Abstract

Draft genomes of the species Annulohypoxylon stygium, Aspergillus mulundensis, Berkeleyomyces basicola (syn. Thielaviopsis basicola), Ceratocystis smalleyi, two Cercospora beticola strains, Coleophoma cylindrospora, Fusarium fracticaudum, Phialophora cf. hyalina and Morchella septimelata are presented. Both mating types (MAT1-1 and MAT1-2) of Cercospora beticola are included. Two strains of Coleophoma cylindrospora that produce sulfated homotyrosine echinocandin variants, FR209602, FR220897 and FR220899 are presented. The sequencing of Aspergillus mulundensis, Coleophoma cylindrospora and Phialophora cf. hyalina has enabled mapping of the gene clusters encoding the chemical diversity from the echinocandin pathways, providing data that reveals the complexity of secondary metabolism in these different species. Overall these genomes provide a valuable resource for understanding the molecular processes underlying pathogenicity (in some cases), biology and toxin production of these economically important fungi.

Keywords: Beta vulgaris, Carya cordiformis, echinocandin gene clusters, mulundocandins, Pitch canker, peumocandins

Acknowledgments

The authors of the research on the Berkeleyomyces basicola, Ceratocystis smalleyi, and Fusarium fracticaudum genomes thank the University of Pretoria, the Tree Protection Co-operative Programme (TPCP), the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Tree Health Biotechnology, the National Research Foundation, the Genomics Research Institute (GRI) and the DST-NRF SARCHI chair on Fungal Genomics for their financial support.

The research on Cercospora beticola was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project NYG-625424, and the Director’s Controlled Endowment Fund of The New York Agricultural Experiment Station, Cornell University, Geneva, New York, USA.

The research on the genomes of Coleophoma cylindrospora, Phialophora cf. hyalina, and Aspergillus mulundensis was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grants 31629001 to Z.A., 31741004 to Q.Y., Welch Foundation Grant AU-0042-20030616 to ZA, and the Kay and Ben Fortson Endowment to GFB.

REFERENCES

- Afgan E, Baker D, Van den Beek M, Blankenberg D, Bouvier D, et al. (2016) The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Research 44: W3–W10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Adawi AO, Barnes I, Khan IA, Al Subhi AM, Al Jahwari AA, et al. (2013) Ceratocystis manginecans associated with a serious wilt disease of two native legume trees in Oman and Pakistan. Australasian Plant Pathology 42: 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Albu S, Sharma S, Bluhm BH, Price PP, Schneider RW, et al. (2017) Draft genome sequence of Cercospora cf. sigesbeckiae, a causal agent of Cercospora leaf blight on soybean. Genome Announcements 5: e00708–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al–Subhi AM, Al-Adawi AO, Van Wyk M, Deadman ML, Wingfield MJ. (2006) Ceratocystis omanensis, a new species from diseased mango trees in Oman. Mycological Research 110: 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, et al (2012) SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single–cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology 19: 455–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley MJ, Broome CE. (1850) Notices of British fungi. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, ser. 2 5: 455–465. [Google Scholar]

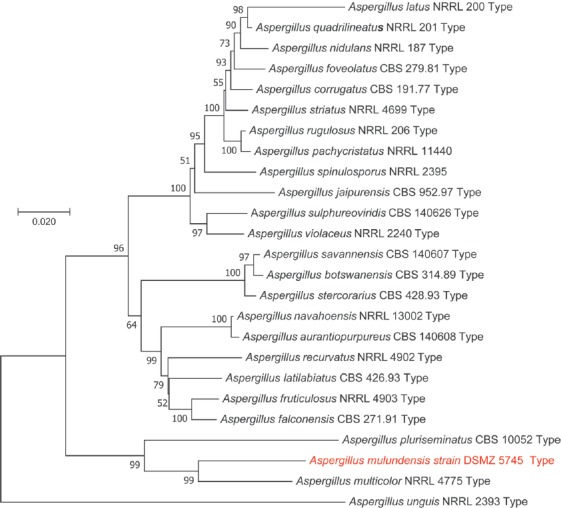

- Bills GF, Yue Q, Chen L, Li Y, An Z, et al. (2016) Aspergillus mulundensis sp. nov., a new species for the fungus producing the antifungal echinocandin lipopeptides, mulundocandins. Journal of Antibiotics 69: 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W. (2011) Scaffolding pre–assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 27: 578–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boetzer M, Pirovano W. (2012) Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biology 13: R56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. (2014) Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel BL, Korf I, Robb SM, Parra G, Ross E, et al. (2008) MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Research 18: 188–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand R, Pal C, Singh V, Kumar M, Singh VK, et al. (2015) Draft genome sequence of Cercospora canescens: a leaf spot causing pathogen. Current Science 109: 2103. [Google Scholar]

- Chen AJ, Frisvad JC, Sun BD, Varga J, Kocsubé S, et al (2016) Aspergillus section Nidulantes (formerly Emericella): Polyphasic taxonomy, chemistry and biology. Studies in Mycology 84: 1–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara M, Fanelli F, Mule G, Logrieco AF, Pesole G, et al. (2015) Genome sequencing of multiple isolates highlights subtelomeric genomic diversity within Fusarium fujikuroi. Genome Biology and Evolution 7: 3062–3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Groenewald JZ. (2016) They seldom occur alone. Fungal Biology 120: 1392–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. (2012) jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods 9: 772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub ME, Ehrenshaft M. (2000) The photoactivated Cercospora toxin cercosporin: contributions to plant disease and fundamental biology. Annual Review of Phytopathology 38: 461–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

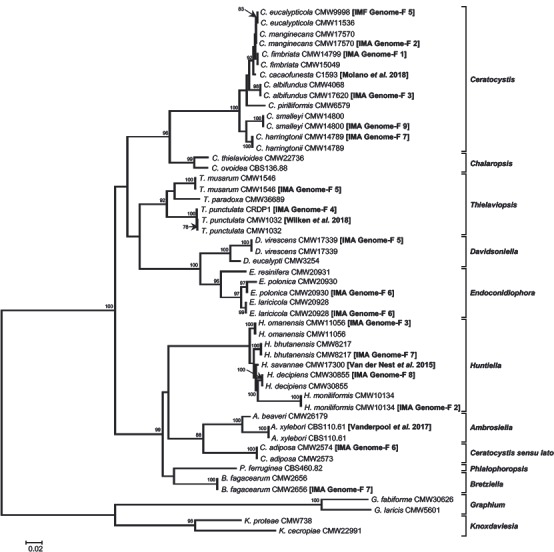

- De Beer ZW, Duong TA, Barnes I, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. (2014) Redefining Ceratocystis and allied genera. Studies in Mycology 79: 187–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beer ZW, Marincowitz S, Duong TA, Wingfield MJ. (2017) Bretziella, a new genus to accommodate the oak wilt fungus, Ceratocystis fagacearum (Microascales, Ascomycota). MycoKeys 27: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos L, Steenkamp ET, Martin SH, Santana QC, Fourie G, et al. (2014) Genome-wide macrosynteny among Fusarium species in the Gibberella fujikuroi complex revealed by amplified fragment length polymorphisms. PLoS ONE 9: e114682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

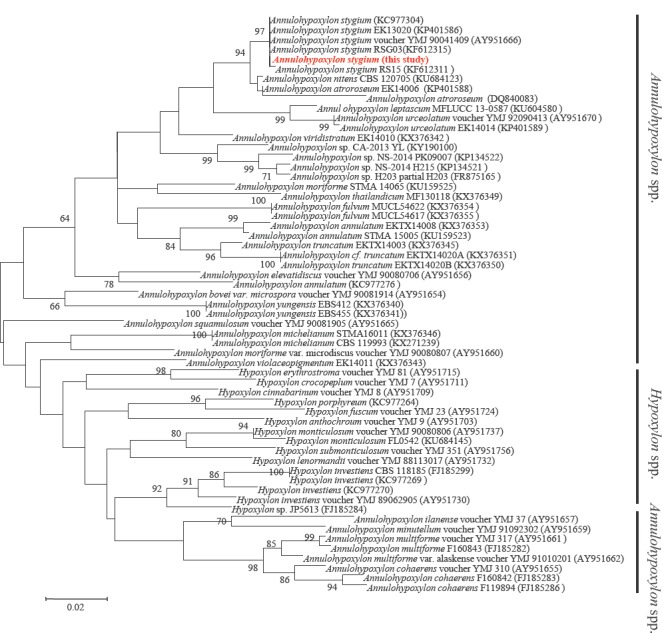

- Deng Y, van Peer AF, Lan FS, Wang QF, Jiang Y, et al (2016) Morphological and molecular analysis identifies the associated fungus (“Xianghui”) of the medicinal white jelly mushroom, Tremella fuciformis, as Annulohypoxylon stygium. International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms 18: 253–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

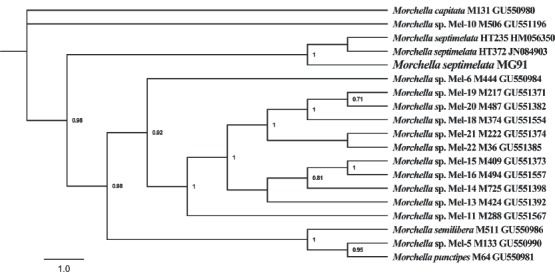

- Du XH, Zhao Q, O’Donnell K, Rooney AP, Yang ZL. (2012) Multigene molecular phylogenetics reveals true morels (Morchella) are especially species-rich in China. Fungal Genetics and Biology 49: 455–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong TA, De Beer ZW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. (2013) Characterization of the mating–type genes in Leptographium procerum and Leptographium profanum. Fungal Biology 117: 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht CJ, Harrington TC, Alfenas A. (2007) Ceratocystis wilt of cacao – a disease of increasing importance. Phytopathology 97: 1648–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht CJB, Harrington TC. (2005) Intersterility, morphology and taxonomy of Ceratocystis fimbriata on sweet potato, cacao and sycamore. Mycologia 97: 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English AC, Richards S, Han Y, Wang M, Vee V. et al (2012) Mind the gap: upgrading genomes with Pacific Biosciences RL long–read sequencing technology. PLoS ONE 7: e47768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erixon P, Svennblad B, Britton T, Oxelman B. (2003) Reliability of Bayesian posterior probabilities and bootstrap frequencies in phylogenetics. Systematic Biology 52: 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floudas D, Binder M, Riley R, Barry K, Blanchette RA, et al. (2012) The Paleozoic origin of enzymatic lignin decomposition reconstructed from 31 fungal genomes. Science 336: 1715–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourie A, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD, Barnes I. (2014) Molecular markers delimit cryptic species in the Ceratocystis fimbriata sensu lato complex. Mycological Progress 14: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Franc GD. (2010) Ecology and epidemiology of Cercospora beticola. In: Cercospora Leaf Spot of Sugar Beet and Related Species (Lartey RT, Weiland JJ, Panella L, Crous PW, Windels CE, eds): 7–19. St Paul, MN: Americal Phytopathological Society Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geiser DM, Aoki T, Bacon CW, Baker SE, Bhattacharyya MK, et al. (2013) One fungus, one name: defining the genus Fusarium in a scientifically robust way that preserves longstanding use. Phytopathology 103: 400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser DM, Ivey ML, Hakiza G, Juba JH, Miller SA. (2005) Gibberella xylarioides (anamorph: Fusarium xylarioides), a causative agent of coffee wilt disease in Africa, is a previously unrecognized member of the G. fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 97: 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

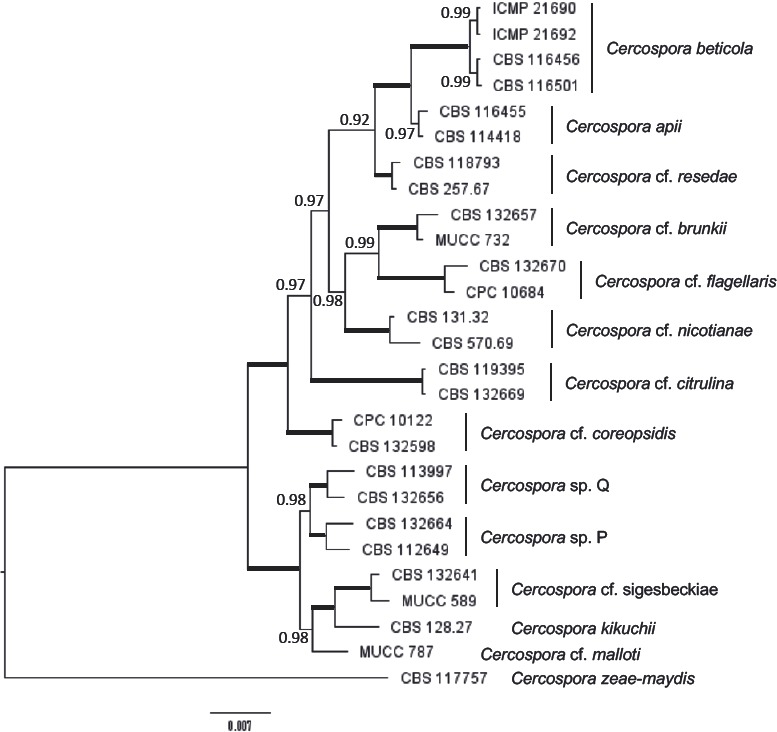

- Groenewald JZ, Nakashima C, Nishikawa J, Shin HD, Park JH, et al. (2013) Species concepts in Cercospora: spotting the weeds among the roses. Studies in Mycology 75: 115–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, et al. (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum–likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic Biology 59: 307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biology 11: R7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsted BD, Fairchild DG. (1891) Sweet potato black rot. Journal of Mycology 7: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington TC. (2009) The genus Ceratocystis. Where does the oak wilt fungus fit? In: Proceedings of the 2nd national Oak Wilt symposium (Appel DN, et al. eds): 1–16. Austin, TX: USDA Forest Service, Forest Health Protection,. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington TC, Kazmi MR, Al-Sadi AM, Ismail SI. (2014) Intraspecific and intragenomic variability of ITS rDNA sequences reveals taxonomic problems in Ceratocystis fimbriata sensu stricto. Mycologia 106: 224–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RS. (2007) Improved Pairwise Alignment of Genomic DNA. Ph thesis, Pennsylvania State University, Department of Computer Science and Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- Hawser S, Borgonovi M, Markus A, Isert D. (1999) Mulundocandin, an echinocandin–like lipopeptide antifungal agent: biological activities in vitro. Journal of Antibiotics 52: 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

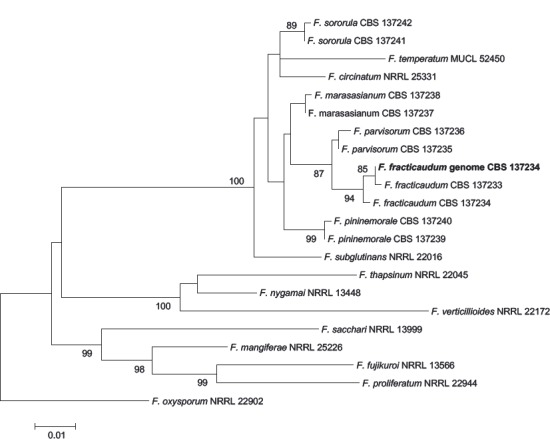

- Herron DA, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD, Rodas CA, Marincowitz S, et al. (2015) Novel taxa in the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex from Pinus spp. Studies in Mycology 80: 131–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

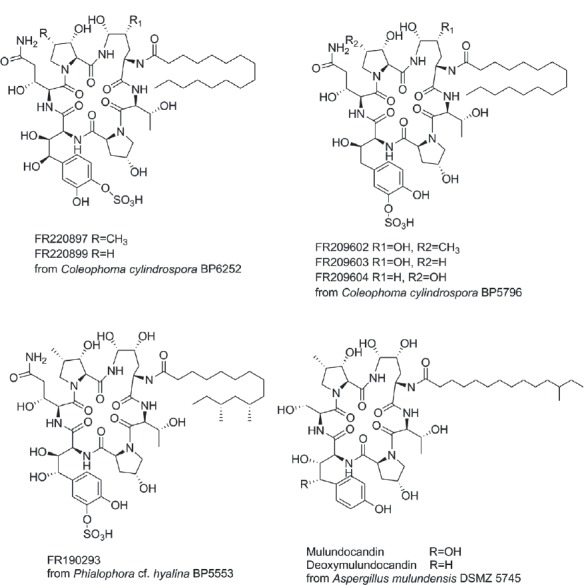

- Hino M, Fujie A, Iwamoto T, Hori Y, Hashimoto M, et al. (2001) Chemical diversity in lipopeptide antifungal antibiotics. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 27: 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie EA, Rice SF, Weber NS, Smith JE. (2016) Isotopic evidence indicates saprotrophy in post-fire Morchella in Oregon and Alaska. Mycologia 108: 638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff KJ, Stanke M. (2013) WebAUGUSTUS - a web service for training AUGUSTUS and predicting genes in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Research 41: 123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y, Takase S, Tsurumi Y, Hashimoto M, Hino M. (2004) WF14573 or its salt, production thereof and use thereof. US Patent 6 730–776. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HM, Ju YM, Rogers JD. (2005) Molecular phylogeny of Hypoxylon and closely related genera. Mycologia 97: 844–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Wang YY, Zhao YY, Jiao YX, Li XF, et al. (2008) First report of taro black rot caused by Ceratocystis fimbriata in China. Plant Pathology 57: 780–780. [Google Scholar]

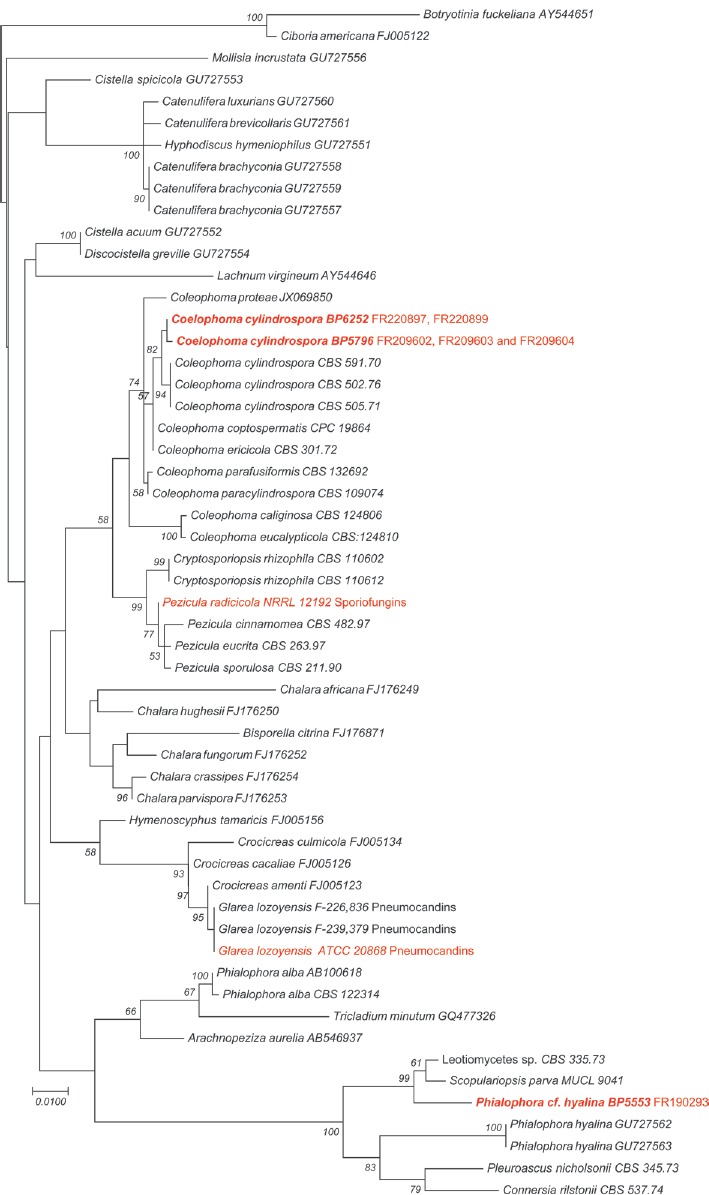

- Iwamoto T, Fujie A, Nitta K, Hashimoto S, Okuhara M, et al. (1994a) WF11899A, B and C, novel antifungal lipopeptides – II. Biological properties. Journal of Antibiotics 47: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto T, Fujie A, Sakamoto K, Tsurumi Y, Shigematsu N, et al. (1994b) WF11899A, B and C, novel antifungal lipopeptides - I. taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and physico-chemical properties. Journal of Antibiotics 47: 1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H, Lee S, Choi GJ, Lee T, Yun S-H. (2013) Draft genome sequence of Fusarium fujikuroi B14, the causal agent of the bakanae disease of rice. Genome Announcements 1: e00035–00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. (1916) Host plants of Thielavia basicola. Journal of Agricultural Research 7: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JA, Harrington TC, Engelbrecht CJB. (2005) Phylogeny and taxonomy of the North American clade of the Ceratocystis fimbriata complex. Mycologia 97: 1067–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juzwik J, Park J-H, Haugen L. (2010) Hickory decline and mortality: update on hickory decline research. In: Iowa’s Forest Health Report 2010 (Feeley T, ed.): 53–58. Des Moines, IA. [Google Scholar]

- Kanasaki R, Abe F, Kobayashi M, Katsuoka M, Hashimoto M, et al. (2006) FR220897 and FR220899, Novel antifungal lipopeptides from Coleophoma empetri No. 14573. Journal of Antibiotics 59: 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal HK, Acharya K, Ramesh G, Reddy MS. (2011) Molecular characterization of Morchella species from the Western Himalayan region of India. Current Microbiology 62: 1245–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Asimenos G, Toh H. (2009) Multiple alignment of DNA sequences with MAFFT. Methods in Molecular Biology 537: 39–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley D. (2013) MAFFT multiple seqeunce alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usablility. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-–Havas S, Cheung M, et al. (2012) Geneious Basic: a integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller O, Kollmar M, Stanke M, Waack S. (2011) A novel hybrid gene prediction method employing protein multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 27: 757–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf I. (2004) Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. (2016) MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution 33: 1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M, Dewsbury DR, O’Donnell K, Carter MC, Rehner SA, et al (2012) Taxonomic revision of true morels (Morchella) in Canada and the United States. Mycologia 104: 1159–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal B, Gund VG, Bhise NB, Gangopadhyay AK. (2004) Mannich reaction: an approach for the synthesis of water soluble mulundocandin analogues. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry 12: 1751–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal B, Gund VG, Gangopadhyay AK, Nadkarni SR, Dikshit DK, et al. (2003) Semisynthetic modifications of hemiaminal function at ornithine unit of mulundocandin, towards chemical stability and antifungal activity. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry 11: 5189–5198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D-H, Roux J, Wingfield BD, Barnes I, Mostert L, et al. (2016) The genetic landscape of Ceratocystis albifundus populations in South Africa reveals a recent fungal introduction event. Fungal Biology 120: 690–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Lee HS, Kim SH, Moon B, Lee C. (2014) Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of methanol extracts of Tremella fuciformis and its major phenolic acids. Journal of Food Science 79: C460–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Harrington TC, McNew D, Li J, Huang Q, et al. (2016) Genetic bottlenecks for two populations of Ceratocystis fimbriata on sweet potato and pomegranate in China. Plant Disease 100: 2266–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Ma H, Zhang Y, Dong C. (2018) Artificial cultivation of true morels: current state, issues and perspectives. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 38:259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma LJ, Geiser DM, Proctor RH, Rooney AP, O’Donnell K, et al. (2013) Fusarium pathogenomics. Annual Review of Microbiology 67: 399–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marçais G, Kingsford C. (2011) A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27: 764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaphy S. (2010) Biotechnology of morel mushrooms: successful fruiting body formation and development in a soilless system. Biotechnology Letters 32: 1523–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molano EPL, Cabrera OG, Jose J, do Nascimento LC, Carazzolle MF, et al. (2018) Ceratocystis cacaofunesta genome analysis reveals a large expansion of extracellular phosphatidylinositol–specific phospholipase–C genes (PI–PLC). BMC Genomics 19: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondo SJ, Dannebaum RO, Kuo RC, Louie KB, Bewick AJ, et al. (2017) Widespread adenine N6–methylation of active genes in fungi. Nature Genetics 49: 964–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay T, Ganguli BN, Fehlhaber HW, Kogler H, Vertesy L. (1987) Mulundocandin, a new lipopeptide antibiotic. II. Structure elucidation. Journal of Antibiotics 40: 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay T, Roy K, Bhat RG, Sawant SN, Blumbach J, et al. (1992) Deoxymulundocandin – A new echinocandin type antifungal antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics 45: 618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehl DB, Allen SJ, Mondal AH, Lonergan PA. (2004) Black root rot: a pandemic in Australian cotton. Australasian Plant Pathology 33: 87–95. [Google Scholar]

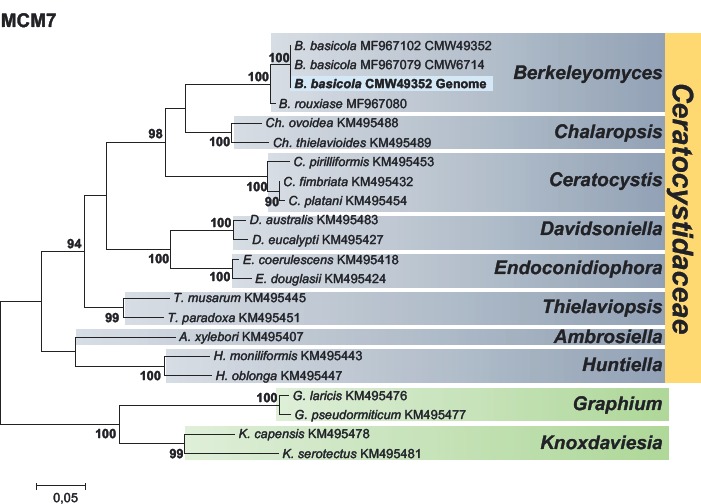

- Nel WJ, Duong TA, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD, De Beer ZW. (2017) A new genus and species for the globally important, multi–host root pathogen Thielaviopsis basicola. Plant Pathology: DOI 10.1111/ppa.12803. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PE, Toussoun TA, Marasas WFO. (1983) Fusarium Species: an illustrated manual for identification. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus E-M, Münsterkötter M, Proctor RH, Brown DW, Sharon A, et al. (2016) Comparative “omics” of the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex highlights differences in genetic potential and metabolite synthesis. Genome Biology and Evolution 8: 3574–3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Nirenberg HI, Aoki T, Cigelnik E. (2000) A multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 41: 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Juzwik J, Cavender-Bares J. (2013) Multiple Ceratocystis smalleyi infections associated with reduced stem water transport in bitternut hickory. Phytopathology 103: 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Juzwik J, Haugen LM. (2010) Ceratocystis canker of bitternut hickory caused by Ceratocystis smalleyi in the north–central and northeastern United States. Plant Disease 94: 277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereg LL. (2013) Black root rot of cotton in Australia: the host, the pathogen and disease management. Crop and Pasture Science 64: 1112–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Pethybridge SJ, Vaghefi N, Kikkert JR. (2017) Management of Cercospora leaf spot in conventional and organic table beet production. Plant Disease 101: 1642–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfab R, Haberl B, Kleber J, Zilker T. (2008) Cerebellar effects after consumption of edible morels (Morchella conica, Morchella esculenta). Clinical Toxicology 46: 259–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pildain MB, Visnovsky SB, Barroetavena C. (2014) Phylogenetic diversity of true morels (Morchella), the main edible non-timber product from native Patagonian forests of Argentina. Fungal Biology 118: 755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piveta G, Ferreira MA, Fb Muniz M, Valdetaro D, Valdebenito–Sanhueza R, et al. (2016) Ceratocystis fimbriata on kiwi fruit (Actinidia spp.) in Brazil. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science 44: 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Polashock JJ, Caruso FL, Oudemans PV, McManus PS, Crouch JA. (2009) The North American cranberry fruit rot fungal community: a systematic overview using morphological and phylogenetic affinities. Plant Pathology 58: 1116–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Richard F, Bellanger JM, Clowez P, Hansen K, O’Donnell K, et al. (2015) True morels (Morchella, Pezizales) of Europe and North America: evolutionary relationships inferred from multilocus data and a unified taxonomy. Mycologia 107: 359–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, Van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, et al. (2012) MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology 61: 539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotzoll N, Dunkel A, Hofmann T. (2006) Quantitative studies, taste reconstitution, and omission experiments on the key taste compounds in morel mushrooms (Morchella deliciosa Fr.). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 54: 2705–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux J, van Wyk M, Hatting H, Wingfield MJ. (2004) Ceratocystis species infecting stem wounds on Eucalyptus grandis in South Africa. Plant Pathology 53: 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- Roy K, Mukhopadhyay T, Reddy GCS, Desikan KR, Ganguli BN. 1987. Mulundocandin, a new lipopeptide antibiotic. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and characterization. Journal of Antibiotics 40: 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert KA, De Beer ZW, Wingfield MJ. (2013) The Ophiostomatoid Fungi: expanding frontiers. [CBS Biodiversity Series no. 12.] Utrecht: CBS–KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Shameem N, Kamili AN, Ahmad M, Masoodi FA, Parray JA. (2017) Antimicrobial activity of crude fractions and morel compounds from wild edible mushrooms of North western Himalaya. Microbial Pathogenesis 105: 356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31: 3210–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJ, et al. (2009) ABySS: A parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Research 19: 1117–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater GS, Birney E. (2005) Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somasekhara YM. (1999) New record of Ceratocystis fimbriata causing wilt of pomegranate in India. Plant Disease 83: 400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamets P. (2000) Growth parameters for gourmet and medicinal mushroom species. In: Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms (Stamets P, ed.): 402–405. 3rd edn. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M, Diekhans M, Baertsch R, Haussler D. (2008) Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24: 637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M, Steinkamp R, Waack S, Morgenstern B. (2004) AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene finding in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Research 32: W309–W312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover RH. (1950) The black rootrot disease of tobacco: I. Studies on the causal organism Thielaviopsis basicola. Canadian Journal of Research 28: 445–470. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton BC. (1980) The Coelomycetes: fungi imperfecti with pycnidia, acervuli and stromata. Kew: Commonwealth Mycological Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. (2013) MEGA 6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter–Hovhannisyan V, Lomsadze A, Chernoff YO, Borodovsky M. (2008) Gene prediction in novel fungal genomes using an ab initio algorithm with unsupervised training. Genome Research 18: 1979–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietel Z, Masaphy S. (2017) True morels (Morchella) – nutritional and phytochemical composition, health benefits and flavor: a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition: DOI:10.1080/10408398.2017.1285269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietel Z, Masaphy S. (2018) Aroma–volatile profile of black morel (Morchella importuna) grown in Israel. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 98: 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaghefi N, Hay FS, Kikkert JR, Pethybridge SJ. (2016) Genotypic diversity and resistance to azoxystrobin of Cercospora beticola on processing table beet in New York. Plant Disease 100: 1466–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaghefi N, Kikkert JR, Bolton MD, Hanson LE, Secor GA, et al. (2017a) De novo genome assembly of Cercospora beticola for microsatellite marker development and validation. Fungal Ecology 26: 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghefi N, Kikkert JR, Bolton MD, Hanson LE, Secor GA, et al. (2017b) Global genotype flow in Cercospora beticola populations confirmed through genotyping–by–sequencing. PloS One 12: 0186488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Nest MA, Beirn LA, Crouch JA, Demers JE, De Beer ZW, et al. (2014a) IMA Genome-F 3: Draft genomes of Amanita jacksonii, Ceratocystis albifundus, Fusarium circinatum, Huntiella omanensis, Leptographium procerum, Rutstroemia sydowiana, and Sclerotinia echinophila. IMA Fungus 5: 472–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Nest MA, Bihon W, De Vos L, Naidoo K, Roodt D, et al. (2014b) IMA Genome-F 2: Draft genome sequences of Diplodia sapinea, Ceratocystis manginecans, and Ceratocystis moniliformis. IMA Fungus 5: 135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Nest MA, Steenkamp ET, McTaggart AR, Trollip C, Godlonton T, et al. (2015) Saprophytic and pathogenic fungi in the Ceratocystidaceae differ in their ability to metabolize plant–derived sucrose. BMC Evolutionary Biology 15: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk M, Roux J, Nkuekam GK, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. (2012) Ceratocystis eucalypticola sp. nov. from Eucalyptus in South Africa and comparison to global isolates from this tree. IMA Fungus 3: 45–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk M, Wingfield BD, Clegg PA, Wingfield MJ. (2009) Ceratocystis larium sp nov., a new species from Styrax benzoin wounds associated with incense harvesting in Indonesia. Persoonia 22: 75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderpool D, Bracewell RR, McCutcheon JP. (2017) Know your farmer: Ancient origins and multiple independent domestications of ambrosia beetle fungal cultivars. Molecular Ecology: DOI:10.1111/mec.14394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira V, Fernandes A, Barros L, Glamoclija J, Ciric A, et al. (2016) Wild Morchella conica Pers. from different origins: a comparative study of nutritional and bioactive properties. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 96: 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouselliel A, et al. (2014) Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 9: e112963.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, et al. (2015) AntiSMASH 3.0–a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Research 43: W237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisenfeld NI, Yin S, Sharpe T, Lau B, Hegarty R, et al. (2014) Comprehensive variation discovery in single human genomes. Nature Genetics 46: 1350–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemann P, Sieber CMK, Von Bargen KW, Studt L, Niehaus E–M, et al. (2013) Deciphering the cryptic genome: genome–wide analyses of the rice pathogen Fusarium fujikuroi reveal complex regulation of secondary metabolism and novel metabolites. PLOS Pathogens 9: e1003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilken PM, Steenkamp ET, De Beer ZW, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD. (2013) IMA Genome-F1: Draft nuclear genome sequence for the plant pathogen, Ceratocystis fimbriata. IMA Fungus 4: 357–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilken PM, Steenkamp ET, Van der Nest MA, Wingfield MJ, De Beer ZW, et al. (2018) Unexpected placement of the MAT1–1–2 gene in the MAT1–2 idiomorph of Thielaviopsis. Fungal Genetics and Biology 113: 32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield BD, Ades PK, Al-Naemi FA, Beirn LA, Bihon W, et al. (2015a) IMA Genome-F4. Draft genome sequences of Chrysoporthe austroafricana, Diplodia scrobiculata, Fusarium nygamai, Leptographium lundbergii, Limonomyces culmigenus, Stagonosporopsis tanaceti, and Thielaviopsis punctulata. IMA Fungus 6: 233–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield BD, Ambler JM, Coetzee M, De Beer ZW, Duong TA, et al. (2016a) IMA Genome–F 6: Draft genome sequences of Armillaria fuscipes, Ceratocystiopsis minuta, Ceratocystis adiposa, Endoconidiophora laricicola, E. polonica and Penicillium freii DAOMC 242723. IMA Fungus 7: 217–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield BD, Barnes I, De Beer ZW, De Vos L, Duong TA, et al. (2015b) IMA Genome-F5: Draft genome sequences of Ceratocystis eucalypticola, Chrysoporthe cubensis, C. deuterocubensis, Davidsoniella virescens, Fusarium temperatum, Graphilbum fragrans, Penicillium nordicum, and Thielaviopsis musarum. IMA Fungus 6: 493–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield BD, Berger DK, Steenkamp ET, Lim H, Duong TA, et al. (2017) Draft genome of Cercospora zeina, Fusarium pininemorale, Hawksworthiomyces lignivorus, Huntiella decipiens and Ophiostoma ips. IMA Fungus 8: 385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield BD, Duong TA, Hammerbacher A, van der Nest MA, Wilson A, et al. (2016b) IMA Genome-F7, Draft genome sequences for Ceratocystis fagacearum, C. harringtonii, Grosmannia penicillata, and Huntiella bhutanensis. IMA Fungus 7: 317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield BD, Steenkamp ET, Santana QC, Coetzee MPA, Bam S, et al. (2012) First fungal genome sequence from Africa: a preliminary analysis. South African Journal of Science 108: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield MJ, Hammerbacher A, Ganley RJ, Steenkamp ET, Gordon TR, et al. (2008) Pitch canker caused by Fusarium circinatum – a growing threat to pine plantations and forests worldwide. Australasian Plant Pathology 37: 319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Davis RW, Tran-Gyamfi MB, Kuo A, LaButti K, et al (2017) Characterization of four endophytic fungi as potential consolidated bioprocessing hosts for conversion of lignocellulose into advanced biofuels. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 101: 2603–2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Sutton BC, Gange AC. (1996) Coleophoma fusiformis sp. nov. from leaves of Rhododendron, with notes on the genus Coleophoma. Mycological Research 100: 943–947. [Google Scholar]

- Xu JR, Yan K, Dickman MB, Leslie JF. (1995) Electrophoretic karyotypes distinguish the biological species of Gibberella fujikuroi (Fusarium section Liseola). Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 9: 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Mao X, Yang JC, Chen X, Mao F, et al (2012) dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate–active enzyme annotation, Nucleic Acids Research 40: W445–W451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Q, Chen L, Zhang X, Li K, Sun J, Liu X, An Z, Bills GF. (2015) Evolution of chemical diversity in echinocandin lipopeptide antifungal metabolites. Eukaryotic Cell 14: 698–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Q, Li Y, Chen L, Zhang X, Liu X, An Z, Bills GF. (2018) Genomics–driven discovery of a novel self–resistance mechanism in the echinocandin–producing fungus Pezicula radicicola. Environmental Microbiology: in press: DOI.org/10.1111/1462–2920.14089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. (2008) Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Research 18: 821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]