Abstract

Actinopyga lecanora, as a rich protein source was hydrolysed to generate antibacterial bioactive peptides using different proteolytic enzymes. Bromelain hydrolysate, after 1 h hydrolysis, exhibited the highestantibacterial activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas sp., Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Two dimensional fractionation strategies, using a semi-preparative RP-HPLC and an isoelectric-focusing electrophoresis, were applied for peptide profiling. Furthermore, UPLC-QTOF-MS was used for peptides identification; 12 peptide sequences were successfully identified. The antibacterial activity of purified peptides from A. lecanora on P. aeruginosa, Pseudomonas sp., E. coli and S. aureus was investigated. These identified peptides exhibited growth inhibition against P. aeruginosa, Pseudomonas sp., E. coli and S. aureus with values ranging from 18.80 to 75.30%. These results revealed that the A. lecanora would be used as an economical protein source for the production of high value antibacterial bioactive peptides.

Keywords: Actinopyga lecanora, Bioactive peptides, Antibacterial activity, Hydrolysate, Proteolytic enzyme

Introduction

Bioactive peptides are considered as specific protein fragments that are inactive within the sequence of the parent protein while may exert various physiological functions after releasing via hydrolysis [1]. Apart from nutritional values, they have the potential to provide numerous functional properties based on their structural that is reflected by the types of amino acids involved in the chain. They have shown a number of multiple biological activities, including anti-thrombotic, anti-hypertensive, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial function and anti-cancer activities [2]. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have the ability to kill a wide range of microorganisms [3]. They mainly participate in the innate immune system and are used as a first line of immune defense [4] in higher organisms such as plants, insects, and mammals [5]. Recently, the demands for Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) generated from edible protein sources has become more important since they are effective, non-toxic and they are unaffected by antibiotic-resistance mechanisms and limitation on the use of synthetic preservatives in food systems [6].

Actinopyga lecanora commonly known as stone fish is classified among edible species of sea cucumber and harvested for the food trade [7]. It is belonging to the marine invertebrates under the class of Holothuroidea and family of Holothuriidae, and considered by-catch from fishing industry in Malaysia. A lecanora would be a potential commercial source of raw material for bioactive peptides generation due to its relatively high protein and low price. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to generate natural protein hydrolysates from A. lecanora, and identify its bioactive peptides with antibacterial properties.

Materials and methods

Materials

Fresh sample of Actinopyga lecanora was purchased from Pantai Merdeka in the Kedah state, Malaysia, and transported, on ice to the laboratory. Upon arrival, the internal organs were removed and samples were rinsed with cold distilled water, packed and stored in a freezer at − 80 °C until further use. Alkalase®2.4 L from Bacillus licheniformis and flavourzyme® were obtained from Novoenzyme (Bagsvaerd, Denmark). Bromelain, papain, glutathione and ferrozine were obtained from Acros Organics Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Pepsin from porcine gastric mucosa was supplied by Merck Co (Darmstadt, Germany), and trypsin from beef pancreas was supplied by Fisher Scientific (Georgia, USA). O-phtaldialdehyde (OPA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany).

Preparation of enzymatic hydrolysates from A. lecanora

Prior to enzymatic hydrolysis, the freeze-dried A. lecanora was ground into a powder using a Warring blender and passed through a #35 mesh sieve to obtain milled whole A. lecanora. The sample (10 g) was mixed with 50 mL distilled water and dialyzed in 12–14 kDa molecular weight cut off dialysis tube according to the manufacture’s guide. After dialysis, the sample was hydrolyzed independently with each of the enzymes namely papain, bromelain, pepsin, trypsin, flavourzyme, alcalase at a ratio of 1:100 (enzyme/substrate w/w), according the method describe by Ghanbari et al. [7].

Peptide content measurement

Peptide content was measured using the O-phthaldialdehyde method (OPA) [8] with some modifications. Sample (36 µL) and OPA solution (270 µL) were pipetted into individual wells of 96-well plate. The mixture was incubated for 2 min at room temperature and the absorbance was measured at 340 nm. The peptide content was measured based on glutathione calibration curve constructed in the range of 0.01–0.25 mg/mL. The test was carried out in triplicate and peptide content was expressed as mg/mL hydrolysate.

Antibacterial activity

All bacterial strains used in this study were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Antibacterial activities of samples were examined against both gram–negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 10145), Pseudomonas sp. Escherichia coli (ATCC 10536) as well as gram-positive [Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) and Basillus subtilus (ATCC 11774)] pathogens. For antibacterial activities, samples were evaluated following the method described by Liu et al. [9] and Tang et al. [10] with some modifications. In this regard, samples were prepared by mixing the bacterial inoculum (10 μL) containing 106 cfu/mL with TSB medium (90 μL) and sterile hydrolysate at 1.0 mg/mL, purification fractions of 0.1 mg/mL and identified peptides (90 μL), in sterile 96-well plate. The wells containing medium, bacterial culture and 50 mM of an appropriate buffer for each hydrolysate were used as a negative control. Chloramphenicol at a concentration of 50 µg/mL and gentomtcine (10 µg/mL) were used as positive controls. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight with shaking at 50 rpm. The bacteria growth was monitored by measuring the absorbance of wells at 630 nm using the 96-well plate reader (Power Wave, X340, BioTek Instruments, INC). This experiment was carried out in triplicate for each sample with each microorganism. The percentage inhibition was calculated using the following equation:

where OD represent the absorbance of the control and sample, respectively.

Profiling of A. lecanora bromelain hydrolysate

Fractionation using reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography

The A. lecanorahydrolysate generated by bromelain was fractionated using a semi-preparative RP-HPLC system (Agilent Technologies 1200 series, USA), coupled with a photodiode array detector and an automatic fraction collector. The separation was done on a Zorbax 300 SB-C18 column (250 mm, 9.4 mm and 5 μm particle size; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) with a flow rate of 4 mL/min using a gradient elution of two mobile phases. Peptides were detected at 205 nm. The mobile phase A comprised of deionised water containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and mobile phase B consists of acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. Gradient elution was applied according to the following program: 0–5 min, 100% eluent A; 5–60 min, 0–100% eluent B. Forty-five fractions were collected and freeze-dried for 24 h to determine their antibacterial activity after resolving in deionized water. The fractions with high antibacterial activities, obtained by RP-HPLC, were further fractionated using isoelectric focusing technique.

Isoelectric focusing fractionation

The most effective fractions from RP-HPLC were subjected to the isoelectric focusing (IEF) electrophoresis for separation of the peptides based on their isoelectric point (pI). The 3100 OFFGEL fractionator and the OFFGEL Kit 3–10 (both from Agilent Technologies Waldbronn, Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany) were used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The device was set up for the separation of samples by applying a 13 cm long immobilized pH gradient (IPG) gel strips with a linear pH gradient ranging from 3 to 10. IPG strip re-hydration solution (40 µL) was added into each well, incubated for 15 min without voltage to re-swell the gel, and sealed tightly against the well frame. Then 150 µL of diluted sample was distributed equally into each well. A high voltage ranging from 500 to 4000 V was applied throughout separation. Typical focusing times are 24 h. Upon completion, the substance of each well was collected from the liquid phase and transferred into individual micro-tubes. The anti-bacterial activity of each fraction was assayed as mentioned in “Antibacterial activity” section.

Peptide sequencing using tandem mass spectrometry

Potent fractions from isoelectric separation were freeze-dried and reconstituted in 25 µL of 5% acetonitrile (HPLC Grade, Fisher Scientific) in Milli-Q water containing 0.1% formic acid. The tubes were vortexed and finally spun at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was analysed using an ultra-high performance liquid chromatography system (1290 UHPLC, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) coupled to a high-resolution, accurate mass hybrid quadrupole-time of flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometer (6540 Q-TOF, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). Briefly, 1 µL of each peptide sample was injected and separated using gradient elution of acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid from 5 to 65% over 15 min. Peptides were monitored in MS-mode between 100 and 3200 m/z and automatically selected for collisionally induced dissociation (CID, MS/MS) based on a preference of charge state: 2 > 1 > 3.

Peptides identification

Raw data files acquired using the Q-TOF mass spectrometer were searched against the plant species sub-directory of the SwissProt protein database (UniProt, EBI, UK). Basic parameter settings included a precursor mass tolerance of 10 ppm, a product mass tolerance of 50 ppm and a ‘no-enzyme’ constraint. Peptides were considered a match if they had a score greater than 6 and a % scored peak intensity > 50.

Peptide synthesis

The peptides identified from A. lecanora were synthesized with a simultaneous multiple peptide synthesizer (PSSM-8; Shimadzu) using the fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry which is described by Nokihara et al. [11]. The synthesized peptides were purified using HPLC on an ODS column (PEGASIL-300, 20 mm × 250 mm; Senshu Scientific Co.) with a linear gradient from 0 to 50% ACN containing 0.1% TFA in 100 min (flow rate, 5.0 mL/min; monitoring at 220 nm). The molecular masses of the isolated peptides were determined by mass spectrometry.

Hemolytic assay

The hemolytic activity of identified antibacterial peptides was determined using human erythrocytes as explained by Nakajima et al. [12]. Erythrocytes were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The erythrocytes were resuspended at 2% in PBS. The cell suspensions (50 µL) were mixed with equal volumes of various concentrations of the peptides ranging from 50 to 4000 µM and topped up to 1000 µL with PBS. After incubation at 37 °C for 2 h samples were centrifuged at 2000×g for 5 min and supernatant absorbance was determined at 420 nm. The absorbance obtained after treating erythrocytes with only PBS and PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 supplied as blank and maximum lysis (100% hemolysis), respectively. The percentage of haemolysis was calculated as follows:

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were subjected to one-way analysis of variance. Tukey’s test was performed to determine the significant differences at the 5% probability level.

Results and discussion

Generation and purification of antibacterial peptides

Actinopyga lecanora was hydrolyzed using six different proteases namely alcalase, papain, bromelain, pepsin, trypsin and flavourzyme and samples were withdrawn every 1 h of hydrolysis up to 24 h and assayed for antibacterial activities. The antibacterial activities of different hydrolysates against E. coli, B. subtilis, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and Pseudomonas sp. were studied. Bromelain-generated hydrolysate after 1 h of hydrolysis was the most effective hydrolysate on both Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. The maximum growth inhibition against Pseudomonas sp., P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and E. coli were 51.85, 30.07, 24.30 and 30.00%, respectively, while the unhydrolyzed A. lecanora exhibited no antibacterial effect [7]. This phenomenon agreed with the finding of Osman et al. [13] which reported that unhydrolyszed goat whey has no antibacterial activity compared to GWH.

Profiling of bromelain-generated hydrolysate

Fractionation based on hydrophobicity using RP-HPPLC

Bromelain-generated hydrolysate was further fractionated on the basis of peptides hydrophobicity using semi preparative RP-HPLC. Out of 45fractions collected, fractions 20, 21, 22 and 23 showed the highest antibacterial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, Pseudomonas sp. and P. aerogenios by 24.00, 20.00, 24.50 and 15.00%, respectively.

Fractionation based on isoelectric properties using OFFGEL fractionator

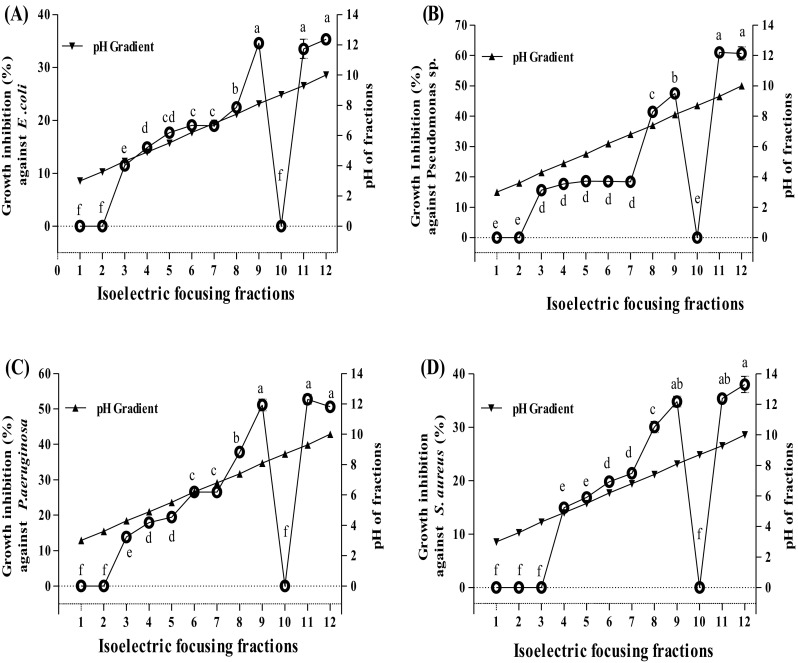

In the second step, the fractionation of peptides was performed based on their isoelectric points (pIs) using an isoelectric focusing (IEF) system (OFFGEL fractionators; 3100 Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany). The IEF is a high-resolution electrophoresis technique used to separate and concentrate of protein or peptidemolecules at their isoelectric point (pI) through the use of 12-wells device in a pH gradient range of 3 to 10 under the application of an electric field [14]. Due to the absence of anyfluidic connection between the wells, the proteins or peptides are forced to migrate through the IPG gel where the actual separation takes place. As the peptides approach to their pI, they progressively lose their charge, and will begin to concentrate at the position where their pH is equal to their pI. Four HPLC fractions with high antibacterial activity are mixed and subjected to IEF, and all 12 sub-fractions were individually collected and evaluated for their antibacterial activities at the same peptide concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. The results from anti-bacterial activities were plotted against fraction numbers and the pH gradient (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Growth inhibition activities (%) of the isoelctric focusing fractions from RP-HPLC fractions of A. lecanora bromelain-generated hydrolysate against; (A) E. coli, (B) Pseudomonas sp., (C) P. aeruginosa, and (D) S. aureus. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three replications. Mean with different letters (a–f) above the line represents significantly different at p < 0.05

As shown in Fig. 1, the growth of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria was progressively inhibited by increasing the isoelectric points of peptides. The only exception was fraction 10, which was free of peptides. In general, the antibacterial activities of peptides influence by their net charges, and it increase with increasing positive charge. At the first step of antibacterial action, the peptides must interact with highly negatively charged components of the outer bacterial membrane and displace magnesium ions to partly neutralize this charge [15]. Thus, the extent of positive charge is a crucial factor in antibacterial activities of peptides. In this regards, Dathe et al. (2001) [16], reported that peptides with high positive charges destroyed the integrity of the outer bacterial wall.

The higher activities of fractions 11 (pH 9.4) and 12 (pH 10.0) compared to other fraction may relate to their greater number of positive charges. The highest growth inhibition (35.34%) against E. coli was obtained when fraction 12 (pH 10) was applied, which was followed by fractions 11 (pH 9.4) and 9 (pH 8.2) with values of 33.50 and 34.62%, respectively.

Clearly, as shown in Fig. 1, the growth inhibition (%) against pseudomonas sp. and P. aeruginosa in all fractions followed in a similar manner to E. coli. Peptides with a pI from acidic and neutral ranged from 3 to 7.0 (fraction 1–7) gave the lowest inhibition activities among other fractions. The growth ofPseudomonas sp. was inhibited by a value of 62.27% when fraction 12 (pH 10.0) was applied, which was followed by fractions 11 (pH 9.4) and 9 (pH 8.2) with values of 61.00 and 48.70%, respectively (p < 0.05). The highest antibacterial activities against P. aeruginosa were observed in fractions 9, 11 and 12 with values of 51.13, 52.73 and 51.00%, respectively (p > 0.05). The growth of S. aureus was inhibited with the highest value of 38.00% by fraction 12 (pH 10.0), followed by fractions 11 (pH 9.4) and 9 (pH 8.2) with 35.36 and 34.14%, respectively (p < 0.05). The findings of this section demonstrated that charges of peptide molecules will affect its antibacterial activities. Results revealed that most of the basic fractions exhibited strong antibacterial properties that could be attributed to the presence of basic amino acids within the sequences of bioactive peptides.

Among sub-fractions collected, fraction No. 9, 11 and 12 which had the highest antibacterial activity (Fig. 1) was further selected and subjected to U-HPLC system coupled to a Q-TOF mass spectrometer to determine their amino acid compositions and peptide sequences.

Antibacterial peptide sequences

The characteristics of the antibacterial peptides are summarized in Table 1. 12 different peptides were sequenced from the A. lecanora. They had 5 to 14 amino acid residues in their sequences, and their molecular weight ranged of 459.54–2299.51 (Da) in their structures. The net charges of identified peptides ranged from − 3 to + 1. Moreover, their isoelectric point varied from 2.87 to 11.04. Total hydrophobicity ratio (%) for each peptide was calculated based on the percentage of hydrophobic amino acid residues such as I, V, L, F, C, M, A, W [17] and ranged from 30 to 55% (Table 1). These twelve peptides derived from bromelain-generated A. lecanora were chemically synthesized using Fmoc protected amino acid synthesis methods. In order to further, confirm antibacterial activity of the synthetic peptides, the peptides were measured as described in previous section. The concentration of synthesized peptide was fixed at 2000 µM.

Table 1.

Bacterial growth inhibition activities (%) of bromelain-generated A. lecanora peptides at concentration of 2000 µM

| Peptide no. | Peptide sequences | Total hydrophobic amino acids (%)* | Net charge at pH 7 | P. aeruginosa | Pseudomonas sp. | E. coli | S. aureus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LREMLSTMCTARGA | 50 | +1 | 73.50 ± 2.10a | 75.30 ± 1.30a | 67.26 ± 1.46a | 56.34 ± 1.23a |

| 2 | ATSFREALRCGAE | 46 | 0 | 60.75 ± 2.21b | 63.42 ± 2.70b | 53.42 ± 1.04d | NDc |

| 3 | IVGPQG | 33 | 0 | 56.90 ± 2.40b | 60.55 ± 1.34bc | NDe | NDc |

| 4 | NADPLG | 33 | − 1 | 27.50 ± 1.21f | 26.90 ± 1.00e | NDe | NDc |

| 5 | GPAGIVG | 42 | 0 | 45.00 ± 0.40d | 42.30 ± 1.40d | 64.56 ± 2.35b | NDc |

| 6 | PVQADQCLDITHQIYQPQSD | 30 | − 3 | 22.50 ± 0.32h | 20.10 ± 2.10f | NDe | NDc |

| 7 | LAGVSGASVAEHVT | 50 | − 1 | 20.00 ± 1.23h | 18.80 ± 1.20f | NDe | NDc |

| 8 | GPQIVG | 33 | 0 | 40.30 ± 2.00e | 30.10 ± 1.04e | 58.87 ± 1.84c | NDc |

| 9 | IGITG | 40 | 0 | 40.50 ± 2.50e | 27.70 ± 2.30e | NDe | NDc |

| 10 | DGADEAAAA | 55 | − 3 | 25.50 ± 1.10g | 20.60 ± 1.60f | NDe | NDc |

| 11 | AVGPAGPRG | 33 | +1 | 51.50 ± 2.90c | 58.30 ± 2.00c | NDe | NDc |

| 12 | VAPAWGPWPKG | 45 | +1 | 68.60 ± 1.03a | 64.45 ± 1.50b | NDe | 50.00 ± 1.71b |

Each value represents the mean ± SD of three replications; ND not detected

*Calculated based on the percentage of hydrophobic residues (I, V, L, F, C, M, A, W) in the peptide sequences (Sila et al. [17])

a–eMeans with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05

Antibacterial activity of A. lecanora peptides

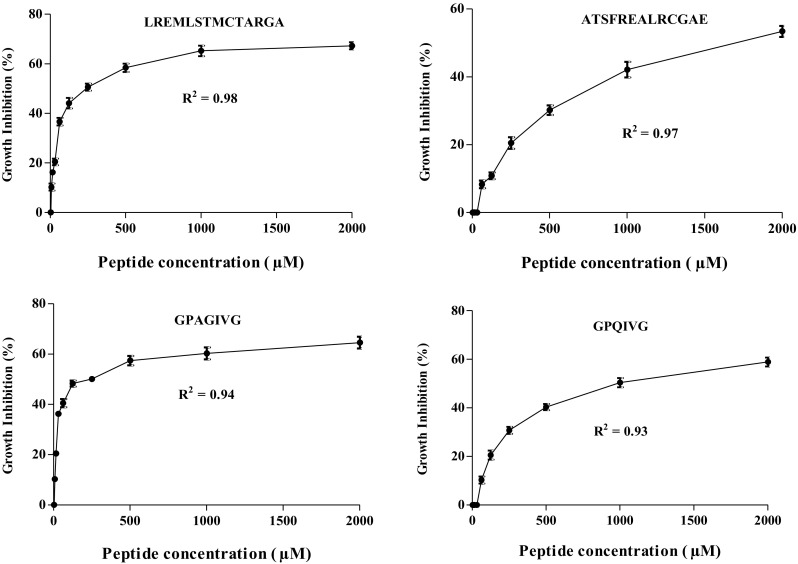

The effect of identified peptides to inhibit the growth of selected bacteria was investigated at 2000 µM, and results are shown in Table 1. All identified peptides inhibited the growth of P. aeruginosa and Pseudomonas sp. with a similar pattern. The highest activity was observed when LREMLSTMCTARGA was used followed by VAPAWGPWPKG, ATSFREALRCGAE, IVGPQG, AVGPAGPRG, GPAGIVG, IGITG, GPQIVG, NADPLG, DGADEAAAA, PVQADQCLDITHQIYQ and LAGVSGASVAEHVT. Peptide LREMLSTMCTARGA inhibited the growth of P. aeruginosa and Pseudomonas sp. by 73.50 and 75.38%, respectively followed by peptides VAPAWGPWPKG with 68.60 and 64.45%, ATSFREALRCGAE by 60.75 and 63.42% and peptide IVGPQG with 56.90 and 60.55%, respectively. The inhibitory effect of peptides on the growth of P. aeruginosa and Pseudomonas sp. were concentration dependent. Moreover, 4 out of 12 peptides inhibited the growth of E. coli. The inhibitory activity of peptides LREMLSTMCTARGA, GPAGIVG, GPQIVG, and ATSFREALRCGAE was concentration dependent, and the maximum inhibition was observed at 2000 μM by values of 67.26, 64.56, 58.87 and 53.42%, respectively (Table 1). Figure 2 shows the relationship between the concentration of the peptides and their inhibitory activities against E. coli. The inhibitory activities of peptides on the growth of E. coli increased non-linearly with increasing concentration with R2 > 0.91. The presence of glycine at the N-terminal of GPAGIVG, GPQIVG may contribute to their effect against E. coli. This finding is in agreement with Jang et al. [18], who reported that thelycine at the N-terminal of peptides enhance its anti-bacterial activity, especially against E. coli. The growth of S. aureus was inhibited only by two identified peptides namely, LREMLSTMCTARGA and VAPAWGPWPKG with the values of 56.34% and 50.00%, respectively (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Growth inhibition activities (%) of bromelain-generated A. lecanora peptides against E. coli at different concentrations between 3.90 and 2000 µM. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three replications

Owing to the possible cytotoxicity of bioactive peptides on the eukaryotic cells [12], the haemolytic activity of identified peptides was investigated on human erythrocytes at 4000 µM in PBS. Identified peptides had no hemolytic activity; therefore, these peptides would be safe, non-toxic and would not cause damage to the host cells at concentrations that kill bacteria under these conditions.

Although, many relationships between peptide structure and antibacterial activity have been described [19], the most antibacterial peptides have two common functionalities, including a net positive charge and an amphipathic structure. The electrostatic interaction between the positively charged peptide and the negatively charged bacterial surface due to the negatively charged head groups of bilayer phospholipids is generally considered to be the initial step in many of the proposed models of antibacterial activities. Once attracted to the bacterial surface, the amphipathic structure promotes peptide insertion into the hydrophobic core of the cell membrane [20].

Besides these two important features, size, amino acid composition and sequences, structure and total hydrophobicity of peptides are all-important [21]. Most peptides with antibacterial activity have been characterized as having 10 to 50 amino acid residues [3]. The size of 12 identified peptides used here ranged from 5 to 20 amino acid residues (Table 1), and three peptides that showed the highest activities against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria contain 11 to 14 amino acid residues. Although, the peptides with small size did not inhibit the growth of S. aureus, they showed inhibitory activities against Gram-negative bacteria. This results agreed with Hwang et al. [22] which was reported the low molecular weight peptides exhibited higher antibacterial activity against Gram-negative strain such as E. coli and P. aeruginosa.

The results showed that the anionic peptides have anti-bacterial activities against both P. aeruginosa and Pseudomonas sp., but they did not inhibit the growth of E. coli and S. aureus. The net negative charge of peptides NADPLG, PVQADQCLDITHQIYQPQSD, LAGVSGASVAEHVT and DGADEAAAA were − 1, − 3, − 1 and − 3, respectively (Table 1). The antibacterial activities of these peptides with 7, 20, 14 and 9 amino acid residues against P. aeruginosa were 27.50, 22.50, 20.00 and 25.50%, respectively. The corresponding values against Pseudomonas sp. were 26.90, 20.10, 18.80 and 20.60%, in the same order. It seems that the ability of growth inhibitory activities of anionic peptides were lower than cationic peptides (Table 1). The antibacterial activity of anionic peptides with 6 amino acid residues has been reported [20]. Hydrophobicity of peptides enables water-soluble anti-bacterial peptides to partition into the membrane lipid bilayer. In this study, the hydrophobicity of identified peptides that is expressed based on total hydrophobic amino acid content (%) ranged from 33 to 50%. It was reported that the antibacterial peptides contain at least 50% hydrophobic amino acid residues [23]. In this sense, Aissaoui et al., 2017 reported the high antibacterial activity of the peptide was determined at a total hydrophobic ratio of about 33% [24]. The highest antibacterial activities on both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria were obtained when peptide LREMLSTMCTARGA with 50% hydrophobic amino acid content was used (Table 1). The growth of Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus) was inhibited by peptides with above 45% hydrophobicity; while, the peptides with low hydrophobic amino acid content showed antibacterial activities against Gram-negative bacteria. The inhibitory activities of identified cationic peptides against P. aerogeniosa and Pseudomonas sp. increased with increasing hydrophobicity. In this connection, [17] also reported that antibacterial activities of peptide sequences from barbel muscle hydrolysates are due to the existence of hydrophobic residues in their sequences. The peptide GPAGIVG with 42% hydrophobicity was the only exception, and its activity was lower than AVGPAGPRG and IVGPQG with 33% hydrophobicity. The difference between GPAGIVG and AVGPAGPRG may be related to their net charges, which was 0, and 1, respectively. However, the peptides GPAGIVG and IVGPQG have the same net charges. It can be explained that the hydrophobicity is not the only factor affecting the anti-bacterial activities of peptides.

In this regard, the importance of amino acid residues has been reported. The presence of basic amino acid residues (i.e. lysine or arginine), the hydrophobic residues (i.e. alanine, leucine, phenylalanine or tryptophan), and other residues such as isoleucine, tyrosine and valine in the structure of anti-bacterial peptides has been reported [20]. Lysine (K) or arginine (R) residues as positively charged amino acids in peptide sequences play an important role in interacting with the negative charge (s) in lipid A of lypopolysacharide (LPS) for Gram-negative bacteria and negative charge (s) of teichoic acids on the outer surface of the peptidoglycan (PDG) [21, 25]. Similarly, the identified peptides in the present study contained hydrophobic and basic amino acid residues as mentioned above in their structures. Lysine (K) (1 molecule) was only found in peptide VAPAWGPWPKG; while, arginine (R) was found in LREMLSTMCTARGA (2 molecules), ATSFREALRCGAE (2 molecules) and AVGPAGPRG (1 molecule). These 4 peptides showed the highest anti-bacterial activities compared to other identified peptides (Table 1). The peptide VAPAWGPWPKG with second rank in terms of anti-bacterial activities against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria has 3 proline (P) and 2 tryptophan (w) molecules in its structure. Moreover, it is notable that the proline (P) residue in the structure might be important for anti-bacterial effectiveness [26].

Therefore, A. lecanora will be an excellent and economical source for the production of hydrolysates and bioactive peptides with antibacterial activity. This is the first report of the antibacterial peptides derived from A. lecanora hydrolysate. However, further study is needed to investigate that relevance of amino acid component and the biological mechanism.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Malaysia Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI) under Project No. 10-05ABI-FB 037.

Contributor Information

Raheleh Ghanbari, Email: ghanbari.rahele@yahoo.com.

Afshin Ebrahimpour, Email: a_ebrahimpour@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Sarmadi B, Ismail A, Hamid M. Antioxidant and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activities of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) autolysates. Food Res. Int. 2011;44:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S-K, Wijesekara I. Development and biological activities of marine-derived bioactive peptides: A review. J Funct. Foods. 2010;2:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2010.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hancock R. E. W, & Sahl, H.-G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat Biotechnol. 24: 1551–1557(2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gallo RL, Murakami M, Ohtake T, Zaiou M. Biology and clinical relevance of naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides. J Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2002;110:823–831. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.129801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y.-x., Zou, A.-h., Manchu, R.-g., Zhou, Y.-c., & Wang, S.-f. Purification and antimicrobial activity of antimicrobial protein from Brown-spotted Grouper, Epinephelus fario. Zool Res. 6627–632(2008).

- 6.Shahidi F, Zhong Y. Bioactive peptides. J. AOAC. Int. 2008;91:914–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanbari R, Ebrahimpour A, Abdul-Hamid A, Ismail A, & Saari N. Actinopyga lecanora hydrolysates as natural antibacterial agents. Int J. Mol. Sci. 13: 16796–16811(2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Church FC, Swaisgood HE, Porter DH, Catignani GL. Spectrophotometric assay using o-Phthaldialdehyde for determination of proteolysis in milk and isolated milk proteins. J Dairy. Sci. 1983;66:1219–1227. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(83)81926-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Z, Dong S, Xu J. ZengM, Song H, & Zhao Y. Production of cysteine-rich antimicrobial peptide by digestion of oyster (Crassostrea gigas) with alcalase and bromelin. Food Control. 2008;19:231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2007.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang W, Zhang H, Wang L, & Qian H. Antimicrobial peptide isolated from ovalbumin hydrolysate by immobilized liposome-binding extraction. Eur Food. Res. Technol. 1–10(2013).

- 11.Nokihara K, Yamamoto R, Hazama M, Wakizawa O, & Nakamura S. Design and applications of a novel simultaneous multiple solid-phase peptide synthesizer, In R. Epton (Ed.) (pp. 445–448). Andover, UK: Intercept Limited(1992).

- 12.Nakajima Y, Ishibashi J, Yukuhiro F, Asaoka A, Taylor D, & Yamakawa, M. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of tick defensin against Gram-positive bacteria. Biochimicaet Biophysica Acta.1624: 125–130(2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Osman A, Goda H, Abdol-Hamid M, Badra S, Otte J. Antibacterial peptide generated by alkalase hydrolysis of goat whey. LWT- Food sci. technol. 2016;65:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.08.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam H.-T, Josserand J, Lion N, & Girault H H. Modeling the isoelectric focusing of peptides in an OFFGEL multicompartment cell. J. Proteome Res. 6: 1666–1676 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hancock REW. Cationic peptides: effectors in innate immunity and novel antimicrobials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2001;1:156–164. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dathe M, Nikolenko H, Meyer J, Beyermann M, Bienert M. Optimization of the antimicrobial activity of magainin peptides by modification of charge. FEBS Letters. 2001;501:146–150. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02648-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sila A, Nedjar-Arroume N, Hedhili K, Chataigne G, Balti R, Nasri M, et al. Antibacterial peptides from barbel muscle protein hydrolysates: Activity against some pathogenic bacteria. LWT Food. Sci. Technol. 2014;55:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang A, Jo C, Kang K-S, Lee M. Antimicrobial and human cancer cell cytotoxic effect of synthetic angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides. Food. Chem. 2008;107:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fjell C. D, Hiss J, AHancock, R. E. W, & Schneider G. Designing antimicrobial peptides: form follows function. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov.11:3751(2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbi. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hali, N.R.A, Yusof H. M, & Sarbon N.M. Functional and bioactive properties of fish protein hydrolysates and peptides: A comprehensive review. Trends Food. Sci. Technol. (2016).

- 22.Hwang C-F, Chen Y-A, Luo C, Chiang W-D. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of peptide fractions from flaxseed protein hydrolysed by protease from Bacillus altitudinis HK02. Int Food. Sci. Technol. 2016;51:681–869. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conlon J. M, Al-Ghaferi N, Abraham B,&Leprince J. r. m. Strategies for transformation of naturally-occurring amphibian antimicrobial peptides into therapeutically valuable anti-infective agents. Methods. 2007;42:349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aissaoui N, Chobert J-M, Haertlé T, Marzouki M-N, Abidi F. Purification and biochemical characterization of a neutral serine protease from trichoderma harzianum. use in antibacterial peptide production from a fish by-product hydrolysate. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017;182:831–845. doi: 10.1007/s12010-016-2365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dennison SR, Wallace J, Harris F, Phoenix DA. Amphiphilic α-Helical antimicrobial peptides and their structure/function relationships. Protein. Pept. Lett. 2005;12:31–39. doi: 10.2174/0929866053406084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park CB, Yi K-S. MatsuzakiK, Kim M. S, & KimS. C. Structure-activity analysis of buforin II, a histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptide: the proline hinge is responsible for the cell-penetrating ability of buforin II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:8245–8250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150518097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]