Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) in older people is a relatively common, yet hard to treat problem. In this study, we aimed to establish if a single nucleotide polymorphism in the 5-HT1A receptor gene (rs6295) determines antidepressant response in patients aged > 80 years (the oldest old) with MDD.

Nineteen patients aged at least 80 years with a new diagnosis of MDD were monitored for response to citalopram 20 mg daily over 4 weeks and genotyped for the rs6295 allele. Both a frequentist and Bayesian analysis was performed on the data. Bayesian analysis answered the clinically relevant question: ‘What is the probability that an older patient would enter remission after commencing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment, conditional on their rs6295 genotype?’

Individuals with a CC (cytosine–cytosine) genotype showed a significant improvement in their Geriatric Depression Score (p = 0.020) and cognition (p = 0.035) compared with other genotypes. From a Bayesian perspective, we updated reports of antidepressant efficacy in older people with our data and calculated that the 4-week relative risk of entering remission, given a CC genotype, is 1.9 [95% highest-density interval (HDI) 0.7–3.5], compared with 0.52 (95% HDI 0.1–1.0) for the CG (cytosine–guanine) genotype. The sample size of n = 19 is too small to draw any firm conclusions, however, the data suggest a trend indicative of a relationship between the rs6295 genotype and response to citalopram in older patients, which requires further investigation.

Keywords: ageing, Bayesian analysis, depression, pharmacogenomics

Introduction

Approximately 1–4% of older adults living at home, and between 8–24% of older hospitalized inpatients are diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD),1 a condition characterized by either depressed mood, or diminished interest or pleasure.2 Several factors, perhaps in combination, appear to contribute to the risk of developing the disorder in the elderly. For example, previous episodes of depression, age-related neurocognitive changes, comorbidities, and the general circumstances of old age (e.g. social isolation) may interact with each other to precipitate an episode of MDD. The symptoms of depression in later life are themselves associated with increased mortality and poor cardiovascular health.3 This is a major concern for health services around the world, as the absolute numbers of older patients with MDD are set to increase as the population ages. The need for safe, effective therapeutic interventions in this age-group is therefore of critical importance.

The first-line pharmacological treatment for depression in adults and those >65 years are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The rationale for using these agents is based on the serotonin hypothesis of depression first proposed by Schildkraut in 1965.4 The model has been refined in the subsequent decades but the central tenet remains that serotoninergic signalling is disrupted in the terminals of neurones projecting from the Raphé in patients suffering MDD. A disruption to serotonergic signalling is supported by the effectiveness of SSRIs, and other antidepressants whose mode of action is through altering synaptic 5-HT levels. Nonetheless, a proportion of patients with depression, especially those over 65 years, appear to show less response to SSRIs (around 32–44% of older patients will reach remission on an SSRI).5,6 Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain why SSRIs lack therapeutic efficacy in some patients with MDD. These include interindividual differences in the pharmacokinetic profile of SSRIs, and disease aetiology. However, a major focus of research over the past 15 years has been on pharmacogenetic variation in genes which code for proteins involved in 5-HT signalling.

One key target of serotonergic signalling of interest is the 5-HT1A receptor. These receptors are coupled to inhibitory G-proteins located both postsynaptically in the corticolimbic regions of the brain, and presynaptically, as somatodendritic autoreceptors. Their role as autoreceptors is thought to explain the 2–3-week delay in therapeutic response to SSRIs. As SSRI therapy is commenced, the increase in synaptic 5-HT concentration stimulates 5-HT1A receptors which then signal a reduction in 5-HT vesicular release, dampening any therapeutic response. After 2–3 weeks, however, 5-HT1A receptors desensitize, through a combination of internalization and reduced expression, allowing the therapeutic activity of SSRIs to re-emerge. However, recent studies suggest that in a small proportion of patients, response to SSRIs may be more immediate and related to a specific pharmacogenetic trait.7

Because of the important role 5-HT1A receptors play in 5-HT signalling, it was thought that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene for this receptor may determine, at least in part, an individual’s susceptibility to SSRIs. For example, a functional polymorphism that increases activity or expression of the receptor may reduce treatment efficacy. Over 11 clinical trials have been conducted that have investigated the association between a common polymorphism in the promotor region of the 5-HT1A receptor gene (rs6295) that results in increased receptor expression and treatment response.8 However, a meta-analysis that included the majority of these trials found no overall effect of the SNP on treatment response.9 Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that in all of the trials included in the meta-analysis, only young or middle-aged adults were recruited (the mean age of participants ranged from 37- to 51-years old). This is potentially important, as recent evidence suggests that the expression of presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors decline with age.10 Therefore, in older people, the effect of the rs6295 SNP on SSRI treatment response may become more obvious, and therefore clinically relevant. For example, homozygote cytosine–cytosine (CC) individuals, whose basal 5-HT1A expression is not upregulated, will see a decline in expression during ageing, potentially leading to a more rapid SSRI response. Other genotypes may not see this increased response due to their increased burden of receptors. This hypothesis is supported by data showing that the rs6295 SNP influences response in adult patients that are treated with a partial agonist of the 5-HT1A receptor (stimulating desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors).11

Furthermore, this decline in 5-HT1A receptor expression, coupled with the well-reported age-related decline in SERT (a serotonin transporter),12 may also lead to increased serotonergic side effects, particularly in the CC genotype. To explore this further, we conducted a clinical trial to answer the question of whether the rs6295 SNP alters response to SSRI treatment (citalopram 20 mg once daily) in hospitalized patients aged >80 years old (i.e. the oldest old), who have a first diagnosis of depression on admission to hospital.

We employed both a frequentist approach to answer this question, comparing mean and variance values statistically, and also a Bayesian approach, which is of increasing interest in medicine.13,14 In this paper, we aim to demonstrate that both analytical methods are valid approaches in pharmacogenetic trials, but that the use of Bayesian forecasting is of particular value, as it (a) unambiguously addresses the relevant clinical question at hand: is a patient more likely to enter remission following 4 weeks of SSRI treatment, than not, given knowledge of their rs6295 genotype; (b) allows future studies to add their data to ours to calculate ever-more accurate relative risk values; and (c) allows a meaningful analysis of data from relatively small cohorts.

Methods

Patients and recruitment

Study recruitment took place between January 2010 and January 2013 at Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, UK. To be eligible for participation in the study, participants had to meet the following inclusion/exclusion criteria and provide written informed consent:

Inclusion criteria: ⩾80-years old and admitted as an inpatient under the care of the elderly team; have a new clinical diagnosis of depression on admission or during inpatient stay that required treatment with the local hospital formulary SSRI of choice, citalopram 20 mg once daily.

Exclusion criteria: a current prescription for an antidepressant regardless of indication; patients lacking capacity, as determined by a score of ⩽7/10 on a routine Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) conducted on admission.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was granted by both NHS Research Ethics Committee South-East Coast, Brighton Sussex Research Ethics Committee Reference 09/H1107/116 and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatatory Agency, alongside the University of Brighton Research Ethics Committees. The study is listed on the EU Clinical Trials Register [EudraCT number 2009-016716-20]. All experiemental procedures were conducted in accordance with Human Tissue Authority and Good Medical Practice regulations and guidelines.

Measurement of depression and clinical status

A full clinical and biochemical assessment took place at baseline, 1 week, and 4 weeks after starting SSRI treatment to determine the efficacy, tolerability and safety of citalopram therapy. The duration of 4 weeks was chosen as the temporal endpoint, as current UK guidelines suggest that if no repsonse is observed at this point, an increase in dose or switch to an alternative medication is required. Measurements included: the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; 30/30 long form); Mini Mental State Examination Score (MMSE); Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria (HSTC); urea and electrolytes, and full blood count. Remission was defined as a GDS score of ⩽11 at week 4 of the study.15

Assessment of plasma citalopram levels

Plasma citalopram levels were determined at 4 weeks through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Neogen®, Ayr, Scotland, UK).

Assessment of platelet serotonin levels

Serotonin concentrations in platelet pellets were measured using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system which consisted of a Jasco HPLC pump (model: PU-980, Great Dunmow, United Kingdom) and Rheodyne (Schenkon, Switzerland) manual injector equipped with a 20 µl loop. A Kinetic® (Macclesfield, United Kingdom) ODS (octadecylsilyl) 2.6 µm 150 mm × 4.6 mm i.d. (internal diameter) analytical column with a guard column (Phenomenex®, Macclesfield, UK) was employed. The HPLC system was run at a flow rate of 100 µl/min. A CHI630B potentiostat (CH Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) was used to control the detector voltage and record the current. A 3 mm glassy carbon electrode (flow cell, BASi®, West Lafayette, IN, USA) served as the working electrode and was used with a silver|silver chloride (Ag|AgCl) reference electrode and a stainless steel block as the auxiliary electrode. Amperometric recordings were carried out, where the working electrode was set at a potential of +950 mV versus Ag|AgCl reference electrode. Control and data collection/processing were handled through the CHI630B software. Briefly, 500 µl of ice cold 0.1 mol/l perchloric acid was added to the platelet pellet and samples were sonicated and vortexed for 2 min and then centrifuged at 14,600g for 10 min prior to chromatographic analysis. The supernatant was removed and filtered through a 0.2 µm filter and the resulting solution analysed using HPLC with electrochemical detection.

Characterization of 5-HT1A polymorphisms

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from 200 µl of whole blood using DNA extraction columns (DNeasy Blood and Tissue Mini-kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The 5-HT1A receptor gene promotor has an SNP, rs6295, at position −1019C/G, which was typed by amplification using the following primers: forward 5’ TGTCGT-CGTTGTTCGTTTGT 3’ and reverse 5’ GGT-GAACAGTCCTGGGTCAG 3’.16 Amplifications were carried out in 25 µl reactions containing approximately 5 ng of DNA template and final concentrations of 15 nmol/l 10× reaction buffer, 1.5 mmol/l MgCl2 (magnesium chloride), 0.2 mmol/l for each deoxynucleotide (dNTP), 10 pmol/l forward and reverse primers, 1 unit Platinum®Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany). Cycling was performed in a Techne TC-4000 (Cambridge, United Kingdom) thermal cycler employing 40 cycles (30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C and 60 s at 72°C), with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Sequencing (Sanger sequencing) procedures were performed by Source-Bioscience (Nottingham, England) to determine the nucleotide at position −1019.

Frequentist analysis

Chi-square tests were performed to determine the significance of any allele/genotype associations with the incidence of serotonergic side effects or the efficacy of citalopram therapy (remission, defined as a GDS score of ⩽11 at week 4). General linear regression models were fitted to estimate the relative influence of demographics and genotypes on variation in response to treatment with citalopram, and the incidence of side effects. A one-way analysis of variance with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test was used to assess statistical significance of differences in the effects of citalopram according to genotype. Effect size η2 was calculated as the sum of squares between groups/total sum of squares. To assess the statistical significance of differences in platelet [5-HT], MMSE, and GDS over time, either a repeated-measures one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Friedman test was used according to the distribution profile of the data. Normality of data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, where we accepted the null hypothesis that the data were normally distributed if p > 0.05. Data analysis and graphical representation were performed in R (R Core Team)17 and GraphPad Prism v6, Graphpad software, California, USA. Statistical significance was assumed if p < 0.05. Mean ± standard error of the mean are presented unless otherwise stated.

Bayesian forecasting

Following the method outlined in Mould and colleagues’ work,18 we framed our research question in the following way: what is the conditional probability that individuals will not present in remission at week 4, that is, a GDS of ⩽11, given they are known to have a specific genotype and that they have embarked on a course of citalopram? (The details of this approach can be found in the supplementary material.)

We took the odds form of Bayes’ rule: the probability of not being in remission at week 4, relative to being in remission. The appropriate prior probability distribution to employ with a likelihood that takes this form is a beta distribution.19 This distribution has two parameters, the values of which can be drawn from previously observed data relating to the unconditional probability that an older individual will go into remission following a course of citalopram. For example, the combined remission rates in six studies that investigated the use of citalopram in late-life depression is calculated at around 47% (n = 567).20 In this scenario, the distribution is broadly described as symmetrically bell shaped around a mean of 0.5 (corresponding to a probability of remission of 0.5). For comparison, we also considered the more conservative position that all possibilities for the probability of not responding to citalopram are equally likely, which is a specific case of the beta distribution and defines a non-informative uniform distribution.

To obtain the posterior distribution of the relative risk of not being in remission at week 4 relative to being in remission, conditional on the genotype, we applied Gibbs sampling in order to sample from the two distributions without having to explicitly calculate the integrals. This was performed in R (R 3.2.2) using the script employed in ‘OPTIMISE trial in a Bayesian framework’,21 which incorporates the scripts ‘openGraphSaveGraph.R’ and ‘plotPost.R’.19

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Baseline demographics

A total of 29 patients were enrolled into the study over a 3-year period. Recruitment was more difficult than expected due to the population being acutely unwell. Ten patients missed either the final, or both follow-up visits and were therefore excluded from the analysis. The mean age of the study group was 88 ± 4 years and the mean baseline GDS for the 19 patients remaining in the study was 15/30 ± 5. The genotype frequencies of the 5-HT1A receptor was found to be 7:6:6 for CC, GC and GG respectively. By comparing the observed genotype frequencies with the expected frequencies (5:9:4 for CC, GC and GG respectively), we were able to confirm that our sample population does not deviate, by any large extent, from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (χ2 = 2.55; p = 0.53, β-1 = 0.59). A summary of the baseline demographics is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of study recruitments.

| Baseline characteristics (n = 19) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 88.16 (±3.8) |

| Sex (male:female) | 5:14 |

| Genotype (CC:GC:GG) | 7:6:6 |

| CrCl (ml/min) | 41.01 (±30.8) |

| Weight (kg) | 64.32 (±13.1) |

| Baseline MMSE | 27 (±2) |

| Baseline GDS | 15 (±5) |

| Hb (g/dl) | 11.97 (±2.0) |

| WCC (×109/l) | 9.91 (±4.7) |

| Plt (×109/l) | 267.16 (±91.4) |

| Na+ (mmol/l) | 138 (±6.0) |

| K+ (mmol/l) | 3.9 (±0.6) |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 9.2 (±3.6) |

| Ethnicity | White British 17 Mixed White and Black African 2 |

Values represent mean ± standard deviation (with the exception of sex and genotype).

C, cytosine; CrCl, creatinine clearance; G, guanine; Hb, haemoglobin; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination Score; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; WCC, white cell count; Plt, platelet count; Na+, sodium; K+, potassium.

Response to citalopram

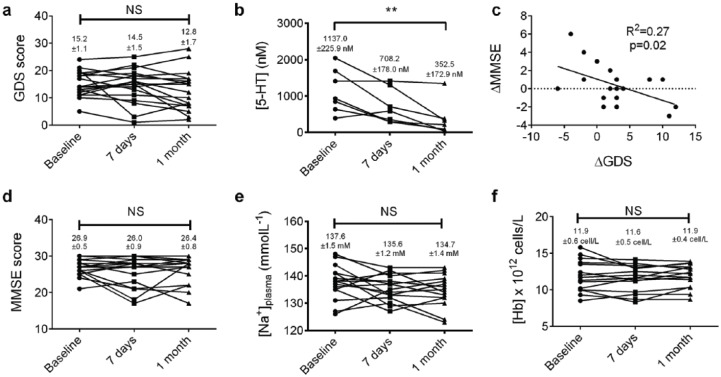

To measure the therapeutic effect of citalopram we compared GDS at baseline, 7 days and 4 weeks for all the patients. There was a trend towards a reduction in GDS over the 4 weeks of the study, although this was not found to be statistically significant (p = 0.11, repeated measures one-way ANOVA, n = 18 [1 patient did not attend the day 7 visit and so was excluded from this analysis], Figure 1a). A total of 8/19 patients reached remission by week 4 (that is, a GDS score of ⩽11).15 Mean platelet [5-HT] reduced significantly over the duration of the study, indicating the pharmacological activity of citalopram on platelet 5-HT transporters, although we were only able to successfully measure concentrations in 7/19 participants (p < 0.001, Friedman test; p < 0.01 between baseline and 1 month, Dunn’s post hoc; n = 7; Figure 1b). Mean [citalopram]plasma was 0.75 ± 0.17 mg/l.

Figure 1.

Effect of citalopram on clinical and psychological measures.

(a) There is small but statistically insignificant reduction in GDS over the 1-month study; (b) platelet [5-HT] shows a significant reduction of the study period (n = 7, p < 0.01, Friedman test); (c) there is significant correlation between the change in GDS during treatment and MMSE, although mean MMSE remains stable over the study period; (d) n = 19, R2 = 0.27, p = 0.02, Pearson’s correlation; (e) and (f) both plasma Na+ and Hb concentrations remained stable over the study period, respectively.

GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; Hb, haemoglobin; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination Score; Na+, sodium.

A clinical improvement in mood has previously been associated with improved cognition in older people.22 We did show a significant correlation between change is GDS (ΔGDS) and change in MMSE (ΔMMSE) over the course of the study (R2 = 0.27, p = 0.02, Pearson’s correlation; Figure 1c), although we were unable to detect a significant change in mean MMSE (p = 0.88, Friedman test, n = 19; Figure 1d) over the three visits.

Treatment with citalopram has been associated with several side effects which could be particularly problematic to older patients. Recognized complications of citalopram therapy include hyponatraemia, and gastrointestinal bleeding as a result of depletion of platelet 5-HT. We found a small, clinically, and statistically insignificant change in plasma Na+ concentration over the duration of the study (mean plasma [Na+] = 137.6 ± 1.5 versus 135.6 ± 1.2 versus 134.7 ± 1.4 mmol/l at baseline, 1 week and 4 weeks, respectively; p = 0.10, repeated measures one-way ANOVA, n = 16, Figure 1e). Plasma Hb concentration, which may fall due to gastrointestinal bleeding as a consequence of SSRI treatment did not change significantly over the course of the study (Figure 1f). Another rare, but serious reaction to SSRIs is serotonin syndrome. Using the Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria, one of our 19 patients was identified as positive for serotonin syndrome over the 4-week period.

Factors that determine response to citalopram

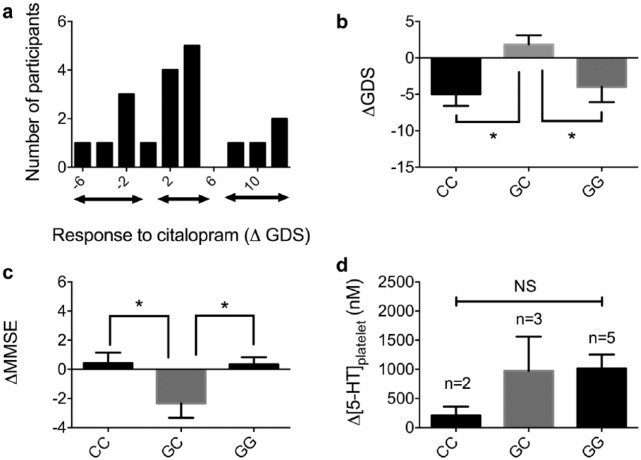

Despite the overall small decrease in mean GDS score over time, it is clear from the individual data that some patients responded well to citalopram, whilst others showed a continued deterioration in mood (Figure 2a). To explore this further, we constructed a generalized linear model to determine whether certain baseline characteristics could predict response to citalopram (i.e. absolute change in 4-week GDS). We chose a generalized linear model due to the multinomial distribution of the data. The first iteration of the model included four predictor variables (5-HT1A genotype, sex, age, and weight). We did not include ethnicity as a variable due to only two of our sample being nonwhite. In further iterations of the model, predictably, given the small sample size, individual variables that did not reach statistical significance were excluded until a minimum effective model was produced.23 The final model contained only 5-HT1A genotype as a statistically significant predictor variable, explaining 32% of the deviance in GDS score (p = 0.005).

Figure 2.

The relationship between 5-HT1A genotype and response to citalopram.

(a) Histogram demonstrating the distribution of participants’ ΔGDS scores. It appears there are three groups of patients: a group of responders, a group demonstrating no clinical change and a group whose depression score declines; (b) individuals with GC genotype were significantly different to individuals with a CC genotype, in terms of effect on depression score (GDS; n = 19, p = 0.024, one-way ANOVA); (c) individuals with GC genotype showed a significant decrease in cognition over the study period compared with CC and GG genotypes (n = 19, p = 0.035, one-way ANOVA); (d) no statistically significant difference was found between the three genotypes in terms of platelet [5-HT] concentration.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; C, cytosine; G, guanine; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination Score.

The effect of the 5-HT1A genotype on response to citalopram

To probe the role of the 5-HT1A genotype in response to citalopram, we looked at the mean change in GDS over the 4-week study according to the three genotypes (Figure 2b). The mean change in GDS for the CC, GC, and GG genotypes were: –5.0 ± 1.1, 1.8 ± 1.3, –4.0 ± 2.1 (p = 0.02, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD post hoc test; n = 7, 6, 6, respectively). These data show that individuals with the GC genotype demonstrate a significantly different response to citalopram at 4 weeks compared with either CC or GG [although only individuals with a CC genotype are significantly different from 0 (single sample t test, p < 0.05)]. Interestingly, individuals with a GC genotype showed a mean increase in GDS (i.e. worsening of depression), although this is not significantly different from 0. Genotype was found to be associated with the incidence of remission at week 4 (remission/total: CC = 5/7, CG = 0/6, GG = 3/6; χ2 test, p = 0.031).

We also observed a significant reduction in absolute MMSE score in patients with a GC genotype, compared with the CC group (0.4/30 ± 0.7 versus –2.3/30 ± 1.0 versus 0.3/30 ± 0.5; p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Fisher’s LSD post hoc test, Figure 2c). The role of genotype on platelet [5-HT] is inconclusive due to small numbers in each group (Figure 2d). We found no relationship between changes in plasma Na+ and Hb concentrations, or the presence of serotonin syndrome and genotype over the study period (data not shown).

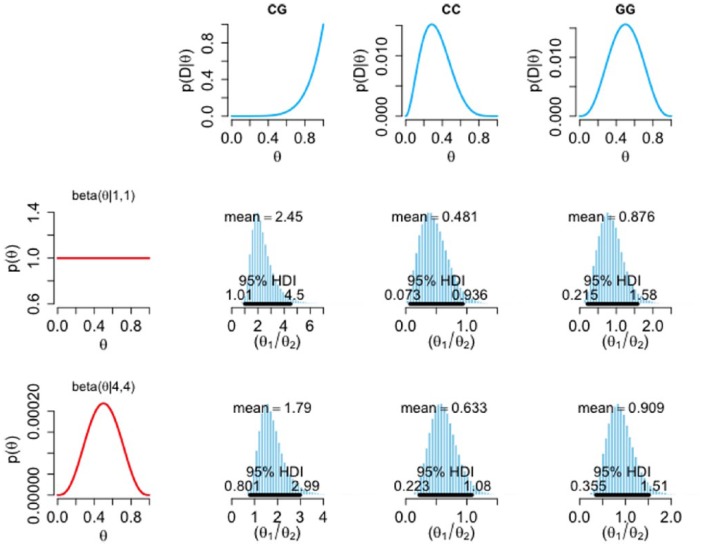

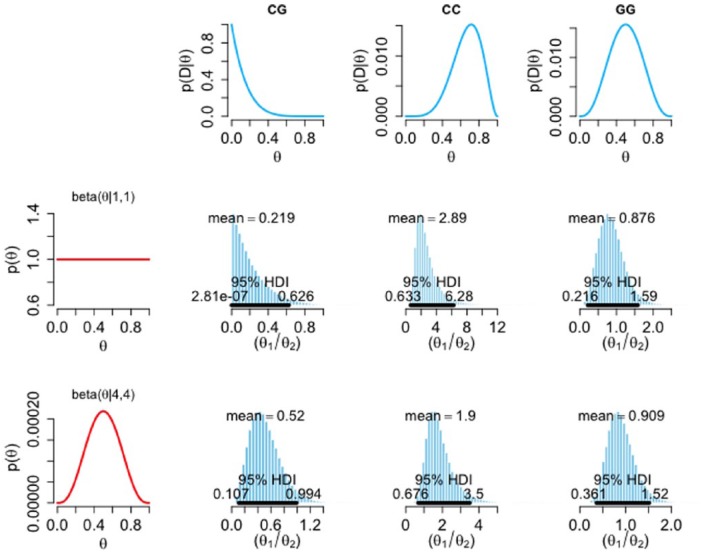

Relative risk of not responding to citalopram, conditional on genotype

The traditional frequentist treatment of our data presented above is indicative of an effect and, being the standard approach, is potentially of value for interstudy comparisons; however, this approach does not explicitly address the question of clinical interest. When making a decision about starting SSRI therapy, it may be more useful for a clinician to know the probability that an individual will respond poorly to citalopram, in the knowledge of their 5-HT1A genotype. Bayesian inference provides a means of addressing the former question, and also determines the probability of our model (i.e. that there is a relationship between rs6295 genotype and response to citalopram). To perform this analysis, we first categorized our participants as either responders or nonresponders; where responders are those who reached remission (GDS score ⩽ 11) at week 4 and nonresponders are those who did not. Figure 3 shows the influence of the prior distributions (first column) on the likelihood of each genotype (first row) in arriving at the posterior relative risk of not responding (θ1) to responding (θ2). When an informative beta prior is considered, an individual that has the CG genotype is, on average, 1.79 times more likely to not remit at 4 weeks than to go into remission. The highest-density interval (HDI) spans between 0.8 and 3; however, the probability that the CG individuals have a higher chance of not remitting than remitting is 99.3% (proportion of the posterior distribution > θ1 / θ2 = 1). Figure 4 shows the relative risk of responding (θ1) to not responding (θ2). In this analysis, when an informative prior is used, an individual that has the CC genotype is, on average, 1.9 times more likely to go into remission at 4 weeks than to not go into remission (Figure 4). The HDI spans between 0.7 and 3.5, where the probability that the CC individuals have a higher chance of going into remission than not is 93.5%.

Figure 3.

Influence of prior and likelihood on posterior relative risk of not-responding to responding to citalopram. The histograms show the posterior relative risk of not responding (θ1), relative to responding (θ2), conditional upon genotype using a non-informative, uniform prior [beta(1,1)], and a prior that corresponds to the literature but with a reasonable degree of uncertainty [beta(4,4)] (first column). The first row gives the likelihoods of the not-responding group for each genotype. Black horizontal bars represent 95% highest-density intervals (95% chance that the true relative risk falls within this interval). Note the variable scale on the x axis.

D, data; HDI, highest-density intervals.

Figure 4.

Influence of prior and likelihood on posterior relative risk of responding to not-responding to citalopram. The histograms show the posterior relative risk of responding (θ1), relative to not responding (θ2), conditional upon genotype using a non-informative, uniform prior (beta(1,1)), and an informative prior [beta(4,4)] (first column). The first row gives the likelihoods of the not-responding group for each genotype. Black horizontal bars represent 95% highest-density intervals (95% chance that the true relative risk falls within this interval). Note the variable scale on the x axis.

D, data; HDI, highest-density intervals.

Discussion

Response to citalopram in the oldest old is related to 5-HT1A receptor genotype

Our study set out to explore an important question relating to the value of 5-HT1A receptor genotypes in predicting response to citalopram in the oldest old. Given the nature of our target population, recruitment was suboptimal and our sample size is likely to be considered too small for any meaningful statistical analysis. In light of this, we wish to emphasize two key points: (a) our data are drawn from a difficult-to-obtain population and are likely to be of value to future studies; and (b) we propose that for studies such as these, a simple Bayesian analysis is more transparent in conveying the influence of the evidence (proportional to the sample size) on any one hypothesis.

The current study has shown that for a population of depressed older patients (aged > 80 years), genotype explains approximately 32% of the variation in response to citalopram. We were able to exclude age, ethnicity and sex as confounders, although we acknowledge that these may have small effects that we were unable to detect with our small sample size. Other factors, which we were unable to control for may also contribute to the observed changes. Interestingly, we showed that both homozygote groups (CC and GG) displayed a mean reduction in GDS over the study period, whilst the heterozygote group’s score increased, indicating a worsening of depression. The calculated effect size for genotype equates to approximately 0.37 (η2), which is considered large. The effect size of genotype on remission rates is also large (Cramer’s V = 0.61), compared with similar studies conducted in younger patients (Cramer’s V = 0.34), which raises the intriguing possibility that the effect of genotype is more prominent in this older population. It should be noted, however, that whilst it appears the results of the GC group reflect an absence of response at 4 weeks, it may equally be the case that the response is delayed. Conducting the study over a longer period could resolve this question, but may prove difficult due to retention issues.

This nonlinear relationship between the addition of a G allele on ΔGDS was not expected, yet this pattern was also observed in our analysis of genotype on MMSE following citalopram treatment (the cognition of homozygotes both improved slightly over the course of the study, whilst the heterozygote group showed a decline). Indeed, post hoc analysis revealed that the GC genotype behaves differently in response to citalopram compared with both homozygotes. Nonetheless, it should be noted that only the CC ΔGDS showed a statistically significant difference from 0 (p < 0.05, one-sample student’s t test). A similar observation was noted by Koto and colleagues, who showed that the rs6295 heterozygote has significantly lower response and remission rates at 2 weeks compared with both homozygotes.24

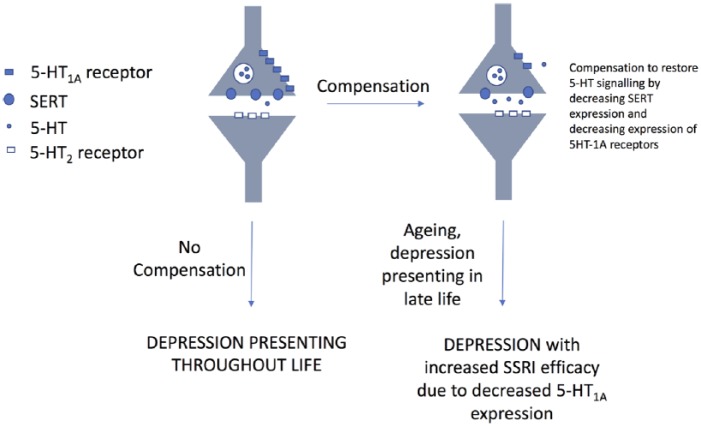

One possible reason for this observation could be an interaction between age and phenotype. Evidence suggests that both 5-HT1A receptor and SERT expression decline with increasing age.10,12 The effect of the latter would be to increase synaptic 5-HT, further reducing 5-HT1A surface expression through desensitization (internalization and transcriptional repression).25 This may perhaps improve SSRI efficacy in CC individuals (as they would be susceptible to Deaf-1 repression), whilst having little effect on those carrying a G allele. Our results were consistent with our hypothesis in terms of CC individuals responding positively to citalopram, and GC individuals not so; but there is an obvious conflict in the positive response observed within our GG group. A possible explanation for this finding is summarized in Figure 5. Briefly, based on previous studies, we speculate that individuals with a GG genotype in the population fall into two categories: those who have a compensatory mechanism that restores 5-HT signalling, and those who do not. Those individuals who do not compensate will be more prone to depression, presenting with symptoms throughout life.26 The idea of a compensatory mechanism in this genotype has been postulated previously and may involve a reduction in the expression of SERT, and a restoration of 5-HT1A expression to levels not dissimilar to other genotypes. It is these individuals that we believe may present late in life with depression, and, due to the downregulation of 5-HT1A receptors may show an uncharacteristic (based on genotype) positive response to SSRI therapy. The situation may be complicated further by the fact that there are recognized sex differences in age-related changes to 5-HT1A expression, with females showing less presynaptic receptor decline with age compared with men.27 This may potentially make aged men more sensitive to SSRIs than females. Indeed, all males in our study (n = 5) showed a reduction in GDS over the course of the study. At this stage, however, we must caution that this interpretation is speculative, but this offers a possible hypothesis that can be tested in future studies.

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanism to explain unexpected positive response of GG individuals to citalopram.

The GG genotype has been postulated to comprise two sets of individuals, those who possess a compensatory mechanism to restore 5-HT signalling, and those who do not. It might be expected that GG individuals without a compensatory mechanism will be prone to depression throughout life and require antidepressant therapy during adulthood. In this study, we propose it is GG individuals who have a compensatory mechanism that present in old age with depression requiring treatment. Due to the downregulation of 5-HT1A receptors, these individuals may be expected to respond well to SSRI therapy.

G, guanine; SERT, the serotonin transporter; SSRI, serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Despite demonstrating a relationship between 5-HT1A genotype and SSRI efficacy in old age, we did not find a role for genotype in susceptibility to common adverse reactions associated with SSRIs. Neither a reduction in plasma Na+ or Hb concentration, or the presence of serotonin syndrome were significantly different between genotype populations, however, this does not necessarily rule out a relationship, as they may take a longer period to manifest than our data collection period allowed, and it may not have been possible to detect them because of our small sample size.

Bayesian analysis

So far in our discussions, we have considered data analysed from a frequentist’s viewpoint and asked the statistical question: what is the probability of observing our data if there were no underlying genotype effects. For data where p < 0.05, it is standard to consider the probability of observing our data by chance to be so small that it is more likely that there are real genotype effects. However, with an n = 19, it would be prudent to exercise some caution in drawing any firm conclusions. Furthermore, when making clinical decisions about which treatment should be initiated in an individual, this type of analysis offers little help. Instead, it may be more useful to ask the following question: what is probability of observing treatment failure in an individual, given a particular genotype? This approach is termed Bayesian forecasting and is arguably of more value to a clinician than frequentist data. Importantly for situations such as ours, the simple Bayesian approach we adopt at least offers a transparent indication of the contribution our evidence offers in support of any one hypothesis.

The Bayesian analysis we performed incorporated data from previous studies investigating response to citalopram in older patients as the prior. Limited as these data are for these difficult-to-obtain samples, our Bayesian forecasting indicates that the CG and CC genotypes may influence response to citalopram in different directions and highlights the need for more studies in this area. Importantly, by adopting the methodology presented here, further studies can readily incorporate our posterior distributions as future priors, thereby fully benefitting from the strength Bayesian analysis brings to studies of this nature.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Scutt_et_al_TADS_Supplementary_material for Does the 5-HT1A rs6295 polymorphism influence the safety and efficacy of citalopram therapy in the oldest old? by Greg Scutt, Andrew Overall, Railton Scott, Bhavik Patel, Lamia Hachoumi, Mark Yeoman and Juliet Wright in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Acknowledgments

JW was the principal investigator of the study. GS contributed to the study conception and design, wrote the manuscript, prepared Figures 1–3 and performed data analysis; AO contributed to the study conception and design, cowrote the manuscript, generated Figures 3 and 4 and performed data analysis; RS contributed to the study conception and design, cowrote the manuscript and performed clinical testing serotonin syndrome, cognition and depression. BP performed experimental and data analysis of platelet serotonin concentrations, prepared Figure 1b, and participated in revising the manuscript; LH performed experimental analysis of platelet serotonin concentrations, and participated in revising the manuscript; MY conceived the study, cowrote the manuscript and performed data analysis and interpretation; JW contributed to the study conception and design, cowrote the manuscript and performed data analysis and interpretation.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research who funded this study through a Research for Patient Benefit grant (PB-PG-0408-16130).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material: Supplementary material is available for this article online.

ORCID iD: Greg Scutt Patra  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7124-7543.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7124-7543.

Contributor Information

Greg Scutt, Brighton and Sussex Centre for Medicines Optimisation, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Brighton, Room 313 Cockcroft Building, Brighton, BN2 4GJ, UK.

Andrew Overall, Centre for Stress and Age Related Diseases, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK.

Railton Scott, Brighton and Sussex Centre for Medicines Optimization, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Brighton and Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, Brighton, UK.

Bhavik Patel, Centre for Stress and Age Related Diseases, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK.

Lamia Hachoumi, Centre for Stress and Age Related Diseases, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK.

Mark Yeoman, Centre for Stress and Age Related Diseases, School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK.

Juliet Wright, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, UK; Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, Brighton, UK.

References

- 1. Age UK. Later Life in the United Kingdom. 2016; 40, London: Age UK. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet 2005; 365: 1961–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schulz R, Beach SR, Ives DG, et al. Association between depression and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 1761–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schildkraut JJ. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. Am J Psychiatry 1965; 122: 509–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tollefson GD, Bosomworth JC, Heiligenstein JH, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of fluoxetine in geriatric patients with major depression. The Fluoxetine Collaborative Study Group. Int Psychogeriatr 1995; 7: 89–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rapaport MH, Schneider LS, Dunner DL, et al. Efficacy of controlled-release paroxetine in the treatment of late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64: 1065–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uher R, Muthén B, Souery D, et al. Trajectories of change in depression severity during treatment with antidepressants. Psychol Med 2010; 40: 1367–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parsey RV, Ogden RT, Miller JM, et al. Higher serotonin 1A binding in a second major depression cohort: modeling and reference region considerations. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 68: 170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao X, Huang Y, Li J, et al. Association between the 5-HT1A receptor gene polymorphism (rs6295) and antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012; 27: 314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dillon KA, Gross-Isseroff R, Israeli M, et al. Autoradiographic analysis of serotonin 5-HT1A receptor binding in the human brain postmortem: effects of age and alcohol. Brain Res 1991; 554: 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lemonde S, Du L, Bakish D, et al. Association of the C(-1019)G 5-HT1A functional promoter polymorphism with antidepressant response. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004; 7: 501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Dyck CH, Malison RT, Seibyl JP, et al. Age-related decline in central serotonin transporter availability with [(123)I]beta-CIT SPECT. Neurobiol Aging 2000; 21: 497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dunson DB. Commentary: practical advantages of Bayesian analysis of epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 153: 1222–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Medow MA, Lucey CR. A qualitative approach to Bayes’ theorem. Evid Based Med 2011; 16: 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jongenelis K, Pot AM, Eisses AM, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the original 30-item and shortened versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale in nursing home patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 20: 1067–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang S, Zhang K, Xu Y, et al. An association study of the serotonin transporter and receptor genes with the suicidal ideation of major depression in a Chinese Han population. Psychiatry Res 2009; 170: 204–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. R Core Team (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mould DR, Dubinsky MC. Dashboard systems: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic mediated dose optimization for monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 55(Suppl. 3): S51–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kruschke JK. Doing Bayesian data analysis: a tutorial with R, JAGS, and Stan. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2015, pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seitz DP, Gill SS, Conn DK. Citalopram versus other antidepressants for late-life depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 25: 1296–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harrison E. in R-Bloggers Vol. 2015 (2015), Available at: https://www.r-bloggers.com/bayesian-statistics-and-clinical-trial-conclusions-why-the-optimse-study-should-be-considered-positive/ (accessed 6 April 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doraiswamy PM, Krishnan KR, Oxman T, et al. Does antidepressant therapy improve cognition in elderly depressed patients? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58: M1137–M1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crawley MJ. GLIM for ecologists. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kato M, Fukuda T, Wakeno M, et al. Effect of 5-HT1A gene polymorphisms on antidepressant response in major depressive disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2009; 150B: 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Albert PR, Francois BL. Modifying 5-HT1A receptor gene expression as a new target for antidepressant therapy. Front Neurosci 2010; 4: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Albert PR. Transcriptional regulation of the 5-HT1A receptor: implications for mental illness. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2012; 367: 2402–2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moses-Kolko EL, Price JC, Shah N, et al. Age, sex, and reproductive hormone effects on brain serotonin-1A and serotonin-2A receptor binding in a healthy population. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011; 36: 2729–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Scutt_et_al_TADS_Supplementary_material for Does the 5-HT1A rs6295 polymorphism influence the safety and efficacy of citalopram therapy in the oldest old? by Greg Scutt, Andrew Overall, Railton Scott, Bhavik Patel, Lamia Hachoumi, Mark Yeoman and Juliet Wright in Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.