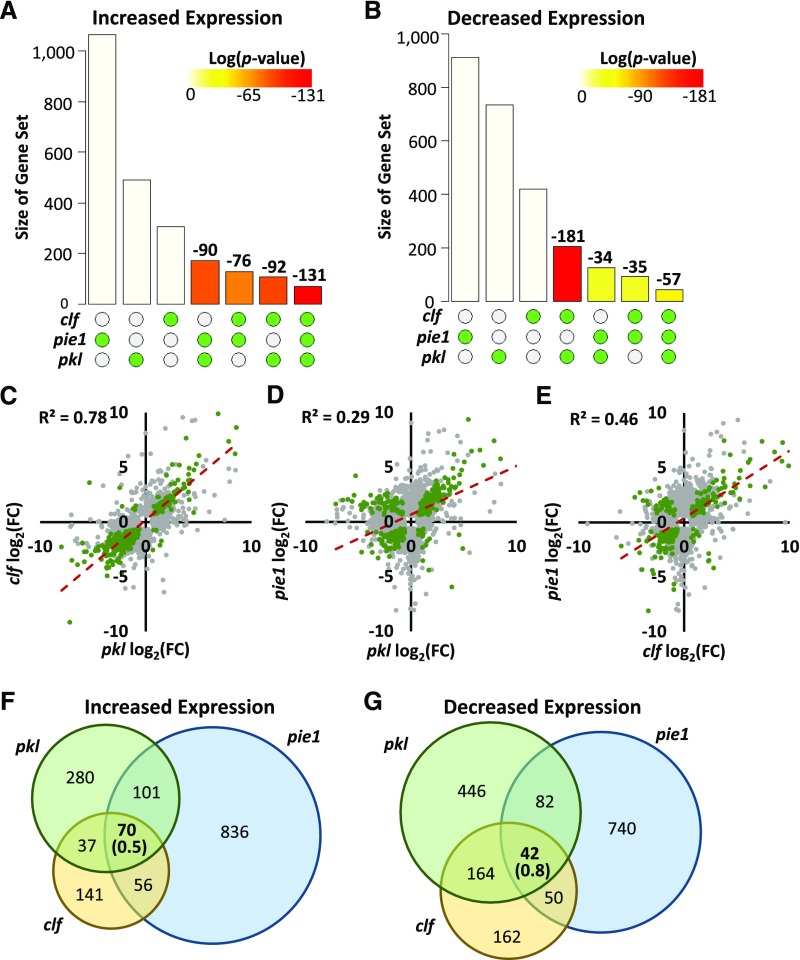

The chromatin remodelers PKL and PIE1 and the histone methyltransferase CLF act in an epigenetic pathway that promotes and maintains the repressive epigenetic modification H3K27me3 in Arabidopsis.

Abstract

Selective, tissue-specific gene expression is facilitated by the epigenetic modification H3K27me3 (trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3) in plants and animals. Much remains to be learned about how H3K27me3-enriched chromatin states are constructed and maintained. Here, we identify a genetic interaction in Arabidopsis thaliana between the chromodomain helicase DNA binding chromatin remodeler PICKLE (PKL), which promotes H3K27me3 enrichment, and the SWR1-family remodeler PHOTOPERIOD INDEPENDENT EARLY FLOWERING1 (PIE1), which incorporates the histone variant H2A.Z. Chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing and RNA-sequencing reveal that PKL, PIE1, and the H3K27 methyltransferase CURLY LEAF act in a common gene expression pathway and are required for H3K27me3 levels genome-wide. Additionally, H3K27me3-enriched genes are largely a subset of H2A.Z-enriched genes, further supporting the functional linkage between these marks. We also found that recombinant PKL acts as a prenucleosome maturation factor, indicating that it promotes retention of H3K27me3. These data support the existence of an epigenetic pathway in which PIE1 promotes H2A.Z, which in turn promotes H3K27me3 deposition. After deposition, PKL promotes retention of H3K27me3 after DNA replication and/or transcription. Our analyses thus reveal roles for H2A.Z and ATP-dependent remodelers in construction and maintenance of H3K27me3-enriched chromatin in plants.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to establish and maintain distinct chromatin states in eukaryotes allows genetically identical cells to express different sets of genes and thereby differentiate. Different chromatin states are associated with enrichment of specific epigenetic marks including histone variants, histone tail posttranslational modifications, and DNA methylation. In Arabidopsis thaliana, genome-wide analyses have identified nine chromatin states based on enrichment of 16 epigenetic marks (Sequeira-Mendes et al., 2014). How chromatin states are both constructed and maintained, particularly in dividing cells, is unclear.

Chromatin states associated with silencing of tissue-specific genes are commonly enriched for the repressive histone tail modification trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) (Lafos et al., 2011). In Arabidopsis, loss of H3K27me3 results in derepression of lineage-specific genes, failed development, and progressive degeneration into a disorganized callus (Bouyer et al., 2011). H3K27me3 is thought to silence gene expression in combination with other epigenetic machinery by excluding activating epigenetic marks and by promoting a condensed chromatin environment that is refractory to transcription (Aranda et al., 2015; Del Prete et al., 2015). Deposition of H3K27me3 is catalyzed by the Enhancer of zeste [E(z)] family of histone methyltransferases that are components of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) (Margueron and Reinberg, 2011; Kim and Sung, 2014; Khan et al., 2015; Mozgova et al., 2015). CURLY LEAF (CLF), MEDEA (MEA), and SWINGER (SWN) are the three E(z) family members in Arabidopsis (Mozgova et al., 2015). These enzymes function in distinct PRC2 complexes and deposit H3K27me3 within differing subsets of genes during different stages of development (de Lucas et al., 2016). MEA contributes to imprinted gene expression in the endosperm and is necessary for seed viability, whereas CLF and SWN cooperatively promote tissue identity in seedlings and adult plants. Seedlings lacking both CLF and SWN degenerate into callus (Chanvivattana et al., 2004; Müller-Xing et al., 2014) reminiscent of plants in which H3K27me3 deposition is abolished (Bouyer et al., 2011).

Three of the nine characterized chromatin states in Arabidopsis exhibit strong H3K27me3 enrichment (Sequeira-Mendes et al., 2014), corresponding to approximately 17% of genes in 10-d-old seedlings (Zhang et al., 2007). Notably, these chromatin states are also enriched for the histone variant H2A.Z (Sequeira-Mendes et al., 2014), which plays a role in making chromatin dynamic (Subramanian et al., 2015). In particular, genome-wide characterization of H2A.Z enrichment in yeast and animals reveals that the transcription start sites (TSSs) of many genes are enriched for H2A.Z, where it is thought to reduce the energy requirement for RNA polymerase II to pass the +1 nucleosome during transcription (Weber et al., 2014; Subramanian et al., 2015). H2A.Z also has been linked to a variety of processes related to gene expression where it is thought to alter nucleosome composition, modification state, and/or stability and thereby alter nucleosome dynamics and chromatin accessibility (Subramanian et al., 2015). For example, H2A.Z facilitates nucleosome depletion and binding of the transcription factor Foxa2 to its targets during mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation (Li et al., 2012). Notably, H3K27me3 and H2A.Z colocalize at bivalent TSS in mouse and human embryonic stem cells (Ku et al., 2012), which are poised to be repressed or activated. In contrast, H2A.Z is absent from H3K27me3-enriched promoters that are stably repressed (Ku et al., 2012). In Arabidopsis, H2A.Z is enriched in the TSS of many genes as was observed in yeast and animals (Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012). In addition, H2A.Z is enriched in the bodies of many genes associated with stimulus response, where its presence correlates with reduced expression and is necessary for normal transcriptional induction of these loci in response to environmental and developmental cues (Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012). These studies suggest that H2A.Z enrichment in the gene body in plants both enables transcriptional activation in the presence of the appropriate stimulus and contributes to transcriptional repression in the absence of appropriate inductive signals.

The molecular machinery associated with incorporation of H2A.Z into chromatin has been characterized in yeast and animals and to a lesser extent in plants. The SWR1 class of ATP-dependent remodelers is named after Swr1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which incorporates H2A.Z into nucleosomes as part of a multisubunit complex via histone dimer exchange (Krogan et al., 2003; Mizuguchi et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2009). The animal SWR1 family member SRCAP is a subunit of a similar complex that also promotes incorporation of H2A.Z (Ruhl et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2009; Morrison and Shen, 2009). In Arabidopsis, incorporation of H2A.Z is promoted by the SWR1-family chromatin remodeler PHOTOPERIOD INDEPENDENT EARLY FLOWERING1 (PIE1), which likely also functions as a subunit of a complex that is similar to the yeast and animal SWR1/SRCAP-containing complexes (Noh and Amasino, 2003; Choi et al., 2005; Deal et al., 2005, 2007; March-Díaz et al., 2007; Bieluszewski et al., 2015). Loss of PIE1 results in phenotypes that are consistent with those of Swr1p-related remodelers and H2A.Z in animals and yeast such as deficiencies in DNA damage responses (Shaked et al., 2006; Rosa et al., 2013). In addition, pie1 plants exhibit defects in transcriptional regulation of genes in stimulus response pathways including effector-triggered immunity (Berriri et al., 2016). Such gene expression defects are consistent with the observation that H2A.Z contributes to proper transcriptional regulation of genes that are responsive to environmental or developmental cues (Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012). pie1 plants do not fully phenocopy seedlings severely depleted in H2A.Z (March-Diaz et al., 2008; Berriri et al., 2016), suggesting that other factors can contribute to deposition of H2A.Z or that PIE1 has additional roles beyond promoting H2A.Z deposition. Taken together, these studies raise the prospect that PIE1 and/or H2A.Z contribute to transcriptional regulation of H3K27me3-enriched loci, particularly given that such loci are likely to be enriched for H2A.Z in the gene body and are developmentally regulated.

Another ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler that is strongly associated with epigenetic control of gene expression in Arabidopsis is the chromodomain helicase DNA binding (CHD)-family remodeler PICKLE (PKL) (Ho et al., 2013). PKL facilitates H3K27me3-related gene expression during multiple developmental processes (Zhang et al., 2008, 2012, 2014; Jing et al., 2013), and loss of PKL results in reduced levels of H3K27me3 at numerous loci (Zhang et al., 2008). However, the mechanism by which PKL promotes H3K27me3 is unknown. We undertook a candidate-based reverse genetic approach that identified a strong genetic interaction between PKL and PIE1. Subsequent RNA-seq analysis revealed that PKL, PIE1, and CLF act in a common gene expression pathway. Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis revealed that H3K27me3-enriched genes are a subset of H2A.Z-enriched genes and that PIE1 acts with PKL and CLF to promote H3K27me3 at a common set of genes. These findings suggest that H2A.Z facilitates deposition of H3K27me3 at these loci. Biochemical characterization of PKL reveals that it promotes formation of mature nucleosomes from prenucleosomes, suggesting a role for PKL in retention of H3K27me3 rather than deposition. Our combined analyses support the existence of a new epigenetic pathway that contributes to both generation and maintenance of H3K27me3-enriched chromatin in plants.

RESULTS

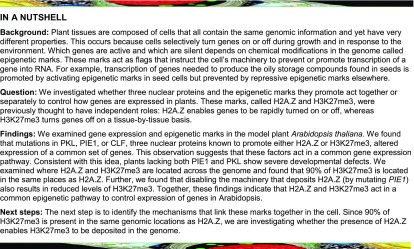

PKL and PIE1 Exhibit a Genetic Interaction

To investigate the possibility that other factors work with PKL to promote development, we undertook a candidate-based reverse genetic approach and examined the phenotype of plants that carried different mutant alleles of PKL and PIE1, which encodes another epigenetic factor. One of these lines, with concurrent impairment of PKL and PIE1 gene function, exhibited severe developmental defects (Figure 1). Due to the poor fertility of homozygous pie1 plants (March-Diaz et al., 2008), this genetic interaction was characterized using the segregating F3 progeny of pkl-10 pie1-5/PIE1 plants. We observed a pronounced developmental delay in 25% of the F3 seedlings, consistent with Mendelian segregation of a recessive trait. Compared with wild-type, pie1-5, and pkl-10 seedlings (Figures 1A to 1C), these seedlings exhibited sharply reduced or absent organogenesis from both the root and shoot meristems (Figure 1D). PCR analysis revealed that 10 out of 10 seedlings exhibiting the severe phenotype were homozygous for pie1-5, whereas 0 out of 10 seedlings exhibiting organogenesis was homozygous for pie1-5.

Figure 1.

pkl-10 pie1-5 Seedlings Exhibit Profound Defects in Organogenesis.

Seedlings were grown on MS medium under 24-h light and images were collected at 2 weeks of age. Background colors are desaturated for visual clarity. Bar = 2 mm.

(A) Representative wild-type seedling.

(B) Representative pkl-10 seedling exhibiting the characteristic reduced petiole length and rosette diameter.

(C) Representative pie1-5 seedilng.

(D) Representative pkl-10 pie1-5 seedling.

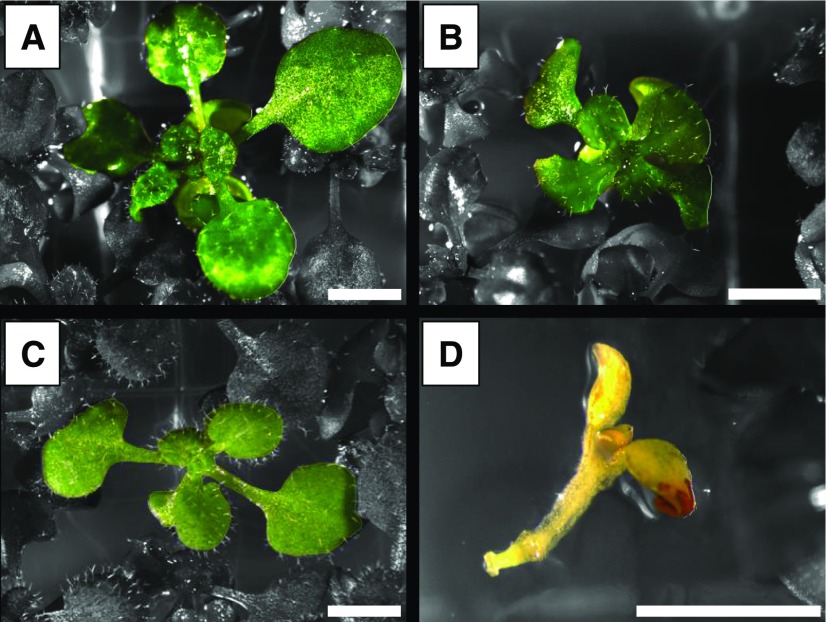

PKL, PIE1, and CLF Act in a Common Gene Expression Pathway

The severe synthetic phenotypes of pkl-10 pie1-5 seedlings suggested that PKL and PIE1 affect expression of a common subset of genes. To examine this possibility, we undertook RNA-seq analysis of wild-type, pkl-1, and pie1-5 shoot tissue using three independent biological replicates for each genotype (ENCODE, 2016). As a comparative control for pkl-1 plants, we included plants defective in CLF, which encodes a histone methyltransferase that promotes trimethylation of H3K27 (Schubert et al., 2006; Schmitges et al., 2011). Sample quality was assessed using plots generated with the DESeq2 and limma packages in Bioconductor (Supplemental Figure 1) (Love et al., 2014; Ritchie et al., 2015). In total, approximately 700 to 2000 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified for each sample (Figure 2; Supplemental Data Set 1).

Figure 2.

Summary of Differentially Expressed Genes.

Total numbers of genes identified as differentially expressed relative to the wild type in the indicated samples. Gene sets corresponding to statistically significant increases in expression are shaded yellow, and those corresponding to significant decreases in expression are shaded blue. Differential expression was determined based on mean counts per million using the edgeR package with a Benjamini-Hochberg FDR threshold of <0.05 and a fold change threshold of ≥1.5-fold change relative to the wild type.

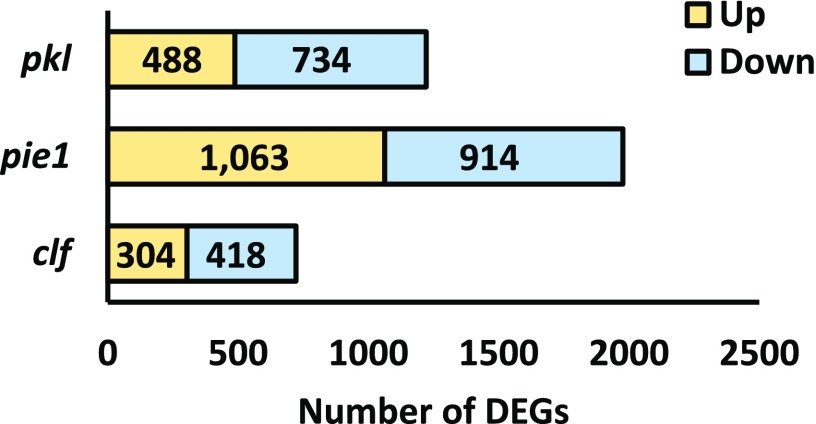

We analyzed the intersections between sets of DEGs to determine if the various mutants exhibited significant overlap in gene expression outcomes (Figures 3A and 3B). Consistent with their common role in promoting H3K27me3, we observed that the intersections between DEGs in clf-28 and in pkl-1 are significantly larger than predicted by chance. Based on the synthetic phenotypes of the pkl-10 pie1-5 seedlings, we hypothesized that the intersection between DEGs in pkl-1 and pie1-5 would also exhibit significant overlap. We observed statistically significant intersections not only between pie1-5 and pkl-1 but also, surprisingly, between pie1-5 and clf-28. In contrast, intersections between DEG sets that are differentially expressed in opposite directions were not significant (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 3.

pkl, pie1, and clf Affect Expression of Common Sets of Genes.

(A) and (B) Statistical analysis of intersections between sets of DEGs exhibiting increased (A) or decreased (B) expression in the indicated mutants relative to the wild type. Gene sets are ordered by size. y axes indicate the size of the indicated gene set (first three columns) or intersection in number of genes. Bars are shaded to reflect the P value of the intersection obtained using Fisher’s exact test with a null hypothesis of an intersection no greater than predicted by chance. Column end labels indicate the log(P value) for the indicated intersection. Data visualization was performed using the SuperExactTest package in Bioconductor (Wang et al., 2015).

(C) to (E) Correlation between expression of DEGs in the indicated genotypes. Axes indicate fold change in expression relative to wild-type plants on a log2 scale. Green points represent genes that are differentially expressed in both genotypes, and gray points represent genes that are differentially expressed in one of the two genotypes. Dotted lines depict linear-fit trendlines of the stated R2 value calculated using common DEGs (green points).

(F) and (G) Diagrams of the three-way intersections from (A) and (B). Numbers in parentheses indicate the size of the intersection predicted by chance (the product of the probabilities of a gene being in each group * population size).

To further investigate whether pkl-1, clf-28, and/or pie1-5 have common effects on gene expression, we examined the correlation between differential expression of genes in each mutant using linear regression. This analysis revealed varying degrees of correlation for each pairwise combination (Figures 3C to 3E). DEGs in pkl-1 and clf-28 plants exhibited a high level of correlation (R2 = 0.78), whereas DEGs in pkl-1 and pie1-5 plants were only weakly correlated (R2 = 0.29). A moderate correlation was also present between DEGs in clf-28 and pie1-5 plants (R2 = 0.46). Identification of pairwise interactions between DEGs in all three of these mutants raised the prospect that PKL, CLF, and PIE1 act in a common pathway. To explore this possibility, we examined the three-way intersections between DEGs exhibiting increased or decreased expression in pkl-1, pie1-5, and clf-28 plants (Figures 3F and 3G). These intersections were much larger than predicted by chance both for DEGs with increased expression (70 observed versus 0.5 predicted, P < 10−130) and for DEGs with decreased expression (42 observed versus 0.8 predicted, P < 10−57), revealing that impairment of PKL, PIE1, or CLF gene function altered expression of a common subset of genes. Taken together, these analyses indicate that PKL, PIE1, and CLF act in one or more common gene expression pathways.

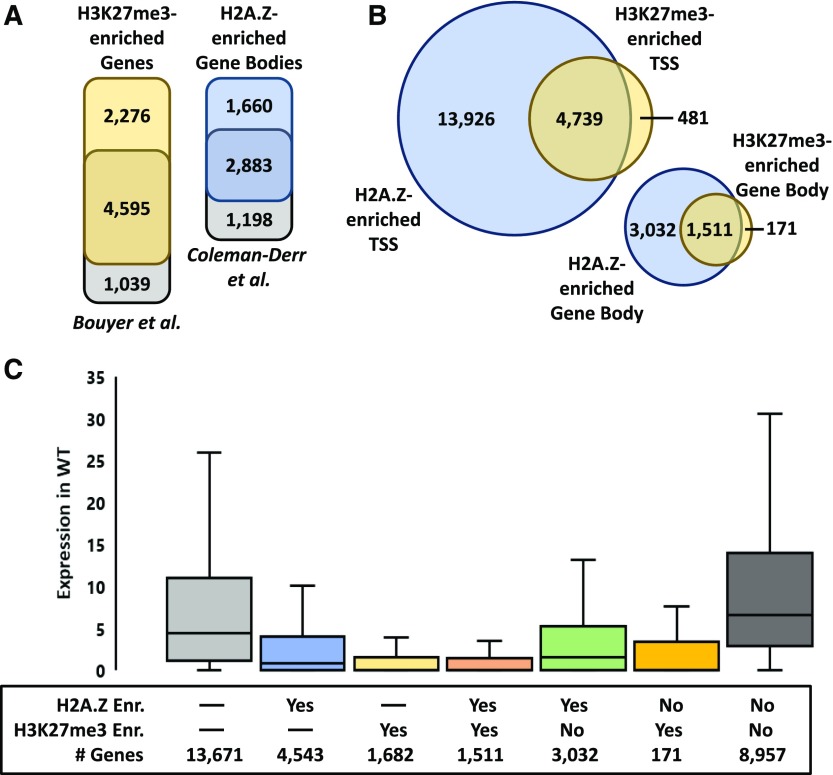

H3K27me3-Enriched Genes Are Largely a Subset of H2A.Z-Enriched Genes

PKL, PIE1, and CLF have been linked to distinct epigenetic pathways. CLF and PKL promote the repressive epigenetic modification H3K27me3, whereas PIE1 promotes incorporation of the histone variant H2A.Z in chromatin (Schubert et al., 2006; Deal et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008). The observation that PKL, PIE1, and CLF affect expression of a common subset of genes raised the prospect that these factors might additionally contribute to one or more common epigenetic pathways. We performed ChIP-seq analysis on wild-type, pkl-1, clf-28, and pie1-5 shoot tissues using two independent biological replicates for each genotype (ENCODE, 2017) to examine the effects of these mutations on levels of H3K27me3 and H2A.Z in chromatin. The sets of genes identified as enriched for H3K27me3 or H2A.Z in wild-type plants exhibited a high degree of overlap with enriched gene sets from previous analyses (Figure 4A) (Bouyer et al., 2011; Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012). Interestingly, we observed that genes enriched for H3K27me3 were almost exclusively a subset of genes enriched for H2A.Z both at the TSS and in the gene body (Figure 4B, regions defined in the Figure 4 legend). Only approximately 10% of H3K27me3-enriched genes were not also identified as H2A.Z-enriched. Furthermore, genes that were coenriched for H2A.Z and H3K27me3 exhibited a lower level of expression on average than genes enriched for only one of these marks (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

H3K27me3 and H2A.Z Exhibit Coenrichment and Are Associated with Low Levels of Gene Expression.

Genes enriched for H3K27me3 and H2A.Z were identified relative to H3 using SICER (Xu et al., 2014).

(A) Diagrams of intersections between gene sets determined to be enriched for H3K27me3 or H2A.Z in the gene body relative to H3 in our analysis versus previously published analyses (Bouyer et al., 2011; Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012). Gene body is defined as the central region of genes that remain after omitting the terminal 1000-bp ends from the TSS and the transcription termination site as annotated in the Araport11 reference genome. Genes shorter than 2.1 kb are thus excluded (Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012).

(B) Diagrams of intersections between genes enriched for H2A.Z and/or in H3K27me3 relative to H3 in the TSS (upper left) or in the gene body (lower right). TSS is defined as the first 500 bp (from base 0 to base +500) from the start of the mRNA sequence. Genes shorter than 500 bp are excluded.

(C) Box-and-whisker plot depicting the distributions of gene expression for genes enriched in the gene body in varying combinations of H2A.Z and/or H3K27me3 as indicated. The y axis represents mRNA mean counts per million values in wild-type plants. Dashes indicate that all genes were included in the set regardless of enrichment status of the indicated mark.

PIE1 Promotes H3K27me3

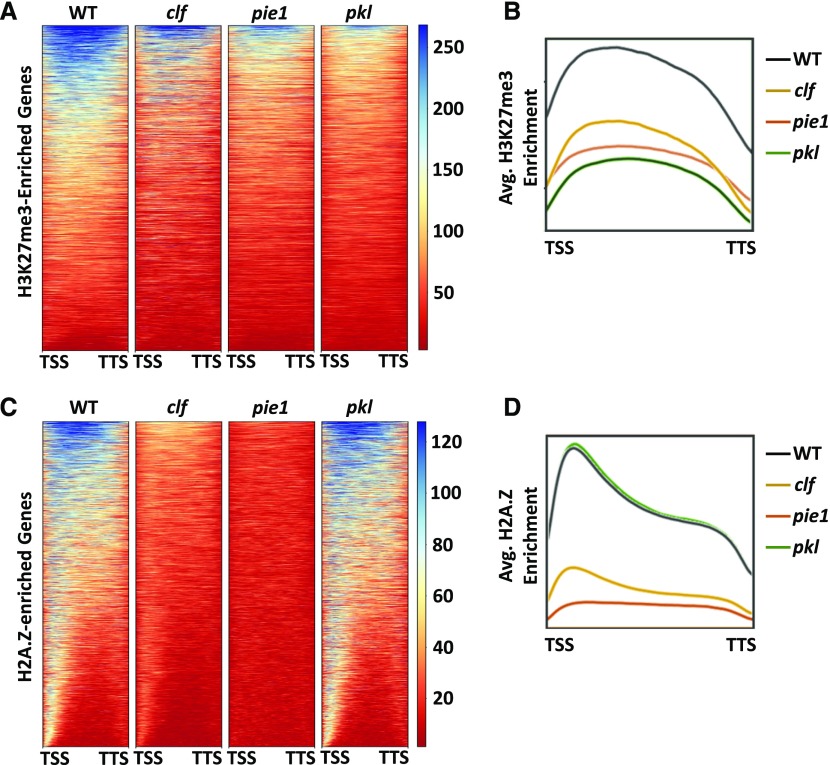

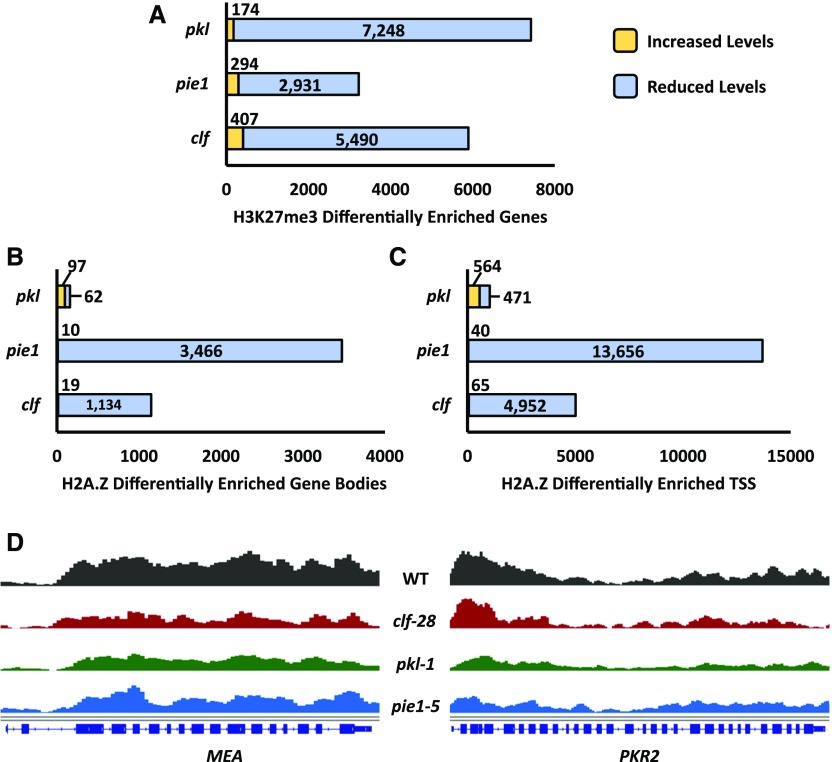

Heat maps were generated to visualize enrichment of H3K27me3 and H2A.Z in wild-type, pkl-1, clf-28, and pie1-5 chromatin (Figure 5). Examination of global levels of H3K27me3 enrichment relative to the wild type reveals a reduction in average levels of this modification not only in pkl-1 and clf-28 plants as predicted (Schubert et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008; Schmitges et al., 2011), but also in pie1-5 plants (Figures 5A and 5B). Loss of PKL had the largest effect on the average level of H3K27me3, with enrichment in pie1-5 plants falling somewhere between clf-28 and pkl-1 plants. Analysis of genes found to be differentially enriched for H3K27me3 in the various mutants relative to the wild type confirmed the major role played by PKL in promoting this mark: over 7200 loci (92% of H3K27me3-enriched genes) exhibited some reduction in H3K27me3 enrichment in pkl-1 plants versus approximately 5500 in clf-28 plants (Figure 6A). Furthermore, approximately 2900 genes exhibited reduced H3K27me3 in pie1-5 plants, confirming that PIE1 promotes H3K27me3 at numerous loci. Many genes exhibiting reduced H3K27me3 did so throughout the coding sequence in each of the lines (Figures 5A, 5B, and 6D). Importantly, transcript levels of known PRC2 subunits were not significantly altered in the pie1-5 mutant relative to the wild type (Supplemental Table 2), indicating that the effect of ablation of PIE1 on H3K27me3 levels is not due to decreased expression of genes encoding PRC2 machinery.

Figure 5.

H3K27me3 and H2A.Z Enrichment Patterns in the Wild Type, clf-28, pie1-5, and pkl-1.

Enrichment visualizations generated using the deepTools2 package (Ramírez et al., 2016). Gene regions are scaled to 1 kb on the x axes. Samples were normalized using the RPKM method. Displayed genes are restricted to those that contain at least one region of enrichment of the relevant mark relative to H3 as determined by SICER. Data are representative of two independent biological replicates.

(A) Heat maps of H3K27me3 enrichment in the indicated genetic backgrounds.

(B) Metagene profile of average enrichment data from (A).

(C) Heat maps of H2A.Z enrichment in the indicated genetic backgrounds.

(D) Metagene profile of average enrichment data from (C).

Figure 6.

Summary of Differentially Enriched Genes.

(A) to (D) Summary of differentially enriched genes identified for each mutant line. Differential enrichment was determined relative to H3 using SICER-df (Xu et al., 2014). Differentially enriched gene sets were filtered to contain only genes identified as such in both of two biological replicates.

(A) Summary of genes identified as differentially enriched relative to the wild type for H3K27me3.

(B) Summary of genes identified as differentially enriched relative to the wild type for H2A.Z in the gene body.

(C) Summary of genes identified as differentially enriched relative to the wild type for H2A.Z at the TSS. The gene body and TSS data sets are described in the Figure 4 legend.

(D) Two representative H3K27me3-enriched genes that exhibit reduced levels of H3K27me3 in the indicated genetic backgrounds. Displayed bigwig tracks were normalized using the RPKM method of deepTools2 and visualized using IGV (Robinson et al., 2011). Data are representative of two independent biological replicates.

Analysis of relative levels of H2A.Z enrichment revealed distinct roles for PIE1, CLF, and PKL in promoting H2A.Z compared with H3K27me3. We observed enrichment of H2A.Z in the 5′ region of many genes and throughout the body of a subset of these genes in wild-type plants (Figures 5C and 5D). As predicted based on precedent (Deal et al., 2007), loss of PIE1 resulted in a drastic reduction in the average levels of H2A.Z enrichment (Figures 5C and 5D). In particular, we observed that the 5′ peak of H2A.Z was dramatically reduced in the pie1-5 line, revealing that preferential enrichment of H2A.Z observed at the TSS of genes is largely a PIE1-dependent phenomenon. Surprisingly, clf-28 plants also exhibited reduced H2A.Z, although to a lesser degree than was observed in pie1-5. Furthermore, a peak of H2A.Z enrichment at the TSS of genes was maintained in clf-28 plants in contrast to its loss in pie1-5 plants, indicating that clf-28 affects enrichment of H2A.Z in a different manner than pie1-5. In contrast, loss of PKL had a negligible effect on global levels of H2A.Z. Identification of individual genes with significantly reduced enrichment of H2A.Z either at the TSS or in the gene body confirms widespread reductions in H2A.Z levels in pie1 and clf plants (Figures 6B and 6C; Supplemental Data Set 1), although loss of PIE1 affects H2A.Z enrichment at many more genes. In total, 73% of identified H2A.Z-enriched TSSs (13,656 genes) were significantly reduced for H2A.Z in pie1-5 plants. The extent of the defect in levels of H2A.Z in pie1 plants is consistent with previous characterization suggesting that PIE1 promotes H2A.Z genome-wide (Deal et al., 2007; Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012). However, the sizable number of loci that do not exhibit PIE1-dependent levels of H2A.Z also provides support for the hypothesis that other factors in addition to PIE1 promote deposition of H2A.Z (Deal et al., 2007).

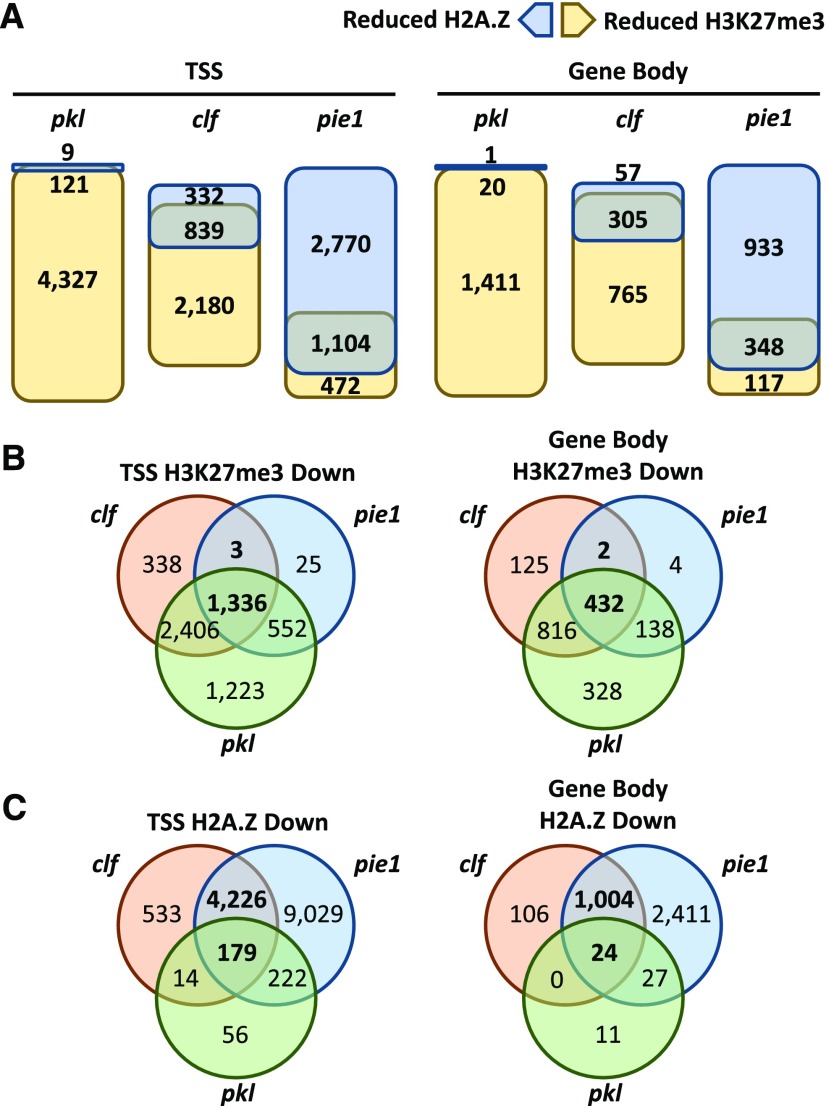

To determine if reductions in H3K27me3 and H2A.Z in pkl-1, pie1-5, and clf-28 were correlated, we examined intersections between gene sets that exhibited reduced levels of the marks in these mutants relative to wild-type plants (Figure 7A). In pie1-5 and clf-28 plants, we observed that a reduction in one mark was often correlated with a reduction in the other. These correlations raised the possibility that these marks are mutually reinforcing, namely, that reduction of H3K27me3 in pie1-5 plants could result from loss of H2A.Z, and reduction of H2A.Z levels in clf-28 plants could result from loss of H3K27me3. Alternatively, either or both of these interactions could be indirect. To investigate these possibilities, we examined if reductions in the noncanonical marks (H3K27me3 for pie1-5 and H2A.Z for clf-28) were correlated with the presence of the canonical marks (H2A.Z for pie1-5 and H3K27me3 for clf-28) at a locus. For genes that exhibit PIE1-dependent H3K27me3, we found that 86% of the genes that exhibited decreased H3K27me3 in pie1-5 plants were enriched for H2A.Z, and 65% simultaneously exhibited decreased H2A.Z. Thus, both the presence of H2A.Z and pie1-dependent loss of H2A.Z were associated with loss of H3K27me3 in pie1-5 plants, supporting the idea that loss of H3K27me3 was a direct result of loss of H2A.Z in pie1-5 plants. Based on these analyses and on the observation that H3K27me3-enriched genes were largely a subset of H2A.Z-enriched genes (Figure 4), we propose that PIE1 is a component of an epigenetic pathway that directly promotes H3K27me3 via its ability to promote H2A.Z.

Figure 7.

Intersection Analysis of Differentially Enriched Gene Sets.

(A) Diagrams of intersections between gene sets exhibiting reduced levels of H3K27me3 and those exhibiting reduced levels of H2A.Z in the indicated mutant lines. Genes were limited to those enriched for both epigenetic marks for this analysis.

(B) Venn diagrams depicting the intersections among gene sets exhibiting reduced H3K27me3 in the indicated mutant lines at the TSS (left) or in the gene body (right).

(C) Venn diagrams depicting the intersections among gene sets exhibiting reduced H2A.Z in the indicated mutant lines at the TSS (left) or in the gene body (right).

A similar analysis suggests that CLF and/or H3K27me3 are unlikely to be directly required for deposition of H2A.Z. In contrast to the strong correlation between loss of H3K27me3 and loss of H2A.Z in pie1-5 plants, clf-28 plants exhibit a much weaker association between loss of H2A.Z and status of H3K27me3. A metagene profile of H2A.Z levels in clf-28 does not reveal preferential loss of H2A.Z at H3K2me3-enriched genes (Supplemental Figure 2). Only 23% of genes exhibiting reduced H2A.Z in clf-28 are enriched for H3K27me3 (P value > 0.94 by Fisher’s exact test), indicating that loss of H2A.Z occurs via a H3K27me3-independent mechanism. In addition, pkl-1 plants exhibit broadly reduced H3K27me3 levels without a concurrent reduction in H2A.Z indicating that wild-type levels of H3K27me3 are generally not necessary for wild-type levels of H2A.Z (Figures 5C, 5D, 6B, and 6C). Finally, we are unaware of any biochemical data in the literature that directly links E(z) histone methyltransferases to incorporation of H2A.Z. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that loss of H2A.Z in pie1-5 drives loss of H3K27me3, whereas reductions in H2A.Z levels in clf-28 occur via an uncharacterized mechanism that is not correlated with H3K27me3.

PIE1, CLF, and PKL Act in a Common Epigenetic Pathway to Promote H3K27me3

To determine if CLF, PIE1, and/or PKL promote H3K27me3 at common subsets of genes, we examined three-way intersections of gene sets that exhibited reduced levels of this modification relative to the wild type. Surprisingly, this analysis revealed that the vast majority of genes that exhibited PIE1- or CLF-dependent H3K27me3 were also dependent on PKL (>90% for all intersections examined; Figure 7B). Strikingly, >99% of genes that were both CLF- and PIE1-dependent for H3K27me3 were also PKL-dependent at the TSS and in the gene body, revealing that a large number of genes (1414) require all three epigenetic factors to maintain H3K27me3 levels. Taken together, these data suggest that genes that exhibited PIE1- and CLF-dependent H3K27me3 enrichment were largely (but not entirely) a subset of genes that exhibited PKL-dependent H3K27me3 enrichment and further suggest that these three factors are components of a common epigenetic pathway for a large group of genes. In contrast, there is little evidence that PIE1, CLF, and PKL act in a common pathway to promote H2A.Z. Less than 5% of genes that were both CLF- and PIE1-dependent for H2A.Z were also PKL-dependent at the TSS and in the gene body (Figure 7C).

Altered H3K27me3 Levels Are Associated with Gene Expression Phenotypes in pkl, pie1, and clf Plants

The significant number of common genes that exhibited reduced H3K27me3 levels in pkl-1, pie1-5, and clf-28 raised the possibility that reduced H3K27me3 levels contributed to the correlation in gene expression outcomes in these mutants (Figure 3). In support of this idea, we observed that genes exhibiting reduced H3K27me3 were highly overrepresented among genes that exhibited differential expression in each of the mutants we examined (Table 1), suggesting that loss of H3K27me3 at these loci contributed to altered expression of these genes. In contrast, altered levels of H2A.Z were generally not strongly associated with changes in gene expression in these lines (Table 1). However, genes exhibiting decreased H2A.Z in pie1-5 and clf-28 plants were more likely than predicted by chance to exhibit increased expression. These results are consistent with possibility that altered levels of H3K27me3 and H2A.Z contributed to reduced expression from these loci (Table 1, Figure 4C).

Table 1. Statistical Analysis of Intersections between DEGs and ChIP-Seq Data.

| ChIP-Seq Set | DEG Set | Observed | Predicted | Log(P Value) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 up in pkl | Up in pkl | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| H3K27me3 down in pkl | Up in pkl | 109 | 50 | −15 | ** |

| H3K27me3 up in pkl | Down in pkl | 2 | 4 | −1 | |

| H3K27me3 down in pkl | Down in pkl | 162 | 75 | −22 | *** |

| H3K27me3 up in pie1 | Up in pie1 | 11 | 8 | −1 | |

| H3K27me3 down in pie1 | Up in pie1 | 107 | 45 | −17 | ** |

| H3K27me3 up in pie1 | Down in pie1 | 8 | 7 | −1 | |

| H3K27me3 down in pie1 | Down in pie1 | 43 | 39 | −1 | |

| H3K27me3 up in clf | Up in clf | 3 | 4 | −1 | |

| H3K27me3 down in clf | Up in clf | 79 | 22 | −24 | *** |

| H3K27me3 up in clf | Down in clf | 20 | 6 | −6 | * |

| H3K27me3 down in clf | Down in clf | 75 | 30 | −13 | ** |

| H2A.Z up in pkl | Up in pkl | 3 | 2 | −1 | |

| H2A.Z down in pkl | Up in pkl | 5 | 1 | −3 | |

| H2A.Z up in pkl | Down in pkl | 12 | 3 | −5 | |

| H2A.Z down in pkl | Down in pkl | 2 | 2 | −1 | |

| H2A.Z up in pie1 | Up in pie1 | 1 | 0.4 | −1 | |

| H2A.Z down in pie1 | Up in pie1 | 226 | 94 | −42 | *** |

| H2A.Z up in pie1 | Down in pie1 | 1 | 0.4 | −1 | |

| H2A.Z down in pie1 | Down in pie1 | 66 | 88 | 0 | |

| H2A.Z up in clf | Up in clf | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | |

| H2A.Z down in clf | Up in clf | 42 | 12 | −13 | ** |

| H2A.Z up in clf | Down in clf | 1 | 0.2 | −1 | |

| H2A.Z down in clf | Down in clf | 19 | 10 | −3 |

Observed intersections between DEGs and differentially enriched genes of the indicated samples. Gene sets were determined relative to the wild type. H2A.Z gene sets are the “gene body” sets defined above. Observed: number of genes in common between the indicated gene sets. Predicted: number of genes predicted to be in common by chance. P value: obtained using Fisher’s exact test with a null hypothesis of an intersection that is no greater than expected by chance. Significance: *α ≤ 10−5, **α ≤ 10−10, and ***α ≤ 10−20.

PKL Is a Prenucleosome Maturation Factor in Vitro

The decreased levels of H3K27me3 observed in pkl-1 plants are consistent with a role for PKL in promoting deposition of the mark (e.g., by working with PRC2) or in promoting retention of the mark (e.g., during replication and/or transcription). pkl-1 seedlings exhibited reduced H3K27me3 levels at >45% more loci than clf-28 seedlings (Figure 6A), suggesting that if PKL promotes deposition of H3K27me3, it does so in concert with multiple PRC2 complexes. However, we previously found that PKL primarily exists as a monomer in vivo (Ho et al., 2013), and immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry experiments do not reveal an association between PKL and subunits of PRC2 (negative data not shown). Based on these observations, we explored the hypothesis that PKL promotes retention of H3K27me3 by playing a role in nucleosome assembly.

Redeposition of nucleosomes after passage of a DNA or RNA polymerase complex has recently been proposed to be a two-step process (Fei et al., 2015). Based on in vitro and in vivo analyses, the histone octamer is first redeposited by a histone chaperone in the form of a conformational isomer referred to as a prenucleosome. Prenucleosome particles comprise an octamer of core histones but occlude a much smaller length of DNA than do nucleosomes in the canonical conformation (Fei et al., 2015). This is followed by maturation of the prenucleosome into a canonical nucleosome by ATP-dependent remodelers. One of the remodelers that was demonstrated to possess prenucleosome maturation activity was CHD1 from Drosophila melanogaster. A high degree of sequence conservation in the ATPase and D domains exists between CHD1 remodelers and PKL, and both of these remodelers are primarily found as monomers in vivo (Lusser et al., 2005; Ho et al., 2013; Fei et al., 2015).

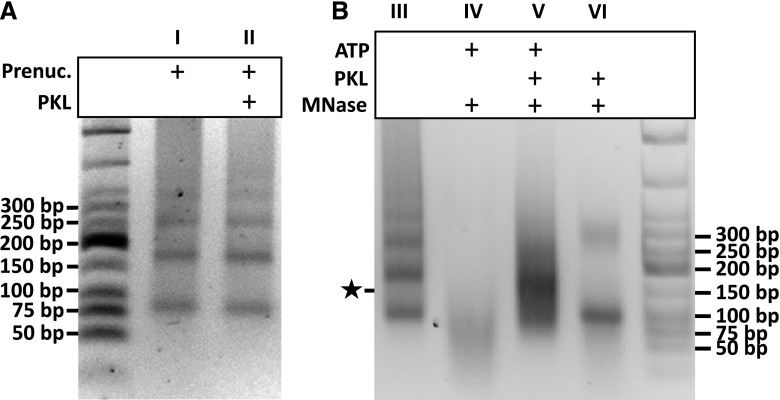

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that PKL similarly possesses prenucleosome maturation activity and that loss of this activity results in reduced levels of H3K27me3 due to defects in chromatin reassembly. To test if PKL possesses prenucleosome maturation activity, we examined the ability of recombinant PKL to mature prenucleosomes in vitro using the nuclease protection assay established by Fei et al. (2015), in which maturation of prenucleosomes into canonical nucleosomes is measured by the appearance of a band that migrates at approximately 147 bp, the DNA occlusion size of a canonical nucleosome core particle. We found that addition of recombinant PKL and ATP did not alter assembly of the poly-prenucleosomal template (Figure 8A). Addition of micrococcal nuclease (MNase) to the polynucleosomal template revealed the presence of prenucleosomes, as indicated by the presence of a band at approximately 80 bp. However, incubation of the template with recombinant PKL and ATP prior to MNase digestion resulted in the appearance of a band slightly shorter than 150 bp, consistent with the size predicted for mature nucleosome particles (Figure 8B, lane V). A similar band was not visible if PKL was incubated with the template in the absence of additional ATP (Figure 8B, lane VI). These results reveal that recombinant PKL possesses ATP-dependent prenucleosome maturation activity in vitro. Furthermore, they are consistent with the possibility that PKL promotes retention of H3K27me3-enriched nucleosomes in the plant by promoting their reassembly after passage of a DNA and/or RNA polymerase, in a fashion that is consistent with the proposed role of CHD1 in promoting retention of H3K36me3 at transcribed genes (Radman-Livaja et al., 2012; Smolle et al., 2012).

Figure 8.

PKL Converts Prenucleosomes into Canonical Nucleosomes.

Prenucleosome maturation assay performed as described previously (Fei et al., 2015). Reaction products were deproteinated and fragments were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis. Bands were visualized using ethidium bromide.

(A) Assembly of poly-prenucleosomal templates (Prenuc.) in the absence (lane I) or presence (lane II) of recombinant PKL. Mono-prenucleosomes were assembled as previously described (Fei et al., 2015), and poly-prenucleosomes were synthesized by ligating the mono-prenucleosomes using T4 DNA ligase and ATP.

(B) Digestion of poly-prenucleosomal templates from panel A (lane III) with MNase, which spares DNA fragments rendered inaccessible due to occlusion by a nucleosome. Prior to digestion, samples were incubated in the absence or presence of recombinant PKL and/or ATP (lanes IV through VI). Generation of mature nucleosomes was assessed by the appearance of approximately 147-bp DNA fragments (indicated with a star) corresponding to the DNA occlusion length of the mature nucleosome core particle.

DISCUSSION

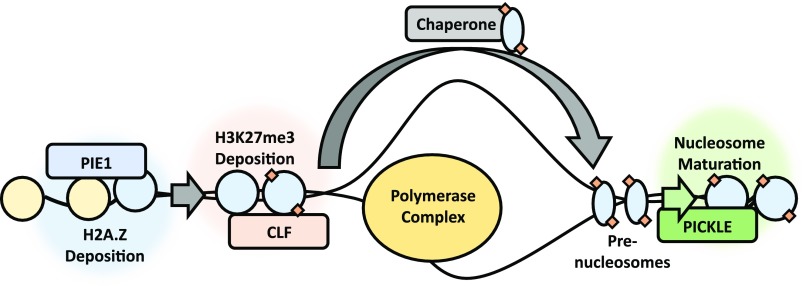

Chromatin states that are strongly enriched for H3K27me3 are also enriched for H2A.Z in Arabidopsis (Sequeira-Mendes et al., 2014). Our data suggest a functional relationship between these epigenetic features, specifically that H2A.Z underwrites H3K27me3 enrichment at many loci. In agreement with this hypothesis, we found that H3K27me3-enriched genes are largely a subset of H2A.Z-enriched genes (Figure 4B). We further observed that PIE1 acts in a common gene expression pathway with CLF and PKL, which are known to contribute to H3K27me3 homeostasis (Figure 3). We also observed that loss of PIE1 resulted not only in a substantial genome-wide decrease in levels of H2A.Z but also in levels of H3K27me3 (Figure 5). Finally, we undertook a biochemical analysis of PKL and found that it possessed prenucleosome maturation activity in vitro, suggesting that potential maturation of H3K27me3-containing prenucleosomes by PKL in vivo helps promote their stability and retention in chromatin (Figure 8).

Based on these analyses, we propose the existence of an epigenetic pathway by which H3K27me3-enriched chromatin states are constructed and maintained in Arabidopsis (Figure 9). In this pathway, generation of H3K27me3-enriched chromatin is dependent on the prior action of PIE1 and H2A.Z. These H2A.Z- and H3K27me3-enriched chromatin domains are subsequently stabilized during DNA replication and/or transcription by the CHD remodeler PKL, which facilitates retention of epigenetic information after chromatin reassembly by promoting maturation of prenucleosomes. In support of these factors acting in a common pathway, our RNA-seq analysis reveals that a common set of genes are dependent on PKL, PIE1, and CLF for expression (Figure 3). We found that the changes in gene expression observed in each mutant are strongly associated with reduced levels of H3K27me3 (Table 1). Notably, previous studies have indicated that H2A.Z enrichment in the gene body contributes to transcriptional repression (Coleman-Derr and Zilberman, 2012; Sura et al., 2017). Our results strongly support a role for H2A.Z in transcriptional repression at these loci in part by contributing to enrichment of H3K27me3 (Figure 6). However, since 82% of genes with reduced H2A.Z in the gene body also exhibit reduced H2A.Z at the TSS in pie1-5 plants, it is difficult to determine whether enrichment specifically at one or both of these regions drives the observed changes in expression and/or H3K27me3 levels.

Figure 9.

Model for H3K27me3 Deposition and Maintenance.

Generation of H3K27me3-enriched chromatin is dependent on the prior action of PIE1 and H2A.Z. PKL acts subsequently to maintain this epigenetic state during DNA replication and/or transcription by facilitating nucleosome retention.

This model provides a simple explanation for the reduced H3K27me3 levels observed in pie1-5 seedlings (Figures 5A, 5B, and 6A): PIE1 indirectly promotes H3K27me3 levels via its role in promoting H2A.Z. This model thus also predicts that deposition of H3K27me3 is dependent on the presence of H2A.Z. There is strong precedent for Arabidopsis H3K27 methyltransferases preferentially acting on nucleosomes that contain specific histone variants. The H3K27 methyltransferases that promote H3K27me1 in Arabidopsis, ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX-RELATED PROTEIN5 (ATXR5) and ATXR6 (Jacob et al., 2009), exhibit much greater activity in vitro in the presence of nucleosomes containing the histone variant H3.1 rather than H3.3 (Jacob et al., 2014). Nucleosomes containing H2A.Z may similarly act as the preferred substrate for Arabidopsis PRC2 complexes. In vitro methylation assays of CLF-containing PRC2 complexes (Schmitges et al., 2011) using recombinant plant nucleosomes containing canonical H2A or H2A.Z would provide a robust test of this prediction.

Although we observed that clf-28 seedlings exhibit reductions in both H2A.Z and H3K27me3 levels (Figures 5 and 6A to 6C), it is unlikely that H2A.Z and H3K27me3 are mutually reinforcing as was previously observed for CMT-dependent DNA methylation and KYP-dependent H3K9 methylation (Jackson et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2007; Du et al., 2012, 2014). Only a fraction of H2A.Z-enriched genes are also enriched for H3K27me3 (Figure 4B), and loss of H2A.Z in clf-28 does not occur preferentially at H3K27me3-enriched genes (Supplemental Figure 2). Additionally, pkl-1 seedlings exhibit broadly reduced H3K27me3 levels without a concurrent reduction in H2A.Z, further indicating that H3K27me3 is not necessary for normal levels of H2A.Z at loci where both marks are present (Figure 5). Analysis of transcript level of genes that exhibit CLF-dependent expression did not reveal machinery known to be involved in deposition of H2A.Z (Supplemental Data Set 1). Thus, the pathway(s) by which loss of CLF perturbs H2A.Z homeostasis remains to be determined.

Previous characterization of double mutant plants that lack these or related genes is consistent with our observations. clf pkl plants largely exhibit additive shoot phenotypes, whereas swn pkl plants exhibit synergistic shoot phenotypes, particularly with regards to traits related to vegetative phase change (Xu et al., 2016). Similarly, characterization of clf pie1 plants reveals additive shoot phenotypes (Noh and Amasino, 2003). The observation of additive shoot phenotypes in clf pie1 and clf pkl plants is consistent with PIE1, CLF, and PKL acting in a common pathway as proposed here. In contrast, the observation of a synergistic phenotype for swn pkl plants raises the prospect that SWN plays a functionally related role outside of the proposed pathway. Analysis of the molecular traits described here (genome-wide levels of H3K27me3 and H2A.Z) in these double mutants is likely to shed additional light into the respective roles of these factors with regards to these epigenetic phenotypes.

A precedent exists for linkage between H2A.Z and Polycomb group-associated phenomena in animals. In female mammalian cells, the majority of H2A.Z incorporated into the silent X chromosome is ubiquitylated by PRC1, raising the prospect that ubiquitylated H2A.Z specifically contributes to formation of transcriptionally repressive facultative heterochromatin in animal cells (Sarcinella et al., 2007). As noted earlier, H3K27me3 and H2A.Z are both present at bivalent transcription start sites in mouse and human embryonic stem cells (Ku et al., 2012). In light of our data, we speculate that H2A.Z might not only play a role in poising the nucleosome to be dynamic (Subramanian et al., 2015) but also in making the nucleosome a more suitable substrate for PRC2. Conversely, the presence of H2A.Z in H3K27me3-repressed chromatin in plants might contribute to the developmental plasticity commonly observed in this kingdom (Xiao et al., 2017) by providing such chromatin with dynamic potential.

Although previous analyses indicated that PKL promotes H3K27me3 (Zhang et al., 2008), the mechanism by which this occurred was unclear. In particular, biochemical characterization of PKL indicated that it primarily exists as a monomer in vivo (Ho et al., 2013), and no evidence has been reported that PKL associates with PRC2 machinery. Our combined analyses provide strong evidence for a novel role for PKL in retention of H3K27me3 rather than in deposition. We find that PKL is required for normal H3K27me3 levels at approximately 30% more loci than CLF (Figure 6), suggesting that it contributes to H3K27me3 promoted by PRC2 complexes containing CLF or SWN. The discovery that PKL promotes maturation of prenucleosomes in vitro (Figure 8) provides a simple explanation for how it can contribute to global homeostasis of H3K27me3: It may act in vivo to promote retention of H3K27me3 after passage of a DNA and/or RNA polymerase. Given that H3K27me3-enriched genes have such low levels of expression (Figure 4C) and thus are rarely disrupted by passage of RNA polymerase, it is more likely that PKL is primarily required to preserve H3K27me3 after passage of a DNA replication fork. Notably, CHD1 and ISWI remodelers also promote maturation of prenucleosomes and have been strongly implicated in nucleosome retention at transcribed loci in S. cerevisiae (Smolle et al., 2012; Fei et al., 2015). Our analyses suggest that PKL, which belongs to a different subfamily of CHD remodelers than CHD1, plays a specialized role in retention of epigenetic states during DNA replication in plants. It remains to be seen if closely related CHD remodelers or some other actors play such a role in animal systems.

In addition to contributing to gene repression, PKL also has been implicated in transcriptional activation of H3K27me3-enriched loci (Zhang et al., 2008, 2014; Jing et al., 2013). In particular, H3K27me3-enriched genes are overrepresented among those genes that exhibit reduced expression in pkl plants. Although our combined characterization of pie1-5, clf-28, and pkl-1 plants reveals pronounced reductions in H3K27me3 and concurrent increased expression of H3K27me3-enriched genes, we also observe a common set of H3K27me3-enriched loci that exhibit decreased expression in each of these mutants. Given previous characterization of CLF and H3K27me3 (Schubert et al., 2006; Mozgova et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016), it is difficult to generate a simple model by which CLF directly contributes to activation of an H3K27me3-enriched locus. In particular, very little evidence exists for a stable chromatin state containing CLF that enables both positive and negative regulation. Instead, given that many H3K27me3-enriched loci are developmentally regulated (Gan et al., 2015; de Lucas et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016), increased expression of formerly repressed H3K27me3-enriched loci in clf-28 plants might lead to an altered developmental context that precludes expression of other loci subject to regulation by H3K27me3. Based on this reasoning and on the significant common sets of genes that exhibit decreased expression in pkl-1, pie1-5, and clf-28 plants (Figure 3G), we propose that the entire set represents an indirect effect of reduced H3K27me3 levels.

The synthetic growth defect of plants carrying null alleles of both PKL and PIE1 strongly suggests that PKL and PIE1 act redundantly to promote at least one chromatin-based event. Loss of PIE1 results in a severe decrease in the level of incorporation of H2A.Z at a number of loci (Deal et al., 2007). Our analyses support a genome-wide role for PIE1 in promoting H2A.Z, particularly at the TSS of genes (Figures 5C and 5D). However, not all loci exhibit significantly decreased levels of H2A.Z in pie1-5, indicating that other factors in addition to PIE1 can promote incorporation of this histone variant, at least at some fraction of the genome. In line with this proposition, we observed that H2A.Z levels were lower in pie1-5 plants at H3K27me3-enriched genes compared with genes that were not enriched for H3K27me3 in the wild type (Supplemental Figure 2). Since H3K27me3 enrichment is correlated with very low transcript levels (Figure 4C), these data raise the possibility that PIE1-independent mechanisms exist that promote incorporation of H2A.Z specifically at actively transcribed genes. These data thus also provide a possible rationale for the previous observation that pie1 plants are not phenotypically equivalent to plants that are severely depleted for H2A.Z (Berriri et al., 2016).

Given that pkl-1 pie1-5 null plants are inviable, it is possible that PKL acts redundantly with PIE1 to promote H2A.Z. In particular, our model predicts that PKL promotes retention of both H3K27me3 and H2A.Z after disruption by a polymerase. In the absence of PIE1, this role for PKL in retention of H2A.Z may be essential for maintaining this histone variant at levels that are conducive to normal chromatin-based processes such as transcription. Given that we only observe loss of H3K27me3 and not H2A.Z in pkl-1 plants, we propose that PIE1 acts subsequently on the resulting replacement nucleosomes in pkl-1 plants to restore H2A.Z.

Our findings support the existence of an epigenetic pathway in which PIE1 promotes incorporation of H2A.Z, which in turn promotes deposition of H3K27me3 by CLF. PKL acts after deposition to promote retention of H3K27me3 by promoting chromatin assembly after DNA replication and/or transcription. These data thus confirm previous observations of H2A.Z and H3K27me3 coenrichment in plants (Sequeira-Mendes et al., 2014) and reveal that this coenrichment is likely to reflect how H3K27me3-enriched chromatin is generated. Given the proposed role for H2A.Z in enabling switching of transcriptional states (Subramanian et al., 2015), it is possible that the presence of H2A.Z in H3K27me3-enriched chromatin also contributes to plasticity of this state and thus also to the developmental plasticity of plants.

In total, our analyses suggest that SWR1 and CHD remodelers play a major role in homeostasis of H3K27me3 in plants and raise the prospect that PKL plays a key role in memory of this epigenetic state. Our results leave open the possibility that PKL also contributes to the maintenance of other epigenetic states. Further functional characterization of these and related remodelers and the corresponding mutants is likely to provide additional insight into the molecular processes underlying maintenance of epigenetic states in plants.

METHODS

Plant Lines and Growth Conditions

All plant lines used in these experiments are in the Columbia background. The previously characterized mutant lines used in this study are pkl-1 (Ogas et al., 1997), pkl-10 (Zhang et al., 2012), pie1-5 (Deal et al., 2007), and clf-28 (Doyle and Amasino, 2009). Phenotypic characterization was performed as described previously (Zhang et al., 2012). Plants used in RNA-seq and ChIP-seq analyses were sown in soil pots, cold-treated for 3 d, and grown for 3 weeks under 18-h 170 µE light at 22°C in a Percival AR75 incubator prior to sample collection. Oligonucleotide primers used to genotype the segregating pie1-5 mutant plants were as follows: 5′-CTGAGGATGAGACCGTGAGT-3′, 5′-AAGGTCATGTGAATGGGTCTC-3′, and 5′-ATTTTGCCGATTTCGGAAC-3′ (SALK LBb1.3 border primer)

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

RNA was extracted from the aerial tissues of 3-week-old seedlings that had not bolted using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen; catalog no. 74903). Three biological replicates from different pools of seedlings were collected for each genotype. RNA samples were DNase treated and concentrated using an RNA Clean and Concentrator kit (Zymo; catalog no. R1013). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using an M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Thermo Fisher; catalog no. 28025013).

Chromatin Extraction

Chromatin extraction was performed on aerial tissues of 3-week-old seedlings that had not bolted using our published protocol (Zhang et al., 2008) with the following modifications: Extraction buffer 2 was replaced with 1 mL of HBM buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 440 mM sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM spermine, 1 mM PMSF, 1 µg/mL pepstatin, and protease inhibitors), IP buffer was replaced with 1 mL of nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 0.25% SDS, and protease inhibitors), centrifugation following sonication was performed at 12,000g for 5 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and diluted to 3 mL using ChIP dilution buffer (1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mM EDTA, 16.7 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 167 mM NaCl) to reduce the SDS concentration below 0.1%. Chromatin samples were stored at −80°C. Two biological replicates from different pools of seedlings were collected for each genotype.

ChIP

ChIP was performed on 500 μL of the diluted chromatin solutions using the published protocol (Zhang et al., 2008) and the following antibodies: anti-H3 (Abcam; catalog no. ab1791), anti-H3K27me3 (Millipore; catalog no. 07-449), and anti-H2A.Z (Deal et al., 2007). The following modifications were made to the protocol: Solutions were rotated at 4°C for 15 h after addition of the antibodies, 20 μL of a 50% slurry of Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher; catalog no. 10004D) equilibrated in ChIP dilution buffer was substituted for the Protein G sepharose slurry, the elution buffer also contained 250 mM NaCl, and the elution time was increased to 30 min at 65°C. After elution, the following steps were performed in lieu of the ones described previously: The samples were cooled to room temperature and treated with 0.1 µg/μL RNase A (Thermo Fisher; catalog no. EN0531) for 15 min at 15°C and subsequently with 0.1 µg/μL proteinase K (Thermo Fisher; catalog no. AM2546) for 15 h at 65°C. The resulting DNA samples were purified using a QIAquick MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen; catalog no. 28004).

Indexing and Sequencing

cDNA library construction was performed using a ThruPLEX DNA-seq kit (Rubicon Genomics). ChIP DNA library construction was performed using an NEB Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit (NEB; catalog no. E7645L). Strand-specific sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq platform.

Differential Expression Analysis

Short reads (approximately 25 million reads per sample) were trimmed of adapter sequences using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014) and mapped to the TAIR10 reference genome assembly using NCBI’s Magic-BLAST utility (NCBI, 2017). The resulting BAM files were assessed for sample quality with plots generated using the DESeq2 and limma packages in Bioconductor (Love et al., 2014; Ritchie et al., 2015). DEGs were identified using the edgeR package in Bioconductor and Fisher’s exact test with a Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate threshold of <0.05 and a fold change threshold of >1.5-fold difference relative to the wild type (Fisher, 1922; Robinson et al., 2010). Gene annotations for differential expression analysis were extracted from the Araport11 genome annotation (Cheng et al., 2017).

Enrichment and Differential Enrichment Analyses

Short reads were trimmed of adapter sequences using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014) and mapped to the TAIR10 reference genome assembly using the very sensitive end-to-end mode of Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). The resulting BAM files (approximately 25 million mapped reads per sample) were converted to BED files using the bamToBed utility of BEDtools2 (Quinlan, 2014). Reads mapping to the mitochondrial or chloroplast genomes were discarded. Regions enriched for H2A.Z or H3K27me3 were identified in wild-type seedlings relative to H3 using SICER (Xu et al., 2014) with a 200-bp window size, a 0.85 effective genome fraction, and a false discovery rate of 0.05. Genic regions (whole genes, gene bodies, or TSS) from the Araport11 annotation that overlapped with at least one region of enrichment were identified using the closestBed utility of BEDtools2. Enrichment in whole genes and in gene bodies was determined using a SICER gap size of 600 bp, whereas enrichment at the TSS was determined using a gap size of 200 bp. Genic regions were required to exhibit overlap with at least one region of enrichment in both biological replicates to be considered enriched. Heat maps of enrichment were generated using the computeMatrix and plotHeatmap utilities in deepTools2 (Ramírez et al., 2016).

Differential enrichment of H2A.Z or H3K27me3 in the various mutants was determined relative to the wild type using SICER-df with H3 as the reference treatment. Parameters used were identical to those listed above with the additions of a fold change threshold of >1.2-fold difference relative to the wild type and a false discovery rate of 0.05 for the wild type versus the mutant. Genic regions were required to overlap with at least one region of differential enrichment in both biological replicates to be considered differentially enriched.

Prenucleosome Maturation Assay

Generation of recombinant PKL was performed as described previously (Ho et al., 2013). Reconstitution of mono-prenucleosomes by salt dialysis and ligation of mono-prenucleosomes to free DNA in the presence of an ATP regeneration system were conducted as described by Fei et al. (2015) using an 80 bp DNA fragment containing a 601 nucleosome positioning sequence. The poly-prenucleosomal templates were diluted 1:1 and incubated with recombinant PKL as described by Fei et al. (2015), with the exception that additional ATP was sometimes omitted from the maturation reaction as indicated in the text. MNase digestion of the assembled nucleosomes was conducted according to Torigoe et al. (2011). Following digestion, the samples (per 50 µL) were deproteinated by mixing with 5 μL of 3 M sodium acetate, pH 5.5, and 55 mg of guanidine HCl and centrifuged through a QIAquick column (Qiagen; catalog no. 28104). The column was washed with 750 μL of PE buffer (Qiagen) and the DNA was eluted from the column using TE buffer. DNA fragments were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 3% agarose gel, and bands were visualized using ethidium bromide as done by Torigoe et al. (2011).

Accession Numbers

RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data from this article can be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus data library under accession number GSE103361. These data include regions of H2A.Z and H3K27me3 differential enrichment and the corresponding statistics, which are provided as processed data files.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Quality assessment of RNA-seq data.

Supplemental Figure 2. Association between H2A.Z levels and H3K27me3 enrichment status.

Supplemental Table 1. Statistical analysis of inverse intersections between clf, pie1, and pkl DEGs.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Lists of genes determined to be differentially expressed (RNA-seq) or differentially enriched (ChIP-seq).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center and the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory for providing the sequence-indexed Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants used in this study. We thank Nadia Atallah for her valuable input with regard to ChIP-seq data analysis. We also thank Craig Peterson for many thoughtful and productive discussions and Nick Carpita for critical insight and feedback. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (MCB-1413183 to J.O.), by HHS National Institutes of Health (GM59770 to J.O.), by Emory University Roger Deal National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371312 to H.Z.), by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFA0503200 to H.Z.), by the Youth Innovation Promotion Association, Chinese Academy of Sciences (to H.Z.), and by HHS NIH National Cancer Institute (P30 CA023168).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.C. was principally responsible for study design, data acquisition and analysis, and manuscript preparation and editing (with J.O.). B.B. and K.K.H. participated in study design and data acquisition. R.H. and W.J. participated in data acquisition and analysis. H.Z., P.E.P., and R.B.D. participated in data analysis and manuscript preparation and editing. J.O. participated in study design, data analysis, and was principally responsible for manuscript preparation and editing (with B.C.).

References

- Aranda S., Mas G., Di Croce L. (2015). Regulation of gene transcription by Polycomb proteins. Sci. Adv. 1: e1500737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriri S., Gangappa S.N., Kumar S.V. (2016). SWR1 chromatin-remodeling complex subunits and H2A.Z have non-overlapping functions in immunity and gene regulation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 9: 1051–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieluszewski T., Galganski L., Sura W., Bieluszewska A., Abram M., Ludwikow A., Ziolkowski P.A., Sadowski J. (2015). AtEAF1 is a potential platform protein for Arabidopsis NuA4 acetyltransferase complex. BMC Plant Biol. 15: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer D., Roudier F., Heese M., Andersen E.D., Gey D., Nowack M.K., Goodrich J., Renou J.P., Grini P.E., Colot V., Schnittger A. (2011). Polycomb repressive complex 2 controls the embryo-to-seedling phase transition. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanvivattana Y., Bishopp A., Schubert D., Stock C., Moon Y.H., Sung Z.R., Goodrich J. (2004). Interaction of Polycomb-group proteins controlling flowering in Arabidopsis. Development 131: 5263–5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C.Y., Krishnakumar V., Chan A.P., Thibaud-Nissen F., Schobel S., and Town C.D. (2017). Araport11: a complete reannotation of the Arabidopsis thaliana reference genome. Plant J. 89: 789–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K., Kim S., Kim S.Y., Kim M., Hyun Y., Lee H., Choe S., Kim S.G., Michaels S., Lee I. (2005). SUPPRESSOR OF FRIGIDA3 encodes a nuclear ACTIN-RELATED PROTEIN6 required for floral repression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 2647–2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Derr D., Zilberman D. (2012). Deposition of histone variant H2A.Z within gene bodies regulates responsive genes. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal R.B., Kandasamy M.K., McKinney E.C., Meagher R.B. (2005). The nuclear actin-related protein ARP6 is a pleiotropic developmental regulator required for the maintenance of FLOWERING LOCUS C expression and repression of flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 2633–2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal R.B., Topp C.N., McKinney E.C., Meagher R.B. (2007). Repression of flowering in Arabidopsis requires activation of FLOWERING LOCUS C expression by the histone variant H2A.Z. Plant Cell 19: 74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete S., Mikulski P., Schubert D., Gaudin V. (2015). One, two, three: Polycomb proteins hit all dimensions of gene regulation. Genes (Basel) 6: 520–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lucas M., Pu L., Turco G., Gaudinier A., Morao A.K., Harashima H., Kim D., Ron M., Sugimoto K., Roudier F., Brady S.M. (2016). Transcriptional regulation of Arabidopsis Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 coordinates cell-type proliferation and differentiation. Plant Cell 28: 2616–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle M.R., Amasino R.M. (2009). A single amino acid change in the enhancer of zeste ortholog CURLY LEAF results in vernalization-independent, rapid flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 151: 1688–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., et al. (2012). Dual binding of chromomethylase domains to H3K9me2-containing nucleosomes directs DNA methylation in plants. Cell 151: 167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Johnson L.M., Groth M., Feng S., Hale C.J., Li S., Vashisht A.A., Wohlschlegel J.A., Patel D.J., Jacobsen S.E. (2014). Mechanism of DNA methylation-directed histone methylation by KRYPTONITE. Mol. Cell 55: 495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENCODE (2016). ENCODE Guidelines and Best Practices for RNA-seq: Revised December, 2016. encodeproject.org.

- ENCODE (2017). ENCODE Guidelines for Experiments Generating ChIP-seq Data: January, 2017. encodeproject.org.

- Fei J., Torigoe S.E., Brown C.R., Khuong M.T., Kassavetis G.A., Boeger H., Kadonaga J.T. (2015). The prenucleosome, a stable conformational isomer of the nucleosome. Genes Dev. 29: 2563–2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R.A. (1922). On the interpretation of x(2) from contingency tables, and the calculation of P. J. R. Stat. Soc. 85: 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gan E.S., Xu Y., Ito T. (2015). Dynamics of H3K27me3 methylation and demethylation in plant development. Plant Signal. Behav. 10: e1027851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K.K., Zhang H., Golden B.L., Ogas J. (2013). PICKLE is a CHD subfamily II ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829: 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J.P., Lindroth A.M., Cao X., Jacobsen S.E. (2002). Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature 416: 556–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob Y., Feng S., LeBlanc C.A., Bernatavichute Y.V., Stroud H., Cokus S., Johnson L.M., Pellegrini M., Jacobsen S.E., Michaels S.D. (2009). ATXR5 and ATXR6 are H3K27 monomethyltransferases required for chromatin structure and gene silencing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16: 763–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob Y., Bergamin E., Donoghue M.T., Mongeon V., LeBlanc C., Voigt P., Underwood C.J., Brunzelle J.S., Michaels S.D., Reinberg D., Couture J.F., Martienssen R.A. (2014). Selective methylation of histone H3 variant H3.1 regulates heterochromatin replication. Science 343: 1249–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y., Zhang D., Wang X., Tang W., Wang W., Huai J., Xu G., Chen D., Li Y., Lin R. (2013). Arabidopsis chromatin remodeling factor PICKLE interacts with transcription factor HY5 to regulate hypocotyl cell elongation. Plant Cell 25: 242–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.M., Bostick M., Zhang X., Kraft E., Henderson I., Callis J., Jacobsen S.E. (2007). The SRA methyl-cytosine-binding domain links DNA and histone methylation. Curr. Biol. 17: 379–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A.A., Lee A.J., Roh T.Y. (2015). Polycomb group protein-mediated histone modifications during cell differentiation. Epigenomics 7: 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.H., Sung S. (2014). Polycomb-mediated gene silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Cells 37: 841–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan N.J., et al. (2003). A Snf2 family ATPase complex required for recruitment of the histone H2A variant Htz1. Mol. Cell 12: 1565–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku M., Jaffe J.D., Koche R.P., Rheinbay E., Endoh M., Koseki H., Carr S.A., Bernstein B.E. (2012). H2A.Z landscapes and dual modifications in pluripotent and multipotent stem cells underlie complex genome regulatory functions. Genome Biol. 13: R85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafos M., Kroll P., Hohenstatt M.L., Thorpe F.L., Clarenz O., Schubert D. (2011). Dynamic regulation of H3K27 trimethylation during Arabidopsis differentiation. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Gadue P., Chen K., Jiao Y., Tuteja G., Schug J., Li W., Kaestner K.H. (2012). Foxa2 and H2A.Z mediate nucleosome depletion during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell 151: 1608–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P.Y., Lévesque N., Kobor M.S. (2009). NuA4 and SWR1-C: two chromatin-modifying complexes with overlapping functions and components. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87: 799–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusser A., Urwin D.L., Kadonaga J.T. (2005). Distinct activities of CHD1 and ACF in ATP-dependent chromatin assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March-Diaz R., Garcia-Dominguez M., Lozano-Juste J., Leon J., Florencio F.J., and Reyes J.C. (2008). Histone H2A.Z and homologues of components of the SWR1 complex are required to control immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 53: 475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March-Díaz R., García-Domínguez M., Florencio F.J., Reyes J.C. (2007). SEF, a new protein required for flowering repression in Arabidopsis, interacts with PIE1 and ARP6. Plant Physiol. 143: 893–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron R., Reinberg D. (2011). The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 469: 343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi G., Shen X., Landry J., Wu W.H., Sen S., Wu C. (2004). ATP-driven exchange of histone H2AZ variant catalyzed by SWR1 chromatin remodeling complex. Science 303: 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A.J., Shen X. (2009). Chromatin remodelling beyond transcription: the INO80 and SWR1 complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10: 373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozgova I., Kohler C., Hennig L. (2015). Keeping the gate closed: functions of the polycomb repressive complex PRC2 in development. Plant J. 83: 121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Xing R., Clarenz O., Pokorny L., Goodrich J., Schubert D. (2014). Polycomb-group proteins and FLOWERING LOCUS T maintain commitment to flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 26: 2457–2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCBI (2017). Magic-BLAST Short Read Mapper. ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/magicblast/LATEST/.

- Noh Y.S., Amasino R.M. (2003). PIE1, an ISWI family gene, is required for FLC activation and floral repression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15: 1671–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogas J., Cheng J.C., Sung Z.R., Somerville C. (1997). Cellular differentiation regulated by gibberellin in the Arabidopsis thaliana pickle mutant. Science 277: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A.R. (2014). BEDTools: The Swiss-army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 47: 11.12.11–11.12.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radman-Livaja M., Quan T.K., Valenzuela L., Armstrong J.A., van Welsem T., Kim T., Lee L.J., Buratowski S., van Leeuwen F., Rando O.J., Hartzog G.A. (2012). A key role for Chd1 in histone H3 dynamics at the 3′ ends of long genes in yeast. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F., Ryan D.P., Grüning B., Bhardwaj V., Kilpert F., Richter A.S., Heyne S., Dündar F., Manke T. (2016). deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44: W160–W165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C.W., Shi W., Smyth G.K. (2015). limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E.S., Getz G., Mesirov J.P. (2011). Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29: 24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M.D., McCarthy D.J., Smyth G.K. (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26: 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa M., Von Harder M., Cigliano R.A., Schlögelhofer P., Mittelsten Scheid O. (2013). The Arabidopsis SWR1 chromatin-remodeling complex is important for DNA repair, somatic recombination, and meiosis. Plant Cell 25: 1990–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhl D.D., Jin J., Cai Y., Swanson S., Florens L., Washburn M.P., Conaway R.C., Conaway J.W., Chrivia J.C. (2006). Purification of a human SRCAP complex that remodels chromatin by incorporating the histone variant H2A.Z into nucleosomes. Biochemistry 45: 5671–5677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarcinella E., Zuzarte P.C., Lau P.N., Draker R., Cheung P. (2007). Monoubiquitylation of H2A.Z distinguishes its association with euchromatin or facultative heterochromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 6457–6468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitges F.W., et al. (2011). Histone methylation by PRC2 is inhibited by active chromatin marks. Mol. Cell 42: 330–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert D., Primavesi L., Bishopp A., Roberts G., Doonan J., Jenuwein T., Goodrich J. (2006). Silencing by plant Polycomb-group genes requires dispersed trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27. EMBO J. 25: 4638–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira-Mendes J., Aragüez I., Peiró R., Mendez-Giraldez R., Zhang X., Jacobsen S.E., Bastolla U., Gutierrez C. (2014). The functional topography of the Arabidopsis genome is organized in a reduced number of linear motifs of chromatin states. Plant Cell 26: 2351–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaked H., Avivi-Ragolsky N., Levy A.A. (2006). Involvement of the Arabidopsis SWI2/SNF2 chromatin remodeling gene family in DNA damage response and recombination. Genetics 173: 985–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolle M., Venkatesh S., Gogol M.M., Li H., Zhang Y., Florens L., Washburn M.P., Workman J.L. (2012). Chromatin remodelers Isw1 and Chd1 maintain chromatin structure during transcription by preventing histone exchange. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19: 884–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V., Fields P.A., Boyer L.A. (2015). H2A.Z: a molecular rheostat for transcriptional control. F1000prime reports 7: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sura W., Kabza M., Karlowski W.M., Bieluszewski T., Kus-Slowinska M., Pawełoszek Ł., Sadowski J., Ziolkowski P.A. (2017). Dual role of the histone variant H2A.Z in transcriptional regulation of stress-response genes. Plant Cell 29: 791–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torigoe S.E., Urwin D.L., Ishii H., Smith D.E., Kadonaga J.T. (2011). Identification of a rapidly formed nonnucleosomal histone-DNA intermediate that is converted into chromatin by ACF. Mol. Cell 43: 638–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liu C., Cheng J., Liu J., Zhang L., He C., Shen W.H., Jin H., Xu L., Zhang Y. (2016). Arabidopsis flower and embryo developmental genes are repressed in seedlings by different combinations of Polycomb group proteins in association with distinct sets of cis-regulatory elements. PLoS Genet. 12: e1005771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Zhao Y., Zhang B. (2015). Efficient test and visualization of multi-set intersections. Sci. Rep. 5: 16923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C.M., Ramachandran S., Henikoff S. (2014). Nucleosomes are context-specific, H2A.Z-modulated barriers to RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell 53: 819–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M.M., Cox L.K., Chrivia J.C. (2007). The chromatin remodeling protein, SRCAP, is critical for deposition of the histone variant H2A.Z at promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 26132–26139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J., Jin R., Wagner D. (2017). Developmental transitions: integrating environmental cues with hormonal signaling in the chromatin landscape in plants. Genome Biol. 18: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Hu T., Smith M.R., Poethig R.S. (2016). Epigenetic regulation of vegetative phase change in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 28: 28–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Grullon S., Ge K., Peng W. (2014). Spatial clustering for identification of ChIP-enriched regions (SICER) to map regions of histone methylation patterns in embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 1150: 97–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Jing Y., Jiang Z., Lin R. (2014). The chromatin-remodeling factor PICKLE integrates brassinosteroid and gibberellin signaling during skotomorphogenic growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 2472–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Rider S.D. Jr., Henderson J.T., Fountain M., Chuang K., Kandachar V., Simons A., Edenberg H.J., Romero-Severson J., Muir W.M., Ogas J. (2008). The CHD3 remodeler PICKLE promotes trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 22637–22648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Bishop B., Ringenberg W., Muir W.M., Ogas J. (2012). The CHD3 remodeler PICKLE associates with genes enriched for trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27. Plant Physiol. 159: 418–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Clarenz O., Cokus S., Bernatavichute Y.V., Pellegrini M., Goodrich J., Jacobsen S.E. (2007). Whole-genome analysis of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 5: e129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]