Abstract

Because of their potent cytotoxic activity, members of the auristatin family (synthetic analogues of the naturally occurring dolastatin 10) have remained a target of significant research, most notably in the context of antibody drug conjugate payloads. Typically, modifications of the backbone scaffold of dolastatin 10 have focused on variations of the N-terminal (P1) and C-terminal (P5) subunits. Scant attention has been paid thus far to the P4 subunit in the scientific literature. In this paper, we introduce an azide functional group at the P4 subunit, resulting in potent cytotoxic activity seen in vitro. Another highly active compound in this study contained azide functional groups in both the P2 and P4 subunits and required dolavaline as the P1 subunit and a phenylalanine as the P5 subunit. Furthermore, these two azide groups served not only as modifiers of cytotoxicity but also as handles for linker attachment or as a tether for use in the synthesis of a macrocyclic analogue.

Introduction

Naturally occurring peptides have been shown to be potent antibiotic agents, causing cell death at picomolar or low nanomolar concentrations.1 Tubulin-binding natural products, especially vinca domain inhibitors, have played an important role in cancer research for decades.2−5 One of them, the natural product dolastatin 10 (1), isolated from the sea hare Dolabella auricularia, was discovered by Pettit et al.6 Dolastatin 10 (1) and its synthetic analogues (termed “auristatins”) (i.e., TZT-1027) demonstrated extraordinary cytotoxicity with sub-nanomolar activity in vitro toward a variety of cancer cell lines. However, when tested in the clinic, no significant activity was observed at the maximum tolerated dose.7−19 Given these clinical results, and the likelihood that the lack of activity was due to the potency/toxicity of this class of compound as a small-molecule chemotherapeutic, many research groups have engaged in studies of synthetic dolastatin 10 derivatives as cytotoxic payloads in targeted therapies. The auristatin molecular class has found considerable application within the field of antibody drug conjugates (ADCs), with the goal to widen a clinically relevant therapeutic window. One targeted therapy approach has used an auristatin E (2a) derivative, monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE, 2b), as the active payload in ADCETRIS20 (Figure 1B). Other auristatin family members are under investigation as payloads in a variety of ADCs currently in clinical trials.21

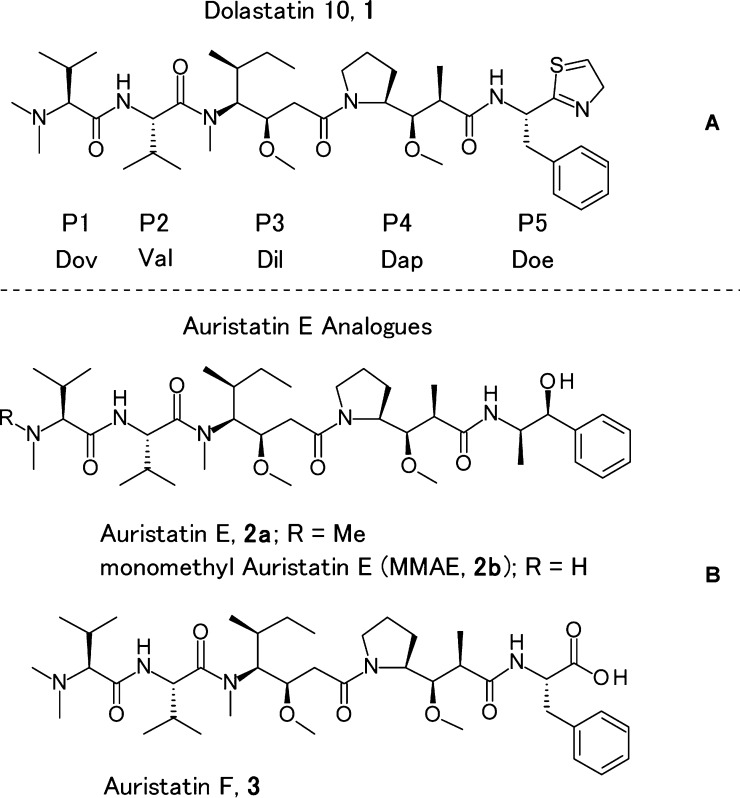

Figure 1.

Structure of dolastatin 10 (1) (panel A) and auristatin analogues (2a, 2b, and 3) (panel B).

Dolastatin 10 (1) consists of four amino acid building blocks, dolavaline (Dov, P1), valine (Val, P2), dolaisoleuine (Dil, P3), and dolaproine (Dap, P4), and the C-terminal amine dolaphenine (Doe, P5) (Figure 1A). Figure 1B illustrates the structure of auristatin analogues.22,23 Many research groups have studied linear dolastatin 10 analogues and this area has been extensively reviewed.23 In particular, numerous N-terminal P1 subunit and C-terminal P5 subunit modifications were performed by Pettit et al., Miyazaki et al., and other groups to investigate their structure–activity relationship (SAR).24−26 In our recent report, we investigated the incorporation of heterocycles into the P5 subunit.27 These P5 heterocycle modifications generated ADCs with more hydrophilic character and lower aggregation.

Modification of the core central peptides (P2–P4 subunits) has not been as extensively investigated because it has been reported that changes in these subunits result in attenuated compound potency.23 In terms of the P2 subunit, substitution of the natural valine residue with leucine or isoleucine is reported26 and our group recently reported SAR results for analogues containing heteroatoms and other non-natural amino acids in the P2 position.28 In contrast, regarding the P4 subunit, there are a few reports of analogues with mannose- and glucose-derived sugar amino acids as replacements for the Dap portion by Gajula et al.29,30 and also hydroxyl, methoxy, and amino substituents on the pyrrolidine are described by Park et al.31

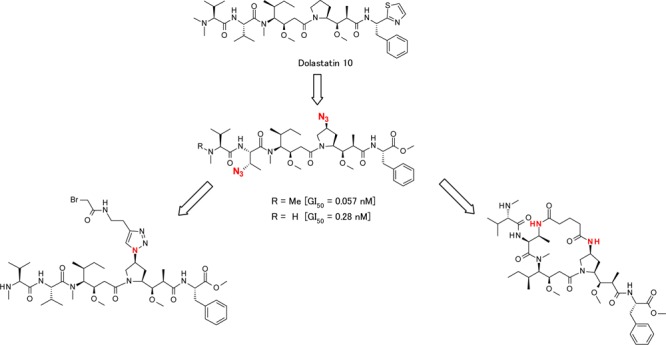

Discussed here are new linear dolastatin 10 analogues with an azide substituted P4 central amino acid and also in combination with P2 azide substitution. These azide substitutions show changes in cytotoxicity and can serve as a handle for linker attachment or a tether for use in the synthesis of novel macrocyclic dolastatin 10 analogues (Figures 2 and 3).

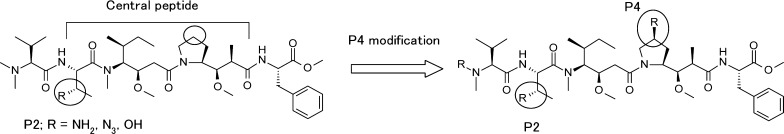

Figure 2.

Modified central peptide strategy; structure of P2-modified and P4-modified dolastatin 10.

Figure 3.

Critical binding spots of PF-06380101, 4 to tubulin (panel A), and design of macrocyclic analogue 19 (panel B).

Results and Discussion

In our previous studies, we reported SAR results for auristatins containing specific P2 side chain modifications. We showed that P2-modified analogues, with the P2 units as 3S-amino-2S-aminobutyric acid (Abu (3-NH2)), 3S-azide-2S-aminobutyric acid (Abu (3-N3)), and 3S-hydroxyl-2S-aminobutyric acid (Abu (3-OH)), could display high in vitro cytotoxic activity (Figure 2).28 Building from this previous work, we investigated whether central P4-modified analogues containing heteroatom substituents on the pyrrolidine ring retained cytotoxic potency with and without P2 heteroatom modifications. In addition, we examined the potency associated with a constrained macrocyclic dolastatin 10 analogue. The published PF-06380101 tubulin crystal data revealed a critical hydrogen bond network between Asp β177 and the amide carbonyl of Phe α351 with the protonated amino group of P1, a bifocal interaction of the N-2 valine with Asn α329, and also between the backbone amide of Tyr β222 with the terminal carbonyl groups of Dap and Doe (Figure 3A).32 Moreover, the cis Val-Dil amide bond and trans Dil-Dap amide bond geometries were revealed in a cocrystal structure with tubulin (Figure 3A).32,33 We presumed that a tether between the P2 and P4 subunits enables the formation of a macrocyclic structure that could force cis/trans geometry across these relevant bonds (Figure 3B).

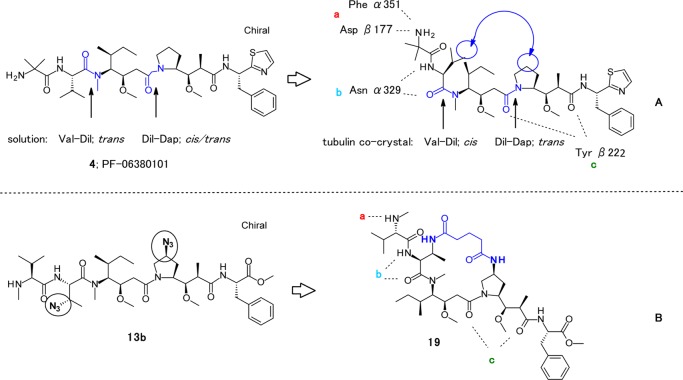

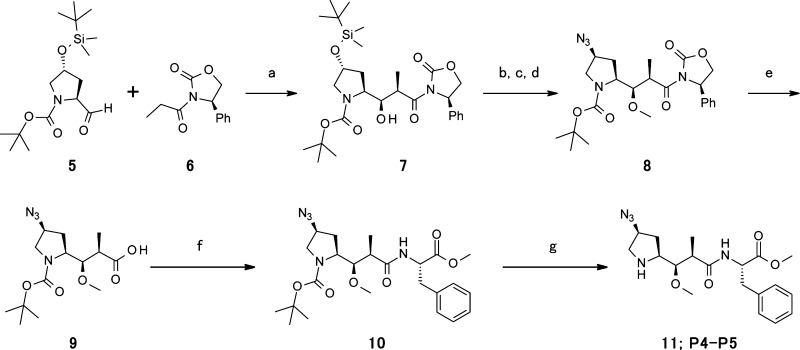

The synthesis route of the azide-containing dipeptide intermediate is shown in Scheme 1. syn-Aldol product 7 was prepared from chiral proline aldehyde 5 and the boron enolate of chiral (R)-oxazolidinone 6 with moderate yield.31,34 After methylation and tert-butyl dimethyl silyl deprotection, introduction of the azide group was performed by Mitsunobu-type chemistry using diphenylphosphoryl azide (DPPA) and diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD) to provide Boc-Dap (4-N3)-phenyloxazolidinone 8. Hydrolysis of the chiral auxiliary unit on compound 8 was accomplished using LiOH and H2O2, which led to the desired carboxylic acid Boc-Dap (4-N3)-OH 9. Boc-dipeptide 10 was formed using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) and 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt) to couple compound 9 with phenylalanine methyl ester (H-Phe-OMe). HCl-mediated Boc deprotection yielded compound 11.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the P4-Modified Dipeptide 11 (P4–P5).

(a) n-Bu2BOTf, iPrNEt2, CH2Cl2, −78 to 0 °C. (b) Me3OBF4, proton sponge, molecular sieves, 4 Å, EtOH, 0 °C to rt. (c) HF-Py, THF, 0 °C. (d) DPPA, DIAD, PPh3, THF, 0 °C to rt. (e) H2O2, LiOH, H2O, THF, 0 °C. (f) H-Phe-OMe, EDCI, HOBt, Et3N, CH2Cl2. (g) 4 M HCl–dioxane.

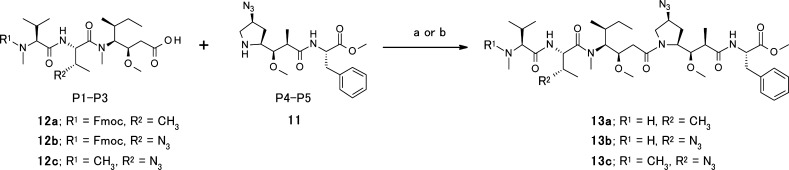

Convergent syntheses of new linear dolastatin analogues are shown in Scheme 2. The P4–P5 intermediate, 11, and the separately prepared P1–P3 intermediates, 12a–c, were coupled in a modular manner to yield final dolastatin analogues 13a, 13b, and 13c.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of New Dolastatin Analogues 13a, 13b, and 13c.

(a) EDCI, HOBt, Et3N, N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc). (b) EDCI, HOBt, Et3N, DMAc, then Et2NH.

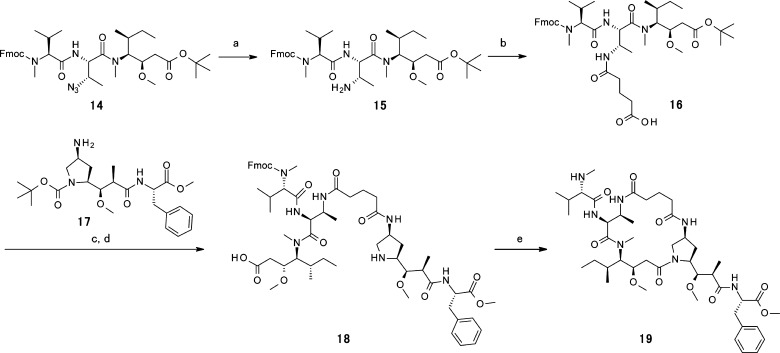

The synthesis of a macrocyclic dolastatin derivative is shown in Scheme 3. The reduction of the azide group of the P1–P3 intermediate 14, followed by the ring-opening reaction with glutaric anhydride, provided carboxylic intermediate 16. The coupling reaction of carboxylic acid 16 and amine 17 followed by the deprotection of the Boc group and tert-Bu ester hydrolysis provided macrocyclic precursor 18. Macrocyclization was achieved through reaction using the Mukaiyama condensation reagent, 2-chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide (CMPI), under high dilution conditions (0.00014 M). Finally, the deprotection of the Fmoc group using Et2NH gave the desired macrocyclic analogue 19 in high yield (c–e, three steps; 61%).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of New Macrocyclic Dolastatin Analogue 19.

(a) H2, Pd/C, EtOH. (b) Glutaric anhydride, DMAc, 60 °C. (c) 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate (HATU), iPrNEt2, DMAc. (d) 4 M HCl–dioxane. (e) CMPI, iPrNEt2, EtOAc, then Et2NH.

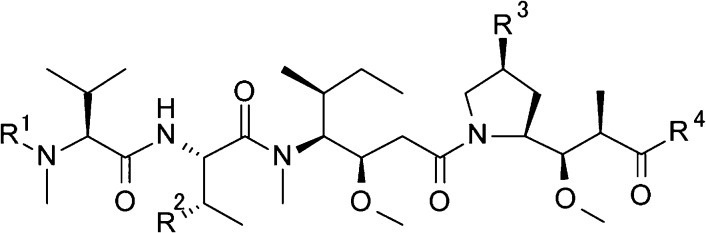

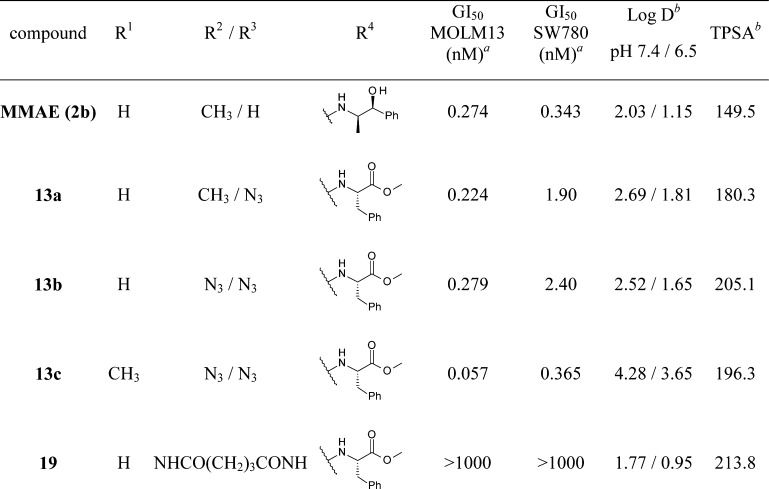

Table 1 highlights the in vitro potency of each compound with respective P1, P2, and P4 unit modifications. Each compound was evaluated in an in vitro cell proliferation assay using an acute myeloid leukemia cell line (MOLM13) and a bladder cancer cell line (SW780) (see the Supporting Information). Compounds 2b, 13a, 13b, and 13c demonstrated similar GI50 values (within 1 log) in both MOLM13 and SW780 cell lines; however, the SW780 cell line appeared less sensitive overall in this experiment. In our previous studies evaluating P2 modifications,28 we determined that modification of the P2 side chain required a specific aromatic P5 subunit (containing an ester or amide functional group), which did not follow previously reported SAR trends for P2 valine-based auristatins.23 On the basis of these results, we held the aromatic P5 ester units unchanged while examining the SAR of P4 azide introduction. Compound 13a, containing an azide only in the P4 central peptide, demonstrated a similar activity in vitro when compared to MMAE (2b) in the MOLM13 cell line. Next, we explored combinations of both P4 and P2 azide modifications. Compound 13b, with P2 Abu (3-N3) and a MeVal unit in the P1 position, showed a similar GI50 value in the MOLM13 cell line compared to 13a (0.279 and 0.224 nM, respectively). Interestingly, compound 13c, with P2 and P4 azide modifications and Dov in the P1 position, showed enhanced cytotoxic activity (GI50 = 0.057 nM) compared to compound 13b. One possible explanation of the cytotoxicity is that analogue 13c, the pentapeptide containing two azide groups in the P2 and P4 positions, could take a more favorable conformation by electric and steric effects arising from the azide groups.35,36 To date, it was known that structural changes in the dolastatin Dap P4 subunit did not significantly compromise the cytotoxic potency, even though the P1 unit was Dov.29−31 However, our research revealed that the modification to the Dap moiety has shown to be beneficial in improving the potency. In contrast, the macrocyclic analogue 19 showed a low in vitro potency, and these differences in cytotoxicity may be explained by differences in cellular membrane permeability reflected in the compound calculated hydrophilicity measurements, log D pH 7.4/6.5 and topological polar surface area (TPSA) (Table 1). This inability for some molecules to cross the cell membrane changes when they are attached to an antibody as antibodies can transport the attached molecule across the cell membrane and have the ability to release the payload inside the cell. This has been shown for MMAF (monomethyl auristatin F)-derived ADCs, which are highly potent despite the low membrane permeability of MMAF (Figure 1).28,37 Further investigation is needed to determine whether an ADC composed of a drug linker prepared from compound 19 demonstrates cytotoxicity. Additionally, 1H NMR data gathered for macrocyclic analogue 19 did not show cis/trans amide signals found in the linear compound 13b (see the Supporting Information), indicating a constrained amide bond geometry and relative enhancement of rigidity. Given the more rigid structure of the macrocyclic analogue compared to the linear analogue, it may also be possible that macrocyclic analogue 19 was forced into a less favorable conformation by the relatively rigid structure. Studies are ongoing to elucidate a cocrystal structure of tubulin with compound 13a and with compound 19 to reveal the conformation of the Val-Dil and Dil-Dap amide bond geometries and the binding mode with tubulin to enable further design optimizations and investigation of tethers for preparation of potent macrocyclic dolastatin 10 analogues.

Table 1. Derivatives of P4 Central Modification with GI50 Values and Properties.

Results are the average of two independent triplicate runs with compound purity above >90%.

log D and TPSA values were calculated with ACD/PhysChem Batch (version 12.01).

Through this work, we have also confirmed that azide groups introduced into the P2 and P4 subunits demonstrate the possibility for serving as handles for linker attachment.

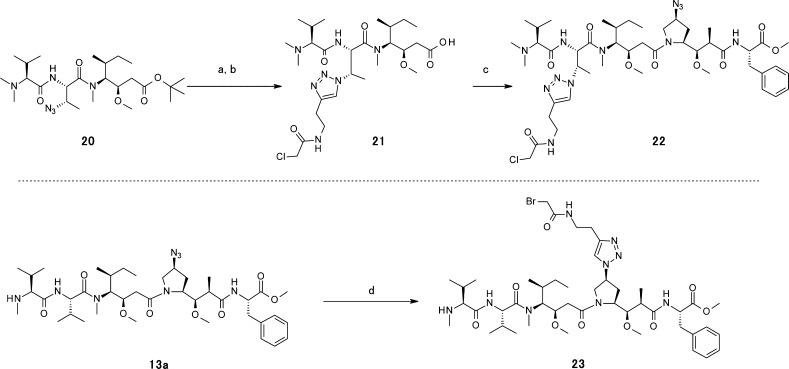

The synthesis of drug linkers using a P2 or P4 linkage is shown in Scheme 4. The click reaction38 of compound 20 and N-(but-3-yn-1-yl)-2-chloroacetamide proceeded smoothly to yield compound 21. Deprotection of the Boc group and subsequent coupling to the P4–P5 dimer 11 yielded the desired drug linker 22. Payload 13a, containing the P4 azide group, gave drug linker 23 directly using the click reaction with N-(but-3-yn-1-yl)-2-bromoacetamide. These examples, using noncleavable linkers, suggest that payloads that incorporate azide groups could serve as linker attachment sites for other noncleavable or cleavable linkers. Thus, compounds 13a–c are promising payloads for preparation of novel drug linkers at the P2 or P4 position.

Scheme 4. Preparation of Drug Linkers 22 and 23 with P2 or P4 Linkage.

(a) N-(But-3-yn-1-yl)-2-chloroacetamide, CuBr, iPrNEt2, dimethylformamide (DMF). (b) 4 M HCl–dioxane. (c) EDCI, HOBt, Et3N, DMAc. (d) N-(But-3-yn-1-yl)-2-bromoacetamide, CuBr, iPrNEt2, DMF.

Conclusions

We revealed that the modification of the Dap unit has proven to be beneficial in improving potency. Compounds with a P4-modified azide group on the pyrrolidine ring demonstrate cytotoxic activity in vitro. In particular, the dolastatin 10 analogues with azide modifications on both P2 and P4 showed enhanced cytotoxic activity (GI50 = 0.057 nM) when compared to MMAE. On the contrary, the macrocyclic analogue showed poor potency. Possible explanations of these cytotoxicity values were due to hydrophilicity and conformation of these pentapeptides. Additional work is now under way to further reveal the amide bond geometries and the binding mode of these compounds. We also demonstrated that the analogue containing an azide group can serve as sites of linker attachment in the preparation of ADCs.

Experimental Section

Synthesis strategies for assembling the compounds described herein as well as the purification strategies and analytical methods employed mirror a recent report by our research group.28

General Methods

NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker AV 500, 400, or 300 MHz spectrometer at 25 °C. All NMR spectra were referenced to the DMSO-d6 residual solvent peak (1H: 2.50 ppm; 13C: 39.5 ppm).

High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRESIMS) samples were directly injected into a Dionex 3000-Orbitrap Velos LC-MS.

Flash column chromatography was carried out using prepacked Yamazen Universal columns on a Yamazen purification system. Preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using a 5–95% gradient of acetonitrile/0.05% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) mixture over 13 min unless another column or solvent system is noted. Preparative HPLC-purified compounds were assumed to be salts containing one molecule of TFA.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) data was acquired using an Acquity UPLC BEH C8 1.7 μm 2.1 × 50 mm2 column, 40 °C. 0–0.5 min: isocratic 85:5:10 H2O/MeCN/0.5% TFA in H2O; 0.5–1.6 min: linear gradient 85:5:10 H2O/MeCN/0.5% TFA in H2O to 98:2 MeCN/0.5% TFA in H2O; 1.60–1.9 min linear gradient 98:2 MeCN/0.5% TFA in H2O to 85:5:10 H2O/MeCN/0.5% TFA in H2O; 1.9–2.0 isocratic 85:5:10 H2O/MeCN/0.5% TFA in H2O.28

Materials

All solvents and reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification.

Synthetic Procedures

Reactions were typically carried out at ambient room temperature (rt) with exposure to air, unless otherwise noted.

Compound 8

To a stirred solution of (4R)-4-phenyl-3-propanoyl-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (1.33 g, 6.06 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (36 mL) that was cooled to 0 °C, n-Bu2BOTf (1.78 mL, 8.27 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) (1.5 mL, 8.43 mmol) were added and then stirred for 45 min. The resulting solution was cooled to −78 °C, added dropwise of a solution of aldehyde 5 (1.82 g, 5.51 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (36 mL), and stirred for 1 h. Stirring was then further conducted at 0 °C for an additional 1 h. Analysis by LC−MS showed that the reaction was complete (high diastereoselectivity; see the Supporting Information). The reaction was terminated with methanol and saturated sodium bicarbonate. The reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic fractions were washed with brine, dried over a pad of magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (40 μm, 60 Å, 3.0 × 16.5 cm) using 0–5% MeOH in CH2Cl2 as the eluent. A total of 1.4 g of compound 7 was obtained (2.55 mmol, 46%) as a white amorphous solid. LC–MS tR = 1.83 min; ESIMS m/z 549.33 [M + H]+

To a stirred solution of compound 7 (0.114 g, 0.21 mmol), proton sponge (0.325 g, 1.51 mmol), and molecular sieves (4 Å) in CH2Cl2 (3.5 mL) at 5 °C was added Me3OBF4 (0.219 g, 1.48 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at rt. After 68 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction solution was filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (30 μm, 60 Å, 2.3 × 12.3 cm2) using 2–25% EtOAc in hexanes as the eluent. A total of 0.073 g of Boc-Dap (4-OTBS)-phenyloxazolidinone was obtained (0.13 mmol, 63%) as a white amorphous solid.

To a stirred solution of Boc-Dap (4-OTBS)-phenyloxazolidinone (0.073 g, 0.13 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (3 mL) was slowly added HF-Py (140 μL, 1.56 mmol) and then stirred at rt. After 5 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was added to 30 mL of saturated sodium bicarbonate and then extracted with EtOAc. The organic layers were washed with 30 mL of 1 N HCl, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, concentrated in vacuo, and dried further under high vacuum. A total of 58 mg of Boc-Dap (4-OH)-phenyloxazolidinone was obtained (0.13 mmol, quant.) as a white amorphous solid, which was used without further purification.

To a stirred solution of Boc-Dap (4-OH)-phenyloxazolidinone (58 mg, 0.13 mmol) in THF (2 mL) at 5 °C were added DPPA (42 μL, 0.20 mmol), DIAD (77 μL, 0.39 mmol), and PPh3 (103 mg, 0.20 mmol). After 15 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction solution was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (30 μm, 60 Å, 2.3 × 12.3 cm2) using 2–50% EtOAc in hexanes as the eluent. A total of 37 mg of compound 8 was obtained (0.078 mmol, 59%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.42–7.24 (m, 5H), 5.49 (dd, J = 8.6, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.73 (t, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 4.20–4.08 (m, 2H), 4.00–3.76 (m, 4H), 2.88 (s, 3H), 2.87–2.74 (m, 1H), 2.39–2.23 (m, 1H), 2.05–1.83 (m, 1H), 1.39 (s, 9H), 1.03 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.77, 153.97, 139.97, 129.02, 128.24, 126.21, 83.35, 79.61, 70.22, 60.54, 57.71, 57.60, 57.31, 51.07, 50.56, 46.39, 29.86, 28.46, 14.23; LC–MS tR = 1.66 min; ESIMS m/z: 474.30 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 474.2355 [M + H]+ calcd for C23H32N5O6, 474.2347.

Compound 10

To a stirred solution of Boc-Dap (4-N3)-phenyloxazolidinone (241 mg, 0.51 mmol) in THF (10 mL) at 5 °C were added 30% H2O2 (0.81 mL, 8.14 mmol) and 0.5 M LiOH (5 mL, 2.50 mmol). After 15 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction was quenched with 1 M sodium thiosulfate by stirring for 10 min and then extracted with saturated sodium bicarbonate and CH2Cl2, which was cooled to 0–5 °C previously. The aqueous layer was adjusted to pH 2, followed by extraction with EtOAc (three times). The combined organic layer was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate and concentrated in vacuo to afford Boc-Dap (4-N3)-OH 9 as a white solid, which was used without further purification.

To a stirred suspension of H-Phe-OMe HCl salt (54 mg, 0.250 mmol), Boc-Dap (4-N3)-OH 9 (90 mg, 0.274 mmol), EDCI (75 mg, 0.391 mmol), and HOBt (40 mg, 0.261 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was added Et3N (60 μL, 0.430 mmol). After 2 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The mixture was purified by preparatory reversed-phase (RP)-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 50 mg of the title compound was obtained as the TFA salt (0.102 mmol, 41%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.32 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.16 (m, 5H), 4.49 (ddd, J = 9.7, 7.9, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.16–4.02 (m, 1H), 3.95–3.71 (m, 3H), 3.61 (s, 3H), 3.18 (s, 3H), 3.05 (dd, J = 13.7, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.95–2.71 (m, 2H), 2.33–2.12 (m, 2H), 1.95–1.75 (m, 1H), 1.41 (s, 9H), 0.73 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.33, 172.42, 153.28, 137.74, 129.55, 128.56, 126.90, 82.39, 79.50, 60.58, 57.57, 57.21, 53.72, 52.20, 50.94, 50.35, 43.15, 37.19, 29.79, 28.49, 14.63; LC–MS tR = 1.61 min, ESIMS m/z 490.45 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 490.2671 [M + H]+ calcd for C24H36N5O6, 490.2660.

Compound 11

To 4.0 M HCl in dioxane (1 mL, 4 mmol) solution was added Boc-Dap (4-N3)-Phe-OMe 10 (24 mg, 0.05 mmol) and stirred for 2 h until analysis by LC–MS showed that the boc-deprotection reaction was complete. The reaction solution was concentrated in vacuo and dried further under high vacuum. A total of 20.5 mg of the title compound (0.05 mmol, 98%) was obtained as the HCl salt as a pale brown solid, which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.62 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (s, 1H), 7.33–7.17 (m, 5H), 4.60–4.43 (m, 2H), 3.78–3.57 (m, 4H), 3.46–3.35 (m, 1H), 3.33–3.25 (m, 4H), 3.16–3.05 (m, 2H), 2.88 (dd, J = 13.8, 9.9 Hz, 1H), 2.49–2.34 (m, 2H), 1.76 (ddd, J = 13.3, 9.9, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 0.73 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); LC–MS tR = 1.03 min, ESIMS m/z: 390.32 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 390.2146 [M + H]+ calcd for C19H28N5O4, 390.2136.

Compound 13a

To a stirred solution of H-Dap (4-N3)-Phe-OMe 11 (7 mg, 0.02 mmol), Fmoc-MeVal-Val-Dil-OH 12a (11 mg, 0.016 mmol), and Et3N (8 μL, 0.06 mmol) in DMAc (1 mL) were added EDCI (7 mg, 0.04 mmol) and HOBt (2 mg, 0.01 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 15 h. To the mixture was added Et2NH (40 μL, 0.387 mmol). After 1 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and DMAc, and then the mixture was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 6 mg of compound 13a was obtained as the TFA salt (6.66 μmol, 41%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6; a complex spectrum was observed, presumably because of cis/trans conformational isomers): δ 8.90–8.75 (m, 2H), [8.42 (d, J = 7.9 Hz), 8.32 (d, J = 8.0 Hz) 1H], 7.31–7.17 (m, 5H), 4.72–4.63 (m, 1H), 4.59 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (ddd, J = 9.8, 8.0, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.14–4.02 (m, 2H), 4.00–3.63 (m, 5H), [3.61 (s), 3.60 (s) 3H], [3.19 (s), 3.17 (s) 3H], 3.12 (s, 3H), 3.07–2.96 (m, 4H), 2.88 (dd, J = 13.7, 9.7 Hz, 1H), 2.47 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 3H), 2.32–2.16 (m, 3H), 2.12–1.94 (m, 2H), 1.92–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.34–1.19 (m, 1H), 0.98–0.83 (m, 17H), 0.80–0.70 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ 174.38, 173.90, 172.44, 169.46, 167.30, 166.43, 164.91, 137.73, 129.55, 128.98, 128.57, 128.30, 126.91, 85.77, 82.20, 80.61, 78.65, 65.99, 63.66, 60.12, 59.02, 57.89, 57.59, 57.35, 56.07, 55.30, 55.13, 53.72, 52.20, 50.97, 49.36, 43.32, 38.89, 37.48, 37.26, 32.46, 32.09, 32.01, 30.51, 29.90, 25.85, 25.13, 21.50, 20.63, 18.96, 18.90, 18.73, 18.05, 15.95, 14.67, 10.73; LC–MS tR = 1.31 min, ESIMS m/z: 787.72 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 787.5096 [M + H]+ calcd for C40H67N8O8, 787.5076.

Compound 13b

To a stirred solution of H-Dap (N3)-Phe-OMe 11 (18 mg, 0.04 mmol), Fmoc-MeVal-Abu (3-N3)-Dil-OH 12b (26 mg, 0.037 mmol), and Et3N (20 μL, 0.14 mmol) in DMAc (2 mL, 16.23 mmol) were added EDCI (18 mg, 0.09 mmol) and HOBt (4 mg, 0.03 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 15 h. To the mixture was added Et2NH (40 μL, 0.386 mmol). After 3 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and DMAc, and then the mixture was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 22 mg of compound 13b was obtained as a TFA salt (0.024 mmol, 64%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6; a complex spectrum was observed, presumably because of cis/trans conformational isomers): δ [9.10 (d, J = 8.6 Hz), 8.71 (d, J = 9.1 Hz) 1H], 8.90 (br-s, 1H), [8.41 (d, J = 7.9 Hz), 8.33 (d, J = 8.0 Hz) 1H], [7.49–7.33 (m), 7.32–7.07 (m), 5H], 4.86 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (br-s, 1H), 4.48 (ddd, J = 9.7, 7.9, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.33–3.86 (m, 6H), 3.78–3.66 (m, 1H), [3.61 (s), 3.60 (s) 3H], [3.21 (s), 3.18 (s), 3H], [3.13 (s), 3.09 (s), 3H], 3.09–3.01 (m, 2H), 2.98 (s, 3H), 2.93–2.81 (m, 1H), 2.49–2.43 (m, 3H), 2.36–2.17 (m, 3H), 2.09 (dq, J = 13.1, 6.5 Hz, 1H), 1.94–1.64 (m, 2H), 1.36–1.21 (m, 4H), 0.99–0.83 (m, 11H), 0.83–0.66 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 174.38, 172.43, 170.27, 169.45, 167.86, 166.84, 137.79, 137.73, 129.54, 128.80, 128.56, 126.90, 124.86, 80.61, 77.61, 65.98, 60.16, 58.23, 57.90, 57.81, 57.34, 53.71, 52.80, 52.18, 51.44, 43.31, 37.19, 32.67, 32.46, 29.82, 28.82, 25.85, 18.65, 18.22, 18.04, 16.08, 15.97, 14.65, 13.42, 10.94; LC–MS tR = 1.32 min, ESIMS m/z: 814.66 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 814.4972 [M + H]+ calcd for C39H64N11O8, 814.4934.

Compound 13c

To a stirred solution of H-Dap (N3)-Phe-OMe 11 (20 mg, 0.04 mmol), Dov-Val-Dil-OH 12c (20 mg, 0.041 mmol), and Et3N (25 μL, 0.18 mmol) in DMAc (2 mL) were added EDCI (15 mg, 0.08 mmol) and HOBt (5 mg, 0.03 mmol). After 15 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and DMAc, and then the mixture was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 22 mg of compound 13c was obtained as the TFA salt (0.023 mmol, 58%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6; a complex spectrum was observed, presumably because of cis/trans conformational isomers): δ 9.17 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), [8.41 (d, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.32 (d, J = 8.0 Hz) 1H], 7.34–7.08 (m, 5H), 4.89 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (br-s, 1H), 4.48 (ddd, J = 9.7, 7.9, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 4.18–3.89 (m, 3H), 3.81–3.65 (m, 1H), [3.61 (s), 3.60 (s), 3H], 3.29–3.25 (m, 1H), [3.20 (s), 3.18 (s), 3H], [3.13 (s), 3.09 (s), 3H], 3.08–2.94 (m, 7H), 2.88 (dd, J = 13.7, 9.7 Hz, 1H), [2.78 (s), 2.75 (s), 6H], 2.35–2.17 (m, 3H), 1.94–1.69 (m, 2H), 1.38–1.22 (m, 4H), 0.96 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 0.93–0.81 (m, 8H), 0.82–0.71 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO): δ 174.39, 173.54, 172.45, 170.38, 169.45, 165.99, 137.74, 129.56, 128.58, 126.92, 80.59, 77.59, 71.82, 60.17, 58.38, 58.24, 58.15, 58.06, 57.90, 57.83, 57.75, 57.33, 56.90, 53.72, 52.70, 52.26, 52.21, 51.45, 46.15, 43.31, 42.17, 41.50, 37.41, 37.19, 32.52, 31.94, 28.82, 28.15, 27.00, 25.85, 19.63, 19.55, 16.91, 16.08, 16.00, 15.90, 14.83, 14.67, 14.45, 12.39, 11.03, 10.92, 9.05; LC–MS tR = 1.33 min, ESIMS m/z: 828.74 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 828.5119 [M + H]+ calcd for C40H66N11O8, 828.5090.

Compound 15

To a stirred solution of Fmoc-MeVal-Abu (3-N3)-Dil-OtBu (130 mg, 0.18 mmol) in EtOH (3 mL) was added Pd on carbon (150 mg, 0.070 mmol) under a nitrogen atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred under a hydrogen atmosphere. After 4 h, analysis by LC–MS indicated that the reaction was complete. After insoluble materials were removed by filtration, the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 90 mg of compound 15 was obtained as the TFA salt (0.13 mmol, 72%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.66 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.94–7.81 (m, 4H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.47–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.37–7.26 (m, 2H), 4.86 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.56–4.19 (m, 4H), 3.88–3.77 (m, 1H), 3.57–3.44 (m, 1H), 3.28 (s, 3H), 2.99–2.74 (m, 6H), 2.60–2.53 (m, 1H), 2.28–2.00 (m, 2H), 1.79 (br-s, 1H), 1.48–1.27 (m, 10H), 1.22–1.08 (m, 3H), 0.97–0.66 (m, 14H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 171.27, 170.78, 170.01, 156.49, 144.28, 144.18, 141.24, 128.10, 127.51, 125.41, 120.58, 80.51, 78.47, 67.18, 63.77, 57.96, 51.48, 48.05, 47.19, 38.67, 33.0, 30.08, 28.15, 28.07, 27.25, 25.69, 19.41, 19.19, 16.25, 14.90, 11.04; LC–MS tR = 1.65 min, ESIMS m/z: 695.65 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 695.4350 [M + H]+ calcd for C39H59N4O7, 695.4378.

Compound 16

To a stirred solution of Fmoc-MeVal-Abu (3-NH2)-Dil-OtBu (43 mg, 0.06 mmol) in DMAc (1 mL) was added glutaric anhydride (7 mg, 0.06 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at 60 °C. After 4 h, analysis by LC–MS showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 40 mg of compound 16 was obtained as the TFA salt (0.043 mmol, 70%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.99 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.79–7.60 (m, 3H), 7.42 (td, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 4.98–4.86 (m, 1H), 4.56–4.18 (m, 5H), 4.14–4.01 (m, 2H), 3.90–3.63 (m, 1H), 3.22 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 3H), 2.99 (s, 3H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.21–2.13 (m, 2H), 2.19–1.89 (m, 4H), 1.87–1.60 (m, 4H), 1.40 (s, 9H), 1.37–1.29 (s, 2H), 1.08–0.57 (m, 14H); LC–MS tR = 1.81 min, ESIMS m/z: 809.70 [M + H]+.

Compound 17

To a stirred solution of Boc-Dap (4-N3)-Phe-OMe (35 mg, 0.06 mmol) in EtOH (2 mL) was added Pd on carbon (30 mg, 0.028 mmol) under a nitrogen atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred under a hydrogen atmosphere. After 4 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. After insoluble materials were removed by filtration, the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure.

A total of 26 mg of compound 17 was obtained (0.06 mmol, 97%) as a white amorphous solid, which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.30 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (s, 2H), 7.35–7.12 (m, 5H), 4.52 (ddd, J = 9.6, 7.9, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.01–3.39 (m, 7H), 3.21 (s, 3H), 3.05 (dd, J = 13.8, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 2.89 (dd, J = 13.7, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 2.38–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.88 (br-s, 1H), 1.42 (s, 9H), 0.75 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H); LC–MS tR = 1.13 min, ESIMS m/z: 464.45 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 464.2790 [M + H]+ calcd for C24H37N3O6, 464.2755.

Compound 18

To a stirred solution of Fmoc-MeVal-Abu (3-NHCOCH2CH2CH2COOH)-Dil-OtBu (61 mg, 0.08 mmol), Boc-Dap (4-NH2)-Phe-OMe (33 mg, 0.07 mmol), and DIEA (37 μL, 0.21 mmol) in DMAc (1.5 mL) was added HATU (70 mg, 0.184 mmol). After 4 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. To the mixture was added 1 N HCl aq., and then the mixture was stirred for 1 h. After separation, the organic layer was washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate and brine and dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate. The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried further under high vacuum. A total of 95 mg of enriched Fmoc-MeVal-Abu (3-NHCOCH2CH2CH2CO-[Boc-Dap (4-NH-)]-Phe-OMe)-Dil-OtBu was obtained as a white amorphous solid, which was used without further purification.

A solution of Fmoc-MeVal-Abu (3-NHCOCH2CH2CH2CO-[Boc-Dap (4-NH-)]-Phe-OMe)-Dil-OtBu (90 mg, 0.07 mmol) in 4 M HCl in dioxane (3 mL, 12 mmol) was stirred at rt. After 2 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The crude reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and dried further under high vacuum. The residue was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 81 mg of compound 18 was obtained as the TFA salt (0.07 mmol, 99%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 12.24 (s, 1H), 8.95 (s, 1H), 8.56 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 8.26–8.11 (m, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.47–7.38 (m, 3H), 7.38–7.16 (m, 8H), 6.56–6.48 (m, 2H), 4.62–4.16 (m, 4H), 4.13–3.64 (m, 4H), 3.62 (s, 3H), 3.46–3.16 (m, 9H), 3.14–2.84 (m, 4H), 2.79 (s, 3H), 2.23–1.95 (m, 8H), 1.89–1.58 (m, 2H), 1.18–0.83 (m, 1H), 1.12–0.83 (m, 6H), 0.83–0.56 (m, 17H); LC–MS tR = 1.54 min, ESIMS m/z: 1099.03 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 1098.6164 [M + H]+ calcd for C59H84N7O13, 1098.6122.

Compound 19

To a stirred solution of 18 (81 mg, 0.0714 mmol) in EtOAc (500 mL) were added CMPI (100 mg, 0.391 mmol) and DIEA (62 μL, 0.36 mmol). After 16 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the macrocyclic condensation reaction was complete. The mixture was evaporated to give a yellow oil. To a stirred solution of the resulting oil in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was added Et2NH (500 μL, 4.83 mmol). After 2 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the deprotection reaction was complete. The reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and DMAc, and then the mixture was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 40 mg of compound 19 was obtained as the TFA salt (0.041 mmol, 61%) as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.08 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 8.84 (s, 1H), 8.69 (s, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 7.88–7.76 (m, 2H), 7.33–7.17 (m, 5H), 6.60–6.47 (m, 1H), 4.92–4.81 (m, 1H), 4.62 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 4.58–4.47 (m, 1H), 4.37 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 4.34–4.28 (m, 1H), 4.27–4.18 (m, 1H), 4.02 (d, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 3.83–3.79 (m, 1H), 3.69 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.65–3.55 (m, 2H), 3.33–3.25 (m, 5H), 3.08 (s, 3H), 2.96 (s, 3H), 2.93–2.83 (m, 1H), 2.56–2.52 (m, 3H), 2.42–2.19 (m, 3H), 2.17–1.92 (m, 3H), 1.89–1.65 (m, 6H), 1.29–1.13 (m, 1H), 1.08–1.03 (m, 4H), 1.07–0.70 (m, 17H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO): δ 174.35, 172.49, 171.91, 171.69, 171.34, 166.34, 137.74, 129.58, 128.59, 126.94, 80.33, 65.95, 60.79, 58.53, 57.65, 57.39, 54.78, 53.74, 53.03, 52.30, 47.53, 45.88, 44.05, 41.80, 40.88, 37.16, 36.38, 36.03, 32.59, 32.43, 32.02, 31.33, 29.92, 29.77, 29.11, 25.99, 23.75, 23.43, 18.91, 18.75, 18.19, 17.81, 15.92, 14.93, 14.75, 11.47, 10.14; LC–MS tR = 1.11 min, m/z: 858.76 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 858.5345 [M + H]+ calcd for C44H71N7O10, 858.5335.

Compound 21

To a stirred solution of Dov-Abu (3-N3)-Dil-OtBu (180 mg, 0.29 mmol) and N-(but-3-yn-1-yl)-2-chloroacetamide (75 mg, 0.52 mmol) in DMF (5 mL) was added CuBr (76 mg, 0.53 mmol). After 15 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The crude suspension was diluted with 15 mL of DMF, 2 mL of 0.5 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 10 mL of water. The mixture was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC using MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA as the eluent. A total of 120 mg of Dov-Abu (3-triazole–CH2CH2NH–acetyl-Cl)-Dil-OtBu (0.016 mmol, 54%) was obtained as a white amorphous solid.

Dov-Abu (3-triazole−CH2CH2NH−acetyl-Cl)-Dil-OtBu (120 mg, 0.016 mmol) was stirred in 4.0 M HCl in dioxane (2.4 mL, 4 mmol). After 3 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The crude reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. A total of 89 mg of compound 21 was obtained as the HCl salt (0.19 mmol, 99%) as an off-white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6; a complex spectrum was observed, presumably because of conformational isomers): δ 9.83 (s, 1H), [9.58 (d, J = 8.7 Hz), 9.35 (d, J = 8.7 Hz) 1H], 8.35 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), [7.80 (s), 7.94 (s), 1H], 5.46 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.09–4.98 (m, 1H), 4.38 (br-s, 1H), [4.07 (s), 4.05 (s), 2H], 3.82 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (br-s, 1H), 3.42–3.31 (m, 2H), 3.18 (s, 3H), [2.93 (s), 2.90 (s), 3H], 2.84–2.67 (m, 8H), 2.37–2.13 (m, 2H), 1.99 (dd, J = 15.7, 9.3 Hz, 1H), 1.83–1.68 (m, 1H), 1.63–1.45 (m, 4H), 1.36–1.19 (m, 1H), 0.96 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 0.91–0.80 (m, 6H), 0.75 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.28, 169.78, 166.33, 165.96, 159.43, 159.06, 158.71, 158.35, 144.30, 122.75, 78.31, 72.33, 71.78, 57.54, 56.57, 53.24, 50.27, 43.07, 41.93, 41.60, 39.04, 38.23, 37.28, 32.72, 31.64, 28.92, 27.03, 25.82, 25.66, 24.01, 19.55, 16.91, 16.20, 10.90; LC–MS tR = 0.94 min, m/z: 602.49, 604.50 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 602.3425 [M + H]+ calcd for C27H49ClN7O6, 602.3427.

Compound 22

To a stirred solution of compound 21 (24 mg, 0.04 mmol) and H-Dap (N3)-Phe-OMe HCl salt 11 (15 mg, 0.04 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) were added DIEA (25 μL, 0.140 mmol), EDCI (18 mg, 0.09 mmol), and HOBt (5 mg, 0.03 mmol). After 18 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction conversion was complete. The reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and DMAc, and then the mixture was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC with a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 10 μm, C18 110 Å column (150 × 30 mm2) using 5–95% MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA solution as the eluent. A total of 24 mg of compound 22 was recovered as the TFA salt (0.022 mmol, 59%) as a white amorphous solid. LC–MS tR = 1.29 min, m/z: 973.83, 975.85 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 973.5387 [M + H]+ calcd for C46H74ClN12O9, 973.5385.

Compound 23

To a stirred solution of compound 13a (15 mg, 0.017 mmol) and N-(but-3-yn-1-yl)-2-bromoacetamide (5 mg, 0.026 mmol) in DMF (1 mL) was added CuBr (10 mg, 0.067 mmol). After 15 h, analysis by LC–MS showed that the reaction was complete. The crude suspension was diluted with 7 mL of DMAc, 2 mL of 0.5 M EDTA, and 5 mL of water. The mixture was purified by preparatory RP-HPLC using MeCN in 0.05% aqueous TFA as the eluent. A total of 5 mg of compound 23 (4.58 μmol, 28%) was obtained as a white amorphous solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6; a complex spectrum was observed, presumably because of cis/trans conformational isomers): δ 8.80 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 8.38–8.29 (m, 1H), 8.03–7.92 (m, 1H), 7.32–7.14 (m, 5H), 5.12–4.90 (m, 1H), 4.67 (br-s, 1H), 4.57 (t, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 4.52–4.41 (m, 1H), 4.24 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.09–3.94 (m, 2H), 3.89–3.39 (m, 9H), 3.35–3.24 (m, 2H), 3.23–3.11 (m, 6H), 3.08–2.94 (m, 4H), 2.92–2.56 (m, 3H), 2.45 (t, J = Hz, 3H), [2.35–2.30 (m), 2.29–2.14 (m), 2H], 2.12–1.92 (m, 2H), 1.87–1.67 (m, 2H), 1.35–1.18 (m, 1H), [1.11–1.05 (m), 1.02–0.83 (m), 17H], 0.81–0.66 (m, 6H); LC–MS tR = 1.19 min, m/z: 976.79, 978.77 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z: 976.4874, 978.4873 [M + H]+ calcd for C46H75BrN9O9, 976.4866.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the work of C. Kemball and M. Wu for in vitro cytotoxicity work and B. Wiggins for mass spectrometry assistance. They would like to acknowledge D. Weller and K. Morrison for manuscript review and helpful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00093.

Detailed experimental procedures and NMR spectra (1H and 13C) for 8, 10, 11, 13a, 13b, 13c, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, and 23 (PDF)

Author Present Address

† Astellas Pharma, Tsukuba Research Center, 21 Miyukigaoka, Tsukuba-shi, Ibaraki 305–8585, Japan.

Author Present Address

‡ Asilomar Bio, Inc., 5858 Horton St, Emeryville, CA, 94608, USA.

Author Present Address

§ Ajinomoto Althea, Inc., 11040 Roselle St, San Diego, CA, 92121, USA.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cragg G. M.; Grothaus P. G.; Newman D. J. Impact of natural products on developing new anti-cancer agents. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3012–3043. 10.1021/cr900019j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chari R. V. J.; Miller M. L.; Widdison W. C. Antibody-drug conjugates: an emerging concept in cancer therapy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 3796–3827. 10.1002/anie.201307628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg G. M.; Newman D. J. A tale of two tumor targets: topoisomerase I and tubulin. The Wall and Wani contribution to cancer chemotherapy. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 232–244. 10.1021/np030420c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumontet C.; Jordan M. A. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 790–803. 10.1038/nrd3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon L. L.; Soussain C.; Jahnke K.; Johanson C.; Siegal T.; Smith Q. R.; Hall W. A.; Hynynen K.; Senter P. D.; Peereboom D. M.; Neuwelt E. A. Chemotherapy delivery issues in central nervous system malignancy: a reality check. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2295–2305. 10.1200/jco.2006.09.9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit G. R.; Kamano Y.; Herald C. L.; Tuinman A. A.; Boettner F. E.; Kizu H.; Schmidt J. M.; Baczynskyj L.; Tomer K. B.; Bontems R. J. The isolation and structure of a remarkable marine animal antineoplastic constituent: dolastatin 10. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 6883–6885. 10.1021/ja00256a070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsalis J. C.; Schindler-Horvat J.; Hill J. R.; Tomaszewski J. E.; Donohue S. J.; Tyson C. A. Toxicity of dolastatin 10 in mice, rats and dogs and its clinical relevance. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1999, 44, 395–402. 10.1007/s002800050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitot H. C.; McElroy E. A. Jr.; Reid J. M.; Windebank A. J.; Sloan J. A.; Erlichman C.; Bagniewski P. G.; Walker D. L.; Rubin J.; Goldberg R. M.; Adjei A. A.; Ames M. M. Phase I trial of dolastatin-10 (NSC 376128) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 525–531. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/5/3/525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug L. M.; Miller V. A.; Kalemkerian G. P.; Kraut M. J.; Ng K. K.; Heelan R. T.; Pizzo B. A.; Perez W.; McClean N.; Kris M. G. Phase II study of dolastatin-10 in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2000, 11, 227–228. 10.1023/a:1008349209956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani M.; Natsume T.; Watanabe J.-I.; Kobayashi M.; Murakoshi M.; Mikami T.; Nakayama T. TZN-1027, an antimicrotuble agent, attacks tumor vasculature and induces tumor cell death. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 2000, 91, 837–844. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb01022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishampayan U.; Glode M.; Du W.; Kraft A.; Hudes G.; Wright J.; Hussain M. Phase II study of dolastatin-10 in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 4205–4208. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/6/11/4205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin K.; Longmate J.; Synold T. W.; Gandara D. R.; Weber J.; Gonzalez R.; Johansen M. J.; Newman R.; Baratta T.; Doroshow J. H. Dolastatin-10 in metastatic melanoma: a phase II and pharmokinetic trial of the California Cancer Consortium. Invest. New Drugs 2001, 19, 335–340. 10.1023/a:1010626230081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad E. D.; Kraut E. H.; Hoff P. M.; Moore D. F. Jr.; Jones D.; Pazdur R.; Abbruzzese J. L. Phase II study of dolastatin-10 as firstline treatment for advanced colorectal cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 25, 451–453. 10.1097/00000421-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M. A.; Blessing J. A.; Lentz S. S. A phase II trial of dolastatin-10 in recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2003, 89, 95–98. 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mehren M.; Balcerzak S. P.; Kraft A. S.; Edmonson J. H.; Okuno S. H.; Davey M.; McLaughlin S.; Beard M. T.; Rogatko A. Phase II trial of dolastatin-10, a novel anti-tubulin agent, in metastatic soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma 2004, 8, 107–111. 10.1155/2004/924913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge M. J. A.; van der Gaast A.; Planting A. S. T.; van Doorn L.; Lems A.; Boot I.; Wanders J.; Satomi M.; Verweij J. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the dolastatin 10 analogue TZT-1027, Given on days 1 and 8 of a 3-week cycle in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 3806–3813. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-04-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler H. L.; Tothy P. K.; Wolff R.; McCormack R. A.; Abbruzzese J. L.; Mani S.; Wade-Oliver K. T.; Vokes E. E. Phase II trial of dolastatin-10 in advanced pancreaticobiliary cancers. Invest. New Drugs 2005, 23, 489–493. 10.1007/s10637-005-2909-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez E. A.; Hillman D. W.; Fishkin P. A.; Krook J. E.; Tan W. W.; Kuriakose P. A.; Alberts S. R.; Dakhil S. R. Phase II trial of dolastatin-10 in patients with advanced breast cancer. Invest. New Drugs 2005, 23, 257–261. 10.1007/s10637-005-6735-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S.; Keohan M. L.; Saif M. W.; Rushing D.; Baez L.; Feit K.; DeJager R.; Anderson S. Phase II study of intravenous TZT-1027 in patients with advanced or metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas with prior exposure to anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Cancer 2006, 107, 2881–2887. 10.1002/cncr.22334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senter P. D.; Sievers E. L. The discovery and development of brentuximab vedotin for use in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 631–637. 10.1038/nbt.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez H. L.; Cardarelli P. M.; Deshpande S.; Gangwar S.; Schroeder G. M.; Vite G. D.; Borzilleri R. M. Antibody-drug conjugates: Current status and future directions. Drug Discovery Today 2014, 19, 869–881. 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maderna A.; Leverett C. A. Recent advances in the development of new auristatins: structural modifications and application in antibody drug conjugates. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 1798–1812. 10.1021/mp500762u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flahive E.; Srirangam J. K.. The Dolastatins: Novel Antitumor Agents from Dolabella auricularia. In Anticancer Agents from Natural Products, 2nd ed.; Cragg G. M., Kingston D. G. I., Newman D. M., Eds.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, 2012; pp 263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki K.; Kobayashi M.; Natsume T.; Gondo M.; Mikami T.; Sakakibara K.; Tsukagoshi S. Synthesis and antitumor activity of novel dolastatin 10 analogs. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1995, 43, 1706–1718. 10.1248/cpb.43.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M.; Natsume T.; Tamaoki S.; Watanabe J.-i.; Asano H.; Mikami T.; Miyasaka K.; Miyazaki K.; Gondo M.; Sakakibara K.; Tsukagoshi S. Antitumor activity of TZT-1027, a novel dolastatin 10 derivative. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1997, 88, 316–327. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit G. R.; Srirangam J. K.; Barkoczy J.; Williams M. D.; Durkin K. P.; Boyd M. R.; Bai R.; Hamel E.; Schmidt J. M.; Chapuis J. K. J. Antineoplastic agents 337. Synthesis of dolastatin 10 structural modifications. Anti Canc. Drug Des. 1995, 10, 529–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn B. A.; Barnscher S. D.; Snyder J. T.; An Z.; Dodd J. M.; Dugal-Tessier J. Investigation of hydrophilic auristatin derivatives for use in antibody drug conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 371–381. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugal-Tessier J.; Barnscher S. D.; Kanai A.; Mendelsohn B. A. Synthesis and evaluation of dolastatin 10 analogues containing heteroatoms on the amino acid side chains. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 2484–2491. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajula P. K.; Asthana J.; Panda D.; Chakraborty T. K. A synthetic dolastatin 10 analogue suppresses microtubule dynamics, inhibits cell proliferation, and induces apoptotic cell death. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2235–2245. 10.1021/jm3009629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty T. K.; Gajula P. K.; Panda D.; Asthana J.. Oligopeptides and process for preparation thereof. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2012123957A1, Sept 20, 2012.

- Park Y. J.; Jeong J. K.; Choi Y. M.; Lee M. S.; Choi J. H.; Cho E. J.; Song H.; Park S. J.; Lee J. H.; Hong S. S.. Dolastatin-10 derivative, method of producing same and anticancer drug composition containing same. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2014046441 A1, Mar 27, 2014.

- Maderna A.; Doroski M.; Subramanyam C.; Porte A.; Leverett C. A.; Vetelino B. C.; Chen Z.; Risley H.; Parris K.; Pandit J.; Varghese A. H.; Shanker S.; Song C.; Sukuru S. C. K.; Farley K. A.; Wagenaar M. M.; Shapiro M. J.; Musto S.; Lam M.-H.; Loganzo F.; O’Donnell C. J. Discovery of cytotoxic dolastatin 10 analogues with N-terminal modification. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10527–10543. 10.1021/jm501649k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maderna A.; Leverett C. A. Recent advances in the development of new auristatins: Structural modifications and application in antibody drug conjugates. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 1798–1812. 10.1021/mp500762u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heravi M. M.; Zadsirjan V. Oxazolidinones as chiral auxiliaries in asymmetric aldol reactions applied to total synthesis. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2013, 24, 1149–1188. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2013.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba S. Application of organic azides for the synthesis of nitrogen-containing molecules. Synlett 2012, 1, 21–44. 10.1055/s-0031-1290108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M. T.; Sengupta D.; Ha T.-K. Another look at the decomposition of methyl azide and methanimine: How is HCN formed?. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 6499–6503. 10.1021/jp953022u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doronina S. O.; Mendelsohn B. A.; Bovee T. D.; Cerveny C. G.; Alley S. C.; Meyer D. L.; Oflazoglu E.; Toki B. E.; Sanderson R. J.; Zabinski R. F.; Wahl A. F.; Senter P. D. Enhanced activity of monomethylauristatin F through monoclonal antibody delivery: Effects of Linker technology on Efficacy and Toxicity. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006, 17, 114–124. 10.1021/bc0502917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurugan P.; Matosiuk D.; Jozwiak K. Click chemistry for drug development and diverse chemical–biology applications. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 4905–4979. 10.1021/cr200409f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.