Abstract

Introduction

Syphilis is an important sexually transmitted infection (STI). Despite inexpensive and effective treatment, few key populations receive syphilis testing. Innovative strategies are needed to increase syphilis testing among key populations.

Areas covered

This scoping review focused on strategies to increase syphilis testing in key populations (men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, people who use drugs, transgender people, and incarcerated individuals).

Expert commentary

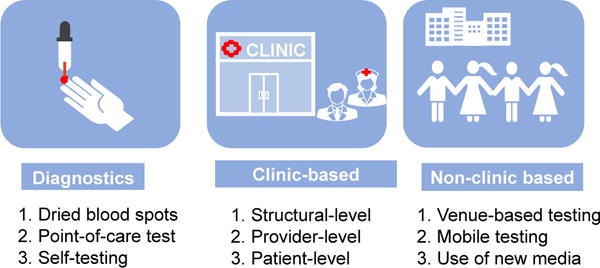

We identified many promising syphilis testing strategies, particularly among MSM. These innovations are separated into diagnostic, clinic-based, and non-clinic based strategies. In terms of diagnostics, self-testing, dried blood spots, and point-of-care testing can decentralize syphilis testing. Effective syphilis self-testing pilots suggest the need for further attention and research. In terms of clinic-based strategies, modifying default clinical procedures can nudge physicians to more frequently recommend syphilis testing. In terms of non-clinic based strategies, venue-based screening (e.g. in correctional facilities, drug rehabilitation centres) and mobile testing units have been successfully implemented in a variety of settings. Integration of syphilis with HIV testing may facilitate implementation in settings where individuals have increased sexual risk. There is a strong need for further syphilis testing research and programs.

1. INTRODUCTION

Syphilis is a perennial global public health problem1. Syphilis is one of the four most common curable sexually transmitted infections (STI), with an estimated 5.6 million individuals age 15-49 years newly infected in 20122. Concern over syphilis related morbidity and mortality of women and their babies has resulted in international attention focused on the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of syphilis3. However, there is relatively less literature devoted to screening key populations at high risk for syphilis: sex workers (SW), men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender people, people who use drugs (PWUD), and those in incarceration. Although the term key population was developed with reference to HIV, in this paper we refer to the same groups related to syphilis. Without effective interventions, syphilis epidemics in key populations are likely to expand1.

In the absence of a vaccine, controlling syphilis relies on timely diagnosis and treatment of those who are infected. In particular, modelling studies suggest frequent key population syphilis testing can reduce prevalence4,5. WHO guidelines recommend syphilis testing for sexually active members of key populations at least once a year, and testing every 3 months for those at higher risk3. Yet most countries do not have specific syphilis testing guidelines or dedicated resources for syphilis prevention and control. Syphilis control measures have been plagued by challenges related to diagnostics, clinic and non-clinic related barriers. From a diagnostics perspective, limited accessibility to diagnostics in some settings, unfavourable incentive or reimbursement structures, and related health systems issues contribute to difficulties of encouraging syphilis testing in key populations2. Clinic-related barriers to syphilis testing include lack of national guidelines, confusing serologies, lack of time/staff, discomfort with sexual history taking and genital examination, lack of testing and treatment knowledge among providers6. Non-clinic related barriers include stigma associated with STI and testing, patient perceptions of low STI risk, burdensome testing procedures and concern over confidentiality of status7,8. Accurate knowledge of one’s STI status is critical as early diagnosis and treatment results in reduced morbidity and risk of onward transmission.

The review literature to date on syphilis testing has focused on advances in diagnostics but not public health strategies to improve syphilis testing in key populations9,10. The aim of this scoping review is to summarize original research on syphilis testing strategies among key populations, focused on diagnostics9,11, clinic-based testing strategies, and non-clinic-based testing strategies12–16. We highlight key examples that illustrate effective strategies and suggest areas for future research.

2. METHODS

We used a scoping review methodology to examine the literature on syphilis testing strategies in key populations17. We searched PubMed and Google Scholar for studies published in English from January 1st 2000 to November 1st 2017. Search terms used were [syphilis AND (screening OR test OR surveillance OR diagnosis OR intervention OR trial OR demonstration OR project OR program). We also searched for results according to the key populations, for example adding (men OR men who have sex with men OR gay OR trans* OR transgender OR prisoner OR people who use drugs OR people who inject drugs OR drug user OR injection drug user OR incarcerated OR sex worker). Hand searches of the references of relevant manuscripts was also performed.

We present the summarized information under the following categories (Figure 1): 1) novel diagnostics for syphilis testing, 2) clinic-based strategies, and 3) non-clinic and community based strategies. Finally, we provide an expert commentary to identify gaps in the existing evidence and suggestions for future research activity.

Figure 1.

Topic areas of diagnostic, clinic- and non-clinic-based strategies to expand syphilis testing in key populations.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Innovations in syphilis diagnostics

Syphilis diagnostics have not changed substantially in the past century. Darkfield microscopy has been used to detect the spirochete of syphilis since its discovery in 1905 by Schaudinn and Hoffman18. Subsequently, the first serological test was developed in 1910 and the first test specific for treponemal antibody in 194918. Traditionally, screening algorithms begin with a non-treponemal specific antibody test (e.g. rapid plasma reagin, RPR) followed by a treponemal specific antibody test (e.g. Treponema pallidum particle agglutination, TPPA). Alternatively, specimen batch testing using a reverse diagnostic algorithm by using a treponemal specific antibody test first followed by a non-treponemal specific antibody test has made testing more cost-efficient and reduced the rate of false-positive RPRs19,20. Other new diagnostics such as automated chemilluminescent micro-particle immunoassay (CLIA) have been developed21. However, all these tests are still time consuming and requires laboratory staff with technical expertise and specialized equipment.

Though traditional testing for syphilis is clinic-based, recent developments have enabled decentralized key population testing. This includes dried blood spots, point-of-care testing, and self-testing.

3.1.1 Dried blood spots (DBS)

DBS is a form of sampling where blood is blotted and dried on filter paper, and sent to a laboratory for serological testing. This is a form of self-collection, but not self-testing. Several studies among MSM suggest willingness to self-collect testing specimens at home13,14. DBS syphilis testing has not yet been approved by regulatory agencies. DBS advantages include the following: specimens can be returned through the postal service for processing; allows integration with testing for other infections such as HIV, hepatitis B and C14,22,23. A study of 217 MSM living in the Netherlands evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of DBS syphilis testing14. The majority (80%) of men found DBS acceptable. Importantly, there was no difference in the adequacy of the specimen collected to enable serological testing between self-collected DBS compared to health worker collected DBS, and overall 91% of DBS had sufficient specimen to test for three infections: HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis. Using routine diagnostics as the gold standard, the sensitivity of DBS for syphilis was 91% and specificity was 99%14.

3.1.2 Point-of-care (POC) testing

POC testing involves conducting syphilis testing with results given within a short time, at or near the site of patient care by trained health providers24. POC testing by trained outreach staff or community health workers might be an important strategy to reach key population in addition to health providers. POC tests to detect treponemal antibodies are increasingly accessible and perform well in the field9,11. These automated POC platforms are portable, enable anonymous testing and are relatively easy to use, eliminating the need for venepuncture and laboratory support. Important trade-offs are that though POC tests have generally comparable performance characteristics to laboratory based testing, POC tests have poorer sensitivity, especially at lower RPR levels (<1:16)25. Another limitation is that most POC syphilis tests detect only anti-treponemal specific antibodies. However, there is one commercially available POC test in some countries which incorporates testing for both treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies. Compared to conventional laboratory testing, it has a sensitivity of 89.8% (95% CI: 87.3-91.9) and specificity of 99.3% (95% CI: 97.0-99.9) for treponemal antibodies, and sensitivity of 94.2% (95% CI: 91.8-96.0) and specificity of 62.2% (95% CI: 57.5-66.6) for non-treponemal antibodies26. Development of further combination point-of-care tests would be useful for those treated for past syphilis or in settings with endemic yaws.

There has also been increasing interest in concurrent POC testing of syphilis and HIV using the same specimen (i.e. dual testing), given their similar transmission routes. The feasibility of introducing dual POC testing has been tested in a wide variety of settings: STI clinic attendees in the US27, pregnant women in rural Uganda28 and Nepal29, MSM and transgender women in Peru30, and female sex workers (FSW) in Johannesburg31. Dual POC testing is accurate32,33 and cost-effective among pregnant women compared to single rapid diagnostic test34. Currently, there is WHO guidance of the use of dual POC testing in antenatal women, but not for key populations35.

3.1.3 Syphilis self-testing

Syphilis self-testing is the process whereby an individual collects a specimen, performs the test and interprets the result. This can be done unsupervised at home, supervised in community clinics, or in other settings. This method of testing has the advantages of providing a user-friendly, rapid, accurate and private means of testing – many of these characteristics are important to key populations36. An expanding literature on HIV self-testing37,38 alongside policy momentum led the World Health Organization to develop guidelines recommending HIV self-testing39. Accordingly, the concept of syphilis self-testing has been implemented among MSM in the Netherlands40 and China36. This approach could help to increase first-time testing among individuals who do not want to seek care in a clinic-based setting. To date, there are no regulatory guidelines for syphilis self-testing use among key populations. Although syphilis self-test kits are available for private purchase41,42, more evidence of this approach is needed to develop other pilot programs.

3.2 Clinic-based testing strategies

Clinic-based testing strategies seek to improve screening uptake by modifying existing clinical practice, with the aim to motivate greater testing uptake, and increase detection of asymptomatic syphilis. These interventions typically target structural, provider, or patient levels.

3.2.1 Structural interventions

The two main types of structural interventions involve those that lower barriers to sexual healthcare access and those that modify clinic flow practices to improve service delivery. Interventions to address barriers to care have largely focused on key populations, often through the creation of specialized clinics for FSW43 or MSM44, provision of clinic vouchers45, or implementation of a culturally sensitive and comprehensive care models46. Strategies to address clinic procedures include those routinizing syphilis testing47—particularly for people living with HIV48–50—through use of novel diagnostic tools for same day diagnosis51, and the use of technology (e.g. internet, text messages) to enhance public health services such as test result notification52,53 or partner notification54,55.

3.2.2 Provider-level interventions

Provider-level interventions to improve syphilis screening have consisted of task shifting, integration with HIV services, and physician reminders. Task shifting is where responsibility for certain clinical tasks are transferred, when appropriate, to less specialized health care staff. Several sexual health clinics in the United States, Australia and the Netherlands, have adopted nurse-led approaches in which nurses stand in for physicians as the first-line sexual health providers56. In the United States57 and Ireland58, primary care physicians have received specialised training in sexual health service provision, whereas a pilot study in the United Kingdom embedded sexual health specialists in HIV care clinics59. These strategies decentralize sexual health services and improve detection of more asymptomatic cases by introducing screening into primary care settings. Integration of syphilis and HIV testing at clinics is another strategy. One study60 and one large implementation project61 suggest that integration of syphilis and HIV testing is feasible and acceptable in clinical settings. Finally, automated reminders have been used to encourage syphilis counselling and testing among MSM in clinics4,62.

3.2.3 Patient-level interventions

Syphilis screening strategies at the patient level have included internet and text-message assisted strategies to regularly remind patients to initially screen63 or retest for syphilis64. Encouraging results from these two studies support the use of text messages for promoting syphilis testing. Monetary incentives have been used to improve testing for HIV and other STIs65,66, including syphilis testing66. The syphilis test incentive study offered individuals with drug addiction or unstable housing small rewards for obtaining their syphilis results or seeking treatment if required66. Further research is needed to assess the cost-effectiveness for providing financial incentives to increase syphilis testing uptake.

3.3 Non-clinic and community based testing strategies

Although screening for syphilis to date has primarily been conducted in clinic-based settings10,67, advances in STI diagnostics have increased the number of non-clinic and community-based settings where syphilis testing is feasible12–14,68. Advantages of non-clinic and community-based testing include reaching individuals who may not seek clinical services, and integrating testing within existing community-based services in collaboration with local partners. Community-based syphilis testing strategies for key populations through outreach at entertainment or commercial sex venues and mobile testing units have proven to be effective in reaching key populations31,69. These testing approaches have been integrated into routine STI surveillance systems70. Furthermore, internet and social network based testing and promotion have been used to scale up earlier diagnosis of syphilis in key populations71–73.

This section reviews syphilis testing interventions outside of clinic settings, including screening conducted in venues (such as correctional settings and drug rehabilitation facilities), mobile sites (such as perioidic outreach services provided at entertainment/sex venues and through mobile testing units), and through campaigns using social networks.

3.3.1 Venue-based syphilis testing

Universal screening for syphilis has been provided in jails and other correctional settings in several countries50,69,74–76. Success of the venue-based strategy depends on the local epidemiology of syphilis. Data from STI screening conducted at correctional facilities in the United States suggests a high syphilis prevalence in the incarcerated populations, and programs have been particularly successful for identifying syphilis outbreaks in heterosexuals76–80. Although syphilis testing in correctional facilities introduces a range of special challenges, it also provides unique opportunities for expanding syphilis testing50,75.

Similarly, routine screening of syphilis in PWUD have been conducted at drug use rehabilitation and treatment facilities, including methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) clinics and syringe exchange programs in a few countries81–90. For example, syphilis screening is integrated into the national drug rehabilitation system as a standard medical service for PWUD in China87,91. PWUD receiving MMT are routinely screened for syphilis together with HIV and HCV87. Findings demonstrated the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of integrating syphilis screening into existing PWUD programs87,88.

3.3.2 Mobile testing sites

Mobile STI screening programs are particularly well suited for populations in rural, low-income communities or areas with disproportionately high syphilis burden92–95. Mobile van testing services have successfully provided services at community events (e.g. Gay Pride parades and parties) or at sex/entertainment venues where higher risk sex often takes place96. Mobile vans have also been used to deliver syphilis testing services to target high risk populations in other developing and developed countries, such as Russia93,97–100, Peru101 and Guatemala102. This research suggests that mobile testing units effectively expand first-time syphilis testing among a subset of key populations that do not access clinical services95,96,102.

Periodic outreach syphilis testing services have been conducted at entertainment or sex venues, for example, brothels, gay bars, bathhouses. These programs have increased syphilis testing among PWUD81,98,103–105, 106–108, MSM31,51,109–111 and transgender people112. For example, health outreach teams in two Chinese cities offered free onsite rapid syphilis testing to approached at various types of commercial sex venues107. Among the FSW who were offered rapid syphilis testing, 95% accepted the test; 7% tested positive, among which 75% agreed to visit an STI clinic for confirmatory testing, and 66% were willing to notify their partners of the test result107.

3.3.3 Use of new communication technologies to increase syphilis testing

We define new communication technologies as mass communication using digital technologies such as social networking platforms. Public campaigns through targeted messaging interventions have been used to increase syphilis knowledge and testing. These programs have focused on MSM and transgender people110,113,114. Mixed findings were reported. For example, a syphilis awareness public campaign targeting MSM in eight U.S. cities using social marketing approach reported an increased awareness of syphilis in some cities and increased syphilis testing associated with campaign participation113. However, the “Check Yourself “public campaign conducted in Los Angeles in the U.S. did not find a significant association between campaign awareness and syphilis testing in MSM114. Among technology-focused testing strategies, crowdsourcing is another approach to developing new syphilis testing campaigns. Crowdsourcing is the process of having a group solve a problem and then sharing the solution with the public115. Crowdsourcing has been used to solicit novel content for promotional images, videos, and HIV testing strategies. A stepped wedge trial randomized controlled trial evaluating this approach is underway and includes syphilis testing as a secondary outcome116. Cross-sectional data from this study suggested that dual HIV/syphilis self-testing promoted through the internet could be a feasible approach for increasing syphilis testing among MSM117.

There is a small but growing literature that examines the internet as a platform for distributing syphilis test kits, self-collection kits, or non-clinical testing15,118–121. Two pilot studies allow MSM to download a referral letter for presentation at a testing laboratory for a syphilis test; then results were received online122,123. However, both sites found that fewer than 10% of those who requested a letter received a test kit122,123. Other studies have examined new technologies as tools to promote syphilis testing15,16,124–126 including using Facebook and Twitter124,125; online research surveys on gay websites15,16. However, linkage to clinic-based syphilis testing from banner advertisements was less than 20% in both studies that measured it15,16. A study which evaluated the effect of a social network-based campaign on STI testing use in youths reported a significant increase in syphilis testing (from 5% to 19%, pre- and post-campaign)124. Another study evaluating automated text message and email reminders promoting syphilis re-testing among MSM increased detection of syphilis63.

4. EXPERT COMMENTARY

Several key insights can be gained from this review. Table 1 provides a summary of syphilis testing strategies organized by key population. This suggests that most syphilis testing programs have focused on MSM, with comparatively less attention devoted to SW, incarcerated individuals, PWUD and transgender populations. These gaps underscore the future work needed to assess these identified strategies in other key populations. Although they may share similar structural and societal disadvantages related to accessing healthcare, key populations also have critical differences from one another. Costs of these programs are quite variable and not well-studied. Future cost-effectiveness studies reporting the cost per test performed and cost per syphilis case successfully treated in key populations may be useful metrics for evaluating the value of these programs. The local epidemiology of syphilis ought to drive which strategy to use and how available resources should be allocated to key populations within each setting. Programs using mobile testing units are in general more costly per case identified (and treated) than other strategies126. However, integration of syphilis testing into an existing program such as one that is testing for HIV is generally less costly60. Structural-level interventions may be more cost-effective than provider- or patient-level interventions, although further empirical research is needed127. In addition, given the extensive literature on HIV testing interventions among key populations128,129, this evidence may help inform the design of syphilis testing strategies. While there are notable differences in these two diseases, the shared opportunities are also substantial. Integrated HIV/syphilis testing programs,60, key population friendly services, and related projects require further implementation research.

Table 1.

Examples of strategies aimed at increasing syphilis testing in key populations

| MSM | SW | Incarcerated | PWUD | Transgender | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostics | |||||

| Dried blood spot | 14 | 23 | |||

| Point-of-care testing | 30 | 31 | 130 | 131 | |

| Self-testing | 36,40 | ||||

| Clinic based | |||||

| Structural | 47–49 | 43,45 | 51 | ||

| Provider | 4,59,62 | ||||

| Patient | 63,64 | ||||

| Non-clinic based strategies | |||||

| Venue-based | 31,78,97,109–111 | 91,132 | 81,83–86,98,103–105 | ||

| Mobile testing | 96,97,101,102,110 | 92,102,108 | 93,97–100 | 101,102 | |

| New communications technology | 15,63,110,113,114,124–126,133 | 134,135 |

MSM = men who have sex with men; PWUD = people who use drugs; SW = sex workers

While recent advancements in syphilis diagnostics have enabled decentralized testing, further research is needed on syphilis test self-collection and self-testing. Given the widespread adoption of HIV self-testing and growing infrastructure to support HIV self-testing, further research on syphilis self-testing is warranted. Another major gap in the literature pertaining to diagnostics, is the lack of discussion regarding innovations in syphilis testing methodologies, e.g. how to rapidly identify active syphilis and bypass the current limitation of POC test kits being unable to accurately distinguish past treated infection from active infection.

Clinic-based strategies are relatively simple tweaks to existing protocols to improve syphilis testing uptake in key populations. By slightly modifying clinical practices, these interventions leverage an existing infrastructure and patient population to increase screening in key populations. Other clinic-based interventions that have been implemented for control of other curable STIs provide guidance for future syphilis control approaches, or integrated control of multiple STIs. Some such strategies include behavioural counselling delivered in clinical settings136,137, automated reminders for providers built into electronic health record systems138,139, and provider-level monetary incentives140,141. Clinic-based strategies should be coupled with simultaneous efforts to improve health seeking behaviours in key populations and reduce individual and structural barriers to access care.

While existing studies showed that non-clinic based programs were effective in improving the access of key populations to syphilis screening services, particularly among those who were more hidden and had higher STI risks12,69,142, few studies have evaluated linkage to care and related services. The gap between testing and treatment services could compromise the effectiveness of these strategies143. In addition, advances in new syphilis testing approaches have yet to translate into clinic seeking and clinic service uptake. Lessons can be learnt from the larger HIV new communications technology literature when designing new syphilis testing strategies144.

5. FIVE-YEAR VIEW

As syphilis remains a persistent global public health threat, innovative ways to generate demand for syphilis testing are needed. Challenge contests and related crowdsourcing approaches could help to identify and nurture local innovation115. Local surveillance data on syphilis diagnosis to delineate the scope of the problem and better data on cost-effectiveness may inform policy makers. With further advancements in diagnostic technologies, there may be a greater role for syphilis self-testing in reaching key populations. In addition, as syphilis testing becomes increasingly decentralized, there is an urgent need to ensure quality of test kits and linkage to comprehensive services.

6. KEY ISSUES

Syphilis is an important sexually transmitted infection and despite inexpensive and effective treatment, few key populations receive syphilis testing. In particular, key populations in need of greater uptake of syphilis testing includes men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, people who use drugs, transgender people, and incarcerated individuals.

Recent strategies to improve syphilis testing in these key populations can be separated into diagnostic, clinic-based, and non-clinic based strategies.

In terms of diagnostics, self-testing, dried blood spots, and point-of-care testing can decentralize syphilis testing. In particular, syphilis self-testing provides an important tool to address the unmet needs of marginalized populations, particularly when it is integrated with other existing services (e.g. HIV testing).

In terms of clinic-based strategies, modifying default clinical procedures can nudge physicians to more frequently recommend syphilis testing.

In terms of non-clinic-based strategies, venue-based screening, mobile testing units and innovative use of social network technologies have been successfully implemented.

7. CONCLUSION

The strategies identified from our review have played an important role in improving syphilis testing targeted towards hidden and hard-to-reach members of key populations who uncommonly access clinic-based services. If the syphilis epidemics among key populations are to be controlled, further work is needed to assess the cost-effectiveness and scalability of these strategies.

References

- 1.Kenyon CR, Osbak K, Tsoumanis A. The Global Epidemiology of Syphilis in the Past Century - A Systematic Review Based on Antenatal Syphilis Prevalence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(5):e0004711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, et al. Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3*.Dual Elimination of HIV and syphilis. http://www.dualelimination.org/dual-tests (accessed 13th April 2017. Lists available dual test kits for HIV and syphilis including links to product information.

- 4.Chow EPF, Callander D, Fairley CK, et al. Increased Syphilis Testing of Men Who Have Sex With Men: Greater Detection of Asymptomatic Early Syphilis and Relative Reduction in Secondary Syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(3):389–95. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray RT, Hoare A, Prestage GP, Donovan B, Kaldor JM, Wilson DP. Frequent testing of highly sexually active gay men is required to control syphilis. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2010;37(5):298–305. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ca3c0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6*.Tucker JD, Bien CH, Peeling RW. Point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections: recent advances and implications for disease control. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2013;26(1):73–9. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835c21b0. Summarizes the issues associated with point-of-care testing for STIs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbee L, Dhanireddy S, Tat SA, Marrazzo JM. Barriers to Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infection Testing of HIV-Infected Men Who Have Sex With Men Engaged in HIV Primary Care. 2015 doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heijman T, Zuure F, Stolte I, Davidovich U. Motives and barriers to safer sex and regular STI testing among MSM soon after HIV diagnosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):194. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker JD, Bu J, Brown LB, Yin YP, Chen XS, Cohen MS. Accelerating worldwide syphilis screening through rapid testing: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(6):381–6. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantor AG, Pappas M, Daeges M, Nelson HD. Screening for Syphilis: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2328–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jafari Y, Peeling RW, Shivkumar S, Claessens C, Joseph L, Pai NP. Are Treponema pallidum specific rapid and point-of-care tests for syphilis accurate enough for screening in resource limited settings? Evidence from a meta-analysis. PloS one. 2013;8(2):e54695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert NL, Fisher M, Imrie J, et al. Community based syphilis screening: feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness in case finding. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(3):213–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wayal S, Llewellyn C, Smith H, Fisher M. Home sampling kits for sexually transmitted infections: preferences and concerns of men who have sex with men. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(3):343–53. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.535018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.van Loo IHM, Dukers-Muijrers N, Heuts R, van der Sande MAB, Hoebe C. Screening for HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis on dried blood spots: A promising method to better reach hidden high-risk populations with self-collected sampling. PloS one. 2017;12(10):e0186722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186722. Advances new methods for reaching hidden populations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruutel K, Lohmus L, Janes J. Internet-based recruitment system for HIV and STI screening for men who have sex with men in Estonia, 2013: analysis of preliminary outcomes. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2015;20(15) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blas MM, Alva IE, Cabello R, et al. Internet as a tool to access high-risk men who have sex with men from a resource-constrained setting: a study from Peru. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(7):567–70. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tampa M, Sarbu I, Matei C, Benea V, Georgescu SR. Brief history of syphilis. J Med Life. 2014;7(1):4–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Syphilis testing algorithms using treponemal tests for initial screening–four laboratories, New York City, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(32):872–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Discordant results from reverse sequence syphilis screening–five laboratories, United States, 2006-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(5):133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang KD, Xu DJ, Su JR. Preferable procedure for the screening of syphilis in clinical laboratories in China. Infect Dis (Lond) 2016;48(1):26–31. doi: 10.3109/23744235.2015.1044465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CE, Sri Ponnampalavanar S, Syed Omar SF, Mahadeva S, Ong LY, Kamarulzaman A. Evaluation of the dried blood spot (DBS) collection method as a tool for detection of HIV Ag/Ab, HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HCV in a Malaysian tertiary referral hospital. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2011;40(10):448–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isac S, Ramesh BM, Rajaram S, et al. Changes in HIV and syphilis prevalence among female sex workers from three serial cross-sectional surveys in Karnataka state, South India. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e007106. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herring AJ, Ballard RC, Pope V, et al. A multi-centre evaluation of nine rapid, point-of-care syphilis tests using archived sera. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 5):v7–12. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.022707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marks M, Yin YP, Chen XS, et al. Metaanalysis of the Performance of a Combined Treponemal and Nontreponemal Rapid Diagnostic Test for Syphilis and Yaws. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):627–33. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Causer LM, Kaldor JM, Conway DP, et al. An evaluation of a novel dual treponemal/nontreponemal point-of-care test for syphilis as a tool to distinguish active from past treated infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(2):184–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holden J, Goheen J, Jett-Goheen M, Barnes M, Hsieh YH, Gaydos CA. An evaluation of the SD Bioline HIV/syphilis duo test. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;956462417717649 doi: 10.1177/0956462417717649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omoding D, Katawera V, Siedner M, Boum Y., 2nd Evaluation of the SD Bioline HIV/Syphilis Duo assay at a rural health center in Southwestern Uganda. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:746. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shakya G, Singh DR, Ojha HC, et al. Evaluation of SD Bioline HIV/syphilis Duo rapid test kits in Nepal. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):450. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bristow CC, Leon SR, Huang E, et al. Field evaluation of a dual rapid diagnostic test for HIV infection and syphilis in Lima, Peru. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92(3):182–5. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Black V, Williams BG, Maseko V, Radebe F, Rees HV, Lewis DA. Field evaluation of Standard Diagnostics’ Bioline HIV/Syphilis Duo test among female sex workers in Johannesburg, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2016 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogozinska E, Kara-Newton L, Zamora JR, Khan KS. On-site test to detect syphilis in pregnancy: a systematic review of test accuracy studies. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2017;124(5):734–41. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin YP, Ngige E, Anyaike C, et al. Laboratory evaluation of three dual rapid diagnostic tests for HIV and syphilis in China and Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(Suppl 1):S22–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bristow CC, Larson E, Anderson LJ, Klausner JD. Cost-effectiveness of HIV and syphilis antenatal screening: a modelling study. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92(5):340–6. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clumeck N, Pozniak A, Raffi F. European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) guidelines for the clinical management and treatment of HIV-infected adults. HIV Med. 2008;9(2):65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong F, Tang W, Cheng W, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a social entrepreneurship testing model to promote HIV self-testing and linkage to care among men who have sex with men. HIV Med. 2017;18(5):376–82. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin Y, Han L, Babbitt A, et al. Experiences using and organizing HIV self-testing. AIDS. 2018;32(3):371–81. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38**.Johnson CC, Kennedy C, Fonner V, et al. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21594. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21594. Lessons from HIV self-testing implemantation that may be adapted for syphilis self-testing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification. 2016 Dec; http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/251655/1/9789241549868-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 16th March 2017. [PubMed]

- 40.Bil JP, Prins M, Stolte IG, et al. Usage of purchased self-tests for HIV and sexually transmitted infections in Amsterdam, the Netherlands: results of population-based and serial cross-sectional studies among the general population and sexual risk groups. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016609. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.STD rapid test kit. https://www.stdrapidtestkits.com/syphilis-rapid-screen-test.html (accessed 11th Jan 2018.

- 42.Global sources syphilis test kit manufacturers and suppliers. http://www.globalsources.com/manufacturers/Syphilis-Test-Kit.html (accessed 11th Jan 2018.

- 43.Steen R, Mogasale V, Wi T, et al. Pursuing scale and quality in STI interventions with sex workers: initial results from Avahan India AIDS Initiative. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(5):381–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Library of Medicine (US) 2016 Nov 21 - Identifier NCT02969915, Strategies to Improve the HIV Care Continuum Among Key Populations in India. 2016 Nov 21; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02969915 (accessed 28th March 2018.

- 45.McKay J, Campbell D, Gorter AC. Lessons for management of sexually transmitted infection treatment programs as part of HIV/AIDS prevention strategies. American journal of public health. 2006;96(10):1760–1. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tu D, Belda P, Littlejohn D, Pedersen JS, Valle-Rivera J, Tyndall M. Adoption of the chronic care model to improve HIV care: in a marginalized, largely aboriginal population. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2013;59(6):650–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryder N, Bourne C, Rohrsheim R. Clinical audit: adherence to sexually transmitted infection screening guidelines for men who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(6):446–9. doi: 10.1258/0956462054093980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48**.Bissessor M, Fairley CK, Leslie D, Howley K, Chen MY. Frequent screening for syphilis as part of HIV monitoring increases the detection of early asymptomatic syphilis among HIV-positive homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(2):211–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e583bf. Practical example of how modifying default clinical procedure can improve syphilis detection. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Botes LP, McAllister J, Ribbons E, Jin F, Hillman RJ. Significant increase in testing rates for sexually transmissible infections following the introduction of an anal cytological screening program, targeting HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Sex Health. 2011;8(1):76–8. doi: 10.1071/SH10027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen CE, Winston A, Asboe D, et al. Increasing detection of asymptomatic syphilis in HIV patients. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(3):217–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blank S, McDonnell DD, Rubin SR, et al. New approaches to syphilis control. Finding opportunities for syphilis treatment and congenital syphilis prevention in a women’s correctional setting. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1997;24(4):218–26. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen AC, Zimmerman F, Prelip M, Glik D. A Smartphone Application to Reduce Time-to-Notification of Sexually Transmitted Infections. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(11):1795–800. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodriguez-Hart C, Gray I, Kampert K, et al. Just text me! Texting sexually transmitted disease clients their test results in Florida, February 2012-January 2013. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(3):162–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hightow-Weidman L, Beagle S, Pike E, et al. “No one’s at home and they won’t pick up the phone”: using the Internet and text messaging to enhance partner services in North Carolina. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(2):143–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pennise M, Inscho R, Herpin K, et al. Using smartphone apps in STD interviews to find sexual partners. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(3):245–52. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miles K, Knight V, Cairo I, King I. Nurse-led sexual health care: international perspectives. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(4):243–7. doi: 10.1258/095646203321264845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen JL, Kodagoda D, Lawrence AM, Kerndt PR. Rapid public health interventions in response to an outbreak of syphilis in Los Angeles. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(5):277–84. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelly C, Johnston J, Carey F. Evaluation of a partnership between primary and secondary care providing an accessible Level 1 sexual health service in the community. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(10):751–7. doi: 10.1177/0956462413519430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Snow AF, Vodstrcil LA, Fairley CK, et al. Introduction of a sexual health practice nurse is associated with increased STI testing of men who have sex with men in primary care. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:298. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tucker JD, Yang LG, Yang B, et al. A twin response to twin epidemics: integrated HIV/syphilis testing at STI clinics in South China. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;57(5):e106–11. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821d3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang W, Luo H, Ma Y, et al. Monetary incentives for provision of syphilis screening, Yunnan, China. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2017;95(9):657–62. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.191635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bissessor M, Fairley CK, Leslie D, Chen MY. Use of a computer alert increases detection of early, asymptomatic syphilis among higher-risk men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(1):57–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zou H, Fairley CK, Guy R, et al. Automated, computer generated reminders and increased detection of gonorrhoea, chlamydia and syphilis in men who have sex with men. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e61972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bourne C, Knight V, Guy R, Wand H, Lu H, McNulty A. Short message service reminder intervention doubles sexually transmitted infection/HIV re-testing rates among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(3):229–31. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.048397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee R, Cui RR, Muessig KE, Thirumurthy H, Tucker JD. Incentivizing HIV/STI testing: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS and behavior. 2014;18(5):905–12. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0588-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Geringer WM, Hinton M. Three models to promote syphilis screening and treatment in a high risk population. Journal of community health. 1993;18(3):137–51. doi: 10.1007/BF01325158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gliddon HD, Peeling RW, Kamb ML, Toskin I, Wi TE, Taylor MM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating the performance and operational characteristics of dual point-of-care tests for HIV and syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-053069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cohen DA, Kanouse DE, Iguchi MY, Bluthenthal RN, Galvan FH, Bing EG. Screening for sexually transmitted diseases in non-traditional settings: a personal view. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(8):521–7. doi: 10.1258/0956462054679115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bernstein KT, Chow JM, Pathela P, Gift TL. Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Disease Screening Outside the Clinic–Implications for the Modern Sexually Transmitted Disease Program. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43(2 Suppl 1):S42–52. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.An Q. Syphilis Screening and Diagnosis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men, 2008-2014, 20 U.S. Cities. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2017;75(Suppl 3):S363–s9. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Benzaken AS. Acceptable interventions to reduce syphilis transmission among high-risk men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;105(3):e88–94. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas DR, Williams CJ, Andrady U, et al. Outbreak of syphilis in men who have sex with men living in rural North Wales (UK) associated with the use of social media. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92(5):359–64. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Su JY, Holt J, Payne R, Gates K, Ewing A, Ryder N. Effectiveness of using Grindr to increase syphilis testing among men who have sex with men in Darwin, Australia. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health. 2015;39(3):293–4. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kahn RH, Scholl DT, Shane SM, Lemoine AL, Farley TA. Screening for syphilis in arrestees: usefulness for community-wide syphilis surveillance and control. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(3):150–6. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spaulding AC, MacGowan RJ, Copeland B, et al. Costs of Rapid HIV Screening in an Urban Emergency Department and a Nearby County Jail in the Southeastern United States. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mertz KJ, Voigt RA, Hutchins K, Levine WC, Jail STDPMG Findings from STD screening of adolescents and adults entering corrections facilities: implications for STD control strategies. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2002;29(12):834–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200212000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Ravello L, Brantley MD, Lamarre M, Qayad MG, Aubert H, Beck-Sague C. Sexually transmitted infections and other health conditions of women entering prison in Georgia, 1998-1999. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(4):247–51. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000158494.38034.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Javanbakht M, Murphy R, Harawa NT, et al. Sexually transmitted infections and HIV prevalence among incarcerated men who have sex with men, 2000-2005. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(2 Suppl):S17–21. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815e4152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim AA, Martinez AN, Klausner JD, et al. Use of sentinel surveillance and geographic information systems to monitor trends in HIV prevalence, incidence, and related risk behavior among women undergoing syphilis screening in a jail setting. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2009;86(1):79–92. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen JL, Bovee MC, Kerndt PR. Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance among incarcerated men who have sex with men–an opportunity for HIV prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1 Suppl A):117–26. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.5.117.23614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Azim T, Chowdhury EI, Reza M, et al. Vulnerability to HIV infection among sex worker and non-sex worker female injecting drug users in Dhaka, Bangladesh: evidence from the baseline survey of a cohort study. Harm reduction journal. 2006;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Abdala N, Carney JM, Durante AJ, et al. Estimating the prevalence of syringe-borne and sexually transmitted diseases among injection drug users in St Petersburg, Russia. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(10):697–703. doi: 10.1258/095646203322387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beyrer C, Razak MH, Jittiwutikarn J, et al. Methamphetamine users in northern Thailand: changing demographics and risks for HIV and STD among treatment-seeking substance abusers. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(10):697–704. doi: 10.1177/095646240401501012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carey MP, Ravi V, Chandra PS, Desai A, Neal DJ. Screening for sexually transmitted infections at a DeAddictions service in south India. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2006;82(2):127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Altaf A, Shah SA, Zaidi NA, Memon A, Nadeem ur R, Wray N. High risk behaviors of injection drug users registered with harm reduction programme in Karachi, Pakistan. Harm reduction journal. 2007;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dowe G, Smilkle MF, Thesiger C, Williams EM. Bloodborne sexually transmitted infections in patients presenting for substance abuse treatment in Jamaica. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2001;28(5):266–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang BX, Zhang L, Wang YJ, et al. Epidemiology of syphilis infection among drug users at methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(8):550–8. doi: 10.1177/0956462413515444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coffin LS, Newberry A, Hagan H, Cleland CM, Des Jarlais DC, Perlman DC. Syphilis in drug users in low and middle income countries. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(1):20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Scherbaum N, Baune BT, Mikolajczyk R, Kuhlmann T, Reymann G, Reker M. Prevalence and risk factors of syphilis infection among drug addicts. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zou X, Ling L, Zhang L. Trends and risk factors for HIV, HCV and syphilis seroconversion among drug users in a methadone maintenance treatment programme in China: a 7-year retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008162. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen XS, Wang QQ, Yin YP, et al. Prevalence of syphilis infection in different tiers of female sex workers in China: implications for surveillance and interventions. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mejia A, Bautista CT, Leal L, et al. Syphilis infection among female sex workers in Colombia. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2009;11(2):92–8. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Karapetyan AF, Sokolovsky YV, Araviyskaya ER, Zvartau EE, Ostrovsky DV, Hagan H. Syphilis among intravenous drug-using population: epidemiological situation in St Petersburg, Russia. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13(9):618–23. doi: 10.1258/09564620260216326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kahn RH, Moseley KE, Thilges JN, Johnson G, Farley TA. Community-based screening and treatment for STDs: results from a mobile clinic initiative. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2003;30(8):654–8. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000083892.66236.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ellen JM, Bonu S, Arruda JS, Ward MA, Vogel R. Comparison of clients of a mobile health van and a traditional STD clinic. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2003;32(4):388–93. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, et al. Differential HIV risk behavior among men who have sex with men seeking health-related mobile van services at diverse gay-specific venues. AIDS and behavior. 2009;13(4):822–31. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Deiss RG, Brouwer KC, Loza O, et al. High-risk sexual and drug using behaviors among male injection drug users who have sex with men in 2 Mexico-US border cities. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2008;35(3):243–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815abab5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Frost SD, Brouwer KC, Firestone Cruz MA, et al. Respondent-driven sampling of injection drug users in two U.S.-Mexico border cities: recruitment dynamics and impact on estimates of HIV and syphilis prevalence. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i83–97. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tun W, Vu L, Adebajo SB, et al. Population-based prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus, HIV, syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia in male injection drug users in Lagos, Nigeria. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24(8):619–25. doi: 10.1177/0956462413477553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Platt L, Vickerman P, Collumbien M, et al. Prevalence of HIV, HCV and sexually transmitted infections among injecting drug users in Rawalpindi and Abbottabad, Pakistan: evidence for an emerging injection-related HIV epidemic. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(Suppl 2):ii17–22. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.034090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lipsitz MC, Segura ER, Castro JL, et al. Bringing testing to the people - benefits of mobile unit HIV/syphilis testing in Lima, Peru, 2007-2009. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(5):325–31. doi: 10.1177/0956462413507443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lahuerta M, Sabido M, Giardina F, et al. Comparison of users of an HIV/syphilis screening community-based mobile van and traditional voluntary counselling and testing sites in Guatemala. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(2):136–40. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.043067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rhodes T, Platt L, Maximova S, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis C and syphilis among injecting drug users in Russia: a multi-city study. Addiction. 2006;101(2):252–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lopez-Zetina J, Ford W, Weber M, et al. Predictors of syphilis seroreactivity and prevalence of HIV among street recruited injection drug users in Los Angeles County, 1994-6. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76(6):462–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.6.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Go VF, Frangakis C, Namle V, et al. High HIV sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted disease prevalence among injection drug users in Northern Vietnam: implications for a generalized HIV epidemic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(1):108–15. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000199354.88607.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hong Y, Poon AN, Zhang C. HIV/STI prevention interventions targeting FSWs in China: a systematic literature review. AIDS care. 2011;23(Suppl 1):54–65. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen MY. Rapid syphilis testing uptake for female sex workers at sex venues in Southern China: implications for expanding syphilis screening. BMJ open. 2012;7(12):e52579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dos Ramos Farias MS, Garcia MN, Reynaga E, et al. First report on sexually transmitted infections among trans (male to female transvestites, transsexuals, or transgender) and male sex workers in Argentina: high HIV, HPV, HBV, and syphilis prevalence. International journal of infectious diseases: IJID: official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2011;15(9):e635–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tingey L, Strom R, Hastings R, et al. Self-administered sample collection for screening of sexually transmitted infection among reservation-based American Indian youth. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(9):661–6. doi: 10.1177/0956462414552139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ciesielski C, Kahn RH, Taylor M, Gallagher K, Prescott LJ, Arrowsmith S. Control of syphilis outbreaks in men who have sex with men: the role of screening in nonmedical settings. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2005;32(10 Suppl):S37–42. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000181148.80193.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lorente N, Preau M, Vernay-Vaisse C, et al. Expanding access to non-medicalized community-based rapid testing to men who have sex with men: an urgent HIV prevention intervention (the ANRS-DRAG study) PloS one. 2013;8(4):e61225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pisani E, Girault P, Gultom M, et al. HIV, syphilis infection, and sexual practices among transgenders, male sex workers, and other men who have sex with men in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(6):536–40. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.007500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vega MY. The CHANGE approach to capacity-building assistance. AIDS education and prevention: official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2009;21(5 Suppl):137–51. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Plant A, Javanbakht M, Montoya JA, Rotblatt H, O’Leary C, Kerndt PR. Check Yourself: a social marketing campaign to increase syphilis screening in Los Angeles County. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2014;41(1):50–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tucker JD, Fenton KA. Innovation challenge contests to enhance HIV responses. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(3):e113–e5. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang TP, Liu C, Han L, et al. Community engagement in sexual health and uptake of HIV testing and syphilis testing among MSM in China: a cross-sectional online survey. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21372. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.01/21372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ong JJ, Fu HY, Pan S, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV and syphilis testing among men who have sex with men in China: a cross-sectional study. Sexually Transmitted Disease. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000773. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chai SJ, Aumakhan B, Barnes M, et al. Internet-based screening for sexually transmitted infections to reach nonclinic populations in the community: risk factors for infection in men. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(12):756–63. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e3d771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jamil MS, Hocking JS, Bauer HM, et al. Home-based chlamydia and gonorrhoea screening: a systematic review of strategies and outcomes. BMC public health. 2013;13:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hottes TS, Farrell J, Bondyra M, Haag D, Shoveller J, Gilbert M. Internet-based HIV and sexually transmitted infection testing in British Columbia, Canada: opinions and expectations of prospective clients. Journal of medical Internet research. 2012;14(2):e41. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wilson E, Kenny A, Dickson-Swift V. Ethical Challenges in Community-Based Participatory Research: A Scoping Review. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(2):189–99. doi: 10.1177/1049732317690721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Koekenbier RH, Davidovich U, van Leent EJ, Thiesbrummel HF, Fennema HS. Online-mediated syphilis testing: feasibility, efficacy, and usage. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(8):764–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816fcb0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Levine DK, Scott KC, Klausner JD. Online syphilis testing–confidential and convenient. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(2):139–41. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000149783.67826.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dowshen N, Lee S, Matty Lehman B, Castillo M, Mollen C. IknowUshould2: Feasibility of a Youth-Driven Social Media Campaign to Promote STI and HIV Testing Among Adolescents in Philadelphia. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(Suppl 2):106–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0991-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Friedman AL, Brookmeyer KA, Kachur RE, et al. An assessment of the GYT: Get Yourself Tested campaign: an integrated approach to sexually transmitted disease prevention communication. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2014;41(3):151–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.McFarlane M, Brookmeyer K, Friedman A, Habel M, Kachur R, Hogben M. GYT: Get Yourself Tested Campaign Awareness: Associations With Sexually Transmitted Disease/HIV Testing and Communication Behaviors Among Youth. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2015;42(11):619–24. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Taylor MM, Frasure-Williams J, Burnett P, Park IU. Interventions to Improve Sexually Transmitted Disease Screening in Clinic-Based Settings. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43(2 Suppl 1):S28–41. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, et al. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bergman J, Gratrix J, Plitt S, et al. Feasibility and Field Performance of a Simultaneous Syphilis and HIV Point-of-Care Test Based Screening Strategy in at Risk Populations in Edmonton, Canada. AIDS Res Treat. 2013;2013:819593. doi: 10.1155/2013/819593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wickersham JA, Gibson BA, Bazazi AR, et al. Prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Cisgender and Transgender Women Sex Workers in Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Results From a Respondent-Driven Sampling Study. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2017;44(11):663–70. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Chen XS, Yin YP, Shen C, et al. Rapid syphilis testing uptake for female sex workers at sex venues in Southern China: implications for expanding syphilis screening. PloS one. 2012;7(12):e52579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Klausner JD, Levine DK, Kent CK. Internet-based site-specific interventions for syphilis prevention among gay and bisexual men. AIDS care. 2004;16(8):964–70. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wei C, Herrick A, Raymond HF, Anglemyer A, Gerbase A, Noar SM. Social marketing interventions to increase HIV/STI testing uptake among men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011;(9):CD009337. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ramanathan S, Deshpande S, Gautam A, et al. Increase in condom use and decline in prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among high-risk men who have sex with men and transgender persons in Maharashtra, India: Avahan, the India AIDS Initiative. BMC public health. 2014;14:784. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Chacko MR, Cromer BA, Phillips SA, Glasser D. Failure of a lottery incentive to increase compliance with return visit for test-of-cure culture for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1987;14(2):75–8. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198704000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Gollub EL, French P, Loundou A, Latka M, Rogers C, Stein Z. A randomized trial of hierarchical counseling in a short, clinic-based intervention to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted diseases in women. AIDS. 2000;14(9):1249–55. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.McNulty CA, Hogan AH, Ricketts EJ, et al. Increasing chlamydia screening tests in general practice: a modified Zelen prospective Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial evaluating a complex intervention based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(3):188–94. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rudd S, Gemelas J, Reilley B, Leston J, Tulloch S. Integrating clinical decision support to increase HIV and chlamydia screening. Preventive medicine. 2013;57(6):908–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bilardi JE, Fairley CK, Temple-Smith MJ, et al. Incentive payments to general practitioners aimed at increasing opportunistic testing of young women for chlamydia: a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC public health. 2010;10:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Malotte CK, Ledsky R, Hogben M, et al. Comparison of methods to increase repeat testing in persons treated for gonorrhea and/or chlamydia at public sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2004;31(11):637–42. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000143083.38684.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Tucker JD, Hawkes SJ, Yin YP, Peeling RW, Cohen MS, Chen XS. Scaling up syphilis testing in China: implementation beyond the clinic. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88(6):452–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.070326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Tang EC, Segura ER, Clark JL, Sanchez J, Lama JR. The syphilis care cascade: tracking the course of care after screening positive among men and transgender women who have sex with men in Lima, Peru. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008552. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zou H, Zhang L, Chow EP, Tang W, Wang Z. Testing for HIV/STIs in China: Challenges, Opportunities, and Innovations. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2545840. doi: 10.1155/2017/2545840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]