Abstract

In this Letter, a detailed analysis of 30 4-aminoquinoline-based compounds with regard to their potential as antileishmanial drugs has been carried out. Ten compounds demonstrated IC50 < 1 μM against promastigote stages of L. infantum and L. tropica, and five compounds showed IC50 < 1 μM against intramacrophage L. infantum amastigotes. Two compounds showed dose-dependent enhancement of NO and ROS production by bone marrow-derived macrophages and remarkable reduction of parasite load in vivo, with advantage of being short-term and orally active. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of 4-amino-7-chloroquinoline derivatives active in Leishmania infantum infected mice.

Keywords: Leishmania infantum, promastigote, amastigote, mice model, aminoquinoline

Leishmaniasis is a neglected parasitic disease transmitted by more than 90 sand fly species. The disease may occur in humans and animals, including dogs and rodents. Human infection is caused by about 21 of the 30 species of Leishmania parasites that infect mammals.1,2 Currently, 2 million people are infected every year, and more than 350 million people are at risk mostly in tropical and subtropical areas.3 The life cycle of Leishmania parasite includes sand fly and vertebrate host stages. After an infected sand fly deposits metacyclic promastigotes into the host’s skin during blood feeding, they are phagocytized by macrophages and then transformed into aflagellated amastigotes. In macrophages, amastigotes multiply, and after being released, they infect new macrophages. The sand fly ingests infected macrophages during a blood meal, and the life cycle continues within the sand fly gut.2 Treatment of leishmaniasis varies and adapts to the severity of the disease and species of the parasite.1 Antileishmanial drugs that are presently in use are pentavalent antimonials, amphotericin B, pentamidine, miltefosine, and others, with AmBisome and sodium stibogluconate–paromomycin combination therapy being the first choice for fighting leishmania infection (Chart 1).3,4 All current therapies present serious side effects, including toxicity, and for some of them, resistance development is emerging.5 In addition, the vaccine for preventing human leishmaniasis, which could have an immense influence on suppression of the disease, is still not available.6 Thus, the development of potent small molecule inhibitors of Leishmania parasites and clinical trials of new drugs are the priorities (DNDI-0690, Chart 1).4,7

Chart 1. Examples of Current Antileishmanial Medicines and New Potent Drug Candidate.

Beside their antimalarial activity, derivatives of 4-aminoquinoline also demonstrated antibacterial, antifungal, antitumor, and antileishmanial activity.8 4-Amino-7-chloroquinoline analogues and their Pt(II) complexes were shown to be active against promastigotes of different Leishmania species.8 Another study investigated the in vitro activity of a series of 4-amino-7-chloroquinolines conjugated to sulfonamide, hydrazide, and hydrazine against L. amazonensis promastigotes and amastigotes, revealing the ability of these compounds to induce depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential in promastigotes and infected macrophages in vitro.9,10 Steroid linked aminoquinolines also proved to have significant activity against both promastigote and amastigote forms of L. majorin vitro.11

Here, we report on the synthesis and antileishmanial potential of novel 4-aminoquinoline derivatives and some aminoquinoline-based drugs previously published by our group (Chart 2).12−16

Chart 2. Structures of Examined Compounds.

The introduction of different substituents at C(3) of quinoline moiety was of interest since it is expected to influence the electronic density to a substantial extent. Sontochin-like compounds, as well as our previously published aminoquinoline derivatives with fluorine atom at the same position proved to be of significant antiplasmodial potential.12 Here, we explore the effect of nitro and amino substituents on antileishmanial activity (Scheme 1). Nitro substituent in 31(12) enabled nucleophilic substitution under mild conditions,17 resulting in compounds 1 and 2 in reasonably good yield. Reduction of nitro group to amino using tin(II)-chloride12 afforded compounds 3 and 4.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Substituted Chloroquine-Like Compounds 1–4.

Reagents and conditions: (i) amine, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to reflux; (ii) SnCl2, EtOH.

Aminoquinolines with adamantane carrier were synthesized as presented in Scheme 2. Commercially available 1-adamantanemethanol was transformed into mono-Boc protected amine 32 in moderate yield using the procedure we established earlier.12 Removal of the protecting group under standard conditions gave amine 33 in good yield. Dichloride 31 was submitted to nucleophilic substitution with amine 33 affording aminoquinoline 5 in good yield. The nitro group in 5 was further reduced to amine 6 using SnCl2.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Adamantane Derivatives 5 and 6.

Reagents and conditions: (i) (1) PCC, DCM, (2) tert-butyl (3-aminopropyl)carbamate, MeOH/DCM, AcOHglac, (3) NaBH4; (ii) TFA, DCM; (iii) 31, DCM, 0 °C to reflux; (iv) SnCl2, EtOH.

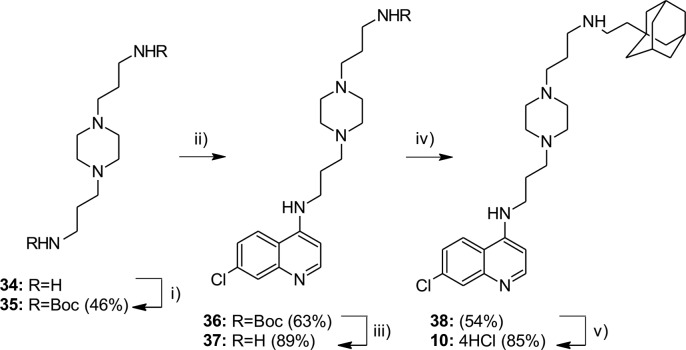

Compound 10 with piperazine moiety in linker was synthesized in several reaction steps, starting from commercially available 3,3′-piperazine-1,4-diyldipropan-1-amine 34 (Scheme 3). After protection of amino groups and nucleophilic substitution with 4,7-dichloroquinoline, compound 36 was obtained in moderate yield. Removal of protecting group under standard conditions gave amine 37 in high yield. Reductive amination of the obtained amine with adamantane-1-acetaldehyde furnished the compound 38. Compound 10 was obtained as HCl salt of amine 38 (confirmed by elemental analysis).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Compound 10.

Reagents and conditions: (i) Boc2O, DCM, r.t.; (ii) 4,7-dichloroquinoline, 80 °C, 1 h; 125 °C, 6–8 h; (iii) TFA/DCM (v/v 1:10), r.t., 24 h; 2.5 M NaOH; (iv) aldehyde, NaBH(OAc)3, DCM, r.t., 24 h; (v) MeOH/HCl.

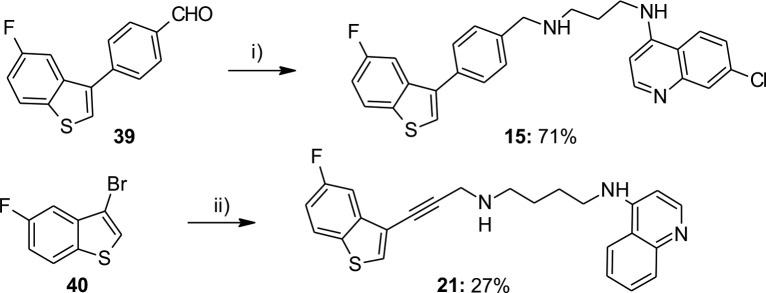

Benzothiophene derivative 15 was obtained by reductive amination starting from aldehyde 39(13) in good yield. Compound 21 was obtained in rather low yield by Sonogashira coupling reaction of 40(13) and N-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)-N′-(quinolin-4-yl)butane-1,4-diamine 41 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Novel Benzothiophene Derivatives 15 and 21.

Reagents and conditions: (i) (1) AQ3, AcOHglac, MeOH/DCM, (2) NaBH4; (ii) 41, PdCl2(PPh3)2, PPh3, CuI, Et2NH, DMF, MW, 120 °C, 25 min.

Reduction of the quinoline core was designed in order to explore the effect of resulting deviation from planarity on inhibition of Leishmania proliferation (Scheme 5). Compound 42, synthesized according to the procedure described in the literature,18 was transformed into 43 in acceptable yield. Selective reduction of benzene core of quinoline and hydrogenolysis of chlorine were performed by hydrogenation method using platinum(IV) oxide in acetic acid as solvent in the presence of perchloric acid. Deacetylation of compound 43 in 2 M HCl gave compound 44 in high yield. Using Sandmeyer reaction conditions (NaNO2, AcOH, HCl, CuCl), compound 44 was transformed into 45.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Tetrahydroquinoline Core.

Reagents and conditions: (i) PtO2, H2, AcOH, HClO4; (ii) 2 M HCl, 70 °C; (iii) (1) AcOHglac, 28% HCl, NaNO2(aq), 0 °C, (2) CuCl, 28% HCl, 0 °C to r.t.

Syntheses of thiophene-based tetrahydroquinoline compounds are presented on Scheme 6. Compound 45 was submitted to Buchwald–Hartwig amination affording the amines 22, 23, and 46 in low to moderate yield. Compound 46 with eight methylene groups in the linker was subjected to reductive amination with 4-[5-(4-formylphenyl)thiophen-2-yl]benzonitrile13 to obtain 24. Methylation of secondary nitrogen using 37% formaldehyde gave compound 25 in high yield.

Scheme 6. Synthesis of Compounds 22–25.

Reagents and conditions: (i) amine, Pd(OAc)2, SPhos, K3PO4, dioxane, 85 °C, 24h; (ii) for compound 46, (1) 4-[5-(4-formylphenyl)thiophen-2-yl]benzonitrile, AcOHglac, MeOH/DCM, (2) NaBH4; (iii) 37% HCHO, ZnCl2, NaBH3CN, MeOH.

The syntheses of other compounds are presented in our previous papers.12−16 Full details of synthetic procedures, NMR spectra, and HPLC purities are given in the Supporting Information.

Thirty compounds presented on Chart 2 were first examined for their activity against L. infantum and L. tropica promastigote stage using standard MTT assay (Table 1, Table S1). Ten compounds showed IC50 values of the same order of magnitude as amphotericin B (IC50 < 1 μM), which was used as a positive control. C(3)-Substituted chloroquine-like compounds (1–4) displayed poor antileishmanial activity against both promastigote species. However, hybrids of such compounds with adamantane carrier resulted in more active derivatives 5 and 6. Among adamantane derivatives without substituent at C(3), compound 7 showed clear improvement of potency. The most potent compound was 10, with a piperazine moiety in the linker.

Table 1. In Vitro Activities against L. infantum and L. tropica Promastigotes and Cytotoxicity against THP-1 Human Cellsa.

| compd | L. infantum IC50 (μM)b | L. tropica IC50 (μM)b | THP-1 IC50 (μM)c | SI (THP/L.i.)d | SI (THP L.t.)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.67 | 2.77 | 23.66 | 2.7 | 8.5 |

| 2 | 6.49 | 2.96 | >109.6 | >16.9 | >37.0 |

| 3 | 16.60 | 9.35 | >65.2 | >3.9 | >7.0 |

| 4 | 16.60 | 6.63 | >59.7 | >3.6 | >9.0 |

| 5 | 1.91 | 2.24 | 12.59 | 6.6 | 5.6 |

| 6d | 1.77 | 1.30 | 6.39 | 3.6 | 4.9 |

| 7 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 1.81 | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| 8 | 2.46 | 1.84 | 3.29 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| 9 | 2.40 | 2.35 | 4.90 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| 10 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| 11 | 1.14 | 1.31 | 2.96 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| 12 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 3.76 | 5.8 | 5.5 |

| 13 | 1.23 | 1.24 | 4.25 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| 14 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 1.91 | 3.8 | 3.8 |

| 15 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 4.73 | 9.9 | 10.9 |

| 16 | 1.03 | 0.81 | 2.31 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| 17 | 1.02 | 0.85 | 4.28 | 4.2 | 5.0 |

| 18 | 1.24 | 1.02 | 2.35 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| 19 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 2.44 | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| 20 | 1.55 | 1.22 | 2.79 | 1.8 | 2.3 |

| 21 | 1.02 | 1.37 | 7.11 | 7.0 | 5.2 |

| 22 | >76.5 | >76.5 | >76.5 | >1 | >1 |

| 23 | >69.1 | >69.1 | >69.1 | >1 | >1 |

| 24 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 2.31 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| 25 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 3.68 | 4.4 | 4.6 |

| 26 | 2.30 | 1.94 | 5.01 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| 27 | 1.22 | 1.54 | 2.80 | 2.3 | 1.8 |

| 28 | 5.42 | 7.11 | 8.10 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| 29 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 1.38 | 4.0 | 4.6 |

| 30 | 0.80 | 1.06 | 3.85 | 4.8 | 3.6 |

| controle | 0.13 | 0.14 | >10.8 | >83.1 | >77.1 |

Antileishmanial IC50 values against promastigote stages (μM), MTT assay.

All in vitro experiments were performed in duplicate, mean values are given.

Cytotoxicity against differentiated THP-1, human monocytic cell line derived from an acute monocytic leukemia patient.

Selectivity index.

Control drug: amphotericin B.

Benzothiophene compounds 15 and 17 with a chlorine atom at the C(7) position of the quinoline moiety were more potent than their des-chloro analogues 16 and 18, suggesting that chlorine atom would be important for the activity. Replacing the phenyl group with a C≡C bond did not produce any significant effect on the activity (18 vs 21).

While chloroquine-like compounds, tetrahydroquinolines 22 and 23, were completely inactive, hybrids with thiophene carrier 24 and 25 showed >100-fold increase in activity. Among other thiophenes, compound 29, with eight methylene groups between two nitrogens, demonstrated the highest potency against both Leishmania promastigote species. All compounds were also checked for cytotoxicity against differentiated THP-1 cells. For both species, moderate selectivity indices were obtained (SITHP–1/L.i. = 1.3–9.9; SITHP-1/L.t. = 1.1–10.9, Table 1).

All compounds were tested against intramacrophage amastigotes of L. infantum at 0.5 μM, nontoxic concentration on human cells (Table S2). Compounds that showed more than 25% inhibition were tested in dose–response experiments, and IC50 were calculated. Five compounds showed IC50 less than 1 μM. Among them, compounds 10, 15, and 18 were the most active, while compound 15 was the least toxic with good selectivity index (Table 2).

Table 2. In Vitro Activities against Intramacrophage L. infantum Amastigotes.

| compd | in vitro antiamastigote activity at 0.5 μMa | in vitro antiamastigote activity IC50 (μM)b | THP-1 IC50 (μM)c | SI (THP/IPT)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 29.6 | 1.91 | 3.29 | 1.72 |

| 10 | 72.2 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 3.22 |

| 11 | 26.4 | 1.85 | 2.96 | 1.60 |

| 13 | 38.9 | 1.29 | 4.25 | 3.29 |

| 14 | 26.4 | >1 | 1.91 | <1.91 |

| 15 | 47.6 | 0.58 | 4.73 | 8.15 |

| 18 | 42.7 | 0.65 | 2.35 | 3.61 |

| 19 | 36.9 | 0.73 | 2.44 | 3.34 |

| 20 | 42.2 | 0.79 | 2.79 | 3.51 |

| 24 | 29.6 | >1 | 2.31 | <2.31 |

| controle | 95.5 | 0.21 | >10.8 | >51.4 |

Mean value of two or three experiments.

Mean value of two experiments.

Cytotoxicity against differentiated THP-1, human monocytic cell line derived from an acute monocytic leukemia patient.

Selectivity index (IC50 against THP-1/IC50 against intracellular amastigotes).

Control drug: amphotericin B.

Three compounds with good antileishmanial potential (10, 15, and 18) were subjected to in vivo tolerability evaluation in a mice model. All compounds were tested orally at 300 mg/kg (single dose) as a suspension in 0.1%Tween/0.5% HEC in water. Compound 15 was also tested at a lower dose, 50 mg/kg, by subcutaneous route of administration (in sunflower oil). Compound 18 showed toxic effects when given orally with 3/5 mice alive at the end of the experiment, while compounds 10 and 15 given either p.o. or s.c. proved to be tolerable since all mice survived 30 days after administration and showed normal appearance and behavior.

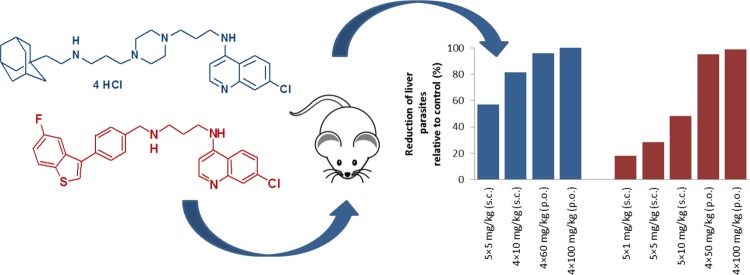

Compounds 10 and 15 were further evaluated for reduction of liver parasite load in a mouse model of visceral leishmaniasis (Balb/c mice infected intravenously with L. infantum amastigotes). Results presented in Figure 1 are given as % of reduction relative to control (untreated infected mice, Tables S3 and S4). Compound 15 was tested per os at two different doses 50 mg/kg × 4 days and 100 mg/kg × 4 days and showed significant reduction of parasites in the liver, 95% and 99%, respectively. Compound 10 was also tested per os at 60 mg/kg × 4 days and 100 mg/kg × 4 days. At lower applied dose, it reduced parasite load by 96% compared to control. Although at higher dose complete clearance was achieved, it showed signs of toxicity since one mouse died on day 10 and one mouse died on day 12. Both compounds were also subjected to s.c. administration at lower doses (Figure 1). Compound 10 administered at dose 10 mg/kg × 4 days reduced parasite load by 81%. At 5 mg/kg × 5 days and lower, both compounds exhibited poorer activities (57% and 18–48% for 10 and 15, respectively). However, these results are extremely important, giving us the essential information about dose-dependent behavior of selected 4-aminoquinolines.

Figure 1.

Reduction of parasite load in a mouse model by compounds 10 and 15.

In order to investigate the putative mechanism of action (MOA),9 we examined the production of nitric oxide and ROS by IFNγ primed murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) treated with 10 or 15. Experiments were performed at several nontoxic BMDM concentrations. Nontoxic concentrations were determined by MTT assay (data not shown). The concentration of nitrite and ROS was determined using Griess reagent and H2DCFDA, respectively. Results revealed that compounds 10 and 15 increased the production of nitric oxide by IFNγ-primed macrophages only at the highest dose used (Figure S1). Both compounds induced a persistent increase of ROS at all the doses tested (Figure S2).

Currently, several noteworthy in vivo studies have been published.19−21 Nitroimidazo-oxazole compound DNDI-VL-2098 previously identified as a favorable candidate did not proceed to the clinical study.20,22 However, its oxazine derivative DNDI-0690 was very recently recognized as a new promising candidate for a Phase I trial for VL.4,7 In the last ten years, only a few 4-amino- and 2-alkenylquinolines with modest activity against Leishmania parasites in vivo were also identified.23−25 8-Aminoquinoline derivative sitamaquine appeared to be orally active against visceral leishmaniasis and is presently under clinical investigation.26

Here, we identified two 4-amino-7-chloroquinoline compounds bearing benzothiophene or adamantane moieties as potent antileishmanial candidates with significant in vivo efficacy. The importance of this work lies in discovery of highly active short-term compounds, tolerable in mice, being the first example of a 4-amino-7-chloroquinoline active in L. infantum mice model of visceral leishmaniasis. Although a certain dose-dependent enhancement of NO and ROS production (which can contribute to the amastigotes killing) was observed in the presence of 10 and 15, MOA still remains unclear. Further studies will be focused on discovering a specific target in order to elucidate the mechanism of action. Based on compounds’ tolerability in mice model and noteworthy in vivo activity, future efforts will be focused on improvement of pharmacokinetic profile and enhancement of the antileishmanial activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Olgica Djurković-Djaković and MSc Jelena Srbljanović (Institute for Medical Research, University of Belgrade) for performing in vivo toxicity studies and Loredana Cavicchini for assistance in culturing leishmania in vitro. We also thank Prof. Donatella Taramelli (Dipartimento di Scienze Farmacologiche e Biomolecolari, University of Milan) for helpful discussion, and COST Action CM1307 for support.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- BMDM

murine bone marrow-derived macrophages

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- Tween 80

Polysorbate 80

- HEC

hydroxyethyl cellulose

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- MOA

mechanism of action

- AQ3

N-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)propane-1,3-diamine.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00053.

Full details of synthetic procedures, biological assays, procedures for the determination of the HPLC purity, in vitro activities on promastigote stages, in vitro activities against intramacrophages L. infantum amastigotes, in vivo antileishmanial activity, nitric oxide and ROS production; NMR spectra and HPLC purity spectra of all tested compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

B.Š. and N.B. designed the research. The manuscript was written by J.K. with contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technological Development of Serbia (Grant 172008), Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Executive Programme of Scientific and Technological Cooperation between the Italian Republic and the Republic of Serbia for the years 2016–2018, and by “Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (PRIN) Project: 20154JRJPP_004”.

The study followed the International Guiding Principles for biomedical research involving animals (European Directive 2010/63/UE), and it was reviewed by a local Ethics Committees. The study was approved by the Veterinary Directorate at the Ministry of Agriculture and Environmental Protection of Serbia (decision no. 323–07–02444/2014–05/1) and by the Directorate of Animal Health and Veterinary Drugs at the Ministry of Health of Italy (authorization no. 120/2015-PR).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Leishmaniasis Fact Sheet N°375, February 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs375/en/ (accessed October 16, 2017).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Parasites - Leishmaniasis, January 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/ (accessed October 16, 2017).

- WHO Technical Report Series no. 949. Report of a Meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases, Geneva, 22–26 March 2010. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/resources/who_trs_949/en/ (accessed October 16, 2017).

- DNDi Portfolio December 2017. https://www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/portfolio/ (accessed March 22, 2018).

- Sangshetti J. N.; Kalam Khan F. A.; Kulkarni A. A.; Arote R.; Patil R. H. Antileishmanial drug discovery: comprehensive review of the last 10 years. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 32376–32415. 10.1039/C5RA02669E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie P. M.; Beaumier C. M.; Strych U.; Hayward T.; Hotez P. J.; Bottazzi M. E. Status of Vaccine Research and Development of Vaccines for Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2992–2995. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A. M.; O’Connor P. D.; Marshall A. J.; Yardley V.; Maes L.; Gupta S.; Launay D.; Braillard S.; Chatelain E.; Franzblau S. G.; Wan B.; Wang Y.; Ma Z.; Cooper C. B.; Denny W. A. 7-Substituted 2-Nitro-5,6-dihydroimidazo[2,1-b][1,3]oxazines: Novel Antitubercular Agents Lead to a New Preclinical Candidate for Visceral Leishmaniasis. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 4212–4233. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo A. M. L.; Silva F. M. C.; Machado P. A.; Fontes A. P. S.; Pavan F. R.; Leite C. Q. F.; Leite S. R.; Coimbra E. S.; Da Silva A. D. Synthesis of 4-Aminoquinoline Analogues and Their Platinum(II) Complexes as New Antileishmanial and Antitubercular agents. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2011, 65, 204–209. and refs therein 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinarelli L. M. R.; Dias R. M. P.; Souza I. O.; Lima W. P.; Gameiro J.; da Silva A. D.; Coimbra E. S. 4-Aminoquinoline Derivatives as Potential Antileishmanial Agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015, 86, 704–714. 10.1111/cbdd.12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares R. R.; Antinarelli L. M. R.; Souza I. O.; Lopes F. V.; Scopel K. K. G.; Coimbra E. S.; da Silva A. D.; Abramo C. In Vivo Antimalarial and In Vitro Antileishmanial Activity of 4- Aminoquinoline Derivatives Hybridized to Isoniazid or Sulfa or Hydrazine Groups. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery 2017, 14, 597–604. 10.2174/1570180813666160927113743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antinarelli L. M. R.; Carmo A. M. L.; Pavan F. R.; Leite C. Q. F.; Da Silva A. D.; Coimbra E. S.; Salunke D. B. Increase of Leishmanicidal and Tubercular Activities Using Steroids Linked to Aminoquinoline. Org. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 2, 16. 10.1186/2191-2858-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzić N.; Konstantinović J.; Tot M.; Burojević J.; Djurković-Djaković O.; Srbljanović J.; Štajner T.; Verbić T.; Zlatović M.; Machado M.; Albuquerque I. S.; Prudêncio M.; Sciotti R. J.; Pecic S.; D’Alessandro S.; Taramelli D.; Šolaja B. A. Reinvestigating Old Pharmacophores: Are 4-Aminoquinolines and Tetraoxanes Potential Two-Stage Antimalarials?. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 264–281. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinović J.; Videnović M.; Srbljanović J.; Djurković-Djaković O.; Bogojević K.; Sciotti R.; Šolaja B. Antimalarials With Benzothiophene Moieties as Aminoquinoline Partners. Molecules 2017, 22, 343. 10.3390/molecules22030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinović J.; Kiris E.; Kota K.; Kugelman-Tonos J.; Videnović M.; Cazares L. H.; Terzić N.; Verbić T. Ž.; Andjelković B.; Duplantier A. J.; Bavari S.; Šolaja B. A. New Steroidal 4-Aminoquinolines Antagonize Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype A in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Motor Neurons in Post-intoxication Model. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 1595–1608. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marković O. S.; Cvijetić I. N.; Zlatović M. V.; Opsenica I. M.; Konstantinović J. M.; Terzić Jovanović N. V.; Šolaja B. A.; Verbić T. Ž. Human Serum Albumin Binding of Certain Antimalarials. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2018, 192, 128–139. 10.1016/j.saa.2017.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šolaja B. A.; Opsenica D.; Smith K. S.; Milhous W. K.; Terzic N.; Opsenica I.; Burnett J. C.; Nuss J.; Gussio R.; Bavari S. Novel 4-Aminoquinolines Active against Chloroquine-Resistant and Sensitive P. falciparum Strains that also Inhibit Botulinum Serotype A. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4388–4391. 10.1021/jm800737y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerster J. F.; Lindstrom K. J.; Miller R. L.; Tomai M. A.; Birmachu W.; Bomersine S. N.; Gibson S. J.; Imbertson L. M.; Jacobson J. R.; Knafla R. T.; Maye P. V.; Nikolaides N.; Oneyemi F. Y.; Parkhurst G. J.; Pecore S. E.; Reiter M. J.; Scribner L. S.; Testerman T. L.; Thompson N. J.; Wagner T. L.; Weeks C. E.; Andre J.-D.; Lagain D.; Bastard Y.; Lupu M. Synthesis and Structure–Activity-Relationships of 1H-Imidazo[4,5-c]quinolines That Induce Interferon Production. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3481–3491. 10.1021/jm049211v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotchenko V.; Sathunuru R.; Gerena L.; Caridha D.; Li Q.; Kreishman-Deitrick M.; Smith P. L.; Lin A. J. Antimalarial Activity of 4-Amidinoquinoline and 10- Amidinobenzonaphthyridine Derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3411–3431. 10.1021/jm501809x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dea-Ayuela M. A.; Castillo E.; Gonzalez-Alvarez M.; Vega C.; Rolón M.; Bolás-Fernández F.; Borrás J.; González-Rosende M. E. Vivo and in Vitro Anti-leishmanial Activities of 4-Nitro-N-pyrimidin and N-Pyrazin-2-ylbenzenesulfonamides, and N2-(4-Nitrophenyl)-N1-propylglycinamide. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 7449–7456. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S.; Yardley V.; Vishwakarma P.; Shivahare R.; Sharma B.; Launay D.; Martin D.; Puri S. K. Nitroimidazo-oxazole Compound DNDI-VL-2098: An Orally Effective Preclinical Drug Candidate for the Treatment of Visceral Leishmaniasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 518–527. 10.1093/jac/dku422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiana-Roselló C.; Bilbao-Ramos P.; Dea-Ayuela M. A.; Rolón M.; Vega C.; Bolás-Fernández F.; García-España E.; Alfonso J.; Coronel C.; González-Rosende M. E. In Vitro and In Vivo Antileishmanial and Trypanocidal Studies of New N-Benzene- and N-Naphthalenesulfonamide Derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 8984–8998. 10.1021/jm4006127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VL-2098. https://www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/portfolio/completed-projects/vl-2098/ (accessed March 22, 2018).

- Nakayama H.; Desrivot J.; Bories C.; Franck X.; Figadère B.; Hocquemiller R.; Fournet A.; Loiseau P. M. In Vitro and In Vivo Antileishmanial Efficacy of a New Nitrilquinoline against Leishmania donovani. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2007, 61, 186–188. 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath V. S.; Pinjari J.; Dere R. T.; Verma A.; Vishwakarma P.; Shivahare R.; Moger M.; Kumar Goud P. S.; Ramanathan V.; Bose P.; Rao M. V.; Gupta S.; Puri S. K.; Launay D.; Martin D. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 2-Substituted Quinolines as Potential Antileishmanial Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 69, 527–536. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande S.; Shivahare R.; Debnath U.; Sane S. A.; Gupta S.; Katti S. B. Synthesis and Bio-evaluation of 7-trifluromethyl Substituted 4-aminoquinoline Derivatives as Antileishmanial Agents. Nat. Prod. J. 2017, 7, 137–143. 10.2174/2210315507666161206123513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau P. M.; Cojean S.; Schrével J. Sitamaquine as a Putative Antileishmanial Drug Candidate: From the Mechanism of Action to the Risk of Drug Resistance. Parasite 2011, 18, 115–119. 10.1051/parasite/2011182115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.