Abstract

Polysaccharide (SJP) was extracted from Sea cucumber, Stichopus japonicas, and its immune-enhancing activities were evaluated in vivo immune-suppressed mice systems. Cyclophosphamide(CY)-treated mice were orally administrated with SJP according to different concentrations. The results showed that administration of SJP significantly increased spleen index without variation of the body weight, compared to only CY treatment group. The proliferation of splenic lymphocyte and NK activity was also stimulated by SJP. In addition, the oral administration of SJP up-regulated COX-2 and TLR-4 as well as cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and IFN-γ, which are secreted from splenic lymphocytes in cyclophosphamide-treated mice. Moreover, our results showed that SJP stimulated macrophages via NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. These findings provided the potential use of SJP as an alternative means under immune-suppressed conditions, and furthermore can be utilized as a functional material for food and pharmaceutical industries.

Keywords: Polysaccharide, Sea cucumber, Immunity, Enhancement, In vivo mice

Introduction

Homeostasis in immune cells is important to maintain cellular process and dietary components are also critical in human physiology associated with immunity and metabolic systems [1, 2]. Recently, considerable attention has been focused on identification of natural products with immune regulation and polysaccharides are one of the crucial nutrients for human health to prevent chronic diseases and physiological problems such as allergies, infections, and autoimmune diseases. Recently a variety of polysaccharides were reported to contain biological activities. Beta-glucan play an important role to prevent and manage respiratory tract infections as a natural immunomodulatory [3]. Hemicellulose also affect immune regulation, bacteria inhibition, and anti-tumor activity [4]. Chitin stimulates human innate immunity to control inflammatory cytokines in occupational allergy [5]. Furthermore, carbohydrates were reported to regulate gut microbiota affecting host immunity and health [6].

Sea cucumbers belonging to Echinodermata, Holothuroidea, are the marine invertebrates which are spread in the benthic areas and deep seas and contain leathery skin and soft body [7]. They have been known as traditional tonic foods and folk medicinal sources for a long time in Asian countries including Korea, China, and other countries [8]. They also have diverse nutritional components such as a variety of vitamins and minerals [7], and moreover they hold a number of biological active chemicals involving fatty acids for wound healing [9], and phenols and flavonoids for anti-oxidation [10] and fucosylated chondroitin with anticoagulant and antithrombotic activities [11].

Recent our study showed polysaccharides extracted from sea cucumber, Stichopus japonicas and their structure and biological activities in cellular levels using RAW 264. 7 macrophage cells as well [8]. However, their immune-enhancing activity was not shown in vivo immunosuppressive mice system. Therefore, the current study evaluated the effect of oral administration of the isolated polysaccharide from S. japonicas on immunosuppressive mice using cyclophosphamide (CY) in addition to immune-signaling pathway.

Materials and methods

Animals

Inbred strain male (6 weeks old) BALB/c mice, weighing 21–24 g, were purchased from Central Lab. Animals Inc. (South Korea). These animals were specific pathogen free, kept in environmentally controlled quarters with temperature maintaining at 22 ± 2 °C and a 12-h dark–light cycle for at least a week before starting the experiment, and fed on standard laboratory diet and water. All experimental procedures were approved by Gangneung-Wonju National University committee for animal experiments (Approval number: GWNU-2016-31).

Isolation of crude polysaccharide

The polysaccharide of S. japonicus (SJP) was isolated as the method of Cao et al. [12]. After 20 g milled sample of S. japonicus was suspended in 200 ml 99% ethanol (EtOH) at 70 °C for 2 h, the residue was dissolved in distilled water extracted twice at 80 °C for 2 h. The extract solution was concentrated and EtOH was added to precipitate the polysaccharide. The polysaccharide was collected by filtration and washed with organic solvents such as EtOH and acetone, then dried at room temperature. The dried polysaccharide was re-dissolved in distilled water, and the deproteinization was carried out using the method reported by Sevag et al. [13] to obtain the crude SJP.

Development of immunosuppression in vivo mice

Mice were randomly divided into six groups after being adapted to environment for 1 week (n = 5). One group of mice was used as normal control (normal group) which was orally administrated with normal saline. The other groups were orally administrated normal saline (saline group) or various concentration of SJP (125, 250, 500 and 750 mg/kg BW). All groups were received the treatment once daily for 10 consecutive days. At day 4–6 of administration, mice (except normal group) were intraperitoneally injected once a day with 80 mg/kg body weight (BW) of Cyclophosphamide (Sigma). After 24 h of last administration, mice were sacrificed.

Preparation of splenocytes and peritoneal macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages were collected using Ray and Dittel’s method [14]. Briefly, after 5 ml of ice cold PBS (with 3% FCS) was injected into the peritoneal cavity, it was collected using syringe. After spinning the collected cell suspension, the supernatant was discarded and the cells in desired media or PBS were re-suspend for counting.

Splenocytes were obtained by gentle disruption of the spleen of BALB/c mice after weighed and filtration through sieve mesh. The spleen index was calculated by the following formula: spleen index = spleen weight (mg)/body weight (g). After the lysis of spleen tissues with 1X RBC Lysis Buffer (eBioscience, USA), the remaining cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 100 IU/ml penicillin, followed by centrifugation and washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

Peritoneal macrophage proliferation and nitric oxide production

EZ-Cytox Cell Viability Assay Kit (Daeil Labservice, Korea) was used to determine the proliferation of the collected peritoneal macrophage cells as described by Kim et al. [15]. The macrophage proliferation ratio (%) was calculated based on the following formula.

The immunomodulatory activity was determined by the basis of nitric oxide (NO) production in the macrophage culture supernatant. The cells were cultured with or without of LPS. The nitric concentration was evaluated using the Griess reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) [16].

Phagocytosis of peritoneal macrophages

Phagocytosis of peritoneal macrophages was measured by neutral red uptake method as previously reported [17, 18]. Cells were placed into the 96-well round-bottom microplates in triplicate at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/well and then cultured overnight in complete RPMI-1640 medium at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Serum free RPMI-1640 medium was used as control. At the following day, all non-adherent cells were removed by washing with PBS, then 6 g/well LPS was added to the wells. After 24 h culture, the cells were washed with PBS twice and then 200 l neutral red solution (0.09% mass fraction of solute) was added into each well. The microplates were incubated for 30 min and then cells were washed to remove excess dye. To measure the activity of phagocytosis, the absorbance was measured at 540 nm via the microplate reader. The absorbance (A) was translated into phagocytosis ratio for comparison: phagocytosis ratio (%) = A test/A normal × 100%.

Splenic lymphocyte proliferations

The collected splenocytes were induced with T cell mitogen Con A (5 µg/ml), B cell mitogen LPS (10 µg/ml) or RPMI at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cell proliferation was measured by EZ-Cytox Cell Viability Assay Kit after 48 h culture.

Cytotoxicity assays of natural killer cell activity of splenocytes

In order to evaluated natural killer cell activity of splenocytes, the collected splenocytes were incubated with YAC-1 cells [19] and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) solution (Promega Co., USA) was used [20, 21]. The percentage of NK cellular cytotoxicity was calculated using the following formula: cytotoxicity (%) = [(experimental release-spontaneous release)/(maximum release-spontaneous release)] × 100.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription

Total RNA was isolated from mitogens-stimulated (Con A and LPS) splenic lymphocyte cells using Tri reagent® (molecular research center, Inc., USA). The RNA was precipitated using 100% of isopropanol and washed with 75% ethanol. The RNA pellet was dissolved in nuclease-free water and the extracted RNA concentration was measured using the nanophotometer (Implen, Germany). The cDNA was prepared using the High capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied biosystems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of immune associated gene expression by semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Immune gene expression of mitogens-stimulated splenic lymphocyte cells was examined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR with specific primers. The reaction was performed in a total reaction volume of 20 µl/well of PCR Premix (Bioneer Accupower). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Western blot assay for in vitro study

RAW264.7 macrophage cells were cultured with different concentration of SJP (3.75, 7.5, 15 and 30 µg/ml) or 1 µg/ml of LPS. After the lysis of the RAW264.7 cells, the total proteins from the cells were harvested with RIPA buffer (Tech & Innovation, China). The protein concentration was measured using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). After SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), western blot assay was carried out as Narayanan et al. [22] using polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were incubated with antibodies specific for p-NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology), p-IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology), p-p38 (Cell Signaling Technology), p-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology), p-JNK (Cell Signaling Technology) and α-Tubulin (Abcam). Protein signals were detected using the Pierce® ECL Plus Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific, USA). The blot was imaged and quantitated using the ChemiDoc XRS + imaging system (Bio-Rad) and ImageLab software (version 4.1, Bio-Rad).

Effect of NF-κB and MAPK activation inhibitors on TNF-α expression

RAW264.7 macrophage cells were treated with 100 nM of NF-κB activation inhibitor (Merck, 481406), and 20 µM of ERK activation inhibitors (Merck, 328006), JNK (Merck, 420119), and p38 (Merck, 559389) [23]. The cells were stimulated with a variety of SJP (3.75, 7.5, 15 and 30 µg/ml) or 1 µg/ml of LPS and total RNA was isolated from the cells in order to analyze the expression of TNF-α. The expression was quantified using the QuantStudio™ 7 FlexReal-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher scientific, USA) with SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio Inc., Japan). The results of quantification were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [24] comparison to β-Actin as the reference mRNA.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with ‘Statistix 8.1’ Statistics Software. The results were compared using One-way ANOVA followed by compared with controls and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01.

Results and discussion

Effect of SJP on peritoneal macrophage proliferation and nitric oxide production

Macrophages are extraordinarily versatile cells, playing a central role in a host’s defense against bacterial infection by nature of their phagocytic, cytotoxic, and intracellular killing capacities [25]. NO plays a crucial role in antibacterial and antitumor defense system of innate immune cells. In addition, phagocytosis is a major mechanism used to remove pathogens [26] and cell debris [27] in the immune system.

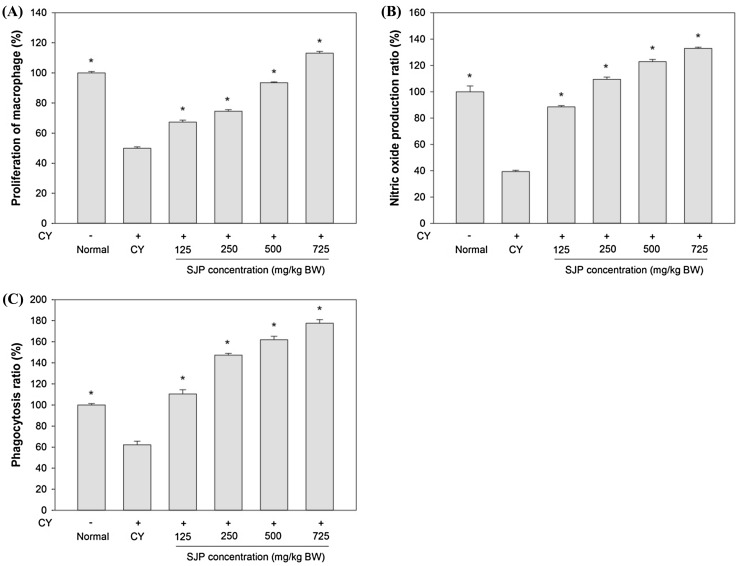

To investigate the effect of SJP, peritoneal macrophages were obtained from each group of mice and were stimulated with LPS. As shown in Fig. 1(A) and (B), SJP significantly enhanced peritoneal macrophage proliferation and nitric oxide production in a dose-dependent compared to the only CY-treated mice (CY). At the doses of 500 and 750 mg/kg BW, SJP restored peritoneal macrophage proliferation to the same or higher level than the non-treated mice (Normal). In addition, SJP at the dose of 250, 500 and 750 mg/kg BW enhanced nitric oxide production compared to the non-treated mice (Normal). Our results showed that CY treatment decreased peritoneal macrophage proliferation and NO production compared to normal mice. However, SJP treatment enhanced dose dependent of peritoneal macrophage proliferation and NO production in immunosuppressed mice.

Fig. 1.

The effect of various concentration of SJP. (A) The effect on peritoneal macrophage proliferation, (B) the effect on nitric oxide production, (C) the effect on phagocytosis activity. Significant different at P < 0.01 compared with saline group (*)

Effect of SJP on peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis

Phagocytosis is also crucial for both adaptive and innate immunity such as defense against pathogens, tissue repair promoting, and chronic inflammation [28]. Phagocytosis ratio of peritoneal macrophages from normal mice was regarded as 100% by neutral red uptake method. As shown in Fig. 1(C), peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis was significantly reduced in CY group compared to normal group. After SJP treatment, peritoneal macrophage phagocytosis rates were markedly increased compared with CY group in a dose-dependent manner. The treatment with the SJP also promoted recovery of phagocytosis ratio of peritoneal macrophage similar to or more than normal group. Our results showed that SJP could enhance the immune function in CY-treated mice.

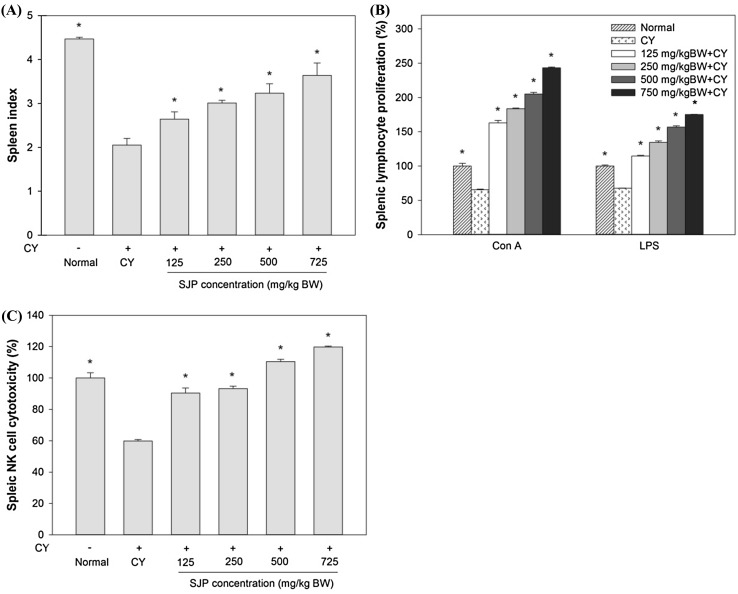

Effect of SJP on spleen index

Spleen is an important lymphoid organ in immunity, housing different populations of monocytes and macrophages, with B and T lymphocytes for both innate and adaptive immune responses [29]. The status of spleen indicates the immune function of the organism and spleen associated factors including spleen index was shown in this study [30]. The numbers of spleen index in CY-treated mice (CY) receiving various concentration of SJP were examined on the day of sacrifice and the results were shown as Fig. 2(A). CY treatment considerably reduced the number of spleen index compared with normal group. After SJP treatment, there was significant difference and increase in the number of spleen index compared with saline group without raised the body weight (data not shown) in a dose-dependent, suggesting the protective effect of SJP against the immunosuppressive effect.

Fig. 2.

The effect of various concentration of SJP. (A) The effect on spleen index, (B) the effect on splenic lymphocyte proliferation, (C) the effect on splenic NK cell cytotoxicity activity. Significant different at P < 0.01 compared with saline group (*)

Effect of SJP on splenic lymphocyte proliferations

The proliferation of spleen lymphocyte (T/B lymphocytes) as a response to the stimulation induced by antigens or mitogens is a typical non-specific immune reaction with a well-understood mechanism [31]. T lymphocytes and its secreted lymphokines are associated with the adaptive or cell mediated immune responses. B lymphocytes and antibodies secreting plasma cells are the key elements involved in humoral immune responses. Splenocytes from each group were co-treated with two kinds of mitogen (Con A and LPS). Normally, T lymphocyte immunity is detected through Con A-stimulated cellular proliferation, while B lymphocyte immunity is detected through LPS-induced cellular proliferation. The normal splenic lymphocyte proliferation ratio induced by Con A or LPS was regarded as 100%. As shown in Fig. 2(B), the proliferative responses of splenic lymphocytes to both T cell and B cell mitogens (Con A and LPS, respectively) were reduced remarkably in CY-treated mice, when compared to the normal splenic lymphocyte proliferation ratio. Treatment of SJP enhanced dose-dependently both T cell and B cell proliferation compared with saline group and also significantly higher than normal group. From the results, both of Con A- and LPS-induced cellular proliferations were decreased in CY-treated group, when compared to the normal group. The SJP treatment enhanced Con A- and LPS-stimulated lymphocytes in a dose-dependent compared with the model group. These results indicated that SJP could improve the immune response of the splenic lymphocytes in CY-induced immunosuppressed mice.

Effect of SJP on cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cell activity of splenocytes

Natural Killer (NK) cells have been regarded as short-live cytolytic cells to rapidly react against pathogens and tumors with antigen-independent manner in order to cause to cell death. Recent works have showed that NK cells are associated with adaptive immunity, similar to T and B cells [32]. NK cell activity of splenocyte was determined by examining cytotoxicity against YAC-1 cells using an LDH assay. As shown in Fig. 2(C), CY seriously inhibited splenic NK cell activity in CY-treated mice, compared with normal mice. Treatment with various dosage of SJP enhanced dose-dependently NK cell activity of splenocytes compared with CY group. Especially the activity of splenic NK cell recovered to the normal or higher level with treatment at the dose of 500 and 750 mg/kg BW SJP. In this study, splenic NK cells cytotoxicity of the Cy-treated group was significantly decreased compared with the normal mice. Even treatment with low dosage of SJP (125–250 mg/kg BW) restored the splenic NK cells cytotoxicity as much as the normal group and also enhanced the cytotoxic activity when treated with high dosage of SJP (500–750 mg/kg BW). These results suggest that SJP contain high potentiality to improve the cell immune function in immunosuppressed mice.

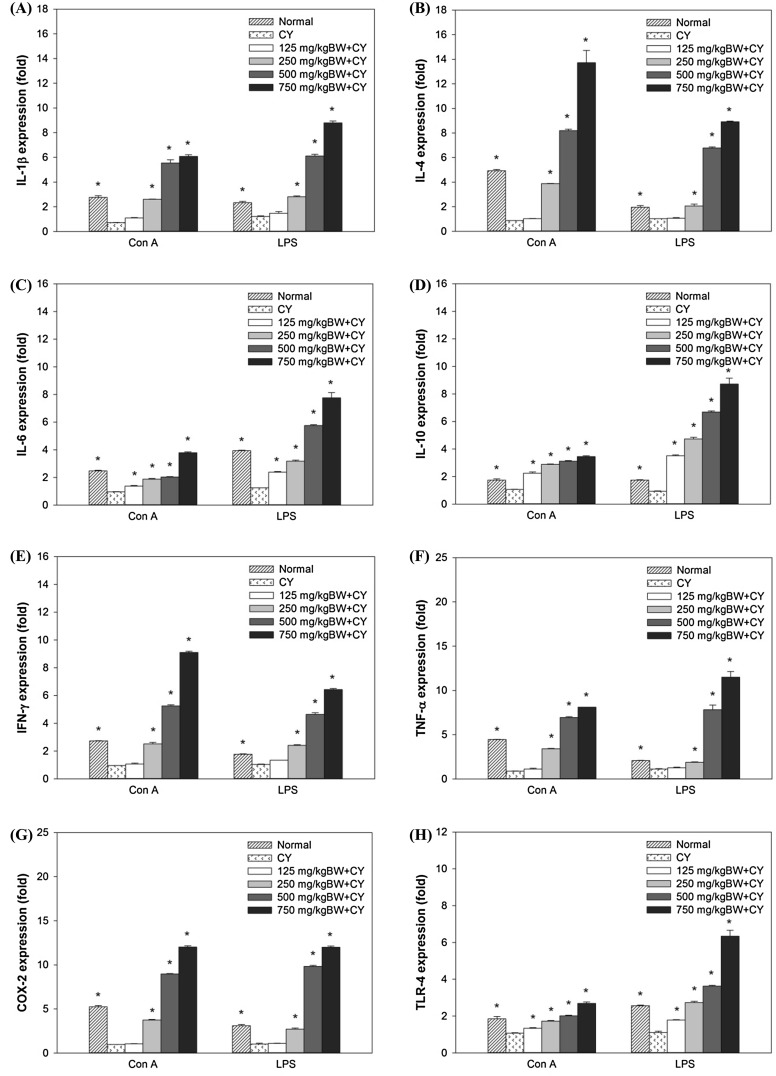

Effect of SJP on splenic lymphocyte immune associated gene expression

Cytokines, key regulators of inflammation are associated with acute and chronic inflammation through controlling intracellular signaling [33]. COX has been known as a critical enzyme to catalyze and regulate the production of prostaglands such as PGE2 in immune systems [34] and TLR4 is reported to be associated with T cell inflammation induced by LPS [35]. The different cytokine patterns secreted by Th1 and Th2 cells with different functions are major determinants of the differences in cellular function and the subsets of Th cells depend upon the specific types of cytokines in which Th1 cells characterized by IFN-γ and TNF-α in contrast to Th2 cells characterized by IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 [36]. To elucidate the immunomodulation effect of SJP, cytokines expression in splenocytes was determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3, the splenic lymphocyte cytokine expression in CY group was decreased compared with normal group. In contrast, treatment with various dosage of SJP enhanced splenic lymphocyte cytokine expression responses to both T cell and B cell mitogens. Most of splenic lymphocyte cytokines and immune associated genes (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, TLR-4 and COX-2) respond to B cell mitogen (LPS) more than T cell mitogen (Con A). However, IFN-γ and IL-4 was more expressed when stimulated with Con A than LPS. As shown in the results, Th1 and Th2 cytokines expression in CY-treated mice were significantly decreased compared to the normal mice, however, treatment with SJP increased cytokine expression in CY-treated mice. This indicated that SJP could promote the secretion of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in order to restore immunosuppression.

Fig. 3.

Quantification of immune associated genes in relative expression (fold) from mitogens-stimulated splenic lymphocyte cells. (A) Relative expression of IL-1β, (B) relative expression of IL-4, (C) relative expression of IL-6, (D) relative expression of IL-10, (E) relative expression of IFN-γ, (F) relative expression of TNF-α, (G) relative expression of COX-2, (H) relative expression of TLR-4. Significant different at P < 0.05 compared with saline group (*)

Effect of SJP on NF-κB and MAPK pathway signaling

To regulate the immune responses, NF-κB cooperates with pro-inflammatory mediators such as iNOS, COX-2 and proinflammatory cytokines [37]. Moreover, MAPK, including ERK1/2, JNK and p38, also modulates cell growth and differentiation with cellular responses to cytokines and stresses [38], and MAPK pathways has been considered to be harmonized with NF-κB to regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory process [39]. Further investigation was performed to elucidate how the SJP induced the immune responses in the peritoneal macrophage and splenic lymphocytes. The RAW 264.7 cells were co-cultured with various concentration of SJP. As shown in Fig. 4, treatment with various concentration of SJP induced phosphorylation of IκBα, degradation form of IκBα, higher than normal group (RPMI). The nuclear translocation of p65 (p-NF-κB-p65) was increased in a dose-dependent manner of SJP. In order to investigate the effect of SJP on MAPK signaling, the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK and p38 were also evaluated. The phosphorylation of ERK, JNK and p38 were highly enhanced when co-cultured with SJP compared to RPMI. Our results indicated that SJP stimulated macrophages via NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways.

Fig. 4.

The effect of SJP on the proteins associated with NF-κB and MAPK pathways in RAW264.7 cells. (A) Protein signaling from western blot, (B) relative band intensity

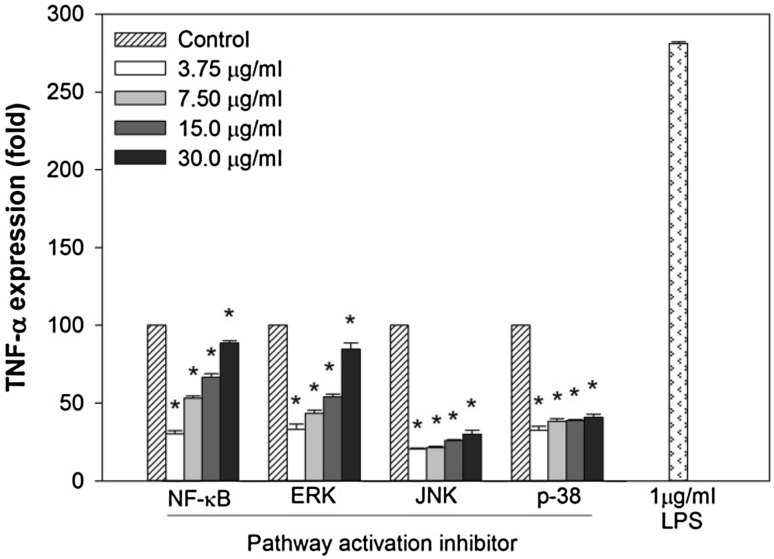

Effect of SJP on NF-κB and MAPK activation inhibited-RAW 264.7 cells

To further elucidate the effect of SJP on the mechanism of the immune-regulatory activity, TNF-α expression level was measured from NF-κB and MAPK activation inhibited-RAW 264.7 cells. Treatment with SJP enhanced the TNF-α expression level in a dose-dependent from NF-κB and MAPK activation inhibited-RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 5). Especially, the dosage of 30 µg/ml SJP restored TNF-α expression in NF-κB and ERK inhibited-RAW 264.7 cells. These results indicated that SJP enhanced the immune functions of CY-treated mice though activating NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathway.

Fig. 5.

The effect of SJP on quantification of TNF-α in relative expression (fold) from NF-κB and MAPK activation inhibited-RAW264.7 cells. Significant different at P < 0.05 compared with Control (*)

In conclusions, the present study demonstrated that polysaccharide from Sea cucumber, Stichopus japonicas (SJP) can restore the immunosuppression in CY-treated mice through in vivo peritoneal macrophage NO production, peritoneal macrophage and splenic lymphocyte proliferations, phagocytosis ratio, spleen index, splenic NK cells activity and splenic lymphocyte cytokine expression in CY-induced immunosuppressive mice. Therefore, SJP may have huge potentiality to apply as an efficacious functional materials and/or as medicine in order to enhance human immunity.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Marine Bio-Regional Specialization Leading Technology Development Program (D11413914H480000100) funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries in Korea.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Walls J, Sinclair L, Finlay D. Nutrient sensing, signal transduction and immune responses. Semin Immunol. 2016;28:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miccadei S, Masella R, Mileo AM, Gessani S. Omega3 polyunsaturated fatty acids as immunomodulators in colorectal cancer: New potential role in adjuvant therapies. Front Immunol. 2016;7:486. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jesenak M, Urbancikova I, Banovcin P. Respiratory tract infections and the role of biologically active polysaccharides in their management and prevention. Nutrients. 2017;9:779–790. doi: 10.3390/nu9070779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Lin Q, Yan Y, Peng F, Sung R, Ren J. Hemicellulose from plant biomass in medical and pharmaceutical application: A critical review. Curr Med Chem. (2017). 10.2174/0929867324666170705113657 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Patel S, Goyal A. Chitin and chitinase: Role in pathogenicity, allergenicity and health. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;97:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daien CI, Pinget GV, Tan JK, Macia L. Detrimental impact of microbiota-accessible carbohydrate-deprived diet on gut and immune homeostasis: An overview. Front Immunol. 2017;8:548. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bordbar S, Anwar F, Saari N. High-value components and bioactives from sea cucumbers for functional foods—a review. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:1761–1805. doi: 10.3390/md9101761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao RA, Surayot U, You S. Structural characterization of immunostimulating protein-sulfated fucan complex extracted from the body wall of a sea cucumber, Stichopus japonicus. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;99:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredalina BD, Ridzwan BH, Abidin AA, Kaswandi MA, Zaiton H, Zali I, Kittakoop P, Jais AM. Fatty acid compositions in local sea cucumber, Stichopus chloronotus, for wound healing. Gen Pharmacol. 1999;33:337–340. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(98)00253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Sun Z, Zhang M, Meng X, Xia X, Yuan W, Xue F, Liu C. Antioxidant and antihyperlipidemic activities of polysaccharides from sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;90:1664–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ustyuzhanina NE, Bilan MI, Dmitrenok AS, Shashkov AS, Kusaykin MI, Stonik VA, Nifantiev NE, Usov AI. Structure and biological activity of a fucosylated chondroitin sulfate from the sea cucumber Cucumaria japonica. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;26:449–459. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwv119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao RA, Lee SH, You SG. Structural effects of sulfated-glycoproteins from Stichopus japonicus on the nitric oxide secretion ability of RAW 264.7 cells. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2014;19:307–313. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2014.19.4.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sevag MG, Lackman DB, Smolens J. The isolation of the components of streptococcal nucleoproteins in serologically active form. J Biol Chem. 1938;124:425–436. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray A, Dittel BN. Isolation of mouse peritoneal cavity cells. J Vis Exp. 2010;35:1488. doi: 10.3791/1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JK, Cho ML, Karnjanapratum S, Shin IS, You SG. In vitro and in vivo immunomodulatory activity of sulfated polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;49:1051–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15 N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Tong X, Li P, Cao H, Su W. Immuno-enhancement effects of Shenqi Fuzheng Injection on cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression in Balb/c mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weeks BA, Keisler AS, Myrvik QN, Warinner JE. Differential uptake of neutral red by macrophages from three species of estuarine fish. Dev Comp Immunol. 1987;11:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0145-305X(87)90013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho CW, Han CJ, Rhee YK, Lee YC, Shin KS, Shin JS, Lee KT, Hong HD. Cheonggukjang polysaccharides enhance immune activities and prevent cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park HR, Lee HS, Cho SY, Kim YS, Shin KS. Anti-metastatic effect of polysaccharide isolated from Colocasia esculenta is exerted through immunostimulation. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:361–368. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarangi I, Ghosh D, Bhutia SK, Mallick SK, Maiti TK. Anti-tumor and immunomodulating effects of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelia-derived proteoglycans. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1287–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narayanan BA, Narayanan NK, Simi B, Reddy BS. Modulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and related proinflammatory genes by the omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:972–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharyya S, Ratajczak CK, Vogt SK, Kelley C, Colonna M, Schreiber RD, Muglia LJ. TAK1 targeting by glucocorticoids determines JNK and IkappaB regulation in Toll-like receptor-stimulated macrophages. Blood. 2010;115:1921–1931. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-224782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun KJ, Kim JY, Kim JB, Lee KW, Jeong SY, Park HJ, Jung HJ, Cho YW, Yun K, Lee KT. Inhibition of LPS-induced NO and PGE2 production by asiatic acid via NF-kappa B inactivation in RAW 264.7 macrophages: possible involvement of the IKK and MAPK pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Underhill DM, Ozinsky A, Hajjar AM, Stevens A, Wilson CB, Bassetti M, Aderem A. The Toll-like receptor 2 is recruited to macrophage phagosomes and discriminates between pathogens. Nature. 1999;401:811–815. doi: 10.1038/44605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartl MM, Luckenbach T, Bergner O, Ullrich O, Koch-Brandt C. Multiple receptors mediate apoJ-dependent clearance of cellular debris into nonprofessional phagocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2001;271:130–141. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navegantes KC, de Souza Gomes R, Pereira PAT, Czaikoski PG, Azevedo CHM, Monteiro MC. Immune modulation of some autoimmune diseases: the critical role of macrophages and neutrophils in the innate and adaptive immunity. J Transl Med. 2017;15:36. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1141-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lori A, Perrotta M, Lembo G, Carnevale D. The spleen: A hub connecting nervous and immune systems in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1216–1227. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Nie W, Fan S, Zhang J, Wang Y, Lu J, Jin L. A polysaccharide from Sargassum fusiforme protects against immunosuppression in cyclophosphamide-treated mice. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;90:1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinkora M, Butler JE. Progress in the use of swine in developmental immunology of B and T lymphocytes. Dev Comp Immunolo. 2016;58:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Sullivan TE, Sun JC, Lanier LL. Natural Killer Cell Memory. Immunity. 2015;43:634–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner MD, Nedjai B, Hurst T, Pennington DJ. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:2563–2582. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karavitis J, Hix LM, Shi YH, Schultz RF, Khazaie K, Zhang M. Regulation of COX2 expression in mouse mammary tumor cells controls bone metastasis and PGE2-induction of regulatory T cell migration. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds JM, Martinez GJ, Chung Y, Dong C. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in T cells promotes autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13064–13069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120585109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raphael I, Nalawade S, Eagar TN, Forsthuber TG. T cell subsets and their signature cytokines in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine. 2015;74:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-kappaB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:7–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JB, Han AR, Park EY, Kim JY, Cho W, Lee J, Seo EK, Lee KT. Inhibition of LPS-induced iNOS, COX-2 and cytokines expression by poncirin through the NF-kappaB inactivation in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:2345–2351. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cargnello M, Roux PP. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 75: 50–83 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]