received funding from a Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium (VCRC)/Vasculitis Foundation (VF) Fellowship. The Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium (VCRC) is part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS). The VCRC is funded through collaboration between NCATS, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U54 AR057319).

Footnotes

Statements: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests for any author.

CONTRIBUTORS

KAQ, MAA, AAM, PAM, PCG contributed to the conception and design of this study. KAQ, MAA, AAM, JM, ACC, JSR, AAB, and EN, and PCG recruited patients into the study and participated in data collection. KAQ, MAA, JSR, AAB, and PCG contributed to the data analysis. All authors contributed to data interpretation, critically reviewed the article for important intellectual content, and approved the final draft for submission.

PRESENTED AT:

Part of this manuscript was presented at the 2017 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

ETHICS APPROVAL INFORMATION

An institutional review board and radiation safety committee at the NIH approved the research (NCT 02257866).

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1–11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blockmans D. The use of (18F)fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the assessment of large vessel vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:S15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blockmans D, Bley T, Schmidt W. Imaging for large-vessel vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:19–28. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32831cec7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cimmino MA, Camellino D. Large vessel vasculitis: which imaging method? Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14405. doi: 10.4414/smw.2017.14405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prieto-Gonzalez S, Depetris M, Garcia-Martinez A, et al. Positron emission tomography assessment of large vessel inflammation in patients with newly diagnosed, biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis: a prospective, case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1388–92. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheel AK, Meller J, Vosshenrich R, et al. Diagnosis and follow up of aortitis in the elderly. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1507–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.015651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blockmans D, de Ceuninck L, Vanderschueren S, et al. Repetitive 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in giant cell arteritis: a prospective study of 35 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:131–7. doi: 10.1002/art.21699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Both M, Ahmadi-Simab K, Reuter M, et al. MRI and FDG-PET in the assessment of inflammatory aortic arch syndrome in complicated courses of giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1030–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.082123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee KH, Cho A, Choi YJ, et al. The role of (18) F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in the assessment of disease activity in patients with takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:866–75. doi: 10.1002/art.33413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J, et al. Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:919–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-11-199406010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grayson PC, Alehashemi S, Bagheri AA, et al. Positron Emission Tomography as an Imaging Biomarker in a Prospective, Longitudinal Cohort of Patients with Large Vessel Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 doi: 10.1002/art.40379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1129–34. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langford CA, Cuthbertson D, Ytterberg SR, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Abatacept (CTLA-4Ig) for the Treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:837–45. doi: 10.1002/art.40044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meller J, Grabbe E, Becker W, et al. Value of F-18 FDG hybrid camera PET and MRI in early takayasu aortitis. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:400–5. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meller J, Strutz F, Siefker U, et al. Early diagnosis and follow-up of aortitis with [(18)F]FDG PET and MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:730–6. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1144-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Einspieler I, Thurmel K, Pyka T, et al. Imaging large vessel vasculitis with fully integrated PET/MRI: a pilot study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1012–24. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Leeuw K, Bijl M, Jager PL. Additional value of positron emission tomography in diagnosis and follow-up of patients with large vessel vasculitides. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:S21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman KA, Ahlman MA, Hughes M, et al. Diagnosis of Giant Cell Arteritis in an Asymptomatic Patient. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1135. doi: 10.1002/art.39517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews J, Al-Nahhas A, Pennell DJ, et al. Non-invasive imaging in the diagnosis and management of Takayasu’s arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:995–1000. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.015701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruschi M, De Leonardis F, Govoni M, et al. 18FDG-PET and large vessel vasculitis: preliminary data on 25 patients. Reumatismo. 2008;60:212–6. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2008.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs M, Briel M, Daikeler T, et al. The impact of 18F-FDG PET on the management of patients with suspected large vessel vasculitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:344–53. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1967-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karapolat I, Kalfa M, Keser G, et al. Comparison of F18-FDG PET/CT findings with current clinical disease status in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31:S15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi Y, Ishii K, Oda K, et al. Aortic wall inflammation due to Takayasu arteritis imaged with 18F-FDG PET coregistered with enhanced CT. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:917–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papathanasiou ND, Du Y, Menezes LJ, et al. 18F-Fludeoxyglucose PET/CT in the evaluation of large-vessel vasculitis: diagnostic performance and correlation with clinical and laboratory parameters. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e188–94. doi: 10.1259/bjr/16422950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada I, Nakagawa T, Himeno Y, et al. Takayasu arteritis: diagnosis with breath-hold contrast-enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:481–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(200005)11:5<481::aid-jmri3>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnaud L, Haroche J, Malek Z, et al. Is (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scanning a reliable way to assess disease activity in Takayasu arteritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1193–200. doi: 10.1002/art.24416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnani L, Versari A, Salvo D, et al. Disease activity assessment in large vessel vasculitis. Reumatismo. 2011;63:86–90. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2011.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Besson FL, Parienti JJ, Bienvenu B, et al. Diagnostic performance of (1)(8)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in giant cell arteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1764–72. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1830-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blockmans D, Stroobants S, Maes A, et al. Positron emission tomography in giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: evidence for inflammation of the aortic arch. Am J Med. 2000;108:246–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter MA, Melzer RA, Schindler C, et al. The value of [18F]FDG-PET in the diagnosis of large-vessel vasculitis and the assessment of activity and extent of disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:674–81. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Incerti E, Tombetti E, Fallanca F, et al. (18)F-FDG PET reveals unique features of large vessel inflammation in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1109–18. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3639-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webb M, Chambers A, AAL-N, et al. The role of 18F-FDG PET in characterising disease activity in Takayasu arteritis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:627–34. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barra L, Kanji T, Malette J, et al. Imaging modalities for the diagnosis and disease activity assessment of Takayasu’s arteritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misra R, Danda D, Rajappa SM, et al. Development and initial validation of the Indian Takayasu Clinical Activity Score (ITAS2010) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1795–801. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tso E, Flamm SD, White RD, et al. Takayasu arteritis: utility and limitations of magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1634–42. doi: 10.1002/art.10251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dellavedova L, Carletto M, Faggioli P, et al. The prognostic value of baseline (18)F-FDG PET/CT in steroid-naive large-vessel vasculitis: introduction of volume-based parameters. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:340–8. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ostberg G. Morphological changes in the large arteries in polymyalgia arteritica. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1972;533:135–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soussan M, Nicolas P, Schramm C, et al. Management of large-vessel vasculitis with FDG-PET: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e622. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muratore F, Pipitone N, Salvarani C, et al. Imaging of vasculitis: State of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30:688–706. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eshet Y, Pauzner R, Goitein O, et al. The limited role of MRI in long-term follow-up of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;11:132–6. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.