Abstract

Vascular dysfunction represents a critical preclinical step in the development of cardiovascular disease. We examined the role of the gut microbiota in the development of obesity-related vascular dysfunction. Male C57BL/6J mice were fed either a standard diet (SD) (n = 12) or Western diet (WD) (n = 24) for 5 mo, after which time WD mice were randomized to receive either unsupplemented drinking water or water containing a broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail (WD + Abx) (n = 12/group) for 2 mo. Seven months of WD caused gut dysbiosis, increased arterial stiffness (SD 412.0 ± 6.0 vs. WD 458.3 ± 9.0 cm/s, P < 0.05) and endothelial dysfunction (28% decrease in max dilation, P < 0.05), and reduced l-NAME-inhibited dilation. Vascular dysfunction was accompanied by significant increases in circulating LPS-binding protein (LBP) (SD 5.26 ± 0.23 vs. WD 11 ± 0.86 µg/ml, P < 0.05) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (SD 3.27 ± 0.25 vs. WD 7.09 ± 1.07 pg/ml, P < 0.05); aortic expression of phosphorylated nuclear factor-κB (p-NF-κB) (P < 0.05); and perivascular adipose expression of NADPH oxidase subunit p67phox (P < 0.05). Impairments in vascular function correlated with reductions in Bifidobacterium spp. Antibiotic treatment successfully abrogated the gut microbiota and reversed WD-induced arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction. These improvements were accompanied by significant reductions in LBP, IL-6, p-NF-κB, and advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and were independent from changes in body weight and glucose tolerance. These results indicate that gut dysbiosis contributes to the development of WD-induced vascular dysfunction, and identify the gut microbiota as a novel therapeutic target for obesity-related vascular abnormalities.

Keywords: arterial stiffness, endothelial function, microbiota, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal microbes have emerged as critical regulators of human physiology (26). Disturbances to microbial equilibrium, broadly termed gut dysbiosis, have been linked to numerous disease processes (10). Diet is one of the most important determinants of microbial equilibrium, and dysbiosis that occurs secondary to a high-fat or Western (high fat, high sugar) diet has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several diet-related diseases, including diabetes, steatohepatitis, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (6).

Studies examining a link between the microbiota and CVD have focused primarily on hypertension and atherosclerosis (1, 16, 25, 46, 60, 72). However, numerous preclinical disturbances in the vasculature develop before overt atherosclerotic lesions. Among these disturbances, arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction are perhaps the most common and clinically relevant. Arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction are observed following Western diet feeding, and both are strong predictors of future cardiovascular events and mortality (13, 68). In light of this clinical importance, considerable attention has been given to identifying the cellular pathways that underlie the development of obesity-related arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction. In this regard, numerous studies in humans and experimental animals have shown that oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling are two critical mediators of vascular dysfunction (14, 18, 19, 31, 39, 51), although the initial source(s) of this oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling is still unclear.

Recent data indicate that gut dysbiosis may represent a novel source of oxidative stress and inflammation that could influence vascular function. For example, several microbial metabolites and structural bacterial components are capable of migrating from the intestinal environment and eliciting inflammation and oxidative stress within metabolically relevant tissues, including the vasculature (7, 8, 32, 65). Despite these data, there is limited evidence to support a role of the gut microbiota in the development of endothelial dysfunction (12, 63), and to our knowledge, no data are available regarding the effects of dysbiosis on arterial stiffness. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to determine the effects of suppressing gut dysbiosis, via a broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail, on arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction in Western diet-fed mice; and to examine potential factors that mediate gut-vascular crosstalk downstream of dysbiosis. Our results indicate that microbiota suppression improves both Western diet-induced arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction, and identify putative signals within the gut, the circulation, and the vasculature and perivascular adipose tissue that may mediate these vascular alterations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design.

Male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and acclimated for 2 wk with ad libitum access to a standard diet (SD; TD.08113, Harlan Laboratories) consisting of 10.2% fat, 76.0% carbohydrate, and 13.8% protein calories. Mice were individually housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Once acclimated, 3-mo-old mice were randomly assigned to a standard diet (SD; n = 12) or Western diet (WD; n = 24) (TD.88137, Harlan Laboratories) consisting of 42.0% fat (61.8% saturated, 27.3% monounsaturated, 4.7% polyunsaturated), 42.7% carbohydrate (80% sucrose), and 15.2% protein calories for 7 mo. Body weight and food intake were recorded weekly. For the final 2 mo of the dietary intervention (i.e., during months 5–7 on diet), WD mice were randomized to receive either nonsupplemented drinking water (WD; n = 12) or drinking water supplemented with a broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail (WD + Abx; n = 12) containing 0.4 g/l ampicillin (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), 0.4 g/l neomycin sulfate (Cayman Chemical; no. 14287), 0.2 g/l vancomycin (Chem-Impex International, Wood Dale, IL; no. 00315), and 0.4 g/l metronidazole (no. 443–48–1; Research Products International, Mount Prospect, IL) as described previously (21, 53). To avoid taste aversion-related reductions in fluid intake and weight loss commonly observed with antibiotic administration in mice (55), 1–5% glucose was added to the drinking water for all mice as advised by IACUC procedures for water additives.

Arterial stiffness.

Aortic pulse-wave velocity (aPWV) was measured at 0, 3, 5, and 7 mo on diet. Mice were anesthetized using 2% isoflurane and oxygen at 2 l/min, placed supine on a heating board with legs secured to ECG electrodes, and maintained at a target heart rate of ~450 beats/min by adjusting isoflurane concentration. Doppler probes (20 MHz) (Mouse Doppler data acquisition system; Indus Instruments, Houston, TX) were placed on the transverse aortic arch and abdominal aorta, and the distance between the probes was determined simultaneously with precision calipers. Five consecutive 2-s recordings were obtained for each mouse and used to determine the time between the R-wave of the ECG and the foot of the Doppler signal for each probe site (Δtime). aPWV (in cm/s) was calculated as aPWV = (distance between the two probes)/(Δtimeabdominal − Δtimetransverse).

Animal termination and tissue collection.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by exsanguination via cardiac puncture. Blood was collected with an EDTA-coated syringe and immediately centrifuged at 1,000 relative centrifugal force (rcf) for 10 min at 4°C to obtain plasma. Second-order mesenteric arteries were excised in ice-cold physiological saline solution (PSS: 0.288 g NaH2PO4, 1.802 g glucose, 0.44 g sodium pyruvate, 20.0 g BSA, 21.48 g NaCl, 0.875 g KCl, 0.7195 g MgSO4·7H2O, 13.9 g MOPS sodium salt, and 0.185 g EDTA per liter solution at pH 7.4) and cannulated for vascular reactivity experiments (see below). The thoracic aorta was excised and cleaned of surrounding perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) on ice-cold PSS. A 1-mm segment of proximal aorta was frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) media, transverse (7 µm) sections were obtained using a Microm HM550 cryostat (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), and images were analyzed in CellSens imaging software (Olympus, Tokyo) for determination of morphological characteristics. The remainder of the aorta and PVAT were flash frozen and stored at −80°C for biochemical analyses. Cecum and adipose tissue (subcutaneous, epididymal, and mesenteric depots) were isolated and weighed.

Vascular reactivity.

Endothelial function was determined via pressure myography. Second-order mesenteric arteries were placed in pressure myograph chambers (DMT, Atlanta, GA) containing warm PSS, cannulated onto glass micropipettes, and secured with suture. Arteries were equilibrated for 1 h at 37°C and an intraluminal pressure of 50 mmHg. Arteries were constricted with increasing doses of phenylephrine (PE: 10−9 to 10−5 M) followed immediately by a dose-response with endothelium-dependent dilator acetylcholine (ACh: 10−9 to 10−4 M). Arteries were washed for 20 min and then incubated in the presence of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME, 0.1 mM, 30 min). With l-NAME present, a second dose-response to acetylcholine (ACh: 10−9 to 10−4 M) was performed following preconstriction to PE (10−5 M) to determine the relative contribution of nitric oxide (NO) to endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD). After another 20-min washout period, a dose-response to endothelium-independent dilator sodium nitroprusside (SNP: 10−10 to 10−4 M) was obtained after preconstriction to PE (10−5 M). Artery diameters were measured by MyoView software (DMT) and used to calculate percent dilation for each dose of ACh or SNP relative to the PE-induced preconstriction: percent dilation (%) = (increase in luminal diameter to ACh/SNP)/[maximum decrease in luminal diameter to PE (10−5 M) preconstriction] × 100. Area under the dose-response curve (AUC; trapezoid method) was also calculated for each response. l-NAME-inhibited dilation was calculated as the percent reduction in maximal EDD in the absence vs. presence of l-NAME in each artery: l-NAME-inhibited dilation (% reduction in max EDD) = Max EDDACh − EDDACh w/l-NAME.

Microbiota characterization.

Fecal material was collected at termination and DNA extracted using the PureLink Microbiome DNA Purification Kit (A29790, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative PCR was used to verify suppression of the microbiota in Abx-treated animals. Reactions were optimized for the 16s rRNA gene using universal bacterial primers (forward 5′-AAACTCAAAKGAATTGACGG-3′, reverse 5′-CTCACRRCACGAGCTGA-3′) (2). Cycling conditions using the Bio-Rad CFX96 thermal cycler were as follows: 95°C for 3 min and then 40 cycles of 95°C 15 s, 61°C 15 s, 72°C 10 s, 85°C 5 s followed by florescence detection.

Paired-end sequencing libraries were constructed by following the Illumina 16s protocol which includes amplification of the V3–V4 regions of the 16s rRNA gene, purification of amplicons using AmPure beads, ligation with Illumina adaptors and dual indexes, followed by another round of AmPure bead purification, quantification, denaturation and library pooling, and sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq. Paired fastq files were assembled and processed using the default myPhyloDB ver. 1.2.0 sequencing pipeline (45), which utilizes the mothur bioinformatics software for sequence processing (57). Briefly, sequences were screened (maxhomop = 0, maxambig = 1), chimeras removed, and classified to the K-mer based nearest neighbor (KNN) in the GreenGenes ver. 13_5 reference database. After processing was completed, data were normalized by rarefaction based on a minimum sample size of 165,872 reads. Five hundred independent normalization runs were conducted and the average abundance for all normalization runs was used in further analyses.

Circulating analytes.

Plasma levels of insulin, leptin, and inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) were determined using a multiplex assay (MADKMAG-71K, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Intra-assay variability (<5%) was within the normal limits reported by the manufacturer.

LPS-binding protein (LBP) and soluble cluster of differentiation (CD)14.

Because of well-established difficulties obtaining reliable circulating LPS levels, as well as limitations of commercially available chromogenic assays (4, 47), LPS signaling was determined by circulating levels of LBP and soluble CD14, two commonly used surrogates for LPS. Plasma LBP (ALX-850–304/1, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) and soluble CD14 (no. DC140, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were measured via ELISA per manufacturer’s instructions using 1:800 and 1:40 dilution of plasma, respectively.

Aortic and PVAT protein expression.

Aortas were homogenized using ZrO beads and a bullet blender (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY) in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Fifteen micrograms of aorta protein lysate was loaded on 4–12% gradient gels, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred to PVDF membranes for Western blot analysis. Blots were blocked with Odyssey Blocking Buffer TBS (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against phospho-NF-kB p65 [1:500, no. 3033, Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Danvers, MA] and NF-kB p65 (1:500, no. 8242, CST). Perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) was homogenized using the Minute Total Protein Extraction Kit for Adipose Tissues/Cultured Adipocytes (Invent Biotechnologies, Plymouth, MN). As above, 30 µg of PVAT protein lysate was loaded for Western blot analysis with primary antibodies against p67 (phox) (1:500, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4, 1:1,000, ab133303, abcam, Cambridge, MA) and advanced glycation end products (AGEs, 1:1,000, ab23722, abcam). Target proteins were detected using IRDye 680RD (1:15,000, LI-COR), IRDye 800CW (1:15,000, LI-COR), or IgG-HRP (1:5,000, sc-2004, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) secondary antibodies and images were captured on Odyssey CLx (LI-COR) or EpiChemi3 (UVP, Upland, CA) imaging systems, respectively. Expression of each target protein was normalized to GAPDH (1:1,000, no. 2118, CST), the ratio of phosphorylated/total protein calculated for each sample, and data are presented as fold change relative to SD.

Glucose tolerance test.

At month 5 on diet and 1 wk before experiment termination, mice were fasted for 6 h and blood glucose was determined from tail-vein blood using AlphaTRAK 2 glucose meters (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 2 g/kg dextrose, and blood glucose was assessed at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min postinjection.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (SPSS for Windows, release 11.5.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). A mixed-model ANOVA (within factor, time or dose; between factor, treatment group) was used for aPWV and EDD and EID dose-response curves. When a significant main effect was observed, Tukey’s post hoc test was performed to determine specific pairwise differences. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlation analysis between outcome measures was performed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA).

Differential abundance of bacterial species was determined using the DESeq2 package in R and a False Discovery Rate of 0.05. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to visualize separation of microbial communities between treatment groups. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA; significant, P = 0.01) was used to determine differences in species abundance at the phyla level. Linear regression using Pearson’s correlation and sparse Partial Least Square Regression analysis (sPLS) were used to identify relationships between specific bacterial taxa and metavariables related to inflammation and vascular function outcomes.

RESULTS

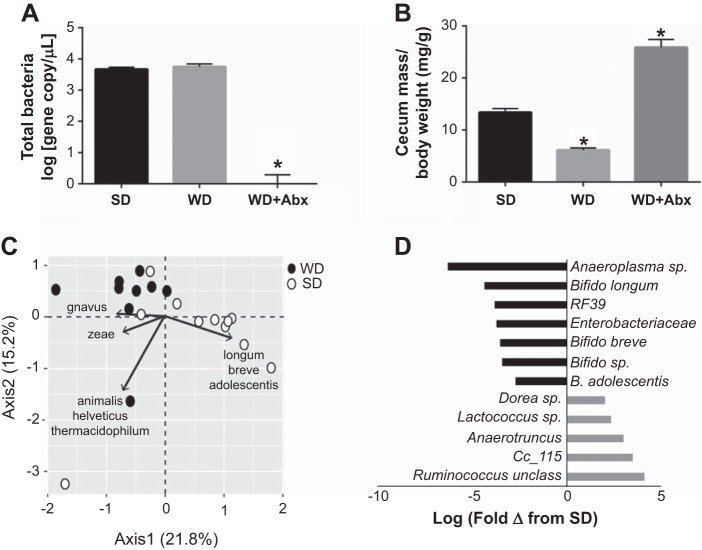

We first confirmed that antibiotic administration successfully abrogated intestinal microbes by qPCR using universal primers for the 16s ribosomal subunit. Bacterial count was similar between SD and WD mice, and significantly reduced with antibiotic treatment (WD + Abx) to levels observed in no template controls, confirming highly effective bacterial suppression (Fig. 1A). Cecal mass was significantly reduced in WD and increased in WD + Abx (Fig. 1B), as previously reported following high-fat feeding (71) and antibiotic treatment (22, 43, 48, 55, 56), respectively. In light of the marked microbial suppression with antibiotics, subsequent sequencing was not performed in antibiotic-treated mice.

Fig. 1.

Antibiotic treatment suppresses the gut microbiota following Western diet-induced dysbiosis. A: changes in total bacteria count following standard diet (SD), Western diet (WD), and WD with antibiotic (Abx) treatment. B: cecal mass following WD and antibiotic treatment. C: principal component analysis (PCA) biplot of mouse fecal microbial communities colored by diet (closed circles = WD; open circles = SD) and indicating bacterial species driving variability in each quadrant. D: histogram of significantly differentially abundant bacterial taxa in WD relative to SD (q = 0.05) represented as log fold-change. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 10–12/group. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups.

Western diet resulted in marked alterations in the gut microbiota. For example, relative to SD, animals on a WD displayed significantly increased Firmicutes (SD = 49,755; WD = 109,454; P = 0.0002), and decreased Bacteroidetes (SD = 21,907; WD = 11,205; P = 0.016) and Actinobacteria (SD = 94.082; WD = 45,210; P = 0.003). PCA analysis showed sample clustering by diet type along PC1, with separation driven by Ruminococcus gnavus for WD and several Bifidobacterium spp. for SD (Fig. 1C). Abundance of numerous bacterial taxa were altered by diet; in particular, Bifidobacterium spp. were significantly more abundant in SD animals compared with WD (Fig. 1D).

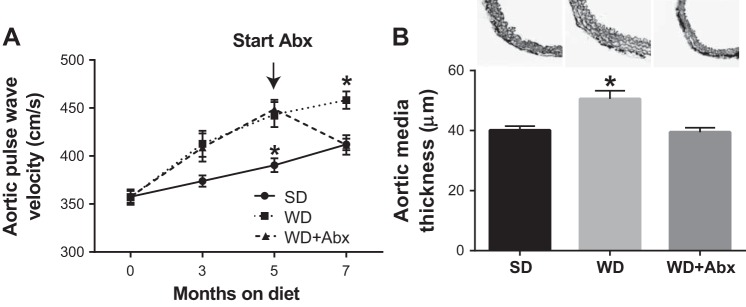

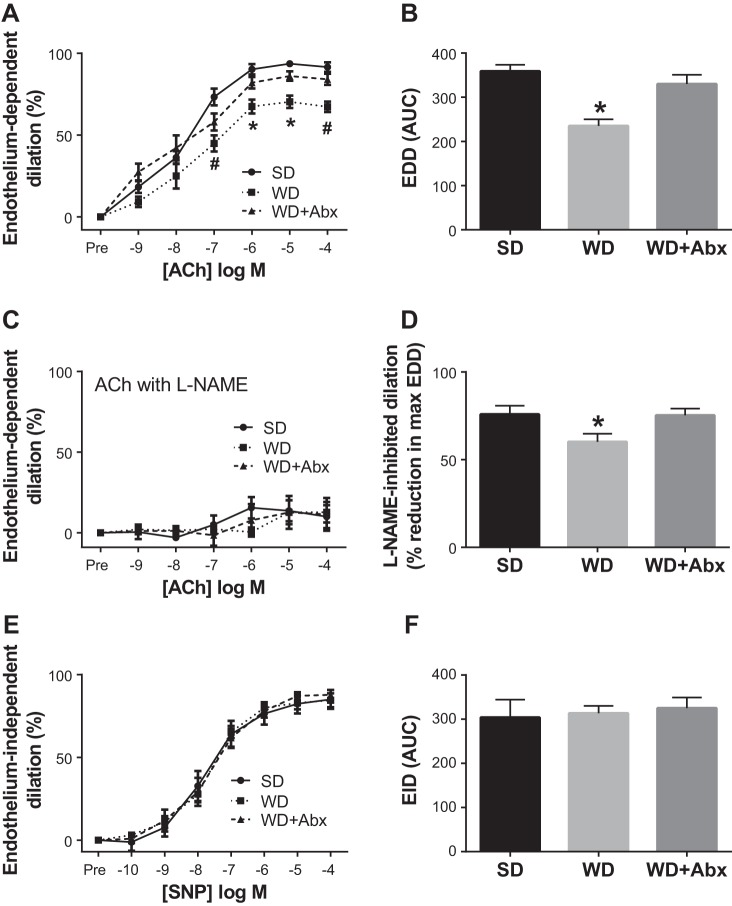

Arterial stiffness progressively increased in WD mice during the 7-mo intervention. In WD-fed mice that received antibiotic treatment (WD + Abx), arterial stiffness was completely normalized to SD levels (Fig. 2A). Likewise, aortic media thickness was increased in WD compared with SD mice, and normalized in WD + Abx (Fig. 2B). No group differences were observed for passive luminal diameter (SD 161.7 ± 7.4, WD 170.8 ± 6.7, WD + Abx 174.9 ± 8.5 µm) or phenylephrine-induced preconstriction (SD 56.6 ± 5.5, WD 59.0 ± 4.3, WD + Abx 59.9 ± 4.4%) in isolated mesenteric arteries. Similar to arterial stiffness, endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD) was significantly impaired in WD mice, and antibiotic treatment reversed this dysfunction (Fig. 3, A and B). Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase with l-NAME reduced EDD in all groups such that maximal acetylcholine-mediated dilation was similar in all groups (Fig. 3C). l-NAME-inhibited dilation was reduced in WD mice, and restored with antibiotic treatment (Fig. 3D). Endothelium-independent dilation was not altered by diet or antibiotic treatment (Fig. 3, E and F).

Fig. 2.

Antibiotics reverse Western diet-induced arterial stiffness. A: arterial stiffness was serially measured by in vivo aortic pulse wave velocity (aPWV). Antibiotic treatment in a subset of WD mice was initiated following 5 mo of WD feeding as indicated. B: media thickness was determined in segments of proximal thoracic aorta. Statistical analysis was performed using repeated-measures ANOVA (aPWV) and one-way ANOVA (media thickness) with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM; n = 10–12/group. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups.

Fig. 3.

Antibiotics reverse Western diet-induced endothelial dysfunction and restore l-NAME-inhibited dilation. Endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD) to acetylcholine (ACh) alone (A and B) and in the presence of nitric oxide synthase inhibitor l-NAME (C) was determined in mesenteric arteries. D: l-NAME-inhibited dilation, a measure of NO-dependent dilation, was calculated as the percent reduction in maximal EDD in the absence vs. presence of l-NAME. E and F: endothelium-dependent dilation (EID) to sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Statistical analysis was performed using a repeated-measures ANOVA (EDD and EID dose responses) and one-way ANOVA (all other outcomes). When a significant main effect was observed, Tukey’s post hoc test was performed to determine specific pairwise differences. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 8–12/group. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups; #P < 0.05 vs. SD.

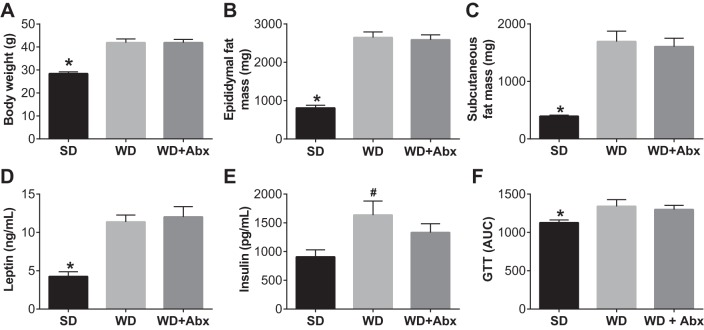

Body weight as well as epididymal and subcutaneous fat masses were significantly increased by WD, and unaffected by antibiotic treatment (Fig. 4, A–C). Plasma leptin and insulin levels were also elevated in WD and not significantly decreased by antibiotic treatment (Fig. 4, D and E). Likewise, WD significantly impaired glucose tolerance, with no effect of antibiotic treatment (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Antibiotic treatment does not alter body composition or glucose tolerance. Body weight (A), epididymal fat mass (B), and subcutaneous fat mass (C) following WD feeding and antibiotic treatment. Plasma leptin (D) and insulin (E) were determined via multiplex ELISA. F: area under the curve (AUC) for ip glucose tolerance test (GTT). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 10–12/group. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups. #P < 0.05 vs. SD.

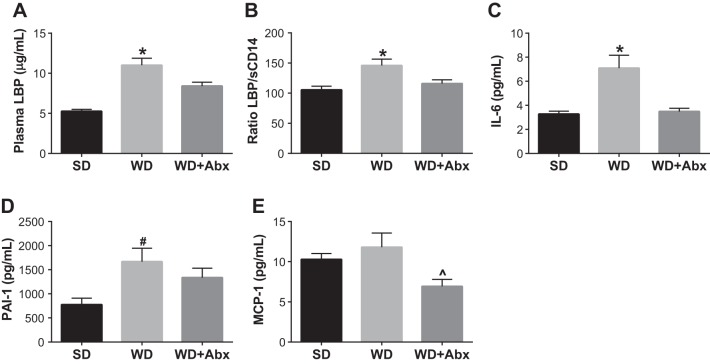

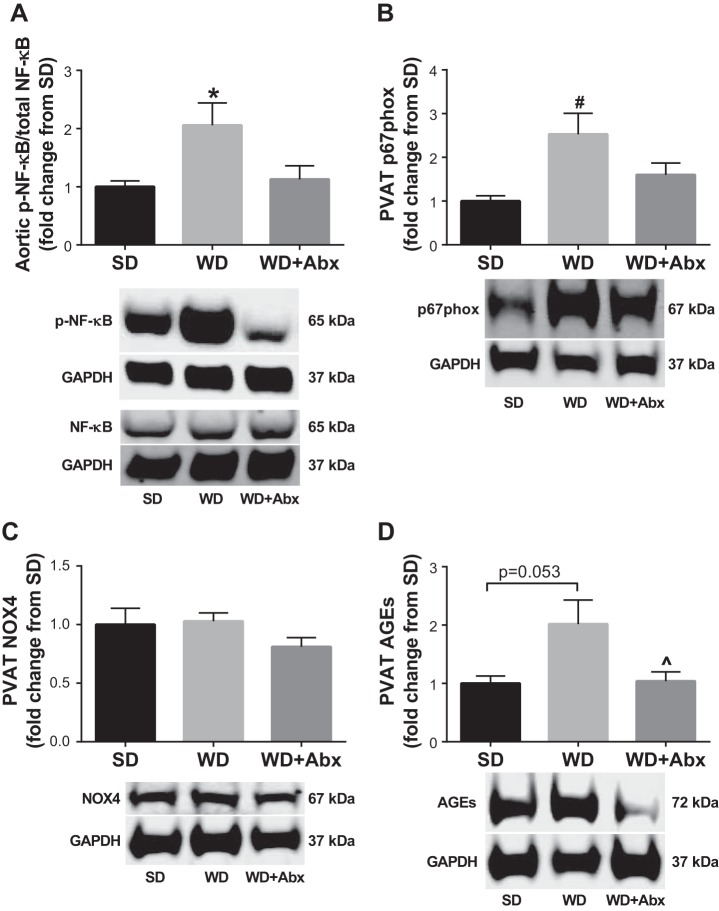

To begin to explore potential mechanisms by which suppression of gut dysbiosis reversed vascular dysfunction, we assessed plasma levels of LPS-binding protein (LBP) and soluble cluster of differentiation-14 (sCD14), two markers of LPS signaling associated with cardiovascular outcomes (35). LBP (Fig. 5A) and the LBP:sCD-14 ratio (Fig. 5B) were increased in WD, and significantly reduced in WD + Abx. In light of these data, we next measured plasma levels of several proinflammatory mediators induced by LPS. IL-6 and PAI-1 were significantly increased in WD, but not WD + Abx; whereas MCP-1 was significantly decreased in WD + Abx (Fig. 5, C–E). To further examine potential mechanisms contributing to vascular dysfunction, we examined protein expression in the aorta and surrounding PVAT. Phosphorylation of NF-κB, which also occurs downstream of LPS signaling, was significantly increased in the aorta of WD mice, and normalized following antibiotic treatment (Fig. 6A). PVAT expression of the p67phox, a regulatory subunit of NADPH oxidase (NOX) 2, was increased in WD, but not WD + Abx, compared with control-fed mice (Fig. 6B). In contrast, PVAT NOX4 expression was not different between groups (Fig. 6C). Last, PVAT AGEs tended to be higher in WD (P = 0.053 vs. SD), and were significantly decreased in WD + Abx compared with WD (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 5.

Antibiotic treatment attenuates Western diet-induced increases in circulating markers of endotoxemia and inflammation. Circulating LBP (A), LBP/sCD14 (B), IL-6 (C), PAI-1 (D), and MCP-1 (E) were determined in plasma via ELISA. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 5–12/group. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups, #P < 0.05 vs. SD, ^P < 0.05 vs. WD.

Fig. 6.

Antibiotic treatment attenuates Western diet-induced increases in proteins related to inflammation and oxidative stress. A: the ratio of phosphorylated to total NF-κB was determined in aorta via Western blotting. Abundance of NADPH oxidase (NOX) 2 subunit p67phox (B), NOX4 (C), and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (D) were determined in perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) via Western blotting. GAPDH expression was used to account for protein loading differences. Representative blots are shown below each graph. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 7–12/group. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups, #P < 0.05 vs. SD, ^P < 0.05 vs. WD.

Finally, we ran several correlation analyses to provide insight into the relations among alterations in bacterial species, inflammation, and vascular function. Several bacterial species were related to primary outcomes; in particular, three strains of Bifidobacteria were inversely correlated with body weight, LBP, and vascular function (see Supplemental Fig. 1A, available with the online version of this article, and Table 1). Furthermore, LBP was significantly correlated with both indexes of vascular function, l-NAME-inhibited dilation, and both systemic and vascular inflammation (Supplemental Fig. 1, B–E). Collectively, these results lend support for a sequence of events wherein WD-induced reductions in Bifidobacteria increase LPS translocation and systemic signaling, which in turn propagates an inflammatory response that drives vascular dysfunction.

Table 1.

Correlations between bacterial abundances and physiological outcomes in standard and Western diet-fed mice

| Allo- | Lacto- | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. breve | B. longum | B.adolescentis | baculum | coccus | Dorea | |

| EDD | r = 0.55* | r = 0.49* | r = 0.52* | r = −0.62* | r = −0.49* | r = −0.66* |

| aPWV | r = −0.42 | r = −0.6* | r = −0.63* | r = 0.43* | r = 0.27 | r = 0.51* |

| LBP | r = −0.50* | r = −0.57* | r = −051* | r = 0.61* | r = 0.61* | r = 0.7* |

| BW | r = −0.55* | r = −0.58* | r = −0.51* | r = 0.66* | r = 0.60* | r = 0.69* |

Mixed data from standard diet (SD) and Western diet (WD) groups were used for correlations. B., Bifidobacterium; EDD, endothelium-dependent dilation; aPWV, aortic pulse-wave velocity; LBP, LPS binding protein; BW, body weight. n = 9–12/group.

P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The primary finding of the current study is that suppression of the microbiota via a broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail reversed Western diet-induced arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction. These vascular improvements were independent of changes in BW, fat mass, and glucose tolerance and were accompanied by reductions in LBP, markers of inflammation, and restoration of l-NAME-inhibited dilation. Last, the diet-induced vascular dysfunction correlated with reductions in several bacterial taxa, most notably several species of Bifidobacterium. Collectively, these results indicate that gut dysbiosis may be a causal factor in the development of vascular dysfunction, and suggest a potential role for bacterial-derived LPS in mediating these events. These results extend recent data linking gut dysbiosis to the development of other cardiovascular abnormalities, including atherosclerosis and hypertension (60), and lend further support to the notion that the gut microbiota represent a future therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease (30).

In the first study to examine a link between vascular function and gut dysbiosis, Vikram et al. (63) elegantly demonstrated, using microbiota transplantations and antibiotic treatment, that gut dysbiosis can induce endothelial function via upregulation of vascular miR-204 and subsequent downregulation of Sirt1. The results of the present study complement and extend the findings by Vikram et al. (63) in several ways. First, in addition to its effects on endothelial function, we found that suppression of the gut microbiota reversed WD-induced arterial stiffness, another clinically relevant feature of vascular function. Second, profiling of bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA revealed substantial dysbiosis in Western diet-fed mice, and identified changes in individual bacteria (e.g., reductions in Bifidobacterium) that are correlated with, and may drive, the observed vascular dysfunction. Third, Vikram et al. described a gut-vascular axis driven by increases in miR-204 and subsequent reductions in Sirt1, and the authors note that they were unable to identify a circulating factor that governs crosstalk within this axis. Our data suggest that LPS signaling may represent one such circulating messenger. Indeed, LPS has been shown to increase miR-204; LPS and miR-204 have each been shown to decrease Sirt1 (27, 67), and Li et al. (42) demonstrated that this miR-204-Sirt1 axis is a critical mediator of LPS-induced inflammation. Thus, taken together, the two studies suggest that gut dysbiosis enhances LPS signaling in the general circulation, which in turn may impair vascular function via the miR-204-Sirt1 axis.

Chronic low-grade inflammation is a major factor contributing to the development of obesity-related vascular dysfunction (24). Increased circulating and adipose tissue cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), can induce vascular inflammatory signaling and oxidative stress, two key processes involved in the development of vascular dysfunction (3, 15). An emerging hypothesis for the origin of obesity-related inflammation is an elevation in circulating bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS or endotoxin). Indeed, a two- to threefold increase in circulating LPS, termed “metabolic endotoxemia,” has been observed in genetic obese (ob/ob) and high-fat diet (HFD) fed mice (7, 8). Once in circulation, LPS elicits a potent inflammatory response at both systemic and local levels (7). To begin to explore putative mechanisms linking the gut dysbiosis to vascular dysfunction in the present study, we measured circulating levels of LBP and sCD14, two established surrogate measures of LPS independently associated with cardiovascular dysfunction (35). Although LBP and sCD14 expression are both stimulated by LPS, sCD14 is reported to have suppressing effects on endotoxin. In support of this notion, increased sCD14 has been associated with lower levels of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 in both plasma and adipose tissue despite higher plasma endotoxemia (36). Thus an elevated LBP:sCD14 in plasma may be used as a surrogate marker of endotoxemia. In line with this, LBP and LBP:sCD14 ratio was significantly increased in mice fed a Western diet and reduced following antibiotic treatment. These results are in agreement with Li et al. (41), who reported that enhanced LPS translocation subsequent to gut dysbiosis mediated atherogenesis in apoE−/− mice fed a Western diet.

Mechanistically, LPS can activate Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a key mediator of innate immunity, to promote inflammation within the vasculature and systemically (29, 44). Downstream of TLR4, the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) can promote vascular inflammation through upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and pro-oxidant enzymes such as NADPH oxidase (5). We found that antibiotic treatment reduced circulating levels of IL-6 and MCP-1, and vascular phosphorylation of NF-κB, all of which are regulated by LPS and are established mediators of vascular dysfunction (59). In addition, NF-κB activation can suppress the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), a key enzyme that regulates vascular homeostasis through the production of the vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory molecule nitric oxide (NO) (38). Although eNOS expression or phosphorylation was not directly measured in the current study, our finding that dilation following l-NAME inhibition, a measure of NO-dependent dilation, was reduced by WD feeding and restored with antibiotic treatment suggests that altered NO bioavailability may have contributed to the observed differences in vascular function. However, it should be noted that l-NAME-inhibited dilation is not equivalent to NO bioavailability and l-NAME may affect the oxidative status in the vasculature independent of its effects on NO. Thus future studies are needed to more comprehensively determine the role of NO in mediating vascular alterations in the setting of gut dysbiosis.

A growing body of evidence suggests that changes to the perivascular adipose tissue can strongly influence vascular structure and function (23, 28, 49, 64). For example, studies by Fleenor and colleagues (17, 50) have found that accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in aortic PVAT contributes to arterial stiffening with aging. In the present study, we found that PVAT accumulation of AGEs tended to be higher in WD-fed mice (P = 0.053) compared with control mice, and were significantly reduced with antibiotic treatment. Importantly, AGEs can increase oxidative stress, at least in part through activation of the pro-oxidant NADPH oxidase enzymes (20, 66). In line with this, we observed that WD-fed mice, but not antibiotic-treated mice, displayed increased PVAT expression of the NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) subunit p67phox. As previously observed, an increased expression of NOX2 and p67phox within PVAT may contribute to oxidative stress in obese mice (28, 69). Because NOX2 activity is influenced by multiple regulatory subunits (58), additional studies are needed to confirm whether these observed effects on p67phox protein expression are directly related to a rise in oxidative stress in the vasculature and PVAT. Interestingly, we found that PVAT expression of constitutively active NOX4 was not altered by WD feeding or antibiotic treatment. Together, these data suggest that dysbiosis is associated with increased NOX2, but not NOX4, within the PVAT. Western diet feeding also induced aortic remodeling, as evidenced by an increase in aortic media thickness, which was abrogated by antibiotic treatment. These data are the first to confirm that alterations in the gut microbiota can influence PVAT, and collectively suggest a sequence of events whereby a Western diet induces gut dysbiosis and LPS translocation to the general circulation, eliciting an inflammatory response in the vasculature and PVAT that ultimately results in arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction. In a recent review, Xia and Li (70) described the “obesity triad” wherein inflammation, hypoxia, and oxidative stress initiate a deleterious cycle within the PVAT that culminates in the development of vascular dysfunction. Although LPS signaling was not an element of the signaling cascade originally described by the authors, and PVAT inflammation does not require a hypothetical transfer of circulating or endothelial material, it is possible that LPS signaling may exacerbate the obesity triad and facilitate vascular dysfunction. Future studies utilizing genetic ablation of LPS signaling (e.g., CD14) and downstream mediators (e.g., IL-6, NF-κB, NADPH oxidase) are necessary to more definitively test this hypothesis and determine the specific signaling cascades involved.

Rodent models of Western diet-induced obesity display similar phylum-level changes to their microbial composition as those observed in obese individuals, including an increased Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes ratio (40, 62), and these changes have been associated with metabolic perturbations (8). Suppression of the gut microbiota with antibiotics has been used in numerous animal models to establish a causal role of the gut microbiota in disease risk or progression (11, 37, 52, 61). For example, antibiotics were used to establish an obligate role of the gut microbiota in the production of the proatherogenic compound trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) (65).

Although antibiotics have been widely used as an experimental tool to examine the effects of microbiota suppression on host physiology, the approach is not without limitations. First, although the antibiotics used in the current study successfully eliminated the gut bacteria and are poorly absorbed (33, 34, 54), we cannot say with absolute certainty that their actions were exclusively localized to the intestine and without systemic effects. Second, the broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail used in the current study suppresses all gut bacteria, even those which have been shown to positively modulate cardiovascular function, such as Akkermansia muciniphila (41). Thus this approach precludes us from determining the specific microbial alterations that mediate the observed vascular protection. However, some insight was gained regarding the bacterial changes that mediate Western diet-induced vascular dysfunction. We observed significant decreases in several Bifidobacterium spp. following WD that correlated with both vascular dysfunction and inflammatory parameters. These results are in agreement with those from Cani et al. (9), who reported that enhancing Bifidobacterium populations improved glucose tolerance and reduced inflammation in diet-induced diabetic mice. More recently, a study by Catry et al. (12) reversed endothelial dysfunction in apoE−/− mice fed an n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid-depleted diet through supplementation of inulin-type fructans (ITFs). Of note, the improvement in endothelial function with ITF-supplementation was accompanied by a dramatic increase in abundance of cecal Bifidobacterium.

We acknowledge that the lack of an additional control group fed a standard diet (SD) and receiving antibiotics is a significant limitation of the present study. Previous research has not observed an effect of antibiotic treatment in control low-fat diet-fed mice on markers of endotoxemia or metabolic parameters (8, 11). Given that SD-fed mice displayed normal vascular function, we did not anticipate that inclusion of a SD + Abx group would provide any significant insight regarding the role of gut dysbiosis in mediating vascular dysfunction. However, we did observe a slight age-related increase in aPWV in our SD group. Thus, if this increase was related to changes in microbial composition, then antibiotic treatment may have attenuated this increase. Regardless of this limitation, our results demonstrate that Western diet-induced dysbiosis represents an important factor in the development of vascular dysfunction.

In conclusion, the present work corroborates previous research linking gut dysbiosis to endothelial dysfunction and is the first to demonstrate that suppression of gut dysbiosis reverses Western diet-induced arterial stiffness. The data also provide mechanistic insight into the downstream mediators of this dysfunction and lend further support for the development of microbiota-targeted therapies in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease.

GRANTS

This study was supported by Boettcher Foundation’s Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Program (C. L. Gentile).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.L.B., T.L.W., and C.L.G. conceived and designed research; M.L.B., D.M.L., D.K.J., S.H., K.E.E., and C.L.G. performed experiments; M.L.B., D.M.L., D.K.J., S.H., K.E.E., T.L.W., and C.L.G. analyzed data; M.L.B., D.M.L., T.L.W., and C.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; M.L.B., D.M.L., T.L.W., and C.L.G. prepared figures; M.L.B. and C.L.G. drafted manuscript; M.L.B., D.M.L., T.L.W., and C.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; M.L.B., D.M.L., D.K.J., S.H., K.E.E., T.L.W., and C.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adnan S, Nelson JW, Ajami NJ, Venna VR, Petrosino JF, Bryan RM Jr, Durgan DJ. Alterations in the gut microbiota can elicit hypertension in rats. Physiol Genomics 49: 96–104, 2017. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00081.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacchetti De Gregoris T, Aldred N, Clare AS, Burgess JG. Improvement of phylum- and class-specific primers for real-time PCR quantification of bacterial taxa. J Microbiol Methods 86: 351–356, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belin de Chantemele EJ, Stepp DW. Influence of obesity and metabolic dysfunction on the endothelial control in the coronary circulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52: 840–847, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutagy NE, McMillan RP, Frisard MI, Hulver MW. Metabolic endotoxemia with obesity: Is it real and is it relevant? Biochimie 124: 11–20, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasier AR. The nuclear factor-kappaB-interleukin-6 signalling pathway mediating vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc Res 86: 211–218, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JM, Hazen SL. The gut microbial endocrine organ: bacterially derived signals driving cardiometabolic diseases. Annu Rev Med 66: 343–359, 2015. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, Waget A, Delmée E, Cousin B, Sulpice T, Chamontin B, Ferrières J, Tanti JF, Gibson GR, Casteilla L, Delzenne NM, Alessi MC, Burcelin R. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 56: 1761–1772, 2007. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57: 1470–1481, 2008. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Knauf C, Burcelin RG, Tuohy KM, Gibson GR, Delzenne NM. Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia 50: 2374–2383, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cani PD, Osto M, Geurts L, Everard A. Involvement of gut microbiota in the development of low-grade inflammation and type 2 diabetes associated with obesity. Gut Microbes 3: 279–288, 2012. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvalho BM, Guadagnini D, Tsukumo DML, Schenka AA, Latuf-Filho P, Vassallo J, Dias JC, Kubota LT, Carvalheira JBC, Saad MJA. Modulation of gut microbiota by antibiotics improves insulin signalling in high-fat fed mice. Diabetologia 55: 2823–2834, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2648-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catry E, Bindels LB, Tailleux A, Lestavel S, Neyrinck AM, Goossens JF, Lobysheva I, Plovier H, Essaghir A, Demoulin JB, Bouzin C, Pachikian BD, Cani PD, Staels B, Dessy C, Delzenne NM. Targeting the gut microbiota with inulin-type fructans: preclinical demonstration of a novel approach in the management of endothelial dysfunction. Gut 67: 271–283, 2018. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruickshank K, Riste L, Anderson SG, Wright JS, Dunn G, Gosling RG. Aortic pulse-wave velocity and its relationship to mortality in diabetes and glucose intolerance: an integrated index of vascular function? Circulation 106: 2085–2090, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000033824.02722.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donato AJ, Henson GD, Morgan RG, Enz RA, Walker AE, Lesniewski LA. TNF-α impairs endothelial function in adipose tissue resistance arteries of mice with diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H672–H679, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00271.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du B, Ouyang A, Eng JS, Fleenor BS. Aortic perivascular adipose-derived interleukin-6 contributes to arterial stiffness in low-density lipoprotein receptor deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H1382–H1390, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00712.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durgan DJ, Ganesh BP, Cope JL, Ajami NJ, Phillips SC, Petrosino JF, Hollister EB, Bryan RM Jr. Role of the gut microbiome in obstructive sleep apnea-induced hypertension. Hypertension 67: 469–474, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleenor BS, Eng JS, Sindler AL, Pham BT, Kloor JD, Seals DR. Superoxide signaling in perivascular adipose tissue promotes age-related artery stiffness. Aging Cell 13: 576–578, 2014. doi: 10.1111/acel.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fry JL, Al Sayah L, Weisbrod RM, Van Roy I, Weng X, Cohen RA, Bachschmid MM, Seta F. Vascular Smooth Muscle Sirtuin-1 Protects Against Diet-Induced Aortic Stiffness. Hypertension 68: 775–784, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galili O, Versari D, Sattler KJ, Olson ML, Mannheim D, McConnell JP, Chade AR, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Early experimental obesity is associated with coronary endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H904–H911, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00628.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, Creager MA. Advanced glycation end products: sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 114: 597–605, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gregory JC, Buffa JA, Org E, Wang Z, Levison BS, Zhu W, Wagner MA, Bennett BJ, Li L, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Transmission of atherosclerosis susceptibility with gut microbial transplantation. J Biol Chem 290: 5647–5660, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.618249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafsson BE, Maunsbach AB. Ultrastructure of the enlargec cecum in germfree rats. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat 120: 555–578, 1971. doi: 10.1007/BF00340589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Cao ZF, Stoffel E, Cohen P. Role of perivascular adipose tissue in vascular physiology and pathology. Hypertension 69: 770–777, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iantorno M, Campia U, Di Daniele N, Nistico S, Forleo GB, Cardillo C, Tesauro M. Obesity, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 28: 169–176, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karbach SH, Schönfelder T, Brandão I, Wilms E, Hörmann N, Jäckel S, Schüler R, Finger S, Knorr M, Lagrange J, Brandt M, Waisman A, Kossmann S, Schäfer K, Münzel T, Reinhardt C, Wenzel P. Gut microbiota promote angiotensin ii-induced arterial hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc 5: e003698, 2016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karlsson F, Tremaroli V, Nielsen J, Bäckhed F. Assessing the human gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Diabetes 62: 3341–3349, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db13-0844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kassan M, Vikram A, Li Q, Kim YR, Kumar S, Gabani M, Liu J, Jacobs JS, Irani K. MicroRNA-204 promotes vascular endoplasmic reticulum stress and endothelial dysfunction by targeting Sirtuin1. Sci Rep 7: 9308, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06721-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ketonen J, Shi J, Martonen E, Mervaala E. Periadventitial adipose tissue promotes endothelial dysfunction via oxidative stress in diet-induced obese C57Bl/6 mice. Circ J 74: 1479–1487, 2010. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim F, Pham M, Luttrell I, Bannerman DD, Tupper J, Thaler J, Hawn TR, Raines EW, Schwartz MW. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates vascular inflammation and insulin resistance in diet-induced obesity. Circ Res 100: 1589–1596, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.142851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinlay S, Michel T, Leopold JA. The future of vascular biology and medicine. Circulation 133: 2603–2609, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayasi R, Akamine EH, Davel AP, Rodrigues MA, Carvalho CR, Rossoni LV. Oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators contribute to endothelial dysfunction in high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. J Hypertens 28: 2111–2119, 2010. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833ca68c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, DiDonato JA, Chen J, Li H, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Warrier M, Brown JM, Krauss RM, Tang WH, Bushman FD, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of l-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med 19: 576–585, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konishi T, Idezuki Y, Kobayashi H, Shimada K, Iwai S, Yamaguchi K, Shinagawa N. Oral vancomycin hydrochloride therapy for postoperative methicillin-cephem-resistant Staphylococcus aureus enteritis. Surg Today 27: 826–832, 1997. doi: 10.1007/BF02385273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunin CM, Chalmers TC, Leevy CM, Sebastyen SC, Lieber CS, Finland M. Absorption of orally administered neomycin and kanamycin with special reference to patients with severe hepatic and renal disease. N Engl J Med 262: 380–385, 1960. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196002252620802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laugerette F, Alligier M, Bastard JP, Drai J, Chanséaume E, Lambert-Porcheron S, Laville M, Morio B, Vidal H, Michalski MC. Overfeeding increases postprandial endotoxemia in men: Inflammatory outcome may depend on LPS transporters LBP and sCD14. Mol Nutr Food Res 58: 1513–1518, 2014. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laugerette F, Furet JP, Debard C, Daira P, Loizon E, Géloën A, Soulage CO, Simonet C, Lefils-Lacourtablaise J, Bernoud-Hubac N, Bodennec J, Peretti N, Vidal H, Michalski MC. Oil composition of high-fat diet affects metabolic inflammation differently in connection with endotoxin receptors in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302: E374–E386, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00314.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laukens D, Brinkman BM, Raes J, De Vos M, Vandenabeele P. Heterogeneity of the gut microbiome in mice: guidelines for optimizing experimental design. FEMS Microbiol Rev 40: 117–132, 2016. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee KS, Kim J, Kwak SN, Lee KS, Lee DK, Ha KS, Won MH, Jeoung D, Lee H, Kwon YG, Kim YM. Functional role of NF-κB in expression of human endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 448: 101–107, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lesniewski LA, Durrant JR, Connell ML, Folian BJ, Donato AJ, Seals DR. Salicylate treatment improves age-associated vascular endothelial dysfunction: potential role of nuclear factor kappaB and forkhead Box O phosphorylation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66: 409–418, 2011. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ley RE, Bäckhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11070–11075, 2005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J, Lin S, Vanhoutte PM, Woo CW, Xu A. Akkermansia muciniphila protects against atherosclerosis by preventing metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in Apoe−/− mice. Circulation 133: 2434–2446, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, Sun Q, Li Y, Yang Y, Yang Y, Chang T, Man M, Zheng L. Overexpression of SIRT1 induced by resveratrol and inhibitor of miR-204 suppresses activation and proliferation of microglia. J Mol Neurosci 56: 858–867, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li M, Liang P, Li Z, Wang Y, Zhang G, Gao H, Wen S, Tang L. Fecal microbiota transplantation and bacterial consortium transplantation have comparable effects on the re-establishment of mucosal barrier function in mice with intestinal dysbiosis. Front Microbiol 6: 692, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang CF, Liu JT, Wang Y, Xu A, Vanhoutte PM. Toll-like receptor 4 mutation protects obese mice against endothelial dysfunction by decreasing NADPH oxidase isoforms 1 and 4. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 777–784, 2013. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.301087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manter DK, Korsa M, Tebbe C, Delgado JA. myPhyloDB: a local web server for the storage and analysis of metagenomic data. Database (Oxford) 2016: baw037, 2016. doi: 10.1093/database/baw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mell B, Jala VR, Mathew AV, Byun J, Waghulde H, Zhang Y, Haribabu B, Vijay-Kumar M, Pennathur S, Joe B. Evidence for a link between gut microbiota and hypertension in the Dahl rat. Physiol Genomics 47: 187–197, 2015. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00136.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munford RS. Endotoxemia-menace, marker, or mistake? J Leukoc Biol 100: 687–698, 2016. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3RU0316-151R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murakami M, Tognini P, Liu Y, Eckel-Mahan KL, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P. Gut microbiota directs PPARγ-driven reprogramming of the liver circadian clock by nutritional challenge. EMBO Rep 17: 1292–1303, 2016. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nosalski R, Guzik TJ. Perivascular adipose tissue inflammation in vascular disease. Br J Pharmacol 174: 3496–3513, 2017. doi: 10.1111/bph.13705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouyang A, Garner TB, Fleenor BS. Hesperidin reverses perivascular adipose-mediated aortic stiffness with aging. Exp Gerontol 97: 68–72, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pierce GL, Lesniewski LA, Lawson BR, Beske SD, Seals DR. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation contributes to vascular endothelial dysfunction via oxidative stress in overweight/obese middle-aged and older humans. Circulation 119: 1284–1292, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajpal DK, Klein JL, Mayhew D, Boucheron J, Spivak AT, Kumar V, Ingraham K, Paulik M, Chen L, Van Horn S, Thomas E, Sathe G, Livi GP, Holmes DJ, Brown JR. Selective spectrum antibiotic modulation of the gut microbiome in obesity and diabetes rodent models. PLoS One 10: e0145499, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 118: 229–241, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rao S, Kupfer Y, Pagala M, Chapnick E, Tessler S. Systemic absorption of oral vancomycin in patients with Clostridium difficile infection. Scand J Infect Dis 43: 386–388, 2011. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.544671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reikvam DH, Erofeev A, Sandvik A, Grcic V, Jahnsen FL, Gaustad P, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ, Meza-Zepeda LA, Johansen FE. Depletion of murine intestinal microbiota: effects on gut mucosa and epithelial gene expression. PLoS One 6: e17996, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Savage DC, Dubos R. Alterations in the mouse cecum and its flora produced by antibacterial drugs. J Exp Med 128: 97–110, 1968. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 7537–7541, 2009. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sirker A, Zhang M, Shah AM. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular disease: insights from in vivo models and clinical studies. Basic Res Cardiol 106: 735–747, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0190-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stoll LL, Denning GM, Weintraub NL. Endotoxin, TLR4 signaling and vascular inflammation: potential therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. Curr Pharm Des 12: 4229–4245, 2006. doi: 10.2174/138161206778743501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang WH, Kitai T, Hazen SL. Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Circ Res 120: 1183–1196, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang WH, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 368: 1575–1584, 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turnbaugh PJ, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 3: 213–223, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vikram A, Kim YR, Kumar S, Li Q, Kassan M, Jacobs JS, Irani K. Vascular microRNA-204 is remotely governed by the microbiome and impairs endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by downregulating Sirtuin1. Nat Commun 7: 12565, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Villacorta L, Chang L. The role of perivascular adipose tissue in vasoconstriction, arterial stiffness, and aneurysm. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 21: 137–147, 2015. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2014-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, Wu Y, Schauer P, Smith JD, Allayee H, Tang WH, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 472: 57–63, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wautier JL, Wautier MP. Blood cells and vascular cell interactions in diabetes. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 25: 49–53, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang W, Zhang Y, Guo X, Zeng Z, Wu J, Liu Y, He J, Wang R, Huang Q, Chen Z. Sirt1 protects endothelial cells against LPS-induced barrier dysfunction. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017: 4082102, 2017. doi: 10.1155/2017/4082102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Widlansky ME, Gokce N, Keaney JF Jr, Vita JA. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 42: 1149–1160, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00994-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xia N, Horke S, Habermeier A, Closs EI, Reifenberg G, Gericke A, Mikhed Y, Münzel T, Daiber A, Förstermann U, Li H. Uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in perivascular adipose tissue of diet-induced obese mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 36: 78–85, 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xia N, Li H. The role of perivascular adipose tissue in obesity-induced vascular dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol 174: 3425–3442, 2017. doi: 10.1111/bph.13650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang J, Bindels LB, Segura Munoz RR, Martínez I, Walter J, Ramer-Tait AE, Rose DJ. Disparate metabolic responses in mice fed a high-fat diet supplemented with maize-derived non-digestible feruloylated oligo- and polysaccharides are linked to changes in the gut microbiota. PLoS One 11: e0146144, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, Li E, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zadeh M, Gong M, Qi Y, Zubcevic J, Sahay B, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK, Mohamadzadeh M. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension 65: 1331–1340, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]