Treatment with proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors reduce low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) by approximately 45–60%, whether used alone or in combination with a statin.1,2 Two large cardiovascular outcomes trials have now reported that lowering LDL-C with a PCSK9 inhibitor when added to treatment with a statin reduces the risk of major cardiovascular events.3,4 We sought to compare the efficacy of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins for reducing the risk of cardiovascular events by comparing the results of the FOURIER and SPIRE trials with the results of the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists (CTT) meta-analysis of statin trials.5,6

In the FOURIER trial, 27 564 patients with cardiovascular disease and LDL-C levels above 1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) on statin therapy were randomized to either 140 mg every 2 weeks (or 420 mg monthly) of evolocumab subcutaneously or matching placebo.3 At 48 weeks, treatment with evoloculmab reduced LDL-C by 59%, from a baseline level of 2.4 mmol/L (92 mg/dL) to 0.78 mmol/L (30 mg/dL). Using the CTT method of imputation for missing values, this translated into a 1.4 mmol/L (53.4 mg/dL) absolute difference in LDL-C between the two treatment groups. After a median follow-up of 26 months (2.2 years), treatment with evolocumab reduced the incidence of the composite primary cardiovascular endpoint of cardiovascular death (CVD), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, coronary revascularization, or hospitalization for unstable angina by 15%, from 11.3 to 9.8% (hazard ratio 0.85, 95% CI: 0.79–0.92, P < 0.001). The key secondary endpoint of CVD, MI, or stroke was reduced by 20%, from 7.4 to 5.9% (HR 0.80, 95% CI: 0.73–0.88, P < 0.001). When measured per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C, treatment with evolocumab reduced the risk of the primary outcome by 11.0% (HR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.84–0.94) per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C, and reduced the key secondary endpoint by 14.7% (HR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.80–0.91) per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C. The magnitude of this effect appears to be slightly less than the 22% reduction in risk (HR 0.78, 95% CI: 0.76–0.80) per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C during treatment with a statin as reported by CTT collaboration (P for difference = 1.6 × 10−5 for primary outcome; P = 0.015 for secondary outcome).5,6

Similarly, in two large-scale cardiovascular outcomes trials designated as SPIRE-1 and SPIRE-2, a total of 27 438 participants with either a history of cardiovascular disease, familial hypercholesterolaemia or who were at high risk for cardiovascular disease were randomized to either 150 mg every 2 weeks of bococizumab subcutaneously or matching placebo.4 The SPIRE trials were stopped early due to high rates of the development of neutralizing antidrug antibodies that resulted in an attenuation of the LDL-cholesterol lowering effect of bococizumab over time. The short duration of follow-up limits the usefulness of the findings in these prematurely terminated trials, but do shed some light on the effects of this class of drug. Because the median follow-up prior to discontinuation of the SPIRE-1 trial was only 7 months, we limit our analysis to the results of the SPIRE-2 trial which had a median follow-up of 12 months.

Among 10 621 patients with a baseline LDL-C greater than 2.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) enrolled in the SPIRE-2 trial, treatment with bococizumab reduced LDL-C by 54.6% at 14 weeks as compared to placebo which attenuated to a 40.6% reduction at 52 weeks, resulting in a reduction in LDL-C from a baseline level of 3.5 mmol/L (133.9 mg/dL) to 2.1 mmol/L (79.5 mg/dL) or a 1.5 mmol/L (57.3 mg/dL) absolute difference in LDL-C between the two treatment groups at 1 year. After a median follow-up of 1.0 year, treatment with bococizumab reduced the incidence of the primary composite outcome of CVD, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina requiring urgent coronary revascularization by 21%, from 4.2 to 3.2% (HR 0.79, 95% CI: 0.65–0.97, P = 0.02), and reduced the key secondary outcome of CVD, MI or stroke by 26%, from 3.6 to 2.7% (HR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.60–0.92, P = 0.007). When measured per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C, treatment with bococizumab reduced the risk of the primary outcome by 14.5% (HR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.75–0.98) per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C, and reduced the key secondary endpoint by 18.2% (HR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.71–0.94) per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C. As observed in the FOURIER trial, the magnitude of this effect appears to be slightly less than the 22% reduction in risk per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C during treatment with a statin (P for difference = 0.19 for primary outcome; P = 0.52 for secondary outcome).5,6

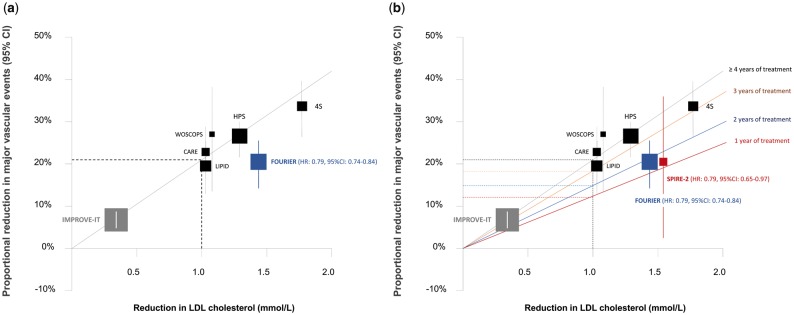

Indeed, when plotted on the CTT regression line, the results of the FOURIER trial does appear to fall slightly below the regression line describing the average expected benefit from treatment with a statin (Figure 1A).6 However, this may not be a fair comparison. It should be noted that the CTT regression line is based on the observed reduction in risk per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C over an average of 5 years of treatment with a statin. It is well recognized from the CTT meta-analysis that statins are associated with only a 10–12% reduction in cardiovascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C during the first year of treatment, followed by a 22–24% reduction in risk per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C during each subsequent year of treatment (Table 1).5–7 Therefore, due to the short duration of follow-up for both the FOURIER (2.2 years) and early-terminated SPIRE-2 (1 year) trials, the relevant analysis would be to compare the effect of PCSK9 inhibitors with the effect of statins on the risk of cardiovascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C for the same total duration of therapy or during each year of treatment.

Figure 1.

Boxes represent effect estimates and lines represent 95% confidence intervals. (A) Effect of evolocumab on the risk of major vascular events [cardiovascular death (CVD), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke or urgent revascularization] plotted on the overall Cholesterol Treatment Trialists (CTT) regression line representing the observed reduction in risk per mmol/L reduction in low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) over an average of 5 years of treatment with a statin. (B) Effect of evolocumab and bococizumab as compared to the effect of statins by duration of treatment (red line represents the fitted regression line for a 12% reduction in risk of major vascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C after 1 year of treatment; blue line represents 17% reduction in risk of major vascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C after 2 years of treatment; orange line represents 20% reduction in risk of major vascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C after 3 years of treatment; and grey line represents 22% reduction in risk of major vascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C after 4 or more years of treatment with a statin as estimated by the CTT collaborators). The regression line for each duration of therapy is derived by drawing a line through the estimated benefit of treatment with a statin per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C for any duration of therapy (given in Table 1, column 7) that is forced to pass through the origin. HPS, Heart Protection Study; 4S, Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study’ WOSCOPS, West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study; CARE, Cholesterol and Recurrent Events trial; LIPID, Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease trial.

Table 1.

Observed reduction in risk of major cardiovascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C by duration of treatment in the statin and PCSK9 trials

| Year of treatment | No. of events in CTT | HR (95% CI) during each year of treatment in CTT | HR (95%) during each year of treatment in SPIRE-2 | HR (95%) during each year of treatment in FOURIER | Cumulative duration of treatment (years) | HR (95%) for cumulative duration of statin treatment in CTT | HR (95%) by median duration of treatment in PCSK9 Trials | PCSK9 Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 7449 | 0.88 (0.84–0.93) | 0.86 (0.75–0.98) | 0.87 (0.79–0.97) | 1 | 0.88 (0.84–0.93) | 0.86 (0.75–0.98) | SPIRE-2 trial |

| 1–2 | 4757 | 0.77 (0.73–0.82) | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 2 | 0.83 (0.80–0.86) | 0.83 (0.77–0.90) | FOURIER trial | |

| 2–3 | 4081 | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) | 3 | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) | Anticipated ODESSEY trial Results | ||

| 3–4 | 3462 | 0.72 (0.68–0.77) | 4 | 0.78 (0.76–0.81) | ||||

| 4–5 | 2710 | 0.77 (0.72–0.83) | 5 | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) | ||||

| >5 | 1864 | 0.76 (0.69–0.85) | 6 | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) | ||||

| Overall | 24 323 | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) | Mean 5.1 | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) |

The overall estimate of the effect of statin therapy per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C over a mean of 5.1 years of follow-up is derived by combining the effect of statin treatment per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C during each year of treatment (column 3) for all treatment periods in a fixed effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis as described by the CTT collaboration. The HR (95%) for the effect of statin therapy per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C for any period of total duration of treatment (column 7) can therefore be derived by combining the effect of statin treatment per mmol/L reduction for each year of treatment (column 3) up to and including the corresponding total length of treatment duration of interest in a fixed effects inverse variance-weighted meta-analysis. For example, the effect of two years of treatment with a statin is estimated by a fixed effect inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis of the HR per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C during treatment year 0-1 and year 1-2 in column 3. Similarly, the effect of three years of treatment with a statin is estimated by a fixed effect inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis of the HR per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C during treatment year 0-1, year 1-2, and year 2-3 in column 3. HR is hazard ratio. CTT is the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists meta-analysis of statin trials. Median follow-up in SPIRE-2 was 12 months. Median follow-up in FOURIER was 2.2 years. Median follow-up in ODESSEY is anticipated to be 33 months (2.75 years). Data from SPIRE-1 are excluded because the median follow-up was only 7 months. Italics indicate the anticipated results from the ongoing ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial.

We can compare the effect of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins during each year of therapy and for the same total duration of therapy by first noting that the CTT Collaborators have indeed already reported the effect of treatment with a statin on the risk of cardiovascular events separately during each year of therapy (Table 1).5,6 The well-known CTT regression line describing the effect of statins on the risk of cardiovascular events over an average of 5 years of treatment is derived from a meta-analysis of the separate estimates of effect during each year of treatment. Recognizing this fact, we can calculate the expected reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C for any duration of treatment that we choose as described in the Table 1, and re-draw the CTT regression line to estimate the effect of statins on the risk of cardiovascular events for various durations of total treatment as shown in Figure 1B.

When analysed in this way, the PCSK9 inhibitors and statins appear to have remarkably similar effects on the risk of cardiovascular events for the same duration of therapy (Table 1). In the SPIRE-2 trial, 1 year of treatment with bococizumab reduced the risk of major vascular events (CVD, MI, stroke, or urgent revascularization) by 14.5% per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C (HR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.75–0.98), which is very similar to the 12% reduction in major vascular events after 1 year of treatment with a statin in the CTT meta-analysis. Similarly, in the FOURIER trial, 2.2 years of treatment with evolocumab reduced the risk of major vascular events by 16% per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C (HR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.80–0.88), which is nearly identical to the 17% reduction in major vascular events after 2 years of treatment with a statin in the CTT meta-analysis. Indeed, when the results of the FOURIER and SPIRE-2 trials are plotted on the separate CTT regression lines recalculated for each duration of therapy, they agree very closely with the results observed in the statin trials (Figure 1B).

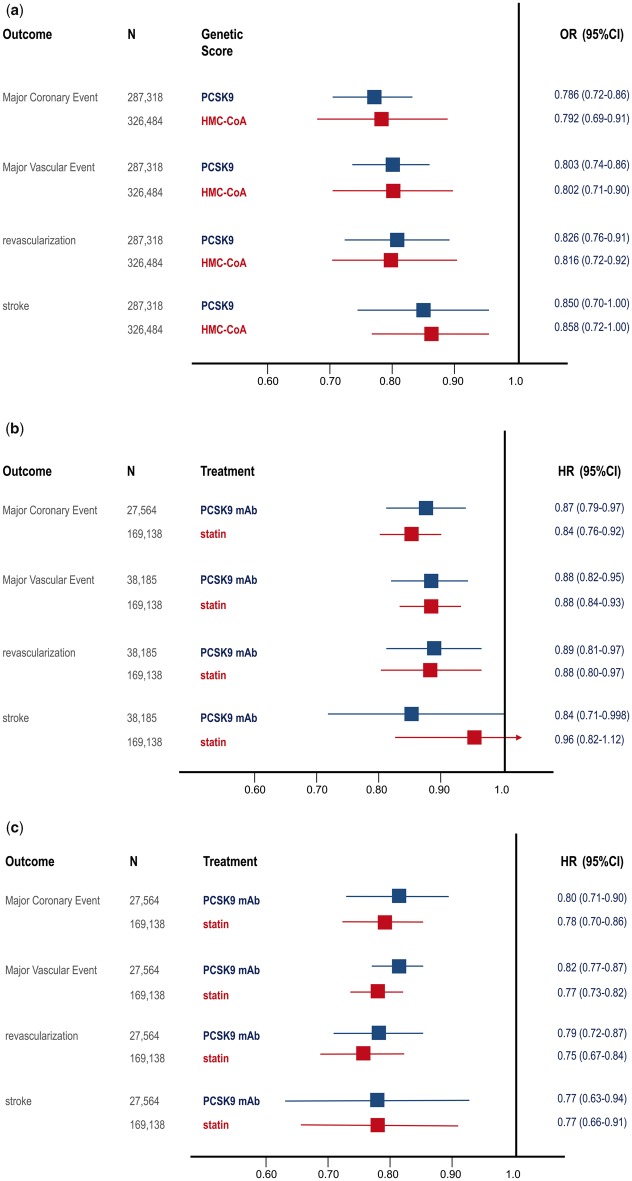

Similarly, the PCSK9 inhibitors and statins also appear to have remarkably similar effects on the risk of cardiovascular events during each year of treatment (Figure 2). In a combined analysis of the FOURIER and SPIRE-2 trials, treatment with either evolocumab or bococizumab during the first year of treatment reduced the risk of multiple different cardiovascular outcomes by 11–16%, which is nearly identical to the 4–16% reduction in risk per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C observed during the first year of treatment in the statin trials. Similarly, in the FOURIER trial, treatment with evolocumab during the second year of the trial reduced the risk of multiple cardiovascular outcomes by 18–23% per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C, which is very similar to the 22–25% reduction in risk for these same outcomes observed during the second year of treatment in the statin trials (Figure 2). Together, these analyses demonstrate that treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors and statins have nearly identical effects on the risk of cardiovascular events per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C when compared by total duration of therapy and during each year of treatment.

Figure 2.

Boxes represent effect estimates and lines represent 95% confidence intervals. (A) Effect of variants that mimic proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors as compared to variants that mimic statins on the risk of various cardiovascular outcomes per 0.25 mmol/L reduction in low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). (B) Effect of PCSK9 inhibitors per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C in a meta-analysis of the FOURIER and SPIRE-2 trials during the first year of treatment as compared with the effect of statins during the first year of treatment per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C as reported by the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists (CTT) Collaboration. (C) Effect of PCSK9 inhibitors in the FOURIER trial per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C during the second year of treatment as compared to the effect of statins during the second year of treatment per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C as reported by the CTT.

This conclusion is strongly supported by the results of a recent Mendelian randomization study that demonstrated that genetic variants that mimic the effect of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins have nearly identical effects on the risk of cardiovascular disease per unit change in LDL-C. These data suggested that inhibition of PCSK9 and HMG-CoA reductase (the target of statins) have biologically equivalent effects on the risk of cardiovascular events per unit change in LDL-C and therefore explicitly predicted that PCSK9 inhibitors and statins should therefore have therapeutically equivalent effects on the risk of cardiovascular events per unit change in LDL-C.8 As described above, this is exactly what the FOURIER and SPIRE-2 trials showed (Figure 2). The remarkable concordance between the naturally randomized genetic evidence, the CTT meta-analysis of statin trials, and the results of the FOURIER and SPIRE-2 trials when considered both by total duration of therapy and during each year of treatment clearly demonstrates that PCSK9 inhibitors and statins have equivalent effects on the risk of cardiovascular events per unit change in LDL-C. Furthermore, this concordance strongly suggests that the effect of both PCSK9 inhibitors and statins on the risk of cardiovascular events is due entirely to the absolute achieved reduction in LDL-C rather than to potential pleiotropic effects.

The fact that the clinical benefit of both PCSK9 inhibitors and statins depends on the absolute magnitude of the achieved LDL-C reduction and the total duration of treatment has important implications for the on-going ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial.9,10 This trial randomized 18 600 patients to biweekly injections of alirocumab (initially 75 mg adjusted to 150 mg in a blinded fashion to achieve an LDL-C value of between 15 and 50 mg/dL with dose adjustment for patients with LDL-C below 15 mg/dL) or matching placebo beginning 1 to 12 months after an index hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina.10 Assuming that the tailored-dose approach will lead to a 50% reduction in LDL-C, treatment with alirocumab should reduce LDL-C by approximately 1.1 mmol/L (43.2 mg/dL) from a baseline LDL-C level of 2.2 mmol/L (86.4 mg/dL). Importantly, in the CTT meta-analysis, treatment with a statin reduced major cardiovascular events by 17% after 2 years of treatment and by 20% after 3 years of treatment (Table 1). Therefore, based on an expected median follow-up of 33 months (2.75 years), reducing LDL-C by 1.1 mmol/L with alirocumab should reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events by approximately 18–22% in the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial.

Finally, it is important to note that treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor was very safe even with very low absolute achieved LDL-C levels in the FOURIER and SPIRE trials. There was no evidence of any increased risk of neurocognitive effects or cataracts in either trial.3,4 By contrast, there was a numerically greater number of patients who experienced new onset diabetes in the FOURIER trial (HR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.95–1.17, P = 0.34) and among patients with the lowest achieved LDL-C (at least one LDL-C value < 25 mg/dL) in the SPIRE trials (HR: 1.21, 95% CI: 0.99–1.49, P = 0.07).3,4 In addition, treatment with bococizumab was associated with a 1.74 mg/dL increase in fasting serum glucose (95% CI: 0.56–2.92, P = 0.004) in the SPIRE trials.4 Taken together, these findings are consistent with a meta-analysis of statin trials demonstrating that treatment with statin is associated with a small increase in the risk of diabetes, and with Mendelian randomization studies demonstrating that variants that mimic PCSK9 inhibitors and statins are associated with a similar increased risk of diabetes per unit change in LDL-C.9,11 It is important to note, however, that the naturally randomized genetic evidence suggests that only persons with impaired fasting glucose are at risk for PCSK9 or statin induced new onset diabetes.9 Additional analysis of the FOURIER, SPIRE, and ODESSEY trials stratified by fasting glucose level should provide more insight into whether there is a clinically relevant effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on the risk of new onset diabetes. Importantly, however, it should be emphasized that both the naturally randomized genetic evidence and the statin trials clearly suggest that the beneficial effect of lowering LDL-C by inhibiting either PCSK9 or HMG-CoA reductase far exceeds any potential risk of new onset diabetes.9,11

In conclusion, the results of the FOURIER and SPIRE trials demonstrate that lowering LDL-C with a PCSK9 inhibitor reduces the risk of major cardiovascular events by the same amount as statins per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C. The magnitude of the observed risk reduction in the FOURIER and SPIRE trials was exactly what would have been expected based on the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists meta-analysis of statin trials when the effect of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins are compared either by total duration of treatment or by the observed effect during each year of treatment. The remarkable concordance between the naturally randomized genetic evidence, the results of the CTT meta-analysis of statin trials and the results of PCSK9 inhibitor cardiovascular outcomes trials demonstrates that PCSK9 inhibitors and statins reduce the risk of cardiovascular events proportional to the absolute achieved reduction in LDL-C and the total duration of therapy.

Funding

H2020 Grant REPROGRAM PHC-03-2015/667837-2 and CARIPLO Foundation (2015-0524 and 2015-0564) to A.L.C.

Conflict of interest: A.L.C. has received research grants to his institution from Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Merck, Regeneron/Sanofi, and Sigma Tau, and honoraria for advisory boards, consultancy or speaker bureau from Abbot, Aegerion, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, Merck/MSD,Mylan, Pfizer, Rottapharm and Sanofi-Regeneron. B.F. has received research grants from Merck & Co, Amgen, Esperion Therapeutics and honoraria from Merck & Co Amgen, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, American College of Cardiology. C.C. has received research grants from Amgen Arisaph Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen,Daichi-Sankyo, BMS, Amgen Takeda, and honoraria from Sanofi / Regeneron, Amgen, Pfizer, Arisaph, Boehringer-Ingelheim GlaxoSmithKline Takeda Lipimedix BMS Kowa Alnylam AstraZeneca. K.R. has received grants from Sanofi, Regeneron, Pfizer, Amgen, MSD and honoraria from Sanofi, Amgen, Regeneron, Lilly, Medicines Company, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Kowa, Algorithm, IONIS, Esperion, Novo Nordisk, Takeda, Boehringer Ingelheim, Resverlogix, Abbvie. U.L has received honoraria from Amgen, Sanofi, Medicines Company, Berlin Chemie, MSD. T.L. has received research grants from Amgen, Astrazeneca , honoraria from Amgen, Astrazeneca and other from Amgen, Atrazeneca, Sanofi, Pfizer.

Footnotes

This paper was guest edited by Prof. Anthnony DeMaria.

References

- 1. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, Raal FJ, Blom DJ, Robinson J, Ballantyne CM, Somaratne R, Legg J, Wasserman SM, Scott R, Koren MJ, Stein EA.. Open-Label Study of Long-term Evaluation Against LDL Cholesterol (OSLER) Investigators. Efficacy and safety of Evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1500–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, Bergeron J, Luc G, Averna M, Stroes ES, Langslet G, Raal FJ, El Shahawy M, Koren MJ, Lepor NE, Lorenzato C, Pordy R, Chaudhari U, Kastelein JJ, ODYSSEY LONG TERM Investigators. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1489–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Wang H, Liu T, Wasserman SM, Sever PS, Pedersen TR, FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1713–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ridker PM, Revkin J, Amarenco P, Brunell R, Curto M, Civeira F, Flather M, Glynn R, Gregoire J, Jukema JW, Karpov Y, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Lorenzatti Manga P, Masiukiewicz U, Miller M, Mosterd A, Murin J, Nicolau JC, Nissen S, Ponikowski P, Santos RD, Schwartz PF, Soran H, White H, Wright RS, Vrablik M, Yunis C, Shear CL, Tardif JC, SPIRE Cardiovascular Outcome Investigators. Cardiovascular efficacy and safety of bococizumab in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1527–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R, Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, Bhala N, Peto R, Barnes EH, Keech A, Simes J, Collins R.. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170 000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376:1670–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, Armitage J, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Blumenthal R, Danesh J, Smith GD5, DeMets D, Evans S, Law M, MacMahon S, Martin S, Neal B, Poulter N, Preiss D, Ridker P, Roberts I, Rodgers A, Sandercock P, Schulz K, Sever P, Simes J, Smeeth L, Wald N, Yusuf S, Peto R.. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet 2016;388:2532–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ference BA, Robinson JG, Brook RD, Catapano AL, Chapman MJ, Neff DR, Voros S, Giugliano RP, Davey Smith G, Fazio S, Sabatine MS.. Variation in PCSK9 and HMGCR and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2144–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, Hegele RA, Krauss RM, Raal FJ, Schunkert H, Watts GF, Borén J, Fazio S, Horton JD, Masana L, Nicholls SJ, Nordestgaard BG, van de Sluis B, Taskinen MR, Tokgozoglu L, Landmesser U, Laufs U, Wiklund O, Stock JK, Chapman MJ, Catapano AL.. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic and clinical studies. A Consensus Statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2459–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwartz GG, Bessac L, Berdan LG, Bhatt DL, Bittner V, Diaz R, Goodman SG, Hanotin C, Harrington RA, Jukema JW, Mahaffey KW, Moryusef A, Pordy R, Roe MT, Rorick T, Sasiela WJ, Shirodaria C, Szarek M, Tamby JF, Tricoci P, White H, Zeiher A, Steg PG.. Effect of alirocumab, a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, on long term cardiovascular outcomes following acute coronary syndromes: rationale and design of the ODYSSEY outcomes trial. Am Heart J 2014;168:682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swerdlow DI, Preiss D, Kuchenbaecker KB, Holmes MV, Engmann JE, Shah T, Sofat R, Stender S, Johnson PC, Scott RA, Leusink M, Verweij N, Sharp SJ, Guo Y, Giambartolomei C, Chung C, Peasey A, Amuzu A, Li K, Palmen J, Howard P, Cooper JA, Drenos F, Li YR, Lowe G, Gallacher J, Stewart MC, Tzoulaki I, Buxbaum SG, van der A DL, Forouhi NG, Onland-Moret NC, van der Schouw YT, Schnabel RB, Hubacek JA, Kubinova R, Baceviciene M, Tamosiunas A, Pajak A, Topor-Madry R, Stepaniak U, Malyutina S, Baldassarre D, Sennblad B, Tremoli E, de Faire U, Veglia F, Ford I, Jukema JW, Westendorp RG, de Borst GJ, de Jong PA, Algra A, Spiering W, Maitland-van der Zee AH, Klungel OH, de Boer A, Doevendans PA, Eaton CB, Robinson JG, Duggan D DIAGRAM Consortium; MAGIC Consortium; InterAct Consortium Kjekshus J, Downs JR, Gotto AM, Keech AC, Marchioli R, Tognoni G, Sever PS, Poulter NR, Waters DD, Pedersen TR, Amarenco P, Nakamura H, McMurray JJ, Lewsey JD, Chasman DI, Ridker PM, Maggioni AP, Tavazzi L, Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Manson JE, Price JF, Whincup PH, Morris RW, Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Ben-Shlomo Y, Schreiner PJ, Fornage M, Siscovick DS, Cushman M, Kumari M, Wareham NJ, Verschuren WM, Redline S, Patel SR, Whittaker JC, Hamsten A, Delaney JA, Dale C, Gaunt TR, Wong A, Kuh D, Hardy R, Kathiresan S, Castillo BA, van der Harst P, Brunner EJ, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Marmot MG, Krauss RM, Tsai M, Coresh J, Hoogeveen RC, Psaty BM, Lange LA, Hakonarson H, Dudbridge F, Humphries SE, Talmud PJ, Kivimäki M, Timpson NJ, Langenberg C, Asselbergs FW, Voevoda M, Bobak M, Pikhart H, Wilson JG, Reiner AP, Keating BJ, Hingorani AD, Sattar N.. HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibition, type 2 diabetes, and bodyweight: evidence from genetic analysis and randomised trials. Lancet 2015;385:351–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]