Abstract

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT) is a rare neoplasm, occurring most often in children and young adults. IMTs have intermediate biological behaviour with the chance of local invasion, recurrence and even distant metastasis. Wide range of clinical presentations makes the precise diagnosis of IMT more challenging. The best method for definitive diagnosis is tissue biopsy and newer imaging modalities including fleurodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT are useful tools in detection of disease recurrence or distant metastasis. Complete surgical resection is the best-known treatment for this tumour. Here we are presenting an IMT case in a 12-year-old girl in which her recurrent pulmonary IMT was diagnosed based on FDG PET/CT findings and referred for further salvage treatment. Overall imaging modalities are not specific, but PET/CT scan can be useful tool for evaluation of IMT regarding initial staging and restaging to assess treatment response and recurrence.

Keywords: oncology, radiology

Background

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT) is a rare neoplasm which is believed to include less than 1% of soft-tissue sarcomas.1 The tumour that is also called inflammatory pseudotumour (IPT) or plasma cell granuloma occurs most often in children and young adults and predominantly has a benign nature but in some occasions, it can have more aggressive and malignant behaviour.2

Aetiology of this tumour is not well understood; however, trauma, surgery, some viral infections and autoimmune disorders can be considered as an underlying aetiology.3 4

Lung is the most common site for IMT. However, the variety of extrapulmonary sites including skull base, head and neck, liver, peritoneum, retroperitoneum, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, genitourinary tract, extremities, breast and even heart can be affected.5–11 Depending on location, this tumour may present with different symptoms such as fever, flu-like symptoms, headache, nerve palsy, facial pain, exertional dyspnoea and abdominal pain7 12–14 and this wide spectrum of clinical presentations makes the precise diagnosis even more challenging for this entity.5

The best method for definitive diagnosis is tissue biopsy. Typical pathological finding in the biopsy specimen is presence of mesenchymal spindle cells in the context of inflammatory cells.15

Complete surgical resection is the best-known treatment for this tumour.15 Imaging modalities can be considered as diagnostic tool for detecting IMTs. Considering the hypermetabolic nature of this tumour, fleurodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT can be used for detection of recurrence and distant metastasis.16 17 FDG PET/CT findings of IMTs have been discussed in limited number of cases based on our literature review.16 In this paper, we will present an interesting case of recurrent pulmonary IMT in a 12-year-old girl and discuss her FDG PET/CT findings followed by a quick glance at the literature.

Case presentation

A 12-year-old girl was referred to our department (PET/CT) for evaluation of response to treatment.

She was first diagnosed with IMT in September 2015. The patient was diagnosed after 3 weeks of fatigue, nervousness, malaise, decreased appetite and weight loss (30 kg to 24 kg) which was followed by 1 week of uncontrolled chills and fever.

Investigations

Initial investigations

She was admitted to children hospital for further workup. Initial laboratory findings demonstrated anaemia, leucocytosis and evidence of a 92×82×61 mm pulmonary mass in the posteromedial segment of the right lower lobe.

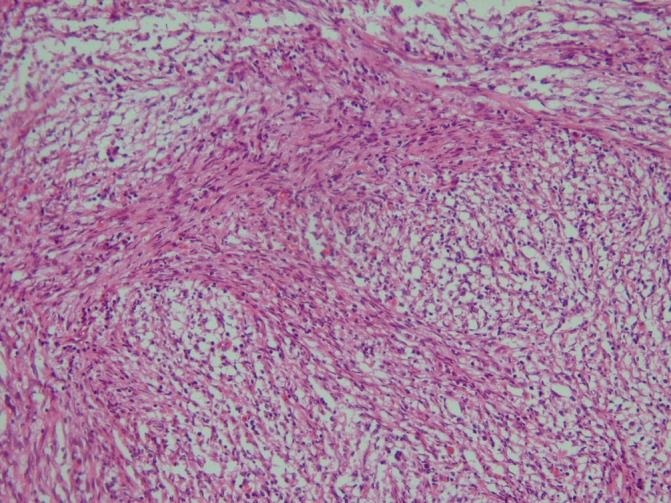

The mass was biopsied under CT scan guidance and the pathology report stated pulmonary tissue involved by uniform neoplastic cells with fascicular pattern and scattered mononuclear leucocytes and peripheral lymphoplasmacytosis (figure 1). Immunohistochemical studies of the biopsy specimen showed a positive reaction for vimentin and smooth muscle and negative reaction for S-100, CD34 and ALK-1 and about 5% of tumour cells demonstrated positive reaction for Ki-67. Finally, the diagnosis of the IMT was established.

Figure 1.

Myofibroblastic and fibroblastic spindle cells with inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils and histiocytes.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis for an IMT presenting in the lung is IgG4-related IPT which is an inflammatory reactive lesion in which the expression of ALK-1 in spindle cells helps to distinguish IMTs from IgG4-related IPTs.18 Additional differential diagnosis includes pulmonary desmoid tumours and malignant lung masses such as primary bronchogenic carcinoma.

Treatment

After initial workup, she was referred for further evaluation and resection of the tumour. The tumour was successfully resected followed by referral to an oncologist for systemic treatment. Chemotherapy was initiated with chemotherapy courses at 25-day intervals.

Outcome and follow-up

Recurrence

Six months after completion of chemotherapy and during routine surveillance, recurrent mass in right pulmonary lower lobe was detected on CT-scan. Subsequently, she underwent the second surgery in March 2016 followed by another course of chemotherapy. Almost 4 months later, another mass in left lower lobe was found on CT-scan and the third subsequent surgery was performed in July 2016.

Secondary investigation

During routine follow-up, after detection of a single 9.5 mm nodule in superior segment of left lower lobe and three additional small nodules (2.5–3 mm) in left upper lobe and also a suspicious bone lesion in T11 found on the whole body bone scan, the patient was referred to PET/CT department for recurrence evaluation.

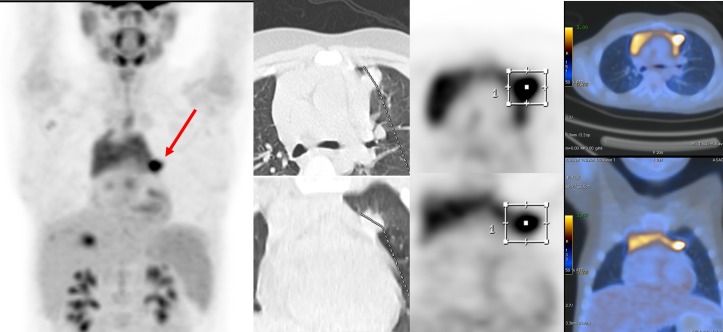

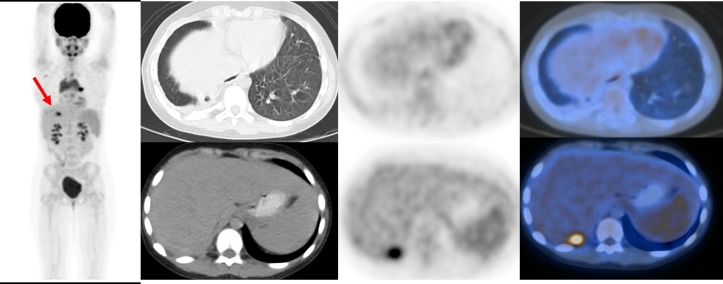

Sixty minutes after injection of 4.5 MBq/kg of 18F-FDG, the PET/CT imaging was acquired using a Discovery 690 VCT (General Electric (GE) Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) that is equipped with 64-slice CT scan (Light Speed VCT) from head to mid-thighs. PET/CT scan revealed a hypermetabolic left lung nodule measuring 15×17 mm (SUVmax=5.8) (figure 2), a hypermetabolic right pleural focus adjacent to right 11th rib (SUVmax=4.1) and right pleural effusion and thickening with mild metabolic activity (figure 3), sclerotic lesion in 11th vertebra with sclerotic border and no abnormal metabolic activity and also diffuse increased metabolic activity of spleen compared with the background liver parenchyma.

Figure 2.

Hypermetabolic left lung nodule measuring 15×17 mm (SUVmax=5.8).

Figure 3.

Hypermetabolic right pleural focus adjacent to right 11th rib (SUVmax=4.1) and right pleural effusion and thickening with mild metabolic activity.

With respect to these findings, the patient was referred for the fourth surgery and subsequent chemotherapy (salvage treatment).

Discussion

Since its first introduction in 1939 by Brunn in the lung, our knowledge about IMT has changed dramatically.19

Numerous reports stated that it can be found in different locations from head and neck to thorax and abdomen and even extremities. Therefore, the variety of signs and symptoms can be presented by this tumour. Pang et al11 reported a case of the right ventricular IMT in an 11-month-old infant presented with febrile illness. Oh et al20 described an IMT in the appendix of an 85-year-old man with the history of gastric cancer. Another interesting site for this tumour reported by Lyon et al21 in carina of a 7-year-old girl who presented with cough, wheezing and pneumonia with evidence of near-total obstruction of the trachea.

At the initial diagnosis, majority of these tumours are large, ranging from 3 to 10 cm (average 7 cm)).22 This rare tumour which is frequently found in children and young adults has the female gender preference.

It is predominantly benign, but has the potential to infiltrate to adjacent organs which mimic malignant tumours23 24 and sometimes it can have malignant behaviour or transform into a malignant tumour.25 It frequently recurs but metastasis is a rare finding, so it is believed that it has an intermediate biological behaviour which is also confirmed in the histological classification of soft tissue tumours by WHO.12 26

Wang et al27 reported a case of recurrent retroperitoneal IMT in a 74-year-old woman, who was presented with 10 cm mass found incidentally during cholecystectomy. The tumour recurred 30 months after first surgery and was successfully retreated. Two cases of recurrent IMTs were found by Li et al28 in the right upper extremity of a Chinese woman and the right thigh of a Chinese man. Both tumours recurred less than a year after initial surgery. Corsi et al29 also reported a case of recurrent IMT in anterior wall of the glottis. Pascual-Gallego et al30 presented a rare case of meningeal IMT which was found in a woman with a history of retroocular pain and recurrent headache.

Gorolay et al31 found a 9.7×6×8.6 cm tumour in mediastinum of a 49-year-old man with oesophageal and bronchial invasion who was evaluated for progressive dyspnoea and dysphagia. Serial imaging with CT scan revealed a large subcarinal mass with dilation of upper oesophagus and main stem bronchus and lobar obstruction. PET/CT was performed for staging and revealed an area of intense metabolic activity in mediastinum with no evidence of distant metastasis. Inoue at al32 described a case of the IMT with multiple organ involvements in a 16-year-old girl with the history of tonic-clonic seizure. The patient was worked up and at least three tumours were found in the right cerebral hemisphere. With a high level of suspicious for malignancy, chest and abdominal CT scans were performed revealing multiple lung nodules, a breast mass and also at least four pancreatic masses.

The histopathological feature of this tumour includes myofibroblastic mesenchymal spindle cells accompanied by inflammatory cells including plasma cells, lymphocytes and eosinophils in a collagenous or myxoid stroma.3

Overall on CT scan, IMTs usually appear as solitary, well-circumscribed peripheral lung masses, with predominance for the lower lobes. Calcification of the masses is unusual (about 15%). It is not frequent, but they can also be multiple. On CT with intravenous contrast, they present a variable heterogeneous or homogeneous degree of enhancement pattern. It has been described an aggressive behaviour with invasion of the adjacent structures. On MRI, they present similar radiological findings as in other locations. Because of their similar radiological appearance to malignant lung masses, biopsy is necessary.33

PET/CT is a well-known non-invasive hybrid imaging modality (both anatomical and functional) that has gained lots of attention during past decades. 18F-FDG is the main PET radiotracer which is used in oncology. Many malignant and benign neoplasms and also inflammatory processes demonstrate uptake of 18F-FDG relative to the rate of tissue metabolism.17 Providing physiological information makes the PET/CT scanning a unique imaging tool in the evaluation of oncology patients in terms of response assessment, recurrence evaluation, tumour staging and radiotherapy planning.17 34 There are several reports in the literature that describes 18F-FDG avid IMTs. Ilic et al17 described a pulmonary IMT in a 14-year-old girl with the history of Hodgkin’s lymphoma which showed very intense uptake on 18F-FDG PET/CT. Kuo et al35 reported a case of the metastatic IMT with the origin in left hemithorax. The 18F-FDG PET/CT revealed areas of higher activity in jejunum and body of the pancreas. Yoon et al36 described a large IMT in the right paratracheal space of a 25-year-old man with was incidentally found in X-ray which showed heterogeneous 18F-FDG uptake. The PET/CT scan findings in our case were consistent with the recurrent/residual disease after multiple treatments and more importantly, PET/CT was able to show metabolic activity in the right pleural effusion and hypermetabolic focus in the right pleura which were almost impossible to be detected by means of other imaging modalities.

Conclusion

IMTs are rare tumours with different origins and different signs and symptoms. Imaging modalities are not specific, but PET/CT scan can be a useful imaging tool for evaluation of IMT regarding initial staging and restaging to assess treatment response and recurrence.

Learning points.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours (IMTs) can occur almost anywhere in the body and mimic other diseases. Hence, clinicians should consider this condition in differential diagnosis.

Although imaging findings of IMTs are not specific, 18F-fleurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT can be considered as a diagnostic guide.

IMTs have intermediate biological behaviour with the chance of local invasion, recurrence and even distant metastasis.

Complete surgical resection of the tumour is the best-known treatment.

Footnotes

Contributors: AbD: Case report concept and final revision and editing. FK: Manuscript drafting and gathering information. PM: Revising the manuscript and grammatical check. AtD: Pathology review and final revision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ong HS, Ji T, Zhang CP, et al. Head and neck inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT): evaluation of clinicopathologic and prognostic features. Oral Oncol 2012;48:141–8. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karnak I, Senocak ME, Ciftci AO, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in children: diagnosis and treatment. J Pediatr Surg 2001;36:908–12. 10.1053/jpsu.2001.23970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buccoliero AM, Ghionzoli M, Castiglione F, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular features of a pediatric case. Pathol Res Pract 2014;210:1152–5. 10.1016/j.prp.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, et al. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:859–72. 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koirala R, Shakya VC, Agrawal CS, et al. Retroperitoneal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Am J Surg 2010;199:e17–e19. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang L, Lai EC, Cong WM, W-m C, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver: a cohort study. World J Surg 2010;34:309–13. 10.1007/s00268-009-0330-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garg V, Temin N, Hildenbrand P, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the skull base. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;142:129–31. 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu HK, Lin YC, Yeh ML, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the pancreas in children: A case report and literature review. Medicine 2017;96:e5870 10.1097/MD.0000000000005870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marraoui W, Jean B, Muheish M, et al. Imaging of inflammatory myofibroblastic cervical tumours: a case report. Diagn Interv Imaging 2012;93:617–20. 10.1016/j.diii.2012.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jumanne S, Shoo A, Mumburi L, et al. Gastric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor presenting as fever of unknown origin in a 9-year-old girl. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;29:68–72. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang R, Merritt NH, Shkrum MJ, et al. Febrile illness in an infant with an intracardiac inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20143544 10.1542/peds.2014-3544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi H, Wei L, Sun L, et al. Primary gastric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 5 cases. Pathol Res Pract 2010;206:287–91. 10.1016/j.prp.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao DP, Pujary K, Mathew M, et al. Maxillary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2017;10:1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang Y, Sun JP, Lu M, et al. A rare case with pulmonary and cardiac inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Circulation 2015;131:e511–e513. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.014306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalton BG, Thomas PG, Sharp NE, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in children. J Pediatr Surg 2016;51:541–4. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong A, Wang Y, Dong H, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: FDG PET/CT findings with pathologic correlation. Clin Nucl Med 2014;39:113–21. 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182952caa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilic V, Dunet V, Beck-Popovic M, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour after Hodgkin’s lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:bcr2013202491 bcr2013202491 10.1136/bcr-2013-202491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu L, Li J, Liu C, Longfei Z, Jian L, Chengwu L, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor versus IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumor: differential diagnosis based on a case series. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:598–609. 10.21037/jtd.2017.02.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thistlethwaite PA, Renner J, Duhamel D, et al. Surgical management of endobronchial inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:367–72. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh E, Ro JY, Gardner JM, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the appendix arising after treatment of gastric cancer: a case report and review of the literature. APMIS 2014;122:657–9. 10.1111/apm.12205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyon JG, Kilpatrick LA, Rosenberg TL, et al. Carinal resection and reconstruction following inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor resection: A case report. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2016;5:1–3. 10.1016/j.epsc.2015.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazure T, Ferlicot S, Gauthier F, et al. Gastric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in children: an unpredictable course. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2002;34:319–22. 10.1097/00005176-200203000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim KA, Park CM, Lee JH, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the stomach with peritoneal dissemination in a young adult: imaging findings. Abdom Imaging 2004;29:9–11. 10.1007/s00261-003-0085-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oto A, Akata D, Besim A. Peritoneal inflammatory myofibroblastic pseudotumor metastatic to the liver: CT findings. Eur Radiol 2000;10:1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zavaglia C, Barberis M, Gelosa F, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver with malignant transformation. Report of two cases. Ital J Gastroenterol 1996;28:152–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dehner LP. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: the continued definition of one type of so-called inflammatory pseudotumor. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:1652–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Zhao X, Chin J, et al. Recurrent retroperitoneal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: A case report. Oncol Lett 2016;12:1535–8. 10.3892/ol.2016.4767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li CF, Liu CX, Li BC, Cui X-B, et al. Recurrent inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors harboring PIK3CA and KIT mutations. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:3673. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corsi A, Ciofalo A, Leonardi M, et al. Recurrent inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the glottis mimicking malignancy. Am J Otolaryngol 1997;18:121–6. 10.1016/S0196-0709(97)90100-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pascual-Gallego M, Yus-Fuertes M, Jorquera M, et al. Recurrent meningeal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a case report and literature review. Neurol India 2013;61:644 10.4103/0028-3886.125273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorolay V, Jones B. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of mediastinum with esophageal and bronchial invasion: a case report and literature review. Clin Imaging 2017;43:32–5. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue M, Ohta T, Shioya H, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the breast with simultaneous intracranial, lung, and pancreas involvement: ultrasonographic findings and a review of the literature. Journal of Medical Ultrasonics 2017:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cantera JE, Alfaro MP, Rafart DC, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging 2015;6:85–96. 10.1007/s13244-014-0370-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakhshayesh Karam M, Doroudinia A, Safavi Nainee A, et al. Role of fdg pet/ct scan in head and neck cancer patients. Arch Iran Med 2017;20:452–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo PH, Spooner S, Deol P, et al. Metastatic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor imaged by PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med 2006;31:106–8. 10.1097/01.rlu.0000197052.28851.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon SH, Lee S, Jo KS, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor in the mediastinum: imaging with (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT. Korean J Radiol 2013;14:673–6. 10.3348/kjr.2013.14.4.673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]