Abstract

Background

Air pollution exposure is associated with acute exacerbation, disease progression, and mortality in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The objective of this study was to describe the impact of air pollution exposures on disease severity, as well as changes in lung function, in patients with IPF.

Methods

Using home spirometers and symptom diaries, 25 patients with IPF prospectively recorded FVC weekly for up to 40 weeks. Residential addresses were geocoded to estimate weekly mean air pollution exposures for ground-level ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and particulate matter < 2.5 or 10 μm in aerodynamic diameter (PM2.5 and PM10, respectively). The dependence of weekly clinical measurements on preceding levels of each pollutant was assessed with the use of linear mixed models, yielding beta-coefficients with 95% CIs, using varying lag times.

Results

Lower mean FVC % predicted was consistently associated with increased mean exposures to PM10 in the 2 to 5 weeks preceding clinical measurements (range, –0.46 to –0.39 [95% CI, –0.73 to –0.13]; P < .005). Lower mean FVC % predicted over the study period was inversely related to mean levels of NO2 (–0.45 [95% CI, –0.85 to –0.05]; P = .03), PM2.5 (–0.45 [95% CI, –0.84 to –0.07]; P = .02), and PM10 (–0.57 [95% CI, –0.92 to –0.21]; P = .003), averaged over the study. Weekly changes in FVC and changes over 40 weeks were independent of pollution exposures.

Conclusions

Higher air pollution exposures were associated with lower lung function, but not changes in lung function, in patients with IPF. Further studies are needed to characterize the mechanisms underlying this relationship.

Key Words: epidemiology (pulmonary), interstitial lung disease, mobile health

Abbreviations: IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NO2, nitrogen dioxide; O3, ozone; PM2.5, particulate matter < 2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter; PM10, particulate matter < 10 μm in aerodynamic diameter; UCSD-SOBQ, University of California San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire; VAS, visual analog scale

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive parenchymal lung disease of complex etiology.1 FVC and subjective symptom assessments such as dyspnea scores are commonly used to characterize disease severity or progression in patients with IPF. Although these outcomes are typically measured intermittently at intervals of 3 to 6 months, recent data suggest that more frequent longitudinal assessments may improve the precision of change estimates over time.2 Repeated monitoring is feasible and informative in patients with IPF, using hand-held spirometers to measure FVC and self-administered questionnaires to measure dyspnea.2, 3 Short-term changes in symptoms do not seem to be associated with short-term changes in lung function, and it is unknown what factors affect the short-term variability of FVC in these patients.

Air pollution is a ubiquitous exposure and a well-established risk factor for adverse health outcomes, including all-cause and respiratory mortality.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Short-term increases in air pollution exposures are associated with subsequent increases in exacerbations and hospitalizations in patients with asthma or COPD,9, 10, 11, 12 as well as an increased risk of bronchiolitis obliterans in patients following a lung transplant.13 Air pollution exposure has been proposed as a risk factor for the development of interstitial lung disease, with plausible biologic mechanisms.14 Ozone (O3) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) are associated with an increased risk of acute exacerbation of IPF, whereas mortality risk increases with greater exposures to particulate matter < 2.5 or 10 μm in aerodynamic diameter (PM2.5 and PM10, respectively).15, 16 Recent data further suggest that higher exposures to PM10 are associated with more rapid decline in lung function in patients with IPF.17 The effect of air pollution exposures on disease severity and on short-term changes in lung function and dyspnea in patients with IPF is unknown.

The objective of the present study was to define the relationship between air pollution exposure, lung function, and dyspnea in patients with IPF by using weekly home spirometry and self-administered questionnaires. We further examined the relationship between air pollution exposure and changes in lung function and dyspnea over time. Some of these results have previously been presented in abstract form.18

Patients and Methods

Study Population

Patients were prospectively recruited from the longitudinal interstitial lung disease program at the University of California San Francisco between January and September 2014. Eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of IPF (according to current consensus guidelines),1 residence in the state of California, and no concomitant participation in a blinded drug treatment trial of IPF therapy. Each patient’s most recent high-resolution CT scan of the chest was reviewed by an investigator (K. A. J.) to ensure that the extent of emphysema was < 10%, although the scans were not formally scored by a chest radiologist. The local institutional review board approved this study, and all patients provided written informed consent (University of California San Francisco Human Research Protection Program Committee on Human Research; institutional review board no. 13-11433).

Measurements

Patients were enrolled in a longitudinal prospective cohort for up to 40 weeks. At the baseline visit, each patient’s age, sex, smoking history, and complete residential address were recorded. An office-based spirometry meeting American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society standards19 was performed at baseline, measuring absolute values and the percent predicted of FVC.

Home Monitoring

Each patient was provided a personalized hand-held spirometer that met American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society performance standards (Spiro PD version 1.0; PMD Healthcare) and received one-on-one instruction in its use. Hand-held spirometry was performed weekly for up to 40 weeks. The spirometer provided real-time feedback to the patient to support proper spirometric technique and to optimize compliance. Three maneuvers were performed at each weekly assessment, with the highest values recorded for FEV1 and FVC. The device was not blinded, and patients were able to see their recorded values.

Prior to spirometry, patients also completed two weekly questionnaires to measure dyspnea severity, for up to 40 weeks: the University of California San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (UCSD-SOBQ)20 and a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) (e-Fig 1). Permission was obtained for use of the UCSD-SOBQ in this study. Patients recorded a weekly diary documenting the estimated duration of time spent away from home over the previous week. Weekly measurements were omitted if the patient indicated that he or she was away from home for > 72 h that week. Upon study completion, patients returned their diaries and symptom scores and had their home spirometry data uploaded from the device.

Air Pollution Exposures

Air quality data were obtained from the California Air Resources Board for individual patients based on their geocoded residential address. The Air Resources Board is a branch of the California Environmental Protection Agency, providing quality-controlled air quality data from across the state. Data were collected for O3, NO2, PM2.5, and PM10. Pollutant concentrations were calculated at the following levels, in order of decreasing preference: A = from nearest air monitoring site; B = from the county average; C = from the air basin average; or D = no near site, county, or air basin average, depending on data availability. Mean levels of each pollutant were determined for the week prior to any recorded lung function or dyspnea measure. All exposure levels were adjusted for temperature and humidity. Weekly levels for each pollutant were compared vs the US Environmental Protection Agency’s national ambient air quality standards.21

Statistical Analysis

Means, proportions, and SDs were used where appropriate to describe the study population. Mean week-to-week changes in FVC, FEV1, UCSD-SOBQ, and VAS were calculated for the cohort across the study period. In addition, changes in FVC, FEV1, UCSD-SOBQ, and VAS scores were calculated from the beginning to the end of the study for each participant in the cohort.

Cumulative mean exposure levels for each patient were calculated based on the weekly measures for each pollutant over the study period. In addition, mean week-to-week change in each pollutant was calculated for the cohort over the study period. The dependence of weekly measurements of FVC, FEV1, UCSD-SOBQ, and VAS on preceding levels of each pollutant was assessed by using linear mixed models. Mean pollutant exposures and outcome measures were assessed over periods of 2 to 5 weeks’ duration, separated by intervals of 0, 3, and 6 weeks. These assessment periods and lag times were selected for consistency with previous studies on acute exacerbation and to reduce the measurement variability from a single cross-sectional measure of outcome. The association of mean exposure levels with mean lung function and dyspnea over 3 and 40 weeks was similarly examined by using linear regression to represent short-term and longer term associations, respectively. Similarly, the association between each pollutant’s maximum level and average lung function, and changes in lung function, over the study period was assessed. Sensitivity analyses were conducted censoring patients at the time of first self-reported respiratory deterioration/acute exacerbation of IPF and at the time of pirfenidone initiation if the drug was started post-enrollment.

Results

Study Population

Baseline characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1. Thirty patients were screened, and 25 were enrolled in the study. The mean ± SD age was 73.6 ± 7.5 years, 84% were male, and 8 of 25 (32%) were never smokers. Mean duration of follow-up was 33 ± 9 weeks, and 899 weeks of data were included in the analyses. Baseline office-based and hand-held FVC were highly correlated (r = 0.91). The mean baseline values for FVC, UCSD-SOBQ, and VAS were 2.73 ± 0.7 L (68.2 ± 15.2% predicted), 36.3 ± 29.5, and 2.8 ± 2.2, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline Cohort Characteristics (N = 25)

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 73.6 ± 7.5 |

| Sex (male) | 21 (84) |

| Never smokers | 8 (32) |

| Former smokers | 17 (68) |

| Surgical lung biopsy | 10 (40) |

| Years since diagnosis, median (range) | 2.0 (0.25-8.1) |

| FVC absolute, L | 2.73 ± 0.7 |

| FVC % predicted | 68.2 ± 15.2 |

| FEV1 absolute, L | 2.21 ± 0.55 |

| FEV1 % predicted | 75.8 ± 16.4 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.81 ± 0.06 |

| UCSD-SOBQ | 36.3 ± 29.5 |

| 10-Point dyspnea VAS | 2.8 ± 2.2 |

| Proton pump inhibitor use | 11 (44) |

| Gastroesophageal refluxa | 11 (44) |

| History of ischemic heart diseasea | 7 (28) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or No. (%), unless otherwise indicated. UCSD-SOBQ = University of California San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire; VAS = visual analog score.

Self-reported medical history.

The average changes in FVC, UCSD-SOBQ, and VAS over the study period were –0.41 ± 0.31 L, 12.9 ± 31.5, and 0.47 ± 2.4, respectively. The median number of weeks a patient spent > 72 h away from home (and thus those measures were omitted) was 2.3 (range: 0-12 weeks).

Air Pollution Exposure Levels

Given the rolling enrollment, 899 weeks of air pollution measures were obtained for each pollutant. The majority of measures were obtained from the nearest monitoring site ranging from 60% for PM10 to 90% for PM2.5 (e-Table 1). Mean exposure and weekly changes in pollutant levels throughout the study period are presented in Table 2. No measures of NO2, O3, or PM10 exceeded current standards of the US Environmental Protection Agency, although 175 measures of PM2.5 exceeded currently recommended air quality standards.

Table 2.

Air Pollution Exposure Levels Over the Study Period

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD Weekly Change |

|---|---|---|

| PM2.5, μg/m3 | 9.01 ± 6.2 | –0.047 ± 5.4 |

| PM10, μg/m3 | 17.8 ± 11.6 | 0.0035 ± 10 |

| O3, ppb | 24.2 ± 9.1 | 3.0 × 10–6 (±0.005) |

| NO2, ppb | 8.02 ± 5.1 | 0.042 ± 2.9 |

NO2 = nitrogen dioxide; O3 = ozone; PM2.5 = particulate matter < 2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter; PM10 = particulate matter < 10 μm in aerodynamic diameter.

Air Pollution and Lung Function Levels

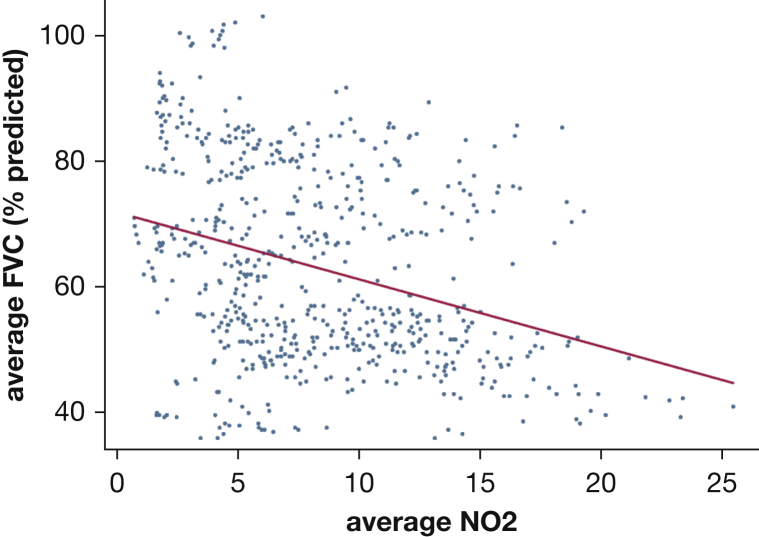

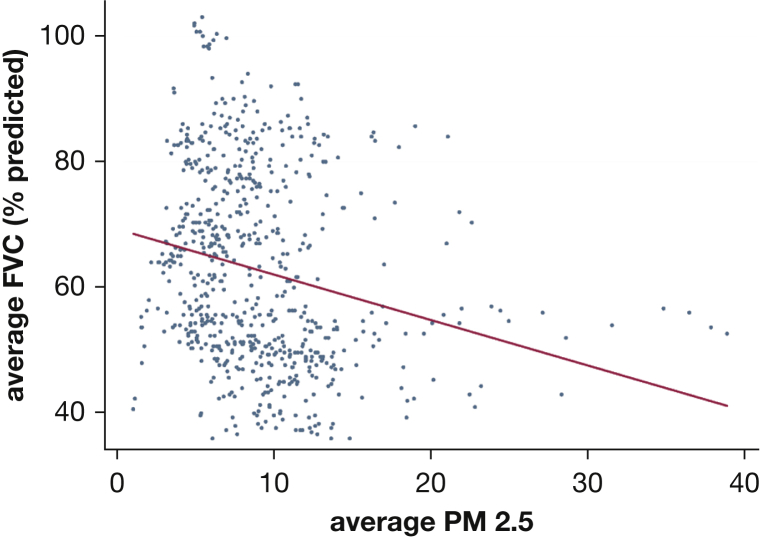

Increased mean exposures to PM10 were consistently associated with lower FVC and FEV1 % predicted, with both assessed over 2 to 5 weeks, and the exposure and outcome assessment periods separated by intervals of 0, 3, and 6 weeks (Tables 3, 4). Lower mean FVC % predicted over the study period was related to mean levels of NO2 (–0.45 [95% CI, –0.85 to –0.05]; P = .03), PM2.5 (–0.45 [95% CI, –0.84 to –0.07]; P = .02), and PM10 (–0.57 [95% CI, –0.92 to –0.21]; P = .003), averaged over the study period (Figs 1, 2). The mean FVC % predicted, averaged over the study period, was highly correlated to the 40-week maximum level of NO2 (–0.42 [95% CI, –0.83 to –0.02]; P = .04), O3 (–0.41 [95% CI, –0.81 to –0.02]; P = .04), PM10 (–0.58 [95% CI, –0.93 to –0.22]; P < .01), and PM2.5 (–0.52 [95% CI, –0.89 to –0.15]; P < .01). No other significant relationships were found between the other pollutants and FVC or for measures of dyspnea, regardless of the duration of the assessment periods or the interval between them (e-Table 2).

Table 3.

Mean PM10 Levels and FVC % Predicted

| Assessment Duration (wk) | Interval Between Exposure and Outcome Assessment Periods (wk) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

3 |

6 |

||||

| β (95% CI) | P Value | β (95% CI) | P Value | β (95% CI) | P Value | |

| 2 | –0.4 (–0.63 to –0.17) | < .005 | –0.39 (–0.64 to –0.14) | < .005 | –0.4 (–0.67 to –0.13) | < .005 |

| 3 | –0.43 (–0.7 to –0.16) | < .005 | –0.42 (–0.69 to –0.15) | < .005 | –0.43 (–0.7 to –0.15) | < .005 |

| 4 | –0.44 (–0.71 to –0.16) | < .005 | –0.44 (–0.73 to –0.16) | < .005 | –0.44 (–0.72 to –0.15) | < .005 |

| 5 | –0.43 (–0.71 to –0.16) | < .005 | –0.45 (–0.73 to –0.17) | < .005 | –0.46 (–0.76 to –0.16) | < .005 |

β = difference in FVC % predicted per unit increase in PM10 levels. See Table 2 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Table 4.

Mean PM10 Levels and FEV1 % Predicted

| Assessment Duration (wk) | Interval Between Exposure and Outcome Assessment Periods (wk) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

3 |

6 |

||||

| β (95% CI) | P Value | β (95% CI) | P Value | β (95% CI) | P Value | |

| 2 | –0.38 (–0.58 to –0.18) | < .005 | –0.37 (–0.6 to –0.14) | < .005 | –0.39 (–0.64 to –0.13) | < .005 |

| 3 | –0.41 (–0.64 to –0.17) | < .005 | –0.39 (–0.64 to –0.15) | < .005 | –0.4 (–0.66 to –0.14) | < .005 |

| 4 | –0.41 (–0.65 to –0.17) | < .005 | –0.41 (–0.67 to –0.16) | < .005 | –0.41 (–0.68 to –0.14) | < .005 |

| 5 | –0.4 (–0.64 to –0.16) | < .005 | –0.41 (–0.67 to –0.16) | < .005 | –0.42 (–0.7 to –0.14) | < .005 |

β = difference in FEV1 % predicted per unit increase in PM10 levels. See Table 2 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Figure 1.

Mean FVC % and mean NO2 over 40 weeks. Increased mean exposure to NO2 was associated with a lower mean FVC % predicted, over 40 weeks. NO2 = nitrogen dioxide.

Figure 2.

Mean FVC % and mean PM2.5 over 40 weeks. Increased mean exposure to PM2.5 was associated with a lower mean FVC % predicted, over 40 weeks. PM2.5 = particulate matter < 2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter.

Air Pollution and Changes in Lung Function

There were no significant relationships between mean week-to-week change in air pollutant levels and concurrent weekly changes in FVC, FEV1, UCSD-SOBQ, or VAS (e-Table 3). We also found no statistically significant associations between mean air pollutant levels and subsequent changes in lung function, regardless of the duration of the assessment periods or the interval between them. Neither higher cumulative mean exposures nor maximal exposures to air pollution were associated with more rapid decline in FVC or FEV1 over the study period. Similarly, there were no significant relationships between cumulative mean exposures and changes in measures of dyspnea over the study period.

In sensitivity analyses, censoring patients at the time of pirfenidone initiation or at the time of self-reported acute exacerbation of IPF/respiratory deterioration did not significantly affect the study results.

Discussion

Higher average exposures to NO2, PM2.5, and PM10 were associated with lower FVC in these study patients with IPF, suggesting that air pollution may affect disease severity in some individuals. In contrast, changes in dyspnea and dyspnea severity were independent of air pollution exposures, in both the short-term and longer term. We did not find that higher pollution exposures were associated with more rapid lung function decline or that short-term increases in exposure resulted in short-term worsening of lung function or dyspnea in this cohort studied for up to 40 weeks. These data are unique in that we were able to closely monitor the lung function and symptoms of patients with IPF, with frequent repeated measures taken over time. These results are reassuring that the air pollution exposure levels in the study did not significantly affect dyspnea over a relatively short period of time.

To our knowledge, this study is the first prospective trial to apply mobile technology for contemporaneous assessment of lung function and dyspnea in relation to environmental exposures in patients with IPF. There is a growing body of literature supporting the use of mobile technology and patient-collected data for both clinical and research purposes. Our data affirm the feasibility of home monitoring and illustrate its potential for novel applications, such as symptom assessment and linking with other data sources. Data linkage between mobile technologies and administrative databases could establish novel frameworks within which to conduct research in the field of IPF.

The cross-sectional relationship of lower FVC with higher average NO2, PM2.5, and PM10 exposures is a novel finding. Long-term inhalational injury may contribute to the risk of developing IPF in certain susceptible individuals. This suggests that at any point in the disease process, an individual’s disease may be more severe due to environmental influences. Our findings do not conclusively address this question, as the cohort comprised prevalent, not incident, cases of IPF, and we could not account for time since diagnosis. It is unknown what variables may influence FVC % predicted at any given cross-sectional assessment; however, environmental exposures such as air pollution warrant reasonable consideration. Air pollution exposures may also be a surrogate for other impactful variables, such as access to health care or socioeconomic status, both well-established predictors of poor health outcomes.22, 23, 24 Longer term studies of larger cohorts will be needed to comprehensively address these questions.

Recent data suggest that increased PM2.5 and PM10 exposures are risk factors for mortality in patients with IPF16 and that higher PM10 exposure is associated with accelerated lung function decline in patients with IPF.17 Our study was underpowered to assess mortality. We did not find that air pollution levels were associated with rate of loss of FVC over 40 weeks, which is likely due to the short duration and small sample size of our study compared with a previous study.17 Also, five patients were taking pirfenidone at baseline enrollment, with another nine starting the drug during the study period, which may have reduced our ability to detect the impact of air pollution on lung function decline.25 However, our finding that disease severity, defined by using FVC % predicted, is associated with higher PM10 exposures is consistent with the findings of Winterbottom et al,17 and this adds to the body of literature supporting a potential pathogenic role in fibrotic interstitial lung disease.

Week-to-week changes in FVC were independent of air pollution exposure in the study cohort. This outcome has a number of possible explanations. The trial may have been underpowered to detect a relationship between exposure and outcome in this relatively small study; however, we think this possibility is unlikely given the amount of repeated measures data collected over the study period using home monitoring. It is more likely that FVC may be too coarse of a measure to detect the subtle cellular effects of air pollution exposure, and alternate measures such as BAL fluid analysis or serum biomarker assessment may have provided more granular data, although they were not part of the study protocol. Although there was spatial variability in this cohort, the diversity in the air pollution exposure levels may have been inadequate to detect small effects, particular when examining changes from 1 week to the next. California has relatively good air quality, and stronger effects may have been seen with higher pollution exposures, as exist in other regions. Short-term variability in FVC may simply be influenced by other unmeasured factors such as fluctuating comorbid conditions (eg, gastroesophageal reflux, cardiac disease, infection), fatigue, or patient effort, which would limit our ability to detect a change due to pollution over a short time. Finally, it may require > 40 weeks of follow-up to show the impact of air pollution exposure on FVC.

Our study has a number of important limitations, namely the small sample size and relatively short duration of follow-up. The study was not designed to assess the impact of air pollution on acute exacerbation or mortality in patients with IPF. Lastly, we cannot exclude misclassification bias with respect to air pollution estimates, given that we did not record patient-level time-activity data. Future studies using personalized exposure monitors or, better yet, validated biomarkers of exposure will be required to overcome this potential bias.

Conclusions

Increased exposures to PM10, PM2.5, and NO2 were associated with lower lung function in this cohort of patients with IPF followed up prospectively for up to 40 weeks. However, changes in lung function from 1 week to the next, as well as over 40 weeks of follow-up, were independent of air pollution exposures, suggesting that lung function variability may be driven by other factors. Patient-reported dyspnea scores were also independent of air pollution exposures over the short term and longer term. Future studies in this area should consider combining mobile health technologies with individualized exposure assessment tools to best address these questions.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: K. A. J. takes full responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including data and analysis. K. A. J., E. V., J. R. B., and H. R. C. conceived of the idea; and J. M., E. M. N., and P. J. W. contributed data and critical intellectual input to the study. All authors contributed to, and approved, the final version of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: K. A. J. reports personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Hoffman-La Roche and grants from the CHEST Foundation/Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation and UCB Pharma. J. M. reports personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Hoffman-La Roche. P. J. W. has served on an advisory board for Genentech/Roche and received grants from MedImmune and Genentech. H. R. C. reports personal fees from MedImmune, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Xfibra, Genoa, Gilead, Moerae Matrix, PharmAkea, Prometic, Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, aTyr pharmaceuticals, GBT, Veracyte, Patara, Alkermes, Takeda, Pharma Capital Partners, and Bristol-Myers Squibb outside the submitted work. None declared (E. V., E. M. N., J. R. B.).

Role of the sponsor: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Figure and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was funded by the CHEST Foundation/Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Clinical Research Grant in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Dr Collard is supported through a National Institutes of Health grant (Grant No. HL127131).

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Raghu G., Collard H.R., Egan J.J. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johannson K.A., Vittinghoff E., Morisset J., Lee J.S., Balmes J.R., Collard H.R. Home monitoring improves endpoint efficiency in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(1) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02406-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell A.M., Adamali H., Molyneaux P.L. Daily home spirometry: an effective tool for detecting progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(8):989–997. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201511-2152OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Q., Wang Y., Zanobetti A. Air pollution and mortality in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(26):2513–2522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jerrett M., Burnett R.T., Pope C.A., III Long-term ozone exposure and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1085–1095. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jerrett M., Burnett R.T., Beckerman B.S. Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in California. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(5):593–599. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0609OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell M.L., Ebisu K., Peng R.D., Samet J.M., Dominici F. Hospital admissions and chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(12):1115–1120. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1240OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pope C.A., III, Ezzati M., Dockery D.W. Fine-particulate air pollution and life expectancy in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):376–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0805646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng Y.Y., Rull R.P., Wilhelm M., Lombardi C., Balmes J., Ritz B. Outdoor air pollution and uncontrolled asthma in the San Joaquin Valley, California. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(2):142–147. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.083576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann J.K., Balmes J.R., Bruckner T.A. Short-term effects of air pollution on wheeze in asthmatic children in Fresno, California. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(10):1497–1502. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen Z.J., Bonnelykke K., Hvidberg M. Long-term exposure to air pollution and asthma hospitalisations in older adults: a cohort study. Thorax. 2012;67(1):6–11. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dominici F., Peng R.D., Bell M.L. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nawrot T.S., Vos R., Jacobs L. The impact of traffic air pollution on bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and mortality after lung transplantation. Thorax. 2011;66(9):748–754. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.155192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johannson K.A., Balmes J.R., Collard H.R. Air pollution exposure: a novel environmental risk factor for interstitial lung disease? Chest. 2015;147(4):1161–1167. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johannson K.A., Vittinghoff E., Lee K. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis associated with air pollution exposure. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(4):1124–1131. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00122213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sesé L., Nunes H., Cottin V. Role of atmospheric pollution on the natural history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2018;73(2):145–150. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-209967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winterbottom C.J., Shah R.J., Patterson K.C. Exposure to ambient particulate matter is associated with accelerated functional decline in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2018;153(5):1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johannson K.A., Vittinghoff E., Morisset J. Air Pollution Exposure, Lung Function and Dyspnea in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A1126. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller M.R., Hankinson J., Brusasco V. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eakin E.G., Resnikoff P.M., Prewitt L.M., Ries A.L., Kaplan R.M. Validation of a new dyspnea measure: the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. University of California, San Diego. Chest. 1998;113(3):619–624. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Environmental Protection Agency National Ambient Air Quality Standards. http://www.epa.gov/air/criteria.html. Accessed May 1, 2017.

- 22.Sommer I., Griebler U., Mahlknecht P. Socioeconomic inequalities in non-communicable diseases and their risk factors: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:914. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandi A., Glymour M.M., Subramanian S.V. Association among socioeconomic status, health behaviors, and all-cause mortality in the United States. Epidemiology. 2014;25(2):170–177. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Signorello L.B., Cohen S.S., Williams D.R., Munro H.M., Hargreaves M.K., Blot W.J. Socioeconomic status, race, and mortality: a prospective cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):e98–e107. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King T.E., Jr., Bradford W.Z., Castro-Bernardini S. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.