Summary

Background

Little evidence is available for head-to-head comparisons of psychosocial interventions and pharmacological interventions in psychosis. We aimed to establish whether a randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus antipsychotic drugs versus a combination of both would be feasible in people with psychosis.

Methods

We did a single-site, single-blind pilot randomised controlled trial in people with psychosis who used services in National Health Service trusts across Greater Manchester, UK. Eligible participants were aged 16 years or older; met ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder, or met the entry criteria for an early intervention for psychosis service; were in contact with mental health services, under the care of a consultant psychiatrist; scored at least 4 on delusions or hallucinations items, or at least 5 on suspiciousness, persecution, or grandiosity items on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS); had capacity to consent; and were help-seeking. Participants were assigned (1:1:1) to antipsychotics, CBT, or antipsychotics plus CBT. Randomisation was done via a secure web-based randomisation system (Sealed Envelope), with randomised permuted blocks of 4 and 6, stratified by gender and first episode status. CBT incorporated up to 26 sessions over 6 months plus up to four booster sessions. Choice and dose of antipsychotic were at the discretion of the treating consultant. Participants were followed up for 1 year. The primary outcome was feasibility (ie, data about recruitment, retention, and acceptability), and the primary efficacy outcome was the PANSS total score (assessed at baseline, 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks). Non-neurological side-effects were assessed systemically with the Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale. Primary analyses were done by intention to treat; safety analyses were done on an as-treated basis. The study was prospectively registered with ISRCTN, number ISRCTN06022197.

Findings

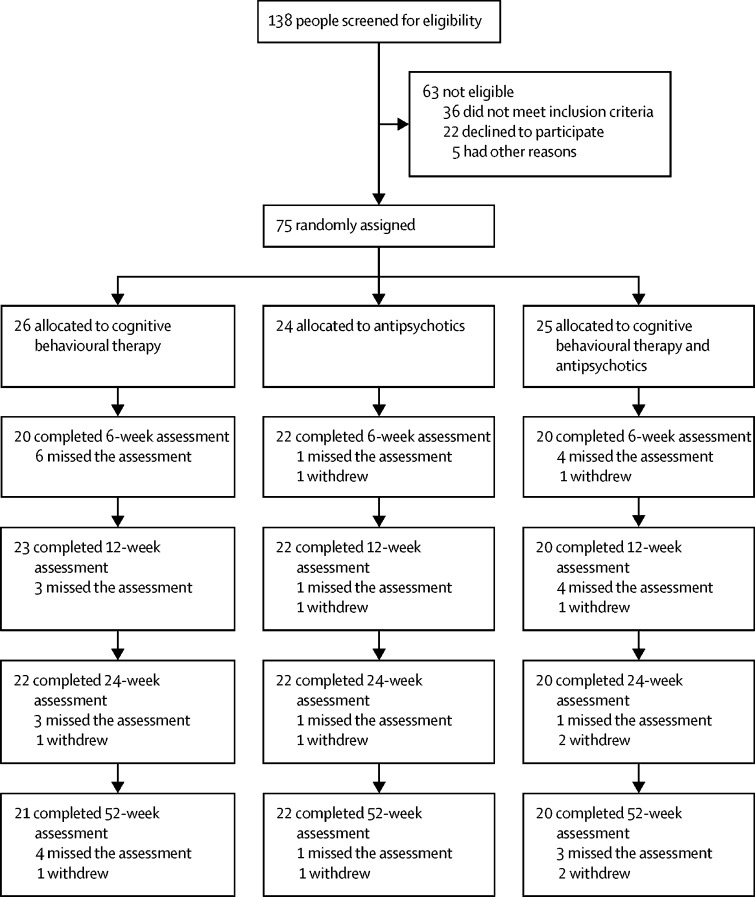

Of 138 patients referred to the study, 75 were recruited and randomly assigned—26 to CBT, 24 to antipsychotics, and 25 to antipsychotics plus CBT. Attrition was low, and retention high, with only four withdrawals across all groups. 40 (78%) of 51 participants allocated to CBT attended six or more sessions. Of the 49 participants randomised to antipsychotics, 11 (22%) were not prescribed a regular antipsychotic. Median duration of total antipsychotic treatment was 44·5 weeks (IQR 26–51). PANSS total score was significantly reduced in the combined intervention group compared with the CBT group (–5·65 [95% CI −10·37 to −0·93]; p=0·019). PANSS total scores did not differ significantly between the combined group and the antipsychotics group (–4·52 [95% CI −9·30 to 0·26]; p=0·064) or between the antipsychotics and CBT groups (–1·13 [95% CI −5·81 to 3·55]; p=0·637). Significantly fewer side-effects, as measured with the Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale, were noted in the CBT group than in the antipsychotics (3·22 [95% CI 0·58 to 5·87]; p=0·017) or antipsychotics plus CBT (3·99 [95% CI 1·36 to 6·64]; p=0·003) groups. Only one serious adverse event was thought to be related to the trial (an overdose of three paracetamol tablets in the CBT group).

Interpretation

A head-to-head clinical trial of CBT versus antipsychotics versus the combination of the two is feasible and safe in people with first-episode psychosis.

Funding

National Institute for Health Research.

Introduction

Schizophrenia and psychosis are associated with substantial personal, social, and economic costs. High-quality evidence from clinical trials shows that both antipsychotics and cognitive behavioural (CBT) therapy can be helpful to adults with diagnoses of schizophrenia or other psychoses.1 Many clinical guidelines, therefore, suggest that people with psychosis should be offered both antipsychotics and CBT (as well as family interventions) and should be involved in collaborative decisions about treatment options.1 However, neither antipsychotics nor CBT are effective for everyone, and the individual cost–benefit ratios of such treatments (ie, the balance between efficacy and adverse effects) vary substantially, both between and within individuals.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed with the terms “schizophrenia”, “psychosis”, “psychological therapy”, “psychosocial intervention”, “CBT”, “antipsychotic” and “neuroleptic” for articles published in any language up to Jan 30, 2018. Although several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown robust evidence that antipsychotics are superior to placebo and that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for psychosis in addition to antipsychotics is superior to treatment as usual, we identified no randomised controlled trials in which a head-to-head comparison of CBT and antipsychotics was done. A 2012 Cochrane review concluded that no usable data were available to establish the relative efficacy of antipsychotic medication and psychosocial interventions in early episode psychosis.

Added value of this study

Our pilot and feasibility trial showed that a methodologically rigorous clinical trial in which participants with psychosis are randomly assigned to psychological treatment or pharmacological treatment, or both, is possible. Our findings suggest that antipsychotics, CBT, and the combination of the two are acceptable, safe, and helpful treatments for people with early psychosis, but could have different cost–benefit profiles.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our preliminary findings seem consistent with guidelines that recommend informed choices and shared decision making about treatment options for early psychosis on the basis of cost–benefit profiles. An adequately powered efficacy and effectiveness trial is now needed to test hypotheses about superiority (eg, antipsychotics plus CBT vs antipsychotics alone or CBT alone) and non-inferiority (eg, antipsychotics vs CBT).

Meta-analyses2, 3, 4 of randomised controlled trials of CBT, added to antipsychotics, for psychosis have shown effect sizes for both total symptoms and positive symptoms in the small-to-moderate range (generally 0·3–0·4 relative to treatment as usual, although the effect size is smaller when lower quality trials are excluded). Meta-analyses5, 6 of antipsychotics compared with placebo also show moderate benefits in terms of total and positive symptoms. The most comprehensive meta-analysis7 in chronic schizophrenia showed a standardised effect size for total symptoms of 0·47 (95% CI 0·42–0·51). Although CBT and antipsychotics are better than comparators (treatment as usual and placebo, respectively), the proportion of individuals who achieve a clinically meaningful benefit is moderate. For example, a meta-analysis7 showed that 51% of multi-episode patients had at least a minimal response (≥20% reduction in symptoms as measured on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] or Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale), and 23% had a good response (≥50% reduction in symptoms), to antipsychotics. By comparison, in first-episode psychosis, 81% of patients had at least a minimal response, and 52% had a good response, to antipsychotics.8 The authors of a meta-analysis2 claim that conclusions about the efficacy of CBT have been exaggerated, given that most large, robust trials have not shown significant effects at end of treatment, and that effect sizes are reduced overall if only studies of high quality are included in meta-analyses.

Antipsychotics are associated with a wide range of adverse effects.5, 9 Metabolic effects are of particular concern, in view of the increased cardiovascular mortality in people with psychosis compared with the general population.10 Adverse effects of CBT in psychosis have not been well studied.2 Potential side-effects, such as stigma and deterioration of mental state,11 were not detected in clinical trials of CBT for people with psychotic experiences. Rather, CBT resulted in significant reductions in the frequency of these side-effects.12, 13 However, CBT delivered in the context of a poor therapeutic relationship could be harmful.14

Whereas most evidence for the efficacy of CBT for psychosis is from randomised controlled trials in which CBT was provided as an adjunct to antipsychotics (ie, a combination of both vs antipsychotics alone), preliminary evidence suggests that CBT might be helpful for people with psychosis who are not taking antipsychotics.13 No data for the relative head-to-head efficacy or acceptability of CBT and antipsychotics in schizophrenia are available. We investigated the feasibility of doing a three-group randomised controlled trial of CBT, antipsychotics, and a combination of CBT and antipsychotics in people with psychosis.

Methods

Study design and participants

We did a single-blind, randomised, controlled pragmatic pilot and feasibility trial between April 1, 2014, and June 30, 2017 in four specialist mental health National Health Service trusts in Greater Manchester, UK. Eligible participants were aged 16 years or older; met ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder, or met the entry criteria for an early intervention for psychosis service (operationally defined with the PANSS), because most individuals with first-episode psychosis will receive care from specialist teams, as recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines; were in contact with mental health services, under the care of a consultant psychiatrist; scored at least 4 on the PANSS delusions or hallucinations items, or at least 5 on suspiciousness, persecution, or grandiosity items; and had to have the capacity to consent and also had to be help-seeking.

Exclusion criteria were receipt of antipsychotic medication or structured CBT with a qualified therapist within the past 3 months, moderate-to-severe learning disabilities, organic impairment, a score of 5 or more on the PANSS conceptual disorganisation item, and a primary diagnosis of alcohol or substance dependence; patients who were an immediate risk to themselves or others, and those who did not speak English were also excluded. The PANSS was administered by a research assistant in the participant's home or a suitable clinical service to establish eligibility, which was confirmed by a qualified clinician. Our trial protocol was approved by the National Research Ethics Service of the UK's National Health Service (14/NW/0041). All participants provided written informed consent.

Randomisation and masking

Participants were recruited via care coordinators, consultant psychiatrists, and other mental health staff within participating mental health National Health Service trusts. Eligible participants were then randomly assigned (1:1:1) to antipsychotics, CBT, or antipsychotics plus CBT via a secure web-based randomisation system (Sealed Envelope) operated by the trial administrator. We used randomised permuted blocks of 4 and 6, stratified by gender and first episode status. Randomisation at the individual level was independent and concealed, with all assessors masked to group allocation. Allocation was subsequently made known to the trial manager, trial administrator, and therapists. Participants and their care team were informed of the allocation by letter.

Procedures

Participants allocated to CBT were offered up to 26 sessions of therapy based on a specific cognitive model15 during a 6-month treatment window. Up to four optional booster sessions were available during the subsequent 6 months. Therapy was individualised and problem focused. Permissible interventions were described in the manualised treatment protocol.16 Therapy sessions were usually offered weekly and delivered by appropriately qualified psychological therapists. Fidelity to protocol was ensured by weekly supervision and regular rating of recorded sessions with the Cognitive Therapy Scale–Revised.17

Participants allocated to antipsychotics were prescribed medication by their responsible psychiatrist. Treatment was begun as soon as possible after randomisation. Prescribing mirrored standard clinical practice, and thus there were no restrictions on the antipsychotics that could be selected or their doses. Clinicians could switch antipsychotics and adjust doses as clinically indicated, but were encouraged to continue antipsychotic treatment for a minimum of 12 weeks, and preferably for at least 26 weeks. Participants allocated to the combined treatment group were offered CBT and antipsychotic medications as described for the monotherapy groups.

Clinicians could prescribe drugs other than antipsychotics, including antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics, for all participants. Participants were offered monitoring assessments at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks, and 52 weeks. At each assessment, we measured weight, blood pressure, HbA1c concentrations, fasting glucose concentrations, and fasting lipids (ie, total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides and prolactin concentrations). To allay concerns about the safety of withholding antipsychotics medication in the CBT group, trial procedures included monitoring for deterioration. Any participant randomly assigned to either CBT alone or antipsychotics alone could be moved to the combined treatment group if their mental state declined during the trial (this procedure was detailed in the standard operating procedures for the study and was presented to the Research Ethics Committee and clinicians who referred to the study). Participants who experienced such deterioration remained in the trial, and the assessment schedule was maintained. Participants were also given the option to move into the combined treatment group if deterioration in mental state led to involuntary hospitalisation, or if there was a greater than 25% deterioration in PANSS scores at the 6-week assessment or a greater than 12·5% deterioration in PANSS scores at the 12-week assessment.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was feasibility, which was operationalised in terms of referral rates, recruitment, retention or attrition, acceptability of treatment, attendance at sessions, adherence to homework, and compliance with medication. The primary effectiveness outcome was total score on PANSS18—a 30-item, semi-structured interview assessing dimensions of psychosis symptoms rated on a seven-point scale between 1 (absent) and 7 (severe)—which was assessed at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks, and 52 weeks. Secondary clinical outcomes were depression and anxiety (assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale19), quality of life (assessed with the WHO Quality of Life20), social functioning (assessed with the Personal and Social Performance scale21), user-defined recovery (measured with the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery22), and results on the Clinical Global Impressions of symptom severity and improvement scale.23 Instruments were administered by research assistants trained in their use to achieve a good level of inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient 0·902).

Service use, diagnosis, and antipsychotic prescribing were recorded via review of case notes. Duration of antipsychotic treatment for each participant was based on all regular antipsychotics prescribed and was not restricted to the primary antipsychotic (ie, the antipsychotics prescribed for the longest during the study). Non-neurological side-effects were assessed systemically with the Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale.24 At 6 months, we obtained self-report data for antipsychotic adherence in the past month on a visual analogue scale. At the 52-week visit, we surveyed participants' opinions on their preferences and views of measures used in the study to inform choice of measures for a definitive trial.

After the original ethical approval for the trial in February, 2014, a substantial protocol amendment was made (and approved on July 7, 2014): the lower age limit was changed from 18 years to 16 years, being an inpatient was removed as an exclusion criterion, posing an immediate risk to self or others was introduced as an exclusion criterion, and the randomisation timeframe was amended from 2 working days to 5 working days. Other minor amendments included the addition of service user and clinician surveys to gather information about the feasibility of recruitment. We had originally proposed that the recruitment window would be variable, with participants recruited in the first 22 months receiving a full 6 months' follow up and participants recruited thereafter offered assessments up to the end of treatment. However, we agreed a no-cost extension with the funder, and were thus able to complete 12-month follow-up visits for all participants. We also originally proposed that economic analyses would explore the costs of health and social care and quality-adjusted life years from a broadly societal perspective. However, the EQ5D was erroneously omitted from our assessment battery, meaning that such analyses were not possible.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was based on recommendations for obtaining reliable sample size estimates in pilot and feasibility studies,25 which suggested that 75 patients would be needed (ie, 25 in each group), with the aim of achieving usable data for 60 participants across the three groups, allowing for a dropout rate of 20%.26 Primary analysis was by intention to treat. We fitted random intercept models with summed scores as dependent variables, allowing for attrition and the variable follow-up times introduced by trial design. Covariates were sex, age, time, and the baseline value of the relevant outcome measure (first episode status, as a stratification factor, should have been included, but because only two participants were not having their first episode of psychosis, age was a more appropriate covariate). The use of these models allowed for analysis of all available data, on the assumption that data were missing at random,27 conditional upon covariates. All treatment effects reported are estimates of the effects common to all follow-up times (essentially, repeated measures ANCOVAs). Because safety and unwanted effects should be analysed on the basis of the most accurate information, these results are reported with an as-treated rather than an intention-to-treat approach. As-treated was defined with our predefined minimum dose criteria for antipsychotics (ie, at least 6 weeks at a therapeutic dose) and CBT (at least six sessions). We used Stata (version 14.2) for all analyses. This trial was prospectively registered with ISRCTN (number ISRCTN06022197).

Role of the funding source

The funder had no role in study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; or writing of the Article. The corresponding author and RE had access to all study data, and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Between May 1, 2014 and Aug 30, 2016, we recruited 75 participants, 26 to CBT, 24 to antipsychotics, and 25 to antipsychotics plus CBT (figure; table 1). The referral to recruitment rate was roughly 2:1, with only 22 (16%) of 138 referred patients declining to participate. 73 patients were experiencing first-episode psychosis and recruited from early-intervention services; the other two patients had multiple previous episodes and were recruited from community mental health services. Most participants did not have diagnoses in their medical records at baseline. The most common entry was first-episode psychosis, and the most common formal ICD-10 diagnosis was F29 unspecified non-organic psychosis. Participants from ten of the 22 participating clinical teams (appendix) were randomly assigned. Retention was reasonable, with only four withdrawals and low attrition, which were balanced across the groups (figure). Nine (12%) partial blind breaks (ie, only one treatment was revealed) and five (7%) full blind breaks (ie, actual randomly assigned group was revealed) were reported by research assistants. Four of the full blind breaks were in the antipsychotic arm, and one was in the combined arm. Only 3 (1%) of 256 follow-up assessments were done by an unmasked assessor (the blind was broken during the assessment). All three of these assessments were then scored by a masked rater, and consensus was reached on ratings. Thus, no assessments were done without rater masking

Figure.

Trial profile

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Antipsychotics (n=24) | CBT (n=26) | Antipsychotics plus CBT (n=25) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 23·21 (4·97) | 23·19 (6·32) | 24·44 (6·86) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 13 (54%) | 16 (62%) | 14 (56%) | |

| Female | 11 (46%) | 10 (38%) | 11 (44%) | |

| First-episode psychosis: multiple episode psychosis | 24:0 | 24:2 | 25:0 | |

| Duration of untreated psychosis, weeks | 37·33 (44·41) | 44·48 (52·30) | 39·43 (35·76) | |

| PANSS | ||||

| Total | 70·17 (10·12) | 70·50 (8·12) | 70·76 (8·45) | |

| Positive | 23·04 (4·60) | 23·15 (4·63) | 21·92 (3·63) | |

| Negative | 16·17 (5·72) | 15·50 (4·10) | 15·24 (5·17) | |

| Disorganised | 16·25 (2·60) | 17·15 (3·65) | 17·8 (4·27) | |

| Excitement | 18·25 (4·35) | 17·85 (3·86) | 17·4 (4·14) | |

| Emotional Distress | 25·46 (5·00) | 25·31 (3·83) | 26·28 (3·47) | |

| Questionnaire about Process of Recovery | 38·71 (9·23) | 40·13 (9·33)* | 41·8 (11·79) | |

| HADS† | ||||

| Total | 41·05 (5·49) | 37·54 (5·42) | 36·36 (6·76) | |

| Anxiety | 21·96 (2·62) | 20·50 (3·32) | 19·36 (3·89) | |

| Depression | 19·05 (4·87) | 17·38 (3·32) | 17·28 (5·55) | |

| WHO quality of life score‡ | 67·03 (14·99) | 68·66 (13·41) | 70·18 (15·41) | |

| Personal and Social Performance Scale | 52·67 (13·83) | 57·38 (12·04) | 58·16 (11·1) | |

| CGI | ||||

| Participant version | 4·91 (0·97)§ | 4·42 (0·99) | 4·38 (1·54) | |

| Clinician version | 4·13 (0·74) | 4·08 (0·63) | 4·04 (0·68) | |

| ANNSERS | ||||

| Number of side-effects | 9·96 (4·72), 24 | 8·88 (3·77), 26 | 9·16 (4·69), 25 | |

| Total | 13·92 (7·05), 24 | 12·12 (6·55), 26 | 12·28 (6·61), 25 | |

| Cholesterol | ||||

| Total (mmol/L) | 4·54 (0·91), 20 | 4·08 (0·82), 15 | 4·45 (0·93), 16 | |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1·34 (0·35), 20 | 1·13 (0·30), 15 | 1·38 (0·40), 15 | |

| Total/HDL | 3·57 (0·94), 20 | 3·5 (0·86), 15 | 3·35 (0·93), 15 | |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2·58 (0·78), 15 | 2·33 (0·67), 12 | 2·46 (0·68), 14 | |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1·15 (0·39), 16 | 1·27 (0·64), 12 | 1·12 (0·45), 14 | |

| Prolactin (mU/L) | 183·06 (89·71), 17 | 187·07 (63·33), 15 | 198·5 (81·78), 14 | |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 6·27 (6·96), 18 | 5·32 (2·41), 15 | 4·14 (0·55), 15 | |

Data are mean (SD); mean (SD), number of observations; or n (%), unless otherwise specified. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. CGI=Clinical Global Impressions of Symptom Severity and Improvement Scale. ANNSERS= Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale.

n=25.

n=23 in the antipyschotics group and 24 in the CBT group.

n=25 in the CBT group and 24 in the antipsychotics plus CBT group.

n=22.

Participants who were assigned to CBT (either monotherapy or in the combined group) received a mean of 14·39 sessions (SD 9·12; range 0–26) within 6 months, with each session lasting around an hour (additional booster sessions were also offered as appropriate). 40 (78%) of 51 participants attended six or more sessions, and only one participant (2%) attended no sessions. Homework compliance was good for both participants and therapists: 404 (73%) of 557 participant between-session tasks and 396 (89%) of 445 therapist between-session tasks were completed.

Of the 49 participants assigned to antipsychotics (either alone or in combination with CBT), 11 (22%) were not prescribed a regular antipsychotic for various reasons, including five participants who declined to take an antipsychotic despite consenting to enter the trial. The primary antipsychotics prescribed most frequently were aripiprazole (n=14), olanzapine (n=10), and quetiapine (n=10), as chosen by the treating psychiatrist in the participants' clinical care team (appendix). 12 (32%) of the 38 participants treated with antipsychotics switched antipsychotics at least once. 34 (92%) of 37 participants who commenced antipsychotic treatment were prescribed their primary antipsychotic for 6 weeks or more (duration was not captured for one participant). The median duration of total antipsychotic treatment was 44·5 weeks (IQR 26–51; range 2–52). 28 (78%) of 36 participants with accurate duration data were taking antipsychotic medication at the end of the study.

Self-reported data for medication adherence were available at 6 months for 42 (86%) of the 49 participants (86%) assigned to antipsychotics. 29 participants (69%) reported that they were taking an antipsychotic at that timepoint, among whom mean adherence was 77% (SD 29·19, range 0–100; on a scale on which 100% indicates they had taken every dose over the past month).

The proportion of patients receiving allocated interventions was similar across groups (table 2). 15 patients (58%) in the CBT group, 15 (63%) in the antipsychotics group, and 14 (56%) in the combined group received the correct allocated intervention.

Table 2.

Participants' randomly assigned treatment vs treatment received

|

Randomly assigned treatment group |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics (n=24) | CBT (n=26) | Antipsychotics plus CBT (n=25) | |||

| Treatment received | |||||

| Antipsychotics | 15 | 2 | 4 | 21 | |

| CBT | 0 | 15 | 5 | 20 | |

| Antipsychotics plus CBT | 1 | 6 | 14 | 21 | |

| Neither | 8 | 3 | 2 | 13 | |

CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy.

Psychiatric symptoms were significantly reduced over time across all conditions (appendix). The PANSS total score differed significantly between the combined group and the CBT group (p=0·019), but not between the combined group and the antipsychotics group (p=0·064), or between the CBT group and the antipsychotics group (p=0·637; table 3). Table 4 shows results for secondary outcomes. PANSS analyses that did not include age as a covariate had similar results to the primary analyses (appendix).

Table 3.

Outcomes on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

| Antipsychotics (n=24) | CBT (n=26) | Antipsychotics plus CBT (n=25) |

Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT vs antipsychotics | CBT vs antipsychotics plus CBT | Antipsychotics vs antipsychotics plus CBT | |||||

| Total | .. | .. | .. | −1·13 (2·39; −5·81 to 3·55); 0·637 | −5·65 (2·41; −10·37 to −0·93); 0·019 | −4·52 (2·44; −9·30 to 0·26); 0·064 | |

| Week 0 | 70·13 (10·11), 24 | 70·35 (8·03), 26 | 70·76 (8·46), 25 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 6 | 64·05 (11·39), 22 | 64·85 (7·85), 20 | 64·70 (9·74), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 12 | 60·81 (16·52), 21 | 63·74 (7·73), 23 | 58·40 (14·51), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 24 | 61·09 (14·44), 22 | 60·50 (8·74), 22 | 53·77 (12·54), 22 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 52 | 56·77 (14·10), 22 | 58·14 (11·68), 21 | 57·40 (13·58), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Positive | .. | .. | .. | −1·16 (1·14; −3·40 to 1·09); 0·312 | −2·02 (1·15; −4·27 to 0·24); 0·080 | −0·86 (1·17; −3·15 to 1·43); 0·462 | |

| Week 0 | 23·04 (4·60), 24 | 23·15 (4·63), 26 | 21·92 (3·63), 25 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 6 | 19·36 (5·44), 22 | 21·00 (4·38), 20 | 20·10 (4·41), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 12 | 19·19 (7·72), 21 | 21·00 (4·72), 23 | 17·40 (5·65), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 24 | 17·81 (6·85), 21 | 18·18 (4·81), 22 | 15·23 (5·31), 22 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 52 | 18·18 (6·52), 22 | 17·90 (5·92), 21 | 16·80 (6·05), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Negative | .. | .. | .. | −1·25 (0·78; −2·78 to 0·28); 0·110 | −2·31 (0·79; −3·85 to −0·77); 0·003 | −1·06 (0·79; −2·61, 0·49); 0·178 | |

| Week 0 | 16·17 (5·72), 24 | 15·50 (4·10), 26 | 15·24 (5·17), 25 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 6 | 14·64 (5·06), 22 | 15·05 (3·52), 20 | 13·90 (4·85), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 12 | 14·00 (4·32), 21 | 14·83 (3·10), 23 | 13·00 (5·23), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 24 | 14·14 (5·47), 22 | 14·91 (4·72), 22 | 12·41 (4·60), 22 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 52 | 12·73 (4·58), 22 | 14·62 (4·52), 21 | 12·80 (3·68), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Disorganised | .. | .. | .. | −0·19 (0·77; −1·69 to 1·32); 0·809 | −0·85 (0·77; −2·36 to 0·66); 0·273 | −0·66 (0·80; −2·22 to 0·90); 0·408 | |

| Week 0 | 16·25 (2·59), 24 | 17·15 (3·65), 26 | 17·80 (4·27), 25 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 6 | 15·77 (3·18), 22 | 16·8 (2·91), 20 | 17·50 (4·01), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 12 | 15·19 (4·96), 21 | 16·39 (3·37), 23 | 16·25 (4·10), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 24 | 15·10 (3·86), 21 | 15·50 (3·53), 22 | 14·50 (3·78), 22 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 52 | 14·82 (3·67), 22 | 15·67 (3·73), 21 | 15·80 (4·25), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Excitement | .. | .. | .. | −0·45 (0·75; −1·91 to 1·02); 0·549 | −0·80 (0·75; −2·27 to 0·67); 0·286 | −0·35 (0·76; −1·84 to 1·13); 0·641 | |

| Week 0 | 18·25 (4·35), 24 | 17·85 (3·86), 26 | 17·4 (4·14), 25 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 6 | 15·95 (4·09), 22 | 15·90 (3·93), 20 | 15·75 (4·05), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 12 | 15·52 (4·77), 21 | 15·52 (3·16), 23 | 14·35 (4·97), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 24 | 14·77 (3·37), 22 | 14·45 (3·40), 22 | 12·86 (4·36), 22 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 52 | 13·41 (4·07), 22 | 13·62 (2·89), 21 | 13·80 (4·26), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Emotional distress | .. | .. | .. | 0·0 (1·11; −2·17 to 2·18); 0·999 | −1·93 (1·12; −4·12 to 0·26); 0·084 | −1·93 (1·13; −4·15 to 0·29); 0·088 | |

| Week 0 | 25·46 (5·00), 24 | 25·31 (3·83), 26 | 26·28 (3·47), 25 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 6 | 22·55 (5·21), 22 | 21·50 (4·27), 20 | 23·10 (3·93), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 12 | 21·38 (6·91), 21 | 22·48 (4·31), 23 | 19·60 (5·74), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 24 | 21·55 (5·75), 22 | 20·95 (3·70), 22 | 17·50 (5·49), 22 | .. | .. | .. | |

| Week 52 | 19·86 (6·12), 22 | 19·10 (5·49), 21 | 20·10 (5·08), 20 | .. | .. | .. | |

Data are mean (SD), number of observations, unless otherwise specified. The effects are common to all follow-up times and are analysed by intention to treat. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy.

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes

| Antipsychotics (n=24) | CBT (n=26) | Combination (n=25) |

Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT vs antipsychotics | CBT vs antipsychotics plus CBT | Antipsychotics vs antipsychotics plus CBT | ||||||

| QPR | .. | .. | .. | −0·93 (2·97; −6·76 to 4·90); 0·754 | 4·01 (3·14; −2·15 to 10·17); 0·202 | 4·94 (3·05; −1·03 to 10·91); 0·105 | ||

| Week 0 | 38·71 (9·23), 24 | 40·13 (9·33), 25 | 41·8 (11·79), 25 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 44·86 (14·99), 22 | 47·81 (8·86), 21 | 52 (14·05), 18 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 48·55 (14·73), 22 | 51·62 (9·25), 21 | 49·88 (11·04), 17 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| HADS | ||||||||

| Total | .. | .. | .. | −0·60 (1·98; −4·48 to 3·27); 0·761 | −2·93 (2·03; −6·90 to 1·04); 0·148 | −2·32 (1·99; −6·22 to 1·56); 0·241 | ||

| Week 0 | 41·05 (5·49), 23 | 37·54 (5·42), 24 | 36·36 (6·76), 25 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 35·55 (7·69), 22 | 35·36 (12·61), 22 | 30·37 (9·28), 19 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 34·27 (9·08), 22 | 32·14 (6·96), 21 | 30·35 (6·98), 17 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Anxiety | .. | .. | .. | 0·62 (1·28; −1·89 to 3·14); 0·627 | −1·34 (1·32; −3·92 to 1·25); 0·310 | −1·96 (1·30; −4·50 to 0·58); 0·131 | ||

| Week 0 | 21·96 (2·62), 23 | 20·5 (3·32), 24 | 19·36 (3·89), 25 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 19·36 (4·51), 22 | 19·18 (10·80), 22 | 15·65 (5·98), 20 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 18·73 (5·03), 22 | 17·29 (4·64), 21 | 15·67 (4·89), 18 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Depression | .. | .. | .. | −0·14 (1·20; −2·49 to 2·20); 0·905 | −1·60 (1·27; −4·08 to 0·88); 0·206 | −1·46 (1·20; to −3·82 to 0·90); 0·226 | ||

| Week 0 | 19·05 (4·87), 23 | 17·38 (3·32), 24 | 17·28 (5·55), 25 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 16·27 (5·84), 22 | 15·18 (3·81), 22 | 13·42 (5·83), 19 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 14·91 (5·52), 22 | 14·05 (4·2), 21 | 14·94 (5·36), 17 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| WHO quality of life score | .. | .. | .. | 0·62 (3·20; −5·65 to 6·88); 0·847 | 5·82 (3·37; −0·78 to 12·42); 0·084 | 5·21 (3·39; −1·43 to 11·84); 0·124 | ||

| Week 0 | 67·03 (14·99), 24 | 68·66 (13·41), 25 | 70·18 (15·41), 24 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 6 | 72·5 (19·84), 22 | 76·78 (14·79), 18 | 77·82 (14·06), 17 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 12 | 77·29 (21·31), 21 | 79·29 (16·59), 21 | 85·83 (17·59), 18 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 79·15 (20·95), 20 | 79·10 (14·03), 21 | 89·06 (18·87), 18 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 81·36 (20·02), 22 | 83·81 (15·23), 21 | 82·93 (19·17), 15 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| PSP | .. | .. | .. | 3·18 (4·18; −5·02 to 11·38); 0·448 | 2·17 (4·27; −6·19 to 10·53); 0·611 | −1·01 (4·24; −9·32 to 7·30); 0·812 | ||

| Week 0 | 52·67 (13·83), 24 | 57·38 (12·04), 26 | 58·16 (11·1), 25 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 63·95 (18·53), 22 | 60·05 (10·51), 22 | 62·48 (17·47), 21 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 60·45 (17·61), 22 | 60·95 (12·93), 21 | 61 (16·47), 20 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| CGI | ||||||||

| Clinician | .. | .. | .. | −0·16 (0·28; −0·70 to 0·38); 0·569 | −0·64 (0·29; 1·20 to −0·08); 0·026 | −0·48 (0·28; −1·03 to 0·07); 0·087 | ||

| Week 0 | 4·13 (0·74), 24 | 4·08 (0·63), 26 | 4·04 (0·68), 25 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 3·32 (1·17), 22 | 3·45 (0·91), 22 | 2·86 (1·06), 21 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 3·23 (1·11), 22 | 3·38 (1·07), 21 | 3·00 (1·08), 20 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Patients | .. | .. | .. | 0·35 (0·41; −0·44 to 1·15); 0·385 | −0·29 (0·42; 1·11 to 0·52); 0·482 | −0·65 (0·42; −1·46 to 0·17); 0·119 | ||

| Week 0 | 4·91 (0·97), 22 | 4·42 (0·99), 26 | 4·38 (1·54), 25 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 4·33 (1·56), 21 | 3·71 (1·23), 21 | 3·20 (1·54), 20 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 3·91 (1·48), 22 | 3·50 (1·50), 20 | 3·94 (1·59), 18 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Clinician − improvement | .. | .. | .. | 0·05 (0·31; −0·56 to 0·65); 0·876 | −0·53 (0·32; −1·16 to 0·10); 0·097 | −0·58 (0·31; −1·19 to 0·03); 0·064 | ||

| Week 0 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 2·95 (1·21), 22 | 2·78 (1·23), 22 | 2·14 (0·91), 21 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 2·45 (1·06), 22 | 2·50 (1·00), 20 | 2·25 (1·12), 20 | .. | .. | .. | ||

Data are mean (SD), number of observations, unless otherwise specified. The effects are common to all follow-up times and are analysed by intention to treat. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. QPR=Questionnaire about Process of Recovery. HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. PSP=Personal and Social Performance Scale. CGI=Clinical Global Impressions of Symptom Severity and Improvement Scale.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, the numbers of participants in each group (completer-only data—ie, observed cases) achieving 25% and 50% improvements on adjusted PANSS total scores28 were highest in the combined arm at 6 months, and very similar across all groups at 12 months (table 5). In the as-treated analysis, few deteriorations were noted in any groups at both 6 months and 12 months (table 5).

Table 5.

Participants with improvements or deteriorations in total scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale at 24 and 52 weeks

|

Deterioration |

Improvement |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >25% | >50% | >25% | >50% | ||

| Intention-to-treat analysis | |||||

| 24 weeks | |||||

| CBT | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2 | |

| Antipsychotics | 0 | 1 | 5 | 3 | |

| Antipsychotics plus CBT | 0 | 0 | 11 | 7 | |

| 52 weeks | |||||

| CBT | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 | |

| Antipsychotics | 2 | 0 | 8 | 5 | |

| Antipsychotics plus CBT | 0 | 0 | 7 | 6 | |

| As-treated analysis | |||||

| 24 weeks | |||||

| CBT | 0 | 1 | 8 | 3 | |

| Antipsychotics | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| Antipsychotics plus CBT | 0 | 1 | 9 | 4 | |

| Neither | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| 52 weeks | |||||

| CBT | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | |

| Antipsychotics | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | |

| Antipsychotics plus CBT | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 | |

| Neither | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | |

Data are n. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy.

Adverse effects (as measured by ANNSERS) were significantly less common in the CBT group than in the antipsychotics (p=0·017) or the antipsychotics plus CBT (p=0·003) groups (table 6). The difference in adverse effects between the combined group and the antipsychotics group was not significant (table 6). In the as-treated analysis, no hospital admissions were recorded among those in the antipsychotics group or those who received no interventions (appendix). Two participants in the CBT group (four admissions) and four people in the combined group were admitted to hospital (appendix). Only three deteriorations were noted at 6 or 12 weeks in monotherapy participants (two in the antipsychotics group and one in the CBT group).

Table 6.

Secondary outcomes (adverse effects)

| Antipsychotics (n=21) | CBT (n=20) | Antipsychotics plus CBT (n=21) |

Mean difference (SE; 95% CI); p value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT vs antipsychotics | CBT vs antipsychotics plus CBT | Antipsychotics vs antipsychotics plus CBT | ||||||

| ANNSERS | ||||||||

| Number of side-effects | .. | .. | .. | 3·22 (1·35; 0·58 to 5·87); 0·017 | 3·99 (1·35; 1·36 to 6·64); 0·003 | 0·78 (1·37; −1·91 to 3·47); 0·572 | ||

| Week 0 | 8·52 (3·66), 21 | 8·55 (3·94), 20 | 10·33 (4·54), 21 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 8·47 (5·62), 17 | 5·7 (3·23), 20 | 10·05 (5·35), 19 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 9·06 (5·5), 16 | 4·74 (3·35), 19 | 10·42 (5·90), 19 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Total score | .. | .. | .. | 5·12 (2·05; 1·11 to 9·14); 0·012 | 6·30 (2·03; 2·32 to 10·27); 0·002 | 1·17 (2·07; −2·89 to 5·24); 0·571 | ||

| Week 0 | 11·57 (5·48), 21 | 11·7 (6·21), 20 | 13·62 (6·18), 21 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 24 | 11·59 (8·40), 17 | 7·45 (4·99), 20 | 14·16 (8·42), 19 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 12·94 (8·77), 16 | 6·21 (5·07), 19 | 13·79 (7·63), 19 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Cholesterol | ||||||||

| HDL (mmol/L) | .. | .. | .. | 0·07 (0·09; −0·10 to 0·24); 0·389 | 0·09 (0·09; −0·09 to 0·26); 0·346 | 0·01 (0·08; −0·15 to 0·17); 0·893 | ||

| Week 0 | 1·37 (0·35), 16 | 1·21 (0·32), 12 | 1·37 (0·41), 13 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 12 | 1·37 (0·38), 14 | 1·21 (0·29), 9 | 1·54 (0·49), 15 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 1·15 (0·36), 8 | 1·36 (0·31), 6 | 1·24 (0·21), 7 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Total/HDL ratio | .. | .. | .. | −0·08 (0·22; −0·50 to 0·35); 0·722 | 0·01 (0·24; −0·45 to 0·48); 0·950 | 0·09 (0·21; −0·33 to 0·51); 0·667 | ||

| Week 0 | 3·4 (0·85), 16 | 3·58 (0·66), 12 | 3·06 (0·81), 13 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 12 | 3·63 (1·25), 14 | 3·64 (0·44), 10 | 3·23 (0·65), 14 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 4·41 (2·11), 8 | 3·51 (0·53), 7 | 3·68 (1·05), 6 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| LDL (mmol/L) | .. | .. | .. | −0·21 (0·28; −0·76 to 0·33); 0·449 | −0·15 (0·29; −0·72 to 0·42); 0·615 | 0·06 (0·26; −0·45 to 0·58); 0·809 | ||

| Week 0 | 2·42 (0·79), 14 | 2·44 (0·58), 10 | 2·34 (0·72), 11 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 12 | 2·59 (0·72), 12 | 2·79 (0·92), 8 | 2·63 (0·74), 12 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 3·02 (0·84), 6 | 2·83 (0·59), 6 | 2·63 (0·90), 6 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | .. | .. | .. | 0·08 (0·19; −0·29 to 0·45); 0·659 | −0·27 (0·20; −0·66 to 0·12); 0·170 | −0·35 (0·18; −0·71 to 0·00); 0·051 | ||

| Week 0 | 1·23 (0·45), 14 | 1·16 (0·56), 10 | 1·15 (0·58), 11 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 12 | 1·45 (0·75), 12 | 1·4 (0·63), 8 | 1·11 (0·63), 13 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 1·62 (1·11), 6 | 0·97 (0·28), 6 | 2·57 (4·08), 7 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Prolactin (mU/L) | .. | .. | .. | 23·12 (26·73; −29·27 to 75·50); 0·387 | −7·39 (29·00; −64·22 to 49·44); 0·799 | −30·51 (28·28; −85·94 to 24·93); 0·281 | ||

| Week 0 | 162·86 (98·96), 14 | 188·42 (72·73), 12 | 221·58 (74·14), 12 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 12 | 206·92 (83·76), 13 | 196·22 (83·08), 9 | 180 (73·90), 10 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 136·71 (53·84), 7 | 201·83 (93·32), 6 | 186·13 (88·69), 8 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | .. | .. | .. | −0·56 (0·50; −1·53 to 0·42); 0·265 | −0·75 (0·52; −1·77 to 0·27); 0·148 | −0·19 (0·45; −1·07 to 0·68); 0·662 | ||

| Week 0 | 6·6 (7·63), 15 | 5·04 (2·68), 12 | 4·72 (0·95), 13 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 12 | 4·76 (1·10), 11 | 5·2 (1·72), 7 | 4·55 (0·55), 14 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 4·63 (0·65), 8 | 5·32 (1·81), 6 | 4·11 (0·76), 7 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Weight (kg) | .. | .. | .. | 1·80 (1·40; −0·94 to 4·54); 0·198 | 3·70 (1·41; 0·93 to 6·47); 0·009 | 1·90 (1·36; −0·76 to 4·57); 0·162 | ||

| 0 | 75·91 (20·31), 21 | 73·62 (15·72), 18 | 70·93 (12·97), 21 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 6 | 77·06 (18·20), 16 | 74·84 (17·27), 15 | 70·82 (13·56), 18 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 12 | 72·87 (13·32), 16 | 73·58 (15·66), 19 | 73·86 (14·01), 19 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 24 | 78·21 (17·38), 18 | 72·12 (15·14), 20 | 75·33 (13·59), 16 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| 52 | 74·87 (15·34), 16 | 75·71 (14·88), 15 | 75·22 (15·07), 18 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | .. | .. | .. | 1·36 (2·76; −4·06 to 6·78); 0·624 | 0·52 (2·83; −5·04 to 6·07); 0·855 | −0·84 (2·44; −5·61 to 3·93); 0·730 | ||

| Week 0 | 124·12 (12·91), 20 | 124·05 (15·02), 14 | 118·98 (11·11), 19 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 12 | 124·49 (16·53), 14 | 122·13 (10·16), 14 | 123·86 (14·13), 17 | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Week 52 | 123·6 (13·28), 16 | 122·22 (10·67), 10 | 116·9 (8·47), 18 | .. | .. | .. | ||

Data are mean (SD), number of observations on an as-treated basis, unless otherwise specified. CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy. ANNSERS=Antipsychotic Non-neurological Side Effects Rating Scale.

*ANNSERS consists of 43 non-neurological side-effects, each rated as absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3), with a total possible score of 129.

We recorded another ten potential serious adverse events in nine participants (appendix). Only one of these events was thought to be related to the trial (the overdose of three paracetamol tablets in a participant in the CBT group). Only three participants (two in the antipsychotics group, one in the CBT group) met our deterioration criteria at 6 or 12 weeks, which prompted an offer to move into the combined arm.

Discussion

Our single-blind, randomised, controlled pragmatic pilot and feasibility trial showed that a study comparing antipsychotics, CBT, and antipsychotics plus CBT is possible in people with psychosis. Our trial had low attrition (<20% at each timepoint) that was balanced across interventions, and only a small proportion of participants received an intervention to which they were not allocated. All three interventions were broadly safe and acceptable.

The mean baseline PANSS total score in the overall population was 70·4, which is similar to the baseline PANSS score of 73·8 seen in the CAFÉ study,29 but lower than the baseline score of 88·5 in EUFEST30 (CAFÉ and EUFEST are large, 1-year randomised controlled trials of antipsychotics in early psychosis). The mean changes in PANSS total scores we noted from baseline to 52 weeks (antipsychotics 13·3, CBT 12·3, antipsychotics plus CBT 13·4) were all within the range of those noted with the three antipsychotics in CAFÉ (olanzapine 18·4, quetiapine 15·6, risperidone 8·4), but lower than those in EUFEST (changes of around 35 points with the five antipsychotics assessed). The mean PANSS reductions we noted were less than the 15 points estimated to be equivalent to a rating of minimal improvement on the Clinical Global Impressions scale,31 although the threshold for minimal improvement could be lower for patients with less severe symptoms at baseline.31 The reductions in our trial were larger than the minimal clinically important difference in PANSS total score estimated to be associated with obtaining employment as an objective measure of functioning (8·3 points),32 and similar to the minimal clinically important difference associated with patient-rated improvement (11·2 points).33 We recorded improvement across measures of symptoms and personal and social recovery, functioning, and quality of life, irrespective of intervention.

Antipsychotics plus CBT was significantly more efficacious than CBT alone (p=0·019), but the difference between antipsychotics plus CBT and antipsychotics alone was not significant (p=0·06). However, because this study was a pilot and feasibility trial, it was not powered to reliably detect differences between groups, and any significant differences should be treated with caution. Efficacy did not differ significantly between the CBT group and the antipsychotic group, which is noteworthy given that CBT finished after 24 weeks whereas antipsychotic treatment could last 52 weeks (median duration 44·5 weeks). The absence of any apparent differences between the three groups at 6 weeks is also noteworthy (appendix), because 6 weeks is a common length for drug trials. The number of participants with PANSS-rated deterioration was low across all groups at each timepoint, with no suggestion that CBT was worse than antipsychotics or combination treatment. Only three early deteriorations (ie, at 6 or 12 weeks) were noted, two in the antipsychotics group and one in the CBT group.

Fewer side-effects were noted in the CBT group than in the antipsychotic group or the combined intervention group. However, this difference is more accounted for by reduction in side-effects over time in the CBT group than by increases in side-effects in the antipsychotic and combined groups. This decrease in side-effects in the CBT group could be related to many ANNSERS items being non-specific (eg, sleep problems, memory and attention, loss of libido, loss of energy, and autonomic symptoms). Such symptoms could be symptoms of a psychotic disorder or a comorbid illness, or could be antipsychotic side-effects. Some patients in the CBT group and the combined group were admitted to hospital, whereas no patients in the antipsychotic group were. Similarly, no serious adverse events were reported to the ethics committee for the antipsychotics group, compared with two for the CBT group and four for the combined group (although only one was deemed treatment related). There is increased opportunity for adverse events to be observed in the patients receiving CBT, because they had weekly contact with trial staff tasked with reporting adverse effects (the trial therapists). By contrast, patients in the antipsychotics group had much less frequent contact with trial staff (the trial research assistants).

The number of sessions attended and compliance with homework tasks suggests that CBT was delivered successfully to most participants, although competence of CBT delivery and adherence to the treatment protocol was not monitored systematically. Antipsychotics were selected on an individual basis, consistent with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance. The four antipsychotics used most frequently in the study (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) are the four antipsychotics most commonly initiated in routine clinical practice in first-episode services in the UK.34 Dose and duration of antipsychotic treatment were at the discretion of the treating clinician and patient wishes. One patient's primary antipsychotic was promazine, which is approved to treat agitation but not psychosis; the low dose given was insufficient to be regarded as an effective antipsychotic dose (appendix). The mean modal doses of the other primary antipsychotics prescribed were at the low end of the dose ranges recommended to treat psychosis, which is probably because participants were recruited almost exclusively from early-intervention services. People with first-episode psychosis respond to doses of antipsychotics lower than those required for multi-episode schizophrenia,29 and are more sensitive to side-effects than patients with multi-episode schizophrenia, which has led to guidelines recommending low doses.35, 36 Nevertheless, the doses of some of the antipsychotics, especially quetiapine, were lower than the corresponding doses used in the CAFÉ and EUFEST trials in first-episode psychosis. In most cases in our study, when duration of antipsychotic treatment was known, the primary antipsychotic was continued for 6 weeks or longer, suggesting that treatment duration was sufficient to establish effectiveness. 12 (32%) of the 38 participants who started antipsychotic treatment switched antipsychotic at least once, implying perseverance to identify an effective medication. Overall, use of antipsychotics was pragmatic and broadly consistent with clinical practice in early-intervention services and treatment guidelines.

The study had several limitations. The pilot and feasibility trial design and small sample size mean that caution should be used when interpreting the statistical tests and significance values. Although only 12% of participants received an intervention they were not allocated to, a reasonable proportion did not take up the offer of allocated interventions, reflecting that in clinical practice many people do not comply with medication regimens,34 and some do not engage with talking therapies. Such rates of non-adherence are common in drug and psychological therapy trials. Operationalisation of antipsychotic treatment in terms of target doses, minimal duration of trials, and encouraging switching if treatment was unsatisfactory might have improved the efficacy of drug treatment, but higher doses might have led to more side-effects and greater dropout rates. In our trial, medication was prescribed and dispensed in accordance with normal clinical practice, as opposed to delivery of medication to patients and use of regular pill counts, both of which might improve adherence. The absence of weight gain in the antipsychotics group casts doubt on adherence. We did not have a standardised operating procedure for weight measurement that emphasised consistency of flooring, and many assessments were done in participants' homes. Therefore, weight data could contain errors. Another limitation is that we did not systematically record use of other medications such as antidepressants or anxiolytics, or measure substance and alcohol use.

Response rates on the PANSS and the degree of improvement on the Clinical Global Impressions scale were lower in our trial than in previous 52-week randomised controlled trials of antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis.29, 30 However, data analytic strategies and high attrition in these studies might have increased the risk of bias, which could inflate effects. In EUFEST,30 for example, data obtained before treatment discontinuation were used in analysis of PANSS outcomes, which was likely to have introduced bias given the high frequency of discontinuation (33–72%, depending on the specific drug). CAFÉ had very high attrition at 52 weeks (67–73%, depending on drug), which probably introduced bias.29 Response is also dependent on patient and illness characteristics, which vary between studies. Our study mostly involved participants who met PANSS-defined criteria for acceptance into early-intervention services, whereas EUFEST and CAFÉ only included participants with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses.

Our sample was diagnostically heterogeneous: 73 participants were recruited from early-intervention services, which operationally define first-episode psychosis with the PANSS. Therefore, our findings are generalisable to early-intervention services only, at least in the UK, and should not be generalised to patients with long-term schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses.

The design of our study (ie, three active intervention arms), combined with the fact that most participants received care from early-intervention services, means that we cannot rule out the possibility that recorded benefits could be attributable to generic factors such as good care coordination, engagement, assertive outreach, and crisis management, rather than the specific active treatments. Failure to include the EQ5D means we could not examine quality-adjusted life-years and cost-effectiveness.

The main implication of this trial is that an adequately powered efficacy and effectiveness trial is needed to provide evidence about relative efficacy of antipsychotics and CBT. In our trial, participants were almost exclusively experiencing a first episode of psychosis, so a definitive trial should target this population and recruit via early-intervention services (appendix). A trial in people with multiple episode psychotic disorders would probably not be feasible in generic community mental health teams, mostly because potential participants are already prescribed antipsychotics. At present, it seems reasonable to support people with psychosis (who do not present immediate risk to themselves or others) to make informed choices as outlined in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines,1 which recommend advising people who want to try psychological interventions alone that such interventions are more effective when delivered in conjunction with antipsychotic medication, but allowing them to try family intervention and CBT without antipsychotics while agreeing a time to review treatment options, including introduction of antipsychotics.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG- 1112-29057). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, NIHR, the Department of Health, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, or the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. We thank the Psychosis Research Unit Service User Reference Group for their contributions to study design and development of study-related materials, the Greater Manchester Clinical Research Network for their support and assistance, and David Kingdon and John Norrie, the independent members of our trial steering and data monitoring committee. We also thank Elizabeth Pitt for acting as a service user consultant for the trial (because of unforeseen circumstances, she could not be contacted about this acknowledgment).

Contributors

All authors were involved in study design, management, and delivery, and contributed to drafting of this Article. APM was the chief investigator, conceived the study, prepared the protocol, supervised researchers, had overall responsibility for day-to-day running of the study, interpreted data, led writing of the Article, and is the study guarantor. APM, PF, EKM, NH, AS, SEB, and JP-C prepared the treatment protocol and trained and supervised the therapists. APM, HL, MP, and PMH trained the researchers in use of psychiatric interviews, and supervised and monitored standards of psychiatric interviewing and assessment throughout the trial. APM, PF, ARY, and PMH advised on diagnostic ratings and inclusion and exclusion criteria. DS, ARY, and PMH advised on medical and pharmacological issues and liaised with prescribers. HL was the trial manager, supervised and coordinated recruitment, contributed to training of research staff, and was responsible for staff management and overall study coordination. HL, LC, RS, and MP were responsible for maintaining reliability of assessment procedures and data collection. RE, the trial statistician, advised on randomisation and all statistical aspects of the trial, developed the analysis plan, and did the statistical analyses. LD was the health economist. RB was a service user consultant involved in all aspects of the study.

Declaration of interests

APM, PF, and SEB deliver training workshops and have written textbooks about CBT for psychosis, for which they receive fees. All authors have done funded research on CBT for psychosis, and RE, ARY, LD, and PMH have done funded research on antipsychotics. APM, PF, EKM, NH, AS, SEB, JP-C, and VB deliver CBT in the National Health Service. DS is an expert adviser for the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence Centre for Guidelines and a board member of the National Collaborating Centre of Mental Health. ARY has received honoraria from Janssen Cilag and Sunovion. PMH has received honoraria for lecturing or consultancy work from Allergan, Galen, Janssen, Lundbeck, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka, Sunovion, and Teva, plus conference support from Janssen, Lundbeck and Sunovion. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; London: 2014. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J, Fung E, Salvador R, Laws KR. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:20–29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:523–537. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehl S, Werner D, Lincoln TM. Does cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis (CBTp) show a sustainable effect on delusions? A meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1450. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, Kissling W, Davis JM. How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:429–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leucht S, Leucht C, Huhn M. Sixty years of placebo-controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:927–942. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16121358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Y, Li C, Huhn M, Rothe P. How well do patients with a first episode of schizophrenia respond to antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;27:835–844. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddad P, Sharma S. Adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics: differential risk and clinical implications. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:911–936. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of 3 211 768 patients and 113 383 368 controls. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:163–180. doi: 10.1002/wps.20420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor M, Perera U. NICE CG178 psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management—an evidence-based guideline? Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206:357–359. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.155945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison AP, Birchwood M, Pyle M. Impact of cognitive therapy on internalised stigma in people with at-risk mental states. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203:140–145. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.123703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison AP, Turkington D, Pyle M. Cognitive therapy for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders not taking antipsychotic drugs: a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1395–1403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldsmith LP, Lewis SW, Dunn G, Bentall RP. Psychological treatments for early psychosis can be beneficial or harmful, depending on the therapeutic alliance: an instrumental variable analysis. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2365–2373. doi: 10.1017/S003329171500032X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison AP. The interpretation of intrusions in psychosis: an integrative cognitive approach to hallucinations and delusions. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2001;29:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison AP. A manualised treatment protocol to guide delivery of evidence-based cognitive therapy for people with distressing psychosis: learning from clinical trials. Psychosis. 2017;9:271–281. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackburn IM, James I, Milne D, Baker CA, Standart S, Garland A. The revised cognitive therapy scale (CTS-R): psychometric properties. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2001;29:431–446. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay S, Fiszbein A, Opler L. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Quality of Life Group The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569–1585. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social funtioning. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;101:323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Law H, Neil ST, Dunn G, Morrison AP. Psychometric properties of the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR) Schizophr Res. 2014;156:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guy W. US Department of Heath, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; Rockville: 1976. Assessment manual for psychopharmacology. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohlsen R, Williamson R, Yusufi B. Interrater reliability of the Antipsychotic Non-Neurological Side-Effects Rating Scale measured in patients treated with clozapine. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:323–329. doi: 10.1177/0269881108091069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat Med. 1995;14:1933–1940. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Law H, Carter L, Sellers R. A pilot randomised controlled trial comparing antipsychotic medication, to cognitive behavioural therapy to a combination of both in people with psychosis: rationale, study design and baseline data of the COMPARE trial. Psychosis. 2017;9:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little RJA, Rubin DB. John Wiley and Sons; London: 2002. Statistical analysis with missing data. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leucht S, Kissling W, Davis JM. The PANSS should be rescaled. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:461–462. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO. Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1050–1060. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leucht S, Kane JM, Etschel E, Kissling W, Hamann J, Engel RR. Linking the PANSS, BPRS, and CGI: clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31:2318–2325. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thwin SS, Hermes E, Lew R. Assessment of the minimum clinically important difference in quality of life in schizophrenia measured by the Quality of Well-Being Scale and disease-specific measures. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermes EDA, Sokoloff DM, Stroup TS, Rosenheck RA. Minimum clinically important difference in the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale using data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:526–532. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whale R, Harris M, Kavanagh G. Effectiveness of antipsychotics used in first-episode psychosis: a naturalistic cohort study. BJPsych Open. 2016;2:323–329. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.002766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnes TR. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:567–620. doi: 10.1177/0269881110391123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O'Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:686–693. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.