Abstract

Clostridia are widespread and some of them are serious human pathogens. Identification of Clostridium spp. is important for managing microbiological risks in the food industry. Samples derived from sheep and cattle carcasses from a slaughterhouse in Iran were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS using direct transfer and extended direct transfer sample preparation methods and 16S rDNA sequencing. MALDI-TOF MS could identify ten species in 224 out of 240 Clostridium isolates. In comparison to the 16S rDNA sequencing, correct identification rate of the Clostridium spp. at the species level by MALDI-TOF MS technique was 93.3%. 16 isolates were not identified by MALDI-TOF MS but 16s rDNA sequencing identified them as C. estertheticum, C. frigidicarnis, and C. gasigenes species. The most frequently identified Clostridium species were: C. sporogenes (13%), C. cadaveris (12.5%), C. cochlearium (12%) and C. perfringens (10%). Extended direct transfer method [2.26 ± 0.18 log (score)] in comparison to direct transfer method [2.15 ± 0.23 log (score)] improved Clostridium spp. identification. Using a cut-off score of 1.7 was sufficient for accurate identification of Clostridium species. MALDI-TOF MS identification scores for Clostridium spp. decreased with longer incubation time. Clostridium species predominantly were isolated from carcasses after skinning and evisceration steps in the slaughterhouse. MALDI-TOF MS could be an accurate way to identify Clostridium species. Moreover, continuous improvement of the database and MALDI-TOF MS instrument enhance its performance in food control laboratories.

Keywords: Clostridium spp., Slaughterhouse, 16S rDNA, MALDI-TOF MS

Introduction

Clostridia are anaerobic spore-forming bacteria which are found in the environment and also in the intestinal tract of humans and animals (Wiegel et al. 2006). Some Clostridium species such as C. perfringens, C. botulinum, C. tetani, and C. difficile cause infections in humans and produce lethal toxins (Doulgeraki et al. 2012; Lee and Pascall 2012; Wiegel et al. 2006). The most important Clostridium species involved in food spoilage are Clostridium sporogenes, Clostridium butyricum, Clostridium putrefaciens, Clostridium tyrobutyricum, and Clostridium pasteurianum (Naim et al. 2008). Clostridium species contaminate the abattoirs mainly through attached soil particles to the hide and feces of animals (Silva et al. 2012). Bacterial contamination on the hide could transfer to carcasses during the slaughtering process (Narvaez-Bravo et al. 2013). The meat industry is concerned about Clostridium species on meat surfaces and equipment in slaughterhouses. Meat and meat products are the favored medium for growth and toxin production of Clostridium species (Húngaro et al. 2016). Although heat processing and sanitizing treatment in food processing facilities destroy the vegetative cells of Clostridium species, their spores can survive and proliferate in prepared food stored at room temperature (Lee and Pascall 2012). Temperature abuse during cooling, distribution, storage and reheating of cooked products is an important factor negatively impacting shelf-life and quality of meat products resulting in spore germination and rapid growth of bacteria such as Clostridium species. Subsequently, this leads to spoilage of meat and thus increases the risk of food poisoning (Redondo-Solano et al. 2013). Therefore, fast and reliable detection and identification of Clostridium spp. are crucial to adequately manage related microbiological risks. Phenotypic identification is limited to a few specific laboratory characteristics and the restricted species in databases of commercial kits (Chean et al. 2014). The correct and reproducible identification of Clostridium species by use of biochemistry, fermentation profiles, and gas–liquid chromatography are not easy to manage for inexperienced users and restricted to reference laboratories (Chean et al. 2014; Grosse-Herrenthey et al. 2008). In addition, 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequencing has been widely used to identify and differentiate Clostridium species. However, for the routine diagnostic application, it’s not suitable because it’s time consuming, costly and needs sequence interpretation (Chean et al. 2014).

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has been developed as a routine microbiological diagnosis tool with dependable results (Gutiérrez et al. 2017). This method is based on generating complex fingerprint spectra of biomarker molecules by measuring the mass/charge (m/z) of peptides and proteins, which represent high-abundant proteins with housekeeping functions, such as ribosomal proteins (Alispahic et al. 2011). Accordingly, the mass spectra patterns are stable and can be used for finding similarities and phylogenetic relationships of the microorganisms (Angeletti2017).

MALDI-TOF MS is a user friendly, fast and inexpensive identification method that makes it possible to identify a wide range of microorganisms in routine clinical microbiology laboratories (Grosse-Herrenthey et al. 2008; Veloo et al. 2011a, b, c; Agustini et al. 2014; Barba et al. 2014; Hsu and Burnham 2014; Randall et al. 2015; Seng et al. 2009).

The objective of this study was to apply MALDI-TOF MS to identify isolates of Clostridium spp. derived from sheep and cattle carcasses at different steps of the slaughtering process in Iran. Two sample preparation methods were applied in parallel for each isolate: direct transfer and extended direct transfer. The second objective was to verify MALDI-TOF MS results with 16S rDNA gene sequencing. Finally, the third objective was to evaluate the reproducibility using the different state of bacteria after cultivation.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and bacteriological analysis

60 samples were taken from one small slaughterhouse of sheep and cattle as a representative of slaughterhouses located in the province of Tehran, Iran, with respect to slaughtering capacity (approximately 25–30 sheep and 15–20 cattle per hour), utensils, equipment, and pre-slaughter holding pen conditions. The animals were received from traditional livestock farms. Slaughtering procedures were without physical division between clean and unclean areas, but cutting and deboning for retail were performed in a separate room. In the sheep slaughter line, bleeding and skinning were done on the floor while in the cattle slaughter line, all slaughtering processes were performed on a production line and vertical rail dressing and automatic hide pullers were used.

Sterile gauzes were moistened with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Merck, Germany) and used for swab sampling. Five carcasses were selected in each slaughter line by simple random sampling methods. Swab samples were taken from carcasses after skinning, evisceration, trimming, and final washing at four different points: neck, brisket, flank, and rump in cattle, and flank, thorax lateral, brisket, and breast in sheep according to Salmela et al. (2013). Rectal swab samples were taken from carcasses immediately after evisceration. Swab samples were also taken from meat after cutting and deboning of selected carcasses (Salmela et al. 2013). After swabbing, the gauze was immediately transferred to 20 ml of Thioglycollate broth (Oxoid, UK). Isolation of psychrotrophic Clostridium was done according to Silva et al. (2012). For isolation of spores of mesophilic Clostridium, Thioglycollate broth tubes containing swab samples were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for a period of 10 days. The tubes were heated to 80 °C for ten minutes for inactivation of vegetative cells. The pelleted spores were washed with 100 ml sterile distilled water and then centrifuged. The washing process was done according to Brunt et al. (2015) and repeated three times (Brunt et al. 2015). Finally, sediments were plated on Columbia agar supplemented with 5% (v/v) blood sheep (BioMerieux, France). Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C using self-contained gas generating system AnaeroGen™ (Oxoid, UK) (Grosse-Herrenthey et al. 2008; Silva et al. 2012). Primary identification of pure colonies were done by their microscopic and colonial appearances, gram staining test and presence or absence of ß-hemolysis according to the British standards for microbiology investigations, identification of Clostridium species from Public Health England. Probable Clostridium bacteria were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS and 16S rDNA sequence analysis.

Identification with MALDI-TOF MS

For sample preparation direct transfer (DT) and extended direct transfer (EDT) methods were used in parallel.

In the DT method, one single colony was spread onto a MALDI target plate (MSP 96 target polished steel) with a toothpick. Each spot was overlaid with 1 µl matrix (3 mg/mL solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) in 50% (v/v) acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich), and 2.5% [v/v] trifluoroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and allowed to dry prior to analysis at room temperature according to Chean et al. (2014).

In the EDT method, one single colony was similarly smeared directly on the MALDI-TOF MS target plate and overlaid with 1 µl of formic acid (70%) (Sigma-Aldrich) and dried off before adding the matrix solution (Chean et al. 2014).

Prior to sample measurement, the MicroFlex LT mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) was calibrated using IVD BTS bacterial test standard (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) containing E. coli DH5α ribosomal proteins and two additional proteins (Doern 2013). The spectra were analyzed using Bruker Biotyper 3.3 software and Biotyper database version V3.3.1.0- 4613.

The MALDI Biotyper output is a log (score) in the range 0–3.0, computed by comparison of the peak list for an unknown isolate with the reference spectra in the database. A BioTyper log (score) ≥ 2.3 indicates highly probable identification at the species level. A log (score) between 2.0 and 2.3 indicates highly probable identification at the genus level and probable identification at the species level. A log (score) between 1.7 and 2.0 indicates probable genus identification, while a log (score) < 1.700 means no reliable identification.

To test if identification was possible after anaerobic incubation of bacteria for 1, 3 and 5 days, bacterial colonies were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS analysis using the DT and EDT sample preparation methods in parallel. Analysis were replicated three times for each isolate.

16S rDNA sequence analysis

A-purified single colony was transferred to TE buffer for molecular analysis. After DNA extraction using Qiagen Stool kit (Qiagen, Germany), fragments of the 16S rDNA were amplified using the primer set 341f-GC 5′-CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC AG-3′ and 518r 5′-ATT ACC GCG GCT GCT GG-3′in a concentration of 0.5 pM per reaction volume with a ready-to-use GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega, USA) according to Remely et al. (2013). After purification using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germany) samples were sent for sequencing to LGC Genomics GmbH (Germany). Nucleotide sequences were analyzed with RDP 10.32 (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/seqmatch/seqmatch_intro.jsp).

Statistics

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to evaluate the distribution of MALDI-TOF MS results. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the means of log scores of MALDI-TOF MS for Clostridium identification obtained by two different sample preparation methods. The effect of incubation time on the identification of species was analyzed by the Friedman test. For all comparisons, p values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical tests were conducted using SPSS 10.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

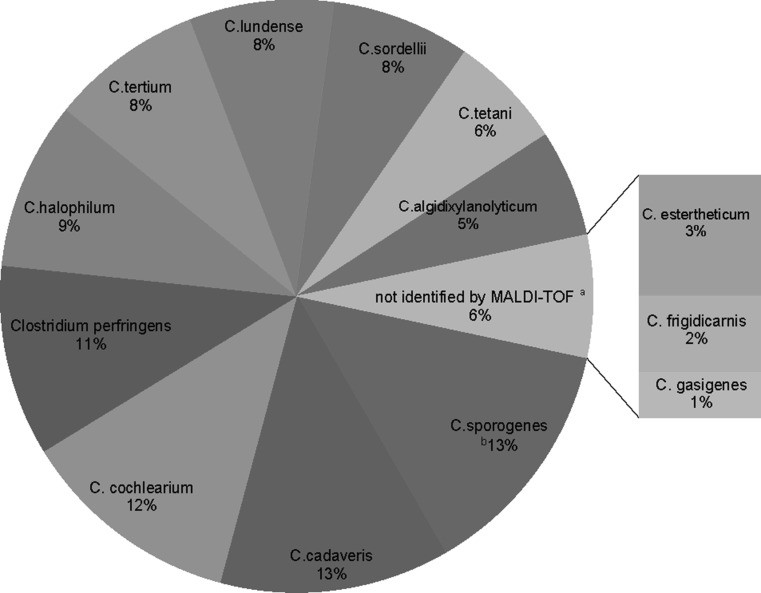

240 Clostridium species were isolated from 60 samples. All 240 Clostridium isolates were identified by 16S rDNA sequencing and assigned to 13 different Clostridium species. MALDI-TOF MS identified ten different Clostridium species in 224 isolates: C. sporogenes (n = 32), C. cadaveris (n = 30), C. cochlearium (n = 29), C. perfringens (n = 25), C. halophilum (n = 22), C. tertium (n = 20), C.lundense (n = 19), C. sordellii (n = 18), C.tetani (n = 15), and C. algidixylanolyticum (n = 14). For 16 isolates, the log score values were lower than 1.7 hence no identification was possible by MALDI-TOF MS. These strains were identified via 16S rDNA as C. estertheticum (n = 8), C. frigidicarnis (n = 5), and C. gasigenes (n = 3) species (Fig. 1). The correlation between 16S rDNA sequencing and MALDI-TOF MS results was 93.3%.

Fig. 1.

Overview of Bruker MALDI-TOF MS identification of Clostridium isolates at the species level. MALDI-TOF MS identified 94% isolates while 6% of isolates were not identified by MALDI-TOF MS. These isolates were identified via 16S rDNA as C. estertheticum (n = 8), C. frigidicarnis (n = 5), and C. gasigenes (n = 3) species

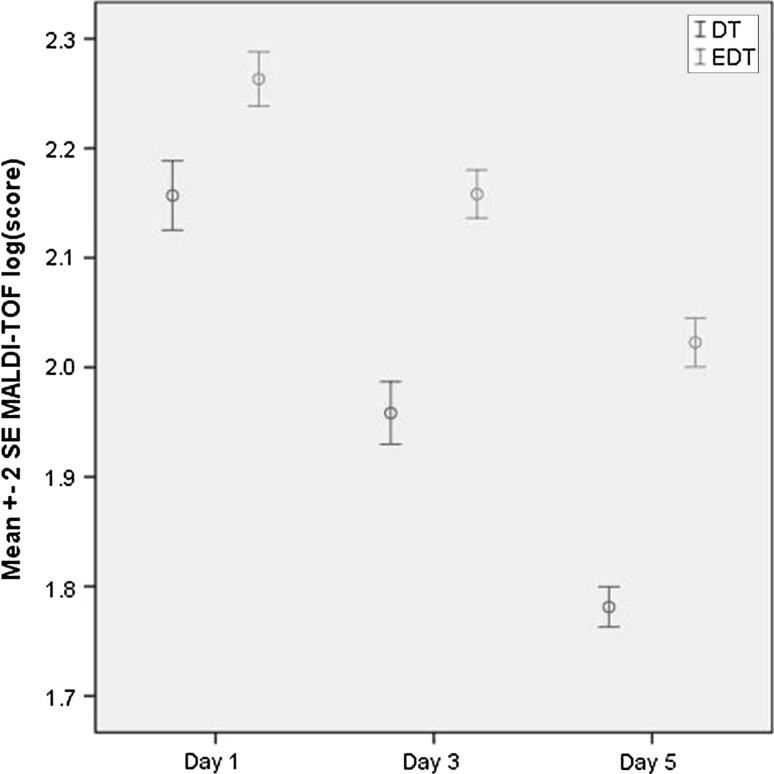

The EDT method provides better quality mass spectra and higher identification log score values compared to the DT method (p < 0.05).The EDT method had an average log score of 2.26 ± 0.18 in comparison to an average log score of 2.15 ± 0.23 for the DT method after 1-day anaerobic incubation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparing direct transfer and extended direct transfer sample preparation methods for identification of Clostridium species by MALDI-TOF MS at different days of anaerobic incubation (1, 3, and 5). Each isolate was tested three times for each method of sample preparation at each day

Highly probable species identification was obtained for 101/224 (45%) and 125/224 (56%), secure genus identification and probable species identification for 47/224 (21%) and 77/224 (34%), and probable genus identification for 76/224 (34%) and 22/224 (10%) isolates by the DT and the EDT methods respectively after 1 day anaerobic incubation.

The averages of MALDI-TOF MS log scores for Clostridium spp. identification by the EDT method on day three and day five were 2.17 ± 0.16 and 2.02 ± 0.17, in comparison to 1.96 ± 0.21 and 1.78 ± 0.14 by the DT method respectively. However, the isolates with a log score value of ≥ 1.7 were correctly identified at the species level regardless of sample preparation method and incubation time.

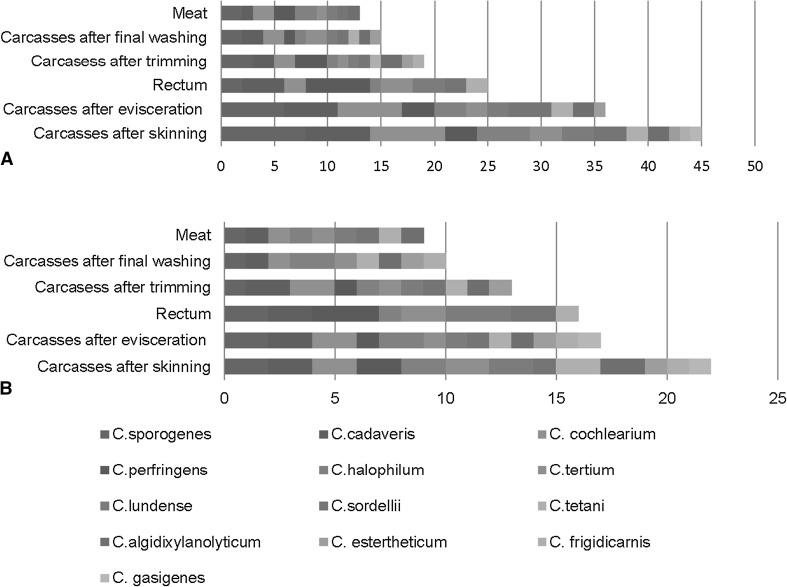

Clostridium species were isolated mainly from carcasses after skinning and evisceration steps and were isolated also from carcasses after final washing and from meat in the slaughterhouse (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Results of identification of the Clostridium species according to sampling site a sheep slaughter line, b cattle slaughter line

Discussion

In this study, we compared the identification of Clostridium spp. isolated from sheep and cattle carcasses at different stages of slaughter in an abattoir using MALDI-TOF MS against 16S rDNA sequencing. 16S rDNA sequencing is a reliable method for accurate identification of anaerobic bacteria, including Clostridium species, but this technique remains difficult to implement in routine microbiology laboratories (Chean et al. 2014; AlMogbel 2016). The MALDI-TOF MS method supplements the phenotypic methods for fast, cost-effective, robust, and reliable identification in the first step of characterization of the cultivable microbial community (AlMogbel 2016; Nacef et al. 2016). Accuracy and reliability of MALDI-TOF MS identification highly depend on the database which is used to identify microorganisms such as the existence of the mass spectra of the species in the database (Doern 2013; Veloo et al. 2011a, b, c). Reference data should include a spectrum of many individual species and large numbers of reference spectra for each species because not every single spectrum shows all the species’ biodiversity (Chean et al. 2014). Alternatively, it is possible to have acceptable identification outcome for species with a low number of spectra in the database when the organisms produce the same mass spectrometry patterns as those in the database (Chean et al. 2014).

In our study, MALDI-TOF MS could not identify some of Clostridium species such as C. estertheticum whose spectra were not in the database. However, identification of those bacteria having a low number of spectra in the database, for example, C. algidixylanolyticum was possible. C. botulinum was not in the IVD MALDI Biotyper Database. Some strains of C. botulinum group I probably are neurotoxigenic strains of Clostridium sporogenes (Bano et al. 2017). Obviously also 16S rDNA gene sequencing cannot differentiate between C. sporogenes and C. botulinum. Therefore additional tests for neurotoxin or the presence of neurotoxin genes are needed. Grosse-Herrenthey et al. (2008) reported MALDI-TOF MS could differentiate between some species which are difficult to differentiate by 16S rDNA due to high sequence similarities such as C. chauvoei and C. septicum.

In this study thirteen Clostridium species were identified in 240 Clostridium isolates derived from 60 samples by 16S rDNA sequencing. MALDI-TOF MS identified 224 of isolates belonging to ten species but could not identify 16 isolates, including three species whose spectra were not in the database. Likewise, in the study conducted by AlMogbel (2016), MALDI-TOF-MS identified 88.8% of the Clostridium spp. isolates at the species level. Similar results for non-difficile Clostridium spp. and excellent identification of C. difficile were obtained in a study conducted by Kim et al. (2016) who recommended using MALDI-TOF MS in routine microbiology laboratories in order to have successful and rapid identification of Clostridium species. Also, Grosse-Herrenthey et al. (2008) suggested MALDI-TOF MS as a powerful tool for dependable identification of Clostridium species. Veloo et al. (2011a, b, c) compared the performance of two MALDI-TOF MS systems, Bruker MS and Shimadzu MS, with 16S rDNA gene sequencing as the reference standard. They concluded that the composition and quality of the database are extremely important for an accurate identification. Further, the databases of both systems need to be optimized for routine identification of anaerobic bacteria.

In this study, the number of spectra and the number of Clostridium species of Biotyper database version V3.3.1.0-4613 were 169 and 81, respectively. The ratio of the number of reference spectra to the number of species in the database was 2.07 for Clostridium species.

Correct identification using the Bruker’s recommended cut-off score (a Biotyper score of > 2.0 for—species-level identification) was obtained for 148/224 (65%) and 202/224 (89%) of the analyzed isolates with DT and EDT preparation methods, respectively. Using a cut-off value of 1.7 allowed accurate identification of Clostridium spp. derived from slaughterhouse regardless of sample preparation methods and incubation time. Chean et al. (2014), Fournier et al. (2012), and Hsu and Burnham (2014) have reported the similar cut-off score for correct identification of anaerobic bacteria including Clostridium spp.

The results of this study on the comparison of the two different sample preparation methods, DT and EDT, suggest that using the EDT sample preparation method improves the quality of the mass spectra and, as a result, improves identification at the species level, which is also supported by Randall et al. (2015) findings. Hsu and Burnham (2014) reported that the EDT method has a better identification rate compared to the DT method even when the isolates undergo multiple sub-culturing and incubation in undesirable conditions. The EDT method reduces the background signal that could affect the recognition of bacterial peaks, especially in Gram-positive bacteria due to their cell wall structure (Chean et al. 2014; Randall et al. 2015).

The value of MALDI-TOF MS for the identification of Clostridium spp. derived from slaughterhouse significantly decreased during longer incubation time. On the first day of incubation, the MALDI-TOF MS identification scores of the colonies were higher compared to day three and five. These findings coincide with several studies which found that the length of the incubation time affects protein expression and mass spectra (Chean et al. 2014; TeKippe et al. 2013). In contrast, Veloo et al. (2014) reported that incubation time has no influence on the quality of anaerobic Gram-positive bacteria spectra. The authors have suggested performing MALDI-TOF MS when a sufficient growth is attained which could be after 24 h of incubation. However, spores have undesirable effects on accurate identification by showing slight deviations in fingerprint patterns. This is because spores have high amounts of proteins to survive in suboptimal conditions (Grosse-Herrenthey et al. 2008).

We did not investigate how culture media and time of exposure to oxygen impact mass spectrometry results. However, previous studies have shown that culturing the bacteria on different media and time of exposure to oxygen have no influence on the quality of the spectra of anaerobic bacteria for identification at the species level (Chean et al. 2014; Veloo et al. 2014).

Recently, Shafer et al. (2017) reported that the number of smeared cells on the target plate is important to have an acceptable identification outcome. They suggested 107–108 bacterial cells provide the acceptable spectral resolution. They also made clear that uniformity and smoothness of smeared cells on the target plates are important to have good results.

Meat is one of the most perishable foods owing to its high water activity, suitable pH and its composition (Húngaro et al. 2016). Meat spoilage involves different chemical and biological activities, leading to undesirable odors and tastes, discoloration, and unsafe foods for human consumption as well as economic issues due to food losses (Húngaro et al. 2016; de Koster and Brul 2016). Some of Clostridium species isolated in this study are not considered as food spoilage or food-borne pathogens, rather they are known as human and animal pathogens. One prominent example for such species is Clostridium tetani, which produces a potent neurotoxin and causes life-threatening diseases like tetanus (Bruggemann et al. 2015; Wiegel et al. 2006). In this study, we identified C. tetani in 6.25% of isolates. Clostridium sordellii is an uncommon human pathogen but virulent strains cause fatal infections in a wide range of animals, such as cattle and sheep (Kozma-Sipos et al. 2010; Vidor et al. 2015). In this study, we found C. sordellii in 7.5% of isolates. There are some reports of bacteremia and other infections in immune-compromised individuals from non-toxigenic species such as C. cadaveris and C. tertium (Salvador et al. 2013; Shinha 2015; You et al. 2015). In our study, the abundance of C. cadaveris and C. tertium in the isolates were 12.5 and 8.33%, respectively. C. perfringens is a common cause of food-borne gastrointestinal diseases in humans. According to the production of four major toxins of alpha (α), beta (β), epsilon (ε), and iota (ı), strains are classified into five toxin types (A–E). Important human illnesses caused by C. perfringens are gas gangrene and food poisoning (Aras and Hadimli 2015). In the present study, C. perfringens was found in 10.4% of isolates.

Psychrotolerant clostridia, such as C. algidixylanolyticum, C. estertheticum, C. frigidicarnis, and C. gasigenes, were found in 12.5% of isolates in this study. These bacteria cause blown pack spoilage in vacuum-packed meat resulting in high amounts of drip, gas, unpleasant odor, and discolored and tender meat (Adam et al. 2013). Some authors have shown that even the existence of as few as four spores/cm2 on the meat surface significantly decreased the shelf life of chilled, vacuum-packed meats (Húngaro et al. 2016).

The main sources of Clostridium species are soil and the intestinal tracts of humans and animals. Since the animals being studied in the slaughterhouse, representative of slaughterhouses located in Tehran, were never washed or cleaned before arriving at the plant or before skinning, it is proposed that Clostridium species could enter the abattoir via the hides of animals and are spread through the skinning process throughout the production line and environment of the cattle and sheep slaughterhouse. In general, contamination in slaughterhouses occurs due to inadequate hygienic conditions especially in handling of carcasses (Bakhtiary et al. 2016). Carcasses can be contaminated microbiologically during slaughtering process by different routes such as contact with the hides, equipment, and facilities, workers’ hands, as well as rupture of the viscera and spread of gut contents on the carcasses (Salmela et al. 2013). Consequently, the viscera must be removed intact and the anal sphincter with rectum also must be carefully separated from the carcass.

In this study the Clostridium species were mainly isolated from carcasses after skinning and evisceration in the slaughterhouse. Our preference was identification of different isolates from each sample, rather than different samples per slaughterhouse.

After evisceration, animal carcasses were physically decontaminated by trimming and washing using high-pressure cold water before entering the cooling section. The main purpose of carcass washing is to remove visible contamination such as blood stains and improve carcass appearance after chilling. Suspended carcasses should be washed thoroughly by jet water with appropriate pressure from the top of the carcass in a downward direction in adequate time. Madden et al. (2004) confirmed that washing with cold water is not effective to reduce bacterial load on carcasses, while Koohdar (2013) reported carcass washing with cold water has a significant effect on decreasing microbial populations. In our study, Clostridium species were found in sheep and cattle carcasses after washing. Additionally, they were detected in meat samples. In general, the load of bacteria from live animals entering the slaughterhouses decreases when slaughtering processes and sanitary programs work effectively (Narvaez-Bravo et al. 2013). Based on our results, adequate sanitary procedures need to be implemented to reduce cross contaminations in the slaughterhouse. These include a better availability of knife sterilizers with hot water (82 °C), performing the bleeding cut at the neck when the carcass is hanging on the bleeding rail, using automatic hide removal systems in sheep slaughter lines, cleaning the animal before slaughtering, no exposure of skinned carcass surfaces to the hide as well as to the hands of workers and furthermore, training the meat handlers in the concepts and requirements of personal hygiene. Food safety management system (FSMS) implementation should be mandatory for all stages of the meat supply chain in Iran. All meat companies and slaughterhouses should have a FSMS based on good manufacturing practices (GMPs) and the hazard analysis critical control points (HACCPs) principles in order to minimize carcass contamination with soil, feces and intestinal contents to avoid contamination with Clostridium bacteria and effectively manage microbial hazards. Höll et al. (2016) found the type of breed and farm practices could have significant roles in developing the initial bacterial contamination and resulting in further spoilage after slaughtering.

In addition to good hygiene practice in slaughterhouses and meat plants, a strict control of temperature during the cold chain is important to prevent food spoilage and food-borne diseases by Clostridium species. For example, storage of vacuum-packed meat at −1.5 °C increases shelf life and reduces microbial spoilage (Húngaro et al. 2016; Prevost et al. 2013).

To the author’s knowledge, the present study is the first report of the identification of Clostridium species derived from the slaughterhouse by MALDI-TOF in Iran. Our study provides information regarding Clostridium spp. contamination in slaughterhouses and underlines possible sources of contamination. In the present study, we investigated the identification of different isolates of Clostridium spp. derived from slaughterhouse samples by comparing MALDI-Biotyper and 16S. However, it was not possible to differentiate Clostridium species down to subspecies level. Therefore, the number of different strains in the isolates remains uncertain. Further work will focus on a deeper molecular characterization for differentiation of isolates in order to track down sources of Clostridium species contamination in slaughterhouses. Our study suggests the addition of further Clostridium species including Psychrotolerant clostridia to the database which may then allow a better identification of Clostridium spp. in the meat industry.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrated that MALDI-TOF MS is an accurate method to identify Clostridium species derived from slaughterhouses, at the species level. However, continuous improvement of the MALDI-TOF MS database with food spoilage bacteria and food-borne pathogens and standardization of culture conditions will develop its application in the food industry for identification and tracking sources of microbial contamination along the food chain.

In MALDI-TOF MS identification using EDT sample preparation method from fresh cultures could improve Clostridium spp. identification in comparison to the DT method. Moreover, 16S rDNA gene sequencing analysis could be used as a complementary method for MALDI-TOF MS to verify the identification of the organism. As our results are based on samples taken from one slaughterhouse, investigating the Clostridium species contamination in several slaughterhouses located in different areas will provide more information about Clostridium contaminations. In general, implementation of hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) system at all stages of the meat supply chain will help to adequately manage microbial hazards.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adam KH, Flint SH, Brightwell G. Reduction of spoilage of chilled vacuum-packed lamb by psychrotolerant clostridia. Meat Sci. 2013;93(2):310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agustini BC, Silva LP, Bloch C, Jr, Bonfim TMB, et al. Evaluation of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for identification of environmental yeasts and development of supplementary database. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(12):5645–5654. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alispahic M, Christensen H, Hess C, Razzazi-Fazeli E, et al. Identification of Gallibacterium species by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry evaluated by multilocus sequence analysis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlMogbel MS. Matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of Clostridium species isolated from Saudi Arabia. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47(2):410–413. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeletti S. Matrix assisted laser desorption time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) in clinical microbiology. J Microbiol Methods. 2017;138:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aras Z, Hadimli HH. Detection and molecular typing of Clostridium perfringens isolates from beef, chicken and turkey meats. Anaerobe. 2015;32:15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiary F, Sayevand HR, Remely M, Hippe B, Hosseini H, Haslberger AG. Evaluation of bacterial contamination sources in meat production line. J Food Qual. 2016;39:750–756. doi: 10.1111/jfq.12243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bano L, Drigo I, Tonon E, Pascoletti S, et al. Identification and characterization of Clostridium botulinum group III field strains by matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) Anaerobe. 2017;48:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barba MJ, Fernandez A, Oviano M, Fernandez B, et al. Evaluation of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for identification of anaerobic bacteria. Anaerobe. 2014;30:126–128. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggemann H, Brzuszkiewicz E, Chapeton-Montes D, Plourde L, et al. Genomics of Clostridium tetani. Res Microbiol. 2015;166(4):326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt J, Cross KL, Peck MW. Apertures in the Clostridium sporogenes spore coat and exosporium align to facilitate emergence of the vegetative cell. Food Microbiol. 2015;51:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chean R, Kotsanas D, Francis MJ, Palombo EA, et al. Comparing the identification of Clostridium spp. by two matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry platforms to 16S rRNA PCR sequencing as a reference standard: a detailed analysis of age of culture and sample preparation. Anaerobe. 2014;30:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Koster C, Brul S. MALDI-TOF MS identification and tracking of food spoilers and food-borne pathogens. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2016;10:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2016.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doern CD. Charting uncharted territory: a review of the verification and implementation process for matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) for organism identification. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2013;35(9):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2013.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doulgeraki AL, Ercolini D, Villani F, Nychas GJE. Spoilage microbiota associated to the storage of raw meat in different conditions. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;157(2):130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier R, Wallet F, Grandbastien B, Dubreuil L, et al. Chemical extraction versus direct smear for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification of anaerobic bacteria. Anaerobe. 2012;18(3):294–297. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse-Herrenthey A, Maier T, Gessler F, Schaumann R, et al. Challenging the problem of clostridial identification with matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) Anaerobe. 2008;14(4):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez C, Gómez-Flechoso M, Belda I, Ruiz J, et al. Wine yeasts identification by MALDI-TOF MS: optimization of the preanalytical steps and development of an extensible open-source platform for processing and analysis of an in-house MS database. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017;254:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höll L, Behr J, Vogel RF. Identification and growth dynamics of meat spoilage microorganisms in modified atmosphere packaged poultry meat by MALDI-TOF MS. Food Microbiol. 2016;60:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YMS, Burnham CAD. MALDI-TOF MS identification of anaerobic bacteria: assessment of pre-analytical variables and specimen preparation techniques. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79(2):144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Húngaro H, Caturla M, Horita C, Furtado M, et al. Blown pack spoilage in vacuum-packaged meat: a review on clostridia as causative agents, sources, detection methods, contributing factors and mitigation strategies. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2016;52:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2016.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim S, Park H, Park D, et al. MALDI-TOF MS is more accurate than VITEK II ANC card and API Rapid ID 32 A system for the identification of Clostridium species. Anaerobe. 2016;40:73–75. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koohdar VA. Study of beef carcass bacterial contamination in Karaj Slaughterhouse. J Food Hyg. 2013;3:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kozma-Sipos Z, Szigeti J, Asvanyi B, Varga L. Heat resistance of Clostridium sordellii spores. Anaerobe. 2010;16(3):226–228. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Pascall MA. Inactivation of Clostridium sporogenes spores on stainless-steel using heat and an organic acidic chemical agent. J Food Eng. 2012;110(3):493–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madden RH, Murray KA, et al. Determination of the principal points of product contamination during beef carcass dressing processes in Northern Ireland. J Food Prot. 2004;67(7):1494–1496. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-67.7.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacef M, Chevalier M, Chollet S, Drider D, et al. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from a French cheese: the Maroilles. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim F, Zareifard MR, Zhu S, Huizing RH, et al. Combined effects of heat, nisin, and acidification on the inactivation of Clostridium sporogenes spores in carrot-alginate particles: from kinetics to process validation. Food Microbiol. 2008;25(7):936–941. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez-Bravo C, Rodas Gonzalez A, Fuenmayor Y, Flores-Rondon C, et al. Salmonella on feces, hides, and carcasses in beef slaughter facilities in Venezuela. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;166(2):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost S, Cayol J, Zuber F, Tholozan J, et al. Characterization of clostridial species and sulfite-reducing anaerobes isolated from foie gras with respect to microbial quality and safety. Food Control. 2013;32(1):222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.11.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randall LP, Lemma F, Koylass M, Rogers J, et al. Evaluation of MALDI-TOF as a method for the identification of bacteria in the veterinary diagnostic laboratory. Res Vet Sci. 2015;101:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo-Solano M, Valenzuela-Martinez C, Cassada DA, Snow DD, Juneja VK, Burson DE, et al. Effect of meat ingredients (sodium nitrite and erythorbate) and processing (vacuum storage and packaging atmosphere) on germination and outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens spores in ham during abusive cooling. Food Microbiol. 2013;35(2):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remely M, Dworzak S, Hippe B, Zwielehner J, et al. Abundance and diversity of microbiota in type 2 diabetes and obesity. J Diabetes Metab. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Salmela SP, Fredriksson-Ahomaa M, Hatakka M, Nevas M. Microbiological contamination of sheep carcasses in Finland by excision and swabbing sampling. Food Control. 2013;31(2):372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador F, Porte L, Durin L, Marcotti A, et al. Breakthrough bacteremia due to Clostridium tertium in a patient with neutropenic fever, and identification by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(11):1062–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng P, Drancourt M, Gouriet F, La Scola B, et al. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(4):543–551. doi: 10.1086/600885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer D, Liu H, Dong J, Liu W, et al. Comparison of direct smear and chemical extraction methods for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification of clinical relevant anaerobic bacteria. Front Lab Med. 2017;1(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.flm.2017.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinha T. Bacteremia Due to Clostridium cadaveris. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2015;24(4):232–233. doi: 10.1097/IPC.0000000000000274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AR, Tahara ACC, Chaves RD, Sant’ana AS, et al. Influence of different shrinking temperatures and vacuum conditions on the ability of psychrotrophic Clostridium to cause “blown pack” spoilage in chilled vacuum-packaged beef. Meat Sci. 2012;92(4):498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TeKippe EME, Shuey S, Winkler DW, Butler MA, et al. Optimizing identification of clinically relevant Gram-positive organisms using the Bruker Biotyper MALDI-TOF MS system. J Clin Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JCM.02680-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veloo ACM, Erhard M, Welker M, Welling GW, et al. Identification of Gram-positive anaerobic cocci by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2011;34(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veloo ACM, Knoester M, Degener JE, Kuijper EJ, et al. Comparison of two matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry methods for the identification of clinically relevant anaerobic bacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(10):1501–1506. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veloo ACM, Welling GW, Degener JE. The identification of anaerobic bacteria using MALDI-TOF MS. Anaerobe. 2011;17(4):211–212. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veloo ACM, Elgersma PE, Friedrich AW, Nagy E, et al. The influence of incubation time, sample preparation and exposure to oxygen on the quality of the MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of anaerobic bacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(12):1091–1097. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidor C, Awad M, Lyras D. Antibiotic resistance, virulence factors and genetics of Clostridium sordellii. Res Microbiol. 2015;166(4):368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegel J, Tanner R, Rainey FA. an introduction to the family Clostridiaceae. Prokaryotes. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- You MJ, Shin GW, Lee CS. Clostridium tertium bacteremia in a patient with glyphosate ingestion. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:4–7. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.891287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]