Abstract

Ajuga lobata D. Don is a medicinal plant rich in 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E), alkaloids, and other active substances. In this study, the cell suspension was incubated for 7 days, followed by the analysis on the effects of abscisic acid (ABA) on the regulation of 20E synthesis. Then A. lobata suspension cells treated with 0.15 mg/l ABA were used as material, with the Illumina technology applied for transcriptome sequencing. Digital analysis on the gene expression profile was carried out on ABA treated and control samples, respectively. Finally, transcriptomics was applied to assess the molecular response of A. lobata induced by ABA through applying transcriptomics by evaluating differentially expressed genes. The results suggested that ABA promoted 20E accumulation, while longer processing time caused cell browning. A total of 154 genes were significantly regulated after ABA treatment, with 99 up-regulated and 55 down-regulated, respectively. In addition to 20E-related pathways, the genes belonged to the ko00900 (terpenoid backbone biosynthesis) pathway (six differentially expressed genes [DEGs]), ko00100 (steroid biosynthesis) pathway (four DEGs), and ko00140 (steroid hormone biosynthesis) pathway (six DEGs). Providing a better understanding of the 20E biosynthetic pathway and its regulation, in particular in plants, this study is necessary.

Keywords: Ajuga lobata D. Don, Cell suspension, 20-Hydroxyecdysone, Transcriptomics, Gene expression

Introduction

Ajuga lobata D. Don belongs to Lamiaceae in the order of Lamiales; Originating from the United States of America, it is mainly distributed in the southern part of China (Coll et al. 2007; Coll and Tandron 2008). A. lobata is a medicinal plant rich in sterones, alkaloids and other active substances; it is used for the treatment of inflammation, blood pressure, detoxification heat (Guo et al. 2005; Xiong et al. 2012; Cai et al. 2014). Ajuga contains 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E), which is the molting hormone of most arthropods, distributed in the plant kingdom and can be used as insecticide and insect growth regulator (Fekete et al. 2004; Rharrabe et al. 2009). It was demonstrated that 20E could cause deformity of larva or pupa in insects, resulting in death; in addition, it could impose antifeedant effects on insects as well (Ufimtsev et al. 2003; Marion-Poll et al. 2005; Selvaraj et al. 2007).

The commercial anabolic preparations and 20E supply for agricultural and therapeutic uses are mainly extracted from collected wild plants making it necessary to develop more reliable and sustainable means for 20E production and other bioactive ecdysteroids. Plant tissue and cell cultures can be alternatively used for the production of ecdysteroids (Lev et al. 1990; Wang et al. 2013).

The structure of 20-hydroxyecdysone is characterized by a cis-A/B ring junction, a 7-en-6-one conjugated system, and polyhydroxyl groups. Accumulated evidences in insects suggest that 20-hydroxyecdysone is biosynthesized from cholesterol via 7-dehydrocholesterol and 3β, 14α-dihydroxy-5β-cholest-7-en-6-one (5β-ketodiol) (Fujtmoto et al. 1997).

It was recently proposed that 3β-hydroxy-5β-cholestan-6-one (5β-ketone) was involved in 20HE biosynthesis in the hairy roots of Ajuga reptans var. atropurpurea (Lamiaceae) (Fujimoto et al. 2015). Cholesterol was converted to the 5β-ketone with the migration of hydrogen from the C-6 to the C-5 position. These findings, along with the previous observation that the ketone was efficiently converted to 20-hydroxyecdysone, strongly suggest that the 5β-ketone is an intermediate immediately formed after cholesterol during 20-hydroxyecdysone biosynthesis in Ajuga sp. (Fujimoto et al. 2015).

It was shown that CYP71D443 has C-22 hydroxylation activity for the 5β-ketone substrate through a yeast expression system. The hydroxylated product, 22-hydroxy-5β ketone, had a 22R configuration in agreement with that of 20E. Furthermore, labeling experiments indicated that (22R)-22-hydroxy-5β-ketone could be converted to 20E in Ajuga hairy roots. Based on those results, a possible 20E biosynthetic pathway in Ajuga plants involved CYP71D443 is proposed (Tsukagoshi et al. 2016).

In contrast to the ability of synthesizing the cholesterol de novo of vertebrate animals and plant, insects must obtain steroid precursor from their diet, which is attributed to the absence of the enzymes involved in squalene synthesis (Kircher 1982; Iga and Kataoka 2012). Carnivorous insects can take cholesterol directly from their prey, whereas in phytophagous insects, phytosterols are the first dealkylated to cholesterol (Gilbert et al. 2002; Gilbert and Warren 2005).

However, it has been proposed that the mechanism of the construction of the characteristic 5β-H-7-en-6-one structure is different in insects and plants (Davies et al. 1980, 1981; Nagakari et al. 1994). It is generally accepted that 7-dehydrocholesterol is derived from cholesterol of insects (Sakurai et al. 1986). Accumulated evidences indicate that the biosynthesis of ecdysone in the prothoracic gland of insects proceeds via 7-dehydrocholesterol and 3β,14α-dihydroxy-5β-cholest-7-en-6-one (ketodiol), followed by the successive hydroxylation at C-25, C-22 and C-2 to yield ecdysone of Ketodiol, which is converted into 20-hydroxyecdysone in peripheral tissues such as the fat-body (Rees 1995; Huang et al. 2008).

The genes encoding the P450 enzymes that catalyze these hydroxylations have been characterized in insects (Huang et al. 2008). Conversion of cholesterol into 7-dehydrocholesterol (7dC) is mediated by a Rieske oxygenase Neverland (Yoshiyama et al. 2006; Yoshiyama-Yanagawa et al. 2011).

In Drosophila melanogaster and Bombyx mori, it has been proven that CYP307A1/A2 (Spook/Spookier, Spo/Spok) and CYP6T3 will be involved in the conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol into 2,22,25-trideoxyecdysone (ketodiol). Moreover, a paralog Spookiest (Spot, CYP307B1) was also found in CYP307 family (Gilbert and Warren 2005; Namiki et al. 2005; Ono et al. 2006; Ou et al. 2011). In contrast, the biosynthetic mechanism of 20-hydroxyecdysone in plants is much less acknowledged than that in insects (Festucci-Buselli et al. 2008). It was shown that hydroxylation of ecdysone at the C-20 position to form 20E is a cytochrome P450-dependent reaction occurring predominantly in the microsomal fraction in spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves (Grebenok et al. 1996). The early step mechanism in Ajuga hairy roots may distinct from that of insects (Lockley et al. 1975; Davies et al. 1981). Ajuga hairy roots are capable of introducing a double bond at the 7-position at the late stage of 20-hydroxyecdysone biosynthesis, suggesting the possibility of an alternative biosynthetic pathway without the involvement of 7-dehydrocholesterol as an obligatory intermediate (Hyodo and Fujimoto 2000).

20-Hydroxyecdysone biosynthesis is mainly through mevalonate (MVA) and DOXP/MEP pathways, in which the former pathway, as a major plant synthetic pathway begins with acetyl CoA condensation, followed by reduction to mevalonate, resulting in the production of steroid ketones and terpenes. Meanwhile, the latter pathway utilizes pyruvic acid and GA-3P as the starting substrates to produce terpenes. Although isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) are intermediate products in both pathways, the mechanisms by which DMAPP and IPP are synthesized are different, so is the intracellular locations of metabolic end products (Adler and Grebenok 1995; Báthori and Pongrácz 2005; Ma et al. 2006).This synthetic pathway is complex with many compounds involved in it, but the specific synthesis pathway of 20E remains unclear (Dinan 2001).

Cholesterol and lathosterol are first metabolized into 7-dehydrocholesterol, followed by the conversion into 20-hydroxyecdysone via 7-dehydrocholesterol 5α, 6α-epoxide in the hairy roots of A. reptans var. atropurpurea (Ohyama et al. 1999). It is generally accepted, both in insects and plants, that the early stage of biosynthesis of 20-hydroxyecdysone from cholesterol yields an intermediate with a cis-A/B ring structure, which is then hydroxylated at the C-2, -20, -22 and -25 positions to furnish. It was reported that C-20, C-22 and C-25 hydroxylations were catalyzed by P450 mono-oxygenase enzymes, whereas a different type mono-oxygenase was responsible for C-2 hydroxylation (Nakagawa et al. 1997).

It was suggested that CYP307A1, CYP307A2 and non-molting glossy/shroud (a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase) should be involved in the conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to 5b-ketodiol (Namiki et al. 2005; Rewitz et al. 2007; Niwa et al. 2010). Functioning as a carbon 25 hydroxylase CYP306A1 plays an essential role in ecdysteroid biosynthesis during insect development, which converts ketodiol into ketotriol via carbon 25 hydroxylation (Niwa et al. 2004). Cytochrome P450 enzymes catalyzing the final steps of ecdysteroid biosynthesis have been identified by mutations in the ‘‘Halloween’’ gene family of D. melanogaster: phantom (CYP306a1; 25-hydroxylase), disembodied (CYP302a1; 22-hydroxylase); shadow (CYP315a1; 2-hydroxylase); and shade (CYP314a1; 20-hydroxylase) (Chavez et al. 2000; Gilbert et al. 2002; Warren et al. 2002, 2004; Petryk et al. 2003; Gilbert 2004; Niwa et al. 2004). The hydroxylation at C25 is mediated by CYP306A1 (Phantom: Phm) located in the endoplasmic reticulum, followed by hydroxylations at C22 and C2 carried out in the mitochondria by CYP302A1 (Disembodied: Dib) and CYP315A1 (Shadow: Sad), respectively (Gilbert and Warren 2005). Final conversion of E to 20E is catalyzed by a fourth hydroxylase, CYP314A1 (Shade: Shd, the ecdysone 20-monooxygenase), variously located in the endoplasmic reticulum and the mitochondria of peripheral target tissues (Petryk et al. 2003).

Abscisic acid could regulate plant dormancy, flowering, maturity, aging and stomatal movement (Cutler et al. 2009), exerting inhibitory effects on cell growth and extension (Hansen and Grossmann 2000). ABA is also considered a stress hormone, the content of which rises under environmental stress, initiating the defense system to enhance plant resistance (Anderson et al. 1994; Hauser et al. 2011; Ren et al. 2012). In recent years, studies have shown that ABA regulates and stimulates the production of secondary metabolites such as chlorogenic acid, phenols, flavonoids and terpenoid substances (Sandhu et al. 2011; Buran et al. 2012). The up-regulation expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGR) are involved in the biosynthesis under the treatment of various elicitors, such as methyl jasmonate (MeJA) or AgNO3, which are responsible for 20E accumulation in cell cultures of Cyanotis arachnoidea (Wang et al. 2014).

In contrast, little is known about the last few steps of planting 20E biosynthesis, and no biosynthetic 20E gene about those steps has been reported thus far (Tsukagoshi et al. 2016). It is based on the establishment of a preliminary suspension culture system of A. lobata (Zhao et al. 2011; Li et al. 2013). Through identifying key genes of the 20E synthesis pathway and assessing their corresponding expression variability after adding exogenous ABA, the study aims to explore the mechanism by which exogenous ABA affects 20E synthesis.

A better understanding of the 20E biosynthetic pathway and its regulation, in particular in plants, is necessary. This is the first report about the isolation, characterization of a novel HMGR gene and the establishment of A. lobata cell suspension cultures for 20E production.

Materials and methods

Materials

The A. lobata cell suspension culture system was established by Insect laboratory of Northeast Forestry University and the suspension culture callus was used as the experimental material.

Methods

A. lobata suspension cell culture and screening for optimal ABA concentration

The basic liquid medium for A. lobata cell suspension culture was Murashige and Skoog culture medium (MS), 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) 0.4 mg/l. The pH was adjusted to 5.8, with an inoculation ratio of 10% (5 g cells in 50 ml medium). Cells were cultured under a 16/8-h light/dark cycle with 2000-l× light intensity at 25 °C and 70% humidity, with culture flasks shaken at 120–130 rpm (Zhao et al. 2011; Li et al. 2013).

ABA was added to the suspension culture system at the seventh day after inoculation of A. lobata cells. Based on previous experiments, ABA concentrations in the suspension cultures were set at 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2 mg/l, respectively, followed by the screen of the optimum concentration of ABA for 20E accumulation. Sampling was carried out every 24 h after ABA addition and 5 parallel samples were collected for each treatment.

Extraction and quantitation of 20E

20E content was assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). A. lobata cells were dried at 60 °C in a high temperature drying oven for 12 h, followed by the operation of soaking 0.2 g dry suspension cell in 5 ml methanol for 24 h, the sonicating for 1 h at 40 kHz (YH-200DH, produced by YUHAO in China), and digested with a microwave digestion system (WT-8000, Shanghai YaRong biochemical instrument factory, conditions: T = 50 °C, p = 2 P0, T = 10 min, W = 300 × 2). The digestion mixtures were filtered using organic filtration membrane. The filtrates were analyzed by HPLC (American, Waters Company) with the following conditions: UV–visible detection wave length range, 190–800 nm; detection wavelength, 242 nm; mobile phase, 1:1 formal dehyde: water; mobile phase flow rate, 0.8 ml/min; injection volume, 10 µl. Samples (5 per treatment group) were collected every 24 h; detection of each standard was repeated 3 times.

20E standards with concentrations of 0.8, 0.4, 0.2, 0.1, and 0.05 g/l were prepared. With average peak area as ordinate and mass concentration as abscissa, a regression equation for 20E was obtained (y = 18498 + 226.2x, R2 = 0.999).

cDNA library construction and transcriptome analysis

Suspension A. lobata cell scultured under the optimal ABA concentration, were screened as described above, with the collection of samples at 48 h after addition of ABA, for of cDNA library construction and transcriptome analysis. In the control group, suspension A. lobata cells were cultured in basic liquid medium. Three samples were collected from untreated or treated suspension A. lobata cells, respectively, mixed and kept separately, and used in subsequent experiments.

Total RNA was isolated from mixed samples using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcriptome sequencing was carried out on Illumina. The Trimmomatic (v0.30) software was used to analyze raw sequencing data, in which adapter and low-quality sequences were removed to obtain clean data for further analysis (Grabherr et al. 2011). Sequencing data quality assessment was carried out with the Fast QC (v0.10.1) software, and TransDecoder was employed for ORF detection (Garg et al. 2011; Ness et al. 2011).

Functional annotation of transcripts was performed using BLASTX to compare nucleotide sequences in the NCBI’s NR protein database (tHoen et al. 2008; Morrissy et al. 2008). All predicted genes were assigned to different functional categories using Blast2GO (http://www.blast2Go.org/) to facilitate global gene expression analysis (Conesa et al. 2005). A categorization into functional groups was performed automatically through the KEGG pathway database, the annotation of which was carried out with the online KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS), using the comparison method for bidirectional best hit (BBH). The functional classification by KEGG provided valuable information for investigating specific processes, functions, and pathways.

Screening of differentially expressed genes

Gene expression data were evaluated using the Rsemsoftware. The DESeq software was used to screen the differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with false discovery rate (FDR) corrected p value of 0.05, with the adoption of a cut off of twofold regulation (Audic and Claverie 1997; Eisen et al. 1998; Saldanha 2004).

Analysis on differentially expressed genes

The identified DEGs were used for GO and KEGG pathway analysis. The GO enrichment analysis on functional significance was performed using the Gene Ontology database (http://www.geneontology.org/), evaluating gene numbers for every term and using a hypergeometric test to identify significantly enriched GO terms in DEGs. The following formula was used. The P-value of a significantly enriched GO term should be lower than 0.05; the P-value was corrected by Bonferroni

N = all genes with a GO annotation, n = DEGsin N, M = all genes annotated to certain GO terms, m = DEGsin M.

Compared with the whole-genome background, the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified significantly enriched metabolic pathways or signal transduction pathways in the DEGs (Kanehisa et al. 2015). The formula of the significantly enriched pathway was the same as that used for GO enrichment analysis.

Results

Effect of ABA on 20E content

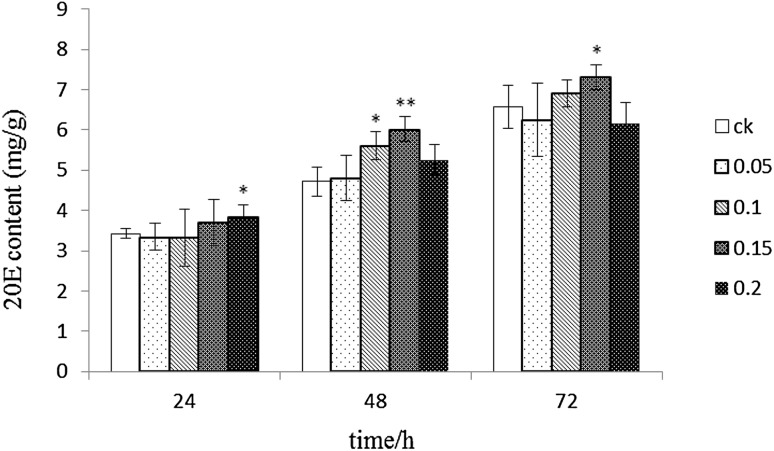

The changes of 20E content are shown in Fig. 1. Treatment with 0.05 mg/l ABA showed no significant difference compared with that in the control group. Meanwhile, 0.1 mg/l ABA showed a significant difference at 48 h (p < 0.05); treatment with 0.15 mg/l ABA showed significant differences compared with that in the control group at 48 and 72 h, with 23.49 and 14.73% higher 20E contents compared with those in the control group respectively. Treatment with 0.2 mg/l ABA showed a trend of decline up to 20E content after an initial increase, with lower amounts than that in the control group at 72 h. Therefore, 0.15 mg/l ABA was selected as the optimal concentration for further experiments.

Fig. 1.

20E contents in different ABA treatment groups. Note: **significant difference between ABA treatment and control groups

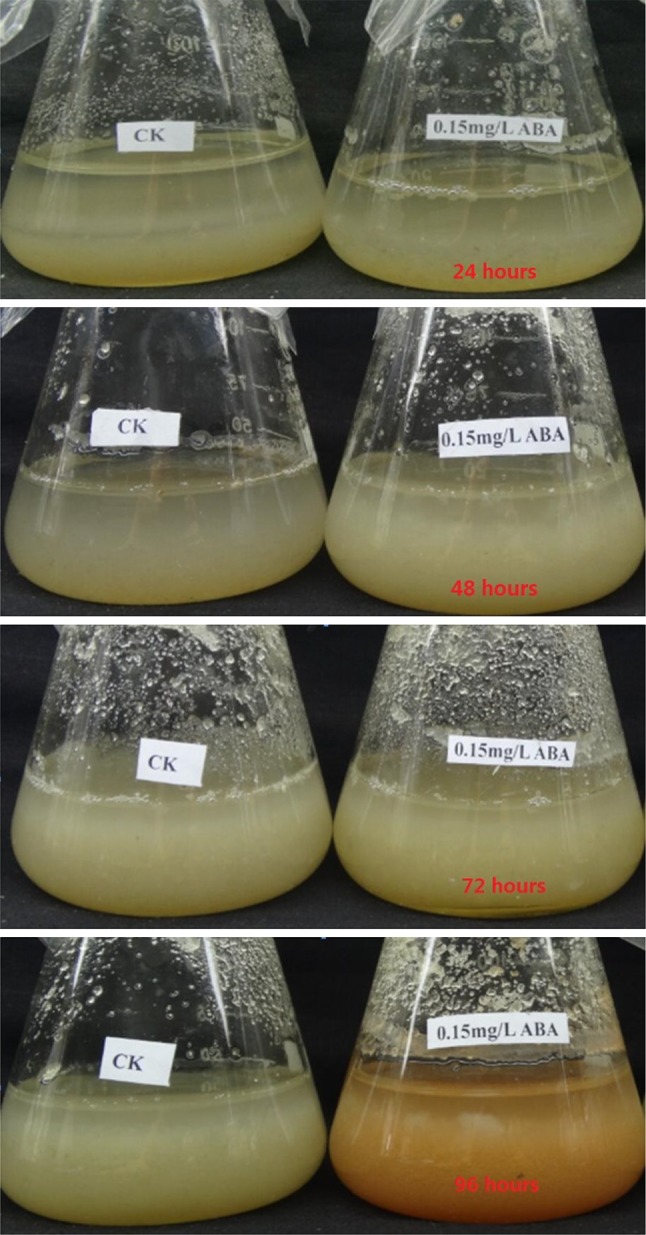

Effect of ABA on A. lobata suspension cell activity

At 72 h, suspension A. lobata cells grew well after the addition of 0.15 mg/l ABA. The suspension culture system was light yellow, uniform and loose. However, A. lobata suspension cells were brown at 96 h. After being treated with ABA, dry weight was increased during the non-browning period. Dry weights were significantly higher than those in the control group at 24 h (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the dry weight at 48 and 72 h between treated and control groups. However dry weights were significantly reduced compared with that in the control group at 96 h (p < 0.05). Growth status is shown in Fig. 2, while biomass changes are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Growth status of A. lobata suspension cells

Table 1.

Cell biomass variations

| Dry cell weight/g | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24th hours* | 48th hours | 72th hours | 96th hours* | |

| CK | 0.480 ± 0.0071 | 0.542 ± 0.0192 | 0.567 ± 0.0157 | 0.635 ± 0.0212 |

| ABA | 0.505 ± 0.0141 | 0.555 ± 0.0096 | 0.577 ± 0.0149 | 0.512 ± 0.0068 |

*Significant difference between ABA treatment and control groups

Illumina sequencing and data analysis

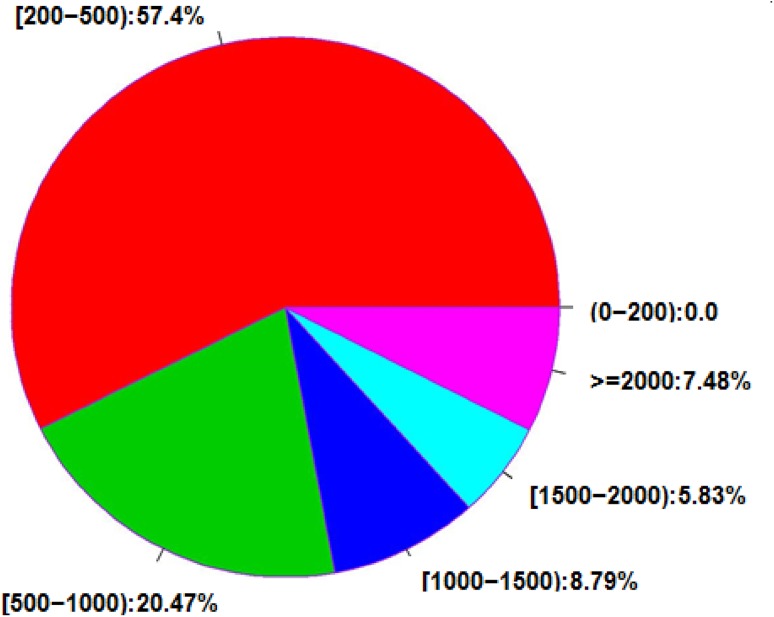

In this study, two cDNA libraries for A. lobata suspension cells treated with 0.15 mg/l ABA for 48 h and untreated, respectively, were generated on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform. The statistics of raw data are shown in Table 2; clean reads were generated after removing adapter sequences, duplicate sequences, ambiguous reads, and low-quality reads (Table 3). Each library reached the saturation level of gene identification and a tag density sufficient for quantitative gene expression analysis. Of all the clean reads, 60.56% were matched to unique genomic locations; the uniquely matched reads were used for gene expression analysis. A comparison of clean reads and unigenesis is shown in Table 4. The distribution of the gene sequence length of all 119,359 genes detected by the RNA-Seq technology is shown in Fig. 3. For these genes, gene sequence length distribution was divided into five grades, along with the presentation of the total numbers and percentages of all genes. The proportion of long sequences was high among these genes, with 26,378 genes exceeding 1000 bp in length.

Table 2.

Statistical table showing raw data

| Sample | Length | Reads | Bases | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | GC (%) | N (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 125 | 53,286,482 | 6,660,810,250 | 97.55 | 95.04 | 45.535 | 561.23 |

| ABA | 125 | 51,046,352 | 6,380,794,000 | 94.23 | 88.49 | 46.5654 | 137.15 |

Table 3.

Statistical table of clean data

| Sample | Length | Reads | Bases | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | GC (%) | N (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 123.43 | 48,405,691 | 5,968,647,065 | 99.32 | 98.11 | 45.34 | 1.14 |

| ABA | 119.95 | 41,896,665 | 5,023,735,715 | 98.235 | 95.21 | 46.155 | 0.455 |

Table 4.

Comparison of clean reads and unigenes

| Samples | Total clean reads | Total mapped | Unique mapped | Multi mapped | Mapped (%) | Unique (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 48,405,691 | 44,820,522 | 35,810,118 | 9,010,404 | 77.86 | 62.20 |

| ABA | 41,896,665 | 30,542,782 | 24,623,874 | 5,918,908 | 73.06 | 58.92 |

Fig. 3.

Unigene interval distribution of different length

Gene expression and functional classification of the detected genes

A total of 45,150 unigenes were annotated to the Nr protein database successfully. Owing to the fact that a gene could be matched to multiple proteins the 45,150 unigenes were matched to 265,156 proteins with data redundancy. A total of 173,520 matched proteins with high homology (E value < 1E−30) making up 65.44% of all proteins. Meanwhile, 122,860 matched proteins showed higher homology (E value < 1E−60), i.e. 46.36% of all proteins. The highest matched species Vitisvinifera accounted for 23.23%, followed by Ricinuscommunis (14.35%), Solanumlycopersicum (14.30%), Populustrichocarpa (8.78%), Prunuspersica (8.35%) and Ricinuscommunis (6.51%), Glycine max (6.34%), Arabidopsis thaliana (3.71%) and Oryza sativa (2.35%).

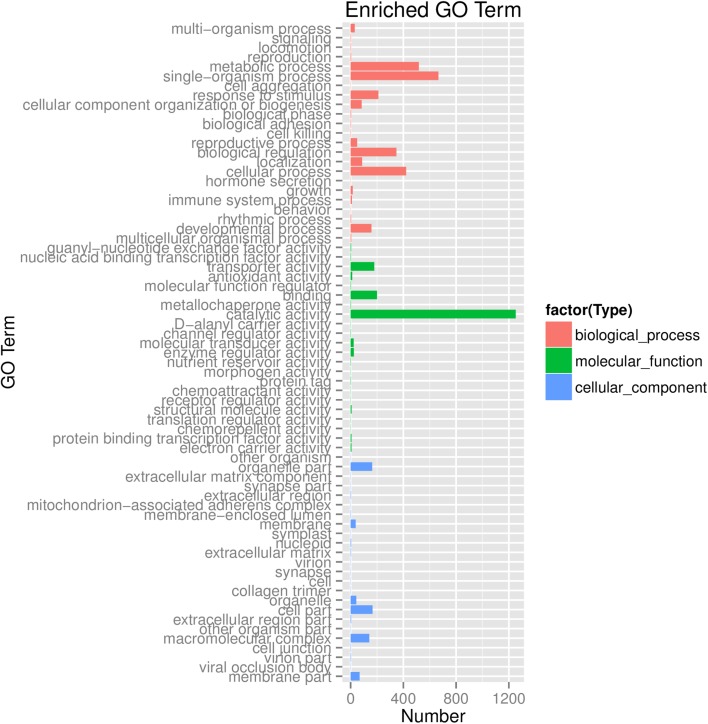

The annotations were verified manually and integrated based on the gene ontology (GO) classification. 24,026 of the detected genes had at least one GO annotation based on sequence similarity. These annotated genes were categorized based on the secondary classification of GO terms, assigning them to 69 functional groups of the three main GO classification categories (Fig. 4). Genes assigned to “cellular component” accounted for the majority of GO terms (24), followed by “biological process” (23) and “molecular function” (22). The terms “single-organism process” and “metabolic process”, accounting for 24.98% and 13.28%, respectively, were the dominant GO terms. The terms “cellular process” (10.31%), “biological regulation” (8.39%) and “response to stimulus” (6.91%) were also common. Only a few genes were clustered in the way of “Channel regulator activity” and “cell killing”.

Fig. 4.

GO function classification of unigenes

Pathway-based analysis can be used to examine the biological functions and interactions of genes. We mapped the detected genes to reference canonical pathways in the KEGG pathway database to perform functional classification and pathway assignment. As a result, 8427 unigenes were assigned to 126 KEGG pathways (Table 5). among which the metabolism pathway was the largest category, followed by the ribosome, spliceosome and purine metabolism pathways. These results indicated that A. lobata cells were involved in the genetic and active metabolic processes. Moreover, in addition to the pathway related to 20E synthesis, terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (50 genes), steroid biosynthesis (21 genes) and steroid hormone biosynthesis (28 genes) pathways were identified.

Table 5.

KEGG pathway analysis

| Pathway ID | Pathway | Number of unigenes |

|---|---|---|

| ko01100 | Metabolic pathways | 2315 |

| ko03010 | Ribosome | 346 |

| ko03040 | Spliceosome | 208 |

| ko00230 | Purine metabolism | 165 |

| ko04141 | Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum | 157 |

| ko00190 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 157 |

| ko03013 | RNA transport | 156 |

| ko00240 | Pyrimidine metabolism | 140 |

| ko00500 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 133 |

| ko04075 | Plant hormone signal transduction | 130 |

| ko04120 | Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis | 120 |

| ko03015 | mRNA surveillance pathway | 110 |

| ko04110 | Cell cycle | 110 |

| ko00010 | Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 109 |

| ko03018 | RNA degradation | 104 |

| ko00520 | Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 101 |

| ko04111 | Cell cycle—yeast | 91 |

| ko04144 | Endocytosis | 90 |

| ko03008 | Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes | 89 |

| ko04626 | Plant-pathogen interaction | 89 |

| ko04146 | Peroxisome | 85 |

| ko00564 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 81 |

| ko00330 | Arginine and proline metabolism | 77 |

| ko04113 | Meiotic division | 75 |

| ko00620 | Pyruvate metabolism | 73 |

| ko00270 | Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 70 |

| ko04145 | Phagosome | 69 |

| ko00480 | Glutathione metabolism | 64 |

| ko00970 | Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 62 |

| ko00860 | Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism | 61 |

| ko00260 | Glycine, serine, threonine metabolism | 60 |

| ko03420 | Nucleotide excision repair | 59 |

| ko00680 | Methane metabolism | 58 |

| ko00980 | Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome | 58 |

| ko00940 | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 57 |

| ko00195 | Photosynthesis | 55 |

| ko00040 | Pentose and glucuronateinterconversions | 55 |

| ko00510 | N-Glycan biosynthesis | 54 |

| ko00710 | Carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms | 54 |

| ko00051 | Fructose and mannose metabolism | 52 |

| ko03440 | Homologous recombination | 52 |

| ko00030 | Pentose phosphate pathway | 52 |

| ko00250 | Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | 51 |

| ko00562 | Inositol phosphate metabolism | 51 |

| ko04142 | Lysosome | 51 |

| ko00630 | Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 51 |

| ko00900 | Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 50 |

| ko03030 | DNA replication | 48 |

| ko00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | 48 |

| ko03022 | Basal transcription factors | 48 |

| ko00020 | Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 47 |

| ko00561 | Glycerolipid metabolism | 46 |

| ko00053 | Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 45 |

| ko03060 | Protein export | 44 |

| ko04130 | SNARE interactions in vesicular transport | 43 |

| ko00400 | Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 43 |

| ko03430 | Mismatch repair | 43 |

| ko03050 | Proteasome | 42 |

| ko00052 | Galactose metabolism | 42 |

| ko00563 | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol(GPI)-anchor biosynthesis | 41 |

| ko03410 | Base excision repair | 40 |

| ko04010 | MAPK signaling pathway | 39 |

| ko00071 | Fatty acid metabolism | 39 |

| ko00280 | Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | 36 |

| ko00640 | Propanoate metabolism | 35 |

| ko00830 | Retinol metabolism | 33 |

| ko00920 | Sulfur metabolism | 33 |

| ko00600 | Sphingolipid metabolism | 33 |

| ko00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | 32 |

| ko00310 | Lysine degradation | 31 |

| ko00061 | Fatty acid biosynthesis | 31 |

| ko00410 | beta-Alanine metabolism | 30 |

| ko00770 | Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 30 |

| ko00513 | Various types of N-glycan biosynthesis | 29 |

| ko00130 | Ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis | 29 |

| ko00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | 29 |

| ko01040 | Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 28 |

| ko00140 | Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 28 |

| ko04650 | Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 28 |

| ko04122 | Sulfur relay system | 27 |

| ko04712 | Circadian rhythm—plant | 27 |

| ko02020 | Two-component system | 26 |

| ko00790 | Folate biosynthesis | 26 |

| ko00592 | alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism | 25 |

| ko00910 | Nitrogen metabolism | 24 |

| ko04140 | Regulation of autophagy | 24 |

| ko00340 | Histidine metabolism | 24 |

| ko00590 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | 22 |

| ko00100 | Steroid biosynthesis | 21 |

| ko00906 | Carotenoid biosynthesis | 20 |

| ko00460 | Cyano amino acid metabolism | 20 |

| ko00670 | One carbon pool by folate | 20 |

| ko00760 | Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism | 20 |

| ko00196 | Photosynthesis antenna proteins | 19 |

| ko00511 | Other glycan degradation | 19 |

| ko00780 | Biotin metabolism | 19 |

| ko00290 | Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis | 19 |

| ko00062 | Fatty acid elongation | 19 |

| ko00624 | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation | 17 |

| ko00730 | Thiamine metabolism | 17 |

| ko02010 | Transporters ABC | 17 |

| ko00960 | Tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis | 16 |

| ko00300 | Lysine biosynthesis | 15 |

| ko00450 | Selenocompound metabolism | 14 |

| ko00591 | Linoleic acid metabolism | 14 |

| ko00904 | Diterpenoid biosynthesis | 11 |

| ko00941 | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 11 |

| ko00750 | Vitamin B6 metabolism | 11 |

| ko00740 | Riboflavin metabolism | 10 |

| ko00603 | Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis - globo series | 10 |

| ko04710 | Circadian rhythm | 10 |

| ko00531 | Glycosaminoglycan degradation | 10 |

| ko00430 | Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 9 |

| ko00440 | Phosphonate and phosphinate metabolism | 9 |

| ko03450 | Non-homologous end-joining | 8 |

| ko00908 | Zeatin biosynthesis | 7 |

| ko00909 | Sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis | 6 |

| ko00073 | Cutin, suberine and wax biosynthesis | 6 |

| ko00785 | Lipoic acid metabolism | 6 |

| ko00514 | Other types of O-glycan biosynthesis | 6 |

| ko00905 | Brassinosteroid biosynthesis | 5 |

| ko00072 | Synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies | 4 |

| ko00944 | Flavone and flavonol biosynthesis | 3 |

| ko00965 | Betalain biosynthesis | 2 |

| ko00942 | Anthocyanin biosynthesis | 1 |

| ko00633 | Nitrotoluene degradation | 1 |

Identification of differentially expressed genes

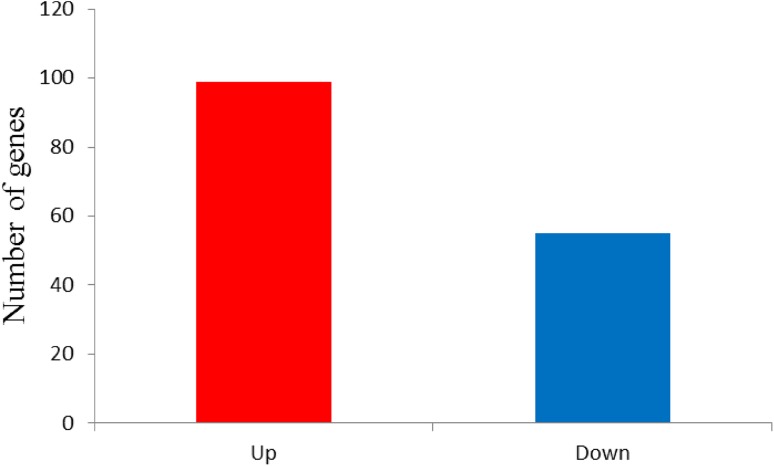

The analysis on differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between samples can be accomplished using RNA-SEq. In this study, DEGs were defined based on fold change of the normalized (RPKM) expression values, leading to the fact that there is a total of 154 genes exhibiting significant differential expression between the two samples. When comparing the control and ABA treatment group libraries, it can be found that 99 genes were up-regulated and 55 down-regulated (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Statistics of DEGs

GO analysis of DEGs

All DEGs were mapped to GO terms in the database based on GO functional classification, followed by the comparison to the genomic background. The GO enrichment analysis on 81 genes is shown in Table 6 (agene could be mapped to multiple GO terms). We categorized the DEGs between the samples according to the secondary GO term classification. In all, 7, 10, and 8 functional groups were in the cellular component, molecular function, and biological process categories, respectively. In the biological process category, “metabolic process” was the dominant group, indicating that extensive metabolic activities occurred in ABA treated A. lobata cells. “Binding” and “catalytic activity” were highly represented in the molecular function category, while “cell part” was dominant in the cellular components category.

Table 6.

Significant differences of the GO terms

| Cluster | GO term | Cluster frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular component | Cell part | 24 out of 24 genes, 100% |

| Intracellular part | 22 out of 24 genes, 91.66% | |

| Cytoplasm | 22 out of 24 genes, 91.66% | |

| Organelle | 18 out of 24 genes, 75% | |

| Membrane-bounded organelle | 16 out of 24 genes, 66.7% | |

| Plastid | 6 out of 24 genes, 25% | |

| Chloroplast | 6 out of 24 genes, 25% | |

| Molecular function | Catalytic activity | 9 out of 22 genes, 40.91% |

| Hydrolase activity | 8 out of 22 genes, 36.36% | |

| Hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds | 6 out of 22 genes, 27.27% | |

| Binding | 9 out of 22 genes, 40.91% | |

| Hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds | 4 out of 22 genes, 18.18% | |

| Ion binding | 3 out of 22 genes, 13.63% | |

| Small molecule binding | 3 out of 22 genes, 13.63% | |

| Nucleotide binding | 3 out of 22 genes, 13.63% | |

| Nucleoside phosphate binding | 3 out of 22 genes, 13.63% | |

| Oxidoreductase activity | 7 out of 22 genes, 31.81% | |

| Biological process | Metabolic process | 32 out of 35 genes, 91.425% |

| primary metabolic process | 27 out of 35 genes, 77.14% | |

| Organic substance metabolic process | 20 out of 35 genes, 61.9% | |

| Response to stimulus | 5 out of 35 genes, 14.28% | |

| Lipid metabolic process | 5 out of 35 genes, 14.28% | |

| Carboxylic acid metabolic process | 6 out of 35 genes, 17.14% | |

| Aromatic compound biosynthetic process | 16 out of 35 genes, 45.71% | |

| Heterocycle biosynthetic process | 14 out of 35 genes, 40% |

KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs

We mapped all DEGs to reference canonical pathways in the KEGG pathway database so as to identify the significantly enriched genes involved in metabolic or signal transduction pathways. By comparing with the whole transcriptome background, 18 pathways were significantly enriched, comprising 112 DEGs (Table 7). Pyrimidine metabolism and nitrogen metabolism pathways were significantly enriched with DEGs followed by RNA polymerase and biosynthesis of amino acids pathways. Among the pathways significantly enriched with DEGs, terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (6 DEGs), steroid biosynthesis (5 DEGs), steroid hormone biosynthesis (6 DEGs) pathways were identified.

Table 7.

Pathways enriched by the differential expression genes

| Pathway ID | Pathway | DEGs with pathway annotation | p value | Q value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ko00603 | Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis—globo series | 1 | 0.89% | 0.01663 | 0.001326 |

| ko00910 | Nitrogen metabolism | 10 | 8.93% | 0.000403 | 0.002689 |

| ko00591 | Linoleic acid metabolism | 1 | 0.89% | 0.000221 | 0.003847 |

| ko04142 | Lysosome | 4 | 3.57% | 0.00183 | 0.004108 |

| ko00710 | Carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms | 5 | 4.46% | 0.00205 | 0.004108 |

| ko03430 | Mismatch repair | 5 | 4.46% | 0.0013 | 0.004108 |

| ko00030 | Pentose phosphate pathway | 6 | 5.36% | 0.00191 | 0.004108 |

| ko00051 | Fructose and mannose metabolism | 7 | 6.25% | 0.00191 | 0.004108 |

| ko03020 | RNA polymerase | 9 | 8.04% | 0.0013 | 0.004108 |

| ko00900 | Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 7 | 6.25% | 0.000757 | 0.007405 |

| ko00010 | Glycolysis /Gluconeogenesis | 7 | 6.25% | 0.00818 | 0.01168 |

| ko00240 | Pyrimidine metabolism | 14 | 12.50% | 0.0133 | 0.015823 |

| ko00230 | Purine metabolism | 8 | 7.14% | 0.0182 | 0.020192 |

| ko01220 | Degradation of aromatic compounds | 3 | 2.68% | 0.01803 | 0.021453 |

| ko01200 | Carbon metabolism | 6 | 5.36% | 0.0257 | 0.027032 |

| ko00100 | Steroid biosynthesis | 4 | 3.57% | 0.01453 | 0.033462 |

| ko00140 | Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 6 | 5.36% | 0.019623 | 0.037926 |

| ko01230 | Biosynthesis of amino acids | 9 | 8.04% | 0.0335 | 0.047735 |

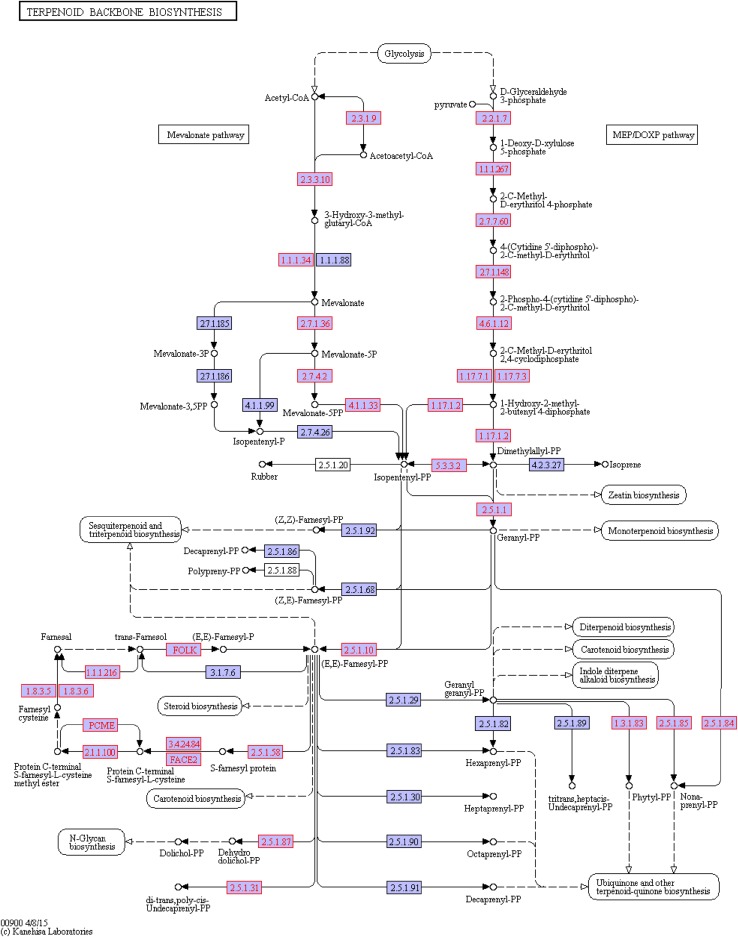

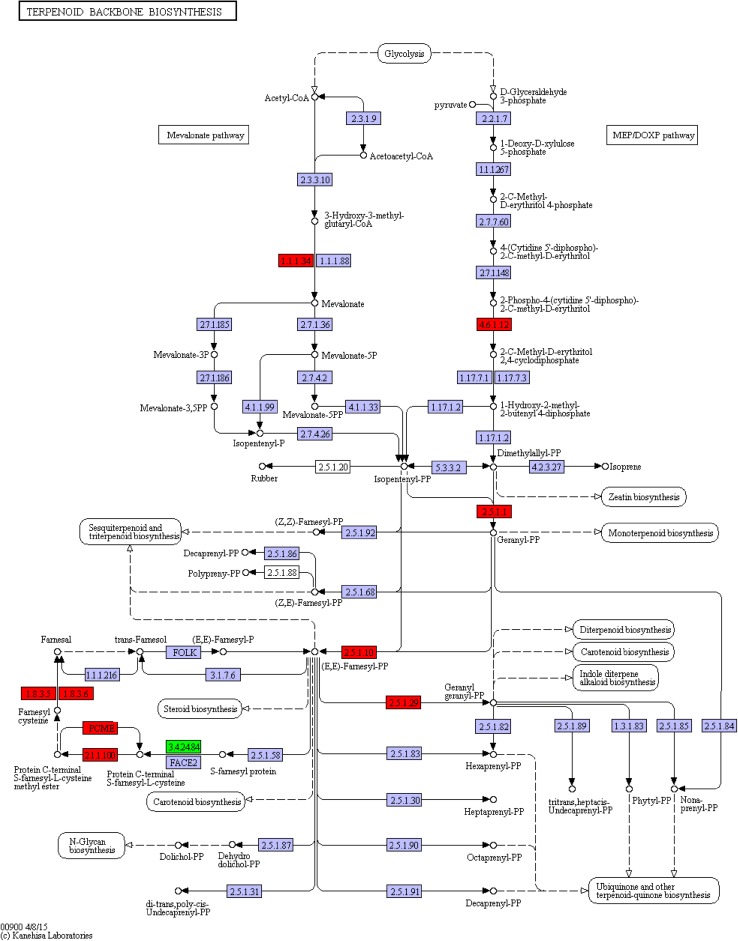

KEGG pathway analysis of genes related to 20E synthesis

The terpenoid backbone biosynthesis can be completed through (ko00900) two sub-pathways, namely MVA and DOXP/MEP sub-pathways (Fig. 6). The former starts with acetyl CoA condensation, while the latter with Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GA-3P). The terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathway ends with IPP and moves into the next pathway (ko00100). Compared with the ko00900 pathway of untreated A. lobata suspension cells, the terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathway had 5 genes up-regulated and 1 down-regulated after ABA treatment (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

The ko00900 pathway in untreated A. lobata suspension cells. Note: the genes in untreated A. lobata suspension cell cDNA library in the pathway are shown in red. Same below

Fig. 7.

DEGs were annotated to the ko00900 pathway. Note: red, up-regulated gene; green, down-regulated gene. Same below

Corresponding to EC:1.1.1.34, the c49795_g1_i1gene was up-regulated, along with the identification as the Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) gene of the MVA pathway. NADPHisa, the key enzyme in the MVA pathway, converts HMF-CoA to mevalonate.

The c29419_g1_i1 gene (EC:4.6.1.12) was up-regulated, along with the identification as the 2C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (MCS) gene of the DOXP/MEP pathway. MCS gene function is to convert 2-phospho-4-(cytidine5′-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-d-erythritol to 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol2,4-cyclicphosphate.

The c44766_g1_i6 gene (EC:4.6.1.12,EC:1.8.3.5) was up-regulated, and identified as the Alpha farnesene synthesis (AFS) gene, which is the intermediate enzyme in farnesyl cysteine synthesis.

The c45098_g1_i1 and c73678_g1_i1 genes (EC:2.5.1.1,EC:2.5.1.10 and EC:2.5.1.29) genes, both corresponded to geranyl geranylpyrophosphate synthetase II (GGPPS) gene, were up-regulated. The enzymatic function of GGPPS is to produce geranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP).

The c81295_g1_i1gene (EC:3.4.24.84) was down-regulated, and identified as the ste24 endopeptidase gene, which is an intermediate enzyme in farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) synthesis.

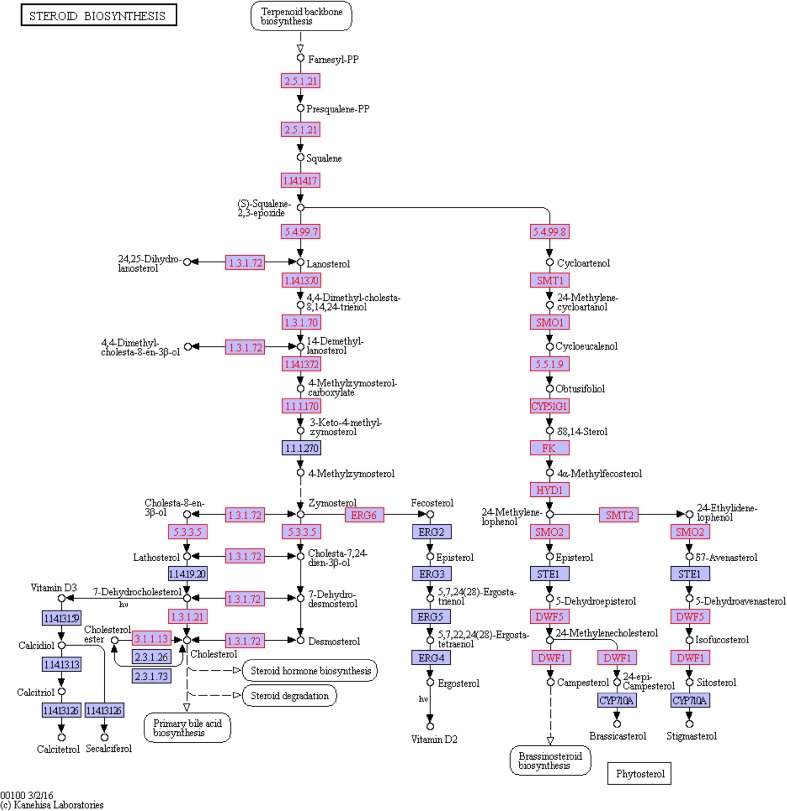

Next to the ko00900 pathway was the steroid biosynthesis pathway (ko00100) beginning with IPP, with squalene as intermediate, and steroid compounds as end products (Fig. 8). The steroid biosynthesis pathway had 4 genes up-regulated and 1down-regulated (Fig. 9); only c27194_g1_i2 (EC:1.1.1.170) and c34855_g1_i (EC:1.14.13.72) genes, both modifiers in the process of squalene related synthesis of steroid substances, were related to the synthesis of steroid hormones. Those two genes were both modifiers in the process of. The c27194_g1_i2 gene was identified as the 4α-carboxylic acid 3 dehydrogenase gene, while the c34855_g1_i gene was the methyl oxidase gene, which were associated with brassino steroid synthesis.

Fig. 8.

The ko00100 pathway in untreated A. lobata suspension cells

Fig. 9.

DEGs annotated to the ko00100 pathway

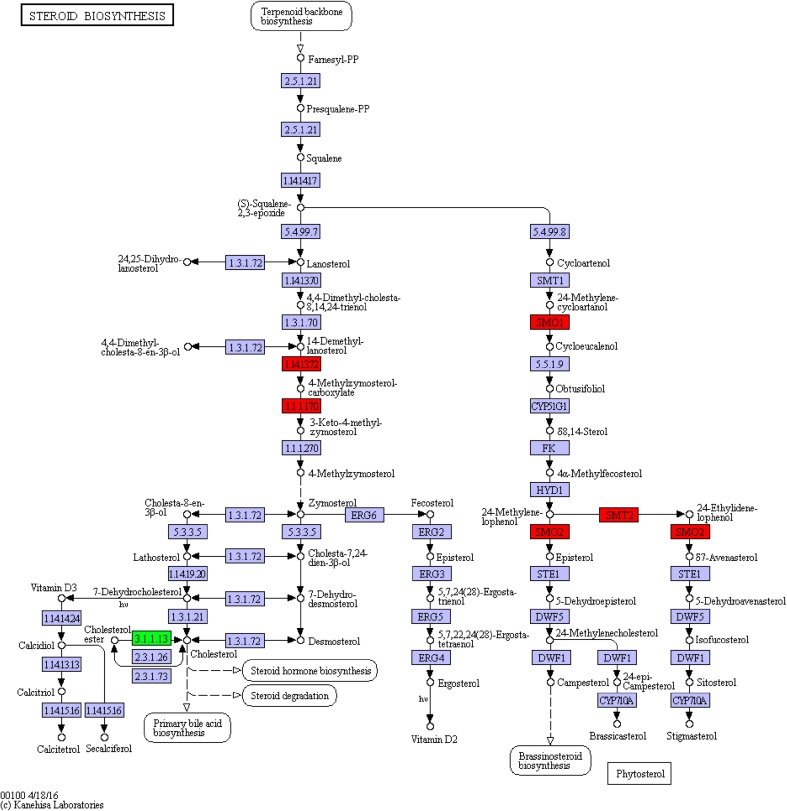

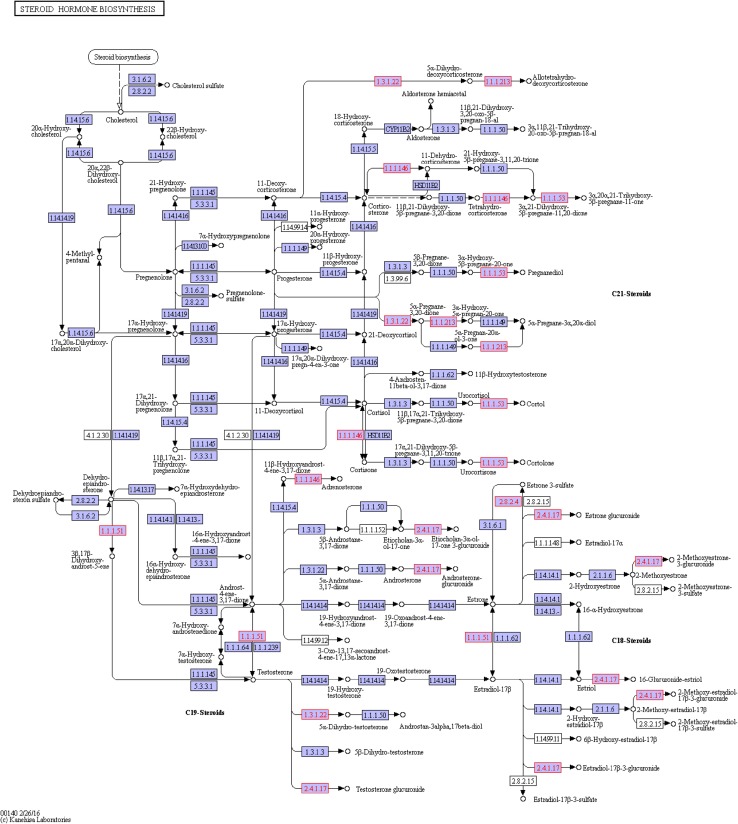

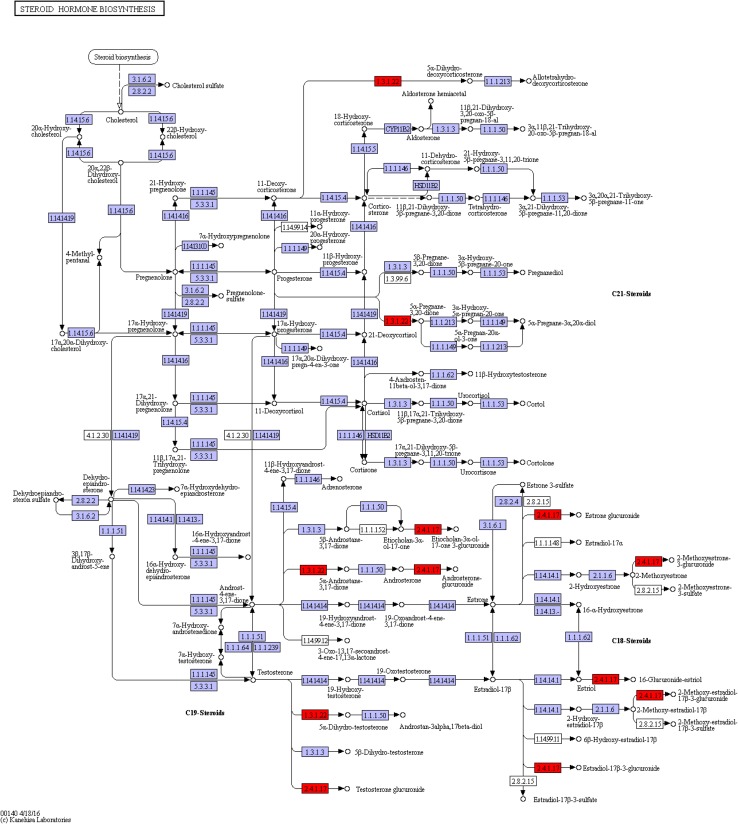

Next was the steroid hormone biosynthesis (ko00140) pathway (Fig. 10). After analysis, we found six DEGs that were all modifiers in the process of squalene related synthesis of steroid substances with a total of five genes up-regulated and one down-regulated (Fig. 11). Currently, the KEGG pathway database has not fully included the 20E pathway, and 20E synthetic steroid is similar to hormone synthesis included by ko00140; therefore, these genes were annotated to the ko00140 pathway with similar functions. Corresponded to the glucuronide transferase gene, the c47715_g1_i2,c47715_g1_i3, c47715_g1_i6 and c47715_g1_i7(EC:2.4.1.17) genes were up-regulated. The c21475_g1_i1 gene (EC:1.3.1.22 and1.3.1.94) was up-regulated, with identification as polyprenol reductase gene while the c40828_g1_i6gene (EC:2.4.1.17) was down-regulated, with the identification as the glucuronide transferase gene.

Fig. 10.

The ko00140 pathway in untreated A. lobata suspension cells

Fig. 11.

DEGs annotated to the ko00140 pathway

Discussion

Treatment with 0.15 mg/l ABA of A. lobata suspension cultures could promote 20E content increase in the short term but was not suitable for long-term culture, and browning was observed. In Wang et al. (2018) study, the browning also happened, which might be caused by the toxicity of ABA. In recent years, studies have shown that ABA can regulate and stimulate the production of secondary metabolites such as chlorogenic acid, phenols, flavonoids and terpenoid substances (Sandhu et al. 2011; Buran et al. 2012). The increase of these secondary metabolites is related to ABA stress inducing the defense system. It was also found that stimulus response genes differentially expressed after ABA treatment, but the relationship between stimulus response and 20E synthesis still needs further exploration.

ABA can inhibit growth, causing premature cell aging, which is responsible for the fact that A. lobata suspension cells turned brown after ABA treatment (Hansen and Grossmann 2000; Hunter et al. 2004). On the other hand, ABA produced stress stimulate the cells, and stress stimulation could promote cell browning (Dai et al. 2016). This might be one of the main causes of the browning phenomenon.

It was found in the studies 20E is mainly synthetized through the MVA and DOXP/MEP pathways. However, the full 20E synthesis pathway remains unclear; the pathways from squalene to 20E are not completely described (Adler and Grebenok 1995; Dinan 2001; Báthori and Pongrácz 2005; Ma et al. 2006). In the KEGG pathway database, we only found ko00900 and ko00100 pathways to produce squalene utilizing pyruvic acid and GA-3Pas starting points. Without including the pathway from squalene to 20E, the KEGG pathway database contains a pathway from squalene to other sterol hormones (ko00140). A. lobata cDNA library has similar genes in the ko00140 pathway. NADPH, MCS, AFS, GGPPS and STE24 endopeptidase genes in the ko00900 pathway of DEGs were all synthetase genes (Bach 1987; Adam and Zapp 1998; Kim et al. 2014; Liao et al. 2014). The 4α-carboxylic acid 3 dehydrogenase and methyl oxidase genes in the ko00100 pathway of DEGs were modifier genes. The DEGs similar to the genes in the ko00140 pathway were modifier genes widespread in plant secondary metabolism (glucuronide transferase genes). The function of those genesis glycosylation is to add sugar molecules on specific sites of metabolites (Mackenzie et al. 1997; Gachon et al. 2005; Asada et al. 2013). Glycosyl transferase has high specificity (Coutinho et al. 2003). Therefore, the relationship between glycosyl transferase gene modification and 20E synthesis also needs to be further explored.

Conclusions

The study found that ABA promoted 20E accumulation. A total of 154 genes were significantly regulated after ABA treatment, with 99 up-regulated and 55 down-regulated, respectively. In addition to 20E-related pathways, the genes belonged to the ko00900 (terpenoid backbone biosynthesis) pathway (six differentially expressed genes [DEGs]), ko00100 (steroid biosynthesis) pathway (four DEGs), and ko00140 (steroid hormone biosynthesis) pathway (six DEGs). It is hoped that these results can offer a strategy to explore a way to regulate the 20E accumulation from the molecular biological angle.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant no.: 31370649).

Abbreviations

- 20E

20-Hydroxyecdysone

- MVA

Mevalonic acid

- DOXP/MEP

5-Phosphate-d-deoxyxylulose/2-C-methy-d-erythritol-4-phosphate

- DMAPP

Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate

- IPP

Isopentenyl pyrophosphate

- MS

Murashige and Skoog culture medium

- 2,4-D

2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adam KP, Zapp J. Biosynthesis of the isoprene units of chamomile sesquiterpenes. Phytochemistry. 1998;48(6):953–959. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00992-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adler JH, Grebenok RJ. Biosynthesis and distribution of insect-molting hormones in plants—a review. Lipids. 1995;30(3):257–262. doi: 10.1007/BF02537830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MD, Prasad TK, Martin BA, Stewart CR. Differential gene expression in chilling-acclimated maize seedlings and evidence for the involvement of abscisicacid in chilling tolerance. Plant Physiol. 1994;105(1):331–339. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K, Salim V, Masada-Atsumi S, Edmunds E, Nagatoshi M, Terasaka K, Mizukami H, De Lucab V. A 7-deoxyloganetic acid glucosyltransferase contributes a key step in secologanin biosynthesis in Madagascar periwinkle. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):4123–4134. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.115154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audic S, Claverie JM. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7(10):986–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach TJ. Synthesis and metabolism of mevanoic acid in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1987;35(25):163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Báthori M, Pongrácz Z. Phytoecdysteroids from isolation to their effects on humans. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12(2):153–172. doi: 10.2174/0929867053363450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buran TJ, Sandhu AK, Azeredo AM, Bent AH, Williamson JG, Gu LW. Effects of exogenous abscisic acid on fruit quality, antioxidant capacities and phytochemical contents of southern high bush blueberrie. Food Chem. 2012;132(3):1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai ZY, Yi GQ, Li YY. Nuclear magnetic resonance characteristics of neo-clerodane diterpene in Genus Ajuga. Cent South Pharm. 2014;12(11):1108–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez VM, Marques G, Delbecque JP, Kobayashi K, Hollingsworth M, Burr J, Natzle JE, O’Connor MB. The Drosophila disembodied gene controls late embryonic morphogenesis and codes for a cytochrome P450 enzyme that regulates embryonic ecdysone levels. Development. 2000;127:4115–4126. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll J, Tandron YA. neo-Clerodane diterpenoids from Ajuga: structural elucidation and biological activity. Phytochem Rev. 2008;7(1):25–49. doi: 10.1007/s11101-006-9023-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coll J, Tandron YA, Zeng X. New phytoecdysteroids from cultured plants of Ajuga nipponensis Makino. Steroids. 2007;72(3):270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho PM, Deleury E, Davies GJ, Henrissat B. An evolving hierarchical family classification for glycosyltransferases. J Mol Biol. 2003;328(2):307–317. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SR, Rodriguez PL, Finkelstein RR, Abrams SR. Abscisicacid: emergence of a core signaling network. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;61(1):651–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Yang SH, Zhao HZ, Zhao LH. Research progress on browning phenomenon in tissue culture of medicinal plants. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs. 2016;47(2):344–351. [Google Scholar]

- Davies TG, Lockley WJS, Boid R, Rees HH, Goodwin TW. Mechanism of formation of the A/B cis ring junction of ecdysteroids in Polypodium vulgare. Biochem J. 1980;190:537–544. doi: 10.1042/bj1900537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies TG, Dinan LN, Lockley WJS, Rees HH, Goodwin TW. Formation of the A/B cis ring junction of ecdysteroids in the locust, Schistocerca gregaria. Biochem J. 1981;194:53–62. doi: 10.1042/bj1940053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan L. Phytoecdysteroids: biological aspects. Phytochemistry. 2001;57(3):325–339. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(25):14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete G, Polgár LA, Báthori M, Col J, Darvas B. Per os efficacy of Ajuga extracts against sucking insects. Pest Manag Sci. 2004;60(11):1099–1104. doi: 10.1002/ps.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festucci-Buselli RA, Contim LAS, Barbosa LCA, Stuart J, Otoni WC. Biosynthesis and potential functions of the ecdysteroid 20-hydroxyecdysone—a review. Botany. 2008;86:978–982. doi: 10.1139/B08-049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto Y, Maeda I, Ohyama K, Hikiba J, Kataoka H. Biosynthesis of 20-hydroxyecdysone in plants: 3β-hydroxy-5β cholestan-6-one as an intermediate immediately after cholesterol in Ajuga hairy roots. Phytochemistry. 2015;111:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujtmoto Y, Kushiro T, Nakamura K. Biosynthesis of 20-hydroxyecdysone in Ajuga hairy roots: hydrogen migration from C-6 to C-5 during cis. A/B ring formation. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38(15):2697–2700. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00432-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gachon CM, Langlois-Meurinn M, Saindrenan P. Plant secondary metabolism glycosyl transferases: the emerging functional analysis. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10(11):542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R, Patel RK, Tyagi AK, Jain M. De novo assembly of chickpea transcriptome using short reads for gene discovery and marker identification. DNA Res. 2011;18(1):53–63. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LI. Halloween genes encode P450 enzymes that mediate steroid hormone biosynthesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;215:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LI, Warren JT. A molecular genetic approach to the biosynthesis of the insect steroid molting hormone. In: Litwack G, editor. Insect hormones—vitamins and hormones. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 31–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LI, Rybczynski R, Warren JT. Control and biochemical nature of the ecdysteroidogenic pathway. Annu Rev Entomol. 2002;47(47):883–916. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng QD, Chen ZH, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, diPalma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebenok RJ, Galbraith DW, Benveniste I, Feyereisen R. Ecdysone 20-monooxygenase, a cytochrome P450 enzymes from spinach, Spinacia oleracea. Phytochemistry. 1996;42:927–933. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(96)00094-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo XD, Huang ZS, Bao YD, An LK, Ma L, Gu LQ. Chemical constituents of Ajuga decumbens. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs. 2005;36(5):646–648. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H, Grossmann K. Auxin-induced ethylene triggers abscisic acid biosynthesis and growth inhibition. Plant Physiol. 2000;124(3):1437–1448. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.3.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser F, Waadt R, Schroeder J. Evolution of abscisic acid synthesis and signaling mechanisms. Curr Biol. 2011;21(9):346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Warren JT, Gilbert LI. New players in the regulation of ecdysone biosynthesis. J Genet Genom. 2008;35(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DA, Ferrante A, Vernieri P, Reid MS. Role of abscisic acid in perianth senescence of daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus ‘Dutch Master’) Physiol Plant. 2004;121(2):313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.0311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyodo R, Fujimoto Y. Biosynthesis of 20-hydroxyecdysone in Ajuga hairy roots: the possibility of 7-ene introduction at a late stage. Phytochemistry. 2000;53(7):733–737. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iga M, Kataoka H. Recent studies on insect hormone metabolic pathways mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35(6):838–843. doi: 10.1248/bpb.35.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Okuda S, Tokimatsu T, Yamanishi Y. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;36:53–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Lee OR, Oh JY, Jang MG, Yang DC. Functional analysis of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase encoding genes in riterpene saponin-producing ginseng. Plant Physiol. 2014;165(1):373–387. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.222596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher HW. Sterols and insects. In: Dupont J, editor. Cholesterol systems in insects and animals. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Inc.; 1982. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lev SV, Zakirova RP, Saatov Z, Gorovits MB, Abubakirov NK. Ecdysteroids from tissue and cell cultures of Ajuga turkestanica. Chem Nat Compd. 1990;26(1):40–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00605197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Qian JJ, Li XC, Yan SC, Chi DF. A study on edysterone production of Ajuga lobata D. Don cell lines in suspension culture. Chin Agric Sci Bull. 2013;29(34):127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Liao P, Wang H, Hemmerlin A, Nagegowda DA, Bach TJ, Wang M, Chye ML. Past achievements, current status and future perspectives of studies on 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMGS) in the mevalonate (MVA) pathway. Plant Cell Rep. 2014;33(7):1005–1022. doi: 10.1007/s00299-014-1592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockley WJS, Boid R, Lloyd-Jones GJ, Rees HH, Goodwin TW. Fate of the C-4 hydrogen atoms of cholesterol during its transformation into ecdysones in insects and plants. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1975;9(9):346–348. doi: 10.1039/c39750000346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Ding P, Yang GX, He GY. Advances on the plant terpenoid isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway and its key enzymes. Biotechnol Bull. 2006;1(C00):22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie PI, Owens IS, Burchell B, Bock KW, Bairoch A, Bélanger A, Fournel-Gigleux S, Green M, Hum DW, Iyanagi T, Lancet D, Louisot P, Magdalou J, Chowdhury JR, Ritter JK, Schachter H, Tephly TR, Tipton KF, Nebert DW. The UDP glycosyltransferase gene superfamily: recommended nomenclature update based on evolutionary divergence. Pharmacogenet Genom. 1997;7(4):255–269. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion-Poll F, Dinan L, Lafont R. The role of phytoecdysteroids in the control of phytophagous insects. In: Regnault-Roger C, Philogène BJR, Vincent C, editors. Biopesticides of Plant Origin. Paris France: Lavoisier Publishing; 2005. pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissy AS, Morin RD, Delaney A, Zeng T, McDonald H, Jones S, Zhao Y, Hirst M, Marra MA. Next-generation tag sequencing for cancer gene expression profiling. Genome Res. 2008;19(10):1825–1835. doi: 10.1101/gr.094482.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagakari M, Kushiro T, Yagi T, Tanaka N, Matsumoto T, Kakinuma K, Fujimoto Y. 3β-Hydroxy-5β-cholest-7-en-6-one as an intermediate of 20-hydroxyecdysone biosynthesis in a hairy root culture of Ajuga reptans var. atropurpurea. Cheminform. 1994;25(51):1761–1762. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Hara N, Fujimoto Y. Biosynthesis of 20-hydroxyecdysone in Ajuga hairy roots: stereochemistry of C-25 hydroxylation. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38(15):2701–2704. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00433-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Namiki T, Niwa R, Sakudoh T, Shirai K, Takeuchi H, Kataoka H. Cytochrome P450 CYP307A1/Spook: a regulator for ecdysone synthesis in insects. Biochem Biophy Res Co. 2005;337(1):367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness RW, Siol M, Barrett SC. De novo sequence assembly and characterization of the floral transcriptome in cross-and self-fertilizing plants. BMC Genom. 2011;12(1):298. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa R, Matsuda T, Yoshiyama T, Namiki T, Mita K, Fujimoto Y, Kataoka H. CYP306A1, a cytochrome P450 enzyme, is essential for ecdysteroid biosynthesis in the prothoracic glands of Bombyx and Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(34):35942–35949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404514200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa R, Namiki T, Ito K, Shimada-Niwa Y, Kiuchi M, Kawaoka S, Kayukawa T, Banno Y, Fujimoto Y, Shigenobu S, Kobayashi S, Shimada T, Katsuma S, Shinoda T. Non-molting glossy/shroud encodes a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase that functions in the ‘Black Box’ of the ecdysteroid biosynthesis pathway. Development. 2010;137(12):1991–1999. doi: 10.1242/dev.045641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama K, Kushiro T, Nakamura K, Fujimoto Y. Biosynthesis of 20-hydroxyecdysone in Ajuga hairy roots: Fate of 6α- and 6β-hydrogens of lathosterol. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:2925–2930. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0896(99)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono H, Rewitz KF, Shinoda T, Itoyama K, Petryk A, Rybczynski R, Jarcho M, Warren JT, Marqués G, Shimell MJ. Spook and Spookier code for stage-specific components of the ecdysone biosynthetic pathway in Diptera. Dev Biol. 2006;298(2):555–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Q, Magico A, King-Jones K. Nuclear receptor DHR4 controls the timing of steroid hormone pulses during Drosophila development. Plos Biol. 2011;9(9):e1001160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petryk A, Warren JT, Marques G, Jarcho MP, Gilbert LI, Kahler J, Parvy JP, Li Y, Dauphin-Villemant C, O’Connor MB. Shade is the Drosophila P450 enzyme that mediates the hydroxylation of ecdysone to the steroid insect molting hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(24):13773–13778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336088100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees HH. Ecdysteroid biosynthesis and inactivation in relation to function. Eur J Entomol. 1995;92:9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ren F, Zhang RJ, Chen Q. Progress in ABA and SA improving plant drought resistance and salt resistance. Biotechnol Bull. 2012;29(3):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rewitz KF, O’Connor MB, Gilbert LI. Molecular evolution of the insect Halloween family of cytochrome P450s: phylogeny, gene organization and functional conservation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37(8):741–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rharrabe K, Sayah F, LafontLauber R. Dietary effects of four phytoecdysteroids on growth and development of the Indian meal moth, Plodia interpunctella. J Insect Sci. 2009;10(2):259–272. doi: 10.1673/031.010.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai S, Yonemura N, Fujimoto Y, Hata F, Ikekawa N. 7-Dehydrosterols in prothoracic glands of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Experientia. 1986;42(9):1034–1036. doi: 10.1007/BF01940720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha AJ. Java Treeview extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):3246–3248. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu AK, Gray DJ, Lu J, Gu LW. Effects of exogenous abscisic acid on antioxidant capacities anthocyanins and flavonol contents of muscadine grape (Vitisrotundifolia) skins. Food Chem. 2011;126(3):982–988. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.11.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj P, John de Britto A, Sahayaraj K. Phytoecdysone of Pteridium aquilinum (L) Kuhn (Dennstaedtiaceae) and its pesticidal property on two major pests. Arch Phytopathol Plant Prot. 2007;38(2):99–105. doi: 10.1080/0323540040007517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- tHoen PA, Ariyurek Y, Thygesen HH, Vreugdenhil E, Vossen RH, de Menezes RX, Boer JMvanOmmen GJ, den Dunnen JT. Deep sequencing-based expression analysis shows major advances in robustness, resolution and inter-lab portability over five microarray platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(21):e141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukagoshi Y, Ohyama K, Seki H, Akashi T, Muranaka T, Suzuki H, Fujimoto Y. Functional characterization of CYP71D443, a cytochrome P450 catalyzing C-22 hydroxylation in the 20-hydroxyecdysone biosynthesis of Ajuga hairy roots. Phytochemistry. 2016;127:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufimtsev KG, Shirshova TI, Yakimchuk AP. Effect of ecdysteroids of Serratula coronata L. on development of larvae of the Egyptian cotton leafworm. Rastitelnye Resursy. 2003;39(4):134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wang QJ, Zheng LP, Sima YH, Yuan HY, Wang JW. Methyl jasmonate stimulates 20-hydroxyecdysone production in cell suspension cultures of Achyranthes bidentata. Plant Omics. 2013;6(2):116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang QJ, Zheng LP, Zhao PF, Zhao YL, Wang JW. Cloning and characterization of an elicitor-responsive gene encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase involved in 20-hydroxyecdysone production in cell cultures of Cyanotis arachnoidea. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2014;84:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Zhao JJ, Chi DF. β-ecdysterone accumulation and regulation in Ajuga multiflora bunge suspension culture. 3Biotech. 2018;8(2):87. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1117-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JT, Petryk A, Marques G, Jarcho M, Parvy JP, Dauphin-Villemant C, O’Connor MB, Gilbert LI. Molecular and biochemical characterization of two P450 enzymes in the ecdysteroidogenic pathway of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(17):11043–11048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162375799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JT, Petryk A, Marques G, Parvy JP, Shinoda T, Itoyama K, Kobayashi J, Jarcho M, Li Y, O’Connor MB, Dauphin-Villemant C, Gilbert LI. Phantom encodes the 25-hydroxylase of Drosophila melanogaster and Bombyx mori: a P450 enzyme critical in ecdysone biosynthesis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34(9):991–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Qu W, Liang J. Progress on chemical constituents and biological activities of the genus Ajuga. Strait Pharm J. 2012;24(2):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiyama T, Namiki T, Mita K, Kataoka H, Niwa R. Neverland is an evolutionally conserved Rieske-domain protein that is essential for ecdysone synthesis and insect growth. Development. 2006;133(13):2565–2574. doi: 10.1242/dev.02428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiyama-Yanagawa T, Enya S, Shimada-Niwa Y, Yaguchi S, Haramoto Y, Matsuya T, Shiomi K, Sasakura Y, Takahashi S, Asashima M. The conserved rieske oxygenase DAF-36/neverland is a novel cholesterol-metabolizing enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(29):25756–25762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.244384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XJ, Li XC, Yu J, Chi DF. Effects of growth regulator and culture methods on rooting of Ajuga lobata and content of β-ecdysone. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs. 2011;42(9):1828–1832. [Google Scholar]