Abstract

Cancer incidence substantially increases with ageing in both men and women, although the reason for this increase is unknown. In this Series paper, we propose that age-associated changes in gut commensal microbes, otherwise known as the microbiota, facilitate cancer development and growth by compromising immune fitness. Ageing is associated with a reduction in the beneficial commensal microbes, which control the expansion of pathogenic commensals and maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier through the production of mucus and lipid metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids. Expansion of gut dysbiosis and leakage of microbial products contributes to the chronic proinflammatory state (inflammaging), which negatively affects the immune system and impairs the removal of mutant and senescent cells, thereby enabling tumour outgrowth. Studies in animal models and the importance of commensals in cancer immunotherapy suggest that this status can be reversible. Thus, interventions that alter the composition of the gut microbiota might reduce inflammaging and rejuvenate immune functions to provide anticancer benefits in frail elderly people.

Introduction

Ageing is a major risk factor for the development of cancer and many other chronic diseases. Combined with an increasing ageing population, changing global morbidity patterns are expected to change. In the USA alone, the elderly population (≥65 years old) is projected to reach 72 million by 2030, and to account for 61–70% of newly diagnosed cancers,1–3 with the percentage of centenarians to increase even more rapidly. Although cardiovascular morbidity and mortality have been steadily declining since 2000, the incidence of cancer remains stable, and cancer is a leading cause of death in middle-aged and elderly people.3 If substantial changes in our ability to prevent cancer and reduce cancer mortality are not made, it is predicted that cancer will become the main cause of reduced life expectancy in the elderly population. A 2017 analysis of 17 different human cancer types in 69 countries showed that two-thirds of cancer risk is caused by errors in DNA replication,4 which is probably associated with progressive genomic instability and accumulation of somatic mutations associated with the ageing process. However, increased mutational rates, especially in oncogenes, do not necessarily lead to the clinical presentation of cancer because the activation of TP53, p21, p16, and other genes induce growth arrest and senescence of transforming cells to be subsequently eliminated by innate immune and adaptive immune cells.5 Senescence is also induced by T helper-type 1 cytokines (interferon γ and tumour necrosis factor [TNF]α), which inhibit tumour angiogenesis and activate antitumour cytolytic CD8 T cells, natural killer cells, and M1 macrophages.5 Upon uptake and processing by dendritic cells, mutation-generated neoantigens induce antitumour helper CD4 and cytolytic CD8 T cells6 that, according to immune surveillance theory7 and its recent modification (the immunoediting concept8), eliminate mutant tumour cells and trigger tumour dormancy that consequently shapes the character and fate of the tumour. The outcome of immunoediting (ie, whether tumours escape immune surveillance or stay dormant) is also determined by the degree of immunosenescence8—a mild, chronic proinflammatory state (defined as inflammaging), which is often accompanied by less effective immune activation during infection and other immunogenic stimulation. Epidemiological studies have often shown that a mild and chronic proinflammatory state predicts cancer and many age-related diseases.9 Immunosenescence dysregulates and impairs function of innate and adaptive immune cells by affecting their differentiation, survival, migration, autophagy, proteostasis, and mitochondrial activity. The age-related loss of naive T and B cells, dysfunction of dendritic cells, and accumulation of immunoregulatory cells—eg, myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells—impair immune responses to neoantigens, implying that mutating tumours that would be eliminated in younger individuals survive and progress in elderly individuals. In fact, premalignant senescent hepatocytes progress into hepatocellular carcinoma upon the loss of immunosurveillance in severe combined immunodeficiency or beige mice and in patients who are co-infected with hepatitis C virus and HIV.5 Thus, until the immune system is highly functional, the effect of the accumulation of somatic mutations can be buffered.

An emerging theory is inflammaging is caused by alterations of intestinal commensal microbes (gut microbiota or microbiome). The composition of gut microbiota is not static; it changes in response to diet, lifestyle, infection, activation of immune responses, and IgA produced by B cells. In human beings and rodents, gut microbiota substantially differ between young and elderly hosts (≥70 years old) and even between centenarians and frail elderly people with a history of cancer.10,11 Ageing-associated gut dysbiosis, such as the shift towards proinflammatory commensals and reduction of beneficial microbes, causes impairment and leakiness of the intestinal barrier.12 Subsequent leakage of microbial lipopolysaccharide and other microbial products upregulates interferons, TNFα, interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 in circulation, promoting a mild proinflammatory state that is highly prevalent in elderly people, and predicts the accelerated decline of fitness and health.13,14 Dysfunction of the immune system that is partly caused by dysbiosis also impairs the ability of myeloid cells to remove senescent, apoptotic, and malfunctioning cells,13 which could further fuel inflammaging, affect immune editing, and create an environment conducive to cancer. Data in the literature on the associations between the gut microbiome and health in rodents and in human beings, including the effects of the gut microbiome on the outcomes of cancer immunotherapy,15,16 suggest that the prevention or reduction of inflammation in elderly people might reduce cancer susceptibility. It is unclear whether inflammaging is sustained by chronic immunogenic stimulation or by an intrinsic dysregulation of the immune system. Regardless, studies that are focused on the reduction of inflammation will show whether such decreases in inflammation can actually reduce cancer risk and benefit the overall health of elderly people.

In this Series paper, we review the literature and our own research to investigate whether dysbiosis of the gut microbiota could be one of the mechanisms that cause an increased risk of cancer in the elderly. Although both local and systemic inflammation could affect cancer development and progression, in this Series paper, we focus on systemic inflammation on myeloid cells only because local inflammation in cancer has been covered in two excellent articles already.17,18

Gut microbiota and systemic inflammation

The gut is populated by trillions of bacteria, archaea, eukarya, and viruses, with four major microbial phyla (Firmicutes, Bacteroides, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria) accounting for 98% of the intestinal microbiota. The microbiome is a symbiotic ecosystem that regulates numerous aspects of the normal functions of the gut and immune system, including nutrient supply, absorption, and metabolism. It controls the expansion of pathogenic commensals and invasive microorganisms and maintains the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Germ-free mice have shown that impaired nutrient absorption dysregulates intestinal morphology, reduces differentiation and maturation of intestinal immune cells, intraepithelial lymphocytes, T-helper-type 17 cells, and regulatory T cells, as well as decreasing the production of antimicrobial peptides and IgA, and other isotype-switched immunoglobulins, and shifts responses towards T-helper-type 2 cytokines.19 Intestinal segmented filamentous bacteria, such as Candida albicans and Citrobacter rodentium, facilitate pathogen clearance by inducing T helper-type 17 cells in lamina propria and recruiting neutrophils and other immune cells, while members of the Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium strains control inflammation by inducing FoxP3-positive Treg differentiation and production of interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor β.20 Through the metabolism of fibres into large quantities of short-chain fatty acids and their conjugate bases (acetate, propionate, and butyrate),20 members of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla (such as cluster IV [Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia faecis] and cluster XIVa of Clostridium genus [Anaerostipes butyraticus]), Alistepes genus, or Akkermanisia muciniphila) provide an energy source for microbiota and colonocytes, support the intestinal integrity, and stimulate the inflammasome pathway in gut homeostasis (table).21 Short-chain fatty acids bind metabolite-sensing G-protein-coupled receptor (GPR)43 and GPR109A and inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from dendritic cells.22 Besides being an important energy source, butyrate controls the expansion of pathogenic commensals by inducing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-dependent β-oxidation metabolic pathway and oxygen consumption in colonocytes,23 where epithelial oxygen consumption stabilises hypoxia-inducible factor and, in turn, intestinal epithelial barrier protection.24 It also regulates inflammation by inhibiting histone deacetylases and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signalling25 and inducing FoxP3-positive Treg differentiation in the colon and lamina propria.26 F prausnitzii or A muciniphila provide propionate to upregulate the expression of epigenome modifying enzymes, such as histone deacetylases 3 and 5, and to affect the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism and adipocyte inflammation.27 As anti-inflammatory bacteria, F prausnitzii induce high concentrations of interleukin-10, inhibit antigen-specific interferon γ-positive T cells, and protect from gut dysbiosis and subsequent Crohn’s disease.28 A muciniphila downregulates expression of fasting-induced adipose factor (also known as angiopoietin-like protein 4) in ileal organoids in vitro.27 Its outer membrane protein Amuc_1100* stimulates TLR2 and improves the function of the gut barrier and metabolic endotoximia in high-fat diet-induced obese mice.29 A muciniphila also supports intestinal barrier integrity by restoring the mucus layer needed for adhesion and growth of short-chain fatty acid-producing commensals and Bifidobacterium animalis subspecies lactis that help to maintain colonic tight junctions. The mucus layer is restored through the induction of mucus secretion, which supports microbiota, and the production of polyamines that suppress colonic senescence.30 Polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine) scavenge reactive oxygen species, induce stress response genes, regulate nuclear factor κB activation, inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines from macrophages, and even prolong longevity in mice.30 Overall, the healthy immune environment is maintained by symbiotic relationships between seemingly redundant gut microbe species, of which A muciniphila appears to be the key commensal bacteria. Despite representing only 5% of the gut microbiota of healthy people, A muciniphila protects intestinal integrity, which prevents endotoximia and subsequent chronic inflammation. Therefore, a reduction in A muciniphila and other beneficial microbes leads to gut dysbiosis, disruption of the intestinal barrier, and subsequent leakage of microbes and their products, which causes local and systemic chronic immune activation and dysregulation of lipid metabolism, growth, and survival of cells. At least in mice, this reduction in A muciniphila is linked to inflammatory bowel disease, which is a precursor to colorectal cancer.31

Table.

Ageing-associated changes in gut microbiota and their metabolites

| Associated factor and metabolite | Function of produced factor | Change in ageing | Consequence for gut leakiness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial diversity* | Unknown | Unknown | Decreased | Unknown |

|

| ||||

| Firmicutes phylum | MAMPs and PAMPs | Possibly pathogenic | Increased | Possibly increased |

|

| ||||

| Ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes phyla | MAMPs and PAMPs | Possibly pathogenic | Increased | Possibly increased |

|

| ||||

| Alistepes genera | Unknown | Unknown | Increased | Possibly increased |

|

| ||||

| Oscillibacter genera | Unknown | Unknown | Increased | Possibly increased |

|

| ||||

| Eubacteriaceae family | Unknown | Unknown | Increased | Possibly increased |

|

| ||||

| Clostridium cluster IV | ||||

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | SCFAs | Affects metabolism and activity of immune cells | Decreased | Increased |

| Roseburia faecis | SCFAs (butyrate) | Affects metabolism and activity of immune cells | Decreased | Increased |

|

| ||||

| Clostridium cluster XIVa | ||||

| Anaerostipes butyraticus | SCFAs | Butyrate provides energy for gut commensals and colonocytes; histone deacetylase inhibitor; induces generation of colonic regulatory T cells; induces antimicrobial peptide production of colonocytes; prevents expansion of pathogenic commensals; inhibits toll-like receptor 4 signaling | Decreased | Increased |

| Ruminococcaceae | SCFAs (butyrate) | Butyrate provides energy for gut commensals and colonocytes; histone deacetylase inhibitor; induces generation of colonic regulatory T cells; induces antimicrobial peptide production of colonocytes; prevents expansion of pathogenic commensals; inhibits toll-like receptor 4 signalling | Decreased | Increased |

|

| ||||

| Christensenellaceae | SCFAs | ·· | Decreased | Possibly increased |

|

| ||||

| Verrucomicrobia phylum | Outer membrane protein | Possibly induces loss of Akkermansia | Decreased | Increased |

|

| ||||

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Amuc_1100* | Stimulates colonocyte toll-like receptor 2; induces mucus production; possibly supports growth of other commensals; produces immunoregulatory propionate; induces mucus production and thereby supports growth of other commensals, such as producers of SCFAs; improves metabolism and insulin sensitivity | Decreased | Increased |

|

| ||||

| Bifidobacterium animalis subspecies lactis | Polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine) | Scavenges reactive oxygen species; induces stress-response gene; regulates nuclear factor κB activation; inhibits production of pro-inflammatory cytokines from macrophages; prolongs longevity in mice | Possibly decreased | Possibly increased |

The composition of gut microbiota varies depending on anatomical location, diet, lifestyle, and ageing. To represent the caecum as an example of the greatest density of commensals essential for health, we only list faecal bacteria that changed in ageing in most reports. MAMPs=microbe-associated molecular pattern molecules.

PAMPs=pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules. SCFAs=short-chain fatty acids.

We defined bacterial diversity according to differentially abundant taxa in microbiota DNA sequencing.

Gut microbiota dysbiosis and cancer in ageing

The symbiotic relationship of gut microbiota depends on intrinsic and extrinsic factors, such as diet, antibiotics and ageing. The composition of different microbiota differ between elderly people who live at home and those who live in long-term care facilities.32 In general, as shown in two independent studies, one that focuses on Italian centenarians10 and the other on Chinese centenarians and nonagenarians,33 longevity is inversely associated with alpha diversity of faecal microbiota (ie, colonic microbial content) and is positively correlated with an abundance of short-chain fatty acid-producers, such as Clostridium cluster XIVa Ruminococcaceae, Akkeramansia, and Christensenellaceae.10,33 The loss of Lactobacillus and Faecalibacterium and the abundance of Oscillibacter and Alistipes genera and Eubacteriaceae family is associated with frailty in elderly people.34 Frail elderly people also have more proinflammatory Bacteroidetes commensals34 and fewer producers of benefical short-chain fatty acids and polyamines than do healthy elderly people.30,35 Unlike healthy centenarians, A muciniphila is scarce in frail elderly people and in healthy older mice (≥18 months), which instead have Alistipes genus bacteria.10,33,35 These changes also appear to be intrinsic to ageing; our group has observed similar inflammaging and gut dysbiosis and leakiness in mice and primates living in pathogen-free environments (Biragyn A, unpublished). Gut microbiota of ageing rodents has reduced beneficial A muciniphila, F prausnitzii, lactobacilli, and bifidobacteria and is enriched in clostridia, enerobacteria, streptococci, staphylococci, and yeast and facultative anaerobes (table, figure 1; Biragyn A, unpublished).36 The reduction of A muciniphila in patients with melanoma and epithelial tumours also impairs outcomes of programmed cell death protein-1-based immunotherapy.15,16

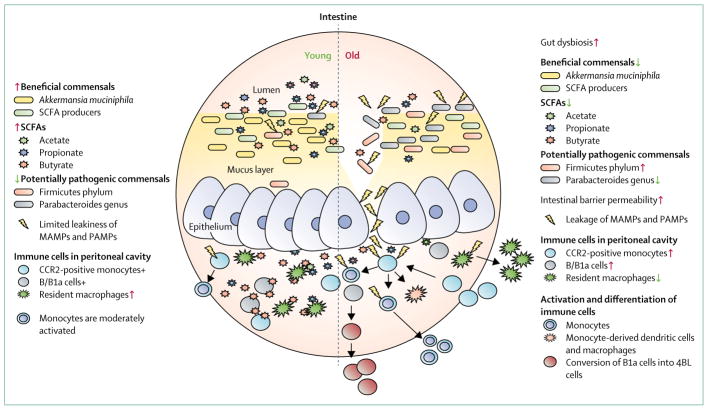

Figure 1. Inflammaging and age-associated gut dysbiosis.

Through their control of inflammation, commensals activate monocytes involved in homoeostasis and immune surveillance. Ageing changes the composition of gut commensals. For example, the number of beneficial bacteria are reduced, whereas pathogenic bacteria are increased. This change promotes a chain of inflammatory events that lead to chronic inflammation (inflammaging). SCFA=short-chain fatty acid. MAMPs=microbe-associated molecular patterns.

PAMPS=pathogen-associated molecular patterns. +=present. CCR2=C-C chemokine receptor type 2.

Diet is an important external factor that affects gut microbiota and qualitative aspects of diet have been associated with frailty. For example, evidence has shown that adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet reduces frailty in community-dwelling elderly people.37 Notably, a high intake of fat and animal protein, which is associated with low plant-based content34 and is characteristic of a western diet, is thought to be a major comorbidity risk factor for the development of various types of cancer, such as colorectal, ovarian, prostate, and endometrial cancer.38 In mice, obesity induced by a high fat diet reduces A muciniphila, butyrate, and producers of short-chain fatty acid, such as F prausnitzii in the gut,29 which is similar to our findings in old mice (Biragyn A, unpublished). The scarcity of these important controllers of potentially pathogenic commensals23 and protectors of the intestinal integrity24 explains the increased dysbiosis, impaired physiology and structure of the gastrointestinal tract, and leakage of inflammaging-inducing and tumorigenic bacterial products in ageing and in obesity (figure 2). As a result, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) induce inflammaging, such as the production of reactive oxygen species, TNF, interleukin-1β, interleukin-18, and interleukin-6, which promote cancer both locally and systemically.39 Gut microbes also produce deoxycholic acid in high-fat diet-induced obese mice, which enhances chemical carcinogen exposure-induced hepatocellular carcinoma by inducing senescent-associated secretory phenotype in hepatic stellate cells.40 Notably, this process is reversible because inhibition of this pathway and inflammaging in itself can reduce the risk of cancer and possibly benefit longevity. In a randomised trial of the role of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab in 10 061 patients with atherosclerosis, canakinumab not only substantially reduced inflammatory biomarkers in participants diagnosed with lung cancer, but also significantly decreased lung cancer mortality compared with the placebo group.41 Similarly, the lack of systemic inflammation appears to explain why germ-free rodents have fewer tumours and live longer than their conventional counterparts.42,43

Figure 2. Ageing gut dysbiosis and cancer.

In young hosts, beneficial gut microbiota activate immune cells to mediate proper cancer immune surveillance to eliminate malignant and impaired cells via senescence, phagocytosis, and cytolytic killing. However, gut dysbiosis in ageing induces chronic inflammation, which reduces immune fitness and provides a selective benefit to oncogene-expressing and malignant cells. Gut dysbiosis impairs the removal of senescent and dormant tumour cells by phagocytes, impairs the induction of tumour-specific cytolytic CD8 T cells by plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and enhances the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressive cells and regulatory T cells in cancer. By contrast, it can also slow growth of some tumours in ageing; for example, by utilising activated innate B1a cells (4BL cells) that induce antitumor cytolytic granzyme-positive CD8 T cells. Treg=Regulatory T cell.

Dysregulation of myeloid cells in ageing and the risk of cancer development

Inflammaging is characterised by the activation of multiple proinflammatory signalling pathways that sustain the chronic production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1α/β, interleukin-6, and TNFα,44 for example, from monocytes and macrophages.13,14 Although high concentrations of TNFα are proapoptotic and pronecrotic, chronic low doses of TNFα are tumorigenic.45 Thus, impaired interferon γ and TNF receptor 1 signalling in ageing, which disables the induction of angiostatic chemokines C-X-C motif ligand 9 (CXCL9) and CXCL10, antitumour cytolytic CD8 T cells, and cytotoxic M1 macrophages,5 can lead to the accumulation of senescent cells, angiogenesis, and consequent multistage carcinogenesis.46 High concentrations of TNFα reduce the fitness of haemopoietic stem cells in ageing bone marrow, providing a competitive advantage and selection of haemopoietic progenitor cells with oncogenic mutations to facilitate leukaemogenesis and acute myeloid leukaemia.47 Reduction of inflammation blocks this process in old mice (≥18 months), whereas chronic injections of lipopolysaccharide or TNFα enhance it.47

Role of MDSCs in cancer

High concentrations of TNFα, interleukin-6, and inter-leukin-1β and low concentrations of transforming growth factor β and interferons also skew haemopoiesis towards the myeloid lineage48,49 and expand MDSCs in frail elderly people with a history of cancer.50 An abundance of MDSCs is associated with poor prognosis in patients with cancer because they promote tumour-supporting inflammation and neoangiogenesis and regulate anti-tumour effector immune responses.51 MDSCs inhibit the activity of T cells and, more importantly, antitumour cytolytic CD8 T cells, by producing immunoregulatory factors, such as reactive nitrogen and oxygen species (nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, hydrogen peroxide, and peroxinitrite).51 Therefore, although young BXD12 mice (cross between C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice) are protected from subcutaneous challenged mammary TS/A adenocarcinoma, the tumour rapidly grows in old mice because of an ageing-associated expansion of MDSCs and consequent inhibition of antitumour cytolytic CD8 T cells.50 MDSCs also indirectly regulate immune responses by inducing the generation of FoxP3-positive regulatory T cells, which are significantly increased in ageing52 and, in turn, restrain tumour-induced expansion of MDSCs. This situation explains why the depletion of regulatory T cells only benefits young hosts with tumours, whereas it exacerbates B16-F10 melanoma growth in syngeneic old C57BL/6 mice because MDSCs are expanded further.52

Ageing neutrophils

Phenotypically, MDSCs consist of immature granulocytic cells (polymorphonuclear neutrophils-MDSCs, Ly6G+Ly6CInt/LowCD11b+ in mice and CD14− CD11b+ CD15+CD33+ in human beings) and monocytic cells (monocytes-MDSCs, Ly6CHiLy6G− CD11b+ in mice and CD14+CD11b+HLA-DRLow/− in human beings).51 Because of overlapping markers, it is difficult to discriminate these cells from polymorphonuclear neutrophils and monocytes, particularly in elderly hosts with dysregulated cells. In elderly people, neutrophils have inefficient chemotaxis (due to the constitutive activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase53), dysfunctional phagocytosis, killing of phagocytosed bacteria, and priming and activation of oxidative burst and proteases,13,54 and have defective release of neutrophil extracellular traps, although the amount released can be increased in response to microbial TLR ligands.55 The formation of neutrophil extracellular traps—eg, upon activation with CXCL8, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and transforming growth factor β from endothelial cells and tumour cells—promotes cancer progression and metastasis.56 Activation of TLR7 or TLR8 impairs phagocytosis and leads to furin-dependent proteolytic cleavage of FcgRIIA and induction of neutrophil extracellular trap formation, thereby impairing clearance of immune complexes and driving inflammation.57 Immune complexes and immunoglobulin depositions induce complement-mediated inflammatory microenvironment, which facilitates cancer emergence and progression. In a human papillomavirus type 16-induced spontaneous model of carcinogenesis,58 neutrophil extracellular traps act as carriers for transforming growth factor β to mediate the suppression of cellular immune responses.59

Monocytes

Monocytes consist of inflammatory (CCR2HiLy6C+ in mice and CCR2HiCD14+CD16− in human beings) and patrolling (CX3CR1Hi Ly6C− in mice and CX3CR1HiCD14dim/− CD16+ in human beings) subsets. In human beings, the two subsets are referred as classical (CD14HiHLA-DR+) and nonclassical (CD14dim/− CD16+HLA-DR+).60 In a steady state, monocytes provide important so-called housekeeping functions. Upon activation with healthy gut microbiota, CCR2-positive (possibly inflammatory) monocytes migrate into the brain and promote adult hippocampal neurogenesis.61 As such, adult hippocampal neurogenesis is impaired and brain microhaemorrhages are increased in germ-free mice, or upon treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics or depletion of CCR2-positive monocytes.61 Classical monocytes show the highest phagocytic capacity and, either by themselves or mostly after conversion into macrophages, they promote cancer growth and metastasis.62 By contrast, patrolling monocytes resolve inflammation and facilitate tissue maintenance by scavenging cellular debris and surveying the endothelium of the vasculature. They protect from lung metastasis by supporting cancer immunosurveillance.63 Peripheral blood of healthy people also contains a small amount of intermediate monocytes (CD14HiCD16+HLA-DR+).64 CD14Hi monocytes (inflammatory and intermediate) are phagocytic and produce high concentrations of reactive oxygen species, while CD16-positive monocytes predominantly produce proinflammatory cytokines.63 Nonclassical or patrolling monocytes respond to TLR agonists better than classical monocytes do.63 However, unlike the other two subsets, intermediate monocytes not only constitutively express TNFα but also produce it at significantly increased concentrations when inactivated with lipopolysaccharide.13 The increase in TNFα in old mice leads to upregulation of CCR2 and subsequent movement of immature Ly6C-positive monocytes from bone marrow into peripheral blood, thus explaining the accumulation of inflammatory intermediate Ly6C-positive monocytes expressing interleukin-6 and TNFα in the circulation of elderly mice and people.65 Although these monocytes infiltrate tissue that is inflamed and infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae, they are not effective at clearing bacteria because of their impaired macrophage differentiation.65 Furthermore, TLR7 and TLR8-activated neutrophils in elderly people cleave FcgRIIA off CD14-positive monocytes in peripheral blood, thus impairing their ability to clear immune complexes and remove senescent, apoptotic, and malfunctioning cells and microbes.13,57 This mechanism further fuels inflammaging because unremoved apoptotic cells become necrotic and senescent cells expressing senescent-associated secretory phenotype. Intermediate monocytes, particularly their subsets that express proangiogenic endoglin, VEGFR-2, and angiopoietin receptor Tie2 (so-called Tie2-expressing monocytes), infiltrate tumour sites and promote tumour-supporting neoangiogenesis.64 Unlike the two main subsets, whose frequency and absolute numbers in elderly people can be unchanged, increased, or decreased,13,65 intermediate monocytes substantially increase with advanced age and frailty, after bacterial infection, and in peripheral blood of patients with early-stage colorectal cancer.13,65

Dendritic cells

Monocytes also differentiate into monocyte-derived dendritic cells, for example, upon stimulation with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-4.66 However, monocyte numbers increase in ageing while CD34-positive precursors and dendritic cells in mice and circulating myeloid dendritic cells (CD11c-positive and CD141-positive) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells decrease in elderly people, particularly at advanced age (>80 years).67,68 This evidence suggests that ageing might also affect the differentiation of dendritic cells. The remaining dendritic cells exhibit signs of maturation and dysfunction, such as impaired production of interleukin-12 after stimulation.67 Ageing plasmacytoid dendritic cells also secrete less interferon α because of decreased expression of TLR7 and TLR9.68 Thus, considering their importance in antigen presentation and subsequent initiation and regulation of antitumour T cells, dendritic cell dysfunction is expected to profoundly affect clearance of impaired and malignant cells. Moreover, inflammaging activates indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase in myeloid cells, possibly via interferons. As a key enzyme that shifts the catabolism of the essential amino acid tryptophan towards production of kynurenine, activated indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase-expressing plasmacytoid dendritic cells prevent clonal expansion of tumour-specific T cell in tumour-draining lymph nodes by depleting tryptophan.69

Macrophages

The number of inflammatory CD115 monocytes decreases with ageing,13 suggesting that these monocytes are being differentiated into macrophages and possibly M1 macrophages because of the interferon γ-containing ageing environment. The presence of interferon γ skews the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-4-induced monocyte-to-dendritic cell differentiation into CD14 and CD64-positive macrophages by inducing autocrine production of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-6.66 Notably, here we use a simplistic definition of macrophages as M1 (based on expression of TNFα, interleukin-12, interleukin-23, CXCL9, CXCL10, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species) and M2 (express arginase 1 and T helper type 2 cytokines interleukin-4, and interleukin-13); however, macrophages are functionally and phenotypically heterogeneous depending on their origin and tissue location. Both M1 and M2 macrophages accumulate during the ageing process, possibly in different compartments, such as inflammatory and pathogenic M1 macrophages in peripheral and adipose tissues and liver, and possible immunosuppressive M2 macrophages in the spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, lung, and muscle. Monocyte-derived macrophages differ from resident macrophages of the spleen, peritoneum, liver, lung, and brain, which are self-maintained after the differentiation from embryonic precursors. Functionally, resident macrophages control so-called housekeeping mechanisms and tissue homeostasis by non-inflammatory phagocytosis of senescent and apoptotic cells and microbes, by inducing repair and healing of tissues and wounds, and by resolving inflammation. Murine large peritoneal macrophages not only produce high concentrations of immunoregulatory transforming growth factor β and interleukin-10, but also induce gut-associated tissue-independent IgA production from peritoneal innate B1 cells.70 They also respond differently to lipopolysaccharide. Monocyte-derived macrophages produce proinflammatory cytokines, whereas large peritoneal macrophages express granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor upon lipopolysaccharide stimulation. In a steady state, Ly6CHiCCR2-positive monocytes can differentiate into colonic resident CX3CR1Hi macrophages, which scavenge bacteria without inducing inflammation via TLR ligands.71 Murine CCR2-positive inflammatory macrophages also infiltrate the liver and become metastasis-associated macrophages (CCR2+CD11b+F4/80+Ly6G−), while CD68-positive macrophages in human beings are associated with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and liver metastasis. In the liver, these macrophages promote and sustain metastatic tumour growth by secreting granulin and activating resident hepatic stellate cells into myofibroblasts.72 Macrophages also produce prostaglandin E2 and interleukin-10 to maintain epithelial cells and regulatory T cells. Inflammation also arrests differentiation of Ly6CHiCCR2-positive monocytes by converting them into proinflammatory CX3CR1Int macrophages that respond to TLR stimulations and promote experimental colitis in mice and Crohn’s disease in human beings.71 Thus, lipopolysaccharide and other microbial products—which are elevated in ageing due to gut dysbiosis—increase the dominance of inflammatory macrophages over resident macrophages at the sites of inflammation, recruit monocytes and reduce large peritoneal macrophages in the peritoneum, and induce necrosis of murine alveolar macrophages through the CD14–P2X7 receptor–Ca2+ pathway.73 MAMPs, PAMPs, and danger-associated molecular patterns (from dying hepatocytes, for example) trigger nucleotide oligomerisation domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 inflammasome in resident macrophages by inducing stress and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, which upregulate interleukin-1β production, recruit neutrophils, and damage liver tissue.74 Ageing also increases the production of reactive oxygen species, TNFα, and interferon γ from macrophages and monocytes,13,14 thereby promoting oncogene expression and activation of TP53, which induces tumour cell senescence, senescent-associated secretory phenotype,5,75 and tumour escape.45 Evidence has shown that even a brief induction of TP53 expression was sufficient to cause tumour regression in a mosaic mouse model of liver carcinoma.75 Senescent-associated secretory phenotype also activates and recruits antitumour inflammatory macrophages, monocytes, natural killer cells, and T-helper-type 1 CD4 T cells.76 However, a chronic proinflammatory cytokine environment,39 such as that associated with ageing, and impaired phagocytosis of M1 macrophages and monocytes13 will facilitate multistage carcinogenesis through the promotion of survival and subsequent expansion of senescent and dormant tumours,5 thereby providing a selective advantage to oncogenically-initiated cells in ageing.47

Conclusion

By 2030, the prevalence of various types of cancer will increase by about 67% in elderly people, including myeloma (57%) and stomach (67%), liver (59%), prostate (55%), pancreatic (55%), bladder (54), lung (52%), and colorectal (52%) cancer.1 This disproportionately high risk of cancer in the elderly might be induced by inflammaging and maintained by gut microbiota. Ageing reduces the diversity and density of beneficial commensals in the gut, which control pathogens and maintain intestinal barrier integrity through the production of mucus and lipid metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids. We propose that age-related changes in the number of gut bacteria lead to dysbiosis and leakage of proinflammatory microbial products. In turn, this situation dysregulates the function of myeloid cells to clear impaired and senescent cells, by, for example, impairing the ability of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to induce adaptive immune responses to neoantigens and by reducing phagocytosis of neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. Thus, because of deficient immune surveillance and inflammaging-impaired protective and compensatory control of senescence and dormant tumour cells, the senescent-associated secretory phenotype further increases inflammation that, in turn, supports carcinogenesis, while dormant tumours accumulate additional mutations that enable them to awaken from their dormant state.

The outcomes of inflammaging and cancer, however, are two-fold. On the one hand, inflammation is required for cancer eradication. Bacteroides improve the antitumour efficacy of anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 immunotherapy in mice and human beings77 and the loss of inflammation after antibiotic treatment or in germ-free mice impairs antitumour efficacy of CpG oligode-oxynucleotide plus anti-interleukin-10 or oxiplatin therapy.78 Bifidobacteria also halt melanoma growth in mice by reversing inflammaging-induced dysfunction of dendritic cells and improving activation of CD8 T cells after anti-programmed cell death-ligand-1 immunotherapy.79 On the other hand, some tumours are less efficient in elderly people80 and in obese people, where incidences of lung cancer, premenopausal breast cancer, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma are reduced.81 Similarly, ageing retards the growth of B16-F10 melanoma in mice, which we linked to ageing monocyte-induced accumulation of innate B1a cells. These cells, termed 4BL cells because of an abundance of surface 4-1BB ligands, membrane-bound TNFα, and MHC class I expression, accumulate in ageing mice, primates, and human beings and induce the generation of antigen-specific granzyme-expressing cytolytic CD8 T cells.82 The removal of monocytes in old mice or macaques by antibody depletion or by antibiotic treatment also eliminates 4BL cells and granzyme-positive CD8 T cells, thus restoring aggressive growth of B16 melanoma cells in old mice (Biragyn A, unpublished).82 Overall, the same treatment can either improve or worsen the disease depending on the age of a patient (ie, presence or absence of gut dysbiosis). The presence of a pre-existing inflammation in old age can cause lethal toxicity to immunotherapy treatment by exacerbating innate immune responses.14 Thus, further studies should seek to understand what metrics in the gut microbiome and immune status can be applied in clinical practice to predict cancer risk and outcomes of treatment in elderly people and to help advance our knowledge of the influence of the gut microbiota on ageing.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

We searched MEDLINE and PubMed for peer-reviewed scientific journals between July 11, 2017 and Jan 10, 2018, using the terms “microbiota and microbiome”, “inflammation, aging, and cancer”, “inflammaging and dysbiosis”, “cancer”, “aging and cancer risk”, AND “myeloid cells, neutrophils, monocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages, and function in” AND “inflammation” OR “elderly, aging” OR “mice, rodents, and humans”. Only articles published in English were considered. We also included major review articles from noted experts.

Acknowledgments

This work was fully funded by Intramural Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Footnotes

Contributors

AB was responsible for the literature search, figures, and table.

AB and LF interpreted data and wrote this Series paper.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1029–36. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Census Bureau. [accessed Dec 1, 2017];Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050. 1996 https://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p25-1130/p251130.pdf.

- 4.Tomasetti C, Li L, Vogelstein B. Stem cell divisions, somatic mutations, cancer etiology, and cancer prevention. Science. 2017;355:1330–34. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang TW, Yevsa T, Woller N, et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature. 2011;479:547–51. doi: 10.1038/nature10599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350:207–11. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnet M. Cancer—a biological approach. I. The processes of control. BMJ. 1957;1:779–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5022.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebastiani P, Thyagarajan B, Sun F, et al. Biomarker signatures of aging. Aging Cell. 2017;16:329–38. doi: 10.1111/acel.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biagi E, Nylund L, Candela M, et al. Through ageing, and beyond: gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffery IB, Lynch DB, O’Toole PW. Composition and temporal stability of the gut microbiota in older persons. ISME J. 2016;10:170–82. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cullender TC, Chassaing B, Janzon A, et al. Innate and adaptive immunity interact to quench microbiome flagellar motility in the gut. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:571–81. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, et al. Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging Cell. 2012;11:867–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouchlaka MN, Sckisel GD, Chen M, et al. Aging predisposes to acute inflammatory induced pathology after tumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2223–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. published online Jan 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aan4236. published online Jan 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–87. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crusz SM, Balkwill FR. Inflammation and cancer: advances and new agents. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:584–96. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:313–23. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500:232–36. doi: 10.1038/nature12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macia L, Tan J, Vieira AT, et al. Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6734. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nastasi C, Candela M, Bonefeld CM, et al. The effect of short-chain fatty acids on human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16148. doi: 10.1038/srep16148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byndloss MX, Olsan EE, Rivera-Chavez F, et al. Microbiota-activated PPAR-gamma signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science. 2017;357:570–75. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL, et al. Crosstalk between microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and intestinal epithelial HIF augments tissue barrier function. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:662–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang PV, Hao LM, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:2247–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322269111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–50. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukovac S, Belzer C, Pellis L, et al. Differential modulation by Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii of host peripheral lipid metabolism and histone acetylation in mouse gut organoids. MBio. 2014;5:e01438–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01438-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16731–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:107. doi: 10.1038/nm.4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto M, Kurihara S, Kibe R, Ashida H, Benno Y. Longevity in mice is promoted by probiotic-induced suppression of colonic senescence dependent on upregulation of gut bacterial polyamine production. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu B, Elinav E, Huber S, et al. Microbiota-induced activation of epithelial IL-6 signaling links inflammasome-driven inflammation with transmissible cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:9862–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307575110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Toole P, Jeffery IB. Gut bicrobota and aging. Science. 2015;305:1214–15. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kong F, Hua Y, Zeng B, Ning R, Li Y, Zhao J. Gut microbiota signatures of longevity. Curr Biol. 2016;26:R832–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature. 2012;488:178–84. doi: 10.1038/nature11319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rampelli S, Candela M, Turroni S, et al. Functional metagenomic profiling of intestinal microbiome in extreme ageing. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5:902–12. doi: 10.18632/aging.100623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodmansey EJ, McMurdo ME, Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Comparison of compositions and metabolic activities of fecal microbiotas in young adults and in antibiotic-treated and non-antibiotic-treated elderly subjects. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6113–22. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6113-6122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talegawkar SA, Bandinelli S, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. A higher adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet is inversely associated with the development of frailty in community-dwelling elderly men and women. J Nutr. 2012;142:2161–66. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.165498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger NA. Obesity and cancer pathogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2014;1311:57–76. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshimoto S, Loo TM, Atarashi K, et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature. 2013;499:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Thuren T, et al. Effect of interleukin-1beta inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1833–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32247-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thevaranjan N, Puchta A, Schulz C, et al. Age-associated microbial dysbiosis promotes intestinal permeability, systemic inflammation, and macrophage dysfunction. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:455–66. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sacksteder MR. Occurrence of spontaneous tumors in the germfree F344 rat. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57:1371–73. doi: 10.1093/jnci/57.6.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrucci L, Corsi A, Lauretani F, et al. The origins of age-related proinflammatory state. Blood. 2005;105:2294–99. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suganuma M, Okabe S, Marino MW, Sakai A, Sueoka E, Fujiki H. Essential role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) in tumor promotion as revealed by TNF-alpha-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4516–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller-Hermelink N, Braumuller H, Pichler B, et al. TNFR1 signaling and IFN-gamma signaling determine whether T cells induce tumor dormancy or promote multistage carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:507–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henry CJ, Casas-Selves M, Kim J, et al. Aging-associated inflammation promotes selection for adaptive oncogenic events in B cell progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4666–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI83024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Challen GA, Boles NC, Chambers SM, Goodell MA. Distinct hematopoietic stem cell subtypes are differentially regulated by TGF-beta1. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:265–78. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baldridge MT, King KY, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, Goodell MA. Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-gamma in response to chronic infection. Nature. 2010;465:793–97. doi: 10.1038/nature09135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grizzle WE, Xu X, Zhang S, et al. Age-related increase of tumor susceptibility is associated with myeloid-derived suppressor cell mediated suppression of T cell cytotoxicity in recombinant inbred BXD12 mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:672–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hurez V, Daniel BJ, Sun L, et al. Mitigating age-related immune dysfunction heightens the efficacy of tumor immunotherapy in aged mice. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2089–99. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sapey E, Greenwood H, Walton G, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition restores neutrophil accuracy in the elderly: toward targeted treatments for immunosenescence. Blood. 2014;123:239–48. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-519520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tortorella C, Piazzolla G, Spaccavento F, Vella F, Pace L, Antonaci S. Regulatory role of extracellular matrix proteins in neutrophil respiratory burst during aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;119:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang D, Chen G, Manwani D, et al. Neutrophil ageing is regulated by the microbiome. Nature. 2015;525:528–32. doi: 10.1038/nature15367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Demers M, Wong SL, Martinod K, et al. Priming of neutrophils toward NETosis promotes tumor growth. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1134073. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1134073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lood C, Arve S, Ledbetter J, Elkon KB. TLR7/8 activation in neutrophils impairs immune complex phagocytosis through shedding of FcgRIIA. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2103. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM. De novo carcinogenesis promoted by chronic inflammation is B lymphocyte dependent. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:411–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rowley DA, Stach RM. B lymphocytes secreting IgG linked to latent transforming growth factor-beta prevent primary cytolytic T lymphocyte responses. Int Immunol. 1998;10:355–63. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:e74–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.El Khoury J, Toft M, Hickman SE, et al. CCR2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:432–38. doi: 10.1038/nm1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–25. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hanna RN, Cekic C, Sag D, et al. Patrolling monocytes control tumor metastasis to the lung. Science. 2015;350:985–90. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zawada AM, Rogacev KS, Rotter B, et al. SuperSAGE evidence for CD14++CD16+ monocytes as a third monocyte subset. Blood. 2011;118:e50–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-326827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Puchta A, Naidoo A, Verschoor CP, et al. TNF drives monocyte dysfunction with age and results in impaired anti-pneumococcal immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005368. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delneste Y, Charbonnier P, Herbault N, et al. Interferon-gamma switches monocyte differentiation from dendritic cells to macrophages. Blood. 2003;101:143–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Della Bella S, Bierti L, Presicce P, et al. Peripheral blood dendritic cells and monocytes are differently regulated in the elderly. Clin Immunol. 2007;122:220–28. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jing Y, Shaheen E, Drake RR, Chen N, Gravenstein S, Deng Y. Aging is associated with a numerical and functional decline in plasmacytoid dendritic cells, whereas myeloid dendritic cells are relatively unaltered in human peripheral blood. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:777–84. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Munn DH, Mellor AL. IDO and tolerance to tumors. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue-specific signals control reversible program of localization and functional polarization of macrophages. Cell. 2014;157:832–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bain CC, Scott CL, Uronen-Hansson H, et al. Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:498–510. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nielsen SR, Quaranta V, Linford A, et al. Macrophage-secreted granulin supports pancreatic cancer metastasis by inducing liver fibrosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:549–60. doi: 10.1038/ncb3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dagvadorj J, Shimada K, Chen S, et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces alveolar macrophage necrosis via CD14 and the P2X7 receptor leading to interleukin-1alpha release. Immunity. 2015;42:640–53. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhong Z, Umemura A, Sanchez-Lopez E, et al. NF-kappaB restricts inflammasome activation via elimination of damaged mitochondria. Cell. 2016;164:896–910. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–60. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Braumuller H, Wieder T, Brenner E, et al. T-helper-1-cell cytokines drive cancer into senescence. Nature. 2013;494:361–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vetizou M, Pitt JM, Daillere R, et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science. 2015;350:1079–84. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, et al. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2013;342:967–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1240527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015;350:1084–89. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Denduluri N, Ershler WB. Aging biology and cancer. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:137–48. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Handelsman Y, Leroith D, Bloomgarden ZT, et al. Diabetes and cancer—an AACE/ACE consensus statement. Endocr Pract. 2013;19:675–93. doi: 10.4158/EP13248.CS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee-Chang C, Bodogai M, Moritoh K, et al. Aging converts innate B1a cells into potent CD8+ T cell inducers. J Immunol. 2016;196:3385–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]