Abstract

A novel approach to evaluate the commercial value of green tea products is explored in this paper. The green tea Quality Index Tool (QI-Tool) is based on high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), capable of identifying and understanding the constituents that are important to create superior consumer and commercially valuable green tea beverages in the Japanese-style. This tool will allow producers to better identify a product’s potential value within the various levels of green tea retail quality structure. Via the quantification of theanine, caffeine and the catechins: epicatechin (EC), epicatechin gallate (ECG), epigallocatchin (EGC), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and gallocatechin gallate (GCG) within a green tea beverage, the QI-Tool provides categorisation of a product against the green tea market retail competitive set. This allows a better understanding of the product’s potential commercial value, as well as a comparison to other products within that market category. The QI-Tool is an alternative and promising method for objectively evaluating commercial value of green tea products using HPLC analysis.

Keywords: Green tea, Quality, Value, Catechin, Theanine, Caffeine

Introduction

It is well established that the hot water infusion of Camellia sinensis leaves, commonly known as tea, is one of the worlds most consumed beverages. The appeal is attributed to the distinct flavour profile and numerous health benefits (Cooper 2012). Infusions are prepared in various ways, being either heavily fermented for black or red teas, semi-fermented for oolong or unfermented for green teas (Lee et al. 2008).

Numerous studies have evaluated the quality characteristics of green tea (Camellia L. sinensis), predominantly focussing on the variation in time of harvesting and fermentation (Kim et al. 2016), brewing methods (Lee et al. 2008) or grade (Shimoda et al. 1995). The quality of Japanese-styled green tea is primarily accredited to its polyphenol (primarily catechins) and caffeine content, however, of particular importance to green tea varieties is an understanding of the individual constituents that are capable of altering the taste, consumer perception and ultimately the commercial value and viability of a product (Harbowy and Balentine 1997; Lee et al. 2008; Yao et al. 2006a). Hence, the phenolic concentration is said to be the key contributing factor of quality, mainly colour and flavour of the tea. These constituents include theanine, caffeine and the catechins: epicatechin (EC), epicatechin gallate (ECG), epigallocatchin (EGC), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and gallocatechin gallate (GCG), all well-known as imbuing green tea with important flavour characteristics, affecting sensory quality and economic value (Kumar et al. 2011).

Traditionally, the evaluation of tea quality has been ascribed to human sensory analysis, where skilled tea tasters’ grade samples based upon their appearance, aroma and taste. The quantification of tea quality is incredibly complex and multidimensional, so often this human sensory evaluation is fraught with inaccuracy, inconsistency and is considered highly subjective. With the ever-increasing consumption of green tea, a reliable, efficient and objective method of measuring quality becomes more and more significant. Conventional analytical techniques that measure quality associated with the flavour of green tea, have included chromatographic, spectroscopic and metabolomics methods (Pongsuwan et al. 2008; Tarachiwin et al. 2007; Yao et al. 2006b). More recently, artificial methods of evaluating tea quality have included biosensor analysis (Kumar et al. 2011), colour analysis (Liang et al. 2005) and electronic intelligent systems which mimic the sensory perception of human smell and taste (Banerjee et al. 2016; Zhi et al. 2017). These techniques can be more cost effective and quicker to perform than traditional methods; however, the breadth of their accessibility to the food industry is largely unknown and concern about the automated differentiation between samples, the comparability of colour profile and the correlation of these techniques with traditional, validated sensory quality attributes, still need to be considered.

Whilst these existing methods of quality assessment are valid and suitable options for tea manufacturers, none to date has provided correlation to the commercial value of a product, which is vital for continuous improvement of quality within industry.

In this study we use the high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method capable of quantifying targeted constituents within green tea infusions. It has the ability to objectively measure, therefore, reduce some of the potential variability within finished products, through more specific monitoring and greater process control (Nishitani and Sagesaka 2004). This can result in improved consistency, sensory appeal and overall consumer desirability for the green tea products (Ahmad et al. 2014). This method can help attain, through the careful planning and determination of realistic product specifications, green tea products which have undergone development improvements based upon measurable characteristics of the market’s current leading products (Tuwei et al. 2008).

It is anticipated that the global green tea market will continue to grow rapidly over the coming years, influenced by several factors including traditional price and income variables, demographics such as age, education, occupation and cultural background and the rise in consumer awareness of the health benefits of green tea consumption (Chang 2015). Because of this positive market trend, new tea brands and green tea products continue to be conceived in an effort to profit from the growing consumer demand. This in turn creates a highly competitive market for green tea retail products and hence an opportunity exists for an objective measure of quality. Having an understanding of the relative concentration, or ratios of green tea constituents that affect the commercial value of green tea products, would assist in the identification and/or production of high-valued green tea products.

The objective of the present study was to develop and validate an objective Quality Index Tool (QI-Tool), to measure commercial value of green tea products based upon five Quality Markers of consumer preference and market performance.

Materials and methods

Tea samples

Commercially available green tea (Camellia L. sinensis) samples were used in this study. These leaf tea samples were purchased from a boutique tea retailer in NSW, Australia as described in Table 1 and were used for analysis, without additional pulverisation or drying. All teas were of Japanese production style and of either Japanese or Australian origin, unbranded and purchased in bulk. All samples had been packaged within three months prior to purchase and had a minimum of nine months labelled, Best Before, shelf life remaining.

Table 1.

Green tea (Camellia L. sinensis) samples stratified by commercial value, according to retail price category ($AUD per kg)

| Commercial value | Product | Retail category |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Australian Sencha | < 200 |

| Green Sencha tea | ||

| Japanese Bancha | ||

| Medium | Australian organic Sencha grade 1 | 200–400 |

| Japanese Sencha Shimizu | ||

| Japanese Sencha organic | ||

| High | Japanese Gyokuro | > 400 |

| Premium ‘First Harvest’ Japanese Sencha Shimizu | ||

| Japanese finest quality Gyokuro |

There was a total of 14 eligible teas, of which nine were selected and stratified according to their retail price ($AUD per kg) and grouped into commercial value categories (low, medium or high) (Table 1). This grouping was used to compare and classify teas and representative of the available boutique Japanese-styled green tea product types.

Preparation of samples for analysis

A total of nine green tea samples were included in this study. Each of the nine samples consisted of 1 g dried weight of plant material added to 100 ml of > 90 °C deionised water spiked with HPLC internal standard (0.02 mM l-tryptophan in final solution). Each sample was then heated for 20 min in a > 90 °C shaking water bath. Immediately after heating, the samples were placed in an ice bath for an additional 30 min or until a temperature < 5 °C was achieved. The samples were cooled, filtered using a 0.45 μm nylon syringe filter (Phenomenex, Pennant Hills, Australia) and then transferred to a 5 ml brown glass HPLC vial, ready for HPLC analysis. All samples were tested in triplicate.

HPLC system and standard chromatographic conditions

The HPLC analysis was performed using a Shimadzu analytical HPLC system (Shimadzu Analytical Australia, Rydalmere, Australia), controlled via a SCL-10A VP control unit with VP 5.03 software, GT-154 degasser, FCV-10AL mixer,LC-10AT liquid chromatography pump, SIL-10AXL VP auto injector with a 100 μl sample loop and SPD-10A UV–Vis detector was used. The HPLC method was adapted from validated methods (Yoshida et al. 1999) for the separation of the different green tea constituents and for the identification of theanine in green tea (Hirun and Roach 2011; Vuong et al. 2011). This method was adapted to include the identification and measurement of theanine, caffeine, GCG, EC, ECG, EGCG and EGC. The constituents were separated using a Synergy Fusion RP reverse-phase Phenomenex column (250 × 46 mm internal diameter) and an analytical-size Fusion RP Guard column (Phenomenex Inc., Pennant Hills, Australia). The chromatographic conditions were 25 °C, achieved via a CTO-10Avp Column Oven and the level of absorbance was measured at 280 and 210 nm wavelengths using a SPD-10A Dual 1/2 UV–Vis detector. The mobile phases were degassed during production via filtration, but also during the operation of the HPLC system at a flow rate of one ml/min by a GT-154 degasser unit. The first 10 min consisted of 100% mobile phase A (12.5% (v/v) chromatographic grade > 99% Acetonitrile and 1.5% (v/v) chromatographic grade > 99% Tetrahydrofuran in phosphate buffer system), before a gradient elution over 20 min to 100% mobile phase B (25% (v/v) chromatographic grade > 99% Acetonitrile and 1.5% (v/v) chromatographic grade > 99% Tetrahydrofuran in phosphate buffer system), which was held for 10 min before a gradient return to the original conditions of 100% mobile phase A prior to the injection of the next sample to be analysed.

The quantitative analysis was completed in triplicate for each sample. The output was a calculated concentration of each constituent in the form of mg of constituent per g of dried tea.

Determination of green tea Quality Markers

The individual target constituents quantified from the HPLC analysis of each green tea sample was used to calculate five identified Quality Markers of green tea:

Total catechin:EC, EGC, EGCG, GCG and ECG, mg/g tea

Theanine:total catechin, wt:wt

Theanine:caffeine, wt:wt

EGCG:EGC, wt:wt

EGCG:GCG, wt:wt

Development of the QI-Tool

The mean value of each of the green tea Quality Markers was calculated and plotted (mean ± SE) against the corresponding commercial value (low, medium or high). The strength of this relationship was then determined using Spearman’s regression analysis and following a significant result (P < 0.05), regression analysis was used to create trend lines of best fit.

The trend line equation for each of the Quality Markers was used to calculate a Quality Value (QV) score, by substituting the mean Quality Marker value into the relevant equation (Table 2). The QV score for each Quality Marker was pooled and the mean was rounded to the nearest 0.5 of a unit.

Table 2.

Equations to determine the Quality Value (QV) score for each Quality Marker

| Quality Marker | QV equation |

|---|---|

| Total catechina | y = − 19.076x + 116.77 |

| Theanine:total catechin | y = 0.0228e1.3801x |

| Theanine:caffeine | y = 0.1852e0.6964x |

| EGCG:EGC | y = 0.4607e1.1726x |

| EGCG:GCG | y = 658.26e − 1.465x |

x = corresponding Quality Marker value

aIncludes: EC, EGC, EGCG, GCG and ECG, mg/g tea

Validation of the QV score

All five potential Quality Markers were considered important to the definition of product quality, however the strength at which each marker influences the QV score, was unknown. In order to evaluate and verify feasibility for the determination of the QV score, a hypothetical sub-study was designed to measure the comparative bias strength.

This involved calculating the QV score for each of the nine sample teas using the method described above against a theoretical null hypothesis, based upon Fisher’s Principles of Experimentation (Preece 1990). In this experiment, the theoretical null hypothesis was that the mean QV score would equal the value of 2.0, or medium commercial value, based upon equal sample sizes and equal distribution of the three categories (low = 1.0; medium = 2.0; high = 3.0). The second null hypothesis was that any bias caused by any of the five QVs; either used solely or in combination with one another, would be identified by a mean result differing from the expected value of 2.0.

The value of the difference, either positive or negative, of the calculated mean from the expected value would indicate the direction of the bias. Whilst the magnitude of the deviation of the calculated value from the expected value would indicate the strength of the potential bias. Therefore, a result that showed no bias of QV in determining the QV score would have a calculated value equal to or approaching the value of 2.0, with minimal calculated deviation from the mean value.

To scientifically test the null hypothesis, the five individual QVs for each of the nine sample teas were calculated and pooled. The results were then re-distributed to create pools of data that included all possible permutations of the five QVs: in either pools of two, three, four and finally five QVs. The mean and SD was then calculated for each pool of data to provide a QV score for that combination.

The relative strengths of the 31 mean QV calculations were analysed using Fisher’s exact test, incorporating the Monte Carlo correction available within the SPSS version 15 software suite. The Monte Carlo correction was incorporated to ensure continuity correction within the Fisher’s exact test, due to binomial distribution and the small sample size of nine benchmark teas.

The null hypothesis predicted that the calculated QV score would equal the expected value of 2.0. Therefore, a P ≤ 0.05 indicated that variation existed between the calculated mean QV score of the data pool tested and the expected outcome of 2.0. Thus, a significant value would indicate a bias result and a weaker correlation of the real QV score.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis were carried out using SPSS 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mean ± SD are presented and the significant level was established at P ≤ 0.05. The Fisher’s exact test and the calculated P values were used to test for bias in all of the combinations of QV scores from the five quality indices as described above.

Results and discussion

Quality Markers of green tea

When high value price green teas are consumed, they are often described as a complex balance of bitter astringency and sweet-salty characteristics. Closer inspection of the constituents of these green teas reveals that these perceived tastes are the result from the presence and the concentration of particular constituents. Sour-astringency is associated with the antioxidant group of catechins, whilst caffeine is associated with bitterness and theanine contributes the sweet-saltiness associated with the umami taste (Kaneko et al. 2006).

The rationale for using the total concentration of catechins as an index of green tea quality is based upon the taste sensory profile of green tea and the sensory profile of catechins. Catechins are astringent constituents comprising 10–15% of the Camellia L. sinensis leaf and 20–40% of the dry mass of the tea infusion (Chen et al. 2001). Therefore, considering their abundance and definable taste, the total concentration of catechins can affect the quality of the green tea infusion overall and therefore total catechin concentration; playing a role within consumer acceptance, ultimately affects the retail market value of the final product.

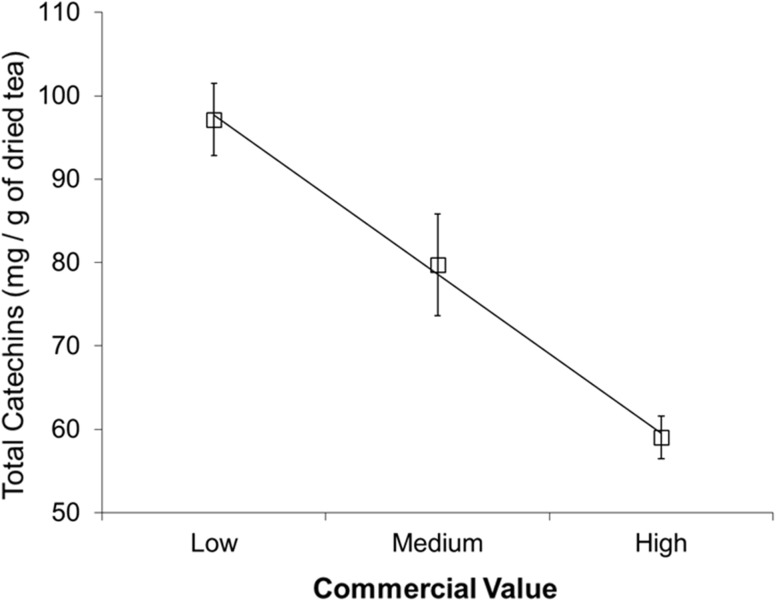

Figure 1 shows a negative linear relationship between the concentration of total catechins and commercial value (R = 0.998, P < 0.001). This correlation suggests that teas with greater than 100 mg of total catechins per g of dried tea will have a low commercial value (~ $200 AUD or less per kg), indicating poorer quality. In contrast, teas with a total catechin content of less than 60 mg per g of dried tea had a higher value (~ $400 AUD or less per kg) indicating a more valuable retail product. This can be attributed to the astringent flavour of catechins, suggesting that tea products with components high in astringency are less favourable, which supports the conclusions of others (Balentine et al. 1997; Lee and Chambers 2007).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between total catechin (mg/g of dried tea) and the commercial value of green tea

The theanine to total catechin ratio is also thought to affect green tea quality, as it is the ratio between the naturally occurring sweet-saltiness characteristic of theanine and the astringency of the catechins (Lee and Chambers 2007). A high ratio indicates a product with a greater concentration of theanine and less total catechins.

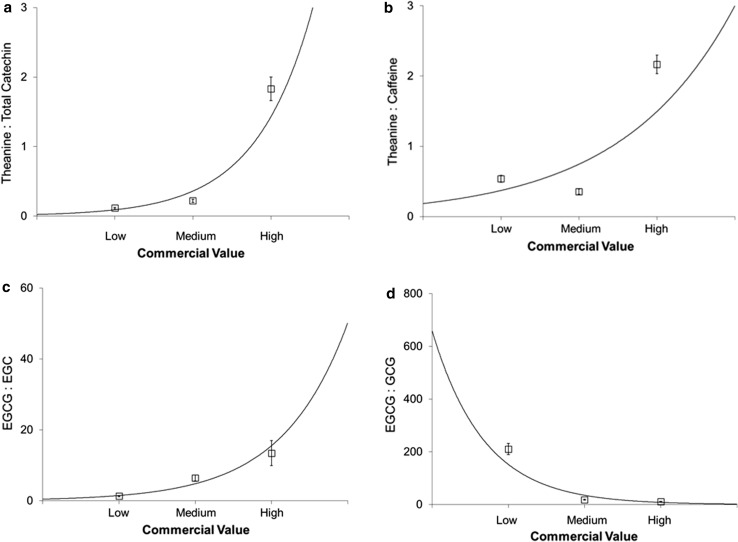

In this study (Fig. 2a), a significant relationship exists between commercial value and the theanine:total catechin ratio (R = 0.955, P < 0.001) with 91% of the variation in quality attributed to the theanine:total catechin ratio. Furthermore, the exponential nature of this relationship shows that the effect is more pronounced in teas with a retail value greater than $200 AUD per kg or medium commercial value, as compared to those less than $200 AUD per kg. This measure is predictive of quality, where a balance between the umami of the theanine against the astringency of the catechins is highly sort after (Harbowy and Balentine 1997; Kaneko et al. 2006; Narukawa et al. 2008). The green tea flavour profile; favouring umami characteristics rather than astringency, was found in green tea products of higher retail price, suggesting that teas of high commercial value may have a flavour balance favouring sweetness rather than bitter-sourness, which is supported by the literature (Nose et al. 1971). A product that is greater in proportion of theanine to caffeine is more favourable and of greater commercial value, due to the balance between the sweet-saltiness of theanine and the sharp bitterness of caffeine (Lee and Chambers 2007; Liang et al. 2015; Narukawa et al. 2008).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between the ratio of a theanine:total catechin, b theanine:caffeine, c EGCG:EGC, d EGCG:GCG and the commercial value of green tea

We show a direct exponential relationship between the theanine:caffeine ratio and commercial value (Fig. 2b), albeit this accounted for only 54% of the variance (R = 0.736, P < 0.001). Unlike the strong correlation between quality and the catechins and astringency, the correlation between quality and caffeine and bitterness was more variable. This may be a result from a greater acceptability of caffeine by consumers, or influenced by the strong association between the consumption patterns for tea and the consumption of coffee, which is a main source of caffeine in western markets (Oba et al. 2010). Because caffeine adds bitterness to green tea, the variability in the caffeine could also be due to variability in the preference for bitterness. Importantly, given that the Australian population has a greater per capita coffee:tea consumption ratio than the Japanese (Sui et al. 2016), it is conceivable that the price and quality of the sample green teas may have been biased towards Australian green tea drinkers, who value the bitter characteristic of caffeine more than do other nationalities, such as the Japanese.

Another reason for the lower correlation strength between the theanine:caffeine ratio and the green tea product quality can be drawn from the research of Furuya et al. (1990), which shows that the caffeine and theanine concentrations are variable within the cell structures of the leaves and stems of shaded plants. The literature shows that in shaded plants, caffeine tends to concentrate in the stems of the plant, resulting in poor caffeine, theanine rich and high umami flavoured teas when they are produced from predominately leaf material. The stems of these teas, although of good quality, are often considered waste and are blended with some lower quality leaf products to increase their volume and to produce some of the products sold in the medium-quality range. This creates a product with the pleasant flavour of the high-quality teas, but with a higher proportion of caffeine, due to the included stems.

The relationship between the concentration of EGCG and that of EGC is not strictly based upon its effect on flavour, but also dependent on the harvest time of the green tea product. This can be used as a predictor of quality, where the time of harvest; early or late, is likely to correlate with commercial value, high or low respectively. The extent to which a product may have been adulterated or blended by the producer, compared to teas produced solely from ‘first’ harvest material, can also be determined.

The relationship between the commercial value and the ratio of EGCG:EGC is exponential with a very strong correlation (R = 0.977, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2c). Over 95% of the variation in the market value can be attributed to the variation within the ratio of EGCG:EGC. As the ratio of EGCG:EGC increases, so too does the commercial value of the tea. EGCG and GCG are stereoisomers of one another. EGCG occurs naturally and in abundance, while its epimer, GCG, is not naturally present in freshly harvest material but usually detected in green tea infusions, implying that the epimerisation of EGCG to GCG occurs during the processing, drying or storage of the green tea (Ikeda et al. 2003).

The relationship between the ratio of EGCG:GCG to market value is illustrated in Fig. 2d (R = 0.933, P < 0.001) showing that 87% of the variation can be attributed to variance in the ratio of EGCG:GCG. Therefore, the ratio of EGCG:GCG is an indicator of commercial value, as it provides an indication of the level of heat processing to which a product has been subjected. If the manufacture follows strict and controlled processing and post-harvest storage guidelines, the production of GCG can be controlled and its presence can actually improve the quality of the tea by improving its shelf-life stability and the antioxidant potential of the final green tea product (Wang and Helliwell 2000). Therefore, although not a natural constituent of green tea, having some GCG in the dried manufactured green tea actually enhances the quality of the product.

The argument that the presence of GCG coincides with higher commercial value of a green tea product, was supported by this study. The data showed that teas with a medium or high market value had a lower ratio of EGCG to GCG compared to teas with a low value. It was also found that the optimal balance is an equal ratio of EGCG to GCG.

Certainly, the low-quality teas contained very large amounts of EGCG, with comparably little GCG. Due to their low concentrations of GCG, these products will be less stable throughout their shelf lives and, as such, retailers cannot charge a premium price due to the high risk of the product going stale. Therefore, the common retail practice is to sell these low stability products for less to ensure a quick sale and rapid turnover. Knowing this, green tea producers can take measures to ensure an appropriate EGCG:GCG ratio by adjusting their processing techniques. Doing so, will increase the stability and thus the marketable quality of their product and maximise the sale price.

Characterisation of the QV score

The findings discussed above support the hypothesis that relationships exist between the bioactive constituents of green tea and the commercial value of green tea products. Furthermore, it has been confirmed that the measurement of these relationships is useful for gauging the product quality of a green tea and categorising it, so that it can be directly compared to the products with which it will compete.

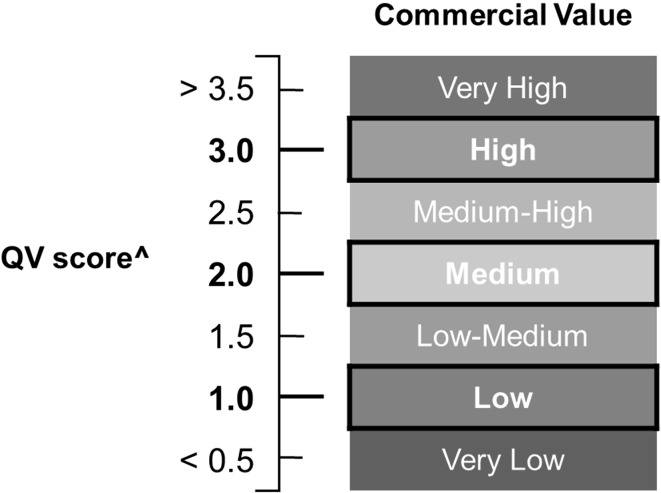

Taking the average of the calculated QV scores, enables identification of the green tea product’s potential commercial value (Fig. 3). Due to the rounding of the score to half units, as well as calculations based upon continuous values for the quantified targeted constituents within the green tea infusion, it was also possible to calculate half units of QV scores. Therefore, additional hypothetical categories were introduced (very low, low–medium, medium–high and very high). Although not representative of any particular sector of the retail market, these values sit below, above and between the three defined commercial value groups (low medium and high); they represent those products that do not entirely satisfy the quality specifications of the three true commercial value categories.

Fig. 3.

The QI-Tool: categorisation of Quality Value (QV) score to estimated commercial value (high ~ $500AUD per kg; medium ~ $300AUD per kg; low ~ $150AUD per kg). Bolded values represent defined scores, where others are hypothetical. ^ the average QV score, rounded to the nearest half unit

These additional categories could also be useful for the Australian and other emerging green tea industries, as they will allow for a greater level of detail in the direct comparison between particular tea products and therefore, will better inform producers in their continuous improvement efforts for the production of better quality and commercially valuable green tea products. Such ongoing comparisons could be used to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of products in more detail. The correlation between QV and commercial value is distinguished as the QI-Tool.

Validation of the QI-Tool

While the five Quality Markers measure different characteristics of green tea retail quality, it was important that the combined overall QV score were not biased toward any particular aspect of the Quality Markers. Table 3 shows the measure of variability between the mean QV score of the five quality indices, compared to the expected mean value of 2.0 from the theoretical null hypothesis.

Table 3.

Determination of biasa to Quality Value (QV) score, by combinations of Quality Markers

| Expected QV scoreb | Calculated QV scoreb | P valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total catechin (A) | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.11 |

| Theanine:total catechin (B) | 2.0 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.11 |

| Theanine:caffeine ratio (C) | 2.0 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.66 |

| EGCG:EGC (D) | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.14 |

| EGCG:GCG (E) | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.14 |

| Mean (ABCD) | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.11 |

| Mean (ABDE) | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.14 |

| Mean (ACDE) | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.11 |

| Mean (BCDE) | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.11 |

| Mean (ABCDE) | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.11 |

aFisher’s exact test with Monte Carlo correction of calculated score compared to expected values

bMean ± SD

cTest of significance (P ≤ 0.05) between the expected and calculated mean value

The results showed that the calculated values all approached the expected value of 2.0, with the strongest calculated value coming from the pool of data incorporating all five Quality Markers. The measure of variability calculated for each combination, compared to the expected value was not significant, thus, the combination/s of the Quality Markers to calculate the QV score proved to have no bias and substantiates the use of the QI-Tool as a reliable objective measure of green tea commercial value.

Interestingly the result of this experimentation showed that whilst the QV score that was closest to the expected result (i.e. 2.0) was achieved from using a combination of the five Quality Markers, using any individual or combination of Quality Markers was also acceptable as an estimate of commercial value of the tea infusion.

Advantages of the QI-Tool

The QI-Tool is a novel approach for measuring commercial value of green tea, as it removes the subjectivity of sensory attributes, specificity of specialist-trained panels and the cost and difficulty of obtaining trained panels in emerging and remote product areas. Findings from this study could also serve as a valuable measurement for evaluating interventions or changes to the growing conditions, manufacturing or processing methods that might improve or impair quality and hence influence the retail value of a product. For example, the tool could assist producers to achieve continual market quality and ensure continuous supply of quality products free from the variations caused by season, harvest timing or growing locations.

Based on the reproducibility and reliability of the QI-Tool as an objective measure, it could be valuable within industry and manufacturing, quality control and evaluation and research and development of green tea products. Given the QI-Tool is the only measure to provide categorisation of commercial value, it could potentially be applied in combination with other quality assessments of green tea (i.e. trained organoleptic analysis) to provide a more robust evaluation of the product. Additionally, constituent measures from other types of analytic models such as mass spectrometry (MS), near infrared spectroscopy (NIR) or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), could be substituted for HPLC analysis.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to present an objective quality measure for the categorisation of green tea commercial value. Based upon five Quality Markers, known to influence the sensory appeal, consumer preference and retail value of green tea products, the proposed QI-Tool as a measure of green tea quality can be related directly to the commercial value of the product. In conclusion, the QI-Tool is an asset for manufacturers and the food industry to independently evaluate green tea products to make regional, national and international comparisons. This has potential value for quality monitoring during the harvest, manufacture and storage of green tea.

References

- Ahmad RS, Butt MS, Huma N, Sultan MT, Arshad MU, Mushtaq Z, Saeed F. Quantitative and qualitative portrait of green tea catechins (GTC) through HPLC. Int J Food Prop. 2014;17:1626–1636. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2012.723232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balentine DA, Wiseman SA, Bouwens LCM. The chemistry of tea flavonoids. Crit Rev Food Sci. 1997;37:693–704. doi: 10.1080/10408399709527797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R, Tudu B, Bandyopadhyay R, Bhattacharyya N. A review on combined odor and taste sensor systems. J Food Eng. 2016;190:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K. World tea production and trade: current and future development. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Zhu QY, Tsang D, Huang Y. Degradation of green tea catechins in tea drinks. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:477–482. doi: 10.1021/jf000877h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R. Green tea and theanine: health benefits. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2012;63:90–97. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2011.629180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya T, Orihara Y, Tsuda Y. Caffeine and theanine from cultured cells of Camellia sinensis. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:2539–2543. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(90)85184-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harbowy ME, Balentine DA. Tea chemistry. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1997;16:415–480. doi: 10.1080/07352689709701956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirun S, Roach PD. An improved solvent extraction method for the analysis of catechins and caffeine in green tea. J Food Nutr Res. 2011;50:160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda I, Kobayashi M, Hamada T, Tsuda K, Goto H, Imaizumi K, Nozawa A, Sugimoto A, Kakuda T. Heat-epimerized tea catechins rich in gallocatechin gallate and catechin gallate are more effective to inhibit cholesterol absorption than tea catechins rich in epigallocatechin gallate and epicatechin gallate. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7303–7307. doi: 10.1021/jf034728l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Kumazawa K, Masuda H, Henze A, Hofmann T. Molecular and sensory studies on the umami taste of Japanese green tea. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:2688–2694. doi: 10.1021/jf0525232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Lee KG, Kim MK. Volatile and non-volatile compounds in green tea affected in harvesting time and their correlation to consumer preference. J Food Sci Technol Mysore. 2016;53:3735–3743. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2349-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar PVS, Basheer S, Ravi R, Thakur MS. Comparative assessment of tea quality by various analytical and sensory methods with emphasis on tea polyphenols. J Food Sci Technol Mysore. 2011;48:440–446. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0178-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Chambers DH. A lexicon for flavor descriptive analysis of green tea. J Sens Stud. 2007;22:256–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.2007.00105.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Chung SJ, Lee OH, Lee HS, Kim YK, Kim KO. Development of sample preparation, presentation procedure and sensory descriptive analysis of green tea. J Sens Stud. 2008;23:450–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.2008.00165.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang YR, Lu JL, Zhang LY, Wu S, Wu Y. Estimation of tea quality by infusion colour difference analysis. J Sci Food Agric. 2005;85:286–292. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang YR, Liu C, Xiang LP, Zheng XQ. Health benefits of theanine in green tea: a review. Trop J Pharm Res. 2015;14:1943–1949. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v14i10.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narukawa M, Morita K, Hayashi Y. l-theanine elicits an umami taste with inosine 5′-monophosphate. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:3015–3017. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani E, Sagesaka YM. Simultaneous determination of catechins, caffeine and other phenolic compounds in tea using new HPLC method. J Food Compos Anal. 2004;17:675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2003.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nose M, Nakatani Y, Yamanishi T. Studies on flavor of green tea. Agric Biol Chem. 1971;35:261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Oba S, Nagata C, Nakamura K, Fujii K, Kawachi T, Takatsuka N, Shimizu H. Consumption of coffee, green tea, oolong tea, black tea, chocolate snacks and the caffeine content in relation to risk of diabetes in Japanese men and women. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:453–459. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongsuwan W, Bamba T, Harada K, Yonetani T, Kobayashi A, Fukusaki E. High-throughput technique for comprehensive analysis of Japanese green tea quality assessment using ultra-performance liquid chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC/TOF MS) J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:10705–10708. doi: 10.1021/jf8018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preece DA. R.A Fisher and experimental design: a review. Biometrics. 1990;46:925–935. doi: 10.2307/2532438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda M, Shigematsu H, Shiratsuchi H, Osajima Y. Comparison of volatile compounds among different grades of green tea and their relations to odor attributes. J Agric Food Chem. 1995;43:1621–1625. doi: 10.1021/jf00054a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sui Z, Zheng M, Zhang M, Rangan A. Water and beverage consumption: analysis of the Australian 2011–2012 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Nutrients. 2016;8:E678. doi: 10.3390/nu8110678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarachiwin L, Ute K, Kobayashi A, Fukusakii E. H-1 NMR based metabolic profiling in the evaluation of Japanese green tea quality. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:9330–9336. doi: 10.1021/jf071956x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuwei G, Kaptich FKK, Langat MC, Chomboi KC, Corley RHV. Effects of grafting on tea 1. Growth, yield and quality. Exp Agric. 2008;44:521–535. doi: 10.1017/S0014479708006765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong QV, Golding JB, Stathopoulos CE, Nguyen MH, Roach PD. Optimizing conditions for the extraction of catechins from green tea using hot water. J Sep Sci. 2011;34:3099–3106. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HF, Helliwell K. Epimerisation of catechins in green tea infusions. Food Chem. 2000;70:337–344. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00099-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao LH, Jiang YM, Caffin N, D’Arcy B, Datta N, Liu X, Singanusong R, Xu Y. Phenolic compounds in tea from Australian supermarkets. Food Chem. 2006;96:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao LH, Liu X, Jiang YM, Caffin N, D’Arcy B, Singanusong R, Datta N, Xu Y. Compositional analysis of teas from Australian supermarkets. Food Chem. 2006;94:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Kiso M, Goto T. Efficiency of the extraction of catechins from green tea. Food Chem. 1999;67:429–433. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00148-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi RC, Zhao L, Zhang DZ. A framework for the multi-level fusion of electronic nose and electronic tongue for tea quality assessment. Sensors Basel. 2017;17(5):1007. doi: 10.3390/s17051007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]