Abstract

The purpose of this study was to compare the beneficial effects of galactooligosaccharide (GOS), lactulose, and a complex-oligosaccharide composed with GOS and lactulose (Com-oligo) on loperamide-induced constipation in SD rats. Rats were randomly divided into the following eight groups: the normal group (Nor); constipation control group (Con); and 6 constipation groups fed low and high doses of GOS, lactulose (Lac), and Com-oligo, respectively. Com-oligo increased intestinal transit ratio and relieved constipation in loperamide-treated rats. The group receiving a high dose of Com-oligo favorably regulated gastrointestinal functions such as pellet number, weight, moisture content, short chain fatty acid, intestinal transit ratio, and bifidobacterium number in constipated rats. In addition, Com-oligo restored peristalsis of the small intestine, morphology of colon, and increased interstitial cells of Cajal area. Thus, providing Com-oligo as an oligosaccharide ingredient in nutritional formulas could benefit the health of the gastrointestinal tract.

Keywords: GOS, Lactulose, Oligosaccharides, Constipation, Short-chain fatty acids, Crypt cell

Introduction

Constipation is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders and is associated with insufficient bowel movements, bowel obstruction, and the feeling of incomplete evacuation [1]. Constipation is associated with changes in diet and psychological and social factors, which can lead to chronic gastrointestinal disorders. It is necessary to apply a combination of laxatives to improve physical bowel movements [2].

There is an increasing interest in improving gastrointestinal disorders and alleviating fecal complaints with probiotics and prebiotics which include live microbial supplements and dietary fiber, respectively [3, 4]. Recently, prebiotics have focused on gaining more benefit from probiotics. Prebiotics have several advantages over probiotics, including greater resistance to digestive enzymes, lower cost, lower risks, and relative ease of incorporation into the diet [5]. Oligosaccharides are commonly known prebiotics and powerfully affect bowel health [9]. Galactooligosaccharides (GOS) and fructooligosaccharides can effectively promote the proliferation of specific health-promoting gut microbes [6]. Rycroft et al. [7] found that GOS and lactulose showed the most effective prebiotic activities when comparing the fermentation of commercial prebiotics. GOS refer to non-digestible oligomeric carbohydrates that are produced from lactose by β-galactosidases [8]. Many clinical studies have assessed the effect of GOS on the intestinal microbiota of infants, adults, pregnant and lactating women, intestinal bowel disease patients, and healthy adults [9, 10].

Lactulose has been one of the most frequently used prebiotics in the improvement of gastrointestinal disorders for more than 50 years. It is resistant to hydrolysis by human small intestinal disaccharidases and hence, it reaches the colon undigested. In the colon, it is selectively metabolized by intestinal microbes, giving rise to the formation of CO2, hydrogen gas, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), causing a decrease in pH and an increase in fecal mass [11].

An oligosaccharide Com-oligo composed of GOS and lactulose was prepared. Com-oligo is composed of 51.7% lactulose, 14.2% lactose, 15.8% galactooligosaccharides, 12.3% of a mixture of glucose and galactose, and 6.0% other ingredients [12]. It was developed as a nutraceutical material to improve bowel function. Low (10%) and high dose (15%) intake of Com-oligo showed the enhancement of gastrointestinal transit and the alleviation of constipation in loperamide-induced rats with increase of fecal excretion and decrease of fecal pellets number in our previous study [12]. However, studies on the components of Com-oligo which are responsible for this physiological activity, have been limited. Therefore, the constipation-improving effects of GOS and lactulose, which are components of Com-oligo, were compared to Com-oligo in loperamide-induced constipation rats.

Materials and methods

Animals and reagents

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (160–180 g) were purchased from Central Lab. Animal Inc. (Seoul, South Korea) and were kept in a specific room free from pathogen at 21 ± 1 °C with 50–55% relative humidity and lighting (12 h day/night cycles). All experiments were approved by the Korea University Animal Care Committee (KUIACUC-2015-102). Com-oligo was prepared using 51.7% lactulose, 14.2% lactose, 15.8% GOS, 12.3% of a mixture of glucose and galactose, and 6.0% of other ingredients, such as tagatose and epilactose by Neo Crema Co. Ltd. (South Korea). GOS (50%, w/w) and lactulose (30%, w/w) were obtained by Neo Crema Co. Ltd. Chemicals including loperamide were of reagent grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Experimental design

Rats were divided into the following 8 groups (6 rats/group): normal (Nor), control (Con; treated with loperamide, but not oligosaccharide), GOS-L (treated with loperamide and 0.6% GOS), GOS-H (treated with loperamide and 1.2% GOS), Lac-L (treated with loperamide and 4% lactulose), Lac-H (treated with loperamide and 8% lactulose), Com-L (treated with loperamide and 4% Comp-oligo), and Com-H (treated with loperamide and 8% Comp-oligo) groups. Com-oligo, GOS (50%, w/w), and lactulose (30%, w/w) were diluted with drinking water to the final concentrations of 4% and 8%, as a low dose and a high dose, respectively. For 4 weeks, only drinking water was supplied to the normal and control groups. Constipation was induced by injecting loperamide (4 mg/kg of body weight) twice a day (9 AM and 5 PM) for 7 days.

Measurement of fecal pellets

Fecal pellets were collected every day during 29–35 days after constipation induction. Fecal pellet number and fecal pellet weight were measured. Fecal water content was measured during 29–35 days after constipation induction. After being dried in an oven at 70 °C for 24 h, the water content of the feces was determined by subtracting the dry weight from the wet one.

Intestinal transit ratio

Intestinal transit ratio was measured using the slightly modified method of Yu et al. [13]. GOS, lactulose, and Com-oligo were dissolved in water before being administered orally with 1 mL of 8% charcoal. Thirty minutes after charcoal administration, the rat was sacrificed and the intestinal tract was dissected. The distance covered by the charcoal meal from the pylorus and the total length of small intestine were measured. Intestinal transit ratio was expressed as a percentage of the length of the small intestine from the pylorus to the cecum, using the following formula:

T: the intestinal tract ratio, A: total length of small intestinal tract, B: distance moved by the charcoal.

Measurement of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

SCFA concentration was measured according to Demigne and Rémésy [14]. Five mL of methanol was used to extract 1 g of feces, and the extract was centrifuged at 28,000× g for 15 min. The supernatants were filtered and analyzed by Agilent 6890 N gas chromatography system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Agilent 6890 N equipped with a flame ionization detector and a GC column (DB-FFAP 123-3253, 50 m × 0.32 mm × 0.50 μM). Nitrogen gas was used as the carrier with a flow rate of 1.4 mL/min and a sample injection volume of 1 μL. Inlet and detector temperatures were 200 °C and 240 °C, respectively. Acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid contents were used as standards.

Bifidobacteria counts

The effect of Com-oligo on the growth of bifidobacteria in the cecum was determined. Cecal contents (0.1 g) was suspended in 0.9 mL of sterile peptone water in decimal dilutions. Bifidobacteria were cultured using BS agar (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), a medium designed for selection of bifidobacteria [15, 16]. The diluted sterile solution (100 μL) was spread on a selective BS agar and placed in an incubator at 37 °C for anaerobic incubation. After 72 h incubation, the number of colonies were counted. The cecal bifidobacterial count was expressed as log10 [colony forming units (CFU)]/g cecal content.

Histology of the distal colon

Ten% formalin was used to fix the intestinal tissue, and, then, paraffin was used to embed the tissue. After that, the embedded tissue was sectioned into the slices of 5 μm thickness which underwent the deparaffinization with xylene and, then, rehydration. After the staining with Alcian blue, the sections were rinsed, followed by the staining with a nuclear fast red solution for 30 s and re-dehydration with ethanol. After that, they were dehydrated, washed, and sealed with xylene. An optical microscope (Axiovert S100, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to observe the Alcian blue-positive mucus layer.

Immunohistochemistry examination

Tissue Sections (5 μm thickness) were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated. The retrieval of antigens was then done by heating in citrate buffer solution in a microwave oven at 98 °C for 20 min and then immersing in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) [17, 18]. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubation with 3% H2O2 for 10 min and nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with normal goat serum for 10-15 min. The sections were then incubated with primary rabbit anti-c-kit antibodies (1:200) at 37 °C for 2 h. After washing in PBS, sections were further incubated with biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies for 10 min at 37 °C. The sections were subsequently incubated with streptavidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase for 15 min at 37 °C. Slides were developed with a DAB horseradish peroxidase color development kit (ZhongShan JinQiao, Beijing, China), then the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted in neutral balsam. Tissue sections were examined under a light microscope and the number of pixels with RGB values in the dyed ICC was determined using the MATLAB program.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and were analyzed using SPSS 12.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Duncan’s multiple range test was used to compare the differences among various group. Differences were considered significant at the α = 0.05 level of significance.

Results and discussion

Fecal pellet number and fecal water content

Constipation was assessed by the number and water content of fecal pellets, to evaluate the effects of oligosaccharides in the rat loperamide-induced constipation model. The fecal pellet numbers showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the Nor and Con groups after loperamide-induced constipation. The water content and weight of fecal pellets tended to increase with intake of oligosaccharide, but there was no significant difference when compared to the Con group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of oligosaccharides on the number, weight, and water content of fecal pellets during loperamide-induced constipation

| Group | Number of fecal pellets (count/day) | Weight of fecal pellets (g/day) | Water content of fecal pellets (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nor | 43.00 ± 1.49a,2 | 9.33 ± 0.35ab | 21.16 ± 7.46ns1 |

| Con | 29.33 ± 2.00b | 8.45 ± 0.43d | 20.90 ± 4.42 |

| GOS-L | 35.33 ± 2.46ab | 9.24 ± 0.44bc | 23.91 ± 4.76 |

| GOS-H | 33.00 ± 3.31b | 9.01 ± 0.56c | 22.39 ± 2.73 |

| Lac-L | 36.83 ± 3.31ab | 9.38 ± 0.41ab | 24.27 ± 8.01 |

| Lac-H | 28.33 ± 3.20b | 8.47 ± 0.52d | 27.23 ± 4.07 |

| Com-L | 31.83 ± 2.96b | 9.06 ± 0.50c | 25.91 ± 4.80 |

| Com-H | 36.83 ± 2.58ab | 9.51 ± 0.69a | 26.52 ± 3.43 |

Nor, normal group; Con, control group; GOS-L, GOS 4% treated group; GOS-H, GOS 8% treated group; Lac-L, lactulose 4% treated group; Lac-H, lactulose 8% treated group; Com-L, complex-oligo 4% treated group; Com-H, complex-oligo 8% treated group. 1ns no significant different. 2Different letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05)

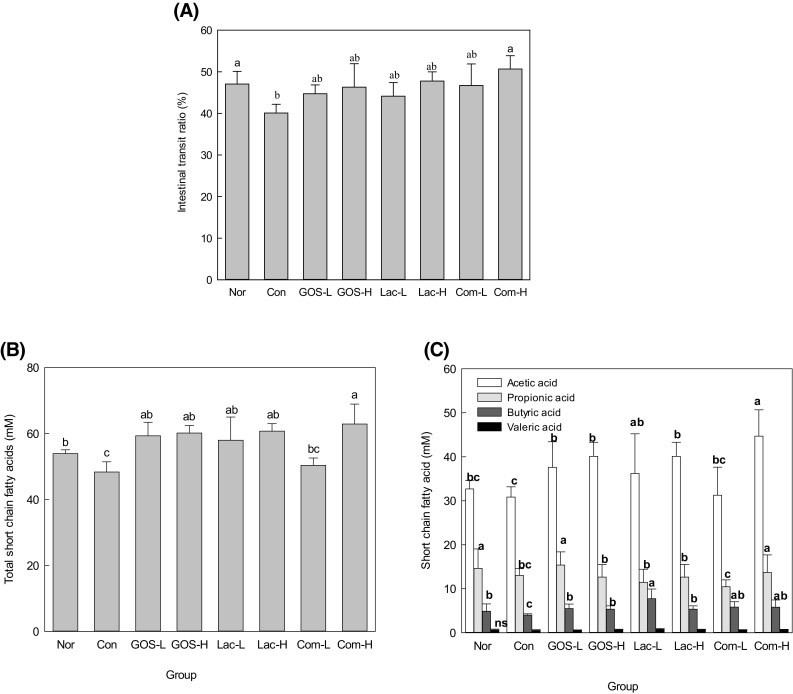

A marked decrease in fecal discharge (Table 1) and a delayed fecal pellet transit [Fig. 1(A)] in the large intestinal lumen were observed in constipation. The degree of fecal excretion was significantly influenced by the ingestion of oligosaccharides. The water content of feces increased with the intake of oligosaccharide, but no statistical significance was observed. Fecal pellet numbers and fecal water content have been used as indicators to determine constipation relief [19, 20]. The fecal weight of the oligosaccharide intake groups tended to be higher than that of the control group, in which Com-H group showed the highest.

Fig. 1.

Effect of oligosaccharides on gastrointestinal transit ratio (A), total short chain fatty acids (B), and acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, and valeric acid (C). Nor, normal group; Con, control group; GOS-L, GOS 4% treated group; GOS-H GOS, 8% treated group; Lac-L, lactulose 4% treated group; Lac-H, lactulose 8% treated group; Com-L, complex-oligo 4% treated group; Com-H, complex-oligo 8% treated group

Effect of oligosaccharide on intestinal transit ratio

Figure 1(A) showed the intestinal transit ratio. The intestinal transit ratio of the Con group significantly decreased to 40.1% compared to the Nor group (47.1%, p < 0.05). The oral intake of a high dose of lactulose or GOS tended to increase the intestinal transit ratio, but there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) compared to the controls. However, the high dose intake of Com-oligo (Com-H) increased the intestinal transit ratio compared to the Con group. Compared with the control group, intestinal transit ratio increased regardless of the type of oligosaccharide intake group. Com-H showed significant differences (p < 0.05) between the groups, while the other samples showed no significant difference (p > 0.05). However, GOS-H, Lac-H, and Com-L showed similar values. This result showed that Com-H is more effective than the other samples.

Since the intestinal tract movement reflects the overall intestinal motility, the intestinal charcoal transit ratio is important for diagnosing constipation [19]. In the Com-H group, the Intestinal transit ratio moved by charcoal was 10.7% faster than the con group, suggesting that compelx-oligoscccahride could improve intestinal motility at high doses. The compelx-oligosaccahride increased intestinal motility which in turn increased colonic movement in the rats. The laxative effect of the complex-oligosaccharide may also be due to changes in intestinal motility leading to intestinal movement and increased bowel movements [21].

Concentration of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

Non-digestible carbohydrates, including prebiotics, can be fermented in the colon and enhance SCFA production by intestinal microbes. SCFAs have been associated with a reduction in intestinal disorders, including constipation [25].

Figure 1(B) shows the total SCFAs (acetic, propionic, butyric, and valeric acid) in cecum. There was a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the total SCFAs contents of in the Com-H group from the Con group, indicating changed SCFA composition by constipation. Intake of oligosaccharides, except Com-L, tended to increase total SCFA concentration. The amount of SCFA was lower in 4% Com-oligo administration than in GOS or lactulose administration. This result is conjectured to be resulted from the difference of GOS level; Com-oligo only has 4% GOS. In general, galactose-containing oligosaccharides, namely lactulose and GOS, were ostensibly effective in production of SCFA [22].

Figure 1(C) shows that SCFA production was in the order of acetate > propionic acid > butyric acid > valeric acid. Regardless of the sample kinds, the short chain fatty acid content of the high dose group was higher than that of the low dose group, except for butyric acid. In particular, Com-H group showed a significant increase in acetic acid level compared with the control or the other groups, presenting the highest level (44.7%). In acetic acid and propionic acid contents, Com-H showed the highest level of 44.7% and 13.67%. Lac-L showed the highest level of butyric acid (7.7%) among samples. Therefore, these results show that the improved intestinal environment caused by oligosaccharide intake can be attributed to increased SCFA content in the cecum. In particular, a high dose intake of Com-oligo can be effectively used as an energy source by the bacteria in the large intestine, causing a considerable change in the gut microflora and resulting in a dominance of beneficial microorganisms over harmful bacteria. This result suggests that intestine Com-H is effective in the short chain fatty acid production.

In the last several years, SCFAs have been reported to prevent and alleviate intestinal disorders [23]. SCFAs in the cecum of constipated rats were measured after feeding GOS, lactulose, and Com-oligo (Fig. 1). Com-oligo affected the concentrations of total SCFAs, acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, and valeric acid. Particularly, Com-oligo was shown to increase the total SCFAs in which acetic acid level increased by 40% in Com-oligo. Dietary components, especially prebiotics, increase fecal mass and bacterial mass and thus have a stool bulking effect. Fermentation plays an important role in both the colon and systemic levels of SCFAs [24]. Here, the intake of oligosaccharides also increased butyric acid compared to controls (Fig. 1). Colonic epithelial cells prefer to use butyrate as an energy source, even though there are competing substances such as glutamine and glucose. Butyrate is considered as an important nutrient that determines the metabolic activity and growth of colon cells and can be a major protective factor on intestinal disorders, although there is disagreement on these data [25].

Effects on bifidobacteria numbers in cecal contents

Bifidobacteria are beneficial intestinal microorganisms. Bifidobacteria can alleviate constipation by breaking down sugar and lowering intestinal pH. The total number of bifidobacteria in the cecum was analyzed (Fig. 2). The Con group given loperamide alone, showed the lowest level of bifidobacteria. GOS-H showed the highest level of bifidobacteria among all experimental groups. There was not a significant difference (p > 0.05) in bifidobacterium number between the GOS-H and Com-H groups.

Fig. 2.

Effect of oligosaccharides on Bifidobacterium microflora. Nor, normal group; Con, control group; GOS-L, GOS 4% treated group; GOS-H: GOS 8% treated group; Lac-L, lactulose 4% treated group; Lac-H, lactulose 8% treated group; Com-L, complex-oligo 4% treated group; Com-H, complex-oligo 8% treated group

Com-oligo composed with lactulose and GOS was developed for the alleviation of intestinal disorders, especially constipation. Our results investigated the effect of Com-oligo on alleviating constipation in loperamide-treated rats. Bifidobacteria are major human intestinal microflora that can contribute to human health and longevity. Among the experimental groups in this study, a high dose intake of GOS and Com-oligo resulted in the highest level of bifidobacteria. The ability of GOS to affect microbial changes in the human intestine was first reported in 1993 [26]. Increases in bifidobacteria induced by GOS have been reported in many other studies [27, 28]. Changes in the mucous homogenate for hydrolysis of lactulose are used as an indicator of potential absorption and this was affected by galactose [29]. Com-oligo has both GOS and lactulose and therefore, is estimated to have the combined effect of GOS and lactulose on bifidobacteria.

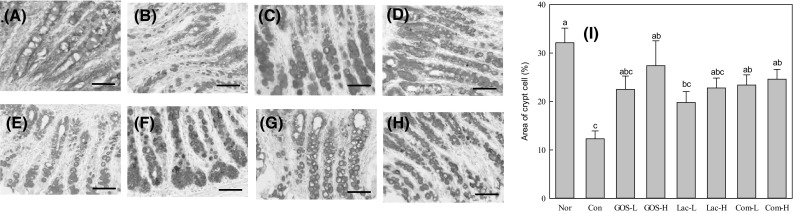

Histological findings

The photomicrographs showing the effect of oligosaccharide supplementation on distal colon tissue of loperamide-induced rats are shown in Fig. 3. After hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of colonic tissues, the Nor group showed morphological features of epithelial cells with well-separated crypt and goblet cells and had a thick layer of colon tissue [Fig. 3(A)]. In contrast, layer decreasing and crypt shortening were evident in the rats of the Con group. However, mucosal damage was reduced in oligosaccharide-treated groups. The Con group, with only loperamide administration, showed a significantly lower thickness of colonic mucosa than the Nor group [Fig. 3(I), p < 0.05]. Intake of oligosaccharides, except GOS-L, significantly inhibited the decrease of mucosal thickness induced by loperamide (p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining and thickness of colonic mucosa. Nor, normal group (A); Con, control group (B); GOS-L, GOS 4% treated group (C); GOS-H, GOS 8% treated group (D); Lac-L, lactulose 4% treated group (E); Lac-H, lactulose 8% treated group (F); Com-L, complex-oligo 4% treated group (G); Com-H, complex-oligo 8% treated group (H); Thickness of colonic mucosa (I). The scale bar at the bottom of each graph is 100 nm

Figure 4 shows the result of the staining with Alcian blue to find out the distribution and amount of mucin. It was shown that the Nor group had a very good arrangement of mucin-producing goblet cells [Picture-(A)]. Oligosaccharide intake significantly increased both the number of crypt cells and the amount of mucin compared to the Con group [Picture-(B)]. Increased crypt cell area was observed in oligosaccharide-supplemented rats compared with rats given loperamide alone [Con group, graph-(I)].

Fig. 4.

Alcian blue effect of oligosaccharide on area of crypt cells staining and area of crypt cell. Nor, normal group (A); Con, control group (B); GOS-L GOS, 4% treated group (C); GOS-H GOS, 8% treated group (D); Lac-L, lactulose 4% treated group (E); Lac-H, lactulose 8% treated group (F); Com-L, complex-oligo 4% treated group (G); Com-H, compelx-oligo 8% treated group (H); Area of crypt cell (I). The scale bar at the bottom of each graph is 100 nm

Regardless of the type of oligosaccharide, the thickness of mucosa became thicker when all samples were administered at a higher concentration than the control. Among the samples, the thickness of the sample was in the order of GOS < Lac < Com Oligosaccharides. Namely, Crypt cell regeneration and colon mucosal restoration were significantly increased in the Com-H groups compared to the Con group. These results prove that Com-H inhibits the destruction of the epithelial crypt and inflammation of the colon effectively. As shown in the results, GOS and Lac also increased the colon mucosal restoration compared to the control group, and the synergistic effect of the Com sample of mixed with the GOS and Lac at a certain ratio was shown.

In H&E and Alcian blue staining of colonic tissues (Figs. 3, 4), crypt shortening and mucin depletion were detected moderately in the constipation group (Con). This decrease in epithelial mucus seems to have been caused by the decrease in the thickness of the lumen mucus layer and the amount of lumen mucus by loperamide [30]. Crypt cell regeneration and intestinal mucosal recovery were significantly increased in the Com-oligo groups compared to the control group (Figs. 3, 4). Perhaps Com-oligo increases crypt thickness and cell density by providing SCFAs as an energy source, resulting in improved intestinal tract health compared with controls.

Immunohistochemistry findings

ICC are a group of cells in the gastrointestinal tract that play an important role in regulating intestinal motility. ICC are present in all layers of the colon [31]. In the normal group, c-kit-positive immunoreactive structures are shown in brown (Fig. 5). ICC area was measured by the intensity of the photomicrographs using the MATLAB program. ICC area decreased and was reduced in each layer in the Con group compared with the Nor and oligosaccharide-supplemented (GOS, Lac, and Com-oligo) groups [Fig. 5(I)]. Interestingly, ICC area was significantly increased in the oligosaccharide-supplemented groups, except for Lac-L (p < 0.05). In particular, a high dose intake of Com-oligo resulted in the largest ICC area.

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemically (IHC) staining and area of ICC. Nor, normal group (A); Con, control group (B); GOS-L, GOS 4% treated group (C); GOS-H, GOS 8% treated group (D); Lac-L, lactulose 4% treated group (E); Lac-H, lactulose 8% treated group (F); Duo-L, DuOligo 4% treated group (G); Duo-H, DuOligo 8% treated group (H); Area of ICC (I). The scale bar at the bottom of each graph is 100 nm

More recently, the role of ICC in intestinal motility have become increasingly known. The significant reduction in ICC of colonic specimens with constipation would be expected to disrupt normal colonic motility [32]. The disruption of the ICC network in patients results in slow-transit constipation and acquired megacolon [33]. The results showed a significant decrease in ICC quantified by immunohistochemical techniques. Oligosaccharides, especially Com-oligo, may improve the ICC network, but their mechanism remains unclear.

In conclusion, this study shows that Com-oligo plays an important role in facilitating the intestinal transit and relieving the constipation in loperamide-induced rats. The high dose of Com-oligo was found to favorably regulate gastrointestinal functions by modifying pellet number, SCFAs and bifidobacteria number in the constipated rats. In addition, Com-oligo restored peristalsis of the small intestinal and morphology of the colon and increased ICC area. These results have demonstrated for the first time that Com-oligo, a mixture of GOS and lactulose, is a potential therapeutic material for the constipation prevention.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the High Value-added Food Technology Development Program, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Hyung Joo Suh, Email: suh1960@korea.ac.kr.

Sung Hee Han, Phone: +82 2 3290 5639, Email: sungheeh3@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Filipovic B, Forbes A, Tepes B. Current Approaches to the Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:4957154. doi: 10.1155/2017/4957154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crowell MD, Harris LA, DiBaise JK, Olden KW. Activation of type-2 chloride channels: a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of chronic constipation. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;8:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qian Y, Suo H, Du M, Zhao X, Li J, Li GJ, Song JL, Liu Z. Preventive effect of Lactobacillus fermentum Lee on activated carbon-induced constipation in mice. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:272–278. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu T, Zheng YP, Tan JC, Xiong WJ, Wang Y, Lin L. Effects of Prebiotics and Synbiotics on Functional Constipation. Am J Med Sci. 2017;353:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L, Hu L, Yan S, Jiang T, Fang S, Wang G, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W. Effects of different oligosaccharides at various dosages on the composition of gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in mice with constipation. Food & Function. 2017;8:1966–1978. doi: 10.1039/C7FO00031F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bron PA, Kleerebezem M, Brummer RJ, Cani PD, Mercenier A, MacDonald TT, Garcia-Rodenas CL, Wells JM. Can probiotics modulate human disease by impacting intestinal barrier function? Br J Nutr. 2017;117:93–107. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516004037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rycroft CE, Jones MR, Gibson GR, Rastall RA. A comparative in vitro evaluation of the fermentation properties of prebiotic oligosaccharides. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;91:878–887. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park AR, Oh DK. Galacto-oligosaccharide production using microbial beta-galactosidase: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2010;85:1279–1286. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanaro S, Boehm G, Garssen J, Knol J, Mosca F, Stahl B, Vigi V. Galacto-oligosaccharides and long-chain fructo-oligosaccharides as prebiotics in infant formulas: a review. Acta paediatrica. 2005;94:22–26. doi: 10.1080/08035320510043538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niittynen L, Kajander K, Korpela R. Galacto-oligosaccharides and bowel function. Scandinavian Journal of Food and Nutrition. 2007;51:62–66. doi: 10.1080/17482970701414596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olano A, Corzo N. Lactulose as a food ingredient. J Sci Food Agr. 2009;89:1987–1990. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han SH, Hong KB, Kim EY, Ahn SH, Suh HJ. Effect of dual-type oligosaccharides on constipation in loperamide-treated rats. Nutr Res Pract. 2016;10:583–589. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2016.10.6.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu LL, Liao JF, Chen CF. Anti-diarrheal effect of water extract of Evodiae fructus in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73:39–45. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demigne C, Remesy C. Stimulation of absorption of volatile fatty acids and minerals in the cecum of rats adapted to a very high fiber diet. J Nutr. 1985;115:53–60. doi: 10.1093/jn/115.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeon JR, Choi JH. Lactic acid fermentation of germinated barley fiber and proliferative function of colonic epithelial cells in loperamide-induced rats. J Med Food. 2010;13:950–960. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura T, Nishida S, Mizutani M, Iino H. Effects of yogurt supplemented with brewer’s yeast cell wall on constipation and intestinal microflora in rats. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology. 2001;47:367–372. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.47.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lan HY, Mu W, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Atkins RC. A novel, simple, reliable, and sensitive method for multiple immunoenzyme staining: use of microwave oven heating to block antibody crossreactivity and retrieve antigens. J Histochem Cytochem. 1995;43:97–102. doi: 10.1177/43.1.7822770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu K, Nie S, Li C, Lin S, Xing M, Li W, Gong D, Xie M. A newly identified polysaccharide from Ganoderma atrum attenuates hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;57:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wintola OA, Sunmonu TO, Afolayan AJ. The effect of Aloe ferox Mill. in the treatment of loperamide-induced constipation in Wistar rats. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu D, Zhou J, Wang X, Cui B, An R, Shi H, Yuan J, Hu Z. Traditional Chinese formula, lubricating gut pill, stimulates cAMP-dependent CI(-) secretion across rat distal colonic mucosa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capasso F, Gaginella TS. Laxatives: a practical guide. Springer Science & Business Media (2012)

- 22.Rycroft C, Jones M, Gibson GR, Rastall R. A comparative in vitro evaluation of the fermentation properties of prebiotic oligosaccharides. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;91:878–887. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hijova E, Chmelarova A. Short chain fatty acids and colonic health. Bratislavské lekárske listy. 2007;108:354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slavin J. Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients. 2013;5:1417–1435. doi: 10.3390/nu5041417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupton JR. Microbial degradation products influence colon cancer risk: the butyrate controversy. J Nutr. 2004;134:479–482. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.2.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito M, Deguchi Y, Matsumoto K, Kimura M, Onodera N, Yajima T. Influence of galactooligosaccharides on the human fecal microflora. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 1993;39:635–640. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.39.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vulevic J, Drakoularakou A, Yaqoob P, Tzortzis G, Gibson GR. Modulation of the fecal microflora profile and immune function by a novel trans-galactooligosaccharide mixture (B-GOS) in healthy elderly volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1438–1446. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Depeint F, Tzortzis G, Vulevic J, I’Anson K, Gibson GR. Prebiotic evaluation of a novel galactooligosaccharide mixture produced by the enzymatic activity of Bifidobacterium bifidum NCIMB 41171, in healthy humans: a randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:785–791. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salminen S, Salminen E. Lactulose, lactic acid bacteria, intestinal microecology and mucosal protection. Scandinavian Journal of gastroenterology. 1997;32:45–48. doi: 10.1080/00365521.1997.11720717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimotoyodome A, Meguro S, Hase T, Tokimitsu I, Sakata T. Decreased colonic mucus in rats with loperamide-induced constipation. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2000;126:203–212. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(00)00194-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He CL, Burgart L, Wang L, Pemberton J, Yong-Fadok T, Szurszewski J, Farrugia G. Decreased interstitial cell of Cajal volume in patients with slow-transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:14–21. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wedel T, Spiegler J, Soellner S, Roblick UJ, Schiedeck TH, Bruch HP, Krammer HJ. Enteric nerves and interstitial cells of Cajal are altered in patients with slow-transit constipation and megacolon. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1459–1467. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JI, Park H, Kamm MA, Talbot IC. Decreased density of interstitial cells of Cajal and neuronal cells in patients with slow-transit constipation and acquired megacolon. J Gastroen Hepatol. 2005;20:1292–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]