Significance

The σE stress response monitors outer membrane protein (OMP) assembly. Uninduced, σE is sequestered to the plasma membrane by its anti-sigma factor, RseA. Mutations perturbing OMP biogenesis induce degradation of RseA by the proteases DegS and RseP, liberating σE so it can activate gene expression. σE activity is essential in wild-type Escherichia coli, although why it is essential has remained unclear. We report that batimastat is an inhibitor of RseP, preventing it from cleaving RseA and thereby causing a lethal decrease in σE activity. Surprisingly, lethality is caused by the accumulation of unfolded OMPs, despite a wild-type OMP biogenesis pathway. Hence, σE is essential because it must fine-tune OMP synthesis, assembly, and degradation to prevent the appearance of toxic unfolded OMPs.

Keywords: protein folding, Bam complex, envelope stress response, regulated proteolysis, signal transduction

Abstract

The outer membrane (OM) of Gram-negative bacteria forms a robust permeability barrier that blocks entry of toxins and antibiotics. Most OM proteins (OMPs) assume a β-barrel fold, and some form aqueous channels for nutrient uptake and efflux of intracellular toxins. The Bam machine catalyzes rapid folding and assembly of OMPs. Fidelity of OMP biogenesis is monitored by the σE stress response. When OMP folding defects arise, the proteases DegS and RseP act sequentially to liberate σE into the cytosol, enabling it to activate transcription of the stress regulon. Here, we identify batimastat as a selective inhibitor of RseP that causes a lethal decrease in σE activity in Escherichia coli, and we further identify RseP mutants that are insensitive to inhibition and confer resistance. Remarkably, batimastat treatment allows the capture of elusive intermediates in the OMP biogenesis pathway and offers opportunities to better understand the underlying basis for σE essentiality.

Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) are essential components of the outer membrane (OM). Indeed, two OMPs fulfill essential functions in OM biogenesis (1, 2): LptD is needed to complete the transport pathway that brings LPS to the surface of the OM, and BamA is an essential component of the β-barrel assembly machinery (Bam) that folds OMPs into the OM bilayer. Nascent OMPs are translocated from the cytosol into the periplasmic space as unfolded polypeptides by the Sec translocase. Owing to their extreme hydrophobicity, OMPs require periplasmic chaperones to remain in folding-competent, unfolded states (uOMPs) and avoid hydrophobic collapse into irreversibly misfolded products (3). OMP misfolding triggers degradation by several periplasmic proteases (4). The Bam machine—a complex of BamA and four lipoproteins, BamBCDE—receives chaperone-bound uOMPs and coordinately catalyzes β-barrel folding and membrane insertion (5–9). Successful folding results in mature folded OMPs (fOMPs) whose β-barrel structure is extremely stable and highly resistant to both heat and detergent. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the Bam machine and assembly-defective mutant OMP clients have helped illuminate some of the steps in the assembly pathway (10–16). However, during normal growth at physiological temperature, the process of assembling native substrate uOMPs into fOMPs is so fast that intermediates cannot be detected (17, 18).

The fidelity of OMP biogenesis is monitored by the σE stress-response system (Fig. 1). The appearance of misfolded or uOMPs in the periplasm triggers this response to deploy an alternate RNA polymerase σ factor (σE, encoded by the rpoE gene) that globally alters gene expression. The regulon aims to (i) relieve flux through the OMP biogenesis pathway by downregulating the production of highly abundant OMPs such as OmpA and OmpC via small RNAs (sRNAs) that inhibit translation of their mRNAs (19–21); (ii) increase the OMP biogenesis pathway’s capacity by up-regulating the expression of the Bam complex and periplasmic chaperones (22); and (iii) minimize the accumulation of uOMPs by up-regulating the expression of periplasmic proteases (23).

Fig. 1.

σE stress-response pathway. OMPs (blue) are synthesized in the cytoplasm and secreted to the periplasm by the Sec translocon. Periplasmic uOMPs are assembled into the OM by the BamABCDE complex, resulting in the formation of fOMPs. When the Bam-assembly pathway is compromised, uOMPs accumulate in the periplasm, and a YxF motif activates the DegS protease. DegS initiates the proteolytic pathway, and RseA (orange) is further degraded by the RseP and Clp proteases. σE (green) is released and activates expression from σE-dependent promoters. Up-regulation of σE-effectors (red) results in three arms of the response: down-regulation of translation of omp mRNAs by sRNAs, such as micA; increased assembly of uOMPs to fOMPs by the Bam complex; and increased degradation of uOMPs by DegP. Collectively, these three arms aim to decrease the levels of uOMPs in the periplasm.

Activation of the σE response is highly regulated (Fig. 1). At the core of the response is the single-pass transmembrane protein RseA that functions as an anti-σ factor by binding and sequestering σE at the inner membrane (IM) under noninducing conditions (24). Activation of the response requires a cascade of regulated proteolysis steps that degrade RseA and liberate σE into the cytosol where it can freely access cognate promoters (25). The IM protease DegS initiates the response by sensing OMP assembly stress via its periplasmic domain that binds C-terminal OMP residues (26–28). In mature fOMPs, such residues are buried in the OM bilayer and are inaccessible to DegS. Hence, detection of these peptides by DegS signals an accumulation of unfolded, misfolded, or degraded OMPs in the periplasm. Signal binding activates the DegS protease to cleave RseA, releasing its large periplasmic domain (27–29). The periplasmic protein RseB acts as a negative regulator of σE activation by binding RseA and inhibiting the DegS reaction (30). Signal binding displaces RseB from RseA, thereby facilitating cleavage by DegS (31). The processed RseA1–148 now becomes a substrate for RseP, an IM zinc metalloprotease of the S2P group of intramembrane-cleaving proteases (32). The RseA periplasmic domain prevents proteolysis by RseP, explaining the requirement for the DegS reaction to precede RseP-mediated proteolysis (33). RseP cleaves the RseA transmembrane domain between residues 108 and 109, releasing a soluble RseA1–108 fragment into the cytosol that remains bound to σE (34). A further degradation of RseA1–108 by the cytosolic ClpXP protease finally liberates σE (35).

σE activity is essential for wild-type Escherichia coli (36). Accordingly, both DegS and RseP are also essential (26, 34), suggesting the presence of a basal level of inducing stress even in wild-type cells. Several suppressor mutants that bypass σE essentiality have previously been isolated, but the mechanisms of suppression and, more importantly, the reasons why σE is required for viability remain largely unclear (37–39). Recently, we identified a mutation in rpoE, an rpoE(S2R) that results in up-regulation of σE, allowing a faster and more robust stress response (40). We exploited this property of rpoE(S2R) in a chemical screen to identify small-molecule inhibitors of the σE response, reasoning that rpoE(S2R) would provide greater resistance against inhibition. In this work we identify batimastat as an inhibitor of RseP. We demonstrate that batimastat consequently reduces cellular σE activity and causes cell death. Mutant forms of RseP are strongly resistant to batimastat and prevent inhibition of σE activation. Remarkably, we discovered that treatment with batimastat causes an accumulation of uOMPs, allowing us to detect these otherwise short-lived intermediates. Our findings offer a model to explain the underlying basis for σE essentiality in E. coli.

Results

Chemical Screening.

The rpoE(S2R) mutation results in increased levels of σE and elicits a more robust and rapid response to extracellular stresses resulting from misassembled OMPs (40), allowing the cell to survive under conditions in which the OMP assembly pathway is severely disrupted. Therefore, we reasoned that the rpoE(S2R) mutation should confer resistance to any small molecule that interdicts either OMP assembly or the σE regulatory pathways. The OM and efflux systems of Gram-negative bacteria form a significant defense against the action of antibiotics (41, 42). To circumvent this barrier, we generated a pump-deficient strain of E. coli K-12 ΔtolC (TJS101) to use in our screening attempt to increase the probability of obtaining relevant target–compound pairs. In addition, we constructed an isogenic strain carrying the rpoE(S2R) mutation (TJS102). We subsequently screened these strains against a compound collection from Merck & Co., Inc. previously shown to exhibit growth-inhibitory activity against efflux-deficient E. coli (43, 44). Compounds were screened against TJS101 and TJS102 using an agar-based zone of inhibition (ZOI) assay (SI Appendix, Table S1). Compounds of interest demonstrated an rpoE(S2R) reduction in ZOI size. From this screen we identified a commercially available eukaryotic matrix metalloprotease (MMP) inhibitor known as “batimastat,” a peptidic hydroxamate (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1) that coordinates the catalytic zinc ion and exhibits reversible inhibition of MMPs (45, 46).

Fig. 2.

Batimastat inhibits E. coli proliferation and blocks σE activation. (A) Chemical structure of batimastat. (B and C) Strain TJS101 carrying the plasmid PmicA-gfp reporter was subcultured into fresh LB medium and allowed to grow at 37 °C for 90 min. Batimastat or vehicle was then added to each culture (triangle). (B) Culture density was monitored throughout treatment. (C) GFP fluorescence (FL) was normalized to cell number (FL/OD600 nm), and then the fold change in GFP fluorescence was determined relative to control DMSO-treated cultures. DMSO treatment is shown in black; batimastat treatment at 2× MIC is shown in red; batimastat treatment at 1× MIC is shown in blue; and batimastat treatment at 0.5× MIC is shown in green. Data are the mean ± SD of triplicate samples.

Batimastat Inhibits the Regulation of σE in the Cell.

We measured the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of batimastat for TJS101 and TJS102, confirming both the growth inhibition and the modest resistance conferred by the rpoE(S2R) mutation (Table 1). Batimastat showed no activity against tolC+ E. coli, and we identified AcrAB-TolC as the primary efflux pump responsible for this general resistance, as ΔacrA conferred sensitivity to batimastat with an MIC of 12.5 µM (Table 1).

Table 1.

Batimastat MIC and MIC relative shift in different strain backgrounds

| Strain | MIC, µM | Log2 shift |

| tolC (parent) | 6.25 | |

| tolC rpoE(S2R) | 12.5 | +1 |

| tolC ΔompA ΔompC | 50 | +3 |

| tolC ΔompA | 25 | +2 |

| tolC ΔompC | 25 | +2 |

| tolC ΔompA ΔompC ΔrseP | 50 | +3 |

| ΔacrA (parent) | 12.5 | |

| ΔacrA ΔmalE | 12.5 | 0 |

| ΔacrA ΔmalE rseP(I19N) | >100 | >+3 |

| ΔacrA ΔmalE rseP(I19F) | >100 | >+3 |

| ΔacrA bamA101 | 1.56 | −3 |

| ΔacrA ΔbamB | 3.125 | −2 |

| ΔacrA ΔbamC | 12.5 | 0 |

| ΔacrA bamD(L13P) | 3.125 | −2 |

| ΔacrA ΔbamE | 6.25 | −1 |

| ΔacrA pTrc99 | 12.5 | 0 |

| ΔacrA pTrc99::degP | >100 | >+3 |

To investigate the effect of batimastat on σE activity, we constructed a reporter system using GFP fused to the σE-dependent micA gene promoter (PmicA-gfp) (47). TJS101 carrying the PmicA-gfp reporter was treated in the early exponential phase with either batimastat or DMSO (vehicle control). We observed that batimastat treatment caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of growth (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2) corresponding to a marked decrease in fluorescence after just one doubling time, suggesting reduced expression from PmicA-gfp (Fig. 2C).

Two other major stress responses, the Rcs and Cpx systems, monitor cell envelope biogenesis in E. coli (48). We examined the effect of batimastat treatment on these responses using mCherry fluorescent reporters expressed from well-characterized specific promoters of the Rcs (PrprA) and Cpx (PcpxP) systems. Neither reporter was appreciably sensitive to batimastat treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C). Indeed, we observed changes in fluorescence only long after treatment and once culture density began to decline. We concluded that, among envelope stress responses, batimastat acts specifically to inhibit the σE system. We examined the effect of two other broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors, marimastat and ilomastat, on the activity of σE. At concentrations equimolar to batimastat, marimastat and ilomastat had no effect on cell growth or on the activity of the σE-dependent stress response. When cells were treated with 200 µM of marimastat or ilomastat, we detected only weak σE inhibition and at the later time points of treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) in comparison with the potent inhibition observed with 3–6 µM of batimastat. Taken together, our data demonstrate that batimastat selectively inhibits the σE-dependent stress response and that this is not a general property of MMP inhibitors.

RseP Is a Molecular Target for Batimastat.

As batimastat is a known inhibitor of eukaryotic MMPs, it seemed likely that batimastat lowered σE-dependent gene expression by inhibiting one or more proteases, such as DegS and RseP, which function in the σE regulatory pathway. Inhibition of either protease would cause increased sequestration of σE by RseA and the loss of basal cellular σE activity which is essential for viability (36). Although essential in wild-type E. coli cells, rseP and degS become dispensable in cells lacking both ompA and ompC genes that encode the two most abundant OMPs (49). The rpoE gene remains essential even in a ΔompA ΔompC mutant (49). Consistent with our protease-inhibition hypothesis, a ΔompA ΔompC mutant conferred eightfold resistance to batimastat, while single-deletion mutants conferred intermediate fourfold resistance (Table 1).

To differentiate between DegS and RseP as potential targets, we assayed RseP activity during batimastat treatment of the acrA malE strain using a well-described reporter for RseP activity, MBP-RseA140 (Fig. 3 A and B) (32). This reporter is a fusion of maltose-binding protein (MBP) to the transmembrane domain of RseA, and because it lacks the periplasmic domain of RseA, MBP-RseA140 is a DegS-independent RseP substrate (32). Consistent with published observations (32), a fraction of MBP-RseA140 is cleaved by RseP in vivo to generate a smaller product (Fig. 3A). Upon batimastat treatment, we observed a concentration-dependent inhibition of MBP-RseA140 cleavage, demonstrating that cellular RseP activity is inhibited (Fig. 3 A and B).

Fig. 3.

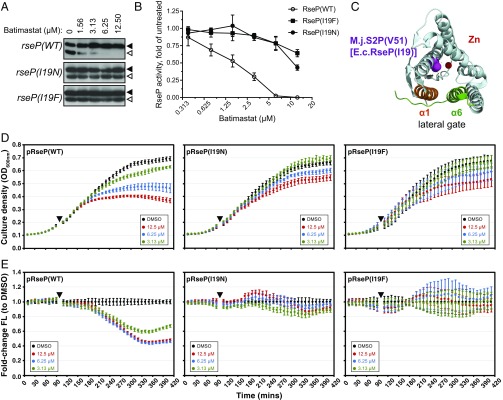

Substitutions at I19 in RseP confer resistance to batimastat and prevent inhibition of σE activity. (A) Cleavage of the MBP-RseA140 reporter in the rseP wild-type or mutant backgrounds. ΔmalE ΔacrA strains with chromosomal rseP alleles and the pMal-rseA140 plasmid were treated with the indicated concentration of batimastat or DMSO for 90 min. Cell lysates were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MBP antibodies. The MBP-RseA140 full-length form is indicated by filled triangles; the RseP-cleaved form is indicated by open triangles. (B) Inhibition of RseP activity by batimastat. MBP-RseA140 cleavage was analyzed as described in A and quantified by ImageJ. The percentage of cleaved reporter in the DMSO control was taken as 1, and the RseP activity in batimastat-treated samples is represented as a fold change from the DMSO control. The graphs generated represent the mean of three biological replicates ± SEM. (C) The periplasmic view of the structure of S2P from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (51) (M.j.RseP), which is a homolog of E. coli RseP (E.c.RseP). E.c.RseP residue I19 corresponds to M.j.RseP residue V51, which is shown in purple. The Zn2+ ion in the active site is shown in red. Two alpha helixes that occlude the lateral gate for a substrate entry are shown in orange and green. (D and E) Strains carrying the PmicA-gfp reporter plasmid were subcultured into fresh LB medium and allowed to grow for 90 min; then batimastat was added to each culture (triangles). Indicated rseP mutant variants were expressed from pCDF plasmids which complemented a ΔrseP2::kan chromosomal deletion. Culture density (D) and the fold change in GFP fluorescence (FL) normalized to cell number (FL/OD600 nm) (E) were determined relative to DMSO-treated control cultures. DMSO treatment is shown in black; batimastat treatment at 2× MIC is shown in red; batimastat treatment at 1× MIC is shown in blue; batimastat treatment at 0.5× MIC is shown in green. Data are the mean ± SD of triplicate samples.

We next sought to isolate rseP mutants that are resistant to inhibition by batimastat. The rseP gene was cloned into a pCDFG plasmid and then was subjected to error-prone PCR mutagenesis. A pool of mutagenized plasmids was used to transform ΔtolC cells, and clones resistant to inhibitory concentrations of batimastat were selected. Two mutations in the same codon, I19N and I19F, were found to confer potent batimastat resistance. When either of these mutations was introduced into the native rseP locus, it conferred eightfold resistance to batimastat, similar to the ΔompA ΔompC strain in which rseP is not essential (Table 1). Taken together, these findings suggest that RseP is a likely cellular target of batimastat.

The I19 residue of RseP is proximal to the conserved HExxH zinc-coordinating motif and is adjacent to the LDG motif that is characteristic of S2P proteases and is required for catalysis (Fig. 3C) (50, 51). It therefore seemed likely that the resistance mutations we identified directly affected batimastat inhibition of RseP. To test this hypothesis, we examined the activity of RseP(I19N) and RseP(I19F) during batimastat treatment by monitoring MBP-RseA140 cleavage and σE activity in cells. In contrast to the inhibition of RseP in wild-type cells, we observed that MBP-RseA140 was cleaved across all concentrations of batimastat (Fig. 3A) in cells expressing either RseP(I19N) or RseP(I19F). Similarly, cellular σE activity in the rseP mutant strains was unaffected by batimastat treatment despite a modest growth inhibition at high drug concentrations (Fig. 3B). These results offer strong evidence that the reduction of cellular σE activity and consequent growth inhibition by batimastat result directly from inhibition of RseP activity.

Inhibition of the σE Response Causes Accumulation of uOMPs.

The σE envelope stress-response system detects and combats periplasmic stress caused by the accumulation of uOMPs (27, 52), but σE is also essential under normal growth conditions (36). The essential contributions of σE to normal cell physiology remain poorly understood. However, having identified batimastat as an inhibitor of RseP, we can begin to address some of these questions.

One of the functions of the σE stress response is to minimize the accumulation of uOMPs in the periplasm by both downregulating translation of OMP-encoding mRNAs and by increasing degradation of their protein products by periplasmic proteases (19, 21, 22, 49). Consequently, uOMP intermediates cannot be readily detected in cells, even in bam mutants that are defective in OMP folding. We tested the effect of σE inhibition on OMP levels, focusing on the folding status of OmpA and OmpC because it is easily assayed based on migration in SDS/PAGE (Fig. 4). Without heat treatment, monomeric OmpA remains folded and migrates faster than denatured OmpA during SDS/PAGE. Mature OmpC is a trimer, which is also SDS- and urea-resistant unless heated, and no monomeric OmpC intermediates can be detected (Fig. 4A). Strikingly, upon treatment with batimastat, we observed the accumulation of unfolded OmpA and unfolded monomeric OmpC in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). We also monitored levels of BamA, an essential component of the Bam complex (7), and DegP, a major periplasmic protease responsible for the degradation of uOMPs (53, 54). Both the bamA and degP genes contain a σE-dependent promoter, and decreases in the expression of these proteins could contribute to the accumulation of uOMPs in the periplasm. However, we did not observe a significant decrease in BamA or DegP expression following batimastat treatment. Based on this result, we conclude that uOMPs accumulate mainly because of their increased synthesis caused by the decreased expression of σE-dependent sRNAs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of σE activity causes the accumulation of uOMPs. (A) Batimastat causes the accumulation of uOMPs in the concentration-dependent manner. Strains were treated with indicated concentration of batimastat for 90 min, and cells were collected, lysed in SDS-loading buffer, and split in two. One sample was boiled (for total levels) and another was taken as is. Samples were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-OmpA and anti-OmpC antibodies. Note that folded OmpA migrates faster on the gel. The presence of monomeric OmpC was taken as unfolded OmpC, as only mature OmpC trimers and no monomers can be detected under normal conditions. (B) Batimastat caused increased accumulation of uOMPs in the bam mutants. Samples were prepared and analyzed as described in A. (C) Accumulation of uOMPs is dependent on the inhibition of RseP. Samples were prepared and analyzed as described in A. (D) Overexpression of protease DegP minimized accumulation of uOMPs. Samples were prepared and analyzed as described in A.

The observation that the double deletion of ompA and ompC confers resistance to batimastat suggested that the accumulation of uOMPs is a contributing factor to growth inhibition during σE down-regulation. To test this, we first examined how batimastat treatment affects OMP assembly in partial loss-of-function Bam complex mutants. Our expectation was that these mutants would accumulate more uOMPs. The two core complex components, BamA and BamD, are essential for cell viability, while accessory components BamB, -C, and -E are dispensable but are important for efficient OMP assembly (6, 7, 55). Following treatment with subinhibitory concentrations of batimastat, bam mutants accumulated higher levels of uOMPs (Fig. 4B). In particular, in bamA101 (56) and bamD(L13P) (57), which contain decreased levels of essential BamA and BamD proteins, the majority of OmpA was unfolded in treated cells.

If the accumulation of uOMPs is deleterious to cell proliferation, then defects in the Bam machine should exacerbate batimastat sensitivity. Consistent with this notion, we observed that the bam mutants were more sensitive to batimastat and that the sensitivity correlated with the degree of uOMPs observed (Fig. 4B and Table 1). For example, bamA101, bamD(L13P), and bamB had the largest increase in sensitivity (eightfold), while bamC and bamE mutants were only modestly more sensitive to batimastat. These results are consistent with our expectation that σE activity would be more important in strains with compromised OMP assembly due to the high levels of uOMPs. As a further test of this expectation, we combined several bam mutants with the batimastat-resistant rseP(I19N) allele (Fig. 4C). No uOMPs were observed in the rseP(I19N) background, confirming that the accumulation of uOMPs is likely a direct result of the inhibition of RseP and subsequently σE-dependent gene expression (Fig. 4C).

To demonstrate that accumulation of uOMPs is the primary source of batimastat-dependent growth inhibition, we performed the same experiment using a strain overexpressing the periplasmic protease DegP (Fig. 4D). As expected, the increased levels of DegP resulted in a significant decrease of uOmpA and uOmpC without affecting levels of fOmpA and total levels of OmpC. Importantly, this strain was also more resistant to batimastat, phenocopying the ompA ompC double mutant (Table 1). Therefore, we concluded that the specific accumulation of uOmpA and uOmpC is the main cause of cell death.

Discussion

We report a chemical inhibitor of the essential σE envelope stress-response pathway. Specifically, we identified the MMP inhibitor batimastat as an inhibitor of the essential periplasmic protease RseP, resulting in reduction of σE activity and cell growth inhibition. Batimastat holds promise as a powerful research tool to enable study of the immediate effects of σE down-regulation on bacterial cell physiology, avoiding the phenotypic adaptation that occurs with the suppressor mutations studied hitherto.

While the function of σE during envelope stress is well documented, why σE remains essential in seemingly unstressed cells during normal growth remains poorly understood. Previous studies showed degS and rseP are essential because their absence decreases σE activity (26, 32), and loss of the anti-sigma factor–encoding rseA can bypass degS and rseP essentiality (26, 34). Simultaneous loss of genes encoding two abundant OMPs, ompA and ompC, can also bypass degS and rseP essentiality, suggesting that OmpA and OmpC expression and localization must be closely monitored; otherwise they become toxic in these backgrounds (49). However, the exact reasons for the toxicity have not been established. Although ompA ompC double mutants can tolerate the loss of degS and rseP and survive with very low σE activity, rpoE cannot be deleted in this background (49). A search for genetic suppressors bypassing rpoE essentiality revealed that loss of the antitoxin HicB or overexpression of its cognate toxin HicA or other toxins such as HigB and YafQ enables survival of rpoE-null mutants (38, 39). HicA and YafQ are mRNA interferase toxins (58, 59), and because their activation likely affects global gene expression, the precise mechanism by which they suppress the requirement for rpoE is not clear. In addition, ptsN and yhbW have been identified as multicopy suppressors of rpoE essentiality (37); however, as with the toxin–antitoxin systems, this effect seems to be indirect.

Having identified a chemical inhibitor of the σE pathway, we sought to follow the physiological changes in cells during inhibitor treatment. Remarkably, we found that down-regulation of σE activity causes an accumulation of uOMPs in the periplasm not previously observed in other studies. Importantly, our data provide evidence that these uOMPs are toxic and contribute to cell growth inhibition, since removal of these uOMPs by increased levels of the periplasmic protease DegP is sufficient to confer resistance to RseP inhibition. In addition, mutants defective in OMP assembly exhibited significantly increased uOMP accumulation during batimastat treatment and correspondingly increased sensitivity to the inhibitor. Our findings offer a model to explain rpoE essentiality. We suggest that even during normal growth σE fine-tunes the balance between OMP synthesis and assembly (Fig. 1), and therefore significant disruption of envelope homeostasis leads to cell-growth inhibition. The σE-mediated OM stress-response system parallels another important quality control measure in the cell. The heat shock response is essential for life at all but very low growth temperatures because it functions to maintain protein quality control in the cytoplasm (60). The σE response performs a similar function in protein quality control in the cell envelope. However, unlike the heat shock response, which responds to any type of unfolded protein in the cytoplasm, the most important clients of the σE response are clearly OMPs.

To go beyond understanding the function of the Bam machine and the surveillance of OM integrity, we envision that our discovery of a selective inhibitor of RseP may enable the discovery of novel antibiotics for human health. The Bam complex is a highly conserved and essential machine required for OM biogenesis. Because the OM provides intrinsic antibiotic resistance to Gram-negative pathogens, the Bam complex is an attractive target for antibiotic development. Since the function of the σE envelope stress response is to counteract β-barrel OMP assembly defects, we propose that batimastat also provides a unique and specific way to screen for chemical inhibitors of the Bam complex by preventing the cell from mitigating the physiological consequences of impaired OMP assembly. In this screen, batimastat is expected to display strong synergy with potential Bam inhibitors, similar to our demonstrations with bam mutants.

Methods

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids.

All strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are presented in SI Appendix, Tables S2–S4, respectively. Strains were routinely propagated either in lysogeny broth (LB, 10 g/L NaCl) or in cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth (CAMHB) under aeration at 37 °C unless otherwise noted. Where appropriate, media were supplemented with kanamycin (Kan, 25 µg/mL), ampicillin (Amp, 25–125 µg/mL), tetracycline (Tet, 20 µg/mL), chloramphenicol (Cam, 20 µg/mL), 0.2% l-arabinose (Ara), or 0.2% d-Fucose. KanR deletion–insertion mutations (and their unmarked derivatives) of bamC, bamE, acrA, malE, ompA, ompC, and tolC were obtained from the Keio collection (61).

MIC Determination.

Overnight cultures were diluted to 105 cells/mL, and 98 µL of cell suspension were transferred to a 96-well plate. The serial twofold dilutions of batimastat were prepared in DMSO, and 2 µL of each dilution was added to the cell suspension. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C, and OD600 was measured using a BioTek Synergy H1 plate reader. The MIC was taken as the lowest batimastat concentration that completely inhibited growth (no OD increase compared with the black control).

Chemical Screening.

TJS101 and TJS1012 were grown to saturation for approximately 18 h in trypticase soy broth (TSB) at 37 °C with shaking. Cultures were then diluted 1:2,000 in molten cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton agar (CAMHA) (cooled to 55 °C), and 30-mL portions were transferred to NUNC Omni trays. The agar was then allowed to solidify at room temperature, and plates were dried with the lid ajar for approximately 30 min in a biosafety cabinet. Test compounds from a subset of the Merck & Co., Inc., compound collection (43) were prepared in master plates at 2 mM in 100% DMSO, and 0.5 µL of each compound was dispensed on the surface of the agar plates using a Labcyte Echo 555 liquid handler. After the compound droplets were absorbed, the plates were inverted, sealed in plastic bags, and incubated at 37 °C for approximately 18 h. To identify compounds of interest, the plates were photographed with illumination through the plate, and images of plates from matching compound sets were compared for differences in the size of the ZOI at each spot. Compounds of interest were confirmed by manually spotting 4 μL of a dose titration starting at 2 mM, and the ZOIs on both strains were visually compared.

RseP Cloning, Deletion, and Mutagenesis.

Primers rseP_5′ and rseP_3′, both of which incorporate overhangs complementary to the sequence flanking the cloning site in pCDFG (described below), were used to amplify rseP from BW25113 E. coli using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase. The purified product obtained after isolation with the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) was used as template to amplify a variable allele library of rseP. Briefly, using the Clontech Diversify PCR Random Mutagenesis Kit under conditions yielding 2.3 mutations per 1,000 bp (160 µM MnSO4 and 40 mM dGTP), 50 ng of purified rseP template was amplified with primers rseP_5′ and rseP_3′ and was gel purified. To facilitate cloning by multiple methods and reduce background during library production, a new plasmid was constructed incorporating a low copy number origin of replication, the Gateway cassette containing attR sites flanking the ccdB gene, and the CAMR gene. Using primers pCDF_5′ and pCDF_3′, a 2,061-bp fragment containing an origin of replication and spectinomycin resistance cassette was amplified from pCDF-1b, and using primers pDONR221_5′ and pDONR221_3′, a 2,547-bp fragment containing the Gateway cassette was amplified from pDONR221. These fragments were combined using In-Fusion HD enzyme (Clontech) and were propagated in One Shot ccdB Survival 2 T1R Competent Cells (Thermo Fisher), yielding plasmid pCDFG. Pilot experiments demonstrated greater efficiency of library cloning using the In-Fusion HD enzyme rather than the Gateway LR Clonase enzyme, so pCDFG was digested with SacI and XhoI, gel purified, and used to clone the PCR-amplified rseP variable allele library in a 2:1 (insert:vector) mole ratio using the In-Fusion HD enzyme. The completed enzyme reaction was dialyzed against water at room temperature for 30 min by spotting 10 µL on a 25-mm MF-Millipore membrane filter (VSWP02500). Following dialysis, 2–5 µL was used to transform electrocompetent BW25113ΔtolC or HAS026 E. coli, and the library was plated on CAMHA plates containing 75 µg/mL spectinomycin. Transformation efficiencies were within twofold for the two strain backgrounds, as a total of 1,800 transformants was obtained in the BW25113ΔtolC background starting with 113 ng of pCDFG vector, and a total of 1,800 transformants was obtained in the HAS026 background starting with 200 ng of pCDFG vector. Colonies were scraped off the plates while resuspended in CAMHB, mixed 1:1 with glycerol, titered to quantify total cfus, and saved at −80 °C.

Agar MICs were performed on parental BW25113ΔtolC and HAS026 strains as well as pCDFG-rseP variable allele-containing libraries. Briefly, batimastat was diluted in DMSO and was added to CAMHA at various concentrations yielding a final DMSO concentration of 1% (vol/vol). Cell suspensions (3 µL) starting at 106 cfu/mL and diluted 10-fold over three additional concentrations were spotted on each concentration of batimastat, and the concentration of batimastat that yielded no growth after 20 h of incubation at 37 °C was scored as the MIC. For resistor selection, 50,000 cfus of the BW25113ΔtolC/pCDFG-rseP variable allele library were plated on 8 µg/mL and 16 µg/mL batimastat (2× and 4× MIC, respectively), and 50,000 cfus of the HAS026/pCDFG-rseP variable allele library were plated on 10 µg/mL and 12 µg/mL batimastat (2× and 2.4× MIC, respectively). Resistors that grew after 20 h of incubation at 37 °C were repurified on CAMHA containing the selecting concentration of batimastat to confirm growth, after which colony PCR was performed using primers pCDFG_MCS5′ and pCDFG_MCS3′ to verify the presence of the rseP insert. Once resistance and rseP presence were confirmed, the variable allele was sequenced using primers pCDFGseq1 and pCDFGseq2 to determine whether a mutation was present. To verify that the variable allele was causal for the resistance, pCDFG-rseP was purified from each resistor and retransformed into a fresh HAS026 background, at which time plasmid was maintained and selected for use with spectinomycin. Two clones of each transformant were isolated, propagated in the presence of spectinomycin, retested for agar MIC of batimastat after 20 h of incubation at 37 °C, and then, after an additional 48 h at room temperature, resequenced to confirm variation in the additional rseP allele.

The pBAD18::rseP plasmid was constructed by PCR amplification of the rseP gene from MC4100 chromosomal DNA with SacI_RBS_ rseP_forward and XbaI_rseP_reverse primers, and the PCR product was cloned into the ScaI/XbaI site of pBAD18.

The ΔrseP2::kan deletion was constructed by PCR amplification of the KanR cassette of pKD4 with oligonucleotides rseP_kanKD4_F and rseP_KD4v2_P1_R. The DNA product was used to transform the recombineering strain DY378 carrying pBAD18::RseP (MG2402) to complement a chromosomal rseP deletion in an arabinose-dependent manner, resulting in MG2433. The ΔrseP2::kan mutation removes the first 1,238 nt of the rseP gene, removing one σE promoter of the essential bamA gene downstream but preserving another within the 3′ end of rseP.

To introduce the RsePI19N or I19F mutation into the chromosome by recombineering, we first crossed Ara-dependent MG2433 with a yaeH-I::cam allele (see below) by P1 transduction to genetically link the ΔrseP2::kan locus. CamR transductants that retained KanR were purified in the presence of Ara (JM039). Next, the rsePI19N/I19F alleles were amplified from pCDF*::rseP(I19N) and pCDF*::rseP(I19F), respectively, using primers rseP + 51 forward and rseP_Red reverse. The resulting PCR products were transformed into strain JM039 (+Ara). After transformation recovery in the presence of Ara, cells were washed with water and plated onto LB agar + d-Fucose (added to ensure complete shut-off of Ara-dependent rseP expression from the pBAD18 promoter). Resulting colonies were purified onto LB agar + d-Fucose and were screened for CamR and the presence of either rseP19N or rseP19F (JM054 and JM055, respectively) using primers rseP 5′ and rseP mid. TJS101 was crossed with lysates from JM054 and JM055, and CamR transductants were selected. Purified transducants were screened for linkage to their respective mutated rsePI19 alleles via PCR amplification using rseP_5′ and rseP_3′ and subsequent DNA sequencing with rseP_mid (MG3100, MG3101).

A CamR cassette was amplified from pKD3 using oligonucleotides yaeH-I -P1 forward and yaeH-I -P2 reverse. The DNA product was used to transform recombineering strain DY378 such that the CamR cassette would insert into an intergenic region between yaeH and yaeI, with the CamR cassette oriented toward yaeH (JM148).

Measurement of in Vivo σE Activity.

The pACYCmicA-GFP reporter plasmid was constructed by PCR amplifying plasmid pUAE60 (47) with oligonucleotides micAGFP_GG_BsmBI_F and micAGFP_GG_BsmBI_R and cloning the product into the EcoRV site of pACYC184, generating a CamR TetS reporter plasmid.

Strains carrying pACYCmicA-GFP were grown overnight in LB supplemented with Cam. Cultures were inoculated into fresh LB at a 1:100 dilution, and 196 μL per well was dispensed into a 96-well black, clear-bottomed microtiter plate (Corning no. 3603). Cultures were grown at 37 °C with aeration in a BioTek Synergy H1 plate reader for 1.5 h. Plates were then removed from the plate reader, and 4 μL of batimastat or DMSO was added. Plates were returned to the plate reader for growth. Culture density (absorbance at 600 nm) and fluorescence (excitation at 481 nm and emission at 507 nm) were monitored at 10-min intervals. GFP fluorescence (FL) was normalized to cell number (that is, FL/OD600 nm), and then the fold change in the fluorescence of batimastat-treated cultures was calculated relative to DMSO-treated cultures.

Detection of uOMPs.

Overnight cultures were subcultured 1:100 in fresh LB, and 2 mL was aliquoted into each well of a 24-well microtiter plate (Corning no. 3526). Cultures were grown at 37 °C with aeration in a BioTek Synergy H1 plate reader for 1.5 h. Plates were then removed from the plate reader, and 40 μL of batimastat or DMSO was added to the wells. Plates were returned to the plate reader for growth for 1 h to allow sufficient time for inhibition of growth but not culture lysis. Cells were harvested and normalized to A600 nm = 20 in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 6.8, supplemented with 4 U/mL of benzonase. Cells were subjected to five freeze/thaw cycles. An equal volume of 2× SDS/PAGE sample buffer was added, and samples were split into two; one was boiled for 10 min (total OMP levels), and the other was used as is (for uOMPs). Samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and then immunoblotted with rabbit antisera raised against LamB, OmpA, BamA, OmpC, and DegP.

In Vivo RseP Activity Assay.

Strains carrying pMal-rseA140 were grown overnight in LB supplemented with Amp. Overnight cultures were subcultured 1:100 in fresh LB, and 2 mL was aliquoted into each well of a 24-well microtiter plate (Corning no. 3526). Cultures were grown at 37 °C with aeration in a BioTek Synergy H1 plate reader for 1.5 h. Plates were then removed from the plate reader, and 40 μL of batimastat or DMSO was added to the wells. Plates were returned to the plate reader for growth for 1 h to allow sufficient time for inhibition of growth but not culture lysis. Cells were harvested and normalized to A600 nm = 10 in SDS/PAGE sample buffer. Samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and then immunoblotted with rabbit antisera raised against MBP. The intensity of the bands corresponding to full-length and cleaved MBP-RseA140 was quantified by ImageJ. The percentage of cleaved MBP-RseA140 relative to the total levels in the DMSO vehicle controls was set as 1, and RseP activity in the treated samples was represented as the fold change relative to the DMSO vehicle control. Graphs present the mean ± SEM of three biological replicates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by internal Merck & Co., Inc. funds and by a grant from Merck & Co., Inc. (to T.J.S.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: C.J.B., J.C.M., R.E.P., D.R., P.A.M., H.W., C.G.G., B.S., T.A.B., T.R., and S.S.W. are, or were at the time this work was conducted, employees of Merck & Co., Inc. and may be shareholders. Research was supported by internal Merck funds. T.J.S. was supported by a grant from Merck & Co., Inc.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1806107115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Okuda S, Sherman DJ, Silhavy TJ, Ruiz N, Kahne D. Lipopolysaccharide transport and assembly at the outer membrane: The PEZ model. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:337–345. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konovalova A, Kahne DE, Silhavy TJ. Outer membrane biogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2017;71:539–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiffrin B, Brockwell DJ, Radford SE. Outer membrane protein folding from an energy landscape perspective. BMC Biol. 2017;15:123. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0464-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soltes GR, Martin NR, Park E, Sutterlin HA, Silhavy TJ. Distinctive roles for periplasmic proteases in the maintenance of essential outer membrane protein assembly. J Bacteriol. 2017;199:e00418-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00418-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim S, et al. Structure and function of an essential component of the outer membrane protein assembly machine. Science. 2007;317:961–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1143993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sklar JG, et al. Lipoprotein SmpA is a component of the YaeT complex that assembles outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6400–6405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701579104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu T, et al. Identification of a multicomponent complex required for outer membrane biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2005;121:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagan CL, Kahne D. The reconstituted Escherichia coli Bam complex catalyzes multiple rounds of β-barrel assembly. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7444–7446. doi: 10.1021/bi2010784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagan CL, Kim S, Kahne D. Reconstitution of outer membrane protein assembly from purified components. Science. 2010;328:890–892. doi: 10.1126/science.1188919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doerner PA, Sousa MC. Extreme dynamics in the BamA β-barrel seam. Biochemistry. 2017;56:3142–3149. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warner LR, Gatzeva-Topalova PZ, Doerner PA, Pardi A, Sousa MC. Flexibility in the periplasmic domain of BamA is important for function. Structure. 2017;25:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCabe AL, Ricci D, Adetunji M, Silhavy TJ. Conformational changes that coordinate the activity of BamA and BamD allowing beta-barrel assembly. J Bacteriol. 2017;199:e00373-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00373-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rigel NW, Ricci DP, Silhavy TJ. Conformation-specific labeling of BamA and suppressor analysis suggest a cyclic mechanism for β-barrel assembly in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5151–5156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302662110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricci DP, Hagan CL, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. Activation of the Escherichia coli β-barrel assembly machine (Bam) is required for essential components to interact properly with substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3487–3491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201362109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wzorek JS, Lee J, Tomasek D, Hagan CL, Kahne DE. Membrane integration of an essential β-barrel protein prerequires burial of an extracellular loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:2598–2603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616576114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, et al. Characterization of a stalled complex on the β-barrel assembly machine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:8717–8722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ureta AR, Endres RG, Wingreen NS, Silhavy TJ. Kinetic analysis of the assembly of the outer membrane protein LamB in Escherichia coli mutants each lacking a secretion or targeting factor in a different cellular compartment. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:446–454. doi: 10.1128/JB.01103-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansen C, Heutink M, Tommassen J, de Cock H. The assembly pathway of outer membrane protein PhoE of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:3792–3800. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansen J, Rasmussen AA, Overgaard M, Valentin-Hansen P. Conserved small non-coding RNAs that belong to the sigmaE regulon: Role in down-regulation of outer membrane proteins. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen AA, et al. Regulation of ompA mRNA stability: The role of a small regulatory RNA in growth phase-dependent control. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gogol EB, Rhodius VA, Papenfort K, Vogel J, Gross CA. Small RNAs endow a transcriptional activator with essential repressor functions for single-tier control of a global stress regulon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12875–12880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109379108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dartigalongue C, Missiakas D, Raina S. Characterization of the Escherichia coli sigma E regulon. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20866–20875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhodius VA, Suh WC, Nonaka G, West J, Gross CA. Conserved and variable functions of the sigmaE stress response in related genomes. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ades SE, Connolly LE, Alba BM, Gross CA. The Escherichia coli sigma(E)-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-sigma factor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2449–2461. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ades SE. Regulation by destruction: Design of the sigmaE envelope stress response. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alba BM, Zhong HJ, Pelayo JC, Gross CA. degS (hhoB) is an essential Escherichia coli gene whose indispensable function is to provide sigma (E) activity. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1323–1333. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh NP, Alba BM, Bose B, Gross CA, Sauer RT. OMP peptide signals initiate the envelope-stress response by activating DegS protease via relief of inhibition mediated by its PDZ domain. Cell. 2003;113:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilken C, Kitzing K, Kurzbauer R, Ehrmann M, Clausen T. Crystal structure of the DegS stress sensor: How a PDZ domain recognizes misfolded protein and activates a protease. Cell. 2004;117:483–494. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grigorova IL, et al. Fine-tuning of the Escherichia coli sigmaE envelope stress response relies on multiple mechanisms to inhibit signal-independent proteolysis of the transmembrane anti-sigma factor, RseA. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2686–2697. doi: 10.1101/gad.1238604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cezairliyan BO, Sauer RT. Inhibition of regulated proteolysis by RseB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3771–3776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611567104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaba R, et al. Signal integration by DegS and RseB governs the σ E-mediated envelope stress response in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2106–2111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019277108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akiyama Y, Kanehara K, Ito K. RseP (YaeL), an Escherichia coli RIP protease, cleaves transmembrane sequences. EMBO J. 2004;23:4434–4442. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akiyama K, et al. Roles of the membrane-reentrant β-hairpin-like loop of RseP protease in selective substrate cleavage. eLife. 2015;4:e08928. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanehara K, Ito K, Akiyama Y. YaeL (EcfE) activates the sigma(E) pathway of stress response through a site-2 cleavage of anti-sigma(E), RseA. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2147–2155. doi: 10.1101/gad.1002302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flynn JM, Levchenko I, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Modulating substrate choice: The SspB adaptor delivers a regulator of the extracytoplasmic-stress response to the AAA+ protease ClpXP for degradation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2292–2301. doi: 10.1101/gad.1240104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Las Peñas A, Connolly L, Gross CA. SigmaE is an essential sigma factor in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6862–6864. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6862-6864.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayden JD, Ades SE. The extracytoplasmic stress factor, sigmaE, is required to maintain cell envelope integrity in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Button JE, Silhavy TJ, Ruiz N. A suppressor of cell death caused by the loss of sigmaE downregulates extracytoplasmic stress responses and outer membrane vesicle production in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1523–1530. doi: 10.1128/JB.01534-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daimon Y, Narita S, Akiyama Y. Activation of toxin-antitoxin system toxins suppresses lethality caused by the loss of σE in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:2316–2324. doi: 10.1128/JB.00079-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Konovalova A, Schwalm JA, Silhavy TJ. A suppressor mutation that creates a faster and more robust σE envelope stress response. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:2345–2351. doi: 10.1128/JB.00340-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young K, Silver LL. Leakage of periplasmic enzymes from envA1 strains of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3609–3614. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3609-3614.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sulavik MC, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1126–1136. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1126-1136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kodali S, et al. Determination of selectivity and efficacy of fatty acid synthesis inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1669–1677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howe JA, et al. Selective small-molecule inhibition of an RNA structural element. Nature. 2015;526:672–677. doi: 10.1038/nature15542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davies B, Brown PD, East N, Crimmin MJ, Balkwill FR. A synthetic matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor decreases tumor burden and prolongs survival of mice bearing human ovarian carcinoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2087–2091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mosyak L, et al. Crystal structures of the two major aggrecan degrading enzymes, ADAMTS4 and ADAMTS5. Protein Sci. 2008;17:16–21. doi: 10.1110/ps.073287008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mutalik VK, Nonaka G, Ades SE, Rhodius VA, Gross CA. Promoter strength properties of the complete sigma E regulon of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7279–7287. doi: 10.1128/JB.01047-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grabowicz M, Silhavy TJ. Envelope stress responses: An interconnected safety net. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Douchin V, Bohn C, Bouloc P. Down-regulation of porins by a small RNA bypasses the essentiality of the regulated intramembrane proteolysis protease RseP in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12253–12259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanehara K, Akiyama Y, Ito K. Characterization of the yaeL gene product and its S2P-protease motifs in Escherichia coli. Gene. 2001;281:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00823-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feng L, et al. Structure of a site-2 protease family intramembrane metalloprotease. Science. 2007;318:1608–1612. doi: 10.1126/science.1150755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mecsas J, Rouviere PE, Erickson JW, Donohue TJ, Gross CA. The activity of sigma E, an Escherichia coli heat-inducible sigma-factor, is modulated by expression of outer membrane proteins. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2618–2628. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lipinska B, Zylicz M, Georgopoulos C. The HtrA (DegP) protein, essential for Escherichia coli survival at high temperatures, is an endopeptidase. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1791–1797. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1791-1797.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim KI, Park SC, Kang SH, Cheong GW, Chung CH. Selective degradation of unfolded proteins by the self-compartmentalizing HtrA protease, a periplasmic heat shock protein in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1363–1374. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malinverni JC, et al. YfiO stabilizes the YaeT complex and is essential for outer membrane protein assembly in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:151–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aoki SK, et al. Contact-dependent growth inhibition requires the essential outer membrane protein BamA (YaeT) as the receptor and the inner membrane transport protein AcrB. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:323–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahoney TF, Ricci DP, Silhavy TJ. Classifying β-barrel assembly substrates by manipulating essential Bam complex members. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:1984–1992. doi: 10.1128/JB.00263-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jørgensen MG, Pandey DP, Jaskolska M, Gerdes K. HicA of Escherichia coli defines a novel family of translation-independent mRNA interferases in bacteria and archaea. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1191–1199. doi: 10.1128/JB.01013-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Motiejūnaite R, Armalyte J, Markuckas A, Suziedeliene E. Escherichia coli dinJ-yafQ genes act as a toxin-antitoxin module. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;268:112–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou YN, Kusukawa N, Erickson JW, Gross CA, Yura T. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli mutants that lack the heat shock sigma factor sigma 32. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3640–3649. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3640-3649.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baba T, et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: The Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.