Abstract

Superfund sites may be a source of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) to the surrounding environment. These sites can also act as PAH sinks from present day anthropogenic activities especially in urban locations. Understanding PAH transport across environmental compartments helps to define the relative contributions of these sources and is therefore important for informing remedial and management decisions. In the present study, paired passive samplers were co-deployed at sediment-water, and water-air interfaces within the Portland Harbor Superfund site (PHSS) and the McCormick and Baxter Superfund Site (MCBSS). These sites, located along the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon, have PAH contamination from both legacy and modern sources. Diffusive flux calculations indicate that the Willamette River acts predominately as a sink for low molecular weight PAHs from both the sediment and the air. The sediment was also predominately a source of 4 and 5 ring PAHs to the river and the river was a source of these same PAHs to the air, indicating that legacy pollution may be contributing to PAH exposure for residents of the Portland urban center. At the remediated MCBSS flux measurements highlight locations within the sand and rock sediment cap where contaminant breakthrough is occurring.

Keywords: Fate and Transport, Flux, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Passive Sampling, Superfund

INTRODUCTION

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a widespread class of persistent chemicals arising from both natural sources and anthropogenic activities [1]. In addition to the carcinogenic potential of some PAHs which are thought traditionally to drive health risks [2], PAHs have also been shown to be toxic in developing fish [3], and evidence is emerging for their neurotoxicity and negative impact on pulmonary function in humans [4, 5].

A lack of regulation on industrial discharge into water bodies before The Clean Water Act of 1972 has left many urban water bodies in the USA with highly contaminated sediments [6–8]. These sediments may be a continual source of contaminants, including PAHs, to the overlying water and surrounding environment long after cessation of direct discharge [9]. Additionally, with a continued reliance on fossil fuels and expanding urban populations, urban water bodies are subject to an increase in PAH load from non-point sources such as vehicle exhaust and storm water runoff [10–12].

Understanding the direction and magnitude of contaminant transport at these locations is important for determining the relative contribution from modern and legacy sources and subsequently for informing remedial and management decisions [13]. The exchange of contaminants between sediment and water may occur through several processes including the transport of colloids, particle resuspension/deposition, gas ebullition, advective flow, bio-irrigation, and diffusion. Meanwhile, chemical water-air exchange may result from particle deposition as well as diffusion [14]. Of these processes, diffusive flux is the only process which occurs in every system and is therefore a conservative standard baseline for total flux. Additionally, diffusive exchange has been shown to be a prominent factor for controlling urban water concentrations and measurements can provide insight into the relative contributions from other chemical exchange mechanisms [15, 16]. Diffusive flux is dependent upon the freely-dissolved (Cw) concentration gradients across environmental compartments [16]. These freely-dissolved fractions are also a better indicator for bioavailability, bioaccumulation, bio-concentration and toxicity in both water and sediment [13, 17, 18].

To measure freely dissolved and vapor phase PAH concentrations, traditional active sampling combined with filtration and/or centrifugation have been used, but can be cumbersome [15, 19–21]. Sediment equilibrium models for porewater measurements have been shown to be highly inaccurate due to their reliance on poorly described and often highly heterogeneous sediment characteristics [22]. Passive sampling allows for a direct measurement of Cw and Ca, avoiding filter bias and providing a time-weighted average incorporating episodic events [23]. Several studies have demonstrated the use of passive samplers to measure the diffusive flux of PAHs across air-water interfaces [15, 19, 24–27]. Fewer studies have utilized passive samplers to measure the diffusive flux of PAHs between porewater and water [28–30]. To the author’s knowledge, the present study is the first to measure PAH diffusive flux across both interfaces concurrently.

The Portland Harbor is located along the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon, USA and is a typical urban harbor with a history of industrial pollution dating back to the 19th century. Industrial processes including gas manufacturing, wood treatment and bulk fuel processing have resulted in high levels of contaminants including PAHs, PCBs, and metals in sediment and shoreline along much of the harbor. Subsequently, an approximately 11-mile section of the river, the Portland Harbor Superfund site (PHSS) was added to the U.S. EPA’s National Priorities List in 2000 [31]. With a surrounding metropolitan population of over 2 million people, modern non-point sources such as vehicle emissions are also likely a major source of PAHs to the Portland Harbor.

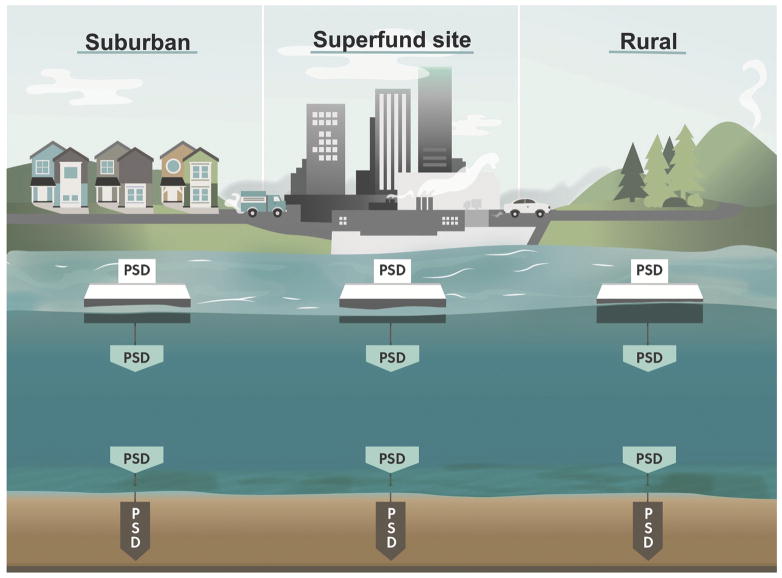

Here we demonstrate the deployment of passive samplers across both the sediment-water and water-air interfaces to better understand the relative contributions from legacy and modern day pollution using the Portland Harbor as a model urban aquatic system as depicted in Figure 1 (Figure 1). Larsson [32] showed that aquatic sediments have the potential to be a source of hydrophobic organic pollutants to the air and residents of the Portland Harbor area have voiced concerns over fumes and vapors arising from the PHSS [33]. The study design presented here helps to inform about PAH fate for residents living near the Portland Harbor and may be applied to other contaminated urban waterways. Diffusive flux of 61PAHs was determined across both interfaces at 6 different locations including upriver, downriver, and within the PHSS. Additionally, diffusive flux was determined across the sediment-water interface at 14 locations within the McCormick and Baxter Superfund Site (MCBSS) where a sediment cap was placed in 2005 to contain creosote plumes from entering the river [34]. Using a novel sediment probe design, we present the first published work of PAH diffusive flux at a remediated Superfund Site to assess sediment cap effectiveness. This probe allowed for measurement of porewater concentrations at discrete depths both within and below the sediment cap to assess the performance of the cap and assess the implications of cap failure. This probe has the potential to be used in a wide variety of soils and setting because of its durability, ease of deployment, and ability to measure discrete porewater depths.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of sampling methodology. Passive sampling devices (PSDs) were deployed in pairs across sediment-water and water-air interfaces at upstream, downstream and locations within the Portland Harbor Superfund site. Subsequently, diffusive flux was determined across both interfaces.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Study area

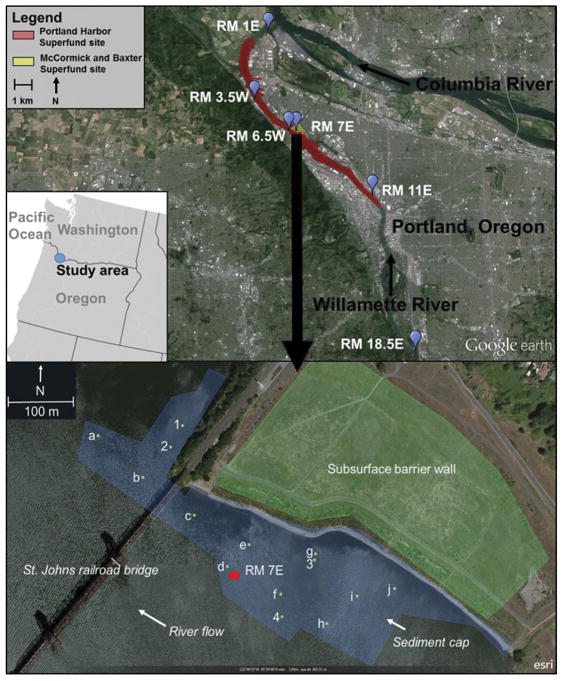

The PHSS is located on the Willamette River as it flows north through the city of Portland, Oregon from River Mile (RM)1.9 to RM11.8 as measured upstream of the Columbia River, shown in Figure 2 (Figure 2). Several locations within the Superfund site were termed “early action areas”. These locations include the eastern shore at RM11 (RM11E) due to high levels of PCBs and PAHs, and RM6.5W, home to a former gas manufacturing plant where a large tar ball was removed in 2005.

Figure 2.

(a) Portland Harbor Superfund site. Sampling locations are denoted by blue pins at 6 river mile (RM) locations as measured upstream from the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. (b) McCormick and Baxter Superfund Site. Sampling locations with letters (a–j) indicate porewater measurement within the sediment cap armoring, from 0–25cm below the sediment water-interface. Numbers (1–4) indicate placement both within and below the armoring, from 0–25cm and 25–50cm below the sediment-water interface.

The MCBSS was added to the Superfund National Priorities List in 1994 and is located within the PHSS at RM7E where the McCormick and Baxter Creosote Company operated from 1944–1991 [34]. In 2005, approximately 22 acres of contaminated sediment was capped with sand, organoclay, and a concrete/rock armoring to contain creosote seeps and prevent release of contaminants, including PAHs and pentachlorophenol from sediments. Additionally, construction was completed on an 18-acre subsurface barrier wall extending 14 to 24 meters below the surface to eliminate potential for upland contaminant migration into the river.

Sampling methodology

Deployment of PSDs occurred in September and October of 2015 at 14 locations within the MCBSS, 4 locations within the PHSS (RM11E, RM7E, RM6.5W, RM3.5W), 1 upstream (RM18.5E), and 1 downstream location (RM1E) as shown in Figure 2 (Figure 2).

At RM18.5E, RM11E, RM7E, RM6.5W, RM3.5W, and RM1E pairs of PSDs were co-deployed across sediment-water and water-air interfaces. For determination of water-air flux, PSDs were deployed from Dock-Blocks® platforms. Air cages containing 5 LDPE strips were placed 1m above the surface of the water. Below each platform, a cage containing 5 LDPE strips was deployed from a steel cable 1m below the surface of the water (1msurface). The anchoring mechanism allowed for approximately 20 meters of platform movement in the river. These platforms were co-located with paired sediment and water PSDs at RM18.5E, RM11E, RM 7E, RM6.5W, RM3.5W, and RM1E (Supplemental Data, Figure S2). Novel sediment probes to measure porewater were driven into the sediment until flush with the sediment surface (Supplemental Data, Figure S4). Briefly, these 25cm long probes consist of stainless steel casing and mesh windows coupled with a slide hammer adapter allowing for easy deployment into sediments from a standing position or by divers. An aluminum or steel insert is placed inside the probe around which LDPE strips are wrapped and secured. Similarly designed 25cm long extensions can be connected allowing for sampling at multiple depths with no concern of vertical contaminant migration (Supplemental Data, Figure S4). Water cages were deployed 0.3m above the surface of the sediment (0.3mbottom) on a steel cable attached to a submerged buoy to ensure stability within the water column.

Within the MCBSS, paired sediment and water PSDs only were deployed at 14 locations. These samplers were placed into the cap with the help of EPA divers as part of a 10-year sediment cap effectiveness assessment conducted by the Oregon DEQ. At sampling locations 1 (MCB-1), MCB-2, MCB-3, and MCB-4 a probe extension was used to measure porewater from 0–25cm (armoring) and 25–50 cm below the surface (inter-armoring). In the case of MCB-1 and MCB-2, the articulated concrete cap was removed and sediment probes were placed directly into the sand layer of the cap. For the remaining 12 locations the sediment probes were placed into the top layer of the cap which consisted of rock, sand, and deposited sediment.

Samplers within the McCormick and Baxter superfund site were deployed for approximately three weeks (September 15–16, 2015-October 6, 2015). The remaining samplers were deployed for 5 weeks (September 14, 2015-October 19, 2015). Environmental conditions and deployment are described in detail in supplemental data (Supplemental Data, Table S4).

PSD preparation and extraction

Additive free low-density polyethylene (LDPE) passive sampling devices (PSDs) were constructed in 1-meter-long strips as described in Anderson et al. [35]. Three performance reference compounds (fluorene-d10, pyrene-d10, and benzo[b]fluoranthene-d12) were added to the samplers prior to deployment for determination of in situ uptake rates. Analyte sampling rate was derived from PRC loss using only PRCs with dissipation greater than 10% and less than 90%. In this way, pyrene-d10 was used for all water and air calculations, and fluorene-d10 was used for all sediment calculations. At location MCB-3, fluorene-d10 depletion was less than 10% for both porewater measurements and data therefore should be considered to having higher error. PRC dissipation is shown in the supplemental data (Supplemental Data, Table S14).

LDPE strips were transported back to the lab in glass jars placed in coolers, within 12 hours, and stored at −20°C prior to sample processing. Sample processing is described in detail by Allan et al. [36], but briefly, PSDs were spiked with 7 deuterated surrogate extraction standards followed by dialysis in n-hexane and quantitative concentration. Surrogate extraction standards included: naphthalene-d8, acenaphthylene-d8, phenanthrene-d10, fluoranthene-d10, chrysene-d12, benzo[a]pyrene-d12 and benzo[ghi]perylene-d12. Surrogate recoveries ranged from 51% for naphthalene-d12 (RSD 13.8%) to 92% for benzo(a)pyrene-d12 (RSD 5.8%). Perylene-d12 was used as the instrumental internal standard. Transport stability studies performed by Donald et al. [37] verified that the transport times (12 hours) and temperatures (<20C) should not result in loss of PAHs. All solvents used were Optima grade or better (Fisher Scientific), and standards were purchased at purities ≥ 97%.

Chemical analysis

Samples were analyzed for 61 PAHs (Supplemental Data, Table S1) using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (GC) with an Agilent 7000C MS/MS as described in Anderson et al. 2015 [38]. Use of an Agilent Select PAH column (30m × 250μm × 0.15μm) allowed for enhanced separation of compounds. For all PAHs at least a 5-point calibration was employed with correlations ≥0.98. GC oven and MS parameters along with a comprehensive list of method detection limits (MDLs) can be found in the supplemental data.

Quality control

Quality control samples including field, trip, instrument, cleaning, reagent, and laboratory blanks as well as laboratory duplicates and over-spikes accounted for over 30% of the total samples run. Blanks contained quantifiable levels of several low molecular weight PAHs (Supplemental Data, Table S5) making up less than 1% of all PAHs measured. Samples were corrected for background concentrations by adding the average extract value for field and cleaning blanks and subtracting this value from sample extract values. To assess field variability, relative standard deviation was calculated (Supplemental Data, Table S6) from samplers deployed in triplicate in each of the three matrices (sediment, water, air) at RM 6.5. Due to the high heterogeneity of sediment, the triplicate porewater samplers at RM6.5 (RM6.5-1, RM6.5-2, RM6.5-3) will be referred to as ‘approximates’. To ensure instrument consistency over the course of analysis, continuing calibration verification samples were run and in all cases met data quality objectives. Further details can be found in supplemental data.

Calculations

We calculated the freely dissolved (Cw) and vapor phase (Ca) PAHs on both sides of the sediment-water and water-air interfaces using PSDs and an empirical uptake model with PRC derived sampling rates described by Huckins et al. [39]. Further details can be found in the supplemental data (Supplemental Data, Equations S1–S10).

Calculations for diffusive flux (Fx), expressed in units of mass/(area × time), followed the basic form of Fick’s First law where a negative flux value is defined as deposition and a positive flux value is defined as release or volatilization. Here, flux is represented as a function of the concentration gradient (C) across the x-axis (environmental interface) and the molecular diffusion coefficient (D) which is determined by both the specific properties of the chemical and environmental conditions [14].

| (1) |

Diffusive flux across the air-water interface (Fw-a) followed a Whitman 2 film model, as described in Bamford et al. [15], which defines transport rate as being limited by movement across 2 thin stagnant layers at the air-water interface described by the total mass transfer coefficient (Kol) as shown below in Equation 2 (Equation 2).

| (2) |

In this equation, H(T)’ is the unitless Henry’s law constant, corrected for temperature using the Van’t Hoff equation (Supplemental Data, Equation S14). The total mass transfer coefficient consists of air-side and water-side mass transfer coefficients which are a function of wind speed, temperature, and specific chemical characteristics (Supplemental Data, Equation S11–S13).

Diffusional flux (Fs-w) across the sediment-water interface is assumed to be rate limited by a thin layer of stagnant water called the boundary layer (δL). Calculations followed a similar method to Fernandez et al. [16] as shown in Equation 3 (Equation 3).

| (3) |

In this equation, Cpw is the freely dissolved concentration in porewater and Dw (cm2/s) is the compound specific diffusion coefficient in water.

| (4) |

In Equation 4 (Equation 4), Ѵ is the molar volume of the chemical as a liquid (cm3/mol) calculated using the LeBas method and η is the viscosity of water (10−2g/cms) at the average water temperature during deployment. Equation 4 (Equation 4) is based on a pseudo-empirical relationship and must be used with the defined units [40]. Determination of diffusional flux between the armoring (0–25cm) and sub armoring (25–50cm) is discussed further in the supplemental data.

Accurately estimating δL depth is important for describing the magnitude of diffusional flux. Boundary layer thickness decreases with increasing flow and increases with sediment surface roughness. Several studies have attempted to measure δL thickness and have reported similar values. Jorgensen et al. [41] used microelectrodes to measure oxygen gradients in a controlled laboratory environment and determined δL to be 0.025 and 0.05cm for rough and smooth sediment respectively with flow velocity between 10 and 20 cm/s. Santchi et al. [42] reported δL thicknesses of 0.019 and 0.013 for flows of 8.4 and 15.3 cm/s based on gypsum dissolution rates while Eek et al. [29] replicated these measurements but in a stagnant environment and calculated a boundary layer of 0.17cm. Koelmans et al. [28] took a different approach to measure PAH flux between sediment and water by directly measuring the mass transfer coefficient (Kl), equal to Dw/δL if transport is assumed to be controlled by the water side resistance and no gradient exists in the sediment. A laboratory measured Kl of 0.024 m/d was applied to PAH gradients between sediment and water in lakes, canals, and harbors in the Netherlands. This number is similar to the mass transfer coefficients used by Eek et al. [29] (0.020 m/d– 0.027 m/d) to measure flux of PAHs from sediment to water in Norway based on a stagnant water boundary layer.

Near its terminus, the tidally influenced Willamette River runs through a smooth, homogenous river channel and therefore, only minor differences are expected in flow or sediment type between sampling locations. During the course of the 5-week deployment in Portland Harbor, the average absolute flow velocity was 14.5 cm/s as measured by a USGS station downtown Portland. This flow velocity typically corresponds with a smooth river bottom composition of silt, mud and small organic debris and falls within the range of measured boundary layer thicknesses reported by Santchi et al. and Jorgensen et al. [41, 42]. Considering the homogeneity of the river channel and the flow rate, it was determined to be both practical and valid to use a single δL thickness of 0.02 cm for all flux calculations. The subsequent mass transfer coefficient values are therefore approximately an order of magnitude higher (0.18 to 0.29 m/d) than the values used by Koelmans et al. and Eek et al. [28, 29]. However, the aforementioned studies were based on stagnant water boundary layers and we would therefore expect a much higher mass transfer coefficient with higher flows and resultant smaller boundary layers for locations in the present study.

Statistics

Analytes below method quantification limits were assigned values of one-half method quantitation limits (MQLs) (Supplemental Data, Table S3). Relative standard deviation was calculated based on n=3 replicates in water, and air and on n=3 ‘approximates’ in sediment at RM6.5W (RM6.5(1), RM6.5(2), RM6.5(3)) as displayed in Table S6. Propagation of error in flux across the water-air interface followed Liu et al. [43] assuming relative uncertainties of 30% and 50% for air-water mass transfer velocities and Henry’s law constants respectively. Uncertainty in temperature was determined from temperature measurements at RM6.5W. Error in flux across the sediment-water interface was calculated in a similar manner assuming a relative uncertainty of 30% in the mass transfer velocity. Flux uncertainty calculations here are therefore conservative as compared to others such as Bamford et al. [15] who have not included uncertainty in Henry’s law constants.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

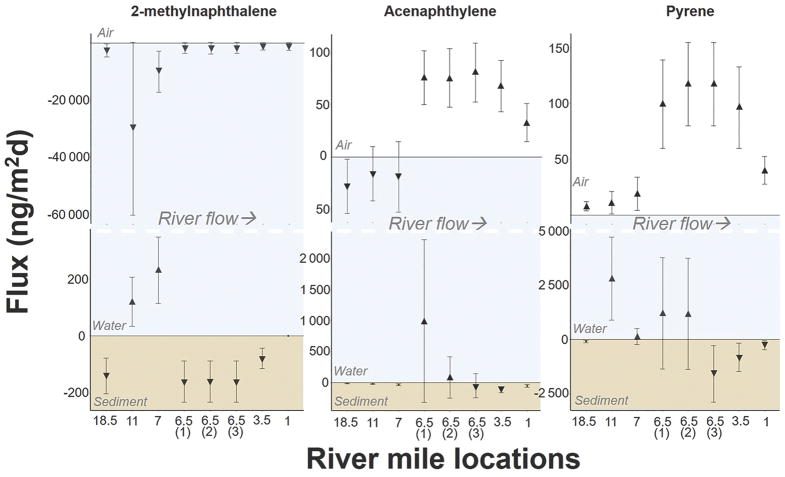

Sediments, a source of vapor phase PAHs

Throughout the PHSS results indicate that the Willamette River is largely a sink for 2 and 3-ring (low molecular weight) PAHs from the air while being a source for many 4-ring and larger (high molecular weight) PAHs especially at locations within and below the PHSS. Phenanthrene was in deposition across the water-air interface at all locations ranging from −280 (± 220) ng/m2d at RM1E to −2400 (± 1900) ng/m2d at RM7E. These values fall within the range of values for phenanthrene reported by McDonough et al. [25] at both urban and rural locations in the Great Lakes region. In a similar manner to McDonough et al., there was no correlation in the present study between water and air concentrations for phenanthrene suggesting that diffusive exchange is not the only mechanism influencing aqueous concentrations of phenanthrene.

The greatest volatilization fluxes determined in the study area were for pyrene and retene. In the case of pyrene, the magnitude of volatilization downstream of the PHSS at RM1E was more than a factor of 4 greater than upstream of the PHSS at RM18.5E indicating that the PHSS is likely a source of vapor phase pyrene in the atmosphere even after the river passes through the site. This difference was driven by an increase in dissolved water concentration. Pyrene also showed high volatilization in the Great Lakes region, though the magnitudes of volatilization were up to a factor of 7 greater than reported here [25].

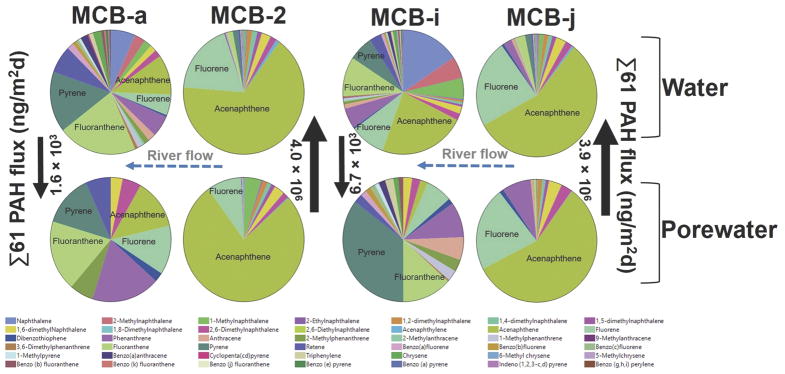

At the sediment-water interface greatest PAH release from sediment was determined at locations within the PHSS and MCBSS with high individual PAH and location variability reflecting the heterogeneity of the sediment. Hydrophobic contaminants in the sediment have the ability to be a source to the overlying water and ultimately to the air as shown by Lars and more recently proposed to be the case in the sediment plume of the Yangtze River in China [32, 44]. Examination of individual PAH flux patterns here showed several cases supporting the possibility of sediments being a source to the air. In the case of acenaphthylene, we determined volatilization to be occurring at RM6.5 and downstream locations coupled with large release from the sediment at RM6.5(1) and locations MCBJ and MCB2 as seen in Figure 3 and Figure 4 (Figure 3, Figure 4). Pyrene exhibited deposition into the sediment above and below the PHSS while being released out of the sediment at locations within the PHSS and MCBSS coupled with high volatilization within the PHSS. Additionally, a greater number of instances of positive flux across both interfaces occurred within the PHSS compared to outside of the site. Of 61 PAHs analyzed, an average of 17 individual PAHs were diffusing from sediment to water and from water to air for locations within the PHSS compared to 2 outside of the PHSS.

Figure 3.

Flux (ng/m2d) across both sediment-water and water-air interfaces for 2-methylnaphthalene, acenaphthylene and pyrene at river mile locations 18.5E, 11E, 7E, 6.5W (replicates 1–3), 3.5W, and 1E. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation after propagation of error.

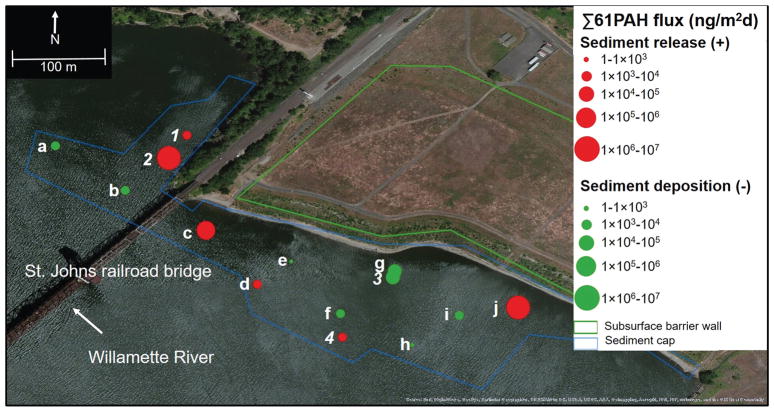

Figure 4.

Diffusive flux measurements across the McCormick and Baxter Superfund Site for 61PAHs. Sampling locations with letters (a–j) indicate porewater measurement within the sediment cap armoring from 0–25cm below the sediment water interface. Numbers (1–4) indicate placement both within and below the armoring from 0–25cm and 25–50cm below the sediment water interface. Red values indicate positive flux from the porewater to water while green values indicate negative flux from the water to porewater. Green and blue lines indicate the approximate boundaries of the sediment cap and upland barrier wall respectively.

While not definitive, these results support the hypothesis that legacy contaminated sediments are a source of PAHs to the air. This is potentially of concern for those living near Superfund sites and warrants further investigation. Indeed, it is estimated that approximately 53 million Americans, or approximately 17% of the U.S. population, live within 3 miles of a Superfund Site[45]. Furthermore, these data illustrate a process by which legacy contamination may be redistributed through transport on both a regional and global scale.

Comparison of flux magnitudes

A comparison of flux magnitudes in the present study shows that diffusive flux from air to water for low molecular weight (LMW) PAHs was generally greater than LMW PAH exchange across the sediment-water interface throughout the study area. Assuming a historical origin of sediment PAHs, a comparison of flux magnitudes across sediment-water and water-air interfaces can provide insight into the relative PAH contributions from both legacy sources as well as modern anthropogenic activities in urban aquatic systems. Following this logic, the results in the present study point toward modern anthropogenic activity being a larger source of LMW PAHs than legacy pollution. This was reflected by generally higher vapor phase PAH concentrations at locations downwind and closer to downtown Portland (RM7E, RM11E, RM18.5E). Bamford et al. [15] also showed that emissions from an urban center drove deposition of vapor phase phenanthrene into an adjacent water body, Chesapeake Bay, and estimate that diffusive exchange contributed greater than 90% of total loadings of PAHs from the atmosphere.

Conversely, legacy pollution in sediment appears to be a greater source of dissolved HMW PAHs to the Willamette River compared to vapor phase PAHs from modern anthropogenic activity. In cases where these HMW PAHs were volatilizing within the PHSS, the magnitude was lower than flux from sediments suggesting that many of these freely dissolved HMW PAHs are transported downstream and deposited. This is supported by the determination that dissolved concentrations of HMW PAHs below the PHSS at RM1E (5.6ng/L) were more than double the concentration above the PHSS at RM18.5E (2.5ng/L). However, redistribution of contaminants may also be occurring on a local scale which is demonstrated by the replicates at RM6.5W. Sediment release of contaminants occurred at RM6.5W(1) and RM6.5W(2) while deposition occurred at RM6.5W(3) with a distance of less than 1m separating the samplers. The small magnitudes of HMW PAH transfer across the air-water interface may also be due to the low fraction of vapor phase HMW PAHs in the atmosphere. Indeed, particulate bound HMW PAHs may be an important contributor to PAH load, a question beyond the scope of the present study.

The study design presented here demonstrates how passive samplers may be co-deployed across environmental interfaces to better understand the relative contributions from sources at urban locations. Such knowledge may help to prioritize remediation strategies and is a critical piece for management decisions at sites such as the PHSS [13].

Flux measurements highlight seepage areas in sediment cap

Flux measurements on the MCBSS sediment cap show a highly dynamic area with instances of both PAH release and deposition as seen in Figure 4 (Figure 4). The sediment cap was constructed in 2005 and consists of sand with organoclay in spots, on top of which lies a rock armoring with concrete in areas subject to erosional processes. The newly described sediment probe (described further in SI) was placed into the rock armoring at 10 locations. At 4 locations, an extension was used to measure porewater at discrete depths below the armoring to assess the potential for future cap failure, called “early warning locations”. This probe has the potential to be used in a wide variety of soils and settings because of its ruggedness, durability, and ability to measure discrete porewater depths.

At two of the locations Σ61PAH diffusive flux from the sediment was nearly two orders of magnitude higher than any other flux measurements in the PHSS. These included MCB-j (3,900,000 ng/m2d) and MCB-2 (4,000,000 ng/m2d), with the latter being an early warning location at which the concrete armoring was removed and the sediment probe was placed directly into the sand cap. Flux measurements at MCB-2 therefore give insight into the implications of cap failure and show that concrete is likely preventing large amounts of PAHs from entering the river. However, the contaminants appear to be moving through the cap at other locations including MCB-j, MCB-c, and MCB-d indicating that the contaminated sediment at MCBSS continues to be a source of PAHs to the Willamette River. Interestingly, the largest magnitude of Σ61PAH deposition occurred at locations directly downstream from MCB-j including MCB-i, MCB-3, and MCB-g indicating that these hotspots may be redistributing PAHs on a local scale.

Historically, creosote was the main source of PAHs to the Willamette River at the MCBSS and PAH profiles in the present study point toward creosote derived PAHs as a continual source of PAHs [46]. Creosote is produced through the distillation of coal tar and is comprised primarily of LMW PAHs, in particular acenaphthene, naphthalene, and alkyl naphthalenes. At locations of PAH release from the sediment the percentage of LMW PAHs was inflated as seen in Figure 5 (Figure 5). Specifically, LMW PAHs made up on average 92% of total PAHs in the porewater at locations with net Σ61PAH release from sediment compared to 68% at locations with movement into sediment. In particular, acenaphthene accounted for 59% and 23% of Σ61PAHs in porewater at locations of net Σ61 PAH release and deposition from sediment respectively.

Figure 5.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) profiles in porewater and water at locations of elevated PAH movement from sediment to water (MCB-j, MCB-2) and at associated downstream locations with PAH deposition (MCB-i, MCB-a). Detected PAHs are represented by colors as a fraction of total PAHs. Arrows indicate direction of Σ61 PAH flux between sediment and water in units of ng/m2d.

Utilizing multiple depth measurements of pore-water at four locations in the MCBSS, we calculated the flux due to diffusion across the boundary of the armoring and inter-armoring as seen in table S14. We determined downward diffusional flux of LMW PAHs at MCB-1 and MCB-2 and postulate that this may be due to pooling of non-aqueous phase liquids (NAPLs) underneath the cap. Conversely, at locations MCB-3 and MCB-4, where there is no concrete cap, we determined the diffusional flux of PAHs to be directed upwards from the sand layer into the armoring. Future studies would benefit from an increased spatial resolution of contamination concentrations through the cap.

With the exception of the extreme flux seen at MCB-j and MCB-2, flux measurements reported here are comparable to other flux studies in urban harbors. Koelmans et al. [28] estimated Σ12PAH flux from sediments of 43,000 ng/m2d at the most contaminated site sampled in the Ijmuiden Harbor of the Netherlands. Eek et al. [30] reported porewater-water Σ15PAH flux of 3,800 ng/m2d and 32ng/m2d for uncapped and capped sediments respectively in the Oslo Harbor of Norway.

While flux measurements here indicate some breakthrough in the sediment cap, a 10-year remedial effectiveness assessment conducted by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (ODEQ) concluded that the cap meets its original remedial action objectives. A major driver for this decision was measured PAH surface water concentrations from this study which were lower than federal and state ambient water criteria [47].

Temporal extrapolations

The direction and magnitude of diffusive exchange across environmental compartments is significantly affected by environmental conditions including air temperature, precipitation, wind velocity, and flow velocity which can vary dramatically over the course of a year [15]. Data collected in the present study is therefore limited in its temporal scope though general statements based on average climatic parameters can be made. Previous studies in temperate environments have shown that higher temperatures and lower precipitation during summer months favor volatilization of PAHs [15, 25, 26]. Sampling in the present study occurred from approximately middle of September to the middle of October, typically a period of climatic transition from dry/hot to wet/cool in Western Oregon. For the 5-week deployment, 9 days of measurable precipitation were recorded for a total of 3.8 cm, approximately 4% of the annual average precipitation. Additionally, the average atmospheric temperature was 16.85°C, well above the annual average temperature of 12.5°C. Sower and Anderson, 2008 reported insignificant differences in dissolved PAH concentrations at locations in the PHSS during the wet season (winter) compared to the dry season (summer)[48]. With weather conditions favoring volatilization compared to a yearly average and consistent PAH levels it is reasonable to conjecture that the PAH deposition determined in the present study is likely occurring over the entire year. Conversely, it is possible that for compounds in volatilization, we may see deposition in winter months. Further, the magnitudes of both diffusive exchanges may be subject to high variation due to changes in wind-speed and river flow velocity with typically higher wind speeds and flow velocities in winter months increasing the diffusive exchange.

Considerations

Only PAHs in the porewater directly at the sediment-water interface may exchange with the overlying water. In the present study, we assigned porewater at 25cm sampling intervals a single value and therefore did not account for the possibility of an existing concentration gradient which may exist in the vertical profile of contaminated sediments and sediment caps [16].

Additionally, the present study utilized passive sampling devices which sequester only the freely dissolved or vapor phase fractions of contaminants. Accordingly, the present study does not address transport processes including dry and wet particle deposition, bioturbation, and other resuspension events that may play an important role in total contaminant movement.

Along the same lines, concentration gradients may also exist from the sediment surface vertically up into the water column and thus the most accurate water measurement for flux calculations would be as close as possible to the sediment-water interface. However, Fernandez et al. [16] showed very minor vertical concentration gradients from the sediment surface to 24cm above in an ocean environment. In this study, passive samplers were placed 30cm above the surface of the sediment in a river system with constant water movement where we might expect this gradient to be even less important. Indeed, even between the surface and bottom water samplers in the present study we see in most cases PAH concentrations are within 20% of each other. An exception was RM6.5W where PAH concentrations were higher closer to the bottom, possibly reflecting sediment as a significant source of PAHs to the water column at this location. Finally, measurements in the present study are discrete points and spatial interpolations are not valid.

CONCLUSIONS

This works describes the first application of passive samplers to measure the diffusive flux of contaminants across sediment-water and water-air interfaces concurrently. Such work highlights how these tools may be applied to gain insight into PAH transport at locations with inputs from multiple PAH sources. Data from studies such as this may provide information to predict the fate and exposure to contaminants and ultimately be used to inform remedial and management decisions at contaminated urban locations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported in part by award numbers P42 ES016465. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any funding organizations. We are highly appreciative of the EPA region 10 divers, in addition to E. Hughes and H. Blischke for assistance at the McCormick and Baxter Superfund Site. We are grateful to our boat captain J. Pierce and field assistance from L. Tidwell, C. Donald, A. Bergmann, H. Dixon, K. Hobbie, and S. O’Connell. In addition, we are thankful for analytic expertise and other contributions from G. Wilson, R. Scott, and G. Points and P. Hoffman. We also thank S. Carver for his graphical design expertise.

Footnotes

The supplemental data are available on the Wiley Online Library.

Data Availability

All data collected in the present study are provided in the supplemental data along with a detailed description of calculation methods.

References

- 1.Howsam M, Jones KC. Source of PAHs in the Environment. In: Neilson AH, Alasdair N, editors. PAHs and Related Compounds. Vol 3/I Chemsitry. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 1998. pp. 137–174. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baird WM, Hooven LA, Mahadevan B. Carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts and mechanism of action. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2005;45:106–114. doi: 10.1002/em.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Incardona JP, Day HL, Collier TK, Scholz NL. Developmental toxicity of 4-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in zebrafish is differentially dependent on AH receptor isoforms and hepatic cytochrome P4501A metabolism. Toxciol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;217:308–321. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gale SL, Noth EM, Mann J, Balmes J, Hammond SK, Tager IB. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and wheeze in a cohort of children with asthma in Fresno, CA. J Expos Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012;22:386–392. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perera FP, Li Z, Whyatt R, Hoepner L, Wang S, Camann D, Rauh V. Prenatal Airborne Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Exposure and Child IQ at Age 5 Years. Pediatr. 2009;124:195–202. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker SE, Dickhut RM, Chisholm-Brause C, Sylva S, Reddy CM. Molecular and isotopic identification of PAH sources in a highly industrialized urban estuary. Org Geochem. 2005;36:619–632. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weaver G. PCB Contamination in and around New Bedford, Massachusetts. Environ Sci Technol. 1984;18:22–27. doi: 10.1021/es00119a721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe DA, Long ER, Thursby GB. Sediment Toxicity in the Hudson-Raritan Estuary: Distribution and Correlations with Chemical Contamination. Estuaries. 1996;19:901–912. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allan IJ, Ruus A, Schaanning Mt, Macrae KJ, Naes K. Measuring nonpolar organic contaminant partitioning in three Norwegian sediments using polyethylene passive samplers. Sci Total Environ. 2012;423:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang L, Tang XY, Zhu YG, Zheng MH, Miao QL. Contamination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban soils in Beijing, China. Environ Int. 2005;31:822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Metre PC, Mahler BJ, Furlong ET. Urban Sprawl Leaves Its PAH Signature. Environ Sci Technol. 2000;34:4064–4070. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JH, Gigliotti CL, Offenberg JH, Eisenreich SJ, Turpin BJ. Sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to the Hudson River Airshed. Atmos Environ. 2004;38:5971–5981. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg MS, Chapman PM, Allan IJ, Anderson KA, Apitz SE, Beegan C, Bridges TS, Brown SS, Cargill JG, McCulloch MC, Menzie CA, Shine JP, Parkerton TF. Passive sampling methods for contaminated sediments: Risk assessment and management. Integr Enviro Assess Manage. 2014;10:224–236. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarzenbach RP, Gschwend PM, Imboden DM. Environmental Organic Chemsitry. 2. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: 2003. pp. 887–845. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bamford HA, Offenberg JH, Larsen RK, Ko FC, Baker JE. Diffusive Exchange of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons across the Air–Water Interface of the Patapsco River, an Urbanized Subestuary of the Chesapeake Bay. Environ Sci Technol. 1999;33:2138–2144. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez LA, Lao W, Maruya KA, Burgess RM. Calculating the diffusive flux of persistent organic pollutants between sediments and the water column on the Palos Verdes shelf superfund site using polymeric passive samplers. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:3925–3934. doi: 10.1021/es404475c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer P, Parkerton TF, Adams RG, Cargill JG, Gan J, Gouin T, Gschwend PM, Hawthorne SB, Helm P, Witt G, You J, Escher BI. Passive sampling methods for contaminated sediments: scientific rationale supporting use of freely dissolved concentrations. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2014;10:197–209. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez LA, Gschwend PM. Predicting bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soft-shelled clams (Mya arenaria) using field deployments of polyethylene passive samplers. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2015;34:993–1000. doi: 10.1002/etc.2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker JE, Eisenreich SJ. Concentrations and fluxes of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polychlorinated biphenyls across the air-water interface of Lake Superior. Environ Sci Technol. 1990;24:342–352. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bi X, Sheng G, Peng PA, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Fu J. Distribution of particulate- and vapor-phase n-alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban atmosphere of Guangzhou, China. Atmos Environ. 2003;37:289–298. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawthorne SB, Grabanski CB, Miller DJ. Measured partitioning coefficients for parent and alkyl polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in 114 historically contaminated sediments: Part 1. KOC values. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2006;25:2901–2911. doi: 10.1897/06-115r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arp HP, Breedveld GD, Cornelissen H. Estimating the in situ Sediment–Porewater Distribution of PAHs and Chlorinated Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Anthropogenic Impacted Sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:5576–5585. doi: 10.1021/es9012905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tidwell LG, Allan SE, O’Connell SG, Hobbie KA, Smith BW, Anderson KA. PAH and OPAH Flux during the Deepwater Horizon Incident. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:7489–7497. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lohmann R, Dapsis M, Morgan EJ, Dekany V, Luey PJ. Determining air-water exchange, spatial and temporal trends of freely dissolved PAHs in an urban estuary using passive polyethylene samplers. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:2655–2662. doi: 10.1021/es1025883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonough CA, Khairy MA, Muir D, Lohmann R. Significance of Population Centers As Sources of Gaseous and Dissolved PAHs in the Lower Great Lakes. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:7789–7797. doi: 10.1021/es501074r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gustafson KE, Dickhut RM. Gaseous Exchange of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons across the Air–Water Interface of Southern Chesapeake Bay. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:1623–1629. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang MD, Lee CL, Jiang JJ, Ko FC, Baker JE. Diffusive exchange of PAHs across the air-water interface of the Kaohsiung Harbor lagoon, Taiwan. J Environ Manage. 2012;110:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koelmans AA, Poot A, Lange HJD, Velzeboer I, Harmsen J, Van Noort PCM. Estimation of In Situ Sediment-to-Water Fluxes of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Polychlorobiphenyls and Polybrominated Diphenylethers. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:3014–3020. doi: 10.1021/es903938z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eek E, Cornelissen G, Breedveld GD. Field Measurement of Diffusional Mass Transfer of HOCs at the Sediment-Water Interface. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:6752–6759. doi: 10.1021/es100818w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eek E, Cornelissen G, Kibsgaard A, Breedveld GD. Diffusion of PAH and PCB from contaminated sediments with and without mineral capping; measurement and modelling. Chemosphere. 2008;71:1629–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Portland Harbor Superfund Site-Proposed Plan. US Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 2016. ( https://semspub.epa.gov/src/document/10/100020143) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsson P. Contaminated sediments of lakes and oceans act as sources of chlorinated hydrocarbons for release to water and atmosphere. Nature. 1985;317:347–349. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Public Health Assessment for Portland Harbor. Oregon Department of Human Services Superfund Health Investigation and Education Program. Portland, OR: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCormick and Baxter Creosoting Company-Record of Decision. US Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 1996. ( https://semspub.epa.gov/src/document/10/1050989) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson KA, Sethajintanin D, Sower GJ, Quarles L. Field Trial and Modeling of Uptake Rates of In Situ Lipid-Free Polyethylene Membrane Passive Sampler. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:4486–4493. doi: 10.1021/es702657n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allan SE, Smith BW, Anderson KA. Impact of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill on Bioavailable Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Gulf of Mexico Coastal Waters. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:2033–2039. doi: 10.1021/es202942q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donald CE, Elie MR, Smith BW, Hoffman PD, Anderson KA. Transport stability of pesticides and PAHs sequestered in polyethylene passive sampling devices. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2016;23:12392–12399. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6453-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson KA, Szelewski MJ, Wilson G, Quimby BD, Hoffman PD. Modified ion source triple quadrupole mass spectrometer gas chromatograph for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon analyses. J Chromatogr A. 2015;1419:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huckins JN, Petty JD, Booij K. Monitors of the Organic Chemicals in the Environment. Springer; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayduk W, Laudie H. Prediction of diffusion coefficients for nonelectrolytes in dilute aqueous solutions. AlChE Journal. 1974;20:611–615. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorgensen BB, Revsbech NP. Diffusive boundary layers and the oxygen uptake of sediments and detritus. Limnol Oceanogr. 1985;30:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santchi PH, Bower P, Nuffeler UP, Azevedo A, Broecker WS. Estimates of the resistance to chemical transport posed by the deep-sea boundary layer. Limnol Oceanogr. 1983;28:899–912. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Wang S, McDonough CA, Khairy M, Muir D, Lohmann R. Estimation of Uncertainty in Air–Water Exchange Flux and Gross Volatilization Loss of PCBs: A Case Study Based on Passive Sampling in the Lower Great Lakes. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:10894–10902. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin T, Guo Z, Li Y, Nizzetto L, Ma C, Chen Y. Air–Seawater Exchange of Organochlorine Pesticides along the Sediment Plume of a Large Contaminated River. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:5354–5362. doi: 10.1021/es505084j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Population Surrounding 1,388 Superfund Remedial Sites. US Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, D.C: 2015. ( www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-09/documents/webpopulationrsuperfundsites9.28.15.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mueller JG, Chapman PG, Pritchard PH. Creosote-contaminated sites. Environ Sci Technol. 1989;23:1197–1201. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fourth Five-Year Report for McCormick & Baxter Creosoting Company Superfund Site. Oregon Department of Environmental Quality; Portland, Oregon: 2016. ( https://semspub.epa.gov/src/document/10/100031136) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sower JG, Anderson KA. Spatial and Temporal Variation of Freely Dissolved Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in an Urban River Undergoing Superfund Remediation. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:9065–9071. doi: 10.1021/es801286z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.