Abstract

In this study, the effects of various ratios of cow milk to soy milk (100:0, 75:25, 50:50, 25:75, and 0:100) and three types of commercial culture composition (ABY-1, MY-720, and YO-Mix 210; all of them containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis, and yogurt cultures) on the biochemical, microbiological, and sensory characteristics of a probiotic fermented composite drink during incubation and refrigerated storage were investigated. It was found that the shortest fermentation time, greatest mean pH drop rate, and mean acidity increase rate were related to the 50:50/ABY treatment. 25:75/ABY and 25:75/MY treatments exhibited the highest viability of B. bifidum and/or L. acidophilus at the end of 21 days of refrigerated storage. The influence of the type of starter culture composition on the sensory properties of the final products was not significant. Based on microbial and sensory evaluations, using the 50:50 ratio with each type of culture composition was considered as the most suitable treatment.

Keywords: Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Probiotic, Soy milk, Viability

Introduction

In recent years, the consumers have become aware of functional foods as well as their health benefits. Owing to increasing health concerns, functional foods are garnering substantial attention, and their production growth rate has increased rapidly over the past few years. A considerable part of functional foods belongs to probiotic foods [1]. Probiotics are used to describe a group of live microorganism (bacteria and/or yeasts) that exert beneficial health effects on the host, mainly by balancing the intestinal flora [2, 3]. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria have been considered as potential probiotics, and they exert different beneficial health effects, e.g., anticancer (rescue medicine), antimicrobial, antimutagenic (preventive medicine), anticarcinogenic, antihypertensive, hypocholesterolemic properties, and reduction of lactose intolerance in the host by regulating intestinal microbiota [4–7]. However, probiotics should be alive and consumed in adequate quantities by the host to gain beneficial health effects. Although there is no universal agreement on the recommended consumption levels, generally, the values of 106, 107 and 108 CFU/mL have been considered as the minimum, acceptable, and satisfactory levels, respectively [3, 6].

Dairy probiotic products, especially fermented milks, are highly popular and consumed more than other probiotic food products, and fermentative probiotic products constitute 25% of all dairy probiotic products [3]. Doogh, a traditional yogurt-based beverage, is one of the most consumed drinks in Iran [8]. However, the viability of probiotic microorganisms is decreased by the low pH and high titrable acidity of Doogh during fermentation and storage. It has been reported that soy milk provides a good media for probiotic microorganisms [9]. However, it is not suitable for the traditional yogurt starter L. delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus. Previous studies suggest that soy-based media might possess adequate substrates for the growth of probiotic microorganisms, especially bifidobacteria [10, 11].

Soy-based foods are rich in high-quality nutrients (proteins, essential amino acids, minerals, and vitamins) as well as therapeutic compounds (isoflavone) that provide additional health benefits [12]. Therefore, they may provide a range of health benefits to consumers, such as anticholesterolemic, hypolipidemic, and antiatherogenic properties as well as reduction in allergenicity [13, 14]. The consumption of soy-based products is affected by the emerging off-flavors in the final products and the gastrointestinal discomfort caused by various oligosaccharides, including raffinose and stachyose [9]. Such problems could be overcome by blending cow milk with soy milk and subsequent fermentation. Moreover, the viability of probiotics may be increased by diminishing their reduction potential [15] and increasing the buffering capacity [10]. Thus, the bioavailability of isoflavones, soluble calcium, protein digestion, intestinal health, and the immune system could be improved by fermentation [16, 17]. Therefore, by blending cow milk with soy milk, in addition to the reduction in undesirable flavor, the fermentation time can be reduced due to the presence of sugars such as sucrose. In this study, the effects of the ratio of cow milk to soy milk and the type of commercial starter culture on the biochemical, microbiological, and sensory properties of probiotic soy- and/or milk-based fermented drinks were investigated.

Materials and methods

Commercial starter cultures

Commercial lyophilized cultures, commercially known as ABY-1 (Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5, Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. Lactis (B. lactis) BB-12 and yogurt bacteria (mixed culture of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus); Delvo-YOGMY-720 (L. acidophilus L10, B. lactis B94 and yogurt bacteria); and YO-Mix™210 (L. acidophilus NCFM, B. lactis HN019 and yogurt bacteria) were purchased from Chr. Hansen (Denmark), DSM (Germany), and Danisco (France) respectively. The cultures were maintained at −18 °C up to utilization according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Sugar-free soy milk with 11.3% dry matter was obtained from Maxsoy (Karaj, Iran), and skim milk powder was provided by NZNP (Waikato, New Zealand).

Preparation of fermented composite drinks

Five ratios (on the basis of dry matter) of cow milk to soy milk (100:0, 75:25, 50:50, 25:75, and 0:100) with 6.0% (w/w) dry matter were prepared by mixing reconstituted skim cow milk (for consistency and correctness, it is suggested that skim milk be used instead of cow milk), soy milk, and salt (0.5% w/v). After homogenization, the samples were heated (90 °C for 15 min). Then, different strains of probiotic bacteria with yogurt starter culture (ABY-1, MY-720 or YO-Mix 210) were inoculated to the cooled samples (44 °C) and incubated at 40 °C until a pH 4.4 was achieved. Biochemical properties such as pH, acidity, and redox potential were evaluated every 30 min during fermentation. Mint essence (0.02% w/v) was added to the sample after fermentation. After homogenization, the samples were cooled down to refrigerator temperature (5 °C) and stored for 21 days at this temperature in order to evaluate the experimental parameters every seven days. Treatments were nominated as “cow milk:soy milk/ABY, MY, or YO (i.e., ABY-1, MY-720, or YO-Mix 210, respectively).”

Biochemical analysis

A pH meter (MA235, Mettler, Toledo, Switzerland) was used at room temperature for measuring the pH and redox potential of the samples. To determine the titrable acidity, 10 mL of the sample was mixed with 10 mL of distilled water and titrated with 0.1 N NaOH in the presence of 0.5% (w/v) phenolphthalein [19].

The rates of biochemical changes during storage, including those in the mean pH drop rate, mean acidity increase rate, and mean redox potential increase rate, were calculated according to the method of Mortazavian et al. [19] as follows:

pH drop rate = (final pH value − initial pH value)/storage time.

Acidity increase rate = (final acidity value − initial acidity value)/storage time.

Redox potential increase rate = (final value − initial value)/storage time.

Organic acids (lactic and acetic) were determined via High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; CE 4200-Instrument, Cecil, Milton Technical Center, Cambridge CB46AZ, UK) using a Jasco UV-980 detector at 254 nm and a Nucleosil 100-5 C18 column (Macherey–Nagel, Duren, Germany) according to method of Mortazavian et al. [19] with slight modification. For the extraction of acids, 20 mL of H2SO4 at 0.1 N was added to sample (5 g). After homogenization and centrifugation (3000 × g for 15 min), the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-µm membrane filter and analyzed. The flow rate of the mobile phase (H2SO4 0.009 N) was 0.5 mL/min. Lactic and acetic acid contents were measured using the external standard’s absorbance recorded in the chromatograms.

Microbiological analysis

Selective counting of probiotic bacteria in the presence of yogurt bacteria was performed using an de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS)-bile agar medium (MRS agar and bile were obtained from Merck (Germany) and Sigma-Aldrich (USA), respectively). It has been proved by Mortazavian et al. [20] that MRS–bile is an appropriate medium for the enumeration of mixed probiotic cultures in cultured dairy products. Incubation of the plates was performed aerobically or anaerobically (for Bifidobacterium) at 37 °C for 72 h. The viability proportion index (VPI) of probiotics was estimated using the formula below [18].

VPI = Final cell population (CFU/mL)/Initial cell population (CFU/mL).

Sensory evaluation

Ten trained Maxsoy Co. members served as the panelists and evaluated the sensory properties of the samples at days 0 and 21. White plastic cups containing 20 mL of the drink at 5 °C were given to the panelists. Each panelist received a questionnaire and evaluated each sample based on flavor, mouthfeel (mainly smoothness), and appearance (color) using a five-point scale, i.e., 0 = inconsumable, 1 = unacceptable, 2 = acceptable, 3 = satisfactory, and 4 = excellent. The total scores with a weighted average were calculated by multiplying the given numbers for each sensory parameter in the relevant coefficients, namely 6 for flavor, 3.5 for mouthfeel, and 2 for appearance [7].

Statistical analysis

The design was a “completely randomized design” (Full Factorial). The samples were prepared and analyzed in triplicate, and the significance of the means was determined at the level of 0.05 (p < 0.05) via a two-way ANOVA using the Minitab software (State College, PA, USA).

Results and discussion

Biochemical characteristics of fermented composite drinks at the end of fermentation

The biochemical parameters of the treatments at the end of fermentation are shown in Table 1. The composite sample 50:50/ABY showed the shortest incubation time (260 min), whereas 100:0/MY showed the longest incubation time of 420 min (Table 1). According to our findings, the ratio of 100:0 (cow milk: soy milk) showed the longest incubation time in all types of starters and; this can be attributed to the lack of available forms of vital growing factors. Therefore, in all treatments, the incubation time decreased when the soy milk ratio increased to 50% but subsequently increased with it. The composite sample 50:50/ABY exhibited the largest mean pH drop rate compared with other treatments. The highest mean acidity increase rate was exhibited by the 50:50/ABY, 75:25/ABY, and 50:50/YO treatments. Therefore, soy milk at the ratios of 25 and 50% increased the mean pH drop rate and mean acidity increase rate. However, high ratios (100%) of soy milk and cow milk led to decrease in these parameters. This could be justified by reasoning that the combination of soy milk and cow milk contains more nutrients and makes a composite suitable for starter bacteria [16]. However, a large amount of soy milk (100%) caused a deficiency of cow milk nutrients, which are essential for starter bacteria [21].

Table 1.

Mean pH drop rate, acidity increase rate, redox potential increase rate, incubation time, final acidity, and lactic and acetic acid contents in different treatments during fermentation or at the end of fermentation

| Treatments** | M-pH-DR (pH/min) |

M-A-IR (ºD/min) |

M-RP-IR (mV/min) |

Incubation time (min) | Final acidity (ºD) |

Lactic acid (%) |

Acetic acid (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100:0/ABY | 0.005e | 0.11bc | 0.34e | 390c | 49.4a | 0.35b | 0.14a |

| 75:25/ABY | 0.008b | 0.13ab | 0.44b | 285g | 45.1b | 0.34b | 0.11b |

| 50:50/ABY | 0.009a | 0.14a | 0.48a | 260h | 43.2c | 0.38a | 0.08d |

| 25:75/ABY | 0.007c | 0.12b | 0.42bc | 300f | 41.6d | 0.35b | 0.06e |

| 0:100/ABY | 0.006d | 0.11bc | 0.38d | 330e | 38.5e | 0.31cd | 0.07de |

| 100:0/MY | 0.005e | 0.09d | 0.28g | 420a | 48.5a | 0.36ab | 0.12ab |

| 75:25/MY | 0.007c | 0.11bc | 0.37d | 330e | 45.3b | 0.34b | 0.10bc |

| 50:50/MY | 0.007c | 0.13ab | 0.41c | 300f | 42.5cd | 0.33c | 0.09c |

| 25:75/MY | 0.006d | 0.10c | 0.35e | 360d | 40.4de | 0.36ab | 0.06e |

| 0:100/MY | 0.005e | 0.09d | 0.31f | 405b | 38.0e | 0.30d | 0.08d |

| 100:0/YO | 0.006d | 0.10c | 0.32ef | 390c | 47.3ab | 0.34b | 0.13a |

| 75:25/YO | 0.007c | 0.12b | 0.41c | 300f | 44.5bc | 0.33c | 0.11b |

| 50:50/YO | 0.008b | 0.13ab | 0.38d | 285g | 43.5c | 0.33c | 0.10bc |

| 25:75/YO | 0.007c | 0.11bc | 0.35e | 330e | 40.5de | 0.32c | 0.08d |

| 0:100/YO | 0.006d | 0.10c | 0.36de | 360d | 37.3e | 0.28e | 0.09c |

M-pH-DR = mean pH drop rate; M-A-IR = mean acidity increase rate; M-RP-IR = mean redox potential increase rate. Means in the same column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

** ABY = Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5, Bifdobacterium lactis BB-12, and yogurt bacteria; MY = Lactobacillus acidophilus L10, Bifdobacterium lactis B94, and yogurt bacteria; YO = Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM, Bifdobacterium lactis HN019, and yogurt bacteria

As shown in Table 1, treatments with ratios of 100:0 and 0:100 (cow milk: soy milk) in all types of starters indicated the highest and lowest final acidity at the end of fermentation, respectively. Accordingly, an increase in the ratio of soy milk reduced the amount of final acidity, and the ratio of cow milk to soy milk had more pronounced effects on the biochemical properties during fermentation than the type of culture composition.

Biochemical characteristics of fermented composite drinks during refrigerated storage

There was a direct correlation between acid content in fermented milks and the redox potential value. The viable bifidobacteria population is adversely affected by the redox potential value [22]. Generally, the sensitivity of probiotic bacteria in fermented milks to pH-related stresses (pH value and pH drop rate) is more than the titrable acidity [23]. The viability of probiotics seems to be more affected by the titrable acidity during storage time than during fermentation [22]. Table 2 shows the biochemical parameters and the lactic and acetic acid contents in different treatments during refrigerated storage. According to the results, all 100:0 treatments showed the highest rates of biochemical changes at the first seven days of storage, and it could be attributed to major bacterial activity and the presence of available growth factors in the first seven days of storage. The lowest pH value and highest final acidity at the end of storage significantly occurred during the 100:0/ABY treatment. This may be due to the further post-acidification activity of L. bulgaricus. Treatments with higher ratios of soy milk showed significantly (p < 0.05) lower final acidity at the end of refrigerated storage. The ratio of 0:100 (cow milk: soy milk) showed the fewest biochemical changes possible because the major carbohydrates of soy milk were not degraded by L. bulgaricus during refrigerated storage. Acetic acid showed a lower increase during storage than during fermentation. The results show that increases in the mean pH drop rate and mean acidity increase rate was observed with the addition of 25 and 50% soy milk. Because of the presence of fermentable prebiotic components in soy milk and lactose in cow milk, the content of lactic acid increased during storage. The highest amount of acetic acid was observed in the 100:0 treatments and the lowest were related to the 0:100 treatments (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Biochemical parameters of different treatments during 21 days of refrigerated storage

| Treatments** | M-pH-DR (pH/day) |

M-A-IR (ºD/day) |

M-RP-IR (mV/day) |

Final pH (day21) |

Final acidity (ºD) (day1) |

Final acidity (ºD) (day21) |

Lactic acid (%) |

Acetic acid (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100:0/ABY | 0.016a | 0.35a | 0.52a | 4.08g | 49.4a | 59.4a | 0.43a | 0.16a |

| 75:25/ABY | 0.012b | 0.30bc | 0.43c | 4.18e | 45.1b | 54.2b | 0.42a | 0.12c |

| 50:50/ABY | 0.009c | 0.26d | 0.38d | 4.21de | 43.2c | 50.4bc | 0.40b | 0.10d |

| 25:75/ABY | 0.006de | 0.16h | 0.29f | 4.30b | 41.6d | 48.5cd | 0.37d | 0.11cd |

| 0:100/ABY | 0.002g | 0.13i | 0.21gh | 4.37a | 38.5e | 42.3e | 0.41ab | 0.09e |

| 100:0/MY | 0.005e | 0.28c | 0.43c | 4.14f | 48.5a | 57.2a | 0.43a | 0.14b |

| 75:25/MY | 0.007d | 0.23e | 0.35e | 4.22d | 45.3b | 53.3b | 0.41ab | 0.12c |

| 50:50/MY | 0.007d | 0.19 g | 0.32ef | 4.28bc | 42.5cd | 49.2c | 0.39c | 0.10d |

| 25:75/MY | 0.006de | 0.13i | 0.24g | 4.33ab | 40.4de | 44.6d | 0.35e | 0.09e |

| 0:100/MY | 0.005e | 0.09k | 0.18h | 4.36a | 38.0e | 40.2f | 0.30f | 0.10d |

| 100:0/YO | 0.006de | 0.32b | 0.47b | 4.10g | 47.3ab | 56.4a | 0.42a | 0.14b |

| 75:25/YO | 0.007d | 0.28c | 0.39d | 4.21de | 44.5bc | 52.7bc | 0.41ab | 0.11cd |

| 50:50/YO | 0.008cd | 0.22f | 0.36de | 4.26c | 43.5c | 49.3c | 0.39c | 0.09e |

| 25:75/YO | 0.007d | 0.15hi | 0.25g | 4.30b | 40.5de | 45.1d | 0.35e | 0.10d |

| 0:100/YO | 0.006de | 0.11j | 0.18h | 4.35a | 37.3e | 39.2f | 0.29f | 0.10d |

M-pH-DR = mean pH drop rate; M-A-IR = mean acidity increase rate; M-RP-IR = mean redox potential increase rate. Means in the same column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

** ABY = Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5, Bifdobacterium lactis BB-12, and yogurt bacteria

MY = Lactobacillus acidophilus L10, Bifdobacterium lactis B94, and yogurt bacteria

YO = Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM, Bifdobacterium lactis HN019, and yogurt bacteria

However, the highest content of lactic acid was related to the 100:0 treatments owing to the high amount of lactose and remarkable growth of L. bulgaricus [24] and the lowest one was related to the 0:100 treatments. It has been observed that L. bulgaricus is unable to ferment soy carbohydrates such as sucrose [25]. Donkor et al. [13] found that the content of organic acids slightly increased during 28 days of storage at 4 °C.

Viability of probiotic bacteria at the end of fermentation

The viability of probiotic bacteria and the viability proportion index (VPI) for various treatments at the end of fermentation are shown in Table 3. According to this table, the highest viability of probiotic bacteria in all types of starters belonged to the treatments with the ratio of 50:50 (cow milk: soy milk) (p < 0.05). 50:50/ABY and 50:50/MY treatments showed the highest viability for B. lactis and L. acidophilus, respectively. In fact, cow milk can be enriched to some extent for probiotics with the addition of soy milk, which contains nutrients such as oligosaccharides, peptides, and free amino acids [26, 27]. The ratio of 0:100 (cow milk: soy milk) was attributed to the lowest viability of L. acidophilus and B. lactis; this was observed in 0:100/ABY and 0:100/MY treatments, respectively. The low viability of probiotics in the presence of excessive amounts of soy milk (75 or 100%) could be attributed to the lack of sufficient lactose for fermentation and proliferation of probiotics. Moreover, a decrease in buffering capacity of the medium resulted in a sharp acidification rate during fermentation and low viability of probiotics. These findings are in accordance with the results that Champagne et al. [21] reported in 1996. As shown in Table 2, the viability of probiotics decreased in the samples with a high ratio of cow milk (100%) presumably because of the shortage of available growth factors for probiotic bacteria and over-acidification of L. Bulgaricus. Several authors have reported that probiotics could be degraded by over-acidification, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins derived from the yogurt bacteria, particularly L. bulgaricus [23, 28]. Overall, the growth of probiotics in fermentative dairy products depends on different factors, namely the type of species and their relation, availability of nutrient component, growth factors, inhibitors, inducer, osmotic pressure, dissolved oxygen (especially for Bifidobacteria), inoculation volume, incubation temperature, time of fermentation, and temperature of storage [6, 23].

Table 3.

Viability of probiotic microorganisms and the relevant viability proportion index in different treatments at the end of fermentation

| Treatments** | Initial population (log cfu/mL)*** | Final population (log cfu/mL) |

VPI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | A + B | A | B | A + B | A | B | A + B | |

| 100:0/ABY | 6.22 | 6.44 | 6.63 | 7.30deA | 7.37cA | 7.63b | 12.02 | 8.51 | 10.00 |

| 75:25/ABY | 6.22 | 6.44 | 6.63 | 7.33dB | 7.45bA | 7.69b | 12.88 | 10.23 | 11.48 |

| 50:50/ABY | 6.22 | 6.44 | 6.63 | 7.44bB | 7.65aA | 7.86a | 16.60 | 16.21 | 16.98 |

| 25:75/ABY | 6.22 | 6.44 | 6.63 | 7.25eB | 7.40bcA | 7.63b | 10.71 | 9.12 | 10.00 |

| 0:100/ABY | 6.22 | 6.44 | 6.63 | 7.12fB | 7.47bA | 7.63b | 7.94 | 10.71 | 10.00 |

| 100:0/MY | 6.20 | 6.18 | 6.50 | 7.47abA | 7.38bcB | 7.74ab | 18.62 | 15.81 | 17.37 |

| 75:25/MY | 6.20 | 6.18 | 6.50 | 7.47abA | 7.39cB | 7.73ab | 18.62 | 16.21 | 16.98 |

| 50:50/MY | 6.20 | 6.18 | 6.50 | 7.53aA | 7.45bB | 7.79a | 21.37 | 18.62 | 19.50 |

| 25:75/MY | 6.20 | 6.18 | 6.50 | 7.36cdA | 7.31dA | 7.63b | 14.45 | 13.48 | 13.48 |

| 0:100/MY | 6.20 | 6.18 | 6.50 | 7.13fA | 7.10gA | 7.41d | 8.51 | 8.31 | 8.12 |

| 100:0/YO | 6.22 | 6.20 | 6.53 | 7.42bcA | 7.32 dB | 7.67b | 15.84 | 13.18 | 13.80 |

| 75:25/YO | 6.22 | 6.20 | 6.53 | 7.38cA | 7.23eB | 7.61b | 14.45 | 10.71 | 12.02 |

| 50:50/YO | 6.22 | 6.20 | 6.53 | 7.40cA | 7.32dB | 7.66b | 15.84 | 13.18 | 13.48 |

| 25:75/YO | 6.22 | 6.20 | 6.53 | 7.24eA | 7.15fB | 7.49c | 10.47 | 8.91 | 9.12 |

| 0:100/YO | 6.22 | 6.20 | 6.53 | 7.30deA | 7.17efB | 7.54c | 12.02 | 12.58 | 10.23 |

Means shown with different small and capital letters represent significant differences (p < 0.05) in the same columns (among the treatments) and rows (between the two probiotic bacteria in each treatment), respectively

MY = Lactobacillus acidophilus L10, Bifdobacterium lactis B94, and yogurt bacteria

YO = Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM, Bifdobacterium lactis HN019, and yogurt bacteria

** ABY = Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5, Bifdobacterium lactis BB-12, and yogurt bacteria

*** A = L. acidophilus; B = B. lactis; A + B = total probiotics

Viability of probiotic bacteria during refrigerated storage

The total viable counts of probiotics in different treatments during refrigerated storage at 5 °C are shown in Table 4. The highest viability of L. acidophilus was observed in the 25:75/ABY treatment at days 7, 14, and 21 as well as in the 25:75/MY treatment at the end of 21 days of storage. The lowest viability of L. acidophilus was observed in 100:0/ABY and 75:25/ABY treatments at the end of 21 days. As shown in Table 4, the highest viability of Bifidobacterium in different types of starters belonged to the 50:50/ABY and 25:75/ABY treatments at days 7 and 14, respectively, and to the 25:75/YO and 25:75/ABY treatments at the end of 21 days. Moreover, 0:100/MY and 0:100/YO treatments showed the lowest viability of Bifidobacterium at the end of the first week of storage, and the 100:0/YO treatment showed it at the end of the second week of storage. All the 100:0 treatments showed the lowest viability at the end of 21 days of storage. As mentioned above, the growth of probiotic bacteria depended on different factors. The maximum reduction in the viability of probiotic bacteria was observed at the first seven days of storage in all treatments. One reason could be the lack of available growth factors for probiotics (e.g., lactose, raffinose, and stachyose), over-acidification of L. bulgaricus during refrigerated storage, and inability of probiotic bacteria to adapt to harsh environmental conditions.

Table 4.

Viability of probiotic bacteria in different treatments during refrigerated storage

| Treatments** | Storage time (day)*** | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 14 | 21 | |||||||||

| A | B | A + B | A | B | A + B | A | B | A + B | A | B | A + B | |

| 100:0/ABY | 7.30dA | 7.37cA | 7.63b | 6.88bA | 6.73eB | 7.11bc | 6.24eA | 5.97eB | 6.42e | 5.77eA | 5.39fB | 5.91e |

| 75:25/ABY | 7.33dB | 7.45bA | 7.69b | 6.80bcA | 6.71efB | 7.06c | 6.17eA | 6.00eB | 6.39e | 5.77eA | 5.60 dB | 5.99de |

| 50:50/ABY | 7.44bB | 7.65aA | 7.86a | 6.97aA | 7.02aA | 7.30a | 6.73bA | 6.70aA | 7.02ab | 6.07bA | 5.66cdB | 6.21c |

| 25:75/ABY | 7.25eB | 7.40cA | 7.63b | 6.96aA | 6.82cB | 7.19ab | 6.88aA | 6.68aB | 7.09a | 6.27aA | 6.04aB | 6.47a |

| 0:100/ABY | 7.12fB | 7.47bA | 7.63b | 6.86bA | 6.90abA | 7.18b | 6.68bcA | 6.57bB | 6.93b | 6.00bcA | 5.88bB | 6.24bc |

| 100:0/MY | 7.47abA | 7.38cB | 7.74ab | 6.88bA | 6.71efB | 7.10bc | 6.23eA | 6.00eB | 6.43e | 5.87dA | 5.35fB | 5.98de |

| 75:25/MY | 7.47abA | 7.39cB | 7.73ab | 6.94abA | 6.84cB | 7.19ab | 6.37dA | 6.20dB | 6.59d | 5.92cA | 5.53eB | 6.06d |

| 50:50/MY | 7.53aA | 7.45bB | 7.79a | 6.92abA | 6.87bA | 6.21d | 6.80abA | 6.63aB | 7.02ab | 6.21abA | 5.74cB | 6.34b |

| 25:75/MY | 7.36cdA | 7.31dA | 7.63b | 6.94abA | 6.83cB | 7.19ab | 6.67bcA | 6.55bB | 6.91b | 6.29aA | 5.98aB | 6.46a |

| 0:100/MY | 7.13fA | 7.10gA | 7.41d | 6.77cA | 6.70fA | 7.04c | 6.60cA | 6.28dB | 6.77c | 5.87dA | 5.66cdB | 6.07d |

| 100:0/YO | 7.42bcA | 7.32dB | 7.67b | 6.82bcA | 6.71efB | 7.07c | 6.14fA | 5.92fB | 6.34f | 5.97cA | 5.30fB | 6.05d |

| 75:25/YO | 7.38cA | 7.23eB | 7.61b | 6.88bA | 6.82cA | 7.15b | 6.42dA | 6.26dB | 6.65d | 5.84dA | 5.54eB | 6.01d |

| 50:50/YO | 7.40cA | 7.32dB | 7.66b | 6.87bA | 6.73eB | 7.10bc | 6.68bcA | 6.54bB | 6.91b | 6.04bA | 5.76cB | 6.22c |

| 25:75/YO | 7.24eA | 7.15fB | 7.49c | 6.86bA | 6.79dA | 7.12bc | 6.62cA | 6.56bA | 6.89b | 6.09bA | 5.88bB | 6.30b |

| 0:100/YO | 7.30dA | 7.17fB | 7.54c | 6.77cA | 6.70fA | 7.03c | 6.54cA | 6.35cB | 6.75c | 5.81deA | 5.62 dB | 6.02d |

Means shown with different small and capital letters represent significant differences (p < 0.05) in the same columns (among the treatments) and rows (between the two probiotic bacteria in each treatment), respectively

** ABY = Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5, Bifdobacterium lactis BB-12, and yogurt bacteria; MY = Lactobacillus acidophilus L10, Bifdobacterium lactis B94, and yogurt bacteria; YO = Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM, Bifdobacterium lactis HN019, and yogurt bacteria

*** A = L. acidophilus; B = B. lactis; A + B = total probiotic

The highest decrease in the viability of L. acidophilus was observed in treatments with a ratio of 50:50 (cow milk:soy milk) at the end of 21 days of storage. Furthermore, this treatment showed the highest viability of L. acidophilus than the other types of starters after the first week of storage. This means that treatment with a 50:50 ratio of cow milk to soy milk produced the largest cell growth during fermentation (up to pH 4.4) owing to the synergetic effects of cow milk and soy milk. The minimum reduction in the viability of L. acidophilus was observed in the 0:100 treatments because this ratio caused the lowest cell growth at the end of fermentation possible because of the slow growth of L. bulgaricus and the low final acidity. The 25:75/ABY and 25:75/MY treatments showed the highest viability of L. acidophilus at the end of storage.

The viability of Bifidobacterium at high ratios of soy milk (25:75 and 0:100) was high during storage. The reason is that most of the Bifidobactera strains can ferment sucrose, raffinose, stachyose, and other nutrients derived from soy milk and grow in this suitable medium [9]. Other lactic acid bacteria (LAB) also grow well in soy milk. However, they produce less acid in soy milk than in bovine milk owing to the lack of free monosaccharides and some disaccharides, such as lactose [16]. Additionally, they also produce numerous intracellular and extracellular saccharolytic enzymes during growth, including β-glucosidase, β-galactosidase, α-galactosidase, and α-glucosidase [29, 30]. Consequently, there is potentially a double advantage of health benefits from soy products containing isoflavone aglycones and probiotics. A high viability of Bifidobacterium at these ratios is confirmed by the low amount of acetic acid at the end of fermentation. This observation was consistent with the study of Donkor and Shah [30]. According to Table 3, the 25:75/ABY and 25:75/MY treatments showed the highest viability of B. lactis at the end of storage as only the viable counts of B. lactis were one logarithm more than the standard level of probiotic Doogh (>105 CFU/mL). The lowest viability of Bifidobacterium during storage was observed in the 100:0 (cow milk:soy milk) treatments because of the low pH value and high acidity (post-acidification) obtained at these ratios. Bifidobacteria show strain-specific tolerance to acidic conditions. It has been reported that B. longum shows the best survivability under acidic conditions and in the presence of bile salts [22]. As shown in Table 3, the viability of L. acidophilus was larger than that of Bifidobacterium owing its stronger resistance to organic acids and unfavorable culture conditions. In addition, the formation of hydrogen peroxide by L. bulgaricus was the major factor of losing Bifidobacterium in the mixed culture during refrigerated storage. Medina and Jordano [31] reported that in a mixed culture of probiotics, Bifidobacterium is reduced more than L. acidophilus. In addition to the independent variables considered in the present study, adding 0.5% salt and 0.02% mint essence to all treatments could increase the viability of probiotics (data not shown). Sodium chloride probably exerts stimulatory effects on the activity and growth of probiotic bacteria in fermented milks. It has been found that the addition of 0.5% sodium chloride to Doogh milk leads to an increase in the viability of L. acidophilus and a significant increase in viability of B. lactis at the end of fermentation [32].

The presence of manganese in mint essence could induce the growth of probiotic bacteria, especially Bifidobacterium. Manganese as a constituent of lactate dehydrogenase is an essential factor for the growth of lactic acid bacteria. In fact, probiotics do not have the superoxide dismutase enzyme, which spoils the superoxide anion, and reveals other mechanisms by aggregating manganese ions. Moreover, the presence of salt may significantly reduce the yogurt bacteria activity in comparison with that of probiotics and increase their growth rate [22]. These results are in accordance with Mortazavian observations [32]. Compared with the samples without salt, the higher amount of acetic acid in the samples containing salt portended a higher activity of Bifidobacterium.

Sensory evaluation of fermented composite drinks during refrigerated storage

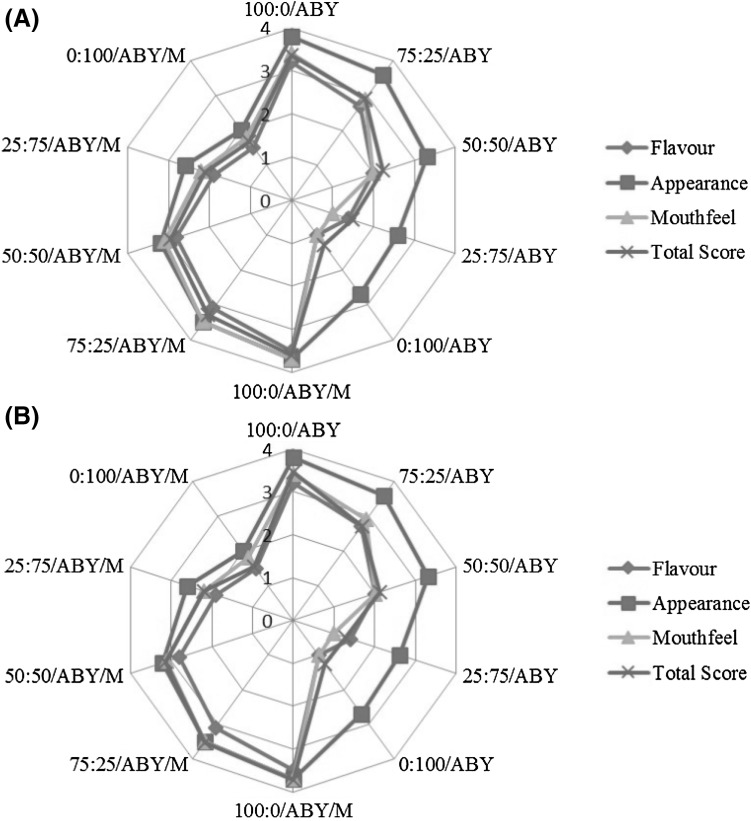

The color differences among the treatments were not distinguished by the panelists, and considering the color properties, all treatments were accepted (data not shown). The type of starter culture had no significant effects on the sensory attributes at the end of fermentation and storage (data not shown). On the basis of this result, one of the starter cultures (ABY-1) was chosen (Fig. 1) to study the effects of the ratio of cow milk to soy milk and that of the addition of mint essence on the sensory properties. Figure 1 presents the results obtained for the sensory characteristics (flavor, mouthfeel, appearance, and total score) of different probiotic fermented drinks using ABY-1 at the start (Fig. 1A) and the end of refrigerated storage (Fig. 1B). The ratios of 0:100 and 100:0 (cow milk:soy milk) showed the lowest and highest total sensory score during refrigerated storage, respectively. However, both of them did not show a significant difference with 50:50 treatments in terms of appearance. The samples containing mint essence (0.02%) as the flavoring agent showed significant differences in flavor and mouthfeel as compared with the samples without mint essence at same ratios. However, there was no significant difference in their appearance (p > 0.05). The results show that mint essence increased the viability of probiotics as well as the total sensory score of drinks.

Fig. 1.

Sensory evaluation of the ABY-1 treatment at 0 days (A) and 21 days (B) of refrigerated storage (M-treatment containing mint essence)

It could be concluded that the biochemical properties of the fermented drinks and the viability of probiotic bacteria were significantly (p < 0.05) affected by both the type of commercial culture composition and the ratio of cow milk to soy milk. The lowest and highest incubation time was related to the 50:50/ABY and 100:0/MY treatments, respectively. The viability of B. bifidum and/or L. acidophilus was the highest in the 25:75/ABY and 25:75/MY treatments at the end of refrigerated storage for 21 days. However, the viability of probiotic bacteria in all treatments was higher than the standard level of probiotic Doogh (105 CFU/ml) at the end of storage. Overall, the viability of probiotic bacteria was increased by the replacement of 25 and 50% of cow milk with soy milk (treatments with ratios of 75:25 and 50:50) owing to the enrichment of cow milk with nutrients such as oligosaccharides, peptides, and free amino acids. The type of probiotic culture had no significant effect on the sensory attributes. The total sensory score decreased with increasing soy milk ratio. The 50:50 treatments with any type of starter culture were found to be the best ones in terms of the different studied aspects, including the functional properties of soy proteins, viability of probiotics, and sensory properties. Investigations using other probiotic culture compositions and evaluation of the content of various oligosaccharides such as raffinose and stachyose after fermentation and during storage are recommended as complementary researches.

Acknowledgements

This work is related to the “additional article grants” (8-1, No. 10641).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Granato D, Branco GF, Nazzaro F, Cruz AG, Faria JA. Functional foods and nondairy probiotic food development: Trends, concepts, and products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F. 2010;9:292–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holzapfel WH, Schillinger U. Introduction to pre- and probiotics. Food Res. Int. 2002;35:109–116. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(01)00171-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohammadi R, Mortazavian AM. Review article: Technological aspects of prebiotics in probiotic fermented milks. Food Rev. Int. 2011;27:192–212. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2010.535235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal R. Probiotics: An emerging food supplement with health benefits. Food Biotechnol. 2005;19:227–246. doi: 10.1080/08905430500316474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beheshtipour H, Mortazavian AM, Mohammadi R, Sohrabvandi S, Khosravi-Darani K. Supplementation of spirulina platensis and chlorella vulgaris algae into probiotic fermented milks. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F. 2013;12:144–154. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lourens-Hattingh A, Viljoen BC. Yogurt as probiotic carrier food. Int. Dairy J. 2001;11(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00036-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouhi M, Mohammadi R, Mortazavian AM, Sarlak Z. Combined effects of replacement of sucrose with d-tagatose and addition of different probiotic strains on quality characteristics of chocolate milk. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2015;95:115–133. doi: 10.1007/s13594-014-0189-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarlak Z, Rouhi M, Mohammadi R, Khaksar R, Mortazavian AM, Sohrabvandi S, Garavand F. Probiotic biological strategies to decontaminate aflatoxin M1 in a traditional Iranian fermented milk drink (Doogh) Food Control. 2017;71:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.06.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scalabrini P, Rossi M, Spettoli P, Matteuzzi D. Characterization of Bifidobacterium strains for use in soymilk fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1998;39:213–219. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(98)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farnworth ER, Mainville I, Desjardins MP, Gardner N, Fliss I, Champagne C. Growth of probiotic bacteria and bifidobacteria in a soy yogurt formulation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;116:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang HJ, Murphy PA. Mass balance study of isoflavones during soybean processing. J. Agr. Food Chem. 1996;44:2377–2383. doi: 10.1021/jf950535p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsangalis D, Ashton JF, McGill AEJ, Shah NP. Enzymic transformation of isoflavone phytoestrogens in soymilk by β-glucosidase-producing bifidobacteria. J. Food Sci. 2002;67:3104–3113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb08866.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donkor ON, Henriksson A, Vasiljevic T, Shah N. α-Galactosidase and proteolytic activities of selected probiotic and dairy cultures in fermented soymilk. Food Chem. 2007;104:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.10.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai TY, Chen LY, Pan TM. Effect of probiotic-fermented, genetically modified soy milk on hypercholesterolemia in hamsters. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2014;47(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heydari S, Mortazavian AM, Ehsani MR, Mohammadifar MA, Ezzatpanah H. Biochemical, microbiological and sensory characteristics of probiotic yogurt containing various prebiotic compounds. Ital. J. Food Sci. 23(2): 153–164 (2011)

- 16.Liu K. Soybeans: chemistry, technology, and utilization. Springer, New York. Chapman and Hall, USA. pp. 415–418 (1997)

- 17.Tsangalis D, Ashton JF, McGill AEJ, Shah NP. Biotransformation of isoflavones by bifidobacteria in fermented soymilk supplemented with d-glucose and L-cysteine. J. Food Sci. 2003;68:623–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb05721.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadi E, Mortazavian AM, Fazeli MR, Ezzatpanah H, Mohammadi R. The effects of inoculant variables on the physicochemical and organoleptic properties of Doogh. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2012;65:274–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0307.2011.00763.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortazavian AM, Khosrokhavar R, Rastegar H, Mortazaei GR. Effects of dry matter standardization order on biochemical and microbiological characteristics of freshly made probiotic Doogh (Iranian fermented milk drink) Ital. J. Food Sci. 2010;22:98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mortazavian AM, Ehsani MR, Sohrabvandi S, Reinheimer JA. MRS-bile agar: its suitability for the enumeration of mixed probiotic cultures in cultured dairy products Milchwissenschaft. 2007;62(3):270–272. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Champagne CP. St.Gelais D, Audet P. Starters produced on whey protein concentrates. Milchwissenschaft. 1996;51:561–564. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamime A, Saarela M, Sondergaard AK, Mistry V, Shah N. Production and maintenance of viability of probiotic micro-organisms in dairy products. pp. 39–72. In: Probiotic dairy products. Tamime A (ed). Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd, UK (2005)

- 23.Korbekandi H, Mortazavian A, Iravani S. Technology and stability of probiotic in fermented milks. Probiotic and Prebiotic Foods. pp. 19-46. In: Probiotic and prebiotic foods: technology, stability and benefits to the human health Shah N (ed). Nova Science Publishing Ltd, USA (2011)

- 24.Liu CF, Hu CL, Chiang SS, Tseng KC, Yu RC, Pan TM. Beneficial preventive effects of gastric mucosal lesion for soy-skim milk fermented by lactic acid bacteria. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2009;57:4433–4438. doi: 10.1021/jf900465c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murti TW, Bouillanne C, Landon M, Smazeaud MJ. Bacterial Growth and Volatile Compounds in Yoghurt-Type Products from Soymilk Containing Bifidobacterium ssp. J. Food Sci. 1993;58:153–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1993.tb03233.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaudreau H, Champagne CP, Jelen P. The use of crude cellular extracts of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus 11842 to stimulate growth of a probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus culture in milk. Enzyme Microb. Techol. 36: 83–90 (2005)

- 27.Pham TT, Shah NP. Effects of lactulose supplementation on the growth of bifidobacteria and biotransformation of isoflavone glycosides to isoflavone aglycones in soymilk. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2008;56:4703–4709. doi: 10.1021/jf072716k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dave RI, Shah NP. Viability of yoghurt and probiotic bacteria in yoghurts made from commercial starter cultures. Int. Dairy J. 1997;7:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(96)00046-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desjardins ML, Roy D, Goulet J. Growth of bifidobacteria and their enzyme profiles. J. Dairy Sci. 1990;73:299–307. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)78673-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donkor ON, Shah NP. Production of β-Glucosidase and Hydrolysis of Isoflavone Phytoestrogens by Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Lactobacillus casei in Soymilk. J. Food Sci. 2008;73:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medina LM, Jordano R. Population dynamics of constitutive microbiota in BAT type fermented milk products. J. Food Protect. 1995;58:70–76. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mortazavian AM. Effects of key formulating factors on qualitative parameters of probiotic Doogh. Ph.D Thesis, University of Tehran, karaj, Iran (2008)