Abstract

In this study, we outline the synthesis of isatin–ferrocenyl chalcone and 1H-1,2,3-triazole-tethered isatin–ferrocene conjugates along with their antimicrobial evaluation against the human mucosal pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis. The introduction of a triazole ring among the synthesized conjugates improved the activity profiles with most of the compounds in the library, exhibiting 100% growth inhibition in a preliminary susceptibility screen at 100 μM. IC50 determination of the most potent compounds in the set revealed an inhibitory range between 2 and 13 μM. Normal flora microbiome are unaffected by these compounds, suggesting that these may be new chemical scaffolds for the discovery of new drugs against trichomonad infections.

Introduction

Trichomoniasis, a nonviral sexually transmitted disease caused by the protozoal pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis,1 mainly infects the urinary tract, vagina, and prostate.2 A recent survey indicated that there are about 276 million cases of trichomoniasis occurring globally of which 42.8 million cases occur in Africa (including sub-Saharan Africa)3 and 3.7 million in the United States,4 mostly affecting women under the age of 40 years.5,6 In most of the cases, the infection is asymptomatic,7 while the common symptoms might include malodorous vaginal discharge,8 dyspareunia, dysuria, lower abdominal pain, or vulvovaginal irritation.9 In certain cases, serious complications such as pelvic inflammation, cervical dysplasia, vaginitis, infertility, low birth weight infant, and preterm delivery may occur.10 Metronidazole and tinidazole are the only US-FDA drugs approved for the treatment of trichomoniasis.11 However, the emergence of drug resistance among the clinical isolates has prompted the need for the development of new and efficient structural entities with potentially low incidence of resistance.

Isatin is a promising class of biologically active scaffolds with tolerance to humans12 and a good platform for structure modification and derivatization. Isatin derivatives display a myriad of activities including anticancer,13 antidepressant,14 antifungal,15 anti-HIV,16 and anti-inflammatory properties.17 Isatin-β-thiosemicarbazones have been recently investigated for their selectivity to kill gp-over-expressing tumor cells in vitro.18 SU11248 (Sutent), a 5-fluoro-3-substituted isatin derivative, was approved by FDA in 2006 for the treatment of advanced renal carcinoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.19 Selective inhibitory activity of 5,7-dibromo-N-(p-trifluoromethylbenzyl)isatin against lymphoma and leukemic cancer cell lines over freshly isolated, nontransformed human peripheral blood lymphocytes has been disclosed recently.20 A recent report of Vine et al. has shown the potency of the N-alkyl isatin derivatives against the multidrug-resistant cell lines, viz., U937VbR and MES-SA/Dx5, and observed bioequivalent dose-dependent cytotoxicity to that of the parental control cell lines.21 In vitro selective inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase has also been reported for the N-substituted isatin–piperazine derivative.22 Many isatin derivatives have also been evaluated for their antimicrobial potential with isatin-β-thiosemicarbazones exhibiting minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.78 and 0.39 mg/L against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.23 Schiff base of 5-substituted isatin has also been found to be active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MIC = 6.25 μg/mL).24

Chalcones, an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl-linked framework,25 belong to the biologically active class of compounds with antileishmanial,26 antibacterial,27 antifungal,28 antitumor,29 antimalarial,30 antiviral,31 antitubercular,32 anti-invasive,33 antioxidant,34 anti-inflammatory,35 and antiplatelet properties.36 Naturally occurring Licochalcone A has shown promising antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis, S. aureus, and Micrococcus luteus.37 Chalcone-based conjugates have shown enormous biological potential with chalcone–thiazolidine–dione conjugates, which are proven to be 8 and 64 times more active than the reference drugs, norfloxacin (MIC = 1.0 μg/mL) and oxacillin (MIC = 0.5 μg/mL) against MRSA CCARM 3167 and 3506, respectively.38 Imidazole–chalcone conjugates were found to be active against Aspergillus fumigatus,(39) while ferrocenyl chalcones act as the HepG2 inhibitor and are nontoxic to human fibroblasts.40 Recently, metronidazole–chalcone conjugates have proven to be 4 times more potent than the standard drug metronidazole against T. vaginalis.41

One of the auspicious branches of bioorganometallic chemistry includes the synthesis of sandwich and half-sandwich complexes with important biological activity.42 Ferrocene represents a momentous scaffold in present day drug discovery paradigm because of its robustness, reactivity, redox properties, lipophilicity, and low cytotoxicity.43 Replacement of a purely organic component with ferrocene has shown to improve the biological potential of the target compounds as evidenced by ferrocenyl conjugates of commercial antiestrogen tamoxifen and antiandrogen nilutamide.44 Ferroquine is the most exemplary contribution of ferrocene to the improvement of antiplasmodial potential of chloroquine and is under clinical trials.45

Previous reports from our group have shown the synthesis of an isatin-based scaffold, viz., mono and bis-uracil–isatin, isatin–4-aminoquinoline, and isatin−β-lactam conjugates tethered via 1H-1,2,3-triazole and β-amino alcohol along with their preliminary in vitro evaluation against T. vaginalis.46 In continuation with our research efforts,47 the present study describes the synthesis of isatin–ferrocenyl chalcone and 1H-1,2,3-triazole-tethered isatin–ferrocene conjugates along with their antitrichomonad activities.

Results and Discussion

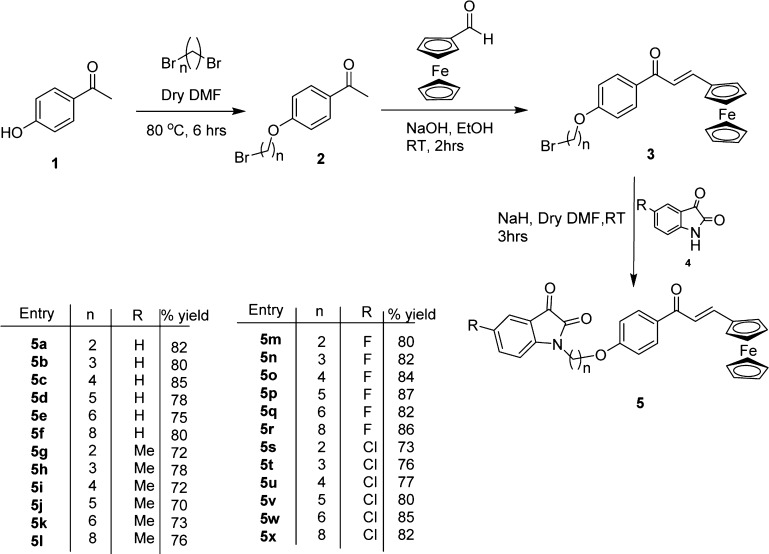

The methodology for the synthesis of isatin–ferrocenyl chalcone conjugates involved base-promoted N-alkylation of C-5-functionalized isatins with O-alkyl-bromo-ferrocenyl chalcones. The precursor, viz., O-alkyl-bromo-ferrocenyl chalcones 3, was prepared via an initial base-promoted O-alkylation of 4-hydroxy-acetophenone 1 with various dibromoalkanes at 60 °C for 8 h to afford the corresponding O-alkyl bromo-acetophenones 2. Subsequent aldol condensation of O-alkyl-bromoacetophenones with ferrocene carboxyaldehyde delivered the precursor O-alkyl-bromo-ferrocenyl chalcones in good to excellent yield (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 5a–x.

Sodium hydride-promoted reaction of C-5-substituted isatin with O-alkyl-bromo-ferrocenyl chalcone at room temperature (rt) for 3 h resulted in the isolation of desired isatin–ferrocenyl chalcone conjugates which were purified via flash chromatography using a mixture of ethyl acetate/hexane (20:80) as the eluent. The structure to the conjugates 5 was assigned on the basis of spectral data and analytical lines of evidence. Compound 5g, for example, exhibited a molecular ion peak at 519.3688 (m/z) in its high-resolution mass spectrum (HRMS). The salient features of its 1H NMR spectrum included the appearance of a multiplet at δ 4.16–4.19 (7H) corresponding to cyclopentadiene ring protons (5H) along with a methylene and singlets at δ 4.49 (2H) and 4.60 (2H) corresponding to ferrocene ring protons. The appearance of doublets at δ 7.12 (1H, J = 15.3 Hz) and 7.74 (1H, J = 15.3 Hz) confirmed the presence of trans-olefinic protons of ferrocenyl chalcones. The appearance of characteristics peaks at δ 161.40 and 188.03 ppm corresponding to isatin ring carbonyls along with the requisite number of carbons in 13C NMR spectra further corroborated the assigned structure.

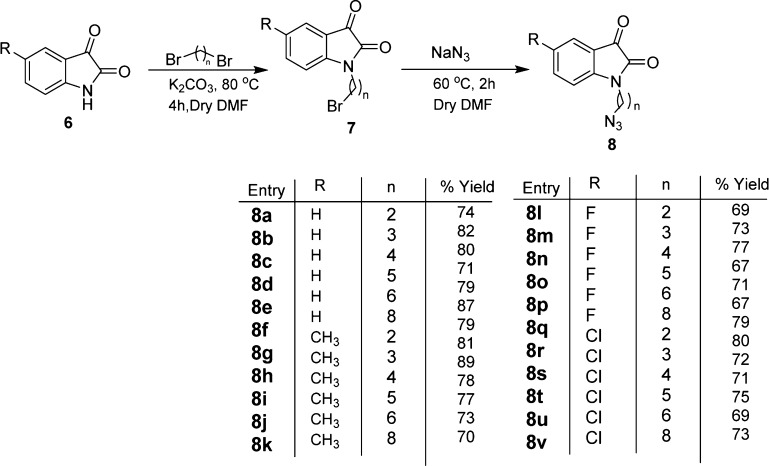

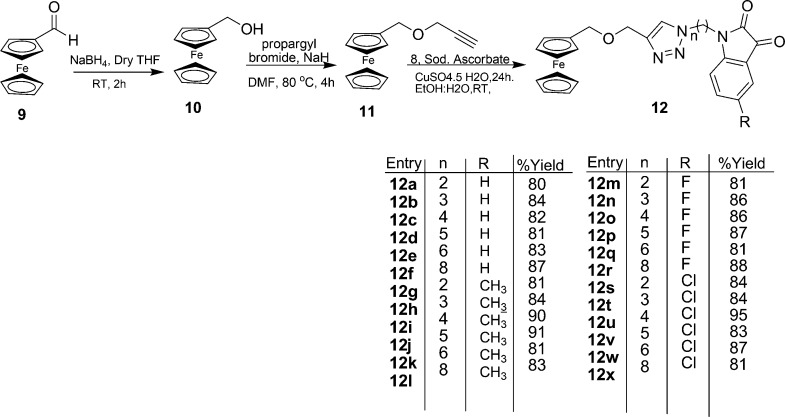

Synthetic methodology for the synthesis of 1H-1,2,3-triazole-tethered isatin–ferrocene conjugates 12 involved an initial base-promoted N-alkylation of isatin with dibromoalkanes at 80 °C with subsequent treatment with sodium azide to afford the corresponding N-alkylazidoisatins 8 (Scheme 2). The second precursor, viz., ((prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)methyl)ferrocene 11, was prepared via an initial reduction of ferrocene carboxyaldehyde 9 with NaBH4 in dry tetrahydrofuran to afford ferrocenyl-methanol 10, which was subsequently O-propargylated. Cu-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition of 8 with O-propargylated ferrocene methanol 11 led to the isolation of crude product, which was purified on silica gel chromatography (60:120) using methanol/chloroform (10:90) mixture as the eluent to yield 12 in good to excellent yields (Scheme 3). The structure to the compound was assigned on the basis of spectral studies and analytical evidence. For example, compound 12m exhibited a molecular ion peak at 504.0652 in its HRMS. Its 1H NMR spectrum showed the presence of a singlet at δ 4.14 corresponding to 5H (cyclopentadiene ring of ferrocene) along with singlets at δ 4.16 (2H) and δ 4.22 (2H) because of the presence of −OCH2 protons along with the characteristic singlet at δ 7.49 (1H) corresponding to the triazole ring proton. The appearance of absorption peaks at δ 68.5, 68.6, 68.8, and 82.7 in its 13C NMR spectrum corresponding to ferrocene ring carbons along with the presence of isatin ring carbonyl at δ 181.2 corroborated the assigned structure.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of N-Alkyl Azido Isatin.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Compounds 12a–x.

The synthesized compounds, viz., 5a–x and 12a–x, were evaluated for their inhibitory activity against T. vaginalis, and the results are summarized in Table 1. As evident, the activity profiles of synthesized scaffolds, viz., 5a–x, showed an interesting structure–activity relationship (SAR) with activity being dependent upon the nature of substituent at the C-5 position of the isatin ring as well as the length of the alkyl chain, introduced as a linker. Apparently, among conjugates with unsubstituted (R = H) isatin, the activities showed improvement with increase in the chain length from n = 2 to n = 4 as evidenced by 5a–c, while a further increase in the chain length reduced the activity. The introduction of a methyl substituent at the C-5 position of the isatin ring decreased the activities except in the case of 5g (n = 2) and 5i (n = 4). Introduction of electron-withdrawing substituents, viz., fluoro and chloro, in general improved the growth inhibition activity against T. vaginalis irrespective of the length of the alkyl chain linker. The conjugates, viz., 5o (R = F, n = 4) and 5s (R = Cl, n = 2), with an optimal combination of electron-withdrawing substituents at the C-5 position of the isatin ring and short alkyl chain length proved to be the most potent among the test compounds with 100% growth inhibition. Interestingly, the introduction of a 1H-1,2,3-triazole ring among isatin–ferrocene conjugates, 12a–x, substantially improved the activities with most of the synthesized conjugates exhibiting 100% growth inhibition. Analysis of SAR among 1H-1,2,3-triazole-tethered conjugates revealed the activity to be independent on the nature of the substituent present at the C-5 position of the isatin ring as well as the length of the alkyl chain used as the spacer except in cases where the octyl (n = 8) chain was used. The presence of the octyl chain length reduced the antitrichomonad activities as evident by conjugates 12f, 12l, 12r, and 12x exhibiting 64.70, 49.16, 52.70, and 35.38% growth inhibition, respectively.

Table 1. Antitrichomonad Activity of 5a–x and 12a–x at 100 μM against T. vaginalis.

| entry | % inhibition | entry | % inhibition | entry | % inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | 75.47 ± 12.23 | 5q | 86.37 ± 03.20 | 12i | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5b | 89.43 ± 04.66 | 5r | 93.79 ± 02.45 | 12j | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5c | 99.15 ± 01.46 | 5s | 100 ± 0 | 12k | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5d | 63.67 ± 11.32 | 5t | 99.51 ± 00.83 | 12l | 49.16 ± 16.91 |

| 5e | 83.07 ± 11.99 | 5u | 97.02 ± 01.21 | 12m | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5f | 81.43 ± 11.20 | 5v | 93.33 ± 03.86 | 12n | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5g | 95.83 ± 04.35 | 5w | 93.12 ± 07.15 | 12o | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5h | 82.83 ± 14.59 | 5x | 96.04 ± 02.44 | 12p | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5i | 90.88 ± 08.21 | 12a | 100 ± 0.0 | 12q | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5j | 78.77 ± 07.45 | 12b | 100 ± 0.0 | 12r | 52.70 ± 5.92 |

| 5k | 23.02 ± 13.36 | 12c | 100 ± 0.0 | 12s | 28.32 ± 20.55 |

| 5l | N.D | 12d | 100 ± 0.0 | 12t | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5m | 98.83 ± 01.05 | 12e | 100 ± 0.0 | 12u | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5n | 90.17 ± 04.26 | 12f | 64.70 ± 17.76 | 12v | 100 ± 0.0 |

| 5o | 100 ± 00 | 12g | 100 ± 0.0 | 12w | 52.20 ± 13.12 |

| 5p | 90.46 ± 01.81 | 12h | 100 ± 0.0 | 12x | 35.38 ± 13.97 |

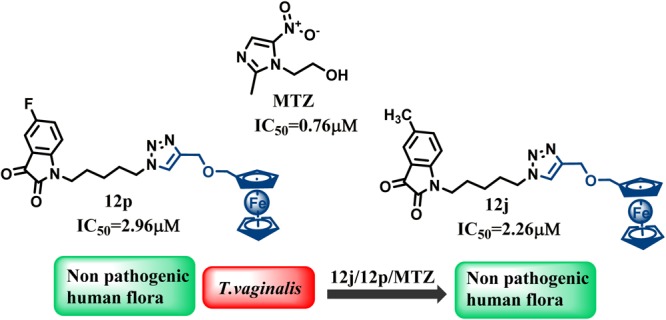

Most potent conjugates of the two series were further evaluated for their IC50 values and compared with metronidazole, the only FDA-approved drug used for the treatment of trichomoniasis (Table 2). As evident, although the conjugates were not as active as metronidazole, most of the compounds displayed low IC50 values. The conjugates, viz., 5w, 12c, 12d, 12j, and 12p, emerged as the most active conjugates with IC50 values of 7.13, 5.53, 5.82, 2.26, and 2.96 μM, respectively.

Table 2. IC50 Values of Compounds 5a–x and 12a–x.

| entry | IC50 (μM) | entry | IC50 (μM) | entry | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5b | 11.90 | 12c | 5.53 | 12m | 12.16 |

| 5o | 9.01 | 12d | 5.82 | 12n | 9.54 |

| 5t | 12.83 | 12e | 13.16 | 12p | 2.96 |

| 5v | 9.55 | 12g | 11.40 | 12t | 8.70 |

| 5w | 7.13 | 12h | 9.83 | 12u | 9.25 |

| 5x | 11.96 | 12j | 2.26 | 12v | 13.09 |

| 12a | 7.85 | 12k | 8.46 | MTZ | 0.76 |

To ascertain if the observed inhibitory effect of these compounds is due to their activity and not cytotoxicity, the conjugates were evaluated on normal human flora consisting of the nonpathogenic strains, Lactobacillus reuteri (ATCC 23272), Lactobacillus acidophilus (ATCC 43560), and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (ATCC 53103). No cytotoxic effects from any of these synthesized compounds were observed for any of the normal flora, which is suggestive of the fact that these compounds are antiparasitic.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a series of isatin–ferrocenyl chalcone and isatin–ferrocene conjugates were synthesized either via aliphatic nucleophilic substitution reaction or via azide–alkyne cycloaddition reaction, respectively, and were evaluated for their inhibitory activities against T. vaginalis. The lack of a chalcone moiety and the introduction of a 1H-1,2,3 triazole ring substantially improved the inhibitory activities with most of the conjugates exhibiting 100% growth inhibition at the preliminary screening concentration of 100 μM. The lack of dependence of activity upon the nature of substituent at the C-5 position of the isatin ring or the length of the alkyl chain introduced as the linker among 1H-1,2,3-triazole-tethered isatin–ferrocenes is suggestive of the fact that such conjugates may act as therapeutic templates for the design of new antitrichomonads.

Experimental Section

General Information

Melting points are uncorrected and determined via an open capillary method using a Veego Precision digital melting point (MP-D) apparatus. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 with Bruker AVANCE II (500 and 125 MHz) using tetramethylsilane as the internal standard. Chemical shift and coupling constant values are expressed in parts per million and hertz, respectively, while splitting patterns are designated as s: singlet, d: doublet, t: triplet, m: multiplet, dd: double doublet, ddd: doublet of a doublet of a doublet, and br: broad peak. Elemental analysis was performed on a Heraeus CHN-O rapid elemental analyzer, while mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker high-resolution mass spectrometer (microOTOF-QII). Column chromatography was carried out on a silica gel (60–120 mesh) with ethylacetate/hexane as the eluent.47e

Materials and Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assays

T. vaginalis strain G3 was cultured for 24 h at 37 °C. To perform the preliminary antimicrobial screen, the compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain stock concentrations of 100 μM; 5 μL aliquots of these suspensions were diluted in 5 mL of trypticase–yeast extract–maltose diamond’s media to obtain a final concentration of the compound of 100 μM. After 24 h of exposure to the compounds, any remaining motile cells were visualized and manually counted using a hemacytometer. Cell counts were normalized to the DMSO controls. These data sets were then transformed using GraphPad Prism software, and the sample size consists of four independent trials carried out on four different days (to account for possible variation in the parasite population). The IC50 values were determined by titration assays of increasing concentrations of each compound, usually within a range of 5–40 μM, by a regression analysis using Prism software from GraphPad. The calculated IC50 values of the compounds were then confirmed by using the same assay described previously.

Cytotoxicity Assay for Normal Flora Microbiota

Cultures of nonpathogenic bacteria such as L. reuteri (ATCC 23272), L. acidophilus (ATCC 43560), and L. rhamnosus (ATCC 53103), known to comprise the human mucosal microbiome, were grown in Lactobacilli MRS media at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. Escherichia coli K12 MG1655 (nonpathogenic) was cultured in Luria broth at 37 °C aerobically. Stock solutions (100 μM) of synthesized compounds and vehicle control DMSO were diluted to 100 μM in media to afford working dilutions. Empty BDL-sensi disks (6 mm) were incubated in the working dilutions at rt for 20 min. Streaked agar plates of chosen bacteria were incubated with disks containing the vehicle control, compounds, or various antibiotic disks [levofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), and gentamicin (120 μg)] and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Sensitivity to the vehicle control, compounds, and antibiotics was determined via the measurement of zones of inhibition around each disk in millimeter. All organisms were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).47c

Acknowledgments

V.K. acknowledges the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi (grant no. 02IJ0293)/17/EMR-I) for providing financial assistance. K.M.L. was supported by the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of the Pacific. C.T. and L.W.C. were funded by the U. S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (National Program 108, Project CRIS 5325-42000-049-00D). Financial assistance from University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi, India, under UGC-JRF Fellowship (A.S.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00553.

Scanned (1H, 13C) NMR spectra for the compounds, viz., 5c, 5d, 5g, 5n, 5p, 5s, 5t, 5u, 5v, 12a, 12c, 12e, 12f, 12j, 12k, 12o, 12p, 12r, 12s, 12t, and 12u (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Satterwhite C. L.; Torrone E.; Meites E.; Dunne E. F.; Mahajan R.; Ocfemia M. C. B.; Su J.; Xu F.; Weinstock H. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013, 40, 187–193. 10.1097/olq.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusdian G.; Gould S. B. The biology of Trichomonas vaginalis in the light of urogenital tract infection. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2014, 198, 92–99. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger P.; Adamski A. Trichomoniasis and HIV interactions: a review. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2013, 89, 426–433. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-051005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterwhite C. L.; Torrone E.; Meites E.; Dunne E. F.; Mahajan R.; Ocfemia M. C. B.; Su J.; Xu F.; Weinstock H. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013, 40, 187–193. 10.1097/olq.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginocchio C. C.; Chapin K.; Smith J. S.; Aslanzadeh J.; Snook J.; Hill C. S.; Gaydos C. A. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis and Coinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States as Determined by the Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis Nucleic Acid Amplification Assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 2601–2608. 10.1128/jcm.00748-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavedzenge S. N.; Van der Pol B.; Cheng H.; Montgomery E. T.; Blanchard K.; de Bruyn G.; Ramjee G.; Van der Straten A. Epidemiological Synergy of Trichomonas vaginalis and HIV in Zimbabwean and South African Women. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2010, 37, 460–465. 10.1097/olq.0b013e3181cfcc4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsworth J. E.; Ratner J. A.; Peipert J. F. Trichomoniasis and other sexually transmitted infections: results from the 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2009, 36, 738–744. 10.1097/olq.0b013e3181b38a4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravaee R.; Ebadi P.; Hatam G.; Vafafar A.; Seno M. M. G. Synthetic siRNAs effectively target cystein protease 12 and α-actinin transcripts in Trichomonas vaginalis. Exp. Parasitol. 2015, 157, 30–34. 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J. S.; Gaydos C. A.; Witter F. Trichomonas vaginalis vaginitis in obstetrics and gynecology practice. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2013, 68, 43–50. 10.1097/ogx.0b013e318279fb7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatski M.; Kissinger P. Observation of probable persistent, undetected Trichomonas vaginalis infection among HIV-positive women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 114–115. 10.1086/653443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel K. A.; Workowski K. A. Trichomoniasis: challenges to appropriate management. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, S123–S129. 10.1086/511425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.; Chen M.; Qiu J.; Xie Z.; Cao A. Synthesis, in vitro a-glucosidase inhibitory activity and docking studies of novel chromone-isatin derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 113–116. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim H. S.; Abou-Seri S. M.; Tanc M.; Elaasser M. M.; Abdel-Aziz H. A.; Supuran C. T. Isatin-pyrazole benzenesulfonamide hybrids potently inhibit tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase isoforms IX and XII. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 103, 583–593. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.-M.; Guo H.; Li Z.-S.; Song F.-H.; Wang W.-M.; Dai H.-Q.; Zhang L.-X.; Wang J.-G. Synthesis and evaluation of isatin-β-thiosemicarbazones as novel agents against antibiotic-resistant Gram-positive bacterial species. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 101, 419–430. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanh N. D.; Giang N. T. K.; Quyen T. H.; Huong D. T.; Toan V. N. Synthesis and evaluation of in vivo antioxidant, in vitro antibacterial, MRSA and antifungal activity of novel substituted isatin N-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl)thiosemicarbazones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 123, 532–543. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal T. R.; Anand B.; Yogeeswari P.; Sriram D. Synthesis and evaluation of anti-HIV activity of isatin beta-thiosemicarbazone derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4451–4455. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.; Zhang S.; Gao C.; Fan J.; Zhao F.; Lv Z.-S.; Feng L.-S. Isatin hybrids and their anti-tuberculosis activity. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 159–167. 10.1016/j.cclet.2016.07.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. D.; Brimacombe K. R.; Varonka M. S.; Pluchino K. M.; Monda J. K.; Li J.; Walsh M. J.; Boxer M. B.; Warren T. H.; Fales H. M.; Gottesman M. M. Synthesis and Structure–Activity Evaluation of Isatin-β-thiosemicarbazones with Improved Selective Activity toward Multidrug-Resistant Cells Expressing P-Glycoprotein. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 5878–5889. 10.1021/jm2006047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Y.-O.; Zhao H.-Y.; Wang J.; Liu H.; Gao M.-L.; Zhou Y.; Han K.-L.; Fan Z.-C.; Zhang Y.-M.; Sun H.; Yu P. Synthesis and anti-cancer activity evaluation of 5-(2-carboxyethenyl)-isatin derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 112, 145–156. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vine K. L.; Locke J. M.; Ranson M.; Pyne S. G.; Bremner J. B. An Investigation into the Cytotoxicity and Mode of Action of Some Novel N-Alkyl-Substituted Isatins. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 5109–5117. 10.1021/jm0704189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vine K. L.; Belfiore L.; Jones L.; Locke J. M.; Wade S.; Minaei E.; Ranson M. N-alkylated isatins evade P-gp mediated efflux and retain potency in MDR cancer cell lines. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00060 10.1016/j.heliyon.2015.e00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakravan P.; Kashanian S.; Khodaei M. M.; Harding F. J. Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of isatin and its derivatives: from structure to activity. Pharmacol. Rep. 2013, 65, 313–335. 10.1016/s1734-1140(13)71007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.-M.; Guo H.; Li Z.-S.; Song F.-H.; Wang W.-M.; Dai H.-Q.; Zhang L.-X.; Wang J.-G. Synthesis and evaluation of isatin-β-thiosemicarbazones as novel agents against antibiotic-resistant Gram-positive bacterial species. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 101, 419–430. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani K. H. M. E.; Hashemi M.; Hassan M.; Kobarfard F.; Mohebbi S. Synthesis, antiplatelet activity and cytotoxicity assessment of indole-based hydrazone derivatives. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 14, 1077–1086. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu N. K.; Balbhadra S. S.; Choudhary J.; Kohli D. V. Exploring pharmacological significance of chalcone scaffold: a review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 209–225. 10.2174/092986712803414132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mello T. F. P.; Bitencourt H. R.; Pedroso R. B.; Aristides S. M. A.; Lonardoni M. V. C.; Silveira T. G. V. Leishmanicidal activity of synthetic chalcones in Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. Exp. Parasitol. 2014, 136, 27–34. 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. L.; Xu Y. J.; Go M. L. Functionalized chalcones with basic functionalities have antibacterial activity against drug sensitiveStaphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 43, 1681–1687. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P.; Anand A.; Kumar V. Recent developments in biological activities of chalcones: A mini review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 85, 758–777. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go M.; Wu X.; Liu X. Chalcones: an update on cytotoxic and chemoprotective properties. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 483–499. 10.2174/0929867053363153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans R. H.; Guantai E. M.; Lategan C.; Smith P. J.; Wan B.; Franzblau S. G.; Gut J.; Rosenthal P. J.; Chibale K. Synthesis, antimalarial and antitubercular activity of acetylenic chalcones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 942–944. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheenpracha S.; Karalai C.; Ponglimanont C.; Subhadhirasakul S.; Tewtrakul S. Anti-HIV-1 protease activity of compounds from Boesenbergia pandurata. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 1710–1714. 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaradia L. D.; Mascarello A.; Purificação M.; Vernal J.; Cordeiro M. N. S.; Zenteno M. E.; Villarino A.; Nunes R. J.; Yunes R. A.; Terenzi H. Synthetic chalcones as efficient inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase PtpA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 6227–6230. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G.; Arora A.; Mangat S. S.; Rani S.; Kaur H.; Goyal K.; Sehgal R.; Maurya I. K.; Tewari R.; Choquesillo-Lazarte D.; Sahoo S.; Kaur N. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of chalconyl blended triazole allied organosilatranes as giardicidal and trichomonacidal agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 108, 287–300. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S.; Barbic M.; Jürgenliemk G.; Heilmann J. Synthesis, cytotoxicity, anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activity of chalcones and influence of A-ring modifications on the pharmacological effect. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 2206–2213. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandgar B. P.; Gawande S. S.; Bodade R. G.; Totre J. V.; Khobragade C. N. Synthesis and biological evaluation of simple methoxylated chalcones as anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 1364–1370. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.-M.; Jin H.-S.; Sun L.-P.; Piao H.-R.; Quan Z.-S. Synthesis and evaluation of antiplatelet activity of trihydroxychalcone derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 5027–5029. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadigoppula N.; Korthikunta V.; Gupta S.; Kancharla P.; Khaliq T.; Soni A.; Srivastava R. K.; Srivastava K.; Puri S. K.; Raju K. S. R.; Wahajuddin; Sijwali P. S.; Kumar V.; Mohammad I. S. Synthesis and Insight into the Structure–Activity Relationships of Chalcones as Antimalarial Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 31–45. 10.1021/jm300588j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-F.; Zheng C.-J.; Sun L.-P.; Liu X.-K.; Piao H.-R. Synthesis of new chalcone derivatives bearing 2,4-thiazolidinedione and benzoic acid moieties as potential anti-bacterial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 3469–3473. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain T.; Siddiqui H. L.; Zia-ur-Rehman M.; Yasinzai M. M.; Parvez M. Anti-oxidant, anti-fungal and anti-leishmanial activities of novel 3-[4-(1H-imidazole-1-yl) phenyl]prop-2-en-1-ones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 4654–4660. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferle-Vidović A.; Poljak-Blaži M.; Rapić V.; Škare D. Ferrocene and fero-sorbitol-citrate (FSC): potential anticancer drugs. Cancer Biother.Radiopharm. 2000, 15, 617–624. 10.1089/cbr.2000.15.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthwal A.; Rajesh U. C.; Rawat M. S. M.; Kushwaha B.; Maikhuri J. P.; Sharma V. L.; Gupta G.; Rawat D. S. Novel metronidazole–chalcone conjugates with potential to counter drug resistance in Trichomonas vaginalis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 79, 89–94. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Adams R. D. Foreword to the ISBOMC’08 special issue. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 801. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Stringer T.; Seldon R.; Liu N.; Warner D. F.; Tam C.; Cheng L. W.; Land K. M.; Smith P. J.; Chibale K.; Smith G. S. Antimicrobial activity of organometallic isonicotinyl and pyrazinyl ferrocenyl-derived complexes. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 9875. 10.1039/c7dt01952a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staveren D. R.; Metzler-Nolte N. Bioorganometallic Chemistry of Ferrocene. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 5931–5986. 10.1021/cr0101510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A.; Vessières A.; Hillard E. A.; Top S.; Pigeon P.; Jaouen G. Ferrocifens and ferrocifenols as new potential weapons against breast cancer. Chimia 2007, 61, 716–724. 10.2533/chimia.2007.716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Pigeon P.; Top S.; Zekri O.; Hillard E. A.; Vessières A.; Plamont M.-A.; Buriez O.; Labbé E.; Huché M.; Boutamine S.; Amatore C.; Jaouen G. The replacement of a phenol group by an aniline or acetanilide group enhances the cytotoxicity of 2-ferrocenyl-1,1-diphenyl-but-l-ene compounds against breast cancer cells. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 895. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2008.11.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Gormen M.; Plażuk D.; Pigeon P.; Hillard E. A.; Plamont M.-A.; Top S.; Vessières A.; Jaouen G. Comparative toxicity of [3]ferrocenophane and ferrocene moieties on breast cancer cells. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 118. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.10.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kumar K.; Liu N.; Yang D.; Na D.; Thompson J.; Wrischnik L. A.; Land K. M.; Kumar V. Synthesis and antiprotozoal activity of mono- and bis-uracil isatin conjugates against the human pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis. Biomed. Chem. 2015, 23, 5190–5197. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nisha; Kumar K.; Bhargava G.; Land K. M.; Chang K.-H.; Arora R.; Sen S.; Kumar V. N-Propargylated isatin-Mannich mono- and bis-adducts: Synthesis and preliminary analysis of in vitro activity against Tritrichomonas foetus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 74, 657. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Singh A.; Saha S. T.; Perumal S.; Kaur M.; Kumar V. Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition En Route to 1H-1,2,3-Triazole-Tethered Isatin–Ferrocene, Ferrocenylmethoxy-Isatin, and Isatin-Ferrocenylchalcone Conjugates: Synthesis and Antiproliferative Evaluation. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 1263–1268. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kumar S.; Gu L.; Palma G.; Kaur M.; Singh-Pillay A.; Singh P.; Kumar V. Design, synthesis, anti-proliferative evaluation and docking studies of 1H-1,2,3-triazole tethered ospemifene–isatin conjugates as selective estrogen receptor modulators. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 3703–3713. 10.1039/c7nj04964a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Singh A.; Nisha N.; Bains T.; Hahn H. J.; Liu N.; Tam C.; Cheng L. W.; Kim J.; Debnath A.; Land K. M.; Kumar V. Design, synthesis and preliminary antimicrobial evaluation of N-alkyl chain-tethered C-5 functionalized bis-isatins. MedChemComm 2017, 8, 1982–1992. 10.1039/c7md00434f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Rani A.; Singh A.; Gut J.; Rosenthal P. J.; Kumar V. Microwave-promoted facile access to 4-aminoquinoline-phthalimides: Synthesis and anti-plasmodial evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 14, 150–156. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Singh A.; Gut J.; Rosenthal P. J.; Kumar V. 4-aminoquinoline-ferrocenyl-chalcone conjugates: Synthesis and anti-plasmodial evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 125, 269–277. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.