Abstract

The majority of investigations into anesthetic effects on the nervous system have used electrophysiology. Yet fundamental limitations of electrophysiologic recordings, including the invasiveness of the technique, the need to place (potentially several) electrodes in every site of interest, and the difficulty of selectively recording from individual cell types, have driven the development of alternative methods for detecting neuronal activation. Two such methods with cellular scale resolution have matured in the last few decades and will be reviewed here: the transcription of immediate early genes, foremost c-fos, and the influx of calcium into neurons as reported by genetically encoded calcium indicators, foremost GCaMP6. Reporters of c-fos allow detection of transcriptional activation even in deep nuclei, without requiring the accurate targeting of multiple electrodes at long distances. The temporal resolution of c-fos is limited due to its dependence upon the detection of transcriptional activation through immunohystochemical assays, though the development of RT-PCR probes has shifted the temporal resolution of the assay when tissues of interest can be isolated. GCaMP6 has several isoforms that trade off temporal resolution for signal-to-noise, but the fastest are capable of resolving individual action potentials, provided the microscope used scans quickly enough. GCaMP6 expression can be selectively targeted to neuronal populations of interest, and potentially thousands of neurons can be captured within a single frame, allowing the neuron-by-neuron reporting of circuit dynamics on a scale that is difficult to capture with electrophysiology, as long as the populations are optically accessible.

Introduction

Experimental techniques must be carefully selected to balance their strengths and weaknesses in order to address the questions of interest. As our understanding of the effects of anesthetics on isolated neurons has matured, the field has begun to ask how those changes that occur in isolated neurons combine together in the brain to produce the features of general anesthesia, be they unarousable unresponsiveness, amnesia, or analgesia. The modulation of the dynamics of neuronal assemblies may be the sine qua non of anesthetic drugs (Collins et al., 2007). As but one example, consciousness appears to involve distributed processes in multiple neuronal circuits. Thus, studies of how anesthetics disrupt consciousness must necessarily assess the effects of anesthetics at a circuit or network level. Hence, probing the effects of anesthetics on circuit function depends upon our having methods for sampling multiple neurons in the circuit simultaneously, with certainty about the recorded neurons identity.

The fundamental unit of information transmission in the brain is the action potential, a stereotyped electrical event. It should come as no surprise that the dominant method for studying the function of the nervous system has been electrical recording of neuronal activity. And yet, depending upon the spatial layout of the neuronal circuit of interest, some investigations at a network level are difficult at best with standard electrophysiologic tools. To address these shortcomings, neuroscientists have developed multiple alternative methods for assaying neuronal activation, with their own associated advantages and limitations. Two of the most well developed assays of neuronal activation utilize either the transcription of the so-called immediate-early genes (IEGs, most frequently c-fos) as a reporter of transcriptional activation or on the change in fluorescence of genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs, of which the dominant reporter at the time of this writing is GCaMP6).

The near-universal ability of volatile anesthetics to place organisms across multiple kingdoms into a behaviorally quiescent state offers a wide range of models for the effects of anesthetics, beginning with Claud Bernard’s vitalist notions that life itself can be defined as susceptibility to anesthetics (Perouansky, 2012). More molecularly selective agents, such as propofol, etomidate, and ketamine, require more specific nervous system design principles; an organism that does not express a γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor (GABA-A) should not be expected to be anesthetized by a GABA-ergic hypnotic agent. While single-cell organisms may offer limited insights about how anesthetics disrupt human consciousness, different model organisms with variably complicated nervous systems can be exploited to explore the effects of anesthetic drugs. Intuitively, however, the more complicated the model system, the more useful complementary assays of neuronal activity may prove.

The focus of this manuscript is the motivation for and application of these non-electrophysiologic methods to studies of anesthetic mechanisms at the circuit level, and interested readers should explore one of several excellent reviews of both IEG reporters and GECIs that exist. While other alternative assays of neuronal activation also exist (for example, functional imaging with fMRI), both IEGs and GECIs offer the ability to detect activation with single neuron resolution, motivating their grouping as distinct from population-level assays. Before delving into the methods by which these techniques can be used, it is worth exploring when and why these methods should be considered in the first place, whether they are used to replace or augment more established electrophysiologic techniques. I will begin with two of the major difficulties faced by electrophysiology that would suggest incorporating either IEGs or GECIs to assist with a study of circuit mechanisms of anesthesia, not to fault electrophysiology techniques, but to point out the relative strengths of alternative assays.

Measures of Neuronal Activation

Concurrent with the development of these alternative technologies has been a broadening of the notion of neuronal activation (Figure 1A). Historically, investigators have focused on the action potential as the primary unit of neuronal activity, which had the advantage of being particularly well suited to the rapidly maturing technology that allowed electrophysiologic investigation. A glass microelectrode offers a clear view of the voltage within a single neuron. But intracellular recordings are difficult to obtain in vivo and difficult to maintain for long periods of time. Extracellular electrical recordings are able to identify the stereotypic form of an action potential with good signal to noise by high-pass filtering the recorded electrical signal above approximately 300Hz. In vivo, and even ex vivo in slice preparations, extracellular recordings are actually detecting a spatial summation of the activity of all nearby neurons. By positioning an extracellular electrode within approximately 50μm of an individual neuron (Buzsáki, 2004), it is possible to obtain a reasonably isolated assessment of the response of a single neuron in vivo in real time. To sample more members of a circuit, multiple electrodes can be recorded simultaneously, and the shape of the recorded action potential at each different electrode can be used to putatively assign that action potential to a distinct neuron generator (Abeles and Goldstein, 1977), though each added electrode risks traumatizing the neurons of interest. The most frequent electrode configuration employed for extracellular recording is a tetrode, to allow sorting of action potentials into different putative units on the basis of spike morphology at each of the different electrodes (Harris et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2003), without causing a great deal of damage to the neurons of interest. Yet spike variability over time, especially with different behavioral conditions, can seriously compromise the ability of spike sorting to properly attribute spike activity when compared with intracellular recordings (Stratton et al., 2012).

Figure 1.

A. Different measures of neuronal activation include intracellular and extracellular electrical recordings, intracellular calcium concentration measured through fluorescent reporters or through downstream transcriptional activation of IEGs like c-fos through CAM kinase (CAMK) and MAP Kinase (MAPK) pathways, and measures of metabolism such as uptake of oxygen in the BOLD response. B. Selected brain regions of interest in anesthesiology and pain research. Deep targets indicated by gray shading. The wide spatial distribution through the central nervous system, makes IEG reporter approaches appealing for simultaneous sampling. Similarly, deep targets are difficult to access with electrophysiology and microscopy methods. Abbreviations: PFC, prefrontal cortex; Thal, thalamus; NB, nucleus basalis of Meynert; VLPO, ventral lateral preoptic nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area; PAG, periaqueductal gray; LDT, lateral dorsal tegmentum; LC, locus ceruleus; PBN, parabrachial nucleus; SC, spinal cord. C. Layer 2/3 of frontal cortex in a mouse expressing the red fluorescent protein Td-tomato in parvalbumin expressing interneurons and the green fluorescent protein GCAMP6 in pyramidal neurons. Electrophysiologic methods cannot easily target specific cell types during recording, whereas genetically encoded calcium indicators can target expression to specific cell lines.

To combat this attribution problem while asking questions about population responses, more investigators have begun to consider the content of the low frequency below 300 Hz, the so-called local field potential (LFP), as a worthy topic of study in itself, reflecting the local average of the dendritic potentials and hence providing a measure of the computational input to a recorded neuronal population. The energetic demands of maintaining the resting potential in the face of constant dendritic depolarizations explains the high correlation between the LFP and the functional imaging measures of blood flow and blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) response detected with magnetic resonance imaging (Logothetis, 2003). The LFP thus forms a bridge between individual neuronal activity and population level assessment of circuit activity.

The development of calcium indicators as reporters of neuronal activity hinges upon the influx of calcium into the neuron that occurs, either via the NMDA receptor or the L-type voltage sensitive calcium channel (Chaudhuri et al., 2000). As a result, calcium influx can occur during both action potential propagation and also dendritic depolarization that does not necessarily lead to an action potential firing. Hence, measures of intracellular calcium in the dendritic tree approximate the synaptic inputs to an area, while in the cell body it represents the integrated inputs to the cell before final application of the spike thresholding nonlinearity that converts a continuous input into the point-process event of the action potential. Finally, if there is sufficient or prolonged enough calcium influx to activate the MAP Kinase pathway, neurons will change their protein expression profile, undergoing transcriptional activation in response to particular input patterns, beginning with transcription of the IEGs, in yet another sense of neuronal “activation” (Chung, 2015).

Difficulties with Electrophysiology

Accessibility and scale

Investigation of anesthetic mechanisms at a systems level requires the simultaneous sampling of multiple, identified circuit members. Neuronal circuits of interest exist at multiple scales, spanning spatial scales from micrometers to meters, and studies of anesthetic drug effects on circuit members must begin by identifying what cell populations participate in a particular circuit of interest. This is not always trivial, particularly given the mutual reciprocity of connectivity throughout most of the mammalian central nervous system. Anesthetic drugs have documented effects on consciousness, arousal, and pain perception, and alter processing at all anatomic levels of the central nervous system, including spinal cord, brainstem, and cortex. While Moruzzi and Magoun’s initial work focused on the role of the reticular formation in maintenance of arousal and theorized that decreased reticular formation tone could account for the somnolence that occurs with anesthesia (Moruzzi and Magoun, 1949), other distributed circuits are clearly affected by general anesthetics, and may contribute to the functional state of general anesthesia. The thalamus serves to relay most of the cortex’s sensory afferents and motor efferents while it receives reciprocal feedback from different cortical areas (Guillery and Sherman, 2002; Sherman and Guillery, 2002). Within cortex itself, the laminar organization of cortex suggests that particular cell populations may play generic roles in certain types of computation by a given cortical area (Douglas et al., 1989). Finally, immobility with volatile anesthetics appears to result from a suppression of spinal cord central pattern generators (Antognini and Schwartz, 1993), and modulation of painful sensory stimuli by general anesthetics begins in the spinal cord (Hao et al., 2002).

When one considers the shear scale of the problem, with the large number of neurons being affected by general anesthetics, one of the major limitations of electrophysiologic methods that depend upon proximity to small electrodes for localization becomes clear (Figure 1B). Placing electrodes in close proximity to neurons in deep nuclei of the brainstem is technically challenging, and simultaneously placing many electrodes in order to simultaneously sample multiple sites in affected networks compounds the problem. For superficial targets this has been somewhat mitigated by the development of high density electrode arrays, often made of silicon, but traversing large tracts of tissue with multiple perforating shafts is rife with risks of vascular and neuronal injury. This is where assays based on expression of the immediate early genes, most frequently c-fos, shine, because they in theory provide a record that allows post hoc examination of the entire nervous system, or at least as much of the nervous system as the investigators are willing to section and stain. Of course, in exchange for the ability to probe essentially the entire brain simultaneously for expression of IEGs, the temporal resolution is severely limited compared to electrophysiologic methods.

Neuronal identity and sampling bias

In what may be the most reductionistic framing, consciousness is the ability to variably map the same stimulus onto multiple different responses, depending upon the organism’s past experiences and present state. The capability of a conscious organism to shift its behavioral response to particular circumstances results from flexibility in the coupling between neurons, where the sensitivity to an individual neuron to a particular input can be increased or decreased based upon those circumstances to suit the behavioral task at hand (Nicolelis and Fanselow, 2002). This shifting in sensitivity is often measured as a change in the gain of the particular input and the process that changes the gain is known as gain control in the neuroscience literature. Gain control can increase or attenuate the resulting correlation between two different neuronal populations, increasing or decreasing the so-called functional connectivity between the regions. (This is in distinction to the active formation or pruning of synapses, or anatomic connectivity, between the regions and can be distinguished by the ability of the system to rapidly shift between two different functional connectivity states, without the time delay needed for protein expression necessary for the formation or elimination of synapses.) Shifts in cortical gain result in changes in summated synchronized synaptic activity and reflect the changes in effective connectivity seen with the characteristic shifts in EEG with different depths of anesthesia (Friston et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2013).

Yet understanding how a flexible network shifts its responsiveness depends upon understanding how different members of the circuit interact with each other. Different cell types in cortex are well established to have different characteristic firing properties, though these properties can themselves shift (Steriade, 2004), making it difficult to identify particular cell types from electrophysiologic recordings. Moreover, there is no reliable way to identify whether a particular cell in an extracellular electrophysiologic recording is inhibitory or excitatory.

The ability to identify and sample large numbers of particular, genetically distinct cell populations in vivo is the forte of the new genetically encoded indicators of neuronal activity (Lin and Schnitzer, 2016). Moreover, the maturation of microscopy techniques allows the simultaneous sampling of up to thousands of neurons and the same neurons can be recorded over days to weeks to look at time evolution of circuitry. The explosion of techniques for sampling neuronal activity with genetically encoded indicators has resulted from the development of a dizzying array of fluorescent protein sensors (Sanford and Palmer, 2017) combined with advanced microscopy techniques. While genetically encoded voltage indicators have been developed (reviewed in (Yang and St-Pierre, 2016)), the most reliable signal-to-noise over long experimental time frames has been obtained with genetically encoded calcium indicators, of which GCaMP6 (Chen et al., 2013) has some of the best performance characteristics at the time of this writing.

Additional Limits of Single-Unit Electrophysiology

Beyond the limitations outlined above, with respect to difficulty with identifying a recorded cell’s type and morphology, and the invasiveness of the sampling at each spatial location of interest there are other, more subtle disadvantages of relying exclusively on extracellular recordings of single unit electrophysiology for probing circuit function. The quality of single unit isolation falls rapidly as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) falls (Stratton et al., 2012). To combat this problem, most experimentalists adjust electrode placement in vivo to optimize observed signal-to-noise. This introduces two sampling bias problems. First, large cells with large dipoles, predominantly pyramidal cells in cortex with their large apical dendrites and long axons, will be preferentially isolated if maximal SNR is sought by an experimentalist. Secondly, cells with high firing rates are more likely to be identified, because it is easy to move past slowly firing neurons without recording enough spikes to realize the proximity of the electrode tip to the neuron. As a result of this second bias, the reported firing rates from extracellular recording studies tend to be substantially higher than the average firing rate seen with intracellular recording studies and calcium imaging methods (Shoham et al., 2006).

c-fos as a Reporter of Neuronal Activity

Regulatory IEGs are involved in stimulus-transcription coupling (Kovács, 2008). The most frequently used IEG reporter, c-fos mRNA is transcribed and c-Fos protein is transiently expressed in neurons after synaptic stimulation (Sagar et al., 1988), providing an indirect readout of neuronal activity. As alluded to above, c-fos is directly involved in transcription induction in the AP-1 pathway of target cells.

Activation of the AP-1 pathway begins with calcium influx into the neuron through a combination of the N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamine receptor (NDMAR) and voltage dependent calcium channels (e.g., L-type calcium channels). Calcium influx can activate multiple kinases, including CaMKII, CaMKIV, PKA, and MAPK. Fos expression is mainly mediated by MAPK activation, which is relatively slow and requires relatively high calcium increases when compared to the CaMKIV pathway (Chaudhuri et al., 2000; Chung, 2015), with MAPK activity thus reporting strong and continued neural activity (Deisseroth et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2002). Thus expression of c-fos is not triggered by neuronal depolarization per se, as it is expressed at low levels in intact brain, but instead reports phenotypic reprogramming of the cell by either changes in afferent inputs or external stimuli (Luckman et al., 1994). The gene c-fos, and its protein product c-Fos, are transiently expressed after activation of the CAMK pathway results in phosphorylation of the transcription factors CREB and Elk-1, which bind the c-fos promoter (Figure 2) (Chung, 2015). The expressed Fos protein in the nucleus forms a dimer with Jun to make up the AP-1 complex that regulates the expression of “late” genes.

Figure 2.

Signal transduction pathways involving c-fos. Calcium fluxes into the neuron during action potentials via NMDARs and voltage dependent calcium channels. The influx of Ca2+ binds calmodulin, activating CaMKII and then CREB. NMDAR activity also activates RasGRF1, activating the MAPK pathway via Ras and c-Raf activation, with resultant activation of CREB and Elk1. Elk1 binds SRF and acts as a transcription factor at SRE, while activated CREB acts as a transcription factor at CaRE, with resultant expression of c-fos mRNA. Once the c-Fos is transcribed, it binds to jun to form the transcription factor AP-1, which results in transcription of late response genes via the TRE (Chaudhuri et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2007). Abbreviations: NMDAR, N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamine receptor; CaV1.2, L-type Calcium Channel; CaM, calmodulin; CaMKII, calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II; RasGRF1: Ras-guanine nucleotide releasing factor; MEK1/2, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 and 2; MAPK1/3, mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 and 3; SRF, serum response factor; CREB, cyclic AMP response element-binding protein; AP-1, activating protein 1; SRE, serum response element; CRE, cAMP response elements; TRE, 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate response element.

Expression of c-fos begins within 15 minutes of stimulation, with peak expression of c-fos mRNA approximately 30 min post stimulus and peak expression of c-Fos protein approximately 90–120 min post stimulus (Kovács, 1998), but c-Fos expression can be delayed by as much as hours in some areas of brain with certain stimuli (Cullinan et al., 1995). This double peak in expression time course can be exploited through careful experimental design if one stimulus can be placed at the c-Fos expression peak while the other is placed at the c-fos transcription peak.

c-fos in Studies of Anesthetics

Quite a few studies of anesthetics have utilized c-fos as a reporter, and only a cursory review is included here to give some indication of the range of applications for the technique to date. Anesthetic exposure to ether leads to increases c-fos expression in frontoparietal cortex, but decreases c-fos elsewhere compared to the stressor of open field maze exploration (Emmert and Herman, 1999). More frequently, studies have looked for anesthetics to modulate an unanesthetized response to a stimulus. As an example, the response to noxious stimuli has been robustly characterized throughout the CNS (Bullitt, 1990). The lack modulation of spinal cord responses to such stimuli by several sedative hypnotic agents (Shimode et al., 2003) suggests that the analgesic component of general anesthesia must occur elsewhere in the circuit. Anesthetic circuit mechanisms have also been studied as shifts in the balance of c-fos expression in sleep related circuits with volatile anesthetics (Kelz et al., 2008), gaba-ergic agents (Nelson et al., 2002), ketamine (Lu et al., 2008), and dexmedetomidine (Garrity et al., 2015), and c-fos expression in parabracheal nucleus correlates with recovery of righting after isoflurane anesthesia (Muindi et al., 2016). This brief review suggests that investigators have been principally employing c-fos for its advantages in sampling inaccessible structures, such as brainstem nuclei, or for simultaneous sampling of regions that are too spatially separated for visualization in a single optical field of a microscope.

Approaches to Use c-fos as a Reporter of Neuronal Activation

Experimental design

By necessity, mRNA transcription and protein expression take time to occur, and experimental designs must incorporate the appropriate post-stimulus delay in order to utilize these assays. It is also worth remembering that, in addition to the delay, c-fos responses integrate the degree of transcriptional activation over a window of time. Increases of expression of c-fos mRNA are maximal at roughly 30 minutes post-stimulus in most cells. The subsequent translation into Fos protein occurs somewhat later, typically peaking at approximately 2 hours post-stimulus. Some clever experimental designs combine both mRNA and protein assays to test two stimuli in a single experiment, for example combining immunocytochemistry for nuclear Fos expression 2 h post stimulus 1 with in situ hybridization for cytoplasmic c-fos mRNA levels 30m post stimulus 2 (Chaudhuri et al., 1997; Kovács et al., 2001). Good experimental designs will incorporate multiple controls to integrate all of the possible exposures occurring during the hour or so prior to sacrifice. Figure 3A illustrates an example design using an anesthetic emergence protocol from Muindi and colleagues, where the transition from anesthesia with isoflurane to free movement in oxygen is compared to both anesthesia with isoflurane and free movement in oxygen alone.

Figure 3.

A. A sample c-fos experimental protocol. Animals were divided into three groups. Group one (+ISO with emergence) was exposed to isoflurane for 60 minutes, then allowed to recover for 60 minutes before being sacrificed for c-fos histology (red line). Group 2 (+ISO without emergence) was exposed to isoflurane for 60 minutes and then sacrificed. Group 3 (-ISO oxygen only) was exposed to oxygen alone for 60 minutes prior to sacrifice. B. Sections through the parabrachial nucleus were stained for DAPI and c-fos, showing that exposure to isoflurane or oxygen alone were insufficient for increasing c-fos expression. Neurons in parabrachial nucleus increased c-fos expression when the animals were anesthetized and then emerged from anesthesia (seen as the cluster of cells in +ISO with emergence ii and iii). Data from (Muindi et al., 2016). Abbreviations: ISO, isoflurane; cb, cerebellum; vsc, ventral spinocerebellar tract; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle.

Detection and visualization of c-fos

Visualization of c-fos mRNA or protein levels in situ requires immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization methods and expertise with a particular approach may reasonably drive the assay selection (Berghorn et al., 1994; Krukoff, 1998). Tissue processing typically begins with fixation in formalin followed by sectioning, though protocols exist to process tissue directly from frozen section (Sundquist and Nisenbaum, 2005) to save substantial tissue processing time. If in situ visualization is not necessary for the particular experiment, it is possible to purchase RT-PCR probes for FOS commercially (e.g., TaqMan from ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA; PrimePCR SYBR Green Assay, BioRad, Hercules, California). Such technology has been used to study effects of propofol on isolated hippocampal slices in vivo as a model of the amnestic effects of the drug (Kidambi et al., 2010).

Limitations of c-fos as a Reporter of Neuronal Activation

As a result of the imprecise onset of the transcriptional activation, classic c-Fos reporters, particularly based on protein expression, have low temporal resolution. This issue is compounded by the histological approaches that are necessary to visualize the c-fos expression, preventing in vivo utilization of c-fos to detect neuronal activation in real time, though some investigators have attempted to address the non-real time component of c-fos by using a construct of GFP under a c-fos promoter to allow real-time imaging of transcriptional activation in vivo (Barth et al., 2004).

Interpretation of c-fos results must also be tempered with some subtlety. Lack of a Fos response in a population does not preclude the involvement of that population in a functional circuit (Labiner et al., 1993). Indeed, there is no information on connectivity implied by c-fos activation; any such assesments of circuit connectivity have to be assessed via other means. IEGs are not expressed in chronically active neurons, and release of chronic inhibition variably results in an increase in IEG expression (Hoffman et al., 1993). Moreover, neuronal activation can occur without induction of IEGs, possibly because the c-fos promoter has an AP-1 site, allowing for self-inhibition (Schönthal et al., 1989), or because the microRNA miR-7b interacts with the 3′ region of Fos mRNA inhibiting translation (Lee et al., 2006). Alternative technology for attempting to increase both the sensitivity and specificity of activity reporting relative to c-fos has been proposed as well (Sørensen et al., 2016)

Reporting calcium influx with GECIs

Optical tools, including GECIs, give us spatial and genetic control over sampling not present with electrical methods (Scanziani and Häusser, 2009). Multiple fluorescent indicators have been developed for calcium imaging, including FRET based and single fluorophore based indicators and several good comprehensive reviews of available technology exist (Grienberger and Konnerth, 2012; Liem et al., 2004).

Assessing optical indicators: sensitivity, kinetics, and signal-to-noise

The choice of a particular GECI will depend upon matching the signal-to-noise characteristics of the indicator with a temporal resolution sufficient for the response of interest. Concerns for temporal resolution can involve both the ability to resolve event timing and the duration over which the response evolves. In low-signal regimes, such as detecting calcium flux associated with a single action potential, this can amount to detection of only a few photons emitted from the fluorophore, making response detection an exercise in discerning shot noise from the background thermal noise. In practice the optimization of GECIs for signal-to-noise has tended to favor GECIs that emit a large number of photons for a given calcium flux. Of late, isoforms of GCaMP6 (Chen et al., 2013) have been preferred due to their high SNR. GCaMP6 was developed by refining the single fluorophore based G-CaMP (now GCaMP), which fused the C terminus CaM binding peptide to N terminus of cpGFP145.

Imaging Strategies

The particulars in the choice of microscopic technique are beyond the scope of this manuscript and will depend upon the time course of the phenomenon under study, the spatial scale that needs to be sampled, and the type of behavior that must be incorporated into the experiment, but a brief review of some of the issues that must be addressed will follow. To make calcium imaging practical in real world applications requires optimization to maximize not only the change in fluorescence with calcium influx relative to the baseline fluorescence but also maximizing the total number of photons generated and detected by the instrumentation (Scanziani and Häusser, 2009). Microscopy techniques based on 2-photon methods, with their resultant optical sectioning, reduce the amount of background light out of which the response must be detected, increasing the contrast of the image and improving visualization (Svoboda and Yasuda, 2006). This offers a real world advantage over confocal microscopy for in vivo imaging, as maximizing contrast for a given illumination will limit photodamage to tissue and bleaching of the fluorophore in the GECI. That said, some photobleaching is inevitable and may begin to be significant by one hour into an imaging session, leading to a varying baseline fluorescence level and unstable indicator performance over time. This can be partially addressed by normalizing responses to their background, reporting fluorescence signals as a fractional variation relative to their mean: ΔF/Fo.

Temporal resolution, and the nature of motion artifacts captured during imaging, will depend upon the acquisition approach as well. 2 photon resonant-scanning systems with a traditional raster scan path directly trade off spatial resolution or field of view for tempo ral resolution. Random or otherwise directed scan path technology is developing in an attempt to structure the optical sampling path to allow sampling of large numbers of neurons with faster frame rates, but these scan paths risk the introduction of complex aliasing problems with sample movement.

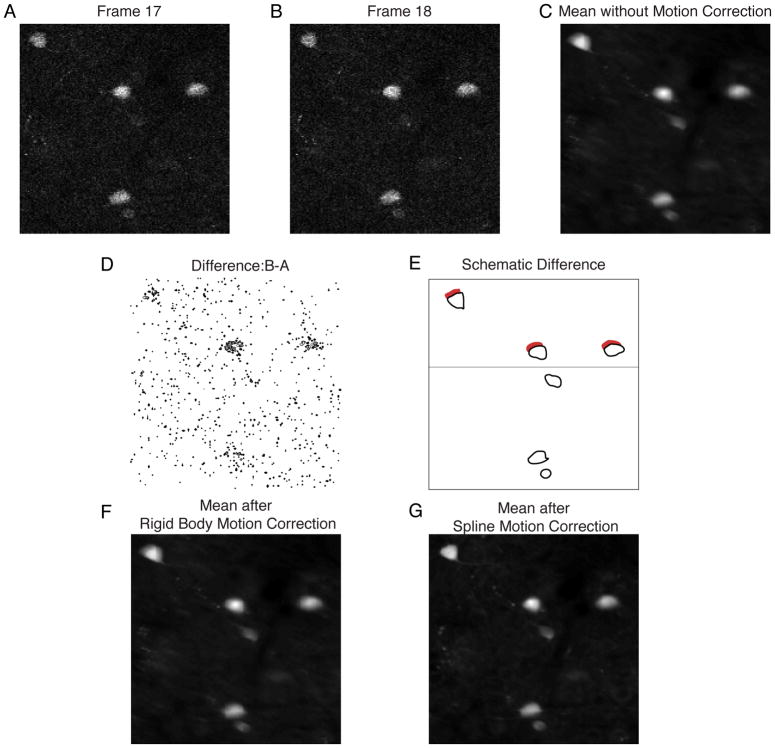

Image registration, also referred to as image stabilization, suppresses the inevitable movement introduced during in vivo sampling (Figure 4). Such registration is the first preprocessing step necessary before neuronal isolation so that correlation structures in the neuronal population can be studied without artifactual contamination. In Figure 4, there is partial movement between frame 17 (panel A) and frame 18 (panel B), highlighted in the difference between the two frames (panel D). This movement blurs the average of the frames in this movie (Figure 4C). At high frame rates, where optical sampling is fast relative to sample movements, it is possible to model motion artifacts as rigid deformations of the mean image, and simply correct for the movement by shifting the entire image. In this case there is a slight improvement in sharpness with a rigid body correction (Figure 4F). When movements begin to approach the time scale of the scan path, the deformations become non-rigid and registration can take considerably more care. As an example, Figure 4D is redrawn schematically in Figure 4E; the neurons above the horizontal line moved before the laser scan path reached them, while the neurons below the horizontal line only moved after the scan path sampled them. This results in a non-rigid deformation of the image within the frame. For suppression of non-rigid deformations the method of Greenberg and Kerr works quite well, with a notable improvement in sharpness in Figure 5G, but is computationally demanding (Greenberg and Kerr, 2009). As would be imagined, registration with random scan paths can be particularly difficult as the movement of the sample relative to the scan path can be hard to suppress.

Figure 4.

Image registration for suppression of motion artifacts. Two frames of an acquired video of a fluorophore are shown with motion occurring between the acquisition of frame 17 (A) and frame 18 (B). C. The motion results in blurring of the mean image. D. The difference image, resulting from B–A. E. A schematic drawing of D, showing that the movement occurred while the laser was scanning through the frame. This is indicated by the thin horizontal line, as those neurons above the line moved before the scan path reached them, while those below the line did not. F. Assuming that all motion between frames occurs as a rigid translation does not substantially sharpen the mean image when compared to C. G. Using a spline approach to model movement as a non-rigid deformation of the image results in a notable sharpening of the mean image compared to C, suggesting that superior registration has been obtained.

Figure 5.

A. Selective expression of GCaMP6 is a cell line and tissue of interest will require titration studies, where serial dilutions are injected into different mice that are then imaged at the latest time point that will be imaged in the study. B. Adequate expression is indicated by fluorescence signal that shows nuclear sparing (circle), whereas complete filling of the neuron (arrow) indicates overexpression.

Targeted expression strategies for GECIs

GCaMP6 is available in a number of forms. For experiments that do not require specific targeting of GECIs by the investigator, transgenic mouse lines are available from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbour, ME) and transgenic flies are available from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN). Plasmids are available through addgene.org (Cambridge, MA). Multiple isoforms of GCAMP6 are available in multiple constructs from the University of Pennsylvania Viral Vector Core (Philadelphia, PA), which is convenient for investigator targeting.

The simplest selective targeting strategy involves focal Injection of the vector with an appropriate vector into the area of interest. More cell-type selective targeting can be achieved with specific promoters for cell types, as in targeting neurons with synapsin promoters. Additionally, floxed targeting with the lox-cre system is possible, allowing the use of transgenic mouse lines that have already been developed to target the populations of interest.

Successful investigator targeting of GCAMP6 expression will require titration studies to ensure adequate expression in the cells of interest for the duration of the sampling period. Initial titration studies with the promoter of interest will require dilution studies (Figure 5) to find appropriate expression levels for a given vector and promoter at the most distant time point necessary for the study. Appropriate expression can be confirmed by fluorescence in the target populations that excludes the nucleus (e.g., the circled neuron in Figure 5B). Nuclear staining with GCaMP (arrowhead in Figure 5B) is suggestive of overexpression and could lead to cellular toxicity or dysfunction.

Experimental Design with GCaMP6

A typical GCaMP experiment begins with targeted expression of the GCaMP in the area of interest. With several promoters in the Pennsylvania Viral Core multiple, small, slow microinjections in cortex spanning from 50 microns below the area of interest to 50 microns above the layer of interest produces reasonable expression. Most AAV-based GCAMP6 vectors will produce adequate expression to begin imaging after 10 days to 2 weeks.

Although it is possible to make injections through a burr hole and then open an imaging window later, the author has found it effective to perform a craniotomy for the injection leaving the dura otherwise intact. Covering the craniotomy with a glass cover slip held in place with methylmethacralate to provide a cranial window later. In this way, any small amount of bleeding associated with turning the bone flap will likely be resorbed by the time expression will allow imaging, increasing the experimental yield per animal used. A head bar to anchor the animal to the microscope headstage can be implanted in the same surgery or in a separate procedure, as is convenient.

Animals can begin to be habituated to the microscope a few days after implantation if any awake imaging is to be performed. To minimize the movement artifact that will result from imaging an awake animal, we have found both a spherical treadmill, and a turntable can work well to dissipate the power generated by the animal’s attempts at locomotion. Habituation to the unusual sensation of being stationary and moving the surface beneath it’s feet may only take one hour or so, depending upon the animal, but several sessions are probably prudent prior to imaging to maximize yield from imaging sessions. Habituation to the open environment has determined when the animal is no longer actively trying to run while attached to the microscope. An otherwise dark, quiet imaging room is also helpful in this regard.

Volatile anesthetic can be effectively delivered via mask to a head-fixed mouse, but some careful consideration should be given to rebreathing and leaking around the mask; monitoring exhaled gas concentrations is good practice. Delivery of intravenous medication will have to be made through catheter stable enough to survive as much movement as can be expected in the experimental design.

Finally, some attention must be made to active warming of the mouse while attached to the headstage, to avoid confounding results from hypothermia. If the animal is to be awake for a portion of this procedure a radiant system may be the most expedient, but experimental contamination with noise from any infrared emitters should be minimized with care. Alternatively, if the animal will not be awake for any portion of the procedure, a typical physiologic warming pad works well.

GECI Data analysis

Extracting meaningful data from recorded videos requires several stages of lprocessing. First, image registration is necessary. Following motion artifact suppression with registration, neuronal isolation can occur based upon the covariation of signal in nearby pixels. Subsequently, the signal from each putative neuron can be extracted as a raw fluorescence trace from the relevant pixels of the motion-corrected recording. The traces can then be normalized relative to the background fluorescence and analyzed as a fluorescence signal by itself as an estimate of the calcium in the imaged portion of the neuron. If the experiment is concerned with identifying action potentials, the impulse response can be modeled as an exponential decay and the fluorescence trace can be deconvolved to produce an estimate of the action potential train that would be capable of generating the resultant fluorescence trace (Figure 6). A computational suite for MATLAB exists that provides the neuronal isolation, normalization, and deconvolution steps in a reasonably efficient manner and is highly recommended (Pnevmatikakis et al., 2015). The quality of the resultant spike train estimate tends to degrade at high firing rates (Theis et al., 2016), which thankfully is less of an issue for anesthesia studies, given the usual low firing rates in the anesthetized state.

Figure 6.

A. After registration, a neuron with appropriate expression levels of GCaMP6 (the circled neuron from 5A) is identified, and the correlation amongst pixels during the movie is used to isolate the pixels of interest in order to extract the fluorescence signal attributed to a single neuron, highlighted in the blue area. B. The fluorescence signal is first normalized to is mean level (top), and the generating spike rate can be estimated through a deconvolution operation (bottom) to within a proportionality constant, assuming stable kinetics of the GCaMP6 signal.

Limitations of GCaMP6

Although targeted expression strategies usually work quite well, not all approaches have success. The author’s own experience, corroborated by others (Dario Ringach, personal communication), is that the fast isoform of GCaMP6, GCaMP6-f, does not produce adequate signal when expressed in GAD67 expressing cell lines. Whether this is due to the fast calcium cycling dynamics in this cell population resulting in very small changes in the intracellular calcium changes or poor expression remains to be completely defined. That said, the higher signal-to-noise slow isoform of GCaMP6, GCaMP6-s, does produce adequate signal to noise to be used in this cell population, so sometimes several different strategies will need to be explored to settle upon one that allows adequate visualization of the properties of interest. Finally, it is necessary to ensure that the expression of GCaMP6 remains adequate to image throughout the time period of interest without accumulating to levels that prove toxic to neurons.

Many limitations of GCaMP6 have to do with needing optical access to the region of interest, restricting use to areas that are optically accessible, within a few hundred microns of the surface of the brain. Moreover, the deeper the area of interest, the greater the required illumination, increasing the risk of photodamage to tissue, increasing the rate of photobleaching of the fluorophoer, and decreasing the signal-to-noise due to surface reflections of the illumination. Fiber photometry offers an opportunity to utilize GCaMP6 to image deeper structures, but the spatial resolution of the data suffers and most reported systems should be thought of as reporting an average calcium concentration for a local population rather than the sub-neuron resolution capable with 2-photon resonant scanning microscopes (Deisseroth, 2016; Liang et al., 2017). This technology may still have potential when combined with novel imaging approaches, however, for simultaneous imaging of spatially separated areas (Kim et al., 2016) and is the focus of ongoing technique development.

Additionally, the potential dependence of an analysis on the deconvolution of neuronal activity estimates depends upon the accuracy of deconvolution algorithms, which may break down at higher firing rates (Theis et al., 2016). An additional concern is that calcium dynamics could shift their relationship to action potential firing in different behavioral regimes, which seems particularly likely when comparing anesthetized versus awake preparations, and this remains an area of active research.

Conclusions

Alternative assays for detecting neuronal activation will continue to be developed as investigators push against the limits of current technology. Two approaches that provide complementary insights into circuit function, and hence may be ideal for probing how anesthetics modulate of circuit function include the IEG c-fos and the GECI GCaMP6. Fos-based approaches detect transcriptional activation of the cell secondary to calcium influx and depend upon detection of gene products in neurons of interest, through immunohystochemical or RT-PCR reporters. Either isolated preparations of neurons of interest or neuronal populations in deep nuclei that are otherwise inaccessible but easily identified on sectioning make ideal targets for c-fos techniques. The temporal resolution of c-fos is, however, limited. In contrast, GCaMP6 generates a fluorescent signal proportional to intracellular calcium concentration. Imaging this signal requires optical access, usually using 2-photon techniques in vivo, making it ideal for assaying activity patterns in large numbers of cortical neurons with defined identities. The temporal resolution of GCaMP6 can detect individual action potentials, but with most conventional microscopes the physical area scanned will decrease with increasing temporal resolution. Extending the reach of GCaMP to deeper areas and understanding the link between calcium dynamics and action potentials remain areas of active research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1K08GM121961).

References

- Abeles M, Goldstein MH. Multispike train analysis. Proc IEEE. 1977;65:762–773. doi: 10.1109/PROC.1977.10559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antognini J, Schwartz K. Exaggerated anesthetic requirements in the preferentially anesthetized brain. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:1244–1249. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199312000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth AL, Gerkin RC, Dean KL. Alteration of Neuronal Firing Properties after In Vivo Experience in a FosGFP Transgenic Mouse. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6466–6475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4737-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghorn KA, Bonnett JH, Hoffman GE. cFos immunoreactivity is enhanced with biotin amplification. J Histochem Cytochem. 1994;42:1635–1642. doi: 10.1177/42.12.7983364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullitt E. Expression ofC-fos-like protein as a marker for neuronal activity following noxious stimulation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:517–530. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G. Large-scale recording of neuronal ensembles. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:446–451. doi: 10.1038/nn1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A, Nissanov J, Larocque S, Rioux L. Dual activity maps in primate visual cortex produced by different temporal patterns of zif268 mRNA and protein expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:2671–2675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A, Zangenehpour S, Rahbar-Dehgan F, Ye F. Molecular maps of neural activity and quiescence. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2000;60:403–410. doi: 10.55782/ane-2000-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung L. A Brief Introduction to the Transduction of Neural Activity into Fos Signal. Dev Reprod. 2015;19:61–7. doi: 10.12717/DR.2015.19.2.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins TFT, Mann EO, Hill MRH, Dommett EJ, Greenfield SA. Dynamics of neuronal assemblies are modulated by anaesthetics but not analgesics. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2007;24:609–614. doi: 10.1017/S0265021506002390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Battaglia DF, Akil H, Watson SJ. Pattern and time course of immediate early gene expression in rat brain following acute stress. Neuroscience. 1995;64:477–505. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K. Form Meets Function in the Brain: Observing the Activity and Structure of Specific Neural Connections. In: Kennedy H, Van Essen DC, Christen Y, editors. Micro-, Meso- and Macro-Connectomics of the Brain. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2016. pp. 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K, Mermelstein PG, Xia H, Tsien RW. Signaling from synapse to nucleus: The logic behind the mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:354–365. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00076-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, Martin KAC, Whitteridge D. A Canonical Microcircuit for Neocortex. Neural Comput. 1989;1:480–488. doi: 10.1162/neco.1989.1.4.480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert MH, Herman JP. Differential forebrain c-fos mRNA induction by ether inhalation and novelty: evidence for distinctive stress pathways. Brain Res. 1999;845:60–67. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01931-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Bastos AM, Pinotsis D, Litvak V. LFP and oscillations—what do they tell us? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;31:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity AG, Botta S, Lazar SB, Swor E, Vanini G, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. Dexmedetomidine-Induced Sedation Does Not Mimic the Neurobehavioral Phenotypes of Sleep in Sprague Dawley Rat. Sleep. 2015;38:73–84. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DS, Kerr JND. Automated correction of fast motion artifacts for two-photon imaging of awake animals. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;176:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grienberger C, Konnerth A. Imaging Calcium in Neurons. Neuron. 2012;73:862–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW, Sherman SM. The thalamus as a monitor of motor outputs. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:1809–21. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S, Takahata O, Mamiya K, Iwasaki H. Sevoflurane suppresses noxious stimulus-evoked expression of Fos-like immunoreactivity in the rat spinal cord via activation of endogenous opioid systems. Life Sci. 2002;71:571–580. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01704-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD, Henze Da, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Buzsáki G. Accuracy of tetrode spike separation as determined by simultaneous intracellular and extracellular measurements. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:401–14. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman GE, Smith MS, Verbalis JG. c-Fos and Related Immediate Early Gene Products as Markers of Activity in Neuroendocrine Systems. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1993;14:173–213. doi: 10.1006/FRNE.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelz MB, Sun Y, Chen J, Cheng Meng Q, Moore JT, Veasey SC, Dixon S, Thornton M, Funato H, Yanagisawa M. An essential role for orexins in emergence from general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1309–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707146105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidambi S, Yarmush J, Berdichevsky Y, Kamath S, Fong W, Schianodicola J. Propofol induces MAPK/ERK cascade dependant expression of cFos and Egr-1 in rat hippocampal slices. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:3–8. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CK, Yang SJ, Pichamoorthy N, Young NP, Kauvar I, Jennings JH, Lerner TN, Berndt A, Lee SY, Ramakrishnan C, Davidson TJ, Inoue M, Bito H, Deisseroth K. Simultaneous fast measurement of circuit dynamics at multiple sites across the mammalian brain. Nat Methods. 2016;13:325–328. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács KJ. Measurement of immediate-early gene activation- c-fos and beyond. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:665–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács KJ. c-Fos as a transcription factor: a stressful (re)view from a functional map. Neurochem Int. 1998;33:287–297. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0186(98)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács KJ, Csejtei M, Laszlovszky I. Double activity imaging reveals distinct cellular targets of haloperidol, clozapine and dopamine D3 receptor selective RGH-1756. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:383–393. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(00)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukoff TL. c-fos Expression as a Marker of Functional Activity in the Brain. Cell Neurobiol Tech Neuromethods 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Labiner DM, Butler LS, Cao Z, Hosford DA, Shin C, McNamara JO. Induction of c-fos mRNA by kindled seizures: complex relationship with neuronal burst firing. J Neurosci. 1993;13:744–751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00744.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Palkovits M, Young WS. miR-7b, a microRNA up-regulated in the hypothalamus after chronic hyperosmolar stimulation, inhibits Fos translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:15669–15674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605781103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee U, Ku S, Noh G, Baek S, Choi B, Mashour GA. Disruption of Frontal Parietal Communication by Ketamine, Propofol, and Sevoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1264–1275. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829103f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Ma Y, Watson GDR, Zhang N. Simultaneous GCaMP6-based fiber photometry and fMRI in rats. J Neurosci Methods. 2017;289:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem EB, Lin CM, Suleman MI, Doufas AG, Gregg RG, Veauthier JM, Loyd G, Sessler DI. Anesthetic requirement is increased in redheads. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:279–83. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MZ, Schnitzer MJ. Genetically encoded indicators of neuronal activity. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1142–1153. doi: 10.1038/nn.4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK. MR imaging in the non-human primate: Studies of function and of dynamic connectivity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:630–642. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Nelson LE, Franks N, Maze M, Chamberlin NL, Saper CB. Role of endogenous sleep-wake and analgesic systems in anesthesia. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:648–662. doi: 10.1002/cne.21685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckman SM, Dyball RE, Leng G. Induction of c-fos expression in hypothalamic magnocellular neurons requires synaptic activation and not simply increased spike activity. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4825–4830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04825.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moruzzi G, Magoun HW. Brain stem reticular formation and activation of the EEG. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1949;1:455–473. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(49)90219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muindi F, Kenny JD, Taylor NE, Solt K, Wilson MA, Brown EN, Van Dort CJ. Electrical stimulation of the parabrachial nucleus induces reanimation from isoflurane general anesthesia. Behav Brain Res. 2016;306:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LO, Smith S, Chen RH, Fingar DC, Blenis J. Molecular, interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:556–564. doi: 10.1038/ncb822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LE, Guo TZ, Lu J, Saper CB, Franks NP, Maze M. The sedative component of anesthesia is mediated by GABA(A) receptors in an endogenous sleep pathway. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:979–84. doi: 10.1038/nn913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolelis MaL, Fanselow EE. Dynamic shifting in thalamocortical processing during different behavioural states. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:1753–8. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perouansky M. The quest for a unified model of anesthetic action: A century in claude Bernard’s shadow. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:465–474. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318264492e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pnevmatikakis EA, Soudry D, Gao Y, Machado TA, Merel J, Pfau D, Reardon T, Mu Y, Lacefield C, Yang W, Ahrens M, Bruno R, Jessell TM, Peterka DS, Yuste R, Paninski L. Simultaneous Denoising, Deconvolution, and Demixing of Calcium Imaging Data. Neuron. 2015;89:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar SM, Sharp FR, Curran T. Expression of c-fos Protein in Brain: Metabolic Mapping at the Cellular Level. Science (80-) 1988;240:1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.3131879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford L, Palmer A. Methods in Enzymology. 1. Elsevier Inc; 2017. Recent Advances in Development of Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Sensors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Häusser M. Electrophysiology in the age of light. Nature. 2009;461:930–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönthal A, Büscher M, Angel P, Rahmsdorf H, Ponta H, Hattori K, Chiu R, Karin M, Herrlich P. The Fos and Jun/AP-1 proteins are involved in the downregulation of Fos transcription - PubMed - NCBI Oncogene. 1989;4:629–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. The role of the thalamus in the flow of information to the cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:1695–708. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimode N, Fukuoka T, Tanimoto M, Tashiro C, Tokunaga A, Noguchi K. The effects of dexmedetomidine and halothane on Fos expression in the spinal dorsal horn using a rat postoperative pain model. Neurosci Lett. 2003;343:45–48. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoham S, O’Connor DH, Segev R. How silent is the brain: Is there a “dark matter” problem in neuroscience? J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sensory, Neural, Behav Physiol. 2006;192:777–784. doi: 10.1007/s00359-006-0117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen AT, Cooper YA, Baratta MV, Weng FJ, Zhang Y, Ramamoorthi K, Fropf R, LaVerriere E, Xue J, Young A, Schneider C, Gøtzsche CR, Hemberg M, Yin JCP, Maier SF, Lin Y. A robust activity marking system for exploring active neuronal ensembles. Elife. 2016;5:e13918. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M. Neocortical cell classes are flexible entities. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:121–34. doi: 10.1038/nrn1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton P, Cheung A, Wiles J, Kiyatkin E, Sah P, Windels F. Action Potential Waveform Variability Limits Multi-Unit Separation in Freely Behaving Rats. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundquist SJ, Nisenbaum LK. Fast Fos: rapid protocols for single- and double-labeling c-Fos immunohistochemistry in fresh frozen brain sections. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;141:9–20. doi: 10.1016/J.JNEUMETH.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda K, Yasuda R. Principles of Two-Photon Excitation Microscopy and Its Applications to Neuroscience. Neuron. 2006;50:823–839. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Anzai Y, Sakurai Y. Automatic Sorting for Multi-Neuronal Activity Recorded With Tetrodes in the Presence of Overlapping Spikes. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2245–2258. doi: 10.1152/jn.00827.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis L, Berens P, Froudarakis E, Reimer J, Román Rosón M, Baden T, Euler T, Tolias AS, Bethge M. Benchmarking Spike Rate Inference in Population Calcium Imaging. Neuron. 2016;90:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, Fibuch EE, Mao L. Regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by glutamate receptors. J Neurochem. 2007;100:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HH, St-Pierre F. Genetically Encoded Voltage Indicators: Opportunities and Challenges. J Neurosci. 2016;36:9977–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1095-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]