Abstract

Objective

The primary objective of this article is to identify risk factors for infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN) in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for severe acute pancreatitis. We also described outcomes of IPN.

Background

Acute pancreatitis is common and associated with multiple, potentially life-threatening complications. Over the last decade, minimally invasive procedures have been developed to treat IPN.

Methods

We retrospectively studied consecutive patients admitted for severe acute pancreatitis to the ICUs of the Nantes University Hospital in France, between 2012 and 2015. Logistic regression was used to evaluate potential associations linking IPN to baseline patient characteristics and outcomes.

Results

Of the 148 included patients, 26 (17.6%) died. IPN developed in 62 (43%) patients and consistently required radiological, endoscopic, and/or surgical intervention. By multivariate analysis, factors associated with IPN were number of organ failure (OF) (for ≥ 3: OR, 28.67 (6.23–131.96), p < 0.001) and portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis (OR, 8.16 (3.06–21.76)).

Conclusion

IPN occurred in nearly half our ICU patients with acute pancreatitis and consistently required interventional therapy. Number of OFs and portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis were significantly associated with IPN. Early management of OF may reduce IPN incidence, and management of portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis should be investigated.

Keywords: Severe acute pancreatitis, infected pancreatic necrosis, risk factors, intensive care, portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis

Key summary

Infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN) increases the already high morbidity and mortality rates in severe acute pancreatitis. Whereas the step-up approach is now advocated for management of IPN, few clinical risk factors are known. Half the patients in a retrospective cohort developed IPN. Independent risk factors of IPN were portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis and multiple organ failure. Anticoagulation for portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis did not protect from the development of cavernoma.

Introduction

Severe acute pancreatitis is a common reason for intensive care unit (ICU) admission and is associated with prolonged hospital stays and high morbidity and mortality rates.1,2 The Atlanta Classification3 differentiates mild, moderate, and severe acute pancreatitis, and each of these categories correlates with morbidity and mortality. Mortality has decreased during the last decade but remains high, between 10% and 39%, in severe and moderately severe acute pancreatitis.1,4,5 Infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN) is a risk factor for mortality.1,6,7 After the first week, about 30% of patients with necrotising pancreatitis develop IPN.4,5 The treatment of IPN combines antibiotics with interventions, preferably using minimally invasive techniques such as percutaneous and endoscopic drainage, which have been proven beneficial.4,5,8,9 A step-up approach is now advocated, with percutaneous drainage then minimally invasive interventions and, finally, surgical necrosectomy if required.5,9–12 In several studies13,14 biological markers such as procalcitonin and interleukin-8 were effective in predicting IPN. However, few clinical risk factors for IPN have been reported.3,15 Identifying risk factors may help to improve standardised strategies for early diagnosis and treatment and, therefore, patient outcomes.

Here, our primary objective is to identify risk factors for IPN in patients admitted to the ICU for acute pancreatitis. Our secondary objective is to describe the management of IPN, mortality and outcomes of severe acute pancreatitis.

Methods

Study design and patients

We retrospectively reviewed the medical charts of consecutive patients admitted with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis to any of the three ICUs of the University Hospital in Nantes (France) between January 2012 and December 2015. The three ICUs were the hepato-gastroenterology ICU, the general medical ICU, and the surgical ICU. Only the general medical and surgical ICUs were able to provide life-sustaining therapies including mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs, and renal replacement therapy. The three units collaborated closely with one another and applied similar protocols. Patients included in the study were initially admitted to any of the three participating units, according to disease severity at presentation. Patients were transferred from one ICU to another as dictated by their clinical course. The patients were identified by searching the hospital database for International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision codes K85.0 to K85.9. All patients meeting revised Atlanta Classification criteria3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) for moderately severe or severe acute pancreatitis were included. Exclusion criteria were mild acute pancreatitis, defined as no organ failure (OF) or local complication. The ethics committee of the French Intensive Care Society approved the study (#CE SRLF16-09). French legislation on studies of anonymised retrospective data does not require informed consent.

Data collection

The following were recorded: demographics, mortality, hospital and ICU lengths of stay, computed tomography (CT) findings with the CT Severity Index (CTSI) (portosplenomesenteric venous stenosis or thrombosis (PSMVT), presence of gas), development of IPN with the management (percutaneous or endoscopic transluminal drainage, endoscopic or surgical necrosectomy, and antibiotics with the duration of use), and OF, hollow organ perforation, bowel ischaemia, gastrointestinal bleeding, and PSMVT). According to the Atlanta Classification,3 OF was defined as a modified Marshall score16 (Supplemental Digital Content 2) ≥ 2 for the renal, respiratory, or cardiovascular system. All CT images obtained before the first drainage or surgical procedure were subjected to blind review by a radiologist who recorded the presence or absence of gas within pancreatic collection(s) and/or of PSMVT.

Management of patients with suspected IPN

When IPN was suspected by bedside physicians (usually defined by the development of fever, leucocytosis, and increasing abdominal pain), patients underwent CT-guided drainage and/or open surgery. The choice between percutaneous and endoscopic drainage was based on location of the infected collection, which governed ease of access by either technique. Patients with persistent sepsis after the first drainage procedure underwent endoscopic or surgical necrosectomy. First-line open surgical necrosectomy was performed when minimally invasive drainage was deemed to carry a high risk of adverse vascular or bowel events, as well as in patients with acute abdominal manifestations suggesting bowel perforation and/or ischaemia.

Definition of groups with and without IPN

According to previous studies,4,17 patients who died within seven days after the beginnings of pancreatitis were excluded from the comparison between the IPN group and the non-IPN group. Causes of death were recorded. Patients alive after the first week were diagnosed with IPN if they met criteria similar to those used in a large prospective randomised trial (the patients with acute necrotising pancreatitis (PANTER) trial) comparing open necrosectomy to a step-up approach for treating IPN.4 The criteria for definite IPN were CT evidence of a collection containing extraluminal gas or a positive culture of pancreatic tissue obtained by fine-needle aspiration, drainage, or necrosectomy. A strong suspicion of IPN was defined as negative culture but persistent sepsis in a patient with pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis requiring a procedure, in the absence of any other infection. Patients with definite or strongly suspected IPN were included in the IPN group. The other patients were included in the non-IPN group, which was managed conservatively.

Statistics

Baseline characteristics of the overall population were expressed as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables, as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous data and in the case of abnormal distributions as median with interquartile range (IQR; 25th–75th percentile).

For the comparison between IPN and non-IPN patients, only patients alive after the first week were analysed. To compare baseline characteristics between IPN and non-IPN patients, Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney or Student tests were used for continuous variables, and Pearson χ2 or exact Fisher tests were used for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to predict possible factors associated with IPN, (age, gender, body mass index (BMI), CTSI, PSMVT, and OF). All variables entered into the model were recorded before the diagnosis of IPN and had a p value of 0.2 or lower. The final set of predictors was selected via stepwise variable selection.

All tests were two tailed, and p values lower than 0.05 were considered significant. The data were analysed using Stata statistical software (Release 13. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP).

Results

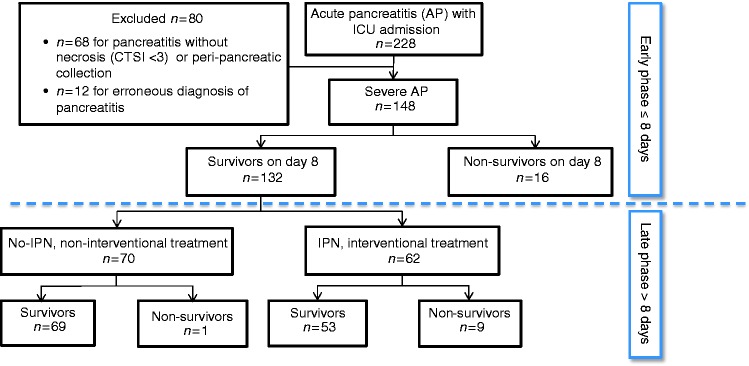

Of 228 patients admitted to our hospital during the study period with a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, 148 met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Among them, 13 were referred from local hospitals and 135 were admitted via the emergency department of the Nantes University Hospital. Table 1 reports their baseline characteristics and outcomes.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study patients.

CTSI: Computed Tomography Severity Index; ICU: intensive care unit; IPN: infected pancreatic necrosis.

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of baseline characteristics, CTSI values, and complications in survivors and non-survivors.

| Totala n = 148 | Survivors n = 122 | Non- survivors = 26 | HRcrude (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics and CTSI | |||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 54.1 (17.5) | 50.8 (16.4) | 69.5 (14.1) | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | <0.001 |

| Males, n (%) | 107 (72.3) | 91 (74.6) | 16 (61.5) | 1 | 0.02 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.3 (5.4) | 25.8 (5.2) | 30.3 (5.9) | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) | 0.005 |

| Cause of pancreatitis, n (%) | |||||

| Biliary | 48 (32.4) | 36 (29.5) | 12 (46.2) | 1 | 0.32 |

| Alcohol abuse | 64 (43.2) | 56 (45.9) | 8 (30.8) | 0.51 (0.21–1.25) | |

| Otherb | 36 (24.3) | 30 (24.6) | 6 (23.1) | 0.65 (0.24–1.73) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 20 (13.5) | 13 (10.7) | 7 (26.9) | 2.59 (1.09–6.17) | 0.03 |

| Hypertension | 58 (39.2) | 42 (34.4) | 16 (61.5) | 2.64 (1.20–5.82) | 0.02 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 38 (25.7) | 32 (26.2) | 6 (23.1) | 0.87 (0.35–2.17) | 0.77 |

| Smoking | 54 (36.5) | 49 (40.2) | 5 (19.2) | 0.42 (0.16–1.12) | 0.08 |

| Alcohol usec | 73 (49.3) | 63 (51.6) | 10 (38.5) | 0.65 (0.29–1.43) | 0.28 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 12 (8.1) | 12 (9.8) | 0 (0) | – | – |

| SAPS II, mean (SD) | 38.1 (19.7) | 33.5 (18.5) | 52 (16.7) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.001 |

| CTSI, mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.4) | 5.5 (2.2) | 7.7 (2.2) | 30.7 (5.1–183.5) | <0.001 |

| Complications, n (%) | |||||

| No OF | 26 (17.6) | 26 (21.3) | 0 (0) | 1 | |

| One or two OFs | 60 (40.5) | 60 (49.2) | 0 (0) | – | |

| ≥3 OFs | 62 (41.9) | 36 (29.5) | 26 (100) | – | |

| Persistent OF (>48 hours) | 63 (42.6) | 44 (36.1) | 19 (73.1) | 3.84 (1.61–9.14) | 0.002 |

| Type of persistent OF, n (%): | |||||

| Respiratory failure | 93 (62.8) | 68 (55.7) | 25 (96.2) | 15.92 (2.16–117.48) | 0.007 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 63 (42.6) | 44 (36.1) | 19 (73.1) | 3.79 (1.59–9.02) | 0.003 |

| ARDS | 23 (15.5) | 13 (10.7) | 10 (38.5) | 3.81 (1.72–8.40) | 0.001 |

| Circulatory failure | 62 (41.9) | 36 (29.5) | 26 (100) | – | <0.001 |

| Pressor aminesd | 49 (33.1) | 30 (24.6) | 19 (73.1) | 6.07 (2.55–14.43) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 66 (44.6) | 40 (32.8) | 26 (100) | – | <0.001 |

| RRT | 25 (16.9) | 12 (9.8) | 13 (50) | 5.89 (2.72–12.71) | <0.001 |

| PSMVT, n (%) | 76 (51.7) | 59 (48.4) | 17 (68) | 1.94 (0.84–4.51) | 0.12 |

| Perforation of hollow organ, n (%) | 5 (3.4) | 4 (3.3) | 1 (3.8) | 1.01 (0.14–7.50) | 0.99 |

| Bowel ischaemia, n (%) | 7 (4.7) | 2 (1.6) | 5 (19.2) | 6.65 (2.48–17.84) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding, n (%) | 13 (8.8) | 10 (8.2) | 3 (11.5) | 1.24 (0.37–4.14) | 0.72 |

| Intervention for infected pancreatic necrosise, n (%) | 64 (43.2) | 53 (43.4) | 11 (42.3) | 0.84 (0.38–1.83) | 0.66 |

| Surgical necrosectomy, n (%) | 36 (24.3) | 26 (21.3) | 10 (38.5) | 1.79 (0.81–3.94) | 0.15 |

HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; BMI: body mass index; IQR: interquartile range; SAPS II: Simplified Acute Physiology Score version II18 determined 24 hours after intensive care unit admission; CTSI: Computed Tomography Severity Index, which can range from 0 to 10 and was ≥ 3 in all study patients; OF: organ failure; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; RRT: renal replacement therapy; PSMVT: portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis.

Of the 148 study patients, 16 died during the first week; of the remaining 132 patients, 62 did and 70 did not develop infected pancreatic necrosis.

Other causes of pancreatitis: hypertriglyceridemia, unknown, drug-induced causes, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, traumatic.

Alcohol consumption > 20 g/day in women and 30 g/day in men.

Pressor amines: Pressor amines initiate because of persisting hypotension with mean blood pressure <65 mmHg despite adequate fluid resuscitation >40 ml/kg.

Radiological, endoscopical and surgical interventions.

Comparison of patients with and without IPN

Of the 132 patients alive after the first week, 70 did not have IPN and required no drainage or open surgery. The other 62 patients had definite or strongly suspected IPN and required minimally invasive interventions and/or open surgery.

At baseline, patients who subsequently developed IPN were older, more often had alcohol abuse, had greater acute illness severity as assessed by the Simplified Acute Physiology Score version II,18 and had higher CTSI values (Table 2). OF (renal, respiratory, and/or cardiovascular) and persistent OF were more common in patients with than without IPN (Table 2). Late mortality was significantly higher in the group with than without IPN (14.5% vs. 1.4% respectively; p = 0.001). ICU length of stay and total hospital length of stay were longer in the group with than without IPN (34.7 ± 34.9 days vs. 8.4 ± 7.3 days; p < 0.001 and 67.5 ± 42 days vs. 17.2 ± 12.7 days, p < 0.001, respectively). By univariate analysis, PSMVT was significantly associated with IPN (47/62 (75.8%) patients with IPN vs. 20/70 (28.6%) without IPN, p < 0.001). Bleeding, hollow organ perforation, and bowel ischaemia were also more common in the IPN group (Table 2). By multivariate analysis, factors significantly associated with IPN were acute pancreatitis due to causes other than biliary disease and alcohol abuse, higher number of OFs, and PSMVT (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and incidence of organ failure and other complications in patients with and without infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN).

| Totala n = 132 | No-IPN n = 70 | IPN n = 62 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 51.7 (16.6) | 48.6 (16.3) | 55.3 (16.3) | 0.02 |

| Males, n (%) | 99 (75) | 48 (68.6) | 51 (82.3) | 0.07 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.1 (5.4) | 25.5 (5.4) | 26.8 (5.4) | 0.19 |

| Cause of pancreatitis, n (%) | ||||

| Biliary | 41 (31.1) | 20 (28.6) | 21 (33.9) | 0,11 |

| Alcohol abuse | 59 (44.7) | 37 (52.9) | 22 (35.5) | |

| Otherb | 32 (24.2) | 13 (18.6) | 19 (30.6) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 16 (12.1) | 6 (8.6) | 10 (16.1) | 0.18 |

| Hypertension | 46 (34.8) | 20 (28.6) | 26 (41.9) | 0.11 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 32 (24.2) | 16 (22.9) | 16 (25.8) | 0.69 |

| Smoking | 51 (38.6) | 30 (42.9) | 21 (33.9) | 0.29 |

| Alcohol usec | 68 (51.5) | 42 (60) | 26 (41.9) | 0.04 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 12 (9.1) | 7 (10) | 5 (8.1) | 0.7 |

| SAPS II, mean (SD) | 35.2 (18.4) | 25 (18.2) | 40 (16.6) | <0.001 |

| CTSI, mean (SD) | 5.6 (2.2) | 5 (1.8) | 6.3 (2.5) | 0.01 |

| Complications, n (%) | ||||

| No OF | 26 (19.7) | 23 (32.9) | 3 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| One or two OFs | 60 (45.4) | 39 (55.7) | 21 (33.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥3 OFs | 46 (34.8) | 8 (11.4) | 38 (61.3) | <0.001 |

| Persistent OF > 48 hours | 53 (40.2) | 13 (18.6) | 40 (64.5) | <0.001 |

| Type of persistent OF, n (%): | ||||

| Respiratory failure | 78 (59.1) | 23 (32.9) | 55 (88.7) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 53 (40.2) | 10 (14.3) | 43 (69.4) | <0.001 |

| Circulatory failure | 46 (34.8) | 14 (20) | 32 (51.6) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 50 (37.9) | 16 (22.9) | 34 (54.8) | <0.001 |

| PSMVT, n (%) | 67 (50.8) | 20 (28.6) | 47 (75.8) | <0.001 |

| Perforation of hollow organ, n (%) | 5 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (8.1) | 0.02 |

| Bowel ischaemia, n (%) | 4 (3) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.8) | 0.34 |

| Intestinal bleeding, n (%) | 13 (9.8) | 1 (1.4) | 12 (19.4) | 0.001 |

| Hospital stay, days, mean (SD) | 40.8 (39.3) | 17.2 (12.7) | 67.5 (42.0) | <0.001 |

| ICU stay, days, mean (SD) | 25.9 [31.3] | 8.4 [7.3] | 34.7 (34.9) | <0.001 |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 10 (7.6) | 1 (1.4) | 9 (14.8) | 0.01 |

ICU: intensive care unit; IPN: infected pancreatic necrosis; BMI: body mass index; IQR: interquartile range; SAPS II: Simplified Acute Physiology Score version II determined 24 hours after ICU admission;18 CTSI: Computed Tomography Severity Index, which can range from 0 to 10 and was ≥3 in all study patients; OF: organ failure; PSMVT: portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis.

These 132 patients were those of the initial cohort of 148 patients who survived the first week; among them 62 did and 70 did not develop infected pancreatic necrosis.

Other causes of pancreatitis: hypertriglyceridemia, unknown, drug-induced causes, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, traumatic.

Alcohol consumption >20 g/day in women and 30 g/day in men.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis to identify factors associated with infected pancreatic necrosis.

| aOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Cause of pancreatitis | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 1 | 0.02 |

| Biliary | 2.43 (0.79–7.45) | |

| Othera | 5.36 (1.59–18.12) | |

| Number of OFs | ||

| None | 1 | <0.001 |

| One or two | 4.44 (1.07–18.40) | |

| ≥3 | 28.67 (6.23–131.96) | |

| PSMVT | 8.16 (3.06–21.76) | <0.001 |

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OF: organ failure; PSMVT: portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis.

Other causes of pancreatitis: hypertriglyceridemia, unknown, drug-induced causes, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, traumatic.

Mortality and outcomes

Overall, 26 (17.6%) patients died, 16 (10.8%) within the first week and 10 (6.8%) later on (Figure 1). All 26 were among the subgroup of 62 patients with three or more OFs. Causes of early death within seven days after onset of pancreatitis were bowel ischaemia (n = 4) and refractory shock with multiple OF (n = 12). Emergency laparotomy was performed in two of the patients who died within the first week. Deaths after day 7 were due to refractory abdominal bleeding (n = 2), bowel ischaemia (n = 3), and refractory shock (n = 5). Of the 10 patients who died after the first week, nine had definite or strongly suspected IPN.

Seventy-six (51.7%) of the 148 patients had PSMVT, the splenic vein being the most common site of thrombosis (62/76) (Table 1). Median time from hospital admission to PSMVT diagnosis was 11 days (3–35 days). Anticoagulant therapy was given to 39 of the 76 (51.3%) patients with PSMVT, for a median of six months (3–7.5 months). Cavernoma developed in 25/39 (68%) patients given anticoagulant therapy and in 9/18 (50%) patients not given anticoagulants (p = 0.31) (Table 4). Intra-abdominal bleeding occurred in 13/148 (8.7%) patients (Table 1), including 10 receiving effective anticoagulation. Of these 13 patients, six had a peptic ulcer, including one who required intravascular embolisation. The remaining seven patients had bleeding at sites of pancreatic necrosis or pseudocyst: Four were treated surgically and three by intravascular embolisation. Hollow organ perforation occurred in five patients and bowel ischaemia in four patients.

Table 4.

Treatment and outcomes of patients with portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis or stenosis.

| Total n = 57 | No cavernoma n = 23 | Cavernoma n = 34 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No effective systemic anticoagulation | 18 (31.6) | 9 (39.1) | 9 (26.5) | 0.31 |

| Effective systemic anticoagulation | 39 (68.4) | 14 (60.9) | 25 (73.5) |

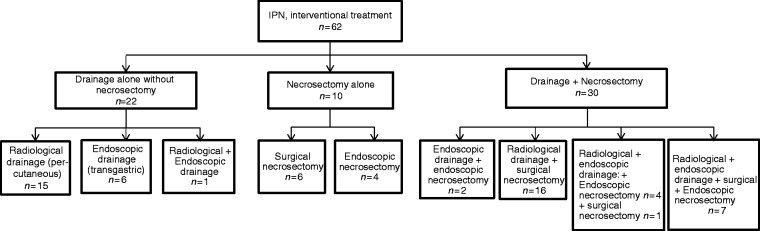

Management and description of patients with IPN

Mean time from ICU admission to the first drainage procedure was 29.3 ± 17 days. The mean number of percutaneous or endoscopic drainage procedures per patient was 3 ± 2; 22 (35%) patients required a single drainage procedure and no necrosectomy (Figure 2). Additional necrosectomy was required due to lack of improvement after drainage in 30 (48%) patients. Furthermore, 10 patients (17%) were managed with necrosectomy without prior drainage.

Figure 2.

Management strategy and details of interventions for infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN).

Of the 62 patients with IPN, 49 (79.0%) had systemic antibiotic therapy started before bacteriological sampling and drainage (Supplemental Digital Content 3). Mean antibiotic therapy duration before drainage was 8.9 ± 8.5 days. Of the 62 patients with IPN, 50 (78%) had definite IPN (Supplemental Digital Content 4) and 12 strongly suspected IPN. In the subgroup with strongly suspected IPN, eight did not have microbiological studies of pancreatic or peripancreatic material and the other four had negative cultures but had been receiving antibiotics for more than four days at the time of sampling. CT showed gas bubbles within necrotic collections in 15 (25%) patients, all of whom had definite IPN.

Discussion

In the modern era of minimally invasive approaches to infected tissues, the management and outcomes of severe acute pancreatitis in everyday practice remain matters of large uncertainty. Our study adds to the scant data on outcomes and management of IPN of patients with severe acute pancreatitis. The main findings are the independent associations linking number of OFs and PSMVT to IPN. Regarding management, our study showed that a single minimally invasive drainage procedure without necrosectomy was sufficient in one-third of patients. Percutaneous and endoscopic techniques were combined in one-fifth of patients.

The overall 17.6% mortality rate in our study is in accordance with previous work on acute necrotising pancreatitis.1,3–5 IPN developed in 41.9% of all patients admitted for (moderately) severe acute pancreatitis and in 47.0% of those who survived the first week. These rates are slightly higher than those reported previously.1,3,4,19 One possible explanation is that we included not only patients with definite IPN, but also those with strongly suspected IPN. The rationale for this strategy is that absence of, or negative results from, microbiological samples do not rule out IPN in patients on systemic antibiotics at the time of sampling. Independent risk factors for IPN in our study were multiple OF and PSMVT. Thus, the occurrence of persistent OF during the early phase of acute pancreatitis might be a risk factor of IPN. OF was associated with impairments in immune function and abnormalities in inflammatory mediators in earlier studies of acute pancreatitis.17,20,21 Whether there is a causal relationship between OF during the first week of acute pancreatitis and the subsequent development of IPN deserves assessment in prospective studies.

PSMVT was also an independent risk factor for IPN in our study. To our knowledge, a single earlier study suggests a link between PSMVT and subsequent IPN.22 PSMVT developed in 51.7% of our patients, a proportion toward the higher end of the wide previously reported range of 0.5% to 62.1%.23 This high rate in our study might be related to the definition of PSMVT as not only obstruction but also stenosis of a splanchnic vein. The potential impact of PSMVT on the course of acute pancreatitis is unknown, and whether PSMVT correlates with the severity of acute pancreatitis has not been reported. PSMVT was not associated with mortality in our study, perhaps due to insufficient statistical power. The potential association of PSMVT with mortality deserves evaluation in a larger, multicentre cohort study. Most guidelines refer to PSMVT as a radiological finding. In addition, whether PSMVT is a severity marker or an event requiring specific treatment remains unclear. There is no evidence supporting systemic anticoagulation in this situation.22–25 In our study three-fifths of patients given anticoagulant therapy after PSMVT diagnosis developed cavernoma, and the frequency of cavernoma was not different with vs. without anticoagulant therapy, in keeping with other reports.22,24,26,27 While receiving effective anticoagulation, ten patients experienced intestinal bleeding, including one who developed fatal refractory haemorrhagic shock. Anticoagulation appeared safe in two earlier studies,27,28 whereas another found a 12.3% rate of gastrointestinal bleeding.29 Our results suggest that anticoagulation, particularly in patients with IPN, should be used with caution. However, the small sample size does not allow conclusions and larger studies should address this issue specifically. In particular, the potential consequences of PSMVT on the course of severe acute pancreatitis, such as increased bacterial translocation in the event of portal system obstruction, remain unknown. Last, we were unable to evaluate the potential impact of preventive anticoagulation because nearly all the patients received this treatment at various times during their hospital stay. The number of patients without preventive anticoagulation was thus too small for a statistical comparison.

Mortality after the first week was considerably higher in the IPN group, in line with previous studies.1,3,7 The main causes of death in our study were refractory shock and multiple OF, as previously described.30 However, bowel ischaemia was responsible for one-fourth of early deaths and one-third of late deaths. Bowel ischaemia is rarely reported as a complication of acute pancreatitis.31 However, in an autopsy study of 48 patients with acute pancreatitis, bowel ischaemia was found in 27% of cases.32 Bowel ischaemia can be difficult to diagnose and may be associated to multiple OF even in the absence of vessel occlusion.31 Patients must be closely monitored to ensure the early diagnosis of this life-threatening complication. Efforts to improve pathogenic knowledge and the treatment of bowel ischaemia might decrease mortality in severe acute pancreatitis.

The main limitation of this study is the retrospective observational design, which is a source of bias and precludes assessments of causal relationships. Another limitation is the lack of a standardised therapeutic algorithm, which may have induced bias via several mechanisms, such as the choice of one method over another for logistic (i.e. operating room availability) rather than medical reasons. Also, the procedures and types of devices were at the discretion of the interventional physicians. The management of IPN is not standardised and varies widely across centres and physicians. No data are available for determining the optimal duration of antibiotic therapy and prospective studies of this issue are needed to provide a basis for guidelines.7 Laboratory parameters of potential prognostic significance were not available for our study, due to the retrospective design. C-reactive protein (CRP) has been reported to have prognostic significance in acute pancreatitis.13 However, in critically ill patients, CRP is known to have very little diagnostic or prognostic relevance. Last, the single-centre design of our study may limit the general applicability of our findings. However, our hospital serves a large population of 1.4 million, and the size of our cohort was substantial compared to previous studies.15

In conclusion, in this study of everyday practice, nearly half the patients admitted to the ICU for moderately severe or severe acute pancreatitis developed IPN, which was associated with higher mortality and complication rates. In most cases, IPN was treated with minimally invasive techniques. Finally, PSMVT and multiple OF were independently associated with the development of IPN. These data suggest that early aggressive management of OF might decrease the risk of IPN and its complications, and early PSMVT detection and management should be investigate in further studies.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for Risk factors and outcomes of infected pancreatic necrosis: Retrospective cohort of 148 patients admitted to the ICU for acute pancreatitis by Charlotte Garret, Matthieu Péron, Jean Reignier, Aurélie Le Thuaut, Jean-Baptiste Lascarrou, Frédéric Douane, Marc Lerhun, Isabelle Archambeaud, Noëlle Brulé, Cédric Bretonnière, Olivier Zambon, Laurent Nicolet, Nicolas Regenet, Christophe Guitton and Emmanuel Coron in United European Gastroenterology Journal

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to A Wolfe, MD, for assistance in preparing and reviewing the manuscript, and to Stephane Corvec, MD, for his help preparing the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not–for–profit sectors.

Informed consent

French legislation on studies of anonymised retrospective data does not require informed consent.

Ethics approval

The ethics committee of the French Intensive Care Society approved this study (#CE SRLF16-09). ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT03253861.

References

- 1.Forsmark CE, Vege SS, Wilcox CM. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1972–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zerem E. Treatment of severe acute pancreatitis and its complications. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 13879–13892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis – 2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013; 62: 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1491–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Brunschot S, Hollemans RA, Bakker OJ, et al. Minimally invasive and endoscopic versus open necrosectomy for necrotising pancreatitis: A pooled analysis of individual data for 1980 patients. Gut. Epub ahead of print 3 August 2017. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrov MS, Shanbhag S, Chakraborty M, et al. Organ failure and infection of pancreatic necrosis as determinants of mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabo A, Goussous N, Sardana N, et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis: a review of multidisciplinary management. JOP 2015; 16: 125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollemans RA, Bollen TL, van Brunschot S, et al. Predicting success of catheter drainage in infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Ann Surg 2016; 263: 787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, et al. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome. Gastroenterology 2011; 141: 1254–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pezzilli R, Zerbi A, Campra D, et al. Consensus guidelines on severe acute pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis 2015; 47: 532–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2013; 13(4 Suppl 2): e1–e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokoe M, Takada T, Mayumi T, et al. Japanese guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: Japanese Guidelines 2015. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2015; 22: 405–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riché FC, Cholley BP, Laisné MJ, et al. Inflammatory cytokines, C reactive protein, and procalcitonin as early predictors of necrosis infection in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgery 2003; 133: 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rau BM, Kemppainen EA, Gumbs AA, et al. Early assessment of pancreatic infections and overall prognosis in severe acute pancreatitis by procalcitonin (PCT): a prospective international multicenter study. Ann Surg 2007; 245: 745–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji L, Lv JC, Song ZF, et al. Risk factors of infected pancreatic necrosis secondary to severe acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2016; 15: 428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, et al. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med 1995; 23: 1638–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, et al. Timing and impact of infections in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2009; 96: 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 1993; 270: 2957–2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isenmann R, Rünzi M, Kron M, et al. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment in patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: 997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer J, Rau B, Gansauge F, et al. Inflammatory mediators in human acute pancreatitis: clinical and pathophysiological implications. Gut 2000; 47: 546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halonen KI, Pettilä V, Leppäniemi AK, et al. Multiple organ dysfunction associated with severe acute pancreatitis. Crit Care Med 2002; 30: 1274–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Ke L, Tong Z, et al. Risk factors and outcome of splanchnic venous thrombosis in patients with necrotizing acute pancreatitis. Thromb Res 2015; 135: 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu W, Qi X, Chen J, et al. Prevalence of splanchnic vein thrombosis in pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2015; 2015: e245460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris S, Nadkarni NA, Naina HV, et al. Splanchnic vein thrombosis in acute pancreatitis: a single-center experience. Pancreas 2013; 42: 1251–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heider TR, Azeem S, Galanko JA, et al. The natural history of pancreatitis-induced splenic vein thrombosis. Ann Surg 2004; 239: 876–880. discussion 880–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzelez HJ, Sahay SJ, Samadi B, et al. Splanchnic vein thrombosis in severe acute pancreatitis: a 2-year, single-institution experience. HPB (Oxford) 2011; 13: 860–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nadkarni NA, Khanna S, Vege SS. Splanchnic venous thrombosis and pancreatitis. Pancreas 2013; 42: 924–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Easler J, Muddana V, Furlan A, et al. Portosplenomesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with acute pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis and usually has a benign course. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butler JR, Eckert GJ, Zyromski NJ, et al. Natural history of pancreatitis-induced splenic vein thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of its incidence and rate of gastrointestinal bleeding. HPB (Oxford) 2011; 13: 839–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carnovale A, Rabitti PG, Manes G, et al. Mortality in acute pancreatitis: is it an early or a late event?. JOP 2005; 6: 438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirota M, Inoue K, Kimura Y, et al. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia and its associated intestinal gangrene in acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2003; 3: 316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi Y, Fukushima JI, Fukusato T, et al. Prevalence of ischemic enterocolitis in patients with acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 827–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for Risk factors and outcomes of infected pancreatic necrosis: Retrospective cohort of 148 patients admitted to the ICU for acute pancreatitis by Charlotte Garret, Matthieu Péron, Jean Reignier, Aurélie Le Thuaut, Jean-Baptiste Lascarrou, Frédéric Douane, Marc Lerhun, Isabelle Archambeaud, Noëlle Brulé, Cédric Bretonnière, Olivier Zambon, Laurent Nicolet, Nicolas Regenet, Christophe Guitton and Emmanuel Coron in United European Gastroenterology Journal