Abstract

Background

Advances in neonatal healthcare have resulted in decreased mortality after preterm birth but have not led to parallel decreases in morbidity. Academic performance provides insight in the outcomes and specific difficulties and needs of preterm children.

Objective

To study academic performance in preterm children born in the antenatal steroids and surfactant era and possible moderating effects of perinatal and demographic factors.

Design

PubMed, Web of Science and PsycINFO were searched for peer-reviewed articles. Cohort studies with a full-term control group reporting standardised academic performance scores of preterm children (<37 weeks of gestation) at age 5 years or older and born in the antenatal steroids and surfactant era were included. Academic test scores and special educational needs of preterm and full-term children were analysed using random effects meta-analysis. Random effects meta-regressions were performed to explore the predictive role of perinatal and demographic factors for between-study variance in effect sizes.

Results

The 17 eligible studies included 2390 preterm children and 1549 controls. Preterm children scored 0.71 SD below full-term peers on arithmetic (p<0.001), 0.44 and 0.52 SD lower on reading and spelling (p<0.001) and were 2.85 times more likely to receive special educational assistance (95% CI 2.12 to 3.84, p<0.001). Bronchopulmonarydysplasia explained 44% of the variance in academic performance (p=0.006).

Conclusion

Preterm children born in the antenatal steroids and surfactant era show considerable academic difficulties. Preterm children with bronchopulmonarydysplasia are at particular risk for poor academic outcome.

Keywords: neonatology, neurodevelopment, outcomes research

What is already known on this topic?

The introduction of antenatal steroids and surfactant therapy have resulted in a considerable decline in mortality but not in morbidity rates after preterm birth.

Very preterm children born before the introduction of antenatal steroids and surfactant show moderate to severe academic difficulties.

Several perinatal and demographic factors are associated with poor neurodevelopmental outcomes, but the effects on academic performance have not been aggregated across the available studies.

What this study adds?

This meta-analysis provides insight in academic performance of the current population of preterm children and moderating effects of perinatal and demographic risk factors.

Preterm children have substantial difficulties in reading, spelling and arithmetic and are almost three times more likely to receive special educational assistance compared with controls.

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia was found to be the most important risk factor for poor academic outcomes.

Since 1990, worldwide preterm birth rates have increased to 11.1% in 2010.1 Since the introduction of antenatal steroids and surfactant in the early 90s, mortality rates of preterm infants (<37 weeks of gestation) have declined considerably.2 However, the decline in mortality is not accompanied by a similar decline in morbidity.3 4 Consequently, absolute numbers of preterm children with neurodevelopmental disabilities have increased and likely continue to increase.2 Providing care, interventions and education fitting the specific needs of these children will therefore place a growing burden on societies.

Academic performance provides an important measure of outcome of preterm children, because it has substantial, causal effects on health, mortality and life chances.5 6 Preterm birth is associated with lower incomes and increased reliance on social security in adulthood, which was predicted by decreased academic abilities.7 More insight into academic difficulties of preterm children may help prevent academic failure and thereby reduce long-term individual burden and societal costs. In a meta-analysis on reading abilities in preterm children at school-age, Kovachy and colleagues8 found worse decoding and reading comprehension abilities in preterm children compared with controls. Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Aarnoudse-Moens and colleagues9 showed moderate to severe difficulties in reading, spelling and arithmetic in very preterm children (<32 weeks of gestation). However, the vast majority of studies included in that meta-analysis comprised cohorts of children born before the introduction of antenatal steroids and surfactant. The present meta-analysis aims to provide insight into academic outcomes of preterm children born in the antenatal steroids and surfactant era.

Outcome data of the current population of preterm children is necessary to help guide medical decision making and parental counselling. In addition, data on perinatal and demographic factors may help to identify those children most at risk for adverse outcomes. This will benefit decision making in the neonatal period and may indicate where interventions should focus on to decrease these risks. For example, preterm children suffering from bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) have increased risks for academic difficulties.10 Other factors predictive of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes are periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) and neonatal infectious diseases.11–13 However, the effects on academic performance remain unclear. The current meta-analysis studies arithmetic, reading and spelling performance of preterm children. In addition, potential moderating effects of perinatal and demographic factors on academic performance are explored.

Methods

Study selection

This meta-analysis was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.14 Inclusion criteria for study selection were (1) the study concerned preterm children (<37 weeks GA); (2) children were born in the antenatal steroids and surfactant era (ie, 1990 or later or earlier studies explicitly reporting antenatal steroids and surfactant use or use confirmed by authors); (3) age at assessment was 5 years or older; (4) academic performance was evaluated using standardised tests; (5) a full-term control group was included; (6) and publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

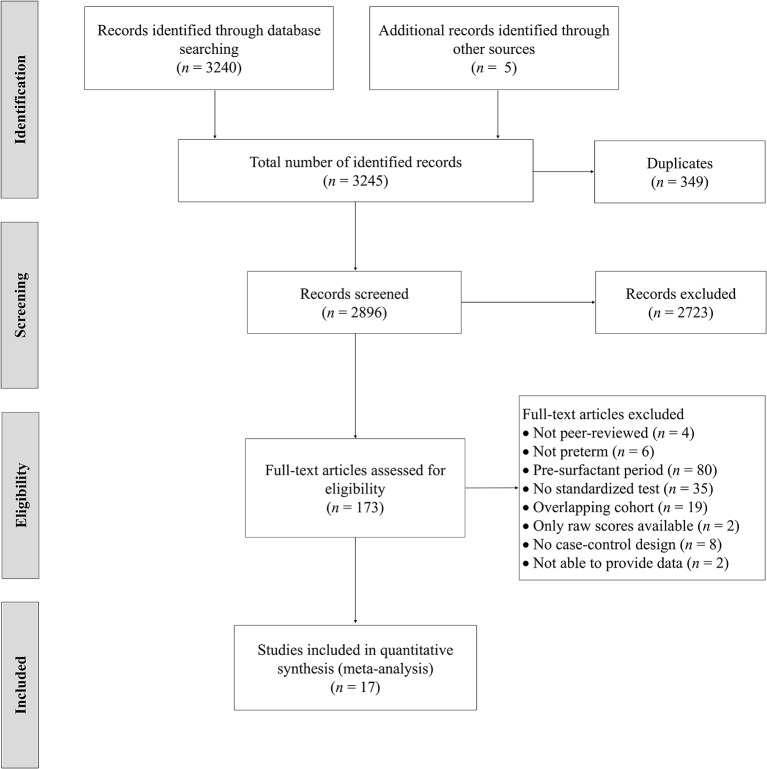

PubMed, Web of Science, ERIC and PsycINFO were searched using combinations of the following terms: premature*, preterm, low birth weight, academic, school, learning, reading, spelling, math*, arithmetic (last search: January 2017). Reference lists of relevant articles were scanned to identify additional relevant studies. The selection process is depicted in figure 1. Retrieved records were screened based on title and abstract to further establish relevance. Subsequently, 173 articles were assessed full-text for eligibility. Seventeen studies met all inclusion criteria. For overlapping cohorts, the study with the longest follow-up interval, most complete data and largest sample was selected.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the study selection procedure.

Outcomes and moderators

Details of the included studies are presented in table 1. Arithmetic, reading and spelling performance data for preterm children and controls were extracted from the studies. If necessary, authors were contacted for additional data. The academic tests used in the studies are listed in table 1. All tests are widely used, validated, norm-referenced tests and have age-standardised scores with a mean of 100 and a SD of 15. For special educational needs (SEN), percentages of preterm and full-term children receiving any form of special educational assistance were compared. Definitions of SEN per study are provided as online supplementary material. Information on GA, birth weight (BW), age at assessment, IQ, sex, ethnicity, maternal education, small for gestational age (SGA) status, IVH grade I/II, IVH grade III/IV, PVL, BPD, postnatal corticosteroids use and infectious diseases (necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), meningitis and sepsis) was extracted from the studies to create moderator variables. An overview of these details for each study is provided in table 2.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics, tests used to assessment academic achievement, results per academic domain and percentage of children with special educational needs (SEN)

| Year | Author | Sample | GA, weeks M (SD) |

BW, grams M (SD) |

Age, years M (SD) |

IQ M (SD) |

Test | Study quality | Academic performance test scores M (SD) |

SEN, % | ||

| Reading | Spelling | Arithmetic | ||||||||||

| 2003 | Assel et al 22 | 160 PT | 29.7 (2.5) | 1111 (264) | 8.2 (0.4) | NA | WJTA | 5 | NA | NA | 93.7 (22.3) | NA |

| 90 FT | 39.9 (0.2) | 3212 (735) | NA | 101.0 (15.4) | ||||||||

| 2013 | Cheong et al 31 | 147 EP | 25.8 (1.1) | 897 (177) | 18.0 (NA) | 95.7 (15.9) | WRAT | 7 | 95.5 (13.5) | 97.1 (15.2) | 85.2 (14.0) | 23.7 |

| 131 FT | 39.3 (1.3) | 3441 (457) | NA | 107.6 (12.8) | 101.1 (13.6) | 105.1 (14.0) | 95.6 (14.3) | 9.4 | ||||

| 2015 | Clark and Woodward32 | 102 VP/VLBW | 27.9 (2.3) | 1071 (313) | 9.0 (NA) | 95.5 (14.6) | WJTA | 4 | 96.8 (15.6) | 93.5 (16.0) | 89.0 (16.0) | 39.0 |

| 108 FT | 39.5 (1.2) | 3575 (410) | NA | 106.9 (11.7) | 106.2 (13.4) | 101.8 (13.9) | 99.4 (15.5) | 20.0 | ||||

| 2009 | Frye et al 20 | 156 PT | 29.6 (2.1)* | 1109 (205) | 12.7 (0.5) | NA | WJTA | 4 | 103.4 (19.8)* | NA | NA | NA |

| 97 FT | NA | 3242 (630) | NA | 93.5 (17.29) | ||||||||

| 2013 | Hutchinson et al 33 | 189 EP/ELBW | 26.5 (2.0) | 833 (164) | 8.5 (0.4) | 93.1 (16.1) | WRAT | 6 | 98.0 (16.1) | 96.8 (15.2) | 90.0 (16.9) | NA |

| 173 FT/NBW | 39.3 (1.1) | 3506 (1455) | 8.5 (0.4) | 105.6 (12.4) | 105.5 (13.8) | 104.2 (14.4) | 99.1 (14.5 | |||||

| 2011 | Johnson et al 24 | 219 EP | 24.5 (0.7) | 745 (130)† | 10.9 (0.4) | 83.7 (18.0) | WIAT | 5 | 80.2 (20.3) | NA | 71.2 (20.9) | 61.4 |

| 153 FT | NA | NA | 10.9 (0.6) | 104.1 (11.1) | 98.5 (11.6) | 98.5 (15.0) | 11.2 | |||||

| 2012 | Litt et al 34 | 181 ELBW | 26.4 (2.0) | 815 (124) | 14.7 (0.7) | 87.1 (18.9) | WJTA | 3 | 88.6 (21.9) | NA | 81.3 (20.7) | 48.6 |

| 115 NBW | NA | 3260 (524) | 14.8 (0.8) | 96.4 (13.4) | 95.5 (14.1) | 93.2 (17.2) | 9.6 | |||||

| 2012 | Loe et al 23 | 72 PT | 28.8 (2.7) | 1226 (466) | 12.2 (1.8) | 102.0 (15.8) | WJTA | 4 | 105 (13.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| 42 FT | 39.7 (1.2) | 3474 (492) | 12.6 (2.0) | 114.0 (13.1) | 111 (10.9) | |||||||

| 2009 | Luu et al 16 | 375 VLBW | 28.0 (2.0) | 961 (174) | 12.2 (0.4) | 87.9 (18.3) | TOWRE | 3 | 91.2 (20.3)‡ | NA | NA | 46.6 |

| 111 FT | NA | NA | 12.7 (0.8) | 103.8 (15.7) | GRST | 101.9 (16.7)‡ | 16.2 | |||||

| 2014 | McNicholas et al 35 | 55 VLBW | 29.9 (2.8) | 1172 (219) | 11.6 (1.0) | 89.7 (12.5) | WIAT | 5 | 95.3 (15.0) | NA | 89.5 (16.1) | 33.0 |

| 45 NBW | NA | NA | NA | 101.3 (11.7) | 101.5 (NA) | 94.0 (NA) | 9.4 | |||||

| 2012 | Northam et al 36 | 50 VP | 27.0 (2.0) | 1081 (385) | 16.2 (1.4) | 92.0 (11.8) | WORD | 5 | 96.0 (14.0) | 96.0 (14.0) | NA | NA |

| 30 FT | NA | NA | 15.8 (1.2) | 108.8 (17.2) | 105.0 (12.0) | 104.0 (13.0) | ||||||

| 2011 | Rose et al 17 | 44 PT | 29.7 (2.8) | 1165 (268) | 11.2 (0.4) | 85.7 (14.3) | WJTA | 4 | 96.9 (14.7) | NA | 95.3 (14.0)‡ | NA |

| 87 FT | NA | NA | 11.1 (0.4) | 95.4 (11.6) | 101.0 (11.4) | 100.0 (12.3)‡ | ||||||

| 2015 | Sayeur et al 37 | 10 PT | 28.7 (1.8) | 1222 (238) | 7.6 (0.5) | 111.6 (10.5) | WIAT | 2 | 106.0 (23.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| 10 FT | 38.7 (1.3) | 3357 (801) | 7.6 (0.5) | 112.4 (8.9) | 105.1 (18.2) | |||||||

| 2003 | Short et al 18 | 173 VLBW | 28.3 (2.0)* | 1085 (223) | 8.8 (0.6) | 86.7 (18.4) | WJTA | 5 | 96.1 (21.3)*‡ | NA | 92.8 (21.4)*‡ | 43.4 |

| 99 NBW | NA | NA | NA | 101.9 (15.0) | 105.1 (18.0)‡ | 109.3 (17.1)‡ | 25.3 | |||||

| 2015 | Simms et al 38 | 115 VP | 28.6 (2.0) | 1213 (365) | 9.7 (0.7) | 97.8 (19.4) | WIAT | 5 | NA | NA | 91.3 (18.8) | NA |

| 77 FT | NA | NA | 9.5 (0.7) | 104.9 (20.8) | 103.6 (20.7) | |||||||

| 2011 | Taylor et al 39 | 148 EP/ELBW | 25.9 (1.6) | 818 (174) | 6.0 (0.4) | 86.3 (21.1) | WJTA | 5 | 106.1 (13.5) | 92.1 (15.7) | 98.8 (13.5) | 58.7 |

| 111 NBW | NA | 3382 (446) | 6.0 (0.3) | 105.5 (16.6) | 110.1 (13.5) | 100.6 (15.7) | 105.8 (13.4) | 29.0 | ||||

| 2016 | Taylor et al 40 | 194 VP | 27.5 (1.9) | 962 (223) | 7.5 (0.3) | 96.0 (15.1) | WRAT | 6 | 98.2 (19.6) | 97.9 (19.2) | 88.8 (18.4) | 41.0 |

| 70 FT | 39.1 (1.3) | 3323 (508) | 7.6 (0.3) | 107.0 (12.8) | 107.9 (16.9) | 106.2 (16.5) | 99.7 (14.1) | 9.0 | ||||

*Weighted mean and pooled SD of two subsamples.

†Estimated from median and IQR.

‡Weighted mean and pooled SD of subtests scores.

BW, birth weight; ELBW, extremely low birth weight (<1000 g); EP, extremely preterm (<28 weeks GA); FT, full-term (≥37 weeks GA); GA, gestational age; GRST, Grey Silent Reading Tests; M, mean; NA, not available; NBW, normal birth weight (≥2500 g); PT, preterm (<37 weeks GA); SEN, special educational needs; TOWRE, Test of Word Reading Efficiency; VLBW, very low birth weight (<1500 g); VP, very preterm (<32 weeks GA); WIAT, Wechsler Individual Achievement Test; WJTA, Woodcock Johnson Tests of Achievement; WORD, Wechsler Objective Reading Dimensions; WRAT, Wide Range Achievement Test.

Table 2.

Demographic and perinatal sample characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Year | Author | GA, weeks M (SD) |

BW, grams M (SD) |

Age, years M (SD) |

% SGA | % IVH I/II | % IVH III/IV | % PVL | % BPD | % NEC | % Meningitis | % Sepsis | % PCS use | % Mothers <12 years education |

% Male | % Non-Caucasian |

| 2003 | Assel et al 22 | 29.7 (2.5) | 1111 (264) | 8.0 (NA) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.0 | NA | NA | NA | 54.0 | 79.0 |

| 2013 | Cheong et al 31 | 25.8 (1.1) | 897 (177) | 18.0 (NA) | 2.7 | NA | 6.8 | 4.1 | 38.5 | NA | NA | NA | 37.2 | 51.8 | 47.3 | NA |

| 2015 | Clark and Woodward32 | 27.9 (2.3) | 1071 (313) | 9.0 (NA) | 10.8 | 11.8 | 5.9 | 4.9 | 34.0 | NA | NA | 29.7 | 5.9 | 40.2 | 51.5 | 88.9 |

| 2009 | Frye et al 20 | 29.6 (2.1) | 1109 (205) | 12.7 (0.5) | NA | 15.4 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 31.5 | NA | 0.0 | NA | NA | NA | 43.9 | 79.9 |

| 2013 | Hutchinson et al 33 | 26.5 (2.0) | 833 (164) | 8.5 (0.4) | 18.0 | NA | 3.7 | 3.2 | 38.1 | 5.0 | NA | NA | 37.0 | 50.3 | 52.9 | NA |

| 2011 | Johnson et al 24 | 24.5 (0.7) | 745 (130)* | 10.9 (0.4) | 0.5 | 49.0 | 10.0 | 16.0 | 73.0 | 3.0 | NA | NA | NA | 76.0 | 46.0 | 18.0 |

| 2012 | Litt et al 34 | 26.4 (2.0) | 815 (124) | 14.7 (0.7) | 33.2 | 34.3 | 13.3 | 6.6 | 41.0 | 5.5 | 8.8 | 49.2 | NA | 39.0 | 38.7 | 60.0 |

| 2012 | Loe et al 23 | 28.8 (2.7) | 1226 (466) | 12.2 (1.8) | 5.6 | 12.5 | 5.6 | 9.7 | 9.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 35.0 | 47.0 | 28.0 |

| 2009 | Luu et al 16 | 28.0 (2.0) | 961 (174) | 12.2 (0.4) | 25.0 | 10.8 | NA | NA | 46.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11.1 | 54.4 | 29.1 |

| 2014 | McNicholas et al 35 | 29.9 (2.8) | 1172 (219) | 11.6 (1.0) | NA | 20.0 | NA | 8.9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 51.1 | NA |

| 2012 | Northam et al 36 | 27.0 (2.0) | 1081 (385) | 16.2 (1.4) | 14.3 | 34.0 | 22.0 | 4.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 38.0 | NA |

| 2011 | Rose et al 17 | 29.7 (2.8) | 1165 (268) | 11.2 (0.4) | 27.3 | 43.2 | 0.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 56.8 | 88.6 |

| 2015 | Sayeur et al 37 | 28.7 (1.8) | 1222 (238) | 7.6 (0.5) | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | 50.0 | NA |

| 2003 | Short et al 18 | 28.3 (2.0) | 1085 (223) | 8.8 (0.6) | NA | 22.5 | 10.4 | NA | 57.0 | NA | NA | NA | 16.2 | NA | 49.1 | 47.0 |

| 2015 | Simms et al 38 | 28.6 (2.0) | 1213 (365) | 9.7 (0.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 62.6 | 54.8 | NA |

| 2011 | Taylor et al 39 | 25.9 (1.6) | 818 (174) | 6.0 (0.4) | 25.0 | NA | 10.1 | NA | 52.0 | 10.1 | 8.0 | 41.9 | NA | 13.5 | 45.9 | 61.5 |

| 2016 | Taylor et al 40 | 27.5 (1.9) | 962 (223) | 7.5 (0.3) | 8.6 | NA | 3.6 | 4.6 | 35.0 | 10.6 | NA | 44.4 | NA | NA | 52.5 | NA |

The highest and lowest value for each factor is underlined.

*Estimated from median and IQR.

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; BW, birth weight; GA, gestational age; IVH I/II, III/IV, intraventricular haemorrhage grade I/II, III/IV; M, mean; NA, not available; NEC, necrotising enterocolitis; PCS, postnatal corticosteroids; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; SGA, small for gestational age.

fetalneonatal-2017-312916supp001.docx (93.6KB, docx)

Study quality

Study quality was assessed using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies.15 Two authors (EST and JFdK) independently rated studies on a 7-point scale with higher scores indicating better quality.

Statistical analyses

This meta-analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V.3.0. The standardised mean difference (SMD) in test scores between preterm and full-term children was used as effect size for arithmetic, reading and spelling. The mean difference of each study was weighted by the inverse of its variance. Composite scores were computed for three studies16–18 with more than one subtest per academic domain. Using the reported correlation coefficients between subtest scores, interrelation among outcomes was taken into account.19 Furthermore, combined effects across subgroups were computed for two studies18 20 that reported data for independent subgroups of preterm children. For SEN, the risk ratio (RR) was used as effect size.

Random effects meta-analyses were performed to calculate combined effect sizes for arithmetic, reading, spelling and SEN. Dispersion across study effect sizes within each domain was tested using Cochran’s Q. I2 was used to quantify this dispersion. The value of I2 shows the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. I2 was interpreted as follows: 30%–60%: moderate; 50%–90%: substantial; and 75%–100%: considerable heterogeneity.21 Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger’s test. Random effects meta-regressions were performed to explore the predictive role of demographic and perinatal factors for between-study variance in effect sizes. As a rule of thumb, meta-regression is thought only to be meaningful with more than 10 studies included in the analysis.21 Due to the small number of studies with available demographic or perinatal details, meta-regressions were performed irrespective of academic domain to increase the number of available studies. For studies reporting results for more than one academic domain, a composite score was calculated. Composite scores were computed using the correlation between subtests to account for interrelation.19 Sensitivity analyses were performed to compare results of analyses with all studies included and analyses excluding those studies in which also moderately/late preterm children were included.

Results

The 17 selected studies included 2390 preterm children and 1549 controls. Arithmetic, reading and spelling performance was evaluated in 12, 15 and 6 studies, respectively. Across studies, GA varied from extremely to late preterm (23–36 weeks), with mean GA ranging from 24.5 to 29.9 weeks. Participants’ ages ranged from 6 to 18 years.

Arithmetic, reading, spelling and SEN

Meta-analytic results revealed significant differences between preterm and full-term children for all academic domains (see table 3). Arithmetic scores of preterm children were 0.71 SD below scores of full-term peers (z=−7.67, p<0.001), indicating a medium effect. Preterm children scored 0.44 and 0.52 SD lower on reading and spelling, respectively, compared with controls (z=−4.38, p<0.001 and z=−9.53, p<0.001), indicating small-sized and medium-sized effects. Results for arithmetic and reading were highly heterogeneous across studies (Q=60.81, p<0.001, I2=81.91 and Q=101.97, p<0.001, I2=86.27), indicating that the pooled effects should be cautiously interpreted. No significant heterogeneity was observed for spelling. Nine studies reported details about SEN for both preterm and full-term children. Based on these studies, preterm children were 2.85 times more likely to receive special educational assistance compared with controls (RR=2.85, 95% CI 2.12 to 3.84, p<0.001). Significant heterogeneity of results was observed (Q=26.19, p=0.001, I2=69.46), indicating cautious interpretation of the pooled estimate. Forest plots are provided as online supplementary material.

Table 3.

Individual study and combined effect sizes (SMD) for arithmetic, reading, spelling and SEN (RR)

| Arithmetic | Reading | Spelling | SEN | |||||||||||||

| Study | SMD | SE | z | I2 | SMD | SE | z | I2 | SMD | SE | Z | I2 | RR | 95% CI | z | I2 |

| Assel et al 22 | −0.36 | 0.13 | −2.74** | |||||||||||||

| Cheong et al 31 | −0.74 | 0.12 | −5.92*** | −0.41 | 0.12 | −3.40** | −0.55 | 0.12 | −4.46*** | 2.52 | 1.45 to 4.40 | 3.26** | ||||

| Clark and Woodward32 | −0.66 | 0.14 | −4.65** | −0.65 | 0.14 | −4.60*** | −0.56 | 0.14 | −3.96*** | 1.95 | 1.25 to 3.05 | 2.92* | ||||

| Frye et al 20 | 0.55 | 0.13 | −4.16*** | |||||||||||||

| Hutchinson et al 33 | −0.58 | 0.11 | −5.36*** | −0.50 | 0.11 | −4.67*** | −0.50 | 0.11 | −4.67*** | |||||||

| Johnson et al 24 | −1.46 | 0.12 | −12.31*** | −1.06 | 0.11 | −9.40*** | 5.55 | 3.49 to 8.81 | 7.25*** | |||||||

| Litt et al 34 | −0.61 | 0.12 | −5.03*** | −0.36 | 0.12 | −2.98** | 5.06 | 2.83 to 9.05 | 5.48*** | |||||||

| Loe et al 23 | −0.47 | 0.20 | −2.41* | |||||||||||||

| Luu et al 16 | −0.78 | 0.11 | −6.91*** | 2.88 | 1.86 to 4.45 | 4.74*** | ||||||||||

| McNicholas et al 35 | −0.91 | 0.21 | -4.32*** | −0.43 | 0.20 | −2.12* | 2.75 | 1.15 to 6.61 | 2.26* | |||||||

| Northam et al 36 | −0.59 | 0.24 | −2.49* | −0.59 | 0.24 | −2.49** | ||||||||||

| Rose et al 17 | −0.42 | 0.19 | −2.26* | −0.36 | 0.19 | −1.94 | ||||||||||

| Sayeur et al 37 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.10 | |||||||||||||

| Short et al 18 | −1.02 | 0.13 | −7.66*** | −0.54 | 0.13 | −4.20*** | 1.72 | 1.17 to 2.51 | 2.79** | |||||||

| Simms et al 38 | −0.63 | 0.15 | −4.16*** | |||||||||||||

| Taylor et al 39 | −0.51 | 0.13 | −3.95*** | −0.30 | 0.13 | −2.32* | −0.54 | 0.13 | −4.19*** | 2.02 | 1.47 to 2.79 | 4.31*** | ||||

| Taylor et al 40 | −0.63 | 0.14 | −4.42*** | −0.51 | 0.14 | −3.63*** | −0.45 | 0.14 | −3.18** | 4.56 | 2.12 to 9.78 | 3.89*** | ||||

| Summary effect | −0.71 | 0.09 | −7.67*** | 81.91 | −0.44 | 0.10 | −4.38*** | 86.27 | −0.52 | 0.06 | −9.53*** | 0.00 | 2.85 | 2.12 to 3.84 | 6.90*** | 69.46 |

*p<.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

RR, risk ratio; SEN, special educational needs; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Sensitivity analyses excluding four studies17 20 22 23 in which also moderately/late preterm children were included showed a combined effect of −0.77 for arithmetic (z=−7.79, p<0.001) and −0.55 for reading (z=−7.46, p<0.001). Results for spelling and SEN remained unchanged.

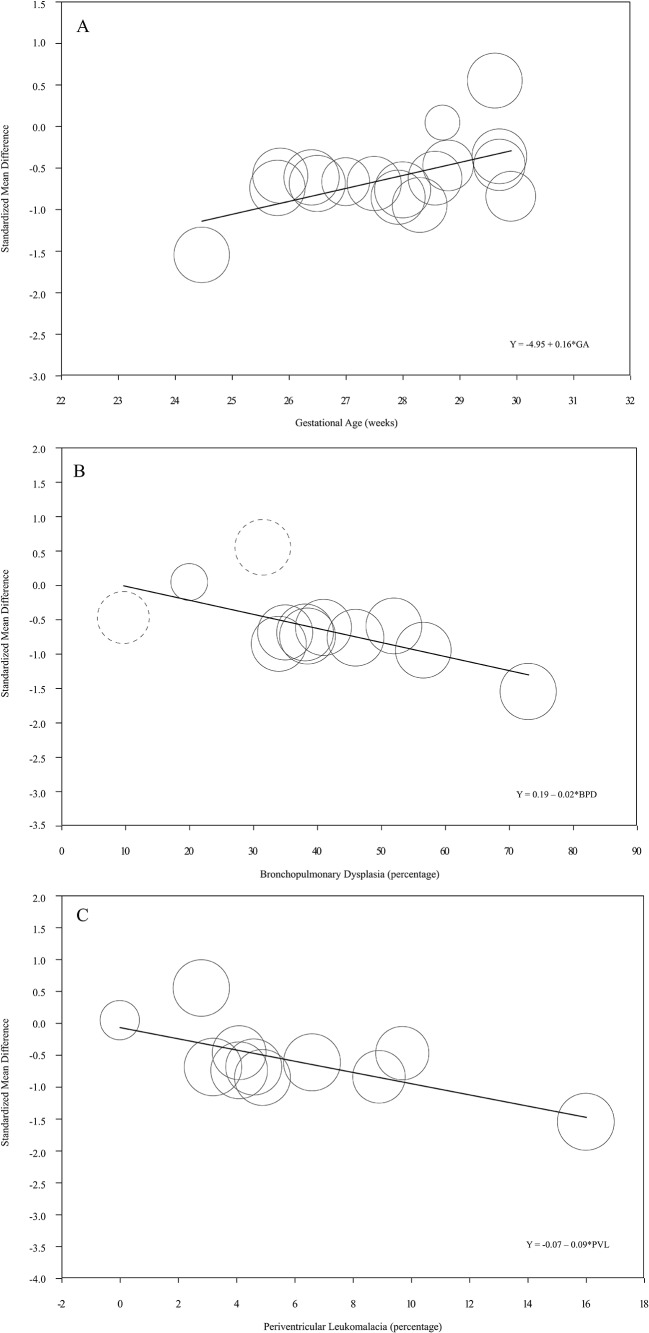

Meta-regression

Random effects meta-regression analyses were performed to explain heterogeneity in results across studies. GA explained a significant proportion of variance (R2=0.39, Q(1)=7.49, p=0.006). Regression plots are shown in figure 2. One study,24 with a considerably lower mean GA (24.5 weeks) compared with the other studies, played a key role in this effect (see figure 2). Additional analysis without this study showed non-significant results. The same study reported a much higher incidence of PVL (16%) compared with other studies. Meta-regression showed a significant result for PVL (R2=0.46, Q(1)=7.33, p=0.007), but additional analysis without this study again was non-significant. BPD explained 44% of the variance in academic performance (Q(1)=7.64, p=0.006) (see figure 2). The difference in intelligence between preterm and controls explained 46% of the variance across studies (Q(1)=8.31, p=0.004). BW, SGA status, IVH grade I/II, IVH grade III/IV, sex, age at assessment, ethnicity, measure of academic performance and study quality were not found to significantly explain heterogeneity. Less than 10 studies reported the incidence of sepsis, meningitis, NEC, postnatal corticosteroids use and maternal education level. The role of these factors could therefore not be assessed.

Figure 2.

Meta-regression of gestational age (A), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (B) and periventricular leukomalacia (C) on the standardised mean difference in academic performance between preterm and full-term children. The dashed circles in figure B indicate studies also including moderately/late preterm children.

Sensitivity analyses without those studies17 20 22 23 also including moderately/late preterm children revealed results highly similar to those obtained in the full sample of studies. Again, intelligence explained a significant proportion of variance across studies (R2=0.42, Q(1)=6.64, p=0.01). The proportion of variance explained by BPD increased from 44% in the full sample of studies to 78% in this subsample of studies (Q(1)=16.44, p<0.001).

Publication bias

Inspection of funnel plots did not suggest publication bias, which was confirmed by non-significant Egger’s test (online supplementary material).

Discussion

This meta-analysis shows that preterm children born in the antenatal steroids and surfactant era have considerable difficulties in arithmetic, reading and spelling. Furthermore, based on the studies included in our meta-analysis, preterm children are almost three times more likely to have SEN. BPD explained 44% of the variance in academic performance across studies. This percentage increased to 78% when focusing solely on studies pertaining to preterm children born at <32 weeks of gestation. Interestingly, this increase is mainly driven by the high incidence of BPD in extremely preterm children and its negative effects on long-term academic outcome. Intelligence explained 46% of the variance, indicating the strong relation between academic performance and intelligence.

Our results show that preterm birth has considerable consequences for academic performance later in life. Given that heterogeneity in results across studies could not be explained by age at assessment, these difficulties seem to remain stable during development from early childhood to adolescence. These findings are in line with the meta-analysis by Kovachy and colleagues8 focused on reading abilities. Different from that meta-analysis, which showed increased reading difficulties with decreasing GA, our results demonstrate comparable academic performance among children born at 26–30 weeks GA. There was only one study included in this meta-analysis with a sample exclusively consisting of children born before 26 weeks of gestation.24 In this study, differences in academic performance between preterm and control children were substantially larger compared with the other studies, which can possibly be explained by the higher incidence of other complications such as PVL. The incidence of PVL was considerably higher in this cohort of extremely immature children compared with other included cohorts. Whereas our results show no differences in academic performance between cohorts with 0%–10% PVL incidence, increased academic difficulties are present in this extremely preterm sample with a relatively high PVL incidence (16%).

The current meta-analysis shows that preterm children with BPD are at particular risk for academic difficulties. The detrimental effect of BPD for later neurocognitive outcomes has been shown in previous studies.10 The exact mechanisms underlying the detrimental effects of BPD on brain development have not been elucidated yet. One explanation is that those children who develop BPD are already more vulnerable and therefore prone to develop BPD. Indeed, the incidence of BPD is increased among neonates with extremely low BW and GA.18 Furthermore, BPD is associated with infection and inflammation,25 which affects lung maturation and interferes with cerebral development.26 Episodic and chronic hypoxia may also contribute to adverse neurocognitive outcomes in BPD.27 Co-occurrence of risk factors makes it difficult to differentiate the adverse effects of BPD from other risk factors that may also affect brain development and thereby academic outcome. Furthermore, it should be realised that BPD may be a marker for adverse academic outcomes, rather than a cause. However, our analyses of other neonatal risk factors suggest that BPD contributes to differences in magnitude of academic difficulties across studies as a single main risk factor, and thus places preterm children at even greater risk to encounter academic difficulties.

This meta-analysis included only cohorts born in the antenatal steroids and surfactant era. In the meta-analysis of Aarnoudse-Moens et al 9 the vast majority of studies included children born before the introduction of these treatments. The two meta-analyses have only one study18 in common but showed similar results. This suggests that, in spite of increased survival rates, the negative effects of prematurity on academic outcomes remained unchanged. This is in line with other studies showing stable morbidity rates over the last decades.3 4 Since the studies in both meta-analyses are comparable in terms of GA, the similarity in results cannot simply be explained by an increased survival of the most immature children in the more recent studies in the current meta-analysis.

One limitation of our meta-analysis is that due to the relatively small number of studies reporting details on risk factors, our meta-regression analyses allowed investigation of one single risk factor at a time. Consequently, the inter-relationship between risk factors could not be taken into account. Preterm birth often carries multiple, inter-related risk factors. It is likely that the risk for academic difficulties is not carried by one single risk factor but rather by a combination of risk factors. Future studies should focus on cumulative or interacting effects of risk factors. Another limitation is the restricted availability of data for certain factors, such as sociodemographic and treatment factors like postnatal corticosteroids use, hindering the opportunity to assess their possibly important role for academic outcomes of preterm children.

This is the first meta-analysis examining academic performance in preterm children born in the antenatal steroids and surfactant era. Results are therefore applicable to the current population of preterm children. It should be noted that the included studies mostly comprised cohorts of extremely and very preterm children. These results may be less applicable to moderately/late preterm children.28 Academic performance is a pre-eminent measure of outcome, given its strong relation with important life outcomes.5 6 Despite influential advances in neonatal healthcare, preterm children show considerable academic difficulties. Given the increasing number of preterm children and the substantial individual, social and economic consequences of academic difficulties in these children,7 29 there is a need to develop strategies that will improve outcomes after preterm birth. These interventions may target perinatal factors associated with adverse outcomes. For example, non-invasive methods such as nasal intermittent positive-pressure ventilation techniques have shown promising results in terms of decreased BPD.30 The results of our meta-analysis emphasise the importance of such developments and innovations.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study concept and design. EST, JFdK, RMvE and JO were involved in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. EST and JFdK drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. EST and JO were responsible for the statistical analyses. Funding was obtained by RMvE and JO, who also supervised the study.

Competing interests: RMvE is employed at Nutricia Research, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379:2162–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Carpenter JH, et al. Trends in mortality and morbidity for very low birth weight infants, 1991-1999. Pediatrics 2002;110:143–51. 10.1542/peds.110.1.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jacobs SE, O’Brien K, Inwood S, et al. Outcome of infants 23-26 weeks’ gestation pre and post surfactant. Acta Paediatr 2000;89:959–65. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2000.tb00417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilson-Costello D, Friedman H, Minich N, et al. Improved survival rates with increased neurodevelopmental disability for extremely low birth weight infants in the 1990s. Pediatrics 2005;115:997–1003. 10.1542/peds.2004-0221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feinstein L, Sabates R, Anderson TM, et al. What are the effects of education on health? In: Desjardins R, Schuller T, eds Measuring the effects of education on health and civic engagement: proceedings of the Copenhagen Symposium. Paris: organisation for Economic Co-operation and development, 2006:171–353. [Google Scholar]

- 6. McMahon WW, Oketch M. Education’s Effects on Individual Life Chances and On Development: An Overview. Br J Educ Stud 2013;61:79–107. 10.1080/00071005.2012.756170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Basten M, Jaekel J, Johnson S, et al. Preterm birth and adult wealth: mathematics skills count. Psychol Sci 2015;26:1608–19. 10.1177/0956797615596230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kovachy VN, Adams JN, Tamaresis JS, et al. Reading abilities in school-aged preterm children: a review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2015;57:410–9. 10.1111/dmcn.12652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, et al. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics 2009;124:717–28. 10.1542/peds.2008-2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hughes CA, O’Gorman LA, Shyr Y, et al. Cognitive performance at school age of very low birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1999;20:1–8. 10.1097/00004703-199902000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Limperopoulos C, Bassan H, Gauvreau K, et al. Does cerebellar injury in premature infants contribute to the high prevalence of long-term cognitive, learning, and behavioral disability in survivors? Pediatrics 2007;120:584–93. 10.1542/peds.2007-1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patra K, Wilson-Costello D, Taylor HG, et al. Grades I-II intraventricular hemorrhage in extremely low birth weight infants: effects on neurodevelopment. J Pediatr 2006;149:169–73. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, et al. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA 2004;292:2357–65. 10.1001/jama.292.19.2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wells GA, Shea B, Oc D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 16. Luu TM, Ment LR, Schneider KC, et al. Lasting effects of preterm birth and neonatal brain hemorrhage at 12 years of age. Pediatrics 2009;123:1037–44. 10.1542/peds.2008-1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rose SA, Feldman JF, Jankowski JJ. Modeling a cascade of effects: the role of speed and executive functioning in preterm/full-term differences in academic achievement. Dev Sci 2011;14:1161–75. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01068.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Short EJ, Klein NK, Lewis BA, et al. Cognitive and academic consequences of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and very low birth weight: 8-year-old outcomes. Pediatrics 2003;112:e359–66. 10.1542/peds.112.5.e359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. Multiple outcomes or time-points within a study Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009:225–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frye RE, Landry SH, Swank PR, et al. Executive dysfunction in poor readers born prematurely at high risk. Dev Neuropsychol 2009;34:254–71. 10.1080/87565640902805727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. The Cochrane Collaboration. In: Higgins J, Green S, eds Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org

- 22. Assel MA, Landry SH, Swank P, et al. Precursors to mathematical skills: examining the roles of Visual-Spatial skills, Executive Processes, and parenting factors. Appl Dev Sci 2003;7:27–38. 10.1207/S1532480XADS0701_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loe IM, Lee ES, Luna B, et al. Executive function skills are associated with reading and parent-rated child function in children born prematurely. Early Hum Dev 2012;88:111–8. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson S, Wolke D, Hennessy E, et al. Educational outcomes in extremely preterm children: neuropsychological correlates and predictors of attainment. Dev Neuropsychol 2011;36:74–95. 10.1080/87565641.2011.540541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balany J, Bhandari V. Understanding the impact of infection, inflammation, and their persistence in the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Front Med 2015;2:1–10. 10.3389/fmed.2015.00090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adams-Chapman I, Stoll BJ. Neonatal infection and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in the preterm infant. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2006;19:290–7. 10.1097/01.qco.0000224825.57976.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raman L, Georgieff MK, Rao R. The role of chronic hypoxia in the development of neurocognitive abnormalities in preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Dev Sci 2006;9:359–67. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wolke D, Strauss VY, Johnson S, et al. Universal gestational age effects on cognitive and basic mathematic processing: 2 cohorts in 2 countries. J Pediatr 2015;166:1410–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.02.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chaikind S, Corman H. The impact of low birthweight on special education costs. J Health Econ 1991;10:291–311. 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90031-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bhandari V, Finer NN, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Synchronized nasal intermittent positive-pressure ventilation and neonatal outcomes. Pediatrics 2009;124:517–26. 10.1542/peds.2008-1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheong JL, Anderson PJ, Roberts G, et al. Contribution of brain size to IQ and educational underperformance in extremely preterm adolescents. PLoS One 2013;8:e77475 10.1371/journal.pone.0077475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clark CA, Woodward LJ. Relation of perinatal risk and early parenting to executive control at the transition to school. Dev Sci 2015;18:525–42. 10.1111/desc.12232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hutchinson EA, De Luca CR, Doyle LW, et al. School-age outcomes of extremely preterm or extremely low birth weight children. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1053–61. 10.1542/peds.2012-2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Litt JS, Gerry Taylor H, Margevicius S, et al. Academic achievement of adolescents born with extremely low birth weight. Acta Paediatr 2012;101:1240–5. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02790.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McNicholas F, Healy E, White M, et al. Medical, cognitive and academic outcomes of very low birth weight infants at age 10-14 years in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 2014;183:525–32. 10.1007/s11845-013-1040-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Northam GB, Liégeois F, Tournier JD, et al. Interhemispheric temporal lobe connectivity predicts language impairment in adolescents born preterm. Brain 2012;135:3781–98. 10.1093/brain/aws276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sayeur MS, Vannasing P, Tremblay E, et al. Visual Development and Neuropsychological Profile in Preterm Children from 6 months to School Age. J Child Neurol 2015;30:1159–73. 10.1177/0883073814555188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simms V, Gilmore C, Cragg L, et al. Nature and origins of mathematics difficulties in very preterm children: a different etiology than developmental dyscalculia. Pediatr Res 2015;77:389–95. 10.1038/pr.2014.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taylor HG, Klein N, Anselmo MG, et al. Learning problems in kindergarten students with extremely preterm birth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:819–25. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taylor R, Pascoe L, Scratch S, et al. A simple screen performed at school entry can predict academic under-achievement at age seven in children born very preterm. J Paediatr Child Health 2016;52:759–64. 10.1111/jpc.13186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

fetalneonatal-2017-312916supp001.docx (93.6KB, docx)