Abstract

This study was designed to evaluate the antibiotic resistance phenotypes in wild-type Staphylococcus aureus (WT-SA), oxacillin-induced S. aureus (OI-SA), clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant S. aureus (CA-SA), wild-type Salmonella Typhimurium (WT-ST), ciprofloxacin-induced S. Typhimurium (CI-ST), clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium (CA-ST), wild-type Klebsiella pneumoniae (WT-KP), ciprofloxacin-induced K. pneumoniae (CI-KP), and clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant K. pneumoniae (CA-KP). The resistance of WT-SA, WT-ST, and WT-KP to ampicillin, ceftazidime, and cephalotin, penicillin was increased after induction by oxacillin OI-SA, ciprofloxacin CI-ST, and ciprofloxacin CI-KP, respectively. The highest β-lactamase activities were 12 and 36 μmol/min/ml, respectively, for CA-ST and CA-KP. The EtBr residues remained high in S. Typhimurium (>80%) and K. pneumoniae (>90%) when treated with CCCP. The distinct FT–IR spectra were observed in protein region (1700–1500 cm−1) and carbohydrate region (1200–900 cm−1). This study would provide useful information for better understating of specific resistance mechanisms in association with β-lactamase and efflux pump activities.

Keywords: Β-lactamase activity, Efflux pump activity, Resistance phenotype, Staphylococcus, Salmonella, Klebsiella

Introduction

Over the past few decades, antibiotics have long been used to treat disease-causing bacteria. However, their chemotherapeutic misuse and overuse have led to the emergence of resistant bacteria [1]. The antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections have become of great public health concerns due to the problems with diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. The mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in bacteria include enzymatic modification (β-lactamases), decreased permeability (selective blockade), increased membrane transport (efflux pumps), altered binding site (specific receptors), and metabolic bypass (alternate pathway) [2]. The horizontal gene transfer is responsible for the spread of plasmid-encoded β-lactamases genes such as extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL), AmpC, and TEM-1 [3, 4]. The production of the β-lactamase contribute to antibiotic resistance by directly hydrolyzing β-lactam antibiotics. Multidrug efflux pumps are an important resistance determinants by extruding antibiotics out of bacteria [5]. The efflux pumps have a broad substrate specificity.

The development of rapid detection methods has recently received great attention with increasing the emergence of multidrug resistant bacteria. The detection of multidrug resistance is a primary step to effectively control antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections that can cause clinical treatment failure and lead to additional antibiotic resistance [6, 7]. The antibiotic susceptibility profiles are commonly used to determine the resistance phenotype of bacteria as measured by minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). Molecular techniques are used for the confirmation of antibiotic resistant genes in bacteria. However, the resistance phenotypes do not always correlate with the resistance phenotypes. The discrepancies between phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic-resistant properties can cause false interpretation of antibiotic susceptibility results, ultimately leading to the inappropriate antibiotic therapy. Therefore, it is essential to assess the resistance phenotype in association with antibiotic resistance mechanisms such as β-lactamase and efflux pump activities. In this study, we aimed to compare the antibiotic resistance phenotypes in laboratory, antibiotic-induced, and clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture condition

Wild-type strains of Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 15564 (WT-SA), Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 19585 (WT-ST), and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 23357 (WT-KP) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The stepwise selection method [8] was used to induce the antibiotic-induced S. aureus ATCC 15564, S. Typhimurium ATCC 19585, and K. pneumoniae ATCC 23357, which were assigned to oxacillin-induced S. aureus (OI-SA), ciprofloxacin-induced S. Typhimurium (CI-ST), and ciprofloxacin-induced K. pneumoniae (CI-KP), respectively. The stability of induced antibiotic resistance in OI-SA, CI-ST, and CI-KP was confirmed by prolonged cultures (>10 passages) in antibiotic-free trypticase soy broth (TSB; Difco, Becton, Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD, USA). The clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant strains, S. aureus CCARM 3080 (CA-SA), S. Typhimurium CCARM 8009 (CA-ST), and K. pneumoniae CCARM 10237 (CA-KP), were obtained from Culture Collection of Antibiotic Resistant Microbes (CCARM, Seoul, Korea). All strains were cultured aerobically in TSB at 37 °C for 20 h and then harvested by centrifugation at 3000×g for 20 min at 4 °C. The harvested cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) and then used in the assays [9].

Antibiotic susceptibility assay

The antibiotic susceptibilities of WT-SA, WT-ST, WT-KP, OI-SA, CI-ST, CI-KP, CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP were determined according to microbroth dilution assay. Antibiotic stock solutions (2048 µg/ml each; ampicillin, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, cephalotin, imipenem, meropenem, oxacillin, penicillin, and piperacillin) were prepared by dissolving in sterile distilled water. Each antibiotic solution (100 µl) prepared in a series of twofold dilutions in 96-well microtiter plates and then inoculated with each test strain (105 cfu/ml in 100 µl) to obtain a final concentration of 512 µg/ml. The prepared plates were incubated for 18 h at 37 °C to determine minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration with no visible growth. MIC breakpoints were used to define susceptible (S), intermediate (I), and resistant (R) strains [10].

Lactamase inhibition assay

The susceptibilities of WT-SA, WT-ST, WT-KP, OI-SA, CI-ST, CI-KP, CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP to β-lactam antibiotics were evaluated in the absence and presence of β-lactamase inhibitor (tazobactam, 4 µg/ml) [11]. MICs were determined as above mentioned.

Nitrocefin hydrolysis assay

The β-lactamase activity of WT-SA, WT-ST, WT-KP, OI-SA, CI-ST, CI-KP, CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP was measured by using a β-lactamase activity colorimetric assay kit (BioVision Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA). All strains are incubated in TSB containing 1/4 MIC oxacillin at 37 °C for 20 h. The cell-free supernatant was prepared by centrifugation at 3000×g for 20 min at 4 °C and incubated with 50 μl of reaction mixture containing 48 μl of b-lactamase assay buffer and 2 μl of nitrocefin at 37 °C for 30 min. The ability of nitrocefin to hydrolyze β-lactamase was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc.). A standard curve was prepared at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, and 50 nmol of hydrolyzed nitrocefin standard. The β-lactamase activity was expressed as nmol/min/ml.

Efflux pump inhibition assay

The efflux pump activity of WT-SA, WT-ST, WT-KP, OI-SA, CI-ST, CI-KP, CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP was evaluated in the absence and presence of efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs), carbonyl cyanide-m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) and phenylalanine-arginine-β-naphthylamide (PAβN). All strains adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard were incubated in PBS containing ethidium bromide (2 μg/ml, EtBr) and CCCP (1/4 MIC) for 1 h at 25 °C. The EtBr-loaded cells were suspended with 0.4% glucose in PBS and then mixed with CCCP (1/4 MIC) or PAβN (1/4 MIC). The fluorescence was measured using a RF-5301PC spectrofluoro photometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at emission and excitation wavelengths of 580 nm and 500 nm, respectively.

FT–IR analysis

FT–IR spectrometer (Excalibur series; Bio-Rad, Cambridge, MA) equipped with a UMA-500 microscope was used to evaluate the biochemical properties of WT-SA, WT-ST, WT-KP, OI-SA, CI-ST, CI-KP, CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP. All cells were lyophilized prior to FT–IR analysis. FT–IR spectra were recorded in wave numbers ranging from 4000 cm−1 to 650 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software. All analyses were carried out in duplicate for three replicates. The general linear model (GLM) and Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) procedures were used to determine significant mean differences at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Changes in antibiotic susceptibilities in the presence of β-lactamase inhibitor

The MICs of β-lactam antibiotics against WT-SA, OI-SA, CA-SA, WT-ST, CI-ST, CA-ST, WT-KP, CI-KP, and CA-KP were determined in the absence and presence of β-lactamase inhibitor, tazobactam, as shown in Tables 1, 2, and 3. All strains were classified into antibiotic-sensitive (S), intermediate (I) and resistant (R) based on the MIC breakpoints [10]. After resistance induction by oxacillin or ciprofloxacin, the susceptibilities to most β-lactam antibiotics were decreased in OI-SA, CI-ST, and CI-KP (Tables 1–3). Compared to wild-type strains, CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP were highly resistant to ampicillin, penicillin, and piperacillin, showing MICs of more than 512 μg/ml. The results indicate that antibiotic selection pressure can induce multidrug resistant bacteria [12]. The susceptibilities of all strains tested in this study to β-lactam antibiotics were increased in the presence of tazobactam. The susceptibilities of WT-SA, OI-SA, and CA-SA to ampicillin were increased by more than eightfold (Table 1), those of WT-ST, CI-ST, and CA-SA to cefotaxime were increased by more than eightfold (Table 2), and those of WT-KP, CI-KP, and CA-KP to imipenem were increased by more than twofold (Table 3). Tazobactam could inhibit TEM, SHV and CTX-M type β-lactamases which hydrolyze the penicillins and cephalosporins [13, 14]. This indicates that β-lactamases produced by WT-SA, OI-SA, CA-SA, WT-ST, CI-ST, WT-KP, CI-KP and CA-KP might be TEM, SHV and CTX-M type β-lactamases.

Table 1.

Changes in antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus in the presence of tazobactam (TB)

| Antibiotic | Staphylococcus aureus a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-SA | OI-SA | CA-SA | ||||

| w/o TB | w TB | w/o TB | w TB | w/o TB | w TB | |

| Ampicillin | 8 (S)b | 0.25 | 64 (R) | 8 | 256 (R) | 32 |

| Cefotaxime | 2 (S) | 2 | 8 (I) | 8 | >512 (R) | >512 |

| Cefoxitin | 4 (S) | 2 | 4 (S) | 4 | >512 (R) | 256 |

| Ceftazidime | 8 (S) | 16 | 128 (R) | 128 | >512 (R) | >512 |

| Ceftriaxone | 4 (S) | 2 | 32 (R) | 32 | >512 (R) | >512 |

| Cephalotin | 0.5 (S) | 0.125 | 4 (R) | 2 | 256 (R) | 128 |

| Imipenem | <0.03 (S) | <0.03 | 0.125 (S) | <0.06 | 256 (R) | 128 |

| Meropenem | 0.25 (S) | 0.25 | 1 (I) | 1 | 128 (R) | 128 |

| Oxacillin | 0.25 (S) | 0.125 | 8 (R) | 8 | >512 (R) | 512 |

| Penicillin | 16 (R) | 0.06 | 64 (R) | 4 | 32 (R) | 32 |

| Piperacillin | 16 (S) | 1 | 16 (S) | 16 | 512 (R) | 128 |

aWT-SA, OI-SA, and CA-SA denote wild-type S. aureus, oxacillin-induced S. aureus, and clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant S. aureus, respectively

bS, I, and R represent susceptible, intermediate, and resistant strains, respectively

Table 2.

Changes in antibiotic susceptibility of Salmonella Typhimurium in the presence of tazobactam (TB)

| Antibiotic | Salmonella Typhimuriuma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-ST | CI-ST | CA-ST | ||||

| w/o TB | w TB | w/o TB | w TB | w/o TB | w TB | |

| Ampicillin | 8 (S)b | 2 | 16 (S) | 8 | >512 (R) | 32 |

| Cefotaxime | 4 (S) | 0.125 | 4 (S) | 0.5 | 4 (S) | 0.125 |

| Cefoxitin | 2 (S) | 8 | 8 (S) | 64 | 4 (S) | 16 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25 (S) | 0.25 | 0.5 (S) | 0.25 | 1 (S) | 0.25 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25 (S) | 0.25 | 0.25 (S) | 0.25 | 0.125 (S) | 0.125 |

| Cephalotin | 8 (S) | 8 | 64 (R) | 32 | 32 (R) | 16 |

| Imipenem | 2 (I) | 0.5 | 2 (I) | 0.25 | 1 (S) | 0.5 |

| Meropenem | 0.25 (S) | 0.25 | 0.03 (S) | <0.03 | 0.125 (S) | 0.125 |

| Penicillin | 4 (S) | 4 | 32 (R) | 32 | >512 (R) | 8 |

| Piperacillin | 4 (S) | 2 | 8 (S) | 8 | >512 (R) | 8 |

aWT-ST, CI-ST, and CA-ST denote wild-type S. Typhimurium, ciprofloxacin-induced S. Typhimurium, and clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant S. Typhimurium, respectively

bS, I, and R represent susceptible, intermediate, and resistant strains, respectively

Table 3.

Changes in antibiotic susceptibility of Klebsiella pneumonia in the presence of tazobactam (TB)

| Antibiotic | Klebsiella pneumonia a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-KP | CI-KP | CA-KP | ||||

| w/o TB | w TB | w/o TB | w TB | w/o TB | w TB | |

| Ampicillin | 256 (R)b | 8 | >512 (R) | 128 | >512 (R) | >512 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.125 (S) | 0.125 | 8 (I) | 0.5 | 128 (R) | 128 |

| Cefoxitin | 16 (I) | 32 | 64 (R) | 64 | 512 (R) | 512 |

| Ceftazidime | 1 (S) | <0.5 | 8 (S) | 0.5 | >512 (R) | >512 |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.25 (S) | 0.25 | 4 (S) | 0.25 | 128 (R) | 32 |

| Cephalotin | 32 (R) | 16 | 64 (R) | 64 | >512 (R) | >512 |

| Imipenem | 4 (R) | 2 | 16 (R) | 4 | 32 (R) | 2 |

| Meropenem | 0.125 (S) | 0.125 | 0.25 (S) | 0.25 | 0.5 (S) | 1 |

| Penicillin | 256 (R) | 32 | 512 (R) | 128 | >512 (R) | >512 |

| Piperacillin | 16 (S) | 4 | 16 (S) | 8 | >512 (R) | 512 |

aWT-KP, CI-KP, and CA-KP denote wild-type K. pneumoniae, ciprofloxacin-induced K. pneumoniae, and clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant K. pneumoniae, respectively

bS, I, and R represent susceptible, intermediate, and resistant strains, respectively

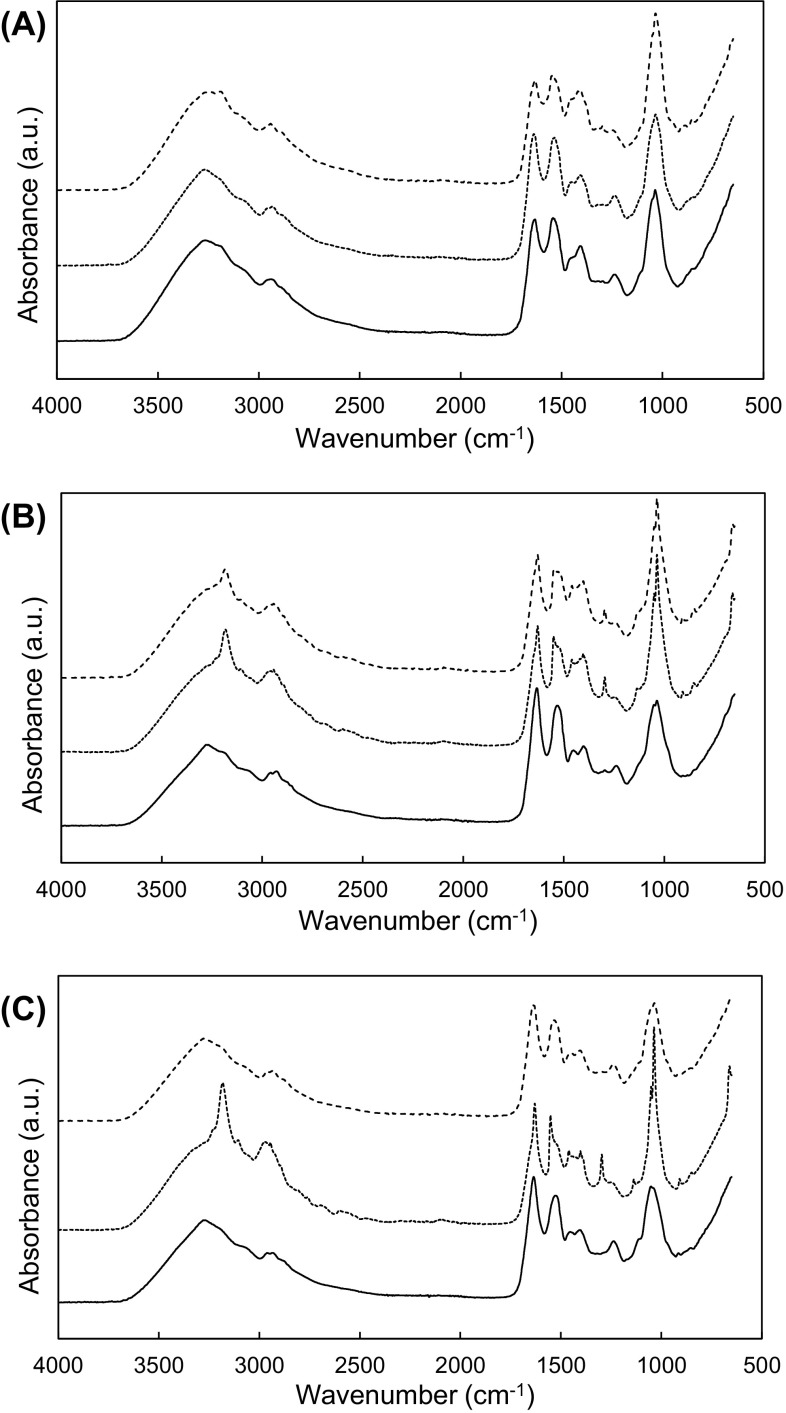

The extracellular β-lactamase activities were measured in all strains treated with oxacillin. No significant change in β-lactamase activities was observed in CA-SA, WT-ST, CI-ST, WT-KP, and CI-KP (Fig. 1). This suggests that CA-SA, WT-ST, CI-ST, WT-KP and CI-KP could have different resistance mechanisms such as penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) with low affinity for β-lactamases and changes in membrane permeability [15–17]. The highest β-lactamase activities were observed in WT-SA and OI-SA, showing 38 and 39 μmol/min/ml, respectively. The β-lactamase activities of the CA-ST and CA-KP were 12 and 36 μmol/min/ml, respectively. The production of the β-lactamases was increased in WT-SA, OI-SA, CA-ST and CA-KP when exposed to oxacillin. This implies that the pre-exposure of bacteria to β-lactams can stimulate the induction of β-lactamases.

Fig. 1.

Hydrolyzing activity of β-lactamases produced by wild-type (WT), ciprofloxacin-induced (CI), oxacillin-induced (OI), and clinically-acquired antibiotic resistant (CA) Staphylococcus aureus (SA), Salmonella Typhimurium (ST), and Klebsiella pneumonia (KP). Means with different letters (A–B) on the bars are significantly different at P < 0.05. (n.d.) and (***) not detected and significantly different at P < 0.001

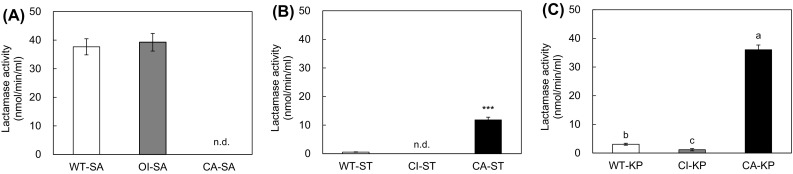

Changes in efflux pump activities in the presence of efflux pump inhibitors

The efflux pump activities of all strains used in this study were evaluated in the absence or presence of efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs; CCCP and PaβN) (Fig. 2). No significant change in EtBr residues was observed among WT-SA, CI-SA, and CA-SA treated with CCCP (Fig. 2A). The EtBr residues of WT-SA, CI-SA, and CA-SA in the absence and presence of EPIs were more than 60%, showing low efflux pump activity. This observation implies that S. aureus had relatively low efflux pump activity or EPIs were less effective against Gram-positive than Gram-negative bacteria. Unlike S. aureus strains, the noticeable efflux activities were observed for S. Typhimurium (Fig. 2B) and K. pneumoniae (Fig. 2C). The EtBr residues were decreased to less than 30% in S. Typhimurium and K. pneumoniae treated with no EPIs, while those remained 80% and 100%, respectively, in S. Typhimurium and K. pneumoniae when treated with CCCP. Although both CCCP and PAβN could significantly decrease the efflux pump activity, CCCP is more effectively inhibit the efflux pump systems than PAβN (non-specific inhibitor) in S. Typhimurium and K. pneumoniae. The efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance is attributed to the proton motive force and substrate competition [18]. CCCP and PAβN can disrupt proton electrochemical gradient and compete with antibiotics, respectively [19]. In Fig. 3C, the EtBr residues varied in strains, showing 80, 60, and 50%, respectively, in WT-KP, CI-KP, and CA-KP. This suggests that various efflux pump systems were developed in antibiotic-resistant K. pneumoniae [20].

Fig. 2.

Efflux pump activity of Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Klebsiella pneumonia in the presence of none (white square), CCCP (gray square), and PAβN (black square). Means with different letters within treatment (A–C) and strains (A–C) on the bars are significantly different at P < 0.05. WT-SA, WT-ST, WT-KP, OI-SA, CI-ST, CI-KP, CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP denote wild-type S. aureus, S. Typhimurium, K. pneumoniae, oxacillin-induced S. aureus, ciprofloxacin-induced S. Typhimurium, K. pneumoniae, clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant S. aureus, S. Typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae, respectively

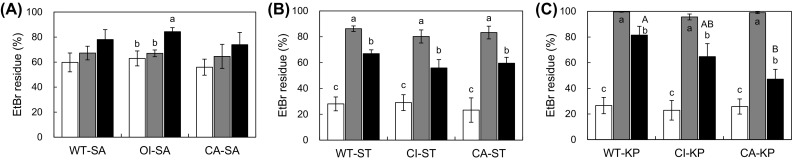

Fig. 3.

FT–IR spectra of wild-type (WT), oxacillin-induced (OI), ciprofloxacin-induced (CI), and clinically-acquired (CA) Staphylococcus aureus (SA), Salmonella Typhimurium (ST), and Klebsiella pneumonia (KP). a.u. arbitrary units. (solid curve) WT-SA, WT-ST, and WT-KP; (doted curve) OI-SA, CI-ST, and CI-KP; (dashed curve) CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP

Changes in chemical components of the bacterial cells

FT–IR was used to differentiate and characterize the chemical components of WT-SA, OI-SA, CA-SA, WT-ST, CI-ST, CA-ST, WT-KP, CI-KP and CA-KP (Fig. 3; Table 4). The spectral range was divided by wavenumber, including lipid region (3000–2800 cm−1), protein region (OMP; 1700–1500 cm−1), phospholipid-nucleic acid region (1500–1200 cm−1), carbohydrate region (LPS; 1200–900 cm−1), and fingerprint region (900–700 cm−1) (Fig. 3) [21]. The functional groups and corresponding references were assigned to the absorbance peaks (Table 4). The highest intensities were observed at 3178, 2970, 1625, 1553, 1401, 1299, and 1125 cm−1 corresponding to asymmetric stretching mode of NH2, C–H stretch of CH3 in fatty acids, amide I of α-helix structure of protein, amide II mode, symmetric COO– stretching, C–N stretching vibration, and C–H bending vibration, respectively, in all strains. Major cellular components were collected in protein region (1700–1500 cm−1) and carbohydrate region (1200–900 cm−1). No considerable changes in absorbance were observed among WT-SA, OI-SA, and CA-SA, while the distinct peak within the same strains was observed at 1036 cm−1 assigned to carbohydrate C–O stretching mode in CI-ST and CI-KP. The change in LPS can plays an important role in the induction of antibiotic resistance in bacteria [22]. The observations suggest that the acquisition of antibiotic resistance in bacteria could lead to the changes in physical properties and chemical components [23]. Although minor changes were not observed in this analysis, FT–IR can be a promising tool to discriminate antibiotic-resistant bacteria based on the major cellular components changes. The spectral features reflect the changes in components specific to antibiotic-resistant bacteria [24].

Table 4.

Frequencies and assignments of absorbance peaks in FT–IR spectra of wild-type (WT), ciprofloxacin-induced (CIP), oxacillin-induced (OIAR), and clinical acquired (CAAR) Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Klebsiella pneumonia a

| Wave no. | S. aureus | S. Typhimurium | K. pneumonia | Band assignment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cm−1) | WT-SA | OI-SA | CA-SA | WT-ST | CI-ST | CA-ST | WT-KP | CI-KP | CA-KP | |

| 720 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.25 | C–H rocking of CH2 |

| 960 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 | C–H rocking of CH2 and CH3 |

| 1036 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.32 | Carbohydrate C–O stretching mode |

| 1080 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.24 | Phosphodiester groups of DNA and RNA |

| 1154 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.13 | Carbohydrate C–O stretching mode |

| 1211 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.13 | Stretching of PO bond in phosphate |

| 1222 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.14 | PO bond in phosphate |

| 1303 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.13 | Vibration C–N of amides II |

| 1370 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.15 | Bending of C–H |

| 1384 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.18 | Symmetric stretching of COO– and CH2/CH3 |

| 1420 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.19 | Symmetric stretching of COO– |

| 1450 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.19 | C-H bending of CH2; CH2 scissoring |

| 1455 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.19 | Asymmetric bending of CH3/CH2 of proteins |

| 1600 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.20 | Asymmetric COO– stretches |

| 1654 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.27 | Amide I of α-helical structure of proteins |

| 2850 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.10 | Symmetric stretching of C–H in fatty acids |

| 2855 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.10 | C–H of CH2 in fatty acid chains |

| 2870 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.11 | Symmetric stretching of CH3 of methyl |

| 2918 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.13 | CH2 stretching of methylene in fatty acids |

| 2929 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.14 | Asymmetric stretching of C–H and CH2 |

| 2960 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.14 | C–H of –CH3 in fatty acids |

aWT-SA, WT-ST, WT-KP, OI-SA, CI-ST, CI-KP, CA-SA, CA-ST, and CA-KP denote wild-type S. aureus, S. Typhimurium, K. pneumoniae, oxacillin-induced S. aureus, ciprofloxacin-induced S. Typhimurium, K. pneumoniae, clinically-acquired antibiotic-resistant S. aureus, S. Typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae, respectively

In conclusion, this study highlights the difference in resistance phenotype of WT-SA, OI-SA, CA-SA, WT-ST, CI-ST, CA-ST, WT-KP, CI-KP, and CA-KP. The phenotypic properties (β-lactamase, efflux pump activity, and cell components) varied with antibiotic susceptibilities of strains tested in this study. The characteristic changes in β-lactam antibiotic susceptibilities were observed after exposure to lactamase inhibitor. However, the susceptibilities of strains to β-lactams were still constant following exposure to tazobactam, implying that the strains tested in this study produced various β-lactamases. In addition, the acquisition of β-lactam resistance is not only attributed to the production of β-lactamases, but also associated with other mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. The characteristic changes in the chemical components of bacteria can be used as biomarkers to detect antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The results would provide useful information regarding resistance phenotypes which is essential for the design of strategies to treat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1D1A3B01008304). This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No. HI15C-1798-000016).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Roch M, Clair P, Renzoni A, Reverdy M-E, Dauwalder O, Bes M, Martra A, Freydière A-M, Laurent F, Reix P, Dumitrescu O, Vandenesch F. Exposure of Staphylococcus aureus to subinhibitory concentrations of β-lactam antibiotics induces heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agent. Chemother. 2014;58:5306–5314. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02574-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khameneh B, Diab R, Ghazvini K, Fazly Bazzaz BS. Breakthroughs in bacterial resistance mechanisms and the potential ways to combat them. Microb. Pathogen. 2016;95:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pérez-Pérez FJ, Hanson ND. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC & ®-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:2153–2162. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2153-2162.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Thungrat K, Boothe DM. Occurrence of OXA-48 carbapenemase and other β-lactamase genes in ESBL-producing multidrug resistant Escherichia coli from dogs and cats in the United States, 2009–2013. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1057. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcalde-Rico M, Hernando-Amado S, Blanco P, Martínez JL. Multidrug efflux pumps at the crossroad between antibiotic resistance and bacterial virulence. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1483. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tenover FC, Reller LB, Weinstein MP. Rapid detection and identification of bacterial pathogens using novel molecular technologies: Infection control and beyond. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;44:418–423. doi: 10.1086/510684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fluit AC, Visser MR, Schmitz F-J. Molecular detection of antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14:836–871. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.836-871.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birošová L, Mikulášová M. Development of triclosan and antibiotic resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Med. Microbiol. 2009;58:436–441. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.003657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jo A, Ahn J. Phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of multiple antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus exposed to subinhibitory levels of oxacillin and levofloxacin. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:170. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0791-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CLSI. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M07–A10 (2015).

- 11.Chen C, Lv J, Chen W, Xiang Y, Zhang J. Colorimetric β-lactamase inhibitor assay with double catalyzed signal amplification. New J. Chem. 2016;40:1982–1987. doi: 10.1039/C5NJ02356D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu JH, Pan YS, Yuan L, Wu H, Hu GZ, Chen YX. Genetic variations in the active efflux pump genes acrA/B and tolC in different drug-induced strains of Escherichia coli CVCC 1547. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013;12:2829–2836. doi: 10.4238/2013.August.8.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blazquez J, Baquero MR, Canton R, Alos I, Baquero F. Characterization of a new TEM-type β-lactamase resistant to clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agent. Chemother. 1993;37:2059–2063. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.10.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tzouvelekis LS, Tzelepi E, Tassios PT, Legakis NJ. CTX-M-type ®-lactamases: an emerging group of extended-spectrum enzymes. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agent. 2000;14:137–142. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00165-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartman BJ, Tomasz A. Low-affinity penicillin-binding protein associated with β-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1984;158:513–516. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.513-516.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pages J-M, Lavigne J-P, Leflon-Guibout V, Marcon E, Bert F, Noussair L, Nicolas-Chanoine M-H. Efflux pump, the masked side of ß-lactam resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stapleton PD, Taylor PW. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: mechanisms and modulation. Sci. Prog. 2002;85:57–72. doi: 10.3184/003685002783238870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagès J-M, Masi M, Barbe J. Inhibitors of efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria. Trend. Mol. Med. 2005;11:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto Y, Hayama K, Sakakihara S, Nishino K, Noji H, Iino R, Yamaguchi A. Evaluation of multidrug efflux pump inhibitors by a new method using microfluidic channels. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kehrenberg C, de Jong A, Friederichs S, Cloeckaert A, Schwarz S. Molecular mechanisms of decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones in avian Salmonella serovars and their mutants selected during the determination of mutant prevention concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;59:886–892. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preisner O, Guiomar R, Machado J, Menezes JC, Lopes JA. Application of fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics for differentiation of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis phage types. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:3538–3544. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01589-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunn JS. Bacterial modification of LPS and resistance to antimicrobial peptides. J. Endotoxin. Res. 2001;7:57–62. doi: 10.1177/09680519010070011001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salman A, Sharaha U, Rodriguez-Diaz E, Shufan E, Riesenberg K, Bigio IJ, Huleihel M. Detection of antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli bacteria using infrared microscopy and advanced multivariate analysis. Analyst. 2017;142:2136–2144. doi: 10.1039/C7AN00192D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amiali NM, Mulvey MR, Berger-Bächi B, Sedman J, Simor AE, Ismail AA. Evaluation of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for the rapid identification of glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61:95–102. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]