Abstract

Parasites of the Leishmania genus, which are the causative agents of leishmaniasis, display a complex life cycle, from a flagellated form (promastigotes) residing in the midgut of the phlebotomine vector to a non-flagellated form (amastigote) invading the mammalian host. The cellular process for the conversion between these forms is an interesting biological phenomenon involving modulation of the plasma membrane. In this study, we describe a selective autophagic-like process during the in vitro differentiation of Leishmania mexicana promastigote to amastigote-like cells. This process is responsible for size reduction and shape change of the promastigote (15–20 μm long) to the rounded amastigote-like form (4–5 μm long), identical to the one that infects host macrophages. This autophagic-like process is characterized by a profound folding of the plasma membrane and the presence of abundant cytoplasmic lipid droplets that may be the product of changes in the lipid metabolism. The key feature for the differentiation process at either pH 7.0 or pH 5.5 is the shift in temperature from 25 to 35 °C. Flagella shortening during the differentiation process appears as the product of continuous flagellar microtubular disassembly that is also accompanied by changes in mitochondrion localization. Drugs directed at blocking the parasite autophagic-like process could be important as new strategies to fight the disease.

Keywords: Leishmania, Differentiation, Plasma membrane, Autophagy

Introduction

Parasites of the Leishmania genus, members of the Trypanosomatidae family, are the causative agents of a complex spectrum of diseases known as leishmaniasis. During their life cycle between the vector phlebotomine midgut to the mammalian hosts, the parasites face different contrasting environments to which they respond by differentiating into new forms, capable of surviving and proliferating inside the host. In the insect vector, the parasites grow as flagellated promastigotes that differentiate into intracellular non-motile amastigotes upon entering the phagolysosome of the host macrophages (Wheeler et al. 2011). This process is accompanied by a number of changes at the level of morphology, metabolism, gene expression, organelle modification, surface protein expression, and cell size reduction (Malcolm et al. 2011; Fong and Chang 1982; Holzer et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2009; Bemantes et al. 2017). Recently, the importance of autophagy in the parasite differentiation process during the life cycle has been highlighted as part of the adaptive capacity to extreme environments (Brennand et al. 2011; Besteiro et al. 2006). During autophagy, the removal of redundant or damaged organelles is an important survival mechanism in response to conditions of starvation, stress, temperature changes, and drug pressure. In addition, autophagy is important in remodeling cellular morphology and recycling cytoplasmic constituents (He and Klionsky 2009; Brennard et al. 2012; Campos Salinas and Gonzalez-Rey 2009; Monte Neto et al. 2011). A relevant step in the study of parasite differentiation is to mimic the transformation process in axenic culture, by shifting the conditions from 26 °C and pH 7.0 resembling the insect midgut to 36 °C and pH 5.5 as in the parasitophorous vacuole of the host macrophage (Zakay et al. 1998; Stinson et al. 1989; Debrabant et al. 2004; Barack et al. 2005). Leishmania mexicana is very sensitive to temperature changes. These parasites infect and proliferate well within cultured macrophages at 34 °C, but they fail to infect macrophages at 37.5 °C (Biegel et al. 1983). Temperature and pH play an important role in triggering the differentiation from promastigote to amastigote and vice versa (Zilverstein and Shapira 1994). In addition, the exposure to elevated temperatures appears as a major signal for morphological changes into the amastigote form of New World Leishmania species (Eperon and MacMahon-Pratt 1989a, b; Stinson et al. 1989). The aim of the present work was to investigate morphological changes and size reduction in culture conditions mimicking the parasite life cycle. We observed that the morphological changes and size reduction are the result of a plasma membrane-cytoskeleton complex massive invagination leading to the formation of large cytoplasmic empty vesicles surrounded by microtubules (MTs). We denominate this mechanism as a selective autophagic-like process of the plasma membrane (PMATG).

Materials and methods

Parasite culture

L. mexicana promastigotes of strain NR were initially isolated from infected mice (Ramirez and Guevara 1987). This cell line was maintained in culture at 26 °C in LIT modified medium pH 7.2 supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). Axenic L. mexicana amastigote-like forms were obtained after differentiation of promastigotes by exposure to 199 and RPMI 1640 media, at 35 °C pH 5.5 and to LIT modified medium at 35 °C and pH 7.0 and 5.5, supplemented with 15% FBS during 120 h.

Transmission electron microscopy

Leishmania promastigotes grown at 26 °C pH 5.5 and at 26 °C pH 7.0 and after incubation at 35 °C pH 5.5 in the different media for 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h (108 cells for each sample) were washed twice in 0.1 M pH 7.2 cacodylate buffer and fixed with Karnovsky (Karnovsky 1965) solution for 1 h at 4 °C, washed again, and post-fixed for 1 h with the same buffer containing 1% osmium tetroxide. The cells were then washed again, dehydrated in an increase of ethanol series followed with propylene oxide, and finally embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed under an H500 electron microscope.

Cell size changes quantification assay

In order to quantify the change in cell size during the process of differentiation, the cell perimeter was evaluated using the Image J processing program. Six images taken at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h were acquired randomly and the contours of 20 to 40 cells were measured per time point. The size of the contours measured is expressed in micrometers.

Results

Cellular events during the transformation process from promastigote- to the amastigote-like form in different media from 26 to 35 °C

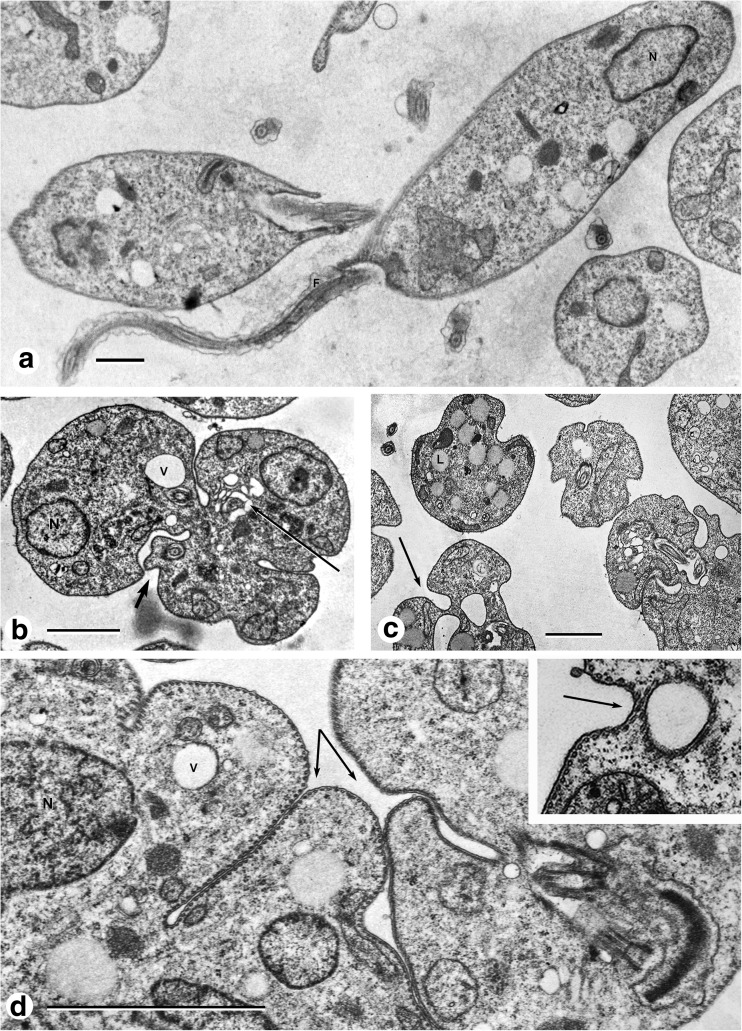

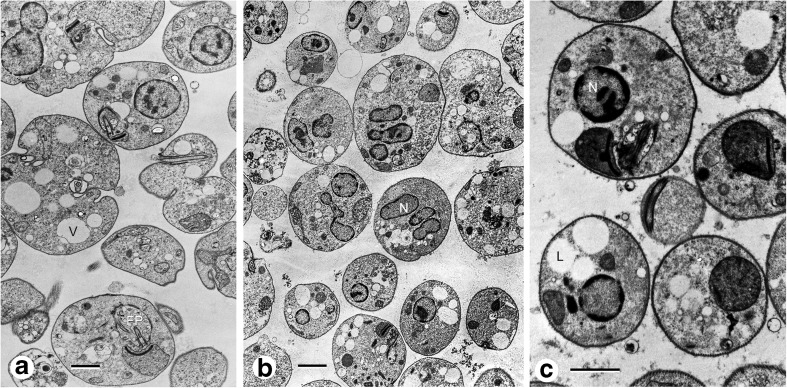

Promastigotes grown in modified LIT medium at 26 °C at either pH 7.0 or 5.5 showed similar morphological features, including an elongated cell body, free long flagella with a length similar to the parasite body, a nucleus with a nucleolus, and dense chromatin patches that adhered to the internal nuclear membrane (Fig. 1a). In contrast, promastigotes exposed to 35 °C pH 7.0 for 24 h presented an ameboid form generated by an extensive process of autophagocytosis of the cell membrane with attached sub-pellicular MTs. The invaginated membrane-microtubule complex formed deep pockets of different sizes and widths that closed and fused within the cytoplasm, leading to the formation of large empty vesicles surrounded by MTs (Fig 1b, c, d, inset). We observed and measured two cell populations, 70% comprising cells with a contour smaller than 70 μm and the other one with a contour larger than 70 μm. After 48 h of incubation in the same medium, 80% comprising cells with a contour smaller than 70 μm and presenting irregular forms still displaying invaginations of the cell membrane and the presence of empty cytoplasmic vesicles surrounded by MTs. The flagella were reduced in size and the flagellar pocket was full of vesicles (Fig. 2a). At 72 h, all cells presented an ovoid shape with a smooth surface; no detectable membrane invagination was observed and internal vesicles were still present surrounded by MTs (Fig. 2b). A homogeneous round cell population, 90% with a contour smaller than 70 μm, was present after 72 h. From 96 to 120 h, the process of transformation to the amastigote-like form appeared to be completed. The cell population reduced its perimeter from 70 to 80 μm at 24 h to 40 μm after 72 h. However, these values are approximations because an ultrathin section prepared for electron microscopy observations (0.8 μm) comprises only a section of the cells. In general, the cell nuclei presented a condensed chromatin adhering to the internal nuclear membrane and a central nucleolus (Fig. 2c). The size reduction of Leishmania promastigote is monitored by a significant invagination process of the plasma membrane-cytoskeleton complex identified by the formation of large inside-out plasma membrane vesicles surrounded by MTs observed 24 h after pH and temperature changes. The induced differentiation process is further characterized by a flagellar pocket full of vesicles of different sizes displaying a fibrillary or punctuated material inside, in an apparent continuous process of excretion and the presence of more than one nucleus in some cells. As soon as the cells were incubated at 35 °C (2 h), the flagella began a process of size reduction. At 72 h, all cells had a short flagellum whose size was equivalent to one of the flagellar pockets and the mitochondrion appeared fragmented, elongated, and running underneath the plasma membrane showing a few cristae or dilated cisternae. In the cytoplasm, the presence of lipid droplets (Figs. 1c and 2b) seems to increase in size and number during the incubation time at higher temperatures.

Fig. 1.

a L. mexicana promastigotes growing in LIT medium at 26 °C. b After 24 h of incubation at 35 °C pH 7.0 plasma membrane invaginations (short arrow), vesicles surrounded by MTs (long arrow). c Plasma membrane invaginations (long arrow), lipid droplets in the cytoplasm (L), vesicles surrounded by MTs (V). d Deep invaginations of the plasma membrane-MT complex (arrows). Inset A large vesicle recently form limited by MTs

Fig. 2.

L mexicana promastigotes incubated at 35 °C pH 7.0 in LIT medium. a After 48 h cells with different forms, large internal vesicles (v) plasma membrane invaginations, flagellar pocket full of vesicles (Fp), mitochondrion (M). b After 72 h, oval or rounded cells some with two or three nuclei (N), lipids droplets in the cytoplasm (L). (c) Cells after 96 h, amastigote-like cells, round form, large lipid droplets in the cytoplasm (L), nucleus (N)

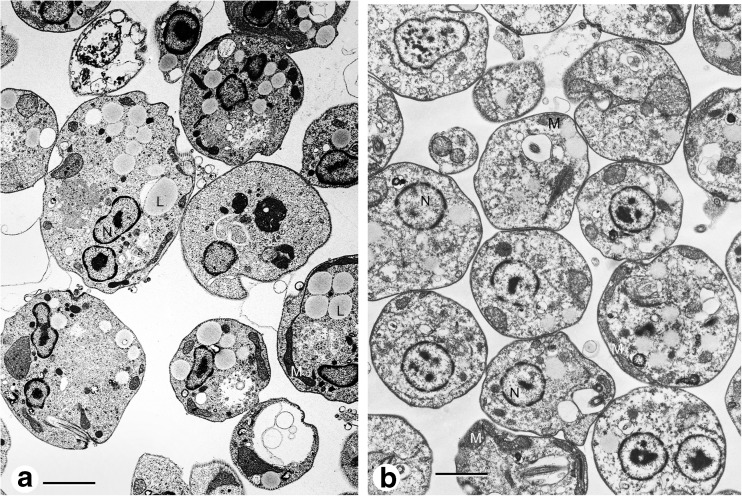

Ultrastructure of cells incubated in LIT modified medium pH 5.5

Cells incubated in LIT modified medium at pH 5.5 or 7.0 and at 35 °C did not display major differences during the cell transformation process, except that the cell membrane autophagic process was more intense during the first 24 h at pH 5.5. The entire process seemed to be favored at this pH (Fig. 3a). The cell population after 48 h of incubation was homogeneous in size, and the autophagic process was concluded (Fig. 3b). After 96 h, all cells presented an amastigote-like form (Fig. 3c). The mitochondrion recovered its normal shape and position, suggesting that the process was completed. This aspect was maintained until the completion of the study after 120 h, with the presence of large lipid droplets in the amastigote-like cells.

Fig. 3.

L mexicana promastigotes incubated in LIT medium at 35 °C, pH 5.5. a Deep cell membrane invaginations (arrow), flagellar pocket full of excretion material (FP). b After 48 h of incubation quite rounded cells, some cells are still invaginating the membrane, mitochondrion underneath the plasma membrane (M). c After 96 h of incubation, amastigote like-cells, lipid droplets (L)

Ultrastructure of cells incubated in 199 medium pH 5.5 at 35 °C

Cells incubated in 199 medium pH 5.5 present irregular ovoidal shapes within the first 24 h, with membrane-MT complex invagination. Cell membrane invaginations were still observed after 48 h, and the mitochondrion was located below the plasma membrane in approximately 25% of the cells. Empty cytoplasmic vesicles were present as well as abundant lipid droplets that sometimes occupied more than 50% of the cytoplasm (Fig. 4a). The mitochondrion was either still below the plasma membrane or was returning to its original position and form. The induced cell differentiation to amastigote-like cells was completed after 96 h of incubation.

Fig. 4.

a Cells after 24 h of incubation in 199 medium pH 5.5, cells with irregular shapes, large lipid droplets in the cytoplasm (L), mitochondrion (M). b Cells after 24 h of incubation in RPMI rounded cells, mitochondrion underneath the plasma membrane (M)

Ultrastructure of cells incubated in RPMI pH 5.5 at 35 °C

After 24 h, the whole cell population is rounded, with a slightly irregular or smooth surface. The process of the cell membrane invagination is no longer observed. Some cells have one or two nuclei and the flagella are smaller. The cytoplasm contains lipid droplets and the mitochondrion is elongated below the plasma membrane (Fig. 4b). After 48 h, all cells have an ovoidal shape with a smooth surface. Cells have completed an amastigote-like form after 72 h, with lipid droplets present in the cytoplasm, and the mitochondrion is in its normal position and shape. The cell population begins to be lysed after 96 h in culture (not shown).

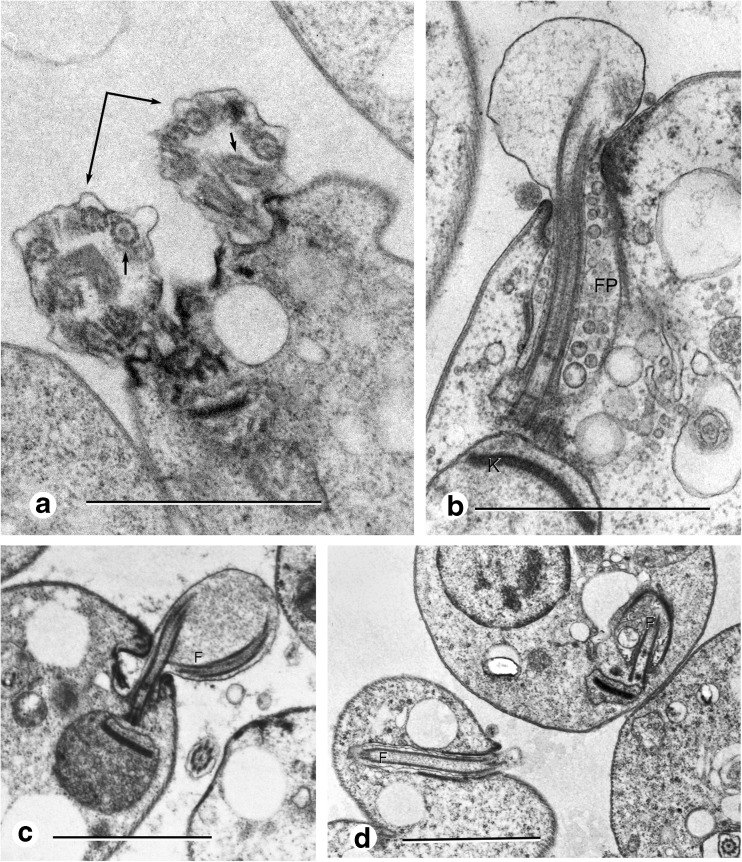

Flagella size reduction during heat shock treatment

The flagellar pocket in promastigotes is the main site of endocytosis/exocytosis across the plasma membrane. Soon thereafter (2–3 h), when the cells were transferred from 26 to 35 °C in any medium or pH, the flagella began a drastic size reduction until reaching the flagellar pocket. Cell division was initiated displaying the presence of two slightly separated flagella. The flagellar membrane appeared as a distended bag, showing different transversal and longitudinal cutting planes, coincident with the presence of a coiled internal microtubular assembly. The typical organization of nine doublets and a central pair of MTs in the transversal plane could be observed (Fig. 5a). After 48 h, flagella were in a later stage of retraction as observed in a cut longitudinal plane. The distended flagellar membrane enclosed a punctuated material in a reticular disposition and a still organized microtubular structure from the basal body to the limit of the flagellar pocket, and some vestiges of the outer and central microtubules were detected (Fig. 5b). The cells showed a coiled fragmented microtubular assembly enclosed in a membrane bag abundant in depolymerized material (Fig. 5c). Finally, amastigote-like cells still displayed a short flagellum inside the flagellar pocket while the central pair of MTs was no longer observed (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Flagellum size reduction. a Two flagella in a dividing cell 3 h after incubation at 35 °C in 199 medium, pH 5.5, MT assembly coiled urdergoing fragmentation and depolimerization (short arrows). b Flagellar membrane containing particulate material and vestiges of the MT assembly central core (F), flagellar pocket full of vesicles (Fp). c MT assembly coiled partially depolimerized inside flagellar membrane (F), mitochondrion (M), kinetoplast (K). d Flagellum of flagellar pocket size (F)

Discussion

In the present study, the in vitro transformation of L. mexicana promastigote- into the amastigote-like forms was analyzed at the ultrastructural level under different culture conditions. The results indicate that the velocity of the differentiation process depends on the culture incubation medium used, being more rapid in RPMI than in 199 or LIT modified medium, in the same pH and temperature conditions. Our cultures are not synchronized and thus are heterogeneous with respect to their cell cycle. However, we quantified the percentage of cells still invaginating the plasma membrane with respect to those in which this process has ended, noticing that already after 24 h, 70% of the cell population presented a three times striking reduction of the elongate cell perimeter from 70 to 120 μm to 40–45 μm oval shape amastigote-like form, which is the product of a massive invagination process of the plasma membrane-cytoskeleton complex, leading to the formation of single membrane cytoplasmic vesicles surrounded by attached MTs, containing extracellular fluid. The overall process of cell membrane-microtubule complex invagination was completed within 72 h. The differentiation of L. mexicana in culture conditions was identical to that previously reported for promastigotes that were phagocyted by macrophages (Hernandez et al. 1981).

The plasma membrane self-invaginating process observed in our study resembles the autophagic-like processes described in higher eukaryotes directed at degrading damaged or redundant cell organelles (Meijer et al. 2007; Yan and Klionsky 2009; Yorimitzu and Klionsky 2005; Duszenko et al. 2011). We named this process a selective autophagic-like process of the plasma membrane, directed at degrading the redundant plasma membrane-MT complexes in response to temperature elevation and medium acidification mimicking the parasite invasion of macrophages within the mammalian host. The transformation into the amastigote form within macrophages is important for survival inside the macrophage and for virulence (Debrabant et al. 2004; Galvao-Quintao et al. 1990; Besteiro et al. 2006). In contrast, non-pathogenic Leishmania promastigotes are lysed inside the parasitophorous vesicle after engulfment by mammalian macrophages. An autophagic-like process has been previously described in trypanosomatid parasites (Herman et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2009; Brennand et al. 2012) that appears important in cellular remodeling during parasite differentiation throughout their life cycle stages (Brennand et al. 2011). Prior studies in Leishmania have shown the presence of glycosomes, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria fragments within autophagosomes (Cull et al. 2014). Furthermore, the importance of autophagy for differentiation and virulence of Leishmania was analyzed with respect to endosomal sorting (Besteiro et al. 2006) and the presence of endosomal markers such as Rab5b was also reported (Marotta et al. 2006). However, the specific morphological characteristics of the autophagic invagination process of the plasma membrane-MT complex described by ultrastructural analysis have not been reported elsewhere, at least to the best of our knowledge. This simplified model of in vitro differentiation of promastigotes into amastigote-like cells may not reproduce the complexity of the host-parasite interaction in nature. However, it offers the possibility to examine function and interaction of basic cell biology processes in Leishmania and could be a useful model to study the effect of drugs directed at blocking parasite differentiation and amastigote survival as new strategies to fight the disease.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ana Rascón for the critical reading of this manuscript. Our deep gratitude goes to Irene Dunia and Anne-Lise Haenni for the helpful discussions and critical revision of the final draft. We are indebted to Ilse Hurbain for the cell quantification assay. Finally, we thank the Centro de Microscopia Electrónica de la Facultad de Ciencias, UCV, Venezuela, for the electron microscope facilities.

References

- Barack E, Amin-Spector S, Gerliak E, et al. Differentiation of Leishmania donovani in host free system analysis of signal perception and response. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;141(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemantes C, Souza-Silva F, Dos Santos K, Santini B, et al. Increasing in cysteine proteinase B expression and enzymatic activity during in vitro differentiation of Leishmania (Vianna) braziliensis. First evidence of modulation during morphological transition. Biochimie. 2017;133:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besteiro, et al. Endosome sorting and autophagy are essential for differentiation and virulence of Leishmania major. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(16):11384–11396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegel D, Topper G, Rabinovitch N. Leishmania mexicana: temperature sensitivity of isolates amastigotes and amastigotes infecting macrophages in culture. Exp Parasitol. 1983;56(3):289–297. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(83)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennand A, Gualdron-Lopez M, Coppens L, Ridgen DJ, Ginger ML, Michels PA. Autophagy in parasitic protists: unique features and drug targets. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2011;177(2):83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennand A, Rico E, Michels PAM. Autophagy in Trypanosomatids. Cell. 2012;1(4):346–371. doi: 10.3390/cells1030346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Salinas J, Gonzalez-Rey E. Autophagy and neuropeptides at the crossroad for parasites: to survive or to die? Autophagy. 2009;5(4):551–554. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.4.8365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull B, Lima Prado J, Cola Fernandes J, et al. Glycosome turnover in Leishmania major is mediated by autophagy. Autophagy. 2014;10(12):2143–2157. doi: 10.4161/auto.36438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrabant A, Joshi MB, Pimenta F, Dwyer D (2004) Generation of Leishmania donovani axenic amastigotes: their growth and biological characteristics. Int J of Parasitology 34: 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Duszenko M, Ginger ML, Brennand A, Lopez G, Colombo MI, Coombs GH, et al. Autophagy in protists. Autophagy. 2011;7(2):127–157. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.2.13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eperon S, MacMahon-Pratt D. I. Extracellular cultivation and morphological characterization of amastigote like forms of Leishmania panamensis and Leishmania braziliensis. J Protozool. 1989;36(5):502–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1989.tb01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eperon S, MacMahon-Pratt D. II. Extracellular amastigote like forms of Leishmania panamensis and Leishmania braziliensis. II. Stage and species specific monoclonal antibodies. J Protozool. 1989;36(5):510–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1989.tb01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong D, Chang KP. Surface antigen changes during differentiation of parasitic protozoan Leishmania mexicana: identification by monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(23):7366–7376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvao-Quintao ASC, Ryter A, Rabinovitch M. Intracellular differentiation of Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes to amastigotes : presence of megasomes, cysteine protease activity and susceptibility to leucine methyl ester. Parasitology. 1990;101(01):7–13. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000079683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Klionsky Regulation mechanism and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43(1):67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman M, Gillies S, Michels PA, Ridgen DJ. Autophagy and related processes in trypanosomatids : insights from genome and bioinformatic analyses. Autophagy. 2006;2(2):107–118. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AG, Arguello C, Dagger F, Infante RB et al (1981) The surface membrane of Leishmania. In:Slutzky G (Ed) The biochemistry of parasites pp 47–65 Pergamon Press Oxford and New York

- Holzer TR, Mc Master WR, Forney JD. Expression profile by whole genome interspecies microarrays hybridization reveals differential gene expression in procyclic promastigotes, lesion derived amatigotes and axenic amastigotes in Leishmania mexicana. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;146(2):198–218. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnovsky MJ. A formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative of high osmolarity for use in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1965;27:137A–138B. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm J, Conville M, Nederer T. Metabolic pathways required for the intracellular survival of Leishmania. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;6:543–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta DE, Gerald N, Dwyer DM. Rab5b localization to early endosomes in the protozoan human pathogen Leishmania donovani Mol. Cel. Biochemist. 2006;292:107–117. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer WH, van der Klei IJ, Veenhuis M, Kiel JA. ATG genes involves in non-selective autophagy are conserved from yeast to man, but the selective CyT and pexophagy pathways also requires organism specific genes. Autophagy. 2007;3(2):106–116. doi: 10.4161/auto.3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte Neto R, Souza M, Diaz CS, et al. Morphological and physiological changes in Leishmania promastigotes induced by yangambin, a lignan obtained from Ocotea duckei. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127(1):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JL, Guevara P. The ribosomal gene spacer as a tool for the taxonomy of Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987;22(2-3):177–183. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson S, Sommer JR, Blum JJ. Morphology of Leishmania braziliensis: changes during reversible heat-induced transformation from promastigotes to ellipsoidal forms. J Parasitol. 1989;75(3):431–440. doi: 10.2307/3282602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler RJ, Gluenz E, Gull K. The cell cycle of Leishmania: morphogenetics events and their implications for parasite biology. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79(3):647–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RA, Woods K, Juliano L, Coombs GH. Characterization of unusual families of ATYG8-like proteins and ATG-12 in the protozoan parasite Leishmania major. Autophagy. 2009;5(2):159–172. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.2.7328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Klionsky DJ. An overview of the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;335:1–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorimitzu T, Klionsky DJ. Molecular machinery for self eating. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1542–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakay HA, et al. In vitro stimulation of metacyclogenesis in Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania donovani, Leishmania major and Leishmania mexicana. Parasitology. 1998;116(4):305–309. doi: 10.1017/S0031182097002382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilverstein D, Shapira M. The role of pH and temperature in the development of Leishmania parasites. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48(1):449–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]