Abstract

Introduction

The advent of Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) offers a novel approach in the treatment of glaucoma with the number of procedures developing at an exciting pace.

Areas Covered

MIGS procedures aim to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) via four mechanisms: (1) increasing trabecular outflow, (2) increasing outflow via suprachoroidal shunts, (3) reducing aqueous production, and (4) subconjunctival filtration. A comprehensive search for published studies for each Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) device or procedure was undertaken using the electronic database PubMed. Search terms included ‘minimally invasive glaucoma surgery’, ‘microincisional glaucoma surgery’, and ‘microinvasive glaucoma surgery’. A manual search for each device or procedure was also performed. After review, randomized control trials and prospective studies were preferentially included.

Expert Opinion

These procedures offer several benefits: an improved safety profile allowing for intervention in earlier stages of glaucoma, combination with cataract surgery, and decreased dependence on patient compliance with topical agents. Established MIGS procedures have proven efficacy and more recent devices and procedures show promising results. Despite this, further study is needed to assess the long term IOP-lowering effectiveness of these procedures. Particularly, rigorous study with more randomized control trials and head-to-head comparisons would allow for better informed clinical and surgical decision-making. MIGS offers new solutions for glaucoma treatment.

Keywords: glaucoma, microinvasive, minimally invasive, procedures, surgical therapy

1.0 Introduction

Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) refers to a collection of procedures that have boomed in the past two decades. The definition of MIGS continues to evolve, but is best defined as any surgical manipulation or device implantation that involves a self-sealing, clear corneal incision (ab interno) that inflicts minimal trauma to surrounding tissues, with short surgical time, and results in a decrease in intraocular pressure (IOP) with a quick recovery. These procedures are often combined with cataract surgery.

An ideal MIGS procedure would have IOP-lowering capability equivalent to traditional incisional glaucoma surgeries, such as trabeculectomy, but with an improved safety profile, predictability, and absence of a bleb. Vision threatening complications resulting from incisional glaucoma surgery such as cataract formation, hypotony, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, and bleb leakage, endophthalmitis, and the need for reoperation – especially with antimetabolites[1][2][3][4]* herald the need for alternative IOP-lowering procedures with decreased morbidity. These surgeries should not be technically challenging so they can be employed globally in all areas of glaucoma practice where surgical mentorship is not available. Additionally, these procedures should be cost-effective and require minimal post-operative monitoring to be feasible in all areas of glaucoma practice where extensive follow-up is not always possible.

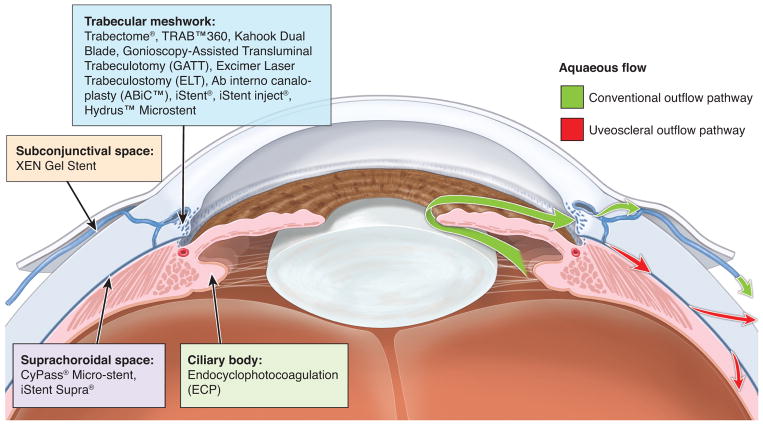

There are four mechanisms of action for existing MIGS procedures: (1) increasing trabecular outflow by bypassing the trabecular meshwork, (2) increasing outflow via suprachoroidal shunts, (3) reducing aqueous production, and (4) subconjunctival filtration (Figure 1). Currently, the target population for MIGS consists of patients with mild or moderate glaucomatous disease. However, options for patients with more severe disease will be discussed as well. In this article, we review the current therapies employed in MIGS, categorized by the way that these surgeries modulate aqueous humor outflow, with a focus on new therapies currently in development (Table 1).

Figure 1. Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) mechanisms of action.

Table 1.

Characteristics of MIGS Procedures

| MIGS device or procedure | Type of study | Patients | IOP-loweringa at one yearb | Medication decrease | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trabectome® alone10 | Prospective case series | 80 eyes of 69 POAGc patients |

30.90% 26.6 ±8.1 to 17.9 ±6.1mmHg P<0.01 |

4.0 ±1.4 to 2.3±1.2 P<0.01 |

Surgical re-intervention 16.3% (n=13) |

| Trabectome® + CE/IOLd5 | Prospective case series | 304 eyes with POAG and cataract | 20.0 ±6.3 to 15.5 ±2.9 mmHg P value not reported |

2.65 ±1.13 to 1.44 ±1.29 P value not reported |

78.4% (n=239) blood reflux IOP spike 8.6% (n=26) 1 day 2.0% (n=6) 1 week Hypotony 1.3% (n=4) Surgical re-intervention 2.3% (n=7) trabeculectomy 0.3% (n=1) shunt 0.3% (n=1) SLT |

| TRAB™360 | No published studies | ||||

| Kahook Dual Blade | No published studies | ||||

| GATT alone19 | Retrospective case series | 32 eyes of 29 patients with POAG | 25.6±6.1 to 15.7±4.5mmHg P value not reported |

3.2±0.9 to 1.5±1.2 P value not reported |

Hyphema 23% (n=7) 1 week 3% (n=1) 1 month 3% (n=1) 3 months IOP spike n= 2 steroid-induced n=1 choroidal fold |

| GATT + CE/IOL19 | 21 eyes of 17 patients with POAG and cataract | 23.9±7.2 to 15.5±1.7mmHg P value not reported |

2.9±1.1 to 1.0±1.4 P value not reported |

Hyphema 29% (n=6) 1 week 3% (n=1) 6 months |

|

| ELT alone24 | Randomized controlled trial | 15 eyes with POAG refractory to medical therapy |

29.60% 25.0 ±1.9 to 17.6 ±2.2mmHg P<0.0001 At two years |

2.27 ±0.6 to 0.73 ±0.8 P=0.005 |

Hyphema 80% (n=12) IOP spike 20% (n=3) |

| ELT + CE/IOL25 | Prospective case series | 64 eyes of 64 patients with POAG or ocular hypertension and cataract |

Preoperative IOPs ≤21mmHg 11.5% 16.5 ±2.9 to 14.6 ±3.7mmHg P=0.012 Preoperative IOPs >21mmHg 36.6% 25.8 ±2.9 to 16.4 ±5.4mmHg P<0.001 |

Preoperative IOPs ≤21mmHg 42.9% 2.5 ±1.0 to 1.4 ±1.3 P<0.001 Preoperative IOPs >21mmHg 29.5% 2.2 ±1.4 to 1.6 ±1.5 P=0.085 |

Not reported |

| ABiC™ | No published studies | ||||

| iStent® alone37 | Prospective, randomized study | 38 patients with POAG | 25.0 ±1.1 to 14.9 ±1.9mmHg P value not reported |

Not reported | Not reported |

| iStent® + CE/IOL32 | Randomized control trial | 117 eyes of 116 patients with mild to moderate glaucoma and cataract | 25.4 ±3.5 to 17.1 ±2.9 mmHg At 2 years P value not reported |

1.6 ±0.8 to 0.3 ±0.6 At 2 years P value not reported |

17.2% (n=20) corneal edema, anterior chamber cells, corneal abrasion, discomfort, subconjunctival hemorrhage, blurry vision or floaters 6% (n=7) posterior capsule opacification 4.3% (n=5) stent obstruction 3.4% (n=4) visual disturbance 2.6% (n=3) stent malposition 0.9% (n=1) iritis 0.9% (n=1) conjunctival irritation 0.9% (n=1) disc hemorrhage IOP spike 4.3% (n=5) Intraoperative 4.3% (n=5) vitrectomy 0.9% (1) stent removal and replacement 0.9% (n=1) stent malposition and replacement 6% (n=7) iris touch 0.9% (n=1) endothelial touch |

| iStent inject®42 | Randomized control trial | 94 POAG patients uncontrolled on one medication | 25.2 ±1.4 to 13 ±2.3mmHg P value not reported |

Not reported |

IOP spike 1% (n=1) 1% (n=1) stent not visible 1% (n=1) soreness/discomfort |

| CyPass® Micro-stent55 | Prospective interventional clinical trial | 65 eyes of 65 patients with POAG refractory to medical therapy |

34.70% 24.5 ±2.8 to 16.4 ±5.5mmHg P value not reported |

2.2 ±1.1 to 1.4 ±1.3 P=0.002 |

Hyphema 6.2% (n=4) IOP spike 10.8% (n=7) Surgical re-intervention 18.5% (n=12) 3.1% (n=2) visual acuity reduced >2 lines 7.7% (n=5) cataract progression |

| CyPass® Micro-stent + CE/IOL54 | Prospective interventional clinical trial | 167 eyes of 142 patients with POAG and cataract |

Preoperative IOPs <21mmHg 16.6 ±2.7 to 15.7 ±3.0mmHg Preoperative IOPs ≥21mmHg 25.9 ±5.4 to 16.3 ±3.4mmHg P<0.001 |

75% 49% Actual values and P value not reported |

Hyphema 1.2% (n=2) IOP spike 3% (n=5) Hypotony 13.8% (n=23) Surgical re-intervention 6% (n=10) 0.6% (n=1) corneal edema 1.2% (n=2) endothelial touch 5.4% (n=9) obstruction of implant 0.6% (n=1) repositioning 0.6% (n=1) explanatation 1.8% (n=3) secondary cataract 0.6% (n=1) macular edema |

| iStent Supra® | No published studies | ||||

| ECP64 | Prospective case series | 25 eyes of 25 patients uncontrolled on medications with previous tube shunts |

30.80% 24.02 ±6.24 to 15.36 ±3.8mmHg P<0.0001 |

49.10% 3.2 ±0.99 to 1.47 ±1.31 P<0.001 |

n=1 corneal edema n=2 corneal graft failure n=1 cystoid macular edema |

| ECP + CE/IOL63 | Prospective matched control study | 80 eyes with medically controlled POAG and cataract |

10.20% 18.1 ±3.0 to 16.0 ±2.8mmHg P<0.001 |

1.5 ±0.8 to 0.4 ±0.7 P<0.001 |

Hyphema 2.5% (n=2) |

| XEN45 Gel Stent76 + CE/IOL + mitomycin-C (MMC) | Prospective case series | 30 eyes with POAG and cataract controlled on at least 2 medications |

29.34% 21.2 ±3.4 to 15.03 ±2.47mmHg P<0.001 |

94.70% 3.07 ±0.69 to 0.17 ±0.65 P<0.001 |

n=2 incomplete implantation of stent n=1 encapsulated bleb |

Percentages as reported by original authors

IOP-lowering at one year unless otherwise specified

Primary Open Angle Glaucoma

Cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation

2.0 Increasing trabecular outflow

Multiple procedures and indwelling ocular stents have been developed to increase trabecular outflow. The most well-established are the ab interno trabeculotomy with the Trabectome® (Neomedix, Tustin, CA, US), and the iStent® (Glaukos Corporation, Laguna Hills, CA, US).

2.1 Ab interno trabeculotomy (AIT)

Ab interno trabeculotomy (AIT) is a method of increasing trabecular outflow in which parts of the trabecular meshwork are removed. There are several iterations of AIT which meet the definitions of MIGS. First, AIT with the Trabectome® system was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2004 and has the Conformité Européenne (CE) mark of approval. The Trabectome® is performed under direct gonioscopy and generally requires instillation of ophthalmic viscoelastic device (OVD) into the anterior chamber. Electrocauterization ablates the trabecular meshwork and inner wall of Schlemm’s canal. Although no randomized clinical trials exist using the Trabectome®, more than a decade’s worth of prospective and retrospective studies evaluating treatment with the Trabectome® alone and in combination with cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation (CE/IOL) show efficacy in decreasing intraocular pressure (IOP) in primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) by 20–40%[5][6][7][8][9][10] and in pseudoexfoliation glaucoma (PXG) by 30%[11][12]. The most common complication is early postoperative hyphema, likely from blood reflux from a now patent drainage system, with delayed-onset hyphema also rarely reported[13]. When hyphema is excluded, the procedure demonstrates an improved complication profile both in number and severity when compared to trabeculectomy (4.3% and 35.3%, respectively)[14]**.

More recently, the trabeculotome, TRAB™360 (Sight Sciences, Menlo Park, CA, US) and the Kahook Dual Blade (New World Medical, Rancho Cucamonga, CA, US) emerged as alternative methods of performing AIT. No clinical trials or case studies are published using these devices, but preliminary data using TRAB™360 show both a reduction in IOP (19.8±6.4 to 13.5±4.6mmHg) and ocular hypotensive medications (1.1±1.2 to 0.2±0.5) with 73% of patients requiring no medications at a short follow-up period of less than a year. The most common adverse event was hyphema resolving within a week[15]. Preclinical studies using human cadaveric tissue showed the new dual blade device removed trabecular meshwork tissue more completely and without injury to surrounding tissues when compared to the Trabectome®[16]*.

2.2 Gonioscopy-Assisted Transluminal Trabeculotomy (GATT)

Gonioscopy-Assisted Transluminal Trabeculotomy (GATT) is similar to the conventional 360° suture trabeculotomy. The latter procedure was initially used for congenital glaucoma, but more recently shows efficacy in adult glaucoma[17]*. GATT is performed ab interno with the anterior chamber filled with OVD, and an illuminated microcatheter or a marked 4-0 clear nylon suture[18]. In either technique, the microcatheter or suture is guided into Schlemm’s canal at under direct gonioscopy at a goniotomy incision and advanced 360 degrees.

While there are no randomized control trials, Grover et al first described this technique when they reported results of POAG patients and secondary glaucoma patients undergoing the procedure with or without CE/IOL. At 12 months, POAG patients had an overall decrease in IOP of 39.8% (−11.1±6.1mmHg, P<0.001). There was no difference in IOP reduction with or without concurrent or prior CE/IOL, with IOP reduction of 9.9mmHg in the group with GATT alone, 8.4mmHg in the group with concurrent GATT and cataract surgeries, and 7.6mmHg in patients undergoing GATT with prior CE/IOL (P>0.35). Overall, these patients had a decrease of 1.1±1.8 medications at 12 months (P=0.013)[19]*.

This technique was studied most recently in a small group of patients with juvenile open angle glaucoma (JOAG) and primary congenital glaucoma (PCG). In this retrospective chart review with follow-up of at least 12 months, IOP decreased from 27.3mmHg to 14.8mmHg and ocular hypotensive medications decreased from a baseline of 2.6 to 0.86[20].

In both studies, the most common adverse event was post-operative hyphema, occurring in 30% of adult POAG patients and 36% of PCG and JOAG patients. This hyphema was transient with almost all cases resolved by one month. More studies, particularly randomized control trials, are necessary to determine the long-term IOP-lowering effect of this novel technique, especially with regard to the potential for scarring or increased resistance in Schlemm’s canal.

2.3 Ab interno Canaloplasty (ABiC™)

Canaloplasty involves threading a microcatherter through Schlemm’s canal and dilating the canal with OVD to improve outflow. This approach traditionally involved conjunctival and scleral incision and dissection, in addition to placement of a tensioning suture within the lumen of the canal. In Ab interno Canaloplasty (ABiC™), a new procedure, the microcatheter is inserted via an ab interno incision under gonioscopy, sparing the conjunctiva and sclera and eliminating the need for a tension suture. No clinical trials are published evaluating the safety or efficacy of this surgical technique[21].

2.4 Excimer Laser Trabeculostomy (ELT)

Excimer Laser Trabeculostomy (ELT) is a procedure in which an excimer laser makes small openings in trabecular meshwork to decrease resistance to aqueous outflow. The procedure is performed through an ab interno incision with a 308nm xenon chloride excimer laser (AIDA, Glautec AG, Nürnberg, Germany) under direct gonioscopy or an endoscope (AIDA, TUI-Laser, Munich, Germany) with minimal thermal effects on the tissue.

Multiple studies demonstrate that ELT is effective alone and in combination with CE/IOL[22][23] over the last decade. Recently, Babighian et al demonstrated efficacy in patients refractory to topical medications undergoing ELT or 180 degree SLT in a randomized control trial. In the ELT group, IOP decreased by 29.6% (25.0 ±1.9 to 17.6 ±2.2mmHg, P<0.0001) with 53.3% of patients achieving success, defined as an IOP ≥20% without medications, laser, or surgical therapy at 24 months. Ocular hypotensive medications in the ELT group decreased from 2.27 ±0.6 to 0.73 ±0.8 (P=0.005). Patients in the SLT group had a decrease in IOP of 21% (23.9 ±0.9 to 19.1 ±1.8mmHg, P<0.0001), a success rate of 40%, and a significant medication reduction (2.2 ±0.7 to 0.87 ±0.8, P<0.0001). Interestingly, ELT and SLT had comparable success rates with no significant difference between the two. Adverse events included transient hyphema in 80% of patients in the ELT group[24]*.

In a prospective case series, Töteberg-Harms et al observed that patients with higher preoperative IOPs undergoing ELT and CE/IOL had greater success[25]*. This study used the same definition of success as the Tube versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) Study[26]. The group with preoperative IOP ≤21mmHg had a success of 37.5% with a decrease in IOP of 11.5% (16.5 ±2.9 to 14.6 ±3.7mmHg, P=0.012) while 62.5% of those with preoperative IOPs >21mmHg achieved success with a decrease in IOP of 36.6% (25.8 ±2.9 to 16.4 ±5.4mmHg, P<0.001). This is consistent with other studies that find CE/IOL alone is more effective at IOP-lowering when performed in patients with higher preoperative IOPs[27]*. No serious complications were reported in this study. More study is needed to determine the long-term patency of the microperforations in the trabecular meshwork.

2.5 iStent®

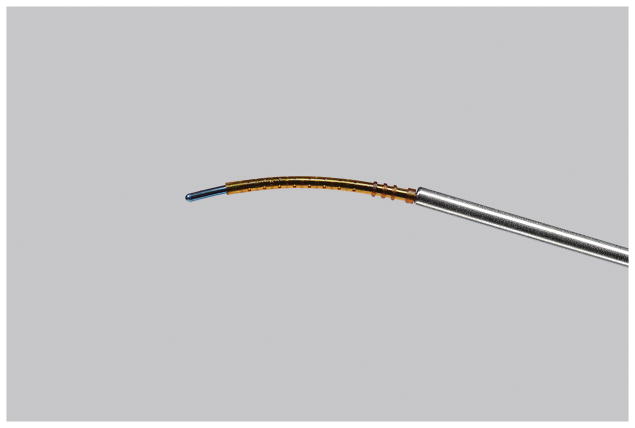

The first generation iStent® is an L-shaped stent inserted with an injector ab interno into Schlemm’s canal through the trabecular meshwork using gonioscopy and a sliding technique, allowing for a conduit directly to the anterior chamber (Figure 2). It is FDA approved in the US when combined with CE/IOL and has Conformité Européenne approval either with or without CE/IOL. Over a decade’s worth of ex vivo, fluid dynamic studies[28][29][30] and clinical trials prove the efficacy of the iStent® in IOP-reduction and trabecular outflow both with and without CE/IOL.

Figure 2. The first generation iStent®.

Used with permission from Glaukos Corporation

The iStent Study Group reported results from a prospective, controlled clinical trial where patients were randomized to iStent® insertion with CE/IOL or CE/IOL alone. In these patients with mild to moderate glaucoma, 72% of the study group had IOPs ≤21mmHg without ocular hypotensive medications, compared to 50% of the control group (P<0.001) at one year. Sixty-six percent of the study group and 48% of the control group (P=0.003) had an IOP reduction of ≥20% without ocular hypotensive medications[31]*. At two years, 61% of the study group and 50% of the control group (P=0.036) had IOPs ≤21mmHg not on medication. Fifty-three percent of the study group and 44% of the control group (P=0.09) had an IOP reduction of ≥20% without ocular hypotensive medications[32]*. Most recently, in a prospective series of patients undergoing insertion of a single iStent® with CE/IOL, Neuhann showed a 36% reduction in IOP compared to baseline (24.1 ±6.9 to 14.9 ±2.3mmHg) at 36 months in addition to an 86% medication reduction (1.8 ±0.9 to 0.3±0.5) in a cohort of patients with moderate to advanced glaucoma where 40% of eyes had undergone previous glaucoma surgeries[33]*. The most common complications of the iStent® include stent malposition or obstruction and are treated with removal and replacement or Nd:YAG laser. To our knowledge there is only one reported loss of visualization of an iStent® in the literature and it was quickly visualized after treatment with an Nd:YAG laser for apparent obstruction[34].

Further studies showed the efficacy of singular[34][35] and multiple[30] iStents® in combination with CE/IOL. In a study comparing the implantation of two or three iStents® with CE/IOL in 53 eyes, Belovay et al showed that 70% of eyes achieved an IOP of ≤15mmHg with no significant difference in IOP-lowering from baseline between the groups. However, there was a statistically significant difference in the amount of medication reduction – the group with two iStents® reduced their number of medications by 64% as compared to an 85% reduction in the three iStent® group (P=0.04)[36]. Katz et al evaluated the use of multiple stents without cataract surgery, and found that at 18 months 89.2% of patients with one stent, 90.2% of patients with two stents, and 92.1% of patients with three stents achieved an IOP reduction of ≥20% and ≤18mmHg without ocular hypotensive medications. Additionally, Katz et al showed a greater reduction of mean IOP with each additional stent (P<0.001)[37]*.

2.6 iStent inject®

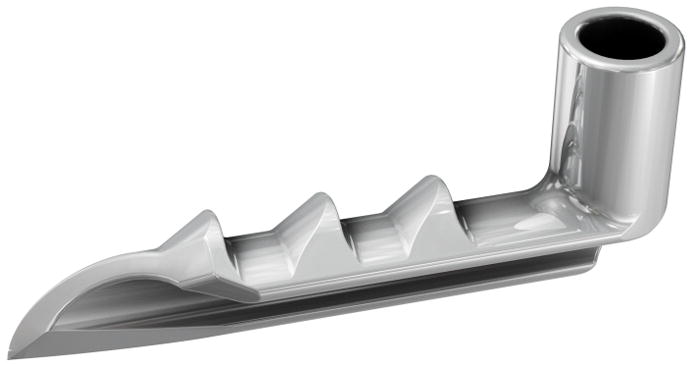

The second generation of the iStent®, the iStent inject® (Glaukos Corporation, Laguna Hills, CA, US), is undergoing clinical trials in the United States[38][39] and has CE approval. In contrast to the iStent®, this titanium stent is administered via auto-injection (Figure 3). More than one iStent inject® can be loaded into the delivery system and directly delivered to Schlemm’s canal through the trabecular meshwork without withdrawing the inserter. This mechanism is important, as multiple stents increase aqueous outflow[40] and progressively decrease IOP[37]*, without necessitating repeated withdrawals and insertions.

Figure 3. The iStent inject®.

Used with permission from Glaukos Corporation

Voskanyan et al reports results from a pan-European, prospective, unmasked clinical trial with patients undergoing implantation of two iStent injects®. This study found that 66% of patients achieved an IOP ≤18mmHg without ocular hypotensive medications and 81% of patients achieved an IOP of ≤18mmHg regardless of ocular hypotensive medication use. Additionally, 71.7% of patients reduced their medication burden by at least two medications. Complications were minimal, and none were vision-threatening[41]*.

The prospective unmasked clinical trial by Fea et al reports the results of patients randomized to receiving iStent inject® (two stents) or two ocular hypotensive medications. At 12 months, 94.7% of patients in the study group and 91.8% of patients in the control group had an unmedicated IOP reduction of ≥20% from a washed out baseline. However, at 12 months 53.2% of patients in the study group and 35.7% of patients in the control group had an unmedicated IOP reduction of ≥50% from a washed out baseline IOP and this was statistically significant (P=0.02). The safety and adverse events profile in this study was excellent[42].

Klamann et al showed successful IOP-lowering with the iStent inject® (two stents) at 6 months in patients with POAG and PXG of 33% (21.19±2.56 to 14.19±1.38, P<0.001) and 35% (23.75±3.28 to 15.33±1.07, P<0.001), respectively. These groups also had reductions in medications in the POAG group from 2.19 ±0.91 to 0.88 ±0.62 (P<0.001) and in the PXG group 2.33 ±1.23 to 1.04 ±0.30 (P<0.001). Three patients in the study had pigmentary glaucoma – all of these patients eventually underwent trabeculectomy due to persistently elevated IOP over 30mmHg[43]*.

2.7 Hydrus™ Microstent

The Hydrus™ Microstent (Ivantis Inc, Irvine, CA, US) is inserted through an ab interno incision and dilates Schlemm’s canal while bypassing the trabecular meshwork to increase trabecular outflow. An ex vivo study and mathematical model both showed that the Hydrus increases flow more than two iStents® as it is longer and dilates Schlemm’s canal over three clock hours[44],[45]. The Hydrus is inserted via a pre-loaded injector and is currently being studied alone, combined with CE/IOL, and in comparison to the iStent[46],[47],[48]. Its mechanism of action is similar to that of canaloplasty, and has comparable IOP-lowering and safety profiles when the two are compared[49].

Pfeiffer et al published results of a clinical trial comparing patients undergoing Hydrus™ Microstent placement with CE/IOL to patients undergoing CE/IOL alone. Success was defined as ≥20% reduction in mean washed-out IOP and was achieved in 80% of study patients and 46% of control patients at 24 months (P=0.008). IOP decreased from 26.3±4.4 to 16.9±3.3mmHg in the study group and from 26.6±4.2 to 19.2±4.7mmHg in the control group (P=0.0093) at 24 months. The study also showed a statistically significant decrease in medications (2.0 ±1.0 to 0.5 ±1.0 in the study group versus 2.0 ±1.1 to 1.0 ±1.0 in the control group, P = 0.0189) at 24 months.

Complications were similar between the groups and only one patient in the study group required additional surgical intervention. Additionally, 12% of study patients had focal peripheral anterior synechiae which did not have an effect on study outcomes[50]*.

3.0 Suprachoroidal shunts

Suprachoroidal shunts target drainage through the suprachoroidal space. Several devices exist, including the CyPass® Micro-stent (Transcend Medical Inc, Menlo Park, CA, US), the iStent Supra® (Glaukos Corporation, Laguna Hills, CA, US), the SOLX® Gold Shunt (SOLX, Waltham, MA, US), the Aquashunt™ (OPKO Health Inc., Miami, FL, US), and the STARflo™ Glaucoma Implant (iSTAR Medical SA, Wavre, Belgium).

3.1 CyPass® Micro-stent

The CyPass® Micro-stent is designed with a slight curvature, holes throughout the body of the stent to allow for aqueous outflow, and a cuff that anchors the stent in the angle of the anterior chamber (Figure 4). Insertion of the CyPass® Micro-stent is performed ab interno, after pharmacological miosis and filling of the anterior chamber with OVD. Using gonioscopy, the guidewire onto which the stent is placed is guided into the eye to dissect and spare both the ciliary body and the scleral spur. The stent is anchored with retention rings in the supraciliary space and the guidewire is removed.

Figure 4. CyPass® Micro-stent loaded onto CyPass applier guidewire.

©2016 Novartis, used with permission

This implant is not FDA approved in the US, but has CE approval. It may be placed with or without CE/IOL. Three large clinical trials evaluated the CyPass: the CyPass Clinical Experience (CyCLE) study evaluated the CyPass with CE/IOL[51], the DUETTE clinical trial evaluated the CyPass alone, and the COMPASS trial evaluated the CyPass alone and with CE/IOL[52]. In the CyCLE study, uncontrolled glaucoma patients had a 36.9% decrease in IOP at 6 months (21.1 ±5.91 to 15.6 ±0.5mmHg, P<0.001) and a 35% decrease in IOP (25.9 ±5.4 to 16.3 ±3.4mmHg, P<0.001) at 12 months. Patients with controlled IOP had a 75% decrease in medications, with 65% of patients medication free at 12 months. The study reported no sight-threatening complications, with the most common complications being implant obstruction, hypotony, and 6% of patients requiring further surgical intervention[53]*,[54]*. The DUETTE study reported that IOP decreased by 34.7% (24.5 ± 2.8 to 16.4 ± 5.5mmHg) and medications were reduced by an average of 0.8 per patient (2.2 ± 1.1 to 1.4 + 1.3, P = 0.002) at 12 months. Complications included transient IOP increases, hyphema, and cataract progression, with 18.5% of patients requiring secondary glaucoma surgical treatment[55]*. Results of the COMPASS trial are not yet available.

3.2 iStent Supra®

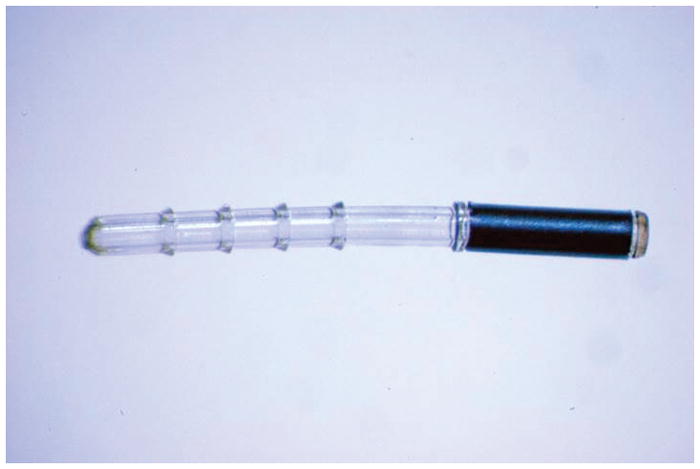

The iStent Supra® is also inserted through an ab interno incision and placed into the suprachoroidal space (Figure 5). It is not FDA-approved but does have CE approval. There are not yet any published trials, but the device is currently undergoing Phase III clinical trials in the US in conjunction with CE/IOL[56]. Preliminary studies show a 98% success rate (reduction in IOP ≥20%) when combined with post-operative travoprost[57].

Figure 5. The iStent Supra®.

Used with permission from Glaukos Corporation

4.0 Reducing aqueous production (Endocyclophotocoagulation)

Endocyclophotocoagulation (ECP) is an FDA approved cyclodestructive procedure that functions via diode laser coagulation of the ciliary processes through a clear corneal incision, thus reducing aqueous production. This is in contrast to the more traditional, transscleral approach (TCP), which is performed externally without an incision and conventionally used for end-stage glaucoma. After filling the anterior chamber and ciliary sulcus with OVD, the endoscope probe (Endo Optiks, Little Silver, New Jersey, US) is inserted through the incision, and the anterior ciliary processes are visualized and treated with the laser. The power of the laser can range from 0.25 to 0.4 W and ablate anywhere from 270 to 360 degrees[58]. Characteristic whitening and contraction of the ciliary processes are observed, signifying the endpoint for treatment. The IOP reduction may or may not correlate with the number of laser burns but does correlate with the extent of clock hours treated[59]. ECP can be used for IOP lowering in both open and narrow angle glaucoma. The thermal shrinking caused by the treatment can be used to reshape the angle and treat refractory plateau iris and narrow angle[60]. In the modification of the procedure via a pars plana approach, “ECP-Plus”, both the anterior and posterior ciliary processes and the pars plana are treated in vitrectomized eyes allowing for increased lowering of IOP. This technique allows for treatment of eyes where the view through the cornea may be compromised due to scarring. No randomized trials exist comparing ECP to TCP, but the complication rates are observed to be lower in ECP when comparing individual studies[59]. Gayton et al observed decreased inflammation with ECP and CE/IOL compared to trabeculectomy and CE/IOL[61]. Lima et al showed similar outcomes and decreased complications when ECP was compared alone to a tube shunt procedure[62].

Francis et al’s prospective non-randomized matched control study compared ECP and CE/IOL with CE/IOL alone in patients with medically controlled glaucoma[63]*. At two years, the study group had a success rate of 77.5% and the control group, 23.8%, where success was defined as IOP >5mmHg and <21mmHg with a 20% reduction in IOP without additional glaucoma surgery, medications, or loss of light perception. There was a significant difference between the IOP reductions in the groups; in the study group the IOP was reduced by 10.1% (18.1 ±3.0 to 16.0 ±3.3mmHg) and the control group by 0.8% (18.1 ±3.0 to 17.3 ±3.2mmHg) (P = 0.004) at two years. Medications decreased by 1.1±0.9 in the study group (1.5±0.8 to 0.4±0.7, P<0.001) compared to 0.4±0.8 in the control group (2.4 ±1.0 to 2.0 ±1.0) (P<0.001). Complications were minimal, equal between groups, and included two cases of anterior chamber hemorrhage in the treatment group. Additionally, in eyes that had previously undergone incisional glaucoma surgery, ECP was an effective treatment in place of additional incisional surgery[64].

Several recent retrospective chart reviews and case series show varying success rates, decreases in IOP, and medication use with ECP combined with CE/IOL[65],[66],[67]. Seigel et al evaluated ECP and CE/IOL versus CE/IOL alone. At 36 months, they showed a complete success rate of 61.4% in the study group and 23.3% in the control group with success defined as IOP no higher than baseline with a decrease of at least one glaucoma medication. While IOP reduction was not significant between groups (P = 0.34), the medication reduction in the study group was significant (1.3±0.6 to 0.2±0.59, P < 0.001). Complications included four patients developing cystoid macular edema (CME), two patients with a retinal detachment, and one penetrating keratoplasty in the study group. One patient in the CE/IOL alone group developed CME[68].

ECP can be used for both early to moderate glaucoma and refractory glaucoma, as it showed efficacy in the latter population[64]. For refractory patients, ECP performed through the pars plana as “ECP-Plus” achieved IOP reduction of up to 63% at 12 months. Sixteen percent (8/50 eyes) developed complications (CME, hyphema, fibrinous uveitis, in addition to hypotony and choroidal detachments) potentially making it a less desirable option in treatment-naïve patients[69].

5.0 Subconjunctival filtration (XEN Gel Stent)

The XEN Gel Stent (Allergan, Parsippany, NJ, US) functions via subconjunctival filtration. It shunts aqueous fluid from the anterior chamber to the subconjunctival space, similar to trabeculectomy and tube shunts, procedures which create both an artificial drainage pathway for aqueous outflow and a bleb. The XEN Gel Stent has the advantage of avoiding disruption of the conjunctiva. This collagen implant is 6mm in length and is composed of porcine gelatin that is cross-linked with glutaraldehyde. It was studied with different sized lumens: 45 μm, 63 μm, and 140 μm, but the 45 μm is now the only lumen size that progressed to clinical trials. XEN45 shows increased flexibility when compared to conventional silicone tubes employed in tube shunts which allows for reduced interplay of forces between the implant and other tissue layers of the eye[70]. The small diameter may protect against hypotony in the early postoperative period primarily by limiting the amount of aqueous outflow via the Hagen-Poiseuille law[71]. Use of the Xen Gel Stent may combined with cataract surgery and an antimetabolite, such as mitomycin-C (MMC). Animal studies showed the long-term viability and stability of the implant[72]. No clinical trials using this stent are published to date, and it is not approved by the FDA, but the stent has CE approval, and Phase III trials are ongoing for XEN45[73] in the US.

Sheybani et al published a nonrandomized prospective pilot study on 37 eyes undergoing XEN140 and XEN63 placement concomitantly with CE/IOL without the use of a metabolite. This study showed a complete success rate of 47.1% and a qualified success rate of 85.3% at 12 months, with a mean reduction in IOP of 7.0mmHg (22.4 ±4.2 to 15.4 ±3.0mmHg, P < 0.0001). Complete success was defined as IOP <18mmHg and a >20% reduction in IOP at 12 months without glaucoma medication, and qualified success was defined similarly, but with or without glaucoma medications. This study also showed a reduction of medication classes by 1.6 (2.5 ± 1.4 to 0.9 ± 1.0) and almost 50% of patients were off all medications at 12 months. Several patients who received the XEN140 required anterior chamber refilling with OVD and almost one-third of patients had early postoperative hypotony (35%) which decreased to 10.8% at one week. Thirty two percent (n=12) required bleb needling, half with MMC and half with 5-fluorouracil[74]*. Another nonrandomized prospective study by Sheybani et al evaluated 49 eyes with implantation of the XEN140 alone, where 45% of the cohort had prior glaucoma surgery. This study defined success similarly with 40% and 89% completed and qualified success rates, respectively. They also showed an 8.4mmg reduction in IOP (23.1 ±4.1 to 14.7 ±3.7 mmHg, P < 0.001) and a reduction in medications from 3.0 to 1.3 (P<0.001) with 42% of patients off medications completely at 12 months. Almost half of the patients required bleb needling (47%, n=21) and 3 with MMC. Several patients required anterior chamber refilling with OVD[75]. However, these studies evaluate the use of XEN63 and XEN140, which are not currently recommended by the manufacturer.

Few prospective studies evaluate the efficacy of the XEN45, and only when the implant is combined with CE/IOL. Most recently, Perez-Torregrosa et al published a prospective study with XEN45 implantation in 30 eyes combined with CE/IOL and MMC. IOP decreased from a medicated baseline by 34% (21.2±3.4 to 15.03±2.47mmHg, P<0.001) at 12 months with an almost 95% (3.07±0.69 to 0.17 +0.65, P<0.001) decrease in medications with minimal complications. IOP reduction of ≤18mmHg without medications was achieved in 90% of patients[76]. Initial data by Sheybani and Ahmed from a prospective, non-randomized study on 31 eyes that underwent XEN45 implantation with MMC and CE/IOL, showed an IOP decrease from 20.8 ±4.6mmHg to 13.1 ±3.6 mmHg (P < 0.001) at 12 months. They also showed reduction in medications from 2.7 ±1 to 0.9 ±1.1 (P < 0.001) and no complications[77].

5.1 InnFocus Microshunt

We will not discuss in detail the InnFocus Microshunt (InnFocus, Miami, FL, US) which functions via subconjunctival filtration as insertion of this microtube involves a conjunctival flap and dissection and is more similar to conventional trabeculectomy than what we defined as MIGS[78].

6.0 Conclusion

Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgery offers new, lower risk, potentially effective treatments for glaucoma patients. Increasing trabecular outflow by bypassing the trabecular meshwork, increasing outflow via suprachoroidal shunts, reducing aqueous production, and subconjunctival filtration are the mechanisms of action of these novel procedures. In the past decade, MIGS has grown and continues to grow in popularity and shows great potential for glaucoma therapy.

7.0 Expert Opinion

MIGS success is also related to its ability to overcome many of the barriers of glaucoma treatment, such as poor adherence and the high risk profile of incisional surgery. Non-adherence to medical therapy is estimated to be as high as 60%[79], and many patients demonstrating difficulty with drop administration[80]. Furthermore, side effects of medical therapy induce ocular irritation and symptoms in a large proportion of patients[81]. For older patients with glaucoma, microinvasive glaucoma surgery may be the best option to avoid the above mentioned issues with adherence, drop instillation, medication side effects, and the higher risk of traditional incisional glaucoma surgery. Furthermore, the procedures are quick and cost-effective when compared to medical therapy[82]. MIGS procedures are increasingly used in clinical practice with a 99% increase in ECP from 2005 to 2012 at which time there has been a continued decrease in trabeculectomy[83].

While traditional incisional procedures, such as trabeculectomy and tube shunts, are known to lower IOP[84][85][86] they are plagued by multiple complications secondary to invasive fistulation and creation of the subconjunctival bleb. To our knowledge there are no studies that directly compare the overall complication rates of MIGS and traditional glaucoma procedures, however, available studies employing MIGS demonstrate an improved risk profile when compared to traditional glaucoma surgery. Furthermore, with few exceptions, MIGS surgeries generally spare the conjunctiva and allow for later, more invasive glaucoma procedures, if necessary. We note that we have not included the SOLX® Gold Shunt (SOLX, Waltham, MA, US), the Aquashunt™ (OPKO Health Inc., Miami, FL, US), the STARflo™ Glaucoma Implant (iSTAR Medical SA, Wavre, Belgium), or the InnFocus Microshunt (InnFocus, Miami, FL, US) devices here as they require conjunctival dissection and do not meet our definition of MIGS. A potential advantage of MIGS is the possibility of combining multiple MIGS procedures with minimal risk and increased efficacy. Future work may focus on assessing the efficacy of such combined procedures. There are few studies that attempt to directly compare the efficacy of individual MIGS procedures[87].

While current evidence shows a modest effect of MIGS procedures, even a small additional decrease in IOP can have a significant effect. Prior work has shown that each additional millimeter of mercury results in an 11% increase in the risk of glaucoma progression[88]*. Most MIGS studies are combined with cataract surgery, which can lower IOP in the short term by 2–4mmHg[27]*[89][90]. However, this effect wanes over time, thus studies focusing on long term data will be important moving forward.

Importantly, with the exception of Glaukos’ iStent®, few randomized control trials exist for MIGS procedures. The majority of the data outlined in this review is based on retrospective studies, which is not ideal for elucidating the success of these procedures. However, given the promising results shown by many of these retrospective studies, this review may serve as a call for randomized control trials.

While, some MIGS procedures, particularly trabecular bypass procedures require a higher degree of technical skill for effective placement of the devices, advanced imaging techniques may improve the ease and efficacy of these procedures. On-going studies on real-time visualization of downstream collector channels may allow for intelligent placement of trabecular by-pass implants such as the iStent® and Hydrus in the future[91]. This may negate the need for multiple implants.

MIGS is a quickly growing area of glaucoma treatment, with earlier procedures demonstrating established efficacy and newer devices and procedures showing promising results. Further study with randomized control trials of each procedure, longer follow up, as well as head-to-head comparisons of MIGS procedures are needed.

8.0 Five-Year View

Given the rapidity of progress in techniques, technology, research, and development of devices, these authors believe that MIGS will have a significant impact on glaucoma care in five years. This time will allow more randomized clinical trials to shed light on the efficacy of commonly performed MIGS procedures. MIGS will likely establish itself in the spectrum of glaucoma treatment as an option for patients with moderate glaucoma, especially those with cataracts. More new procedures and devices will likely develop over the next several years, however, the most important task will be to evaluate the research associated with currently established MIGS procedures.

9.0 Key Issues.

Over the past two decades, Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) has evolved as a significant surgical option for glaucoma patients.

MIGS refers to any surgical manipulation or device implantation that involves a self-sealing, clear corneal incision (ab interno) that inflicts minimal trauma to surrounding tissues, with short surgical time, and results in a decrease in intraocular pressure (IOP) with a quick recovery.

The mechanisms of action for MIGS procedures are: (1) increasing trabecular outflow by bypassing the trabecular meshwork, (2) increasing outflow via suprachoroidal shunts, (3) reducing aqueous production, and (4) subconjunctival filtration.

MIGS procedures have several benefits, including an improved safety profile, an ability to combine the procedures with cataract surgery, and a decreased need for patient compliance and dependence on topical glaucoma medical therapies.

While MIGS procedures demonstrate efficacy in the current literature, few randomized control trials exist and thus more study is needed.

Given the fast-paced growth of procedures and devices, MIGS will likely continue to increase in popularity among patients and ophthalmologists.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: Osamah J. Saeedi is funded by a NIH K23 Career Development Award (1 K23 EY025014-01A1). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest regarding this work. The authors have no acknowledgements.

References

- 1.Wolner B, Liebmann JM, Sassani JW, et al. Late bleb-related endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy with adjunctive 5-fluorouracil. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1053–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higginbotham EJ, Stevens RK, Musch DC, et al. Bleb-related endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:650–656. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBry PW, Perkins TW, Heatley G, et al. Incidence of late-onset bleb-related complications following trabeculectomy with mitomycin. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960) 2002;120:297–300. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *4.Saheb H, Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, et al. Outcomes of glaucoma reoperations in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:1179–1189e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.02.027. This study outlines the results of the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis BA, Minckler D, Dustin L, et al. Combined cataract extraction and trabeculotomy by the internal approach for coexisting cataract and open-angle glaucoma: initial results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minckler D, Mosaed S, Dustin L, et al. Trabectome (trabeculectomy-internal approach): additional experience and extended follow-up. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2008;106:149–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahuja Y, Ma Khin Pyi S, Malihi M, et al. Clinical results of ab interno trabeculotomy using the trabectome for open-angle glaucoma: the Mayo Clinic series in Rochester, Minnesota. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156:927–935e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minckler DS, Baerveldt G, Alfaro MR, et al. Clinical results with the Trabectome for treatment of open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:962–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minckler D, Baerveldt G, Ramirez MA, et al. Clinical results with the Trabectome, a novel surgical device for treatment of open-angle glaucoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:40–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda M, Watanabe M, Ichikawa K. Evaluation of trabectome in open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2013;22:205–208. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3182311b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ting JLM, Damji KF, Stiles MC, et al. Ab interno trabeculectomy: outcomes in exfoliation versus primary open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan JF, Wecker T, van Oterendorp C, et al. Trabectome surgery for primary and secondary open angle glaucomas. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:2753–2760. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2500-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahuja Y, Malihi M, Sit AJ. Delayed-onset symptomatic hyphema after ab interno trabeculotomy surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:476–480e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **14.Jea SY, Francis BA, Vakili G, et al. Ab interno trabeculectomy versus trabeculectomy for open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.046. This study describes the comparison of ab interno trabeculectomy and traditional trabeculectomy for treatment of glaucoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkisian SR, Allan EJ, Ding K, Dvorak J, Badawi DY. New Way for Ab Interno Trabeculotomy: Initial Results. Paper session presented at: Paper session presented at: American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) & American Society of Ophthalmic Administrators (ASOA) Symposium & Congress; Apr 17, 2015. Available at: https://ascrs.confex.com/ascrs/15am/webprogram/Paper15533.html. [Google Scholar]

- *16.Seibold LK, Soohoo JR, Ammar DA, et al. Preclinical investigation of ab interno trabeculectomy using a novel dual-blade device. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:524–529e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.09.023. This article describes preclinical studies of the Kahook dual blade. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *17.Chin S, Nitta T, Shinmei Y, et al. Reduction of intraocular pressure using a modified 360-degree suture trabeculotomy technique in primary and secondary open-angle glaucoma: a pilot study. J Glaucoma. 2012;21:401–407. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318218240c. This study notes the efficacy of gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculectomy (GATT) in adult glaucoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grover DS, Fellman RL. Gonioscopy-assisted Transluminal Trabeculotomy (GATT): Thermal Suture Modification With a Dye-stained Rounded Tip. J Glaucoma. 2016;25:501–504. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *19.Grover DS, Godfrey DG, Smith O, et al. Gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy, ab interno trabeculotomy: technique report and preliminary results. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.001. This article outlines the efficacy of gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculectomy (GATT) in patients with primary open angle glaucoma and secondary glaucoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover DS, Smith O, Fellman RL, et al. Gonioscopy assisted transluminal trabeculotomy: an ab interno circumferential trabeculotomy for the treatment of primary congenital glaucoma and juvenile open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:1092–1096. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khaimi MA. Canaloplasty: A Minimally Invasive and Maximally Effective Glaucoma Treatment. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:485065. doi: 10.1155/2015/485065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pache M, Wilmsmeyer S, Funk J. Laser surgery for glaucoma: excimer-laser trabeculotomy. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2006;223:303–307. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilmsmeyer S, Philippin H, Funk J. Excimer laser trabeculotomy: a new, minimally invasive procedure for patients with glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:670–676. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0136-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.Babighian S, Caretti L, Tavolato M, et al. Excimer laser trabeculotomy vs 180 degrees selective laser trabeculoplasty in primary open-angle glaucoma. A 2-year randomized, controlled trial. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:632–638. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.172. This study is one of the few randomized control trials to evaluate eximer laser trabeculotomy as a treatment for glaucoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Toteberg-Harms M, Hanson JV, Funk J. Cataract surgery combined with excimer laser trabeculotomy to lower intraocular pressure: effectiveness dependent on preoperative IOP. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013;13:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-13-24. This article evaluates the efficacy of eximer laser trabeculotomy in patients with higher preoperative intra-ocular pressures. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, et al. Treatment outcomes in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study after five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:789–803 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *27.DeVience E, Chaudhry S, Saeedi OJ. Effect of intraoperative factors on IOP reduction after phacoemulsification. Int Ophthalmol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0230-7. This article evaluates the efficacy of cataract surgery in patients with higher preoperative intra-ocular pressures. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter KS, Fjield T, Heitzmann H, et al. Characterization of micro-invasive trabecular bypass stents by ex vivo perfusion and computational flow modeling. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:499–506. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S56245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bahler CK, Smedley GT, Zhou J, et al. Trabecular bypass stents decrease intraocular pressure in cultured human anterior segments. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:988–994. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez-Barrientos Y, Garcia-Feijoo J, Martinez-de-la-Casa JM, et al. Fluorophotometric study of the effect of the glaukos trabecular microbypass stent on aqueous humor dynamics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3327–3332. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *31.Samuelson TW, Katz LJ, Wells JM, et al. Randomized evaluation of the trabecular micro-bypass stent with phacoemulsification in patients with glaucoma and cataract. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.07.007. This study reports the initial results of the iStent Study Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *32.Craven ER, Katz LJ, Wells JM, et al. Cataract surgery with trabecular micro-bypass stent implantation in patients with mild-to-moderate open-angle glaucoma and cataract: two-year follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.03.025. This study reports the results of the iStent Study Group at two years. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Neuhann TH. Trabecular micro-bypass stent implantation during small-incision cataract surgery for open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension: Long-term results. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:2664–2671. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.06.032. This article reports the efficacy of insertion of a single iStent® with cataract surgery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fea AM. Phacoemulsification versus phacoemulsification with micro-bypass stent implantation in primary open-angle glaucoma: randomized double-masked clinical trial. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fea AM, Consolandi G, Zola M, et al. Micro-Bypass Implantation for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Combined with Phacoemulsification: 4-Year Follow-Up. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:795357. doi: 10.1155/2015/795357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belovay GW, Naqi A, Chan BJ, et al. Using multiple trabecular micro-bypass stents in cataract patients to treat open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1911–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *37.Katz LJ, Erb C, Carceller GA, et al. Prospective, randomized study of one, two, or three trabecular bypass stents in open-angle glaucoma subjects on topical hypotensive medication. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:2313–2320. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S96695. This article describes the ability of the iStent® to lower mean intra-ocular pressure with each additional stent. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. Subjects With Open-angle Glaucoma, Pseudoexfoliative Glaucoma, or Ocular Hypertension Naïve to Medical and Surgical Therapy, Treated With Two Trabecular Micro-bypass Stents (iStent Inject) or Travoprost. NCT01444040 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01444040.

- 39.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. GTS400 Stent Implantation in Conjunction With Cataract Surgery in Subjects With Open-angle Glaucoma. NCT01052558 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01052558.

- 40.Bahler CK, Hann CR, Fjield T, et al. Second-generation trabecular meshwork bypass stent (iStent inject) increases outflow facility in cultured human anterior segments. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:1206–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *41.Voskanyan L, Garcia-Feijoo J, Belda JI, et al. Prospective, unmasked evaluation of the iStent(R) inject system for open-angle glaucoma: synergy trial. Adv Ther. 2014;31:189–201. doi: 10.1007/s12325-014-0095-y. This article describes the results of a clinical trial with patients undergoing implantation of two iStent injects®. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fea AM, Belda JI, Rekas M, et al. Prospective unmasked randomized evaluation of the iStent inject (R) versus two ocular hypotensive agents in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:875–882. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S59932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *43.Klamann MKJ, Gonnermann J, Pahlitzsch M, et al. iStent inject in phakic open angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;253:941–947. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3014-2. This article describes the efficacy two iStent injects® in lowering intra-ocular pressure in patients with primary open angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan F, Schieber AT, Camras LJ, et al. Mathematical Modeling of Outflow Facility Increase With Trabecular Meshwork Bypass and Schlemm Canal Dilation. J Glaucoma. 2016;25:355–364. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hays CL, Gulati V, Fan S, et al. Improvement in outflow facility by two novel microinvasive glaucoma surgery implants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:1893–1900. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. Compare the Hydrus Microstent(TM) to the iStent for Lowering IOP in Glaucoma Patients Having Cataract Surgery (Hydrus III) NCT02024464 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02024464.

- 47.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. Comparing Effectiveness of the Hydrus Microstent (TM) to Two iStents to Lower IOP in Phakic Eyes (Hydrus V) NCT02023242 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02023242.

- 48.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. Safety & Effectiveness Study of the Hydrus Device for Lowering IOP in Glaucoma Patients Undergoing Cataract Surgery. NCT01539239 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01539239.

- 49.Gandolfi SA, Ungaro N, Ghirardini S, et al. Comparison of Surgical Outcomes between Canaloplasty and Schlemm’s Canal Scaffold at 24 Months’ Follow-Up. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:3410469. doi: 10.1155/2016/3410469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *50.Pfeiffer N, Garcia-Feijoo J, Martinez-de-la-Casa JM, et al. A Randomized Trial of a Schlemm’s Canal Microstent with Phacoemulsification for Reducing Intraocular Pressure in Open-Angle Glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.031. This article describes a clinical trial of patients undergoing Hydrus™ Microstent placement along with cataract surgery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. CyPass Clinical Experience (CyCLE) study. NCT01097174 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01097174.

- 52.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. Study of an Implantable Device for Lowering Intraocular Pressure in Glaucoma Patients Undergoing Cataract Surgery (COMPASS) NCT01085357 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01085357.

- *53.Hoeh H, Ahmed IIK, Grisanti S, et al. Early postoperative safety and surgical outcomes after implantation of a suprachoroidal micro-stent for the treatment of open-angle glaucoma concomitant with cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.10.040. This study describes the safety profile of the CyPass® Micro-stent. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *54.Hoeh H, Vold SD, Ahmed IK, et al. Initial Clinical Experience With the CyPass Micro-Stent: Safety and Surgical Outcomes of a Novel Supraciliary Microstent. J Glaucoma. 2016;25:106–112. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000134. This study describes the efficacy and safety of the CyPass® Micro-stent. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *55.Garcia-Feijoo J, Rau M, Grisanti S, et al. Supraciliary Micro-stent Implantation for Open-Angle Glaucoma Failing Topical Therapy: 1-Year Results of a Multicenter Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:1075–1081e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.02.018. This article describes the results of the DUETTE clinical trial for the CyPass® Micro-stent. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. Multicenter Investigation of the Glaukos® Suprachoroidal Stent Model G3 In Conjunction With Cataract Surgery. NCT01461278 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01461278.

- 57.Jünemann A. Twelve-month Outcomes Following Ab Interno Implantation of Suprachoroidal Stent and Posteroperative Administration of Travoprost to Treat Open Angle Glaucoma. Poster session presented at European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS); Oct 2013; Available at: http://escrs.org/amsterdam2013/programme/posters-details.asp?id=19512. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Francis BA, Kwon J, Fellman R, et al. Endoscopic ophthalmic surgery of the anterior segment. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ishida K. Update on results and complications of cyclophotocoagulation. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24:102–110. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835d9335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Francis BA, Pouw A, Jenkins D, et al. Endoscopic Cycloplasty (ECPL) and Lens Extraction in the Treatment of Severe Plateau Iris Syndrome. J Glaucoma. 2016;25:e128–33. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gayton JL, Van Der Karr M, Sanders V. Combined cataract and glaucoma surgery: trabeculectomy versus endoscopic laser cycloablation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:1214–1219. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lima FE, Magacho L, Carvalho DM, et al. A prospective, comparative study between endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation and the Ahmed drainage implant in refractory glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2004;13:233–237. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200406000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *63.Francis BA, Berke SJ, Dustin L, et al. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation combined with phacoemulsification versus phacoemulsification alone in medically controlled glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40:1313–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.06.021. This study describes the comparison of the efficacy of endocylophotocoagluation with cataract surgery to cataract surgery alone. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Francis BA, Kawji AS, Vo NT, et al. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) in the management of uncontrolled glaucoma with prior aqueous tube shunt. J Glaucoma. 2011;20:523–527. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181f46337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morales J, Al Qahtani M, Khandekar R, et al. Intraocular Pressure Following Phacoemulsification and Endoscopic Cyclophotocoagulation for Advanced Glaucoma: 1-Year Outcomes. J Glaucoma. 2015;24:e157–62. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clement CI, Kampougeris G, Ahmed F, et al. Combining phacoemulsification with endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation to manage cataract and glaucoma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2013;41:546–551. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roberts SJ, Mulvahill M, SooHoo JR, et al. Efficacy of combined cataract extraction and endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation for the reduction of intraocular pressure and medication burden. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9:693–698. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2016.05.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Siegel MJ, Boling WS, Faridi OS, et al. Combined endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation and phacoemulsification versus phacoemulsification alone in the treatment of mild to moderate glaucoma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2015;43:531–539. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tan JCH, Francis BA, Noecker R, et al. Endoscopic Cyclophotocoagulation and Pars Plana Ablation (ECP-plus) to Treat Refractory Glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2016;25:e117–22. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lewis RA. Ab interno approach to the subconjunctival space using a collagen glaucoma stent. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40:1301–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sheybani A, Reitsamer H, Ahmed IIK. Fluid Dynamics of a Novel Micro-Fistula Implant for the Surgical Treatment of Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:4789–4795. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu D-Y, Morgan WH, Sun X, et al. The critical role of the conjunctiva in glaucoma filtration surgery. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:303–328. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials. AqueSys XEN 45 Glaucoma Implant in Refractory Glaucoma. NCT02036541 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jan 1]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02036541.

- *74.Sheybani A, Lenzhofer M, Hohensinn M, et al. Phacoemulsification combined with a new ab interno gel stent to treat open-angle glaucoma: Pilot study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:1905–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.01.019. This article describes the efficacy of the XEN gel stent along with cataract surgery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sheybani A, Dick B, Ahmed IIK. Early Clinical Results of a Novel Ab Interno Gel Stent for the Surgical Treatment of Open-angle Glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2015 doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perez-Torregrosa VT, Olate-Perez A, Cerda-Ibanez M, et al. Combined phacoemulsification and XEN45 surgery from a temporal approach and 2 incisions. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sheybani A, Ahmed I. Ab interno gelatin stent with mitomycin-C combined with cataract surgery for treatment of open-angle glaucoma: 1-year results. Paper session presented at: Paper session presented at: American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) & American Society of Ophthalmic Administrators (ASOA) Symposium & Congress; April 18, 2015; Available at: https://ascrs.confex.com/ascrs/15am/webprogram/Paper15503.html. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pinchuk L, Riss I, Batlle JF, et al. The use of poly(styrene-block-isobutylene-block-styrene) as a microshunt to treat glaucoma. Regen Biomater. 2016;3:137–142. doi: 10.1093/rb/rbw005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schwartz GF, Quigley HA. Adherence and persistence with glaucoma therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(Suppl1):S57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hennessy AL, Katz J, Covert D, et al. Videotaped evaluation of eyedrop instillation in glaucoma patients with visual impairment or moderate to severe visual field loss. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2345–2352. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stewart WC, Stewart JA, Nelson LA. Ocular surface disease in patients with ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Curr Eye Res. 2011;36:391–398. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2011.562340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Iordanous Y, Kent JS, Hutnik CML, et al. Projected cost comparison of Trabectome, iStent, and endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation versus glaucoma medication in the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. J Glaucoma. 2014;23:e112–8. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31829d9bc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arora KS, Robin AL, Corcoran KJ, et al. Use of Various Glaucoma Surgeries and Procedures in Medicare Beneficiaries from 1994 to 2012. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1615–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.The AGIS Investigators. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Feiner L, Piltz-Seymour JR. Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study: a summary of results to date. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14:106–111. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gedde SJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, et al. Postoperative complications in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study during five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:804–814e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khan M, Saheb H, Neelakantan A, et al. Efficacy and safety of combined cataract surgery with 2 trabecular microbypass stents versus ab interno trabeculotomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:1716–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *88.Bengtsson B, Leske MC, Hyman L, et al. Fluctuation of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.060. This article outlines the results of the early manifest glaucoma trial. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poley BJ, Lindstrom RL, Samuelson TW. Long-term effects of phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation in normotensive and ocular hypertensive eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:735–742. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mansberger SL, Gordon MO, Jampel H, et al. Reduction in intraocular pressure after cataract extraction: the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1826–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Saraswathy S, Tan JCH, Yu F, et al. Aqueous Angiography: Real-Time and Physiologic Aqueous Humor Outflow Imaging. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]