Abstract

Cancer models derived from patient specimens poorly reflect early-stage cancer development because cancer cells acquire numerous additional molecular alterations before the disease is clinically detectable. Earlier studies have used differentiated cells derived from induced pluripotent cancer cells (iPCCs) to partially mirror cancer disease phenotype, but the highly heterogeneous nature of cancer cells as well as difficulties with reprogramming cancer cells has limited the application of this technique. An alternative approach to modeling cancer in a dish entails reprogramming adult differentiated cells from patients with cancer syndromes to pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), followed by directed differentiation of those PSCs. A directed reprogramming and differentiation strategy has the potential to recapitulate cancer progression and capture the earliest molecular alterations that underlie cancer initiation. The reprogrammed cells share patient-specific genetic and epigenetic traits, offering a new platform to develop personalized therapy for cancer patients. In this review, we will provide an overview of available reprogramming methods of cancer cells and describe how cancer-derived stem cells have been used to characterize effects of defined molecular alterations in specific cell types. We also describe the “disease in a dish” model developed to study genetic cancer syndromes. These approaches highlight recent contributions of stem cell technology to the cancer biology realm.

Keywords: Disease model, induced pluripotent stem cells, induced pluripotent cancer cells, reprogramming

Introduction

In 2006, Drs. Takahashi and Yamanaka reported the first reprogramming of mature somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [1], a type of cell with the potential to generate all cell types of adult tissues, by transduction of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and MYC (OSKM, also known as the “Yamanaka four” factors). This opened a new avenue for studying a variety of human diseases, including in vitro disease modeling, organ regeneration, transplantation medicine, precision medicine, drug screening, fundamental cell fate selection as well as developmental research (Figure 1). In 2008, Dr. Daley’s lab first described a human genetic disease model constructed from patient-derived iPSCs [2]. Other “disease in a dish” models have been successfully set up for a number of genetic diseases, including disorders of neuronal, cardiac or hepatic development or function, by differentiating patient-derived iPSCs to tissue-specific lineages [3-8]. In cancer studies, scientists often utilize immortalized cell lines or cancerous lines derived from patient tumor specimens. These cell lines not only represent cancer phenotypes but also provide a vast record of genetic information associated with cancer development. The intrinsic differentiation potential of human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) or more restricted progenitor stem cells facilitates cancer research by permitting the study of the effect of well-defined mutations within the specific lineages/cell types that ultimately become cancers. However, since cancer cell lines are isolated from well-developed tumors, they commonly fail to mirror the dynamic genetic and epigenetic alterations involved in early cancer initiation and progression. In contrast, cell lines derived from (non-cancerous) biopsies from patients with a tendency to develop cancers or engineered from PSCs expressing particular oncogenes can be combined with differentiation protocols to characterize cancer development in those same lineages but prior to acquisition of late cancer mutations.

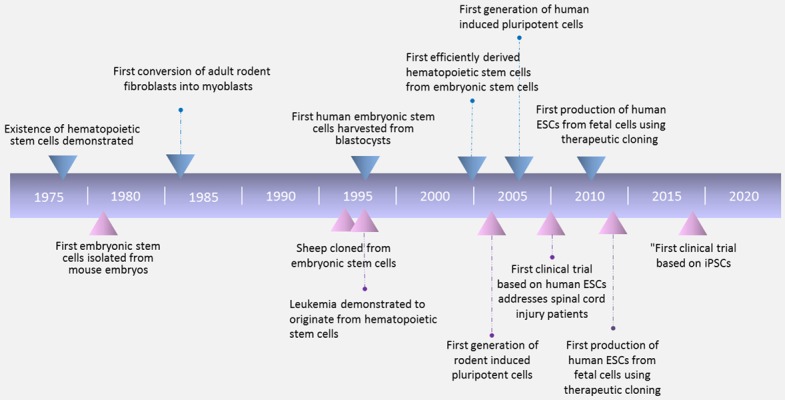

Figure 1.

Timeline of stem cell research milestones in the past 50 years.

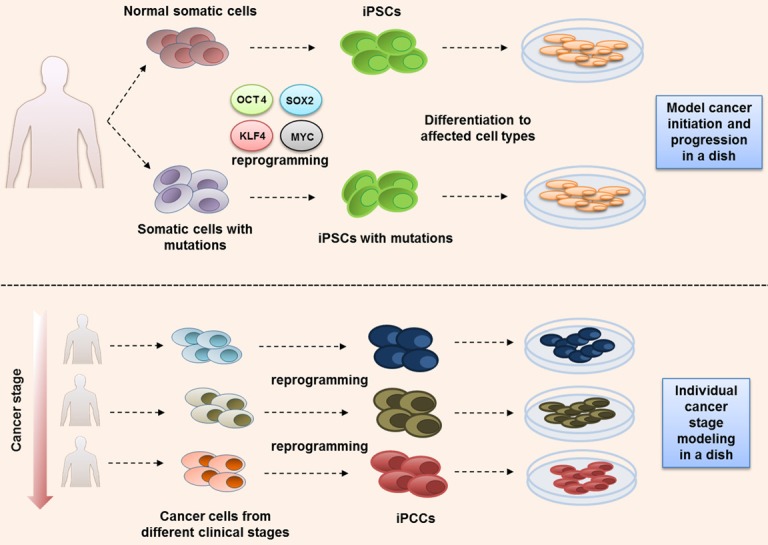

In this review, we summarize the most recent progress of cancer research using reprogrammed stem cells. We introduce the ways different types of cancer cells were reprogrammed and how their characteristics changed after reprogramming (Figure 2). We discuss the benefits and obstacles in applying induced pluripotent cancer cells (iPCCs) to both basic and pre-clinical research. We also describe the “disease in a dish” model in genetic cancer syndromes using patient-derived iPSCs and examples of cancer diseases that could be studied by this model system.

Figure 2.

Two major stem cell disease modeling strategies used in cancer research. Upper strategy: iPSCs are used to study cancer predisposition. Somatic cells carrying genetic alterations leading to a cancer predisposition are biopsied from a patient and paired with normal somatic cells from healthy family member controls. Both are reprogrammed to iPSCs using classic OSKM factors and then differentiated sequentially to cell lineage(s) of interest. The frequency and severity of disease phenotypes are compared at various iPSC differentiation stages with healthy iPSCs. Lower strategy: Generating iPCCs from patient tumor cells. Tumor cells from different stages of disease progression are reprogrammed and subsequently differentiated to a cancer-specific cell lineage. Differentiated cells from reset iPCCs will often mirror cancer disease phenotypes.

Cancer cell reprogramming

Inspired by discovery of reprogramming mature somatic cells to embryonic-like iPSCs by expressing appropriate transcriptional factor combinations [1,9,10], the “cancer cell reprogramming” concept was quickly extended to cancer research. The idea of reprogramming differentiated malignant cells to iPCCs offers a novel tool to investigate effects of the cancer cell genome in lineages not present within a biopsy, model disease progression, recapitulate specific cancer phenotypes in cell culture, and understand the dynamic oncogenic transforming process during tumorigenesis. In the past ten years, several labs have applied iPCCs to characterize tumorigenic properties of certain malignancies. Kim et al. reported that injection of a single iPCC derived from a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reprogrammed into immune-deficient mice led to a teratoma composed of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) precursors. In addition, the PanIN-like cells secreted proteins similar to those expressed in early-to-intermediate stage human pancreatic cancers, including those involved in the HNF4α transcription factor network. However, most iPCCs derived from reprogrammed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells do not express the expected cancer genotype, implying that recapitulation of the cancer phenotype is a rare event [11]. The process by which iPCCs reacquire a cancer phenotype was illuminated by the work of Gandre-Babbe et al. who generated iPCCs from malignant cells of two Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia (JMML) patients with somatic heterozygous mutations [12]. Differentiation of JMML iPCCs to the myeloid lineage revealed a similar phenotype to primary JMML cells from patients, including increased proliferative capacity, constitutive activation of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and enhanced STAT5/ERK phosphorylation. Similarly, Chao et al. reported successful reprogramming of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patient cells harboring MLL rearrangement to AML iPCCs [13]. Although the AML iPCCs retained the original genetic abnormalities of patient samples, reprogramming the AML iPCCs reset their leukemic DNA methylation and gene expression patterns. Differentiation to the hematopoietic lineage reestablished leukemic DNA methylation and gave rise to leukemia in vivo. The different genomic alterations found in distinct AML iPCC clones could be used to predict clinical drug responses. These findings illustrated the value of AML iPCCs for investigating the mechanistic basis and clonal properties of human AML.

Interestingly, by using a similar approach, Stricker et al. differentiated glioblastoma (GBM) iPCC-derived neural stem (GNS) cells to the neural lineage [14]. Reprogrammed GBM iPCC-derived GNS cells demonstrated a widespread reset of common GBM-associated epigenetic profiles but still maintained high malignant potential both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that GBM malignancy is not dependent on many previously associated epigenetic characteristics. However, GBM iPCCs differentiated to mesodermal cell types cells showed less malignant potential. Another study also reported loss of some malignant properties in reprogrammed sarcoma cells compared with parental sarcoma cells [15].

Kotini et al. attempted to model the effect of reprogramming on a cancer phenotype by generating iPSCs and iPCCs from the entire spectrum of malignant transformation of myeloid malignancy, from preleukemia to low risk MDS (myeloid plastic syndrome), high risk MDS and secondary AML (acute myeloid leukemia) [16]. They concluded that the stage-specific iPSCs and iPCCs successfully model hematopoietic phenotypes of graded severity by demonstrating stage-specific progression. This result provides a novel platform for modeling cancer diseases by using patient-derived somatic pre-cancer/cancer cells.

Clinically, cancer patients have various responses to chemotherapy drugs. Melanoma reprogrammed iPCCs showed an increased resistance to MAPK inhibition compared to parental cancer cells [17]. iPCCs generated from imatinib-sensitive CML patient cells demonstrated imatinib resistance after reprogramming [18]. In contrast, differentiated cells from colorectal cancer cell reprogrammed iPCCs showed increased sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs compared to parental cells [19]. These data suggest that the degree of similarity between cancer-derived iPCC-derived cells and patient cancer cells is likely to depend on both the “parental” cancer cell type as well as the lineage to which the iPCC is differentiated.

Not all somatic cancer cells can be reprogrammed to iPCCs, and the reprogramming ability of certain cancer cells can be highly variable. Unlike normal somatic cells, which demonstrate substantial epigenetic homogeneity within a cell lineage, malignant cancer cells are highly epigenetically heterogeneous. Full reprogramming of cancer cells is highly dependent on their internal epigenetic network. In 2010, Miyoshi et al. demonstrated successful reprogramming to iPCCs in only 8 of 20 gastrointestinal cancer cell lines when using a viral OSKM expression system [19]. In addition, NOTCH1 initiated T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells have not to date been successfully reprogrammed to a pluripotent state [20], paralleling reported unsuccessful reprogramming in both primary B-ALL blasts and leukemic B cell lines [21]. These findings suggest that differentiation to particular lineages from which cancers arise may impose intrinsic developmental and reprogramming blockades that cannot be overcome by OKSM.

In contrast, the expression of certain oncogenic pathways in cancer lines may obviate the need for all 4 OKSM factors in reprogramming efforts. Utikal et al. demonstrated that ectopic SOX2 is not required for R545 melanoma cell reprogramming [22]. Oshima et al. claimed that OCT3/4, SOX2 and KLF4 (without MYC) are sufficient for colon cancer cell pluripotency induction [23]. Skin cancer cells have been reportedly reprogrammed to the pluripotent state with a single-factor system (miR-302) that has the benefit of not introducing any oncogenic transcription factors [24]. These findings demonstrate that reprogramming conditions may benefit from customization to individual cancer cell profiles.

Somatic cell reprogramming in syndromes with cancer predisposition

PSCs, including ESCs and iPSCs, hold great promise as a disease modeling tool for familial cancer predisposition syndromes [25-28]. Such genetic cancer disease models can be built up by two strategies. One is by introducing genetic alterations into wild-type ESCs or iPSCs using gene editing technologies, such as Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), or clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeat/Cas9 (CRISPR/Cas9) [29-35]. The other is by reprogramming of patient somatic cells (e.g., fibroblasts and blood cells) carrying inherited mutations into iPSCs using a defined transcription factor cocktail (e.g. OSKM). Several cancer predisposition syndromes have been studied using patient-derived iPSCs using this approach.

Li-Fraumeni syndrome

Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) is a rare hereditary autosomal dominant cancer syndrome with a germline mutation in the TP53 gene [25]. In 2015, our group investigated the function of mutant p53 in osteosarcoma genesis using LFS patient-derived iPSCs carrying a G245D germline mutation [36]. Defective osteoblastic differentiation and tumorigenic ability were observed in osteoblasts differentiated from LFS iPSC-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Through transcriptome analysis and functional studies, the dysregulation of long noncoding RNA H19 and its associated imprinted gene network was suggested to contribute to the osteogenic differentiation defects and tumorigenesis in LFS-associated osteosarcoma.

Myelodysplastic syndrome

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a hematological disorder characterized by impaired hematopoiesis and a propensity for anemia and leukemia. Sporadic loss of one copy of the long arm of chromosome 5 [del(5q)] and/or chromosome 7 [del(7q)] is the main cytogenetic characteristic of MDS [37]. Kotini et al. developed del(7q) MDS iPSCs from patient hematopoietic stem cells and demonstrated that del(7q) MDS iPSCs recapitulated the phenotype of defective hematopoietic differentiation [38]. Phenotype-rescue screening of the genes located on Chr7q identified HIPK2, ATP6V0E2, LUC7L2, and EZH2 as haploinsufficient genes related to the MDS phenotype. To further map the spectrum of myeloid malignancy between MDS and AML, Kotini et al. generated a series of iPSC lines from patients with low-risk MDS, high-risk MDS and secondary AML [16]. These patient-derived iPSCs captured a range of leukemia phenotypes with stage specificity. Through a competitive growth assay, they demonstrated this stage-specific iPSC model can be used in drug screening.

Familial adenomatous polyposis

Familial adenomatous polyposis is an inherited cancer syndrome caused by APC mutations and characterized by cancer of the colon and rectum [39]. Crespo et al. generated iPSCs from patient fibroblasts and developed iPSC-derived 3D colonic organoids [40]. They found that 3D colonic organoids with APC mutations exhibited enhanced WNT activity and increased epithelial cell proliferation, findings consistent with the majority of colorectal cancers. XAV939, rapamycin and gentamicin were identified as candidate drugs which reversed the APC mutation-induced phenotype of hyperproliferation in human colonic organoids.

Familial platelet disorder (FPD) with a predisposition to AML

Familial platelet disorder (FPD) is a rare autosomal dominant disease characterized by qualitative and quantitative platelet defects and a predisposition to the development of AML [41]. Minelli et al. derived iPSCs from two pedigrees with germline RUNX1 mutations [42]. Hematopoietic differentiation of these iPSCs demonstrated a phenocopy of the clinical presentation, with phenotype severity correlated to functional RUNX1 levels. Loss of half of RUNX1 activity resulted in less malignant phenotypes, such as primitive erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis, while near complete loss of RUNX1 activity led to more malignant phenotypes, such as amplification of the granulomonocytic lineage and increased genomic instability. Their results emphasize that the FPD iPSC model can elucidate the relationship between RUNX1 levels and leukemia phenotypes.

Noonan syndrome (NS) with JMML

NS is a genetic disorder characterized by a wide spectrum of disorders including developmental delay, learning difficulties, congenital heart abnormalities, short stature, facial dimorphism, and predisposition to hematological malignancies [43]. NS patients with PTPN11 mutations have a tendency to develop juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), an aggressive, difficult-to-treat myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative neoplasm. Mulero-Navarro et al. generated iPSC lines harboring PTPN11 mutations from NS/JMML patient skin fibroblasts and recapitulated several JMML characteristics including hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and increased myeloid population [44]. These NS/JMML iPSC-derived myeloid cells exhibited increased signaling through STAT5 and upregulation of miR-223 and miR-15a. MicroRNA target gene expression levels (e.g., FOXO3, SPTB, NPM1, WHSC1K1 and DICER1) were reduced in iPSC-derived myeloid cells as well as in JMML cells with PTPN11 mutations. Reducing miR-223’s function in NS/JMML iPSCs can restore normal myelopoiesis. This study demonstrated a genotype-phenotype association for JMML and provided novel therapeutic targets.

In contrast to cancer cells, somatic cells maintain an intact genome, permitting more consistent generation of normal and/or diseased iPSCs than cancer iPSCs. Patient-derived iPSCs from somatic cells carrying specific gene aberrations can be differentiated into the desired lineage or tissues to recapitulate the disease phenotypes in vitro and/or in vivo. This approach can be particularly useful in elucidating pathological mechanisms, dissecting cellular origins of cancer types and screening for drug efficacy and toxicity for cancers initiated from definite cellular origin. Pre-malignant and/or malignant tumors derived from differentiated iPSCs with somatic mutations may help identify early-stage cancer drivers and cancer evolution and in turn enable therapies targeted to this stage of disease. Assessment of the malignant potential of patient-derived iPSCs differentiated into different lineages or tissues can clarify the cellular origins of cancers and determine the genetic basis of their phenotypes.

Some iPSCs retain epigenetic evidence of their tissue of origin, potentially affecting the differentiation process. Gene editing technology provides a helpful solution by introducing specific mutations into normal ESCs or wild-type iPSCs [45,46]. Using these powerful gene editing tools to correct gene alterations in patient-derived iPSCs or induce them in wild-type PSCs facilitates provides an ideal isogenic control and enables a detailed reconstruction of the relationship between phenotype and genotype. This strategy not only allows researchers to eliminate unexpected influences from distinct genetic and epigenetic backgrounds but also increases the external validity the cancer disease model.

To date, most established cancer PSC disease models have focused on monogenic diseases, particularly those with an early-onset phenotype. However, most cancers are polygenic disorders. Gene editing to introduce or remove traits for polygenic disorders, while technically more challenging, is also possible with engineered PSCs.

Application of iPSC technology to cancers

During the past decade, PSCs have shown great promise in facilitating regenerative medicine, drug discovery and drug safety assessment. Screening for candidate drugs and testing for differential toxicity are major current applications of PSCs in the cancer-translational field. PSCs and PSC-based disease models facilitate testing for candidate drugs to rescue a specific phenotype driven by a well-defined genotype within human cells. There are several excellent reviews on applications of PSC technology for drug discovery in human diseases (e.g., neural degeneration) [47-50]. Here, we focus on cancer-related drug development. Crespo et al. generated APC mutant iPSCs and applied 3D colonic organoids (COs) to investigate the role of APC mutation in developing colorectal cancer [40]. Using this platform to test the tumor suppression effect of candidate drugs, they demonstrated that XAV939, rapamycin and gentamicin can effectively reverse APC mutation-induced hyperproliferation in human COs. However, XAV939 and rapamycin also affected cell proliferation in wild-type COs, suggesting a very limited therapeutic window for use of XAV939 and rapamycin in colorectal cancers with APC mutations. Moreover, Kotini et al. applied drug testing in a series of iPSCs and/or iPCCs derived from patients with low-risk MDS, high-risk MDS and secondary AML, respectively [16]. They found different responses of hematopoietic progenitor cells differentiated from iPSCs and iPCCs to treatment with 5-AzaC and Rigosertib.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and chemotherapeutic agents are the first-line treatments for many human cancers. One particularly clinically challenging side effect is cardiotoxicity, which presents with a wide spectrum of cardiac complications including heart failure, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmias. Any of these complications may limit the amount or duration of otherwise highly active therapy. Cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells and cardiac fibroblasts generated from iPSCs from both healthy individuals and cancer patients were used to screen the toxicities of U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved TKIs in a high-throughput system. Sharma et al. was able to generate a “cardiac safety index” for these TKIs using a collection of measurements of cardiac viability, contractility and signaling. Moreover, they were able to demonstrate that that cardiotoxicity caused by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)/platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-inhibiting TKIs could be mitigated by up-regulating insulin/IGF signaling in PSC-derived cardiomyocytes [51]. Similarly, doxorubicin is a powerful chemotherapy agent for solid tumors with a well-recognized side effect profile including dose-dependent cardiotoxicity. Burridge et al. generated cardiomyocytes differentiated from breast cancer patient-derived iPSCs and demonstrated that iPSC-derived cardiomyocyte sensitivity to doxorubicin predicted patient predilection for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity [52]. Ideally, a set of assays can be established to enable the restriction of drugs specifically from the patients who will experience unacceptably serious drug-related toxicity, ultimately enabling the wider use of many effective but otherwise risky anticancer agents.

Induced stem cells can also be engineered to function as an anticancer drug or drug-carrier. Neural stem cells (NSCs) are self-renewing multipotent cells capable of replenishing neurons and glial cells. Aboody et al. and Benedetti et al. found that NSCs have the unique ability to home to brain tumor [53,54]. When NSCs were engineered with effective cytotoxic agents, they could home in on tumors and secrete cytotoxic reagents, which were regarded as a promising new therapeutic strategy for glioblastoma [55,56]. Kauer et al. investigated an approach to treat human glioblastoma in a mouse model using therapeutic NSCs encapsulated in a biodegradable, synthetic extracellular matrix. The release of tumor-selective secretable tumor necrosis factor apoptosis inducing ligand (S-TRAIL) from sECM-encapsulated NSCs placed within the resection cavity killed residual tumor cells by inducing caspase-mediated apoptosis and delayed tumor regrowth to significantly increase survival. This study proved the therapeutic effect of NSCs in a preclinical model and facilitated the translation of stem cell-based therapies for the treatment of glioblastoma [57]. Bago et al. used a single-factor SOX2 strategy to transdifferentiate glioblastoma patient-derived fibroblasts into tumor-homing early-staged induced neural stem cells (h-iNSCTEs). h-iNSCTEs engineered to express S-TRAIL show significant cytotoxicity towards human glioblastoma xenografts in a mouse model. This work demonstrated that autologous cell-based therapy can be combined with iPSC technology and genetic engineering to develop novel cell-based antitumor therapies [58,59].

Conclusion

iPSC technology has now been used in cancer research for over ten years, providing a unique platform to investigate the entire transformation process from normal cell to cancer and explore its underlying pathological mechanisms. The two major PSC-based cancer model systems (iPCCs and patient-derived iPSCs) offer unique relative advantages. iPCCs can, in principle, be derived from all cancer types; however, the low reprogramming efficiency of certain cancer cell type limits this technology in practice until more efficient reprogramming methods can be developed. In addition, unexpected phenotypes seen in multiple iPCC-based cancer models highlight the challenges of characterizing and controlling for epigenetic alterations during reprogramming. In contrast, methods for derivation of iPSCs from somatic cells are now well-established. This system avoids sorting out the complicated genomic alterations that occur in cancer cells and allows us to watch as a cancer develops from the earliest stage and prior to acquisition of secondary genetic alterations. The iPSC system models the natural disease development process and has significant potential to illuminate the role of oncogenic genes and/or tumor suppressor genes in the early stage of tumorigenic transformation. In the future, corrected patient iPSCs and disease trait-engineered PSCs generated by genome-editing tools will provide an ideal set of paired isogenic samples to exclude cell-line specific genetic background effects [60-64]. Furthermore, newly developed PSC-related technologies provide more flexible tools to complete PSC-based cancer research. For example, 3D organoid generation and culture techniques facilitate modeling cancer initiation in a more precise and comprehensive human organ microenvironment.

The future use of cell reprogramming systems in cancer research is bright. We hope that the information obtained from the ongoing merger of disparate fields within cancer and regenerative biology will lead to a better understanding of pre-cancer and early cancer transformation in human disease models and finally provide novel cancer prevention tools and personalized therapy for affected cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

J.T. is supported by the Ke Lin Program of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. D.-F.L. is the CPRIT scholar in Cancer Research and supported by NIH Pathway to Independence Award R00 CA181496 and CPRIT Award RR160019.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A, Lensch MW, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K, Daley GQ. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devalla HD, Passier R. Cardiac differentiation of pluripotent stem cells and implications for modeling the heart in health and disease. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah5457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang N, Trujillo CA, Negraes PD, Muotri AR, Lameu C, Ulrich H. Stem cell contributions to neurological disease modeling and personalized medicine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;80:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dianat N, Steichen C, Vallier L, Weber A, Dubart-Kupperschmitt A. Human pluripotent stem cells for modelling human liver diseases and cell therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2013;13:120–132. doi: 10.2174/1566523211313020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yagi T, Ito D, Okada Y, Akamatsu W, Nihei Y, Yoshizaki T, Yamanaka S, Okano H, Suzuki N. Modeling familial Alzheimer’s disease with induced pluripotent stem cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4530–4539. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, Weisenthal LM, Mitsumoto H, Chung W, Croft GF, Saphier G, Leibel R, Goland R, Wichterle H, Henderson CE, Eggan K. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvajal-Vergara X, Sevilla A, D’Souza SL, Ang YS, Schaniel C, Lee DF, Yang L, Kaplan AD, Adler ED, Rozov R, Ge Y, Cohen N, Edelmann LJ, Chang B, Waghray A, Su J, Pardo S, Lichtenbelt KD, Tartaglia M, Gelb BD, Lemischka IR. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature09005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Hoffman JP, Alpaugh RK, Rhim AD, Reichert M, Stanger BZ, Furth EE, Sepulveda AR, Yuan CX, Won KJ, Donahue G, Sands J, Gumbs AA, Zaret KS. An iPSC line from human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma undergoes early to invasive stages of pancreatic cancer progression. Cell Rep. 2013;3:2088–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandre-Babbe S, Paluru P, Aribeana C, Chou ST, Bresolin S, Lu L, Sullivan SK, Tasian SK, Weng J, Favre H, Choi JK, French DL, Loh ML, Weiss MJ. Patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells recapitulate hematopoietic abnormalities of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:4925–4929. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao MP, Gentles AJ, Chatterjee S, Lan F, Reinisch A, Corces MR, Xavy S, Shen J, Haag D, Chanda S, Sinha R, Morganti RM, Nishimura T, Ameen M, Wu H, Wernig M, Wu JC, Majeti R. Human AML-iPSCs reacquire leukemic properties after differentiation and model clonal variation of disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:329–344. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stricker SH, Feber A, Engstrom PG, Caren H, Kurian KM, Takashima Y, Watts C, Way M, Dirks P, Bertone P, Smith A, Beck S, Pollard SM. Widespread resetting of DNA methylation in glioblastoma-initiating cells suppresses malignant cellular behavior in a lineage-dependent manner. Genes Dev. 2013;27:654–669. doi: 10.1101/gad.212662.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore JB 4th, Loeb DM, Hong KU, Sorensen PH, Triche TJ, Lee DW, Barbato MI, Arceci RJ. Epigenetic reprogramming and re-differentiation of a Ewing sarcoma cell line. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3:15. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2015.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotini AG, Chang CJ, Chow A, Yuan H, Ho TC, Wang T, Vora S, Solovyov A, Husser C, Olszewska M, Teruya-Feldstein J, Perumal D, Klimek VM, Spyridonidis A, Rampal RK, Silverman L, Reddy EP, Papaemmanuil E, Parekh S, Greenbaum BD, Leslie CS, Kharas MG, Papapetrou EP. Stage-specific human induced pluripotent stem cells map the progression of myeloid transformation to transplantable leukemia. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:315–328. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernhardt M, Novak D, Assenov Y, Orouji E, Knappe N, Weina K, Reith M, Larribere L, Gebhardt C, Plass C, Umansky V, Utikal J. Melanoma-derived iPCCs show differential tumorigenicity and therapy response. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;8:1379–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumano K, Arai S, Hosoi M, Taoka K, Takayama N, Otsu M, Nagae G, Ueda K, Nakazaki K, Kamikubo Y, Eto K, Aburatani H, Nakauchi H, Kurokawa M. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from primary chronic myelogenous leukemia patient samples. Blood. 2012;119:6234–6242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Nagai K, Hoshino H, Mimori K, Tanaka F, Nagano H, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M. Defined factors induce reprogramming of gastrointestinal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:40–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912407107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, Cheng H, Wang Y, Zheng Y, Liu Y, Liu K, Xu J, Hao S, Yuan W, Zhao T, Cheng T. Reprogramming of Notch1-induced acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells into pluripotent stem cells in mice. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e444. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munoz-Lopez A, Romero-Moya D, Prieto C, Ramos-Mejia V, Agraz-Doblas A, Varela I, Buschbeck M, Palau A, Carvajal-Vergara X, Giorgetti A, Ford A, Lako M, Granada I, Ruiz-Xiville N, Rodriguez-Perales S, Torres-Ruiz R, Stam RW, Fuster JL, Fraga MF, Nakanishi M, Cazzaniga G, Bardini M, Cobo I, Bayon GF, Fernandez AF, Bueno C, Menendez P. Development refractoriness of MLL-rearranged human B cell acute leukemias to reprogramming into pluripotency. Stem Cell Rep. 2016;7:602–618. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Utikal J, Maherali N, Kulalert W, Hochedlinger K. Sox2 is dispensable for the reprogramming of melanocytes and melanoma cells into induced pluripotent stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3502–3510. doi: 10.1242/jcs.054783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oshima N, Yamada Y, Nagayama S, Kawada K, Hasegawa S, Okabe H, Sakai Y, Aoi T. Induction of cancer stem cell properties in colon cancer cells by defined factors. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101735. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin SL, Chang DC, Chang-Lin S, Lin CH, Wu DT, Chen DT, Ying SY. Mir-302 reprograms human skin cancer cells into a pluripotent EScell-like state. RNA. 2008;14:2115–2124. doi: 10.1261/rna.1162708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou R, Xu A, Gingold J, Strong LC, Zhao R, Lee DF. Li-Fraumeni syndrome disease model: a platform to develop precision cancer therapy targeting oncogenic p53. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:908–927. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gingold J, Zhou R, Lemischka IR, Lee DF. Modeling cancer with pluripotent stem cells. Trends Cancer. 2016;2:485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin YH, Jewell BE, Gingold J, Lu L, Zhao R, Wang LL, Lee DF. Osteosarcoma: molecular pathogenesis and iPSC modeling. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23:737–755. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papapetrou EP. Patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells in cancer research and precision oncology. Nat Med. 2016;22:1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yusa K, Rashid ST, Strick-Marchand H, Varela I, Liu PQ, Paschon DE, Miranda E, Ordonez A, Hannan NR, Rouhani FJ, Darche S, Alexander G, Marciniak SJ, Fusaki N, Hasegawa M, Holmes MC, Di Santo JP, Lomas DA, Bradley A, Vallier L. Targeted gene correction of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;478:391–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zou J, Maeder ML, Mali P, Pruett-Miller SM, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Chou BK, Chen G, Ye Z, Park IH, Daley GQ, Porteus MH, Joung JK, Cheng L. Gene targeting of a disease-related gene in human induced pluripotent stem and embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hockemeyer D, Soldner F, Beard C, Gao Q, Mitalipova M, DeKelver RC, Katibah GE, Amora R, Boydston EA, Zeitler B, Meng X, Miller JC, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Jaenisch R. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:851–857. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo Y, Rao M, Zou J. Generation of GFP reporter human induced pluripotent stem cells using AAVS1 safe harbor transcription activator-like effector nuclease. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2014;29:5A.7.1–18. doi: 10.1002/9780470151808.sc05a07s29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding Q, Lee YK, Schaefer EA, Peters DT, Veres A, Kim K, Kuperwasser N, Motola DL, Meissner TB, Hendriks WT, Trevisan M, Gupta RM, Moisan A, Banks E, Friesen M, Schinzel RT, Xia F, Tang A, Xia Y, Figueroa E, Wann A, Ahfeldt T, Daheron L, Zhang F, Rubin LL, Peng LF, Chung RT, Musunuru K, Cowan CA. A TALEN genome-editing system for generating human stem cell-based disease models. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:238–251. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee DF, Su J, Kim HS, Chang B, Papatsenko D, Zhao R, Yuan Y, Gingold J, Xia W, Darr H, Mirzayans R, Hung MC, Schaniel C, Lemischka IR. Modeling familial cancer with induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2015;161:240–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindsley RC, Ebert BL. Molecular pathophysiology of myelodysplastic syndromes. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:21–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotini AG, Chang CJ, Boussaad I, Delrow JJ, Dolezal EK, Nagulapally AB, Perna F, Fishbein GA, Klimek VM, Hawkins RD, Huangfu D, Murry CE, Graubert T, Nimer SD, Papapetrou EP. Functional analysis of a chromosomal deletion associated with myelodysplastic syndromes using isogenic human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:646–655. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durno CA, Gallinger S. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer: new pieces in the pediatric puzzle. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:5–15. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000221889.36501.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crespo M, Vilar E, Tsai SY, Chang K, Amin S, Srinivasan T, Zhang T, Pipalia NH, Chen HJ, Witherspoon M, Gordillo M, Xiang JZ, Maxfield FR, Lipkin S, Evans T, Chen S. Colonic organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for modeling colorectal cancer and drug testing. Nat Med. 2017;23:878–884. doi: 10.1038/nm.4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song WJ, Sullivan MG, Legare RD, Hutchings S, Tan X, Kufrin D, Ratajczak J, Resende IC, Haworth C, Hock R, Loh M, Felix C, Roy DC, Busque L, Kurnit D, Willman C, Gewirtz AM, Speck NA, Bushweller JH, Li FP, Gardiner K, Poncz M, Maris JM, Gilliland DG. Haploinsufficiency of CBFA2 causes familial thrombocytopenia with propensity to develop acute myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Genet. 1999;23:166–175. doi: 10.1038/13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antony-Debre I, Manchev VT, Balayn N, Bluteau D, Tomowiak C, Legrand C, Langlois T, Bawa O, Tosca L, Tachdjian G, Leheup B, Debili N, Plo I, Mills JA, French DL, Weiss MJ, Solary E, Favier R, Vainchenker W, Raslova H. Level of RUNX1 activity is critical for leukemic predisposition but not for thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2015;125:930–940. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-585513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts AE, Allanson JE, Tartaglia M, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome. Lancet. 2013;381:333–342. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61023-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulero-Navarro S, Sevilla A, Roman AC, Lee DF, D’Souza SL, Pardo S, Riess I, Su J, Cohen N, Schaniel C, Rodriguez NA, Baccarini A, Brown BD, Cave H, Caye A, Strullu M, Yalcin S, Park CY, Dhandapany PS, Yongchao G, Edelmann L, Bahieg S, Raynal P, Flex E, Tartaglia M, Moore KA, Lemischka IR, Gelb BD. Myeloid dysregulation in a human induced pluripotent stem cell model of PTPN11-associated juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Cell Rep. 2015;13:504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim K, Zhao R, Doi A, Ng K, Unternaehrer J, Cahan P, Huo H, Loh YH, Aryee MJ, Lensch MW, Li H, Collins JJ, Feinberg AP, Daley GQ. Donor cell type can influence the epigenome and differentiation potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1117–1119. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohi Y, Qin H, Hong C, Blouin L, Polo JM, Guo T, Qi Z, Downey SL, Manos PD, Rossi DJ, Yu J, Hebrok M, Hochedlinger K, Costello JF, Song JS, Ramalho-Santos M. Incomplete DNA methylation underlies a transcriptional memory of somatic cells in human iPS cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:541–549. doi: 10.1038/ncb2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi Y, Inoue H, Wu JC, Yamanaka S. Induced pluripotent stem cell technology: a decade of progress. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:115–130. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inoue H, Nagata N, Kurokawa H, Yamanaka S. iPS cells: a game changer for future medicine. EMBO J. 2014;33:409–417. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mullard A. Stem-cell discovery platforms yield first clinical candidates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:589–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avior Y, Sagi I, Benvenisty N. Pluripotent stem cells in disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:170–182. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma A, Burridge PW, McKeithan WL, Serrano R, Shukla P, Sayed N, Churko JM, Kitani T, Wu H, Holmstrom A, Matsa E, Zhang Y, Kumar A, Fan AC, Del Alamo JC, Wu SM, Moslehi JJ, Mercola M, Wu JC. High-throughput screening of tyrosine kinase inhibitor cardiotoxicity with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burridge PW, Li YF, Matsa E, Wu H, Ong SG, Sharma A, Holmstrom A, Chang AC, Coronado MJ, Ebert AD, Knowles JW, Telli ML, Witteles RM, Blau HM, Bernstein D, Altman RB, Wu JC. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes recapitulate the predilection of breast cancer patients to doxorubicininduced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2016;22:547–556. doi: 10.1038/nm.4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aboody KS, Brown A, Rainov NG, Bower KA, Liu S, Yang W, Small JE, Herrlinger U, Ourednik V, Black PM, Breakefield XO, Snyder EY. Neural stem cells display extensive tropism for pathology in adult brain: evidence from intracranial gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12846–12851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benedetti S, Pirola B, Pollo B, Magrassi L, Bruzzone MG, Rigamonti D, Galli R, Selleri S, Di Meco F, De Fraja C, Vescovi A, Cattaneo E, Finocchiaro G. Gene therapy of experimental brain tumors using neural progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2000;6:447–450. doi: 10.1038/74710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bago JR, Sheets KT, Hingtgen SD. Neural stem cell therapy for cancer. Methods. 2016;99:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Danks MK. Stem and progenitor cell-mediated tumor selective gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2008;15:739–752. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kauer TM, Figueiredo JL, Hingtgen S, Shah K. Encapsulated therapeutic stem cells implanted in the tumor resection cavity induce cell death in gliomas. Nat Neurosci. 2011;15:197–204. doi: 10.1038/nn.3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bago JR, Alfonso-Pecchio A, Okolie O, Dumitru R, Rinkenbaugh A, Baldwin AS, Miller CR, Magness ST, Hingtgen SD. Therapeutically engineered induced neural stem cells are tumour-homing and inhibit progression of glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10593. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bago JR, Okolie O, Dumitru R, Ewend MG, Parker JS, Werff RV, Underhill TM, Schmid RS, Miller CR, Hingtgen SD. Tumor-homing cytotoxic human induced neural stem cells for cancer therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu A, Zhou R, Tu J, Huo Z, Zhu D, Wang D, Gingold JA, Mata H, Rao PH, Liu M, Mohamed AMT, Kong CSL, Jewell BE, Xia W, Zhao R, Hung MC, Lee DF. Establishment of a human embryonic stem cell line with homozygous TP53 R248W mutant by TALEN mediated gene editing. Stem Cell Res. 2018;29:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duan S, Yuan G, Liu X, Ren R, Li J, Zhang W, Wu J, Xu X, Fu L, Li Y, Yang J, Zhang W, Bai R, Yi F, Suzuki K, Gao H, Esteban CR, Zhang C, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Chen Z, Wang X, Jiang T, Qu J, Tang F, Liu GH. PTEN deficiency reprogrammes human neural stem cells towards a glioblastoma stem cell-like phenotype. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10068. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Funato K, Major T, Lewis PW, Allis CD, Tabar V. Use of human embryonic stem cells to model pediatric gliomas with H3.3K27M histone mutation. Science. 2014;346:1529–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1253799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tu J, Huo Z, Liu M, Wang D, Xu A, Zhou R, Zhu D, Gingold J, Shen J, Zhao R, Lee DF. Generation of human embryonic stem cell line with heterozygous RB1 deletion by CRIPSR/Cas9 nickase. Stem Cell Res. 2018;28:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou R, Xu A, Wang D, Zhu D, Mata H, Huo Z, Tu J, Liu M, Mohamed AMT, Jewell BE, Gingold J, Xia W, Rao PH, Hung MC, Zhao R, Lee DF. A homozygous p53 R282W mutant human embryonic stem cell line generated using TALEN-mediated precise gene editing. Stem Cell Res. 2018;27:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]