Abstract

Patients undergoing allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) are at a very high risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation (HBVr). Lamivudine is commonly used as prophylaxis against HBVr in high risk patients undergoing allo-HSCT. Unfortunately, its efficacy is diminishing due to the development of HBV mutant drug resistant strains. With the availability of newer antiviral agents like Entecavir, Telbivudine, Adefovir and Tenofovir, it is important to assess their role in HBVr prophylaxis. A comprehensive search of seven databases was performed to evaluate efficacy of antiviral prophylaxis against HBVr in allo-HSCT patients (PubMed/Medline, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CINAHL, and ClinicalTrials.gov - June 21, 2017). We identified 10 studies with 2067 patients undergoing allo-HSCT; these primarily evaluated the use of Lamivudine and Entecavir as prophylaxis against HBVr in patients undergoing allo-HSCT because there was little or no data about Adefovir, Telbivudine, or Tenofovir as prophylaxis in this specific patient population. Thus, included studies were categorized into two main prophylaxis groups: Lamivudine and Entecavir. Results of our meta-analysis suggests that Entecavir is very effective against HBVr, although further clinical trials are required to test efficacy of new antivirals and explore the emerging threat of drug resistance.

Keywords: Prophylaxis, Chemoprophylaxis, Hepatitis B virus reactivation, Allogeneic stem cell transplantation, Immunosuppression

Introduction

Worldwide, two billion people have evidence of past or present infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), with the highest prevalence observed in Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia.1 HBV can cause acute or chronic liver disease, the latter of which may lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, or hepatocellular carcinoma.2,3 Patients with malignancies undergoing chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation are highly susceptible to developing HBV reactivation (HBVr) (Table 1). A meta-analysis performed with data from patients with Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma receiving rituximab chemotherapy, found that among anti HBc +ive or HBsAg +ive cases, there was a twofold higher rate of HBVr.4 In cases of hematological malignancies, especially when a patient is undergoing allo-HSCT, the host's immune system may tip its balance due to the nature of the underlying hematological disease as well as the aggressive treatment used to treat it, both of which may lead to prolonged periods of immunosuppression.5 In patients with past HBV infection, during period of immunosuppression, the HBVr rates are highest in HbsAg +ive subset and lowest in those patients who experienced a clinical cure.6 Biological cure of HBV infection is defined by loss of covalently closed circular DNA from hepatocytes.7 However, clinical cure is defined as loss of HBsAg and seroconversion to anti-HBs. HBVr carries a very high mortality rate when compared with an acute onset HBV infection.

Table 1. Definitions of terminology for HBV reactivation risk stratification.

| TERMS | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| High Risk (HR) recipients | HBsAg +ve only or HBV DNA quantitative +ve (greater than 2000IU/ml) only, HBsAg +ve but HBV DNA quantitative -ve (less than 2000IU/ml), Anti HBc +ve, Anti HBc +ve and Anti HBs +ve, Prior HBV Vaccination Status Unknown. |

| High Risk (HR) Donors | Any serology positive i.e HBsAg +ve, Anti HBc +ve, Anti HBsAg +ve or HBV DNA quantitative +ve |

| Low Risk (LR) recipients | HBV DNA quantitative -ve, Anti HBs +ve, HBsAg -ve, Anti HBc -ve, Anti HBs -ve |

| Low Risk (LR) Donors | HBV DNA quantitative -ve, HBsAg -ve, Anti HBc -ve, Anti HBs -ve or |

| Hepatitis B Virus reactivation (HBVr) | Reappearance of serum HBV-DNA or its marked increase (greater than 1 log IU/mL) from baseline with or without acute change in liver function tests (Increase in ALT ≥ 2 times the ULN of <40 IU/L), jaundice, and Anti HBc-IgM +ive. |

In the US alone, 8000 allo-HSCTs are performed annually. More than 60% of patients, who are HbsAg +ive prior to transplant, face HBVr. Lamivudine (LAM) is known to prevent HBVr and can be used prophylactically in chronic HBV infected patients undergoing treatment for hematological malignancies. However, the emergence of LAM resistant mutant strains have led to its decreased efficacy.8 With the availability of newer antiviral agents such as Entecavir (ETV), Telbivudine (TBV), Adefovir (ADV), and Tenofovir (TDF), it is important to assess their role as prophylaxis in preventing HBVr after allo-HSCT. Currently, there are no updated consensus recommendations regarding the use of these antivirals in the era of LAM drug resistance. Our aim in this review was to comprehensively search and evaluate current medical literature and update clinicians on best evidence-based practices regarding the use of antiviral prophylaxis for hepatitis B reactivation in high risk patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Methods and Materials

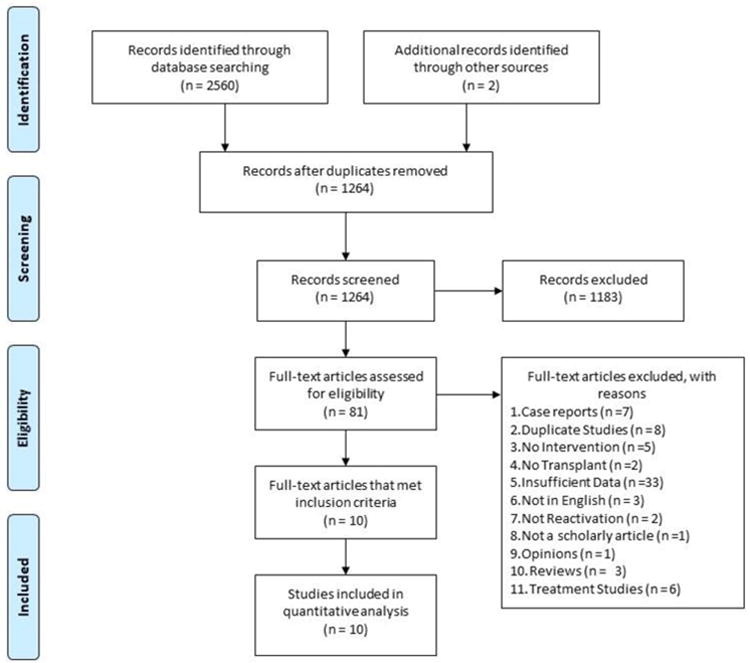

A literature review was performed using methods specified in the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses9 (Fig 1). Controlled vocabulary search terms (MeSH and EmTree), as well as keywords, were used to search the following seven databases for studies that examined hepatitis B reactivation after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: PubMed/Medline, Elsevier/Embase, Elsevier/Scopus, Wiley/Cochrane Library, Thomas-Reuters/Web of Science, EBSCO/CINAHL, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Under supervision of a research librarian (CH), all databases were searched from the date of their inception to the date literature searches were completed on June 21, 2017. Reference lists of, and citations to the articles eventually selected from the database searches, were also screened, as was the reference list of a related, recently published review.10

Figure 1. Prisma Flow Chart.

Two independent reviewers (AS, AM) initially screened all retrieved titles and abstracts for relevance. The same protocol was used to screen the full text of articles initially selected. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Inclusion criteria for our review were as follows: (i) Studies with high risk (HR) allo-HSCT recipients and donors (Table 1 Definition of Risk Stratification) (ii) Patients who received allo-HSCT (MUD, MRD, Haplo, Cord) (iii) Patients who received antivirals peri allo-HSCT to prevent HBVr (iv) Low risk (LR) recipients used as a comparison group, who may or may not have received antivirals peri allo-HSCT (Table 1). Case studies, letters, opinions, reviews, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded as were articles not in English.

To measure study quality, we used a previously validated NIH 14-point scale, with yes or no assigned to each question.11 Studies were categorized into low quality, fair quality, and good quality groups, as per criteria by two independent raters. One author (AS) extracted the data, which was subsequently examined by a second author (SM). The following variables were analyzed: author, year, study design, number of subjects (intervention and control groups), antiviral (agent, dose, duration of treatment), and HBV related outcomes (HBVr or no HBVr). The primary outcome for our review was incidence of HBVr in patients receiving antiviral prophylaxis. According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), HBVr is defined as a marked increase in HBV replication (≥ 2 log increase from baseline levels or a new appearance of HBV DNA to a level of ≥ 100 IU/mL) in those with previously stable or undetectable levels.

Results

We found 2560 studies through the database searches. Citation analysis of the most relevant articles revealed an additional two articles. Of the 1264 articles that remained after duplicates were removed, 1183 were excluded because of irrelevance to the topic. Strict inclusion criteria, as outlined above, were applied to the full text of 81 articles. Of these, 10 met the full set of criteria12-21 and were analyzed in this review. Nine studies were retrospective cohort and one was a prospective cohort with 2067 patients in total, of whom 611 were HR and 1456 were LR. Population size among individual studies ranged from 4 to a maximum of 703 patients. These studies were published in seven different countries, including Australia, China, India, Italy, Japan, Turkey and the United Kingdom between 2002 and 2016. The baseline characteristics are given in Table 2 and 3. Based on the antiviral prophylaxis agent, studies were divided into two groups: LAM prophylaxis and ETV prophylaxis. Duration of planned prophylaxis ranged between 6 and 30 months. All patients underwent allo-HSCT. All patients in the prophylaxis group were given either 100 mg per day LAM or 0.5 mg per day ETV during the peri-transplant period. Random-effects model was applied while doing meta-analysis using comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA) software version 2.

Table 2. Efficacy of LAM Prophylaxis in Allogenic HSCT Recipients.

| Authors Year Design Place of study | Total (N) | Intervention, Dose, Duration | HPRP | High Risk Recipient(R) HBV Serology\High Risk Donor(D) HBV Serology | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerva 2016 Retro Italy | High Risk=45 vs. Low Risk=211 | LAM 100mg/day (30 mo) vs No Prophy | 39\45 | (R)Resolved HBV (27), Inactive carrier (3) (D) Resolved HBV (15) |

High Risk=2/45(4.4%) HBVr Low Risk=2/211(0.94%) HBVr |

| Gupta 2016 Retro India | High Risk=7 vs Low Risk=95 | LAM 100mg/day or 3mg/kg/day in <12yo (6 mo) vs No Prophy | 7\7 | (R)Resolved HBV (7) (D) Vaccinated (1) |

High Risk =0/7(0%)HBVr Low Risk=20/95(21.05%) HBVr |

| Giaccone 2010 Retro Italy | High Risk=30 vs Low Risk=87 | LAM 100mg/day (40 mo) vs No Prophy | 16\30 | (R) Resolved HBV (25), Active HBV(2) (D) Active HBV (3) |

High Risk= 3/30(10%) HBVr Low Risk=0/87(0%) HBVr |

| Topcuoglu 2010 Retro Ankara, Turkey | High Risk=23 vs Low Risk=680 | LAM 100 mg/day (6-12 mo) vs No Prophy | 14\23 | (R) Inactive carriers (14) (D) Active HBV (6), Unknown HBV Serology (3) |

High Risk= 4/23(17.39%) HBVr Low Risk= 3/680(0.44%) HBVr |

| Moses 2006 Retro London | High Risk=15 vs Low | LAM 100 mg/day (6 mo) vs No Prophy | 8\15 | (R) Resolved HBV (8), Inactive carrier(2) (D) Resolved HBV (5) |

High Risk= 3/15(20%) HBVr Low Risk= Data not available |

| Lau 2002 Retro china and Australia | High Risk=20 vs High Risk=20 | LAM 100 mg/day (13 mo) vs No Prophy | 20\20 | (R) Active HBV (20) | High Risk(prophy)=1/20(5%) HBVr High Risk (no prophy) =10/20(50%) HBVr |

| Shang 2016 Retro China |

LAM GROUP High Risk=88 Low Risk=31 ETV GROUP High Risk=75 Low Risk=22 |

LAM 100mg/day (119) vs. ETV 0.5mg/day (97) (24 mo for both) | LAM= 119\119 ETV= 97\97 |

LAM Group: (R) Active HBV (88) ETV Group: (R) Active HBV (75) |

LAM: High Risk = 28/88(31.81%) HBVr Low Risk = 0/31(0%) HBVr ETV: High Risk = 2/75(2.67%) HBVr Low Risk = 0/22(0%) HBVr |

Abbreviations: N= total number of participants, Retro= retrospective study, LAM= lamivudine, mo= months, yo= years old, prophy=prophylaxis, pts= patients, (R)= recipient, (D)= donor, HBV= hepatitis B virus, HBVr= hepatitis B virus reactivation, HPRP= high risk patients received prophylaxis

Table 3. Efficacy of Entecavir Prophylaxis in Allogenic HSCT Recipients.

| Study Author, Year Design, Place of study | Total (N) | Intervention, Dose, Duration | HPRP | High Risk Recipient(R) HBV Serology High Risk Donor(D) HBV Serology | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liao, 2015 Pros, China | High Risk=57 vs Low Risk=105 | ETV 0.5mg/day (12 mo) vs No Prophy | 57\57 | (R) Active HBV (25), Resolved HBV (32) | High Risk=1/57(1.75%) HBVr Low Risk=0/105(0%) HBVr |

| Aoki, 2014 Retro, Tokyo, Japan | High Risk=4 | ETV 0.5mg/day (12.5 mo) | 4\4 | (R) Active HBV (4) | High Risk=0/4(0%) HBVr |

| Shang, 2016 Retro, China |

LAM GROUP High Risk=88 Low Risk=31 ETV GROUP High Risk=75 Low Risk=22 |

LAM 100mg/day (119) vs. ETV 0.5mg/day (97) (24 mo for both) | LAM= 119\119 ETV= 97\97 |

LAM Group: (R) Active HBV (88) ETV Group: (R) Active HBV (75) |

LAM: High Risk = 28/88(31.81%) HBVr Low Risk = 0/31(0%) HBVr ETV: High Risk = 2/75(2.67%) HBVr Low Risk = 0/22(0%) HBVr |

| Tsuji, 2012 Retro, Tokyo, Japan | High Risk=158 vs High Risk=69 | LAM 100mg/day (12) ETV 0.5mg/day (146) vs No Prophy | 158\158 | (R) Resolved HBV (140), Active HBV (18) | High Risk(Prophy)=0/158(0%) HBVr High Risk (No Prophy) =4/69(5.79%) HBVr |

Abbreviations: N= Total number of participants, Prosp= Prospective, Retro= Retrospective study, LAM= lamivudine, ETV= entecavir, mo= months, yo= years, Prophy= prophylaxis, pts= Patients, (R)= recipient, (D)= donor, HBV= Hepatitis B virus, HBVr= Hepatitis B virus reactivation, HPRP: High risk patients received prophylaxis

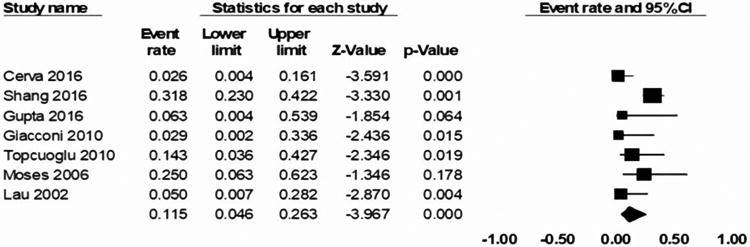

A. Efficacy of Lamivudine prophylaxis against HBV reactivation

This group included seven studies with 323 HR and 1351 LR patients (n= 1674), as summarized in Table 2. Six studies used LAM as prophylaxis for HR patients (n= 104) undergoing allo-HSCT. Only one study used either LAM or ETV as prophylaxis for HR patients (n=163) as prophylaxis. Shang et al 18 compared both ETV and LAM simultaneously, and thus their data were included in both the LAM and ETV analysis. Duration of LAM prophylaxis ranged from six to 30 months for different studies. Of the 323 HR patients, only 267 patients received prophylaxis. The patients who did not receive any prophylaxis had negative HBV serology, but they were placed in the HR group due to their donors' positive HBV serology. Lau et al 17 compared HR patients who received LAM prophylaxis with no prophylaxis and found an HBVr rate of 5% and 50% for each group, respectively. Shang et al 18 reported that HR patients who received LAM prophylaxis (n=88) had an HBVr rate of 31.81%, as compared to the HR patients who received ETV prophylaxis (n=75) who had an HBVr rate of only 2.67%. The cumulative incidence rate of HBVr in their study at 6, 12, and 24 months for LAM prophylaxis was 3.0%, 7.0%, and 24%, and for ETV prophylaxis was 0%, 0%, and 2.0%, respectively. Our analysis for LAM prophylaxis revealed an aggregated HBVr event rate of 11.5% in HR patients (range: 5-30%, 95% CI: 0.046-0.263, p < 0.000, z value = -3.967). Mean follow-up time was 18.7 months (range = 6 to 40 months).

B. Efficacy of Entecavir prophylaxis against HBV reactivation

This group included a total of four studies (n=609), as summarized in Table 3, with 451 HR patients and 158 LR patients. Four studies used ETV as prophylaxis for HR patients (n=294) undergoing allo-HSCT, and only one study gave ETV to a LR group (n=22). Two studies used either LAM or ETV for HR prophylaxis (n=321). Tsuji et al 21 compared a HR population, which received either ETV (n=146) or LAM (n=12) prophylaxis with a group of HR patients who did not receive any prophylaxis (n=69), and found an HBVr rate of 0% vs 5.79%, respectively. Our analysis revealed that the four-study aggregated HBVr event rate with ETV prophylaxis in HR patients (n=282) was 1.9% (range: 0% - 2.67%, 95% CI: 0.007-0.050, p < 0.000, z value: -7.776). Random-effects model was once again applied to this analysis. Mean follow-up duration was 16.1 months (range 12-24 months). The mean duration of follow up for Tsuji et al 21 was not clearly stated. Only two of the included studies had LR groups, and among them chemoprophylaxis was used in one study while no prophylaxis was given in the second study.18,19 Irrespective of prophylaxis use, no HBVr was documented in LR group. Despite the limitation of a retrospective study design, lack of prospective randomized data, and limited numbers of study subjects, ETV prophylaxis appeared to be highly effective against HBVr in this subgroup.

Discussion

Seven drugs are currently approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection: interferon (INF) (conventional and PEGylated) and five nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (LAM, ETV, TDF, TBV and ADV). Recommendations from leading liver disease associations include the use of INF, ETV, TDF and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) as initial treatment for chronic HBV infection.22-25 In treatment-naïve patients, TDF or ETV are generally preferred agents due to their good antiviral activity and low risk of resistance by mutant viral strains.26 TAF is reported to be superior due to its better side effect profile when compared to TDF.27,28 INFα has limited efficacy (30 to 40 %) and high a incidence of adverse events.29

HR patients undergoing allo-HSCT carry significant risk of HBVr during immunosuppression therapy for Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD). In patients undergoing chemotherapy for various hematological malignancies, the reported incidence of HBVr is 32.08% to 60%.30,31 The network meta-analysis by Zhang et al 10 compared the use of five antivirals for prophylaxis of HBVr in immunosuppressed patients with hematological malignancies and found superior efficacy for ETV (88%) and TDF (90%) when compared to LAM, ADV and TBV. Our meta-analysis focused on efficacy of HBVr prophylaxis specifically among allo-HSCT patients and analyzed data from ten studies in which 611 HR patients received prophylaxis. No studies were available which used TDF, TBV and ADV for HBVr prophylaxis in HR allo-HSCT patients. The aggregated HBVr event rate was 1.9% in the ETV group vs 11.5% in the LAM group.

Data on LAM resistance in patients undergoing allo-HSCT is very limited. Data from other studies using various HR populations suggested that after continuous use of LAM for a few years, the emergence rate of resistant HBV mutant strains was very high (70% after use for four years).32,33 A multicenter US-Canadian trial studied LAM as HBVr prophylaxis in 77 liver transplant candidates, and discovered that YMDD mutations emerged in 15 (32%) transplant patients and 6 (22%) non-transplant patients.34 In a similar study of liver transplants, 43% of patients were given LAM prophylaxis only and 57% were given combined LAM and hepatitis B immunoglobulin. HBVr in the LAM only prophylaxis group was 15%, whereas HBVr in the combined prophylaxis group was 18%.35

Fung et al 36 used ETV (with a median duration of 5 months) as HBVr prophylaxis in 80 patients undergoing liver transplant due to HBV related complications and at median follow-up of 26 months, there was 91% loss of HbsAg and 98.8% clearance of HBV DNA. Emerging evidence from SOT patients regarding drug resistant strains with LAM use is highlighting the need of testing alternative novel antivirals for patients undergoing allo-HSCT.34,35,37 The American Society of Transplant (AST) suggests either TDF or ETV should be used in both liver and other solid organ transplant patients with HBV infection because of their high efficacy and low resistance. The antiviral should be given for an indefinite period if patients have active disease (HBsAg +ive or rising PCR for HBV DNA).

In clinical practice, the choice of antiviral regimen is based on factors such as prior exposures, drug resistance, potential drug interactions and side effects. Some transplant centers use combination antiviral therapy during the peri-transplant period, including combination ETV and TDF, but there is limited published data to support combination therapy. In cases of non-liver solid organ transplants, patients with chronic HBV should be evaluated by a specialist in the field to determine the need for HBVr prophylaxis.38 TDF has been without resistance after 6 years of use in chronic HBV patients and has shown promising results as chemoprophylaxis for HBVr in liver transplant recipients.39 In the setting of allo-HSCT, there is limited data on chemoprophylaxis with TDF in preventing HBVr post allo-HSCT. A case report of two allo-HSCT patients with GVHD who were given TDF 245 mg per day orally for the treatment of HBVr resulted in a progressive and continual decrease in hepatitis B viral load 40.

Some of the limitations of our meta-analysis are directly attributable to the number and quality of studies available for analysis. For example, no randomized controlled trials were found and thus our analysis was limited to retrospective and prospective cohort studies. The overall number of studies included in our analysis was small and many had small sample sizes. Additionally there was significant heterogeneity among patient population, ethnicity, primary diagnoses, conditioning regimens, and prophylaxis duration for patients who were undergoing allogenic HSCT. There were limited data for head-to-head comparison of LAM with ETV or other novel antivirals. The duration for LAM prophylaxis varied among studies, which may account for differences in HBVr rates. We have summarized currently available guidelines and specialty group recommendations available for prophylaxis of HBVr (Table 4). Our project highlights the need for well-designed, prospective clinical trials to establish efficacy of ETV and other novel antivirals for HBVr chemoprophylaxis for patients undergoing allogenic stem cell transplantation.

Table 4. Summary of recommendations and guidelines for prophylaxis of HBV reactivation after solid organ transplantand Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

| Specialty | Recommend | ations and guidelines for prophylaxis of HBV reactivation after organ transplantation. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCCN 2.2017 | Prophylaxis indication | If HbsAg +ve, HBV DNA quantitative +ve or anti HBc +ve but HbsAg -ve and anti HBs +ve, consult Infectious Disease to determine possible antiviral prophylaxis. If HbsAg +ve and/or HBeAg +ve titers are high or increasing HBV DNA quantitative viral load, consider delay in transplant and antiviral therapy should be given for 3-6 months before conditioning. | |

| Recommended Agents | Lamivudine 100mg/day PO, Entecavir 0.5mg/day PO (nucleoside-treatment-naïve with compensated liver disease) or 1mg/day PO (In lamivudine refractory or known lamivudine resistant patients) (Preferred), Tenofovir DF 300mg/day PO (Preferred) | ||

| Role of Vaccine | 3 doses of HBV vaccine strongly recommended 6-12 months following HSCT. HBV vaccination strongly recommended in HBV naïve patients i.e. HbsAg -ve, anti HBs -ve and anti HBc -ve. |

||

| Monitoring schedule | Both donor and recipient should be screened for HBV, HCV and HIV before undergoing HSCT. Monitor all Allo-HSCT patients at least 6-12 months post-transplant. | ||

| AASLD | Prophylaxis indication | HBsAg (+) HBV DNA ≥ 2000 U/mL, HBsAg (+) HBV DNA < 2000 U/mL, HBsAg (-) antiHBc (+) [Close mon/treat if HBV DNA (+) or rituximab/stem cell transplant] | |

| Recommended Agents | LAM (LdT) preferred Entecavir / Tenofovir | ||

| Role of Vaccine | For HBsAg (-) antiHBc (-) antiHBs (-) | ||

| Monitoring schedule | Every 1-3 mo/treat if HBV DNA (+) for HBsAg (-) antiHBc (+) | ||

| ASCO 2015 | Prophylaxis indication | HBsAg +ve, HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc–positive patients anticipated to receive B cell– depleting agents, for 6 – 12 months. Insufficient data to determine the optimal strategy for HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc–positive patients receiving therapies not known to cause a high risk of reactivation. For this latter group of patients, the panel suggests monitoring of HBV DNA and ALT levels approximately every 3 months during therapy and initiation of on-demand antiviral therapy if there is evidence of HBV reactivation | |

| Recommended Agents | Recommended but not specified, Lamivudine (drug resistance issues) and Entecavir (preferred) | ||

| Role of Vaccine | Not Specified | ||

| Monitoring schedule | Monitor HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc–positive patients for HBV reactivation with HBV DNA and ALT testing approximately every 3 months during therapy and start antiviral therapy promptly if HBV reactivation occurs | ||

| AGA | Prophylaxis indication | Only for reactivation group moderate risk (1-10%) and high risk (more than 10%) and no prophylaxis to low risk (less tha 1%) group. | |

| Recommended Agents | Entecavir, potentially tenofovir are preferred and may be superior to lamivudine due to drug resistance. | ||

| Role of Vaccine | Not Specified | ||

| Monitoring schedule | Not Specified | ||

| AGIHO of DGHO 2016 | Prophylaxis indication | HBsAg +ve / anti-HBc +ve and HBV DNA quantitative +ve recipients / anti-HBc +ve and HBV DNA quantitative -ve recipients, HBV DNA quantitative +ve donors (antivirals up to 6 months post-HSCT) | |

| Recommended Agents | Lamivudine 100 mg/day, Entecavir 0.5–1.0 mg/day, Tenofovir 245 mg/day | ||

| Role of Vaccine | Not Specified | ||

| Monitoring schedule | HBV-DNA until anti-HBs +ve and HBV-DNA -ve | ||

| AST 2013 | Prophylaxis indication | Donor HbsAg +ve, Anti HBc IgM +ve, Anti HBc IgG +ve and Recipient Anti HBs +/-ve | |

| Recommended Agents | Lamivudine 100mg/day PO and HBIG 20,000 units/dose I/V, Lamivudine 100mg/day PO and Adefovir 10mg/day PO, Entecavir 0.5mg/day PO and Tenofovir 300mg/day PO ± HBIG 20,000units/dose I/V. | ||

| Role of Vaccine | Vaccination as stratagem to discontinue HBIg or antivirals not advised. | ||

| Monitoring schedule | HbsAg +ve Liver transplant recipients need indefinite treatment. | ||

| 5th ECIL 2013 | Prophylaxis indication | All HBsAg +ve, Anti HBc +ve, HBV serology -ve recipient with Anti HBc +ve donor (Duration of antivirals: up to 12 months post HSCT) | |

| Recommended Agents | Choice of treatment depends upon HBV DNA levels and anticipated duration of use: a) HBV DNA < 2000 IU/mL: any antiviral can be used b) HBV DNA > 2000 IU/mL: entecavir(0.5mg/day) or tenofovir (245 mg/day) c) use greater than 12 months = entecavir(0.5mg/day) or tenofovir (245 mg/day). |

||

| Role of Vaccine | Consider vaccinating seronegative HBV patients. | ||

| Monitoring schedule | All patients should be screened for HBV (HBsAg, anti-HBc, HBV DNA quantitative -DNA, anti-HBs, Check for HDV if HBsAg +ve) and if viral hepatitis is suspected should undergo expert liver evaluation before HSCT/chemotherapy. Monitor HBV DNA and ALT every 3 months. Screen HSCT Donors for HBV (HBsAg, anti-HBc, HBV DNA quantitative -DNA, anti-HBs). | ||

| CIBMTR, NMDP, EBMT, ASBMT, CBMTG, IDSA, SHEA, AMMI, | Prophylaxis indication | HbsAg +ve, Anti HBc +ve or HBV DNA +ve recipient or HBV DNA +ve donor. | |

| Recommended Agents | Lamivudine (100 mg/day up to 6 months post HSCT in recipient), Entecavir (at least 4 weeks or until HBV DNA -ve for donor). | ||

| CDC Published in ASBMT 2009 | Role of Vaccine | All HBV -ve recipients with HBsAg +ve donors should be vaccinated preferably before chemotherapy for the initial 2 doses 3 to 4 weeks apart followed by a third dose 6 months later which should be given ideally before HSCT. Give HBIG (0.06 ml/kg) prior to stem cell infusion If: vaccination is impractical pre-transplant or Anti-HBs titer is 10 IU/L post vaccination. Revaccinate recipients, after immune recovery, with 1 to 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine who's Anti-HBs titer fail to rise but remain seronegative post-transplant. |

|

| Monitoring schedule | Monitor ALT monthly for first 6 months if at the time of harvest both donor and harvest cells are HBV DNA -ve. If ALT start rising, test recipient for HBsAg or HBV DNA. Anti-HBs levels should be monitored every 3 months and reduction in its titer should prompt HBV DNA testing. After discontinuation of antivirals, biweekly testing with ALT and HBV DNA quantitative should be done to detect rebound HBVr and hepatitis. Perform liver biopsy in patients with active HBV (HBsAg +ve/HBV DNA quantitative +ve) because pre-existing cirrhosis can increase treatment related mortality. Test both Recipient and donor before transplant using following assays: HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc. If HBsAg and Anti HBc return +ve, do further testing by HBV DNA quantitative. Avoid transplant from HBsAg +ve or HBV DNA quantitative +ve donors to HBV-naïve recipients however, it is not absolutely contraindicated. | ||

Abbreviations: National comprehensive cancer network (NCCN), Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology (AGIHO/DGHO), European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL), Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), The National Marrow Donor Program(NMDP), The European Blood and Marrow Transplant Group (EBMT), The American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT), American gastroenterology association (AGA), The Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group (CBMTG), The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), The Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Canada (AMMI), The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In conclusion, patients undergoing allo-HSCT need to be routinely screened during the pre-transplant period to be stratified into HR and LR for HBVr. HR patients should receive effective prophylactic antiviral agents during the peri-transplant phase to lower the HBV DNA load before transplantation and to decrease the risk of HBVr after transplantation. Planned monitoring of HBV DNA by PCR and immune markers of HBVr after transplantation should be routinely performed. LAM is associated with high resistance rates, but resistance data is not well documented in the hematopoietic stem cell transplant population. Furthermore, there is little or no published data about the efficacy of Adefovir, Telbivudine, and Tenofovir as HBVr prophylaxis in this specific patient population. However, based on the currently available published data in allo-HSCT patients, ETV is an effective prophylactic agent against HBVr.

Figure 2. Efficacy of LAM prophylaxis in preventing HBV reactivation among allo-HSCT patients.

Figure 3. Efficacy of ETV prophylaxis in preventing HBV reactivation among allo-HSCT patients.

Highlights.

Efficacy of prophylactic Entecavir against HBV reactivation in allogenic stem cell transplant recipients is very promising.

Prolonged Lamivudine use is associated with drug resistance but resistance data is not well documented in the hematopoietic stem cell transplant population.

Aggregated data reveals the rate of HBV reactivation with Lamivudine prophylaxis is inferior when compared to efficacy of prophylactic Entecavir.

Our project highlights the need for well-designed, prospective clinical trials to establish efficacy of tenofovir and other novel antivirals for HBV chemoprophylaxis for patients undergoing allogenic stem cell transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure statement: This work was supported in part by grant P30 CA023074 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Abbreviations

- ADV

Adefovir

- allo-HSCT

Allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- ETV

Entecavir

- HBVr

HBV reactivation

- anti HBc

Hepatitis B core antibody

- anti HBs

Hepatitis B surface antibody

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HR

High risk

- INF

Interferon

- LAM

Lamivudine

- LR

Low risk

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- TBV

Telbivudine

- TDF

Tenofovir

- TAF

Tenofovir alafenamide

Footnotes

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with this manuscript. The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30(12):2212–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lalazar G, Rund D, Shouval D. Screening, prevention and treatment of viral hepatitis B reactivation in patients with haematological malignancies. British journal of haematology. 2007;136(5):699–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2009;49(5 Suppl):S45–55. doi: 10.1002/hep.22898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong HJ, Ni LN, Sheng GF, Song HL, Xu JZ, Ling Y. Risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients receiving rituximab-chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2013;57(3):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bessone F, Dirchwolf M. Management of hepatitis B reactivation in immunosuppressed patients: An update on current recommendations. World journal of hepatology. 2016;8(8):385–394. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i8.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habib SSO. Hepatitis B immune globulin. Drugs Today. 2007;43(6):379–394. doi: 10.1358/dot.2007.43.6.1050792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nassal M. HBV cccDNA: viral persistence reservoir and key obstacle for a cure of chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2015;64(12):1972–1984. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pallier C, Castera L, Soulier A, et al. Dynamics of hepatitis B virus resistance to lamivudine. Journal of virology. 2006;80(2):643–653. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.643-653.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151(4):W65–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang MY, Zhu GQ, Zheng JN, et al. Nucleos(t)ide analogues for preventing HBV reactivation in immunosuppressed patients with hematological malignancies: a network meta-analysis. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2017;15(5):503–513. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2017.1309291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NIH. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cerva C, Ricciardi A, Maffongelli G, et al. HBV reactivation rate in hematological patients in lamivudine (LMV) prophylaxis that underwent a prolonged follow up. Bone marrow transplantation. 2016;51:S199. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta A, Punatar S, Gawande J, et al. Hepatitis B-related serological events in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients and efficacy of lamivudine prophylaxis against reactivation. Hematol Oncol. 2016;34(3):140–146. doi: 10.1002/hon.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giaccone L, Festuccia M, Marengo A, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and efficacy of prophylaxis with lamivudine in patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(6):809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.12.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Topcuoglu P, Soydan E, Idilman R, et al. Allogeneic hematopoetic cell transplantation in patients positive for hepatitis B surface antigen. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16(2):S288. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moses SE, Lim ZY, Sudhanva M, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis and treatment of hepatitis B Virus-exposed recipients receiving reduced intensity conditioning hematopoietic stem cell transplants with alemtuzumab. J Med Virol. 2006;78(12):1560–1563. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau GK, He ML, Fong DY, et al. Preemptive use of lamivudine reduces hepatitis B exacerbation after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Hepatology. 2002;36(3):702–709. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shang J, Wang H, Sun J, et al. A comparison of lamivudine vs entecavir for prophylaxis of hepatitis B virus reactivation in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients: a single-institutional experience. Bone marrow transplantation. 2016;51(4):581–586. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao YP, Jiang JL, Zou WY, Xu DR, Li J. Prophylactic antiviral therapy in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in hepatitis B virus patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(14):4284–4292. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aoki J, Kimura K, Kakihana K, Ohashi K, Sakamaki H. Efficacy and tolerability of Entecavir for hepatitis B virus infection after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Springerplus. 2014;3:450. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuji M, Ota H, Nishida A, et al. Entecavir is safe and effective as prophylaxis for reactivation of hepatitis b virus in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients with chronic or resolved viral hepatitis b infection. Blood. 2012;120(21) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liver EAFTSOT. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of hepatology. 2017;67:370–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatology international. 2016;10(1):1–98. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9675-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2016;63(1):261–283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Organization WH. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam YF, Yuen MF, Seto WK, Lai CL. Current Antiviral Therapy of Chronic Hepatitis B: Efficacy and Safety. Current hepatitis reports. 2011;10(4):235–243. doi: 10.1007/s11901-011-0109-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buti M, Gane E, Seto WK, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. The lancet Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2016;1(3):196–206. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan HL, Fung S, Seto WK, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. The lancet Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2016;1(3):185–195. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krogsgaard K, Bindslev N, Christensen E, et al. The treatment effect of alpha interferon in chronic hepatitis B is independent of pre-treatment variables. Results based on individual patient data from 10 clinical controlled trials. Journal of hepatology. 1994;21(4):646–655. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(94)80114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu C, Hsiung CA, Su IJ, et al. A revisit of prophylactic lamivudine for chemotherapy-associated hepatitis B reactivation in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2008;47(3):844–853. doi: 10.1002/hep.22106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen XQ, Peng JW, Lin GN, Li M, Xia ZJ. The effect of prophylactic lamivudine on hepatitis B virus reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma undergoing prolonged rituximab therapy. Med Oncol. 2012;29(2):1237–1241. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-9974-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liaw YF, Leung NW, Chang TT, et al. Effects of extended lamivudine therapy in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(1):172–180. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lok AS, Lai CL, Leung N, et al. Long-term safety of lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(6):1714–1722. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrillo RP, Wright T, Rakela J, et al. A multicenter United States-Canadian trial to assess lamivudine monotherapy before and after liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;33(2):424–432. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida H, Kato T, Levi DM, et al. Lamivudine monoprophylaxis for liver transplant recipients with non-replicating hepatitis B virus infection. Clinical transplantation. 2007;21(2):166–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fung J, Cheung C, Chan SC, et al. Entecavir monotherapy is effective in suppressing hepatitis B virus after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(4):1212–1219. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiff E, Lai CL, Hadziyannis S, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for wait-listed and post-liver transplantation patients with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B: final long-term results. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2007;13(3):349–360. doi: 10.1002/lt.20981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levitsky J, Doucette K. Viral hepatitis in solid organ transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2013;13(Suppl 4):147–168. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitrinos KM, Corsa A, Liu Y, et al. No detectable resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate after 6 years of therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2014;59(2):434–442. doi: 10.1002/hep.26686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hilgendorf I, Loebermann M, Borchert K, Junghanss C, Freund M, Schmitt M. Tenofovir for treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with chronic GVHD. Bone marrow tranplantation. 2011;46(9):1274–1275. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]