Abstract

HIV infection is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). This risk is accentuated by certain combination antiretroviral therapies (cARTs), independent of their effects on lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. We sought to define potential mechanisms for this association through systematic review of clinical and preclinical studies of CVD in the setting of HIV/cART from the English language literature from 1989 to March 2018. We used PubMed, Web of Knowledge and Google Scholar, and conference abstracts for the years 2015–March 2018. We uncovered three themes: (1) a critical role for the HIV protease inhibitor (PI) ritonavir and certain other PI-based regimens. (2) The importance of platelet activation. Virtually all PIs, and one nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, abacavir, activate platelets, but a role for this phenomenon in clinical CVD risk may require additional postactivation processes, including: release of platelet transforming growth factor-β1; induction of oxidative stress with production of reactive oxygen species from vascular cells; suppression of extracellular matrix autophagy; and/or sustained proinflammatory signalling, leading to cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction. Cardiac fibrosis may underlie an apparent shift in the character of HIV-linked CVD over the past decade from primarily left ventricular systolic to diastolic dysfunction, possibly driven by cART. (3) Recognition of the need for novel interventions. Switching from cART regimens based on PIs to contemporary antiretroviral agents such as the integrase strand transfer inhibitors, which have not been linked to clinical CVD, may not mitigate CVD risk assumed under prior cART. In conclusion, attention to the effects of specific antiretroviral drugs on platelet activation and related profibrotic signalling pathways should help: guide selection of appropriate anti-HIV therapy; assist in evaluation of CVD risk related to novel antiretrovirals; and direct appropriate interventions.

Keywords: platelet activation, HIV, oxidative stress, cART, myocardial fibrosis

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the third most frequent non-AIDS cause of death in HIV+ individuals, and in those on combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), it is the leading cause.1 CVD is predicted to increase markedly with ageing among the HIV infected, presenting obstacles to a normal life span and contributing substantially to healthcare utilisation costs in resource-rich and resource-poor settings.2–5 These disorders affect all demographics, with an equivalent impact on paediatric and adult populations.1 5 In terms of gender, the US Veterans Aging Cohort Study established that, after adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, lipids, tobacco use, blood pressure, diabetes, renal disease, obesity, hepatitis and substance abuse, the HR for substantial cardiovascular (CV) events was 1.48 for all HIV-infected veterans (p<0.05)6 and 2.8 among female veterans (p<0.001).7

In defining the pathophysiology of the association between HIV and CVD, it is important to recognise that the magnitude of CVD risk in the HIV+/ART-naive is low. The large Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study found no increase in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the absence of antiretroviral therapy (ART).8 In contrast, this risk increased by 26% per year of ART exposure, despite the fact that blood pressure, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels and smoking did not change or declined.8 A very recent report from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) refined this risk, emphasising the importance of viral control in the setting of cART.9 There was a higher incidence and greater progression of low-attenuation, non-calcified high-risk plaque among HIV-infected men than age-matched controls over a median of 4.5 years. Failure of viraemic control for those on cART was an important correlate of plaque progression.9 These data have been incorporated into new models for assessment of the global risk of CVD in the setting of HIV, which have higher accuracy than classic Framingham equations. One model includes cumulative exposure to HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) as a class, or current use of the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor abacavir.10 Large observational cohorts document that cART based on other nucleoside or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors does not influence AMI incidence, and although integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based ART has not been in widespread use for periods sufficient to permit long-term follow-up, those agents also do not appear to influence CVD risk.1 11 12

We sought to define potential mechanisms for the impact of specific antiretroviral drugs on CVD risk in the setting of HIV through a systematic review of clinical and preclinical studies from the English language literature from January 1989 to March 2018. We used PubMed, Web of Knowledge and Google Scholar, and reviewed conference abstracts from major national and international HIV/AIDS conferences for years 2015–March 2018. We paid particular attention to recent PI-boosted regimens that substitute cobicistat for ritonavir (RTV),13 as well as two antiretroviral drugs, abacavir and the PI atazanavir, for which links to changes in clinical CVD risk remain controversial. We recognised that cART-mediated effects on lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, endothelial function, activation of monocytes and T cells, and the role of oxidative stress in initiation and maintenance of these metabolic and proinflammatory processes, all of which can affect vascular homeostasis and CVD risk, have been extensively reviewed1 14–18 and were not the main focus of our study. What has not received sufficient attention is the concept that these systems are differently impacted by individual antiretroviral agents, and the critical role of specific types of antiretroviral-mediated platelet activation with induction and maintenance of profibrotic pathways.

This information has practical clinical ramifications. Recent studies have noted the disparity in quality of cardiovascular care for HIV-infected versus uninfected individuals. When indicated, physicians were much less likely to prescribe aspirin or other antiplatelet agents, or hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) to HIV-infected individuals (5.1% vs 13.8%, p=0.03 and 23.6% vs 35.8%, p<0.01, respectively).19 Findings on the underutilisation of statins were replicated among 3453 HIV-infected women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study20 and among a diverse population of 3312 HIV+ individuals in the dialated cardiomyopathy (DC) cohort.21 It was speculated that most HIV patient visits focus on control of HIV viraemia to the detriment of preventive CV care19 but, as highlighted here, the two areas are intimately linked.

Impact of cART on CVD risk: classes of ART versus individual antiretroviral agents

There are no prospective, randomised trials to document a causative relationship between cART in general, or a specific antiretroviral agent, and CVD. However, the fact that the association between CVD and use of only certain PIs is reproducible in multiple, large and diverse observational cohorts (table 1)6 11 17 18 22–26 28 29 and is characterised by a slowly increasing risk as cumulative exposure to these antiretrovirals increases,18 ‘reduces—albeit does not remove—the risk that unknown or unmeasured confounders that could not be adjusted for might explain the association’, in the conclusion of one group.18 Data from preclinical models, derived from our lab and others, support this interpretation, as discussed below.

Table 1.

Assessment of clinical cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in HIV-infected adults in association with protease inhibitors (PIs) as a class and as individual PIs

| Citation | Study | No. of HIV+ patients |

No. of HIV controls | CVD risk assessed | HR, PI use as a class | HR, PI use by individual drugs |

Description of study type |

| Ref 6 | Veterans Aging Study, Virtual Cohort | 27 168 | 55 109 | AMI | 1.34 (p=0.06) | Controlled for traditional CVD risk factors. |

|

| Ref 25 | Meta-analysis to 2010 | ACS and CVA risk/year. AMI risk/year. |

1.10 (1.05–1.17). 1.41 (1.20–1.65). |

||||

| Ref 26 | Meta-analysis, 11 studies | 2442 | ACS, AMI risk at 25.5 months | 2.68 (1.89–3.89) | |||

| Ref 22 | Veteran Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative | 36 766 | AMI and CVA | 1.23 (0.78–1.93) (p=0.57) | Years 1993–2001, retrospective, 40 months f/u; 23.9% diabetes, HTN, ↑lipids, tobacco. |

||

| Ref 23 | Veteran Ageing Cohort Study | 31 523 | 66 492 | Heart failure with ejection fraction | NS elevated versus no ART: PI: 1.80 (1.19–2.75). NNRTI: 1.48 (1.01–2.15). |

||

| Ref 11 | D:A:D | 23 437 | AMI/1000 person-years | No PI: 1.00 >6years: 1.10. | Adjusted for lipids. | ||

| Ref 28 | D:A:D | ATV: 9611. ATV/r: 37 005. |

AMI/overall risk/year. CVA/overall risk/year. |

ATV: 0.80 (0.61–1.03); ATV/r: 0.99 (0.90–1.08) NS. ATV: 0.80 (0.61–1.03); ATV/r: 1.02 (0.98–1.06) NS. |

|||

| Ref 30 | D:A:D | 35 711 | CVD IRR/5 years | IDV 1.47; LPV/r 1.54. DRV/r 1.53 (1.28–1.84). ATV/r 1.0 (0.88–1.16) NS. |

|||

| Ref 18 | French Hospital Database | 289 | 884 | AMI/overall risk/year | 1.53 (1.21–1.94) | Amprenavir/LPV/r fosamprenavir±/r 1.56 (1.21–2.01). LPV/r: 1.34 (1.09–1.64). IDV: NS. SQV/r: NS. |

|

| Ref 17 | Meta-analysis | Eight studies to 2011 | AMI/overall risk/year | 2.13 (1.06–4.28) | ↑Relative risk/year of exposure: IDV/r: 1.11 (1.05–1.17). LPV/r: 1.22 (1.01–1.47). |

||

| Ref 24 | RAMQ | 7053 | 27 681 | AMI/overall risk/year | LPV: 1.98 (1.24–3.16). RTV: 2.29 (1.48–3.51). |

HRs are statistically significant unless otherwise indicated.

Antiretroviral drug abbreviations: ATV, atazanavir; DRV, darunavir; IDV, indinavir; LPV, lopinavir; RTV, ritonavir; SQV, saquinavir; r: ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ART, antiretroviral therapy, CVA, cerebrovascular accident; D:A:D, Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs; f/u, follw up; HTN, hypertension; IRR, incident rate ratio; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NS, not significant; RAMQ, Regie de l’assurance-maladie du Quebec.

Table 1 summarises the association of cART with CVD risk in adults. With one major exception, based on Veterans Affairs databases,22 23 large observational studies support the association of PIs versus other ART classes with increased CVD risk. All but one study powered to distinguish among specific PIs linked this risk to RTV, used alone or with certain other PIs, including lopinavir, indinavir, amprenavir, fosamprenavir and darunavir, in so-called PI-boosted regimens. Nearly all PIs are combined with low-dose RTV or, more recently, cobicistat, both of which inhibit cytochrome P450 3-mediated metabolism of PIs in the liver, resulting in increased plasma concentrations.13 Cobicistat-boosted regimens are not included in table 1 as they have not been in clinical use for sufficient periods to assess CVD risk, which would have enabled addressing the issue of whether it is the boosting of the principal PI or the boosting agent itself, which is responsible for some of the long-term side effects of such regimens. One phase III trial contrasting RTV-boosted versus cobicistat-boosted PIs found no variation in high/low density lipoprotein profiles or degree of bone mineral density loss over a 144-week follow-up period, but details of CVD assessment were not included.13 In any event, RTV-boosted PIs continue to be used worldwide, and in recent studies of contemporary two drug regimens in the USA, darunavir/RTV is one of the key components.29 In addition, observational studies suggest that switching from RTV-based or other PI-based cART to alternative drug classes may not mitigate CVD risk30 31 nor reduce existing arterial inflammation.32

In evaluating our pathophysiological model for cART-accelerated CVD based on the importance of platelet activation, it is also important to consider apparent contradictions. For example, the PI atazanavir and RTV-boosted atazanavir had no significant link to CVD (table 1), with one group suggesting a reduced risk for AMI with atazanavir exposure.33 However, these regimens are associated with heightened platelet activation.30 In addition, there is continued argument as to whether abacavir increases CVD risk; some treatment guidelines still suggest caution in its use in individuals with high Framingham CVD risk scores.1 12 15 34 Part of the controversy involving atazanavir concerns the role of residual confounders in analysis of a relatively small cohort.33 Indeed, coronary artery calcium scoring and coronary CT angiography documented an increase in any plaque in association with cumulative exposure to atazanavir (adjusted OR 1.66) or abacavir (adjusted OR 1.38),35 and this is reflected in our contrast of antiretroviral agents linked to an increase in clinical CVD risk as opposed to changes in surrogate markers for such disease (table 2). These issues are explored in our review of the impact of an individual antiretroviral agent on lipid profiles and platelet activation and on extracellular matrix (ECM) autophagy, macrophage polarisation and oxidative stress, all of which can contribute to, or protect against, cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction.

Table 2.

Effects of specific antiretroviral drugs on CVD risk and factors linked to accelerated CVD*

| Antiretroviral | CVD risk | ||||||

| ART class† | Clinical | Surrogate markers | Lipids | Platelet activation | Autophagy | ROS production | |

| Ritonavir (RTV) | PI | + | + | ↑ | + | Blocks | + |

| Lopinavir/RTV | PI | + | + | ↑ | + | Blocks | + |

| Darunavir/RTV | PI | + | + | +/− | + | Blocks | + |

| Atazanavir/RTV | PI | − | + | +/− | + | Induces | − |

| Atazanavir | PI | − | + | +/− | + | Induces | − |

| Abacavir | NRTI | +/− | + | − | + | Not tested | − |

| Raltegravir | INSTI | − | − | − | − | Not tested | − |

*Citations for these analyses are presented in the text. The methodology for assessment of platelet activation varied among studies.

†INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

The role of HIV/cART in modulating traditional CVD risk factors

The D:A:D Study Group concluded that the increase in AMI risk in the setting of HIV ‘may at least in part be explained by cART-induced changes in conventional risk factors. These findings [therefore] provide guidance in terms of choosing lifestyle or therapeutic interventions to decrease those risk factors’.11 Indeed, recent reviews have focused on modification of traditional risk factors, including diet and pharmacological treatment of hyperlipidaemia and inflammation with statins.1 15 Lipid abnormalities are important in proinflammatory processes and atherosclerosis, and both hypercholesterolaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia increase platelet activation,36 which could promote a proinflammatory, procoagulant and profibrotic state regardless of HIV infection or cART use. RTV and darunavir impact platelet function in a manner comparable with tobacco smoke and may synergise with smoking in promotion of a hypercoaguable state.37 With reference to fibrosis, a cross-sectional study of HIV-infected adults on cART documented normal ejection fractions but subclinical systolic dysfunction in association with myocardial steatosis and diffuse myocardial fibrosis.38 (There was no association between exposure to specific classes of ART and intramyocardial lipid content or fibrosis, but specific PIs were not examined.) The authors stated that these observations ‘suggest’ that cardiac fibrosis may simply be secondary to the downstream metabolic effects of HIV infection.38

However, review of 4685 participants from 35 countries in the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) trial, a randomised study of immediate versus deferred cART initiation among HIV-infected individuals with CD4+ T cell counts in the normal range (>500 cells/mm3), concluded that the net effect of cART on traditional CVD risk ‘may be clinically insignificant’, at least in the short term, with a mean follow-up of 3.0 years.39 In fact, cART had opposing effects on serum lipids in START, increasing total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and also increasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and decreasing the need for blood pressure medication.39 While accelerated CVD risk linked to RTV, used alone or at much lower doses in many RTV-boosted PI regimens, is accompanied by changes in lipid metabolism,14 18 hyperlipidaemia was not a factor in the high CVD risk related to darunavir/RTV in humans,18 and RTV-driven cardiac disease could be dissociated from hyperlipidaemia in two rodent models.40 41 While lipid profiles were minimally altered, to similar levels, with RTV-boosted darunavir and atazanavir,42 the link to heightened risk for clinical CVD is much greater with the former regimen.18 28

Surrogate markers for CVD and biomarkers of inflammation and coagulopathy in HIV/cART

Circulating levels of immune and other cellular activation biomarkers in HIV-infected individuals vary widely with different antiretroviral regimens, complicating attempts to link these changes to CVD in the setting of HIV/cART. Such biomarker data may offer insight into the severity of cardiovascular-related outcomes in the setting of HIV and HIV/cART,43 but presently they are not reliable indicators of the impact of a specific ART regimen or antiretroviral drug on CVD risk.

For example, changes in plasma markers of inflammation, monocyte activation and coagulation among individuals starting cART within 6 months of HIV infection in AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol A5217 found d-dimer levels, an indication of a hypercoaguable state, lowered on viral suppression (p=0.031) but high-sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP), a marker of inflammation, and monocyte sCD14 levels were unchanged regardless of regimen.44 In another study, only hsCRP correlated directly with advancing carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT).45 Integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimens led to greater decreases in sCD14, hsCRP and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, a marker of vascular inflammation, compared with a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase-based regimen, but interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)-receptor 1 and another monocyte activation marker, sCD163, were unaltered.46 There was a decline in IL-6 and sCD14 on integrase strand transfer inhibitor but not PI-based ART, but levels of sCD163 and hsCRP did not differ between treatments.47 In the Switching From PI to RALtegravir in HIV Stable Patients (SPIRAL) study of 273 HIV+ individuals switched from RTV-boosted PIs to integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based cART, there were declines in hsCRP, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, osteoprotegerin, IL-6, TNF-α and d-dimers, with magnitudes ranging from 8% for d-dimers to 40% for hsCRP and 46% for IL-6.31 However, there were no significant changes in related biomarkers, including IL-10, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), E-selectin and P-selectin.31 Another procoagulant marker, tissue factor (TF), is also elevated following HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus infection, and levels are not normalised in the setting of cART.48

In terms of biomarker correlations with functional measures of preclinical CVD, elevated levels of sCD163, sCD14 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 were associated with subclinical atherosclerosis based on coronary CT angiography in one MACS study.49 However, there was only a very modest level of correlation among these monocyte markers. Baseline sCD14 levels correlated with CIMT progression in the setting of HIV,49 50 though cART, regardless of class, did not influence these levels.31 46 In addition, absolute levels of HIV in cART-treated individuals did not correlate with many biomarkers of inflammation or CVD risk.47

These studies indicate that current biomarker datasets are insufficient for evaluation of HIV-related CVD risk. For example, in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, elevated hsCRP was positively associated with focal plaque progression in HIV-uninfected women, with a relative risk of 6.0, but this was not the case for their cohort of HIV-infected women.51 The investigators concluded that ‘subclinical CVD pathogenesis may be different in HIV-infected women’.51

Biomarkers more specific for fibrosis may be of clinical value to assessing the importance of cardiac fibrosis in HIV/cART-linked CVD. Although markers of inflammation and immune activation did not correlate with an MRI-based myocardial fibrosis index of HIV-infected individuals on cART,52 elevation of plasma factors linked to pathological cardiac fibrosis in the general population, including soluble ST2, an IL-1 receptor family member and biomarker of cardiomyocyte stretch, galectin-3, and growth differentiation factor 15, a transforming growth factor (TGF)-β superfamily member,53 54 have been linked to CVD among HIV+ populations.18 Plasma TGF-β1 levels are similarly increased twofold in HIV+/ART-naïve asymptomatic individuals, with a further rise in advancing disease, and this is not suppressed by cART.55 56 Levels of a classic marker of oxidative stress, plasma F2-isoprostane, also correlate with CVD and other serious metabolic events in HIV/cART patients, with a sensitivity of 95.3% and a specificity of 49.6%.57 Similarly, RTV-induced cardiac dysfunction in rats correlated with a 50% increase in the plasma F2-isoprostane 8-isoprostane over controls.40 Median F2-isoprostane levels are significantly lower in virally suppressed HIV+ patients on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based cART versus other forms of cART, predominantly PI based.58

As noted above, correlations among many of these biomarkers, preclinical indicators of CVD and clinical cardiac dysfunction often do not reach significant levels. In terms of TGF-β1, an important caveat is the failure of many investigators, when collecting mouse or human blood, to use controls for ex vivo platelet activation with TGF-β1 secretion.59 60 The dichotomy in TGF-β1 levels between HIV negative controls and HIV-infected individuals with and without cART exposure may therefore be more prominent than reported in the literature. In addition, measures of the levels of functional TGF-β1, the activation product from its latent form, have not been assessed in the setting of HIV/cART and, as reviewed in the section on platelets, could be influenced by different antiretroviral agents. Finally, as discussed below, those PIs most closely linked clinically to accentuated CVD risk, and shown to promote platelet activation and proinflammatory and profibrotic signalling in vitro and in murine models by our group and others, may not act through alteration of circulating levels of these factors but rather by affecting their signalling pathways.

Defining the pathophysiology of HIV/cART-linked CVD: focus on platelet activation and cardiac fibrosis

Cardiac fibrosis has been documented in HIV-infected individuals with lower peak diastolic as well as systolic longitudinal strain38 and may underlie an apparent shift in character of HIV-associated CVD over the past decade from primarily left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction to LV diastolic dysfunction.16 61 In one study, 49% of HIV-infected subjects had evidence of diastolic dysfunction compared with 29% of uninfected controls (p=0.008), a difference that persisted after adjustment for hypertension.61 Only 4% of HIV-infected individuals had evidence of LV systolic dysfunction.61 The increase in LV mass was also highly significant for the HIV group (p=0.001).61 No association with ART class was found, but individual antiretroviral agents were not examined. In addition, the mechanisms underlying these changes were not explored, although subclinical atherosclerosis and infiltration of the myocardium with inflammatory cells were thought to be involved.61 These changes are consistent with our pathophysiologic model, as detailed below.

Further insight into the pathophysiology of diastolic and other CVD in the setting of HIV/cART should come from the recently announced Characterizing Heart Function on Antiretroviral Therapy study, which will include measures of myocardial fibrosis by cardiac magnetic resonance and biomarkers of fibrosis and oxidative stress.16 However, based on current knowledge, two points for intervention can be highlighted now: platelet activation and related signalling pathways for fibrosis and oxidative stress.

Although persistent platelet activation is well documented in the setting of HIV and HIV/cART,30 55 62 its role in pathological fibrosis-mediating CVD in these settings is rarely emphasised. The relationship of chronic platelet activation, directly or indirectly mediated by certain PIs, to CVD is consistent with the clinical association of only certain PI-based regimens with an accentuated risk of CVD. We focus on pathological cardiac and vascular fibrosis in relationship to platelet activation for the following reasons:

TGF-β1 is critical to initiation and maintenance of pathological fibrosis. We evaluated fibrosis and a canonical TGF-β1 signalling event, Smad2/3 phosphorylation, in autopsy hearts of ART-naïve HIV+ children.55 Deposition of collagen and increased phosphorylated Smad2 was seen, with a strong correlation between fibrosis score and pSmad2 staining.55 Simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques show cardiac dysfunction similar to that of HIV infection, in association with interstitial and vascular fibrosis and infiltration of cardiac tissue with proinflammatory macrophages.63 64

The role of TGF-β1 in development of CVD and other non-AIDS defining fibrotic disorders in the setting of HIV/cART is of increasing interest.55 65 66 Aortic arterial fibrosis is prominent in HIV-infected individuals versus controls and is not suppressed by cART.32 Focal and diffuse myocardial interstitial fibrosis is of high prevalence in the setting of HIV/cART16 38 52 67 and linked to LV diastolic dysfunction and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in these individuals.16 23

RTV induces LV fibrosis at pharmacological concentrations in ApoE−/− mice in conjunction with increased TGF-β1 in plasma and cardiac tissue, independent of RTV-associated alterations in lipid metabolism.41 Our group demonstrated decreased cardiac function and cardiac fibrosis in mice exposed to pharmacological doses of RTV daily for 8 weeks.68 Fibrosis correlated with plasma TGF-β1 levels and activation of both canonical (Smad2/3) and non-canonical (TAK1/MKK3/p38) TGF-β1 signalling pathways in the heart.68

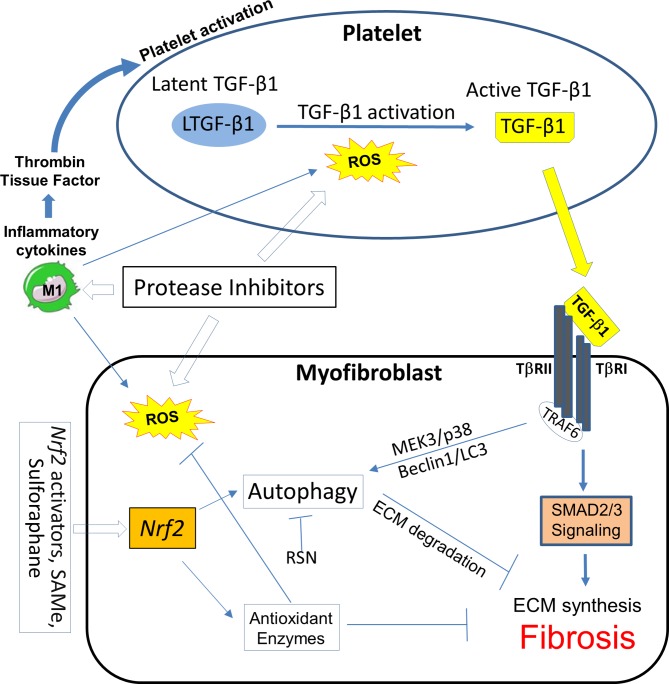

As shown in figure 1, under homeostatic conditions, synthesis of collagen and other ECM components, along with their degradation by macroautophagy, is mediated by TGF-β1 signalling through both canonical and non-canonical pathways.55 69 Autophagy is a prominent negative regulator acting through the latter pathway; the importance of RTV in this process was demonstrated by the fact that our group found that mice null for microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3−/−), and thus lacking autophagosomes, were particularly susceptible to RTV-induced cardiac fibrosis.68

Figure 1.

TGF-β1 regulates collagen synthesis and accumulation to maintain regulated extracellular matrix (ECM) production and deposition under physiological conditions. This involves positive signalling pathways initiating collagen synthesis mediated by the nuclear signalling adapter protein TRAF6 via Smad2,3 (canonical) and TAK1/MKK3/p38 (non-canonical) pathways. Mechanisms for collagen degradation via autophagy are linked to TAK1/MKK3/p38. TRAF6 is regulated via immunoproteasome degradation. TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1; TRAF6, tumour necrosis factor receptor- associated factor 6.

The critical role of the platelet in this system was defined by the fact that mice with targeted deletion of TGF-β1 only in megakaryocytes/platelets (PF4CreTgfb1flox/flox mice) were protected from RTV-induced cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis.68 Platelets contain 40–100 times the concentration of TGF-β1 as other cells, contributing the major fraction of circulating TGF-β1, and are key to clinical and other murine models of fibrosis with heart failure.60 69 70

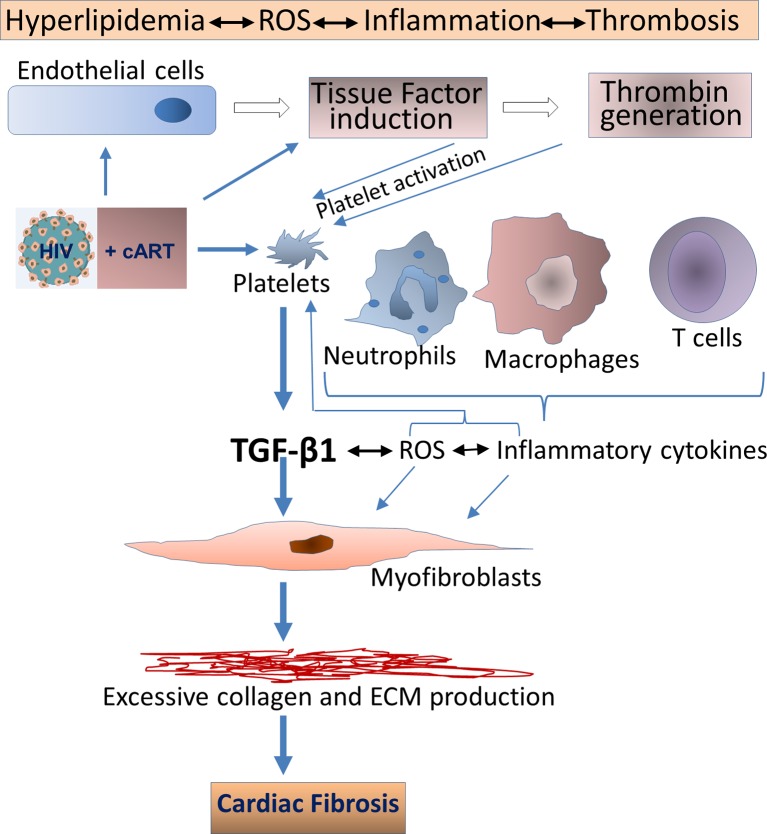

In terms of pathological fibrosis, HIV infection itself leads to increases in TGF-β1 levels, along with a variety of proinflammatory factors such as IL-6, IL-8 and TF. Inflammatory cytokines can induce TF in endothelial cells and monocytes/macrophages, mediating thrombin generation, thereby activating platelets via protease-activated receptors. This leads to persistent inflammation and continued platelet activation, with TGF-β1 release.69 71 72 As illustrated in figure 2, other cells involved in this inflammatory milieu, such as injured endothelial cells, monocytes/macrophages, along with activated platelets, also contribute to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. This establishes a positive feedback loop with platelet activation for the transition of latent to active TGF-β1, as ROS is a potent activator of latent TGF-β1.69

Figure 2.

HIV infection leads to increases in TGF-β1 levels, which may induce pathologic cardiac fibrosis. Active TGF-β1 upregulation can occur through various mechanisms, including direct binding of HIV envelope to platelets, induction of IL-6 and IL-8 and induction of tissue factor and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Other cells involved in this inflammatory milieu, may also contribute to TGF-β release. cART may mitigate, but not abolish, these perturbations. In addition, certain antiretroviral therapies, particularly those based on protease inhibitors, may accelerate cardiac fibrosis via direct activation of platelets. Metabolic disturbances linked to HIV and certain cART regimens may contribute to these pathological processes as, for example, cART-linked hyperlipidaemia can activate platelets. cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β.

In terms of the involvement of cART, RTV, many other PIs and abacavir can directly activate platelets.30 37 55 62 68 73 74 RTV, and certain other PIs, can also elevate mRNA expression for markers of oxidative stress, including IL-8, TNF-α and inducible haem oxygenase-1, when compared with the integrase strand transfer inhibitor raltegravir, which has not been implicated in CVD.75–77 Macrophage polarisation may also be involved through upregulation of M1 inflammatory subsets with production of procoagulant TF,48 55 in concert with loss of M2c regulatory macrophages acting via upregulation of regulatory T cells and TAK1/MKK3/p38 signalling with promotion of autophagy.68

Our group, and others, has also suggested interconnected roles for ubiquitin-proteasome systems with oxidative stress and dysregulation of redox in HIV and cART-linked CVD.68 78 79 Traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis, including tobacco, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance are associated with increased production of ROS, which have adverse effects on endothelial cell and platelet function14 69 77 (figure 2). Heightened ROS generation occurs early in HIV infection and persists despite many cART regimens79 (figure 2). ROS is an important aspect of CVD risk as cardiomyocytes are abundant in phospholipids, which are highly sensitive to oxidative stress.68 Such stress is also extremely efficient in converting latent TGF-β1 into its active, profibrotic form.69 As certain PIs could trigger ROS production through platelet activation, altered lipid metabolism and inhibition of ECM autophagy,68 69 80 we proposed a positive feedback loop by which HIV and certain PIs drive increases in ROS, in turn activating TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), a nuclear signalling adapter protein and ubiquitin E3 ligase, promoting TGF-β1 signalling (figure 1).55 68 This pathway has been shown, in other models, to exacerbate pathological cardiac hypertrophy via TAK1/MKK3/p38-dependent signalling.81

Finally, the signalling activity of TGF-β1, but not its plasma concentration, may be enhanced by ART-mediated facilitation of TRAF6 activity through specific inhibition of immunoproteasome function, with resultant suppression of TRAF6 degradation. Certain PIs, including RTV, block immunoproteasome formation at low pharmacological concentrations, while having no effect on the constitutive proteasome unless suprapharmacological, often cytotoxic, concentrations are employed.82 83 As TRAF6 is regulated through the immunoproteasome, such blockade would impede degradation of TRAF6, accelerating cytokine pathways dependent on this molecule. We demonstrated this in dissecting the mechanism of RTV-based acceleration of bone mineral loss in postmenopausal women treated with PI-based versus other cART regimens.82 84 RTV facilitated differentiation of monocytes into bone resorbing osteoclasts induced by RANKL. RANKL is the obligate cytokine for osteoclastogenesis and signals via TRAF6-related pathways. This occurred in association with prolongation of TRAF6 half-life, in the absence of changes in RANKL levels in RTV-treated individuals. As TGF-β1 and IL-6 and IL-8, inducers of TGF-β1, are also regulated by TRAF6, RTV-mediated interference with the immunoproteasome could lead to increased collagen accumulation mediated through the TAK1/MKK3/p38 pathway (figure 1). TRAF6 is known to exacerbate pathological cardiac hypertrophy and a variety of other cardiovascular disorders and appears to be a drugable target in treating CVD incurred by inflammatory processes.81 85

The role of autophagy in this system awaits further investigation. TRAF6-mediated potentiation of TAK1/MKK3/p38-associated autophagy and ROS induction of autophagy could be promoted by ART, but accompanying nitrosative stress with induction of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) can inhibit autophagy via S-nitrosylation and subsequent blockade of transcription factors that regulate Beclin 1, a component, along with LC3, of the autophagasome.69

Distinguishing features of antiretrovirals correlated with accelerated CVD

Based on our pathophysiological scheme, RTV should have a prominent role in clinical CVD and cardiac fibrosis as it can directly activate platelets and promotes pathological cardiac fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction in mice exposed to pharmacological levels of drug, acting through upregulation of TGF-β1 signalling. In contrast, individuals receiving the integrase strand transfer inhibitor raltegravir have platelets exhibiting markedly lower levels of platelet activation, at least as measured by expression of P-selectin on adenosine diphosphate (ADP) stimulation, when compared with other antiretrovirals,86 and raltegravir has not been implicated in accentuating CVD (table 2). However, the correlation between ART-linked platelet activation and clinical CVD risk is more nuanced.

For example, abacavir also activates platelets,73 yet as noted earlier, data linking abacavir to clinical CVD are conflicting.1 15 33 In terms of the PIs, cumulative exposure to lopinavir/RTV or darunavir/RTV is associated with an increased incidence of AMI, but atazanavir/RTV is not,18 28 87 even though atazanavir has been linked to platelet activation in vivo.30 As suggested above, lipid alterations cannot account for this difference; darunavir/RTV and atazanavir/RTV both cause similar, minimal changes in lipids.39 42Unrecognised confounding factors may be involved. There are many more patients followed for much longer periods on older PIs than atazanavir, and use of atazanavir, alone or with RTV-boosting has been recently linked to subclinical coronary artery disease.33 35 Other mitigating factors may also mitigate the platelet activation response.

One major issue is that the systems in which these platelet studies were performed, and the read-out for ‘activation’, are not uniform. The intensity of these effects among specific antiretrovirals, and their character, particularly with reference to release of latent or active forms of platelet TGF-β1, remain to be characterised. In addition, the mechanism(s) by which they activate platelets is unclear. Several pathways may be involved, including generation of systemic ROS and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8, thrombin and other coagulation factors and TF, which are strong platelet activators. We showed that even very low levels of RTV (<1 µM) alone can directly activate platelets and lead to release of latent TGF-β1,55 as well as elevate total TGF-β1 levels in plasma of RTV-exposed mice.68 However, active TGF-β1 levels could not be detected in our system (unpublished data) perhaps due to its very rapid clearance.59 Furthermore, in vitro models for platelet activation may not accurately reflect the situation in vivo, where interactions among divergent cell populations and platelets can contribute to platelet activation and release of active TGF-β188 89 (figure 2). These aspects need to be further studied in the setting of HIV/cART.

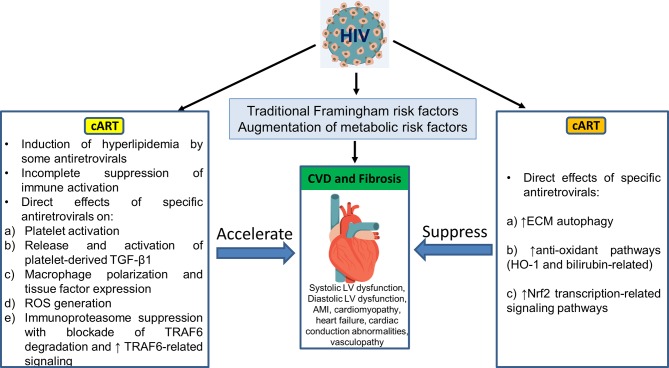

In addition, as summarised in figure 3, a single antiretroviral agent may demonstrate positive and negative influences on the pathophysiological pathways outlined in figure 2 and figure 4. Those antiretrovirals linked clinically to heightened CVD incidence appear to enhance the high-risk factors. Using atazanavir as an example, this PI directly activates platelets and so may release platelet TGF-β1 as does RTV. However, atazanavir is also a strong inducer of autophagy,90 elevates antioxidant bilirubin-linked pathways18 and does not induce ROS release from macrophages,76 while RTV and other PIs linked to CVD do not promote autophagy, may block autophagy-based degradation of collagen and other ECM components,68 and generate pro-oxidant ROS.76 Abacavir may directly activate platelets but, unlike many of the PIs, it does not induce oxidative stress in macrophages.76 (Its effects on autophagy have not been studied.) Such differences are catalogued for these are other antiretroviral drugs in table 2.

Figure 3.

Pathophysiology of CVD risk in association with cellular and metabolic pathways may be differentially affected by specific antiretroviral agents. Individuals drugs may be involved in pathways that primarily accelerate CVD risk, are neutral or decrease that risk. Certain antiretrovirals have positive and negative influences, thereby confounding attempts at prediction of impact on CVD risk. cART, combination antiretroviral therapy; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ECM, extracellular matrix; LV, left ventricle; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TRAF6, TNF receptor-associated factor 6.

Figure 4.

Pathways for intervention in HIV/cART-associated cardiac fibrosis in the platelet and the myofibroblast or other collagen-producing cells. Certain protease inhibitor therapies can activate platelets, induce ROS and suppress ECM autophagy. Positive feedback loops between ROS generation, platelet activation, M1 inflammatory macrophage subset polarisation and myofibroblast activity have been demonstrated. Oxidative stress characteristic of this milieu induces ROS, which may promote autophagy, and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) which can block it. Nrf2 activators may intervene in all of these pathways. ECM, extracellular matrix; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; ROS, reactive nitrogen species; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TRAF6, TNF receptor-associated factor 6.

Novel interventions in HIV/cART-associated cardiac fibrosis

We used our RTV-exposed cardiac fibrosis model in mice to explore novel interventions based on alterations of TGF-β1 signalling, autophagy and macrophage polarisation. We examined inhaled, low dose carbon monoxide (CO), a potent inducer of endogenous antioxidant and anti-inflammatory pathways acting via the leucine zipper transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2).68 Exposure of mice to RTV plus daily CO inhalations (250 ppm for 4 hours, five times/week) for 8 weeks led to suppression of cardiac fibrosis and Smad2 activation in conjunction with a decrease in proinflammatory M1 cells and a dramatic increase in the anti-inflammatory M2c subset in the heart, compared with RTV-exposed mice kept in ambient air.68 The CO-based changes in macrophage subsets in the heart are important to emphasise as, given the increasing attention to cardiac fibrosis in the setting of HIV/cART, TGF-β1 inhibition may seem a logical intervention. However, pan-neutralisation of TGF-β fails to suppress or reverse pathological fibrosis in many murine models and clinical trials.69 This lack of response may relate to divergent TGF-β1-dependent signalling pathways, which can either augment collagen synthesis or promote its degradation (figure 1), as well as production of low levels of TGF-β1 by regulatory M2c macrophage subsets, inducing anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells.

We then sought a more practical method to activate Nrf2 than inhaled CO. Nrf2 is a key regulator of the expression of genes coding for the majority of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory proteins affected by endogenous CO and inducible haem oxygenase and activated by exogenous CO.91 In endothelial cells, the Nrf2 pathway serves as a mechanosensitive regulator of redox signalling, suppressing TGF-β1 activation that may be induced by shear flow forces.92 Such forces might come into play in the setting of HIV-linked CVD. The Nrf2 pathway also has a protective role in atherosclerosis, consistent with its suppression of NADP(P)H oxidase (NOX)4, which can injure endothelium.93 The orally bioavailable Nrf2 activator S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe), the main endogenous methyl donor,94 could prevent and treat ethanol-associated and lipid-associated hepatic fibrosis and asthma-associated pulmonary fibrosis in mice.95 96 It is a potent inhibitor of platelet activation induced by a variety of agents in rodent and human blood97 and can block TGF-β1 signalling through the canonical Smad3 pathway.96 Several natural and synthetic compounds apart from SAMe, including sulforaphane, plant phenolics, triterpenoids such as bardoxolone methyl and itaconate are also potent Nrf2 activators.98 99 As depicted in figure 4, such agents could influence multiple pathways involved in HIV/cART-linked CVD.

Conclusions

Our review illuminates the critical role of RTV and certain other PIs as specific antiretrovirals involved in accentuating CVD risk in the setting of HIV. Limitations to definitively establishing those associations, and their mechanisms of action, include the lack of randomised clinical trials with the power to dissect effects of specific antiretroviral drugs on clinical CVD and surrogate markers for such disorders, as well as the failure to use standardised methodology to assess platelet activation, oxidative stress and cytokine production linked to profibrotic pathways in association with those agents.

Probable mechanisms by which a specific antiretroviral could induce CVD include:

Platelet activation, with secretion of latent TGF-β1 and its subsequent activation, perpetuation of a positive feedback loop involving ROS generation, and induction of fibrosis.

Suppression of TRAF6 degradation through effects on immunoproteasome formation, thereby prolonging signalling events related to proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokines and ROS, even if circulating levels of these factors are unperturbed.

Inhibition of ECM autophagy, exacerbating the profibrotic effects of TGF-β1 signalling.

Macrophage polarisation, increasing proinflammatory subsets and decreasing regulatory cells.

In terms of intervention in HIV/cART-linked CVD, our review suggests that:

Use of statins to mitigate the cardiovascular impact of certain antiretroviral drugs may have a limited impact. The Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) trial will address whether pitavastatin can prevent vascular events in HIV+ individuals without known CVD.100 However, in terms of the lipid-modifying action of statins, lopinavir/RTV is linked to hyperlipidaemia while darunavir/RTV is not, yet both have been implicated in heightened CVD risk. The impact of statins on PI-mediated oxidative stress and attendant endothelial cell injury, documented in vitro, could play a role,77 although a retrospective analysis of cART-treated HIV+ individuals from the Nutrition for Healthy Living cohort found that statins had no effect on incidence of myocardial infarction or stroke.101

A recent commentary advised that ‘Low CVD risk antiretrovirals should be considered and prescribed whenever possible’.12 We advocate creating a summary of the effects of a given antiretroviral drug on the parameters listed in table 2 and figure 3 to help assess the levels of such risk.

Novel interventions in HIV/cART-linked CVD, based on promotion of antioxidant pathways such as those linked to activation of Nrf2, should be pursued.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors drafted the review.

Funding: Financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health grants R21 HL125044 (JL and JA) and R01 HL123605 (JA), and the Angelo Donghia Foundation (JL). National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant GM114731), and National Cancer Institute (grant CA213987).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Zanni MV, Schouten J, Grinspoon SK, et al. Risk of coronary heart disease in patients with HIV infection. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014;11:728–41. 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Causes of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996-2006: collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studies. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:1387–96. 10.1086/652283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyd MA, Mocroft A, Ryom L, et al. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) event rates in HIV-positive persons at high predicted CVD and CKD risk: A prospective analysis of the D:A:D observational study. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002424 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gallant J, Hsue P, Budd D, et al. Healthcare utilization and direct costs of noninfectious comorbidities in HIV-infected patients in the USA. Curr Med Res Opin 2017:1383889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rajasuriar R, Chong ML, Ahmad Bashah NS, et al. Major health impact of accelerated aging in young HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2017;31:1393–403. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:614–22. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Womack JA, Chang CC, So-Armah KA, et al. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease in women. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e001035 10.1161/JAHA.114.001035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Law MG, Friis-Moller N, El-Sadr WM, et al. The use of the Framingham equation to predict myocardial infarctions in HIV-infected patients: comparison with observed events in the D:A:D Study. HIV Med 2006;7:218–30. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00362.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Post W, Haberlen S, Zhang L, et al. HIV infection is associated with progression of high risk coronary plaque in the MACS. Boston, MA: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 2018. Abst 77. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Friis-Møller N, Ryom L, Smith C, et al. An updated prediction model of the global risk of cardiovascular disease in HIV-positive persons: The Data-collection on Adverse Effects of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:214–23. 10.1177/2047487315579291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1723–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa062744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hatleberg CI, Lundgren JD, Ryom L. Are we successfully managing cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV? Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2017;12:594–603. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. von Hentig N. Clinical use of cobicistat as a pharmacoenhancer of human immunodeficiency virus therapy. Hiv Aids 2016;8:1–16. 10.2147/HIV.S70836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Teer E, Essop MF. HIV and Cardiovascular Disease: Role of Immunometabolic Perturbations. Physiology 2018;33:74–82. 10.1152/physiol.00028.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cerrato E, Calcagno A, D’Ascenzo F, et al. Cardiovascular disease in HIV patients: from bench to bedside and backwards. Open Heart 2015;2:e000174 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Butler J, Kalogeropoulos AP, Anstrom KJ, et al. Diastolic Dysfunction in Individuals With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: Literature Review, Rationale and Design of the Characterizing Heart Function on Antiretroviral Therapy (CHART) Study. J Card Fail 2018;24:255–65. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bavinger C, Bendavid E, Niehaus K, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease from antiretroviral therapy for HIV: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e59551 10.1371/journal.pone.0059551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lundgren J, Mocroft A, Ryom L. Contemporary protease inhibitors and cardiovascular risk. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018;31:8–13. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ladapo JA, Richards AK, DeWitt CM, et al. Disparities in the Quality of Cardiovascular Care Between HIV-Infected Versus HIV-Uninfected Adults in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e007107 10.1161/JAHA.117.007107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Todd JV, Cole SR, Wohl DA, et al. Underutilization of Statins When Indicated in HIV-Seropositive and Seronegative Women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:447–54. 10.1089/apc.2017.0145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levy ME, Greenberg AE, Magnus M, et al. Evaluation of Statin Eligibility, Prescribing Practices, and Therapeutic Responses Using ATP III, ACC/AHA, and NLA Dyslipidemia Treatment Guidelines in a Large Urban Cohort of HIV-Infected Outpatients. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018;32:58–69. 10.1089/apc.2017.0304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bozzette SA, Ake CF, Tam HK, et al. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients treated for human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 2003;348:702–10. 10.1056/NEJMoa022048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Freiberg MS, Chang CH, Skanderson M, et al. Association Between HIV Infection and the Risk of Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction and Preserved Ejection Fraction in the Antiretroviral Therapy Era: Results From the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:536–46. 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Durand M, Sheehy O, Baril JG, et al. Association between HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, and risk of acute myocardial infarction: a cohort and nested case-control study using Québec’s public health insurance database. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;57:245–53. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821d33a5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Islam FM, Wu J, Jansson J, et al. Relative risk of cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HIV Med 2012;13:453–68. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.00996.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. D’Ascenzo F, Cerrato E, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Acute coronary syndromes in human immunodeficiency virus patients: a meta-analysis investigating adverse event rates and the role of antiretroviral therapy. Eur Heart J 2012;33:875–80. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, et al. Impact of individual antiretroviral drugs on the risk of myocardial infarction in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1228–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Monforte A, Reiss P, Ryom L, et al. Atazanavir is not associated with an increased risk of cardio- or cerebrovascular disease events. AIDS 2013;27:407–15. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b2ef1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tieu HV, Taylor BS, Jones J, et al. CROI 2018: Advances in Antiretroviral Therapy. Top Antivir Med 2018;26:40–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van der Heijden WA, Bosch M, van Crevel R, et al. A switch to raltegravir does not lower platelet reactivity in HIV-infected patients. Seattle, WA: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 2017. Abst 610. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martínez E, D’Albuquerque PM, Llibre JM, et al. Changes in cardiovascular biomarkers in HIV-infected patients switching from ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors to raltegravir. AIDS 2012;26:2315–26. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359f29c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zanni MV, Toribio M, Robbins GK, et al. Effects of Antiretroviral Therapy on Immune Function and Arterial Inflammation in Treatment-Naive Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:474–80. 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Currier JS, Havlir DV. CROI 2018: Complications of HIV infection and antiretroviral Therapy. Top Antivir Med 2018;26:22–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raposeiras-Roubín S, Triant V. Ischemic Heart Disease in HIV: An In-depth Look at Cardiovascular Risk. Revista Española de Cardiología 2016;69:1204–13. 10.1016/j.rec.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kovari H, Calmy A, Doco-Lecompte T, et al. Antiretroviral drugs associated with subclinical coronary artery disease. Boston, MA: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 2018. Abst 670. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang N, Tall AR. Cholesterol in platelet biogenesis and activation. Blood 2016;127:1949–53. 10.1182/blood-2016-01-631259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loelius SG, Lannan KL, Casey AE, et al. Antiretroviral drugs and tobacco smoke dysregulate human platelets: a novel investigation into the etiology of HIV co-morbid cardiovascular disease. J Immunol 2017;198(S125). Abst 10. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holloway CJ, Ntusi N, Suttie J, et al. Comprehensive cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy reveal a high burden of myocardial disease in HIV patients. Circulation 2013;128:814–22. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baker JV, Sharma S, Achhra AC, et al. Changes in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors With Immediate Versus Deferred Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation Among HIV-Positive Participants in the START (Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment) Trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e004987 10.1161/JAHA.116.004987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mak IT, Kramer JH, Chen X, et al. Mg supplementation attenuates ritonavir-induced hyperlipidemia, oxidative stress, and cardiac dysfunction in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2013;305:R1102–R1111. 10.1152/ajpregu.00268.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cipriani S, Francisci D, Mencarelli A, et al. Efficacy of the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc in reducing early, ritonavir-induced atherogenesis and advanced plaque progression in mice. Circulation 2013;127:2114–24. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carey D, Amin J, Boyd M, et al. Lipid profiles in HIV-infected adults receiving atazanavir and atazanavir/ritonavir: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:1878–88. 10.1093/jac/dkq231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nordell AD, McKenna M, Borges ÁH, et al. Severity of cardiovascular disease outcomes among patients with HIV is related to markers of inflammation and coagulation. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000844 10.1161/JAHA.114.000844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Macatangay BJ, Yang M, Sun X, et al. Brief Report: Changes in Levels of Inflammation After Antiretroviral Treatment During Early HIV Infection in AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5217. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75:137–41. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ross AC, Rizk N, O’Riordan MA, et al. Relationship between inflammatory markers, endothelial activation markers, and carotid intima-media thickness in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:1119–27. 10.1086/605578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hileman CO, Kinley B, Scharen-Guivel V, et al. Differential Reduction in Monocyte Activation and Vascular Inflammation With Integrase Inhibitor-Based Initial Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV-Infected Individuals. J Infect Dis 2015;212:345–54. 10.1093/infdis/jiv004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gandhi RT, McMahon DK, Bosch RJ, et al. Levels of HIV-1 persistence on antiretroviral therapy are not associated with markers of inflammation or activation. PLoS Pathog 2017;13:e1006285 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schechter ME, Andrade BB, He T, et al. Inflammatory monocytes expressing tissue factor drive SIV and HIV coagulopathy. Sci Transl Med 2017;9:eaam5441 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam5441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McKibben RA, Margolick JB, Grinspoon S, et al. Elevated levels of monocyte activation markers are associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in men with and those without HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2015;211:1219–28. 10.1093/infdis/jiu594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kelesidis T, Kendall MA, Yang OO, et al. Biomarkers of microbial translocation and macrophage activation: association with progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2012;206:1558–67. 10.1093/infdis/jis545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moran CA, Sheth AN, Mehta CC, et al. The association of C-reactive protein with subclinical cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women. AIDS 2018;32:1–1006. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thiara DK, Liu CY, Raman F, et al. Abnormal Myocardial Function Is Related to Myocardial Steatosis and Diffuse Myocardial Fibrosis in HIV-Infected Adults. J Infect Dis 2015;212:1544–51. 10.1093/infdis/jiv274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Secemsky EA, Scherzer R, Nitta E, et al. Novel Biomarkers of Cardiac Stress, Cardiovascular Dysfunction, and Outcomes in HIV-Infected Individuals. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:591–9. 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fitch KV, DeFilippi C, Christenson R, et al. Subclinical myocyte injury, fibrosis and strain in relationship to coronary plaque in asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals. AIDS 2016;30:2205–14. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ahamed J, Terry H, Choi ME, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1-mediated cardiac fibrosis: potential role in HIV and HIV/antiretroviral therapy-linked cardiovascular disease. AIDS 2016;30:535–42. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liovat AS, Rey-Cuillé MA, Lécuroux C, et al. Acute plasma biomarkers of T cell activation set-point levels and of disease progression in HIV-1 infection. PLoS One 2012;7:e46143 10.1371/journal.pone.0046143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Masia M, Padilla S, Fernandez M, et al. Oxidative stress predicts serous non-AIDS events in HIV-infected patients. Seattle, WA: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 2017. Abst 647. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Redhage LA, Shintani A, Haas DW, et al. Clinical factors associated with plasma F2-isoprostane levels in HIV-infected adults. HIV Clin Trials 2009;10:181–92. 10.1310/hct1003-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mancini D, Monteagudo J, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. New methodologies to accurately assess circulating active transforming growth factor-β1 levels: implications for evaluating heart failure and the impact of left ventricular assist devices. Transl Res 2018;192:15–29. 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Meyer A, Wang W, Qu J, et al. Platelet TGF-β1 contributions to plasma TGF-β1, cardiac fibrosis, and systolic dysfunction in a mouse model of pressure overload. Blood 2012;119:1064–74. 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Ho JE, et al. Impact of HIV infection on diastolic function and left ventricular mass. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:132–9. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.854943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mayne E, Funderburg NT, Sieg SF, et al. Increased platelet and microparticle activation in HIV infection: upregulation of P-selectin and tissue factor expression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;59:340–6. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182439355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shannon RP, Simon MA, Mathier MA, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy associated with simian AIDS in nonhuman primates. Circulation 2000;101:185–93. 10.1161/01.CIR.101.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Walker JA, Sulciner ML, Nowicki KD, et al. Elevated numbers of CD163+ macrophages in hearts of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected monkeys correlate with cardiac pathology and fibrosis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014;30:685–94. 10.1089/aid.2013.0268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Theron AJ, Anderson R, Rossouw TM, et al. The Role of Transforming Growth Factor Beta-1 in the Progression of HIV/AIDS and Development of Non-AIDS-Defining Fibrotic Disorders. Front Immunol 2017;8:e01461 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hsue PY, Tawakol A. Inflammation and Fibrosis in HIV: Getting to the Heart of the Matter. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:e004427 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.004427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Luetkens JA, Doerner J, Schwarze-Zander C, et al. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Reveals Signs of Subclinical Myocardial Inflammation in Asymptomatic HIV-Infected Patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:e004091 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.004091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Laurence J, Elhadad S, Robison T, et al. HIV protease inhibitor-induced cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis is mediated by platelet-derived TGF-β1 and can be suppressed by exogenous carbon monoxide. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187185 10.1371/journal.pone.0187185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ahamed J, Laurence J. Role of Platelet-Derived Transforming Growth Factor-β1 and Reactive Oxygen Species in Radiation-Induced Organ Fibrosis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017;27:977–88. 10.1089/ars.2017.7064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ahamed J, Burg N, Yoshinaga K, et al. In vitro and in vivo evidence for shear-induced activation of latent transforming growth factor- 1. Blood 2008;112:3650–60. 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ahamed J, Belting M, Ruf W. Regulation of tissue factor-induced signaling by endogenous and recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor 1. Blood 2005;105:2384–91. 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ahamed J, Versteeg HH, Kerver M, et al. Disulfide isomerization switches tissue factor from coagulation to cell signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:13932–7. 10.1073/pnas.0606411103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Satchell CS, O’Halloran JA, Cotter AG, et al. Increased platelet reactivity in HIV-1-infected patients receiving abacavir-containing antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2011;204:1202–10. 10.1093/infdis/jir509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kort JJ, Aslanyan S, Scherer J, et al. Effects of tipranavir, darunavir, and ritonavir on platelet function, coagulation, and fibrinolysis in healthy volunteers. Curr HIV Res 2011;9:237–46. 10.2174/157016211796320306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Taylor N, Kremser I, Auer S, et al. Hemeoxygenase-1 as a Novel Driver in Ritonavir-Induced Insulin Resistance in HIV-1-Infected Patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75:e13–e20. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lagathu C, Eustace B, Prot M, et al. Some HIV antiretrovirals increase oxidative stress and alter chemokine, cytokine or adiponectin production in human adipocytes and macrophages. Antivir Ther 2007;12:489–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Auclair M, Afonso P, Capel E, et al. Impact of darunavir, atazanavir and lopinavir boosted with ritonavir on cultured human endothelial cells: beneficial effect of pravastatin. Antivir Ther 2014;19:773–82. 10.3851/IMP2752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Reyskens KM, Essop MF. HIV protease inhibitors and onset of cardiovascular diseases: a central role for oxidative stress and dysregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1842:256–68. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gil del Valle L. Pathophysiological implications of altered redox balance in HIV/AIDS infection: diagnosis and counteract interventions. Oxidative Stress: Diagnostics, Prevention, and Therapy 2011:39–70. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zha BS, Wan X, Zhang X, et al. HIV protease inhibitors disrupt lipid metabolism by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress and inhibiting autophagy activity in adipocytes. PLoS One 2013;8:e59514 10.1371/journal.pone.0059514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ji YX, Zhang P, Zhang XJ, et al. The ubiquitin E3 ligase TRAF6 exacerbates pathological cardiac hypertrophy via TAK1-dependent signalling. Nat Commun 2016;7:11267 10.1038/ncomms11267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Fakruddin JM, Laurence J. HIV envelope gp120-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis via receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) secretion and its modulation by certain HIV protease inhibitors through interferon-gamma/RANKL cross-talk. J Biol Chem 2003;278:48251–8. 10.1074/jbc.M304676200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Laurence J, Modarresi R. Modeling metabolic effects of the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir in vitro. Am J Pathol 2007;171:1724–5. 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Yin MT, Modarresi R, Shane E, et al. Effects of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy with ritonavir on induction of osteoclast-like cells in postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis International 2011;22:1459–68. 10.1007/s00198-010-1363-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Abdullah M, Berthiaume JM, Willis MS. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 as a nuclear factor kappa B-modulating therapeutic target in cardiovascular diseases: at the heart of it all. Translational Research 2018;195:48–61. 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tunjungputri RN, Van Der Ven AJ, Schonsberg A, et al. Reduced platelet hyperreactivity and platelet-monocyte aggregation in HIV-infected individuals receiving a raltegravir-based regimen. AIDS 2014;28:2091–6. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Reyskens KM, Fisher TL, Schisler JC, et al. Cardio-metabolic effectsof HIV protease inhibitors (lopinavir/ritonavir). PLoS One 2013;8:e73347 10.1371/journal.pone.0073347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Collado-Diaz V, Sanchez-Lopez A, Orden S, et al. Leukocytes are key to the pro-thrombotic effect of abacavir. Boston, MA: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 2018. Abst 674. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gresele P, Falcinelli E, Sebastiano M, et al. Endothelial and platelet function alterations in HIV-infected patients. Thromb Res 2012;129:301–8. 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gibellini L, De Biasi S, Pinti M, et al. The protease inhibitor atazanavir triggers autophagy and mitophagy in human preadipocytes. AIDS 2012;26:2017–26. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359b8be [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Loboda A, Damulewicz M, Pyza E, et al. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016;73:3221–47. 10.1007/s00018-016-2223-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. McSweeney SR, Warabi E, Siow RCM. Nrf2 as an Endothelial mechanosensitive transcription factor. Hypertension 2016;67:20–9. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Galley JC, Straub AC. Redox control of vascular function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:e178–84. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Anstee QM, Day CP. S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) therapy in liver disease: a review of current evidence and clinical utility. J Hepatol 2012;57:1097–109. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Fernandez D, Alonso C, van Liempd S, et al. S-adenosylmethionine treatment corrects deregulated lipid metabolic pathways and prevents progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in methionine adenosyltransferase 1a knockout mice: AASLD, 2015. Abst. 953. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Yoon S-Y, Hong GH, Kwon H-S, et al. S-adenosylmethionine reduces airway inflammation and fibrosis in a murine model of chronic severe asthma via suppression of oxidative stress. Exp Mol Med 2016;48:e236 10.1038/emm.2016.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. De la Cruz JP, Mérida M, González-Correa JA, et al. Effects of S-adenosyl-L-methionine on blood platelet activation. Gen Pharmacol 1997;29:651–5. 10.1016/S0306-3623(96)00571-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bartolini D, Dallaglio K, Torquato P, et al. Nrf2-p62 autophagy pathway and its response to oxidative stress in hepatocellular carcinoma. Translational Research 2018;193:54–71. 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mills EL, Ryan DG, Prag HA, et al. Itaconate is an anti-inflammatory metabolite that activates Nrf2 via alkylation of KEAP1. Nature 2018;556:113–7. 10.1038/nature25986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Gilbert JM, Fitch KV, Grinspoon SK. HIV-related cardiovascular disease, statins, and the REPRIEVE Trial. Top Antivir Med 2015;23:146–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Krsak M, Kent DM, Terrin N, et al. Myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality in cart-treated HIV patients on statins. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:307–13. 10.1089/apc.2014.0309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]