Abstract

Objective

The physiology of nearly all mammalian organisms are entrained by light and exhibit circadian rhythm. The data derived from animal studies show that light influences immunity and these neurophysiologic pathways are maximally entrained by the blue spectrum. Here, we hypothesize that bright blue light reduces acute kidney injury (AKI) by comparison to either bright red or standard, white fluorescent light in mice subjected to sepsis. To further translational relevance, we performed a pilot clinical trial of blue light therapy in human subjects with appendicitis.

Design

Laboratory animal research, pilot human feasibility trial

Setting

University basic science laboratory and tertiary care hospital

Subjects

Male C57BL/6J mice, adult (>17 years) patients with acute appendicitis

Interventions

Mice underwent cecal ligation and puncture and were randomly assigned to a 24-hour photoperiod of bright blue, bright red or ambient white fluorescent light. Subjects with appendicitis were randomized to receive postoperatively standard care or standard care plus high illuminance blue light.

Measurements and Main Results

Exposure to bright blue light enhanced bacterial clearance from the peritoneum, reduced bacteremia and systemic inflammation, and attenuated the degree of AKI. The mechanism involved an elevation in cholinergic tone that augmented tissue expression of the nuclear orphan receptor Rev-Erbα and occurred independent of alterations in melatonin or corticosterone concentrations. Clinically, exposure to blue light after appendectomy was feasible and reduced serum IL-6 and IL-10 concentrations.

Conclusions

Modifying the spectrum of light may offer therapeutic utility in sepsis.

Keywords: light, sepsis, circadian rhythms, biological clocks, nuclear receptor subfamily 1, inflammation

Introduction

Visible light (400–700 nm) modifies the capacity with which an organism responds to stress, and this physiology exhibits both circannual (seasonal) and diurnal (daily) variation.(1–3) For example, in response to the shorter photoperiod of the approaching winter, animals exhibit an enhancement in immune competence that improves the survival from sepsis.(2, 4) Even on a daily basis, there occurs a diurnal variation in circulating and tissue leukocyte concentrations that modifies the innate immunity.(5–7)} Thus a paradigm emerges in which a circadian oscillation in immunity serves to bolster immune competence during periods of animal activity, when the probability of encountering microbial threat is elevated.(5, 6, 8) And the dominant regulatory cue is light.(6, 8–10)

Light travels through a nonvisual optic pathway to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), where it serves as the primary environmental signal entraining an autonomous transcription-translation feedback loop comprised of a core set of genes: Clock, Bmal1, Period1–3 (Per) and Cryptochrome1–2 (Cry).(11–13) A parallel pathway comprised of the nuclear receptor Rev-Erbα also serves in a negative feedback loop to regulate Bmal1. Peripheral tissues also exhibit circadian oscillations in these clock genes.(11–13) These peripheral ‘clocks’ have demonstrable roles in regulating immune cell function.(14–17) In particular, Rev-Erbα has been shown to link the macrophage (Mφ) circadian clock to inflammatory function, including a selective and negative regulation of Mφ cytokines, such as IL-6 and CCL2.(16, 18–20) It is becoming apparent that many facets of immunity are regulated by individual components of this clock protein machinery, which are synchronized centrally by the SCN to temporally coordinate host physiology.

The central biological clock of the SCN possesses a 24-hour periodicity reflective of its dominant environmental cue, light, and it is the lower spectrum of blue light that maximally entrains this clock biology and circadian rhythms.(21–24) We recently showed that high illuminance, blue spectrum light can attenuate neutrophilic inflammation and organ injury in two murine models of warm ischemia/reperfusion.(25) Others have shown that fish exposed to green or blue LEDs during starvation exhibited less oxidative stress in comparison to those exposed to red LEDs.(26) These data suggest that the blue spectrum of light is a critical determinant of its biologic effects. In this study, we turn our attention to sepsis. Using a clinically relevant murine model of intraabdominal sepsis, we show that high illuminance, blue spectrum light mediates adaptive changes in the immunity, in part through induction of tissue Rev-Erbα, that protects against organ injury. We conduct a small pilot clinical trial in subjects with appendicitis to show clinical feasibility and to begin to explore biological relevance.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Antibodies for REV-ERBα (174309) and tubulin (ab4074) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The β3 antagonist SR59230A (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 5 mg/kg. Propranolol (Sigma Aldrich) was administered subcutaneously at 0.5 mg/kg. (-)-Nicotine (Sigma Aldrich) was administered i.p. at 0.4 mg/kg. Alpha-bungarotoxin (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) was administered i.p. at 1 μg/kg. The REV-ERBα agonist SR9009 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) was dissolved in vehicle (15% Kollifer) and administered i.p. at 100 mg/kg.

Animal experimentation

We randomly assigned 8–12 week old male C57BL/6J and Nr1d1tm1Ven/LazJ (REV-ERBα+/− heterozygous) (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to a specific experiment. We performed CLP as previously described (27).

Mice were monitored using DSI HD-X11 implanted wireless telemetry (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) as previously performed (28). Data analysis was performed using Ponemah v5.20 (DSI, St. Paul, MN).

For all studies, one investigator performed the surgical experimentation and collected the samples. An investigator blinded to the specific treatment then analyzed the data.

Exposure to Light

All experiments were conducted in a climatic room maintained on a day = night 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle (lights on from 0800 to 20:00) at an ambient temperature of 21 ± 2°C and a relative humidity of 60%. All experimentation was initiated at CT2 (CT=circadian time set 0 as previous dawn). Two Day-Light Classic DL930 light were used (Uplift Technologies, Dartmouth, NS) as previously described (25). These lamps were fitted with blue (peak 442 nm) and red (peak 617 nm) filters (Lee Filters, Burbank, CA) and positioned over each cage to ensure identical illuminances of 1400 lumens (25). The heat emission modestly affects the cage temperatures (25 ± 2°C) with no significant difference in the exposures of interest (25).

Mice underwent CLP and then were randomly assigned to one of three lighting groups: red (617 nm, 1400 lux), blue (442 nm, 1400 lux), and ambient light (fluorescent white light, 400 lux) (25). These lighting environments were administered for 24 hours immediately following experimentation.

Organ Physiology

Renal function was determined by assaying serum for Cystatin C, using an enzyme immunoassay kit (R&D, Minneapolis, MN). Cystatin C has emerged as a more precise marker of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (29).

Immunoblot

Total tissue protein lysate was electrophoresed in a 15% SDS-PAGE gel and developed as previously described (30). Densitometry was performed by the NIH Image J64 program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Cytokine concentration

TNFα, IL-6, and IL-10 concentrations were quantified using an ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (27).

Bacterial culture

The peritoneal cavity was washed with 1 mL PBS under sterile conditions. Peritoneal lavage and whole blood were subjected to 10-fold dilutions and cultured overnight in 5% sheep blood agar (Teknova, Hollister, CA). CFU were quantified by manual counting (31).

Corticosterone concentration

Serum corticosterone concentration was determined by ELISA (Enzo Life Science, Ann Arbor, MI) (25).

Pilot human trial

Study subjects

We conducted a pilot clinical trial between January 1, 2015 and December 1, 2015 in which we sought to determine the feasibility of applying high illuminance blue spectrum lighting to subjects within the perioperative hospital setting and possessed the primary objective of successfully integrating the intervention into the delivery of perioperative care. This step was considered vital and prerequisite to embarking upon a larger clinical trial powered for clinical endpoints of interest. To achieve this end required an appreciation for the diverse interests/concerns of all involved stakeholders: nurses, physicians and patients. Thus, we chose a subject population experiencing intraabdominal sepsis, but retaining cognitive and decision-making capacity: appendicitis. All subjects 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of appendicitis and undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy were included. Patients were excluded if they were blind, had sustained a traumatic brain injury, were immunocompromised, or had an anticipated survival of less than 48 hours.

Protocol

Randomization was performed by computer-generation of n=20 treatment allocations. Treatment assignments were placed in sealed, opaque envelopes. Subjects assigned to blue light were fitted with blue filtered goggles (Lee Filters, Burbank, CA) and exposed to a Day*Light Classic Light for 18 hours beginning immediately postoperatively. The light was positioned on a stand with rolling casters, which enabled accurate positioning of the light in front of the subject regardless of the subject’s location within the hospital (i.e., postoperative anesthesia care unit (PACU) or inpatient room). Combined with the goggles, this intervention recapitulated the experimental conditions of our murine studies and ensure the transmission of a bright (1400 lux) blue (peak 442 nm) light when the subject is within 12 inches. An investigator ensured appropriate light positioning and monitored compliance. The subjects assigned to the control group underwent usual care without any alterations of the ambient hospital lighting conditions.

End Points

Our primary endpoint was feasibility as defined by successful administration of and compliance with the intervention of high illuminance, blue spectrum lighting. Additional endpoints considered to be of translational relevance included serum concentrations of TNFα, IL-6 and IL-10 recorded at the time of admission preoperatively and approximately 18 hours postoperatively.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13SE software (College Station, TX). Continuous data were compared by T-test. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for non-parametric data. Physiologic data were modeled using a fractional polynomial panel analysis. For the pilot trial, outcomes were evaluated on an intent-to-treat basis. An investigator blinded to the specific group allocations then analyzed the data. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study Approval

We performed all animal experiments in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (16027633). The clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board (PRO#13080427). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to inclusion in the study.

Results

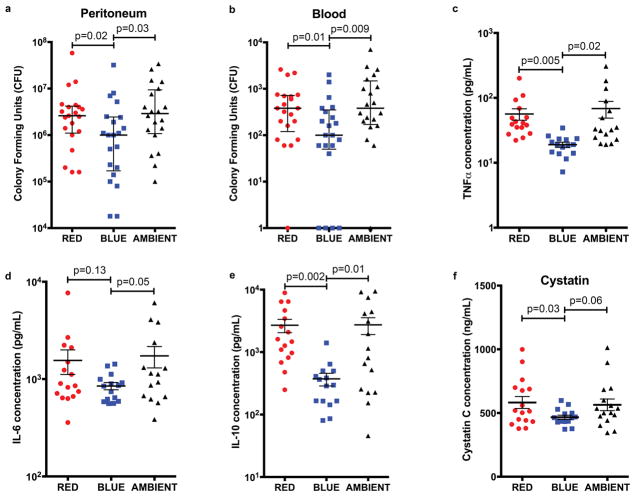

Blue light enhances control of the infection and reduces systemic inflammation and organ injury during CLP sepsis

Initially we explored whether exposure to bright blue (BLUE), bright red (RED), or standard fluorescent, white light (AMBIENT) after sepsis altered immunity and control of the infection. We included an ambient fluorescent light exposure to replicate the typical indoor lighting environment (i.e., the hospital). As shown in Figure 1a, septic mice exposed to blue light exhibited a 60% reduction in bacterial burden within the peritoneal cavity, relative to either red or white light. Blue light also significantly reduced the magnitude of bacteremia (Fig. 1b). This enhanced bacterial clearance was accompanied by attenuated systemic inflammation, as blue light reduced serum concentrations of TNFα, IL-6 and IL-10 by comparison red or ambient light (Figs. 1c–e): BLUE vs. RED vs. AMBIENT: TNFα: 19.0 vs. 56.5 pg/mL (p=0.005) vs. 68.5 pg/mL (p=0.02); IL-6: 849 vs. 1555 pg/mL (p=0.13) vs. 1732 pg/mL (p=0.05); IL-10: 372 vs. 2696 pg/mL (p=0.002) vs. 2736 pg/mL (p=0.01). An exaggerated immune response is postulated to underlie the organ injury of sepsis, and TNFα is a key mediator in the pathogenesis of AKI. Therefore, we next explored whether or not blue light altered the risk of AKI (32). As shown in Figure 1f, septic mice exposed to blue light experienced reduced AKI as evidenced by lower serum Cystatin C concentrations, by comparison to red and ambient light: BLUE 467 ng/mL vs. RED 582 ng/mL (p=0.03) and vs. AMBIENT 564 ng/mL (p=0.06).

Figure 1. Blue light enhances control of the infection and reduces systemic inflammation and organ injury during CLP sepsis.

Mice underwent CLP and then were exposed to red, blue, or ambient light for 24 hours. a and b, Peritoneal lavage fluid and whole blood were cultured for bacteria (18 total mice per group for all 5 experiments combined). bar = median c–f, Serum was analyzed for c, Cystatin C d, TNFα, e, IL-6, and f, IL-10 concentration (16 total mice per group for all 4 experiments combined) mean±sem.

Blue light functions through a cholinergic pathway to attenuate inflammation and organ injury during CLP

We were interested in understanding the physiologic mechanisms by which blue light exerted its effects. The mice we used are naturally deficient in melatonin (33, 34), and we observed little differences in systemic corticosterone concentrations in blue, red, and ambient exposed mice (Supplemental Figure 1a). And finally, we observed no significant differences in animal activity, a validated surrogate marker of circadian rhythms (Supplemental Figure 1b) (35, 36). Thus, in favorably modifying the biology of sepsis, blue light uses a pathway independent of the central circadian effectors melatonin and corticosteroids.

We next investigated whether or not blue light altered autonomic tone. We observed that septic mice exposed to blue light exhibited lower heart rates and an early reduction in low frequency/high frequency (LF/HF), suggesting a withdrawal of adrenergic tone (Fig. 2a and 2b). However, pharmacologic antagonism of the β3-adrenoreceptor (SR59230A) did not reduce systemic inflammation, and a broad β-adrenoreceptor antagonist (propranolol) only reduced IL-10 concentrations (Supplemental Figure 2). Reduced LF/HF may be due to elevated cholindergic tone, and mice exposed to blue light exhibited elevated HF (i.e., a parameter of parasympathetic tone), by comparison to mice exposed to red light (Fig. 2c). Repeating these experiments to determine the effects of modulating cholinergic tone on our prior endpoints of interest: serum cytokine concentration and tissue injury. We observed that blue light attenuated inflammation and AKI, but these effects were prevented with the nicotine acetylcholine receptor antagonist α-bungarotoxin (Fig. 2d). The corollary was also observed; augmenting cholinergic tone with nicotine produced similar effects as blue light in reducing systemic inflammation (Fig. 2e). Collectively these data suggest that blue light augments cholinergic activity in attenuating the inflammation induced by CLP sepsis.

Figure 2. Blue light functions through a cholinergic pathway to attenuate inflammation and organ injury during CLP sepsis.

a–c, Mice underwent laparotomy and implantation of a DSI HD-X11 telemetry device. After 24 hours of recovery, mice underwent CLP and were exposed to a 24 hour photoperiod of high illuminance blue or red spectrum light and monitored for 24 hours. Heart rate (HR) was continuously monitored. LF/HF ratio was calculated as a parameter of sympathetic tone and LF as a parameter of parasympathetic tone (57, 58) Each point is a single measurement of a single mouse at a single timepoint. Lines and colored areas represent a fractional polynomial estimate of the mean ± 95% confidence interval of each parameter for each cohort of red (n=8) and blue (n=8) light exposed mice. d, Mice underwent CLP and were randomized to receive α-bungarotoxin (1μg/kg, i.p.) or equivolume vehicle and then exposure to a 24 hour photoperiod of either high illuminance red or blue spectrum light. Serum was analyzed for TNFα, IL-6, IL-10 and Cystatin C concentrations (10 total mice per group for all 3 experiments combined). mean±sem e, Mice underwent CLP and then received either nicotine (1mg/kg, i.p.) or equivolume control. After 24 hours serum was analyzed for TNFα, IL-6, IL-10 and Cystatin C concentrations (9 total mice per group for all 3 experiments combined). mean±sem

Blue light induces the nuclear receptor Rev-Erbα in reducing the inflammation and organ injury of sepsis

Diurnal variation in immune function is evident, and the molecular components of the clock machinery have been shown to modulate immunity (5, 6). In particular, the orphan nuclear receptor Rev-Erbα has been shown to attenuate macrophage (Mφ) inflammatory cytokine production. Thus, we hypothesized that blue light mediates its effects through an induction of Rev-Erbα, and explored whether or not augmenting or inhibiting Rev-Erbα altered the effects of blue light on the biology of sepsis (16, 19). We observed that early after CLP (i.e., within 8 hours), blue light induced elevated expression of Rev-Erbα in the spleens of septic mice (Fig. 3a). The administration of the biochemical Rev-Erbα agonist (SR9009) at an early time point (i.e., 4 hours) after CLP significantly reduced serum cytokine concentrations (Fig. 3b). Cystatin C concentrations were also lower with SR9009, though this did not attain statistical significance. By contrast, heterozygous Rev-Erbα+/ − mice subjected to CLP, were no longer protected by blue light (Fig. 3c). And finally, the administration of nicotine rapidly induced elevated splenic expression of Rev-Erbα (Fig. 3d). Thus, one mechanism by which blue light protects in sepsis is by augmenting cholinergic tone and the expression of Rev-Erbα.

Figure 3. Blue light induces the nuclear receptor REV-ERBα in reducing the inflammation and organ injury of sepsis.

a, Mice underwent CLP and were exposed to red, blue, or ambient light for 8 hours, at which time point organs were harvested. Tissue expression of REV-ERBα and tubulin was analyzed by immunoblot. (4 mice total in each group). Corresponding densitometry blots compare splenic REV-ERBα expression from septic mice exposed to red, blue, or ambient light. b, Mice underwent CLP and after 4 hours were administered SR9009 (5mg/kg, i.p.). After a total of 24 hours, serum was harvested and assayed for TNFα, IL-6, IL-10 and Cystatin C concentrations. mean±sem (n=8 mice per group) c, Wild type and heterozygous REV-ERBα+/ − mice underwent CLP and were exposed to either red or blue light for 24 hours, at which point serum was harvested and assayed for TNFα, IL-6, IL-10 and Cystatin C concentrations. mean±sem (n=7 mice per group). d, Mice were randomized to receive nicotine (0.4 or 2.0 mg/kg, i.p.) or equivolume normal (0.9%) saline. After 8 hours the organs were harvested, and the tissue expression of REV-ERBα and tubulin was analyzed by immunoblot. (4 mice total in each group). Corresponding densitometry blots compare splenic REV-ERBα expression from septic mice administered normal (0.9%) saline, nicotine (0.4 mg/kg) and nicotine (2.0 mg/kg).

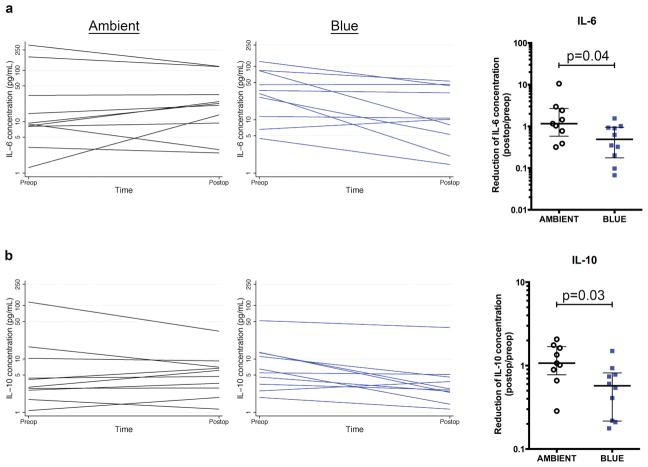

Blue light reduces serum cytokine concentrations in humans with appendicitis

We translated these observations into a pilot clinical feasibility trial of blue light therapy for appendicitis (Supplemental Table 1). Compliance was 100% with the intervention of blue goggles. Blue light did appear to affect the human biologic response to appendicitis (Figure 4). Eight of ten (90%) subjects allocated to blue light exhibited reductions in IL-6 in comparison to four of ten (40%) exposed to standard hospital lighting (p=0.07); for IL-10 the proportions were 9/10 (90%) vs. 4/10 (50%), p=0.03. TNFα concentrations were beneath the lowest detectable concentration of the standard curve for all serum samples.

Figure 4. Blue light reduces systemic serum cytokine concentrations in humans with appendicitis.

Human subjects with appendicitis were exposed postoperatively to either blue light or ambient light for 18–24 hours. Serum was harvested preoperatively and 24 hours postoperatively and analyzed for a, IL-6 concentration and b, IL-10 concentration. Panel graphs depict serum IL-6 and IL-10 concentrations for each subject at time of admission preoperatively and at approximately 18 hours postoperatively. Corresponding box plots depict median and interquartile range of fold reduction in IL-6 and IL-10, comparing postoperative to preoperative concentrations. (n=10 subjects per group)

Discussion

Our data support that light can acutely modify the biology of sepsis, and specifically that the spectrum is a critical determinant of its effects. A short exposure to blue light attenuates organ injury when the treatment is started after the induction of bacterial peritonitis. The protection may be mediated by enhanced immunocompetence, as it appears that blue light accelerates clearance of the infection, thereby reducing the systemic elaboration of mediators, such as TNFα, considered causal in the development of organ dysfunction, such as AKI (32). An intervention of blue light therapy is feasible when delivered after surgery, a clinically relevant and readily achievable time point of administration. And though preliminary, our pilot clinical data suggest translational relevance to human biology. Thus, acute blue light exposure may offer therapeutic utility to target the infection, control systemic inflammation and mitigate organ injury in clinical circumstances that do not permit pretreatment, such as sepsis (Supplementary Figure 3).

One mechanism by which light may alter the response to sepsis is through photoimmunomodulation.(1, 7, 37–40) We previously showed that blue light functioned through an intact optic pathway to reduce the tissue injury of I/R. Though not specifically studied herein, we hold that the eye is the gateway by which blue light enhanced immunity during CLP sepsis. Nearly every facet of immunity exhibits a circadian pattern and appears under the regulatory influence of light (6, 8, 10). Immunologically, this manifests as an increase in chemoattractants, leukocyte trafficking, inflammatory cytokines, and phagocytic ability in the hours preceding the commencement of activity.(5, 6, 17, 41, 42) On a daily basis light entrains a circadian oscillation in leukocyte emigration into tissues that alters the susceptibility to infectious insults. In the hours preceding the active phase, circulating Ly6Chi monocytes and tissue leukocyte populations peak, which correlate with enhanced bacterial clearance.(7) Thus, immunosurveillance is bolstered ahead of activity and feeding, a period of elevated probability of encountering microbial threat and risk of infection.

Light travels through this optic pathway to regulate the central clock machinery of the SCN, which is particularly entrained by blue light.(11, 13) Cryptochromes, the photoactive pigments in the eye, are maximally activated by light of the lower (400–450 nm) blue spectrum, and mice lacking the cryptochrome 2 gene exhibit a lower sensitivity to acute light induction of SCN clock proteins.(23) We believe this heightened sensitivity to blue spectrum underlies our prior observations in I/R, and those herein of sepsis, that blue light, above equally bright red light or ambient white light, most profoundly alters mammalian biology.

The SCN clock keeps peripheral tissues in harmony via the pineal gland, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the ANS and their respective hormones melatonin, glucocorticoids, and catecholamines.(43) The prototypical mediator of photoimmunomodulation is melatonin, though corticosteroid stress hormones also exhibit circadian rhythm and may influence immunity.(6, 8, 10, 44) However, neither of these systems appeared to be involved in our studies.(25) Rather, blue light engaged a cholinergic pathway to attenuate the inflammation of CLP sepsis. This mechanism differed from what we observed during I/R, in which blue light withdrew adrenergic tone to attenuate neutrophil influx and tissue injury (25). A cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway has been well characterized, in which systemic inflammation and tissue injury are attenuated by vagus nerve signaling.(45, 46) This pathway impinges upon the spleen, and our data suggest that blue light also alters splenic clock biology (see below). Whether a cholinergic pathway and/or the spleen mediate the observed enhanced control of the infection necessitates additional investigation, as do the contextual differences between sepsis and I/R in the ANS pathways engaged by blue light.

Peripheral tissues also possess this clock protein machinery, which regulates phenotypic function (11, 13, 14, 16, 47). The cellular response to either ischemia or LPS is dependent upon the timing of the insult relative to this cycle and the expression of these proteins.(8, 47, 48) Bmal1 has been characterized as ‘anti-inflammatory’, attenuating NFκB and IL-6 production in mice during endotoxemia.(47) We focused our experimental design on Rev-Erbα, which can repress inflammatory Mφ cytokine production.(16, 18) By repressing Mφ IL-10, Rev-Erbα augments phagolysosomal maturation and enhances microbicidal function against mycobacterium.(49–51) Thus, we hypothesized that an augmentation in Mφ Rev-Erbα would ideally explain our observation of enhanced bacterial clearance, yet reduced systemic inflammation; and this is what we observed. Whether Rev-Erbα alters microbicidal (e.g., phagocytosis) function to enhance bacterial clearance remains to be determined, as do the specific Rev-Erbα-dependent alterations in immune cell function that underlie reduced inflammation. Despite considerable evidence describing the ramifications of light on animal biology, human observational studies have failed to identify an association between light exposure and clinical outcomes (52–54). However, light is complex, defined by the photoperiod, the illuminance and the spectrum, and no study has fully incorporated this complexity of light into its study design. Once hospitalized a patient is exposed to a very different illuminance, photoperiod, and spectrum. Illuminance degrades from an outside brightness exceeding 30,000 lux to <400 lux inside at the hospital bed (39, 55). The photoperiod is perturbed by nearly continuous, low level lighting, and the spectrum of fluorescent light deviates considerably from the rich in blue spectrum of natural light (38, 56). We attempted to address these limitations by developing a clinical intervention that replicated the properties of the blue light used in our animal experimentation. Though preliminary, our pilot data suggest that this blue light can acutely modify human biology. However, much translational investigation remains in determining the relevance of blue light as a therapeutic modality for humans with sepsis. There are notable biological differences between nocturnal (i.e., mice) and diurnal (i.e., humans) subjects. We need to confirm that the specific clock biology mechanisms operant in vivo in our murine models are also induced in humans experiencing the many forms of sepsis (pneumonia, diverticulitis) that present for clinical care. Furthermore, we need to study a more ‘typical’ septic cohort and more clinically relevant outcomes, such as organ injury.

Sepsis continues to remain a considerable health care burden. Evolution has developed a biological toolbox that underlies adaptive alterations in immunity to enhance our defense mechanisms at a time of greatest likelihood of exposure to this threat.(3, 38, 40). The emerging paradigm is that the time of day is critical to the nature of the immune response to sepsis, and that light, is the principle regulatory cue. Our data suggest that blue light can be used therapeutically during sepsis to modulate these mechanisms to mitigate inflammation and organ injury. If light does impart therapeutic value, further investigation to determine the precise characteristics (illuminance, photoperiod, wavelength) will be critically important to optimize its potential clinical translation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding:

Financial support was provided by a Basic/Translational Research Training Fellowship Grant awarded by the Surgical Infection Society (MRR), R01 GM082852 (MRR), R01 GM116929 (MRR), and T32GM008516 (AJL) from the National Institutes of Health.

This work supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 GM082852 (MRR), R01 GM116929 (MRR) and a research training grant (5T32GM008516) from the National Institutes of Health (AJL).

Footnotes

Copyright form disclosure: Drs. Lewis, Griepentrog, Zuckerbraun, and Rosengart received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zuckerbraun disclosed government work. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nelson RJ. Seasonal immune function and sickness responses. Trends in immunology. 2004;25(4):187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prendergast BJ, Kampf-Lassin A, Yee JR, et al. Winter day lengths enhance T lymphocyte phenotypes, inhibit cytokine responses, and attenuate behavioral symptoms of infection in laboratory rats. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2007;21(8):1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haldar C, Ahmad R. Photoimmunomodulation and melatonin. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology B, Biology. 2010;98(2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prendergast BJ. Behavioral tolerance to endotoxin is enhanced by adaptation to winter photoperiods. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(4):540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheiermann C, Kunisaki Y, Lucas D, et al. Adrenergic nerves govern circadian leukocyte recruitment to tissues. Immunity. 2012;37(2):290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheiermann C, Kunisaki Y, Frenette PS. Circadian control of the immune system. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13(3):190–198. doi: 10.1038/nri3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellet MM, Deriu E, Liu JZ, et al. Circadian clock regulates the host response to Salmonella. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(24):9897–9902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120636110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arjona A, Silver AC, Walker WE, et al. Immunity’s fourth dimension: approaching the circadian-immune connection. Trends in immunology. 2012;33(12):607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castanon-Cervantes O, Wu M, Ehlen JC, et al. Dysregulation of inflammatory responses by chronic circadian disruption. Journal of immunology. 2010;185(10):5796–5805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silver AC, Arjona A, Walker WE, et al. The circadian clock controls toll-like receptor 9-mediated innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2012;36(2):251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, et al. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(10):764–775. doi: 10.1038/nrg2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunlap JC. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell. 1999;96(2):271–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Partch CL, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(2):90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi M, Shimba S, Tezuka M. Characterization of the molecular clock in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30(4):621–626. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452(7186):442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbs JE, Blaikley J, Beesley S, et al. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha mediates circadian regulation of innate immunity through selective regulation of inflammatory cytokines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(2):582–587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106750109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller M, Mazuch J, Abraham U, et al. A circadian clock in macrophages controls inflammatory immune responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(50):21407–21412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam MT, Cho H, Lesch HP, et al. Rev-Erbs repress macrophage gene expression by inhibiting enhancer-directed transcription. Nature. 2013;498(7455):511–515. doi: 10.1038/nature12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato S, Sakurai T, Ogasawara J, et al. A circadian clock gene, Rev-erbalpha, modulates the inflammatory function of macrophages through the negative regulation of Ccl2 expression. Journal of immunology. 2014;192(1):407–417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis AM, Bellet MM, Sassone-Corsi P, et al. Circadian clock proteins and immunity. Immunity. 2014;40(2):178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narasimamurthy R, Hatori M, Nayak SK, et al. Circadian clock protein cryptochrome regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(31):12662–12667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209965109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sancar A. Regulation of the mammalian circadian clock by cryptochrome. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(33):34079–34082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thresher RJ, Vitaterna MH, Miyamoto Y, et al. Role of mouse cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptor in circadian photoresponses. Science. 1998;282(5393):1490–1494. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tosini G, Ferguson I, Tsubota K. Effects of blue light on the circadian system and eye physiology. Mol Vis. 2016;22:61–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan D, Collage RD, Huang H, et al. Blue light reduces organ injury from ischemia and reperfusion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515296113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi CY, Shin HS, Choi YJ, et al. Effect of LED light spectra on starvation-induced oxidative stress in the cinnamon clownfish Amphiprion melanopus. Comparative biochemistry and physiology Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology. 2012;163(3–4):357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Guo L, Collage RD, et al. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) Ialpha mediates the macrophage inflammatory response to sepsis. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2011;90(2):249–261. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0510286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis AJ, Yuan D, Zhang X, et al. Use of Biotelemetry to Define Physiology-Based Deterioration Thresholds in a Murine Cecal Ligation and Puncture Model of Sepsis. Critical care medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song S, Meyer M, Turk TR, et al. Serum cystatin C in mouse models: a reliable and precise marker for renal function and superior to serum creatinine. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2009;24(4):1157–1161. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsung A, Klune JR, Zhang X, et al. HMGB1 release induced by liver ischemia involves Toll-like receptor 4 dependent reactive oxygen species production and calcium-mediated signaling. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204(12):2913–2923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng M, Scott MJ, Loughran P, et al. Lipopolysaccharide clearance, bacterial clearance, and systemic inflammatory responses are regulated by cell type-specific functions of TLR4 during sepsis. Journal of immunology. 2013;190(10):5152–5160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu C, Chang A, Hack BK, et al. TNF-mediated damage to glomerular endothelium is an important determinant of acute kidney injury in sepsis. Kidney international. 2014;85(1):72–81. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebihara S, Marks T, Hudson DJ, et al. Genetic control of melatonin synthesis in the pineal gland of the mouse. Science. 1986;231(4737):491–493. doi: 10.1126/science.3941912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasahara T, Abe K, Mekada K, et al. Genetic variation of melatonin productivity in laboratory mice under domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(14):6412–6417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914399107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verwey M, Robinson B, Amir S. Recording and analysis of circadian rhythms in running-wheel activity in rodents. J Vis Exp. 2013;(71) doi: 10.3791/50186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mistlberger RE. Circadian regulation of sleep in mammals: role of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;49(3):429–454. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson RJ, Demas GE, Klein SL, et al. Seasonal Patterns of Stress, Immune Function and Disease. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castro R, Angus DC, Rosengart MR. The effect of light on critical illness. Critical care. 2011;15(2):218. doi: 10.1186/cc10000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castro RA, Angus DC, Hong SY, et al. Light and the outcome of the critically ill: an observational cohort study. Critical care. 2012;16(4):R132. doi: 10.1186/cc11437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walton JC, Weil ZM, Nelson RJ. Influence of photoperiod on hormones, behavior, and immune function. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.12.003. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurepa Z, Rabatic S, Dekaris D. Influence of circadian light-dark alternations on macrophages and lymphocytes of CBA mouse. Chronobiology international. 1992;9(5):327–340. doi: 10.3109/07420529209064544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hriscu ML. Modulatory factors of circadian phagocytic activity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1057:403–430. doi: 10.1196/annals.1356.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:445–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson RJ, Drazen DL. Melatonin mediates seasonal changes in immune function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000;917:404–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex--linking immunity and metabolism. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2012;8(12):743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huston JM. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex: wandering on a new treatment paradigm for systemic inflammation and sepsis. Surgical infections. 2012;13(4):187–193. doi: 10.1089/sur.2012.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spengler ML, Kuropatwinski KK, Comas M, et al. Core circadian protein CLOCK is a positive regulator of NF-kappaB-mediated transcription. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(37):E2457–2465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206274109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arjona A, Sarkar DK. Circadian oscillations of clock genes, cytolytic factors, and cytokines in rat NK cells. Journal of immunology. 2005;174(12):7618–7624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chandra V, Mahajan S, Saini A, et al. Human IL10 gene repression by Rev-erbalpha ameliorates Mycobacterium tuberculosis clearance. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(15):10692–10702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.455915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandra V, Bhagyaraj E, Nanduri R, et al. NR1D1 ameliorates Mycobacterium tuberculosis clearance through regulation of autophagy. Autophagy. 2015;11(11):1987–1997. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1091140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woldt E, Sebti Y, Solt LA, et al. Rev-erb-alpha modulates skeletal muscle oxidative capacity by regulating mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy. Nat Med. 2013;19(8):1039–1046. doi: 10.1038/nm.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wunsch H, Gershengorn H, Mayer SA, et al. The effect of window rooms on critically ill patients admitted to intensive care with subarachnoid hemorrhages. Critical care. 2011;15(2):R81. doi: 10.1186/cc10075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kohn R, Harhay MO, Cooney E, et al. Do windows or natural views affect outcomes or costs among patients in ICUs? Critical care medicine. 2013;41(7):1645–1655. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318287f6cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verceles AC, Liu X, Terrin ML, et al. Ambient light levels and critical care outcomes. Journal of critical care. 2013;28(1):110e111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verceles AC, Silhan L, Terrin M, et al. Circadian rhythm disruption in severe sepsis: the effect of ambient light on urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin secretion. Intensive care medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2494-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernhofer EI, Higgins PA, Daly BJ, et al. Hospital lighting and its association with sleep, mood and pain in medical inpatients. Journal of advanced nursing. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jan.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thireau J, Zhang BL, Poisson D, et al. Heart rate variability in mice: a theoretical and practical guide. Experimental physiology. 2008;93(1):83–94. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malliani A, Pagani M, Lombardi F, et al. Cardiovascular neural regulation explored in the frequency domain. Circulation. 1991;84(2):482–492. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.2.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.