Abstract

Lifestyle is far more important than most physicians suppose. Dietary changes in China that have resulted from increased prosperity are probably responsible for a marked rise in coronary risk in the past several decades, accelerating in recent years. Intake of meat and eggs has increased, while intake of fruits, vegetables and whole grains has decreased. Between 2003 and 2013, coronary mortality in China increased 213%, while stroke mortality increased by 26.6%. Besides a high content of cholesterol, meat (particularly red meat) contains carnitine, while egg yolks contain phosphatidylcholine. Both are converted by the intestinal microbiome to trimethylamine, in turn oxidised in the liver to trimethylamine n-oxide (TMAO). TMAO causes atherosclerosis in animal models, and in patients referred for coronary angiography high levels after a test dose of two hard-boiled eggs predicted increased cardiovascular risk. The strongest evidence for dietary prevention of stroke and myocardial infarction is with the Mediterranean diet from Crete, a nearly vegetarian diet that is high in beneficial oils, whole grains, fruits, vegetables and legumes. Persons at risk of stroke should avoid egg yolk, limit intake of red meat and consume a diet similar to the Mediterranean diet. A crucial issue for stroke prevention in China is reduction of sodium intake. Dietary changes, although difficult to implement, represent an important opportunity to prevent stroke and have the potential to reverse the trend of increased cardiovascular risk in China.

Keywords: diet, nutrition, stroke prevention, eggs, cholesterol, mediterranean, TMAO, intestinal microbiome

When ranked in order of importance, among the interventions available to prevent stroke, the three most important are probably diet, smoking cessation and blood pressure control.1 Hypertension and smoking cessation are discussed in other papers in this issue of the journal. In this paper I discuss diet and stroke prevention.

Importance of lifestyle

Lifestyle is much more important than most physicians suppose. In the US Health Professionals study and the Nurses’ Health Study, poor lifestyle choices accounted for more than half of stroke.2 Participants who achieved all five healthy lifestyle choices—not smoking, moderate intake of alcohol, a body mass index <25, daily exercise for 30 min and a healthy diet score in the top 40%—had an 80% reduction of stroke compared with participants who achieved none. In a study in Swedish women, all five choices reduced the risk of stroke by 60%.3 Among Swedish men with hypertension and dyslipidaemia, all five healthy behaviours reduced coronary events by more than 80%.4

Harmful dietary trends

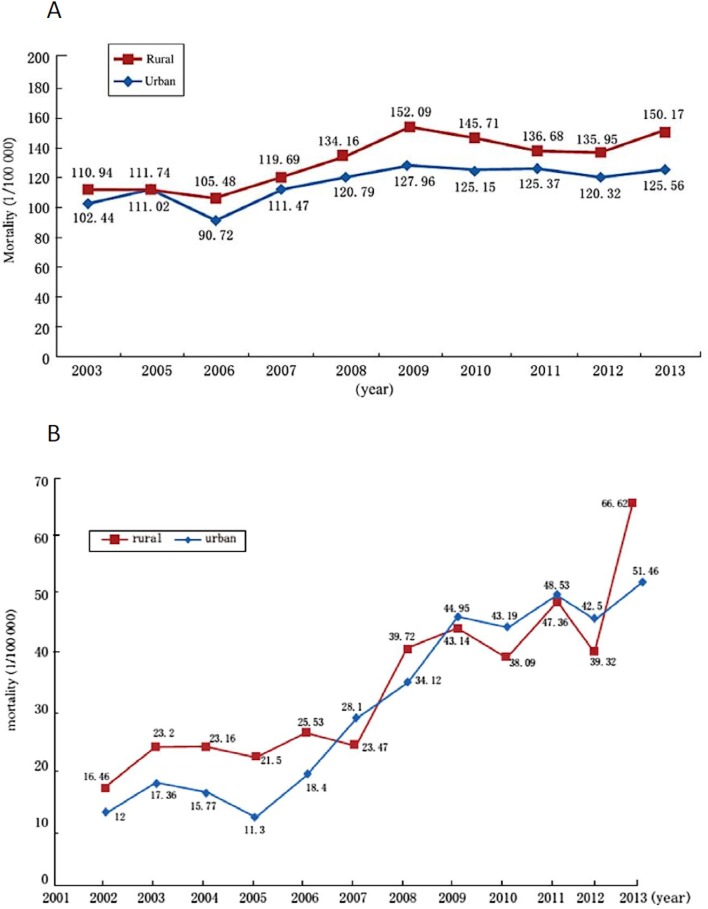

In the USA, the worst of the lifestyle choices is diet. The American Heart Association statistical report of 2015 indicated that only 0.1% of Americans consumed a healthy diet and only 8.3% consumed a moderately healthy diet.5 In China, the consumption of meat and eggs has increased markedly in recent years, while consumption of whole grains, vegetables and fruit has declined.6 This probably accounts for much of the increase in fasting cholesterol levels7 and in coronary disease6 8 in China at the same time. Stroke is much more common than myocardial infarction in China, and in the past most strokes were due to hypertension. What has happened in China is that myocardial infarctions have increased markedly, with a much smaller increase in stroke. Between 2003 and 2013, stroke mortality per 100 000 in urban people increased from 102.44 to 125.56 (a 26.6% increase), while coronary mortality increased from 16.46/100 000 urban people to 51.46/100 000 (a 213% increase)6 (figure 1). Undoubtedly strokes due to large artery disease in China will have increased in proportion during that time, the opposite of what was seen in a Canadian stroke clinic population between 2002 and 2012.9

Figure 1.

Trends in cardiovascular mortality in China, 2003–2013. (A) Increase in mortality from myocardial infarction and (B) increase in mortality from stroke. Myocardial infarction increased much more steeply than stroke, probably in large part because of changes in diet in China over time with increased prosperity. Strokes in China are largely due to hypertension, whereas myocardial infarctions are more closely related to intake of meat and egg yolk. (Reproduced with permission from the European Heart Journal, Weiwei et al. 6)

Trends in dietary guidelines

In the past, a low-fat diet was recommended to reduce cardiovascular risk; however, as pointed out by Willett and Stampfer,10 the low-fat diet was essentially ‘pulled from thin air’ by a committee trying to imagine a diet that would lower fasting levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Recent dietary guidelines tend to recommend a dietary pattern, rather than specifying limits to intake of particular foods or nutrients. Increasingly, guidelines are recommending reduction of intake of animal fat and increased intake of fruits and vegetables—a more plant-based diet. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet11 emphasised fruits, vegetables and low-fat dairy foods with reduced intake of saturated fat, total fat and cholesterol; it included whole grains, poultry, fish and nuts, and was reduced in red meat, sweets and sugar-containing beverages. This appears to be similar to the Mediterranean diet, but there are important differences: the Mediterranean diet also emphasises whole grains, fruits and vegetables, but it is high in beneficial oils (olive and canola), low in dairy products and contains much less animal flesh. In a retrospective article,12 Ancel Keys, the leader of the Seven Countries Study, described it as follows: ‘The heart of this diet is mainly vegetarian, and differs from American and northern European diets in that it is much lower in meat and dairy products and uses fruit for dessert’.

Evidence for the Mediterranean diet

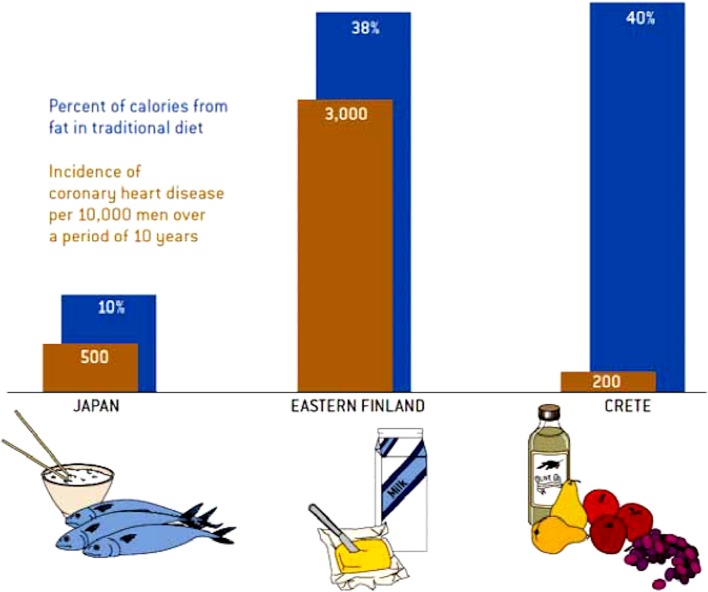

The diet with the best evidence for stroke prevention is the Mediterranean diet from Crete. In the Seven Countries Study, it was discovered that coronary risk in Crete was 1/15th that in Finland and only 40% of that in Japan.10 In a retrospective article, Ancel Keys described it as ‘a mainly vegetarian diet…favoring fruit for dessert’. The diet is not a low-fat diet; it is a low glycaemic/high-fat diet with 40% of calories from beneficial fats such as olive and canola oil, and high in whole grains, fruits, vegetables and legumes (peas, lentils, beans, nuts and so on) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Mediterranean diet. The Mediterranean diet is a high-fat/low glycaemic diet with 40% of calories from fat; however, the fat is mainly beneficial oils such as olive and canola. Among men in the Seven Countries Study, the coronary risk in Crete was only 1/15th of that in Finland, where most of the fat was saturated fat (accompanied by cholesterol), and 40% of that in Japan, where the diet is a low-fat diet favouring fish. (Reproduced from Willet and Stampfer.10)

n secondary prevention, in the Lyon Diet Heart Study,13 the Mediterranean diet was approximately twice as efficacious as was simvastatin in the contemporaneous Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S).14 Both studies enrolled patients who had survived a myocardial infarction; in the Lyon Diet Heart Study, the Mediterranean diet reduced coronary events and stroke by more than 70% in 4 years; in the 4S trial, simvastatin reduced recurrent coronary events by 40% in 6 years. In primary prevention, in the Spanish Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet (PREDIMED) study,15 a low-fat diet was compared with two Mediterranean diet arms: one fortified with olive oil, while the other fortified with mixed nuts. Both versions of the Mediterranean diet significantly reduced cardiovascular events; the nut-fortified version reduced stroke by 47% in 5 years.

Problems with low-fat diets

In recent years there has been much said about how the dietary villain is not cholesterol and egg yolk but sugar, and some have mistakenly blamed the Mediterranean diet for the low-fat diet that has resulted in a marked increase in carbohydrate intake, with increases in diabetes and obesity.16 However, the low-fat diet did not result from the discovery of the Mediterranean diet. With its high fat content (40% of calories from fat, mainly olive oil)10 and emphasis on whole grains, the Mediterranean diet is actually a low glycaemic diet.

The result of this discussion has been a widespread and popular, but entirely mistaken, move to increased use of low-carbohydrate (low-carb) diets, with a high intake of cholesterol and animal fat. This is disastrous, and to a great extent due to propaganda of the food industry.17 Like the sugar industry18 the meat and egg industries spend hundreds of millions of dollars on propaganda, unfortunately with great success.19–21 Box 1 provides links to information about this issue.

Box 1. Links to videos about egg industry propaganda.

http://nutritionfacts.org/video/eggs-and-cholesterol-patently-false-and-misleading-claims/.

http://nutritionfacts.org/video/eggs-vs-cigarettes-in-atherosclerosis/.

http://nutritionfacts.org/video/egg-cholesterol-in-the-diet/.

http://nutritionfacts.org/video/how-the-egg-board-designs-misleading-studies/.

An Israeli diet study22 provided perhaps the best evidence that the Cretan Mediterranean diet is actually better than a low-carb diet for diabetes and insulin resistance. Overweight residents in an institution, who obtained their meals from the cafeteria, were randomised to a low-fat diet, a low-carb diet or the Mediterranean diet. Adherence was 95% at 1 year and 86% at 2 years, unusually good for dietary studies. Weight loss was identical on the low-carb and Mediterranean diet, and both were significantly better than the low-fat diet. Among participants with diabetes, fasting glucose, fasting insulin levels and insulin resistance were clearly the best on the Mediterranean diet.22

Propaganda of the egg industry and the red meat industry

Following an exposé of the propaganda of the sugar industry in which the ‘smoking gun’ was unearthed in archives,18 Nestle17 commented on the attempts of the food industry in general to influence public beliefs. I commented on the egg industry and the meat industry.19

The two pillars of the egg industry propaganda are a red herring and a half-truth. The red herring is a misplaced focus on the effects of diet on fasting lipids. Diet is not about the fasting state; it is about the postprandial state.23 24 For ~4 hours after a high-fat/high-cholesterol meal, there is marked oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and arterial inflammation.25

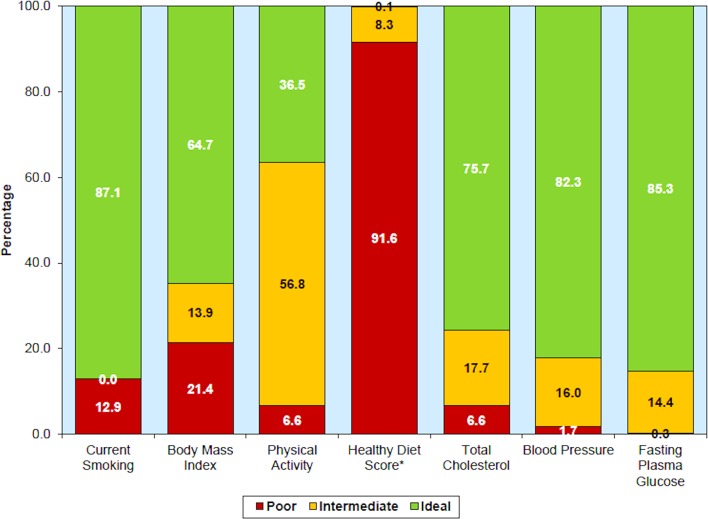

The half-truth is the slogan ‘eggs can be part of a healthy diet for healthy people’. This is based on two US studies that did not find harm from egg consumption except among participants who became diabetic, in whom an egg a day ‘only’ doubled coronary risk.26 27 However, as discussed above, the US diet is so bad that it is difficult to show harm from any component (figure 3). In Greece, however, where the Mediterranean diet is the norm, an egg a day increased coronary risk fivefold among persons with diabetes, and even 10 g per day of egg (a sixth of a large egg) increased coronary risk by 54%.28 Egg consumption also increases the risk of diabetes.29

Figure 3.

Diet is the worst of the risk issues in the USA. Prevalence (unadjusted) estimates for poor, intermediate and ideal cardiovascular health for each of the seven metrics of cardiovascular health in the American Heart Association 2020 goals, US children aged 12–19 years, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2012. *Healthy diet score data reflect 2009–2010 NHANES data. (Reproduced with permission from Wolters Kluwer, Mozaffarian et al. 5)

The 2016 US guideline

In 2016, when the new US dietary guideline was released, there were headlines trumpeting ‘It’s OK to eat cholesterol again; the new guideline says so’. But it was not true. In the first paragraph, the press release said that there were insufficient data to recommend a specific limit to cholesterol intake, as in the past (300 mg/day for healthy people or 200 mg/day for those at risk of vascular disease).30 However, the second paragraph said: ‘However, cholesterol intake should be as low as possible within the recommended eating pattern’ (which resembles a Mediterranean diet). The paragraphs should have been reversed. There are still good reasons to recommend a cholesterol intake below 200 mg/day (less than one large egg yolk), and other guidelines do so.31

It is little understood that ‘people at risk of vascular disease’ essentially means everyone who aspires to achieve a healthy old age.32 A 20-year-old man might think he can eat eggs and smoke with impunity, because his stroke or myocardial infarction are 45 years in the future. But why would he want to bring it on sooner?33

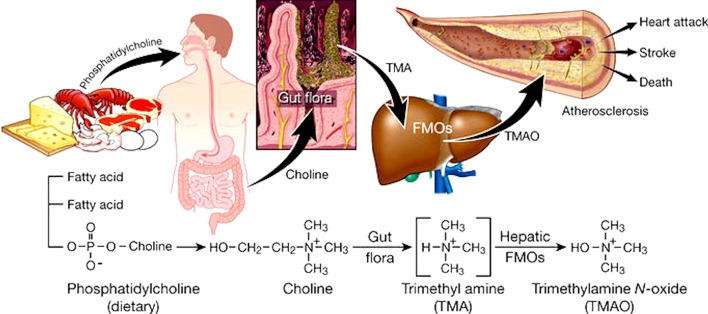

Effects of the intestinal microbiome

Although dietary cholesterol does not increase fasting lipid levels by much, it clearly does increase coronary mortality.34 35 However, there is increasing recognition of the importance of the intestinal microbiome.36 While cholesterol content is essentially the same for any kind of animal flesh, red meat has more saturated fat, and has ~4 times as much carnitine as chicken or fish. Carnitine from red meat37 and phosphatidylcholine from egg yolk37 are converted by the intestinal bacteria to trimethylamine, in turn oxidised in the liver to trimethylamine n-oxide (TMAO) (figure 4). TMAO causes atherosclerosis in animal models,37 and in patients undergoing coronary angiograms plasma levels in the top quartile of TMAO levels after a test dose of two hard-boiled eggs predicted a 2.5-fold increase in the 3-year risk of stroke, myocardial infarction or vascular death.38 A 12-ounce Hardee’s Monster Thickburger39 contains 265 mg of cholesterol and 320 mg of carnitine. The yolk of a 65 g egg contains 237 mg of cholesterol and 250 mg of carnitine, so two egg yolks are worse than the 12-ounce burger. Patients at risk of stroke should avoid red meat and egg yolk.

Figure 4.

Trimethylamine n-oxide (TMAO) is produced by the intestinal bacteria from phosphatidylcholine. Carnitine (largely from red meat) and phosphatidylcholine (largely from egg yolk) are converted by the intestinal bacteria to trimethylamine, which in turn is oxidised by the liver to TMAO. TMAO causes atherosclerosis in animal models and markedly increases the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality, particularly in persons with renal impairment. It also accelerates decline of renal function. (Permission requested to reproduce from Wang et al. 58) FMO, flavin-containing monooxygenase.

Besides TMAO, there are other toxic metabolites produced by the intestinal bacteria from amino acids, including P-cresyl sulfate, hippuric acid, indoxyl sulfate, P-cresyl glucuronide, phenyl acetyl glutamine and phenyl sulfate. These toxic metabolites of the intestinal microbiome are renally excreted, so they may be termed ‘Gut-derived Uremic Toxins’ (GDUT). Their blood levels are very high in patients with renal failure. Other uraemic toxins that have high plasma levels in renal failure are thiocyanate, asymmetric dimethylarginine and homocysteine. Homocysteine accounts for only ~20% of the effect of renal impairment on carotid plaque burden40; we hypothesised40 that GDUT may account for much of the very high risk associated with renal failure.41 Renal function declines linearly with age, and by age 80 the average estimated glomerular filtration rate in patients attending a stroke prevention clinic is below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.40 We have evidence that even moderate renal impairment significantly increases plasma levels of the GDUT (submitted for publication). This means that persons with renal impairment, including most elderly patients, should avoid red meat and egg yolk.

Coffee and tea

The role of regular consumption of tea or coffee on cardiovascular risk has not been tested in randomised controlled trials. There is moderately good evidence that consumption of coffee and tea reduces risk of myocardial infarction, but little mention of stroke in that body of literature. It seems likely that reduction of myocardial infarction would be associated with reduction of stroke risk.

Coffee consumption has been controversial for many years. An early report from the Framingham Study indicated that tea, but not coffee, reduced the risk of myocardial infarction.42 For both tea and coffee there are two issues to be considered: the effects of caffeine and the effects of antioxidants. Some evidence that caffeine in coffee may be harmful came from a study in which slow metabolisers of caffeine (because of a variant of the CYP1A2 genotype) appeared to have increased the risk of myocardial infarction.43 A recent meta-analysis indicates that consuming 3–5 cups per day of coffee reduces cardiovascular risk.44 As both decaffeinated and regular coffee appear to have equal benefit with regard to reduction of cardiovascular disase and diabetes,45 46 it seems likely that benefits of coffee are from bioflavonoids.

Both green tea and other forms of tea reduce cardiovascular risk. Green tea lowers blood pressure and LDL cholesterol,47 and improves endothelial function.48 However, there are differences between green tea and black tea. A report from the Rotterdam study49 indicated that consumption of the bioflavonoids quercetin, kaempferol and myricetin may account for the reduction of myocardial infarction observed with black tea consumption. The cardiovascular benefit of green tea, on the other hand, has been associated with catechins.50

Consumption of both tea and coffee appears to be beneficial. It is not known if consuming both tea and coffee would be more beneficial. Since consumption of these beverages is a personal preference with cultural differences across countries, it seems unlikely that physicians would prescribe one or the other.

Consumption of alcohol

Consumption of alcohol is a two-edged sword. Moderate consumption of alcohol (<9 standard drinks per week for women or 14 for men)51 appears to reduce cardiovascular risk compared with drinking no alcohol,52 whereas heavy consumption increases risk, particularly for stroke, and particularly for intracerebral haemorrhage. In a recent large population-based study (n=114 859, followed for 6 years)52: ‘Heavy drinking (exceeding guidelines) conferred an increased risk of presenting with unheralded coronary death (1.21, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.35), heart failure (1.22, 1.08 to 1.37), cardiac arrest (1.50, 1.26 to 1.77), transient ischaemic attack (1.11, 1.02 to 1.37), ischaemic stroke (1.33, 1.09 to 1.63), intracerebral haemorrhage (1.37, 1.16 to 1.62), and peripheral arterial disease (1.35; 1.23 to 1.48), but a lower risk of myocardial infarction (0.88, 0.79 to 1.00) or stable angina (0.93, 0.86 to 1.00)’. Two likely mechanisms are that heavy alcohol consumption may increase the risk of atrial fibrillation and also increase blood pressure,51 in some individuals more than others. Moderate alcohol consumption does not appear to increase the risk of atrial fibrillation.53

Dietary sodium

A major dietary issue in China is sodium intake. The relationship of sodium intake to hypertension in China was reviewed in 2014.54 Most of the sodium (~75%) in the diet comes from soy sauce and added condiments. The major cause of stroke in China is hypertension, and hypertension is poorly controlled,55 in part because of the cost of medication.56 Restriction of sodium intake has the potential to improve blood pressure control, particularly in patients with higher blood pressures,11 at no financial cost. Patients should be encouraged to use light soy sauce in limited quantities and increase other approaches to flavouring food, such as lemon juice, vinegar, ginger, spices, herbs and hot peppers. Again, such changes would represent a cultural change that would be a challenge to implement.

So what diet would be recommended for patients at risk of stroke?

Patients at risk of stroke should limit their intake of animal flesh, avoiding red meat and egg yolk. They should have a high intake of beneficial oils such as olive and canola, whole grains, vegetables, fruits and legumes. Egg white is a good source of protein, so omelettes, frittatas and egg salad sandwiches made with egg whites or with egg white-based substitutes are a good substitute for a meat-based meal. Box 2 summarises my recommendations for helping patients learn to make a healthy diet enjoyable. The recipe booklet that I give to my patients can be downloaded from http://www.imaging.robarts.ca/SPARC/.

Box 2. Dietary recommendations for patients at risk of stroke.

No egg yolks: use egg whites, egg beaters, egg creations or similar substitutes.

Flesh of any animal: a serving the size of the palm of the hand or less, ~every other day (or half that daily).

Seldom red meat, mainly fish and chicken.

High intake of olive oil and canola oil.

Only whole grains.

High intake of vegetables, fruit and legumes.

Avoid deep-fried foods and hydrogenated oils (trans fats).

Avoid sugar and refined grains, and limit potatoes.

To accomplish this, patients need to think of their meatless day not as a punishment day, but as a gourmet cooking class day: ‘Having fun learning how to make healthy eating tasty’.57

A measure that should be considered in China would be converting the population to whole grain rice instead of polished rice. This would no doubt be extremely difficult, but it would reduce the risk of diabetes, stroke and myocardial infarction.

Conclusion

Diet is an important part of stroke prevention. Reducing sodium intake, avoiding egg yolks, limiting the intake of animal flesh (particularly red meat), and increasing the intake of whole grains, fruits, vegetables and lentils would contribute importantly to reversing the trend to increased cardiovascular risk in China.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Guest chief editor: J David Spence

References

- 1. Hackam DG, Spence JD. Combining multiple approaches for the secondary prevention of vascular events after stroke: a quantitative modeling study. Stroke 2007;38:1881–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chiuve SE, Rexrode KM, Spiegelman D, et al. . Primary prevention of stroke by healthy lifestyle. Circulation 2008;118:947–54. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.781062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larsson SC, Akesson A, Wolk A. Healthy diet and lifestyle and risk of stroke in a prospective cohort of women. Neurology 2014;83:1699–704. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akesson A, Larsson SC, Discacciati A, et al. . Low-risk diet and lifestyle habits in the primary prevention of myocardial infarction in men: a population-based prospective cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1299–306. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. . Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;131:e29–322. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weiwei C, Runlin G, Lisheng L, et al. . Outline of the report on cardiovascular diseases in China, 2014. Eur Heart J Suppl 2016;18(Suppl F):F2–11. 10.1093/eurheartj/suw030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reddy KS. Cardiovascular disease in non-Western countries. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2438–40. 10.1056/NEJMp048024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Critchley JA, Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2003;290:86–97. 10.1001/jama.290.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bogiatzi C, Hackam DG, McLeod AI, et al. . Secular trends in ischemic stroke subtypes and stroke risk factors. Stroke 2014;45:3208–13. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Rebuilding the food pyramid. Sci Am 2003;288:64–71. 10.1038/scientificamerican0103-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Juraschek SP, Miller ER, Weaver CM, et al. . Effects of sodium reduction and the DASH diet in relation to baseline blood pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2841–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keys A. Mediterranean diet and public health: personal reflections. Am J Clin Nutr 1995;61(6 Suppl):1321S–3. 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1321S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Renaud S, de Lorgeril M, Delaye J, et al. . Cretan Mediterranean diet for prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr 1995;61(6 Suppl):1360S–7. 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1360S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Group SSSS. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. . Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1279–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spence JD. Are some diets “mass murder”? Mediterranean diet is not to blame for increased carbohydrate intake. BMJ 2015;350:h613 10.1136/bmj.h613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nestle M. Food industry funding of nutrition research: the relevance of history for current debates. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1685–6. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kearns CE, Schmidt LA, Glantz SA. Sugar industry and coronary heart disease research: a historical analysis of internal industry documents. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1680–5. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spence JD. Red meat intake and cardiovascular risk: it’s the events that matter; not the risk factors. J Public Health Emerg 2017;1:53 10.21037/jphe.2017.05.05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greger M. False and misleading claims by egg marketers: secondary false and misleading claims by egg marketers. 2013. http://nutritionfacts.org/video/eggs-and-cholesterol-patently-false-and-misleading-claims/ (accessed 20 May 2015).

- 21. Greger M. How the Egg Board Designs Misleading Studies : Secondary How the Egg Board Designs Misleading Studies. 2013. http://nutritionfacts.org/video/how-the-egg-board-designs-misleading-studies/ (accessed 20 May 2015).

- 22. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. . Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med 2008;359:229–41. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spence JD. Fasting lipids: the carrot in the snowman. Can J Cardiol 2003;19:890–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spence JD, Jenkins DJ, Davignon J. Dietary cholesterol and egg yolks: not for patients at risk of vascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2010;26:e336–e339. 10.1016/S0828-282X(10)70456-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ghanim H, Abuaysheh S, Sia CL, et al. . Increase in plasma endotoxin concentrations and the expression of Toll-like receptors and suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 in mononuclear cells after a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal: implications for insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 2009;32:2281–7. 10.2337/dc09-0979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, et al. . A prospective study of egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in men and women. JAMA 1999;281:1387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qureshi AI, Suri FK, Ahmed S, et al. . Regular egg consumption does not increase the risk of stroke and cardiovascular diseases. Med Sci Monit 2007;13:CR1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trichopoulou A, Psaltopoulou T, Orfanos P, et al. . Diet and physical activity in relation to overall mortality amongst adult diabetics in a general population cohort. J Intern Med 2006;259:583–91. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Djoussé L, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, et al. . Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. Diabetes Care 2009;32:295–300. 10.2337/dc08-1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Healthy people 2000: National health promotion and disease prevention objectives. United States Department of Health and Human Services, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Catapano AL, Reiner Z, De Backer G, et al. . ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Atherosclerosis 2011;217:3–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilkins JT, Ning H, Berry J, et al. . Lifetime risk and years lived free of total cardiovascular disease. JAMA 2012;308:1795–801. 10.1001/jama.2012.14312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spence JD, Jenkins DJ, Davignon J. Egg yolk consumption and carotid plaque. Atherosclerosis 2012;224:469–73. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shekelle RB, Shryock AM, Paul O, et al. . Diet, serum cholesterol, and death from coronary heart disease. The Western Electric study. N Engl J Med 1981;304:65–70. 10.1056/NEJM198101083040201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kushi LH, Lew RA, Stare FJ, et al. . Diet and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. The Ireland-Boston Diet-Heart Study. N Engl J Med 1985;312:811–8. 10.1056/NEJM198503283121302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spence JD. Effects of the intestinal microbiome on constituents of red meat and egg yolks: a new window opens on nutrition and cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:150–1. 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, et al. . Intestinal microbiota metabolism of l-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med 2013;19:576–85. 10.1038/nm.3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, et al. . Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1575–84. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hardees. Secondary. http://www.hardees.com/menu/nutritional_calculator

- 40. Spence JD, Urquhart BL, Bang H. Effect of renal impairment on atherosclerosis: only partially mediated by homocysteine. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016;31:937–44. 10.1093/ndt/gfv380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. . Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 2013;382:339–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60595-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sesso HD, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, et al. . Coffee and tea intake and the risk of myocardial infarction. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:162–7. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cornelis MC, El-Sohemy A, Kabagambe EK, et al. . Coffee, CYP1A2 genotype, and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA 2006;295:1135–41. 10.1001/jama.295.10.1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, et al. . Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ 2017;359:j5024 10.1136/bmj.j5024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ding M, Bhupathiraju SN, Satija A, et al. . Long-term coffee consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Circulation 2014;129:643–59. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ding M, Bhupathiraju SN, Chen M, et al. . Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2014;37:569–86. 10.2337/dc13-1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Onakpoya I, Spencer E, Heneghan C, et al. . The effect of green tea on blood pressure and lipid profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014;24:823–36. 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Park CS, Kim W, Woo JS, et al. . Green tea consumption improves endothelial function but not circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with chronic renal failure. Int J Cardiol 2010;145:261–2. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Geleijnse JM, Launer LJ, Van der Kuip DA, et al. . Inverse association of tea and flavonoid intakes with incident myocardial infarction: the Rotterdam Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;75:880–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chacko SM, Thambi PT, Kuttan R, et al. . Beneficial effects of green tea: a literature review. Chin Med 2010;5:13 10.1186/1749-8546-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Campbell NR, Ashley MJ, Carruthers SG, et al. . Lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension. 3. Recommendations on alcohol consumption. Canadian Hypertension Society, Canadian Coalition for High Blood Pressure Prevention and Control, Laboratory Centre for Disease Control at Health Canada, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. CMAJ 1999;160(9 Suppl):S13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bell S, Daskalopoulou M, Rapsomaniki E, et al. . Association between clinically recorded alcohol consumption and initial presentation of 12 cardiovascular diseases: population based cohort study using linked health records. BMJ 2017;356:j909 10.1136/bmj.j909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gémes K, Malmo V, Laugsand LE, et al. . Does moderate drinking increase the risk of atrial fibrillation? The Norwegian HUNT (Nord-Trøndelag Health) Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e007094 10.1161/JAHA.117.007094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Du S, Neiman A, Batis C, et al. . Understanding the patterns and trends of sodium intake, potassium intake, and sodium to potassium ratio and their effect on hypertension in China. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:334–43. 10.3945/ajcn.113.059121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lu J, Lu Y, Wang X, et al. . Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from 1.7 million adults in a population-based screening study (China PEACE Million Persons Project). Lancet 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Su M, Zhang Q, Bai X, et al. . Availability, cost, and prescription patterns of antihypertensive medications in primary health care in China: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2017;390:2559–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32476-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Spence JD. How to prevent your stroke. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, et al. . Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011;472:57–63. 10.1038/nature09922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]