Abstract

Background

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a complex chronic inflammatory disease strongly associated with the majority of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 alleles. HLA-E molecules are non-classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules that specifically interact with the natural killer receptors NKG2A (inhibitory) and NKG2C (activating), and have been recently proposed to be involved in AS pathogenesis.‘’

Objective

To analyse the expression of HLA-E and the CD94/NKG2 pair of receptors in HLA-B27-positive patients with AS and healthy controls (HC) bearing the AS-associated B*2705 and the non-AS-associated B*2709 alleles.

Methods

The level of surface expression of HLA-E molecules on CD14+ peripheral blood mononuclear cell was evaluated in 21 HLA-B*2705 patients with AS, 12 HLA-B*2705 HC, 12 HLA-B*2709 HC and 6 HLA-B27-negative HC using the monoclonal antibody MEM-E/08 by quantitative cytofluorimetric analysis. The percentage and density of expression of HLA-E ligands NKG2A and NKG2C were also measured on CD3−CD56+ NK cells.

Results

HLA-E expression in CD14+ cells was significantly higher in patients with AS (587.0, IQR 424–830) compared with B*2705 HC (389, IQR 251.3–440.5; p=0.0007), B*2709 HC (294.5, IQR 209.5–422; p=0.0004) and HLA-B27-negative HC (380, IQR 197.3–515.0; p=0.01). A higher number of NK cells expressing NKG2A compared with NKG2C were found in all cohorts analysed, as well as a higher cell surface density.

Conclusion

The higher surface level of HLA-E molecules in patients with AS compared with HC, concurrently with a prevalent expression of NKG2A, suggests that the crosstalk between these two molecules might play a role in AS pathogenesis, accounting for the previously reported association between HLA-E and AS.

Keywords: ankylosing spondylitis, spondyloarthritis, inflammation

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

The interaction between human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-E and the inhibitory (CD94/NKG2A) and activating (CD94/NKG2C) receptors balances the response of natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes.

HLA-E plays a double role in both innate and adaptive immunity.

What does this study add?

We report the upregulation of HLA-E in ankylosing spondylitis immune cells, which may protect autoreactive clones from NK cell lysis and therefore contribute to the chronicity of the inflammatory process.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Modulation of accessory ligand/receptor pairs may affect disease course and contribute to inhibition of inflammation.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease which primarily affects the spine and is characterised by strong genetic association with the human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-B27.1 2 The classical function of HLA class I molecules would suggest the role of microbial, exogenous or self-arthritogenic peptides in the context of a canonical antigen-presenting cell/T cell interaction.3 4 The lack of a definite demonstration of this model has led to the proposition of several alternative hypotheses in order to explain the B27 association with AS, including cell surface B27 heavy chain dimer interactions with receptors (killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR)) on cells of the innate immune system and/or T cells5–7 and the HLA-B27 misfolding and cellular stress response.8–10

In this complex scenario two HLA-B27 alleles, the B*2706 and -B*2709, differing from the ancestral and AS-associated B*2705 allele for five or a single amino acid variation, respectively, have been shown not to be associated with AS,11 12 and several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the different disease association of these B27 alleles.13 14 AS is a complex disorder in which several genes contribute to its development, phenotype and severity, including important immune response genes such as the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 and 2 (ERAP1 and ERA P 2), as well as receptor genes involved in cytokine signalling (interleukin-23 receptor, IL23R).15 More recently, researchers have paid attention to the role of the innate immunity,16 natural killer (NK) cells and several immunoregulatory receptors, as well as ‘nonclassical’ HLA class Ib molecules including HLA-E, as possible players in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated diseases, including AS and psoriatic arthritis.17–19

In this regard, we have previously reported in patients with AS from Sardinia a significant increase of the A allele for single nucleotide polymorphism rs1264457 coding an Arginine (Arg) at the HLA-E functional polymorphism Arg107/Gly107.20 21 The HLA-E/β2m complexes are generally stabilised by peptides derived from the leader sequence of HLA class I molecules22 23 and act as ligands for inhibitory (NKG2A/CD94) and activating (NKG2A/CD94) receptors expressed by NK cells.24 25

The aim of this study is therefore to advance our previous studies analysing the cell surface expression of the HLA-E molecules and the inhibitory/activating CD94/NKG2 pair of receptors comparing patients with AS with healthy controls (HC) and pathological controls.

Methods

Patients and controls

Twenty-one HLA-B*2705 patients with AS fulfilling the modified New York criteria for the diagnosis of AS (15 men and 6 women, mean age 41.4±8.8, mean disease duration 15.7±11.3), 12 HLA-B*2705, 12 HLA-B*2709 and 6 HLA-B27-negative age-matched and sex-matched HCs were recruited. All patients were not on biological drug treatment. No case of spondyloarthropathies was reported in the family medical history of the HC. As further control groups, we also recruited six patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and four HLA-B27-negative patients with AS.

Reagents and monoclonal antibodies

For dual and three-colour staining, the following monoclonal antibodies were used: Phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD56 (NKH-1), Phycoerythrin-Texas Red-conjugated anti-CD3 (UCHT1) and anti-NKG2A unconjugated (Z199), all purchased from Beckman Coulter (Fullerton, California), anti-NKG2C unconjugated (clone 134522; R&D), PE-anti-CD14 (clone HCD14; BioLegend) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat F(ab')2 antimouse (GAM) IgG (F0479; Dako). For the detection of HLA-E surface molecules, three different unconjugated monoclonal antibodies were tested: MEM-E/06, MEM-E/07 and MEM-E/08 (kindly provided by Vaclav Horejsi), recognising surface HLA-E molecules, whose HLA-E specificity was previously defined by flow cytometry on the Third International Conference on HLA-G (Paris, July 2003).26 27 According to the literature, MEM-E/08 resulted as the better one in terms of specificity and was selected for further experiments. The surface expression of HLA-B27 was also analysed (by means of clone ME1) to exclude cross-reactivity of MEM-E/08 with HLA-B27. The expression of the two antigens on cell surface did not overlap. In order to avoid possible unspecific staining, as described in table 1 in Lo Monaco et al,27 27 patients and controls were not HLA-A24-positive, HLA-B7-positive, HLA-B54-positive or HLA-B65-positive.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood was collected by venipuncture into heparinised tubes, and the mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated by density gradient centrifugation (1250 g for 20 min) over Ficoll-Hypaque (Sentinel Diagnostics) at 20°C. The PBMC-rich interface was collected, washed and suspended in tissue culture medium and immediately stained.

Immunofluorescence staining and cytofluorimetric analysis

The cell surface expression of HLA-E molecules on CD14+ and NKG2A or NKG2C ligands on CD3−CD56+ NK cells was measured by indirect immunofluorescence staining.

Briefly, mononuclear cells were suspended at 5×106 cells/mL in PBS-NaN3 with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The entire procedure was performed on ice at 4°C, and 100 µL (5×105 PBMC) was placed in the analysis tube. Fc receptors were blocked by incubating with 10 µL of normal human serum diluted 1:5 with PBS/BSA. PBMCs were then incubated for 30 min with the appropriate amount of a saturating concentration of unconjugated primary monoclonal antibody (mAb). After two washes cells and mouse IgG-coated quantitative calibration beads were incubated for 30 min with saturating concentration (8 µL/100 µL/tube) of FITC-conjugated polyclonal goat antimouse immunoglobulin (FITC-GAM; Dako). Cells were then treated with mouse serum (Zymed), followed by staining with anti-CD14 or a combination of anti-CD3 and anti-CD56. PBMCs were washed twice, fixed in 500 µL of PBS-1% NaN3 with 1% paraformaldehyde and analysed by flow cytometry (Coulter EPICS XL) within 24 hours (at least 100 000 cells were acquired). Controls were always included in the experiments by staining PBMCs with irrelevant mAbs.

Cytofluorimetric analysis was performed using a Coulter EPICS XL (Coulter, USA), except for patients with RA, HLA-B27-negative patients with AS and culture experiments which were performed in a later stage using a BD FACSCanto (Becton Dickinson, USA). For each sample the mean fluorescence channel was expressed as a relative channel number on a linear scale, compared with five differently defined mouse antibodies-coated standards (beads) and converted in antibody binding capacity (ABC) (Dako, Denmark). The primary and secondary antibodies for cells labelling were used at saturating concentration.

Cell culture

PBMCs were obtained from fresh heparinised blood by centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque as previously described, in four patients with AS. Cells were suspended at a final concentration of 1×106 cells/mL and seeded in a multiwell plate with RPMI 1640 (Corning) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomicin and glutamine (Corning). Phytohemagglutinin-M (PHA, Roche) was used as stimuli at 5 mg/mL concentration. Seventy-two hours after seeding, mononuclear cells were collected and analysed using the previously described cytofluorimetric protocol. The surface expression of HLA-E molecules on CD14+ cell was measured using the antibodies MEM-08. The T lymphocyte activation induced by PHA was verified by means of the IL-2 receptor CD25 (eBioscience, data not shown).

Calculation of antigen density

ABC is the number of primary mouse monoclonal antibodies per cell or microbead. Background antibody equivalent (BAE) is the apparent ABC of the negative control for cells or blank beads due to background fluorescence. Specific antibody binding capacity (SABC) is the number of primary mouse monoclonal antibodies per cell after corrections for background (BAE): SABC=ABC–BAE. Given the saturating conditions of the mAbs, SABC corresponds to the mean number of accessible antigenic sites per cell, referred to as antigen density and expressed in sites/cell (according to Dako manufacturer’s instructions).

Statistical analysis

Values were expressed as median percentage of positive cells (IQR) and as median of cell surface antigen density in ABC units (IQR); the values were also expressed as mean±SD. The differences between AS and HC cohorts were analysed by one-way analyses of variance with Bonferroni post-test and the two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism V.5.0 software (GraphPad).

Results

HLA-E

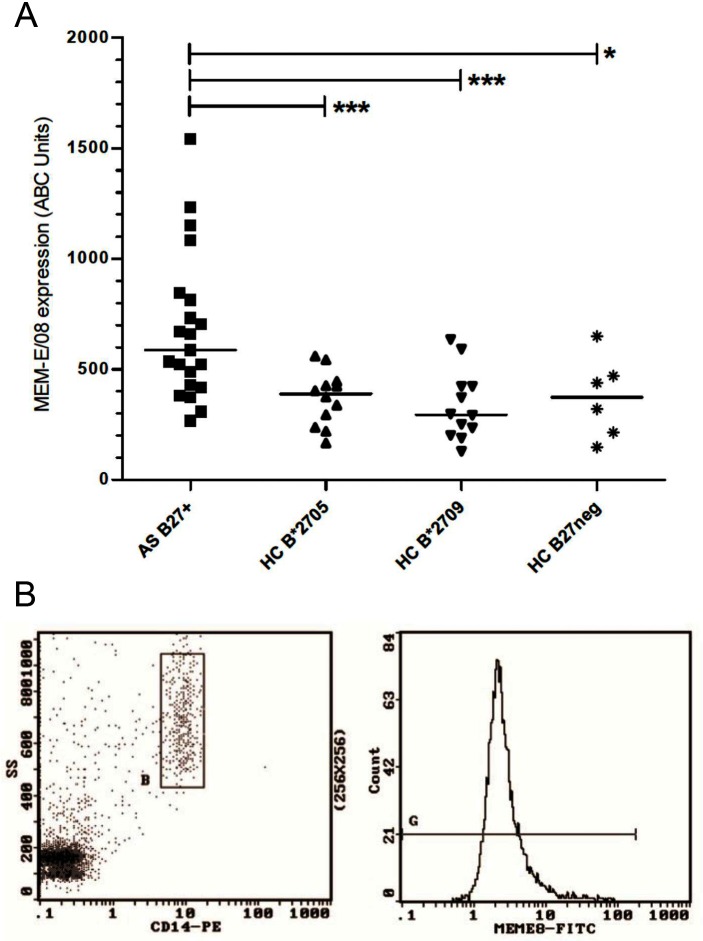

HLA-E expression was evaluated by using MEM-E/08 on myeloid lineage cells (CD14+) from HLA-B*2705-positive patients with AS, HLA-B*2705 and HLA-B*2709-positive HC or HLA-B27-negative HC. We observed a statistically significant higher expression of HLA-E molecules on the cell surface of the AS group compared with the HC: AS, 587.0 (IQR 268–830, mean 679.7±333.6; ABC units); B*2705 HC, 389 (IQR 251.3–440.5, mean 369.4±123.3; p=0.007); B*2709, 294.5 (IQR 209.5–422, mean 336.3±157.9; p=0.0004); and B27-negative HC, 380 (IQR 197.3–515, mean 373.5±184.1; p=0.01) (figure 1). No statistical difference was found between HLA-B*2705, HLA-B*2709 and HLA-B27-negative HC (p=ns). MEM-E/08 expression was analysed also in CD14− cells: AS, 218 (IQR 159.5–310.5, mean 253.2±157.4, ABC units); B*2705, 182 (IQR 141.3–325, mean 245.4±164; p=ns); B*2709, 180 (IQR 100.5–262.8, mean 189.8±101.3; p=ns); and B27-negative HC, 159 (IQR 122.8–235.8, mean 179±76.8; p=ns) (see also online supplementary figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) HLA-E expression on the surface of CD14+ cells in patients with AS, HLA-B*2705, HLA-B*2709-positive and HLA-B27-negative HCs. Results are expressed in specific ABC units. Horizontal lines represent median values. Statistical significance was observed only in the comparison between the AS group and the HC group (p<0.001=***0.001 to 0.01=**0.01 to 0.05=*). No differences were observed among the HC group. (B) Representative cytofluorographic profile of a B27-positive patient with AS showing CD14 gating and MEM-E/08 staining in PBMC. ABC, antibody binding capacity; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; HC, healthy control; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PE, phycoerythrin; SS, side scatter.

rmdopen-2017-000597supp001.tiff (6.4MB, tiff)

HLA-E expression was not correlated with HLA-B27 expression (determined by means of mAb ME1) in patients with AS and HC (r=0.22; p=ns) (online supplementary figure 2).

rmdopen-2017-000597supp002.tiff (5.1MB, tiff)

At a later stage, as further control groups, HLA-E molecule expression was also measured in six patients with RA (as a different chronic inflammatory arthropathy) and four HLA-B27-negative patients and compared with B27-positive AS; no statistical differences were observed comparing the three pathological groups: RA 537 (IQR 270.8–612; 488±266; p=ns), B27-negative AS 435 (IQR 297.3–1201; 644.5±541.2; p=ns).

HLA-E expression was evaluated in CD14+ PBMC from four patients with AS following 72 hours in vitro culture with medium only or with PHA-M as stimuli, as described in the Methods section: 72 hours RPMI 1640-only 913.5±202.5; PHA 1309.5±554.5, showing a 1.5-fold increase following in vitro PHA cell stimulation.

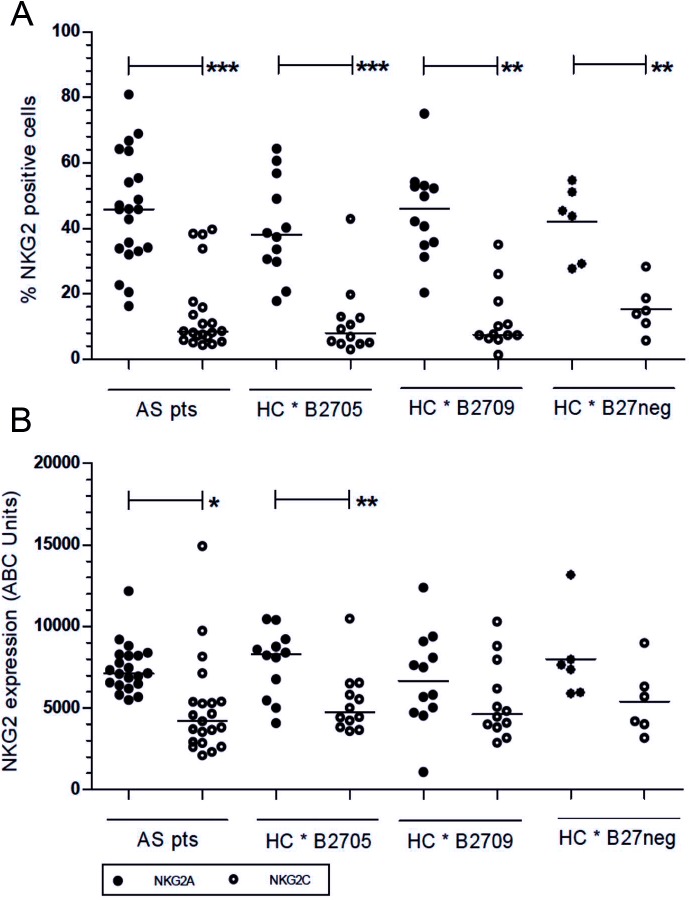

NKG2A

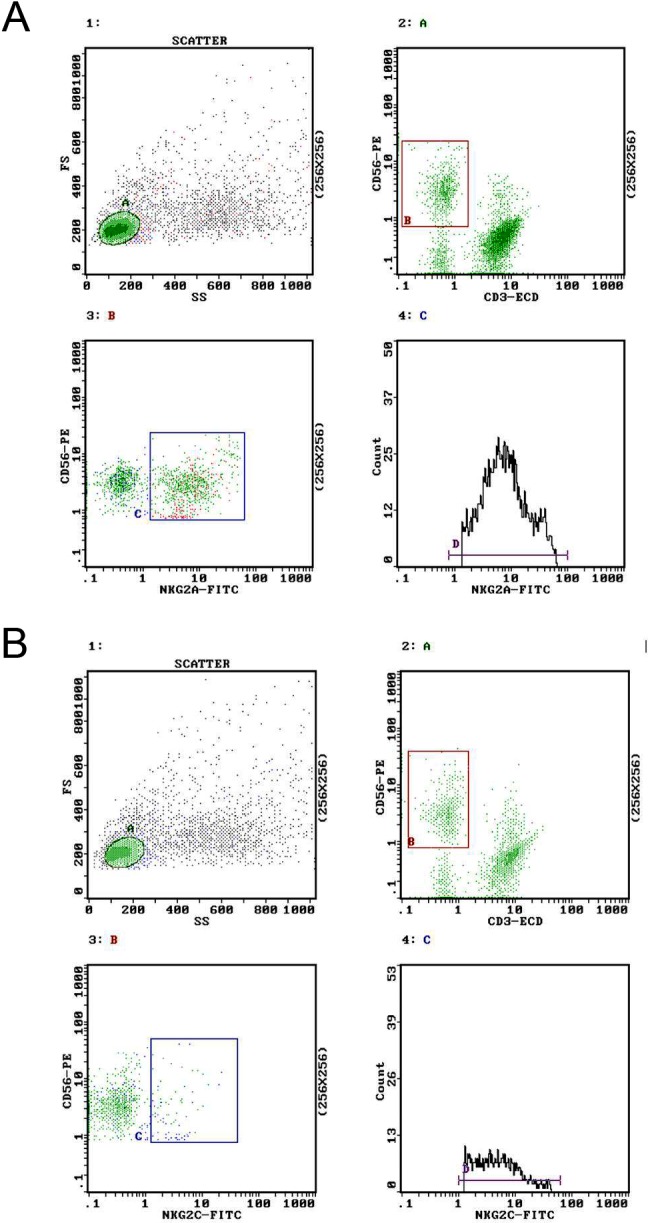

The percentage of NK cells expressing NKG2A in AS was 45.8% (IQR 33.5–59.5, 45.6±17.1), in B*2705 HC was 38.0% (IQR 30.0–54.8, 39.9±15.0 (AS vs B*2705 HC; p=ns)), in B*2709 HC was 45.9% (IQR 35.1–52.9, 45.1±14.1 (AS vs B*2709 HC; p=ns)) and in B27-negative HC was 44.5% (IQR 28.8–52.0, 41.9±11.2 (AS vs B27-negative HC; p=ns)); the surface density of the receptor in patients with AS was 7128 ABC units (IQR 6432–8238, 7443±1497), in B*2705 HC was 8310 ABC units (IQR 6782–9094, 7784±2046 (AS vs B*2705 HC; p=ns)), in B*2709 HC was 6654 ABC units (IQR 8829–4791, 6739±841 (AS vs B*2709 HC; p=ns)) and in B27-negative HC was 7505 ABC units (IQR 5937–9265, 7997±2674 (AS vs B27-negative HC; p=ns)) (figure 2, upper and lower panels). A representative cytofluorographic profile of a B27-positive patient with AS showing NKG2A staining on CD3−/CD56+ gated PBMC is shown in figure 3A.

Figure 2.

(A) NKG2A and (B) NKG2C expression on NK cells in subjects with AS and HCs. The upper figure represents % of NK positive cells; the lower figure represents cell surface density of receptor expression (ABC units). Horizontal lines represent the median values. Statistical differences were observed between NKG2A and NKG2C percentages of positive cells in all different cohorts (upper panel). The inhibitory receptor NKG2A also showed a higher cell surface density compared with the activator receptor NKG2C, reaching statistical significance in patients with AS (p=0.02) and B*2705 HCs (p=0.007) (lower panel). No differences were observed comparing the different cohorts of subjects. p<0.001=***0.001 to 0.01=**0.01 to 0.05=*. ABC, antibody binding capacity; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; HC, healthy control; NK, natural killer.

Figure 3.

Representative cytofluorographic profile of a B27-positive patient with AS showing (A) NKG2A and (B) NKG2C staining on CD3−/CD56+ gated PBMC. The mean intensity of fluorescence was calculated and transformed in ABC units according to calibration beads performed in each experimental session, as described in the Methods section. ECD, PhycoerythrinTexasRed-X; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; FS, forward scatter; NK, natural killer; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PE, phycoerythrin; SS, side scatter.

NKG2C

Significantly lower percentage of positive NK cells for the activating receptor NKG2C was found among AS and healthy subjects comparing with the inhibitory receptor NKG2A in the same group of subjects: AS 8.5% (IQR 6.3–16.7, 14.3±12.1; p<0.0001); B*2705 HC 8.0% (IQR 4.8–12.9, 11.5±10.9; p=0.0001); B*2709 HC 7.5% (IQR 6.6–15.9, 11.9±9.6; p<0001); and B27-negative HC 14.4% (IQR 9.7–21.1, 15.4±7.6; p<0001) (figure 2, upper panel). Similarly, NKG2C also showed a lower cell surface density compared with the inhibitory receptor, reaching statistical significance in patients with AS (p=0.02) and B*2705 HCs (p=0.007) (figure 2, lower panel). Analysis among groups showed similar density of the activator receptor NKG2C on the cell surface in patients with AS (4200, IQR 2898–5387, 4992±2998 ABC units; p=ns), in B*2705 (4724, IQR 3930–6334, 5339±1922; p=ns), B*2709 (4633, IQR 3855–7518, 5459±2364; p=ns) and B27-negative HC (4943 ABC units IQR 3801–6978, 5394±2099; p=ns). A representative cytofluorographic profile of a B27-positive patient with AS showing NKG2C staining on CD3−/CD56+ gated PBMC is shown in figure 3B.

NKG2A and NKG2C percentages of positive cells and surface density were also correlated with HLA-E (r=0.11 and r=−0.02, respectively, for NKG2A; and r=0.02 and r=−019, respectively, for NKG2C) and HLA-B27 (r=0.03 and r=0.11 for NKG2A; and r=−0.14 and r=−0.27 for NKG2C) expression. No statistical significance was observed in all these analyses.

Discussion

HLA-E belongs to the non-classical HLA class Ib family and is characterised by a limited polymorphism and a restricted pattern of cellular expression.18 28 The interaction between HLA-E cell surface molecules and the inhibitory (CD94/NKG2A) and activating (CD94/NKG2C) receptors is considered to play a crucial role in balancing the immunological response involving NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, therefore playing a double role in both innate and adaptive immunity.19

The expression of HLA-E mRNA is detectable in almost all nucleated cells, while the surface molecular expression is more restricted and requires the binding of peptides derived from the leader peptide of HLA class I molecules to be presented to NK cells. Cells with low levels of HLA class I expression generate low levels of HLA class I-derived peptides and consequently display low levels of HLA-E, thus becoming a better target for the NK cells. Conversely, a more abundant level of HLA class I molecules can inhibit NK cell lysis, by more effectively interacting with the inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A.24 This overexpression could therefore play an indirect role by strengthening HLA-E/NKG2A ligation. HLA-E can also bind NKG2C activating receptor, although its affinity is sixfold lower compared with NKG2A.29

In two different genetic studies we have previously demonstrated a link between HLA-E and AS, and the data shown in this study further support the evidence of a role in the complex mechanisms which drive the inflammatory milieu in AS. HLA-E is also involved in viral, cancer and multiple sclerosis immunity,30 and we therefore cannot currently exclude that other mechanisms may also explain its association with AS. It is nevertheless intriguing that HLA-E has been reported to be upregulated in peripheral blood and synovial fluid cells from patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis,31 and in this regard we also found in patients with RA a high level of HLA-E expression, similar to AS. It has been also demonstrated that HLA-E and its homologue in mice are able to inhibit NK cells cytolysis.32 Furthermore, blocking HLA-E/NKG2A interaction by means of monoclonal antibodies in a mouse model of encephalomyelitis resulted in amelioration of the disease because of NK-dependent lysis of autoreactive cells.33 Taken together these data may suggest that upregulation of HLA-E in AS immune cells may protect autoreactive clones from NK cell lysis and therefore contribute to the chronicity of the inflammatory process, while the inflammatory milieu may itself upregulate HLA-E expression, as suggested by our in vitro data showing increased expression of HLA-E molecules following PBMC stimulation with PHA.

The data emerging from this study confirm that innate immunity and NK cells may play a relevant role in the pathogenesis of AS and that HLA-E may provide a contribution to the leading role played by HLA-B27 as well as environmental factors.34 35 A large spectrum of ligands and receptors contribute to orchestrate NK functions that are further fine-tuned by different pairs of ligands and receptors. In the Sardinian population, we have previously shown an association of HLA-E with AS. This association might be present in some populations but not in others. In this regard, it is noteworthy that two studies from Spain and Asia36 37 have described an imbalance of KIR alleles in patients with AS, but these data could not be confirmed in a cohort from UK.38 The possible discrepancy in accessory pathways in different populations may be explained by different genetic background and environmental pressure, which may lead to impaired regulatory functions. For the above-mentioned reasons, genetic isolate as the Sardinian population13 appears to be the ideal cohort to single out predisposing genes in complex diseases, particularly in pathological conditions like AS where a single gene (HLA-B27) accounts for most of the genetic predisposition.

Conclusion

This study shows a higher expression of HLA-E molecules in patients with AS compared with HC and a larger expansion of NK cells expressing the NKG2A inhibitory receptor, which also appears more expressed on the cell surface. Taken together, the data suggest that the crosstalk between the HLA-E molecules and the corresponding inhibitory receptors on the NK cells might play a role in AS pathogenesis, accounting for the previously reported association between HLA-E and AS in Sardinia.

Footnotes

Contributors: AC, RS, MTF and AM were involved in the conception and design of the study. MP, AF, MC, EM, FP and VT were involved in the collection and analysis of data. GD, MMA and SP performed the experiments. AC, RS, MTF and AM drafted the manuscript, and all authors reviewed the manuscript critically and gave final approval for its submission.

Funding: This work was supported by Regione Autonoma della Sardegna (grant CRP-60098 L.R. 7/2007 annualità 2012); by Fondazione Ceschina; and by Sapienza through Progetti di Ateneo to RS and MTF.

Competing interest: None declared.

Patient consent: Next of kin consent obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee of the University of Cagliari

(365/09/CE).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data sets analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Schlosstein L, Terasaki PI, Bluestone R, et al. High association of an HL-A antigen, W27, with ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 1973;288:704–6. 10.1056/NEJM197304052881403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bowness P. HLA-B27. Annu Rev Immunol 2015;33:29–48. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nurzia E, Panimolle F, Cauli A, et al. CD8+ T-cell mediated self-reactivity in HLA-B27 context as a consequence of dual peptide conformation. Clin Immunol 2010;135:476–82. 10.1016/j.clim.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tedeschi V, Vitulano C, et al. The ankylosing spondylitis associated HLAB*2705 presents a B*0702 restricted EBV epitope and sustains the clonal amplification of cytotoxic T cells in patients. Mol Med 2016;22:1–223. 10.2119/molmed.2016.00031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kollnberger S, Bird L, Sun MY, et al. Cell-surface expression and immune receptor recognition of HLA-B27 homodimers. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2972–82. 10.1002/art.10605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bowness P, Ridley A, Shaw J, et al. Th17 cells expressing KIR3DL2+ and responsive to HLA-B27 homodimers are increased in ankylosing spondylitis. J Immunol 2011;186:2672–80. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cauli A, Shaw J, Giles J, et al. The arthritis-associated HLA-B*27:05 allele forms more cell surface B27 dimer and free heavy chain ligands for KIR3DL2 than HLA-B*27:09. Rheumatology 2013;52:1952–62. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Turner MJ, Sowders DP, DeLay ML, et al. HLA-B27 misfolding in transgenic rats is associated with activation of the unfolded protein response. J Immunol 2005;175:2438–48. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colbert RA, Tran TM, Layh-Schmitt G. HLA-B27 misfolding and ankylosing spondylitis. Mol Immunol 2014;57:44–51. 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Navid F, Colbert RA. Causes and consequences of endoplasmic reticulum stress in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017;13:25–40. 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. D'Amato M, Fiorillo MT, Carcassi C, et al. Relevance of residue 116 of HLA-B27 in determining susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis. Eur J Immunol 1995;25:3199–201. 10.1002/eji.1830251133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cauli A, Vacca A, Dessole G, et al. HLA-B*2709 and lack of susceptibility to sacroiliitis: further support from the clinic. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008;26:1111–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mathieu A, Cauli A, Fiorillo MT, et al. HLA-B27 and ankylosing spondylitis geographic distribution as the result of a genetic selection induced by malaria endemic? A review supporting the hypothesis. Autoimmun Rev 2008;7:398–403. 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nurzia E, Narzi D, Cauli A, et al. Interaction pattern of Arg 62 in the A-pocket of differentially disease-associated HLA-B27 subtypes suggests distinct TCR binding modes. PLoS One 2012;7:e32865 10.1371/journal.pone.0032865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burton PR, Clayton DG, Cardon LR, et al. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Australo-Anglo-American Spondylitis Consortium (TASC). Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nature Genetics 2007;39:1329–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Appel H, Maier R, Wu P, et al. Analysis of IL-17(+) cells in facet joints of patients with spondyloarthritis suggests that the innate immune pathway might be of greater relevance than the Th17-mediated adaptive immune response. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R95 10.1186/ar3370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takao S, Ishikawa T, Yamashita K, et al. The rapid induction of HLA-E is essential for the survival of antigen-activated naive CD4 T cells from attack by NK cells. J Immunol 2010;185:6031–40. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morandi F, Pistoia V. Interactions between HLA-G and HLA-E in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Front Immunol 2014;5:394 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sokolik R, Gębura K, Iwaszko M, et al. Significance of association of HLA-C and HLA-E with psoriatic arthritis. Hum Immunol 2014;75:1188–91. 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cascino I, Paladini F, Belfiore F, et al. Identification of previously unrecognized predisposing factors for ankylosing spondylitis from analysis of HLA-B27 extended haplotypes in Sardinia. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2640–51. 10.1002/art.22820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paladini F, Belfiore F, Cocco E, et al. HLA-E gene polymorphism associates with ankylosing spondylitis in Sardinia. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R171 10.1186/ar2860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braud VM, Allan DS, Wilson D, et al. TAP- and tapasin-dependent HLA-E surface expression correlates with the binding of an MHC class I leader peptide. Curr Biol 1998;8:1–10. 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee N, Goodlett DR, Ishitani A, et al. HLA-E surface expression depends on binding of TAP-dependent peptides derived from certain HLA class I signal sequences. J Immunol 1998;160:4951–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Braud VM, Allan DS, O'Callaghan CA, et al. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature 1998;391:795–9. 10.1038/35869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee N, Llano M, Carretero M, et al. HLA-E is a major ligand for the natural killer inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:5199–204. 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palmisano GL, Contardi E, Morabito A, et al. HLA-E surface expression is independent of the availability of HLA class I signal sequence-derived peptides in human tumor cell lines. Hum Immunol 2005;66:1–12. 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lo Monaco E, Sibilio L, Melucci E, et al. HLA-E: strong association with beta2-microglobulin and surface expression in the absence of HLA class I signal sequence-derived peptides. J Immunol 2008;181:5442–50. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Strong RK, Holmes MA, Li P, et al. HLA-E allelic variants. Correlating differential expression, peptide affinities, crystal structures, and thermal stabilities. J Biol Chem 2003;278:5082–90. 10.1074/jbc.M208268200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaiser BK, Pizarro JC, Kerns J, et al. Structural basis for NKG2A/CD94 recognition of HLA-E. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008;105:6696–701. 10.1073/pnas.0802736105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Durrenberger PF, Webb LV, Sim MJW, et al. Increased HLA-E expression in white matter lesions in multiple sclerosis. Immunology 2012;137:317–25. 10.1111/imm.12012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prigione I, Penco F, Martini A, et al. HLA-G and HLA-E in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 2011;50:966–72. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Masilamani M, Nguyen C, Kabat J, et al. CD94/NKG2A inhibits NK cell activation by disrupting the actin network at the immunological synapse. J Immunol 2006;177:3590–6. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lu L, Kim H-J, Werneck MBF, et al. Regulation of CD8+ regulatory T cells: Interruption of the NKG2A-Qa-1 interaction allows robust suppressive activity and resolution of autoimmune disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:19420–5. 10.1073/pnas.0810383105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kollnberger S, Chan A, Sun M-Y, et al. Interaction of HLA-B27 homodimers with KIR3DL1 and KIR3DL2, unlike HLA-B27 heterotrimers, is independent of the sequence of bound peptide. Eur J Immunol 2007;37:1313–22. 10.1002/eji.200635997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ramiro S, Landewé R, van Tubergen A, et al. Lifestyle factors may modify the effect of disease activity on radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a longitudinal analysis. RMD Open 2015;1:e000153 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lopez-Larrea C, Blanco-Gelaz M, Torre-Alonso J, et al. Contribution of KIR3DL1/3DS1 to ankylosing spondylitis in human leukocyte antigen-B27 Caucasian populations. Arthritis Res Ther 2006;8:R101 10.1186/ar1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Díaz-Peña R, Blanco-Gelaz MA, Suárez-Álvarez B, et al. Activating KIR genes are associated with ankylosing spondylitis in Asian populations. Hum Immunol 2008;69:437–42. 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harvey D, Pointon JJ, Sleator C, et al. Analysis of killer immunoglobulin-like receptor genes in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:595–8. 10.1136/ard.2008.095927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2017-000597supp001.tiff (6.4MB, tiff)

rmdopen-2017-000597supp002.tiff (5.1MB, tiff)